Abstract

Youth suicide is increasing in the United States, with deaths among younger people of color driving this upward trend. For more than four decades, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) communities have suffered disproportionate rates of youth suicide and years of productive life lost compared to other U.S. Races. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) recently funded three regional Collaborative Hubs to carry out suicide prevention research, practice, and policy development with AIAN communities in Alaska and rural and urban areas of the Southwestern United States. The Hub partnerships are supporting a diverse array of tribally-driven studies, approaches, and policies with immediate value for increasing empirically driven public health strategies to address youth suicide. We discuss unique features of the cross-Hub work, including: (a) long-standing Community-Based Participatory Research processes that led to the Hubs’ innovative designs and novel approaches to suicide prevention and evaluation, (b) comprehensive ecological theoretical approaches that contextualize individual risk and protective factors in multilevel social contexts; (c) unique task-shifting and systems of care approaches to increase reach and impact on youth suicide in low-resource settings; and (d) prioritization of strengths-based approaches. The work of the Collaborative Hubs for AIAN youth suicide prevention is generating specific and substantive implications for practice, policy, and research presented in this article at a time when youth suicide prevention is a dire national priority. Approaches also have relevance for historically marginalized communities worldwide.

Keywords: prevention, suicide, American Indian, Alaska Native, CBPR, resilience, cultural strengths, ecological approach, task-shifting

➤BACKGROUND

The United States faces its highest rates of suicide since World War II, with youth of color comprising the fastest growing demographic group at risk (Weir, 2019). These trends are alarming, with extreme importance to American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) populations who have suffered inequitable youth suicide rates predating the national surge. For over 40 years, AIAN youth ages 10 to 24 have endured suicide rates at least 2.4× higher than all U.S. youth (Suicide Prevention Resource Center, n.d.). Some tribes and geographic regions experience even greater disparities, including Alaska and the Southwest, where rates for 15- to 24-year-old AIANs have exceeded 10× to 13× the U.S. rate for the same age group (Ehlman et al., 2022; Mullany et al., 2009; Wexler et al., 2012).

AIAN mental health inequities are rooted in the enduring legacy of colonization, historical trauma, rapid losses of traditional ways of living and their respective culture-based protective factors, interpersonal and institutional discrimination, and denial of tribal nations’ rights to self-determination and sovereignty (Gone & Trimble, 2012). These inequities are perpetuated through a chronically under-resourced health care system caused by the U.S. government’s negligence in honoring treaties that included provisions for federal health care (Warne & Frizzell, 2014). The COVID-19 pandemic has placed additional pressures on already overburdened community health services, intensifying risks for AIAN youth suicide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2021; Yard et al., 2021). AIAN communities and Indigenous and allied research teams may be ahead of others in understanding how this legacy of oppression, discrimination, and systemic racism underpins current AIAN youth suicide disparities. Similar intergenerational histories of oppression and resulting health inequities are shared by other U.S. youth of color and Indigenous youth worldwide. These populations are also experiencing increasing suicide disparity gaps and share needs for more culturally driven, health-equity focused prevention research (Power et al., 2020). They, too, could benefit from lessons learned within Indigenous prevention science initiatives. There may be no more devastating event for a family and community than a loss of a young person to suicide. Increasing disparity gaps in communities that are historically and currently marginalized must not be tolerated. It is urgent to mount comprehensive community-based prevention research centered in community-based participatory approaches that reflect recognition of youth’s suicide risk and protective factors relative to their historical, social, and cultural contexts.

➤PURPOSE

Toward this end, the purpose of this article is to report on innovative interventions, policies, and practices undertaken by three Collaborative Hubs to Reduce the Burden of Suicide among American Indian and Alaska Native Youth that formed in 2017. The three Hubs’ research is founded on decades of community-engaged research with geographically and culturally diverse AIAN populations. The research designs and foci in terms of how they have been conceived, implemented and evaluated hold promise for informing new public health approaches to reverse increases in youth suicide among tribal, and other U.S. and global populations. In addition, the collaboration between the Hubs as reflected by this article has the potential to accelerate generalizable approaches and lessons learned. Given the urgency of youth suicide, particularly in light of mounting evidence that racial and ethnic disparities are growing, this article offers state-of-the-science directions created through deep community engagement. Research done through community-based participatory processes can help drive authentic and rigorous approaches to reverse the alarming trends in youth suicide, particularly among AIAN and other racial and ethnic minority populations.

➤METHOD

Recognizing the need for empirical work to guide preventive interventions and policies for AIAN communities, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) issued the first large-scale AIAN-specific federal research program to address youth suicide, called the Collaborative Hubs to Reduce the Burden of Suicide among American Indian and Alaska Native Youth (hereafter, “Collaborative Hubs”). The stated aim of the request for proposals was to “increase the reach and research base for effective, culturally relevant, preventive interventions that will increase resilience and reduce suicide in tribal or urban Indian communities.” In 2017, this mechanism funded three Hubs that operate through tribal-academic partnerships in rural Alaska, the Southwestern United States, and urban AIAN populations in Albuquerque, NM. The Hubs’ activities are diverse in geographic settings (rural/reservation to urban), intervention approaches (clinic-based, home-based, community/society-wide), and research methods (randomized controlled trials of clinical and behavioral interventions; cross-sectional observational studies of social determinants; and policy, cost-effectiveness, and implementation science analyses). There is also special focus on community-level protective processes—including tribal governance, culturally responsive services, centering work on cultural strengths and community-based support systems that promote multilevel prevention pathways. See Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Study Details and Descriptions of Collaborative Hubs for American Indian/Alaska Native Youth Suicide Prevention

