Abstract

Many studies point to an association between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Although controversial, this association indicates that the presence of the bacterium somehow affects the course of IBD. It appears that H. pylori infection influences IBD through changes in the diversity of the gut microbiota, and hence in local chemical characteristics, and alteration in the pattern of gut immune response. The gut immune response appears to be modulated by H. pylori infection towards a less aggressive inflammatory response and the establishment of a targeted response to tissue repair. Therefore, a T helper 2 (Th2)/macrophage M2 response is stimulated, while the Th1/macrophage M1 response is suppressed. The immunomodulation appears to be associated with intrinsic factors of the bacteria, such as virulence factors - such oncogenic protein cytotoxin-associated antigen A, proteins such H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein, but also with microenvironmental changes that favor permanence of H. pylori in the stomach. These changes include the increase of gastric mucosal pH by urease activity, and suppression of the stomach immune response promoted by evasion mechanisms of the bacterium. Furthermore, there is a causal relationship between H. pylori infection and components of the innate immunity such as the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome that directs IBD toward a better prognosis.

Keywords: Cytotoxin-associated antigen A oncoprotein, Gut microbiota, Helicobacter pylori, Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein, Immunological modulation, Inflammatory bowel disease, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome

Core Tip: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection seems to modulate the immune response triggered by inflammatory bowel disease in a way that makes it less aggressive. The virulence factors of H. pylori, as well as the mechanisms that allow it to remain in the stomach environment, appear to change the intestinal microenvironment and modulate the local immune response, contributing to a disease with milder symptoms and less tissue damage.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are a group of chronic conditions affecting the gastrointestinal tract, characterized by episodes of abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stools, and weight loss. The two main types of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)[1]. In CD any area of the gastrointestinal tract can be affected, but the most affected regions are the terminal ileum, the cecum, the perianal region, and the colon, while in UC the inflammation is restricted to the colon and rectum[1]. Regarding histology, in CD the intestine presents thickened submucosa, transmural inflammation, ulceration and non-caseating granulomas, while in UC the inflammation is limited to the mucosa, with crypts and abscesses[2].

The pathogenesis of IBD is complex and involves a combination of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors. The gut microbiota is critical to homeostasis in this organ and contributes to the tolerance process, to the development and differentiation of the local and systemic immune system, and may protect the host from pathogenic enteric infections. However, in IBD, luminal bacteria trigger deregulated immune responses, acting as the main environmental factor for the development of these pathologies[3,4].

The loss of tolerance to the commensal microbiota seems to be related to the genetic susceptibility of the individual and to an imbalance in the composition of the microbiota[5]. IBD patients have changes in stool composition, with less bacterial quantity and diversity[6,7].

Genome wide association studies of IBD have identified 99 non-overlapping genetic risk loci including 28 that are shared between CD and UC[8]. These genetic alterations seem to implicate several important pathways, such as intestinal barrier function, regulation of innate and adaptive immunity, reactive oxygen species formation, autophagy, and endoplasmic reticulum stress[9]; associations were identified between polymorphisms in the genes for interleukin (IL)-10, IL-10 receptor alpha, and components of this signaling pathway - signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, tyrosine kinase 2, and JAK2, with the early development of IBD[10].

Dysregulation of the immune component in IBD is marked by abnormal mucus production, failure to repair the epithelial barrier, and excessive and persistent activation of T lymphocytes, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and natural killer cells[11,12].

Naive TCD4+ cells can differentiate into T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, Th9, Th17 and regulatory T (Treg) subpopulations; the main stimulus for differentiation into Th1 cells - secreting interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-2, is the expression of IL-12, while IL-4 leads to differentiation into Th2 cells, whose cytokine pattern is marked by the expression of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and IL-25[13]. Classically, CD and UC are described as diseases with a Th1 and Th2 immune pattern, respectively[14-16], since typically CD patients have higher IFN-γ and IL-2 expression than UC patients[17,18], that express more IL-5 and IL-13[19,20]. However, some studies contradict this information, since lower levels of IL-13 were seen in UC patients compared to CD patients[21], and high levels of IFN-γ were found in carriers of both diseases[22]. In line with this, Bernardo et al[23] found a mixed cytokine pattern in biopsies from UC patients, associated with low IL-13 levels.

A Th17 pattern response prevails in the gut. The differentiation into Th17 cells leads to the expression of IL-17, IL- 21, IL- 22, and IL-23, which are found in large quantities in the intestine of IBD patients[24]. A study using IL-17 receptor (IL-17R) knockout mice showed that IL-17R deficiency protected the animals from developing trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis[25-27].

Although not conclusive, there is evidence to indicate that two members of this cytokine family have different effects; IL-17A appears to have a protective effect through inhibition of the Th1 response[28], furthermore, other studies indicate that deficiency of this cytokine causes exacerbation of colitis, while IL-17F contributes to and aggravates the inflammatory process[29]. Despite the prevalence of Th17 cells in the gut in the absence of IBD, this response pattern appears to be exacerbated with disease onset leading to increased production of pattern marker cytokines. Perhaps this increase occurs relatively disproportionately, prioritizing the increase in cytokines that induce an inflammatory response, such as IL-17F.

Treg cells which is characterized by constitutive expression of forkhead/winged helix transcriptional factor P3 (FoxP3), CD25 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4, play a major role in the pathogenesis of IBD[30]. In these diseases, there is a significant dysfunction in the activity of these cells, either by being in low numbers or by having their function suppressed. It has been observed that effector cells from IBD patients exhibit relative resistance to Treg-mediated suppression by expressing high levels of Smad7, an inhibitor of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway[31,32]. The unbalanced and uncontrolled local immune response against the bacterial microbiota in the IBD occurs when it is poorly controlled by endogenous counter regulatory mechanisms, such as the immunosuppressive cytokine TGF-β. Studies show that the inefficiency in control occurs due to a blockade of TGF-β signaling, caused by a blockade in the phosphorylation of the signaling molecule associated with the TGF-β activated receptor, Smad3. The blockade of Smad3 activity is caused by the upregulation of the Smad7[33].

Individuals with a mutation in the FOXP3 gene often suffer from intestinal inflammation[34]. Treg cells are able to convert to Th17 cells under inflammatory conditions, and the cytokine IL-1β is key in this process[35]. The balance between the Th17 and Treg response is important, especially in places such as the gut, where there is a commensal microbiota, to prevent deregulated immune responses. IBD patients have a reduced Treg/Th17 ratio in peripheral blood compared to healthy individuals. The installation of the inflammatory process in IBD seems to be fueled by an unbalanced increase in the production of Th17 cytokines, which promote the Th1 pattern. Pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by Th1 cells, such as IL-1β, potentiate the inflammatory process by decreasing the Treg/Th17 ratio, both by proportionally increasing the Th17 response and by reducing the suppression of the inflammatory response by Treg cells. Regarding Th9 cells - capable of exacerbating inflammatory processes by increasing epithelial permeability[36], are at high levels in CD and UC[37,38].

