Abstract

Background

COVID-19 pandemic has affected various aspects of human life. Bank employees who are more in contact with people are more likely to be infected during the pandemic situation. Moreover, mental, physical and social impacts of COVID-19 are more intense among these employees.

Objective: this study aims to determine the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on bank employees’ health and life satisfaction in Iran.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted during the fifth wave of COVID-19 from July to October 2021. The population included all the employees of Tejarat Bank in 20 provinces of Iran, 350 of whom were selected using the multi-stage cluster sampling method. The data were collected by demographic questionnaire, 12-item short-form (SF-12) personal health assessment survey and satisfaction with life scale (SWLS). The objective of the study was examined by the structural equation modeling (SEM).

Results

The results showed the two default models of health function (CFI = 0.95) and life satisfaction (CFI = 0.99) had acceptable fit. Assessing the bank employees with COVID-19 revealed this disease had no direct impact on life satisfaction (β = −0.05, P = 0.28) and health function (β = 0.04, P = 0.48). However, it had a direct impact on physical function (β = −0.18, P = 0.001) and, consequently, an indirect impact on life satisfaction. Moreover, low mental function reduced life satisfaction.

Conclusion

COVID-19 infection had no direct impact on life satisfaction. However, it had an indirect and positive impact on it. Considering gender showed COVID-19 infection had a direct and positive impact on life satisfaction among women. The employees who recovered from COVID-19 infection reported higher life satisfaction after returning to work for various reasons than those who never got it.

Keywords: Covid-19, Life satisfaction, Health, Bank employees, Iran, Return at work, Recovery from infection

1. Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic, first reported in China in late 2019, has been a major concern for many countries and businesses. According to World Health Organization [1], COVID-19 was introduced as a public health emergency of international concern on January 31, 2020, and a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [2]. Iran, with its high prevalence and mortality rates, is among the first countries affected by COVID-19 [3]. Accordingly, the government took strict measures to prevent the spread of the virus such as closure of schools and businesses, curfews, telecommuting, travel restrictions, etc. [4,5].

Health center staff have been at the forefront of the fight against the disease without the opportunity of being laid off or telecommute during the outbreak [6,7]. Other jobs like bank employees also continued to serve during these difficult conditions, but they have not received great attention. According to Iran's National Headquarter for Combating Coronavirus (NHCC), the probability of a bank employee being infected with COVID-19 is about 7.5 times higher than that of an ordinary citizen [8]. From the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, bank employees were among the first groups affected, 260 of whom have unfortunately died from this disease so far [8].

These working conditions could have a significant impact on employees’ life satisfaction and health. Life satisfaction has recently been a topic of interest for researchers and addressed by positive psychology [[9], [10], [11]]In general, positive psychology examines well-being through the experiences of individuals such as socioeconomic status [12,13], employment [14], physical health [13], income [15] etc. COVID-19 pandemic is among the most recent human experiences.

One study on Weibo (one of China's most popular social media) users before and after the COVID-19 outbreak showed negative emotions such as anxiety, depression and indignation increased and life satisfaction and some positive emotions decreased [16]. Another study conducted one month after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in China revealed the adults who did not work at the time of the outbreak were worse off in terms of life satisfaction, mental and physical health and distress [17]. Studies have demonstrated women are more likely to be less satisfied with life and experience more anxiety and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic [18,19].

The impact of individuals’ health status on life satisfaction and conflicting with the disease is another concern that some studies have addressed. Physical fitness in the current lifestyle is considered as a means for achieving a better quality of life. Physical activity has many health benefits, including improving cardiorespiratory function and boosting the immune system [20,21] Furthermore, the current state of health and exercise can affect the correlation between life satisfaction and COVID-19 severity [18]. WHO launched “be active during COVID-19” campaign with recommendations for weekly levels of physical activity that could be achieved in the limited space of home without any specific equipment [22] Zhang et al. found that life satisfaction was negatively correlated with hours of exercise, suggesting that physically active people might be more susceptible to poor well-being during the quarantine [18].

