Abstract

Background

The current study aimed to develop a laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor system for biofuel production.

Scope & Approach

During the investigation, Jute was discovered to be the best, cheap, hairy, open-pored supporting material for biofilm formation. Microalgae & yeast consortium was used in this study for biofilm formation.

Conclusion

The study identified microalgae and yeast consortium as a promising choice and ideal partners for biofilm formation with the highest biomass yield (47.63 ± 0.93 g/m2), biomass productivity (4.39 ± 0.29 to 7.77 ± 0.05 g/m2/day) and lipid content (36%) over 28 days cultivation period, resulting in a more sustainable and environmentally benign fuel that could become a reality in the near future.

Keywords: Biofilm, Photobioreactor, Biomass productivity, Consortium, Sustainable

1. Introduction

Burgeoning population, rapid urbanization, crisis of fossil fuel depletion as well as ongoing water contamination issues, all have seen modern society's reliance since the industrial revolution and have been solemnly challenged in recent decades by the resultant energy crises and environmental deterioration [1,2]. In this context, despite the growing sustainability concerns, the scientific community has been challenged in recent decades to realign the path of utilizing renewable and ecologically benign biomass sources capable of addressing simultaneously both the rising challenges of energy security as well as wastewater disposal in a simple and effective manner [3,4].

At this juncture, microalgae and yeast are believed to be the most practical and cost-effective biological alternatives that are simultaneously capable of accumulating significant lipid concentrations for biofuel production in response to metabolic stress and has been considered a suitable alternative and renewable source of energy [4,5]. Despite its potential to be a significant driver in the development of a sustainable bio-based economy for the production of biofuel, large-scale commercialization has yet to be proven due to low biomass productivity, technical and economic feasibility like inefficient harvesting, energy-intensive installation and operating costs of photobioreactors, high water and nutrient demand, insufficient supply of low-cost concentrated carbon dioxide, additional cost dewatering suspended microalgae [2,6].

Many solutions have been implemented to address these issues including two-stage culture metabolic/genetic engineering, and co-culturing or symbiosis [5]. Among these techniques, co-culturing has been intensively explored in recent years using minimal resources. Co-culturing is generally a practice of growing two or more species in the same medium so that they can benefit from each other's metabolic pathways. However, the quality, number, and type of organisms involved in co-cultures are carefully specified [7]. The most potentially significant co-culture interaction involves oleaginous microalgae and yeast, in which the microalgae supply oxygen for the yeast to consume carbon substrates while the yeast releases carbon dioxide to boost algal photosynthesis [8]. As a result of this interaction between microalgal species and symbiotic organisms, overall biomass and desired products increased. Moreover, their nutrients and water requirement can be met with wastewater collected from municipal, agricultural run-off, and industries that can be a low-cost and long-term investment, serving dual purpose for bioremediation of wastewater in addition to biofuel generation [9].

Conventional culture cultivation methods have primarily focused either on open ponds or closed photobioreactors [10]. Although open systems are simple to construct, they are vulnerable to light constraints and stressors that inhibit algal development over a particular cell concentration. Furthermore, because of the low algal cell density, biomass harvesting and concentration are exceedingly expensive. Moreover, the invasion of local biota endangers large-scale microalgal growth. On the other hand, some studies investigated closed photobioreactors, which are more productive. However, due to their high construction and operational costs, they are prohibitively costly for large-scale application [11,12].

Until now, extensive research has been conducted aimed at improving cultivation systems by either improving increasing biomass yields or process design. Despite ongoing research, microalgal biofilm-based adherent culture systems or attached cultivation system offer an alternative approach to biomass production that could address bio-energy challenges due to ease of harvesting, lower construction investment costs, and low water and energy consumption [13]. To examine the adherent algal culture systems, various algal biofilm systems are currently being developed. However, it is believed that the efficacy of biomass generation in diverse algal biofilm systems is strongly influenced not only by culture conditions, algal strains, and process scale, but also by the properties of materials that enable adherent growth prior to evolving into biofilm [14]. Microalgal biofilm-based adherent culture systems provide several advantages including: 1) high biomass productivity; 2) low harvesting and operational costs; 3) resistance to growth stresses; 4) greater reactor design flexibility compared to conventional suspension systems; 5) accelerated reaction rates; 6) no cell washout and 7) better operational stability and 8) dewatering costs are reduced since biomass is more concentrated (90–150 g/L) than the typical suspended algal concentrations found in photobioreactors and raceway ponds (0.5–4 g/L) [13,15].

Owing to the aforementioned benefits, the current study aimed to develop a laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor system for adherent culture growth for biofilm production. Here, previously isolated namely freshwater microalgae strain C. sorokiniana UUIND6 and yeast strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae UUIND1 were used as models for microalgae biofilm and microalgae-yeast consortia biofilm formation in this work, using wastewater as a cheap source of key nutrients from both technological and ecological standpoint. The efficacy of biofilm was studied utilizing a variety of textile-based supporting materials (Jute, Cotton, Jeans, and Polyester). The best screened supporting material was chosen for future exploration to assess the performance of the developed photobioreactor using microalgae and yeast consortium as well as monoculture microalgae for biofilm formation.

2. Methods

2.1. Microorganism strains and culture conditions

Previously isolated freshwater microalgae strain C. sorokiniana UUIND6 (GenBank accession number: KY780616) and yeast strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae UUIND1 (Genbank accession number: KY385556) were chosen as models for this study for their ability to form biofilms and grow under specific conditions. The yeast was maintained in a sterile solution of YEPD medium (yeast extract peptone dextrose — glucose, 10; peptone, 5; yeast extract, 3 g/L) media. YEPD medium was supplemented with 5–10 μL ampicillin (100 mg/mL) to avoid bacterial growth. Yeast growth was monitored by measuring O.D.660nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Model 1906) [16]. The freshwater microalgae was maintained in Bold's Basal Medium (BBM) [17]. Stock cultures were grown at 25 °C, 300 μmolm−2s−1 white light, 18 h light and 6 h dark cycle. Cold white Crompton Greaves LED lamp provides the light. Microalgal growth was monitored by measuring O.D.686nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Model 1906) [16]. Cultures were gently mixed twice a day for 5 days before being moved to a laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor for adherent culture system investigation. All the chemicals and reagents used for the preparation of BBM and biochemical analysis were of HPLC grade and were procured from Hi-Media Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India.

