Abstract

Tricyclic bridgehead carbon centers (TBCCs) are a synthetically challenging substructure found in many complex natural products. Here we review the syntheses of ten representative families of TBCC-containing isolates, with the goal of outlining the strategies and tactics used to install these centers, including a discussion of the evolution of the successful synthetic design. We provide a summary of common strategies to inform future synthetic endeavors.

1. Introduction

1.1. Significance of tricyclic bridgehead carbon centers (TBCCs)

The syntheses of isolates containing quaternary carbon centers are challenging and have been the subject of numerous reviews.1–10 Tricyclic bridgehead carbon centers (TBCCs hereafter) are quaternary carbon centers located at a bridgehead position and embedded within three fused rings. This additional skeletal complexity creates considerable challenges for synthesis. Beyond the realm of natural product chemistry, TBCCs have emerged in drug discovery campaigns as their three-dimensionality11 is aligned with a renewed focus on sp3-rich molecules in industry.12

Here we systematically review syntheses of natural product targets bearing TBCCs, with an emphasis on the evolution of the successful synthetic approach and the final pathway that provided access to these structures. We close with a summary of general strategies to construct TBCCs, which may be applicable to a broader array of natural products and drug-like molecules. We envision that this review will benefit the synthetic community by aggregating and organizing the literature around the successful strategies that have been developed to access TBCCs. This review is meant to present representative examples and is not intended to be comprehensive. The reader is directed to earlier reviews of quaternary carbon centers for further discussion and examples from the literature.1–10

1.2. Trends in design strategies for syntheses of TBCCs: syntheses of enmein diterpenoids as an example

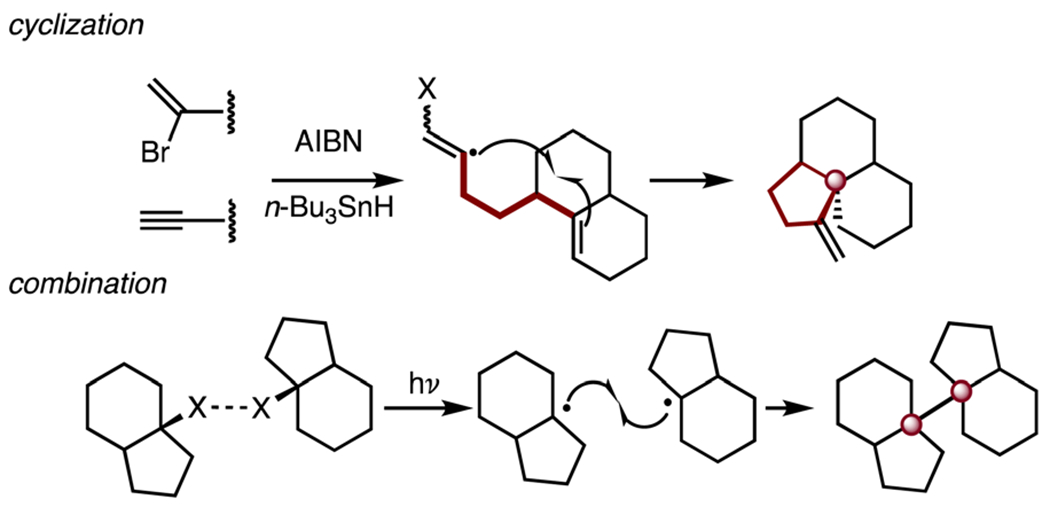

Early approaches to TBCCs are characterized by iterative acyclic bond-forming events, followed by ring-closing reactions. Subsequently, there was a major shift to cycloaddition reactions, which allow stereocontrolled formation of one or more TBCCs with concomitant generation of one or more rings. Advances in synthetic methods over the past ten years have provided highly efficient, stereoselective methods, such as asymmetric catalysis, photochemical transformations, and skeletal rearrangement enabled by newly invented promoters or catalysts, that can be used to access TBCCs. The total syntheses of enmein (1) by the Fujita group in 197413 and the Dong group in 201814 serve as illustrative examples that bookend the ends of this synthetic spectrum.

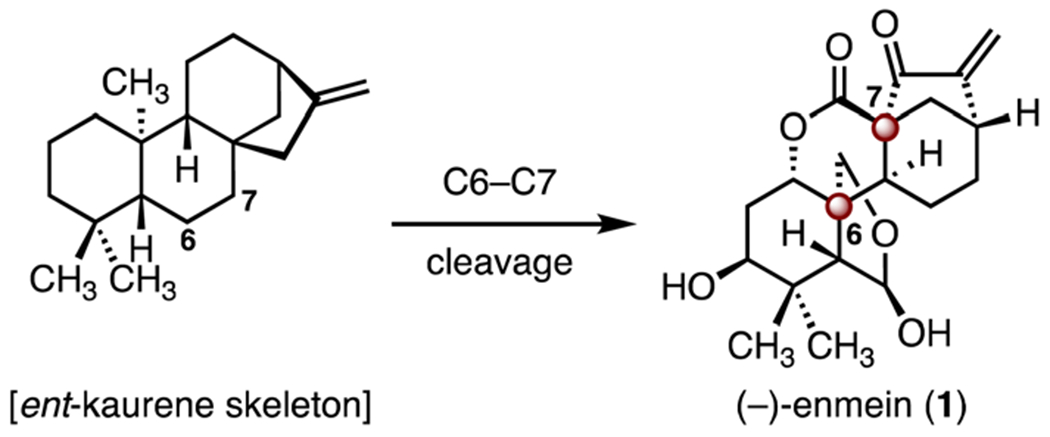

(−)-Enmein (1) is an ent-kaurene diterpenoid with a highly oxidized pentacyclic system (Scheme 1). (−)-Enmein (1) was first isolated from I. japonica by Natsume and co-workers in 1958.15,16 (−)-Enmein (1) derives biosynthetically from C6–C7 bond cleavage of the ent-kaurene skeleton (Scheme 1).17 Its structure was elucidated by chemical degradation,16 X-ray analysis of its heavy atom derivative,15 and chemical conversion to the known natural product, (−)-kaurene.18 (−)-Enmein (1) contains two TBCCs, C6 and C7.

Scheme 1.

Structure of (−)-enmein (1) and its biosynthetic origin.

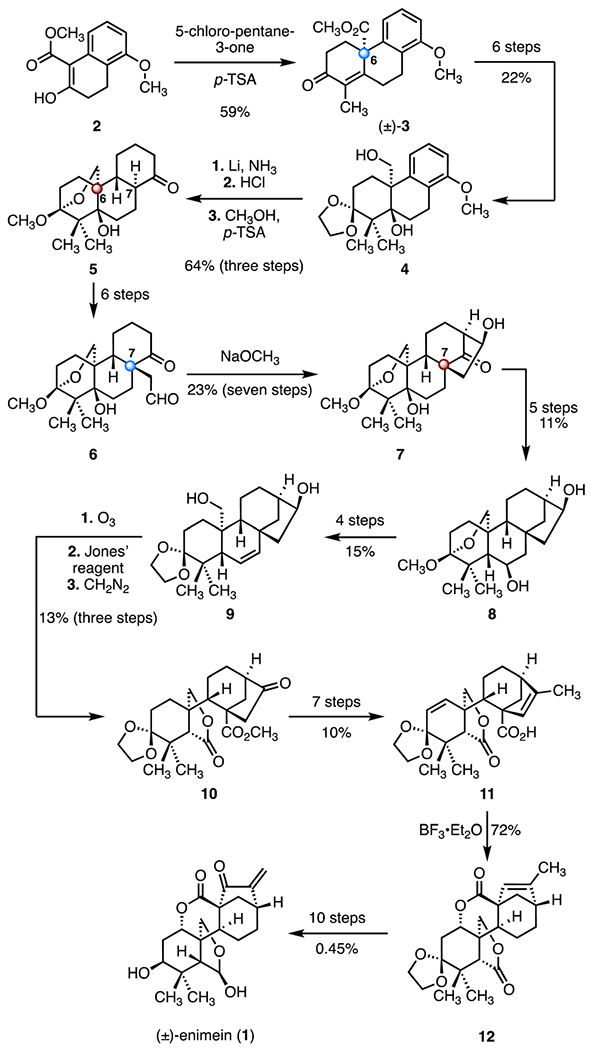

The Fujita group employed a relay strategy for the synthesis of (±)-enmein (1, Scheme 2).13,19 A Robinson annulation employing 5-chloro-pentane-3-one and the β-ketoester 2, promoted by p-toluenesulfonic acid, provided the tricycle (±)-3, which bears the C6 quaternary stereogenic center of the target (marked with a blue sphere; 59%).20 A six-step sequence then generated the ketal 4 (22% overall). Birch reduction (lithium, ammonia),222 followed by acid-catalyzed hydrolysis and hemiacetal formation (hydrochloric acid; p-toluenesulfonic acid, methanol) formed the cyclohexanone 5, with the C6 TBCC established (marked with a red sphere; 64%, three steps). A six-step sequence involving alkylation at the more-hindered α-position of the ketone 5 (C7) provided the aldehyde 6, which bears the C7 quaternary stereogenic center. An intramolecular aldol reaction (sodium methoxide) generated the cyclic hydroxy ketone 7, which bears the C7 TBCC (23%, seven steps). The hydroxy ketone 7 was elaborated to the alkene 9 through the relay intermediate 8 (nine steps, 1.6% overall). Oxidative cleavage of the alkene 9 (ozone), followed by oxidative lactonization (Jones’ reagent) and methylation (diazomethane), provided the lactone 10 (13%, three steps). A seven-step sequence was developed to transform the lactone 10 to the carboxylic acid 11 (10% overall). Lactonization (boron trifluoride diethyl etherate complex) formed the second lactone in 12, as a single diastereomer (72%). The total synthesis of (±)-enmein (1) was completed by a ten-step sequence (0.45% overall). In sum, the route provided access to the target in forty-seven steps and <0.0001% overall yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of (±)-enmein (1) by Fujita and co-workers.13,19 p-TSA = p-toluenesulfonic acid.

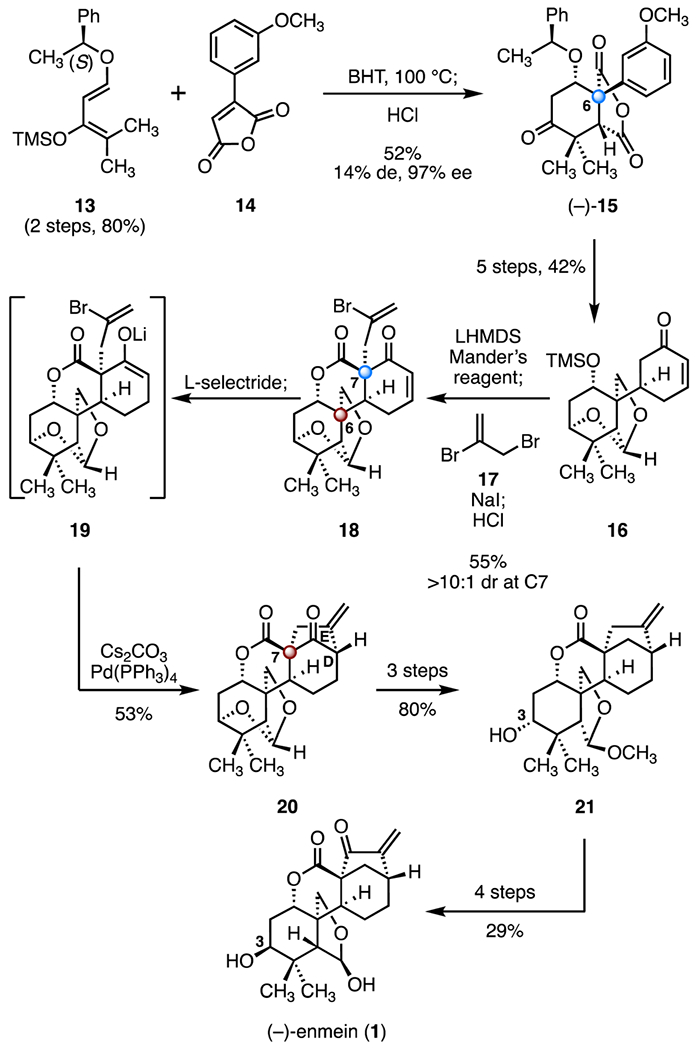

Dong and co-workers developed a convergent approach to (−)-enmein (1) that featured a cycloaddition and a reductive alkenylation as key steps (Scheme 3).14 The synthesis began with a Diels–Alder cycloaddition between the chiral Danishefsky diene derivative 13 (two steps from (S)-1-phenylethanol, 80%) and 3-(3-methoxyphenyl)furan-2,5-dione21 (14; butylated hydroxytoluene, 100 °C; then, hydrochloric acid, 52%, 14% de, 97% ee), which afforded the tricyclic cyclohexanone (−)-15 bearing the C6 quaternary stereogenic center. The cyclohexanone (−)-15 was converted to the enone 16 by a five-step sequence (42% overall). A one-flask acylation–alkylation–lactonization cascade (lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, Mander’s reagent; then, 17, sodium iodide; then, hydrochloric acid, 55%) generated the tricyclic lactone 18, which contains the C6 TBCC (>10 : 1 dr at C7). The alkylation conditions were extensively optimized to suppress competitive O-alkylation (not shown). Conjugate reduction of the enone 18 (L-selectride) produced the lithium enolate 19. An intramolecular enolate vinylation was achieved by treatment with tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) palladium(0) and cesium carbonate22 to furnish the ketone 20, which contains the D/E ring system of the target and the C7 TBCC (53%). A three-step sequence then formed the alcohol 21 (80% overall). Inversion of the C3 alcohol in 21, followed by allylic oxidation and methyl ether cleavage (29%, four steps), provided (−)-enmein (1). The target was obtained in seventeen steps with 1.2% overall yield.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of (−)-enmein (1) by Dong and co-workers.14 BHT = butylated hydroxytoluene, LHMDS = lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide.

These two syntheses of enmein (1) illustrate the dramatic increase in efficiency of synthetic approaches to targets containing TBCCs over the past fifty years. Replacement of one-bond forming cyclization events by two-bond forming cycloadditions greatly expedited construction of the polycyclic system. A fragment coupling strategy (13 + 14 → 15) increased convergence and avoided late-stage oxidation state manipulations. Palladium-mediated enolate vinylation methodology (18 → 20) facilitated construction of the carbon skeleton while minimizing lateral transformations. Additional syntheses of ent-kaurene and Isodon diterpenoids containing TBCCs have been reported; and we direct readers to more specialized recent reviews on this topic for additional illustrative examples.17,23,24

2. Case studies

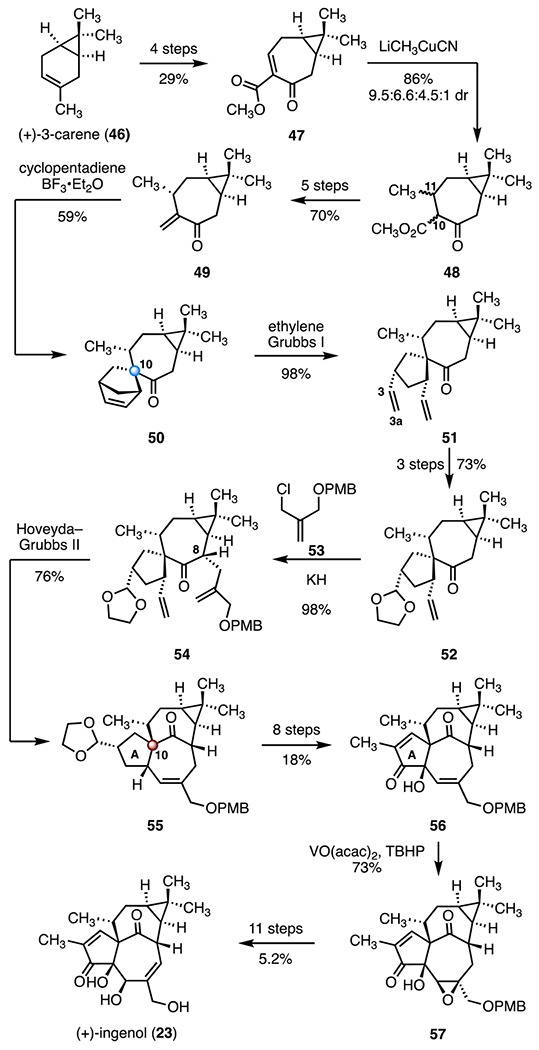

2.1. Ingenol: TBCC embedded in a highly strained terpenoid ring system

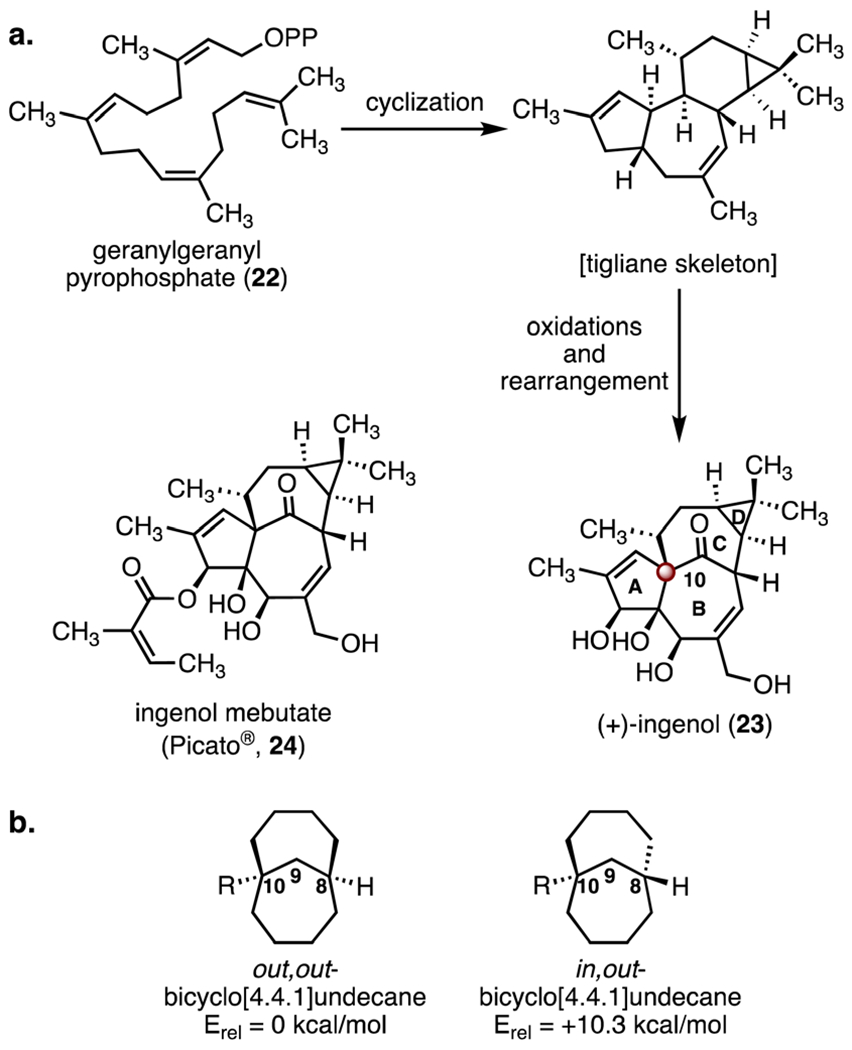

Ingenanes are complex polycyclic diterpenoids derived from the tigliane skeleton (Scheme 4).25 Ingenanes possess a unique 5/7/7/3 tetracyclic system containing an in,out-bridgehead bicyclo [4.4.1]undecane core. The first known member of this family, (+)-ingenol (23), was isolated in 1968 from Euphorbia ingens by Hecker and co-workers.26 The structure of (+)-ingenol was elucidated in 1970 by X-ray crystallography.27 Many natural ingenol derivatives are known, and some possess antiviral and anticancer activities.28–30 The semisynthetic derivative ingenol mebutate (Picato®, 24) was approved for the treatment of actinic keratosis by the US FDA in 2013.31 From a structural perspective, (+)-ingenol (23) contains a C10 TBCC and two highly oxidized rings (A and B rings).32 The in,out-bicyclo[4.4.1]undecane scaffold is calculated to be 10.3 kcal mol−1 higher in energy than the out,out-diastereomer, due to torsional strain.33 Numerous research groups have published synthetic studies toward (+)-ingenol (23).34 Here we discuss syntheses of ingenol (23) by the Winkler,35 Tanino–Kuwajima,36 Wood,37 and Baran groups.38

Scheme 4.

(a) Structure and biosynthesis of (+)-ingenol (23), and the structure of ingenol mebutate (Picato®, 24). (b) Calculated relative energies of out,out- and in,out-bicyclo[4.4.1]undecane diastereomers.

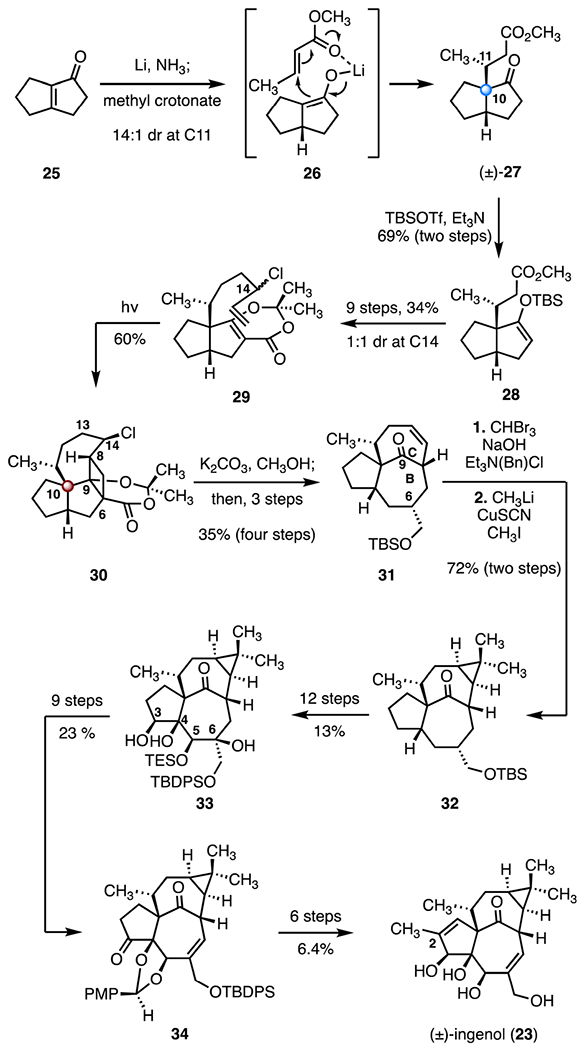

In 2002, Winkler and co-workers reported the first total synthesis of (±)-ingenol (23), employing a tandem [2 + 2] cycloaddition-ring opening as a key step (Scheme 5).35 Their synthesis began with reductive coupling of the cyclopentenone 25 and methyl crotonate.39 Conjugate reduction (lithium, ammonia) of the cyclopentanone 25, followed by a chelation-controlled 1,4-addition of the resulting enolate (26) to methyl crotonate, provided the methyl ester (±)-27 as a 14 : 1 mixture of diastereomers at C11. The C10 all-carbon quaternary center was established with full stereocontrol. The enoxysilane 28 was prepared by treatment of 27 with tert-butyldimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate and triethylamine (69%, two steps). This product was elaborated to the chlorodiene 29 in nine steps and as a ~1 : 1 mixture of C14 diastereomers (34% overall). Intramolecular photocycloaddition of the diene 29 (mercury lamp, 200–400 nm) provided the cyclobutane 30, which contains the C10 TBCC and the desired (8R) configuration. Unexpectedly, the product of 1,2-migration of the chlorine atom (not shown) was also formed. These two products were not separable on preparative scales (60% combined yield, 5 : 2 ratio of 30 and the chlorine migration product). It is noteworthy that the same photocycloaddition of the C14 hydroxyl analog of 29 (not shown) proceeded in only 16% yield.40 Cleavage of the lactone (potassium carbonate, methanol) promoted a Grob fragmentation of the C9–C6 bond; a three-step sequence then provided the ketone 31 (35%, four steps). This approach established the in,out-BC ring system. The gem-dimethylcyclopropane was constructed by addition of dibromocarbene (bromoform, sodium hydroxide, benzyl triethylammonium chloride) to 31, followed by reductive methylation (methyl lithium, copper(i) thiocyanate, iodomethane, 72%, two steps).41 The tetracyclic product 32 contains the complete skeleton of ingenol (23). The triol 33 was synthesized from 32 in twelve steps by sequential oxidations at C3, C4, C5, and C6 (13% overall). The triol 33 was then advanced to the alkene 34 by a nine-step sequence (23% overall). Finally, installation of the C2 methyl substituent, followed by oxidation state manipulations and removal of the protecting groups, completed the synthesis (six steps, 6.4% overall). In sum, the first synthesis of (±)-ingenol (23) was completed in forty-five steps and 0.0068% overall yield.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of (±)-ingenol (23) by Winkler and co-workers.35 TBSOTf = tert-butyldimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate.

