Abstract

Objective

Despite recognized benefits, engagement in Advance Care Planning (ACP) remains low. Research into peer-facilitated, group ACP interventions is limited. This study investigated the acceptability of community-led peer-facilitated ACP workshops for the public and whether these workshops are associated with increased knowledge, motivation and engagement in ACP behaviors.

Methods

Peer-facilitators from 9 community organizations were recruited and trained to deliver free ACP workshops to members of the public with an emphasis on conversation. Using a cohort design, workshop acceptability and engagement in ACP behaviors was assessed by surveying public participants at the end of the workshop and 4–6 weeks later.

Results

217 participants returned post-workshop questionnaires, and 69 returned follow-up questionnaires. Over 90% of participants felt they gained knowledge across all 6 learning goals. Every ACP behavior saw a statistically significant increase in participant completion after 4–6 weeks. Almost all participants were glad they attended (94%) and would recommend the workshop to others (95%).

Conclusion

This study revealed an association of peer-facilitated ACP workshops and completion of ACP behaviors in public participants.

Innovation

This innovative approach supports investment in the spread of community-based, peer-facilitated ACP workshops for the public as important ACP promotion strategies.

Keywords: Advance Care Planning, Community-based participatory research, Community networks, Hospices

Highlights

-

•

Public engagement in Advance Care Planning (ACP) has documented benefits, but engagement remains low.

-

•

Limited in healthcare provider time and competing priorities are barriers for effective and sustainable ACP interventions.

-

•

Community organizations could play a role to ease the burden on healthcare providers.but research is limited.

-

•

This study investigates the acceptability of community-based, peer-facilitated ACP workshops for the public.

-

•

These workshops were acceptable to public participants, prompted significant increases in completion of ACP behaviors.

1. Introduction

Advance Care Planning (ACP) is a process that supports adults to understand and share their personal values, goals and preferences to ensure that future medical care is congruent with them [1]. It can decrease patient and family anxiety, as well as unwanted medical treatments and hospital deaths [2]. Despite recognition of the importance of ACP, healthcare providers (HCP) often don't discuss ACP with patients as often or fully as they would like [3], and public engagement remains low. There is a need to address these barriers, as well as to support ACP strategies that engage the public through non-healthcare, community-oriented approaches [4].

ACP education by non-healthcare community members has many potential benefits, including the potential to tailor the education to minority populations [5], normalize ACP [6], and save the healthcare system money [7,8]. Furthermore, information or advice may be more readily accepted from those who are of similar age or experience [9,10], or from those who are already practicing the new behaviors [9]. Non-healthcare educators may also be seen as less threatening than healthcare professionals [9].

ACP education is considered a core service by many hospice societies across Canada [11,12] and is also offered by other types of community organizations [13]. Education may be delivered one-on-one or in a group. The training given to peer leaders varies, as does the content of the sessions or interactions.

Involvement of peers in direct facilitation of ACP conversations has been well documented [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]], and group medical visits have shown efficacy in promoting ACP engagement [[23], [24], [25]]. Research into peer-facilitated group ACP activities is limited but promising. One recent study showed that peer-facilitated ACP sessions for university students increased ACP completion rates, [26], and another showed that sessions facilitated by patient navigators increased readiness to engage in ACP, [10,27] although around half of these sessions were co-facilitated by clinicians. However, it is largely unknown how peer-facilitated ACP sessions are accepted, and whether they result in greater completion of ACP by the public [28].

Given the advantages associated with peer-facilitated ACP, as well as the considerable resources currently invested in it by community organizations, it is important to determine the impact of these programs on the public's ACP behaviors. Our study seeks to evaluate the acceptability of peer-facilitated ACP workshops for members of the public, and whether these workshops are associated with increased knowledge, motivation and engagement in ACP behaviors.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

We used a training curriculum and toolkit of resources co-developed by the BC Centre for Palliative Care (BCCPC) and two community organizations to train and support volunteers and staff members from community organizations to facilitate ACP workshops. Briefly, the workshop content included consideration of the What, Why, Who, When and How of ACP, with the How organized under three steps of Think, Talk and Plan. The toolkit of resources included resources for the hosting organization, a facilitator guide and schematic outlining the key workshop content, and a public handout summarizing the information covered in the workshop. The training curriculum for the peer facilitators included a one-day training workshop (delivered by a subject matter expert in group facilitation and ACP), online learning about ACP, and ongoing coaching and mentoring from subject matter experts. Collectively, the training curriculum, the toolkit and the structure of the workshops aim to enhance public awareness, knowledge, motivation and engagement in relation to ACP. The study was approved by the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board (H15–03335). This paper follows the STROBE reporting guidelines [29].