Given that bank employees are one of the high-risk groups due to their occupational nature and a potential source of virus transmission in the community, this study aims to examine life satisfaction and health status of these people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methodology

This cross-sectional study was performed during the fifth wave of COVID-19 in Iran. The population included the employees of Tejarat Bank who were exposed to COVID-19 to varying degrees. The employees who worked directly with clients and were less likely to be laid off or telecommute were selected from 20 provinces of Iran using random cluster sampling method. The sample size was determined to be 350 people. Questionnaires were set up electronically and sent to about 500 individuals via WhatsApp, 350 of whom completed them. Necessary arrangements were made with the central headquarters in Tehran to have the list of the personnel of the selected provinces.

3. Measures

3.1. Personal health survey

SF-12 personal health survey assesses the standard physical and mental health function. This scale that was previously translated into Persian and localized by Pakpour et al. was evaluated [23,24]. SF-12 scale consists of 12 items and 8 dimensions: Physical function (2 items), physical role (2 items), body pain (1 item), general health (1 item), vitality (1 item), social function (1 item), role of emotional health (2 items) and mental health (2 items). The eight dimensions provide the two composite scores of physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) health scales, ranging from 0 to 100. Higher SF-12 scores indicate better health. Cronbach's alpha as internal consistency reliability was obtained as 0.89 and 0.90 for the physical and mental scales, respectively and 0.746 for total scale.

Scoring is computed using the scores of twelve questions and range from 0 to 100, where a zero score indicates the lowest level of health measured by the scales and 100 indicates the highest level of health.

3.2. Life satisfaction

Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) was used to assess life satisfaction. This scale consists of 5 items, scored based on the 5-point Likert scale [25]. Diener et al. distributed SWLS among a group of students and evaluated its validity and reliability. Two months after implementation, the test-retest correlation coefficient and Cronbach's alpha coefficient were obtained as 0.82 and 0.87, respectively [25]. Schimmack et al. (2002) assessed the reliability of SWLS and reported its Cronbach's alpha coefficient as 0.90, 0.82, 0.79, 0.76 and 0.61 among American, German, Japanese, Mexican and Chinese nations, respectively [26]. In Iran, Mozaffari evaluated the validity of the Iranian version of SWLS by comparing it with the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) and reported a positive and significant correlation between these two scales [27]. Cronbach's alpha was obtained 0.86 for SWLS in current study.

Scoring of this scale is based on the Likert scale, which is scored from 1 to 5.

| Lower score limit | average score limit | upper score limit |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 15 | 25 |

-

-

If the scores of the questionnaire are between 5 and 10, the level of satisfaction with life in this society is weak.

-

-

If the scores of the questionnaire are between 10 and 15, the level of satisfaction with life is at an average level.

-

-

If the scores are above 15, the level of life satisfaction is very good.

3.3. Data analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the research question. Prior to conducting SEM analysis, the measurement models for each latent factor were examined by Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs), and factor loadings ≥0.5 for each factor indicator as well as acceptable fit indices for the overall factor were to ensure adequate measures. Model goodness of fit was evaluated by χ2 and degree freedom, the comparative fit index (CFI) (good fit >0.90), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA <0.08). In the analysis of this study, 1000 bootstrap samples were used to examine the indirect effects of morbidity with Covid-19 and quality of life (physical and mental functions) on the satisfaction of life. The bootstrapping method also adjusts standard errors, so they are appropriate for indirect effects [28]. To test for gender differences, the multiple group analysis was used to test invariance of regression coefficients. Preparing data and descriptive analysis were performed in STATA 16, and Structural equation modeling analyses were conducted in Mplus 8.

4. Results

The correlation, means, and standard deviations for indicators are shown in Table 1 for the total sample. Table 1 also includes skewness and kurtosis that help to evaluate the normality of the distributions. As a preliminary step, separate measurement models were fit for life satisfaction and health functions (Table 2). The both models demonstrated acceptable model fit, CFI = .95, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.09 for heath functions (with two factors: Physical function and Mental function), and CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.02, RMSEA = 0.054 for Life Satisfaction scale (Table 2). Each of factors were compared across the socio-demographic variables and morbidity to Covid-19 infection (Table 3). 74.1% of participants experienced infection with Covid-19. There was significant difference for physical (P = 0.004) and mental (P = 0.01) functions between those with Covid-19 and those did not. Also, here was significant difference for physical (P = 0.04) and mental (P < 0.001) functions between female and male.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the total sample (N = 355).