IMMUNOMODULATION OF THE INFLAMMATORY PROCESS AND PATHOGENESIS OF IBD BY HELICOBACTER PYLORI

Influence of Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated antigen A+ infection on IBD prognosis

Cytotoxin-associated antigen A (CagA) is a gene found in the final portion of the Cag pathogenicity island of the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) genome and encodes the oncogenic protein CagA. Its presence is more frequent in East Asian populations than in those from the West, and determines a number of interactions between the bacterium and the host[39]. Although there is a causal relationship between H. pylori CagA+ and the incidence of cancers of the gastrointestinal tract[39,40], when it comes to IBD, especially CD and UC, the presence of the CagA gene may positively influence the prognosis of patients[41].

In a first analysis, age, genetic and environmental factors associated with innate and adaptive immunity are key factors in the development of IBD[42,43], thus the presence of H. pylori infection becomes yet another variable. Some studies point to several hypotheses for the improved prognosis of IBD in the presence of the H. pylori CagA gene, such as the conversion of the M1 macrophage lineage into M2 through modulation of the Th17/Treg immune response, in which there is a decrease in the levels of IL-17F and IL-21 with concomitant increase in the expression of IL-10 and Treg cells[44] due to increased plasma IL-13[45].

Also contributing to the process are increased anti-inflammatory responses through increased expression of CD163 and IL-10, suppression of toll like receptors (TLR) mediated signaling pathways[46], and control of the immune response through activation of pathways mediated by the basic leucine zipper transcription factor ATF-like 2 (BATF2)[47-49] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated antigen A+ on favorable prognosis of inflammatory bowel diseases. The presence of the cytotoxin-associated antigen A gene at the Cag pathogenicity island induces the modulation of T helper 17/Treg immunological response (1), which reduces levels of interleukin (IL)-17F, IL-17A, and IL-21 and increases the expression of IL-13, IL-10, and Treg (2). These two factors are synergists in the conversion process of the M1 to M2 macrophage lineage (3). Then, M2 macrophages suppress signaling mediated by toll-like receptors (4) and activate metabolic pathways mediated by basic leucine zipper transcription factor ATF-like 2, increasing CD163, a macrophage/monocyte scavenger receptor (5). Finally, the levels of IL-10 expression also increase (6), leading to anti-inflammatory effects (7) and, therefore, to a better prognosis on inflammatory bowel diseases. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; IL: Interleukin; TLR: Toll-like receptor; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; CagA: Cytotoxin-associated antigen A; Treg: Regulatory T.

The CD163 is a macrophage/monocyte scavenger receptor whose expression is positively regulated by IL-10. The upregulated expression of this receptor is one of the most marked changes in the M2/M1 phenotype switch; therefore, high expression of CD163 is characteristic in inflammatory processes[50,51]. According to studies, the number of CD163- M1 monocytes, as well as CD163+ and CD163+/IL-10+ M2 monocytes are significantly increased in individuals infected with H. pylori, in addition to having higher levels of IL-10. IL-10 production is significantly higher by M2 cells from individuals with H. pylori infection. In addition, individuals infected with CagA-positive H. pylori strains had a significantly higher number of CD163+ and CD163+/IL-10+ monocytes compared to those infected with CagA-negative strains[52].

The TLRs are expressed by cells of the intestinal epithelium, and by cells of the immune system present in the gut, such as leukocytes, dendritic cells, and various polymorphisms of these receptors have been associated with susceptibility to IBD[53,54] and they are involved in signaling pathways leading to the expression of several inflammatory genes[55,56]. BATF2 has unique functions in the regulation of cytokine gene expression by TLR signaling in macrophages[57].

H. pylori has metabolic adaptations for gastric colonization that, in the background, participate in modulating the inflammatory process of IBD. The urease enzyme that confers H. pylori resistance to stomach acidity, participates in immunomodulation as it alters particle opsonization, facilitates apoptosis, and by being presented by MHC II increases the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines[58].

The flagella of H. pylori, besides the fundamental importance in its motility for gastric colonization, also induces an inflammatory response. FlaA and FlaB flagellins can promote a humoral response by stimulating the production of specific antibodies[59,60]. Furthermore, studies report that bacteria with increased motility increase IL-8 release and suggest that genes which regulate flagellin production may alter adhesin expression[61-63] facilitating colonization. The chemoattractant effect of IL-8 is all too well known, however, data on the association of IL-8 with H. pylori infection are still scarce[64].

Superoxide dismutase from H. pylori has also been shown to have a potential immune suppressive effect by inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, through inhibition of pathways activated by the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-кB), as well as macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α[65].

Modification of bacterial gut microbiota by H. pylori

The alteration in the pattern of gastric secretion by H. pylori is closely related to the modification of the microbiota of the gastrointestinal tract[66]. Hypochlorhydria enables colonization of the distal intestine by acidic pH-sensitive bacteria; this causes people infected with H. pylori to have a more diverse alpha intestinal microbiota compared to uninfected people[66-68]. These changes reflect higher percentages of acidophilic bacteria, proteobacteria, bacteria of the genera Lactobacillus, Haemophilus, Streptococcus and Gemella; in contrast, there is a decrease in the percentage of pathogenic anaerobic bacteria such as Clostridium[69-72].

In addition to the variation in intestinal pH being one of the factors that alter the diversity of the gut bacterial microbiota, it can also be influenced by the virulence factors CagA and VacA of H. pylori, which alter the immune response of the infected individual[73-75]. Hormonal factors, influenced by H. pylori infection such as an increase of gastrin secretion alter gut metabolism, in addition, leptin has been directly related to an increase of the amount of the probiotic bacteria Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus[76].

Indeed, there is an altered composition of the local microbiota of IBD patients[77]. In these diseases an exacerbated immune response against the commensal microbiota occurs in genetically predisposed individuals and, studies suggest that the balance between pathogenic and beneficial bacterial species is altered in these ones[78]. Therefore, the dysbiosis promoted by H. pylori infection may help explain the inverse relationship between bacterial infection and IBD in individuals with the two conditions concomitantly, although the underlying molecular mechanisms are not fully understood[79].