2.2. Organization/peer-facilitator recruitment

Community organizations in British Columbia that participated in the training described above and planning to host peer-facilitated ACP workshops in their own organizations during the study period were invited to participate in the research study. Some of these organizations received Seed Grants from BCCPC to host these workshops. Nine organizations self-selected based on interest, seven of which were hospice societies. Organizations selected two to three volunteers or staff for the peer-facilitator role using provided selection criteria, including experience facilitating groups, familiarity with and passion for ACP, and an agreement to follow the provided curriculum and toolkit.

2.3. ACP workshops

ACP workshops led by trained peer-facilitators were conducted between September and December of 2016. Workshops were openly advertised according to individual organizations' marketing plans and were offered free of charge to the public.

2.4. Questionnaires

Post-workshop questionnaires were administered to attendees immediately after the workshop. The questionnaire asked about: participant demographics; their understanding of key ACP terminology; whether they had already completed or planned to complete any of the 13 listed ACP behaviors (see Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 or Appendix A); and about attendees' experiences of the workshop. The questionnaire was developed specifically for this study. The list of ACP behaviors were based on the curriculum of the workshops, to be behaviors we anticipated people potentially completing after the workshop. The questions asked about each behavior aimed to address self-efficacy and readiness focused on behavior change. Consent was requested to contact the attendees for a follow-up questionnaire four to six weeks later.

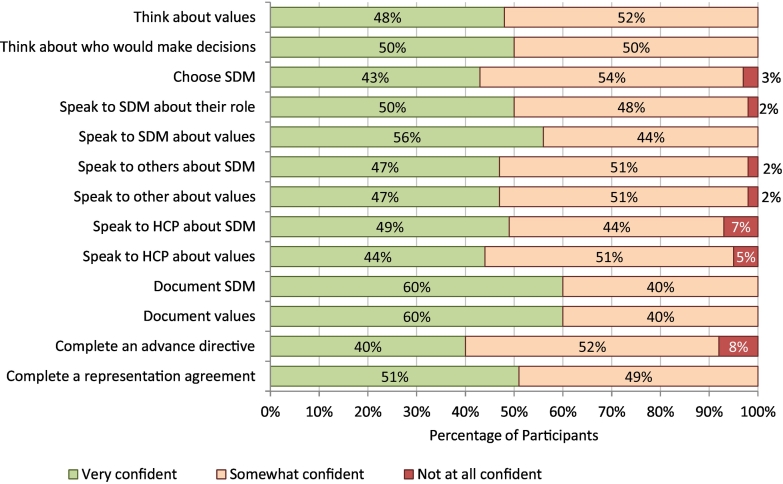

Fig. 2.

Participant confidence in ability to complete ACP behaviors (immediately post-workshop).

Abbreviations: ACP = Advance Care Planning; SDM = Substitute Decision Maker; HCP = Healthcare provider.

Fig. 3.

Number of participants who plan to complete ACP behaviors after workshop.

Abbreviations: ACP = Advance Care Planning; SDM = Substitute Decision Maker; HCP = Healthcare provider.

Fig. 4.

Number of participants having completed ACP behaviors prior to workshop and 4–6 weeks after.

Abbreviations: ACP = Advance Care Planning; SDM = Substitute Decision Maker; HCP = Healthcare provider. P values based on Fisher's exact test comparing those who had completed behavior prior to workshop with those who had completed behavior at follow-up.

Follow-up questionnaires were administered to consenting workshop attendees four to six weeks after their workshop attendance by a member of the research team (AH). Attendees were asked via phone, email or mail (based on their preference) whether they had completed any of the 13 listed ACP behaviors.

Full questionnaires are provided in Appendix A.

2.5. Confidentiality

Attendees were assigned a unique code at the time of post-workshop questionnaire completion to facilitate data anonymization during the comparison of post-workshop and follow-up questionnaires.