| Hub name | Population settings | Participant population characteristics | Research or intervention context | Research focus or intervention type | Study design features | Primary outcomes | Practice elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Alaska Native Collaborative Hub for Research on Resilience (ANCHRR) | Rural, geographically remote, small population (pop. 150–~1000) Alaska Native communities | Young people ages 12–25 and adults residing in the participating communities at least 5 years | Community | Development of multilevel community model to understand protective factors and mechanisms that reduce suicide risk and promote wellbeing | Cross-sectional mixed methods design tests and describes social determinants in a multilevel model of protection from suicide | Individual level: Reasons for Life, Reflective Processes Community level: Suicide attempt; suicide death | Identify pathways of community and individual-level suicide risk and protection to expand prevention tools and to guide new models of multilevel intervention |

| Southwest Hub for American Indian Youth Suicide Prevention Research | Southwestern Rural reservation communities | Youth ages 10–24 with recent suicidal ideation, attempt or binge substance abuse episode with recent suicidal ideation | Home or private setting | Brief (2 hr) one-on-one Interventions taught by para-professionals New Hope Risk Reduction Elders Resilience Curriculum to promote cultural protective factors | Randomized factorial design of: (a) NH alone with CMI; (b) ER with CMI; (c) NH+ER+CMI; or (d) CMI alone Embedded cost-effectiveness study of brief interventions Implementation research to study key features for sustainability and scaling | Reduced suicidal Ideation; Increased resilience | Scaling WMIAT “Celebrating Life” Community-Based Suicide Surveillance and Case Mlanagement System |

| The Urban AIAN Hub | Mlajor Urban Indian Health Organizations | Urban youth and young adults, ages 18–34 at risk of suicide | Clinic based | SBIRT Caring Texts 36 text-based messages over 12 months to promote protective factors | Randomized Control Trial of SBIRT vs. SBIRT + Caring Texts | Early identification of suicide risk; referral to intervention Increased social connectedness and resilience | Quality assurance measures to maximize screening coverage and implementation fidelity Referral procedures to increase transition to care Culturally tailored texts of support; determine optimal frequency of delivery and barriers to receipt |

Note. SMART = sequential multiple assignment randomized trial; NH = New Hope; CM = Case Management; ER = Elders Resilience; WMAT = White Mountain Apache Tribe; AIAN = American Indian and Alaska Native; SBIRT = Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment.

The Hubs’ ability to implement and evaluate comprehensive intervention and policy approaches to youth suicide are due to long-standing tribal-academic relationships built on community-based participatory research (CBPR) engagement over decades (Walter et al., n.d.). CBPR is an iterative process of action, reflection, and experiential learning; and, its conceptual emphasis is on changing the power structure of the researcher and the “researched” so that members of research communities are equal participants, not passive subjects, in a mutually beneficial process (Faridi et al., 2007). CBPR is an essential framework in AIAN settings where research has historically marginalized, excluded, or exploited citizens (Walter et al., n.d.). CBPR frameworks are especially critical to the Hubs’ suicide prevention work as historical, contemporary, and social injustices and related intergenerational experiences underlie suicide risks and protection in tribal communities. The authors of this article represent Indigenous and allied researchers, including some who originate from the participating communities, who are funded by and are administering the three Collaborative Hubs. Their teams have been dedicated to CBPR and youth suicide prevention with AIAN communities for over 30 years.

➤RESULTS

The following sections review histories of CBPR that led to each of the three Hubs’ current work; the core research, policy, and practices distinct to each Hub; and the implications of this work for youth suicide prevention in the United States and globally.

The Alaska Native Collaborative Hub for Research on Resilience (ANCHRR)

The ANCHRR (hereafter, Alaska Hub) is a statewide partnership anchored by the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Center for Alaska Native Health Research. Its research is engaging 64 rural Alaska Native communities across the Yukon Kuskokwim, Bering Straits, and Northwest regions of western Alaska with a statewide network of Alaska Native suicide prevention stakeholders. Communities in western Alaska are hundreds of miles off the contiguous road system; their ethnicity is majority Alaska Native and includes Inupiaq, Yup’ik, Cup’ik, and Athabascan peoples. In contrast to the reservation system in the lower 48 states, these communities are each a federally recognized tribal entity. Suicide mortality rates for AN 15- to 24-year-olds are 7.4 times greater than the U.S. 15- to 24-year-old general population, and suicide is the leading cause of death for this age group (Alaska Native Epidemiology Center, 2021). The Alaska Hub’s work builds from two long-term CBPR-based initiatives carried out by Alaska Native communities and their research partners. The first partnership engages with Yup’ik/Cup’ik communities in the Yukon-Kuskokwim region to generate a protective factors model that resulted in the development of Qungasvik (Tools for Life), a Yup’ik theory-driven, strengths-based preventive intervention to reduce suicide risk and alcohol misuse in rural Alaska Native youth (Rasmus et al., 2019). The second project is a partnership with communities in the Northwest and Bering Strait regions that led to the development of Promoting Community Conversations About Research to End Suicide (PC CARES), a community mobilization approach to suicide prevention that brings community members together to translate research into self-determined practices (Wexler et al., 2019). The Alaska Hub expanded this work into a statewide initiative to change the narrative in Alaska Native suicide prevention from deficit and risk reduction to protection and the promotion of cultural and community strengths.

