See related article, p 1214

The catalogue of neurodegenerative diseases that appear to propagate via misfolded proteins begetting further misfolded proteins has grown to impressive size. Starting with the groundbreaking identification of transmissible conformations of prion protein, the list has since extended to include α-synuclein, TDP43, and tau.1 Propagation of misfolded proteins all appear to involve a seeding step in which abnormal protein deposits serve as a scaffold for additional deposition of previously normal protein.

A body of literature—now including the report in the current issue of Stroke from Leiden University Medical Center and collaborating investigators in the Netherlands2—firmly places Aβ (beta-amyloid) on this list. Transmissibility of brain amyloidosis via intracerebral injection of exogenous Aβ was observed in marmosets (a nonhuman primate that expresses human-like Aβ) as early as 1993 and over the early 2000’s in injected transgenic mice expressing human amyloid precursor protein.3 Notably, transgenic mice systemically injected with Aβ-containing extracts developed amyloid deposits predominantly in cerebral vessels as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA).4

The past decade has seen this experimental finding identified as a real, though uncommon, mechanism for human disease. An initial 2015 report found extensive Aβ deposition with severe CAA in 4 of 8 autopsied brains from individuals previously diagnosed with iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease due to childhood treatment with pituitary-derived human growth hormone.5 The 18 new individuals reported by the Leiden University Medical Center investigators together with additional probable or possible iatrogenic CAA (iCAA) cases identified from systematic literature review2,6 bring the number of reported cases to 49, with more likely to emerge as echoes of the neurosurgical use of human tissue primarily during the 1970s and 1980s. These 49 individuals include some with equivocal evidence of human tissue seeding, such as those whose neurosurgical procedures did not use human tissue (where the source of amyloid may have been contaminated instruments) or with traumatic brain injury without explicit documentation of neurosurgery. Although these equivocal histories raise the possibility of alternative mechanisms for generating early-onset CAA, the marked overrepresentation of exposure to human tissue argues that exposure to exogenous amyloid rather than neurosurgery or trauma per se is the inciting cause.

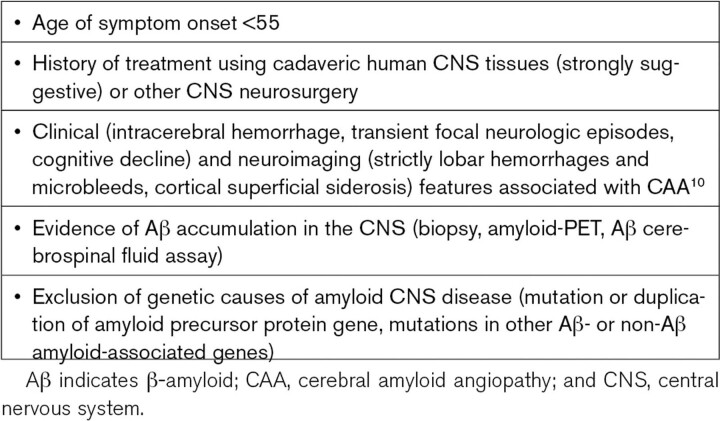

From a clinical standpoint, the impact of iCAA is devastating to those who develop early onset intracerebral hemorrhage (mean age of first presentation 43, earliest age 27),2 but fortunately quite narrow when considered against the overall burden of CAA. Widespread recognition of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease has led to worldwide standards for discontinuation of high-risk tissues7 and decontamination of potentially exposed instruments,8 which should allow iCAA to dwindle away. It nonetheless remains a substantial diagnostic consideration for individuals diagnosed with CAA at unexpectedly early ages and without family history suggestive of one of the rare autosomal dominant forms of CAA or Alzheimer disease (Table).9 Diagnostic criteria proposed (but not yet validated) by investigators at University College London6 include symptom onset before age 55, history of exposure to cadaveric human nervous tissue or other neurosurgical procedures, neuroimaging features of CAA,10 evidence (by lumbar puncture, PET scan, or biopsy) of Aβ accumulation in the brain, and exclusion of genetic causes. The London investigators note that the criteria may be applied flexibly in different situations, observing for example that presentation at older ages might be expected for inciting neurosurgeries performed in young adulthood rather than childhood. The sharp rise in sporadic CAA with age, however, will tend to make iCAA more difficult to diagnose in older age groups.

Table.

Hints to Suspect Iatrogenic CAA

The biological implications of iCAA are quite substantial, providing a unique window on the pathways by which Aβ seeds produce human disease. One observation is that once introduced into the central nervous system, Aβ fibrils can circulate widely before depositing: The reported neurosurgical cases show no consistent relationship between site of human tissue exposure—often quite distant from the brain as in the case of spinal surgeries—and site of CAA-related hemorrhage.2 Another striking insight is that the preferential sites of Aβ propagation appear to be the cerebral vessels rather than the brain parenchyma, as the predominantly observed pathology has been CAA rather than the mature parenchymal plaques characteristic of Alzheimer disease.6 Studies in transgenic mice found a similar predilection for vascular Aβ deposition regardless of whether the inoculated amyloid was in the form of Alzheimer disease, CAA, or both.11 These observations highlight the key role of the perivascular clearance pathway as a highway for intracerebral transportation—and pathological deposition—of Aβ and as a nexus for interaction between cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative disease.12

A further biological insight from iCAA is the 3 to 4 decade time interval between exposure to exogenous Aβ and first disease symptom.2,6 As noted by the Leiden University Medical Center authors, this interval is reminiscent of the time gap observed in carriers of the Dutch-type hereditary CAA mutation between initial detection of reduced cerebrospinal fluid Aβ (believed to be a marker of brain deposition) and first ICH.13,14 The comparable time courses suggest that these very different forms of early-onset CAA may follow a similar series of pathogenic steps in progressing from seed to bleed. These intervening steps may include expansion of the initial Aβ deposits,15 loss of cerebrovascular physiologic reactivity,16 nonhemorrhagic brain injury such as white matter ultrastructural damage,17 and remodeling of amyloid-laden vessels18 as a final link to CAA-related hemorrhage. Seen from this perspective, CAA-related hemorrhagic lesions, though generally the hallmark for the disorder’s in vivo diagnosis,10 ironically appear to be late developments in its complex multi-decade progression.