2.6. Analysis

Since many of the follow-up questionnaires were returned incomplete (42 of 69), a pairwise deletion method was chosen to make the fullest use of the dataset – for each ACP behavior only participants who had responded in both questionnaires were included. Analysis of the missing data revealed that the post-session questionnaire questions referencing ‘planning’ or ‘confidence’ in completing a behavior were more likely to be missing if a participant had completed that behavior in the past. We therefore analyzed planning and confidence using data only from participants who had not completed the behavior prior to the workshop.

Data were analyzed using SPSS v26. We used a Fischer Exact test to assess: changes in ACP behaviors between the post-workshop questionnaire and the follow-up questionnaire; and association between confidence and completion. A p-value of 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

3. Results

Nine different community organizations hosted a total of 28 workshops, led by 23 peer-facilitators and attended by 302 workshop attendees (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram describing numbers of participants and returned surveys.

3.1. Participant and workshop characteristics

The median workshop length was 90 min, and the mean participant age was 66.4 years (SD 11.4). Most workshop participants identified as female (74%), considered their health to be ‘good’ or ‘very good’ (72%), and were attending the workshop to learn more about ACP for themselves (70%)(Table 1).

Table 1.

Workshop and participant characteristics.

| Workshops (N = 28) | Min-Max (Median) |

|---|---|

| Workshop Length (minutes) | 60–120 (90) |

| Number of attendees per workshop | 2–29 (7.5) |

| Participant Demographics | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (N = 68) | 66.4 (11.4) |

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Female gender (N = 69) | 51 (74) |

| Living Arrangement (N = 69) | |

| My own home | 65 (94) |

| Retirement residence | 2 (3) |

| Other | 2 (3) |

| Health (N = 67) | |

| Excellent | 14 (21) |

| Very good | 28 (42) |

| Good | 20 (30) |

| Fair | 3 (5) |

| Poor | 2 (3) |

| Hospital admission in past year (N = 68) | 9 (13) |

| Education (N = 69) | |

| Less than high school diploma | 5 (7) |

| High school diploma | 9 (13) |

| College/tech/trade certificate or diploma | 24 (35) |

| Bachelor's degree | 17 (25) |

| Graduate degree | 14 (20) |

| Reason attended workshop (N = 69) | |

| Learn about ACP for myself | 48 (70) |

| Learn about ACP for someone else | 8 (12) |

| Both | 12 (17) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Attended other ACP workshop previously (N = 69) | 10 (15) |

Abbreviations: ACP = Advance Care Planning.

The majority of the trained peer facilitators were female (76%) and almost all fell in the 40–70 age groups (41–50 23.4%; 51–60 29.8%; 61–70 38.3%)(Personal Communication, E. Hassan). This aligns with the age and gender characteristics of the public participants who attended the workshops.

3.2. Overall workshop experience and change in ACP knowledge

Over 90% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the workshop was well organized and effectively guided. Almost all participants were glad that they had attended and would recommend the workshop to others (94% and 95% respectively). Similarly, over 90% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the ACP workshop increased their knowledge across all six learning goals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants' consensus on workshop learning and facilitation.

| Agree/ Strongly agree N (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Today's session has increased my knowledge about: | |

| When I should start thinking about and sharing what matters most to me regarding my future healthcare (N = 68) | 65 (95) |

| Who I can speak to about what matters most to me regarding my future healthcare (N = 68) | 63 (93) |

| My options for documenting my wishes or instructions regarding my future healthcare (N = 68) | 66 (97) |

| Who I would want to make healthcare decisions for me if I am unable to make them myself (N = 68) | 61 (90) |

| The overall ACP process (N = 68) | 65 (95) |

| What I should do with my written advance care plan (N = 68) | 62 (91) |

| The facilitators are knowledgeable about ACP (N = 66) | 62 (94) |

| The information presented was clear and organized (N = 66) | 61 (92) |

| The facilitators discussed ACP in a thoughtful and sensitive way (N = 66) | 62 (94) |

| The facilitators effectively guided the session (N = 66) | 61 (92) |

| I'm glad that I came to today's session (N = 66) | 62 (94) |

| I would recommend the session to others (N = 66) | 63 (95) |

Abbreviations: ACP = Advance Care Planning.