The goal of the current Alaska Hub’s core research, called the Alaska Native Community Resilience Study, is to describe community-level protective factors and their mechanisms for youth suicide prevention. Working with 64 rural AN communities, the first aim is to identify protective factors that inversely predict community-level suicide outcomes. The second aim seeks to understand mechanisms through which these community-level factors influence individual-level protection from suicide and alcohol risk among young people by modeling the pathways of their effects. To inform this understanding, the study uses mixed methods that combine youth and adult survey data with adult and youth interview data and youth digital stories.

Study Governance.

The Alaska Hub has paid careful attention to building a participatory governance structure that includes multiple layers of tribal and allied stakeholders’ advisory oversight. This includes: (a) an Executive Advisory Committee of statewide Alaska Native leaders in tribal health and governance; (b) a Research Steering Committee of Alaska Native community members from regions participating in the Alaska Native Community Resilience Study; and (c) a Collaborative Network of key stakeholders and providers across Alaska who are continuously informed and consulted. The Executive Advisory Committee provides annual strategic guidance focused on policy implications. The Research Steering Committee meets monthly to guide all aspects of the Alaska Hub’s research. The scope of the Research Steering Committee involves balancing community and scientific priorities, adherence to AN cultural protocols in conducting research, and attention to the realities of work in remote rural Alaska settings. The entire Collaborative Hub gathers annually, bringing these committees and the university researchers together with a “Collaborative Network” of 50 to 75 Alaska Native suicide prevention stakeholders. These gatherings have showcased Alaska Native youth’s ideas and input, community strengths, and the Hub’s ongoing research findings. The Executive Advisory Committee and Research Steering Committee shape the research process and foci, while the Collaborative Network provides input on research priorities whiles also disseminating research findings and laterally sharing local prevention approaches. As one example of the synergies within this governance structure, the Executive Advisory Committee suggested the research integrate youth perspectives. The Research Steering Committee concurred and provided guidance on procedures for a proposed study. The university researchers’ team then applied for supplemental funding to add a youth digital-storytelling project to the core study situated at this confluence of community and scientific priorities. This promising practice for engaging youth in health research provides a vehicle to describe strengths-based protective mechanisms for suicide among young people and disseminate them to Indigenous communities (Wexler et al., 2012).

The Alaska Hub’s research is among the first designed to describe the mechanisms by which cultural and other social determinants support Indigenous youth resilience and wellness (Morris & Crooks, 2015) and protect against suicide. This holds promise to inform upstream suicide prevention efforts for young people by promoting hopeful pathways to a promising future. The Alaska Hub’s governance structure also presents a community-engaged participatory research model that integrates and synergizes diverse stakeholder perspectives. Input from a combination of executive leaders in tribal health, adult and youth community members, and services providers promotes fresh thinking on existing and potential grassroots solutions while providing community direction and ownership for sustainability.

The Southwest Hub for American Indian Youth Suicide Prevention Research

The Southwest Hub for American Indian Youth Suicide Prevention Research is led by long-standing tribal-academic partners, the White Mountain Apache Tribe (WMAT) and the Johns Hopkins University Center for American Indian Health (JHU). The WMAT is located on 1.67 million acres of rural lands that comprise the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in east-central Arizona. Today, there are over 17,000 enrolled tribal members who are working to overcome the ubiquitous effects of past colonial traumas and who respect community-based research as a tool for promoting future health equity and well-being. In 1993, the WMAT reached out to JHU, with whom they have engaged in public health research collaborations dating back to the late 1970s, with concerns about a spike in youth suicide. A delegation of tribal leaders traveled to JHU to consult with pediatric suicide experts and develop strategies to reduce youth suicide. Throughout the next 7 years, WMAT-JHU partners determined suicide rates were 13× higher than rates in the United States for all races ages 15- to 24-year-olds, and identified tribal-specific patterns related to gender, methods, precipitants, and prior health services history among those who died (Mullany et al., 2009). Findings informed initial community-based programs to promote family strengthening and positive cultural identity as preventive interventions.

In 2001, another spike in youth suicide led the Tribal Council to establish by law the first-ever tribally mandated, community-based suicide surveillance and case management system, named “The Celebrating Life System” (Cwik, Tingey, Maschino, et al., 2016). To this day, the Celebrating Life System collects data on suicide ideation, attempt, deaths, intentional self-harm, and binge substance use through mandated reporting by all service agencies and community members to a central registry. In 2007, WMAT appointed JHU partners to employ and support Apache case managers to follow up in person to verify reported incidents and connect individuals to available care. The program is now managed by a local Apache supervisor who completed graduate-level clinical training. Ongoing research has shown that the Celebrating Life System helps reduce suicide deaths and attempts on a population level (Cwik, Tingey, Maschino, et al., 2016). The WMAT Celebrating Life System is now the centerpiece of the Southwest Hub’s research and practice activities.

