Abstract

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy affect up to 8% of pregnancies but updated national trends are lacking. We performed a repeated cross-sectional analysis of singleton pregnancies delivered >20 weeks’ gestation in the U.S. National Vital Statistics System from 1989 to 2020. Temporal trends in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic hypertension, and eclampsia were characterized using joinpoint regression. Overall 122,329,914 deliveries were included. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy increased from 2.79% in 1989 to 8.22% in 2020, representing an average annual percent change of 3.6% (95% CI 3.0–4.1%). Chronic hypertension increased (average annual percent change 4.1%, 95% CI 3.3–4.9%) while eclampsia decreased (average annual percent change −2.5%, 95% CI −4.0 to −1.0%). Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are associated with significant morbidity and mortality; the rising incidence is concerning.

Précis:

Nationwide incidence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension increased while the rate of eclampsia nearly halved.

Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, eclampsia and HELLP syndrome, reflect blood pressure elevation during gestation or postpartum. Hypertensive disorders account for 7.4% of pregnancy-related deaths.1–3 As of 2010, U.S. rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension were increasing.4–6 Updated national trends are lacking.7–11 We evaluated national trends in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic hypertension, and eclampsia using vital statistics data.

Methods

This was a repeated cross-sectional analysis of singleton pregnancies delivered >20 weeks’ gestation with birth data in the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) from 1989 to 2020.12,13 The NVSS houses publicly available data from birth certificate standard forms used in all 50 states.12–14 The study timeframe spans use of two – 1989 and 2003 – birth certificate versions. Uptake of the 2003 version was rolling over time with complete adoption in all states by 2016.

The 2003 version defines gestational hypertension – referenced here as ‘hypertensive disorders of pregnancy’ consistent with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists terminology – as an increase in blood pressure in pregnancy inclusive of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP; chronic hypertension as blood pressure elevation prior to pregnancy; and eclampsia as any hypertension with generalized seizures or coma.2,12 The 1989 version definitions are similar and were used for years prior to 2003 form uptake.

Rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic hypertension, and eclampsia were described and compared over time using the National Cancer Institute’s Joinpoint Regression Program with the average annual percentage change (AAPC) with 95% CI reported.15 A sensitivity analysis restricted to deliveries following uptake of the 2003 version by all states (2016–2020) was performed. NVSS does not contain prior pregnancy data. To consider the unmeasured contribution of a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, a second sensitivity analysis restricted to nulliparas was performed. This study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval as all data were deidentified. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. We followed STROBE guidelines.16

Results

Overall there were 122,329,914 deliveries. Of these, 26% delivered by cesarean with 40% nulliparous, 26% obese, and mean maternal age 28 (SD 6) years. The proportion of deliveries with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension increased significantly over the study period (Table 1) with a positive AAPC of 3.6% (95% CI 3.0–4.1%) and 4.1% (95% CI 3.3–4.9%), respectively. Conversely, eclampsia significantly decreased (Figure 1). Limited to 2016–2020, results were similar for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension but trends in eclampsia were no longer significant (AAPC 0%, 95% CI −3.7% to 3.9%). Results did not significantly differ in analysis limited to nulliparas.

Table 1.

Rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic hypertension, and eclampsia among singleton deliveries in the U.S. from 1989 to 2020

| Year | Deliveries* | Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy | Chronic Hypertension | Eclampsia† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | 3581848 | 100079 (2.79) | 25962 (0.72) | 14947 (0.42) |