2.2. Cultivation of biofilm

Wastewater was collected near Graphic Era University in Uttarakhand, India, for the growth of two biofilms i.e., 1) microalgae biofilm and 2) microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm. The sample point was chosen to get wastewater that was highly polluted. Once collected, the wastewater was filtered through a Whatman filter paper No. 1 to eliminate total suspended particles. The essential properties of the sampled wastewater such as chemical oxygen demand (COD), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), total nitrogen (TN), and total phosphorus (TP) were assessed using standard procedures [18,19].

Removal efficiency of wastewater pollutants was determined using the following Equation (1):

| (1) |

where and are the concentration of each water quality indicator before and after the treatment and ηi denotes nutrients removal efficiency (%).

2.3. Assessment of various supporting materials for the establishment of adherent culture biofilm

To investigate the effects of cell-surface features on the development and screening of algal biofilm growth, four different biofilm supportive materials were tested: polyester, jeans, cotton, and jute. The materials were chosen with the qualities of being economical, durable, and easy to procure. In brief, each supporting material was cut into squares with dimensions of 0.07 m × 0.07 m (surface area = 0.0049 m2) using a scissor. Each type of supporting matrix was sterilized at 120 °C for 20 min before being placed in a 0.09 m glass Petri dish containing 30 mL of sterile BBM. The algal cell inoculum was poured into each Petri dish containing the supporting matrix to achieve a final concentration of O.D.680nm = 0.9. The petri dishes were placed on a rotating shaker at 70 rpm and kept in the same conditions as previously described for the maintenance cultures for 7 days. To compensate for water loss, distilled water was also added every two days with minor modification [20].

2.4. Design and construction of laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor system

As illustrated in Fig (1), a stationary laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor system was constructed to execute the notion of adherent culture growth. The photobioreactor system consists of an external case and four separate inner culture channels. The external enclosure (length = 0.6 m, breadth = 0.34 m, depth = 0.01 m) with a working volume capacity of 2.04 L of wastewater was employed to maintain the biofilm culture at 25 °C ± 2 °C.

Fig. 1.

Experimental set-up of stationary laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor system.

The best supporting cell attachment material (with a surface area of 0.0448 m2) was used and stretched to create a thin layer covering only the surface of the four culture channels. Each channel of dimensions (length = 0.56 m, width = 0.08 m, depth = 0.01 m) was partially immersed in wastewater and the inoculum for microalgae and yeast biofilm (3:1 with initial concentration 5 × 105 cells/mL) and for microalgae biofilm initial concentration 5 × 105 cells/mL was injected onto the supporting material and exposed to an illumination of white LED light at 25 °C ± 2 °C that eventually grew into biofilms, constituted the inner vessel of a laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor [21]. The light intensity applied to the channel was precisely controlled to 300 μmolm−2s−1 operated at a photoperiod of 16 h: 8 h (light: dark) and CO2 gas was pumped into each culture channel.

2.5. Quantification of biofilm biomass and productivity

The biomass samples of the attached culture system were washed-off and harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 5 min, and then again washed thrice with deionized water to remove salts adhering to the cell surface. Biofilm biomass was determined by drying samples in an oven at 60 °C for 72 h and measured gravimetrically. The biomass yield (g/m2 of attaching materials) and biomass productivity (g/m2/day) of adherent culture biofilms were calculated using Equations (2), (3) provided by Dalirian et al. [10]:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where DW is the dry weight of biomass and is the surface area of the supporting material.

2.6. Analysis of total lipid

The lyophilized biomass pellets were further employed for lipid analysis using gravimetric methods [22].

2.7. Zeta potential and cell size measurements

A Nano-ZS/ZEN 3600 was used to measure the zeta potential and cell size. Zeta potential was calculated at room temperature of 20 °C ± 2 °C. For each species, triplicate cultures were measured, and each dataset included 10–20 values for each sample [23].

2.8. Characterization of the biofilm

Both biofilms were examined to render the sample surface conductive for Scanning Electron Microscropy (SEM) imaging with Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis for elemental mapping.

2.9. Lipid profile and FAME composition analysis using FTIR, 1H NMR, and GC-MS

Lipids extracted from dried biomass of both the biofilms were catalytically trans-esterified and were mixed with 6% methanolic H2SO4 and incubated for 60 min at 90 °C. After completion of the trans-esterification reaction, hexane was added as solvent. To purify the synthesized bio-diesel, the hexane layer containing the trans-esterified lipid was removed, and the resultant trans-esterified lipids were washed with hot water. The chemical composition of the produced biodiesel was determined using FTIR at 400-4000 cm−1 (PerkinElmer, MA, USA) and 1H NMR spectroscopy [[24], [25], [26]].

The fatty acid profile was measured using Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS, Agilent) using DB-5MS columns (30 mm, 0.25 mm, 1 μm), helium as the carrier gas (1 mL/min), and an adjusted software [27].

2.10. Statistical data analysis

All studies were run in triplicate (n = 3), and data variability was reported as mean ± standard deviation. OPSTAT was used for statistical analysis. To assess statistically significant differences, one-way ANOVA was utilized. A p-value of <0.05 was regarded as significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Screening suitable supporting material for microalgae biofilm growth

