Abstract

Background

Endometrial carcinoma (EC) is a disease that predominantly affects peri- and post-menopausal women and its incidence has continued to rise over recent years. Since the gold standard for EC diagnosis—hysteroscopic biopsy—is invasive, expensive, and unsuitable for wide use, there is an urgent need for a non-invasive method that exhibits both high sensitivity and high specificity. We therefore investigated the efficacy of UterCAD (the uterine exfoliated cell chromosomal aneuploidy detector) using tampon-collected specimens for the early detection of EC.

Methods

We prospectively recruited 51 patients with a history of abnormal bleeding and who planned to undergo hysteroscopic examination or hysterectomy between March 2020 and January 2021. Before executing an invasive procedure, a tampon was inserted into the patient's vagina for 6 h to collect exfoliated cells from the uterine cavity. Total DNA was extracted and low-coverage whole-genome sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq X10, and we analyzed the differences in chromosomal status between women with EC and those bearing benign lesions using UterCAD.

Results

Thirty EC patients—including 26 with endometrioid carcinoma (EEC) and four with uterine serous carcinoma (USC), as well as 14 benign cases—were enrolled in our final analysis. Copy-number variations (CNVs) were detected in tampon specimens collected from 26 EC patients (83.3%), including 21 with EEC (80.7%) and four with USC (100%). In the benign group, only one woman with focal atypical hyperplasia presented with a 10q chromosomal gain (P < 0.001). In the EC group, the most common CNVs were copy gains of 8q (N = 14), 2q (N = 4), and 10q (N = 3); and copy losses of 2q (N = 3) and 17p (N = 2). When we stratified by FIGO stage, the CNV rates in stages IA, IB, and II/III were 83.3% (15/18), 85.7% (6/7), and 80.0% (4/5), respectively. At the optimal cutoff (|Z| ≥ 2.3), UterCAD discriminated 83.3% of EC cases from benign cases, with a specificity of 92.9%.

Conclusions

We initially reported that UterCAD could serve as a non-invasive method for the early detection of EC, especially in the rare and aggressive USC subtype. The use of UterCAD might thus avoid unnecessary invasive procedures and thereby reduce the treatment burden on patients.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, Early detection, Non-invasive, Low-coverage whole-genome sequencing

1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the second leading gynecologic malignancy worldwide, with an estimated 382,069 new cases and nearly 90,000 deaths in 2018 [1]. The lifetime risk of EC for a woman is approximately 3%, although the rate may be even higher in developed countries [[1], [2], [3]]. The annual incidence of EC continues to rise due to the worldwide prevalence of obesity, longer life expectancies, exposure to excessive estrogens and other carcinogenic factors [2]. In terms of early-stage tumors, although EC is highly curable—with a satisfactory 5-year overall survival of 95% for stage IA—the prognosis becomes much poorer for patients with regional and distant metastasis (the 5-year overall survival rates are 70% and 18%, respectively) [4]. According to its histologic characteristics, EC is classified into type I (endometrioid carcinoma, EEC) and type II (papillary serous, clear cell, and undifferentiated carcinoma). Type I tumors are usually estrogen-dependent and exhibit a high expression of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR); they account for 80–90% of all ECs, but for only 40% of EC-related deaths [2,5,6]. In contradistinction, type II EC is more invasive, is prone to be widespread and metastasize, and exhibits attenuated levels of ER and PR [6,7]. As there are no effective therapies currently available for type II EC, it is not surprising that the five-year survival is much poorer than for type I EC [8].

Population-based screening and detection of pre-cancerous and early-stage cancers are critical in identifying most, if not all cancers, and would reduce the mortality rate and relieve overall socio-economic burdens [9]. Taking cervical cancer as an example, the widely used high-risk HPV test and cytologic screening have in recent decades significantly reduced the incidence of high-grade cervical intraepithelial lesions and invasive cervical cancer [10]. Encouraged by these advances, the World Health Organization now expects to eliminate cervical cancer globally by 2030 [11]. Unfortunately, there is still no reliable modality for the screening and early detection of EC.

For patients with suspected EC, the most common symptoms include postmenopausal bleeding, abnormal uterine bleeding, or thickened endometrium/uterine mass as indicated by imaging tests [12]. To obtain the ultimate pathologic evidence, dilation and curettage (D&C) or hysteroscopic biopsy are the routine choices despite their elevated costs and inherent risks of anesthesia- or procedure-related complications [13]. Importantly, less than 5% of these aforementioned patients were ultimately shown to manifest EC; this implied that while over 95% of cases were benign, these women still had to undergo invasive procedures. Therefore, there is an urgent need for minimal or non-invasive approaches to the early detection of EC.

Human cancers are commonly characterized by their rapid growth, and tumor necrosis is not rare due to the relative unavailability of energy-supplying molecules [14]. Necrotic cancer cells can fall off the tumor mass and enter nearby cavities such as the esophagus [15], stomach [16], urinary tracts [17], and uterine/vaginal tracts [10,18]. These aspects of cancers provide an opportunity to collect exfoliated tumor cells from the uterine cavity for the early diagnosis of EC, and allow the exploitation of a much less invasive procedure than those currently used in the clinic [19,20].