| Sf2 | Sf3 | Sf4 | Sf5 | Sf8 | Sf9 | Sf10 | Sf11 | Sw1 | Sw2 | Sw3 | Sw4 | Sw5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sf2 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Sf3 | 0.67 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Sf4 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sf5 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.76 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Sf8 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Sf9 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Sf10 | −0.27 | −0.27 | −0.31 | −0.37 | −0.48 | −0.44 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Sf11 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.64 | −0.59 | 1.00 | |||||

| Sw1 | −0.30 | −0.23 | −0.34 | −0.36 | −0.44 | −0.38 | 0.45 | −0.48 | 1.00 | ||||

| Sw2 | −0.26 | −0.23 | −0.33 | −0.37 | −0.43 | −0.37 | 0.43 | −0.46 | 0.76 | 1.00 | |||

| Sw3 | −0.28 | −0.24 | −0.29 | −0.36 | −0.39 | −0.40 | 0.43 | −0.49 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 1.00 | ||

| Sw4 | −0.24 | −0.15 | −0.29 | −0.30 | −0.38 | −0.32 | 0.37 | −0.37 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 1.00 | |

| Sw5 | −0.15 | −0.14 | −0.11 | −0.13 | −0.22 | −0.22 | 0.25 | −0.27 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 1.00 |

| Mean | 1.14 | 1.16 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.15 |

| SD | 2.24 | 2.52 | 2.53 | 2.32 | 2.93 | 2.70 | 3.28 | 2.92 | 2.74 | 2.75 | 3.32 | 2.97 | 2.32 |

| Skewness | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.44 | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.35 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.17 | −0.52 | −0.08 | 0.71 |

| Kurtosis | −0.53 | −0.70 | −0.71 | −0.60 | −0.60 | −0.60 | −0.62 | −0.75 | −1.11 | −1.03 | −0.71 | −1.21 | −0.39 |

Note. All paired correlations were significant (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Factor Loadings of Latent Factor name and relevant indicators.

| Physical Function [46] | λ | Θ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF2 | (The following two questions are about activities you might do during a typical day. Does YOUR HEALTH NOW LIMIT YOU in these activities? If so, how much?) MODERATE ACTIVITIES, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf: | 0.76 | 0.65 |

| SF3 | Climbing SEVERAL flights of stairs: | 0.63 | 0.77 |

| SF4 | (During the PAST 4 WEEKS have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular activities AS A RESULT OF YOUR PHYSICAL HEALTH?) ACCOMPLISHED LESS than you would like: | 0.85 | 0.53 |

| SF5 | Were limited in the KIND of work or other activities: | 0.87 | 0.50 |

| Mental Function (MF) | |||

| SF8 | During the PAST 4 WEEKS, how much did PAIN interfere with your normal work (including both work outside the home and housework?) | 0.80 | 0.60 |

| SF9 | (The next three questions are about how you feel and how things have been DURING THE PAST 4 WEEKS. For each question, please give the one answer that comes closest to the way you have been feeling. How much of the time during the PAST 4 WEEKS)? Have you felt calm and peaceful? | 0.78 | 0.63 |

| SF10 | Did you have a lot of energy? | −0.63 | 0.77 |

| SF11 | Have you felt downhearted and blue? | 0.83 | 0.56 |

| Fit indices: CFI = .95, TLI = .94, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.09. Cronbach's Alpha = 0.75. Also the correlation coefficient PF with MF was 0.60. | |||

| Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) | |||

| Sw1 | In most ways my life is close to my ideal | 0.85 | 0.53 |

| Sw2 | The conditions of my life are excellent. | 0.89 | 0.46 |

| Sw3 | I am satisfied with my life | 0.82 | 0.58 |

| Sw4 | So far I have gotten the important things I want in life | 0.74 | 0.68 |

| Sw5 | If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. | 0.45 | 0.89 |

| Fit indices: CFI = .99, TLI = .98, SRMR = 0.02, RMSEA = 0.054. Cronbach's Alpha = 0.86. | |||

Table 3.