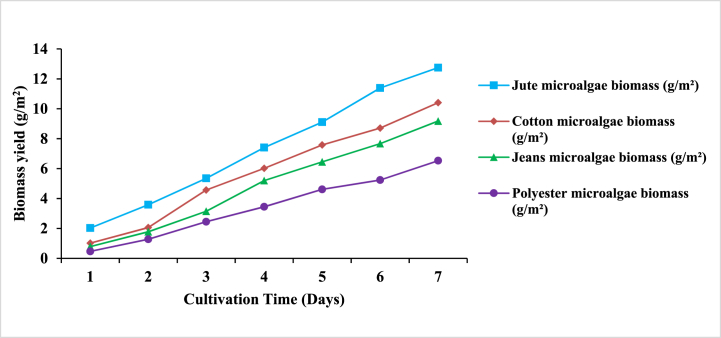

In order to better correlate the results with the usual suspended microalgal ecosystem observed in photobioreactors and raceway ponds, alterations in the microalga's growth were investigated using a range of supportive materials for biofilm production. The efficacy of biomass formation in various algal biofilm systems is thought to be substantially impacted not only by culture conditions, algal strains, and process scale, but also by the qualities of materials that allow adherent growth prior to changing into biofilm [14]. As a result, in the current study four types of supporting matrices, namely Polyester, Jeans, Cotton, and Jute, were investigated by culturing microalgae in BBM for screening suitable material for implementation in the laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor system depicted in Fig. 2. The materials were chosen with the qualities of being economical, durable, and easy to procure. When the influence of the various supporting materials was compared, Jute (12.04 g/m2) showed outstanding microalgae growth as shown in Supplementary Fig (1), followed by Cotton (10.41 g/m2), Jeans (9.18 g/m2), and Polyester (6.53 g/m2) after 7 days of cultivation period. Fig. 3 shows the attachment performance of microalgae grown on the surface of different materials.

Fig. 2.

Microalgae biofilm growth on various supporting materials.

Fig. 3.

Microalgae attachment performance on various supporting material surfaces.

Previous research on Chlorella found that it was more attached to polystyrene foam compared to cardboard, polyethylene fabric, or loofah sponge [28]. For mixed microalgal culture, cotton rope exhibited more attachment than nylon, polypropylene, cotton, acrylic, and jute. Similarly, Scenedesmus obliquus exhibited maximum biomass productivity among four distinct microalgal species employing glass plate and filter paper as attachment material [1].

Previous studies also discovered that microalgal attachment is usually accompanied by a bacterial biofilm, which secretes extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and hence aids microalgal cell adhesion [29]. However, in this work, autoclaved media was used for microalgal growth, which meant bacterial contamination was exceedingly minimal. It was also observed that the concentration of microalgae growth in the Petri dish with Jute as a supporting matrix was found to be approximately twice than that of the concentration of microalgae identified in the least growing matrix sample i.e., Polyester. In fact, an increase in surface roughness greatly facilitates cell deposition on Jute surface by providing more contact surface area or mechanical interlocking at the interface. Surface micro-patterns act as a refuge for attached cells, preventing the biofilm from excessive sloughing [30].

Thus, the present findings clearly emphasized Jute as the best, most affordable, hairy, open-pored supporting material that not only promotes microalgal biofilm growth, but also demonstrated that study-dependent discrepancies in supporting material selection are most likely due to variations in microalgal species. As a result, Jute was chosen for further investigation in the current study.

3.2. Biofilm productivity and lipid content in laboratory-scale photobioreactor system

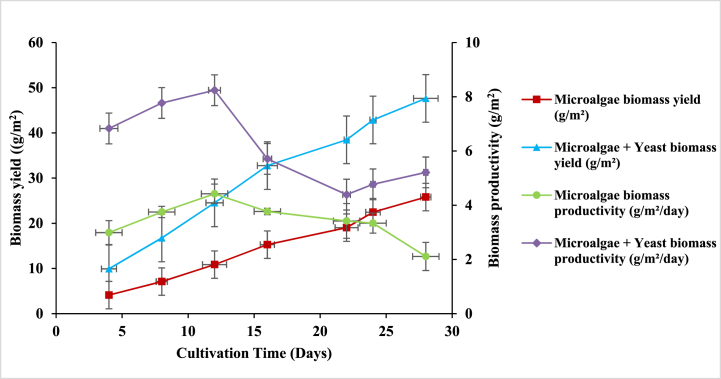

In the functioning of the laboratory-scale photobioreactor system, Jute was employed as a supporting material to evaluate biomass yield and productivity. The microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm was compared to monoculture microalgae biofilm. Cells of both kinds of biofilm gradually attached and grew on the surface of the jute surface. According to the results of the study, the exponential growth phase was visible throughout the 28-day culture period. Consortium cells in the biofilm grew faster and strong species-specific linkages were seen compared to monoculture microalgae cells as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Growth of monoculture microalgae and Yeast + Microalgae consortium in the laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor during 28 days of cultivation period. Data values are the average of three replicates, and the error bars are standard deviations.

Furthermore, after 28 days of cultivation time, the biomass yield of microalgae and yeast consortium (47.63 ± 0.93 g/m2) was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of microalgae (25.80 ± 0.39 g/m2). Similarly, as compared to monoculture microalgae, there was substantial increase in biomass productivity for microalgae and yeast consortium at a range of 4.39 ± 0.29 to 7.77 ± 0.05 g/m2/day. The lipid content in yeast and microalgae consortium biofilms (36%) was also found to be greater than in monoculture microalgal biofilms (32%). Comparison of performance of various strains in various textile supporting materials is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of performance of various strains in various textile supporting materials.

| Strain | Supporting material | Biomass yield (g/m2) | Biomass productivity (g/m2/day) | Lipid content (% DW) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed culture | Cotton rope | – | 2.12 | – | [31] |

| Polyproyplene | 0 | ||||

| Nylon | 0 | ||||

| Polyester | 0.29 | ||||

| Low thread cotton | 1.42 | ||||

| High thread cotton | 1.54 | ||||

| Jute | 1.62 | ||||

| Acrylic | 0.85 | ||||

| Chlorella vulgaris | Cotton duct | 16.20 ± 2.12 | 1.08 ± 0.1 | – | [32] |

| Cotton rag | 10.50 ± 2.98 | 0.70 ± 0.19 | – | ||

| Cotton denim | 1.35 ± 1.18 | 0.09 ± 0.08 | – | ||

| Cotton corduroy | 1.20 ± 0.92 | 0.08 ± 0.06 | – | ||

| Microalgae consortium (Chlorella sp., Pediastrum sp., Nitzschia sp., etc.) | Nylon mesh | – | 9.10 | – | [33] |

| Polyculture microalgae | Braid cotton | – | 4.11 | – | [34] |

| C. vulgaris, O. tenuis, S. obliquus, bacteria | Coral velvet | – | 10.54–14.68 | – | [35] |

| C. sorokiniana UUIND6 | Jute | 25.80 ± 0.39 | 2.11 ± 0.52 to 4.43 ± 0.36 | 32 | Current study |

| C. sorokiniana UUIND6 + Saccharomyces cerevisiae UUIND1 | 47.63 ± 0.93 | 4.39 ± 0.29 to 7.77 ± 0.05 | 36 |

*Data values are represented as mean ± standard deviation of three replicates, (−) indicates data not available.

