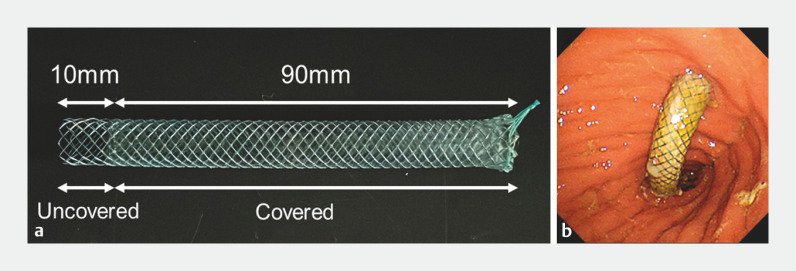

A partially covered self-expandable metal stent (PCSEMS) is preferred in endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUS-HGS) to prevent stent dislocation and branch duct occlusion 1 2 . A PCSEMS with a 10-mm uncovered part on the proximal end (Modified Giobor Stent; Taewoong Medical, Seoul) ( Fig. 1 a) has been used frequently 2 3 ; however, tissue hyperplasia occurs around the uncovered part, leading to recurrent biliary obstruction (RBO) 2 3 . RBO due to hyperplasia is sometimes hardened with abundant fibrosis, resulting in failed guidewire passage during endoscopic reintervention 3 4 . Here, we present a novel technique to regain biliary access after EUS-HGS with subsequent hyperplasia with the uncovered portion of the PCSEMS.

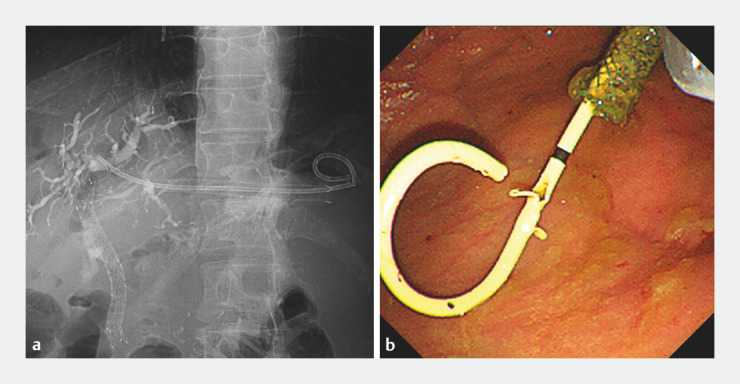

Fig. 1.

a A partially covered self-expandable metal stent (Modified Giobor Stent; Taewoong Medical, Seoul, South Korea) made of braided nitinol wire partially covered by a silicone membrane. The proximal end has a 10-mm uncovered portion. b Endoscopic view of the partially covered metal stent in the gastric lumen after endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy.

