Abstract

The interface tissue between bone and soft tissues, such as tendon and ligament (TL), is highly prone to injury. Although different biomaterials have been developed for TL regeneration, few address the challenges of the TL-bone interface. Here, we aim to develop novel hybrid nanocomposites based on poly(p-dioxanone) (PDO), poly(lactide-co-caprolactone) (LCL), and hydroxyapatite (HA) nanoparticles suitable for TL-bone interface repair. Nanocomposites, containing 3–10% of both unmodified and chemically modified hydroxyapatite (mHA) with a silane coupling agent. We then explored biocompatibility through in vitro and in vivo studies using a subcutaneous mouse model. Through different characterisation tests, we found that mHA increases tensile properties, creates rougher surfaces, and reduces crystallinity and hydrophilicity. Morphological observations indicate that mHA nanoparticles are attracted by PDO rather than LCL phase, resulting in a higher degradation rate for mHA group. We found that adding the 5% of nanoparticles gives a balance between the properties. In vitro experiments show that osteoblasts' activities are more affected by increasing the nanoparticle content compared with fibroblasts. Animal studies indicate that both HA and mHA nanoparticles (10%) can reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines after six weeks of implantation. In summary, this work highlights the potential of PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites as an excellent biomaterial for TL-bone interface tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: Tendon enthesis, Interface tissue, Nanocomposites, Hydroxyapatite, Silane modification

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Native tendons/ligaments (TL) have excellent tensile strength and toughness enabling them to perform daily operations of regular movement to intense physical activity. TL are connected to bone via calcified and non-calcified fibrocartilage regions (junction tissue) and transmit loads between bones, and between bone and muscle [1]. As they experience significant loads and extension, these regions are prone to failure, thus requiring repair. Currently available artificial TL grafts are mostly based on non-absorbable polymers, like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polypropylene (PP), resulting in permanent implantation at the injury site. Moreover, these grafts cannot truly recapitulate the complex biocomposition and gradient physical properties of bone-tendon/ligament junctions [2]. Therefore, in order to create scaffolds that mimic the native interface, mineralised biocomposites with engineered tensile properties, toughness and degradation rate must be designed.

To date, many different biomaterials have been developed for TL tissue engineering; however, few are designed for TL interfaces [1,3,4]. For instance, Kolluru et al. [5] fabricated poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA, 85:15 lactide/glycolide) nanofibres mineralised for tendon-to-bone scaffolds, demonstrating high yield strength (up to ∼60 MPa) and toughening behaviour when stretched uniaxially. Although the degradation rate of the nanofibres was investigated, PLGA (85:15) normally degrades more than 50% over 2 months [[6], [7], [8]]. This may result in early-stage mechanical failure of the scaffolds since most native TL, like anterior cruciate ligaments (ACL), need 6–18 months for functional regeneration [9,10]. Erisken et al. [11] developed poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) nanofibre scaffolds with a gradient tricalcium phosphate (TCP) to mimic the compositional and structural characteristics of the tendon-to-bone interface. Hence, the preparation of biocompatible nanocomposites based on minerals and biopolymers is a successful approach towards developing an advanced scaffold for TL tissue engineering.

The regeneration of mineralised tissues, like bone, has been integrated with many different biomaterials. For instance, toughened bone composite implants have been developed by using carbon nanofibers, polyvinyl alcohol fibre, polymethylmethacrylate nano-Fe2O3 modification, etc [[12], [13], [14]]. Furthermore, the toughened composite implants can be fabricated by using 3D printing techniques in order to control pore structure, composition gradient, and mechanical strength for bone tissue engineering [[15], [16], [17]]. Hydroxyapatite (HA) is one of the most widely used bioactive minerals in the field of biomaterials and tissue engineering because it is a major mineral component of the bone matrix [18]. For instance, magnesium-doped HA/collagen composite has indicated osteoinductive potential in a rabbit orthotopic model [19]. The incorporation of HA not only induced nanomechanical properties during the mineral in vitro study, but also contributed to modulating the expression of early and late osteogenic marker genes (Spp1, Sparc, Col1a1, Runx2, Dlx5). Bone histomorphometry at 6 weeks revealed a significant amount of de novo bone matrix formation in a rabbit model [19]. Recently, the oriented microcellulose fibres containing nano-hydroxyapatite is prepared by mimicking the extracellular matrix of bone tissue [20]. The nano-hydroxyapatite was deposited on the surface of cellulose fibres, and then the magnetic nanoparticles on the cellulose fibres were aligned on the surface of chitosan under a magnetic field. The oriented microcellulose fibres promoted the high expression of collagen type I, and consequently, formed new blood vessels [20].

In the last decade, HA-based nanocomposites and synthetic biopolymers have also been developed for bone tissue engineering [21]. The addition of HA to synthetic biopolymers not only improves biocompatibility and regenerative properties, but also enhances the strength and elastic modulus of the nanocomposites [22]. Furthermore, the incorporation of HA nanoparticles (nHA) into the biopolymers can significantly affect other properties of a polymer matrix, depending on different factors like the nanoparticle type, concentration and its interaction with the polymer matrix [23,24]. HA nanoparticles have a strong tendency to undergo agglomeration, particularly in high concentrations, due to their specific surface area and the high affinity in particle-particle interactions. This problem can be overcome by modification of the HA nanoparticle surface using silane coupling agents. This modification improves the interfacial interactions between the nanoparticles and the polymer matrix [24]; and this development has attracted a great deal of attention [[25], [26], [27], [28]]. For instance, HA nanoparticles were modified by γ-methacryloxypropyl trimethoxysilane to improve the interfacial connection of HA to PLA matrix [25]. The modified HA nanoparticles resulted in a better dispersion in the polymer matrix, higher compressive modulus, and protein adsorption compared to unmodified HA [25]. The improved mechanical properties could be due to the complex interaction between modified HA and PLA matrix, such as dipole-dipole interaction, hydrogen bonding, structural interaction of semi-IPN (inter-penetrate-net) between the chemical groups on HA surface and terminal groups, carboxylic groups or hydroxyl groups of polymer matrix [29]. Qi et al. [30] reported that HA nanoparticles modified with γ-aminopropyl triethoxysilane and ethenyl trimethoxysilane enhance the toughness, tensile and bending strength of PLGA/PTMC (poly (trimethylene carbonate)) blends compared to unmodified HA. While the silane modification improved interfacial adhesion by reducing the gap at interface between nanoparticles and polymer matrix, few agglomerates still occurred in the nanocomposites after modification [30]. A similar observation was reported for PLA composites containing silane-modified carbonated hydroxyapatite [31]. The improved interfacial interaction between silane-modified HA and polymer matrix was also reported for other nanocomposites based on poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [28], high-density polyethylene (HDPE) [27], and polyether ether ketone (PEEK) [32].

Recently, we developed biocompatible blends based on poly(p-dioxanone) (PDO) and poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) (LCL) copolymer, with mid-term degradation rate, enhanced toughness and high elongation at break; we proposed that PDO/LCL might be suitable for TL scaffolds or suture applications [33]. The blend containing a minority of PDO (e.g. 30%) can result in small immiscible PDO droplets uniformly dispersed within the LCL matrix and demonstrated great in vitro cellular properties and tensile properties, suiting native TL [33]. In this work, we aim to tailor the properties of PDO/LCL blend by adding HA and modified HA nanoparticles for TL interface tissue engineering applications. PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites are characterised by a range of different imaging and mechanical testing techniques and studied for biocompatibility in both in vitro and in vivo experiments to investigate the effect of HA type (modification) and concentration on the PDO/LCL blend.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Surface modification of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles

Surface modification of HA nanoparticles (average particle size (BET) < 200 nm, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was carried out using 3-methacryloxypropyl-trimethoxysilane (MPTS, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) silane coupling agent. To ensure uniform coverage of the HA surface, silane coupling agent was applied from an aqueous alcohol solution according to a well-known protocol [26,34]. A 1.0 vol% of MPTS solution was arranged using a pre-prepared solvent mixture of 90 vol% ethanol and 10 vol% water. The pH of the solvent mixture was adjusted to 4.0 by 3.0 M acetic acid. The silane solution was stirred and allowed to hydrolyze (activate) for 1 h. Nano-HA powder was added and dispersed by ultra-sonication probe (CY-USP-600N, Zhengzhou CY Scientific Instrument Ltd) with the set power at 20% (equal to 120W) for 15 min. Then, the reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h at room temperature. After the reaction, the modified HA (mHA) powders were separated by centrifugation and rinsed with absolute ethanol to remove physically adsorbed silanes. The powder was dried overnight at room temperature and then dried at 60 °C in an oven for 72 h to enhance the condensation of surface silanol molecules and to remove any remaining solvent. After grinding, the powder was used to prepare the experimental resin composite. Fig. 1 demonstrates the surface modification of HA nanoparticles through the reaction of MPTS with hydroxyl groups.

Fig. 1.

Surface modification of HA nanoparticle via MPTS coupling agent.