3.3. Zeta potential and size measurement

Zeta potential measurements are necessary to identify the suspension's isoelectric point [36]. It is a significant indication of the degree of repulsion between charged particles or describes the stability of the suspension. At pH 7, the zeta potential of the yeast and microalgae consortium was greater, with a higher negative charge value (−16.67 mV) than that of the microalgae suspension alone (−11.25 mV). With an increase in the absolute value of zeta potential, or in other words, a high negative zeta potential, the electric repulsion between particles becomes greater, and the cells become more dispersed and very stable against aggregation. When the zeta potential is near zero, particles can approach each other to the point where they are attracted by van der Waals forces and hence have the greatest tendency to agglomerate. Prior research also found high zeta potential (38.2 meV) of microalgae C. pyrenoidosa at pH 9 due to the presence of carboxylic (-COOH), amine (-NH2), and phosphate (-PO4) groups on their cell surface, indicating a stable suspension at alkaline pH. As the pH rises above 5, the –COOH groups dissipate, leaving the microalgae with a net negative charge. The charge repels two microalgal cells, allowing them to remain suspended in a liquid without sedimentation [37]. The zeta potential of Chlorella sp. revealed that the isoelectric point occurred in the pH range of 4.16–9.55, with magnitudes of zeta potentials ranging from −10 mV to −35 mV [38]. As a result, the current investigation discovered that the zeta potential of yeast and microalgae consortium solution was more stable than microalgae alone. In the current study, microalgae cell size was reported to be larger (2.74 μm) than yeast and microalgae consortium cells (2.37 μm).

3.4. Biofilm characterization

3.4.1. SEM analysis

A clear distinction between the developed microalgae biofilm and microalgae and yeast biofilm. Due to surface smoothness of the microalgae biofilm, the microalgae cells may readily be seen growing in size in Supplementary Fig. 2 (A-D). This expansion in microalgae cells after wastewater treatment demonstrates the involvement of the microalgae in nutrient absorption from wastewater. On the other hand, while co-culturing microalgae with yeast for biofilm formation, the microalgae cells in the biofilm were difficult to recognize as seen in Supplementary Fig. 2 (E-H) due to the rough surfaces. The rough surface morphology might be the result of pollutant particles in wastewater interacting with the EPS of the microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm, resulting in adsorption or bio-transformation.

3.4.2. EDX analysis

EDX is a powerful approach used for locating metal binding sites due to large surface areas of algal cells than other microbial biomass. In the current investigation, EDX of both the biofilms revealed the presence of large binding sites for carbon and oxygen on the cell surface, showing that microalgae and yeast biofilm had higher carbon content (41.27%) and lower oxygen content (58.73%) than microalgae biofilm, which had lower carbon content (33.81%) and higher oxygen content (66.19%), confirming their ability to effectively take up these nutrients from the growth medium depicted in Supplementary Fig. 3 (a and b).

3.5. Chemical composition and fatty acids profile of biofilms derived lipids

3.5.1. FTIR analysis

The mode of vibration, active functional groups and intensity of spectra of the derived lipids from microalgae biofilm and microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm are depicted in Table 2 and Supplementary Fig 4. Some medium stretching sorption peaks indicating carbohydrate and lipid functional groups (=C–H and C–H), were also determined in the microalgae and yeast consortium at 1372 cm−1, 2994 cm−1 and 2852 cm−1 but absent in microalgae. However, the presence of medium bands ranging from 1600 to 1475 cm−1 was identified on both monoculture microalgae as well as microalgae and yeast consortium, implying nitro-compound nitro and aromatic compounds (N–O and C–C). Moderately stretched bands were also detected at 1029, 1228 suggesting the presence of aliphatic amines, aromatic amines, respectively. Between 3200 and 3500 cm−1, a sharp and broad-spectrum band, indicating the presence of specific alcohols or phenols (inter-molecular O–H stretch) in both microalgae and yeast consortium and microalgae monoculture.

Table 2.

FTIR bands of isolated lipids from Microalgal biofilm and Yeast + Microalgae consortium biofilm.

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Bond | Functional groups | Microalgae Biofilm | Yeast + Microalgae Biofilm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3200–3500 | O–H stretch, intermolecular H-bonded | alcohols, phenols | 3275 | 3275 |

| 2850–3100 | C–H stretch = C–H |

alkenes, alkanes, aromatics | – | 2994 2852 |

| 1475–1600 | C–C stretch N–O stretch |

aromatics, nitro compound |

1532 1638 |

1532 1638 |

| 1350–1450 | C–H bend C–H rock |

Alkanes | – | 1372 |

| 1250–1335 | C–N stretch | aromatic amines | 1228 | 1228 |

| 1020–1250 | C–N stretch | aliphatic amines | 1029 | 1029 |

3.5.2. NMR analysis

NMR spectra of the lipids derived from microalgae biofilm and microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm were investigated using 1H NMR spectroscopy. The functional groups are provided in Table 3 and are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5(a and b). When comparing the individual intensities of each biocrudes, the presence of six different peaks was observed in the biocrude of microalgal biofilm, including glyceryl and olefinic methine; diallylmethylene; methylenes α to the carbonyl; allyl methylene; methylene and methyls ranging from 5.2 to 5.5 ppm; 2.7–2.9 ppm; 2.2–2.5 ppm, 1.9–2.1 ppm; 1.0–1.4 ppm and 0.7–1.0 ppm, respectively, except methylenes β to the carbonyl. On the other hand, biocrude from microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm showed the presence of only three comparable peaks, namely methylenes to carbonyl; methylenes and methyls ranging from 1.5 to 1.8 ppm, 1.0–1.4 ppm and 0.7–1.0 ppm, respectively.

Table 3.