The seed-to-bleed story of iCAA highlights both the challenge and opportunities for treating the overall entity of CAA. The challenges come from the extensive series of changes set in motion by initial seeding that appear fully baked into the brain by the time of first hemorrhage; it is unclear which of these changes can be meaningfully modified at the time of diagnosis. The opportunities come from this same extended prodromal interval and multistep pathogenic pathway, which offer a sizable window for interventions aimed at delaying or avoiding progression to clinical symptoms. This line of thought underlines the importance of identifying new methods for early CAA detection to allow early-stage disease-modifying therapy for this ever challenging and deadly form of stroke.

Article Information

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

For Disclosures, see page 1225.

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association.

References

- 1.Jaunmuktane Z, Brandner S. Invited review: the role of prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2020;46:522–545. doi: 10.1111/nan.12592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaushik K, van Etten ES, Siegerink B, Kappelle LJ, Lemstra AW, Schreuder FHBM, Klijn CJM, Peul WC, Terwindt GM, van Walderveen MAA, et al. Iatrogenic cerebral amyloid angiopathy after neurosurgery: frequency, clinical profile, radiological features and outcome. Stroke. 2023;54:1214–1223. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.041690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friesen M, Meyer-Luehmann M. Abeta seeding as a tool to study cerebral amyloidosis and associated pathology. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:233. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisele YS, Obermuller U, Heilbronner G, Baumann F, Kaeser SA, Wolburg H, Walker LC, Staufenbiel M, Heikenwalder M, Jucker M. Peripherally applied abeta-containing inoculates induce cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Science. 2010;330:980–982. doi: 10.1126/science.1194516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaunmuktane Z, Mead S, Ellis M, Wadsworth JD, Nicoll AJ, Kenny J, Launchbury F, Linehan J, Richard-Loendt A, Walker AS, et al. Evidence for human transmission of amyloid-beta pathology and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nature. 2015;525:247–250. doi: 10.1038/nature15369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee G, Samra K, Adams ME, Jaunmuktane Z, Parry-Jones AR, Grieve J, Toma AK, Farmer SF, Sylvester R, Houlden H, et al. Iatrogenic cerebral amyloid angiopathy: an emerging clinical phenomenon. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2022-328792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Who tables on tissue infectivity distribution in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies:: Updated 2010. website. Accessed February 4, 2023. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/biologicals/blood-products/document-migration/tablestissueinfectivity.pdf.

- 8.Belay ED, Blase J, Sehulster LM, Maddox RA, Schonberger LB. Management of neurosurgical instruments and patients exposed to creutzfeldt-jakob disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:1272–1280. doi: 10.1086/673986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revesz T, Holton JL, Lashley T, Plant G, Frangione B, Rostagno A, Ghiso J. Genetics and molecular pathogenesis of sporadic and hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:115–130. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0501-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Frosch MP, Baron JC, Pasi M, Albucher JF, Banerjee G, Barbato C, Bonneville F, Brandner S, et al. The boston criteria version 2.0 for cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a multicentre, retrospective, mri-neuropathology diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:714–725. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00208-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamaguchi T, Kim JH, Hasegawa A, Goto R, Sakai K, Ono K, Itoh Y, Yamada M. Exogenous abeta seeds induce abeta depositions in the blood vessels rather than the brain parenchyma, independently of abeta strain-specific information. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021;9:151. doi: 10.1186/s40478-021-01252-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, Hernandez-Guillamon M, Pruzin J, Sperling R, van Veluw SJ. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and alzheimer disease - one peptide, two pathways. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:30–42. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0281-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Etten ES, Verbeek MM, van der Grond J, Zielman R, van Rooden S, van Zwet EW, van Opstal AM, Haan J, Greenberg SM, van Buchem MA, et al. Beta-amyloid in csf: biomarker for preclinical cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2017;88:169–176. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Etten ES, Gurol ME, van der Grond J, Haan J, Viswanathan A, Schwab KM, Ayres AM, Algra A, Rosand J, van Buchem MA, et al. Recurrent hemorrhage risk and mortality in hereditary and sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2016;87:1482–1487. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robbins EM, Betensky RA, Domnitz SB, Purcell SM, Garcia-Alloza M, Greenberg C, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT, Greenberg SM, Frosch MP, et al. Kinetics of cerebral amyloid angiopathy progression in a transgenic mouse model of alzheimer disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26:365–371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3854-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Opstal AM, van Rooden S, van Harten T, Ghariq E, Labadie G, Fotiadis P, Gurol ME, Terwindt GM, Wermer MJ, van Buchem MA, et al. Cerebrovascular function in presymptomatic and symptomatic individuals with hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:115–122. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30346-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirzadi Z, Yau WW, Schultz SA, Schultz AP, Scott MR, Goubran M, Mojiri-Forooshani P, Joseph-Mathurin N, Kantarci K, Preboske G, et al. ; DIAN Investigators. Progressive white matter injury in preclinical dutch cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2022;92:358–363. doi: 10.1002/ana.26429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Veluw SJ, Scherlek AA, Freeze WM, Ter Telgte A, van der Kouwe AJ, Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM. Different microvascular alterations underlie microbleeds and microinfarcts. Ann Neurol. 2019;86:279–292. doi: 10.1002/ana.25512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]