3.3. Confidence in ability to complete ACP behaviors and intent to complete ACP behaviors

Between 40 and 60% of those who had not completed an ACP behavior prior to the workshop indicated that they felt ‘very confident’ in their ability to complete the behavior after the workshop. Participants were most confident with documenting their values and documenting their substitute decision maker (SDM), and were least confident with completing an advance directive and speaking to HCP about their values (Fig. 2).

For the participants who had not completed the behavior prior to attending the workshop, the proportion of participants reporting that they planned to complete ACP behaviors following the workshop, were high, ranging from 100% for ‘thinking about who would make decisions’ to 63% for ‘completing an advance directive’ (Fig. 3).

3.4. Completion of ACP behaviors

The ACP behaviors most frequently completed prior to the workshop were ‘think about who would make decisions’ and ‘think about values’; both had already been completed by over half of participants (64% and 56% respectively). The least frequent behaviors completed prior to the workshop were ‘speak to HCPs about values’ and ‘complete an advance directive’ (both 6%). See Fig. 4 for summary and comparison statistics for the post-workshop and follow-up questionnaires.

Every ACP behavior saw a statistically significant increase in participant completion at follow-up compared to immediately post-workshop. The most frequently performed behaviors post-workshop remained the most frequently performed behaviors at follow-up. The behaviors with higher absolute percentage increases were those that involved self-reflection or speaking with their SDM or others. The behaviors with lower absolute percentage increases were those that involved formally documenting decisions or speaking to HCPs (Fig. 4).

Whether or not a participant expressed confidence in a behavior correlated with whether they completed it for only select behaviors: ‘choose substitute decision maker’ (p = 0.041), ‘speak to HCP about substitute decision maker’ (p = 0.008), ‘complete an Advance Directive’ (p = 0.008) and ‘complete a Representation Agreement’ (p = 0.044)(Fig. 2, Fig. 4).

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

We conclude that the workshops are acceptable to participants, and attendance was associated with short term increases in knowledge and motivation, and increased engagement in ACP behaviors at 4–6 weeks by participants. Acceptability was confirmed by over 90% of participants agreeing that workshops were well organized, effectively guided, that they were glad they attended, and that they would recommend the workshop to others. A short-term increase in ACP knowledge is supported by over 90% of participants reporting the workshop increased their ACP knowledge. Similarly, short-term motivation to complete ACP behaviors is confirmed by high rates of participants reporting that they plan to engage in ACP behaviors, in particular over 90% of participants reported that they planned to engage in behaviors associated with self-reflection or speaking with their substitute decision maker.

We observed statistically significant increases in all measured ACP behaviors for workshop participants four to six weeks after the ACP session, demonstrating effectiveness of these peer-facilitated ACP workshop in affecting behavior change in participants. Self-reflection about ACP and discussion with family and close friends about ACP increased considerably at follow-up (20–37%), while formal documentation of ACP and conversations with HCPs had lower rates of increase (3–12%). This is unsurprising, as the curriculum of our workshops focuses on conversations rather than document completion.

Our findings are largely consistent with Barrison et al., who studied the impact of six-hour peer-facilitated ACP workshops on college-aged students [26]. In a follow-up questionnaire at two weeks, they noted similar trends of completion despite the considerably longer workshop time, with rates of ACP conversations with non-HCPs increasing more than rates of ACP documentation (33% and 11% increase respectively). Conversely, Fink et al.'s [10] investigation of a 1-h ACP session facilitated by patient navigators observed a markedly lower proportion of participants planning to complete ACP behaviors following the session than we observed. While comparison is difficult due to differences in follow-up time as well as length of session, readiness to engage in various ACP behaviors ranged from 14 to 31% for Fink et al., compared to 63–100% for our study participants.

While there have been few studies comparing peer-facilitated to expert-facilitated education, a 2012 meta-analysis of these strategies in medical education suggests that peer-facilitation is non-inferior to expert-facilitated education in at least some areas [30]. Our results similarly suggest that peer-facilitated workshops may be comparable to HCP-facilitated ACP workshops. For instance, Lee et al. studied the impact of hour-long, nurse-facilitated ACP workshop on Chinese-American adults, and one month following the session found similar rates of increase for having an ACP conversation (36% for Lee vs 37% here) [31]. Bravo et al. also considered the impact of HCP-facilitated ACP sessions on participant behaviors; however, their intervention was more intensive, and enrolled older adult and SDMs dyads into a program of three workshops [32]. While they reported a 50% absolute increase in documentation by the end of the program, the authors noted the considerable resources required to run the workshops, including the employment of trained social workers.

