Abstract

Background and Objectives

Current understanding based on older studies is that pc-BPPV is far more common than hc-BPPV. Such studies are limited by small sample sizes, and often the supine roll test for hc-BPPV is not performed. To better estimate the prevalence of hc-BPPV, we studied a large cross-section of patients with VOG-diagnosed BPPV.

Methods

Using a cross-sectional study of patients with BPPV, we investigated patients referred to NeuroEquilibrium specialty clinics throughout India between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2021. All patients were evaluated with video oculography (VOG) during positional tests, and all diagnoses were confirmed by a neurotologist and neurologist.

Results

Of 3,975 patients with VOG-confirmed and specialist-diagnosed BPPV (median age, 51 years; 56.6% women), pc-BPPV accounted for 1,901 (47.8%), hc-BPPV was seen in 1,842 (46.3%), and anterior canal BPPV was found in 28 (0.7%) patients.

Discussion

This study found that hc-BPPV is far more common than previously reported. It is important to perform the supine roll test in addition to the Dix-Hallpike in all patients suspected with BPPV. Better training to diagnose patients with BPPV and to accurately recognize the nystagmus pattern of hc-BPPV should be a priority.

Introduction

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is defined by brief episodes of dizziness, usually lasting less than 1 minute that are triggered by change of position and resolve with rest. It is a clinical diagnosis based on triggered and transient nystagmus that is evoked by diagnostic positional maneuvers. The cause is calcium carbonate particles called otoliths which migrate from the utricle into one of the 3 semicircular canals. Once in the canal, they may float freely (canalolithiasis)1 or attach to the cupula (cupulolithiasis).2 Most studies have identified posterior canal BPPV (pc-BPPV) as the dominant form (60%–90%), followed by horizontal canal (hc-BPPV) (5%–15%) and then anterior canal (1%).3

Positional tests are used to diagnose BPPV by moving the subject's head in the plane of the affected canal causing the debris to move under the effect of gravity. The Dix-Hallpike test is used to diagnose pc-BPPV, the supine roll test is used to diagnose hc-BPPV, and the supine head hanging test is used to diagnose anterior canal BPPV.4 Although the episodes are brief and BPPV is ultimately a self-limiting condition, patients often experience debilitating symptoms. Many clinicians do not consider the diagnosis of BPPV unless the patient endorses spinning vertigo, as opposed to other descriptors of dizziness. Incorrect diagnosis (including misidentifying the affected canal) and lack of treatment can negatively affect quality of life, and BPPV may be far from “benign”. Patients are at increased risk for falls, injuries, and impairment in the performance of daily activities.5-11 Providers experience frustration with future patients (“the Epley never works for me”).12 Despite the established efficacy of the repositioning maneuvers, various studies confirmed their underuse,12-14 and only 10% of BPPV patients are treated with canalolith-repositioning maneuvers.15,16 It is estimated that more than 65% of patients with BPPV undergo unnecessary diagnostic testing or therapeutic interventions.14,17 The objective of this study was to better understand the prevalence of hc-BPPV.

Methods

We examined data from a retrospective cohort of patients seen between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2021 at 124 NeuroEquilibrium Dizziness Clinics in various cities across India where patients complaining of vertigo and dizziness were evaluated. These clinics are located in several multispecialty hospitals and ENT and neurology clinics. At the time of the encounter, a digitized history-taking module was used to prospectively collect information including symptom onset, duration of episodes, evolution over time, and associated symptoms such as hearing loss, tinnitus, headaches, falls, and loss of consciousness. Neurotological evaluation including video oculography (VOG), subjective visual vertical (SVV), dynamic visual acuity (DVA), and video head impulse test (vHIT)/caloric test was performed in all patients. The VOG recorded spontaneous nystagmus (with and without fixation) and nystagmus on positional testing including supine roll test, Dix-Hallpike, and supine head hanging tests. Our protocol was to perform the supine roll test before the Dix-Hallpike test. The VOG equipment used in this study was manufactured by NeuroEquilibrium (NeuroEquilibrium.com). The VOG and the positional tests were performed before other tests.