In 2003, Tanino, Kuwajima and co-workers disclosed a total synthesis of (±)-ingenol (23), employing a tandem cyclization-rearrangement strategy (Scheme 6).36 The enone 36 was prepared in six steps and 17% overall yield from the alcohol (±)-35. A diastereoselective aldol addition (tert-butyl acetate, lithium diisopropylamide, lithium bromide), followed by a chelation-controlled alkylation (trimethylaluminum, lithium diisopropylamide) and acidic workup (hydrochloric acid) provided the trans-decalin 37 as a single diastereomer (60%, two steps). The cobalt complex 38 was synthesized in seven steps from the ester 37 (59% overall). Treatment of the cobalt complex 38 with the bulky Lewis acid 39 triggered a cyclization reaction that formed the C ring bearing the C11 α-methyl group (not shown); reductive demetalation (lithium, ammonia) afforded the diene 40 (67%, two steps). A two-step sequence was used to introduce the gem-dimethyl cyclopropane (bromoform, sodium hydroxide, benzyl triethylammonium chloride; lithium dimethyl cuprate methyl lithium complex, iodomethane, 67% overall). In a key reaction, directed epoxidation of the allylic alcohol 41 (tert-butyl hydroperoxide, titanium(IV) isopropoxide), followed by Lewis-acid promoted ring-opening rearrangement (trimethylaluminum), provided the tetracycle 43 (76%, two steps). In this approach, the configuration of the C9 hydroxy group was used to direct the formation of the C10 TBCC. The tetracycle 43 was elaborated to the tetraol 44 in twelve steps (35% overall). A ten-step sequence was developed to convert the tetraol 44 to the epoxide 45 (4.7% overall). Finally, reductive cleavage of the bromoepoxide 45 (zinc, ammonium chloride) followed by deprotection (potassium hydroxide, 81%, two steps) generated (±)-ingenol (23). The synthesis was completed in forty-five steps and 0.027% overall yield.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of (±)-ingenol (23) by Tanino and co-workers.36 TBHP = tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

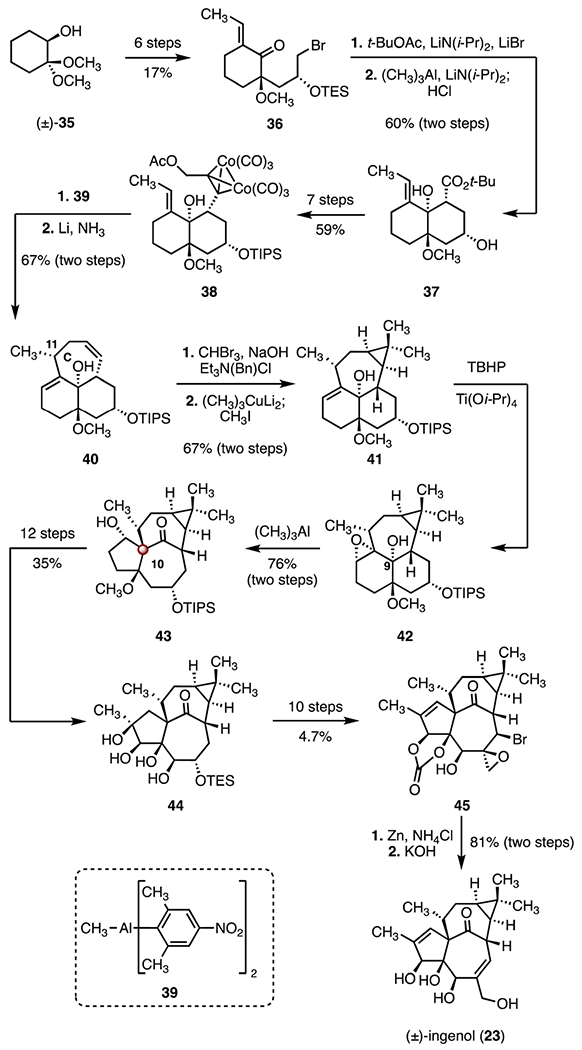

In 2004, Wood and co-workers disclosed a synthetic route to (+)-ingenol (23) that featured a ring-opening metathesis (ROM)–ring-closing metathesis (RCM) cascade (Scheme 7).37 Their synthesis began with (+)-3-carene (46), which was converted in four steps42 to the bicyclic cycloheptenone 47 (29% overall). 1,4-Addition of lithium cyanomethyl cuprate to the ester 47 provided the ketoester 48 as a 9.5 : 6.6 : 4.5 : 1 mixture of C10 and C11 diastereomers (86%). The mixture of keto esters 48 was converted to the exocyclic alkene 49 in five steps (70% overall).43 A substrate-controlled Diels–Alder addition between 49 and cyclopentadiene, promoted by boron trifluoride diethyl etherate complex, afforded the spirocyclic alkene 50, which bears the C10 quaternary center (59%). Ring-opening metathesis (ROM; Grubbs I catalyst, ethylene) furnished the diene 51 (98%).44 Selective functionalization of the C3–C3a alkene provided the acetal 52 (three steps, 73% overall). Deprotonation of 52 (potassium hydride) in the presence of the allylic chloride 53 then formed the cyclization precursor 54, as a single C8 diastereomer (98%). In a key transformation, 54 was converted to the tetracycle 55 by ring-closing metathesis (RCM) promoted by the second-generation Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst (76%). The high conversion of this reaction was attributed to the formation of a more stable trisubstituted alkene in the product 55, which disfavors the reverse ROM reaction. Functionalization of the A-ring (eight steps, 18% overall) then provided the allylic alcohol 56. Directed epoxidation (vanadium(iv) oxide acetylacetonate, tert-butyl hydroperoxide, 73%) furnished the epoxide 57. An eleven-step sequence (5.2% overall) then completed the total synthesis of (+)-ingenol (23). The synthesis was completed in thirty-seven steps and 0.038% overall yield.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of (+)-ingenol (23) by Wood and co-workers.37 TBHP = tert-butyl hydroperoxide, VO(acac)2 = vanadium(IV) oxide acetylacetonate.

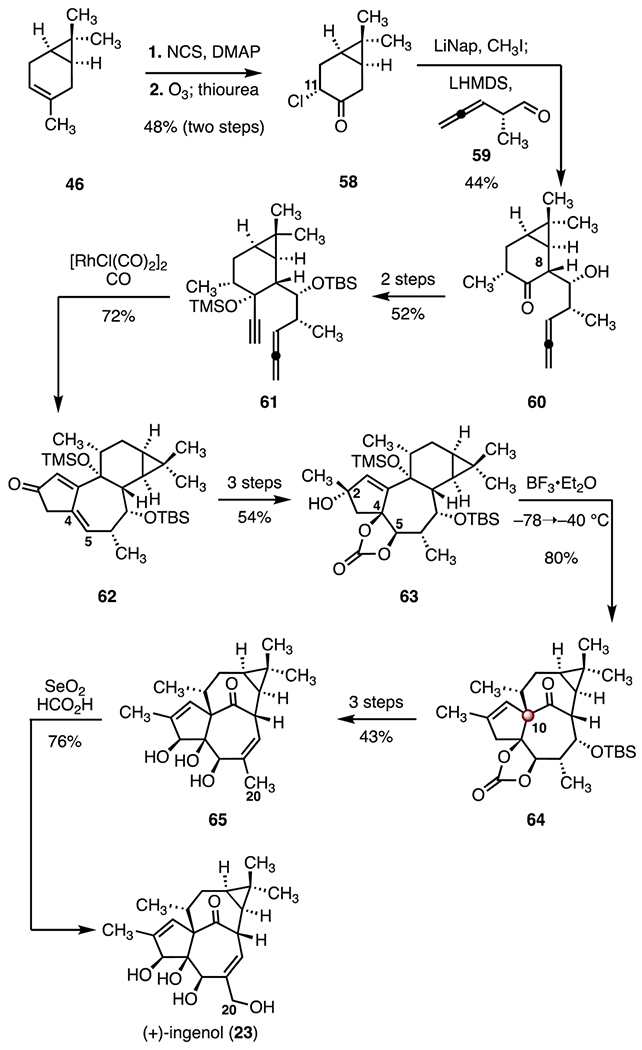

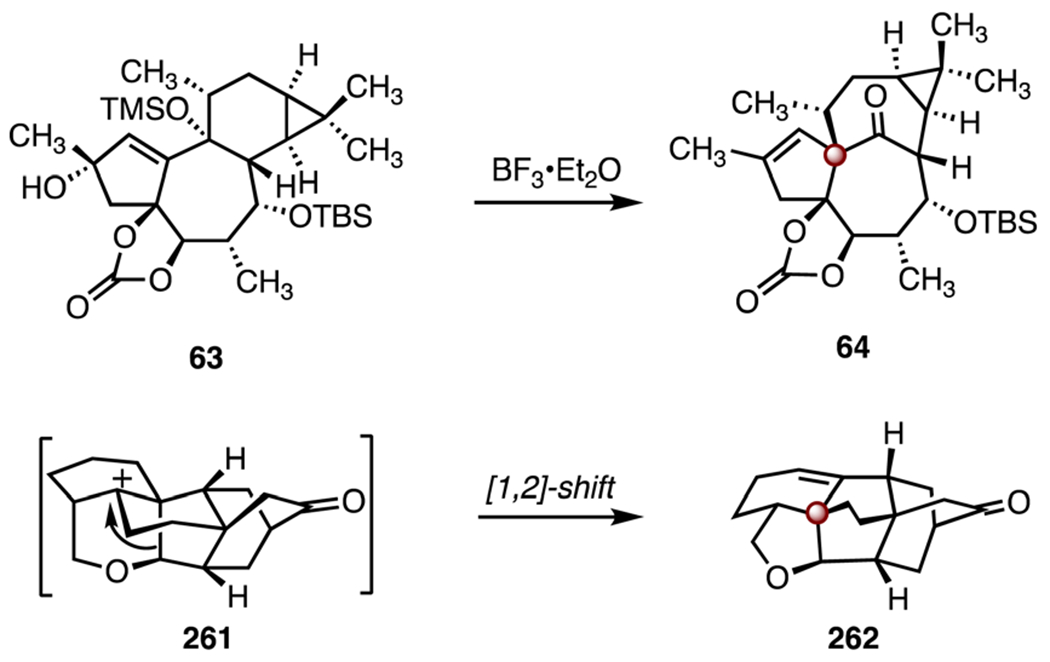

In 2013, Baran and co-workers reported a synthesis of (+)-ingenol (23). They employed a Pauson–Khand cyclization and an allylic pinacol rearrangement as key steps (Scheme 8).38 Their synthesis began with a diastereoselective C11 chlorination (N-chlorosuccinimide, 4-dimethylaminopyridine) of (+)-3-carene (46), followed by oxidative cleavage of the resulting exocyclic alkene (ozone; then, thiourea, 48%, two steps). A one-flask diastereoselective reductive methylation–aldol addition (lithium naphthalenide, iodomethane; then, lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, 59)45 provided the allene 60 as a single diastereomer with the requisite (8R)-configuration (44%). The allene 60 was advanced to the allene-yne 61 in two steps (52% overall). A rhodium-catalyzed Pauson–Khand reaction46 (ruthenium(I) chloride bis(carbonyl) dimer, carbon monoxide) then afforded the cyclopentenone 62 (72%). A three-step sequence provided the tertiary allylic alcohol 63 (54% overall). Exposure of the allylic alcohol 63 to boron trifluoride diethyl etherate complex triggered an allylic pinacol rearrangement, furnishing the ketone 64 with the C10 TBCC (80%). This approach to the ingenane core differs from the work of Tanino and Kuwajima,36 in that a tertiary allylic alcohol, rather than an epoxide, was used as the ionizable functional group. The temperature of this reaction was carefully optimized (−78 to −40 °C) to suppress premature elimination of the C2 alcohol. A three-step sequence was devised to convert the rearrangement product to the triol 65 (43% overall). The synthesis was completed by an allylic oxidation47 of the triol 65 (selenium(IV) oxide, formic acid, 76%). Overall, this synthesis of (+)-ingenol (23) proceeded in fourteen steps and 1.1% overall yield.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of (+)-ingenol (23) by Baran and co-workers.38 NCS = N-chlorosuccinimide, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine, LiNap = lithium naphthalenide.

The C10 TBCC of ingenol (23) serves as the fusion point of the five-membered A ring and the highly strained in,out-bicyclo [4.4.1]undecane (BC rings). Two strategies were developed to access the TBCC within this ring system. The Winkler35 and Wood37 groups constructed the C10 center early in their synthetic routes (see substrates 27 and 50) through a 1,4-addition–Michael addition or a [4 + 2] cycloaddition, respectively. The corresponding cyclization events (29 → 30, 54 → 55) required harsher than usual conditions due to the strained BC ring junction. Tanino, Kuwajima and co-workers,36 as well as Baran38 and co-workers, took advantage of cationic rearrangement strategies to efficiently access this strained system. This allowed them to accomplish the cyclization events by construction of simpler fused tetracyclic ring systems (42 and 63). The stereochemistry at C8 was established early in each route, and the C10 configuration was derived from the C9 tertiary alcohol, which proved to be easier to install with stereocontrol. All four syntheses employed late-stage oxidation sequences, where the incorporation of highly unsaturated synthons (e.g. 59) improved the efficiency of the oxidation sequences.

2.2. Bilobalide: vicinal TBCCs embedded in a highly oxidized terpenoid ring system

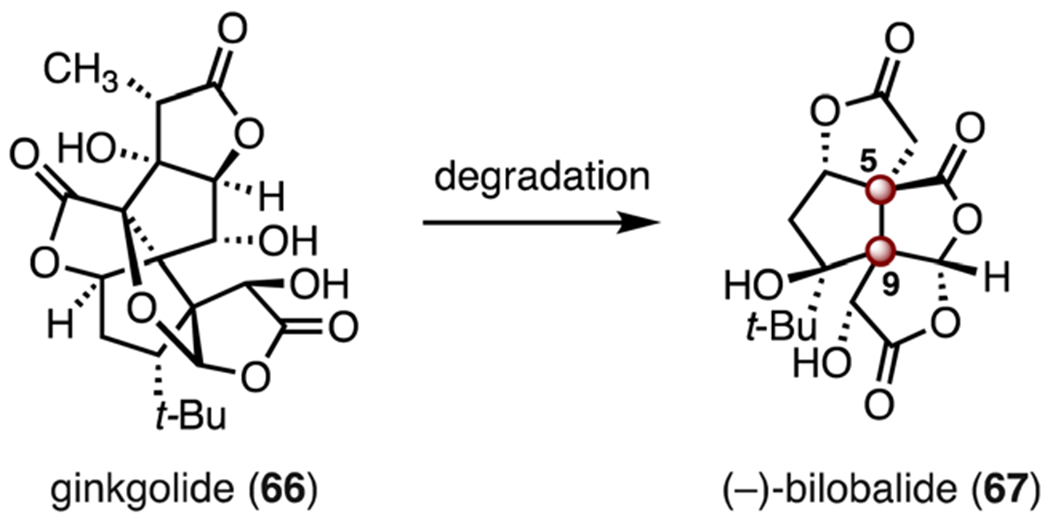

(−)-Bilobalide (67) is a fifteen-carbon tetracyclic trilactone that is derived from biological degradation of the diterpenoid ginkgolide (66, Scheme 9). (−)-Bilobalide (67) was isolated in 1971 from Ginkgo biloba by Nakanishi and co-workers. Its structure was elucidated by NMR spectroscopy.48 A recent study reported that bilobalide (67) inhibits recombinant γ-amino-butyric acid receptors (GABAARs), with an IC50 of 4.6 μM (α1β2γ2L receptor, Xenopus laevis oocytes).49 Additionally, bilobalide (67) exhibits beneficial effects on cognition.50 Structurally, 67 features three adjacent γ-lactones fused to a cyclopentane ring. The C5 and C9 TBCCs are in a vicinal relationship, which further complicates synthetic planning. Here we review the syntheses of bilobalide (67) by the Corey,51 Crimmins,52 and Shenvi laboratories.53

Scheme 9.

Structures of (−)-bilobalide (67) and ginkgolide (66).

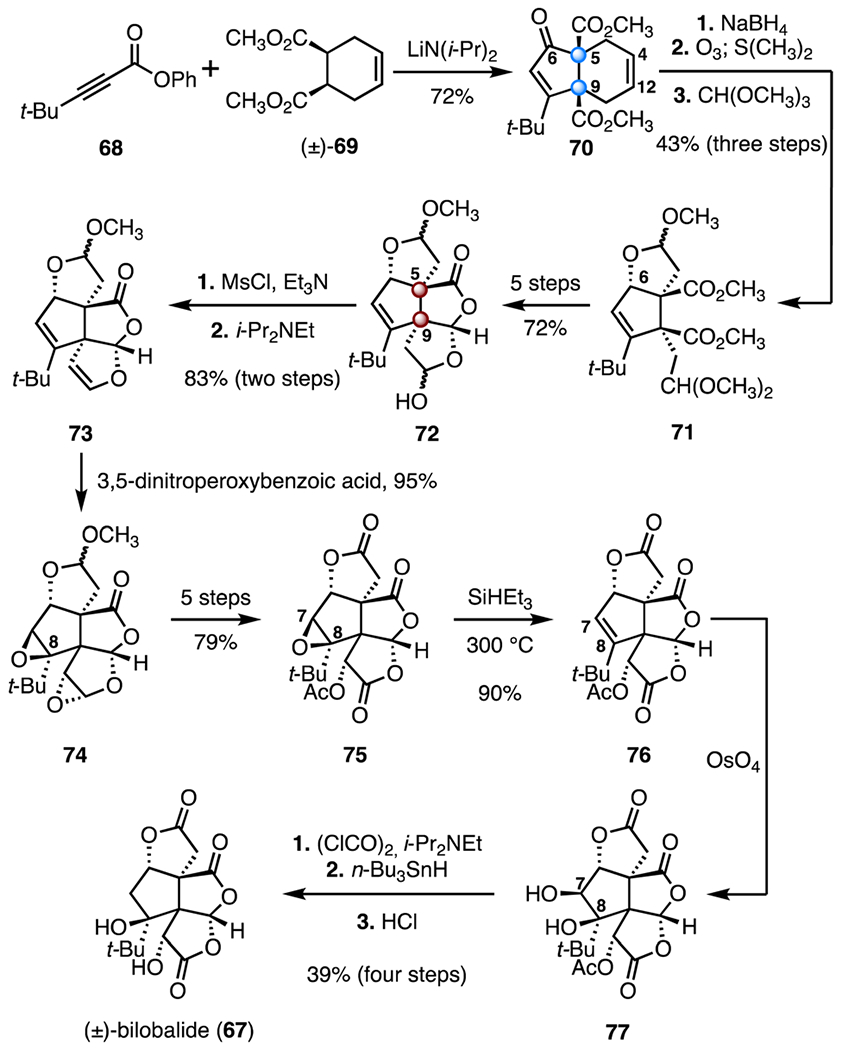

In 1987, Corey and co-workers reported the first total synthesis of (±)-bilobalide (67). The route is notable for its rapid construction of the tetracyclic skeleton (Scheme 10).51 Exposure of a mixture of the ynone 68 and the diester (±)-69 to lithium diisopropylamide triggered a tandem acylation–cyclization reaction, furnishing the enone 70 (72%). This first step provided stereocontrolled construction of the C5 and C9 vicinal quaternary centers. Further investigation revealed that this step likely proceeds through a ketene intermediate.54 Reduction of the C6 carbonyl (sodium borohydride); selective ozonolysis of C4–C12 alkene (ozone; then, dimethyl sulfide), and hemiacetal formation (trimethyl orthoformate) provided the hemiacetal 71 (43%, three steps). A five-step sequence was developed to advance the hemiacetal 71 to the lactone 72, which possesses the full carbon skeleton of the target (72% overall). Dehydration of the hemiacetal (methanesulfonyl chloride, triethylamine; N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 83%, two steps) provided the enol ether 73. Two-fold diastereoselective epoxidation of the enol ether 73 was accomplished by treatment of 73 with 3,5-dinitroperoxybenzoic acid, to furnish the bis(epoxide) 74 (95%); the latter was elaborated to the tris(lactone) 75 in five steps (79% overall). The C7–C8 epoxide was reduced by heating of 75 with a large excess of triethylsilane at elevated temperatures (300 °C), to form the C7–C8 alkene 76 (90%). Finally, dihydroxylation of the C7–C8 alkene of 76 (osmium tetroxide) followed by a selective deoxygenation of the less-hindered C7 alcohol (oxalyl chloride, N,N-diisopropylethylamine; tri-n-butyltin hydride) and deacetylation (hydrochloric acid) completed the synthesis (four steps, 39%). The synthesis of (±)-bilobalide (67) was accomplished in twenty-two steps and 4.9% overall yield.

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of (±)-bilobalide (67) by Corey and co-workers.51 MsCl = methanesulfonyl chloride.

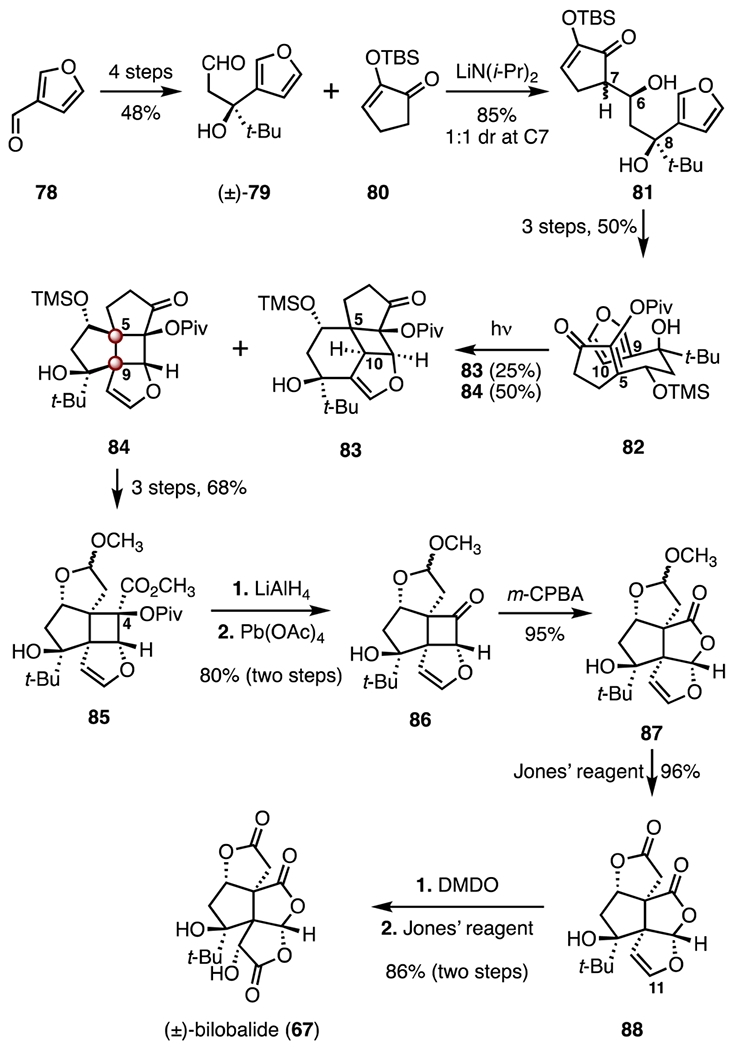

In 1993, Crimmins and co-workers reported a synthesis of (±)-bilobalide (67) that employed an intramolecular [2 + 2] addition to establish the C5 and C9 TBCCs (Scheme 11).52 3-Furaldehyde (78) was converted to the aldehyde (±)-79 by a four-step sequence (48% overall). Fragment coupling by addition of lithium diisopropylamide to a mixture of the aldehyde (±)-79 and the enone 80 generated the diol 81 in 85% yield and as a 1 : 1 mixture of diastereomers at C7. A three-step sequence was developed to convert the mixture of diols 81 to the rearranged enone 82 (50% overall). An intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition was performed by irradiation of 82, to provide a regioisomeric mixture of the cyclobutanes 83 (25%) and 84 (50%). The stereoselectivity of this addition was thought to derive from cyclization of the conformer shown for 82, wherein the tert-butyl and the trimethylsilyloxy substituents occupy pseudoequatorial orientations. A three-step sequence then generated the ketal 85 (68% overall). Reduction (lithium aluminum hydride) followed by oxidative cleavage (lead(IV) acetate) afforded the cyclobutanone 86 (80%, two steps). Baeyer–Villiger oxidation of the cyclobutanone 86 (m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid) provided the lactone 87 (95%). Finally, the bis(lactone) 88, formed by oxidation of 87 (Jones’ reagent, 96%), was subjected to sequential oxidations (dimethyldioxirane; Jones’ reagent, 86%, two steps) to furnish the target. The synthesis of (±)-bilobalide (67) was completed in eighteen steps with 4.4% overall yield.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of (±)-bilobalide (67) by Crimmins and co-workers.52 m-CPBA = m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, DMDO = dimethyldioxirane.

