Abstract

Finding eco-friendly alternatives for antibiotics in treating bacterial diseases affecting the aquaculture sector is essential. Herbal plants are promising alternatives, especially when combined with nanomaterials. Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaves extract was synthesized using a chitosan nanocapsule. Chitosan neem nanocapsule (CNNC) was tested in-vitro and in-vivo against the Aeromonas sobria (A. sobria) challenge in Nile tilapia. A preliminary experiment with 120 Nile tilapia was conducted to determine the therapeutic dose of CNNC, which was established to be 1 mg/L. A treatment study was applied for seven days using 200 fish categorized into four groups (10 fish/replicate: 50 fish/group). The first (control) and second (CNNC) groups were treated with 0 and 1 mg/L CNNC in water without being challenged. The third (A. sobria) and fourth (CNNC + A. sobria) groups were treated with 0 and 1 mg/L CNNC, respectively, and challenged with A. sobria (1 × 107 CFU/mL). Interestingly, CNNC had an in-vitro antibacterial activity against A. sobria; the minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration of CNNC against A. sobria were 6.25 and 12.5 mg/mL, respectively. A. sobria challenge caused behavioral alterations, skin hemorrhage, fin rot, and reduced survivability (60%). The infected fish suffered a noticeable elevation in the malondialdehyde level and hepato-renal function markers (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and creatinine). Moreover, a clear depletion in the level of the antioxidant and immune indicators (catalase, reduced glutathione, lysozymes, nitric oxide, and complement 3) was obvious in the A. sobria group. Treatment of the A. sobria-challenged fish with 1 mg/L CNNC recovered these parameters and enhanced fish survivability. Overall, CNNC can be used as a new versatile tool at 1 mg/L as a water treatment for combating the A. sobria challenge for sustainable aquaculture production.

Keywords: Antimicrobial activity, Chitosan neem nanocapsule, Aeromonas sobria, Nile tilapia, Immunity

1. Introduction

The aquaculture sector has significant importance for millions of people globally, particularly in poor nations where the industry plays a crucial role in job opportunities, economic empowerment, and enhancing the nutritional status of poor people [1]. The consumption of fish as a main source of protein has significantly grown in recent decades among the poorest people [2]. So, many nations are working hard to increase the amount of fish production to meet the consumer's demands [3,4].

Diseased problems cause big mortalities and financial losses, consequently hindering the sustainable development of aquaculture (SDA) [5]. Worldwide, bacterial fish illnesses result in significant economic losses [6]. One of the most prevalent diseases, the bacterial species from the genus Aeromonas, is mostly to blame. Aeromonas spp. Infection severely impacts this fish's global productivity and survival rates [7]. A. sobria is a Gram-negative bacterium that induces great losses in fish farms. Infected fish with A. sobria die from hemorrhagic septicemia, ascites, and ulcer development. Extracellular hemolysin and aerolysin synthesis are two important virulence genes responsible for developing septicemia [8].

Treating bacterial diseases in aquaculture with antibiotics leads to the antibiotic resistance hazard, which risks consumer well-being [9]. Using antibiotics to treat aquatic animals can result in several difficult issues, including the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains, antibiotic remnants present in the fish muscles that impact the consumers' well-being, and environmental pollution [10,11]. To minimize the harmful effects of antibiotic usage, developing promising, safe, ecologically friendly alternatives is vital [12].

The herbal plants are a safe and eco-friendly alternative to antibiotics. The majority of molecules derived from plants are phytochemicals and secondary metabolites, which are categorized into a variety of classes and mostly function as antimicrobials such as tannins, coumarins, terpenes, quinones, phenolics, polyphenols, flavonoids, lectins, polypeptides, and saponins [13,14].

Neem (Azadirachta indica) is a large evergreen tree with fragrant foliage and tasty fruits. This tree's anti-inflammation, immunological, and anti-ulcer properties have made it widely employed for various purposes [15,16]. Additionally, every part of the neem tree possesses various antifungal, antibacterial, and antiviral properties and antioxidant properties [17,18]. The neem leaves had antibacterial activity against the Staphylococcus aureus and A. hydrophila isolated from singhi (Heteropneustes fossilis) and mrigal (Cirrhinus mrigala) [19]. Neem leaves extract had antibacterial activity against A. veronii, A. hydrophila, Acinetobacter junii, A. tandoii, and Pseudomonas stutzeri isolated from blackspot barb (Dawkinsia filamentosa) [20].

As a superior alternative to conventional methods that rely on the preparation of pharmaceutical drugs in biomedical applications, novel advances in nanotechnology have aroused the interest of researchers in a variety of scientific fields and aquacultures. Examples of novel advances are nanostructured materials such as nanoparticles, conjugates, and nanocapsules [21]. Nano-medicine uses various nanotechnology tools to create quicker and more effective treatments for illnesses or disease management [22]. One of the materials employed the most frequently in nanotechnology is chitosan, a degradable polysaccharide with various applications [23,24]. Because nanostructured materials may amplify the action of plant extracts, decreasing the needed dose and adverse effects, and enhancing activity, employing the nanocapsule formulation has numerous benefits over using the herbal addition. This is because it has been widely advocated to combine herbal medicine with nanotechnology. Throughout the treatment period, the active component can be administered by nanosystems at an appropriate concentration, sending it to the intended action location. Traditional medical procedures fall short of these requirements [25].

Recently, neem leaves extract was loaded on chitosan nanoparticles forming nanocomposites which exhibited an inhibitory effect against pathogenic Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial strains in the bacterial biofilm [26]. We designated this study based on the severe impacts of A. sobria on Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) health and productivity and the hazards of antibiotics usage in aquaculture on fish health and, consequently, consumers' well-being. The current investigation was intended to investigate the probable therapeutic effect of chitosan neem nanocapsule (CNNC) as an alternative to antibiotics against A. sobria-induced hepato-renal dysfunction, antioxidant, and immune suppression in Nile tilapia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. CNNC preparation

The fresh neem leaves were provided from the Desert Research Center, Gizza, Egypt. The leaves were air-dried and mixed using a Moulinex mixer (Type 716, France) to obtain the powder form. For the preparation of the extract, about 10 g of the powdered neem leaves were soaked in 250 mL of doubly deionized water and sonicated for 1 h at 50 kHz and cycle 0.6 using a Hielscher UP400S sonicator prop apparatus. The extract was processed using Whatman No. 1 filter paper. Then, CNNC was prepared by the sono-chemical method [27] with some modifications. Briefly, chitosan (Sigma-Aldrich) aqueous solution (0.2% w/v) was mixed with an acetic acid solution (2% v/v) at 60 °C and stirred for 1 h. Then, about 50 mL of neem extract was added with vigorous stirring, and finally, sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution (1% w/v) was added drop by drop until a green-whitish mixture appeared. The mixture was washed in a beaker of 2 L deionized water and let to be precipitated, and then the supernatant solution was removed. The final steps were repeated three times to remove any access to secondary products from the synthesis method.

2.2. Characterization of the CNNC

The X-ray diffraction (XRD, Thermo Scientific company model of EQUINOX 1000) was used to determine the CNNC composition to be sure that the obtained CNNC was formed without any secondary chemicals from synthesis. Characterization of the CNNC morphology was performed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL company model of JEM-2100 high-resolution) and atomic force microscopy (AFM, Agilent technology company model of 5600LS). Specific surface area [Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method] and pore size [Dollimore and Heal (DH) method ] were determined using a surface area and pore size analyzer (Quanta Chrome Company model of Nova Touch 4 L). Size (Dynamic light scattering, DLS) and charge (zeta potential) were determined using a zeta seizer (Malvern Company model of Nano Sight NS500).