CO-IMMUNOMODULATION OF IBD BY NLR FAMILY PYRIN DOMAIN CONTAINING 3 INFLAMMASOME AND H. PYLORI INFECTION

The NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is a multiprotein complex that plays a crucial role in the innate immune response. The complex is formed by the NLRP3 receptor, the adaptor protein caspase-recruitment domain (ASC) and the enzyme caspase-1 and, appears to play a role in the negative association between IBD and H. pylori infection by the IL-1β and IL-18 activity. NLRP3 recognizes a wide variety of stimuli linked to pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns through pattern recognition receptors such as TLRs and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2. Activation of NLRP3 includes a priming process which components are expressed in greater quantities and depends on several upstream signals such as potassium and chloride efflux, calcium mobilization, lysosomal disruption, and mitochondrial dysfunction with increased reactive oxygen species[80].

Activation of the inflammasome culminates i4n expression of NF-кB and cleavage/activation of caspase-1, responsible for processing pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, which are cleaved into their active forms[81,82]. Furthermore, activation of NLRP3 leads to proptosis, a form of programmed cell death mediated by gasdermin D protein. Caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin D, removing its carboxy-terminal portion, which allows its insertion and polymerization into the plasma membrane forming pores. Proptosis also appears to induce the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18[83].

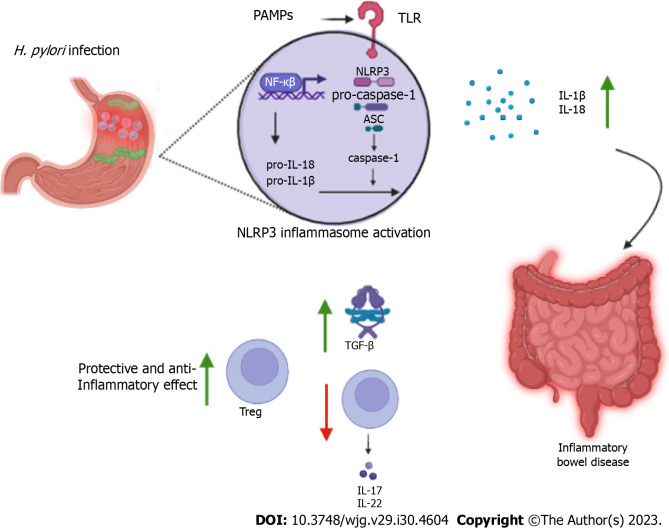

Caspase-1 is highly expressed in the mucosa of the patients infected with H. pylori. However, it is observed that together, IL-1β and IL-18 seem to play different roles in controlling the infection and the pathogenicity of the bacterium. While IL-1β presents itself as a potent pro-inflammatory agent, IL-18 has regulatory properties and controls responses mediated by TCD4+ cells. Studies have shown that mice that failed to process IL-18 in the absence of caspase-1 had less bacterial colonization, more robust Th17 responses, and more evident immune pathogenicity compared to control animals[84]. Furthermore, mesenchymal stem cells stimulated by this cytokine promote differentiation of Treg cells into virgin TCD4+ cells, limiting the Th17 response[85], promoting a tolerogenic activity and adjusting chronic inflammation in the gastric mucosa (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Immunomodulation of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome and protection against inflammatory bowel diseases. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns from Helicobacter pylori are recognized by the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome toll-like receptors leading to responses that appear to be associated with improved prognosis and an anti-inflammatory effect. Activated NLRP3 is able to increase the expression of caspase-1 which activates the cytokines interleukin (IL)-18 and IL-1β. The positive regulation of these cytokines leads to extragastric immunomodulation by suppressing the T helper 17 subpopulation and increasing regulatory T, transforming growth factor-β and mucins. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; IL: Interleukin; PAMPs: Pathogen-associated molecular patterns; TLR: Toll-like receptor; TGF: Transforming growth factor; NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; Treg: Regulatory T.

The absence of caspase-1 results in an inefficient protective immune response, with a less pronounced Th1 and Th17 pattern[86,87]. There is strong evidence of an association between IL-18 and the prevention and control of allergic diseases such as asthma and rhinitis, through pulmonary infiltration of large amounts of Treg and tolerogenic dendritic cells. This association seems especially beneficial in relation to infection with H. pylori CagA+ strains, as observed in a study wherein mice infected with the bacteria in the neonatal period developed specific immunological tolerance and protection against gastric immunopathology resulting from H. pylori CagA+ infection[88].

Studies with animal models have shown that NLRP3 activation induced by H. pylori infection appears to improve the prognosis of IBD. Engler et al[89] observed that mice exposed to the bacterium developed less severe forms of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis, with significantly milder inflammation and epithelial changes. These positive effects were also observed in animals treated with H. pylori extracts. Such beneficial effects are accompanied by positive regulation of TGF-β and the transcription factor caudal-related homeobox transcription factor 2, which regulates the expression of mucins such as mucin 2, a fact that was associated with signaling by NLRP3 and IL-18 production by caspase-1.

Zaki et al[90] demonstrated that NLRP3 -/- or ASC -/- mice are more susceptible to DSS-induced colitis and caspase-1 -/- mice are more susceptible to weight loss, diarrhea, rectal bleeding and mortality during the chronic and acute phases of DSS- or TNBS-induced colitis. These findings are related to IL-18 production and its mucosal barrier repair function. Furthermore, IL-18 -/- and IL-18R -/- mice exhibit greater susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis, associated with higher mortality and more severe histopathological changes[91]. Previous studies have reported that the absence of the adaptor protein myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), which is involved in the production of IL-18 and IL-1β, increases the severity of inflammatory disease, indicating the importance of MyD88-dependent signaling pathways, such as the TLR4-MyD88 pathway, in blocking the onset and progression of IBD[92-94]. MyD88 is the main signaling adaptor protein of the TLR family. Studies using MyD88-deficient mice suggest a dominant role for TLR/MyD88 signal transduction in preventing intestinal inflammation after acute epithelial injury by promoting epithelial repair[94,95].

Yao et al[96] conducted a study with NLRP3R258W mutant mice, a mutation homologous to NLRP3R260W in humans, which causes increased inflammasome activity. The mutant mice developed DSS-induced colitis with milder symptoms compared to wild-type animals, in addition to lower expression of inflammatory mediators, higher expression of IL-18 and IL-1β, and fewer colon tumors. These positive effects were associated with higher activity of Treg cells, positively regulated by IL-1β and fundamental in controlling inflammation. In this study no evidence was found that directly points to IL-18 as an effector molecule in the activation of the inflammasome, but it is believed that this cytokine may be indirectly affected by NLRP3 through secondary effects. However, IL-18 deficiency was shown to override the protective effect of the NLRP3R258W mutation.

IMMUNOMODULATION OF IBD BY NEUTROPHIL-ACTIVATING PROTEIN OF H. PYLORI

H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) is a virulence factor that plays an important role in immunomodulation. HP-NAP refers to H. pylori mini-ferritin, a protein with the ability to activate the production of oxygen radicals by neutrophils promoting their adhesion to the vascular endothelium[97]. Neutrophil adhesion occurs by the positive regulation of β-2-integrin (CD18) expression in a high-affinity state[98,99].