Inclusion criteria were patients with dizziness and nystagmus detected on positional testing that was consistent with BPPV according to the criteria described by Bhattacharyya.18 We excluded patients who presented with symptoms not compatible with BPPV including loss of consciousness, slurred speech and blurred vision, patients with spontaneous nystagmus or nystagmus that did not otherwise match that seen in BPPV, and patients with restrictions of neck mobility that precluded the safe performance of positional testing. Patients with vestibular migraine as defined by the consensus documents of the Barany Society and the International Headache Society were also excluded from this study.19

Final diagnosis was made by consensus of a neurotologist (AB) and a neurologist using the NeuroEquilibrium cloud-based remote diagnostic platform that included data from the history, investigation findings, and VOG videos. Because reviewers were part of the active patient care team, all clinical patient information was available to them, but they were blinded to personal patient information. In the case of a difference of opinion, final diagnosis was achieved by consensus.

Descriptive analyses were performed to present the distribution of each characteristic of patients included. The χ2 test for the categorical characteristics or nonparametric Wilcoxon rank test for the continuous characteristics were performed to determine the difference of each characteristics by the type of BPPV. All data analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and a two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There is no conflict to report with the NeuroEquilibrium Diagnostic Systems Private Limited platform except that 2 of the authors are directors (RB, AB).

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All patients gave written consent for their anonymized clinical data to be used for research purposes. Ethical review and approval were not required for the study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Results