2.3. Bacterial strain

The A. sobria strain from dead fish was previously found by the Department of Aquatic Animal Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, and it was verified that it was harmful to O. niloticus [[28], [29], [30], [31]]. Both standard biochemical assays and the VITEK® 2 system (BioMérieux Inc., NC, USA) were used to identify the isolate. After the bacterial isolate was cultivated for 24 h at 27 °C on tryptic soy agar, one colony was selected to incubate for 24 h at that temperature in tryptic soy broth. The pellet from the cultured broth containing the isolates was extracted by centrifuging at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was then suspended in a sterile phosphate-buffered saline solution.

2.4. In-vitro antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of CNNC and chitosan against A. sobria was tested using the disc diffusion assay [32]. The bacterial isolate's overnight culture was applied on Muller Hinton agar (Difco Laboratories). Once the turbidity matched McFarland tube number 0.5 (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL), pure colonies of the bacterium were suspended in sterile saline and swabbed onto Muller Hinton agar in a loopful. Different concentrations of CNNC and chitosan were used (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mg/mL), and the sterile paper discs (6 mm in diameter) were dried at 100 °C for 2 h in a hot air oven before being applied to the inoculated agar plates. Then, the zones of inhibition were measured in mm on the plates after they had been incubated. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) assays for CNNC and chitosan were determined. The MIC was carried out [33] with some changes. Different CNNC and chitosan concentrations (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mg/mL) were added to a 96-well microtitre plate, and each concentration was added in a separate well. Then, about ten μL of each standardized broth culture (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL) were added to each well. The microtitre plate was then incubated following organism growth requirements, and any audible bacterial growth was checked. The MIC was the lowest CNNC and chitosan concentration at which there was no observable growth on the agar surface. MBC was done by sub-culturing from each well of the microplate onto a nutrient agar plate. The well containing the least concentration of the CNNC and chitosan that did not produce growth on subculture was regarded as MBC for that test strain.

2.5. Fish and rearing conditions

Four hundred and twenty cultured O. niloticus (25 ± 2.10 g) that seemed in good condition were acquired for the in-vivo test from the Fish Research Unit at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Zagazig University of Egypt. Fish were observed and acclimated for two weeks before the trial. An assessment of the fish's health was also done to ensure they were well. Ten fish were housed in glass aquariums (40 × 30 × 80 cm) with 60 L of dechlorinated tap water. The water criteria measurements, which included dissolved oxygen (6.00 ± 0.50 mg/L), pH (6.3 ± 0.6), temperature (26 ± 1.2 °C), and ammonia (0.030 ± 0.01 mg/L), were established with a controlled day to night period (12 h dark: 12 h light), following the APHA guidelines [34] to be suitable for Nile tilapia culture. A basal diet of 3% was fed to the fish. The animal usage in the research committee at Zagazig University in Egypt approved the experimental protocol (ZU-IACUC/2/F/310/2022).

2.6. Determination of CNNC therapeutic dosage

To determine the therapeutic dose of CNNC, the method of Abdel Rahman et al. [35] was applied with some modifications. About 120 fish were exposed to 12 grading levels of CNNC (0, 0.5, 1.00, 1.50, 2.00, 2.50, 3.00, 3.50, 4.00, 4.50, 5.50, and 6 mg/L) for 7 days (Table 1). Daily monitoring for the mortalities and observable signs was carried out throughout the exposure period (7 days). The safe concentration of CNNC for the therapy study was 1 mg/L.

Table 1.

Effect of the exposure to different concentrations of CNNC on mortality and clinical observations of O. niloticus for seven days.

| Conc. (mg/L) | Clinical observations |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality (N = 10) | Loss of escape reflex | Abnormal swimming | External skin lesion | |

| 0.0 | 0/10 | – | – | – |

| 0.5 | 0/10 | – | – | – |

| 1 | 0/10 | – | – | – |

| 1.5 | 1/10 | – | – | – |

| 2 | 1/10 | – | – | – |

| 2.5 | 2/10 | – | – | – |

| 3 | 2/10 | – | – | – |

| 3.5 | 3/10 | + | + | + |

| 4 | 3/10 | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 4.5 | 3/10 | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 5 | 4/10 | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 5.5 | 4/10 | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 6 | 4/10 | +++ | +++ | +++ |

(−) no abnormal observations; (+) mild abnormal observations; (++) moderate abnormal observations (+++); severe abnormal observations.

2.7. Experimental setup

The lethal dose 50 (LD50) of A. sobria was calculated [29] as follow; a total of 100 fish were distributed into five groups in two replication (20 fish/group; 10 fish/replicate). Fish were fasted for 24 h before the experimental infection. The intraperitoneal (IP) injection of the first to the fourth groups was performed using 0.5 mL of dosages of A. sobria bacterial suspension (106, 107, 108, and 109 CFU/fish). About 0.5 mL of sterile saline was IP injected into the fifth group. The mortality of the infected fish was tracked for four days following injection. The LD50 was computed as 2 × 107 CFU/mL using the Probit Analysis Program version 1.5.

The challenge test was employed using a sub-lethal dosage of 1 × 107 CFU/mL, and the outcomes were verified using a drop plate test [36]. A total of 200 fish were randomly divided into four groups, with 50 fish per group in five repetitions over seven days. The first (control) and second (CNNC) groups received treatments of 0 and 1 mg/L CNNC in water without being challenged. The third and fourth groups (A. sobria and A. sobria + CNNC, respectively) received 0 and 1 mg/L CNNC treatments and were IP challenged with 0.2 mL of A. sobria (1 × 107 CFU/mL). Throughout the seven-day study, the clinical symptoms and post-mortem findings were noted. The fish survival rate (%) was determined using Eq. (1).

| (1) |

2.8. Blood sampling

Fish were anesthetized with 100 mg/L benzocaine solution [37] at the termination of the experiment (7 days). The caudal vessels were used to collect blood samples (15 fish/group), which were then centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min to separate the serum at 3000 rpm, and then kept at 20 °C pending the immunological and biochemical testing.

2.9. Serum antioxidant/oxidant assays

According to the Ohkawa et al. [38] approach, the malondialdehyde (MDA) level was determined using the thiobarbituric acid assay. The thiobarbituric acid reactive compounds were detected at 535 nm, and the level of MDA was then determined. According to the technique described by Aebi [39], catalase (CAT) activity was measured, and the enzymatic reaction mixture used in this assay included potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and homogenate supernatant. Using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer, the molar attenuation coefficient of H2O2 was investigated at 240 nm.

The CAT amount degrading H2O2 (1 μmol)/minute/milligram of hippocampal tissue protein (U/mg protein) was used to measure CAT activity. Reduced glutathione content (GSH) was measured calorimetrically following the method of Beutler [40]. A spectrophotometric test at 412 nm of the yellow derivative produced by the reaction of the supernatant with 5-5′ dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid and protein precipitation by meta-phosphoric acid are both used in this method. Glutathione activity was assayed by monitoring glutathione utilization by H2O2.

2.10. Hepato-renal-functions-related assays

The aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were estimated by Spinreact kits (Esteve De Bas, Girona, Spain) at 540 nm following the Burits and Ashwood [41] and Reitman and Frankel [42] protocols. Creatinine was estimated by Spinreact kits (Esteve De Bas, Girona, Spain) following the Fossati et al. [43] approach.