The mini-ferritins have the ability to influence host immune cells in addition to protecting bacterial DNA from oxidizing radicals[100]. HP-NAP is released by H. pylori near the gastric epithelial monolayer, thus activating macrophages/monocytes and mast cells, with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12 and IL-23[101,102]. Similar to the chemokine CXCL8, HP-NAP directly promotes leukocyte recruitment; after HP-NAP transcytosis by endothelial cells, part of these proteins remain bound to the luminal portion of the endothelium, increasing the expression of β-2-integrin and changing the local spatial conformation, a fact that culminates in the extravasation of immune cells[99,103].

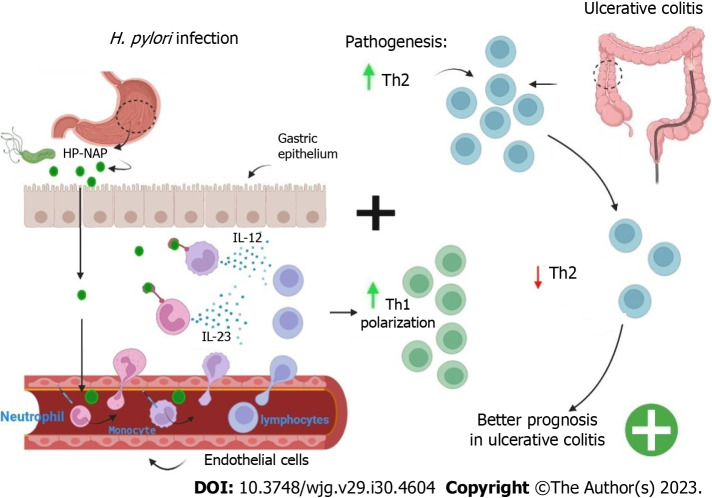

The IL-8 secretion by neutrophils present at the site of inflammation enables the recruitment of more neutrophils and other immune cells. IL-8 secretion is promoted by HP-NAP and mediated through interactions with TLR2 receptors and pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins[104]. HP-NAP also induces mast cells and basophils to secrete TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12 and IL-23, and stimulates mast cells to release histamine and IL-6[101,102,105]. Besides influencing innate immunity, HP-NAP modulates adaptive immunity by promoting the release of IL-12 and IL-23 by neutrophils and monocytes, thereby causing a Th1 polarization, and directing the maturation of monocytes to mature dendritic cells[102].

The mature dendritic cells are stimulated by HP-NAP to express MHCII and release Th1 pattern cytokines such as IL-12[102,106]. The increased secretion of IL-12 in the gastrointestinal microenvironment, promoted by HP-NAP, causes gastric specific T lymphocyte subpopulations to be able to produce large amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α and, to exhibit cytotoxic activity[102]. Increased Th1 pattern and cytotoxic response, induced by H. pylori infection, may be beneficial in pathologies which the Th2 response is the detrimental mechanism (Figure 3). The ability of HP-NAP to reduce Th2 activity due to the polarization towards Th1 was proven in experiments using mice with atopic dermatitis[107]. Therefore, HP-NAP may have a therapeutic effect in situations which there is a predominance of Th2 response, as was observed in HP-NAP inoculation assays in mice with allergic asthma, which significantly reduced serum immunoglobulin E levels with concomitant increase in IL-2, thus decreasing eosinophil infiltration[108].

Figure 3.

Hypothesis on correlation between concomitant infection with Helicobacter pylori and the presence of ulcerative colitis (inflammatory bowel disease), which has a pathological pattern of exacerbated T helper 2 response. The schematic shows HP-NAP being secreted into the gastric mucosa by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). Then, HP-NAP undergoes a process of transcytosis by endothelial cells, binding to the luminal side of the blood vessel. With this, there is an alteration in the expression of β-2-integrin, with the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes, which carry out diapedesis. The recruited leukocytes secrete cytokines [interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23], which promote a polarization of the circulating lymphocytes to a T helper 1 (Th1) pattern. The Th1 polarization causes a reduction in the Th2 response, this could explain the improvement of ulcerative colitis symptoms in patients infected with H. pylori. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; IL: Interleukin; Th: T helper; HP-NAP: Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein.

Thus, the Th1-directed polarization promoted by HP-NAP, may be a possible explanation for the improvement of IBD symptoms, whose pathogenesis may be the result of a dysregulated Th2 response, as occurs in UC, in which there is a predominance of a Th2 response and inhibition of the Th1 response, in individuals infected with H. pylori[109-112].

CONCLUSION

Although significant progress has been made over the last few years in defining the mechanisms that H. pylori use to influence on IBD evolution, there is clearly much that remains to be elucidated and many questions persist. In this review we emphasize the role of H. pylori CagA+ and HP-NAP on favorable prognosis of IBD. The pathogenesis of IBD is complex and involves a combination of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors. Classically, CD and UC are described as diseases with a Th1 and Th2 immune pattern, but the prevalence of type response remains under study.

Regarding the cellular pattern, Th17 cells have been demonstrated at the site of inflammation, but the levels of total cytokine markers of these patterns remain variable on models’ diversity. Treg cells play a major role in the pathogenesis of IBD by suppression of Smad3 and consequently overexpression Smad7, an inhibitor of the TGF-β signaling pathway. Moreover, Th9 cells - capable of exacerbating inflammatory processes by increasing epithelial permeability, are at high levels in CD and UC.

In summary, targeting NLRP3 inflammasome by H. pylori infection allows the exacerbation of IL-1β and IL-18 that culminates in high levels of TGF-β and low levels of IL-17 and IL-22 on IBD. The patients with CagA gene can induce the Treg cells which contributes to the polarization of the M1 macrophage into M2 macrophage lineage through concomitant increase of the expression of IL-10 and more Treg cells. At the same time, HP-NAP has an important role in immunomodulation by reactive oxygen species production neutrophil-induced. The ability of HP-NAP to reduce Th2 activity due to the polarization towards Th1 response may be a possible explanation for the improvement of IBD symptoms, in which there is a predominance of a Th2 response and inhibition of the Th1 response like occurs in individuals infected with H. pylori.

Regarding the capacity of CagA+ and HP-NAP to control inflammation and autoimmunity, and their implication in preventing IBD evolution, it seems probable that a clear understanding of how CagA+ and HP-NAP work on Treg cells, cytokines and macrophages-induced will present definitive opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: April 28, 2023

First decision: June 17, 2023

Article in press: July 24, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: B Lankarani K, Iran; Bernal G, Chile; Wang D, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

Contributor Information

Gabriella Feilstrecker Balani, Campus Toledo, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Toledo 85.919-899, Paraná, Brazil.