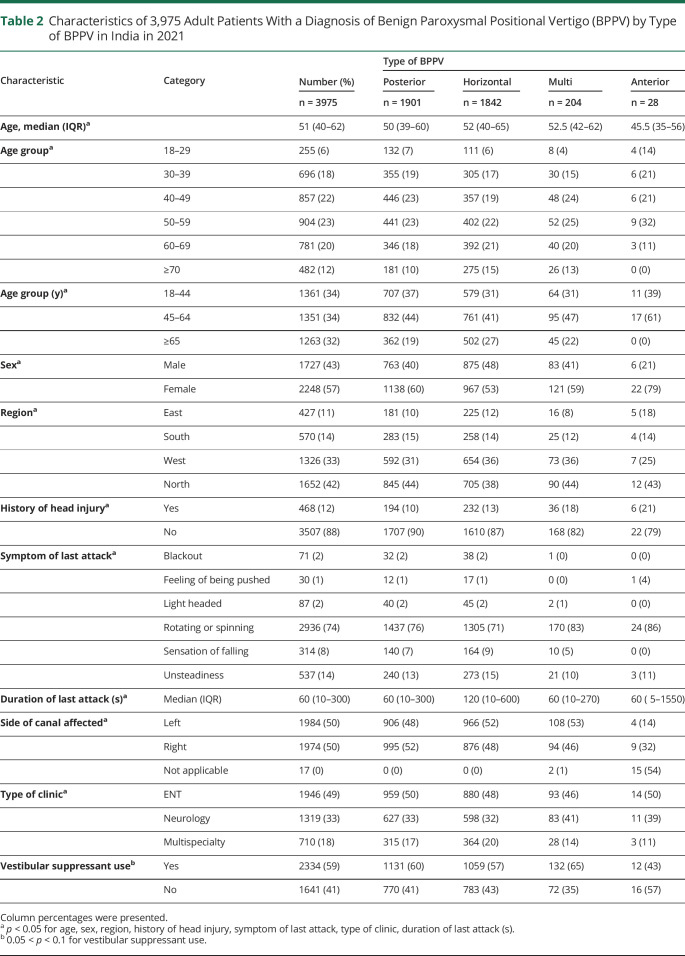

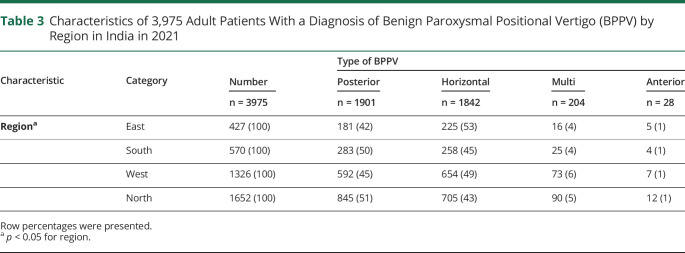

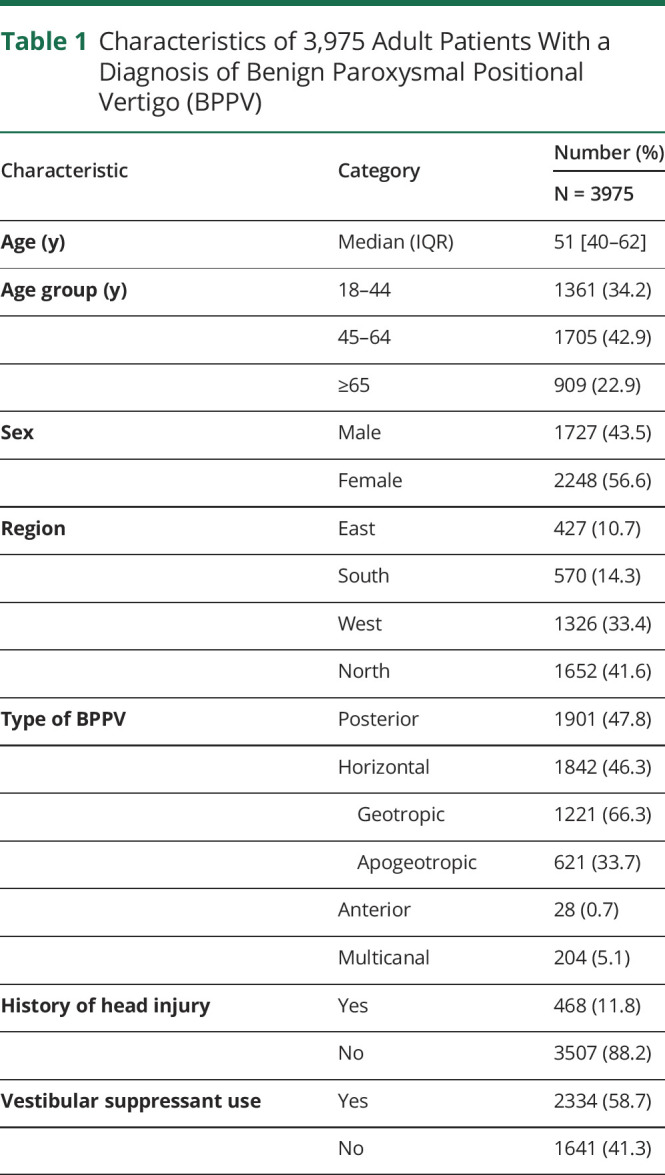

Of the 3975 patients with VOG-confirmed BPPV, pc-BPPV was diagnosed in 1901 (47.8%), hc-BPPV was diagnosed in 1842 (46.3%), and anterior canal BPPV was found in 28 (0.7%). Multicanal BPPV was present in 204 (5.1%) patients (Table 1). In hc-BPPV, 66.3% were the geotropic variant and 33.7% were the apogeotropic variant. The median age, sex, region, history of head injury, symptom of last attack, type of clinic, and duration of last attack were all statistically significantly different comparing posterior and horizontal canal BPPV (p < 0.05, Tables 2 and 3). Less than 75% of patients described their symptoms as true spinning vertigo. In addition, 11.8% had history of head injury, and 58.7% were taking vestibular suppressants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 3,975 Adult Patients With a Diagnosis of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

Table 2.

Characteristics of 3,975 Adult Patients With a Diagnosis of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) by Type of BPPV in India in 2021

Table 3.

Characteristics of 3,975 Adult Patients With a Diagnosis of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) by Region in India in 2021

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest case series of patients with VOG-evaluated BPPV ever reported. The prevalence of hc-BPPV is much higher in our study than previously reported, although 2 previous studies reported similar results.20,21 Because of our large number of patients, there were some differences between patients with pc-BPPV and hc-BPPV that were statistically significant but not clinically meaningful. For example, the differences between regions, a proxy for sensitivity analysis, found differences, but overall, the results found much higher proportions of hc-BPPV than have been generally reported. Another strength of our study is that all BPPV diagnoses were confirmed by VOG and a neurotologist/neurologist consensus. Although VOG is rarely used in routine frontline practice, its use in all our patients allows for a confident and precise determination of the affected canal.22 VOG recording of positional tests with removal of optic fixation allow visualization and recording of the true character of nystagmus. As compared with naked eye examination, VOG recording allows the clinician to be able to detect subtle nystagmus which may be otherwise missed and also helps very strong nystagmus to be correctly analyzed regarding direction and torsion.