In the present study, we collected exfoliated uterine cells using a tampon and analyzed them for chromosomal aberrations. A diagnostic model, that of the uterine exfoliated cell chromosomal aneuploidy detector (UterCAD) was then established and validated for the early detection of EC.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

From March 2020 to January 2021, 51 patients with suspected uterine diseases and who planned to undergo surgical resection were consecutively enrolled at the Department of Gynecology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. This prospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (2023-KY-0259), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Our study adhered to the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidelines of 2015 [21].

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As for the inclusion criteria, women with the following characteristics were eligible for recruitment: (1) those preoperatively diagnosed as suspected to have EC based on clinical data plus imaging tests such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging; or (2) those experiencing long-term (over 6 months) or repeated uncontrolled uterine bleeding. The exclusion criteria were: (1) women who had other cancers, such as breast cancer, invasive cervical cancer, and its per-cancerous lesion (HSIL). If the HPV and TCT were abnormal, a colposcopy examination and biopsy were used for the final diagnosis. (2) pregnancy and coagulopathy were excluded by testing blood β-HCG and coagulation-related factors (platelet counts, PT, APTT, INR, TT, FIB, and D-dimer), respectively. All participants underwent standard collection of tampon samples at admission. In brief, a routine pelvic examination was performed by the doctor and the sterile tampon was placed into deep vagina at the same time. Six hours later, the tampon was taken out and immediately placed into the stationary liquid (formalin). The samples could be stored at room temperature for up to 48 h. For EC cases, tumor stage was determined according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO, version 2018) [22].

2.3. DNA extraction

Total genomic DNA was isolated from the tampon specimens using the QIAseq DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen), and next-generation sequencing was executed as previously described [17]. DNA was fragmented into an average size of 300 bp, and then 100 ng of fragmented DNA was used for the preparation of sequencing libraries (NEBnext Ultra II).

2.4. Low-coverage whole-genome sequencing

For low-coverage whole-genome sequencing (WGS), libraries were prepared using the Kapa Hyper Prep Kit with custom adapters (IDT and Broad Institute) starting with 3 to 20 ng of DNA input (median, 5 ng); or approximately 1,000 to 7,000 haploid genome equivalents (GEs) were used for low-pass WGS. Up to 22 libraries were pooled and sequenced using 150 bp paired-end runs over a 1 × lane on a HiSeq X10 instrument (Illumina), and segment copy numbers were derived via a customized workflow UterCAD. Poor-quality sequencing data were flagged when the median absolute deviation of copy ratios (log2 ratio) between adjacent bins was 0.38 genome-wide, and the corresponding sample was then excluded. UterCAD results were blinded with respect to clinical parameters.

2.5. Statistical analysis

At least 10-M read-pairs were collected for each sample, and the reads were mapped to human reference genome HG19. Genomic coverage was counted using SAMtools mpileup software, and we then calculated the average coverage for each 200-kb bin. Z-scores for each bin were normalized using formula 1 below:

| 1 |

The circular binary segmentation (CBS) algorithm was subsequently used to identify significant genomic breakpoints and copy number-changed genomic segments using the R package “DNACopy”. P < 0.05 was defined to be the statistically significant binary segmentation. The absolute segment values were used for the following analysis. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of UterCAD.

Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as the mean ± standard deviation or the median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. We analyzed continuous variables using the Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables by Pearson's Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact-probability test, as appropriate (missing data were discarded from our analyses). All statistical evaluations were performed with SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), R software (version 3.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and MedCalc software (version 19.1; MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium); and we considered P < 0.05 to be statistically significant. Our data and original R coding used in the statistical analyses are available upon request.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

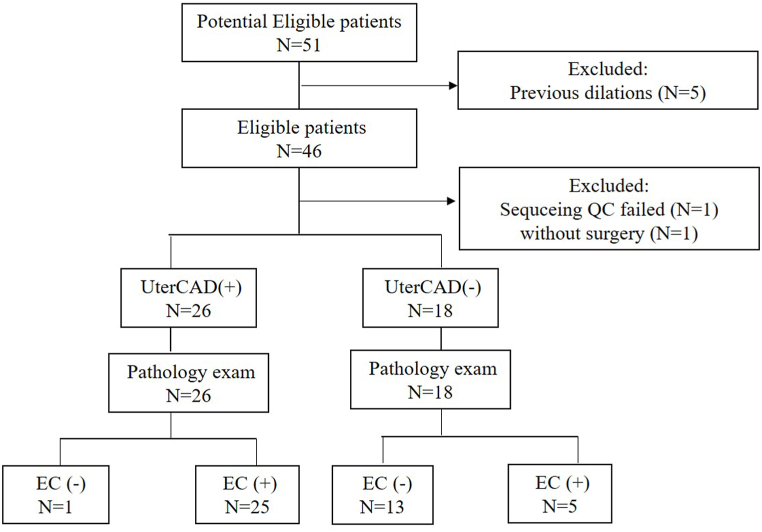

In this study, 51 patients were consecutively enrolled, and post hysterectomy ± lymphadenectomy we detected no cancer cells in the five patients who were diagnosed with EC by D&C at other hospitals. One of these patients withdrew due to personal reasons and one patient was excluded because of low DNA quality. A total of 44 patients were thus ultimately eligible for UterCAD analysis. The STARD flow diagram is depicted in Fig. 1, and the baseline characteristics of these patients are delineated in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1. According to the final pathology, we divided the patients into an EC group (N = 30, including 26 patients with EEC and four with USC) and a benign group (N = 14, consisting of one patient with focal atypical hyperplasia, five with endometrial polyps, three with endometrial hyperplasia, two with leiomyomas, and three with endometritis).