2.2. Nanocomposite preparation

Before the preparation of PDO/LCL/nHA composites, the ratio of PDO/LCL blend was optimised. In our previous work, we showed that the P3L7 blend, containing 30% of PDO and 70% of LCL, shows enhanced toughness, high elongation at break, and mid-term degradation rate, which suits TL regeneration applications [33]. In this work, we investigated the tensile and morphological properties of similar weight ratios to P3L7, such as 35/75 (P3.5L6.5), 25/75 (P2.5L7.5), 20/80 (P2L8), and 10/90 (P1L9) in order to find the best composition for nanocomposite preparation. All blends were prepared according to the reported method in our previous study [33], which is briefly mentioned in Supplementary. The tensile properties of the blends were listed in Table S1. According to the results, P2L8 showed the highest tensile properties among the samples. The SEM images (Fig. S1) also showed that all samples possess a similar cross-section morphology (droplet-matrix) to P3L7, resulting in high elongation at break and strain-hardening behaviour in the blends [33]. Hence, P2L8 was chosen to prepare PDO/LCL/nHA composites in this work. Further discussion is provided in Supplementary.

PDO/LCL/nHA composites were prepared by a solvent casting method at room temperature. In this study, LCL copolymer (l-lactide:caprolactone 75:25; Mw = 430,000 Da; BMG Inc, Japan) and PDO (ηinh = 1.6 dL/g; BMG Inc, Japan) were used to prepare the composites. First, LCL and PDO (PDO: LCL, 2:8) were added in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) to form 10 w/v% solution (P2L8 solution) using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature. After 30 min, when the polymers are partially dissolved in HFIP solvent, 3–10 wt% of nHA were mixed with HFIP (half of the volume used for dissolving polymers) and stirred for 15 min at room temperature. Then, nHA suspension was ultrasonicated by an ultrasonic probe probe (CY-USP-600N, Zhengzhou CY Scientific Instrument Ltd) with the set power at 20% (equal to 120W) for 5 min at room temperature to improve nanoparticle dispersion uniformly inside the HFIP. Then, the suspension was added to the P2L8 polymer solution gently. The final PDO/LCL/nHA solution was stirred for 12 h at room temperature until obtaining a homogenous solution with a cream colour. Finally, the homogenous solution was then poured into a glass Petri dish and placed in a fume hood for 24 h. Residual solvent was removed by vacuum drying at 60 °C for 24 h and stored in a vacuum bag at 5 °C. Prepared composites were named P2L8-H“X” whereby “X” indicates HA fraction in the nanocomposites which contain 20 wt% of PDO and 80 wt% of LCL. The nanocomposites containing modified HA nanoparticles were named P2L8-mH“X”. Hence, the nanocomposites were named P2L8-H3, P2L8-H5, P2L8-H10 (non-modified group) and P2L8-mH3, P2L8-mH5, P2L8-mH10 (non-modified group) in this work.

2.3. Material characterisation

The functional groups of modified and non-modified hydroxyapatite powders were characterised by Infrared spectroscopy using an FTIR-ATR spectrometer (Polymer ID analysed, PerkinElmer) with a 4 cm−1 resolution in the range of 400–4000 cm−1. The powders were analysed using a Malvern Panalytical Aeris XRD Diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd, UK.) with Fe filtered Co-Kα radiation generated at 40 kV and 15 mA. The scan was from 5.0° to 80° 2θ with a step size of 0.011° 2θ. To identify crystalline phases, all patterns were matched using the database of the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) and X'pert High Score Plus software.

Morphology of the HA powders and nanocomposites, before and after degradation, was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Zeiss 1555 VP-SEM) using platinum‐coated samples at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) analysis was performed using DSC 25 (Discovery DSC Series, TA Instruments) under a nitrogen atmosphere with a heating rate of 15 °C min−1 from 20 °C to 200 °C. The melting temperatures was recorded as the maximum of the endothermic peaks. The degree of crystallinity (Xc) was taken from the first heating run and calculated using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

Where, ΔHm and Wf, respectively, are the enthalpy of melting and the weight fraction of each polymer, determined from DSC, and ΔHm° is the enthalpy of melting for 100% crystalline polymer. ΔHm° of PDO [35], PLLA [23] and PCL [23] are considered 102.9, 93 and 81.6 J g−1, respectively. Although there is no data available for melt enthalpy of PLLA-co-PCL, according to the mixture law, ΔHm° of LCL was calculated as 90.15 J g−1 based on the PLLA and PCL values.

Tensile failure properties of the composites were measured using miniaturized rectangular specimens with gauge length of 25 mm and width of 5 mm (based on type 5B in BS ISO 527: 2012) and an Instron universal tensile tester (Model 5969, Instron, HighWycombe, UK) equipped with a 500 N load cell. The toughness values were obtained by measuring the area under the stress-strain curve determined in tensile testing [36]. Average results of five test specimens (n = 5) were reported for tensile properties.

Atomic force microscope (AFM) test was performed to study the effect of nanoparticles incorporation on surface roughness and micro-topography of the composites. AFM was operated using AFM (Keysight 5500 SPM, USA) at high resolution under the contact mode. All measurements were taken at a scan rate of 1.22–2.3 lines per second at room temperature. The average roughness of the surface (Ra) was measured based on different random sites within a 10 μm × 10 μm area size. The 3D micro-topography reconstructions were obtained by Gwyddion software 2.55.

Contact angle test was performed in air atmosphere and room temperature, using Ossila contact angle goniometer, to investigate the effect of nanoparticles on the hydrophilicity of the composites. In addition, the surface energy of the blends was measured following the ASTM D7490 using diiodomethane (3.0 μL) and DI water (9.0 μL). The surface free energy (γs) of each component of composites were calculated using Owens-Wendt method by dispersive and polar surface energy (γd and γp) with a set of test liquids on a solid surface based on (2), (3):

| (2) |

| (3) |

Where s and l note the solid and liquid surfaces, respectively, and the contact angle of a liquid droplet on the surface is shown by θ [37]. By obtaining γs for all the samples, the surface energy contrast can be studied according to the composition.

The weight loss of samples was investigated during hydrolytic degradation according to ASTM F1635. Specimens with 5 × 5 × 0.3 mm3 surface area were prepared from the cast composite films. For hydrolytic degradation, the specimens were immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) at 37 °C temperature under slow shaking for 365 days (i.e. 1 year). At the designated time points, the samples (n = 3 per time point) were rinsed and gently blotted with a KimWipe® before being vacuum dried at room temperature for one day. Then, the remaining weight was measured, and the weight loss percentage was calculated based on the initial dry weight. A series of specimens were also collected for studying the degradation through SEM.

2.4. In vitro cell experiments

MTS assay was performed to quantify the number of metabolically active fibroblasts and osteoblasts grown in the media or adhered on the composites’ surfaces according to a well-known protocol [38,39]. C3H10T1/2 cells (Mouse Fibroblast Cell Line, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and MC3T3-E1 cells (Mouse Osteoblastic Cell Line, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were seeded on the surface of composites in a 48-well plate (∼5 × 103 cells/well). Cells were cultured in MEM Alpha (Gibcoä) containing 10% FBS (Gibcoä) and 1% streptomycin and penicillin mixture.

The culture plates were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. After 1, 3, and 7 days of culture, MTS assay was performed to evaluate the proliferation of cells in the media and adhered on the surface of the materials. In accordance with the CellTiter®96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, USA), MTS was added to the media at planned time points and incubated in a dark room for 2 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. To quantify the density of the attached cells, the samples were transferred to new culture wells at each culturing time. Before incubation with MTS reagent, each sample was rinsed three times with PBS. A reaction solution of 100 μL MTS/phenazine methosulfate and 400 μL of MEM Alpha was added, and cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Optical density (OD490) was measured in a 96-well plate reader (Bio-Rad, Model 680, USA) for both cell attachment and proliferation tests.

2.5. In vivo experiments

P2L8, P2L8-H10, and P2L8-mH10 films are the selected groups to study the effect of HA nanoparticles in low and high contents in vivo biocompatibility. Circular samples (n = 5 per group) were punched (diameter = 5 mm; thickness = 200–300 μm) from the films. All samples were disinfected using 70% ethanol solution and then dried in a vacuum oven for 24 h at 70 °C followed by an exposition of the biomaterials to the UV light in a biosafety cabinet for 8 h before implantation.

All animal procedures were approved by Universidad de Navarra Animal Ethics Committee and Navarra regional Government (Protocol number CEEA 004–18). Thirty BALB/c(Ola) mice aged 7 weeks were obtained from Harlan. Mice were anesthetised using inhalation anesthesia, Isofluorane (ISOFLUTEK® 1000 mg/g; Karizoo), maintained in a ratio of 1.5–2% throughout the complete procedure. The anesthetised mice were shaved dorsally, and a 1 cm incision was performed at the lower back of the mice to generate the subcutaneous space. Two samples from each group per animal were implanted in the right and left subcutaneous pocket space respectively. After the implantation, mice were housed in a barrier facility with a 24-h light/dark cycle. Mice were given ad libitum access to food and water and were sacrificed at 1 or 6 weeks after implantation (18 animals in total). At the respective final point, the implants were collected, including surrounding tissues, for histological and molecular analysis.

2.6. Histology and molecular analysis

The implants with surrounding tissues and capsules were washed in PBS and fixed in 4% PFA (PanReac, Barcelona, Spain) overnight for paraffin embedding following the previously described protocol [[40], [41], [42]]. Samples were dehydrated in graded ethanol and xylene, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm. For histological evaluation, selected sections of the biocomposites implants were hydrated in decreasing graded ethanol and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin to determine the level of fibrotic tissue and the presence of inflammatory cells. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed to specifically detect monocytes/macrophages using the primary antibodies of anti-F4/80 (ab6640; Abcam). Bright field digital images were acquired with an Aperio scan (Leica Biosystems) and fluorescence digital images with a Vectra Polaris Multispectral System (Perkin Elmer).