2.11. Immune-related assays

A colorimetric test was followed to evaluate the nitric oxide (NO) level following Montgomery and Dymock [44] technique by detecting nitrite (NO2-) using Griess reagent and converting nitrate (NO3-) to NO2- using vanadium chloride as a reducing agent. To remove undesirable proteins from the sample, 1 mL of 100% alcohol and 0.5 mL of serum sample were combined, and the mixture was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min. Next, 0.5 mL of the produced sample was added with 0.5 mL of the Griess reagent and 0.5 mL of vanadium chloride (0.8%) in 1 M HCl. The absorbance was measured at 540 nm against deionized water following thorough mixing and incubation for 30 min At 37 °C. To create a standard curve, various sodium NO2-concentrations were employed.

The serum lysozyme (LYZ) activity was assessed using spectrophotometry [45] based on the lysis of Micrococcus lysodeikticus (Sigma Co., USA) with some changes. The serum and M. lysodeikticus suspension (0.2 mg/mL in 0.05 M PBS, pH 6.2) were combined at 25 °C for 5 min. The optical density was evaluated at 540 nm for 5 min at 1-min intervals. To determine the serum LYZ level, a calibration curve was done using various concentrations of lyophilized chicken egg-white lysozyme (Sigma Co., USA). Serum complement 3 (C3) was measured using MyBioSource Co. ELISA kits (Cat. No. MBS005953), and this included measuring the rise in turbidity after the immune system's reaction to the anti-C3 antibody at 340 nm.

2.12. Data analysis

To assess the treatment impact of CNNC against A. sobria, the data were first submitted to a normality test (the Kolmogorov-Smirnov) and then subjected to a two-way ANOVA using the SPSS program (version 20; Richmond, VA, USA). Duncan's post hoc test was performed to evaluate mean differences using the 5% probability level. The findings were shown as means ± standard error. The LD50 of A. sobria was determined using the Probit Analysis Program, version 1.5, of the US Environmental Protection Agency.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the CNNC

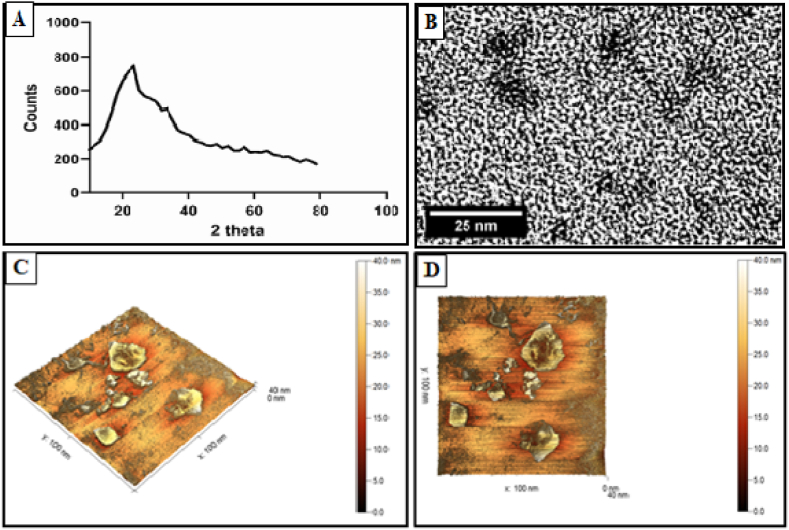

As illustrated in Fig. 1A, the XRD pattern confirmed the amorphous nature of CNNC. TEM image showed the sub-spherical shape of CNNC without any aggregation or agglomeration (Fig. 1B). AFM images (3D and 2D) illustrated the triangle shape to the sub-spherical nature of CNNC with different particle size distributions (Fig. 1C and D).

Fig. 1.

The characterization patterns of CNNC: (A) XRD, (B) TEM, and (C and D) AFM 3 D and 2 D.

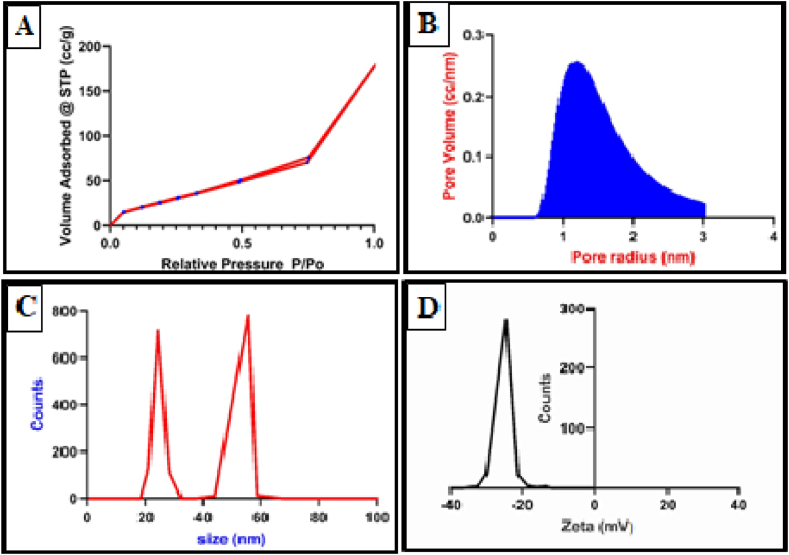

The surface area estimated with the BET approach clearly showed how highly valued CNNC was. The pore volume established by the DH technique was 1.2 cc/nm, and the BET surface area value was 74.2 m2/g. Fig. 2A illustrates the isotherm of CNNC, which have type II isotherm. Fig. 2B reveals the microporous using the DH method. DLS exhibited that the particle size and distribution were 24 and 55 nm (Fig. 2C). Zeta potential value was −30 mV (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

The characterization patterns of CNNC: (A) Isotherm, (B) pore size and pore volume according to the DH method, (C) DLS, and (D) Zeta potential.