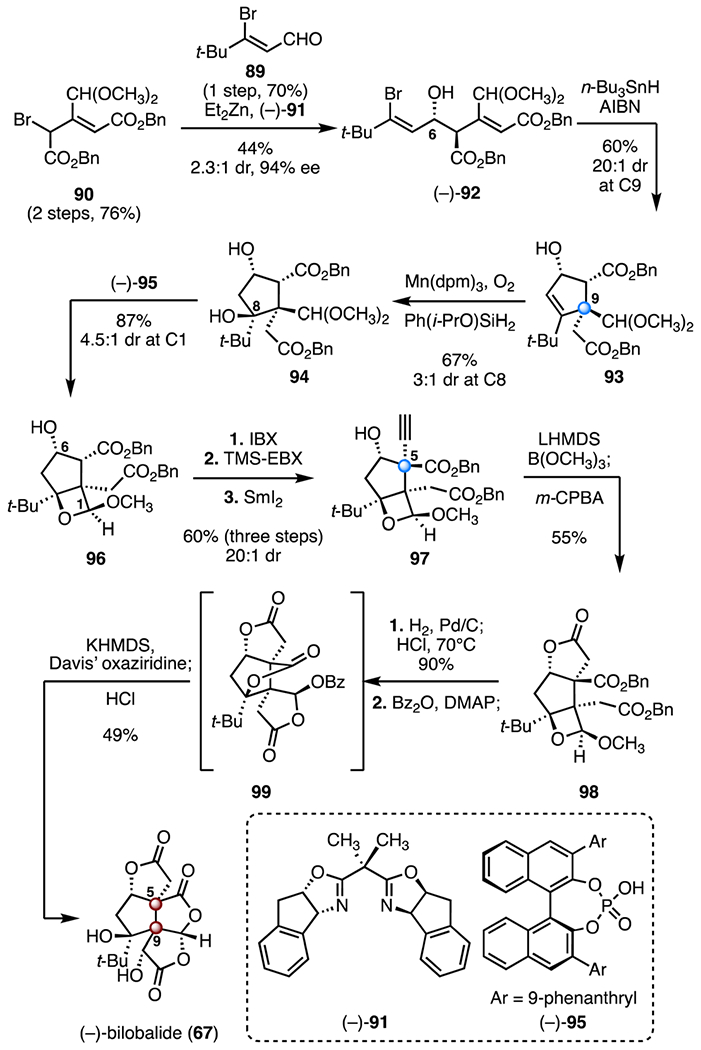

In 2019, Shenvi and co-workers disclosed an enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-bilobalide (67) employing an asymmetric Reformatsky addition, a solvent-controlled Mukaiyama hydration and a selective alkyne oxidation as key steps (Scheme 12).53 The synthesis began with an asymmetric vinylogous Reformatsky addition of the allylic bromide 90 (prepared in two steps from benzyl 2-(triphenylphosphaneylidene)acetate) to the aldehyde 89 (prepared in one step from pinacolone, 70%) promoted by diethylzinc and the “indabox” ligand (−)-91.55,56 The addition product (−)-92 was obtained in 44% yield, 94% ee, and with 2.3 : 1 diastereoselectivity at C6. Stereoselective reductive cyclization (tri-n-butyltin hydride, azobisisobutyronitrile) provided the cyclopentene 93 (60%, 20 : 1 dr at C9), which contains the desired C9 all-carbon quaternary center. Mukaiyama hydration (tris(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionato)manganese(III), isopropoxy(phenyl)silane, oxygen, 67%) of the cyclopentene 93 provided the hindered tertiary C8 alcohol 94 (3 : 1 dr at C8).57 Treatment of the alcohol 94 with the chiral phosphoric acid derivative (−)-95 generated the oxetanyl acetal 96 with 4.5 : 1 diastereoselectivity at C1 (87%). Oxidation of the C6 hydroxyl of 96 (2-iodoxybenzoic acid), followed by C5 alkynylation using trimethylsilyl ethynylbenziodoxolone,58 and reduction of the C6 ketone (samarium(II) iodide), furnished the alkyne 97 (60% over three steps, 20 : 1 dr). In this three-step procedure, the C5 quaternary center was established by electrophilic alkynylation. Treatment of the alkyne 97 with lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide and trimethyl borate, followed by addition of m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, provided the lactone 98 (55%). Removal of the benzyl ester protecting groups (palladium on carbon, hydrogen; then, hydrochloric acid), followed by a benzoate ester-assisted one-pot translactonization–α-hydroxylation cascade through the spirocyclic intermediate 99 (benzoyl anhydride, 4-dimethylaminopyridine; then, potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, Davis’ oxaziridine; then, hydrochloric acid) accomplished the final oxidations and skeletal rearrangement (44%, two steps). The total synthesis of (−)-bilobalide (67) was completed in twelve steps and 1.7% overall yield.

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of (−)-bilobalide (67) by Shenvi and co-workers.53 AIBN = azobisisobutyronitrile, Mn(dpm)3 = tris(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionato)manganese(III), IBX = 2-iodoxybenzoic acid, TMS-EBX = trimethhylsilyl ethynylbenziodoxolone, LHMDS = lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, m-CPBA = m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine, KHMDS = potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide.

The vicinal C5 and C9 TBCCs in (−)-bilobalide (67) are the fusion points of a cyclopentane ring and three γ-lactones. A common element of all three synthetic routes is installation of the quaternary centers before lactone formations, by CγO bond construction. The synthesis by Corey and co-workers51 generated the vicinal quaternary centers by an acylation–cyclization reaction (68 + 69 → 70), while Crimmins and co-workers52 introduced these centers through a [2 + 2] cycloaddition (82 → 84). By comparison, Shenvi and co-workers53 constructed these centers in a stepwise fashion (92 → 93, 96 → 97). Corey and co-workers51 formed the C6 and C8 stereocenters after introducing C5 and C9 (70 → 71, 73 → 74). In contrast, the Crimmins synthesis52 introduced them in the linear cyclization precursor (82) early in the route. The Shenvi synthesis53 constructed these centers through two novel reactions before (89 + 90 → 92) and after (93 → 94) introduction of the all-carbon five-membered ring.

2.3. Waihoensene: vicinal TBCCs within a terpenoid ring system bearing sparse heteroatom functionality

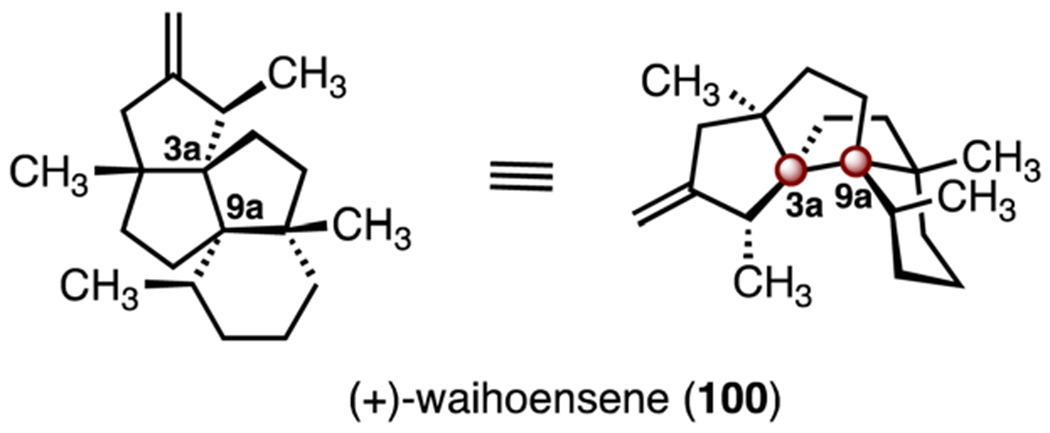

The tetracyclic diterpene (+)-waihoensene (100) was isolated in 1997 by Weavers and co-workers from the New Zealand podocarp Podocarpus totara var. waihoensis. Its structure was elucidated by NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 13).59 Like (−)-bilobalide (67), (+)-waihoensene (100) possess two vicinal TBCCs, at C3a and C9a. Instead of lactones, however, the ring system of (+)-waihoensene (100) contains only carbon atoms. The absence of functional group handles in the target creates challenges for synthetic planning. To date, five total syntheses of waihoensene (100) have been reported; each will be discussed here.60–64

Scheme 13.

Structure of (+)-waihoensene (100).

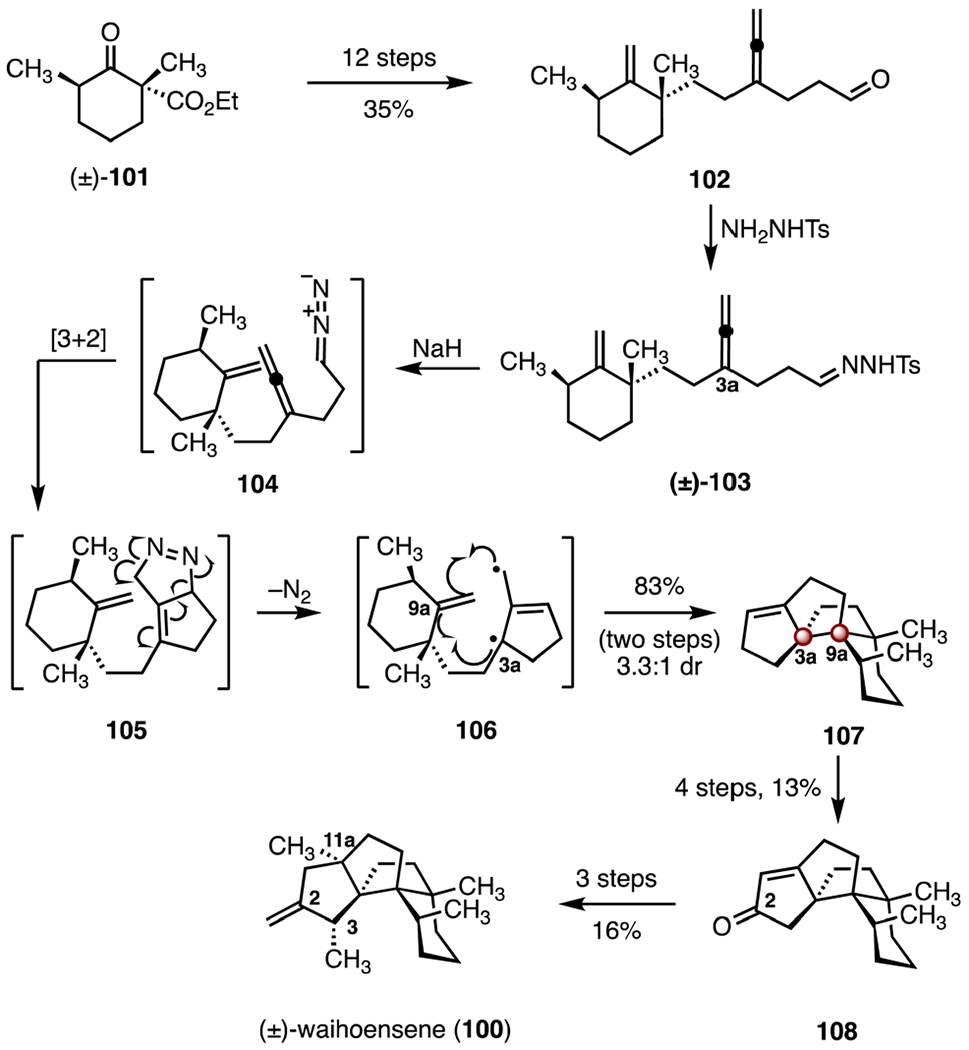

In 2017, Lee and co-workers disclosed a total synthesis of (±)-waihoensene (100) that employed a cycloaddition–fragmentation–cyclization cascade to construct the carbon skeleton (Scheme 14).60 The allene 102 was prepared in twelve steps and 35% yield from the known ketoester (±)-101.65 The hydrazone 103 was obtained from the allene 102 by condensation (p-toluenesulfonyl hydrazide). Treatment with sodium hydride provided the diazoalkane 104, which underwent an intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition, extrusion of dinitrogen, and cyclization of the resulting trimethylenemethane diyl intermediate 106, to furnish the tetracyclic alkene 107, which bears the C3a and C9a TBCCs (83%, 3.3 : 1 dr, two steps). A similar strategy was employed in the synthesis of (−)-crinipellin A by the same group.66 A four-step sequence was developed to transform the alkene 107 to the enone 108 (13% overall). Stereoselective installation of the C3 and C11a methyl substituents and ketone methylenylation provided (±)-waihoensene (100; 16% over three steps). The synthesis of (±)-waihoensene (100) was completed in twenty-one steps and 0.60% overall yield.

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of (±)-waihoensene (100) by Lee and co-workers.60 NH2NHTs = p-toluenesulfonyl hydrazide.

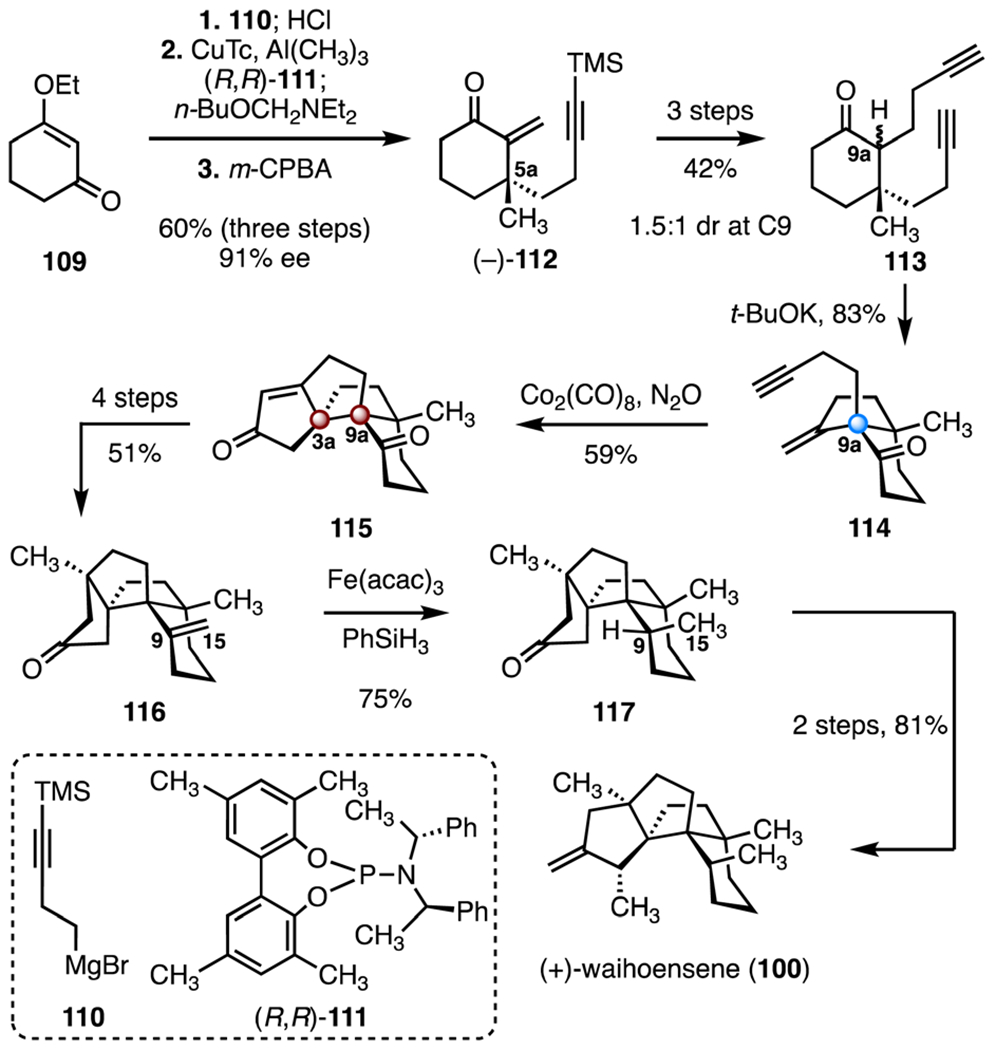

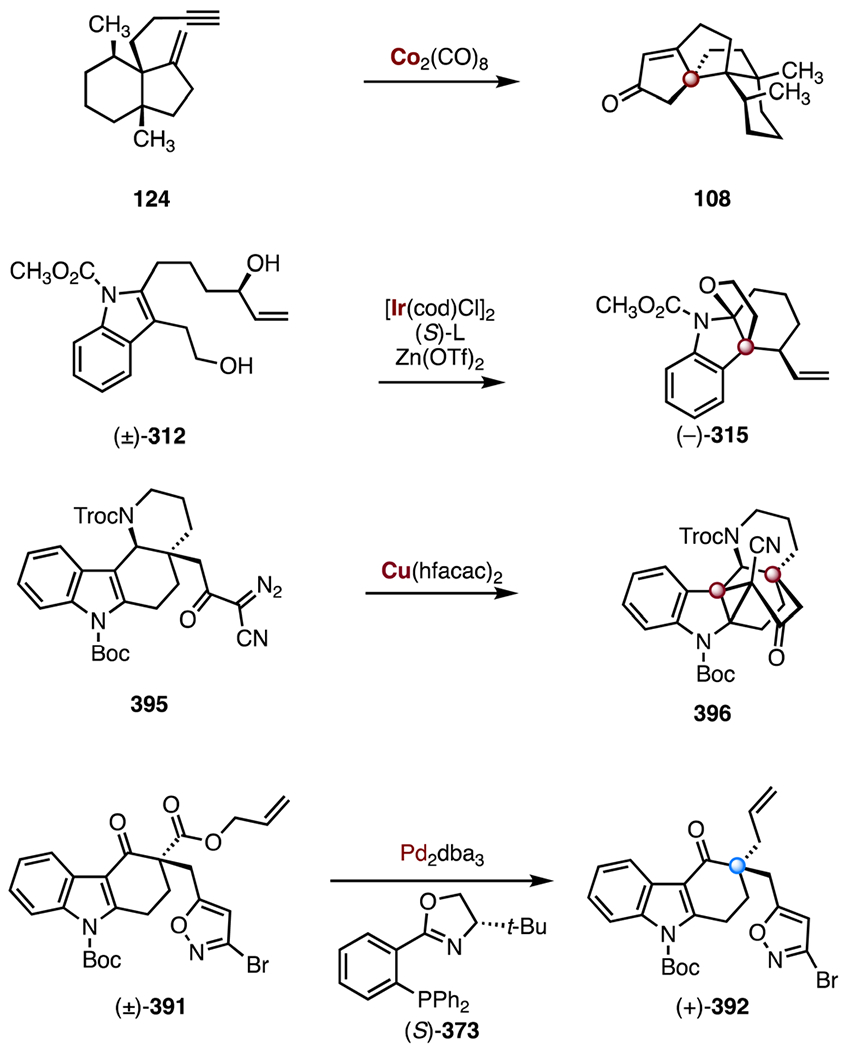

In 2020, Yang and co-workers reported the first enantioselective synthesis of (+)-waihoensene (100). Their synthetic route employed Conia-ene and Pauson–Khand reactions to construct the carbon skeleton (Scheme 15).61 The synthesis began with addition of the Grignard reagent 110 to 3-ethoxycyclohexenone (109), followed by hydrolysis of the 1,2-addition product (hydrochloric acid). Enantioselective, copper-catalyzed 1,4-addition of trimethylaluminum (copper(I) thiophene-2-carboxylate, (R,R)-111) generated a stable aluminum enolate with the established C5a quaternary center (not shown). Addition of N-(butylmethoxy)-N-ethylethanamine, followed by oxidative elimination (m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid), produced the enantioenriched enone (−)-112 (60%, three steps, 91% ee).67 A three-step sequence was developed to convert the enone (−)-112 to the diyne 113 (42% overall, 1.5 : 1 mixture of diastereomers at C9a). A base-promoted Conia-ene reaction (potassium tert-butoxide) furnished the enyne 114, which bears the quaternary stereogenic center at C9a (83%). A Pauson–Khand annulation (dicobalt octacarbonyl, nitrous oxide) then produced the enone 115 (59%).68 By this approach, the configuration of the vicinal C3a and C9a TBCCs were established by a stereochemical relay from C9a. A four-step sequence then provided the alkene 116 (51% overall). Diastereoselective hydrogenation of the C9–C15 alkene of 116 (iron(III) acetylacetonate, phenylsilane, 75%) delivered the ketone 117.69 A two-step sequence was developed to convert the ketone 117 to (+)-waihoensene (100; 81% overall). The synthesis of (+)-waihoensene (100) was completed in fifteen steps and 3.8% overall yield.

Scheme 15.

Synthesis of (+)-waihoensene (100) by Yang and co-workers.61 CuTc = copper(I) thiophene-2-carboxylate, m-CPBA = m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, Fe(acac)3 = iron(III) acetylacetonate.

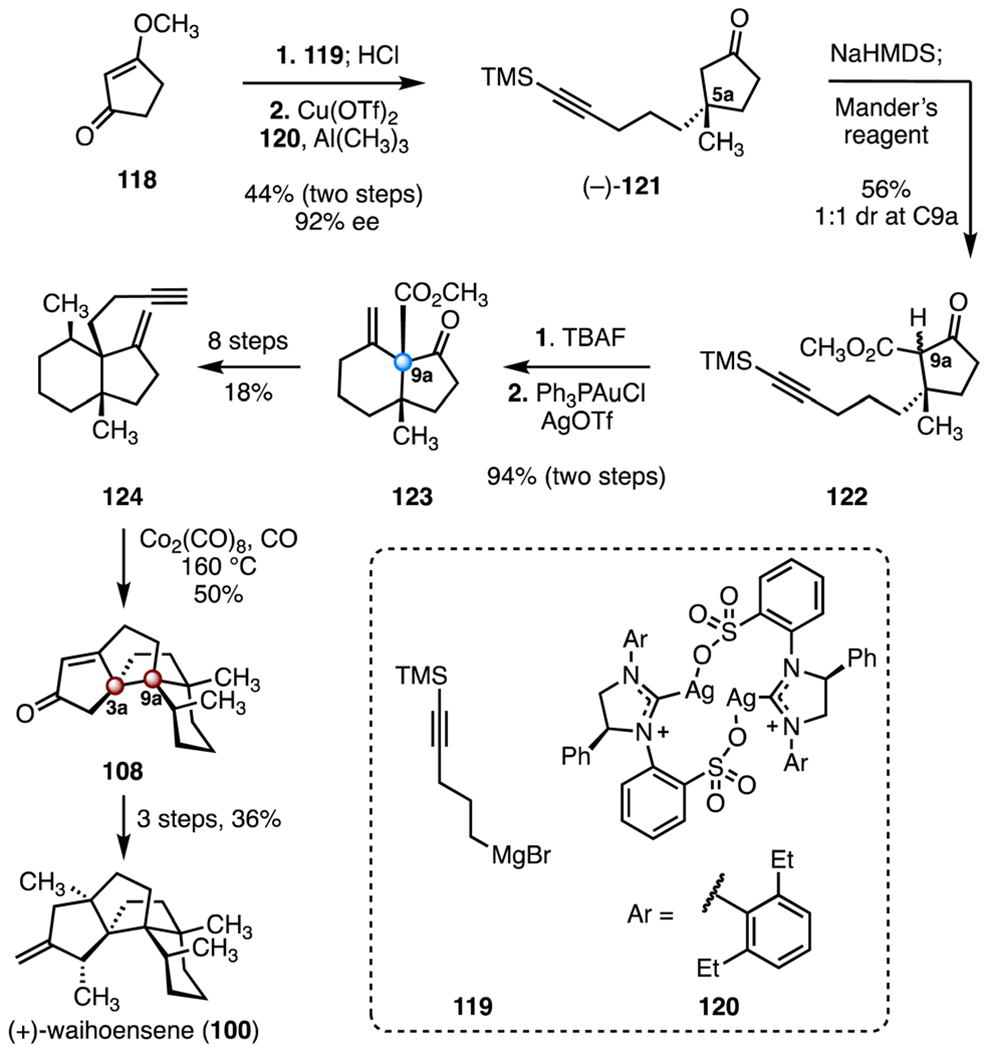

In the same and the subsequent years, two additional enantioselective syntheses of (+)-waihoensene (100) were disclosed by Snyder and Gaich.62,63 Snyder’s synthesis also relied on Conia-ene and Pauson–Khand reactions to form the carbon skeleton, though the implementation of the transformations was distinct (Scheme 16). The Snyder synthesis began with addition of the alkyl Grignard reagent 119 to 3-methoxycyclopentenone (118). Hydrolysis of the 1,2-addition product was achieved by treatment with hydrochloric acid on workup (product not shown). An enantioselective conjugate addition of trimethylaluminum was promoted by the N-heterocyclic carbene complex 120 and copper(n) trifluoromethanesulfonate, to provide the ketone (−)-121 (44%, two steps, 92% ee).70 Deprotonation of the ketone within 121 (sodium bis(trimethylsilyl) amide), followed by addition of Mander’s reagent, formed the ketoester 122 as a 1 : 1 mixture of C9a diastereomers (56%), along with a 1 : 1 diastereomeric mixture of its constitutional isomer (31%, not shown). Removal of the silyl protecting group (tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride), followed by a gold-catalyzed Conia-ene reaction (triphenylphosphine gold(I) chloride, silver(I) trifluoromethanesulfonate) generated the hydrindane 123, which bears the C9a quaternary stereogenic center (94%, two steps).71 An eight-step sequence was developed to advance the bicycle 123 to the enyne 124 (18% overall). A Pauson–Khand annulation (dicobalt octacarbonyl, carbon monoxide) then provided the tetracycle 108, an intermediate in the Lee synthesis (50%).60 This reaction required unusually high temperatures (160 °C), likely due to the steric congestion of the substrate. The tetracycle 108 was advanced to (+)-waihoensene (100) in three steps (36% overall). The synthesis was completed in seventeen steps and 0.75% overall yield.