Overall, due to differences in outcomes measures, workshop design and delivery, and target population, direct comparisons between the impacts of peer-facilitated and HCP-facilitated ACP workshop are difficult. In particular, the heterogeneity of outcomes may reflect discrepant conceptualizations of ACP and different priorities of the workshops. For instance, the primary goal of our ACP workshop was to foster increased ACP conversations, whereas others do not include increased conversations as an outcome measure or include these as a secondary outcome [32,33].

Community-led ACP workshops may have several potential benefits in addition to increases in ACP actions, including the normalization of ACP conversations in the community, the ability to integrate it earlier into people's lives, and reduced costs and time-demands on healthcare systems [4,6,34]. Furthermore, the low costs and resource requirements for running these programs means they have potential to be a sustainable model. Ideally, community organizations and healthcare systems would work together to coordinate emphasis and components of ACP education in a way that makes the most effective use of everyone's expertise and time.

While most participants planned to complete all ACP behaviors, actual rates of completion varied considerably. It is common for people to say they plan do something and not follow through, but beyond that, the relatively short follow-up period of four to six weeks may have been too short a time to complete some activities, such as scheduling and attending an appointment with a HCP. Additionally, since the least-completed behaviors both before and after the workshop were those involving speaking to a HCP or completing a form, factors such as convenience or a discomfort with the healthcare system may have impacted participants' behaviors. Finally, since the ACP workshops were designed to prioritize conversation over documentation, this may have impacted the rates of completion of other behaviors.

Our study population differs from the older BC population with regards to ACP engagement, but is representative of who we expect would attend these workshops in a real-world setting given the general nature of the recruitment approach and materials. When compared to a 2020 survey of the general British Columbian population,[E Hassan, personal communication] our participants had lower pre-workshop levels of speaking to a HCP about ACP (12% vs 24% respectively) and having documented ACP (12% vs 28% respectively). This is not unexpected; we would anticipate those choosing to attend the workshops to have lower ACP engagement than the general population. Our participants skewing towards female (74%) is unsurprising, as men and women engage with ACP differently [35]. While our data indicate that the workshops were acceptable to and associated with desired outcomes for those participants that attended, there is further work required to adapt the recruitment approaches to broaden the demographics of attendees, and to evaluate and adapt the workshops to ensure that the content is suitable for those groups also.

Another limitation of our study was the low rate of participant willingness to be contacted after the workshop, with only 23% (N = 69) of total participants completing a follow-up questionnaire, leading to potential for bias. Furthermore, as mentioned previously, the four-to-six-week timeframe for follow-up questionnaire return may have been too early to capture the true impact of the workshop on more involved behaviors, such as speaking with a HCP. Finally, we did not assess the fidelity of the workshops hosted by the peer-facilitators. While the peer-facilitators were asked to, and agreed to, follow the workshop materials as provided, we do not know for certain how closely the peer-facilitators adhered to the curriculum and materials. However, fidelity is reported to be high when participants know they are being observed (Hawthorne effect). These facilitators knew that they were in this study.

Our study adds to the increasing body of literature supporting the value of peer-facilitated ACP workshops and demonstrates that the methodology is appropriate for evaluation of the workshops. Further work is needed to determine how workshops and associated recruitment might be adapted to maximize their acceptability and impact among different population groups, including traditionally underserved populations – these workshops were delivered in English, so required participants to be conversant in English. Similarly, understanding how best to link this community-based approach with healthcare providers and the healthcare system would likely increase the impact of these programs. As this study only assessed increased ACP knowledge and motivation immediately following the workshop, we are unable to conclude whether this increased knowledge was maintained over time, it may be useful to investigate whether this was maintained in the long term. Also beneficial would be a direct comparison of HCP-facilitated ACP education to peer-facilitated workshops, from an effectiveness and a financial standpoint.

4.2. Innovation

Traditionally ACP interventions have been delivered by healthcare providers or within the healthcare system. The approach investigated in this paper is innovative in that it shifts this into the community/public arena. The project also reports on a bottom-up approach of innovation, where community organizations initially identified the need for the intervention, and our role was as a convenor to facilitate the spread and evaluation of the innovation.