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of this study. QC: quality control; EC: endometrial cancer.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 44 patients.

| Parameters | Diagnosis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Benign | EC | P value | |

| Age | ≤55y | 3 (6.8%) | 14 (31.8%) | 0.184 |

| >55y | 11 (25.0%) | 16 (36.4%) | ||

| BMI | ≤25 | 3 (6.8%) | 11 (25.0%) | 0.507 |

| >25 | 11 (25.0%) | 19 (43.2%) | ||

| menopause | No | 0 | 9 (20.5%) | 0.058 |

| Yes | 14 (31.8%) | 21 (47.7%) | ||

| postmenopause period | No | 0 | 9 (20.5%) | 0.065 |

| ≤8y | 9 (20.5%) | 12 (27.3%) | ||

| >8y | 5 (11.4%) | 9 (20.5%) | ||

| History | No | 14 (31.8%) | 15 (34.1%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 13 (29.5%) | ||

| Diabetes | 0 | 2 (4.5%) | ||

| Gyn-history | No | 14 (31.8%) | 24 (54.5%) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 0 | 6 (13.6%) | ||

BMI: body mass index; EC: endometrial cancer; Gyn-history: the history of benign gynecologic diseases, such as abnormal menstrual cycle, atypical or non-atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium, polyps, and so on.

3.2. CNV profiles in tampon-collected specimens

The genome-wide landscape of CNVs for all patients is shown in Supplementary Table 2. CNVs were detected in 83.3% (25/30) of patients with EC, but in only 7.1% (1/14) of benign cases (P < 0.001). The most common copy-number gain was detected in chromosomes 8q (N = 14), 2q (N = 4), and 10q (N = 3); while copy loss principally occurred in 2q (N = 3) and 17p (N = 2). In the benign group, only one 10q gain was uncovered in a patient with focal atypical hyperplasia (the precursor of EEC). The representative images of CNVs in EEC, USC and benign cases were shown in Fig. 2A–C.

Fig. 2.

The representative CNVs in different ECs and benign cases. A: the copy gain of 8q and 2q in an endometrioid carcinoma; B: the multiple CNVs in a uterine serous carcinoma; C: no CNVs were detected in a benign case.