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of (+)-waihoensene (100) by Snyder and co-workers.62 Cu(OTf)2 = copper(II) trifluoromethanesulfonate, NaHMDS = sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, TBAF = tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride, AgOTf = silver(I) trifluoromethanesulfonate.

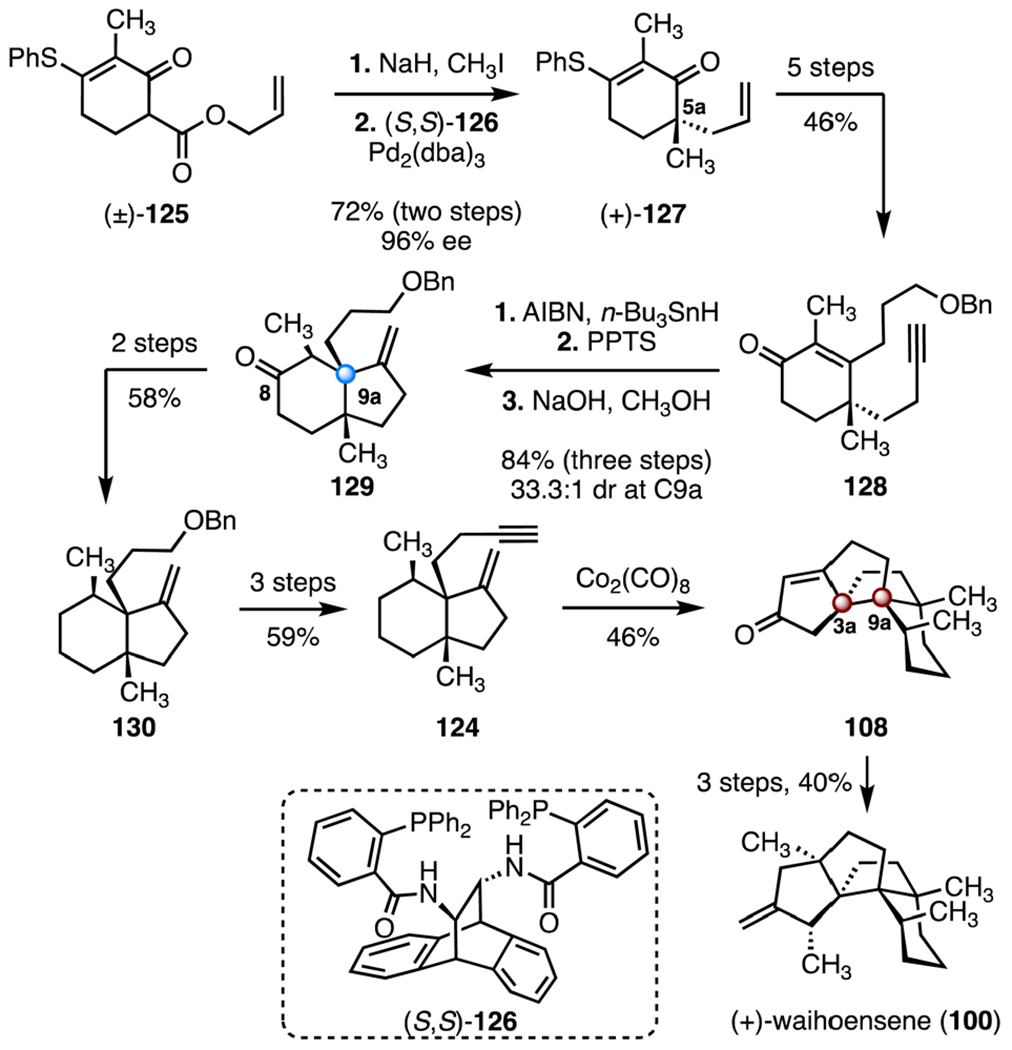

The Gaich laboratory also employed a Pauson–Khand annulation as a key step, but these researchers developed a diastereoselective radical cyclization rather than a Conia-ene reaction to establish the C9a center (Scheme 17). The synthesis began with an α-methylation of the β-ketoester (±)-125 (sodium hydride, iodomethane), followed by an enantioselective decarboxylative allylic alkylation promoted by the chiral ligand (S,S)-126 and tris(dibenzylideneacetone) dipalladium, which provided the enantioenriched alkene (+)-127 (72% over two steps, 96% ee).72 A five-step sequence was developed to transform the alkene (+)-127 to the alkyne 128 (46% overall). A radical cyclization (tri-n-butyltin hydride, azobisisobutyronitrile), destannylation (pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate), and α-epimerization (sodium hydroxide, methanol) then formed the bicyclic ketone 129, which contains the C9a quaternary center (84% over three steps, 33.3 : 1 dr at C9). The C8 carbonyl was reduced by a two-step sequence (58% overall) to provide the bicycle 130, which was converted to the enyne 124 (59%, three steps). Pauson–Khand annulation (dicobalt octacarbonyl) provided the enone 108 (46%). A three-step sequence was developed to obtain (+)-waihoensene (100) (40% overall). Thus, the route to (+)-waihoensene (100) was completed in nineteen steps and 1.8% overall yield.

Scheme 17.

Synthesis of (+)-waihoensene (100) by Gaich and co-workers.63 Pd2(dba)3 = tris(dibenzylideneacetone) dipalladium, AIBN = azobisisobutyronitrile, PPTS = pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate.

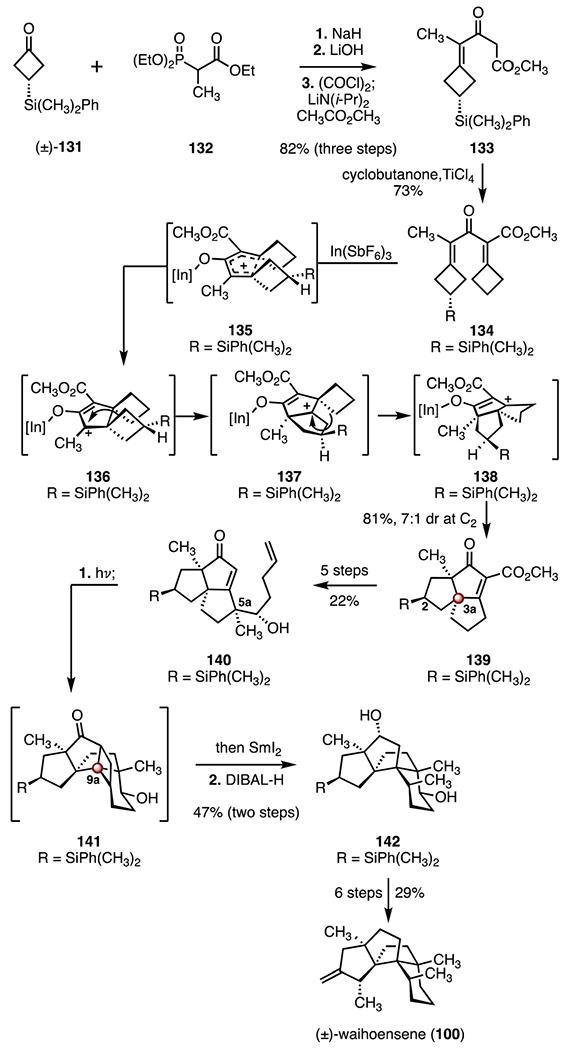

In 2022, Tu and co-workers reported a total synthesis of (±)-waihoensene (100) that employed a Nazarov cyclization and a double ring expansion cascade as key steps (Scheme 18).64 The synthesis began with a Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons olefination of the silylated cyclobutanone (±)-131 (132, sodium hydride). Ester hydrolysis followed by a Dieckmann condensation (lithium hydroxide; oxalyl chloride; lithium diisopropylamide, methyl acetate) then furnished the β-ketoester 133 (82%, three steps). Titanium-mediated aldol dehydration using cyclobutanone as electrophile furnished the bis(enone) precursor 134 (73%). In a remarkable transformation, treatment of 134 with indium(III) hexafluoroantimonate provided the angular tricycle 139 in 81% yield and 7 : 1 dr at C2. This cascade reaction was proposed to comprise a Nazarov cyclization (through 135) to afford the cationic intermediate 136, sequential 1,2-migrations (136 → 137, 137 → 138), proton elimination, and isomerization (138 → 139). The enone 139 bears the C3a TBCC. The diene 140 was then accessed by a five-step sequence (22% overall). Irradiation of the diene 140 (350 nm) induced a [2 + 2] cycloaddition to provide the pentacyclic intermediate 141, which bears the C9a TBCC. Subsequent reductive ring-opening (samarium(II) iodide) and ketone reduction (diisobutylaluminum hydride) delivered the tetracycle 142 (47%, two steps). A six-step procedure was developed to advance the tetracycle 142 to the target (29% overall). The total synthesis of (±)-waihoensene (100) was completed in eighteen steps and 1.5% overall yield.

Scheme 18.

Synthesis of (±)-waihoensene (100) by Tu and co-workers.64 DIABL-H = diisobutylaluminum hydride.

In the syntheses discussed above, the contiguous stereocenters C5a, C9a, C3a, C11a, including the C9a and C3a TBCCs, were constructed by three approaches. In the Yang,61 Snyder,62 and Gaich63 syntheses, the C5a quaternary center was introduced by stereoselective 1,4-addition (109 → 112, 118 → 121) or decarboxylative allylic alkylation (125 → 127), followed by Pauson–Khand cyclizations (114 → 115, 124 → 108), to form the C3a and C9a TBCCs. The configuration of C5a was relayed to the C9a and C3a TBCCs. Both the Lee60 and the Tu64 syntheses took advantage of novel cyclization strategies to construct these centers. In the Lee synthesis,60 a linear precursor 102 was first prepared. Tandem cycloaddition of this precursor was used to construct the C3a and C9a TBCCs from planar carbon centers. In the Tu synthesis,64 the cyclization cascade produced the tricyclic structure 139 and the C3a TBCC. Stereoselective installation of the C5a quaternary center by similar carbonyl chemistry occurred before the generation of the C9a TBCC by a [2 + 2] cycloaddition (140 → 141).

2.4. Epicolactone: congested cluster of TBCCs within a highly unsaturated polyketide ring system

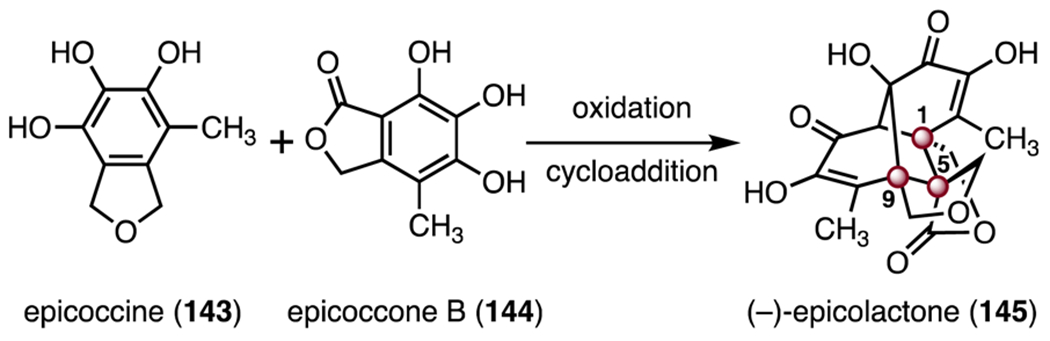

(−)-Epicolactone (145) is a secondary metabolite isolated from sugarcane by Marsaioli and co-workers in 2012.73 Biosynthetically, (−)-epicolactone (145) is derived from the oxidative coupling of epicoccone B (144) and epicoccine (143, Scheme 19).74 (−)-Epicolactone (145) possesses antifungal and antimicrobial activities.75 Structurally, (−)-epicolactone (145) contains three TBCCs at C1, C5 and C9. The syntheses of epicolactone (145) by the Trauner76 and Carreira77 laboratories are discussed below.

Scheme 19.

Structure of (−)-epicolactone (145) and its biosynthetic precursors.

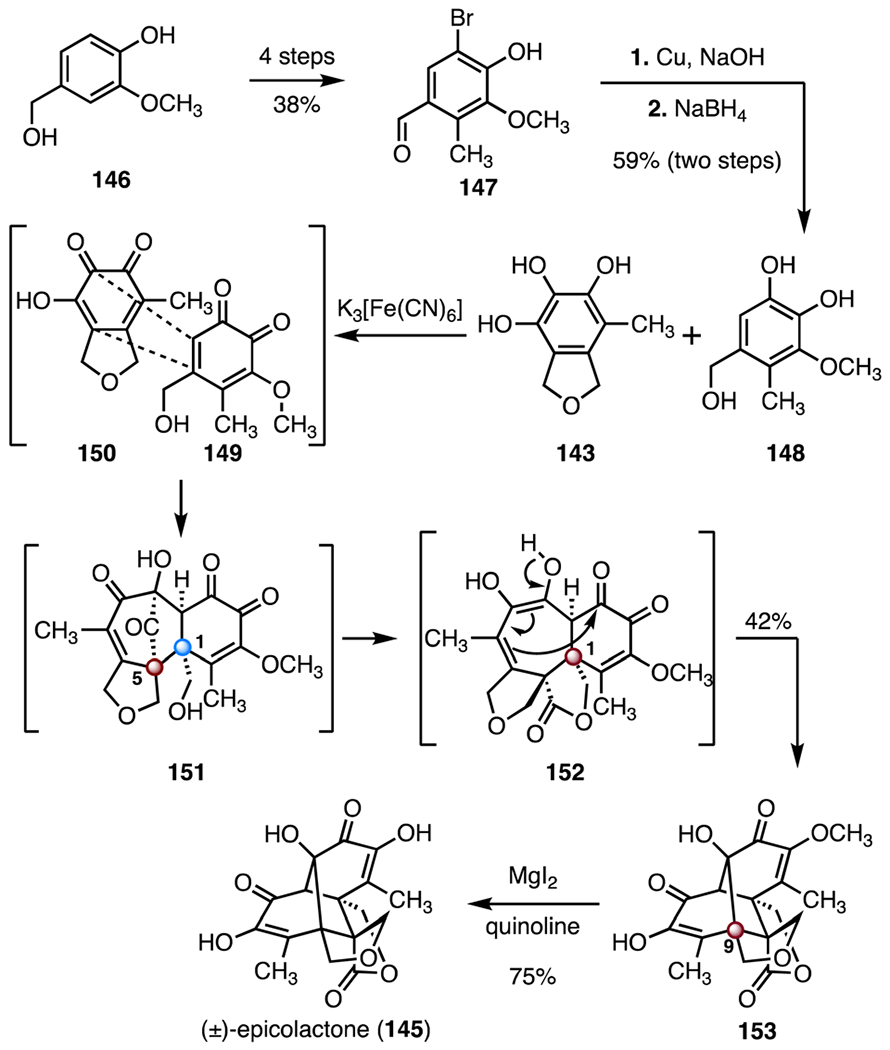

The Trauner group developed a biomimetic route to (±)-epicolactone (145, Scheme 20).76 The synthesis began with preparation of the catechol 148 as a synthetic surrogate of the natural precursor epicoccone B (144). A four-step sequence was developed to convert 4-(hydroxymethyl)-2-methoxyphenol (146) to the aryl bromide 147 (38% overall).78 Substitution of the bromide function by hydroxide (copper, sodium hydroxide), followed by aldehyde reduction (sodium borohydride), provided the catechol 148 (59%, two steps). Treatment of a mixture of the catechol 148 and epicoccine (143)79 with potassium ferrocyanide initiated a biomimetic cyclization-rearrangement cascade. It was proposed that the substrates were oxidized to the ortho-quinones 149 and 150; a spontaneous intermolecular [5 + 2] cycloaddition then generated the tetracyclic intermediate 151, which contains the C1 quaternary center and the C5 TBCC. Intramolecular translactonization formed the dienol 152. Finally, an intramolecular aldol addition afforded the bis(enone) 153. Cleavage of the methyl ether (magnesium iodide, quinoline) then provided (±)-epicolactone (145; 75%). By this biomimetic approach, (±)-epicolactone (145) was obtained in eight steps and 7.1% overall yield.

Scheme 20.

Synthesis of (±)-epicolactone (145) by Trauner and co-workers.76

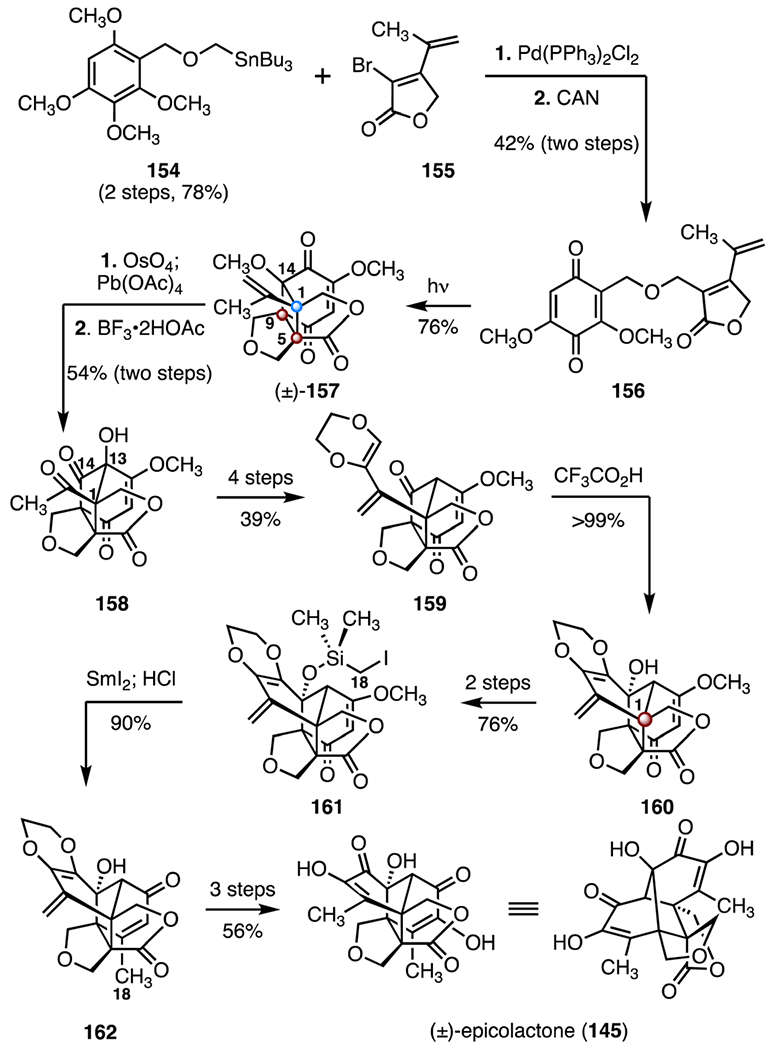

In 2018, Carreira and co-workers reported a synthesis of (±)-epicolactone (145) that employed a [2 + 2] cycloaddition–ring expansion cascade (Scheme 21).77 The synthesis began with a Stille coupling between the stannane 154 (two steps from 2,3,4,6-tetramethoxybenzaldehyde, 78%) and the vinyl bromide 155 80 using bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) chloride as precatalyst. Oxidative demethylation (ceric ammonium nitrate) then provided the ether-linked bicycle 156 (42%, two steps). Irradiation of the bicycle 156 using 400–450 nm light promoted an intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition,81 to provide the cyclic ether (±)-157 (76%). The C1 quaternary center and the C5 and C9 TBCCs were established in this single transformation. Oxidative cleavage of the terminal olefin (osmium(VII) oxide; then, lead(IV) acetate) followed by a 1,2-alkyl shift (boron trifluoride acetic acid complex) produced the methyl ketone 158 (54%, two steps).82 In this step, a Lewis acid-promoted demethylation of the C14 ether triggered the C14–C1 bond migration. The methyl ketone 158 was advanced to the enol ether 159 by a four-step sequence (39% overall). A Prins cyclization (trifluoroacetic acid, >99%) produced the alcohol 160, which bears the C1 TBCC. A two-step sequence was then developed to convert the alcohol 160 to the iodomethyl silyl ether 161 (76% overall). Treatment of the silyl ether 161 with samarium(II)83 followed by exposure to hydrochloric acid provided the β-methylenone 162 (90%). The synthesis was completed by removal of the ethylene unit in 162 (three steps, 56%). The synthesis of (±)-epicolactone (145) was completed in eighteen steps and 2.0% overall yield.

Scheme 21.

Synthesis of (±)-epicolactone (145) by Carreira and co-workers.77 CAN = ceric ammonium nitrate.

(−)-Epicolactone (145) possesses three contiguous C1, C5, and C9 TBCCs. Both the Trauner76 and Carreira77 syntheses employed cycloaddition reactions to construct the congested stereocenters. The Trauner synthesis76 employed a bimolecular [5 + 2] cycloaddition (149 + 150 → 151) to form the C1 quaternary center and C5 TBCC, followed by a biomimetic cascade to introduce the C9 TBCC. The Carreira synthesis77 utilized the tethered precursor 156 to achieve a unimolecular [2 + 2] cyclization, which formed the C1 quaternary center, as well as the C5 and C9 TBCCs in a single step. The C1-fused all-carbon ring was installed late-stage by a Prins cyclization (159 → 160).

2.5. Hetisine alkaloids: TBCCs within a complex polycyclic terpenoid alkaloid

Hetisine natural products are a family of C20-diterpenoid alkaloids isolated from the Aconitum, Consolida, Delphinium, Rumex, and Spiraea genera. They display a diverse spectrum of biological activities including antiarrhythmic, antitumor, insecticidal, antimicrobial and antiviral activities.84 Hetisines contain a heptacyclic carbon skeleton comprised of a bicyclo [2.2.2]octane core and N–C6 and C14–C20 linkages (Scheme 22). The skeleton contains TBCCs at C8 and C10. Here we discuss syntheses of (±)-nominine (175) by Muratake and Natsume85,86 and Gin.87 Additionally we discuss syntheses of (+)-cossonidine (197) and (+)-spirasines IV (208) and XI (209) by the Sarpong88 and Zhang laboratories.89

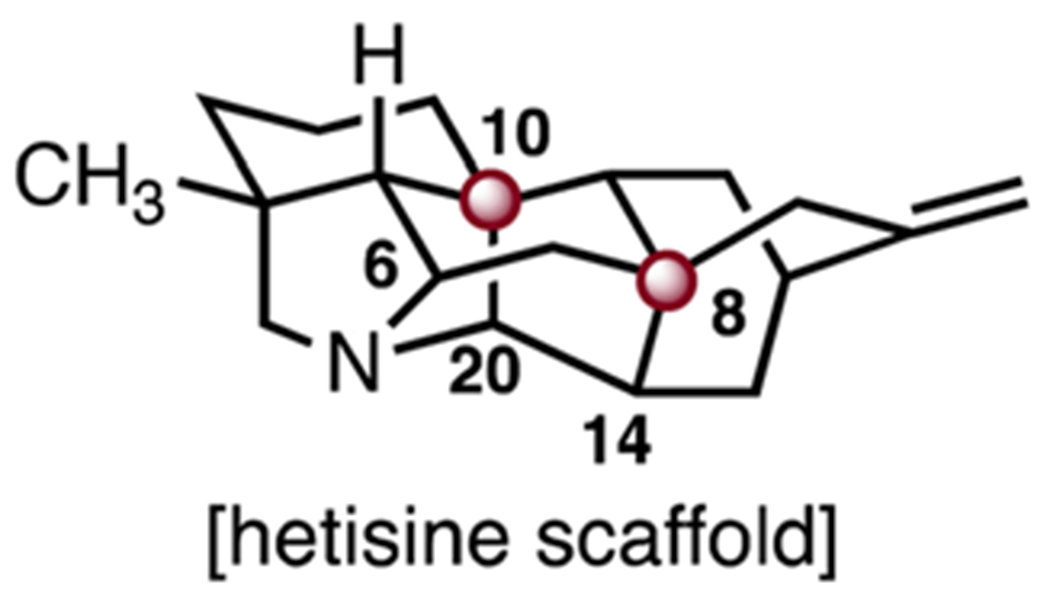

Scheme 22.

Structure of the hetisine scaffold.