4.3. Conclusion

This study shows that this community-led, peer-facilitated education approach is associated with short-term enhancement in ACP knowledge, motivation and confidence to engage in ACP, and increased completion rates of ACP behaviors in public participants.

Our findings affirm the value of putting resources towards planning and running peer-facilitated ACP workshops, and make a case for the continued and increased support for these workshops, as they could potentially decrease the burden of ACP education on the healthcare system.

Funding

The study was funded by the Canadian Frailty Network (formerly TVN) which is supported by the Government of Canada through the Networks of Centres of Excellence program. Opinions are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement from the funding sources.

Author contributions

CRediT: RZC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Project Administration, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. ES: Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft. AH: Data Curation, Formal Analysis. DB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition. SS: Writing – Review & Editing. JK: Conceptualization, Methodology. RS: Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing. AK: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing. KS: Writing – Review & Editing. EH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participating organizations and peer-facilitators that hosted the public workshop included in this study.

Preliminary analysis of this data was presented at conferences: 22nd International Congress on Palliative Care 2018 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.004), British Columbia Patient Safety Quality Council Quality Forum 2018, Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association Conference 2017, Advance Care Planning and End of Life Care Society Conference 2017, Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement CEO Forum 2017, Canadian Frailty Network Conference 2017.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2023.100199.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material 1: Post-Advance Care Planning Workshop Questionnaire for Attendees

Supplementary material 2: Follow-Up Questionnaire for ACP Session Attendees (4-6 Weeks)

References

- 1.Sudore R.L., Lum H.D., You J.J., Hanson L.C., Meier D.E., Pantilat S.Z., et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:821–832.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahan R.D., Tellez I., Sudore R.L. Deconstructing the complexities of advance care planning outcomes: what do we know and where do we go? A Scoping Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:234–244. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard M., Bernard C., Klein D., Elston D., Tan A., Slaven M., et al. Barriers to and enablers of advance care planning with patients in primary care: survey of health care providers. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:e190–e198. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29650621 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waller A., Sanson-Fisher R., Ries N., Bryant J. Increasing advance personal planning: the need for action at the community level. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:606. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5523-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phipps E.J., True G., Murray G.F. Community perspectives on advance care planning: report from the community ethics program. J Cult Divers. 2003;10:118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biondo P.D., King S., Minhas B., Fassbender K., Simon J.E. How to increase public participation in advance care planning: findings from a world Café to elicit community group perspectives. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:679. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7034-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rocque G.B., Dionne-Odom J.N., Sylvia Huang C.-H., Niranjan S.J., Williams C.P., Jackson B.E., et al. Implementation and impact of patient lay navigator-led advance care planning conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biondo P.D., King S., Minhas B., Fassbender K., Simon J.E. How to increase public participation in advance care planning: findings from a world Café to elicit community group perspectives. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:679. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7034-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peel N.M., Warburton J. Using senior volunteers as peer educators: what is the evidence of effectiveness in falls prevention? Australas J Ageing. 2009;28:7–11. doi: 10.1111/J.1741-6612.2008.00320.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fink R.M., Kline D.M., Bailey F.A., Handel D.L., Jordan S.R., Lum H.D., et al. Community-based conversations about advance care planning for underserved populations using lay patient navigators. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:907–914. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gyapay J., Freeman S., Flood D. An environmental scan of caregiver support resources provided by hospice organizations. J Palliat Care. 2020;35:135–142. doi: 10.1177/0825859719883841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association Advance Care Planning in Canada. 2021. https://www.chpca.ca/projects/advance-care-planning/ (accessed March 7, 2021)