1H NMR chemical shifts of isolated lipids from Microalgal biofilm and Yeast + Microalgae consortium biofilm.

| Chemical shift (ppm) | Chemical Assignment | Microalgae Biofilm | Microalgae + Yeast Biofilm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7–1.0 | Methyl | + | + |

| 1.0–1.4 | Other Methylenes | + | + |

| 1.5–1.8 | Methylenes β to the carbonyl | – | + |

| 1.9–2.1 | Allylic methylenes | + | – |

| 2.2–2.5 | Methylenes α to the carbonyl | + | – |

| 2.7–2.9 | Diallylic methylenes | + | – |

| 5.2–5.5 | Glyceryl and olefinic methine | + | – |

+ sign indicates: presence, - sign indicates: absence.

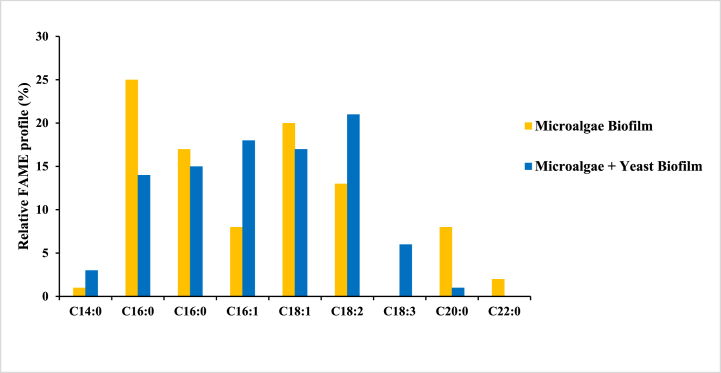

3.5.3. GC-MS analysis

NIST library of GC-MS was used to analyze the changes in the fatty acid profiles of the developed biofilms. Moreover, the components were identified on the basis of their retention area % >1 as shown in Fig. 5. Table 4 contains the nomenclature and information for all fatty acids derived from both the biofilms. Overall, 9 fatty acids were discovered, with saturated fatty acids (SFAs) in the C14 to C22 range being more abundant than unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) in microalgae biofilm. The major SFAs identified in both biofilms include behenic acid, palmitic acid, myristic acid, arachidic acid, and stearic acid, all of which play an important role in pollutant removal from wastewater. This is because these SFAs are amphipathic in nature and are thought to be bio-surfactants that facilitate particle absorption by microalgal biofilms as well as have the ability to degrade organic compounds and, hence play an important role in wastewater treatment [[39], [40], [41]]. The absence of these bio-surfactants in biofilm cells after wastewater treatment supports the fact that wastewater triggers bio-surfactants secretion by microalgal biofilms, that enhances nutrient availability in the water [42,43]. High saturation in biodiesel's fatty acid composition also promotes oxidative stability and cetane number, extending shelf life by avoiding autoxidation [44]. In contrast to microalgae biofilm, the microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm is predominantly composed of UFAs, with high levels of mono-unsaturated (palmitoleic acid and oleic acid) and poly-unsaturated fatty acids (linoleic acid and α-linolenic acid). A higher PUFA content in biocrude lowers the cetane number, which increases NOx emissions, and reduces the viscosity of the biodiesel, thus supporting smoother engine performance and improving diesel engine efficiency. It also has lower melting points, which improves cold flow properties [45]. Unsaturation in the fatty acid profile, on the other hand, predicts increased fuel utility at low temperatures [44]. Therefore, based on the current findings, co-culturing microalgae and yeast increased carbon fixation capability because yeast devoured dissolved oxygen generated by microalgae during photosynthesis. As a result of this symbiotic association, the concentration of biomass and net photosynthetic activity of co-culturing microalgae and yeast are both boosted up. Furthermore, the consortium induces changes in fatty acid ratios, improving lipid content in comparison to microalgae grown separately, shifting from saturated to unsaturated forms, as similar behaviour has been observed in S. obliquus and Candida tropicalis [46]. Supplementary Table (1) illustrated all of the physical attributes defining the quality of the obtained biodiesel.

Fig. 5.

FAME profile of Microalgal biofilm and Yeast + Microalgae consortium biofilm.

Table 4.

GC-MS analysis of isolated lipids from Microalgal biofilm and Yeast + Microalgae consortium biofilm.

| Fatty acid and their common name | Abbreviation | Microalgae Biofilm (%) |

Yeast + Microalgae Biofilm (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetra-decanoic acid (Myristic acid) | C14:0 | 1 | 3 |

| Hexa-decanoic acid (Palmitic acid) | C16:0 | 25 | 14 |

| Octa-decanoic acid (Stearic acid) | C18:0 | 17 | 15 |

| Hexa-decenoic acid (Palmitoleic acid) | C16:1 | 8 | 18 |

| Octa-decenoic acid (Oleic acid) | C18:1 | 20 | 17 |

| Octa-decadienoic acid (Linoleic acid) | C18:2 | 13 | 21 |

| Octa-decatrienoic acid (α-Linolenic acid) | C18:3 | 0 | 6 |

| Eicosanoic acid (Arachidic acid) | C20:0 | 8 | 1 |

| Docosanoic acid (Behenic acid) | C22:0 | 2 | 0 |

3.6. Biofilms efficiency for wastewater treatment

Wastewater contamination is one of the major challenges faced by many developed nations and has deteriorated to alarming levels. Municipal wastewater contamination with a large number of organic and inorganic pollutants strains the food chain and consequently the foundation of human life. Because of the widely varying sizes, kinds of pollutants, and geographical circumstances, wastewater treatment is considered as a worldwide issue because of the limited degrading capability of conventional technologies [47]. Many wastewater treatment plants are under pressure to improve wastewater effluent quality in order to fulfil rigorous discharge standards and relieve the eutrophication phenomena. Only a few studies have concentrated on nutrient removal from wastewater and lipid accumulation till date. However, the efficacy of microorganism growth in terms of nutrient removal and lipid generation varies between species [48].