3.2. In-vitro antibacterial activity

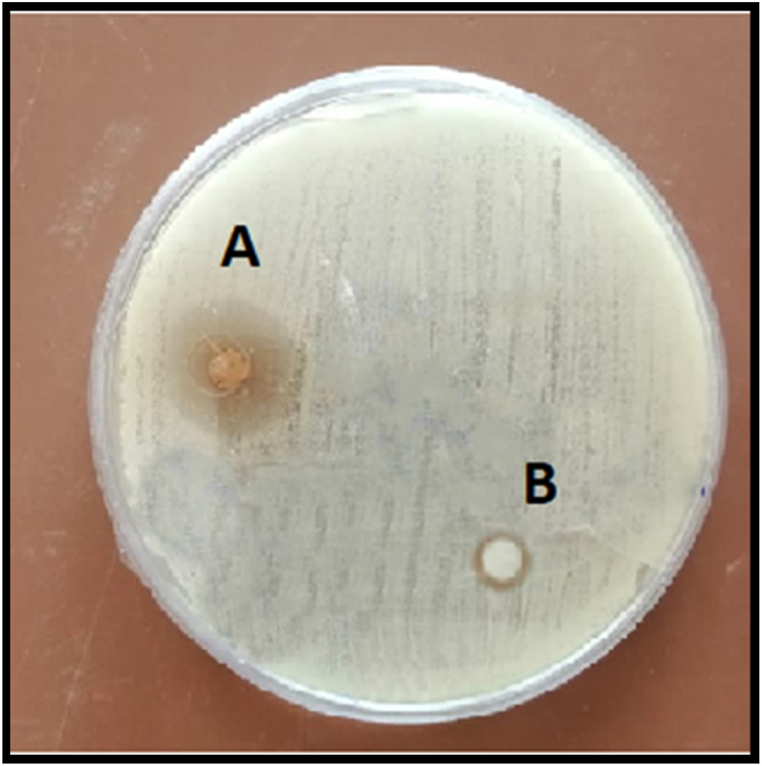

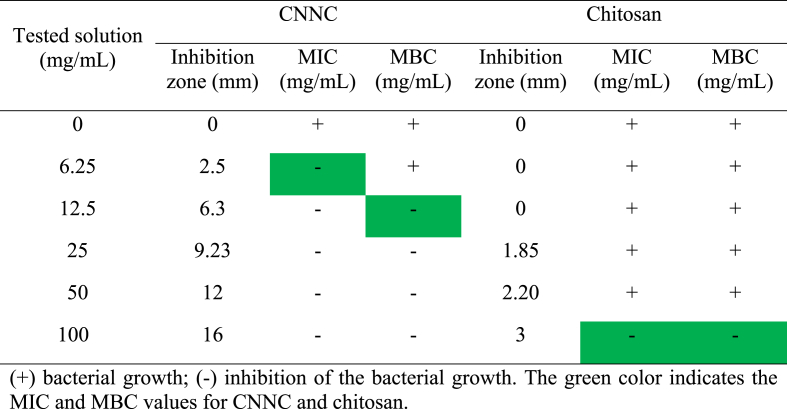

CNNC and chitosan showed antibacterial activity against A. sobria with different inhibition zone diameters depending on the concentrations. At the concentrations of 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 mg/mL, the inhibition zones of CNNC were 0, 2.5, 6.3, 9.23, 12, and 16 mm (Fig. 3 A) for CNNC and were 0, 0, 0, 1.85, 2.20, and 3 mm (Fig. 3B) for chitosan, respectively. The MIC of CNNC and chitosan against A. sobria were 6.25 and 100 mg/mL, respectively. Meanwhile, the MBC of CNNC and chitosan were 12.5 and 100 mg/mL, respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition zones (mm) against A. sobria at a concentration of 100 mg/mL of CNNC (A) and chitosan (B).

Table 2.

The inhibition zone diameter (mm), MIC, and MBC of CNNC and chitosan against A. sobria.

3.3. Clinical signs, behaviors, and survivability

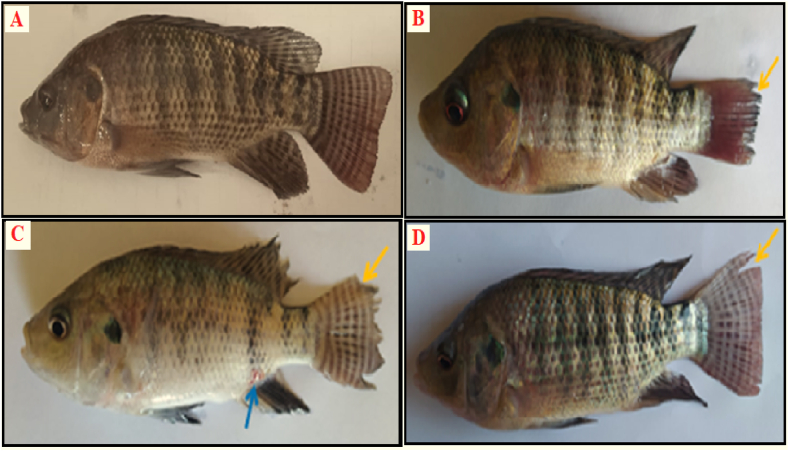

The fish of the control and CNNC groups exhibited the highest survivability (100%). They showed no abnormal behaviors (Table 3) or symptoms (Fig. 4A). The survival rate of A. sobria group fish was low (60%). They also had fin rot, hemorrhages on various body parts, and skin ulcerations (Fig. 4B and C) with internal organs congestion. Likewise, the CNNC + A. sobria group showed increased survivability (85%) and alleviation of the previous disease signs, with only slight fin rot of the tail fin (Fig. 4D).

Table 3.

Effect of A. sobria infection and/or CNNC as water treatment on behavioral responses and survival rate (%) of O. niloticus for seven days.

| Parameters | Control | CNNC | A. sobria | CNNC + A. sobria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surfacing | – | – | +++ | + |

| Abnormal swimming | – | – | +++ | + |

| Loss of escape reflex | – | – | +++ | + |

| Survival rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 60 | 85 |

The score of symptoms was recorded as (−) no, (+) mild, (++) moderate, and (+++) severe.

Fig. 4.

Effect of CNNC as water exposure on clinical observations of experimentally infected O. niloticus with A. sobria for seven days. (A) Fish of the control group or CNNC group demonstrating normal appearance. (B and C) Fish of the A. sobria group demonstrating skin ulcerations (blue arrows), body hemorrhages, and fin rot (yellow arrows). (D) Fish of the CNNC + A. sobria group demonstrating slight fin rot (yellow arrow).

3.4. Antioxidant/oxidant parameters

In comparison with the non-infected groups, the antioxidant enzymes (CAT and GSH) were considerably lower (P < 0.05), and the MDA level was considerably higher (P < 0.05) in the infected groups. Regarding the impact of CNNC water treatment, CNNC treatment (1 mg/L) increased the GSH level and decreased the MDA level (P < 0.05) but had no impact (P > 0.05) on the CAT level.

Concerning the interaction between the A. sobria infection and CNNC water application, the non-infected group and treated with 1 mg/L CNNC showed a significantly (P < 0.05) lower level of MDA and higher level of CAT and GSH (P < 0.05) than the non-infected one and treated with 0 mg/L CNNC. However, the infected group treated with 0 mg/L CNNC had a substantial decline (P < 0.05) in the levels of CAT and GSH and a significant increase (P < 0.05) in the level of MDA. When the infected group received 1 mg/L CNNC treatment, these parameters were dramatically altered and improved (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of A. sobria infection and/or CNNC as water treatment on the oxidant/antioxidant biomarkers of O. niloticus for seven days.

| A. sobria infection | CNNC (mg/L) | MDA (nmol/mL) | CAT (ng/mL) | GSH (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of A. sobria infection | ||||

| Non-Infected | 1.42 ± 1.96b | 154.22 ± 9.94a | 162.46 ± 5.63a | |

| Infected | 12.85 ± 3.12a | 30.80 ± 2.85b | 33.10 ± 1.66b | |

| Effect of CNNC as water treatment | ||||

| 0 | 11.01 ± 1.96a | 86.29 ± 7.58 | 72.46 ± 5.25b | |

| 1 | 3.26 ± 1.32b | 98.73 ± 9.94 | 123.09 ± 6.85a | |

| Interaction | ||||

| Non-infected | 0 | 1.14 ± 0.04c | 152.15 ± 3.65a | 133.90 ± 3.04b |

| 1 | 1.71 ± 0.01c | 156.30 ± 2.35a | 191.02 ± 2.96a | |

| Infected | 0 | 20.89 ± 0.32a | 20.43 ± 0.44c | 11.03 ± 0.49d |

| 1 |

4.82 ± 0.17b |

41.17 ± 1.85b |

55.16 ± 0.93c |

|

| Two-way ANOVA | P-value | |||

| A. sobria infection | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| CNNC water treatment | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.01 | |

| Interaction | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

MDA, malondialdehyde; CAT, catalase; GSH, reduced glutathione. The values were expressed as mean ± SE (N = 15/group). Values in the same column that did not share the same superscripts differed significantly (P < 0.05; two-way ANOVA).

3.5. Hepato-renal functions-related parameters

In comparison with the non-infected groups, the levels of the hepato-renal function markers (AST, ALT, and creatinine) were substantially higher in A. sobria-infected groups (P < 0.05) than the control one. Regarding the CNNC water treatment impact, the liver function indicators (AST and ALT) were considerably decreased (P < 0.05) by treatment with 1 mg/L CNNC in comparison to the non-treated groups, with no significant influence (P > 0.05) on creatinine level.