For molecular analysis, the implants were washed in PBS and the total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the manufacture instructions. Briefly, 1 μg of RNA was retrotranscripted using qScriptTM Supermix (Quantabio). The qPCR was performed in a 7300 Real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems) using actin beta (Actb, Mm02619580_g1) as a reference gene. Relative expression of the interleukine 6 (IL-6, Mm00446190_m1), Interleukine 1 beta (IL-1β, Mm02619580_g1) and interleukine 10 (IL-10, Mm01288386_m1) genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. All probes were purchased from Life Technologies.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For cell proliferation tests, a statistically significant difference between groups was accepted as p < 0.05 using Student's t-test. For molecular analysis, a statistically significant difference between groups was accepted as p < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA analysis followed up by the Tukey's Pos Hoc tests.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterisations of nanocomposites

3.1.1. Properties of modified nanoparticles

Fig. 2A shows FTIR spectra of HA and silane-modified HA (mHA) nanoparticles. Both HA and mHA showed the characteristic peak of stretching hydroxyl (at 3570 cm−1) and phosphate (symmetric stretching between 500 and 650 cm−1 and asymmetric stretching between 950 and 1100 cm−1), carbonate (asymmetric bending at 875 cm−1 and 1350-1500 cm−1) [34,43]. After silane modification, the spectrum of mHA showed additional peaks besides the characteristic peaks of HA. The new peaks at 2967 cm−1 and 1738 cm−1 are assigned with the stretching vibration of C–H and C O bonds of grafted MPTS molecules on the surface HA [25,31]. The added peak at 1363 cm−1 is symmetric bending of C–H bonds [44]. While the added peak at 1560 cm−1 is belong to Si–C bonds, the weak shoulder at 1217 cm−1 is attributed to the vibrations of Si–O–Si and C–O–C bonds [34,44,45]. The intensity of phosphate bands decreased in mHA spectrum due to the appearance of new peaks assigned with silane functional groups. These results suggested that the MPTS was successfully bonded with HA nanoparticles.

Fig. 2.

FTIR spectra (A) and XRD spectra (B) of the nanoparticles. SEM images of HA (C) and mHA (D) nanoparticles. Scale bar = 200 nm. The chemical functionalisation by MPTS can be found from FTIR spectra, while the XRD pattens and SEM images indicate a same crystallinity and morphologies for HA and mHA, respectively.

Fig. 2B displays the XRD patterns of HA and mHA nanoparticles. The crystalline phase of both nanoparticles is hydroxyapatite (Ca10(P O4)6 (OH)2) with a hexagonal crystal system, which is matched with standard ICDD card no. 96-900-2216 [46]. This means that the crystalline structure of the HA nanocrystals did not change after surface modification with MPTS. Silane coupling agents may not change the original crystalline of HA as they are normally used in low ratios for surface modification purposes. For example, functionalisation of HA by very low amounts of aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTS) [47] and vinyltrimethoxy silane (VTMS) [45] resulted in the same peaks as that of HA in XRD patterns.

Fig. 2C and D illustrates the SEM images of HA and mHA, respectively. The morphology of mHA is very similar to HA, mainly composed of spherical particles less than 150 nm in diameter. Thus, the morphology of the nanoparticles was not influenced by chemical modification. Few large spherical particles (200–500 nm) with some nanowhisker particles can also be found in both HA and mHA.

3.1.2. Thermal properties of nanocomposites

The effect of HA nanoparticles on the thermal properties and crystallinity of nanocomposites was investigated in DSC experiments, and the results are reported in Fig. 3 and Table 1. The neat PDO possesses a melting temperature (Tm) of 104.41 °C and crystallinity degree (Xc) of 72.06%. The high crystallinity in PDO is affected by the high level of polymeric chain arrangement in crystalline lamellae. Contrary, neat LCL showed only the Xc of 18.14%, indicating the copolymer is mainly amorphous. The low crystallinity in LCL is because of the random incorporation of caprolactone units in the LCL limiting the movement of l-lactide units [33,48,49]. P2L8 and all the nanocomposites showed two melting temperatures (Tm), indicating the immiscibility of PDO and LCL phases. Mixing PDO with LCL reduced the enthalpy of melting (ΔHm) and the crystallinity degree (Xc) for both PDO and LCL phases, which indicates that each polymer hinders the chains’ movement of the other polymer to fold and join the crystallisation growth front [50].

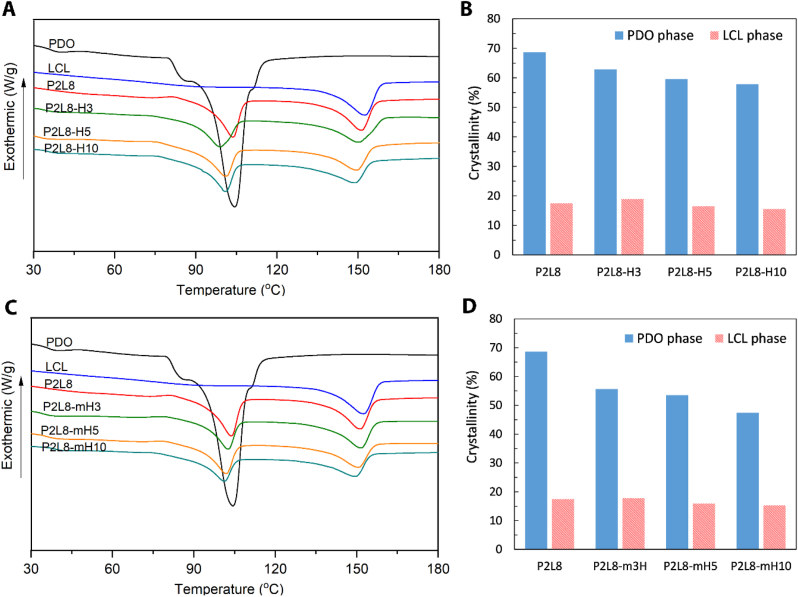

Fig. 3.

Thermal properties of PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites. DSC diagram (A) and degree of crystallinity (Xc) in PDO and LCL phases (B) of nanocomposites containing HA. DSC diagram (C) and degree of crystallinity (Xc) in PDO and LCL phases (D) of nanocomposites containing modified HA (mHA).

Table 1.

Melting temperature and crystallinity of PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites.

| Sample | PDO |

LCL |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J g−1) | WHH (°C) | Xc (%) | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J g−1) | WHH (°C) | Xc (%) | |

| PDO | 104.41 | 74.16 | 9.46 | 72.06 | – | – | – | |

| LCL | – | – | – | 152.56 | 16.36 | 12.59 | 18.14 | |

| P2L8 | 103.73 | 14.12 | 8.18 | 68.63 | 151.27 | 12.60 | 9.82 | 17.47 |

| P2L8-H3 | 98.86 | 12.94 | 10.61 | 62.88 | 150.45 | 13.68 | 13.72 | 18.97 |

| P2L8-H5 | 100.95 | 12.26 | 10.05 | 59.57 | 149.76 | 11.92 | 10.55 | 16.53 |

| P2L8-H10 | 100.74 | 11.91 | 9.12 | 57.87 | 149.15 | 11.23 | 11.82 | 15.57 |

| P2L8-mH3 | 102.79 | 11.45 | 8.87 | 55.64 | 151.03 | 12.8 | 10.77 | 17.75 |

| P2L8-mH5 | 101.76 | 11.02 | 8.33 | 53.55 | 150.73 | 11.47 | 10.36 | 15.9 |

| P2L8-mH10 | 101.16 | 9.76 | 8.93 | 47.42 | 149.84 | 10.99 | 11.27 | 15.24 |

From Fig. 3A and Table 1, adding HA into P2L8 reduced Tm of LCL phase constantly, which shows the good dispersion and interface bonding of HA in the LCL phase. However, the Tm value of PDO phase was slightly increased in P2L8-H5 and P2L8-H10, which could be related to the potential agglomeration of a part of HA in PDO phase by adding 5 wt% and 10 wt% of HA [37,51].

The Tm of LCL and PDO phases were continuously decreased by increasing mHA content in the nanocomposites. This indicates that the silane modification improves the dispersion of nanoparticles and uniformly heat transfer inside the polymer matrix. However, the mHA-based nanocomposites show slightly higher Tm values compared to the same percentage in HA-based nanocomposites. This implies that the mHA restricts the polymer chain movement more than HA nanoparticles because of the better interaction between silane methacrylate groups on the surface of mHA and hydroxyl/carboxylic groups of polymers.

The ΔHm and Xc of PDO phase decreased as the HA nanoparticles fraction increased. However, the ΔHm and Xc of LCL phase increased in P2L8-H3, and then, decreased in P2L8-H5 and P2L8-H10. It is well known that nanofillers show two different functions during polymer-chain crystallisation in nanocomposites. The nanoparticles may act as nucleation sites for the polymer-chain segments at low contents. However, the nanofillers also may prevent the segmental motion of the polymer chains from full incorporation in the growth of crystalline lamella, particularly at high contents [[52], [53], [54]]. Hence, an increase in ΔHm and Xc of LCL phase was only observed for 3 wt% of HA nanoparticles. From Fig. 3B and D, the incorporation of mHA nanoparticles resulted in lower ΔHm and Xc values than HA for the same nanoparticle content, showing the effect of silane modification on chain immobilization and imperfect crystal formation. However, the effect of the modification is stronger in PDO than LCL phase since more hydroxyl/carboxylic groups exist in PDO polymeric chains. For example, adding 10 wt% of mHA to P2L8 matrix reduced Xc of PDO phase to 47.42%, while HA for the same content of HA decreased the Xc to 57.8%; such a reduction in Xc value was not obtained in LCL phase by using mHA (Fig. 3D).