| 1990 | 3892867 | 102617 (2.64) | 25153 (0.65) | 14680 (0.38) |

| 1991 | 3852535 | 101925 (2.65) | 24887 (0.65) | 13007 (0.34) |

| 1992 | 3848855 | 106327 (2.76) | 25039 (0.65) | 13201 (0.34) |

| 1993 | 3835451 | 110286 (2.88) | 25591 (0.67) | 11975 (0.31) |

| 1994 | 3803882 | 118521 (3.12) | 25669 (0.67) | 12354 (0.32) |

| 1995 | 3756989 | 124006 (3.30) | 24990 (0.67) | 13052 (0.35) |

| 1996 | 3738188 | 129431 (3.46) | 25328 (0.68) | 12472 (0.33) |

| 1997 | 3727695 | 132570 (3.56) | 25310 (0.68) | 11736 (0.31) |

| 1998 | 3773623 | 136933 (3.63) | 26259 (0.70) | 11189 (0.30) |

| 1999 | 3780179 | 139044 (3.68) | 26627 (0.70) | 10947 (0.29) |

| 2000 | 3879627 | 144559 (3.73) | 28911 (0.75) | 11151 (0.29) |

| 2001 | 3866859 | 139583 (3.61) | 30714 (0.79) | 11373 (0.29) |

| 2002 | 3867502 | 139838 (3.62) | 31800 (0.82) | 11549 (0.30) |

| 2003 | 3933500 | 141129 (3.59) | 34247 (0.87) | 10855 (0.28) |

| 2004 | 3955612 | 143384 (3.62) | 37351 (0.94) | 10025 (0.29) |

| 2005 | 3987820 | 152490 (3.82) | 40559 (1.02) | 9665 (0.27) |

| 2006 | 4109509 | 153664 (3.74) | 43556 (1.06) | 9313 (0.26) |

| 2007 | 4150421 | 154338 (3.72) | 44819 (1.08) | 9380 (0.26) |

| 2008 | 4076277 | 153389 (3.76) | 47453 (1.16) | 8961 (0.26) |

| 2009 | 3969408 | 155982 (3.93) | 49159 (1.24) | 9795 (0.30) |

| 2010 | 3845243 | 160738 (4.18) | 51176 (1.33) | 9988 (0.32) |

| 2011 | 3799493 | 160099 (4.21) | 53601 (1.41) | 8357 (0.27) |

| 2012 | 3804224 | 167580 (4.41) | 54842 (1.44) | 8547 (0.27) |

| 2013 | 3786726 | 175008 (4.62) | 57211 (1.51) | 9252 (0.28) |

| 2014 | 3697578 | 182229 (4.93) | 57468 (1.55) | 8770 (0.26) |

| 2015 | 3704866 | 201719 (5.44) | 59532 (1.61) | 8036 (0.23) |

| 2016 | 3806514 | 218936 (5.75) | 64617 (1.70) | 9383 (0.26) |

| 2017 | 3719719 | 231569 (6.23) | 69109 (1.86) | 9750 (0.27) |

| 2018 | 3661875 | 254228 (6.94) | 74311 (2.03) | 8761 (0.25) |

| 2019 | 3620757 | 274010 (7.57) | 78700 (2.17) | 9431 (0.27) |

| 2020 | 3494387 | 287261 (8.22) | 87127 (2.49) | 9242 (0.27) |

Data presented as n(%).

Total number of deliveries higher than the denominator to calculate proportions

Total number of deliveries for eclampsia differs from the number of deliveries for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension due to differential state reporting