Comparison across the socio-demographic variables and morbidity to Covid-19 infection.

| SLWS |

PF |

MF |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| job status | |||||

| Employed at work | 332 | 93.5 | 14.2 ± 4.5 | 9.5 ± 3.5 | 11.7 ± 2.3 |

| Employed remotely | 12 | 3.4 | 13.5 ± 4.3 | 11.0 ± 4.9 | 12.8 ± 1.8 |

| Leave due to Covid 19 | 7 | 2.0 | 11.4 ± 5.7 | 13.1 ± 5.5 | 12.7 ± 2.8 |

| lost job because of Covid 19 | 4 | 1.1 | 11.7 ± 5.1 | 8.5 ± 6.4 | 13.7 ± 2.2 |

| P-value | 0.271 | 0.035 | 0.103 | ||

| gender | |||||

| female | 106 | 29.9 | 13.5 ± 4.4 | 10.5 ± 3.8 | 12.6 ± 2.2 |

| male | 249 | 70.1 | 14.3 ± 4.6 | 9.2 ± 3.6 | 11.5 ± 2.3 |

| P-value | 0.122 | 0.04 | <0.001 | ||

| family_number | |||||

| 1 | 16 | 4.5 | 13.7 ± 6.0 | 9.3 ± 5.1 | 11.6 ± 2.7 |

| 2 | 38 | 10.7 | 13.8 ± 4.5 | 9.0 ± 3.3 | 11.9 ± 2.4 |

| 3 or 4 | 239 | 67.3 | 14.1 ± 4.6 | 9.6 ± 3.7 | 11.8 ± 2.3 |

| >5 | 62 | 17.5 | 14.3 ± 4.1 | 9.9 ± 3.5 | 11.6 ± 2.2 |

| P-value | 0.923 | 0.671 | 0.863 | ||

| education | |||||

| diploma | 27 | 7.6 | 13.8 ± 4.1 | 9.6 ± 3.7 | 12.2 ± 2.5 |

| Bachelor | 179 | 50.4 | 14.1 ± 4.5 | 10.1 ± 3.6 | 11.9 ± 2.4 |

| master and up | 149 | 42.0 | 14.2 ± 4.6 | 9.0 ± 3.7 | 11.6 ± 2.3 |

| P-value | 0.911 | 0.033 | 0.378 | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 287 | 80.9 | 13.9 ± 4.6 | 9.7 ± 3.7 | 11.8 ± 2.3 |

| single | 68 | 19.2 | 14.6 ± 4.8 | 9.1 ± 3.8 | 11.7 ± 2.3 |

| P-value | 0.302 | 0.2 | 0.67 | ||

| Covid 19 | |||||

| yes | 263 | 74.1 | 13.9 ± 4.7 | 9.9 ± 3.7 | 12.0 ± 2.3 |

| no | 92 | 25.9 | 14.4 ± 4.1 | 8.6 ± 3.5 | 11.3 ± 2.5 |

| P-value | 0.362 | 0.004 | 0.01 | ||

| Age cat | |||||

| <40 | 152 | 42.8 | 14.2 ± 4.5 | 9.1 ± 3.6 | 11.7 ± 2.4 |

| >40 | 203 | 57.2 | 14.02 ± 4.5 | 10.0 ± 3.7 | 11.9 ± 2.3 |

| P-value | 0.692 | 0.032 | 0.55 | ||

SLWS: Satisfaction with life scale.