According to the width of the half-height crystallisation peak (WHH) data in Table 1, a decrease of WHH for both PDO and LCL phases can be observed in P2L8 blend. This reveals that each polymer increases the nucleation points in the matrix of the other polymer, leading to increase crystallisation rates [55,56]. The WHH of PDO and LCL increased for nanocomposites compared to P2L8, indicating that adding HA nanoparticles suppresses crystallisation rates by reducing the nucleation points in the polymer matrix [57,]. However, P2L8-H3 showed the highest WHH values, which means the lowest rate of crystallisation among the HA-based nanocomposites. Loading 3 wt% of HA to the polymer blend caused the highest Xc values and lowest rates of crystallisation among the samples, which shows the growth of crystals was perfect, but the number of crystals was low. Although the silane modification of HA nanoparticles showed a similar trend to non-modified HA on WHH values, the mHA-based nanocomposites possess lower WHH values compared to HA-based nanocomposites. This suggests that mHA caused higher rates of crystallisation through more nucleation points compared to HA nanoparticles. Given the fact that mHA also resulted in lower Xc values than HA nanoparticles, mHA can restrict the growth more crystals within a shorter time than HA nanoparticles; this leads to faster but more imperfect crystallisation. Similar observations were reported in other studies for the effect of nanofiller agglomerates on WHH and Xc [58].

3.1.3. Morphological properties of nanocomposites

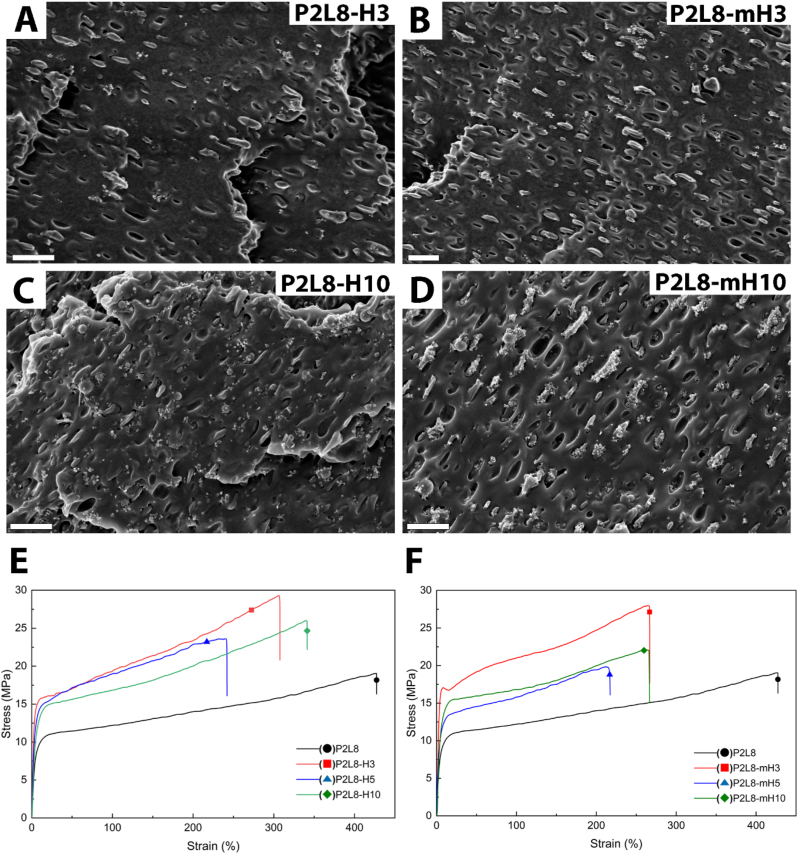

SEM images were taken from the fractured cross-sections of nanocomposites to observe the dispersion of the nanoparticles. The SEM image of P2L8 (Fig. S1) shows a droplet-matrix morphology, indicating the blend is immiscible. The small droplets of PDO (less than 2 μm) are uniformly dispersed in LCL matrix making a high interfacial surface between the PDO and LCL matrix. The droplet-matrix morphology can also be found in the SEM images of the nanocomposites as shown in Fig. 4. SEM images of P2L8-H3 (Fig. 4A) and P2L8-mH3 (Fig. 4B) demonstrate a good dispersion of the nanoparticles without any major agglomerations, caused by loading nanoparticles in a low content [45]. However, mHA nanoparticles can be found surrounding the PDO droplets rather than LCL matrix in P2L8-mH3. The difference in morphologies is more obvious when loaded with high content of the nanoparticles (10 wt%), as shown in Fig. 4C and D. While the HA nanoparticles are distributed uniformly in P2L8-H10 (Fig. 4C), high level of HA agglomerates can be found in the LCL matrix due to the weak dispersion of nanoparticles. Contrary, the mHA nanoparticles were mostly attracted to the PDO droplets in P2L8-mH10 (Fig. 4D), which was similarly observed in P2L8-mH3. Similar behaviours can be found for 5 wt% of HA and mHA (SEM images in Fig. S2).

Fig. 4.

Morphology of PDO/LCL/SF composites; SEM images of the fractured cross-sections of the P2L8-H3 (A), P2L8-mH3 (B), P2L8-H10 (C), P2L8-mH10 (D); scale bar = 2 μm. Tensile stress–strain curves of the nanocomposites containing HA (E) and modified HA (F).

The unmodified HA nanoparticles contain high numbers of –OH groups and exhibit hydrophilicity [24]. Hence, the affinity between the hydroxyl groups on the surface of HA imposes particle agglomeration [31]. Silane modification of HA nanoparticles using 3-(trimethoxysilyl) propyl methacrylate replaced a part of the hydroxyl groups of HA surface with organo-functional groups [28]. The long chains of MPTS groups, acting as spacers, hamper particle-particle attractions and prevent the agglomeration of mHA nanoparticles [59,60]. It is known that the dispersion of inorganic particles in polymer matrix can be usually improved by silane coupling agents generating a strong repulsion between the particles [24,34,61]. However, in the current work, silane-modified HA nanoparticles were attracted to PDO phase droplets. Since the size of PDO droplets is small (less than 2 μm), it could be understood that mHA nanoparticles agglomerated together inside the PDO phase. This different observation can be explained by interactions between functional groups. On one hand, although hydrophobic propyl chains were grafted on the surface of mHA, the hydrophilicity could be maintained to a certain extent due to the presence of carbonyl and ether groups [62]. On the other hand, PDO polymer chains possess more hydrophilic groups, i.e. carbonyls and ethers, than LCL chains, leading to the tendency of mHA nanoparticles to PDO because of the presence of polar functional groups on both sides.

The morphological observations indicate that the position of HA nanoparticles can be controlled in polymer phases by using silane modification. This could be beneficial for tissue engineering of mineralised tissues like bone and bone-tendon junctions.

3.1.4. Mechanical properties of nanocomposites

The effect of adding nanoparticles on the mechanical properties of nanocomposites was investigated by tensile tests. Typical stress–strain curves of PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites containing non-modified and modified nHA are displayed in Fig. 4E and F, respectively. The tensile properties of the nanocomposites are also listed in Table 2. P2L8 shows a very high elongation at break (383%) and toughness (54.9 MPa), which is caused by the notable strain-hardening behaviour of the material. As previously reported, the strain-hardening and toughening behaviour of P2L8 is due to the uniform dispersion of small PDO droplets in LCL matrix, acting as a load-bearing phase and decreasing stress concentration in high strains [33,49].

Table 2.

Tensile properties of PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites. Reported values are shown as the mean (n = 5) ± standard deviation for mechanical properties.

| Sample | Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Yield strength (MPa) | Ultimate strength (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) | Toughness (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2L8 | 199.22 ± 20.40 | 9.50 ± 0.93 | 18.03 ± 1.54 | 383.88 ± 68.36 | 54.91 ± 10.44 |

| P2L8-H3 | 453.40 ± 35.26 | 16.26 ± 1.49 | 31.54 ± 3.20 | 308.01 ± 48.37 | 69.95 ± 14.91 |

| P2L8-H5 | 326.20 ± 14.59 | 13.18 ± 0.99 | 23.32 ± 2.24 | 259.23 ± 49.25 | 49.58 ± 11.89 |

| P2L8-H10 | 256.29 ± 47.69 | 13.52 ± 1.20 | 25.73 ± 2.25 | 342.80 ± 32.44 | 64.07 ± 9.55 |

| P2L8-mH3 | 530.03 ± 17.42 | 18.14 ± 1.12 | 27.43 ± 4.05 | 248.06 ± 48.73 | 55.24 ± 14.30 |

| P2L8-mH5 | 347.74 ± 38.94 | 13.68 ± 1.12 | 21.88 ± 3.29 | 219.78 ± 14.38 | 38.98 ± 7.35 |

| P2L8-mH10 | 322.35 ± 36.07 | 14.03 ± 1.26 | 21.95 ± 2.73 | 265.19 ± 41.70 | 46.61 ± 10.38 |