In the current study, the potential of both the biofilms i.e., microalgae biofilm and yeast and microalgae consortium biofilm, is directly related to their ability to remediate wastewater by lowering various chemical and physical parameters. Table 5 depicts the initial features and removal effectiveness of biofilms used to treat wastewater. After 14 days of incubation period in the current study, both biofilms were able to decrease color, odour, and pH of the wastewater. It was found that pH was shifted from acidic (pH: 4.9) to alkaline range (pH: 7.8–8.1). The alkaline pH shift might be due to the fact that the microalgae converted the carbon dioxide in the medium to bicarbonate, releasing hydroxide ions thus, making the medium alkaline [49]. On the contrary, yeast cell proliferation results in acidic media, which finally inhibits microalgae development. As a consequence of metabolite interaction, the media's intrinsic oxygen/carbon dioxide, pH, and dissolved oxygen levels can be balanced, resulting in an overall increase in the growth rate of both species. It was also observed that yeast and microalgae consortium biofilm was more efficient for the removal of COD (58.88 ± 0.01%), TP (66.37 ± 0.34%), while microalgae biofilm exhibited maximum efficiency in removal of TN (91.9 ± 0.15%) and BOD (57.77 ± 0.04%).

Table 5.

Basic characteristics and removal efficiency of municipality wastewater using Microalgal biofilm and Yeast + Microalgae consortium biofilm.

| Properties | Raw wastewater | Microalgae Biofilm (After 14 days treatment) | Yeast + Microalgae Biofilm (After 14 days treatment) | Microalgae Biofilm Removal (%) |

Yeast + Microalgae Biofilm Removal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Dark Brown | Light brown | Light brown | – | – |

| pH | 4.9 | 7.8 | 8.1 | – | – |

| Smell | Yes | No | No | – | – |

| COD (mg/L) | 58 ± 0.02 | 28.3 ± 0.01 | 24.1 ± 0.04 | 51.2 ± 0.01 | 58.44 ± 0.01 |

| TN (mg/L) | 38.9 ± 0.15 | 3.15 ± 0.23 | 5.31 ± 0.01 | 91.9 ± 0.15 | 86.34 ± 0.22 |

| TP (mg/L) | 18.11 ± 0.03 | 8.35 ± 0.06 | 6.09 ± 0.37 | 53.89 ± 0.06 | 66.37 ± 0.34 |

| BOD (mg/L) | 18 ± 0.12 | 7.6 ± 0.02 | 9.4 ± 0.02 | 57.77 ± 0.04 | 47.77 ± 0.04 |

COD: chemical oxygen demand; BOD: biochemical oxygen demand; TN: total nitrogen; TP: total phosphorous.

Humans release significant amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus in the form of agricultural fertilizer, wastewater and other kinds of plant and animal waste, which accelerates the eutrophication of water bodies, making it critical to treat the wastewater [50]. Monoculture microalgae may easily remove nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon dioxide from wastewater streams [51]. They take up nitrogen in the form of ammonium due to its ease of assimilation capacity and lower energy consumption, while phosphorus is essential for microalgal metabolic processes and is usually found in form of inorganic phosphate or organic compounds. They can decrease the levels of BOD and COD in wastewater by two ways: 1) by consuming both organic and inorganic components [52] and 2) by releasing oxygen via photosynthesis, resulting in microalgae growth and decreasing water oxygen needs, thereby lowering BOD. They are, however, ineffective in removing organic molecules with COD levels more than 5 g/L [51,53]. Previous study also showed that using microalgae to remediate nitrogen and phosphorus in dark and odorous water treated with Spirulina achieved 100% removal efficiency [54]. Similarly, removal ability of microalgae to total phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations in municipal wastewater were found to be >80% and 87%, respectively as investigated by Mennaa et al. [55]. Chlorella minutissima and Scenedesmus abundans can remove 70% and 56% of BOD and COD, respectively to remediate dairy wastewater. However, very less removal efficiency was observed in BOD (38%) and COD (24%) for Nostoc muscorum and Spirulina sp., respectively, by Chandra et al. [56].

Co-culturing of yeast and microalgae, on the other hand, has a certain influence. They can successfully recycle nitrogen, phosphorous, high COD (15–50 g/L) from wastewaters while also providing green energy compared to microalgae monocultures [51]. Co-culture experiments have validated the preceding assertion, including the removal efficiency of shrimp culture effluent by co-culturing yeast (Rhodosporidium sp.) and microalgae (both in fixed and non-fixed modes). This finding demonstrated that co-culturing yeast and microalgae had the highest removal rate of nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients, with removal rates of NH4+, NO2−, NO3−and PO43− of 85.47%, 100%, 96.09%, and 93.38%, respectively [57].

COD and BOD removal efficiencies of both the biofilms reported in this study are comparatively low as compared to other studies. The poor removal efficiency accounts for greater production of reactive oxygen species by biofilms during water treatment. This continual increase in reactive oxygen species demonstrates the influence of wastewater pollutants' oxidative stress on the microalgae biofilm [58], lowering wastewater polluting potential. Aside from the effect of pollutants, cell size and shape, cell density, and cell number all have an impact on the increase and release of reactive oxygen species.

4. Conclusion

Currently, microalgal biofilm biotechnology has been fully evaluated by previous studies for the practical feasibility of developing various adherent culture systems using microalgal biofilms for biomass production and wastewater remediation. Based on fundamental research linked with the development and operation of microalgal biofilm, there has been little study on microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm to overcome the bottleneck of feedstock production for the biofuel sector as well as problems associated for wastewater treatment. Therefore, the goal of the present work was to construct and evaluate the performance of laboratory-scale biofilm photobioreactor system to implement the notion of adherent culture growth for formation of monoculture microalgae biofilm as well as yeast and microalgae consortium biofilm. To better correlate results with the usual suspended microalgal ecosystem observed in photobioreactors and raceway ponds, changes in microalgal growth were studied using various textile fabrics as supporting materials for biofilm formation. When the textile fabrics for the biofilm formation were compared, it was clear that Jute was found to be the best, most affordable, hairy, open-pored supporting material and was chosen for further investigation to compare the performance of both microalgae and yeast consortium biofilm as well as monoculture microalgae biofilm. Furthermore, the current study identified C. sorokiniana UUIND6 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae UUIND1 as a promising choice for biofilm formation with the highest biomass yield (47.63 ± 0.93 g/m2), biomass productivity (4.39 ± 0.29 to 7.77 ± 0.05 g/m2/day), and lipid content (36%), when compared to monoculture microalgae biofilm with biomass yield (25.80 ± 0.39 g/m2), biomass productivity (2.11 ± 0.52 to 4.43 ± 0.36 g/m2/day) and lipid content (32%). Microalgae and yeast consortium biofilms were also shown to have higher pollutant reduction effectiveness from wastewater when compared to microalgal biofilms.