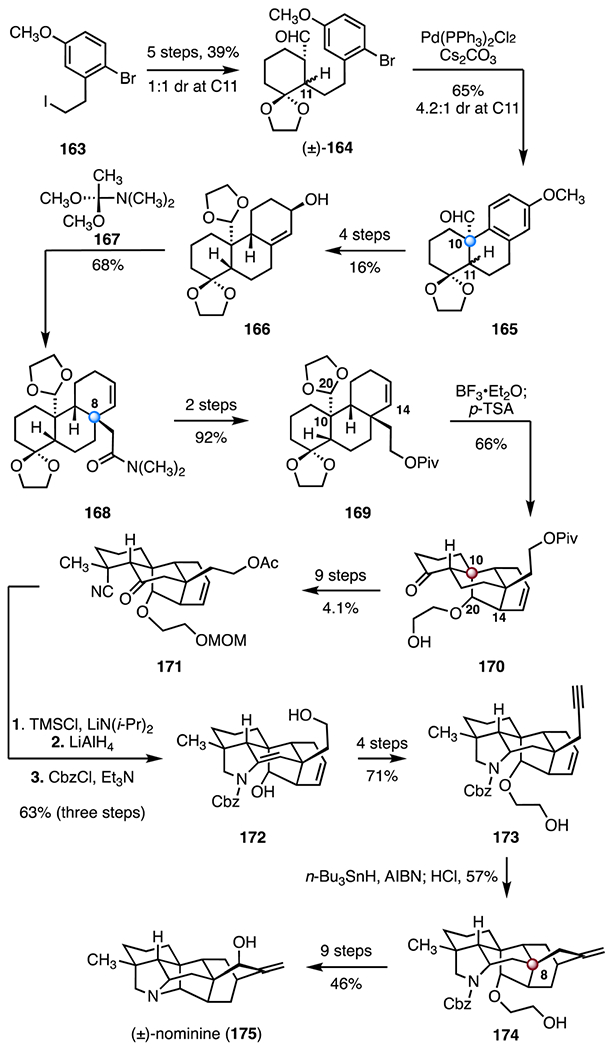

(+)-Nominine (175) was first isolated as “Nomi-base I” from Aconitum sanyoense Nakai by Ochiai and co-workers in 1956.90 It was later named “nominine” by Sakai and co-workers. Its structure was established by chemical correlation with kobusine, whose structure was elucidated by X-ray crystallography.91 In 2004, Muratake and Natsume accomplished the first synthesis of (±)-nominine (175).85,86 Their approach relied primarily on single bond-forming events to construct the complex carbon skeleton (Scheme 23). The synthesis began with a five-step sequence to convert 2-bromo-5-methoxyphenethyl iodide (163) to the aldehyde (±)-164 as a 1 : 1 diastereomeric mixture at C11 (39% overall). The aldehyde 164 was then transformed to the benzylic aldehyde 165, which contains the C10 quaternary center, by a palladium-catalyzed α-arylation (bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) chloride, cesium carbonate, 65%, 4.2 : 1 dr at C11). A four-step sequence was developed to advance the tetracyclic aldehyde 165 to the allylic alcohol 166 as a single diastereomer (16% overall). Eschenmoser–Claisen rearrangement, using acetal 167 as reagent, provided the amide 168, which contains the C8 quaternary stereogenic center (68%).92 The amide 168 was elaborated to the pivalate 169 by a two-step sequence (92% overall). An acetal–ene reaction (boron trifluoride diethyl etherate complex; then, p-toluenesulfonic acid) then formed the tetracycle 170, with the C14–C20 bond and the C10 TBCC constructed.93 A nine-step sequence afforded the tertiary cyanide 171 (4.1% overall). Nitrile reduction and protecting group manipulations generated the pyrrolidine 172 (lithium diisopropylamide, trimethylsilyl chloride; lithium aluminum hydride; triethylamine, benzyl chloroformate, 63%, three steps). The enyne 173 was obtained from the pyrrolidine 172 by a four-step sequence (71% overall). A radical cyclization (tri-n-butyltin hydride, azobisisobutyronitrile), followed by protodestannylation (hydrochloric acid), then formed the alkene 174 (57%). This reaction generated the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane scaffold of the target with the C8 TBCC in place. Ultimately, the alkene 174 was converted to (±)-nominine (175) by a nine-step sequence (46% overall). The total synthesis of (±)-nominine (175) was completed in forty steps with an overall yield of 0.0081%.

Scheme 23.

Synthesis of (±)-nominine (175) by Muratake and Natsume.85,86 p-TSA = p-toluenesulfonic acid, TMSCl = trimethylsilyl chloride, CbzCl = benzyl chloroformate, AIBN = azobisisobutyronitrile.

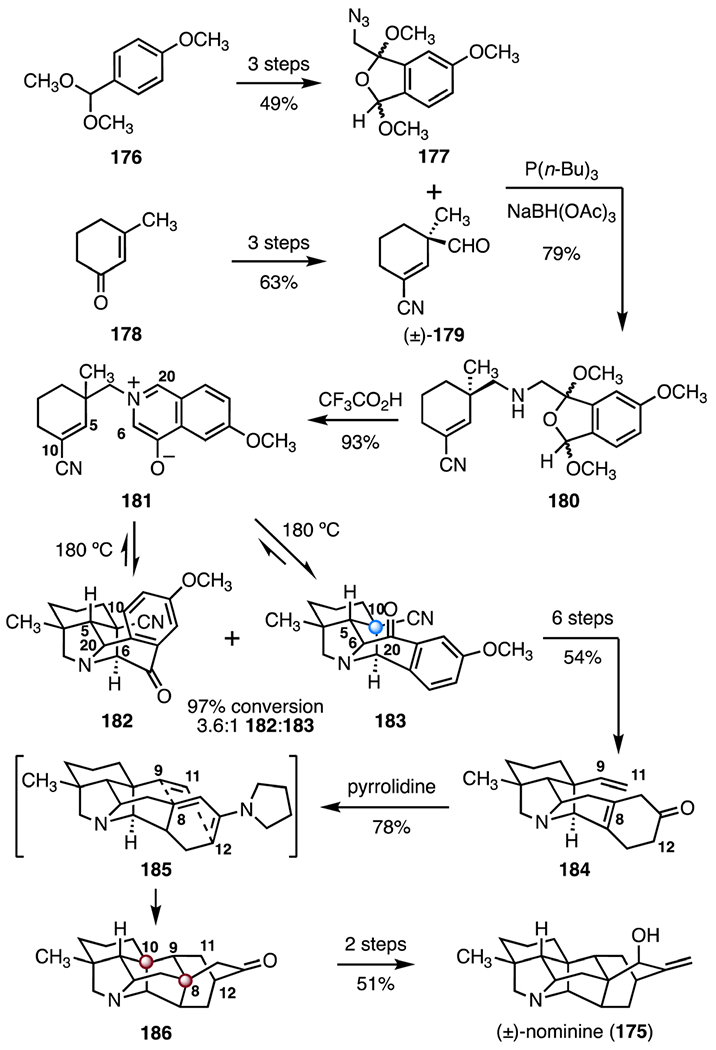

In 2006, Gin and co-workers disclosed an alternative approach to (±)-nominine (175).87 The synthesis employed an aza-1,3-dipolar cycloaddition and an intramolecular Diels–Alder (IMDA) reaction as key steps (Scheme 24). The synthesis began with the preparation of the azide 177 (three steps from the methyl ether 176, 49% overall) and the aldehyde (±)-179 (three steps from the enone 178, 63% overall). A reductive fragment coupling (tri-n-butyl phosphine, sodium triacetoxyborohydride) provided the tethered bicyclic amine 180 (79%). Acid-catalyzed (trifluoroacetic acid) elimination of methanol and isomerization furnished the 4-oxido-isoquinolinium betaine 181 (93%). Heating of 181 to 180 °C promoted an intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition, to provide a 3.6 : 1 mixture of the regioisomeric cycloaddition products 182 and 183 (97% conversion). The cycloaddition was found to be reversible, allowing for recycling of the undesired cycloadduct 182. This transformation generated the C10 quaternary center in the target. The nitrile 183 was converted to the alkene 184 by a six-step sequence (54% overall). Exposure of the alkene 184 to pyrrolidine affected an IMDA reaction, providing the cycloaddition product 186, likely through the enamine 185. The adduct 186 possesses the full carbon skeleton of the target, including the C10 and C8 TBCCs. The adduct 186 was transformed to (±)-nominine (175) in two steps (51% overall). The total synthesis was completed in fifteen steps (LLS) and 1.6% overall yield.

Scheme 24.

Synthesis of (±)-nominine (175) by Gin and co-workers.87

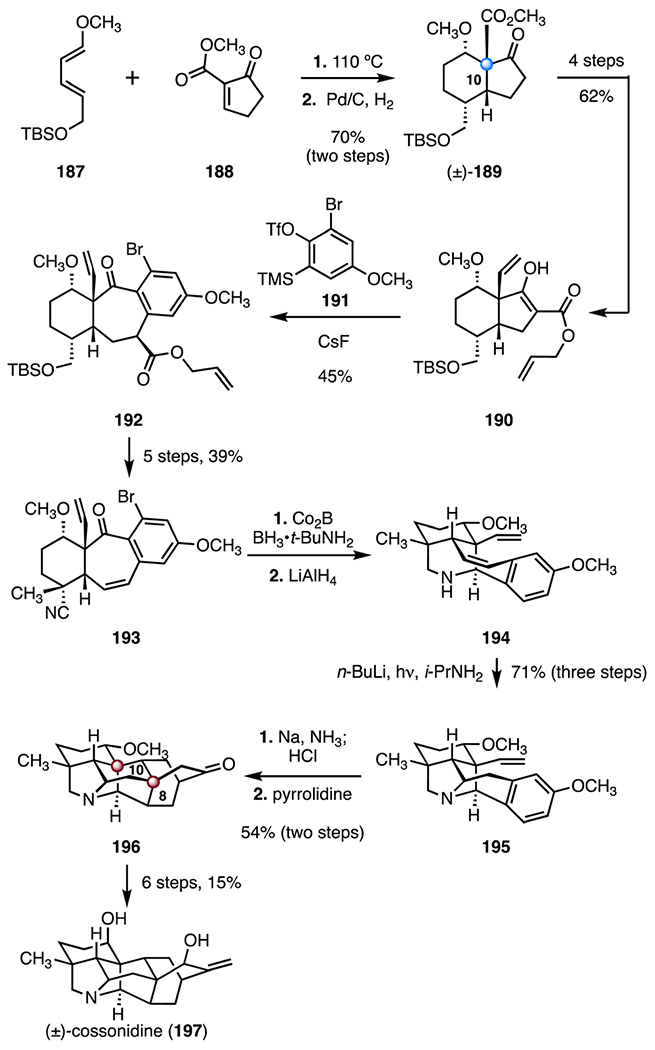

(+)-Cossonidine (197) was isolated in 1996 by Fuente and co-workers. Its structure was elucidated by NMR spectroscopy.94 In 2018, Sarpong and co-worker disclosed a synthesis of (±)-cossonidine (197) that employed a [4 + 2] cycloaddition, alkylation and acylation of a benzyne intermediate, and a double amination to facilitate disconnections of maximally bridged ring systems (Scheme 25).88 The route began with an intermolecular Diels–Alder cycloaddition between the diene 187 and the dienophile 188 (110 °C). Following catalytic hydrogenation (palladium on carbon, dihydrogen), the bicycle (±)-189 was obtained in 70% overall yield.95,96 The bicycle (±)-189 was converted to the β-ketoester 190 by a four-step sequence (62% overall). Treatment of the β-ketoester 190 with cesium fluoride in the presence of the aryl bromide 191 promoted formation of the cycloheptanone 192 through acylation and alkylation of a benzyne intermediate (45%).97 A five-step sequence was developed to convert the cycloheptanone 192 to the nitrile 193 (39% overall). Reduction of the nitrile, followed by reductive amination (cobalt boride, tert-butylamine boron complex; lithium aluminum hydride), provided the diene 194. A photochemical hydro-amination delivered the pyrrolidine 195 (n-butyl lithium, 320–1100 nm tungsten halogen lamp, isopropylamine; 71% over three steps).98 A Birch reduction (sodium, ammonia; then, hydrochloric acid), followed by a pyrrolidine-mediated IMDA, produced the cycloadduct 196, which contains the full carbon skeleton of cossonidine (197) as well as the C8 and C10 TBCCs (54%, two steps). The cycloadduct 196 was advanced to (±)-cossonidine (197) in six steps (15% overall). The synthesis was completed in twenty-three steps and 0.44% overall yield.

Scheme 25.

Synthesis of (±)-cossonidine (197) by Sarpong and co-workers.88

(+)-Spirasines IV (208) and XI (209) are hetisine alkaloids isolated from Spiraea japonica L. f. var. fortunei by Sun and Yu in 1985. Their structures were elucidated by NMR spectroscopy.99 In 2018, Zhang and co-workers reported a synthesis of (±)-208 and (±)-209 that employed an intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition to construct the carbon skeleton (Scheme 26).89 The synthesis began with the ester 198,100 which was converted to the aldehyde (±)-199 by a six-step sequence (40% overall). Treatment of the aldehyde (±)-199 with the phosphinimine 200 and silver(I) acetate promoted an intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition, through the aza-Wittig product 201, to provide the ketone 202, which bears the C10 TBCC (68%, 7 : 1 dr at C20). The tetracycle 202 was elaborated to the diol 203 by a three-step sequence (68% overall). Sulfonylation of the hydroxyl substituents in 203 (methanesulfonyl chloride, pyridine), followed by a three-step debenzylation–reductive amination–ester reduction–reductive deoxygenation sequence (palladium on active carbon, hydrogen; lithium triethylborohydride) provided the amine 204 (63%, three steps). Conversion of the primary alcohol to a halide proceeded in low yields (product not shown), resulting in exploration of alternative radical precursors. Ultimately, the thiocarbonate 205 was accessed from 204 (phenyl chlorothionocarbonate, 4-dimethylaminopyridine, 87%). Treatment of the thiocarbonate 205 with samarium(II) iodide promoted a reductive cyclization, to provide the diene 206 (61%). The C8 TBCC was installed in this step. The diene 206 was advanced to the alcohol 207 in three steps (37% overall). Finally, a three-step sequence was developed to convert the alcohol 207 to (±)-spirasine IV (208, 43% overall). Stereo-controlled reduction of 208 (L-selectride) provided (±)-spirasine XI (209; 83%, >20 : 1 dr). Overall, the synthesis of (±)-spirasine IV (208) was completed in twenty-two steps and 0.98% overall yield and the synthesis of (±)-spirasine XI (209) was completed in twenty-three steps and 0.82% overall yield.

Scheme 26.

Synthesis of (±)-spirasine IV (208) and (±)-spirasine XI (209) by Zhang and co-workers.89 MsCl = methanesulfonyl chloride, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine.

The syntheses outlined above highlight the evolution of strategies from iterative individual bond constructions to concerted cycloaddition reactions in which the C8 and C10 TBCCs are constructed in a single step. In Natsume’s synthesis,85,86 the C10 quaternary center was formed early in the route by an α-arylation reaction (164 → 165). The C8 quaternary center was later introduced by an Eschenmoser–Claisen rearrangement (166 → 168). Single bond cyclization events about the two quaternary centers were then used to construct the full carbon skeleton. Gin’s synthesis87 constructed the C10 quaternary center by an aza-1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (181 → 183), while Sarpong and co-workers88 established this center by a [4 + 2] cycloaddition (187 + 188 → 189). Both Gin87 and Sarpong88 employed a base-mediated [4 + 2] cycloaddition (184 → 186, 195 → 196) to construct the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane core bearing the C8 TBCC. The stereochemical outcome of this reaction was relayed from the pre-established C10 quaternary center. Zhang’s synthesis89 employed a unique intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of an azamethine ylide to direct construct the C10 TBCC (199 → 202). The C8 TBCC was accessed by a reductive cyclization (205 → 206).

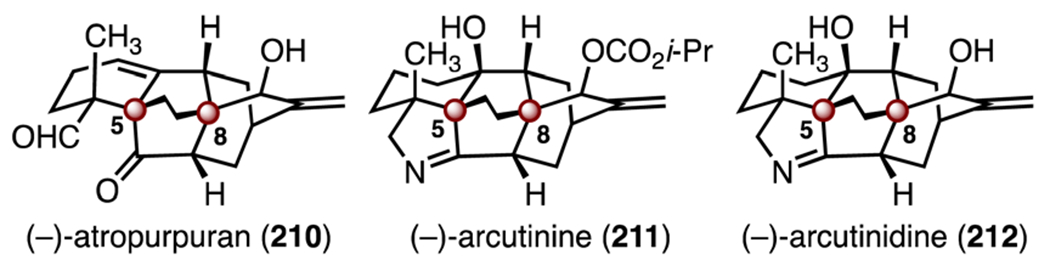

2.6. Arcutine alkaloids and atropurpuran: dispersed TBCCs within a rearranged hetisine core

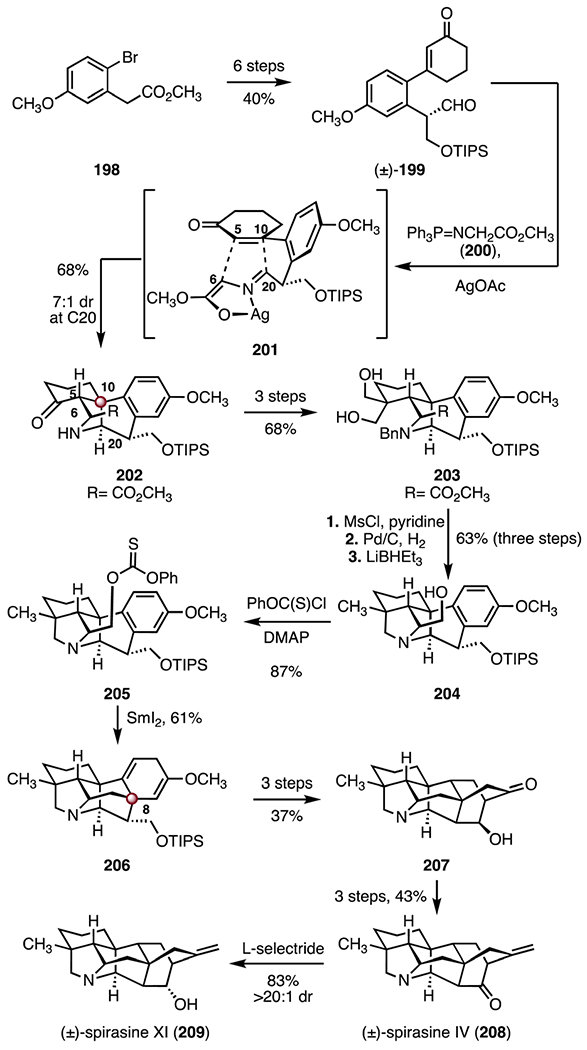

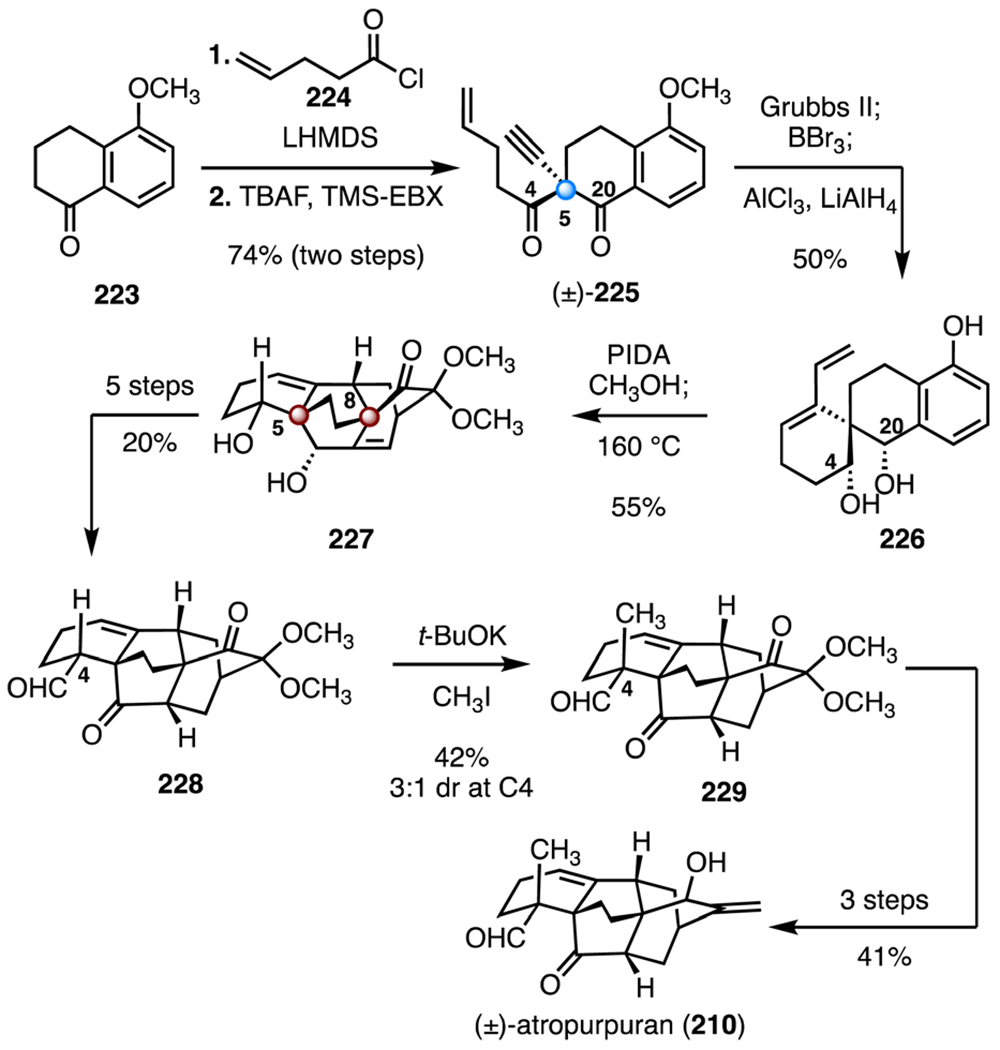

The arcutine diterpenoids are characterized by a complex tetracyclo[5.3.3.04,9.04,12]tridecane framework that possesses TBCCs at C5 and C8 (Scheme 27). (−)-Atropurpuran (210) was isolated by Wang and co-workers from Aconitum hemslyanum var. atropurpureum in 2009, and its structure was elucidated by X-ray crystallography.101 (−)-Arcutinine (211) was first isolated by Saidkhodzhaeva and co-workers from Aconitum arcuatum in 2000. (−)-Arcutinidine (212) is the product of saponification of (−)-arcutinine (211). Their structures were elucidated by X-ray crystallography.102 Biosynthetically, the arcutine terpenoid alkaloids are proposed to arise from rearrangements of hetidine or hetisine alkaloids.103 The first total synthesis of atropurpuran (210) was reported in 2016 by Qin and co-workers,104 and a second synthesis was reported by Xu and co-workers in 2019.105 Total syntheses of arcutinine (211) and arcutinidine (212) have been reported by the Qin, Sarpong, and Li groups.106–108

Scheme 27.

Structure of (−)-atropurpuran (210), (−)-arcutinine (211) and (−)-arcutinidine (212).