3.3. Use of UterCAD to differentiate ECs from benign diseases

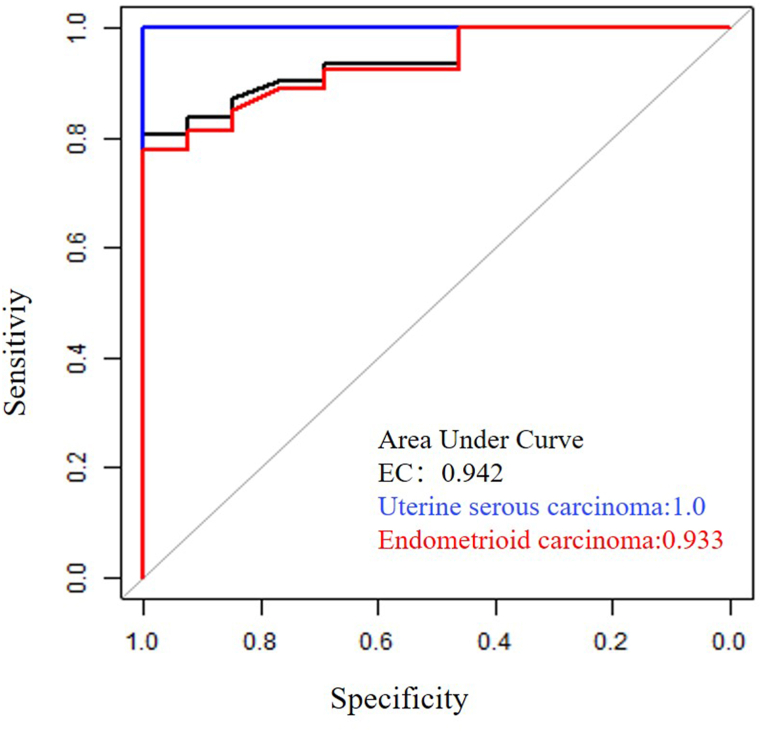

Z-scores for each chromosomal arm (1p, 1q, 2p, 2q, 3p, 3q, 4p, 4q, 5p, 5q, 6p, 6q, 7p, 7q, 8p, 8q, 9p, 9q, 10p, 10q, 11p, 12q, 13q, 14q, 15q, 16p, 16q, 17p, 17q, 18p, 18q, 19p, 19q, 20p, 20q, 21p, 21q, and 22q) were calculated normalized to benign controls. When we further explored the Z-score value for each chromosome arm in differentiating EC from benign diseases (Table 2), we noted that the areas under the curve (AUCs) for each arm ranged from 0.463 to 0.749 (with a median AUC of 0.549). Chr8q and chr6q showed higher diagnostic accuracy relative to the others, with AUCs of 0.749 and 0.658, respectively (Table 2). We then combined all the chromosomal information to construct a diagnostic model of EC and determined an optimal cutoff (|Z| ≥ 2.30) using the Youden Index. At this cutoff, UterCAD exhibited a sensitivity of 83.3% and a specificity of 92.9% (Table 3), with an AUC of 0.91 (0.83–0.99) (Fig. 3)—superior to the result from any single chromosome arm. Although a higher cutoff (|Z| = 3) showed greater specificity (reaching 100.0%), it significantly compromised the sensitivity of UterCAD, reducing it to as low as 73.3%. When the cutoff was lower to |Z| = 2, the sensitivity of UterCAD was 90.0%, while the specificity sharply declined to 64.3%. Regarding different pathologic types, the use of UterCAD identified 80.8% (21/26) of EECs and 100% (4/4) of USCs (Table 3). As shown in Fig. 3, the AUCs for EC, EEC, and USC were 0.942, 0.933, and 1.00, respectively.

Table 2.

The individual efficacy for EC detection depending on CNVs in each chromosome arm.

| Marker | AUC | 95%CI_lower | 95%CI_upper |

|---|---|---|---|

| chr8q | 0.749 | 0.604 | 0.895 |

| chr6q | 0.658 | 0.479 | 0.836 |

| chr4p | 0.643 | 0.456 | 0.829 |

| chr12p | 0.636 | 0.454 | 0.819 |

| chr18q | 0.623 | 0.442 | 0.804 |

| chr2p | 0.623 | 0.437 | 0.808 |

| chr19p | 0.603 | 0.434 | 0.772 |

| chr10q | 0.612 | 0.432 | 0.791 |

| chr14q | 0.620 | 0.425 | 0.816 |

| chr9q | 0.617 | 0.417 | 0.816 |

| chr1q | 0.586 | 0.412 | 0.759 |

| chr17q | 0.586 | 0.399 | 0.772 |

| chr11q | 0.576 | 0.377 | 0.775 |

| chr13q | 0.563 | 0.374 | 0.753 |

| chr21p | 0.572 | 0.367 | 0.777 |

| chrXp | 0.578 | 0.365 | 0.791 |

| chr9p | 0.565 | 0.362 | 0.767 |

| chr21q | 0.553 | 0.358 | 0.749 |

| chr20q | 0.552 | 0.358 | 0.747 |

| chr8p | 0.547 | 0.355 | 0.739 |

| chr4q | 0.542 | 0.354 | 0.731 |

| chr15q | 0.567 | 0.350 | 0.784 |

| chr19q | 0.532 | 0.346 | 0.718 |

| chr1p | 0.553 | 0.346 | 0.761 |

| chr17p | 0.516 | 0.337 | 0.695 |

| chr16q | 0.530 | 0.335 | 0.725 |

| chr5p | 0.548 | 0.334 | 0.763 |

| chr7q | 0.509 | 0.331 | 0.687 |

| chr7p | 0.509 | 0.326 | 0.692 |

| chr3p | 0.512 | 0.324 | 0.701 |

| chr11p | 0.512 | 0.320 | 0.704 |

| chr12q | 0.480 | 0.294 | 0.667 |

| chr10p | 0.474 | 0.290 | 0.658 |

| chr22q | 0.490 | 0.286 | 0.694 |

| chr6p | 0.480 | 0.272 | 0.688 |

| chr3q | 0.448 | 0.267 | 0.629 |

| chr2q | 0.428 | 0.257 | 0.599 |

| chr20p | 0.449 | 0.257 | 0.641 |

| chr16p | 0.448 | 0.257 | 0.639 |

| chr18p | 0.462 | 0.256 | 0.667 |

| chr5q | 0.463 | 0.255 | 0.671 |

Table 3.

The performance of UterCAD for EC early detection at different cutoffs.

| AUC (95% CI) | Cutoff | TN | TP | FN | FP | PPV | NPV | Specificity | Sensitivity | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UterCAD | 2 | 9 | 27 | 3 | 5 | 84.4% | 75.0% | 64.3% | 90.0% | 81.8% | |

| CHR1-22 | 0.91 (0.83–0.99) | 2.3 | 13 | 25 | 5 | 1 | 96.2% | 72.2% | 92.9% | 83.3% | 86.4% |

| 3 | 14 | 22 | 8 | 0 | 100.0% | 63.6% | 100.0% | 73.3% | 81.8% |

TN: true negative; TP: true positive; FN: false negative; FP: false true positive; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; CHR: chromosome.