The Southwest Hub’s research is focused on evaluating two brief (2–4 hr) interventions linked to the Celebrating Life system addressing tribal-specific risk and protective factors for youth suicide illuminated by over 15 years of qualitative and quantitative studies (O’Keefe et al., 2019). The first is a crisis intervention for youth with active suicidal behavior, called “New Hope,” that provides safety planning and connection to mental health services for youth and a primary caregiver (Cwik, Tingey, Lee, et al., 2016). The second called the “Elders’ Resilience Curriculum,” is a culturally-grounded intervention with traditional stories, values, and language taught by local Elders to strengthen youth cultural identity and community connectedness found to protect against suicide (Cwik et al., 2019). The Hub is using a factorial design to study the impact of the two interventions alone or in combination (O’Keefe et al., 2019). Study participants are Apache youth ages 10 to 24 years reported to the Celebrating Life System for suicide attempt, ideation, or binge substance use with recent ideation (recruitment goal: N = 304; Cwik et al., 2019). Repeated assessments through 6 months, adapted through community input, are measuring intervention effects on suicide ideation and resilience and whether youth respond better to New Hope (risk reduction), Elders Resilience Curriculum (cultural protective factor promotion), or a combination of the two, compared with Case Management alone (Haroz et al., 2022). The study is managed by a team of Indigenous and allied researchers, including leaders from the Apache community, who provide guidance, training, and support to four Apache mental health specialists who deliver the intervention components or administer study assessments. A local Elders Council with up to 25 participants serves as the primary community advisory board.

In the meantime, the Southwest Hub has a practice component that supports other tribes to adapt and implement the surveillance and case management system as a “standard-of-care” strategy for suicide prevention, including the Navajo Nation, San Carlos Apache, Hualapai, and Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. The Fort Peck Tribes in Montana also took the preliminary step of conducting formative work about how to implement the Celebrating Life System in their communities. The practice partners meet twice a year with the research partners (WMAT-JHU) to continuously review progress and share best practices. Paired with these practice activities, WMAT-JHU partners are studying key factors for successful implementation and sustainability in these varied settings (Haroz et al., 2021).

The Southwest Hub’s study has the potential to inform the evidence base for brief community-based, culturally proficient interventions to maximize impact and resource efficiency. Its practice component is elevating community-based surveillance and case management as a standard of care within rural tribal communities that have large gaps in mental health services.

The Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Hub

The Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Hub (Urban) focuses on urban AIAN youth and young adults and is a joint effort of the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and Washington State University’s Institute for Research and Education to Advance Community Health in partnership with the largest Urban Indian Health Organization (UIHO)—the First Nations Community Healthsource in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Located in southeast Albuquerque, First Nations Community Healthsource offers services at no cost to eligible AIANs of all tribal affiliations who live or come to the Albuquerque region. Albuquerque’s total population is 570,000, of whom 27,000 (5%) are AIANs. Although tribally diverse, the largest proportion are Navajo (48%). In general, the AIAN population in Albuquerque has higher poverty and homelessness rates, and those ages 18 to 34 years have a suicide rate of 42–80/100,000, higher than their counterparts in all other racial/ethnic groups, with the largest disparity gap around age 25 (New Mexico Department of Health, 2020).

Often called our nation’s largest tribe, urban AIANs are members of a diverse, rapidly growing population that comprises over 75% of the 9.7 million AIANs in the United States (NCAI Policy Research Center, 2021). Urban AIANs share similar health challenges to the general Native population, but their problems are often exacerbated by disconnection from family and traditional cultural environments. Compared with the general population, urban AIANs more often live in poverty (20% vs. 13%) and less often report adequate social support (9% vs. 15%) (National Urban Indian Family Coalition, 2008).

Recognizing the health disparities faced by urban AIANs, the Indian Health Service (IHS) funds 41 Urban Indian Health Organizations, though this support represents only 1% of the IHS budget (Indian Health Service, 2018). Despite chronic underfunding, Urban Indian Health Organizations provide culturally sensitive medical and dental care, social services, education, and economic development programs for urban AIANs who lack access to resources through IHS or tribally operated facilities. Such limited resources severely constrain Urban Indian Health Organizations’ ability to address suicide and related risks, which has prompted the Urban Hub to research feasible, cost-effective prevention interventions.

The Urban Hub’s core study evaluates a Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) model’s impact on youth suicide prevention. SBIRT is an evidence-based practice to address alcohol abuse and dependence, predominantly used in primary care settings (Young et al., 2014). By co-locating a behavioral health clinician in the primary care team, SBIRT offers an immediate response to expressed risk and timely intervention by a trained professional (Young et al., 2014). The First Nations Community Healthsource had a pre-existing SBIRT program for substance use. Their leadership welcomed adaptations to SBIRT to screen and manage risk of suicide. The UIHO-academic team collaborated to enhance its existing protocols, co-developed a dashboard for monitoring clinic performance, augmented clinic staff, agreed upon the age range for the intervention, and co-developed crisis intervention policies and procedures.

The Urban Hub is also studying whether the marriage of SBIRT with a text message-based version of Caring Contacts, one of two interventions shown to prevent suicide in Randomized Control Trials, increases the impact on youth suicide prevention (Skopp et al., 2022). In the original Caring Contacts study, patients discharged from inpatient care for depression or suicidality received brief, non-demanding letters that increased patient social connectedness and engagement and reduced suicidal ideation, attempts, and hospitalizations among at-risk individuals (Fleischmann et al., 2008). A recent large-scale randomized controlled trial among active-duty military personnel at high risk of suicide demonstrated that the original approach translates successfully to delivery by text messaging (Comtois et al., 2019). Health interventions using mobile phones are increasingly deployed to treat behavioral health problems. This approach is well suited to AIANs since 93% report owning a mobile phone and 74% use their phones for texting (Morris & Meinrath, 2009).