From Fig. 4E and F, the incorporation of HA and mHA nanoparticles diminishes the elongation at break, while it typically increases the elastic modulus of the nanocomposites. Adding 3 wt% of HA increases elastic modulus (473 MPa), yield strength (16.2 MPa) and ultimate strength (31.5 MPa), while the elongation at break (308%) shows a reduction, due to the strong interactions between nanoparticles and P2L8 matrix. The high interaction between the particles and polymeric matrix limits free-volume and molecular mobility of the polymer chains, resulting inmaterial reinforcement [23,37,57,63]. This strong interaction also improves the stress-hardening behaviour, which leads to a greater toughness (∼70 MPa) in P2L8-H3 (Table 2). Conversely, adding 5 and 10 wt% of HA, P2L8-H5 and P2L8-H10, reduces the elastic modulus (up to ∼256 MPa), yield strength (up to ∼13 MPa) ultimate strength (up to ∼23 MPa). The accumulation of nanoparticles and poor interphase could weaken the modulus and strength of nanocomposites [[64], [65], [66]]. Moreover, adding HA nanoparticles up to 5 wt% diminishes the elongation at break (260%), since the nanoparticles locally concentrate the stress and form voids between the HA particles and polymer interface [66]. The nanocomposites with 10 wt% of HA show growth in elongation at break (342%), which could be associated with the presence of more nanoparticles in LCL phase (SEM image in Fig. 4C). This leads to a dominant loading bearing and strain-hardening behaviour in P2L8-H10, compared to the stress concentration effect of nanoparticles as the adverse effect on failure strain.

A similar effect on the tensile properties of nanocomposites can be found for modified HA (mHA) by increasing the nanoparticle concentration. However, the modification enhances the elastic modulus and yield strength of the samples. This is due to a strong interaction between the silane methacrylate groups on mHA surface and hydroxyl or carboxylic groups of PDO, resulting in the accumulation of the nanoparticles into PDO phase (SEM image in Fig. 4D) and reinforcing the hard phase in the P2L8 matrix. Accordingly, the strong integration between mHA and PDO phase leads to more stress concentrations and earlier failures in the nanocomposites. Hence, lower ultimate strength, elongation at break, and toughness were obtained in mHA compared to HA groups.

3.1.5. Surface roughness and hydrophilicity

The effect of HA nanoparticle and silane modification on surface properties was studied using SEM images, AFM topographic images and contact angle measurements. The surface morphology of the P2L8-H3, P2L8-mH3, P2L8-H10 and P2L8-mH10 are represented in Fig. 5Ai-Di, respectively. The addition of 3 wt% of the nanoparticles made the surface rougher than P2L8 (SEM image in Fig. S3), while HA and mHA nanoparticles resulted in similar surface morphologies at that concentration (Fig. 5Ai and 4Bi). The presence of nanoparticles is clear on the surface of both P2L8-H10 (Fig. 5Ci) and P2L8-mH10 (Fig. 5Di), indicating the effect of nanoparticle concentration on the roughness. Although the nanoparticle agglomerates on the surface, P2L8-mHA comprises slightly larger surface agglomerates than P2L8-H10, potentially due to the higher accumulation of mHA nanoparticles in PDO phase, as shown in the cross-section morphology of P2L8-mHA (SEM image in Fig. 4D).

Fig. 5.

Surface morphology, topography and hydrophilicity of PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites. SEM image of the surface of P2L8-H3 (Ai), P2L8-mH3 (Bi), P2L8-H10 (Ci), and P2L8-mH10 (Di). AFM images of P2L8-H3 (Aii), P2L8-mH3 (Bii), P2L8-H10 (Cii), and P2L8-mH10 (Dii). (E) Average roughness of the surfaces obtained from AFM. Water contact angles (F) and surface energy (G) of the nanocomposites. Scale bar = 10 μm.

To further investigate nanocomposites’ surface roughness, 3D topographic profiles (10 μm × 10 μm) and roughness analysis were obtained. The 3D topographic images of P2L8-H3, P2L8-mH3, P2L8-H10 and P2L8-mH10 are represented in Fig. 5Aii-Dii. As can be seen, increasing the nanoparticles did not change the typical surface topography of nanocomposites significantly, which is similar to the topographic image of P2L8 (Fig. S3). However, higher variations in amplitudes (y-axis in AFM maps) were obtained in modified nanoparticle groups and higher content groups; 10 wt% of mHA led to the highest variation in amplitude among the samples. Results from AFM analysis are represented in Fig. 5E and Table 3 for better comparison. The average roughness (Ra) values show an increasing trend with nanoparticle content (Fig. 5E) and silane modification of HA caused greater Ra values compared to non-modified HA groups, particularly for 10 wt% of nanoparticles. This roughness improvement could be due to more agglomerations of mHA than HA nanoparticles on the surface, as similarly observed in SEM images of P2L8-H10 and P2L8-mH10 (Fig. 5Ci and 5Di).

Table 3.

Surface roughness, contact angles, and calculated surface energies of the PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites. Reported values are shown as the mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation for contact angles.

| Sample | Average roughness (Ra, nm) | Maximum peak-to-valley height (Rt, nm) | Contact angle (deg) |

Surface energy (mN/m) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Diiodomethane (DIM) | γs | γd | γp | |||

| P2L8 | 24.72 ± 4.35 | 143 ± 25.58 | 81.7 ± 0.36 | 51.64 ± 0.96 | 33.43 | 27.83 | 5.60 |

| P2L8-H3 | 34.38 ± 6.51 | 177.2 ± 42.34 | 78.71 ± 0.61 | 43.10 ± 0.12 | 38.03 | 32.51 | 5.51 |

| P2L8-H5 | 46.14 ± 8.92 | 229.1 ± 37.67 | 75.45 ± 1.00 | 31.7 ± 0.63 | 43.51 | 38.13 | 5.37 |

| P2L8-H10 | 55.73 ± 15.16 | 289.5 ± 67.44 | 71.41 ± 0.59 | 27.9 ± 0.31 | 45.13 | 37.98 | 7.14 |

| P2L8-mH3 | 37.77 ± 8.63 | 212 ± 43.23 | 82.66 ± 0.15 | 44.87 ± 0.4 | 37.15 | 33.34 | 3.81 |

| P2L8-mH5 | 51.81 ± 18.42 | 277.8 ± 82.38 | 82.29 ± 0.07 | 42.04 ± 1.2 | 38.73 | 35.19 | 3.53 |

| P2L8-mH10 | 79.61 ± 15.23 | 408.3 ± 67.26 | 82.85 ± 0.53 | 40.31 ± 0.34 | 39.78 | 36.73 | 3.05 |

Contact angle is influenced by the chemical nature of the polymer, surface roughness, surface heterogeneity, surface energy, and type of the solvent used in the measurement and the crystallinity of the polymer [67]. Contact angle measurement, using water and diiodomethane (DIM), and the calculated surface energies are listed in Table 3. The average water contact angle of P2L8 was measured at 81.7°, which is closer to the contact angle of LCL rather than PDO reported in our previous study [33]. Contact angles of HA-based nanocomposites reduced with increasing HA nanoparticles in both water and DIM. This indicates that HA improves hydrophilicity in the nanocomposites, due to the increased surface roughness and hydroxyl groups of HA. Increasing roughness leads to more hydrophilic surfaces (for surfaces showing water contact angles lower than 90°) as the water droplet fills the grooves on the surface [68,69]. Similarly, improved hydrophilicity was observed in polymeric composites containing HA particles [31,70,71]. In contrast, mHA nanoparticles raised the water contact angles of the nanocomposites slightly (Fig. 5F). The hydrophobicity of the nanoparticles depends on hydroxyl groups; and the mHA nanoparticles possess fewer numbers of hydroxyl groups than HA nanoparticles because of silane functional groups. Hence, the use of 3-(trimethoxysilyl) propyl methacrylate, as a coupling agent to modify HA nanoparticles, could decrease hydrophilicity. This observation is in agreement with the hydrophobic behaviour of silane-modified nanoparticles and nanocomposites in previous studies [61,72,73]. However, increasing the content of mHA did not raise the contact angle in the nanocomposites remarkably, which could be affected by the opposite impact of roughness. In fact, the progressive roughness competes with hydrophobic mHA nanoparticles and moderates the effect of silane functional groups.

Surface energies (Fig. 5G) were calculated from water and DIM contact angles, showing a growing trend with loading both nanoparticles. However, HA-based nanocomposites displayed greater energy values compared to mHA-based samples because of the improved hydrophilicity of HA nanoparticles. In conclusion, using both HA and mHA nanoparticles result in hydrophilic nanocomposites (water contact angles lower than 90°), which could be useful in cell adhesion.

3.1.6. In vitro degradation

The simulated in vitro degradation tests can provide useful information about a biomaterial's absorption in the body over time. The degradation of alpha polyesters occurs by the erosion of the polymer beginning with the cleavage of hydrolytic bonds leading to the formation of acidic by-products [74]. The incorporation of hydroxyapatite particles in the polymer matrix changes the degradation profile of the polymer by varying the crystallinity, hydrophilicity, and water uptake characteristics. Hence, the hydrolytic degradation of the PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites was investigated in PBS media at 37 °C over 365 days.