Fig. 3.

Area under curves (AUCs) of UterCAD test for the early detection of endometrial carcinoma.

3.4. Correlations between UterCAD results and clinical parameters

We further explored whether clinical parameters affect the UterCAD results. As shown in Table 4, there was no significant correlation between the positive rate of UterCAD and clinical parameters, including age (P = 0.985), BMI (P = 0.997), postmenopausal period (P = 0.235), pathology (P = 0.933), tumor stage (P = 0.966), grade (P = 0.382), lymph vascular space invasion (P = 0.872) and lymph node metastasis (P = 0.433). These results indicated the universality of UterCAD in the whole EC population.

Table 4.

Correlations between UterCAD results and clinical parameters.

| UterCAD results |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | P value | ||

| Age | ≤55y | 2 | 11 | 0.985 |

| >55y | 3 | 14 | ||

| BMI | ≤25 | 2 | 9 | 0.997 |

| >25 | 3 | 16 | ||

| Postmenopause period | No | 0 | 4 | 0.235 |

| ≤8y | 2 | 15 | ||

| >8y | 3 | 6 | ||

| Pathology | EEC | 5 | 21 | 0.933 |

| USC | 0 | 4 | ||

| Stage | IA | 3 | 15 | 0.966 |

| IB | 1 | 6 | ||

| II-III | 1 | 4 | ||

| Grade | I | 0 | 6 | 0.382 |

| II | 3 | 14 | ||

| III | 2 | 5 | ||

| LVSI | Negative | 4 | 20 | 0.872 |

| Positive | 1 | 5 | ||

| LN metastasis | Negative | 4 | 23 | 0.433 |

| Positive | 1 | 2 | ||

BMI: body mass index; EEC: endometrioid carcinoma; USC: uterine serous carcinoma; LVSI: lymph vascular invasion; LN: lympho node.

4. Discussion

EC is predominantly found in peri- and post-menopausal women; the commonly presented symptoms include vaginal drainage and bleeding [8]. Current therapies achieve satisfactory prognoses in early-stage EC with a five-year survival rate of 90% or even higher. Moreover, patients with the earliest form of EC (stage IA) can achieve a cure using only drugs like progestins and thus preserve their fertilities [23]. Such results are of great significance to young women who wish to give a birth in the future. Unfortunately, the extensive treatments (including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy) used in late-stage EC fail to control tumor progression and thereby even enhance mortality risk. Thus, we recognize an urgent need to establish and optimize methods to detect EC at the incipient stage.

There are numerous historical reports which committed to exploring less- or non-invasive methods for early detection of EC. For example, Papanicolaou testing constitutes a minimally invasive and efficient means to screen and detect cervical cancer early [24]. In addition to cervical epithelial cells, Pap-smear samples also retrieve small populations of cells from the upper reproductive tract (including the endometrium, fallopian tube, and even ovarian epithelium) [25]. In a panel of 21 ovarian cancer patients, Jeffrey et al. successfully detected tumor-derived mutations in 37.5% of samples collected using the Pap test, which strongly indicated that this method might be a candidate for the early screening or detection of malignancies from upper genital tract like ovarian cancer and EC [18]. Not surprisingly, in another study, Kinde et al. reported that the same mutation profiles were identified in specimens collected by both Pap smear and surgery in all the 24 EC patients, which further supported that these exfoliated tumor cells could be collected by Pap smear and provide qualified DNA for the genomic analysis [25]. In a much larger EC population, the authors verified that the combined analysis of 18 representative genes and aneuploidy could discriminate 81% of 382 ECs, of which 78% cases were early-stage tumors [10]. These findings strongly indicate that the Pap test is the preferred choice for the non-invasive detection of EC. However, one limitation of the Pap test is the short contact time between cervix and brush, potentially compromising the number of harvested cancer cells and impairing its overall efficacy. Thus, we herein applied the 6-h use of tampons to improve sample collection for subsequent analysis; and our data revealed that 98.0% (50/51) of specimens provided abundant DNA for low-coverage WGS, showing the superiority of our long-time collection protocol.

In this pilot study, our UterCAD model focused on the CNVs in tampon-collected samples and achieved high sensitivity (83.3%) and specificity (92.9%) in distinguishing EC from benign disease. As a nearly non-invasive method, the efficacy of UterCAD in the early detection of EC is promising. Moreover, the sensitivity of UterCAD is as high as 83.3% and 85.7% in stage IA and stage IB ECs, which seems better than those reported by previous studies [10,18,25]. Collectively, these findings indicate the powerful efficacy of UterCAD in detecting early ECs.