In the Urban Hub’s main study, SBIRT is delivered to at-risk individuals, between ages 18 and 34 deemed at-risk of suicide, who are then offered participation in a randomized controlled trial of either receiving SBIRT alone or with additional Caring Text messages. The Urban Hub also evaluates the relative effects on the economics of resource use and quality of life of SBIRT alone versus SBIRT plus Caring Texts. These efforts are overseen by a team of practitioners, program leaders (e.g., First Nations chief executive officer, chief medical officer, Board of Directors’ chair), study staff, key scientists, and NIMH personnel. The team meets monthly to review implementation progress, monitor impacts on clinical workflow, address inefficiencies that threaten recruitment and retention, ensure participant safety, and allocate fiscal resources.

In the “The Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Hub” section, there is only one subsection, “Summary.” Please indicate where a second subsection could be added within “The Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Hub,” whether “Summary” can be deleted (just the heading), or whether the “Summary” can be formatted similar to “The Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Hub” (i.e., two separate sections).”

The Urban Hub’s long-term goal is to translate findings into practical policy, organizational change, and preventive innovations that optimize patient-centered health outcomes and reduce large suicide-related health disparities among urban AIANs. Success in this regard will capitalize on the nationwide network of UIHOs that offers a ready mechanism by which to disseminate an easily generalized and adopted intervention technology of evidence-based outcomes and known cost benefits.

➤DISCUSSION

Hallmarks of innovation across the three Collaborative Hubs have importance for ameliorating devastating youth suicide increases across the United States and the globe. Key cross-cutting scientific approaches shared by two or more Hubs that warrant continuing inquiry to advance the field include (a) long-standing CBPR research and governance processes that led to the Hubs’ innovative designs and novel approaches to suicide prevention and evaluation, (b) comprehensive ecological theoretical approaches that contextualize individual risk and protective factors in multilevel social contexts; (c) unique task-shifting and systems of care approaches that increase reach and impact on youth suicide in low-resource settings; and (d) prioritization of strength-based approaches. Each is described briefly below.

History of CBPR Leading to Hubs’ Community-Based Research Innovations

Each Hub is defined by a long history of CBPR to develop suicide prevention approaches with participating AIAN communities that have laid the ground for essential community input to understand factors, derive culturally informed interventions, and determine ethical research and evaluation designs. The resulting research has applied deep community understanding to design, implement, and evaluate culturally and contextually tailored state-of-science public health approaches to suicide prevention, with inclusive research governance models. We posit CBPR will also be essential to advancing evidence-based suicide prevention with other communities worldwide, who have similarly suffered in modern history from unjust power gradients and exploitation by researchers.