Fig. 6A and B display the weight loss (%) of HA- and mHA-based nanocomposites, respectively. Hydrolytic degradation occurs faster by increasing the nanoparticle content compared with the neat P2L8 blend. Increased degradation in both groups can be explained by the effect of the nanoparticles on the crystallinity and structure of the polymer. As discussed earlier, loading both HA and mHA nanoparticles decreases the polymer crystallinities (Fig. 3B and D), facilitating the diffusion of hydrolysis medium (PBS) and the chain scission in the bulk of the samples [33]. In addition, the nanoparticles could increase the chance of PBS diffusion via a particle-polymer interface, the leakage of the degradation products throughout surface cracks and the solubility of the nanoparticles themselves [31]. A similar effect of hydroxyapatite on weight loss of PLA- and PCL-based nanocomposites was reported in previous studies [56,75,76].

Fig. 6.

Weight loss percentage of the nanocomposites containing HA (A) and mHA (B) during hydrolytic degradation. SEM images of the fractured cross-sections of P2L8-H10 (C) and P2L8-mHA10 (D) after 365 days of hydrolytic degradation; scale bar = 2 μm.

In comparison, the mHA nanoparticles resulted in greater weight loss than unmodified HA. For instance, P2L8-mH10 reduced by 10% more than P2L8-H10 after 365 days. Faster degradation rates of mHA-based nanocomposites could be attributed to the lower crystallinity values phases compared to HA groups. In addition, the position of mHA nanoparticles in PDO/LCL matrix affects in the degradation rate of samples. According to the morphology results, the mHA nanoparticles were mostly accumulated in PDO droplets, particularly in P2L8-mH10 (refer to Fig. 4D). As a result, the PDO phase degraded faster in mHA-based samples than HA-based groups. Furthermore, mHA nanoparticles built an interface between PDO and LCL phases, which may enhance the erosion of LCL regions near the PDO droplets. This could be confirmed by cross-section morphologies of P2L8-H10 (Fig. 6C) and P2L8-mH10 (Fig. 6D) since the pores attributed to PDO droplets are larger in P2L8-mH10 than P2L8-H10. In other words, mHA nanoparticles could increase the rate of degradation in both PDO and LCL phases.

This is a new observation since very limited studies have been carried out on the role of silane-modified nanoparticles on the degradation rates of the nanocomposites containing binary blends. Previously, Rakmae et al. [31] showed that silane modification of HA can reduce weight loss of the composites due to the hydrophobicity of the deposited silane coupling agent on the HA surface. In this work, the less hydrophilic feature was obtained by using mHA compared to HA nanoparticles; however, it seems that the effect of reduced crystallinities along with the position of mHA nanoparticles governed the degradation rates. Although the in vitro conditions were designed to stimulate the in vivo degradation mechanism in this study, in vivo degradation of alpha-polyesters is faster than in vitro degradation according to previous studies [[77], [78], [79]]. Hence, we expect that the in vivo degradation of PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites will be faster than in vitro hydrolytic degradation in this work. In the future, long-term studies through animal models can reveal more information about the role of nanoparticle type and content in biodegradation behaviour.

3.2. Biocompatibility of nanocomposites

3.2.1. In vitro study-cell proliferation and attachment

P2L8, P2L8-H5, P2L8-mH5, P2L8-H10, and P2L8-mH10 were selected as representative samples for in vitro cell studies. The quantitative MTS results of fibroblasts proliferated in the media and attached to the surfaces of the samples are displayed in Fig. 7A and B, respectively. The optical density of a negative control group (culture media without cells) was measured 0.228 ± 0.004, which was subtracted from presented results. All samples supported cell growth over 7 days of culture. The additions of nanoparticles did not change the results of proliferation and attachment. Furthermore, no significant difference was observed between HA and mHA groups. SEM imaging was used to display the adhered cells on the surface of P2L8 (Fig. 7C), P2L8-H5 (Fig. 7D), P2L8-mH5 (Fig. 7E), P2L8-H10 (Fig. 7F), and P2L8-mH10 (Fig. 7G) after 3 days. All the samples’ surfaces support cell growth with a similar cell density, which agree with the results of MTS assay.

Fig. 7.

Quantitative results of fibroblast proliferation (A) and attachment (B) by MTS test. SEM images of attached fibroblasts on the surface of P2L8 (C), P2L8-H5 (D), P2L8-mH5 (E), P2L8-H10 (F), and P2L8-mH10 (G) after 3 days culture. Quantitative results of osteoblast proliferation (H) and attachment (I) by MTS test. SEM images of attached osteoblasts on the surface of P2L8 (J), P2L8-H5 (K), P2L8-mH5 (L), P2L8-H10 (M), and P2L8-mH10 (N) after 3 days culture. The average results of 5 tests (n = 5) were reported for the quantitative results. The optical density of a negative control group (culture media without cells) was measured 0.228 ± 0.004, which was subtracted from the presented results. Scale bar = 20 μm.

The proliferation and attachment of osteoblasts over 7 days of culture are represented in Fig. 7H and I, respectively. All nanocomposites showed a higher density of proliferated osteoblasts in media compared to P2L8, particularly P2L8-H10 and P2L8-mH10 resulting in the highest values after 7 days. The effect of nanoparticles on the density of the adhered cells is highlighted in Fig. 7I. After only 3 days of culture, the attached osteoblasts increased by raising the nanoparticle content, while nanoparticle type (i.e. silane modification) had little effect. The promoted osteoblast attachment is confirmed by SEM images of the samples after 3 days of culture (Fig. 7J-N). P2L8-H10 and P2LmH10 demonstrate the most attached osteoblasts among the samples; however, no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05, Student's t-test) can be observed between P2L8-H10 and P2LmH10 or P2L8-H5 and P2LmH5. These results are in agreement with previous studies [[80], [81], [82]]. Improved biological performance of the mouse preosteoblasts was reported upon adding HA nanoparticles to polyhydroxybutyrate [80]. Similarly, higher contents of HA nanoparticles in PCL/HA nanocomposites showed the promoted proliferation and differentiation, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity of human fetal osteoblasts compared to neat PCL sample [81].

In this work, the results show that the nanocomposites support both fibroblasts and osteoblasts. However, the osteoblasts are promoted by increasing the hydroxyapatite content in the nanocomposites. This is beneficial for engineering tendon-bone junction tissue since the native tendon is only partially mineralised at the insertion region, but also involves different cell types in gradient, like tenocytes, fibrochondrocytes, and osteoblasts [2]. Hence, the tendon scaffold should support cell attachment and differentiation corresponding to biocomposition of the native ECM.

3.2.2. In vivo study-inflammatory response

In vivo studies on mice were conducted to understand the inflammatory response and foreign body reaction towards the implanted P2L8, P2L8-H10, and P2L8-mH10 samples. We found low amounts of fibrotic tissue surrounding the nanocomposite films in weeks one and six (Fig. S4). H&E-stained sections displayed normal histology in all groups after one week (Fig. 8Ai-8Aiii) and 6 weeks (Fig. 8Ci-8Ciii), with no obvious acute inflammatory reactions found. Moreover, no massive connective tissues were formed in the samples after 6 weeks of implantation, which indicate low chronic inflammatory reactions.

Fig. 8.

Inflammatory responses associated with P2L8, P2L8-H10 and P2L8-mH10 implants through histological and molecular analysis. H&E staining (Ai-Aiii) and F4/80 and immunofluorescent staining (Bi-Biii) sections of P2L8 (Ai, Bi), P2L8-H10 (Aii, Bii) and P2L8-mH10 (Aiii, Biii) after one week. H&E staining (Ci-Ciii) and F4/80 and immunofluorescent staining (Di-Diii) sections of P2L8 (Ci, Di), P2L8-H10 (Cii, Dii) and P2L8-mH10 (Ciii, Diii) after six weeks. Expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines including Il-6, Il-1β, Il-10 after one (Ei-Eiii) and six (Fi-Fiii) weeks of implantation.

As a key determinant of inflammation and a histopathological feature of chronic inflammation, macrophages were detected through F4/80 and immunofluorescence. low levels of macrophages were observed in all samples after one week of implantation (Fig. 8Bi-8Biii), whereas, after six weeks, macrophages increased in P2L8-mH10 (Fig. 8Diii) compared to P2L8 (Fig. 8Di) and P2L8-H10 (Fig. 8Dii). As with H&E data, the F4/80 macrophage data show low chronic inflammation of tissues surrounding the nanocomposite film after one and six weeks.

Il-6, Il-1β, and Il-10 indicate a pro-inflammatory environment mainly secreted from activated macrophages, stimulating the inflammatory response and foreign body reaction towards implanted materials. As shown in Fig. 8Ei-Eiii, after one week all the samples showed comparable average expression of Il-6 (Fig. 8Ei), Il-1b (Fig. 8Eii), and Il-10 (Fig. 8iii).

After 6 weeks, the expression of Il-6 (Fig. 8Fi), Il-1β (Fig. 8Fii), and Il-10 (Fig. 8Fiii) were increased in P2L8. In particular, the average expression of IL-6 for P2L8 was measured at approximately 100, at least 10-fold higher than P2L8-H10 and P2L8-mH10. Hence, the addition of nanoparticles reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines remarkably. By comparing P2L8-H10 and P2L8-mH10, it can be seen how silane modification of the nanoparticles reduced the expression of Il-6 and Il-1β, while it does not affect Il-10 after six weeks. The higher increased expression of Il-10 in P2L8 indicates a positive correlation between Il-6 and Il-10, which shows multiple cell types, such as monocytes, macrophages, and T-cells, counteracted the high inflammatory response and attempted to suppress inflammatory processes [83]. In this work, however, there is no statistically significant difference between groups based on one-way ANOVA analysis followed up by Tukey's Pos Hoc tests.