Besides the abnormal copy numbers, a group of EC patients might present significant gene mutations or other genetic/epigenetic alterations that should also be considered to optimize the current model [26,27]. Up to date, several well-designed studies have investigated this issue. In 2015, DNA hypermethylation was successfully detected in tampon-collected samples from EC patients, proposing that this method could be used for the non-invasive detection of EC [20]. Moreover, in a prospective multi-center study, the mutational analysis of Pap samples yielded a sensitivity of 78% in the early detection of EC [28]. During the execution of our current study, Bakkum-Gamez et al. reported the simultaneously detection of copy number, methylation and mutations in tampon-collected specimens could achieve a sensitivity of 92% with a specificity of 86% [19]. Intriguingly, we noted that the individual sensitivities of three molecular tests were under 60%, which might be attributable to the significant heterogeneity of the EC population [19]. Moreover, in despite that the combined strategy showed more powerful efficacy, a much higher cost might hinder its use in clinic. In the future, one of our projects is to explore the feasibility of combining UterCAD with other detection methods.

According to the molecular patterns of ECs, frequent mutations were common in POLE (ultra-mutated) and MSI (hypermutated) groups, while CNVs were often discerned in the CN-high (serous-like) group [26]. Besides genetic alterations, the epigenetic and post-transcriptional modulations also played an important role in EC, such as methylation, histone acetylation, and non-coding RNAs (including microRNA, long non-coding RNA, piwiRNA and circular RNA) [29,30]. Although relatively rare, USC is much more aggressive than its endometrioid counterparts and responds poorly to current therapies. Therefore, the early detection of USC would be more meaningful in the clinic, which could benefit both the patients and society as a whole. In our study, UterCAD successfully discriminated all the four USCs, showing its relative superiority. We noted that Z scores for the USC cases were much higher than those for the EEC cases, which also supported that vigorous CNVs existed in USCs.

In our study, five patients diagnosed as EC by prior D&C were excluded due to the negative findings revealed by both UterCAD and final pathology after hysterectomy. The reason for this might be the tumors were very small and localized, wherein all cancer cells may have been completely removed during the first biopsy. This is not a rare phenomenon in the clinical setting and advances the evidence with respect to the high specificity of the UterCAD test.

In addition, UterCAD might also be applied for the monitoring of stage IA EEC who accepted the fertility-sparing treatments. For these patients, the routine treatments usually lasted for 12 months or even longer. Every other three months, the hysteroscopy-assisted endometrial biopsy should be performed to evaluate the therapeutic effect, which could cause significant harms to uterus cavity and potentially influencing a subsequent pregnancy [23]. We proposed that UterCAD might be helpful to reduce the biopsy times and predict disease progression which requires timely cessation of the conservative treatment.

Some limitations should be noted in this pilot study with a small sample size. The recruitment of additional stage II/III cases (we had five, or 16.7% of the total) might present sizable interference on the efficacy of UterCAD. Thus, our findings need further validations in a larger group of more early-stage EC patients. In addition, it would be worth merging supplemental molecular tests such as typical mutation and methylation into UterCAD, although cost-effectiveness should also be considered.

During the last two years, several other projects also demonstrated the efficacy of low-coverage genome-sequencing for early cancer detection and recurrence prediction. For example, Guan et al. detected CNVs in urine exfoliated cells using the low-coverage whole genome sequencing and found that CNVs were positive in 81.2% prostate carcinoma while 0% in benign prostate diseases. A diagnosis model (incorporating all CNVs) presented a sensitivity higher than 80%, with a perfect specificity (100%) [31]. In a pilot prospective study, Yu et al. proved that CNVs (especially chromosome 7p gain) in plasma could serve as a specific predictor for the early-stage lung carcinoma [32]. Moreover, Chen et al. performed the CNVs in plasma cell-free DNA from 67 patients with bone metastases, irrespective of the original cancer types. They reported that CNVs examination is superior to traditional methods in predicting patient outcomes [33]. Collectively, we believe the potent value of UterCAD is worthy to be further explored in the future.

In conclusion, we herein demonstrated that UterCAD represented a satisfactory and novel method for the early detection of EC. This minimally invasive method displayed high sensitivity and specificity, particularly with respect to USC which was more aggressive and lethal. Further studies are ongoing to validate our findings and explore more cost-effective approaches for the clinical application of UterCAD.

Author contribution statement

Haifeng qiu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data;Wrote the paper.

Min Wang: Performed the experiments.

Tingting Cao, Yun Feng and Ying Zhang: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Ruixia Guo: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ziliang Qian and Lijuan Zhai (Hongyuan Biotechnology, Suzhou, China) for technical assistances during the UterCAD analysis. We also thank the letpub company for the help during preparation of English writing.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19323.

Contributor Information

Haifeng Qiu, Email: fccqiuhf@zzu.edu.cn.