A Comprehensive Ecological Approach to Youth Suicide Prevention

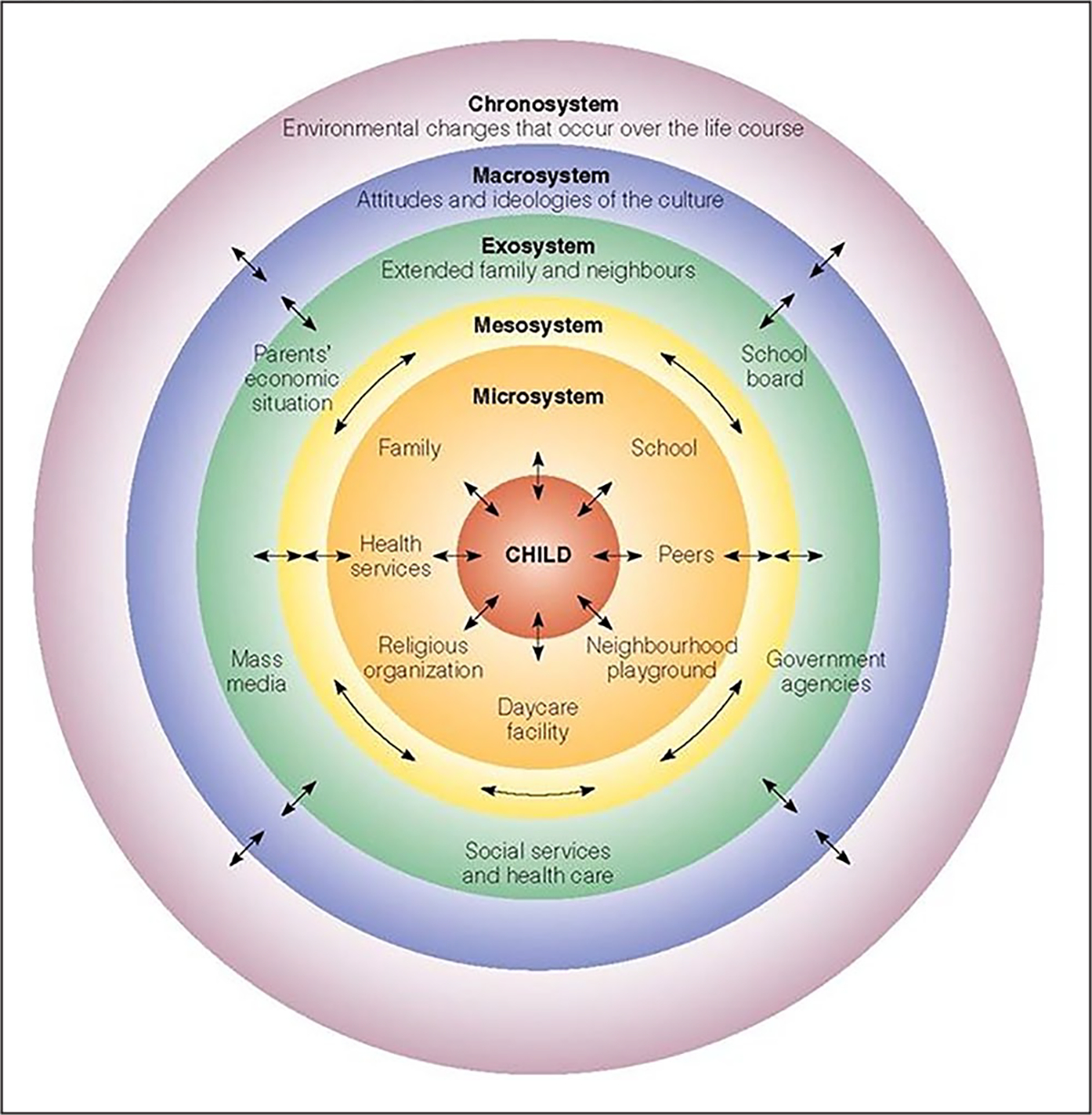

A distinguishing feature of the Collaborative Hubs includes the breadth of focus across multiple levels of the socio-ecological environment that affect youth suicide, which we explain using Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model for youth development (Guy-Evans, 2020).

The Alaska Hub focuses on rural Alaska community-level protective factors including the formal systems of tribal government, schools, health services, and churches in their mesosystem interaction with exosystem services and the informal systems of community context, values, and practices. The Southwest Hub is primarily focused on the microsystem, working to affect individual and family-level change through interventions that also foster mesosystem linkages to facilitate exosystem change. The Urban Hub evaluates clinic-based screening paired with SBIRT at a health services microsystem level, adds follow-up at the individual level, further boosted by exosystem social support linkages (i.e., Caring Contacts). Distinguishing features of all three Hubs are how each is deeply embedded in macrosystem cultural values and practices, with shared emphasis on sociohistorical contexts, while their multidecade research programs are themselves part of the chronosystem (see Figure 1). The Collaborative Hubs’ broad socio-ecological approach to multilevel community intervention models is an exemplar of comprehensive public health approaches to youth suicide. Although there is increasing national recognition that comprehensive approaches are needed to prevent youth suicide, coordinated efforts with specific populations were lacking prior to the Collaborative Hubs (Suicide Prevention Resource Center, n.d.).

FIGURE 1. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model for Youth Development.

Source: Guy-Evans (2020).

Task-Shifting and Brief Interventions in Systems of Care

The Southwest and Urban Hubs are studying task-shifting and brief intervention approaches as secondary prevention strategies to facilitate “chains” of care for youth in need, including identifying those at risk, promoting connection to care, and providing ongoing preventive intervention. Task-shifted intervention delivery to caring, trained community mental health workers is a promising strategy in communities with mental health professional shortages and where stigma or cultural preferences might misalign with Western treatment models (O’Keefe et al., 2021; Wexler et al., 2012). Globally, 80% of suicide deaths occur in low- and middle-income regions, so developing the capacity and effectiveness of community mental health workers may be key to prevent suicide in low-resourced settings (World Health Organization, 2019). The Hubs’ focus on generating evidence for the effectiveness of chain of care approaches is a national priority for NIH (NIH PAR-20-286) and may be relevant in other global settings.

Strengths-Based Approaches

The Alaska Hub adopts a protective factors framework to suicide prevention (Allen et al., 2022). The Hub focuses on identifying modifiable community-level protective determinants that can be enacted or supported to reduce youth suicide risk. This research expands on the landmark Chandler and Lalonde (1998) descriptive study identifying shared community-level factors among First Nations’ communities with low suicide rates. Through the integration of Indigenous perspectives into measurement development, data collection, and analysis, the project examines ways community context promotes wellness with implications for strength-based approaches to intervention and public health policy. Similarly, the Elders’ Resilience Curriculum evaluated by the Southwest Hub is evaluating a strengths-based culturally-grounded approach used alone or in combination with crisis intervention to positively redirect youths’ mental health trajectories. Lessons learned from these pro-culture and values-based approaches may yield prevention models for other culturally, politically, and racially marginalized communities.

Limitations

The Hubs’ research is mid-stage and has suffered delays resulting from high COVID-19 rates in AIAN communities. Thus, the Hubs are still gathering evidence to determine what practices are most impactful and scalable. However, due to the urgency of climbing rates of suicide particularly among youth of color, we feel it is prudent for prevention scientists to be aware of the work that is underway within the Collaborative Hubs and the lessons it is producing. Furthermore, determinants of AIAN youth suicide, and youth suicide in general, are complex and dynamic. Therefore, there will be an ongoing need for iterative quality improvement. Finally, the generalizability of results must be considered. Historical and ongoing trauma undergird shared behavioral and mental health risk factors among AIAN communities (Gone & Trimble, 2012). Yet, these experiences coexist with significant variation across tribes such that there is not a one-size-fits-all solution. More than 71 distinct tribes are represented by the two rural Hubs, with the Urban Hub representing AI/ANs living outside reservation/tribal lands. The diversity within and between the Hubs offers unique opportunities to observe how contexts shape public health approaches to suicide with critical lessons for other populations in terms of what matters for whom and under which circumstances.