4. Conclusion

In this work, novel PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites based on unmodified and modified HA were developed and characterised for TL-bone interface tissue engineering. Nanocomposites containing 3–5 wt% of the nanoparticles showed a great balance between tensile properties, degradation rate, promoted cell activity for osteoblasts and fibroblasts, and good thermal properties for melt-processing. In addition, silane modification is beneficial to achieving higher tensile properties along with the faster release of HA from the bulk of the material, which results in a reduced pro-inflammatory response after implantation.

We recently showed that PDO/LCL blend based on the minority of PDO (10%–30%) resulted in tensile properties suiting native TLs [33]. However, a TL-bone junction is partially mineralised and involves different cell types such as osteoblasts (on the bone side) and tendon fibroblasts (on TL side). Moreover, the TL-bone interface possesses higher tensile strength than a TL tissue, while showing enough toughness and flexibility to transmit the generated forces to the bone with a minimal stress concentration. Hence the motivation here to use HA to mineralise aspects of the material.

Silane modification of the HA nanoparticle was confirmed by FTIR spectra, while the crystal phase and morphology of the nanoparticle did not show any significant change after modification. The melting enthalpy and crystallinity of the nanocomposites decreased upon the addition of both nanoparticle types; however, modified HA resulted in a higher polymeric chain movement and more imperfect crystallisation in both PDO and LCL phases. The cross-section morphologies demonstrated that HA was dispersed mainly in LCL phase with more agglomerates in high concentrations (10 wt%). Silane modification increased the population of nanoparticles in PDO droplets due to the high interaction between silane organofunctional groups and PDO chains. The tensile properties showed that adding both nanoparticles up to 3 wt% enhanced the elastic modulus and yield strength more than twice; however, further loading up to 10 wt% reduced the modulus and strength. The modified HA resulted in higher tensile properties than unmodified HA nanoparticles. The surface behaviour of the nanocomposites was evaluated using contact angle measurement and AFM imaging, which indicated that adding unmodified HA nanoparticles to P2L8 blend constantly increases the hydrophilicity, surface energy and roughness of the surfaces. However, increasing the content of mHA could decrease hydrophilicity, which could be affected by grafted silane organofunctional groups on the nanoparticle's surface. Furthermore, the hydrolytic degradation of the nanocomposites occurred faster after silane modification of the nanoparticles. In vitro cytotoxicity and cell attachment experiments indicated that no significant difference was observed between HA and mHA groups for both fibroblasts and osteoblasts. However, the osteoblasts were promoted by increasing the nanoparticle content in the nanocomposites. Although the in vivo experiments revealed that P2L8 and nanocomposites (P2L8-H10 and P2L8-mH10) are biocompatible materials without any serious inflammatory responses, the addition of HA nanoparticle into the blend can minimise the expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines after six weeks of implantation. The silane modification of the nanoparticles does not affect the biocompatibility of the samples adversely.

Overall, PDO/LCL/HA nanocomposites have great potential for TL-bone interface tissue engineering applications. However, further research is required to develop a continuous TL-to-bone scaffold system based on the nanocomposites to achieve biomimicking TL grafts suiting the TL interface regeneration. In addition, using human stem cells is essential to have better insight into the capability of cell differentiation and gene expression supported by the materials.