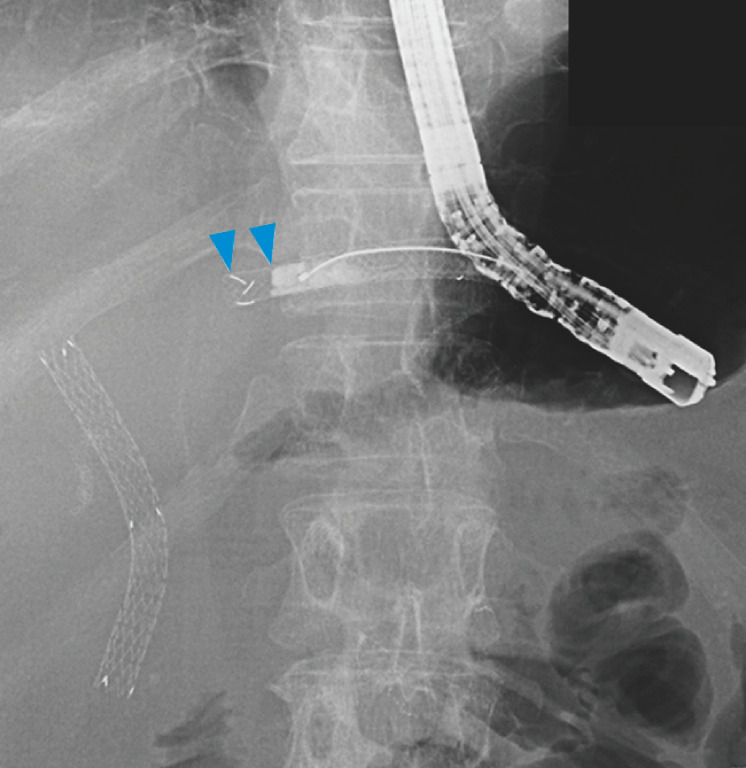

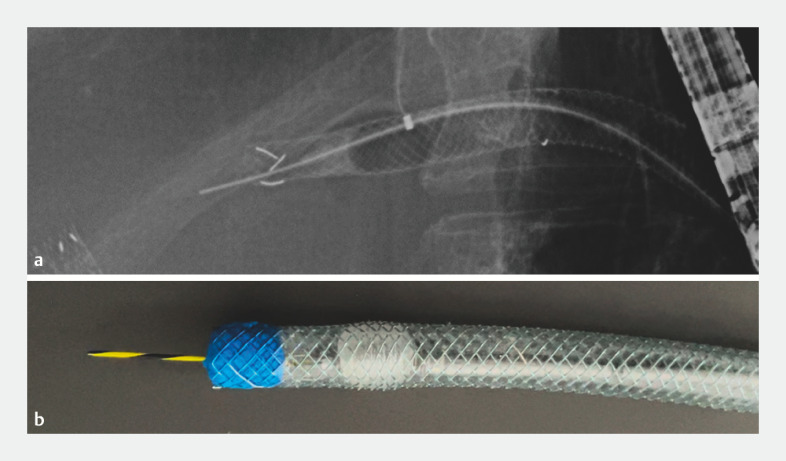

A 67-year-old male with a history of distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction was admitted due to jaundice. The patient had undergone EUS-HGS with the PCSEMS for biliary obstruction due to lymph node metastasis 8 months before admission ( Fig. 1 b). To relieve jaundice, reintervention via the distal end of the PCSEMS was performed. A cannulation catheter was inserted from the distal end of the PCSEMS, but a 0.035-inch guidewire (Jagwire; Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts, United States) could not be advanced beyond the PCSEMS. The uncovered part of the PCSEMS was not imaged by contrast medium injection, indicating a complete RBO due to hyperplasia ( Fig. 2 ). Next, a stone extraction balloon was inflated inside the PCSEMS to allow passage of the guidewire through the center of the PCSEMS ( Fig. 3 ). However, the hyperplasia was too stiff. Finally, a “piercing technique” using the stiff back end of the guidewire 5 was performed, which allowed the guidewire to smoothly advance the stricture ( Fig. 4 , Video 1 ). After dilating the uncovered part with an 8-mm balloon dilator, a dedicated plastic stent was successfully deployed through the PCSEMS ( Fig. 5 ). The patient’s jaundice resolved after endoscopic revision and was discharged 6 days after admission.

Fig. 2.

The uncovered part of the partially covered metal tent was not imaged by contrast medium injection (arrowheads), indicating a complete recurrent biliary obstruction due to hyperplasia.

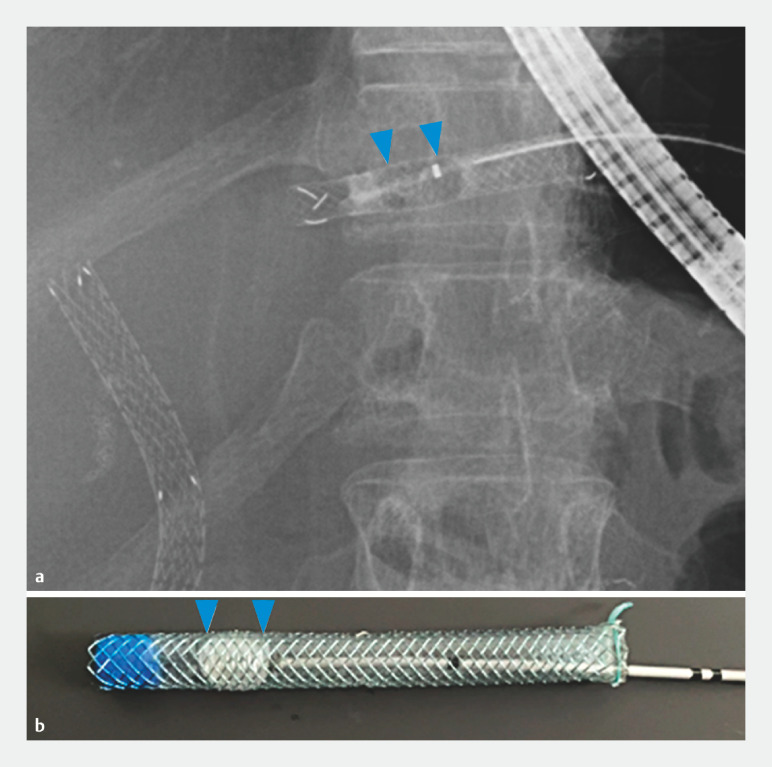

Fig. 3.

A stone extraction balloon (Fusion Extraction Balloon; Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, United States) was inflated inside the partially covered metal stent to allow passage of the guidewire through the center of the stent ( a fluoroscopic view, b. diagram).

Fig. 4.

In a “piercing technique,” the stiff back end of a 0.035-inch guidewire (Jagwire; Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts, United States) was used, which enabled the smooth advancement of the guidewire beyond the hyperplasia at the proximal end of the stent ( a fluoroscopic view, b diagram).

Fig. 5.

A dedicated 7F × 14-cm plastic stent (TYPE-IT Stent; Gadelius Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was successfully deployed through the existing partially covered metal stent ( a fluoroscopic view, b endoscopic view).

Endoscopic reintervention using a “piercing technique” for mucosal hyperplasia after endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy.

Video 1

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Minaga K, Kitano M. Recent advances in endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:38–47. doi: 10.1111/den.12910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakai Y, Sato T, Hakuta R et al. Long-term outcomes of a long, partially covered metal stent for EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy in patients with malignant biliary obstruction (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.3856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minaga K, Kitano M, Uenoyama Y et al. Feasibility and efficacy of endoscopic reintervention after covered metal stent placement for EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy: A multicenter experience. Endosc Ultrasound. 2022;11:478–486. doi: 10.4103/EUS-D-22-00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsubara S, Nakagawa K, Suda K et al. Radiofrequency ablation of hyperplasia at an uncovered portion of a partially covered metal stent in endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy (with video) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2021;28:e32–e33. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toyonaga H, Hayashi T, Katanuma A. Piercing technique via cholangioscopy for the reconstruction of complete anastomotic obstruction after choledochojejunostomy. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:e86–e88. doi: 10.1111/den.13664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]