Ruixia Guo, Email: fccguorx@zzu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu K.H., Broaddus R.R. Endometrial cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:2053–2064. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang X., Tang H., Chen T. Epidemiology of gynecologic cancers in China. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018;29:e7. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Wagle N.S., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2023;73:17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang H.P., Wentzensen N., Trabert B., Gierach G.L., Felix A.S., Gunter M.J., Hollenbeck A., Park Y., Sherman M.E., Brinton L.A. Endometrial cancer risk factors by 2 main histologic subtypes: the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013;177:142–151. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Setiawan V.W., Yang H.P., Pike M.C., McCann S.E., Yu H., Xiang Y.B., Wolk A., Wentzensen N., Weiss N.S., Webb P.M., van den Brandt P.A., van de Vijver K., Thompson P.J., Strom B.L., Spurdle A.B., Soslow R.A., Shu X.O., Schairer C., Sacerdote C., Rohan T.E., Robien K., Risch H.A., Ricceri F., Rebbeck T.R., Rastogi R., Prescott J., Polidoro S., Park Y., Olson S.H., Moysich K.B., Miller A.B., McCullough M.L., Matsuno R.K., Magliocco A.M., Lurie G., Lu L., Lissowska J., Liang X., Lacey J.V., Jr., Kolonel L.N., Henderson B.E., Hankinson S.E., Hakansson N., Goodman M.T., Gaudet M.M., Garcia-Closas M., Friedenreich C.M., Freudenheim J.L., Doherty J., De Vivo I., Courneya K.S., Cook L.S., Chen C., Cerhan J.R., Cai H., Brinton L.A., Bernstein L., Anderson K.E., Anton-Culver H., Schouten L.J., Horn-Ross P.L. Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:2607–2618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobo F.D., Thomas E. Type II endometrial cancers: a case series. J. MidlifeHealth. 2016;7:69–72. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.185335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton C.A., Pothuri B., Arend R.C., Backes F.J., Gehrig P.A., Soliman P.T., Thompson J.S., Urban R.R., Burke W.M. Endometrial cancer: a society of gynecologic oncology evidence-based review and recommendations. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021;160:817–826. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith R.A., Andrews K.S., Brooks D., Fedewa S.A., Manassaram-Baptiste D., Saslow D., Wender R.C. Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening, CA Cancer. J. Clin. 2019;69:184–210. doi: 10.3322/caac.21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y., Li L., Douville C., Cohen J.D., Yen T.T., Kinde I., Sundfelt K., Kjaer S.K., Hruban R.H., Shih I.M., Wang T.L., Kurman R.J., Springer S., Ptak J., Popoli M., Schaefer J., Silliman N., Dobbyn L., Tanner E.J., Angarita A., Lycke M., Jochumsen K., Afsari B., Danilova L., Levine D.A., Jardon K., Zeng X., Arseneau J., Fu L., Diaz L.A., Jr., Karchin R., Tomasetti C., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B., Fader A.N., Gilbert L., Papadopoulos N. Evaluation of liquid from the Papanicolaou test and other liquid biopsies for the detection of endometrial and ovarian cancers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aap8793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Draft global strategy towards the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. https://wwwwhoint/docs/default-source/cervical-cancer/cerv-cancer-elimn-strategy-16dec-12pmpdf