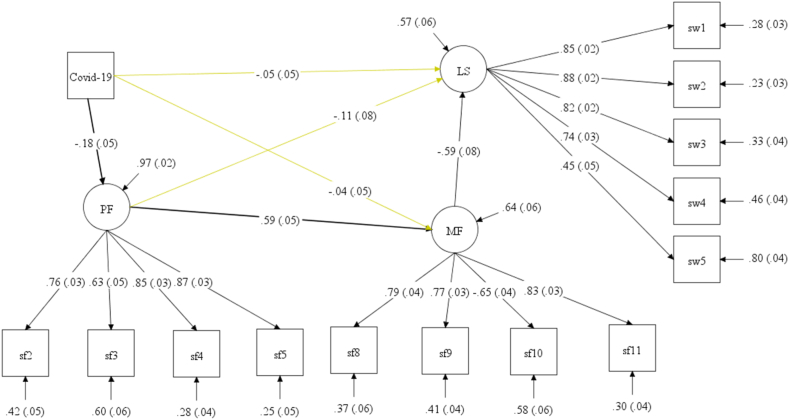

We begin by examining a baseline model of life satisfaction (see Fig. 1). In this model, morbidity with Covid1-19 is not directly associated with changes in life satisfaction (β = −0.05, P = 0.28), the mental function (β = 0.0.4, P = 0.48), but is directly associated with change physical function (β = −0.18, P = 0.001). The indirect effects from Covid-19 → PF → MF → LS (β = 0.06, P = 0.008) and total indirect (β = 0.11, P = 0.004) were significant (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Fit indices: Chi-square = 146.03; df = 72; Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.054, 90% CI: (0.041, 0.066); Akaike's information criterion (AIC) = 11612.18; Bayesian information criterion (BIC) = 11786.43; Comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.963; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.953; Standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) = 0.038.

Table 4.

Direct and indirect effects on life satisfaction.

| effects | Total sample | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0.05 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.09) | 0.13 (0.06)* |

| Direct (Covid-19 → LS) | −0.05 (0.05) | −0.20 (0.08)* | 0.01 (0.06) |

| Total Indirect | 0.11 (0.03)** | 0.09 (0.06) | 0.13 (0.05)** |

| Indirect 1: (Covid-19 → PF → LS) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) |

| Indirect 2: (Covid-19 → MF → LS) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.04) |

| Indirect 3: (Covid-19 → PF → MF → LS) | 0.06 (0.02) ** | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.03)* |

Note. LS: life satisfaction; PF: physical function, MF: mental function. *P-value <0.05, **P-value <0.01, ***P-value <0.001.

4.1. Female group

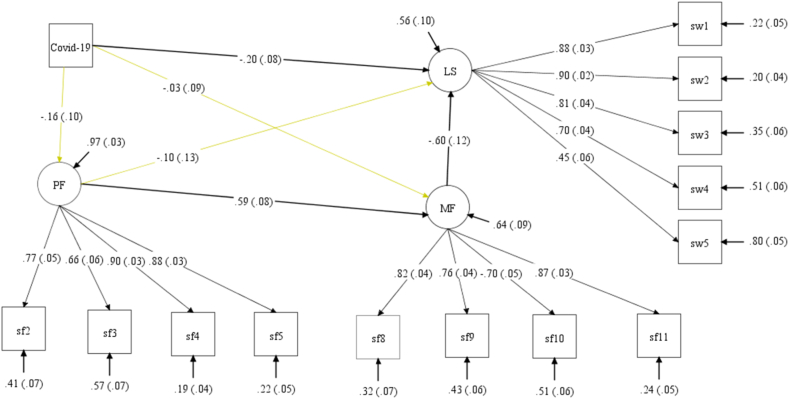

In this model (see Fig. 2), morbidity with Covid1-19 is directly associated with negative changes in life satisfaction (β = −0.20, P = 0.017), but is not directly associated with change physical function (β = −0.16, P = 0.09) and change mental function (β = −0.03, P = 0.71). The indirect effects from all paths of Covid-19 → LS were not significant (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Female. Fit indices: Chi-square = 117.41; df = 72; Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.077, 90% CI: (0.05, 0.101); Akaike's information criterion (AIC) = 3362.13; Bayesian information criterion (BIC) = 3482.03; Comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.939; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.922; Standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) = 0.061.