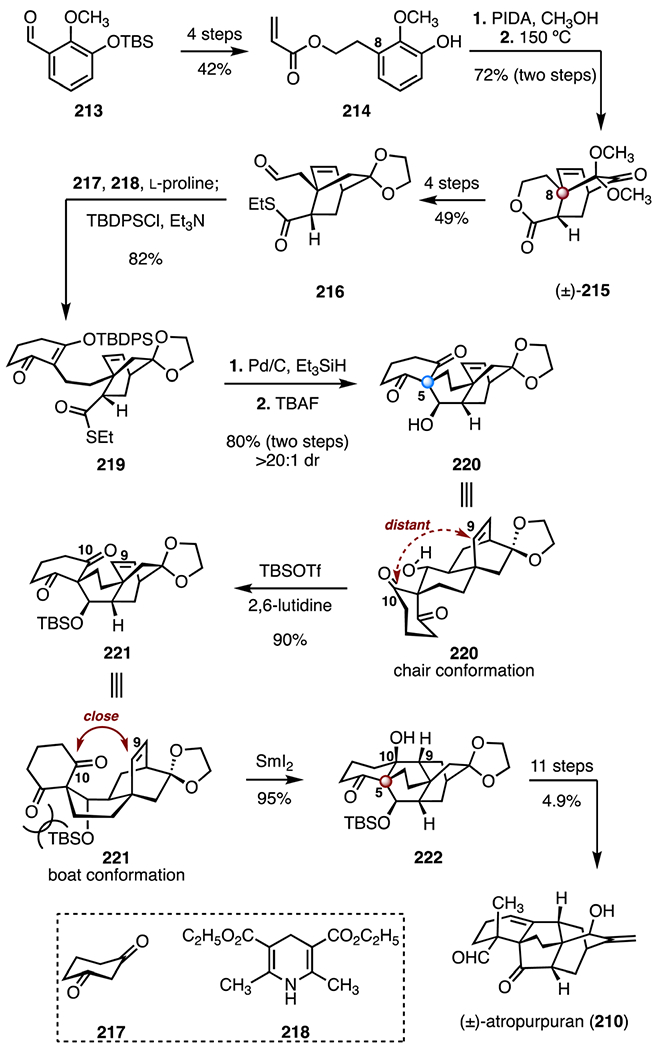

In 2016, Qin and co-workers disclosed the synthesis of (±)-atropurpuran (210, Scheme 28).104 Their approach to the complex tetracyclic [5.3.3.04,9.04,12]tridecane system relied on a late-stage ketyl–olefin cyclization and an aldol addition. The synthesis began with the aryl aldehyde 213,109 which was transformed to the acrylate 214 in four steps (42% overall). Oxidative dearomatization of 214 (di(acetoxyiodo)benzene, methanol) followed by a thermal IMDA (150 °C) provided the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane derivative (±)-215, which contains the C8 TBCC (72%, two steps). The cyclization product (±)-215 was converted to the thioester 216 by a four-step sequence (49% overall). A reductive Knoevenagel condensation between the thioester 216 and 217 (218, l-proline; then tert-butyl(chloro) diphenylsilane, triethylamine) generated the β-silyloxy enone 219 (82%).110 Reduction of the thioester (palladium on active carbon, triethylsilane), followed by a stereoselective Mukaiyama aldol addition (tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride) generated the alcohol 220, which contains the C5 quaternary stereogenic center (80%, >20 : 1 dr, two steps). A silyl ether was introduced (tert-butyldimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate, 2,6-lutidine, 90%) to bias the conformation of 221 towards a boat-like conformation. This conformation brings the C10 carbonyl and the C9 alkene in closer proximity than the corresponding chair conformer. Treatment of the silyl ether 221 with samarium(II) iodide promoted a ketyl–olefin cyclization to provide the tertiary alcohol 222, which contains the C5 TBCC (95%). The remaining functionality was then introduced by an eleven-step sequence (4.9% overall). The total synthesis of (±)-atropurpuran (210) was completed in twenty-six steps and 0.41% overall yield.

Scheme 28.

Synthesis of (±)-atropurpuran (210) by Qin and co-workers.104 PIDA = di(acetoxyiodo)benzene, TBDPSCl = tert-butyl(chloro)diphenylsilane, TBSOTf = tert-butyldimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate.

In 2019, Xu and co-workers completed the synthesis of (±)-atropurpuran (210) using a strategy that relied on generating both contiguous bicyclo[2.2.2]octane systems by a dearomatization–IMDA sequence (Scheme 29).105 Their route began with the tetralone 223. Treatment of 223 with lithium bis(trimethylsilyl) amide and the pent-4-enoyl chloride (224) followed by addition of tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride and trimethylsilyl ethynylbenziodoxolone (TMS-EBX) provided the alkynyl diketone (±)-225, which bears the C5 quaternary center (74%, two steps). Ring-closing enyne metathesis (Grubbs II catalyst), followed by cleavage of the methyl ether (boron tribromide) and diastereoselective reduction of the C4 and the C20 ketones (trimethylaluminum, lithium aluminum hydride), generated the spirocyclic diol 226 (50%). Oxidative dearomatization of the diol 226 (di(acetoxyiodo)benzene, methanol) followed by IMDA (160 °C) formed the tetracyclo[5.3.3.04,9.04,12] tridecane 227 (55%). Both the C5 and C8 TBCCs were established in this step. A five-step sequence then provided the aldehyde 228 (20% overall). The final C4 quaternary stereocenter was introduced by methylation (potassium tert-butoxide, iodomethane, 42%, 3 : 1 dr). The methylated product 229 was elaborated to (±)-atropurpuran (210) by a three-step sequence (41% overall). The total synthesis of (±)-atropurpuran (210) was completed in thirteen steps and 0.70% overall yield.

Scheme 29.

Synthesis of (±)-atropurpuran (210) by Xu and co-workers.105 LHMDS = lithium bis(trimethylsilyl) amide, TBAF = tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride, TMS-EBX = trimethylsilyl ethynylbenziodoxolone, PIDA = di(acetoxyiodo)benzene.

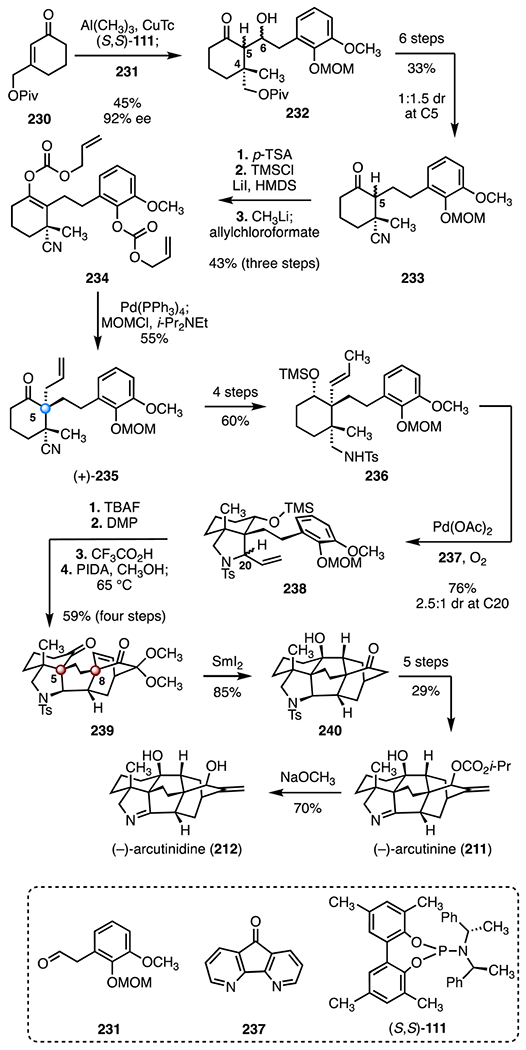

In 2019, Qin and co-workers reported a synthesis of (−)-arcutinine (211) and (−)-arcutinidine (212).106 Their synthetic strategy relied on an aza-Wacker reaction followed by IMDA and reductive cyclization to form the carbon skeleton (Scheme 30). Their synthesis began with an enantioselective 1,4-addition67 of trimethylaluminum to the enone 230 (copper(I) thiophene-2-carboxylate (S,S)-111), followed by an aldol addition to the aldehyde 231 in situ (45%, 92% ee).111 The resulting mixture of inseparable C5 and C6 diastereomers of the ketone 232 was transformed to the tertiary nitrile 233 by a six-step sequence (33% overall, 1 : 1.5 dr at C5). Cleavage of the methoxymethyl ether (p-toluenesulfonic acid), followed by two-fold enoxysilane formation (trimethylsilyl chloride, lithium iodide, bis(trimethylsilyl) amine) and O-allylic alkylation (methyl lithium; then, allyl chloroformate), formed the bis(allyl carbonate) 234 (43%, three steps). A palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation of 234 (tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) palladium(0)) and reintroduction of the aryl methoxymethyl ether protecting group (methoxymethyl chloride, N,N-diisopropylethylamine) provided the α-allyl ketone (+)-235 (55%).112 The ketone (+)-235 was transformed to the silyl ether 236 by a four-step sequence (60% overall). An aza-Wacker reaction (palladium(II) acetate, 237, dioxygen) generated the pyrrolidine 238 (76%, 2.5 : 1 dr at C20).113 Removal of the silyl ether (tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride), oxidation (Dess–Martin periodinane), and methoxymethyl ether cleavage (trifluoroacetic acid) furnished the expected phenol (not shown). Oxidative dearomatization (di(acetoxyiodo)benzene, methanol) followed by an IMDA (65 °C) furnished the cycloadduct 239 (59%, four steps), which bears the C5 and C8 TBCCs. The synthesis of the carbon framework was completed by a samarium(II) iodide-mediated ketyl–olefin cyclization, to generate the tertiary alcohol 240 (85%). The alcohol 240 was transformed to (−)-arcutinine (211) in five steps (29% overall), which after saponification (sodium methoxide, 70%), provided (−)-arcutinindine (212). The synthesis of (−)-arcutinine (211) was completed in twenty-six steps and 0.23% overall yield. The synthesis of (−)-arcutinindine (212) was completed in twenty-seven steps and 0.16% yield.

Scheme 30.

Synthesis of (−)-arcutinine (211) and (−)-arcutinidine (212) by Qin and co-workers.106 CuTc = copper(I) thiophene-2-carboxylate, p-TsOH = p-toluenesulfonic acid, TMSCl = trimethylsilyl chloride, HMDS = bis(trimethylsilyl) amine, MOMCl = methoxymethyl chloride, TBAF = tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride, DMP = Dess–Martin periodinane, PIDA = di(acetoxyiodo)benzene.

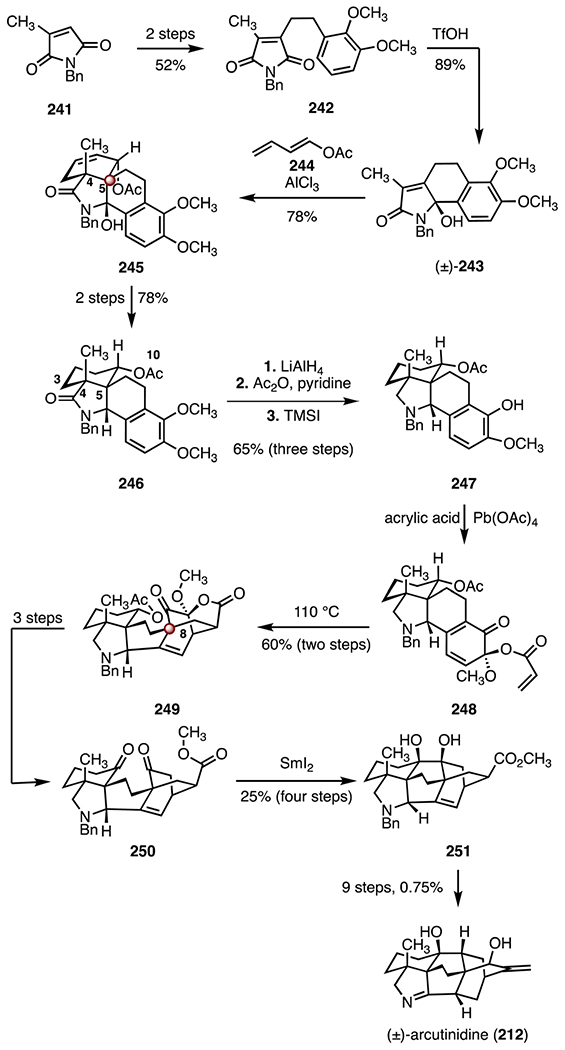

In 2019, Sarpong and co-workers disclosed a synthesis of (±)-arcutinidine (212).107 Their synthetic strategy employed two [4 + 2] cycloadditions to construct the carbon skeleton (Scheme 31). The route began with conversion of citracomimide (241)114,115 to the tethered bicyclic ether 242 (52%, two steps), which was then advanced to the tricyclic hemiaminal (±)-243 by a Friedel–Crafts cyclization (trifluoromethanesulfonic acid, 89%). Treatment of (±)-243 with the diene 244 in the presence of aluminum chloride furnished the tetracycle 245, through generation of an oxopyrrolium dienophile (78%). This first [4 + 2] cycloaddition constructed the vicinal C4 quaternary center and C5 TBCC in a single transformation. A two-step sequence was developed to elaborate 245 to the amide 246 (78% overall). The amide 246 was transformed to the phenol 247 by reduction (lithium aluminum hydride), acylation (acetic anhydride, pyridine) and demethylation (trimethylsilyl iodide, 65%, three steps). Exposure of the phenol 247 to lead(IV) acrylate (generated in situ from acrylic acid and lead(iv) acetate) provided the α-keto vinyl acrylate intermediate 248, which then underwent a second [4 + 2] cycloaddition upon heating to 110 °C, to form the cycloadduct 249 bearing the C8 TBCC (60%, two steps). The adduct 249 was transformed to the diketone 250 in three steps. A pinacol coupling (samarium(II) iodide) furnished the vicinal diol 251 (25%, four steps), which was converted to (±)-arcutinidine (212) in nine steps (0.75% overall). The synthesis of (±)-arcutinidine (212) was completed in twenty-four steps and 0.021% overall yield.

Scheme 31.

Synthesis of (±)-arcutinidine (212) by Sarpong and co-workers.107 TfOH = trifluoromethanesulfonic acid.

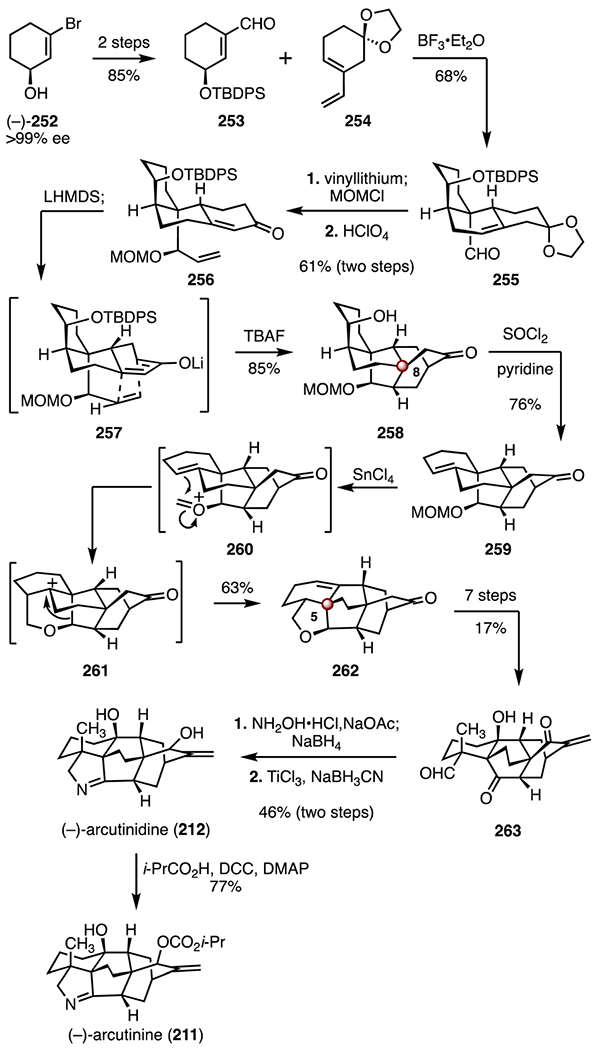

In 2019, Li and co-workers disclosed a synthesis of (−)-arcutinine (211) and (−)-arcutinidine (212).108 Li’s strategy employed two [4 + 2] cycloadditions, a biomimetic cationic rearrangement, and a late-stage reductive amination (Scheme 32). The synthesis began with the enantioenriched alcohol (−)-252 (>99% ee),116 which was converted to the enal 253 by a two-step sequence (85% overall). Lewis acid-catalyzed [4 + 2] cycloaddition (boron trifluoride diethyl etherate complex) between the enal 253 and the diene 254 then provided the tricyclic alkene 255 (68%). Stereoselective 1,2-addition (vinyllithum), protection of the resulting alcohol (methoxymethyl chloride) and ketal removal (perchloric acid) with concomitant alkene isomerization furnished the enone 256 (61%, two steps). An anionic [4 + 2] cycloaddition was achieved by treatment of the enone 256 with lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (through 257); cleavage of the silyl ether (tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride) in situ then delivered the ketone 258 (85%).117 The alkene 259 was accessed by formal dehydration of 258 (thionyl chloride, pyridine, 76%). Exposure of the alkene 259 to tin(IV) chloride furnished the cyclic ether 262 (63%). This transformation was hypothesized to proceed by ionization of the methoxymethyl ether (259 → 260), Prins cyclization (260 → 261), 1,2-alkyl shift, and proton elimination (261 → 262). The ketone 262 was elaborated to the aldehyde 263 by a seven-step sequence (17% overall). Oxime formation and enone reduction (hydroxylamine hydrochloride, sodium acetate; then, sodium borohydride), followed by selective reduction (titanium(III) chloride, sodium cyanoborohydride) and imine formation furnished (−)-arcutinidine (212; 46%, two steps).118 Acylation of 212 (4-(dimethylamino)pyridine, isobutyric acid, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide, 77%) provided (−)-arcutinine (211). The syntheses of (−)-arcutinidine (212) and (−)-arcutinine (211) were achieved in seventeen steps and 1.1% overall yield, and eighteen steps and 0.86% overall yield, respectively.

Scheme 32.

Synthesis of (−)-arcutinidine (212) and (−)-arcutinine (211) by Li and co-workers.108 MOMCl = methoxymethyl chloride, LHMDS = lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, TBAF = tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride, DCC = N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine.

The syntheses discussed all employed two-bond disconnections by [4 + 2] cycloaddition reactions. Qin and co-workers104 employed an oxidative–dearomatization IMDA early in the route to form the C8 quaternary carbon (214 → 215) in their synthesis of (±)-atropurpuran (211). This in turn allowed them to construct the C5 TBCC by an aldol addition (219 → 220) and a ketyl–olefin cyclization (221 → 222). The Xu group105 also utilized a dearomative [4 + 2] cycloaddition to establish the tetracyclo[5.3.3.04,9.04,12]tridecane system (226 → 227). The C5 center was accessed by asymmetric alkylation (223 → 225) and enyne metathesis (225 → 226). The Qin group106 formed the C5 quaternary center of the arcutine-type alkaloids by a decarboxylative allylic alkylation (234 → 235), followed by a dearomatization–IMDA sequence to install the C8 TBCC (238 → 239). The Sarpong synthesis107 employed a late-stage IMDA reaction to form the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane (248 → 249) and the C8 TBCC, while constructing the vicinal C4 and C5 quaternary centers by a second [4 + 2] cycloaddition involving a novel oxopyrrolium dienophile (243 + 244 → 245). The Li group108 took advantage of a biomimetic cationic rearrangement to construct the C5 TBCC (259 → 262). An anionic [4 + 2] cycloaddition enabled the C8 TBCC formation (256 → 258). The conformational rigidity of caged polycyclic structures results in reactivity driven by well-defined conformations. The reductive cyclization (221 → 222) in Qin’s synthesis of (±)-atropurpuran (210)104 illustrated the strategic use of protecting groups to manipulate the conformation of a molecule and to enable desired reactivity.

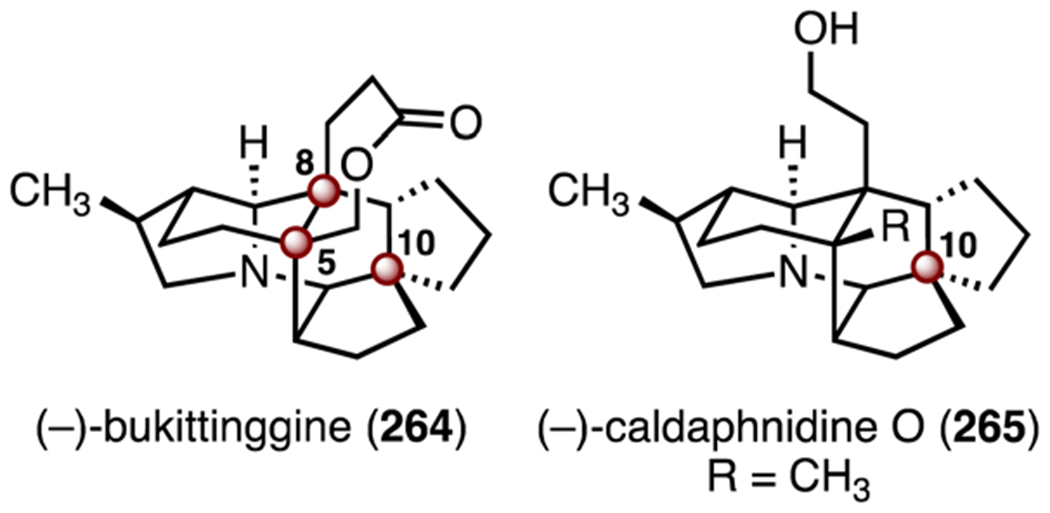

2.7. Bukittinggine alkaloids: congested cluster of TBCCs within a terpenoid alkaloid scaffold

The daphniphyllum alkaloids have attracted much attention due to their complex structures.119,120 One of the most synthetically challenging members of this family are the bukittinggine alkaloids, which contain a heptacyclic ring system bearing TBCCs at C5, C8 and C10 (Scheme 33). Related daphniphyllum alkaloids have been the subject of many synthetic studies.121,122 By comparison, only two total syntheses of bukittinggine-type alkaloids have been disclosed. (±)-Bukittinggine (264) was synthesized by Heathcock and co-workers in 1992.123 (−)-Caldaphnidine O (265) was synthesized by Xu and co-workers in 2019.124 (−)-Bukittinggine (264) was isolated in 1990 from Sapium baccatum by Cannon and co-workers. Its structure was determined through X-ray analysis of its hydrobromide salt.125 (−)-Bukittinggine (264) possesses anti-inflammatory activities.126 (−)-Caldaphnidine O (265) was isolated from the twigs of Daphniphyllum calycinum by Yue and co-workers in 2008. Its structure was determined by NMR spectroscopy.127

Scheme 33.

Structures of (−)-bukittinggine (264) and (−)-caldaphnidine O (265).

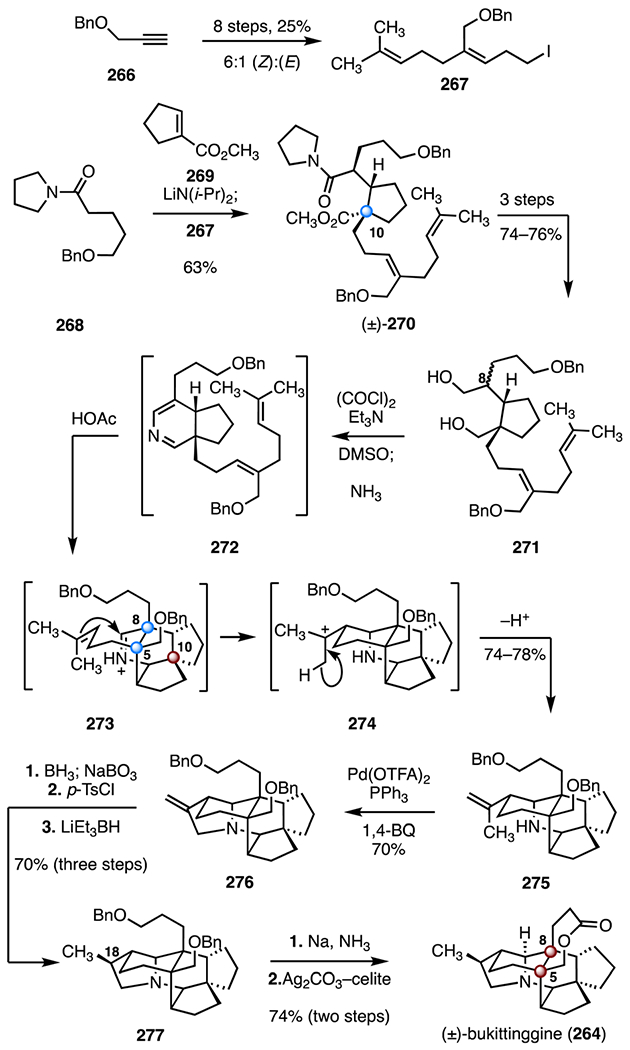

Heathcock and co-workers employed a [4 + 2] cycloaddition–aza-Prins cascade to form the tetracyclic core of bukittinggine (264; Scheme 34).123 The diene 267 was prepared from the alkynyl benzyl ether 266 in eight steps and as a 6 : 1 mixture of (Z)- and (E)-diastereomers (25% overall). The methyl ester (±)-270, which contains the C10 quaternary center, was prepared in a convergent fashion by a one-flask Michael addition–alkylation between the diene 267, the amide 268, and the ester 269 (lithium diisopropylamide, 63%). A three-step sequence then provided the diol 271, as an inconsequential C8 diastereomeric mixture (74–76% overall). Swern oxidation of the diol (oxalyl chloride, triethylamine, dimethylsulfoxide) followed by sequential addition of ammonia and acetic acid, provided the polycyclic amine 275 (74–78%). This transformation was thought to proceed by an intramolecular inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction, initiated by protonation of the 2-aza diene intermediate 272 (272 → 273), an aza-Prins cyclization (273 → 274) and an elimination (274 → 275). Three rings, the C5 and C8 quaternary stereogenic centers, and the C10 TBCC were generated in this transformation. Palladium-mediated cyclization of the amine 275 (palladium(II) trifluoroacetate, triphenylphosphine, 1,4-benzoquinone, 70%) delivered the pyrrolidine 276.128

Scheme 34.