- 13.Siden E.G., Carter R.Z., Barwich D., Hassan E. Part of the solution: a survey of community organisation perspectives on barriers and facilitating actions to advance care planning in British Columbia, Canada. Health Expect. 2022;25:345–354. doi: 10.1111/hex.13390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Candrian C., Lasker Hertz S., Matlock D., Flanagan L., Tate C., Kutner J.S., et al. Development of a community advance care planning guides program and the RELATE model of communication. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2020;37:5–11. doi: 10.1177/1049909119846116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson J.C., Hayden T., Taylor L.A., Gilbert A., Mitchell M.P.H. LIGHT: a church-based curriculum for training African American lay Health workers to support advance care planning and end-of-life decision-making. Health Equity. 2020;4:533. doi: 10.1089/HEQ.2020.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews H.F., Larson K.L., Hupp T., Estrada M., Carpenter M.P. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on a community-based, palliative care lay advisor project for Latinos with Cancer. Hum Organ. 2022;81:229–239. doi: 10.17730/1938-3525-81.3.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niranjan S.J., Huang C.-H.S., Dionne-Odom J.N., Halilova K.I., Pisu M., Drentea P., et al. Lay patient Navigators’ perspectives of barriers, facilitators and training needs in initiating advance care planning conversations with older patients with Cancer. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:70–78. doi: 10.1177/0825859718757131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocque G.B., Dionne-Odom J.N., Huang C.-H.H. Sylvia, Niranjan S.J., Williams C.P., Jackson B.E., et al. Implementation and impact of patient lay navigator-led advance care planning conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagwood D.N., Larson K.L. Planting the seeds: the role of Latino lay Health advisors in end-of-life care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2019;21:223–228. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel M.I., Khateeb S., Coker T. Lay Health Workers’ Perspectives on delivery of advance care planning and symptom screening among adults with Cancer: a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2021;38:1202–1211. doi: 10.1177/1049909120977841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones P., Heaps K., Rattigan C., Marks-Maran D. Service improvement advance care planning in a UK hospice: the experiences of trained volunteers. Eur J Palliat Care. 2015;22:144–151. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson J., Hayden T., Taylor L.A. Evaluation of the LIGHT curriculum: an African American church-based curriculum for training lay Health workers to support advance care planning, end-of-life decision making, and care. J Palliat Med. 2022;25:413–420. doi: 10.1089/JPM.2021.0235/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/JPM.2021.0235_FIGURE1.JPEG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lum H.D., Sudore R.L., Matlock D.D., Juarez-Colunga E., Jones J., Nowels M., et al. A group visit initiative improves advance care planning documentation among older adults in primary care, the. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:480–490. doi: 10.3122/JABFM.2017.04.170036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lum H.D., Dukes J., Daddato A.E., Juarez-Colunga E., Shanbhag P., Kutner J.S., et al. Effectiveness of advance care planning group visits among older adults in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2382–2389. doi: 10.1111/JGS.16694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuda S., Janevic M.R., Shikano K., Matsui T., Tsuda T. Group-based educational intervention for advance care planning in primary care: a quasi-experimental study in Japan. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2020;18 doi: 10.22146/APFM.V18I1.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrison P., Davidson L.G. Promotion of advance care planning among young adults: a pilot study of Health engagement workshop feasibility, implementation, and efficacy. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2021;38:441–447. doi: 10.1177/1049909120951161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fink R.M., Kline D.M., Siler S., Fischer S.M. Apoyo con Cariño: a qualitative analysis of a palliative care-focused lay patient navigation intervention for Hispanics with advanced Cancer. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22:335–346. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sellars M., Simpson J., Kelly H., Chung O., Nolte L., Tran J., et al. Volunteer involvement in advance care planning: a scoping review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57:1166–1175.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. STROBE initiative, strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rees E.L., Quinn P.J., Davies B., Fotheringham V. How does peer teaching compare to faculty teaching? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Teach. 2016;38:829–837. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1112888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee M.C., Hinderer K.A., Friedmann E. Engaging Chinese American adults in advance care planning: a community-based, culturally sensitive seminar. J Gerontol Nurs. 2015;41:17–21. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20150406-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bravo G., Trottier L., Arcand M., Boire-Lavigne A.-M., Blanchette D., Dubois M.-F., et al. Promoting advance care planning among community-based older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:1785–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson N., Luptak M.K., Boult C. A method for increasing Elders’ use of advance directives. Gerontologist. 1994;34:409–412. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prince-Paul M., DiFranco E. Upstreaming and normalizing advance care planning conversations—a public Health approach. Behav Sci. 2017;7:18. doi: 10.3390/bs7020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perkins H.S., Cortez J.D., Hazuda H.P. Advance care planning: does patient gender make a difference? Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1: Post-Advance Care Planning Workshop Questionnaire for Attendees

Supplementary material 2: Follow-Up Questionnaire for ACP Session Attendees (4-6 Weeks)