Concerning the interaction between A. sobria infection and CNNC water application, it was noticed that the hepato-renal function indicators were elevated significantly (P < 0.05) in the infected group, which was treated with 0 mg/L CNNC followed by the infected one, which was treated with 1 mg/L CNNC compared to other groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of A. sobria infection and/or CNNC as water treatment on the hepato-renal biomarkers of O. niloticus for seven days.

| A. sobria infection | CNNC (mg/L) | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) | Creatinine (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of A. sobria infection | ||||

| Non-infected | 84.87 ± 2.01b | 16.65 ± 3.15b | 0.25 ± 0.04b | |

| Infected | 113.72 ± 4.25a | 36.68 ± 6.85a | 0.36 ± 0.09a | |

| Effect of CNNC as water treatment | ||||

| 0 | 104.07 ± 2.01a | 32.40 ± 3.15a | 0.31 ± 0.04 | |

| 1 | 94.52 ± 2.11b | 20.93 ± 2.11b | 0.30 ± 0.02 | |

| Interaction | ||||

| Non-infected | 0 | 85.74 ± 0.98c | 15.81 ± 1.12c | 0.23 ± 0.01c |

| 1 | 84.00 ± 2.01c | 17.50 ± 1.50c | 0.27 ± 0.02c | |

| Infected | 0 | 122.40 ± 2.50a | 49.00 ± 2.12a | 0.40 ± 0.20a |

| 1 |

105.05 ± 3.21b |

24.37 ± 1.81b |

0.33 ± 0.11b |

|

| Two-way ANOVA | P-value | |||

| A. sobria infection | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.01 | |

| CNNC water treatment | 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.82 | |

| Interaction | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase. The values were expressed as mean ± SE (N = 15/group). Values in the same column that did not share the same superscripts differed significantly (P < 0.05; Two-way ANOVA).

3.6. Immune functions parameters

Comparable to the non-infected groups, the immunological parameters (NO, LYZ, and C3) were substantially lowered (P < 0.05) in the infected groups. These immunological indices were considerably enhanced (P < 0.05) by treatment with 1 mg/L CNNC. In terms of the relationship between the A. sobria infection and CNNC water treatment, it was noticed that the immunological parameters were considerably improved (P < 0.05) in the non-infected groups treated with 1 mg/L CNNC, followed by the non-infected group treated with 0 mg/L CNNC. In contrast, these immunological markers were significantly reduced (P < 0.05) in the infected group treated with 0 mg/L CNNC. When the infected group received 1 mg/L CNNC treatment, these parameters dramatically improved (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effect of A. sobria infection and/or CNNC as water treatment on the immunological biomarkers of O. niloticus for seven days.

| A. sobria infection | CNNC (mg/L) | NO (ng/mL) | LYZ (ng/mL) | C3 (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of A. sobria infection | ||||

| Non-infected | 406.11 ± 15.12a | 5.88 ± 1.12a | 11.67 ± 2.25a | |

| Infected | 177.92 ± 6.43b | 1.04 ± 0.11b | 3.34 ± 0.45b | |

| Effect of CNNC as water treatment | ||||

| 0 | 269.41 ± 4.22b | 2.41 ± 0.11b | 5.51 ± 0.45b | |

| 1 | 314.62 ± 6.43a | 4.51 ± 0.24a | 9.49 ± 2.15a | |

| Interaction | ||||

| Non-infected | 0 | 371.23 ± 10.13b | 4.60 ± 0.20b | 9.23 ± 0.49b |

| 1 | 441.00 ± 9.10a | 7.16 ± 0.10a | 14.11 ± 2.00a | |

| Infected | 0 | 167.60 ± 2.47d | 0.23 ± 0.02d | 1.80 ± 0.10d |

| 1 |

188.25 ± 2.01c |

1.86 ± 0.10c |

4.88 ± 0.02c |

|

| Two-way ANOVA | P-value | |||

| A. sobria infection | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.001 | |

| CNNC water treatment | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Interaction | 0.03 | 0.001 | 0.01 | |

NO, nitric oxide; LYZ, lysozyme; C3, complement 3. The values were expressed as mean ± SE (N = 15/group). Values in the same column that did not share the same superscripts differed significantly (P < 0.05; Two-way ANOVA).

4. Discussion

New alternatives to antibiotic therapy should be established to address the problem of antibiotic resistance in aquaculture. This study proposed a novel antibacterial agent for future application in treating bacterial fish pathogens (A. sobria) using the nanotechnology procedure. Synthesis and characterization of CNNC were studied. Nano-encapsulation is a newly developed method used extensively in the pharmaceutical, chemical, cosmetics, and food processing industries [46]. A similar preparation method to the aqueous extract of Ocimum basilicum using the chitosan nanocapsule has been investigated [28]. The CNNC was characterized using several techniques [47], which confirmed the synthesis process of the nano form. The XRD pattern in this study confirmed the amorphous nature of CNNC with a good coating of neem extract by the chitosan nanocapsule. AFM and TEM techniques confirmed the topography and particle shape of CNNC, which revealed the sub-spherical shape without any aggregation or agglomeration of CNNC. In addition, the BET surface area (74.2 m2/g) and pore volume (1.2 cc/nm) for the CNNC indicate improved bioactivity as a result of improving chemical activity. Triangle-shaped particles with two distinct dimensions may be responsible for CNNC's 24 and 55 nm DLS patterns. The high solubility of CNNC in an aqueous solution and negative charge resulting from the effective coating of neem extract, where chitosan has a positive charge, is explained by the high zeta potential value (−30 mV).

Herein, CNNC had an in-vitro antibacterial activity against A. sobria. The antibacterial activity of chitosan-neem nanocomposites against Escherichia coli and S. aureus had been investigated in a previous report [48]. The antibacterial activity of the CNNC against A. sobria could be related to the synergistic effect of both neem leave extract and chitosan (both are antibacterial agents) [[48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54]]. Moreover, the phytochemical constituents of the neem leaves, such as steroids, glycosides, alkaloids, triterpenoids, saponins, and triterpenes, have antibacterial properties [55]. These phytoconstituents are considered the antibacterial components against pathogens [56]. Also, they have a variety of effects on the microbial cell through different mechanisms, including alterations in the structure and operation of cell membranes [57], interfering with the metabolism of intermediaries [58], disruption of DNA/RNA function and synthesis [59], and quorum sensing, which prevents normal cell communication [60]. Additionally, cytoplasmic components' induction of coagulation [61]. In addition, chitosan interacts with surface molecules and blocks mRNA by attaching to bacterial DNA [62]. According to Raafat et al. [63] and Ganan et al. [64], the amine groups (NH3 +) of glucosamine in chitosan, which may be a crucial component in its ability to interact with a negatively charged surface element of many microorganisms and cause extensive surface alterations that result in the leakage of intracellular substances and cell death, are what give chitosan its antibacterial potential.

The A. sobria-infected fish suffered hemorrhagic skin, fin rot, decreased swimming behavior, and lowered survivability (60%). Similar outcomes were recorded in previous investigations [[65], [66], [67]]. According to Janda and Abbott [68], these repercussions may be caused by the circulation of bacteria in the blood and some virulence factors, such as hydrolytic enzymes, hemolytic toxins, and cytotoxic enterotoxins. On the other hand, therapy with 1 mg/L CNNC for the A. sobria-infected group restored the prior clinical symptoms and improved fish survivability (85%). These outcomes may be explained by CNNC's antibacterial characteristics, demonstrated in this work by the in-vitro assay.