Overall, despite limited information on yeast and microalgae consortium biofilms, which can improve biomass productivity and lipid content, the current study suggested that these two can be ideal partners for biofilm formation compared to monoculture microalgae biofilm, leading to a more sustainable route of wastewater treatment as well as environmentally friendly fuel that may become a reality in the near future.

Author contribution statement

Bhawna Bisht: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Monu Verma: Performed the experiments.

Rohit Sharma: Performed the experiments.

Pankaj Chauhan: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Kumud Pant: Performed the experiments.

Hyunook Kim: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Mikhail S. Vlaskin: Performed the experiments.

Vinod Kumar: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare the no financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests.

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, New Delhi for the financial support under the Indo-Russian Project No. DST/INT/RUS/RSF/P-60/2021. This paper has been supported by the RUDN University Strategic Academic Leadership Program.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19353.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Liu T.Z., Wang J.F., Hu Q., Cheng P.F., Ji B., Liu J.L., Chen Y., Zhang W., Chen X.L., Chen L., Gao L.L., Ji C.L., Wang H. Attached cultivation technology of microalgae for efficient biomass feedstock production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013;127:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tripathi R., Gupta A., Thakur I.S. An integrated approach for phycoremediation of wastewater and sustainable biodiesel production by green microalgae. Scenedesmus sp. ISTGA1. Renew. Energy. 2019;135:617–625. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisht B., Gururani P., Pandey S., Jaiswal K.K., Kumar S., Vlaskin M.S., Verma M., Kim H., Kumar V. Multi-stage hydrothermal liquefaction modeling of sludge and microalgae biomass to increase bio-oil yield. Fuel. 2022;328 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma N., Jaiswal K.K., Kumar V., Vlaskin M.S., Nanda M., Rautela I., Tomar M.S., Ahmad W. nEffect of catalyst and temperature on the quality and productivity of HTL bio-oil from microalgae: a review. Renew. Energy. 2021;174:810–822. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora N., Patel A., Mehtani J., Pruthi P.A., Pruthi V., Poluri K.M. Co-culturing of oleaginous microalgae and yeast: paradigm shift towards enhanced lipid productivity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26:16952–16973. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genin S.N., Aitchison J.S., Allen D.G. Design of algal film photobioreactors: material surface energy effects on algal film productivity, colonization and lipid content. Bioresour. Technol. 2014;155:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goers L., Freemont P., Polizzi K.M. Co-culture systems and technologies: taking synthetic biology to the next level. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L., Chen J., Lim P.E., Wei D. Dual-species cultivation of microalgae and yeast for enhanced biomass and microbial lipid production. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018;30:2997–3007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantzorou A., Ververidis F. Microalgal biofilms: a further step over current microalgal cultivation techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;651:3187–3201. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalirian N., Najafabadi H.A., Movahedirad S. Surface attached cultivation and filtration of microalgal biofilm in a ceramic substrate photobioreactaor. Algal Res. 2021;55 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roostaei J., Zhang Y., Gopalakrishnan K., Ochocki A.J. Mixotrophic microalgae biofilm: a novel algae cultivation strategy for improved productivity and cost-efficiency of biofuel feedstock production. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31016-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou X., Xu K., Chang W., Qu Y., Li Y. A novel microalgal biofilm reactor using walnut shell as substratum for microalgae biofilm cultivation and lipid accumulation. Renew. Energy. 2021;175:676–685. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozkan A., Kinney K., Katz L., Berberoglu H. Reduction of water and energy requirement of algae cultivation using an algae biofilm photobioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;114:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Q., Liu C., Li Y., Yu Z., Chen Z., Ye T., Wang X., Hu Z., Liu S., Xiao B., Jin S. Cultivation of algal biofilm using different lignocellulosic materials as carriers. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2017;10:115. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0799-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chisti M.Y. Biodiesel from microalgae. Biotechnnol. Adv. 2007;25:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathur M., Kumar A., Ariyadasa T.U., Malik A. Yeast assisted algal flocculation for enhancing nutraceutical potential of Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Bioresour. Technol. 2021;340 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarnieri M.T., Nag A., Yang S., Pienkos P.T. Proteomic analysis of Chlorella vulgaris: potential targets for enhanced lipid accumulation. J. Proteomics. 2013;93:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebina J., Tsutsui T., Shirai T. Simultaneous determination of total nitrogen and total phosphorus in water using peroxodisulfate oxidation. Water Res. 1983;17:1721–1726. [Google Scholar]