4.2. Male group

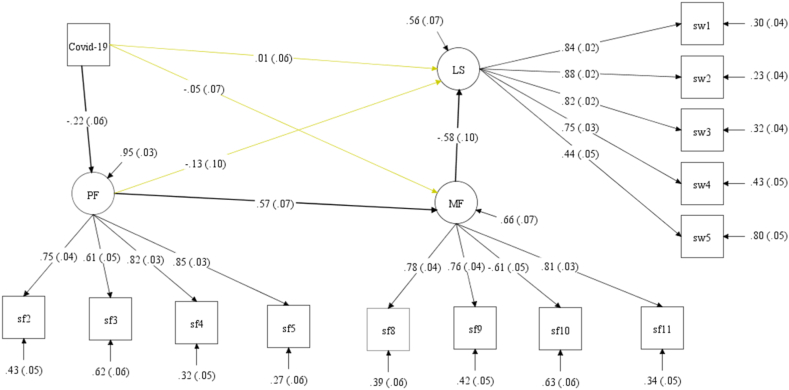

In this model (see Fig. 3), morbidity with Covid1-19 is not directly associated with changes in life satisfaction (β = 0.01, P = 0.94), the mental function (β = −0.05, P = 0.46), but is directly associated with change physical function (β = −0.22, P = 0.001). The indirect effects from Covid-19 → PF → MF → LS (β = 0.07, P = 0.017) and total indirect (β = 0.13, P = 0.005) were significant (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Male. Fit indices: Chi-square = 114.45; df = 72; Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.049, 90% CI: (0.031, 0.065); Akaike's information criterion (AIC) = 8265.79; Bayesian information criterion (BIC) = 8424.07; Comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.968; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.960; Standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) = 0.038.

5. Discussion

The results showed getting COVID-19 had no direct effect on life satisfaction by ignoring the impact of gender. However, it had an indirect and positive impact on life satisfaction. Moreover, low mental function reduced life satisfaction. Previous studies have shown mental function has a direct impact on life satisfaction [9,29]. Our results revealed changes in mental function were affected by physical function, so that enhancing physical function could improve mental function. Studies have emphasized regular physical activity could improve mental function [30]. The results indicated COVID-19 reduced physical function. Belli et al. found that about half of the post-COVID-19 patients manifested severe physical dysfunction [31]. Considering the significant impact of COVID-19 on physical function as well as the impact of physical function on mental function and, finally, the impact of mental function on life satisfaction, the indirect and positive impact of QOVID-19 on life satisfaction could be explained. In other words, getting COVID-19 increased life satisfaction. This indirect positive correlation seems logical, because the participants rated life satisfaction based on their present and past feelings. Moreover, the individuals who recovered from COVID-19 and resumed working at their workplace had a relative satisfaction with themselves and their lives. As, previous research has demonstrated that traumatic experiences such as Covid-19 infection can lead to positive reactions [32].

Previous studies have revealed recovery from the disease has a positive effect on quality of life and life satisfaction [33,34]. According to Gundogan's study, psychological resilience could be the reason for this high satisfaction [35]. However, psychological resilience was not evaluated in the present study, which is recommended to be considered in future research. Psychological resilience is defined as an individual's ability to stay strong in the face of negative conditions and overcome them [36]. Kai Hou et al. indicated high psychological resilience was associated with better mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [37].

Zhang et al. conducted a study to assess the health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults one month after the outbreak of COVID-19 in China and found that the employees who stopped working had poorer mental and physical conditions as well as higher distress [17]. In general, returning to normal working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic could increase life satisfaction. It seems that even in conditions of being afraid of contracting an infectious disease, stopping working could have psychological negative consequences.

Another study showed having a dynamic work environment during the COVID-19 outbreak could improve the meaning of life and life satisfaction. Therefore, it seems that returning to a dynamic work environment after recovery from COVID-19 could have positive psychological impacts such as life satisfaction [38].

Moreover, the correlation between getting COVID-19 and life satisfaction was examined considering gender as a moderator variable. The results showed getting COVID-19 had a direct impact on life satisfaction among women. As studies have indicated women are psychologically skeptical and more afraid of the consequences of COVID-19 or full recovery from this disease, this finding seems logical [[39], [40], [41]]. In contrast, getting COVID-19 had no direct effect on life satisfaction among men. However, the indirect effect of COVID-19 on life satisfaction and physical-mental function was significant and positive. Thus, getting COVID-19 indirectly had a positive effect on men's life satisfaction.