Our finding that hc-BPPV is nearly as common as pc-BPPV has important implications for frontline providers. It has been suggested that patients with the hc-BPPV variant have worse perceived disability than the other canal variants.11 This likely affects the canal affected in patients presenting to frontline clinicians because patients with worse symptoms are more likely to see their general practitioner or seek care in an emergency department (ED). In fact, a study of 772 consecutive patients with BPPV found that a higher proportion of patients with BPPV who presented to the ED had hc-BPPV compared with those who presented to an outpatient clinic, consistent with the notion that those with hc-BPPV were more symptomatic.23

Most nonspecialists are less familiar with hc-BPPV and the supine roll test (simulation Video 1).24-26 This results in missed opportunities for correct diagnosis and treatment.27 Omitting the supine roll test could lead to underestimation of the prevalence of hc-BPPV.14,20,24 An important feature of our clinical protocol is that the supine roll test was performed before doing the Dix-Hallpike test, whereas most clinicians start with the Dix-Hallpike test, which may affect the results. Simulation data suggest that the Dix-Hallpike test can displace otolith debris from their position in the horizontal canal affecting the outcome of the supine roll test22 (simulation Video 2). Precise diagnosis of BPPV including the canal and the side affected is critical for successful treatment.7,28 Our results are also hypothesis-generating, suggesting that performing the supine roll before the Dix-Hallpike may allow for better identification of hc-BPPV.

Simulation 1 Supine Roll Horizontal Canal Geotropic Variant. This is an animation that demonstrates the supine roll test in a patient with geotropic horizontal canal BPPV.Download Supplementary Video 1 (8MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200191_Video_1

Simulation 2 Dix-Hallpike in patient with Horizontal Canal BPPV. This animation shows how DH test can displace crystals in the HC. It was on this basis that we recommend the supine roll test before the Dix-Hallpike test.Download Supplementary Video 2 (20.6MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200191_Video_2

A limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. This could have introduced confounders causing the higher incidence of hc-BPPV in India that would be impossible to identify. One potential confounder was the possibility of misclassifying vestibular migraine as hc-BPPV. Vestibular migraine may present with positional nystagmus, but the nystagmus typically does not follow the crescendo-decrescendo pattern of BPPV nystagmus and also lasts for a longer time.29 To avoid incorrectly diagnosing BPPV in patients with vestibular migraine, we used the best-known consensus guidelines while collecting these data to avoid making such errors.30 The rigor of our diagnostic evaluation makes this unlikely to have occurred frequently.

Horizontal canal-BPPV is more common than previously reported. It is important to perform the supine roll test in addition to the Dix-Hallpike in all dizzy patients suspected of having BPPV. Better training to diagnose patients with BPPV and to accurately recognize the nystagmus pattern of hc-BPPV should be a priority.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ hc-BPPV is more common than previously described.

→ In addition to the Dix-Hallpike test, the supine roll test should also be performed.

→ Better training to diagnose patients with BPPV and accurately recognize the nystagmus pattern of hc-BPPV should be a priority.