Synthesis of (±)-bukittinggine (264) by Heathcock and co-workers.123 DMSO = dimethylsulfoxide, p-TsCl = p-toluenesulfonic chloride, 1,4-BQ = 1,4-benzoquinone, TFA = trifluoroacetate.

Hydroboration–oxidation of the pyrrolidine 276 (borane, sodium perborate), sulfonylation of the resulting alcohol (p-toluenesulfonic chloride), and reduction (lithium triethylborohydride) furnished the amine 277 (70%, three steps). A debenzylation–oxidation sequence (sodium, ammonia; silver(I) carbonate on Celite, 74%, two steps) was developed to obtain (±)-bukittinggine (264). (±)-Bukittinggine (264) was synthesized in nineteen steps and 3.1–3.4% overall yield.

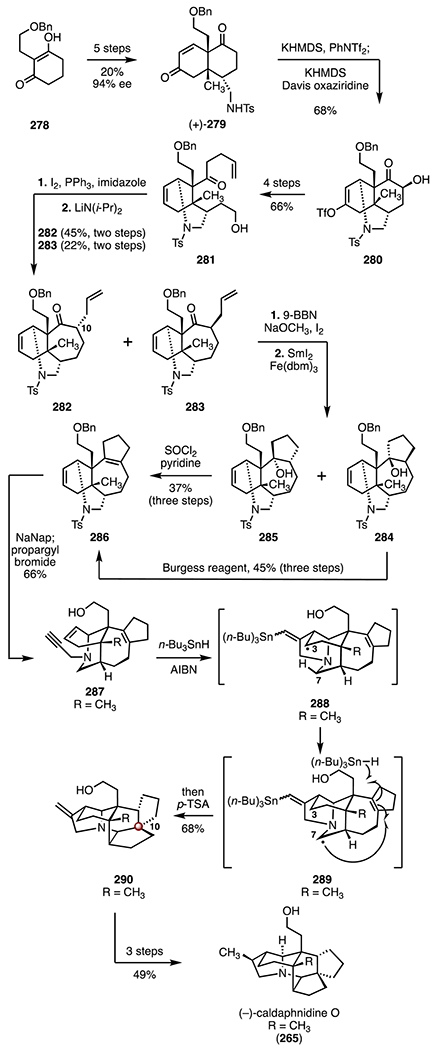

Xu and co-workers developed a late-stage radical cyclization cascade to form the C10 TBCC in (−)-caldaphnidine O (265; Scheme 35).124 The synthesis began with the benzyl ether 278,129 which was advanced in five steps to the enantio-enriched bicyclic enone (+)-279 (20% overall, 94% ee).130 Intramolecular aza-Michael addition (IMAM) and trifluoromethanesulfonylation of the resulting enolate (potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)aniline), followed by α-hydroxylation of the ketone (potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, Davis oxaziridine), provided the hydroxy ketone 280 as a single diastereomer (68%). A four-step sequence was developed to convert the α-hydroxy ketone 280 to the homoallylic ketone 281 (66% overall). Deoxyiodination (iodine, triphenylphosphine, imidazole), followed by an intramolecular alkylation (lithium diisopropylamide) furnished a mixture of the diastereomeric cycloheptanones 282 (45%, two steps) and 283 (22%, two steps). Hydroboration–iodination (9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane; then, sodium methoxide, iodine) followed by reductive coupling (samarium(II) iodide, iron tris(diisobutyrylmethane)) provided the tricyclic alcohols 284 and 285.131–133 Dehydration of either diastereomer (thionyl chloride, pyridine for 285, 37%, three steps; Burgess reagent for 284, 45%, three steps) then formed the cyclopentene 286. Reductive removal of the sulfonamide and benzyl ether protecting groups (sodium naphthalenide), followed by in situ N-propargylation (propargyl bromide), furnished the enyne 287 (66%). Exposure of the enyne 287 to azobisisobutyronitrile and tri-n-butyltin hydride, followed by addition of p-toluenesulfonic acid, yielded the alkene 290, which bears the C10 TBCC (68%). This reaction was proposed to proceed through sequential 5-exo-trig cyclization (287 → 288), 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (288 → 289), transannular 5-exo-trig cyclization, reduction of the C9 radical, and destannylation (289 → 290). A three-step sequence then provided (−)-caldaphnidine O (265, 49% overall). The synthesis of (−)-caldaphnidine O (265) was completed in twenty-one steps and 0.48% overall yield.

Scheme 35.

Synthesis of (−)-caldaphnidine O (265) by Xu and co-workers.124 KHMDS = potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, PhNTf2 = bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)aniline, 9-BBN = 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane, Fe(dbm)3 = iron tris(diisobutyrylmethane), NaNap = sodium naphthalenide, AIBN = azobisisobutyronitrile, p-TSA = p-toluenesulfonic acid.

The syntheses discussed above illustrate two distinct approaches to these alkaloid targets. Heathcock and co-workers123 employed a Michael addition–alkylation early in the synthesis to construct the C10 quaternary center (268 → 270). A carefully orchestrated inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder (IEDDA)/aza-Prins cyclization cascade furnished the C5 and C8 quaternary stereogenic centers and the C10 TBCC in a single step (271 → 275). The Xu group124 employed a distinct, late-stage transannular skeletal cyclization cascade (287 → 290) to access the carbon skeleton and the C10 TBCC.