An imbalance between antioxidant enzyme activity and excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production causes oxidative stress [[69], [70], [71]]. Fish are protected from oxidative stress by an enzymatic antioxidant system [72]. Oxidative stress resulted in elevated lipid peroxidation levels, which is indicated by the increase in the level of MDA [70,73,74]. In this regard, the A. sobria-infected group in the current study had lower levels of CAT and GSH but greater levels of MDA. These consequences result from increasing the cell wall lipid peroxidation (MDA) and ROS production by the virulence factors of the bacteria, which are blamed on a state of oxidative stress [75].

Surprisingly, treatment of the A. sobria-infected group with 1 mg/L CNNC modulates these variables. This could be attributed to the prevention of disease progression. Moreover, the synergistic effect of both neem leaves extract and chitosan. The antioxidant properties of neem leaves extract could be attributed to its phytochemical constituents of flavonoids and phenolics, which act as antioxidants to defend against free radicals that can harm tissues and cells [55,76]. Additionally, the chelating activity of chitosan and the free radical scavenging of its hydroxyl function group, which was accomplished by donating two electrons, might be responsible for its antioxidant characteristics [77].

Increased hepato-renal function indicators in the serum indicate liver and kidney dysfunctions [[78], [79], [80]]. A. sobria-infected group showed disruption in the hepato-renal functions (higher AST, ALT, and creatinine) comparable to the control group. A. sobria may produce toxic compounds that could injure hepatocytes and renal cells, increasing these indicators [81]. Modulation of the hepato-renal function indicators of the infected fish was noticed by treatment with 1 mg/L CNNC. These results could be attributed to the antioxidant activity of CNNC, which was evident in this study by decreasing the MDA and increasing the antioxidant enzymes, which help to maintain the tissue health and integrity, accordingly maintaining their functions.

The immune function biomarkers were investigated in the current study. The potent elements of fish humoral non-specific defensive systems include NO [82]. Bacteriolytic enzymes called LYZ are thought to be a sign of a generalized immune response to microbial invasion [83]. The complement system is a group of proteins communicating with the innate and adaptive immune systems in fish and other vertebrates. In the humeral component of innate immunity, the complement system is a noticeable and significant player [84]. Immune function markers (NO, LYZ, and C3) decreased in the A. sobria-infected fish; this outcome may be attributed to the bacteria's pathogenicity. According to earlier studies [81], A. sobria's virulence factors enable the bacteria to damage host tissues and impair host defense mechanisms.

On the contrary, treatment of the A. sobria-infected group with 1 mg/L CNNC enhanced the immunological parameters. These results could be attributed to the combined effect of neem leaves extract and chitosan (both had immune-enhancing properties). A previous study reported that neem leaves extract enhanced the immune system and increased the survivability of Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) fingerlings challenged with Vibrio harveyi infection [85]. Moreover, dietary chitosan was reported to increase the non-specific immune response of the olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) and improve the water quality [86]. The immuno-stimulant effect of neem extract could be attributed to its constituent, β-sitosterol, which was suggested to have a role in strengthening the immune system [55]. The immune-stimulant properties of chitosan through increasing immunoglobulin M and LYZ levels were previously reported in O. niloticus [87,88].

5. Conclusion

According to the outcomes of the disc diffusion and MIC tests, CNNC exhibits a stronger antibacterial activity against A. sobria. CNNC therapy by 1 mg/L as a water additive can alleviate the health disorders, hepato-renal disruption, and oxidant-immune dysfunction caused by the A. sobria infection. CNNC can be used as a potential alternative to antibiotics in aquaculture for controlling the A. sobria bacterial infection, hence maximizing the aquaculture industry. Future research is required to determine how CNNC affects fish health status at the molecular and histological levels. Also, more research should be designated for testing the antibacterial activity of CNNC against a wide range of fish pathogens.

Author contribution statement

Rowida E. Ibrahim, Gehad E. Elshopakey, Abdelwahab A. Abdelwarith, Elsayed M. Younis, Sameh H. Ismail, Amany I. Ahmed, Mahmoud M. El-Saber, Ahmed E. Abdelhamid, Simon J. Davies, Abdelhakeem El-Murr, and Afaf N. Abdel Rahman: Conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. Rowida E. Ibrahim and Afaf N. Abdel Rahman: Wrote the paper. All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Researches Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R700), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors thank the Aquatic Animal Medicine Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, for their kind help during the experimental procedures..

Contributor Information

Rowida E. Ibrahim, Email: rowidakamhawey@yahoo.com.