Men considered getting COVID-19 and recovering from it as overcoming this problem, which caused them to feel satisfied with themselves and their lives. This argument could be justified by examining the effect of COVID-19 on physical function. Getting COVID-19 had a negative effect on men's physical function and they felt satisfied after recovering from this disease and returning to their normal physical function, while low mental function of men and women had a negative effect on life satisfaction [42,43].

One study on the psychological effects of quarantine and lockdown among German adolescents showed making it mandatory to stay home had greater adverse effect on life satisfaction among girls. Girls were more vulnerable when pandemic restrictions were applied and life satisfaction was more negatively affected among women. These results were consistent with those of the present study suggesting that life satisfaction was higher among women after getting the virus [44].

Another study on the fear of illness, family conflicts and life satisfaction among school administrators in Turkey showed female administrators, despite reporting higher fear scores than males at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, gained higher life satisfaction score during this period. These results were in line with those of our study in terms of differences in life satisfaction between men and women during the COVID-19 pandemic [45].

5.1. Limitations

This study had several limitations: 1. This study had a cross-sectional design; so, no causal argument could be deduced from it. It is recommended to use longitudinal and cohort designs in future research 2. This study could have a good internal validity, because it included a homogeneous population (bank employees) considering many socio-demographic components such as lack of significance of life satisfaction/quality of life (physical/mental function) in terms of job status, age groups, marital status, educational status, etc. However, generalizing the results to other populations should be done with caution 3. The obtained results might be influenced by time, because fear of the unknown, social panic, etc. At the beginning of the pandemic could have direct and indirect impacts on life satisfaction and quality of life. Therefore, it is recommended to perform a review study or meta-analysis to examine the obtained results during the pandemic (at the early, middle and late stages of the pandemic). Finally, the long – covid19 effect such as fatigue, depression, difficulty on concentration and etc. Not considered in this study.

6. Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemic had no direct impact on life satisfaction. However, it had an indirect and positive impact on life satisfaction. Considering gender showed COVID-19 had a direct and positive impact on life satisfaction among women. The employees who recovered from COVID-19 reported higher life satisfaction after returning to work for various reasons than those who never got it. Different dimensions of COVID-19 pandemic impacts still need to be investigated. The results revealed COVID-19 had indirect and direct impacts on life satisfaction among men and women, respectively. Women were more influenced by life satisfaction than men. This impact was positive in both groups. Therefore, it is recommended that managers, while supporting employees during the illness, attempt to return employees to normal work conditions after recovery and strengthen the sense of recovery and life satisfaction among employees.

Author contribution statement

Maysam Rezapour: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. Meysam Aminizadeh: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. Hadis Amiri: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data. Asghar Tavan; Mohsen Aminizadeh: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Health in Disasters and Emergencies Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran. We would like to thank the Tejarat Bank for helping us to collect the data.

References

- 1.Group, W.A.W.J.A The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development. reliability and feasibility. 2002;97(9):1183–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker S.R., et al. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Covid-induced Economic Uncertainty. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asaadi M., H.J.J.o.H.A. Daliri Evaluating the Effect of Poverty and Economic Inequality on the Corona Pandemic in Iran and the World. 2021;24(2):20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molavi-Taleghani Y., Ebrahimpour H., Sheikhbardsiri H. A proactive risk assessment through healthcare failure mode and effect analysis in pediatric surgery department. J. Compr. Pediatr. 2020;11(3) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheikhbardsiri H., et al. Observance of patients' rights in emergency department of educational hospitals in south-east Iran. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare. 2020;13(5):435–444. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheikhbardsiri H., et al. Workplace violence against prehospital paramedic personnel (city and road) and factors related to this type of violence in Iran. J. Interpers Violence. 2022;37(13–14):NP11683–NP11698. doi: 10.1177/0886260520967127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baniasadi H., et al. Effect of massage on behavioural responses of preterm infants in an educational hospital in Iran. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2019;37(3):302–310. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2019.1578866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iran, c.b.o.t.I.r.o., 2021.