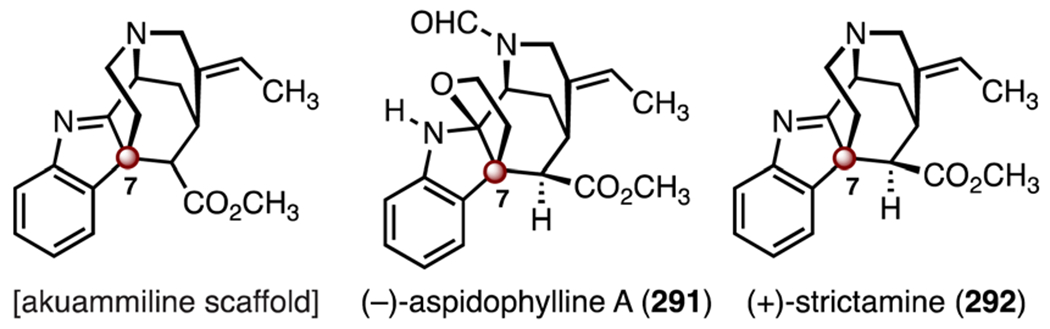

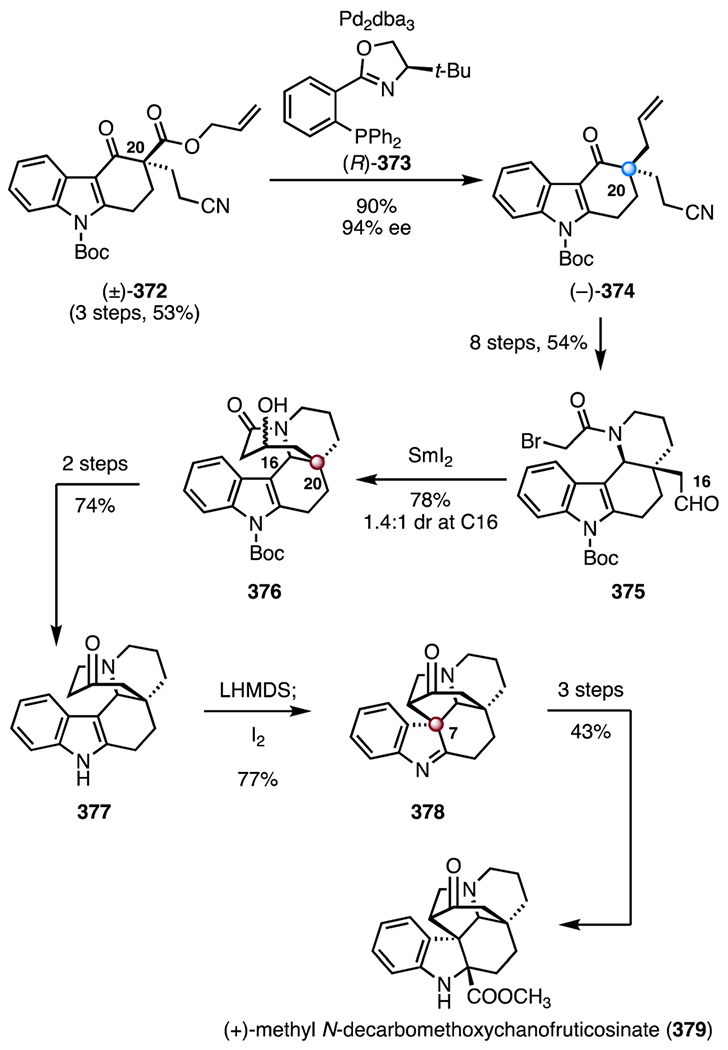

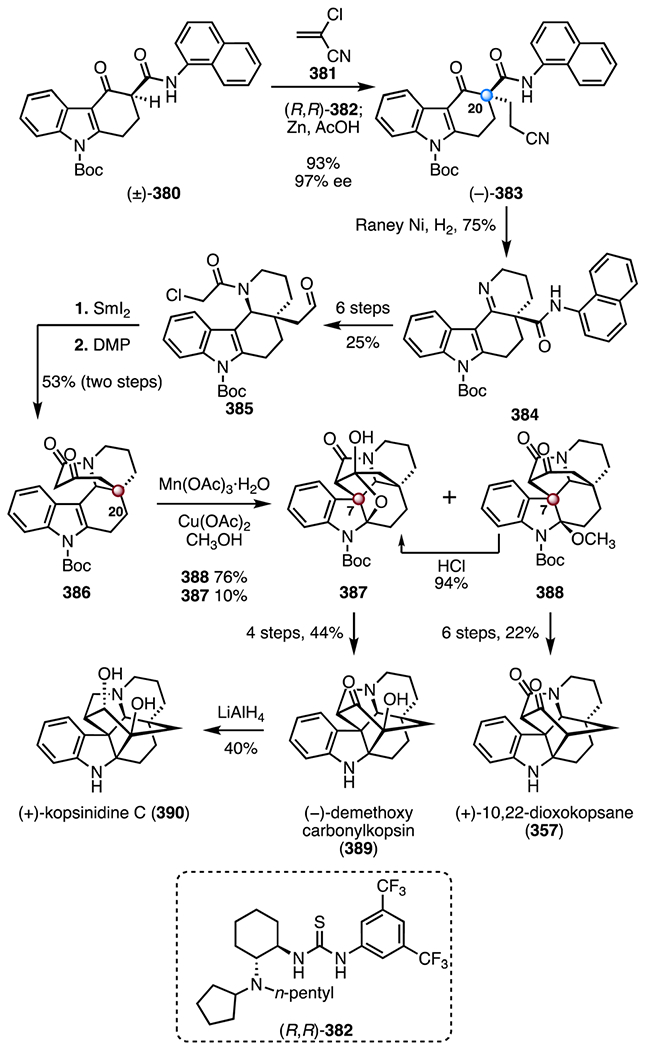

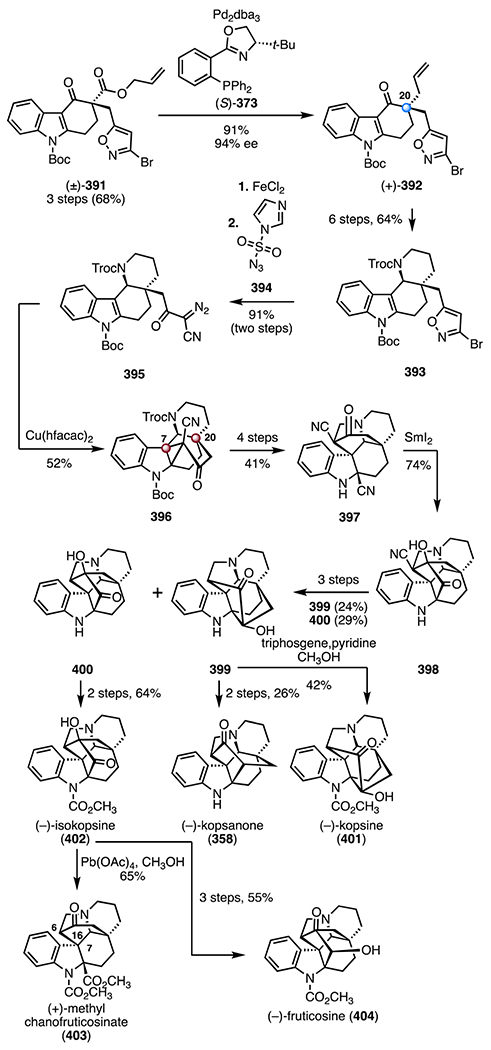

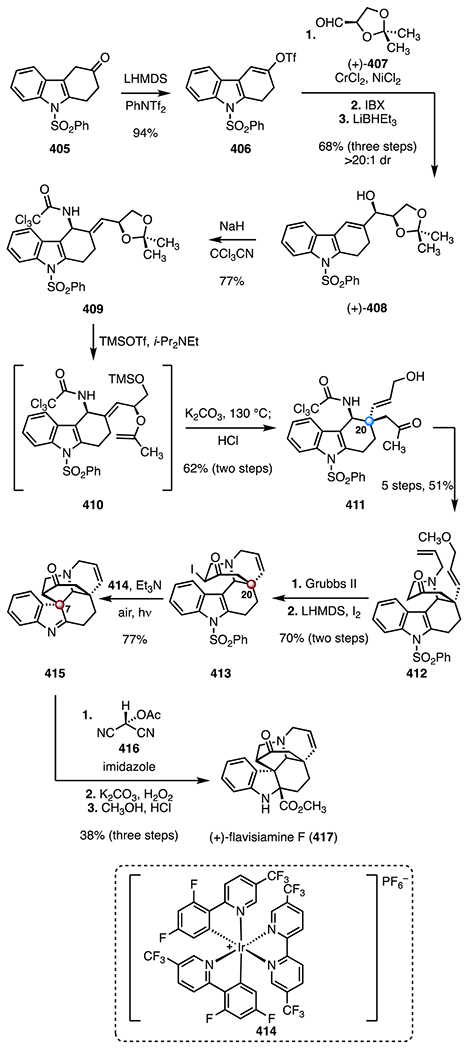

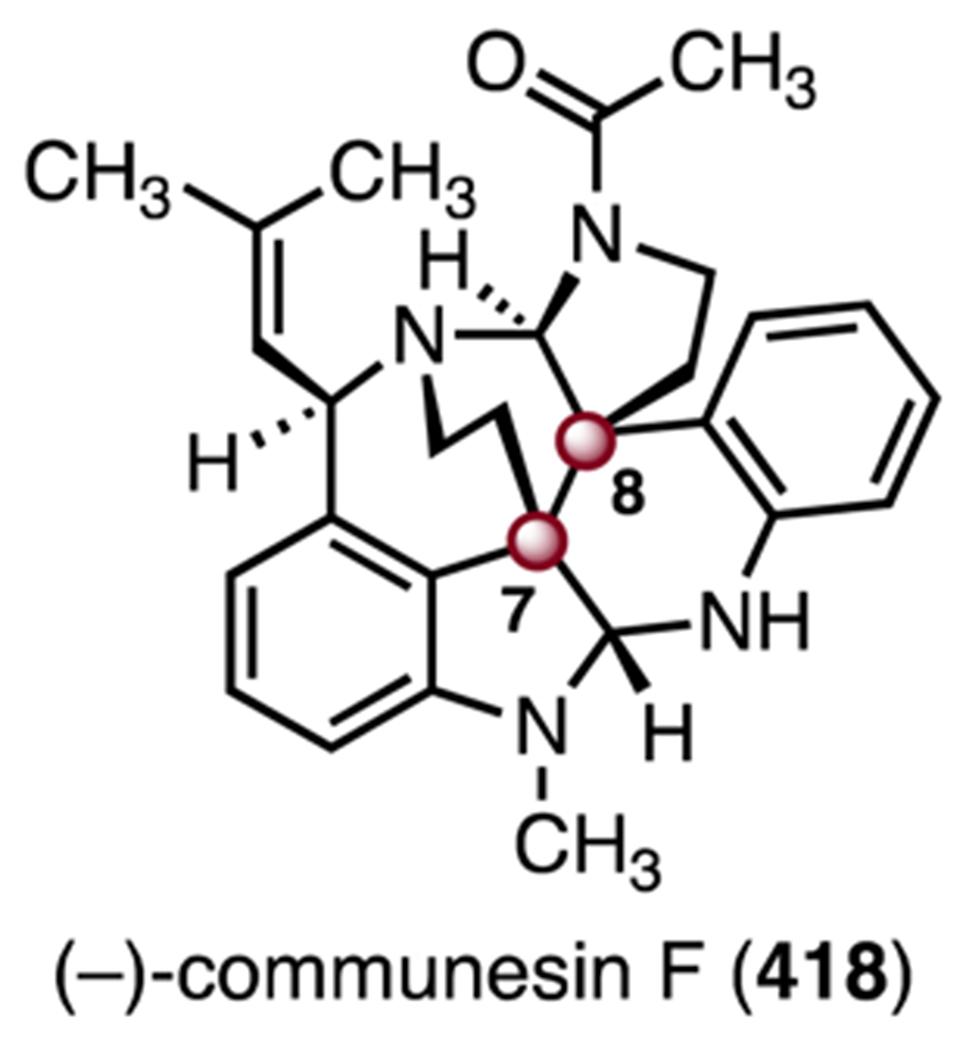

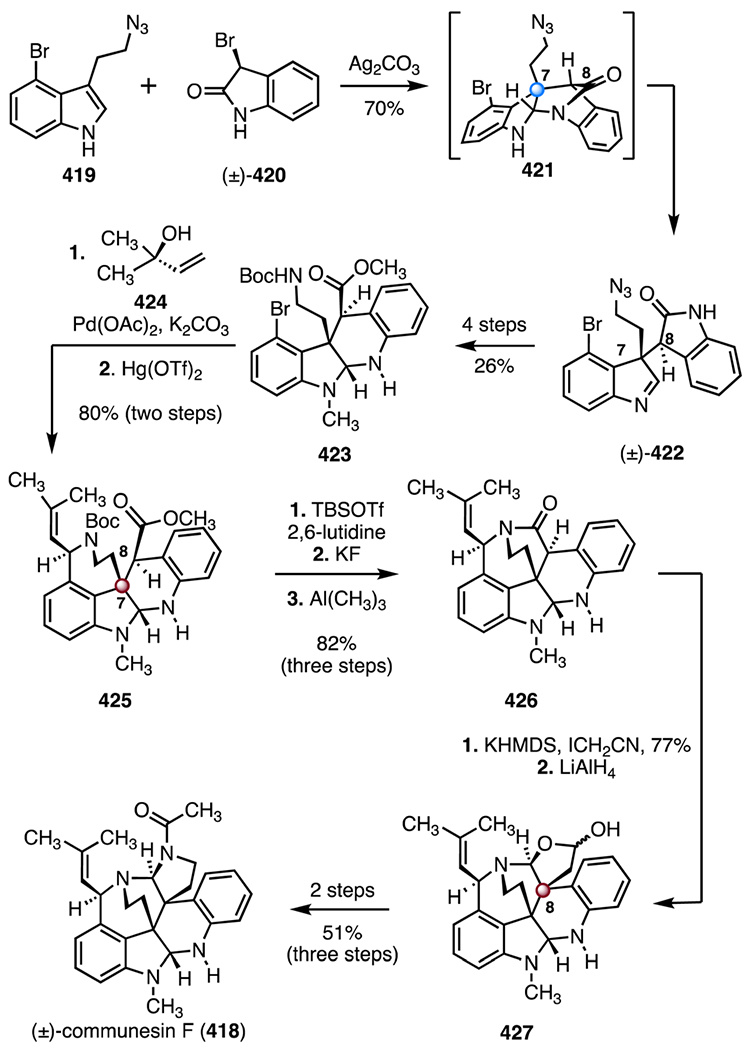

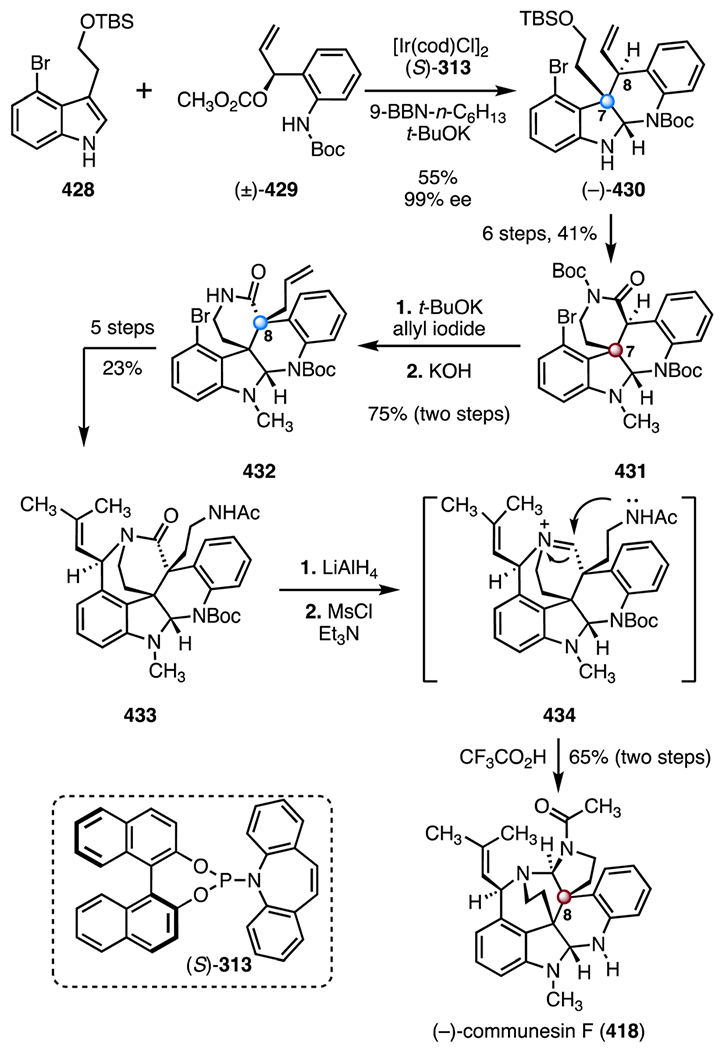

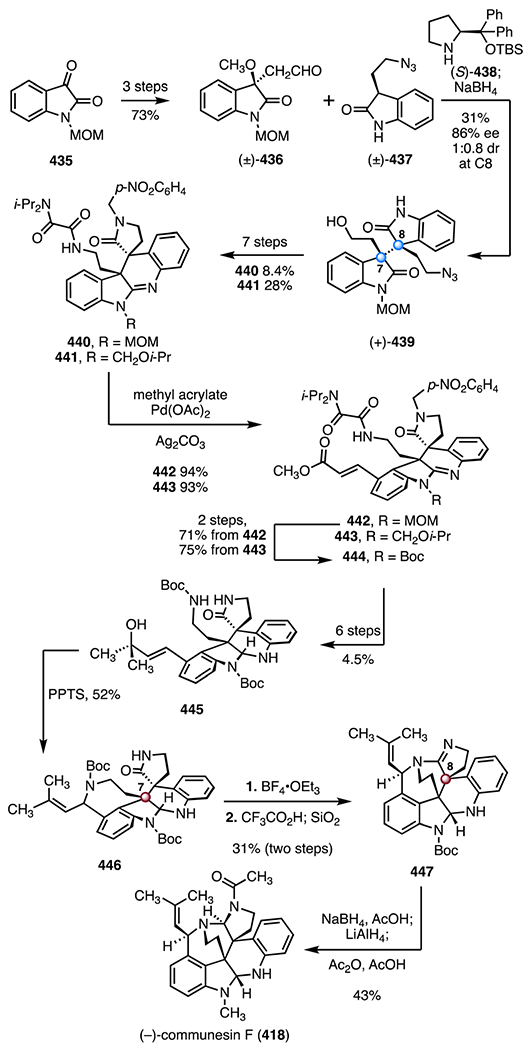

2.8. Akuammiline alkaloids: an indole-containing isolate bearing a TBCC at the 3-position of the indole

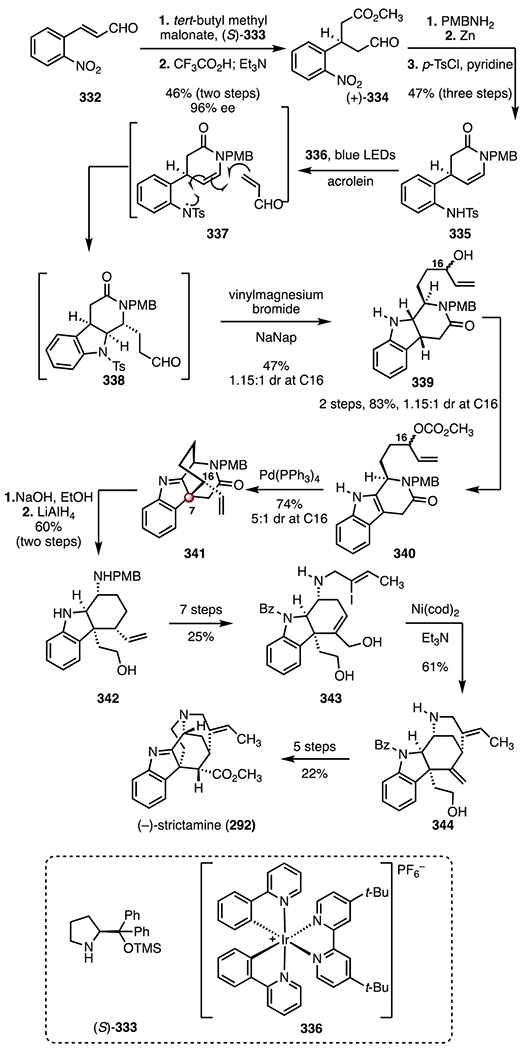

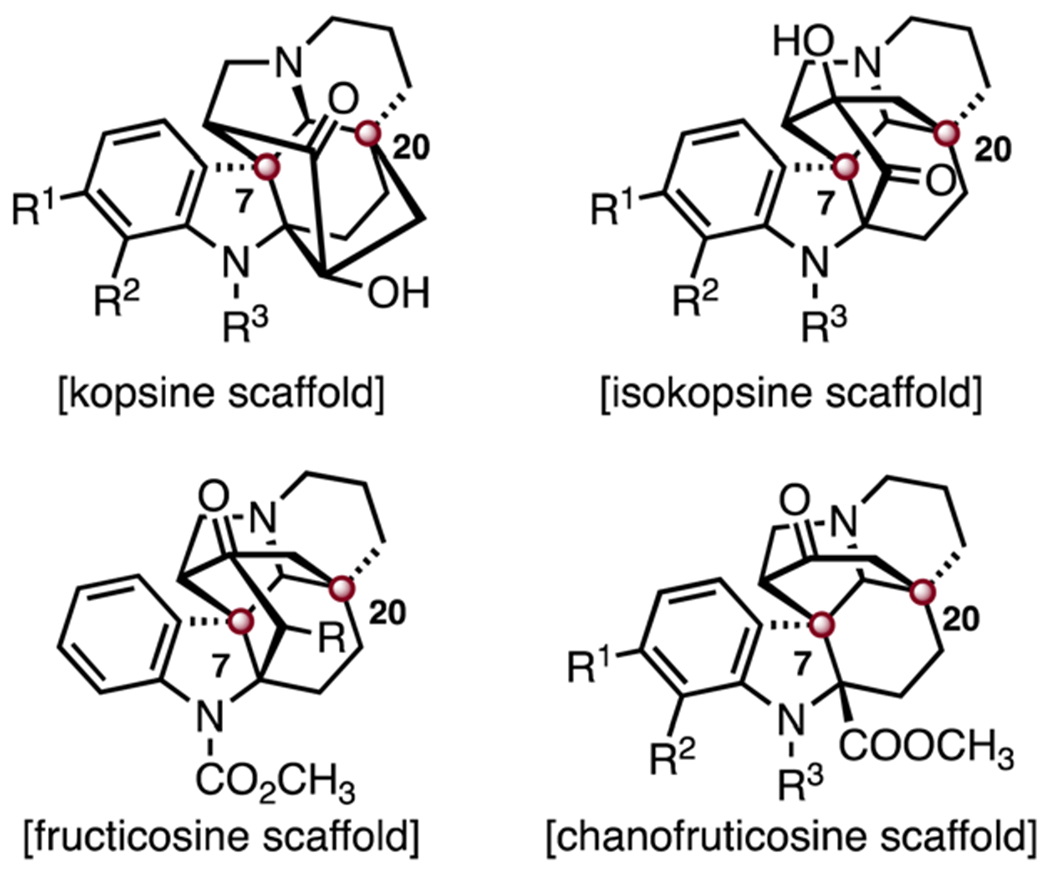

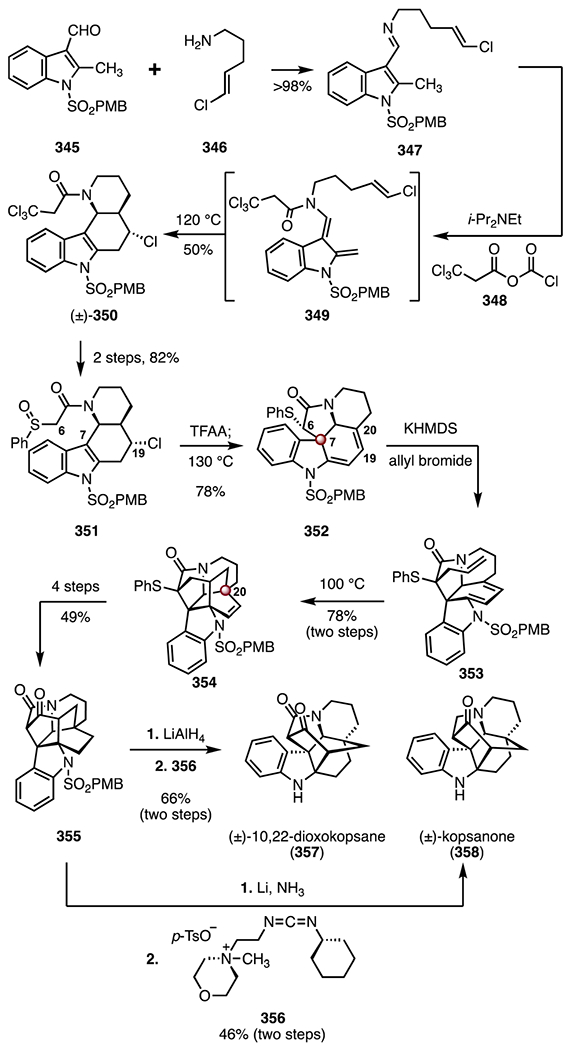

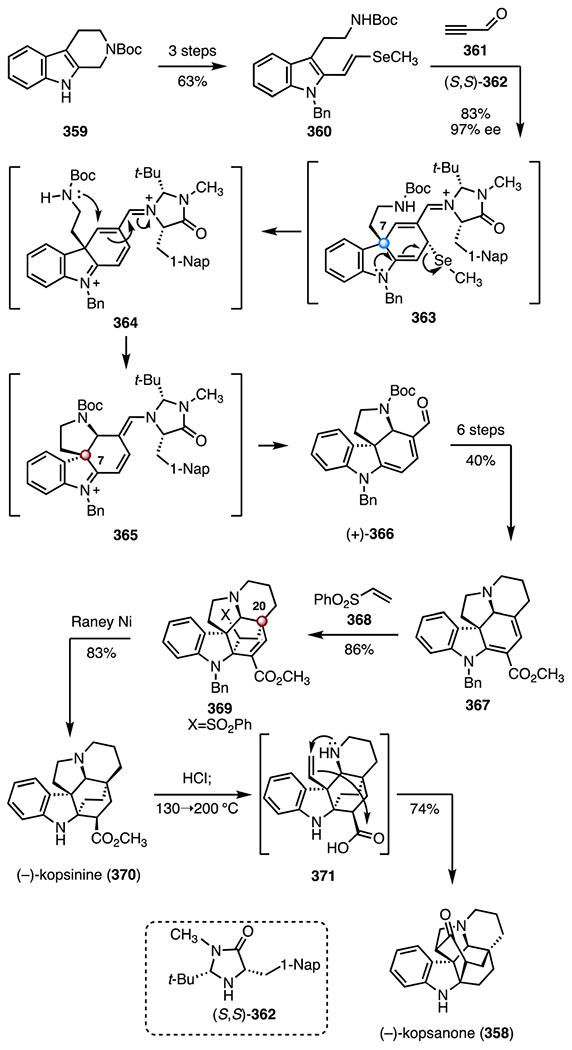

The akuammiline alkaloids are indole diterpenoid alkaloids isolated from Africa, India, and Southeast Asia.134 They possess opioid, cytotoxic, and glycine receptor antagonist activities.135 The akuammiline alkaloids contain a pentacyclic skeleton comprised of a tricyclic furoindoline residue (Scheme 36). The skeleton contains one TBCC at C7. Numerous syntheses and synthetic studies toward these isolates have been disclosed.136 Here, we discuss syntheses of two representative isolates, (−)-aspidophylline A (291)137–139 and (+)-strictamine (292).140–142

Scheme 36.

Structures of the akuammiline alkaloid scaffold, (−)-aspidophylline A (291), and (+)-strictamine (292).

(−)-Aspidophylline A (291) was isolated by Kam and co-workers in 2007. Its structure was determined by NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. In the same study, (−)-aspidophylline A (291) was found to reverse drug resistance in cancer cells (KB).143 (+)-Strictamine (292) was first isolated by the Ganguli group from Rhazya stricta Decaisne in 1966. Its structure was initially elucidated by NMR spectroscopy and MS,144 and later confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis.145

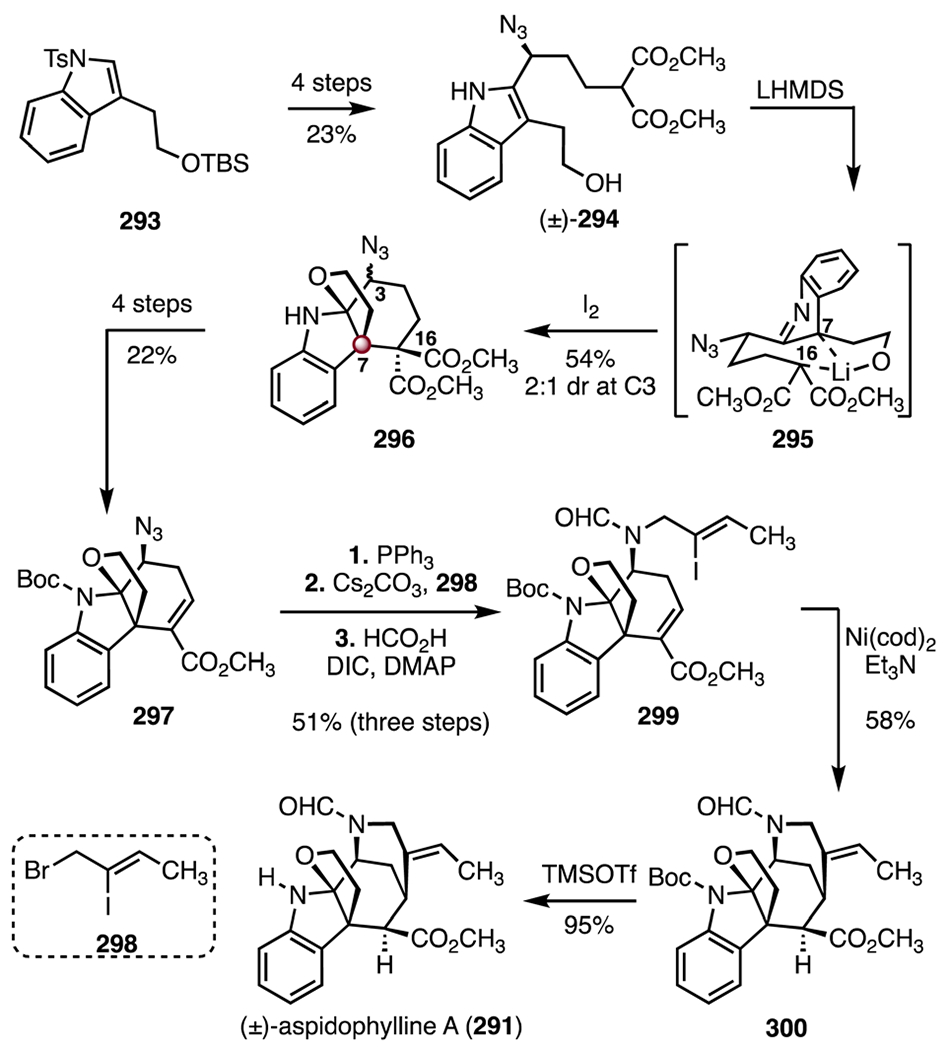

In 2014, Ma and co-workers disclosed a synthesis of (±)-aspidophylline A (291) that employed an oxidative coupling reaction to form the C7 TBCC (Scheme 37).137 Their synthesis began with the silyl ether 293, which was converted to the azide (±)-294 by a four-step sequence (23% overall). An intramolecular oxidative coupling of (±)-294 (lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, iodine, 54%, 2 : 1 dr at C3) provided a diastereomeric mixture of the ethers 296 with the C7 TBCC established.146 It was hypothesized that the free primary hydroxyl group in (±)-294 promoted formation of the chelated intermediate 295, which facilitated C7–C16 bond formation. The unsaturated ester 297 was prepared in four steps from the ether 296 (22% overall). A Staudinger reduction (triphenyl-phosphine), followed by N-alkylation (298, cesium carbonate) and N-formylation (formic acid, N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide, 4-dimethylaminopyridine), produced the vinyl iodide 299 (51%, three steps). Reductive cyclization (bis(cyclooctadiene) nickel(0), triethylamine) then furnished the pentacycle 300 (58%).147 Finally, removal of the tert-butyloxycarbonyl protecting group (trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate, 95%) delivered (±)-aspidophylline A (291). The synthesis was completed in fourteen steps and 0.77% overall yield.

Scheme 37.

Synthesis of (±)-aspidophylline A (291) by Ma and co-workers.137 LHMDS = lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, DIC = N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine, Ni(cod)2 = bis(cyclooctadiene) nickel(0), TMSOTf = trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate.

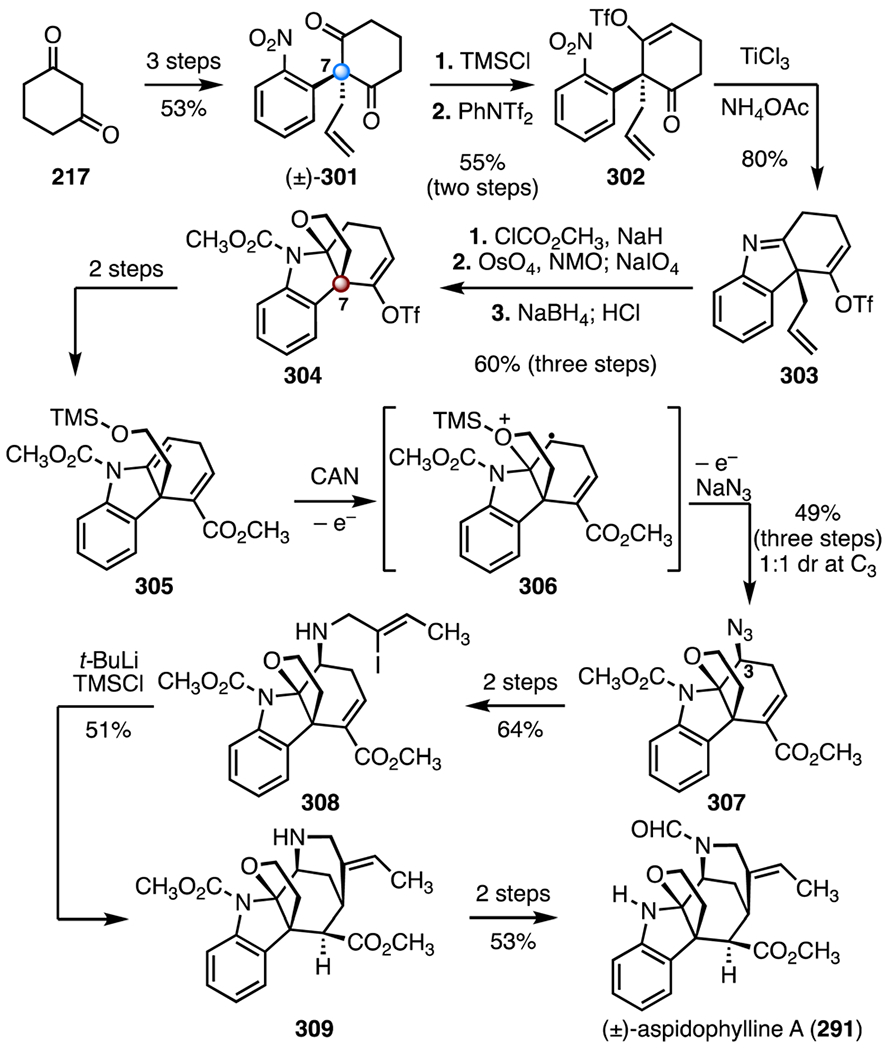

In 2014, Zhu and co-workers disclosed a total synthesis of (±)-aspidophylline A (291) that employed an oxidative azidoalkoxylation reaction to form the C3–N bond (Scheme 38).138 The known diketone (±)-301 was prepared in three steps from cyclohexane-1,3-dione (217, 53% overall). Here, the C7 quaternary center was established by SNAr and allylic alkylation reactions.148 A two-step sequence was developed to transform 301 to the vinyl trifluoromethanesulfonate 302 (trimethylsilyl chloride; bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)aniline, 55%, two steps). Reduction of the nitro group (titanium(iii) chloride, ammonium acetate), followed by in situ imine formation, provided the indolenine 303 (80%). Acylation of the indolenine 303 (methylchloroformate, sodium hydride) followed by oxidative cleavage and aldehyde reduction (osmium(viii) oxide, N-methylmorpholine N-oxide; then, sodium periodate; sodium borohydride; then, hydrochloric acid) generated the hemiaminal 304 (60%, three steps). The C7 TBCC was established in this step by hemiaminal formation. A two-step sequence was developed to convert the hemiaminal 304 to the enamine 305. In a key transformation, the enamine 305 was treated with ceric ammonium nitrate and sodium azide, resulting in production of the alkyl azide 307 as a single diastereomer after separation (49%, three steps, 1:1 dr at C3).149 This reaction was hypothesized to proceed through the radical cation intermediate 306. A two-step sequence was developed to convert the azide 307 to the vinyl iodide 308 (64% overall). An intramolecular 1,4-addition (tert-butyl lithium, trimethylsilyl chloride) then furnished the pentacycle 309 (51%). (±)-Aspidophylline A (291) was obtained by a two-step sequence (53% overall). The synthesis was completed in seventeen steps and 1.2% overall yield.

Scheme 38.

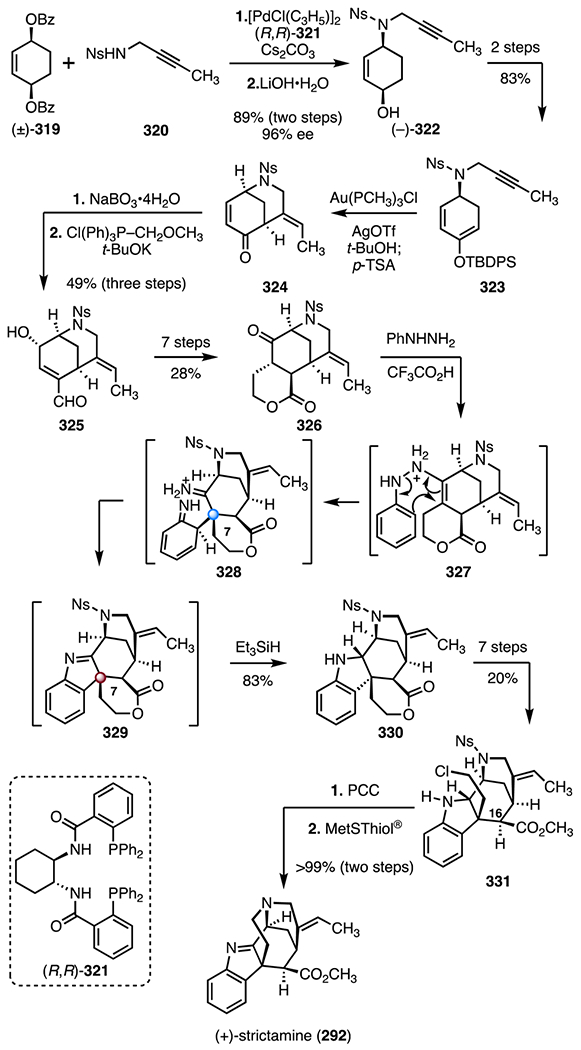

Synthesis of (±)-aspidophylline A (291) by Zhu and co-workers.138 TMSCl = trimethylsilyl chloride, PhNTf2 = bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl) aniline, NMO = N-methylmorpholine N-oxide, CAN = ceric ammonium nitrate.

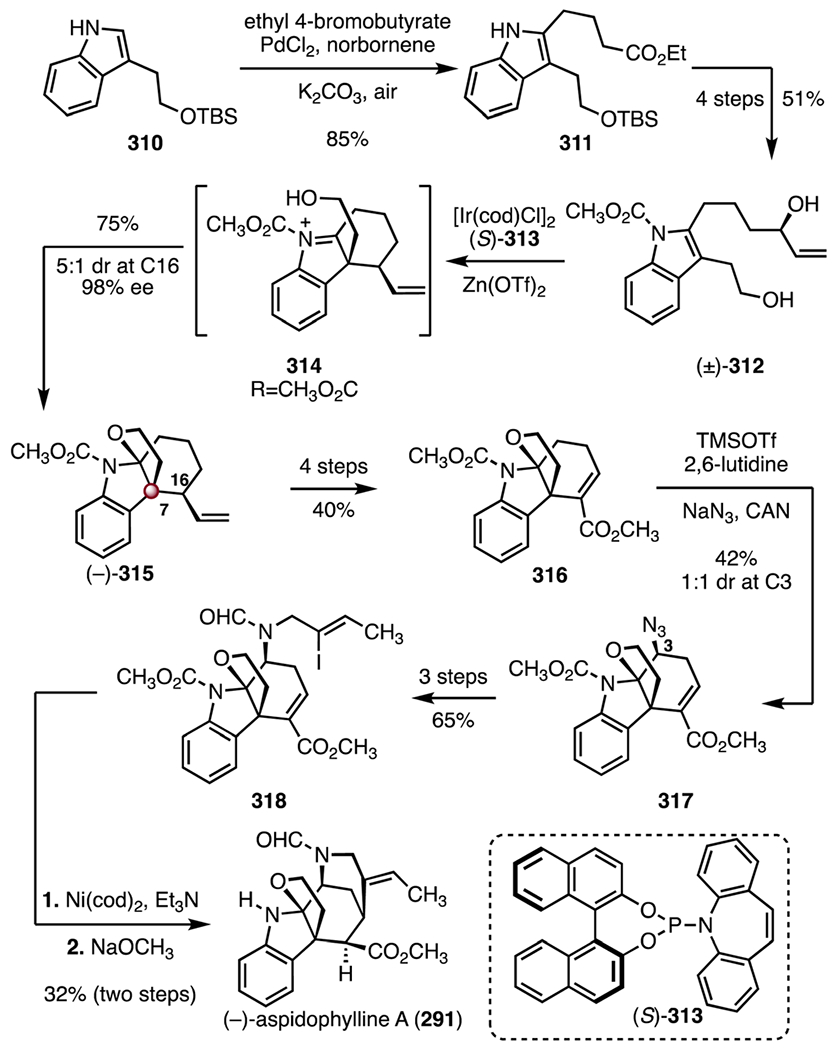

In 2016, the Yang group reported an enantioselective synthesis of (−)-aspidophylline A (291) that employed an enantioselective iridium-catalyzed iminium ion cyclization to form the C7 TBCC (Scheme 39).139 The synthesis began with a Jiao–Bach alkylation of the indole 310 (palladium(ii) chloride, norbornene, ethyl 4-bromobutyrate, potassium carbonate, air), to form the ester 311 (85%).150,151 The ester 311 was converted to the allylic alcohol (±)-312 in four steps (51% overall). In a key reaction, the allylic alcohol (±)-312 underwent an enantioselective iridium-catalyzed cyclization (chloro(1,5-cyclooctadiene)iridium(I) dimer, (S)-313, zinc(II) trifluoromethanesulfonate) to the cyclic aminal (−)-315, through the iminium ion intermediate 314 (75%, 5 : 1 dr at C16, 98% ee). The aminal (−)-315 was elaborated to the unsaturated ester 316 in four steps (40% overall). An oxidative azidoalkoxylation (trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate, 2,6-lutidine, sodium azide, ceric ammonium nitrate)138 provided the azide 317 (42%, 1:1 dr at C3). A three-step sequence was developed to transform the azide 317 to the vinyl iodide 318 (65% overall). Finally, a reductive cyclization, promoted by bis(cyclooctadiene) nickel(0) and triethylamine, followed by removal of the acetamide (sodium methoxide, 32%, two steps), delivered (−)-aspidophylline A (291). The route was completed in sixteen steps and 1.1% overall yield.

Scheme 39.

Synthesis of (−)-aspidophylline A (291) by Yang and co-workers.139 [Ir(cod)Cl]2 = chloro(1,5-cyclooctadiene)iridium(I) dimer, Zn(OTf)2 = zinc(II) trifluoromethanesulfonate, TMSOTf = trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate, CAN = ceric ammonium nitrate, Ni(cod)2 = bis(cyclooctadiene) nickel(0).