Credit authors statement

Behzad Shiroud Heidari: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Emma Muiños Lopez: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Ebrahim Vahabli: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Peilin Chen: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Rui Ruan: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Seyed Mohammad Davachi: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Review. Froilán Granero-Moltó: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Elena M. De-Juan-Pardo: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Minghao Zheng: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Barry Doyle: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:Behzad Shiroud Heidari reports financial support was provided by Western Australia Department of Jobs Tourism Science and Innovation. Barry Doyle reports financial support was provided by Australian Research Council. Minghao Zheng reports financial support was provided by Australian Research Council. Behzad Shiroud Heidari and Barry Doyle have patent #PCT/AU2021/050782 issued to The University of Western Australia.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the facilities, scientific and technical assistance of Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute at Curtin University and the Australian Microscopy & Microanalysis Research Facility at the Centre for Microscopy, Characterization & Analysis (CMCA), the University of Western Australia (UWA), a facility funded by the University, State and Commonwealth Governments. The authors also gratefully acknowledge funding from the Australian Research Council (IC170100061) through the Centre for Personalised Therapeutics Technologies, and the Science-Industry PhD Fellowship from the Western Australia Department of Jobs, Tourism, Science and Innovation (awarded to B.S.H.). B.S.H. and B.J.D. are inventors on a patent application (PCT/AU2021/050782) titled “Biocompatible polymer compositions” submitted by The University of Western Australia that covers the material composition described in this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100778.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Shiroud Heidari B., Ruan R., De-Juan-Pardo E.M., Zheng M., Doyle B. Biofabrication and signaling strategies for tendon/ligament interfacial tissue engineering. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021;7:383–399. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiroud Heidari B., Ruan R., Vahabli E., Chen P., De-Juan-Pardo E.M., Zheng M., Doyle B. Natural, synthetic and commercially-available biopolymers used to regenerate tendons and ligaments. Bioact. Mater. 2023;19:179–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sensini A., Massafra G., Gotti C., Zucchelli A., Cristofolini L. Tissue engineering for the insertions of tendons and ligaments: an overview of electrospun biomaterials and structures. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021;9:98. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.645544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han F., Li T., Li M., Zhang B., Wang Y., Zhu Y., Wu C. Nano-calcium silicate mineralized fish scale scaffolds for enhancing tendon-bone healing. Bioact. Mater. 2023;20:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolluru P.V., Lipner J., Liu W., Xia Y., Thomopoulos S., Genin G.M., Chasiotis I. Strong and tough mineralized PLGA nanofibers for tendon-to-bone scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:9442–9450. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Intra J., Glasgow J.M., Mai H.Q., Salem A.K. Pulsatile release of biomolecules from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chips with hydrolytically degradable seals. J. Contr. Release. 2008;127:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussein A.S., Abdullah N., Ahmadun F.R. In vitro degradation of poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles loaded with linamarin. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2013;7:33–41. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2012.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perron J.K., Naguib H.E., Daka J., Chawla A., Wilkins R. A study on the effect of degradation media on the physical and mechanical properties of porous PLGA 85/15 scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009;91:876–886. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen P., Wang A., Haynes W., Landao-Bassonga E., Lee C., Ruan R., Breidahl W., Shiroud Heidari B., Mitchell C.A., Zheng M. A bio-inductive collagen scaffold that supports human primary tendon-derived cell growth for rotator cuff repair. J. Orthop. Translat. 2021;31:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2021.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teuschl A., Heimel P., Nürnberger S., Van Griensven M., Redl H., Nau T. A novel silk fiber-based scaffold for regeneration of the anterior cruciate ligament: histological results from a study in sheep. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016;44:1547–1557. doi: 10.1177/0363546516631954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erisken C., Kalyon D.M., Wang H. Functionally graded electrospun polycaprolactone and β-tricalcium phosphate nanocomposites for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4065–4073. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi T., Liu Y., Hu Z., Cen M., Zeng C., Xu J., Zhao Z. Deformation performance and fracture toughness of carbon nanofiber-modified cement-based materials. ACI Mater. J. 2022;119:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora M., Chan E.K.S., Gupta S., Diwan A.D. Polymethylmethacrylate bone cements and additives: a review of the literature. World J. Orthoped. 2013;4:67. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v4.i2.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng H., Zhao X., Li L., Zhao X., Gao D. Water stability of bonding properties between nano-Fe2O3-modified magnesium-phosphate-cement mortar and steel fibre. Construct. Build. Mater. 2021;291 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y., Zhang F., Zhai W., Cheng S., Li J., Wang Y. Unraveling of advances in 3D-printed polymer-based bone scaffolds. Polymers. 2022;14:566. doi: 10.3390/polym14030566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cidonio G., Cooke M., Glinka M., Dawson J.I., Grover L., Oreffo R.O.C. Printing bone in a gel: using nanocomposite bioink to print functionalised bone scaffolds. Mater. Today Bio. 2019;4 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2019.100028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S., Gu R., Wang F., Zhao X., Yang F., Xu Y., Yan F., Zhu Y., Xia D., Liu Y. 3D-Printed PCL/Zn scaffolds for bone regeneration with a dose-dependent effect on osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis. Mater. Today Bio. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2021.100202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L., Li Q., Gui L., Deng Y., Wang L., Jiao J., Hu Y., Lan X., Hou J., Li Y., Lu D. Sequential gastrodin release PU/n-HA composite scaffolds reprogram macrophages for improved osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Bioact. Mater. 2023;19:24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minardi S., Taraballi F., Cabrera F.J., Van Eps J., Wang X., Gazze S.A., Fernandez-Mourev J.S., Tampieri A., Francis L., Weiner B.K. Biomimetic hydroxyapatite/collagen composite drives bone niche recapitulation in a rabbit orthotopic model. Mater. Today Bio. 2019;2 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2019.100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ge Y.-W., Chu M., Zhu Z.-Y., Ke Q.-F., Guo Y.-P., Zhang C.-Q., Jia W.-T. Nacre-inspired magnetically oriented micro-cellulose fibres/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan layered scaffold enhances pro-osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Mater. Today Bio. 2022;16 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shuai C., Yu L., Feng P., Gao C., Peng S. Interfacial reinforcement in bioceramic/biopolymer composite bone scaffold: the role of coupling agent. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2020;193 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogel M.R., Qiu H., Ameer G.A. The role of nanocomposites in bone regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. 2008;18:4233–4241. doi: 10.1039/b804692a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torabinejad B., Mohammadi-Rovshandeh J., Davachi S.M., Zamanian A. Synthesis and characterization of nanocomposite scaffolds based on triblock copolymer of l-lactide, ε-caprolactone and nano-hydroxyapatite for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2014;42:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kango S., Kalia S., Celli A., Njuguna J., Habibi Y., Kumar R. Surface modification of inorganic nanoparticles for development of organic-inorganic nanocomposites - a review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013;38:1232–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X., Song G., Lou T. Fabrication and characterization of nano-composite scaffold of PLLA/silane modified hydroxyapatite. Med. Eng. Phys. 2010;32:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sousa R.A., Reis R.L., Cunha A.M., Bevis M.J. Coupling of HDPE/hydroxyapatite composites by silane-based methodologies. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2003;14:475–487. doi: 10.1023/A:1023471011749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang M., Bonfield W. Chemically coupled hydroxyapatite-polyethylene composites: structure and properties. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tham W.L., Chow W.S., Ishak Z.A.M. The effect of 3-(trimethoxysilyl) propyl methacrylate on the mechanical, thermal, and morphological properties of poly(methyl methacrylate)/hydroxyapatite composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010;118:218–228. doi: 10.1002/app.32111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S.M., Liu J., Zhou W., Cheng L., Guo X.D. Interfacial fabrication and property of hydroxyapatite/polylactide resorbable bone fixation composites. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2005;5:516–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cap.2005.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi J., Xiao J., Zhang T., Zhang Y., Xiong C. Investigation of the nano-hydroxyapatite with different surface modifications on the properties of poly(lactide-co-glycolide acid)/poly(trimethylene carbonate)/nano-hydroxyapatite composites. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2021;299:623–635. doi: 10.1007/s00396-020-04783-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rakmae S., Ruksakulpiwat Y., Sutapun W., Suppakarn N. Effect of silane coupling agent treated bovine bone based carbonated hydroxyapatite on in vitro degradation behavior and bioactivity of PLA composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2012;32:1428–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma R., Li Q., Wang L., Zhang X., Fang L., Luo Z., Xue B., Ma L. Mechanical properties and in vivo study of modified-hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone biocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2017;73:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heidari B.S., Chen P., Ruan R., Davachi S.M., Al-Salami H., De Juan Pardo E., Zheng M., Doyle B. A novel biocompatible polymeric blend for applications requiring high toughness and tailored degradation rate. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2021;9:2532–2546. doi: 10.1039/d0tb02971h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lung C.Y.K., Sarfraz Z., Habib A., Khan A.S., Matinlinna J.P. Effect of silanization of hydroxyapatite fillers on physical and mechanical properties of a bis-GMA based resin composite. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016;54:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahlinder A., Fuoco T., Finne-Wistrand A. Medical grade polylactide, copolyesters and polydioxanone: rheological properties and melt stability. Polym. Test. 2018;72:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2018.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brostow W., Hagg Lobland H.E., Khoja S. Brittleness and toughness of polymers and other materials. Mater. Lett. 2015;159:478–480. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.07.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toghi Aval S., Davachi S.M., Sahraeian R., Dadmohammadi Y., Shiroud Heidari B., Seyfi J., Hejazi I., Mosleh I., Abbaspourrad A. Nanoperlite effect on thermal, rheological, surface and cellular properties of poly lactic acid/nanoperlite nanocomposites for multipurpose applications. Polym. Test. 2020;91 doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pae A., Kim S.-S., Kim H.-S., Woo Y.-H. Osteoblast-like cell attachment and proliferation on turned, blasted, and anodized titanium surfaces. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants. 2011;26:475–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fairbanks B.D., Thissen H., Maurdev G., Pasic P., White J.F., Meagher L. Inhibition of protein and cell attachment on materials generated from N -(2-hydroxypropyl) acrylamide. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:3259–3266. doi: 10.1021/bm500654q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.González-Gil A.B., Lamo-Espinosa J.M., Muiños-López E., Ripalda-Cemboráin P., Abizanda G., Valdés-Fernández J., López-Martínez T., Flandes-Iparraguirre M., Andreu I., Elizalde M.R., Stuckensen K., Groll J., De-Juan-Pardo E.M., Prósper F., Granero-Moltó F. Periosteum-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells in engineered implants promote fracture healing in a critical-size defect rat model. J Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019;13:742–752. doi: 10.1002/term.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Granero-Moltó F., Weis J.A., Miga M.I., Landis B., Myers T.J., O'Rear L., Longobardi L., Jansen E.D., Mortlock D.P., Spagnoli A. Regenerative effects of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells in fracture healing. Stem Cell. 2009;27:1887–1898. doi: 10.1002/stem.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muinos-López E., Ripalda-Cemboráin P., López-Martínez T., González-Gil A.B., Lamo-Espinosa J.M., Valentí A., Mortlock D.P., Valentí J.R., Prósper F., Granero-Moltó F. Hypoxia and reactive oxygen species homeostasis in mesenchymal progenitor cells define a molecular mechanism for fracture nonunion. Stem Cell. 2016;34:2342–2353. doi: 10.1002/stem.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miculescu F., Mocanu A.C., Dascălu C.A., Maidaniuc A., Batalu D., Berbecaru A., Voicu S.I., Miculescu M., Thakur V.K., Ciocan L.T. Facile synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite particles for high value nanocomposites and biomaterials. Vacuum. 2017;146:614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.vacuum.2017.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahmed G.S., Gilberts M., Mainprize S., Rogerson M. FTIR analysis of silane grafted high density polyethylene, Plastics. Rubber and Composites. 2009;38:13–20. doi: 10.1179/174328909X387711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tham D.Q., Huynh M.D., Linh N.T.D., Van D.T.C., Van Cong D., Dung N.T.K., Trang N.T.T., Van Lam P., Hoang T., Lam T.D. Pmma bone cements modified with silane-treated and pmma-grafted hydroxyapatite nanocrystals: preparation and characterization. Polymers. 2021;13:3860. doi: 10.3390/polym13223860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson R.M., Elliott J.C., Dowker S.E.P. Rietveld refinement of the crystallographic structure of human dental enamel apatites. Am. Mineral. 1999;84:1406–1414. doi: 10.2138/am-1999-0919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rehman S., Khan K., Mujahid M., Nosheen S. Synthesis of nano-hydroxyapatite and its rapid mediated surface functionalization by silane coupling agent. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2016;58:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grijpma D.W., Zondervan G.J., Pennings A.J. High molecular weight copolymers of l-lactide and ε-caprolactone as biodegradable elastomeric implant materials. Polym. Bull. 1991;25:327–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00316902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heidari B.S., Lopez E.M., Harrington E., Ruan R., Chen P., Davachi S.M., Allardyce B., Rajkhowa R., Dilley R., Granero-Moltó F. Novel hybrid biocomposites for tendon grafts: the addition of silk to polydioxanone and poly (lactide-co-caprolactone) enhances material properties, in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility. Bioact. Mater. 2023;25:291–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goonoo N., Jeetah R., Bhaw-Luximon A., Jhurry D. Polydioxanone-based bio-materials for tissue engineering and drug/gene delivery applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015;97:371–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimpi N., Shirole S., Mishra S. Polypropylene/nTiO2 nanocomposites using melt mixing and its investigation on mechanical and thermal properties. Polym. Compos. 2017;38:1273–1279. doi: 10.1002/pc.23692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li K., Yeung C.Y., Yeung K.W.K., Tjong S.C. Sintered hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites: mechanical behavior and biocompatibility. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2012;14 doi: 10.1002/adem.201080145. B155–B165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hajibabazadeh S., Razavi Aghjeh M.K., Mehrabi Mazidi M. Stiffness-toughness balance in PP/EPDM/SiO2 ternary blend-nanocomposites: the role of microstructural evolution. J. Compos. Mater. 2021;55:265–275. doi: 10.1177/0021998320948125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Priya L., Jog J.P. Poly(vinylidene fluoride)/clay nanocomposites prepared by melt intercalation: crystallization and dynamic mechanical behavior studies. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2002;40:1682–1689. doi: 10.1002/polb.10223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heidari B.S., Davachi S.M., Sahraeian R., Esfandeh M., Rashedi H., Seyfi J. Investigating thermal and surface properties of low-density polyethylene/nanoperlite nanocomposites for packaging applications. Polym. Compos. 2019;40:2929–2937. doi: 10.1002/pc.25126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davachi S.M., Kaffashi B., Torabinejad B., Zamanian A. In-vitro investigation and hydrolytic degradation of antibacterial nanocomposites based on PLLA/triclosan/nano-hydroxyapatite. Polymer (Guildf) 2016;83:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2015.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balali S., Davachi S.M., Sahraeian R., Shiroud Heidari B., Seyfi J., Hejazi I. Preparation and characterization of composite blends based on polylactic acid/polycaprolactone and silk. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:4358–4369. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b01254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]