- 12.Brooks R.A., Fleming G.F., Lastra R.R., Lee N.K., Moroney J.W., Son C.H., Tatebe K., Veneris J.L. Current recommendations and recent progress in endometrial cancer. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69:258–279. doi: 10.3322/caac.21561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denschlag D., Ulrich U., Emons G. The diagnosis and treatment of endometrial cancer: progress and controversies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;108:571–577. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanahan D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:31–46. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Townsend D., Miljkovic M., Bird B., Lenau K., Old O., Almond M., Kendall C., Lloyd G., Shepherd N., Barr H., Stone N., Diem M. Infrared micro-spectroscopy for cyto-pathological classification of esophageal cells. Analyst. 2015;140:2215–2223. doi: 10.1039/c4an01884b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohki A., Abe N., Yoshimoto E., Hashimoto Y., Takeuchi H., Nagao G., Masaki T., Mori T., Ohkura Y., Sugiyama M. Gastric washing by distilled water can reduce free gastric cancer cells exfoliated into the stomach lumen. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:998–1003. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0824-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng S., Ying Y., Xing N., Wang B., Qian Z., Zhou Z., Zhang Z., Xu W., Wang H., Dai L., Gao L., Zhou T., Ji J., Xu C. Noninvasive detection of urothelial carcinoma by cost-effective low-coverage whole-genome sequencing from urine-exfoliated cell DNA. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:5646–5654. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krimmel-Morrison J.D., Ghezelayagh T.S., Lian S., Zhang Y., Fredrickson J., Nachmanson D., Baker K.T., Radke M.R., Hun E., Norquist B.M., Emond M.J., Swisher E.M., Risques R.A. Characterization of TP53 mutations in Pap test DNA of women with and without serous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020;156:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.11.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sangtani A., Wang C., Weaver A., Hoppman N.L., Kerr S.E., Abyzov A., Shridhar V., Staub J., Kocher J.A., Voss J.S., Podratz K.C., Wentzensen N., Kisiel J.B., Sherman M.E., Bakkum-Gamez J.N. Combining copy number, methylation markers, and mutations as a panel for endometrial cancer detection via intravaginal tampon collection. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020;156:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakkum-Gamez J.N., Wentzensen N., Maurer M.J., Hawthorne K.M., Voss J.S., Kroneman T.N., Famuyide A.O., Clayton A.C., Halling K.C., Kerr S.E., Cliby W.A., Dowdy S.C., Kipp B.R., Mariani A., Oberg A.L., Podratz K.C., Shridhar V., Sherman M.E. Detection of endometrial cancer via molecular analysis of DNA collected with vaginal tampons. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015;137:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.01.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossuyt P.M., Reitsma J.B., Bruns D.E., Gatsonis C.A., Glasziou P.P., Irwig L., Lijmer J.G., Moher D., Rennie D., de Vet H.C., Kressel H.Y., Rifai N., Golub R.M., Altman D.G., Hooft L., Korevaar D.A., Cohen J.F., Group S. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h5527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amant F., Mirza M.R., Koskas M., Creutzberg C.L. Cancer of the corpus uteri. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 2):37–50. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janda M., Obermair A. Fertility-sparing management of early-stage endometrial cancer in reproductive age women: current treatment outcomes and future directions. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2021;31:1506–1507. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2021-003192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiffman M., Solomon D. Clinical practice. Cervical-cancer screening with human papillomavirus and cytologic cotesting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2324–2331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1210379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinde I., Bettegowda C., Wang Y., Wu J., Agrawal N., Shih I., Kurman R., Dao F., Levine D.A., Giuntoli R., Roden R., Eshleman J.R., Carvalho J.P., Marie S.K., Papadopoulos N., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B., Diaz L.A., Jr. Evaluation of DNA from the Papanicolaou test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004952. 167ra164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kandoth C., Schultz N., Cherniack A.D., Akbani R., Liu Y., Shen H., Robertson A.G., Pashtan I., Shen R., Benz C.C., Yau C., Laird P.W., Ding L., Zhang W., Mills G.B., Kucherlapati R., Mardis E.R., Levine D.A. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dou Y., Kawaler E.A., Cui Z.D., Gritsenko M.A., Huang C., Blumenberg L., Karpova A., Petyuk V.A., Savage S.R., Satpathy S., Liu W., Wu Y., Tsai C.F., Wen B., Li Z., Cao S., Moon J., Shi Z., Cornwell M., Wyczalkowski M.A., Chu R.K., Vasaikar S., Zhou H., Gao Q., Moore R.J., Li K., Sethuraman S., Monroe M.E., Zhao R., Heiman D., Krug K., Clauser K., Kothadia R., Maruvka Y., Pico A.R., Oliphant A.E., Hoskins E.L., Pugh S.L., Beecroft S.J.I., Adams D.W., Jarman J.C., Kong A., Chang H.Y., Reva B., Liao Y., Rykunov D., Colaprico A., Chen X.S., Czekanski A., Jedryka M., Matkowski R., Wiznerowicz M., Hiltke T., Boja E., Kinsinger C.R., Mesri M., Robles A.I., Rodriguez H., Mutch D., Fuh K., Ellis M.J., DeLair D., Thiagarajan M., Mani D.R., Getz G., Noble M., Nesvizhskii A.I., Wang P., Anderson M.L., Levine D.A., Smith R.D., Payne S.H., Ruggles K.V., Rodland K.D., Ding L., Zhang B., Liu T., Fenyo D. Proteogenomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Cell. 2020;180:729–748.e726. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reijnen C., van der Putten L.J.M., Bulten J., Snijders M., Kusters-Vandevelde H.V.N., Sweegers S., Vos M.C., van der Wurff A.A.M., Ligtenberg M.J.L., Massuger L., Eijkelenboom A., Pijnenborg J.M.A. Mutational analysis of cervical cytology improves diagnosis of endometrial cancer: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Int. J. Cancer. 2020;146:2628–2635. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavaliere A.F., Perelli F., Zaami S., Piergentili R., Mattei A., Vizzielli G., Scambia G., Straface G., Restaino S., Signore F. Towards personalized medicine: non-coding RNAs and endometrial cancer. Healthcare. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/healthcare9080965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piergentili R., Zaami S., Cavaliere A.F., Signore F., Scambia G., Mattei A., Marinelli E., Gulia C., Perelli F. Non-coding RNAs as prognostic markers for endometrial cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22063151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan Y., Wang X., Guan K., Wang D., Bi X., Xiao Z., Xiao Z., Shan X., Hu L., Ma J., Li C., Zhang Y., Shou J., Wang B., Qian Z., Xing N. Copy number variation of urine exfoliated cells by low-coverage whole genome sequencing for diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. Genom. 2022;15:104. doi: 10.1186/s12920-022-01253-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu H.J., Yu X.J., Tang J., Lu X., Ma H.T. A pilot prospective study of plasma cell-free DNA whole-genome sequencing identified chromosome 7p copy number gains as a specific biomarker for early lung cancer detection. Neoplasma. 2021;68:567–571. doi: 10.4149/neo_2021_201106N1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S., Yang M., Zhong N., Yu D., Jian J., Jiang D., Xiao Y., Wei W., Wang T., Lou Y., Zhou Z., Xu W., Wan W., Wu Z., Wei H., Liu T., Zhao J., Yang X., Xiao J. Quantified CIN score from cell-free DNA as a novel noninvasive predictor of survival in patients with spinal metastasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.767340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.