➤IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE, POLICY, AND RESEARCH

The Collaborative Hubs’ broad-based initiatives to identify effective suicide prevention interventions, community-based practices and policies, and mechanisms for scaling, may be the most coordinated and comprehensive current efforts in the United States to address alarming increases in youth suicide (Table 2). The tribal-academic teams have three-decade-long lines of collaborative research that place their work ahead of other newer and narrower research efforts in the United States. These long-standing partnerships demonstrate the importance of authentic and engaging participatory processes as a necessary basis for rigorous and relevant research with communities that face significant health disparities. The Hubs are also advancing models for task-shifting primary and secondary suicide prevention to local community health workers, helping to fill important professional service gaps in low-resource communities. As such, the research is positioned to yield upstream and cost-effective suicide prevention models with applicability and affordability for other historically underserved communities. Finally, AIAN communities’ understanding of the cumulative effects of successive generations of historical trauma on youth and growing preference for pro-culture strengths-based approaches may have imported to other historically exploited and underserved communities and the field of suicide prevention itself.

Table 2.

Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research Drawn From the Collaborative Hubs to Reduce the Burden of Suicide Among American Indian and Alaska Native Youth

| Key implications | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Practice | Projects responsive to strengths-based design resonate with Indigenous values and cultural perspectives and may resonate more broadly with youth and other cultures worldwide. Task-shifting mental health supports to local community workforces can build local capacity and address resource deficits Findings across studies may provide a menu of cost-effective preventive interventions for future implementation. |

| Policy | The rigor of the studies will produce evidence to inform policy to support scale-up and sustainability of viable intervention approaches. |

| Research | Authentic and trust-based research and community partnerships serve as a necessary foundation for research to address health inequities. The collaboration across the Hubs to share findings and draw cross-setting insights will accelerate lessons learned, and potentially shorten time to broad-based community translation. |

Acknowledgments

Funding for the Southwest Hub for American Indian Youth Suicide Prevention Research was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant number: U19MH113136. The Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Hub is supported by NIMH grant number: U19MH113135. The Alaska Native Collaborative Hub for Research on Resilience is supported by NIMH grant number: U19MH113138. Author E.E.H. is also supported by NIMH grant number: K01MH116335. Author T.B. is supported by NIMH grant number: U19MH113136-02S1. Author V.O. is supported by NIMH grant number: 1K01MH122702.

Footnotes

Supplement Note: This article is part of the Health Promotion Practice supplement, “Public Health Practice in the Field.” The purpose of the supplement is to showcase innovative, community-centered, public health actions of SPAN, REACH, and HOP programs to advance nutrition and physical activity among priority populations in various settings. The Society for Public Health Education is grateful to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity for providing support for the issue. The entire supplement issue is available open access at https://journals.sagepub.com/toc/hppa/23/1_suppl.

REFERENCES

- Alaska Native Epidemiology Center. (2021). Alaska Native mortality: 1980–2018. anthc.org/epicenter/publications.html

- Allen J, Wexler L, & Rasmus S (2022). Protective factors as a unifying framework for strengths-based intervention and culturally responsive American Indian and Alaska Native suicide prevention. Prevention Science, 23(1), 59–72. 10.1007/s11121-021-01265-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 1999–2020 wide ranging online data for epidemiological research (WONDER), multiple cause of death files [Data file]. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

- Chandler MJ, & Lalonde C (1998). Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry, 35(2), 191–219. 10.1177/136346159803500202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois K, Kerbrat AH, DeCou CR, Atkins DC, Maleres JJ, Baker JC, & Ries RK (2019). Effect of augmenting standard care for military personnel with brief caring text messages for suicide prevention: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(5), 474–483. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwik M, Goklish N, Masten K, Lee A, Suttle R, Alchesay M, O’Keefe V, & Barlow A (2019). “Let our apache heritage and culture live on forever and teach the young ones”: Development of the elders’ resilience curriculum, an upstream suicide prevention approach for American Indian youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64, 137–145. 10.1002/ajcp.12351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwik M, Tingey L, Lee A, Suttle R, Lake K, Walkup J, & Barlow A (2016). Development and piloting of a brief intervention for suicidal American Indian adolescents. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 23, 105–124. 10.5820/aian.2301.2016.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwik M, Tingey L, Maschino A, Goklish N, Larzelere-Hinton F, Walkup J, & Barlow A (2016). Decreases in suicide deaths and attempts linked to the White Mountain Apache suicide surveillance and prevention system, 2001–2012. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 2183–2189. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlman DC, Yard E, Stone DM, Jones CM, & Mack KA (2022). Changes in suicide rates United States, 2019 and 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71, 306–312. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7108a5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faridi Z, Grunbaum JA, Gray BS, Franks A, & Simoes E (2007). Community-based participatory research: Necessary next steps. Preventing Chronic Disease. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/jul/06_0182.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann A, Bertolote JM, Wasserman D, De Leo D, Bolhari J, Botega NJ, De Silva D, Phillips M, Vijayakumar L, Värnik A, Schlebusch L, & Thanh HT (2008). Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: A randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86(9), 703–709. 10.2471/blt.07.046995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, & Trimble JE (2012). American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 131–160. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy-Evans O (2020). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. SimplyPsychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/Bronfenbrenner.html [Google Scholar]