Mariana dos Santos Cortez, Campus Toledo, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Toledo 85.919-899, Paraná, Brazil.

Jayme Euclydes Picasky da Silveira Freitas, Campus Toledo, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Toledo 85.919-899, Paraná, Brazil.

Fabrício Freire de Melo, Campus Anísio Teixeira, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Vitória da Conquista 45.029-094, Bahia, Brazil.

Ana Carla Zarpelon-Schutz, Campus Toledo, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Toledo 85.919-899, Paraná, Brazil; Programa de Pós-graduação em Biotecnologia - Setor Palotina, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Palotina 85.950-000, Paraná, Brazil.

Kádima Nayara Teixeira, Campus Toledo, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Toledo 85.919-899, Paraná, Brazil; Programa Multicêntrico de Pós-graduação em Bioquímica e Biologia Molecular - Setor Palotina, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Palotina 85.950-000, Paraná, Brazil. kadimateixeira@ufpr.br.

References

- 1.Flynn S, Eisenstein S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Presentation and Diagnosis. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99:1051–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641–1657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nell S, Suerbaum S, Josenhans C. The impact of the microbiota on the pathogenesis of IBD: lessons from mouse infection models. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:564–577. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saleh M, Elson CO. Experimental inflammatory bowel disease: insights into the host-microbiota dialog. Immunity. 2011;34:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strober W, Fuss I, Mannon P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:514–521. doi: 10.1172/JCI30587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13780–13785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott SJ, Musfeldt M, Wenderoth DF, Hampe J, Brant O, Fölsch UR, Timmis KN, Schreiber S. Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:685–693. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.025403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson CA, Boucher G, Lees CW, Franke A, D'Amato M, Taylor KD, Lee JC, Goyette P, Imielinski M, Latiano A, Lagacé C, Scott R, Amininejad L, Bumpstead S, Baidoo L, Baldassano RN, Barclay M, Bayless TM, Brand S, Büning C, Colombel JF, Denson LA, De Vos M, Dubinsky M, Edwards C, Ellinghaus D, Fehrmann RS, Floyd JA, Florin T, Franchimont D, Franke L, Georges M, Glas J, Glazer NL, Guthery SL, Haritunians T, Hayward NK, Hugot JP, Jobin G, Laukens D, Lawrance I, Lémann M, Levine A, Libioulle C, Louis E, McGovern DP, Milla M, Montgomery GW, Morley KI, Mowat C, Ng A, Newman W, Ophoff RA, Papi L, Palmieri O, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Panés J, Phillips A, Prescott NJ, Proctor DD, Roberts R, Russell R, Rutgeerts P, Sanderson J, Sans M, Schumm P, Seibold F, Sharma Y, Simms LA, Seielstad M, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, van den Berg LH, Vatn M, Verspaget H, Walters T, Wijmenga C, Wilson DC, Westra HJ, Xavier RJ, Zhao ZZ, Ponsioen CY, Andersen V, Torkvist L, Gazouli M, Anagnou NP, Karlsen TH, Kupcinskas L, Sventoraityte J, Mansfield JC, Kugathasan S, Silverberg MS, Halfvarson J, Rotter JI, Mathew CG, Griffiths AM, Gearry R, Ahmad T, Brant SR, Chamaillard M, Satsangi J, Cho JH, Schreiber S, Daly MJ, Barrett JC, Parkes M, Annese V, Hakonarson H, Radford-Smith G, Duerr RH, Vermeire S, Weersma RK, Rioux JD. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nat Genet. 2011;43:246–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, Wang K, Radford-Smith GL, Ahmad T, Lees CW, Balschun T, Lee J, Roberts R, Anderson CA, Bis JC, Bumpstead S, Ellinghaus D, Festen EM, Georges M, Green T, Haritunians T, Jostins L, Latiano A, Mathew CG, Montgomery GW, Prescott NJ, Raychaudhuri S, Rotter JI, Schumm P, Sharma Y, Simms LA, Taylor KD, Whiteman D, Wijmenga C, Baldassano RN, Barclay M, Bayless TM, Brand S, Büning C, Cohen A, Colombel JF, Cottone M, Stronati L, Denson T, De Vos M, D'Inca R, Dubinsky M, Edwards C, Florin T, Franchimont D, Gearry R, Glas J, Van Gossum A, Guthery SL, Halfvarson J, Verspaget HW, Hugot JP, Karban A, Laukens D, Lawrance I, Lemann M, Levine A, Libioulle C, Louis E, Mowat C, Newman W, Panés J, Phillips A, Proctor DD, Regueiro M, Russell R, Rutgeerts P, Sanderson J, Sans M, Seibold F, Steinhart AH, Stokkers PC, Torkvist L, Kullak-Ublick G, Wilson D, Walters T, Targan SR, Brant SR, Rioux JD, D'Amato M, Weersma RK, Kugathasan S, Griffiths AM, Mansfield JC, Vermeire S, Duerr RH, Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Schreiber S, Cho JH, Annese V, Hakonarson H, Daly MJ, Parkes M. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, Gertz EM, Schäffer AA, Noyan F, Perro M, Diestelhorst J, Allroth A, Murugan D, Hätscher N, Pfeifer D, Sykora KW, Sauer M, Kreipe H, Lacher M, Nustede R, Woellner C, Baumann U, Salzer U, Koletzko S, Shah N, Segal AW, Sauerbrey A, Buderus S, Snapper SB, Grimbacher B, Klein C. Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2033–2045. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korzenik JR, Podolsky DK. Evolving knowledge and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:197–209. doi: 10.1038/nrd1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choy MC, Visvanathan K, De Cruz P. An Overview of the Innate and Adaptive Immune System in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:2–13. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahluwalia B, Moraes L, Magnusson MK, Öhman L. Immunopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and mechanisms of biological therapies. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:379–389. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1447597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih DQ, Targan SR, McGovern D. Recent advances in IBD pathogenesis: genetics and immunobiology. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:568–575. doi: 10.1007/s11894-008-0104-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Sabatino A, Biancheri P, Rovedatti L, MacDonald TT, Corazza GR. New pathogenic paradigms in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:368–371. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strober W, Fuss IJ. Proinflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1756–1767. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breese E, Braegger CP, Corrigan CJ, Walker-Smith JA, MacDonald TT. Interleukin-2- and interferon-gamma-secreting T cells in normal and diseased human intestinal mucosa. Immunology. 1993;78:127–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noguchi M, Hiwatashi N, Liu Z, Toyota T. Enhanced interferon-gamma production and B7-2 expression in isolated intestinal mononuclear cells from patients with Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30 Suppl 8:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuss IJ, Neurath M, Boirivant M, Klein JS, de la Motte C, Strong SA, Fiocchi C, Strober W. Disparate CD4+ lamina propria (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn's disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-gamma, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J Immunol. 1996;157:1261–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heller F, Florian P, Bojarski C, Richter J, Christ M, Hillenbrand B, Mankertz J, Gitter AH, Bürgel N, Fromm M, Zeitz M, Fuss I, Strober W, Schulzke JD. Interleukin-13 is the key effector Th2 cytokine in ulcerative colitis that affects epithelial tight junctions, apoptosis, and cell restitution. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:550–564. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vainer B, Nielsen OH, Hendel J, Horn T, Kirman I. Colonic expression and synthesis of interleukin 13 and interleukin 15 in inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine. 2000;12:1531–1536. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rovedatti L, Kudo T, Biancheri P, Sarra M, Knowles CH, Rampton DS, Corazza GR, Monteleone G, Di Sabatino A, Macdonald TT. Differential regulation of interleukin 17 and interferon gamma production in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2009;58:1629–1636. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.182170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernardo D, Vallejo-Díez S, Mann ER, Al-Hassi HO, Martínez-Abad B, Montalvillo E, Tee CT, Murugananthan AU, Núñez H, Peake ST, Hart AL, Fernández-Salazar L, Garrote JA, Arranz E, Knight SC. IL-6 promotes immune responses in human ulcerative colitis and induces a skin-homing phenotype in the dendritic cells and Tcells they stimulate. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1337–1353. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujino S, Andoh A, Bamba S, Ogawa A, Hata K, Araki Y, Bamba T, Fujiyama Y. Increased expression of interleukin 17 in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2003;52:65–70. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z, Zheng M, Bindas J, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls JK. Critical role of IL-17 receptor signaling in acute TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:382–388. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000218764.06959.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gálvez J. Role of Th17 Cells in the Pathogenesis of Human IBD. ISRN Inflamm. 2014;2014:928461. doi: 10.1155/2014/928461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pène J, Chevalier S, Preisser L, Vénéreau E, Guilleux MH, Ghannam S, Molès JP, Danger Y, Ravon E, Lesaux S, Yssel H, Gascan H. Chronically inflamed human tissues are infiltrated by highly differentiated Th17 lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:7423–7430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Connor W Jr, Kamanaka M, Booth CJ, Town T, Nakae S, Iwakura Y, Kolls JK, Flavell RA. A protective function for interleukin 17A in T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:603–609. doi: 10.1038/ni.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Awasthi A, Kuchroo VK. IL-17A directly inhibits TH1 cells and thereby suppresses development of intestinal inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:568–570. doi: 10.1038/ni0609-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardenberg G, Steiner TS, Levings MK. Environmental influences on T regulatory cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giuffrida P, Di Sabatino A. Targeting T cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:105040. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fantini MC, Rizzo A, Fina D, Caruso R, Sarra M, Stolfi C, Becker C, Macdonald TT, Pallone F, Neurath MF, Monteleone G. Smad7 controls resistance of colitogenic T cells to regulatory T cell-mediated suppression. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1308–1316.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monteleone G, Boirivant M, Pallone F, MacDonald TT. TGF-beta1 and Smad7 in the regulation of IBD. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1 Suppl 1:S50–S53. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gambineri E, Perroni L, Passerini L, Bianchi L, Doglioni C, Meschi F, Bonfanti R, Sznajer Y, Tommasini A, Lawitschka A, Junker A, Dunstheimer D, Heidemann PH, Cazzola G, Cipolli M, Friedrich W, Janic D, Azzi N, Richmond E, Vignola S, Barabino A, Chiumello G, Azzari C, Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R. Clinical and molecular profile of a new series of patients with immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome: inconsistent correlation between forkhead box protein 3 expression and disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1105–1112.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koenen HJ, Smeets RL, Vink PM, van Rijssen E, Boots AM, Joosten I. Human CD25highFoxp3pos regulatory T cells differentiate into IL-17-producing cells. Blood. 2008;112:2340–2352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerlach K, McKenzie AN, Neurath MF, Weigmann B. IL-9 regulates intestinal barrier function in experimental T cell-mediated colitis. Tissue Barriers. 2015;3:e983777. doi: 10.4161/21688370.2014.983777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerlach K, Hwang Y, Nikolaev A, Atreya R, Dornhoff H, Steiner S, Lehr HA, Wirtz S, Vieth M, Waisman A, Rosenbauer F, McKenzie AN, Weigmann B, Neurath MF. TH9 cells that express the transcription factor PU.1 drive T cell-mediated colitis via IL-9 receptor signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:676–686. doi: 10.1038/ni.2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weigmann B, Neurath MF. Th9 cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0603-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatakeyama M. Structure and function of Helicobacter pylori CagA, the first-identified bacterial protein involved in human cancer. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2017;93:196–219. doi: 10.2183/pjab.93.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu AH, Crabtree JE, Bernstein L, Hawtin P, Cockburn M, Tseng CC, Forman D. Role of Helicobacter pylori CagA+ strains and risk of adenocarcinoma of the stomach and esophagus. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:815–821. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tepler A, Narula N, Peek RM Jr, Patel A, Edelson C, Colombel JF, Shah SC. Systematic review with meta-analysis: association between Helicobacter pylori CagA seropositivity and odds of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:121–131. doi: 10.1111/apt.15306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:91–99. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan I, Ullah N, Zha L, Bai Y, Khan A, Zhao T, Che T, Zhang C. Alteration of Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Cause or Consequence? IBD Treatment Targeting the Gut Microbiome. Pathogens. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/pathogens8030126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H, Dai Y, Liu Y, Wu T, Li J, Wang X, Wang W. Helicobacter pylori Colonization Protects Against Chronic Experimental Colitis by Regulating Th17/Treg Balance. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1481–1492. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marotti B, Rocco A, De Colibus P, Compare D, de Nucci G, Staibano S, Tatangelo F, Romano M, Nardone G. Interleukin-13 mucosal production in Helicobacter pylori-related gastric diseases. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michalkiewicz J, Helmin-Basa A, Grzywa R, Czerwionka-Szaflarska M, Szaflarska-Poplawska A, Mierzwa G, Marszalek A, Bodnar M, Nowak M, Dzierzanowska-Fangrat K. Innate immunity components and cytokines in gastric mucosa in children with Helicobacter pylori infection. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:176726. doi: 10.1155/2015/176726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guler R, Roy S, Suzuki H, Brombacher F. Targeting Batf2 for infectious diseases and cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26575–26582. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy TL, Tussiwand R, Murphy KM. Specificity through cooperation: BATF-IRF interactions control immune-regulatory networks. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nri3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roy S, Guler R, Parihar SP, Schmeier S, Kaczkowski B, Nishimura H, Shin JW, Negishi Y, Ozturk M, Hurdayal R, Kubosaki A, Kimura Y, de Hoon MJ, Hayashizaki Y, Brombacher F, Suzuki H. Batf2/Irf1 induces inflammatory responses in classically activated macrophages, lipopolysaccharides, and mycobacterial infection. J Immunol. 2015;194:6035–6044. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Etzerodt A, Moestrup SK. CD163 and inflammation: biological, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:2352–2363. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skytthe MK, Graversen JH, Moestrup SK. Targeting of CD163(+) Macrophages in Inflammatory and Malignant Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21155497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hou J, Wang X, Zhang M, Wang M, Gao P, Jiang Y. Circulating CD14(+)CD163(+)CD209(+) M2-like monocytes are associated with the severity of infection in Helicobacter pylori-positive patients. Mol Immunol. 2019;108:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cario E, Gerken G, Podolsky DK. Toll-like receptor 2 controls mucosal inflammation by regulating epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1359–1374. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Himmel ME, Hardenberg G, Piccirillo CA, Steiner TS, Levings MK. The role of T-regulatory cells and Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human inflammatory bowel disease. Immunology. 2008;125:145–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02939.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Korbecki J, Bajdak-Rusinek K. The effect of palmitic acid on inflammatory response in macrophages: an overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflamm Res. 2019;68:915–932. doi: 10.1007/s00011-019-01273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rocha DM, Caldas AP, Oliveira LL, Bressan J, Hermsdorff HH. Saturated fatty acids trigger TLR4-mediated inflammatory response. Atherosclerosis. 2016;244:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanemaru H, Yamane F, Tanaka H, Maeda K, Satoh T, Akira S. BATF2 activates DUSP2 gene expression and up-regulates NF-κB activity via phospho-STAT3 dephosphorylation. Int Immunol. 2018;30:255–265. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxy023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmalstig AA, Benoit SL, Misra SK, Sharp JS, Maier RJ. Noncatalytic Antioxidant Role for Helicobacter pylori Urease. J Bacteriol. 2018;200 doi: 10.1128/JB.00124-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skene C, Young A, Every A, Sutton P. Helicobacter pylori flagella: antigenic profile and protective immunity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:249–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang RX, Luo DJ, Sun AH, Yan J. Diversity of Helicobacter pylori isolates in expression of antigens and induction of antibodies. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4816–4822. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawson AJ. Helicobacter. In: James V, Carroll KC, Guido F, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Warnock DW. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 10th ed. Washington: Wiley, 2011: 900-915. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee SK, Stack A, Katzowitsch E, Aizawa SI, Suerbaum S, Josenhans C. Helicobacter pylori flagellins have very low intrinsic activity to stimulate human gastric epithelial cells via TLR5. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:1345–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clyne M, Ocroinin T, Suerbaum S, Josenhans C, Drumm B. Adherence of isogenic flagellum-negative mutants of Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter mustelae to human and ferret gastric epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4335–4339. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4335-4339.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dincă AL, Meliț LE, Mărginean CO. Old and New Aspects of H. pylori-Associated Inflammation and Gastric Cancer. Children (Basel) 2022;9 doi: 10.3390/children9071083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stent A, Every AL, Chionh YT, Ng GZ, Sutton P. Superoxide dismutase from Helicobacter pylori suppresses the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines during in vivo infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23 doi: 10.1111/hel.12459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen CC, Liou JM, Lee YC, Hong TC, El-Omar EM, Wu MS. The interplay between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1–22. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1909459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martín-Núñez GM, Cornejo-Pareja I, Coin-Aragüez L, Roca-Rodríguez MDM, Muñoz-Garach A, Clemente-Postigo M, Cardona F, Moreno-Indias I, Tinahones FJ. H. pylori eradication with antibiotic treatment causes changes in glucose homeostasis related to modifications in the gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heimesaat MM, Fischer A, Plickert R, Wiedemann T, Loddenkemper C, Göbel UB, Bereswill S, Rieder G. Helicobacter pylori induced gastric immunopathology is associated with distinct microbiota changes in the large intestines of long-term infected Mongolian gerbils. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bühling A, Radun D, Müller WA, Malfertheiner P. Influence of anti-Helicobacter triple-therapy with metronidazole, omeprazole and clarithromycin on intestinal microflora. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1445–1452. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He C, Peng C, Wang H, Ouyang Y, Zhu Z, Shu X, Zhu Y, Lu N. The eradication of Helicobacter pylori restores rather than disturbs the gastrointestinal microbiota in asymptomatic young adults. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12590. doi: 10.1111/hel.12590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iino C, Shimoyama T, Chinda D, Sakuraba H, Fukuda S, Nakaji S. Influence of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Atrophic Gastritis on the Gut Microbiota in a Japanese Population. Digestion. 2020;101:422–432. doi: 10.1159/000500634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Myllyluoma E, Ahlroos T, Veijola L, Rautelin H, Tynkkynen S, Korpela R. Effects of anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment and probiotic supplementation on intestinal microbiota. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jones TA, Hernandez DZ, Wong ZC, Wandler AM, Guillemin K. The bacterial virulence factor CagA induces microbial dysbiosis that contributes to excessive epithelial cell proliferation in the Drosophila gut. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006631. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen L, Xu W, Lee A, He J, Huang B, Zheng W, Su T, Lai S, Long Y, Chu H, Chen Y, Wang L, Wang K, Si J, Chen S. The impact of Helicobacter pylori infection, eradication therapy and probiotic supplementation on gut microenvironment homeostasis: An open-label, randomized clinical trial. EBioMedicine. 2018;35:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peek RM Jr, Fiske C, Wilson KT. Role of innate immunity in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric malignancy. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:831–858. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mohammadi SO, Yadegar A, Kargar M, Mirjalali H, Kafilzadeh F. The impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on gut microbiota-endocrine system axis; modulation of metabolic hormone levels and energy homeostasis. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19:1855–1861. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00608-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee M, Chang EB. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD) and the Microbiome-Searching the Crime Scene for Clues. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:524–537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sartor RB. Therapeutic manipulation of the enteric microflora in inflammatory bowel diseases: antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1620–1633. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bai X, Jiang L, Ruan G, Liu T, Yang H. Helicobacter pylori may participate in the development of inflammatory bowel disease by modulating the intestinal microbiota. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135:634–638. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:477–489. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.von Moltke J, Ayres JS, Kofoed EM, Chavarría-Smith J, Vance RE. Recognition of bacteria by inflammasomes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:73–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang X, Li C, Chen D, He X, Zhao Y, Bao L, Wang Q, Zhou J, Xie Y. H. pylori CagA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to promote gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. Inflamm Res. 2022;71:141–155. doi: 10.1007/s00011-021-01522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hitzler I, Sayi A, Kohler E, Engler DB, Koch KN, Hardt WD, Müller A. Caspase-1 has both proinflammatory and regulatory properties in Helicobacter infections, which are differentially mediated by its substrates IL-1β and IL-18. J Immunol. 