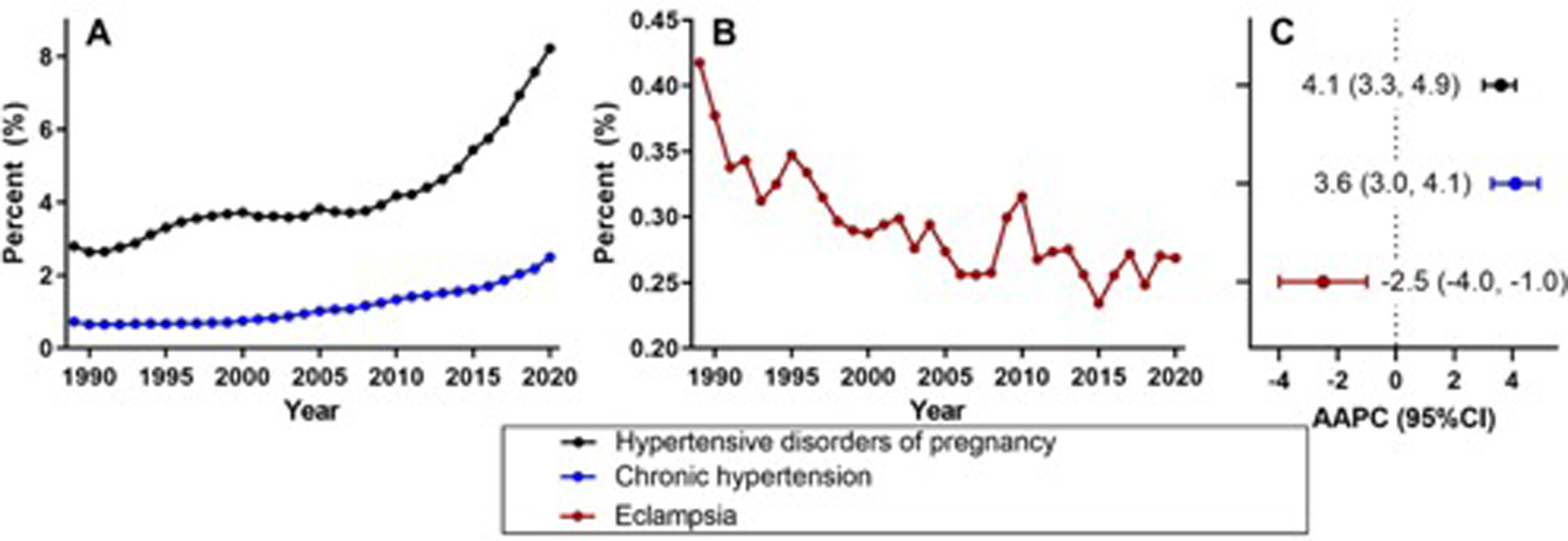

Figure 1.

Trends in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic hypertension, and eclampsia among singleton deliveries in the U.S. from 1989 to 2020

(A) Trends in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension in the U.S. from 1989 to 2020 among singleton deliveries. The figure demonstrates the rate of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension over time. There was a significant 3.6% annual increase in the rate of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (average annual percent change [AAPC] 3.6%, 95% CI 3.0% to 4.1%) and a significant 4.1% annual increase in the rate of chronic hypertension (AAPC 4.1%, 95% CI 3.3% to 4.9%).

(B) Trends in eclampsia in the U.S. from 1989 to 2020 among singleton deliveries. The figure demonstrates the rate of eclampsia over time. There was a significant 2.5% annual decline in the rate of eclampsia (AAPC −2.5%, 95% CI −4.0% to −1.0%).

(C) Average annual percentage change (AAPC) and 95% confidence interval for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic hypertension, and eclampsia from 1989 to 2020 among singleton deliveries.

Discussion

We found the nationwide incidence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension increased over the past three decades while the rate of eclampsia nearly halved.

Previous analyses found an increase in rates of preeclampsia from 3.4% in 1980 to 3.8% in 2010.4 Chronic hypertension similarly increased from 0.12% (1970–1974) to 1.35% (2005–2010), while rates of eclampsia decreased.5,6 Our findings extend this work to include a contemporary timeframe using nationally representative vital statistics.

The NVSS included over 122 million deliveries for analysis providing a robust and representative U.S. sample. Variation in clinical and NVSS definitions over the study period may have affected the identified trends, although trends in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy did not differ significantly in sensitivity analysis limited to 2016–2020. Results were similar in analysis limited to nulliparas. Additional clinical details are unavailable from this data source. It is unknown whether clinical practice changes or population level risk factors altered these rates. Nonetheless, it is concerning that rates of hypertensive disorders continue to increase given the associated maternal morbidity and mortality.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Presentation Information: The 42nd Annual Pregnancy Meeting, Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, Virtual Format, January 31, 2021 – February 5, 2022

References

- 1.Hirshberg A, Srinivas SK. Epidemiology of maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin Perinatol 2017;41(6):332–337. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133(1):1. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000003018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2010;376(9741):631–44. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60279-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980–2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ 2013;347:f6564. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallis AB, Saftlas AF, Hsia J, Atrash HK. Secular trends in the rates of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, United States, 1987–2004. Am J Hypertens 2008;21(5):521–6. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ananth CV, Duzyj CM, Yadava S, Schwebel M, Tita ATN, Joseph KS. Changes in the Prevalence of Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy, United States, 1970 to 2010. Hypertension 2019;74(5):1089–1095. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.119.12968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeFevre ML. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014;161(11):819–26. doi: 10.7326/m14-1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh J, Shelton JA. Increasing prepregnancy body mass index: analysis of trends and contributing variables. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193(6):1994–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SY, Dietz PM, England L, Morrow B, Callaghan WM. Trends in pre-pregnancy obesity in nine states, 1993–2003. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(4):986–93. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodnar LM, Ness RB, Markovic N, Roberts JM. The risk of preeclampsia rises with increasing prepregnancy body mass index. Ann Epidemiol 2005;15(7):475–82. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheen JJ, Huang Y, Andrikopoulou M, Wright JD, Goffman D, D’Alton ME, et al. Maternal Age and Preeclampsia Outcomes during Delivery Hospitalizations. Am J Perinatol 2020;37(1):44–52. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1694794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the National Vital Statistics System. Accessed December 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/about_nvss.htm

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Natality Information. WONDER System. Accessed December 12, 2021. https://wonder.cdc.gov/natality.html

- 14.Ventura SJ. The U.S. National Vital Statistics System: Transitioning Into the 21st Century, 1990–2017. Vital Health Stat 1 2018(62):1–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint trend analysis software. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370(9596):1453–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61602-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]