- 19.APHA . In: Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. twenty-second ed. Rice E.W., Baird R.B., Eaton A.D., Clesceri L.S., editors. American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA) and Water Environment Federation (WEF); Washington, D.C., USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carbone D.A., Gargano I., Pinto G., De Natale A., Pollio A. Evaluating microalgae attachment to surfaces: a first approach towards a laboratory integrated assessment. Eng. Trans. 2017;57 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaiswal K.K., Kumar V., Vlaskin M.S., Nanda M. Impact of pyrene (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) pollutant on metabolites and lipid induction in microalgae Chlorella sorokiniana (UUIND6) to produce renewable biodiesel. Chemosphere. 2021;285 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bligh E.G., Dyer W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miranda A.F., Ramkumar N., Andriotis C., Höltkemeier T., Yasmin A., Rochfort S., Wlodkowic D., Morrison P., Roddick F., Spangenberg G., Lal B. Applications of microalgal biofilms for wastewater treatment and bioenergy production. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2017;10:1–23. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0798-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arora N., Gulati K., Patel A., Pruthi P.A., Poluri K.M., Pruthi V. A hybrid approach integrating arsenic detoxification with biodiesel production using oleaginous microalgae. Algal Res. 2017;24:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar V., Gururani P., Parveen A., Verma M., Kim H., Vlaskin M., Grigorenko A.V., Rindin K.G. Dairy Industry wastewater and stormwater energy valorization: effect of wastewater nutrients on microalgae-yeast biomass. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022;1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisht B., Kumar V., Gururani P., Tomar M.S., Nanda M., Vlaskin M.S., Kumar S., Kurbatova A. The potential of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in metabolomics and lipidomics of microalgae-a review. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2021.108987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar V., Nanda M., Joshi H.C., Singh A., Sharma S., Verma M. Production of biodiesel and bioethanol using algal biomass harvested from fresh water river. Renew. Energy. 2018;116:606–612. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson M., Wen Z. Development of an attached microalgal growth system for biofuel production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;85:525–534. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnurr P., Espie G., Allen G. Algae biofilm growth and the potential to stimulate lipid accumulation through nutrient starvation. Bioresour. Technol. 2013;136:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong C.Y., Derek C.J. Membrane surface roughness promotes rapid initial cell adhesion and long term microalgal biofilm stability. Environ. Res. 2022;206 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christenson L.B., Sims R.C. Rotating algal biofilm reactor and spool harvester for wastewater treatment with biofuels by-products. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012;109:1674–1684. doi: 10.1002/bit.24451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross M., Henry W., Michael C., Wen Z. Development of a rotating algal biofilm growth system for attached microalgae growth with in situ biomass harvest. Bioresour. Technol. 2013;150:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S.H., Oh H.M., Jo B.H., Lee S.A., Shin S.Y., Kim H.S., Lee S.H., Ahn C.Y. Higher biomass productivity of microalgae in an attached growth system, using wastewater. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;24:1566–1573. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1406.06057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hodges A., Fica Z., Wanlass J., VanDarlin J., Sims R. Nutrient and suspended solids removal from petrochemical wastewater via microalgal biofilm cultivation. Chemosphere. 2017;174:46–48. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Q., Li X., Ye T., Xiong M., Zhu L., Liu C., Jin S., Hu Z. Operation of a vertical algal biofilm enhanced raceway pond for nutrient removal and microalgae-based byproducts production under different wastewater loadings. Bioresour. Technol. 2018;253:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdul Hamid S.H., Lananan F., Din W.N.S., Lam S.S., Khatoon H., Endut A., Jusoh A. Harvesting microalgae, Chlorella sp. by bio-flocculation of Moringa oleifera seed derivatives from aquaculture wastewater phytoremediation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014;95 270-27. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharya A., Mathur M., Kumar P., Prajapati S.K., Malik A. A rapid method for fungal assisted algal flocculation: critical parameters & mechanism insights. Algal Res. 2017;21:42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henderson R., Parsons S.A., Jefferson B. The impact of algal properties and pre-oxidation on solid–liquid separation of algae. Water Res. 2008;42:827–845. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ron E.Z., Rosenberg E. Natural roles of biosurfactants. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;3:229–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter V., Syldatk C., Hausmann R. Screening concepts for the isolation of biosurfactant producing microorganisms. Biosurfactants. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;672:1–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5979-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ndlovu T., Khan S., Khan W. Distribution and diversity of biosurfactant-producing bacteria in a wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016;23:9993–10004. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hashimoto K., Matsuda M., Inoue D., Ike M. Bacterial community dynamics in a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant employing conventional activated sludge process. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2014;118:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez Y., Soto S.M. The Usefulness of microalgae compounds for preventing biofilm infections. Antibiotics. 2019;9:9. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9010009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel A., Sartaj K., Arora N., Pruthi V., Pruthi P.A. Biodegradation of phenol via meta cleavage pathway triggers de novo TAG biosynthesis pathway in oleaginous yeast. J. Hazard Mater. 2017;340:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knothe G. “Designer” biodiesel: optimizing fatty ester composition to improve fuel properties. Energy Fuel. 2008;22:158–1364. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang R., Tian Y., Xue S., Zhang D., Zhang Q., Wu X., Kong D., Cong W. Enhanced microalgal biomass and lipid production via coculture of Scenedesmus obliquus and Candida tropicalis in an autotrophic system. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016;91:1387–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wollmann F., Dietze S., Ackermann J.U., Bley T., Walther T., Steingroewer J., Krujatz F. Microalgae wastewater treatment: biological and technological approaches. Eng. Life Sci. 2019;19:860–871. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201900071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu X., Chen G., Tao Y., Wang J. Application of effluent from WWTP in cultivation of four microalgae for nutrients removal and lipid production under the supply of CO2. Renew. Energy. 2020;149:708–715. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue F., Miao J., Zhang X., Tan T. A new strategy for lipid production by mix cultivation of Spirulina platensis and Rhodotorula glutinis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010;160 doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8376-z. 498-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J., Feng Y., Zhang Y., Liang N., Wu H., Liu F. Allometric releases of nitrogen and phosphorus from sediments mediated by bacteria determines water eutrophication in coastal river basins of Bohai Bay. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022;235 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ling J., Nip S., Cheok W.L., de Toledo R.A., Shim H. Lipid production by a mixed culture of oleaginous yeast and microalga from distillery and domestic mixed wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2014;173:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mujtaba G., Rizwan M., Kim G., Lee K. Removal of nutrients and COD through co-culturing activated sludge and immobilized Chlorella vulgaris. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;343:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lam K.Y., Yu Z.H., Flick R., Noble A.J., Passeport E. Triclosan uptake and transformation by the green algae Euglena gracilis strain Z. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;833 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li L.H., Li X.Y., Hong Y., Jiang M.R., Lu S.L. Use of microalgae for the treatment of black and odorous water: purification effects and optimization of treatment conditions. Algal Res. 2020;47 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mennaa F.Z., Arbib Z., Perales J.A. Urban wastewater treatment by seven species of microalgae and an algal bloom: biomass production, N and P removal kinetics and harvestability. Water Res. 2015;83:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chandra R., Pradhan S., Patel A., Ghosh U.K. An approach for dairy wastewater remediation using mixture of microalgae and biodiesel production for sustainable transportation. J. Environ. Manage. 2021;297 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song Y., Wang L., Qiang X., Gu W., Ma Z., Wang G. The promising way to treat wastewater by microalgae: approaches, mechanisms, applications and challenges. J. Water Process Eng. 2022;49 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie X., He Z., Chen N., Tang Z., Wang Q., Cai Y. The roles of environmental factors in regulation of oxidative stress in plant. BioMed Res. Int. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/9732325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.