- 9.Guney S., et al. Dimensions of mental health. life satisfaction, anxiety and depression: a preventive mental health study in Ankara University students population. 2010;2(2):1210–1213. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diener E.J.A.p. New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. 2012;67(8):590. doi: 10.1037/a0029541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheikhbardsiri H., et al. Qualitative study of health system preparedness for successful implementation of disaster exercises in the Iranian context. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022;16(2):500–509. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H.-K. In the COVID-19 era, effects of job stress, coping strategies, meaning in life and resilience on psychological well-being of women workers in the service sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19(16):9824. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19169824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellis M.A., et al. Variations in risk and protective factors for life satisfaction and mental wellbeing with deprivation: a cross-sectional study. 2012;12(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolan P., Layard R., Metcalfe R. 2011. Measuring Subjective Well-Being for Public Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fergusson D., et al. Life satisfaction and mental health problems (18 to 35 years) 2015;45(11):2427–2436. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S., et al. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: a study on active Weibo users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(6) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang S.X., et al. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang S.X., et al. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C., et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(5) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duggal N.A., et al. Major features of immunesenescence, including reduced thymic output, are ameliorated by high levels of physical activity in adulthood. Aging Cell. 2018;17(2) doi: 10.1111/acel.12750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weyh C., Krüger K., Strasser B. Physical activity and diet shape the immune system during aging. Nutrients. 2020;12(3) doi: 10.3390/nu12030622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Organization W.H. 2020. Be Active during COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware J.E., Jr., Kosinski M., Keller S.D.J.M.c. 1996. A 12-Item Short-form Health Survey: Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity; pp. 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pakpour A.H., et al. 2011. Validity and Reliability of Short Form-12 Questionnaire in Iranian Hemodialysis Patients. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diener E., et al. The satisfaction with life scale. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schimmack U., et al. Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: integrating process models of life satisfaction. 2002;82(4):582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayani A.A., Koocheky A.M., Goodarzi H.J.D.P. The reliability and validity of the satisfaction with life scale. 2007;3(11):259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kline R.B. Guilford press; New York: 2005. Methodology in the Social Sciences. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fergusson D.M., et al. Life satisfaction and mental health problems (18 to 35 years) Psychol. Med. 2015;45(11):2427–2436. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McPhee J.S., et al. Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. 2016;17(3):567–580. doi: 10.1007/s10522-016-9641-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belli S., et al. Low physical functioning and impaired performance of activities of daily life in COVID-19 patients who survived hospitalisation. 2020;56(4) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02096-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finstad G.L., et al. Resilience, coping strategies and posttraumatic growth in the workplace following COVID-19: a narrative review on the positive aspects of trauma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18(18):9453. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laudet A.B., White W.L. Recovery capital as prospective predictor of sustained recovery, life satisfaction, and stress among former poly-substance users. Subst. Use Misuse. 2008;43(1):27–54. doi: 10.1080/10826080701681473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Koppenhagen C.F., et al. Recovery of life satisfaction in persons with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009;88(11) doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181b71afe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gundogan S. The mediator role of the fear of COVID-19 in the relationship between psychological resilience and life satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 2021;40(12):6291–6299. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01525-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutter M.J. Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy. 1999;21(2):119–144. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hou W.K., et al. Probable anxiety and components of psychological resilience amid COVID-19: a population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;282:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trzebiński J., et al. Reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. the influence of meaning in life, life satisfaction, and assumptions on world orderliness and positivity. 2020;25(6–7):544–557. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahorsu D.K., et al. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addiction. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broche-Pérez Y., et al. 2020. Gender and Fear of COVID-19 in a Cuban Population Sample; pp. 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laufer A., Shechory Bitton M.J.W., health Gender differences in the reaction to COVID-19. 2021;61(8):800–810. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2021.1970083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu C., et al. Health-related quality of life of hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: an initial exploration in Nanning city, China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021;274 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W., et al. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. 2020;16(10):1732. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Laan S.E., et al. Gender-Specific Changes in Life Satisfaction After the COVID-19–Related Lockdown in Dutch Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. 2021;69(5):737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karakose T., Yirci R., Papadakis S.J.S. Exploring the interrelationship between covid-19 phobia, work–family conflict, family–work conflict, and life satisfaction among school administrators for advancing sustainable management. 2021;13(15):8654. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumpfer K.L. Resilience and Development. Springer; 2002. Factors and processes contributing to resilience; pp. 179–224. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.