2012;188:3594–3602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oertli M, Sundquist M, Hitzler I, Engler DB, Arnold IC, Reuter S, Maxeiner J, Hansson M, Taube C, Quiding-Järbrink M, Müller A. DC-derived IL-18 drives Treg differentiation, murine Helicobacter pylori-specific immune tolerance, and asthma protection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1082–1096. doi: 10.1172/JCI61029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N, Lanyon G, Martin M, Fraumeni JF Jr, Rabkin CS. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398–402. doi: 10.1038/35006081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tu S, Bhagat G, Cui G, Takaishi S, Kurt-Jones EA, Rickman B, Betz KS, Penz-Oesterreicher M, Bjorkdahl O, Fox JG, Wang TC. Overexpression of interleukin-1beta induces gastric inflammation and cancer and mobilizes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arnold IC, Dehzad N, Reuter S, Martin H, Becher B, Taube C, Müller A. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents allergic asthma in mouse models through the induction of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3088–3093. doi: 10.1172/JCI45041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Engler DB, Leonardi I, Hartung ML, Kyburz A, Spath S, Becher B, Rogler G, Müller A. Helicobacter pylori-specific protection against inflammatory bowel disease requires the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-18. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:854–861. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zaki MH, Boyd KL, Vogel P, Kastan MB, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. The NLRP3 inflammasome protects against loss of epithelial integrity and mortality during experimental colitis. Immunity. 2010;32:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Takagi H, Kanai T, Okazawa A, Kishi Y, Sato T, Takaishi H, Inoue N, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Hoshino K, Takeda K, Akira S, Watanabe M, Ishii H, Hibi T. Contrasting action of IL-12 and IL-18 in the development of dextran sodium sulphate colitis in mice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:837–844. doi: 10.1080/00365520310004047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Araki A, Kanai T, Ishikura T, Makita S, Uraushihara K, Iiyama R, Totsuka T, Takeda K, Akira S, Watanabe M. MyD88-deficient mice develop severe intestinal inflammation in dextran sodium sulfate colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:16–23. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fukata M, Breglio K, Chen A, Vamadevan AS, Goo T, Hsu D, Conduah D, Xu R, Abreu MT. The myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) is required for CD4+ T cell effector function in a murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol. 2008;180:1886–1894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gibson DL, Ma C, Bergstrom KS, Huang JT, Man C, Vallance BA. MyD88 signalling plays a critical role in host defence by controlling pathogen burden and promoting epithelial cell homeostasis during Citrobacter rodentium-induced colitis. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:618–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yao X, Zhang C, Xing Y, Xue G, Zhang Q, Pan F, Wu G, Hu Y, Guo Q, Lu A, Zhang X, Zhou R, Tian Z, Zeng B, Wei H, Strober W, Zhao L, Meng G. Remodelling of the gut microbiota by hyperactive NLRP3 induces regulatory T cells to maintain homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1896. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01917-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Evans DJ Jr, Evans DG, Takemura T, Nakano H, Lampert HC, Graham DY, Granger DN, Kvietys PR. Characterization of a Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2213–2220. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2213-2220.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Satin B, Del Giudice G, Della Bianca V, Dusi S, Laudanna C, Tonello F, Kelleher D, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C, Rossi F. The neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) of Helicobacter pylori is a protective antigen and a major virulence factor. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1467–1476. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Polenghi A, Bossi F, Fischetti F, Durigutto P, Cabrelle A, Tamassia N, Cassatella MA, Montecucco C, Tedesco F, de Bernard M. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori crosses endothelia to promote neutrophil adhesion in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178:1312–1320. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Codolo G, Coletta S, D'Elios MM, de Bernard M. HP-NAP of Helicobacter pylori: The Power of the Immunomodulation. Front Immunol. 2022;13:944139. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.944139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Montemurro P, Nishioka H, Dundon WG, de Bernard M, Del Giudice G, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C. The neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) of Helicobacter pylori is a potent stimulant of mast cells. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:671–676. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<671::aid-immu671>3.3.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Amedei A, Cappon A, Codolo G, Cabrelle A, Polenghi A, Benagiano M, Tasca E, Azzurri A, D'Elios MM, Del Prete G, de Bernard M. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori promotes Th1 immune responses. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1092–1101. doi: 10.1172/JCI27177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Middleton J, Neil S, Wintle J, Clark-Lewis I, Moore H, Lam C, Auer M, Hub E, Rot A. Transcytosis and surface presentation of IL-8 by venular endothelial cells. Cell. 1997;91:385–395. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wen SH, Hong ZW, Chen CC, Chang HW, Fu HW. Helicobacter pylori Neutrophil-Activating Protein Directly Interacts with and Activates Toll-like Receptor 2 to Induce the Secretion of Interleukin-8 from Neutrophils and ATRA-Induced Differentiated HL-60 Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms222111560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tsai CC, Kuo TY, Hong ZW, Yeh YC, Shih KS, Du SY, Fu HW. Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein induces release of histamine and interleukin-6 through G protein-mediated MAPKs and PI3K/Akt pathways in HMC-1 cells. Virulence. 2015;6:755–765. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2015.1043505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ramachandran M, Jin C, Yu D, Eriksson F, Essand M. Vector-encoded Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein promotes maturation of dendritic cells with Th1 polarization and improved migration. J Immunol. 2014;193:2287–2296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Guo X, Ding C, Lu J, Zhou T, Liang T, Ji Z, Xie P, Liu X, Kang Q. HP-NAP ameliorates OXA-induced atopic dermatitis symptoms in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2020;42:416–422. doi: 10.1080/08923973.2020.1806869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Codolo G, Mazzi P, Amedei A, Del Prete G, Berton G, D'Elios MM, de Bernard M. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori down-modulates Th2 inflammation in ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2355–2363. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kałużna A, Olczyk P, Komosińska-Vassev K. The Role of Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells in the Pathogenesis and Development of the Inflammatory Response in Ulcerative Colitis. J Clin Med. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/jcm11020400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kmieć Z, Cyman M, Ślebioda TJ. Cells of the innate and adaptive immunity and their interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Adv Med Sci. 2017;62:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bamias G, Cominelli F. Role of type 2 immunity in intestinal inflammation. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31:471–476. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ding ZH, Xu XP, Wang TR, Liang X, Ran ZH, Lu H. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in inflammatory bowel disease in China: A case-control study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]