Supplementary Material

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Hall SF, Ruby RR, McClure JA. The mechanics of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol. 1979;8(2):151-158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuknecht HF. Cupulolithiasis. Arch Otolaryngol 1969;90(6):765-778. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1969.00770030767020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JS, Zee DS. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1138-1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1309481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omron R. Peripheral vertigo. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019;37(1):11-28. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez-Escamez JA, Gamiz MJ, Fernandez-Perez A, Gomez-Fiñana M. Long-term outcome and health-related quality of life in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(6):507-511. doi: 10.1007/S00405-004-0841-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oghalai JS, Manolidis S, Barth JL, Stewart MG, Jenkins HA. Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(5):630-634. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70187-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuma E Maia F, Ramos BF, Cal R, Brock CM, Mangabeira Albernaz PL, Strupp M. Management of lateral semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Front Neurol. 2020;11:1040. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Do YK, Kim J, Park CY, Chung MH, Moon S, Yang HS. The effect of early canalith repositioning on benign paroxysmal positional vertigo on recurrence. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;4(3):113-117. doi: 10.3342/CEO.2011.4.3.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganança FF, Gazzola JM, Ganança CF, Caovilla HH, Ganança MM, Cruz OLM. Quedas em idosos com Vertigem Posicional Paroxística Benigna. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76(1):113-120. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000100019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jumani K, Powell J. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: management and its impact on falls. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2017;126(8):602-605. doi: 10.1177/0003489417718847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martens C, Goplen FK, Aasen T, Nordfalk KF, Nordahl SHG. Dizziness handicap and clinical characteristics of posterior and lateral canal BPPV. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(8):2181-2189. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05459-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerber KA, Forman J, Damschroder L, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to ED physician use of the test and treatment for BPPV. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7(3):214-224. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polensek SH, Sterk CE, Tusa RJ. Screening for vestibular disorders: a study of clinicians' compliance with recommended practices. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14(5):CR238-CR242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polensek SH, Tusa R. Unnecessary diagnostic tests often obtained for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15(7):MT89-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fife TD, Iverson DJ, Lempert T, et al. . Practice parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review): [RETIRED]. Neurology. 2008;70(22):2067-2074. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313378.77444.ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, et al. . Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;78(7):710-715. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Yu D, Song N, Su K, Yin S. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo associated with current practice. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271(2):261-264. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2333-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, et al. . Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(3_suppl l):S1–S47. doi: 10.1177/0194599816689667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, et al. . Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res. 2012;22(4):167-172. doi: 10.3233/VES-2012-0453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung KW, Park KN, Ko MH, et al. . Incidence of horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as a function of the duration of symptoms. Otolo Neurotol. 2009;30(2):202-205. doi: 10.1097/mao.0b013e31818f57da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moon SY, Kim JS, Kim BK, et al. . Clinical characteristics of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in Korea: a multicenter study. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21(3):539-543. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.3.539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhandari A, Bhandari R, Kingma H, Strupp M. Modified interpretations of the supine roll test in horizontal canal BPPV based on simulations: how the initial position of the debris in the canal and the sequence of testing affects the direction of the nystagmus and the diagnosis. Front Neurol. 2022;13:881156. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.881156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim CH, Jeong H, Shin JE. Incidence of idiopathic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo subtype by hospital visit type: experience of a single tertiary referral centre. J Laryngol Otol. 2023:137(1):57-60. doi:DOI. 10.1017/S0022215121003923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Male AJ, Ramdharry GM, Grant R, Davies RA, Beith ID. A survey of current management of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) by physiotherapists' interested in vestibular rehabilitation in the UK. Physiotherapy. 2019;105(3):307-314. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd M, Mackintosh A, Grant C, et al. . Evidence-based management of patients with vertigo, dizziness, and imbalance at an Australian metropolitan health service: an observational study of clinical practice. Physiother Theor Pract. 2020;36(7):818-825. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1511020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edlow JA, Kerber K. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a practical approach for emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(5):579-588. doi: 10.1111/acem.14558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omron R, Kotwal S, Garibaldi BT, Newman-Toker DE. The diagnostic performance feedback “Calibration Gap”: why clinical experience alone is not enough to prevent serious diagnostic errors. AEM Educa Train. 2018;2(4):339-342. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schubert MC, Helminski J, Zee DS, et al. . Horizontal semicircular canal jam: two new cases and possible mechanisms. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(1):163-167. doi: 10.1002/lio2.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beh SC. Horizontal direction-changing positional nystagmus and vertigo: a case of vestibular migraine masquerading as horizontal canal BPPV. Headache. 2018;58(7):1113-1117. doi: 10.1111/head.13356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, et al. . Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria (Update)1: literature update 2021. J Vestib Res. 2022;32(1):1-6. doi: 10.3233/VES-201644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Simulation 1 Supine Roll Horizontal Canal Geotropic Variant. This is an animation that demonstrates the supine roll test in a patient with geotropic horizontal canal BPPV.Download Supplementary Video 1 (8MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200191_Video_1

Simulation 2 Dix-Hallpike in patient with Horizontal Canal BPPV. This animation shows how DH test can displace crystals in the HC. It was on this basis that we recommend the supine roll test before the Dix-Hallpike test.Download Supplementary Video 2 (20.6MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/200191_Video_2

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.