- Haroz EE, Ivanich JD, Barlow A, O’Keefe VM, Walls M, Kaytoggy C, Suttle R, Goklish N, & Cwik M (2022). Balancing cultural specificity and generalizability: Brief qualitative methods for selecting, adapting, and developing measures for research with American Indian communities. Psychological Assessment, 34(4), 311–319. 10.1037/pas0001092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroz EE, Wexler L, Manson SM, Cwik MF, O’Keefe V, Allen J, Rasmus S, Buchwald D, & Barlow A (2021). Sustaining suicide prevention programs in American Indian and Alaska Native communities and tribal health centers. Implementation Research and Practice. 10.1177/26334895211057042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service. (2018). Urban Indian health program fact sheet. https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/uihp/

- Morris M, & Crooks C (2015). Structural and cultural factors in suicide prevention: The contrast between mainstream and Inuit approaches to understanding and preventing suicide. Journal of Social Work Practice, 29(3), 321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Morris TL, & Meinrath SD (2009). New media, technology and internet use in Indian country: Quantitative and qualitative analyses. Native Public Media. http://atalm.org/sites/default/files/NPM-NAF_New_Media_Study_2009_small.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mullany B, Barlow A, Goklish M, Larzelere-Hinton F, Cwik MF, Craig M, & Walkup JT (2009). Toward understanding suicide among youths: Results from the White Mountain Apache tribally mandated suicide surveillance system, 2001–2006. American Journal of Public Health, 99(10), 1840–1848. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Urban Indian Family Coalition. (2008). Urban Indian America: The status of American Indian & Alaska Native children & families today. https://www.aecf.org/resources/urban-indian-america/

- NCAI Policy Research Center. (2021). A first look at the 2020 American Indian/Alaska Native redistricting data. National Congress of American Indians. https://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/prc-publications/Overview_of_2020_AIAN_Redistricting_Data_FINAL_8_13_2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- New Mexico Department of Health. (2020). New Mexico substance use epidemiology profile. https://nmhealth.org/data/view/substance/2351/

- O’Keefe VM, Cwik MF, Haroz EE, & Barlow A (2021). Increasing culturally responsive care and mental health equity with indigenous community mental health workers. Psychological Services, 18(1), 84–92. 10.1037/ser0000358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe VM, Haroz EE, Goklish N, Ivanich J, Cwik MF, & Barlow A (2019). Employing a sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) to evaluate the impact of brief risk and protective factor prevention interventions for American Indian Youth Suicide. BMC Public Health, 19, Article 1675. 10.1186/s12889-019-7996-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power T, Wilson D, Best O, Brockie T, Bourque Bearskin L, Millender E, & Lowe J (2020). COVID-19 and Indigenous peoples: An imperative for action. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(15–16), 2737–2741. 10.1111/jocn.15320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmus SM, Trickett E, Charles B, John S, & Allen J (2019). The qasgiq model as an indigenous intervention: Using the cultural logic of contexts to build protective factors for Alaska Native suicide and alcohol misuse prevention. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 44–54. 10.1037/cdp0000243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skopp NA, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, Beech EH, Workman DE, Edwards-Stewart A, & Belsher BE (2022). Caring contacts for suicide prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Services. Advance online publication. 10.1037/ser0000645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2020). A comprehensive approach to suicide prevention. https://www.sprc.org/effective-prevention/comprehensive-approach

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (n.d.). Racial and ethnic disparities: American Indian and Alaska Native populations. https://www.sprc.org/scope/racial-ethnic-disparities/american-indian-alaska-native-populations

- Walter K, Walls M, Dillard D, & Kaur J (n.d.). American Indian and Alaska Native research in the health sciences: Critical considerations for the review of research applications. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Critical_Considerations_for_Reviewing_AIAN_Research_508.pdf

- Warne D, & Frizzell LB (2014). American Indian health policy: Historical trends and contemporary issues. American Journal of Public Health, 104(Suppl. 3), S263–S267. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir K (2019). Worrying trends in U.S. suicide rates. Monitor on Psychology, 50(3), 24. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/03/trends-suicide [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, Gubrium A, Griffin M, & DiFulvio G (2012). Promoting positive youth development and highlighting reasons for living in Northwest Alaska through digital storytelling. Health Promotion Practice, 14(4), 617–623. 10.1177/1524839912462390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, Rataj S, Ivanich J, Plavin J, Mullany A, Moto R, Kirk T, Goldwater E, Johnson R, & Dombrowski K (2019).Community mobilization for rural suicide prevention: Process, learning and behavioral outcomes from promoting community conversations about research to end suicide (PC CARES) in Northwest Alaska. Social Science & Medicine, 232, 398–407. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, Silveira ML, & Bertone-Johnson E (2012). Factors associated with Alaska Native fatal and nonfatal suicidal behaviors 2001–2009: Trends and implications for prevention. Archives of Suicide Research, 16(4), 273–286. 10.1080/13811118.2013.722051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2019). Suicide: Key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

- Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, Sheppard M, Gates A, Stein Z, Hartnett K, Kite-Powell A, Rodgers L, Adjemian J, Ehlman DC, Holland K, Idaikkadar N, Ivey-Stephenson A, Martinez P, Law R, & Stone DM (2021). Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70, 888–894. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1externalicon [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MM, Stevens A, Galipeau J, Pirie T, Garritty C, Singh K, Yazdi F, Golfam M, Pratt M, Turner L, Porath-Waller A, Arratoon C, Haley N, Leslie K, Reardon R, Sproule B, Grimshaw J, & Moher D (2014). Effectiveness of brief interventions as part of the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) model for reducing the nonmedical use of psychoactive substances: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 3, 50. 10.1186/2046-4053-3-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]