Afaf N. Abdel Rahman, Email: afne56@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Khan M.A., Hossain M.E., Rahman M.T., Dey M.M. COVID-19's effects and adaptation strategies in fisheries and aquaculture sector: an empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Aquaculture. 2023;562 doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nesslage G., Pauly D. Estuarine Ecology; 2022. Estuarine Fisheries and Aquaculture; p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(FAO) SOFIA; Rome, Italy: 2022. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture; p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guardone L., Tinacci L., Armani A., Trevisani M. Residues of veterinary drugs in fish and fish products: an analysis of RASFF data over the last 20 years. Food Control. 2022;135 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yilmaz S., Yilmaz E., Dawood M.A.O., Ringø E., Ahmadifar E., Abdel-Latif H.M.R. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics used to control vibriosis in fish: a review. Aquaculture. 2022;547 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel Rahman A.N., Van Doan H., Elsheshtawy H.M., Dawood A., Salem S.M.R., Sheraiba N.I., Masoud S.R., Abdelnaeim N.S., Khamis T., Alkafafy M., Mahboub H.H. Dietary Salvia officinalis leaves enhances antioxidant immune-capacity, resistance to Aeromonas sobria challenge, and growth of Cyprinus carpio. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022;127:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2022.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reda R.M., Maricchiolo G., Quero G.M., Basili M., Aarestrup F.M., Pansera L., Mirto S., Abd El‐Fattah A.H., Alagawany M., Abdel Rahman A.N. Rice protein concentrate as a fish meal substitute in Oreochromis niloticus: effects on immune response, intestinal cytokines, Aeromonas veronii resistance, and gut microbiota composition. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022;126:237–250. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2022.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Younis N.A., Elgendy M.Y., El-Samannoudy S.I., Abdelsalam M., Attia M.M. Cyathocotylidae spp and motile aeromonads co-infections in farmed Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) causing mass mortality. Microb. Pathog. 2023;174 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caruso G. Antibiotic resistance in fish farming environments: a global concern. J FisheriesSciences.com. 2016;10:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaturvedi P., Shukla P., Giri B.S., Chowdhary P., Chandra R., Gupta P., Pandey A. Prevalence and hazardous impact of pharmaceutical and personal care products and antibiotics in environment: a review on emerging contaminants. Environ. Res. 2021;194 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redwan Haque A., Sarker M., Das R., Azad M.A.K., Hasan M.M. A review on antibiotic residue in foodstuffs from animal source: global health risk and alternatives. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Tawwab M., Monier M.N., Abdelrhman A.M., Dawood M.A.O. Effect of dietary multi-stimulants blend supplementation on performance, digestive enzymes, and antioxidants biomarkers of common carp, Cyprinus carpio L. and its resistance to ammonia toxicity. Aquaculture. 2020;528 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudecová P., Koščová J., Hajdučková V. Phytobiotics and their antibacterial activity against major fish pathogens. A review. Folia Vet. 2023;67:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ndomou S.C.H., Mube H.K. The use of plants as phytobiotics: a new challenge. Intech. 2023 doi: 10.5772/intechopen. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibrahim R.E., Ghamry H.I., Althobaiti S.A., Almalki D.A., Shakweer M.S., Hassan M.A., Khamis T., Abdel-Ghany H.M., Ahmed S.A. Moringa oleifera and Azadirachta indica leaves enriched diets mitigate chronic oxyfluorfen toxicity induced immunosuppression through disruption of pro/anti-inflammatory gene pathways, alteration of antioxidant gene expression, and histopathological Alteration in Oreochromis niloticus. Fishes. 2022;8:15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur Y., Dhawan A., Naveenkumar B., Tyagi A., Shanthanagouda A. Immunostimulatory and antifertilityeffects of neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf extract on common carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus) Indian J. Anim. Res. 2020;54:196–201. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rathod V.S., Pawar P.S., Gorde A.B. A review on pharmacological importance of azadirachta indica. World J. Pharmaceut. Res. 2022;11:412–419. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wylie M.R., Merrell D.S. The antimicrobial potential of the neem tree Azadirachta indica. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.891535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devi N.P., Das S., Sanjukta R., Singh S.G. A comparative study on antibacterial activity of integumentary extract of selected freshwater fish Species and Neem extracts against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2019;7:1352–1355. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavitha M., Raja M., Kamaraj C., Karthik R., Balasubramaniam V., Balasubramani G., Perumal P. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Azadirachta indica (leaves) against fish pathogenic bacteria isolated from naturally infected Dawkinsia filamentosa (Blackspot barb) Med. Aromatic Plants. 2017;6:294. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vonnie J.M., Ting B.J., Rovina K., Aqilah N.M.N., Yin K.W., Huda N. Natural and engineered nanomaterials for the identification of heavy metal ions—a review. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:2665. doi: 10.3390/nano12152665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Sayed A., Kamel M. Advanced applications of nanotechnology in veterinary medicine. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020;27:19073–19086. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3913-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalaf E.M., Abood N.A., Atta R.Z., Ramírez-Coronel A.A., Alazragi R., Parra R.M.R., Abed O.H., Abosaooda M., Jalil A.T., Mustafa Y.F. Recent progressions in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications of chitosan nanoparticles: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;231 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasrollahzadeh M., Sajjadi M., Iravani S., Varma R.S. Starch, cellulose, pectin, gum, alginate, chitin and chitosan derived (nano) materials for sustainable water treatment: a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;251 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonifacio B.V., da Silva P.B., Ramos M.A.d.S., Negri K.M.S., Bauab T.M., Chorilli M. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems and herbal medicines: a review. Int. J. Nano-medicine. 2014:1–15. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S52634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paunova-Krasteva T., Hemdan B.A., Dimitrova P.D., Damyanova T., El-Feky A.M., Elbatanony M.M., Stoitsova S., El-Liethy M.A., El-Taweel G.E., El Nahrawy A.M. Hybrid chitosan/CaO-based nanocomposites doped with plant extracts from Azadirachta indica and Melia azedarach: evaluation of antibacterial and antibiofilm activities. BioNanoScience. 2023;13:88–102. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elabd H., Mahboub H.H., Salem S.M., Abdelwahab A.M., Alwutayd K.M., Shaalan M., Ismail S.H., Abdelfattah A.M., Khalid A., Mansour A.T. Nano-curcumin/chitosan modulates growth, biochemical, immune, and antioxidative profiles, and the expression of related genes in nile tilapia. Oreochromis niloticus. 2023;8:333. Fishes. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdel Rahman A.N., Elshopakey G.E., Behairy A., Altohamy D.E., Ahmed A.I., Farroh K.Y., Alkafafy M., Shahin S.A., Ibrahim R.E. Chitosan-Ocimum basilicum nanocomposite as a dietary additive in Oreochromis niloticus: effects on immune-antioxidant response, head kidney gene expression, intestinal architecture, and growth. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022;128:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2022.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ibrahim R.E., Amer S.A., Farroh K.Y., Al-Gabri N.A., Ahmed A.I., El-Araby D.A., Ahmed S.A. The effects of chitosan-vitamin C nanocomposite supplementation on the growth performance, antioxidant status, immune response, and disease resistance of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fingerlings. Aquaculture. 2021;534 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed S.A., Ibrahim R.E., Farroh K.Y., Moustafa A.A., Al-Gabri N.A., Alkafafy M., Amer S.A. Chitosan vitamin E nanocomposite ameliorates the growth, redox, and immune status of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) reared under different stocking densities. Aquaculture. 2021;541 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim R.E., Ahmed S.A., Amer S.A., Al-Gabri N.A., Ahmed A.I., Abdel-Warith A.-W.A., Younis E.-S.M., Metwally A.E. Influence of vitamin C feed supplementation on the growth, antioxidant activity, immune status, tissue histomorphology, and disease resistance in Nile tilapia. Oreochromis niloticus, Aquac Rep. 2020;18 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu C., Wang L., Xu H., Wang S., Gao S., Ji X., Xu Q., Lan W. “One pot” green synthesis and the antibacterial activity of g-C3N4/Ag nanocomposites. Mater. Lett. 2016;164:567–570. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perumal S., Pillai S., Cai L.W., Mahmud R., Ramanathan S.J. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration of Euphorbia hirta (L.) extracts by tetrazolium microplate assay. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;5:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 34.APHA (American Public Health Association) 21th ed. American Water Works Association, Water Pollution Control Federation; New York: 2005. Standard Methods for Examination of Water and Wastewater; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdel Rahman A.N., Ismail S.H., Fouda M.M., Abdelwarith A.A., Younis E.M., Khalil S.S., El-Saber M.M., Abdelhamid A.E., Davies S.J., Ibrahim R.E. Impact of Streptococcus agalactiae challenge on mmune response, antioxidant status and hepatorenal indices of Nile tilapia: the palliative role of chitosan white poplar nanocapsule. Fishes. 2023;8:199. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zetterberg C., Öfverholm T. Carpal tunnel syndrome and other wrist/hand symptoms and signs in male and female car assembly workers. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 1999;23:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neiffer D.L., Stamper M.A. Fish sedation, anesthesia, analgesia, and euthanasia: considerations, methods, and types of drugs. ILAR J. 2009;50:343–360. doi: 10.1093/ilar.50.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aebi H. Methods in Enzymology. Elsevier; 1984. Catalase in vitro; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beutler E., Duron O., Kelly B.M. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1963;61:882–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burtis C.A., Ashwood E.R. Amer Assn for Clinical Chemistry; 1994. Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reitman S., Frankel S. A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1957;28:56–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/28.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fossati P., Prencipe L., Berti G. Enzymic creatinine assay: a new colorimetric method based on hydrogen peroxide measurement. Clin. Chem. 1983;29:1494–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montgomery H., Dymock J. Determination of nitrite in water, Royal soc chemistry thomas graham house, science park, milton rd, cambridge Cb4 0wf. J. Med. Lab. Technol. 1961;22:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ellis A.E. Lysozyme assays. Tech. Fish. Immunol. 1990;1:101–103. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramachandran T., Rajendrakumar K., Rajendran R. Antimicrobial textiles-an overview, IE (I) J. Toxins. 2004;84:42–47. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Gethami W., Alhashmialameer D., Al-Qasmi N., Ismail S.H., Sadek A.H. Design of a novel nanosensors based on green synthesized CoFe2O4/Ca-alginate nanocomposite-coated QCM for rapid detection of Pb (II) ions. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:3620. doi: 10.3390/nano12203620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rajendran R., Radhai R., Balakumar C., Ahamed H.A.M., Vigneswaran C., Vaideki K. Synthesis and characterization of neem chitosan nanocomposites for development of antimicrobial cotton textiles. J. Eng. Fiber Fabr. 2012;7 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qi L., Xu Z., Jiang X., Hu C., Zou X. Preparation and antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Res. 2004;339:2693–2700. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandrasekaran M., Kim K.D., Chun S.C. Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles: a review. Processes. 2020;8:1173. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung Y.-C., Su Y.P., Chen C.-C., Jia G., Wang H.L., Wu J.G., Lin J.G. Relationship between antibacterial activity of chitosan and surface characteristics of cell wall. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2004;25:932–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohammed H.A., Al Fadhil A.O. Antibacterial activity of Azadirachta indica (Neem) leaf extract against bacterial pathogens in Sudan. Afr. J. Med. Sci. 2017;3:246–2512. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Francine U., Jeannette U., Pierre R.J. Assessment of antibacterial activity of neem plant (Azadirachta indica) on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2015;3:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Subapriya R., Nagini S. Medicinal properties of neem leaves: a review. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:149–156. doi: 10.2174/1568011053174828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pandey G., Verma K., Singh M. Evaluation of phytochemical, antibacterial and free radical scavenging properties of Azadirachta indica (neem) leaves. Int. J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2014;6:444–447. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hafiza R. Peptides antibiotics. Lancet. 2000;349:418–422. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chitemerere T.A., Mukanganyama S. Evaluation of cell membrane integrity as a potential antimicrobial target for plant products. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2014;14:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anandhi D., Srinivasan P., Kumar G.P., Jagatheesh S. DNA fragmentation induced by the glycosides and flavonoids from C. coriaria. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014;3:666–673. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anand U., Jacobo-Herrera N., Altemimi A., Lakhssassi N. A comprehensive review on medicinal plants as antimicrobial therapeutics: potential avenues of biocompatible drug discovery. Metabolites. 2019;9:258. doi: 10.3390/metabo9110258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radulovic N., Blagojevic P., Stojanovic-Radic Z., Stojanovic N. Antimicrobial plant metabolites: structural diversity and mechanism of action. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:932–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.D Mogosanu G., M Grumezescu A., Huang K.-S., E Bejenaru L., Bejenaru C. Prevention of microbial communities: novel approaches based natural products. Curr. Pharmaceut. Biotechnol. 2015;16:94–111. doi: 10.2174/138920101602150112145916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goy R.C., Britto D.d., Assis O.B. A review of the antimicrobial activity of chitosan. Polímeros. 2009;19:241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raafat D., Von Bargen K., Haas A., Sahl H.-G. Insights into the mode of action of chitosan as an antibacterial compound. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:3764–3773. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00453-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ganan M., Carrascosa A., Martinez-Rodriguez A. Antimicrobial activity of chitosan against Campylobacter spp. and other microorganisms and its mechanism of action. J. Food Protect. 2009;72:1735–1738. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-72.8.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soliman M.K., Nageeb H.M., Aboyadak I.M., Ali N.G. Treatment of MAS caused by Aeromonas sobria in European seabass, Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2022;26:535–556. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Selim K.M., El-Sayed H.M., El-Hady M.A., Reda R.M. In vitro evaluation of the probiotic candidates isolated from the gut of Clarias gariepinus with special reference to the in vivo assessment of live and heat-inactivated Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Edwardsiella sp. Aquacult. Int. 2019;27:33–51. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abdel Rahman A.N., Mansour D.A., Abd El-Rahman G.I., Elseddawy N.M., Zaglool A.W., Khamis T., Mahmoud S.F., Mahboub H.H. Imidacloprid toxicity in Clarias gariepinus: protective role of dietary Hyphaene thebaica against biochemical and histopathological disruption, oxidative stress, immune genes expressions, and Aeromonas sobria infection. Aquaculture. 2022;555 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Janda J.M., Abbott S.L. The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;23:35–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ibrahim R.E., Amer S.A., Shahin S.A., Darwish M.I., Albogami S., Abdelwarith A.A., Younis E.M., Abduljabbar M.H., Davies S.J., Attia G.A. Effect of fish meal substitution with dried bovine hemoglobin on the growth, blood hematology, antioxidant activity and related genes expression, and tissue histoarchitecture of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Aquac. Rep. 2022;26 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abdel Rahman A.N., Shakweer M.S., Algharib S.A., Abdelaty A.I., Kamel S., Ismail T.A., Mahboub H.H. Silica nanoparticles acute toxicity alters ethology, neurostress indices, and physiological status of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) Aquac. Rep. 2022;23 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ibrahim R.E., Elshopakey G.E., Abd El-Rahman G.I., Ahmed A.I., Altohamy D.E., Zaglool A.W., Younis E.M., Abdelwarith A.A., Davies S.J., Al-Harthi H.F., Abdel Rahman A.N. Palliative role of colloidal silver nanoparticles synthetized by moringa against Saprolegnia spp. infection in Nile Tilapia: biochemical, immuno-antioxidant response, gene expression, and histopathological investigation. Aquacult. Rep. 2022;26 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fontagné-Dicharry S., Lataillade E., Surget A., Larroquet L., Cluzeaud M., Kaushik S. Antioxidant defense system is altered by dietary oxidized lipid in first-feeding rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquaculture. 2014;424:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garcia D., Lima D., da Silva D.G.H., de Almeida E.A. Decreased malondialdehyde levels in fish (Astyanax altiparanae) exposed to diesel: evidence of metabolism by aldehyde dehydrogenase in the liver and excretion in water. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;190 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdel Rahman A.N., Mahmoud S.M., Khamis T., Rasheed N., Mohamed D.I., Ghanem R., Mansour D.M., Ismail T.A., Mahboub H.H. Palliative effect of dietary common sage leaves against toxic impacts of nonylphenol in Mirror carp (Cyprinus carpio var specularis): growth, gene expression, immune-antioxidant status, and histopathological alterations. Aquac Rep. 2022;25 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tkachenko H., Kurhaluk N., Andriichuk A., Gasiuk E., Beschasniu S. Oxidative stress biomarkers in liver of sea trout (Salmo trutta m. trutta L.) affected by ulcerative dermal necrosis syndrome, Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014;14:391–402. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghasemnezhad M., Sherafati M., Payvast G.A. Variation in phenolic compounds, ascorbic acid and antioxidant activity of five coloured bell pepper (Capsicum annum) fruits at two different harvest times. J. Funct.Foods. 2011;3:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abdel‐Ghany H.M., Salem M.E.S. Effects of dietary chitosan supplementation on farmed fish; a review. Rev. Aquacult. 2020;12:438–452. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mohamed W.A., El-Houseiny W., Ibrahim R.E., Abd-Elhakim Y.M. Palliative effects of zinc sulfate against the immunosuppressive, hepato-and nephrotoxic impacts of nonylphenol in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Aquaculture. 2019;504:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abdel Rahman A.N., Masoud S.R., Fouda M.M.S., Abdelwarith A.A., Younis E.M., Khalil S.S., Zaki H.T., Mohammed E., Davies S.J., Ibrahim R.E. Antimicrobial efficacy of magnetite nanoparticles against Aeromonas sobria challenge in African catfish: biochemical, protein profile, and immuno-antioxidant indices. Aquac. Rep. 2023;32 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mahboub H.H., Shahin K., Mahmoud S.M., Altohamy D.E., Husseiny W.A., Mansour D.A., Shalaby S.I., Gaballa M.M.S., Shaalan M., Alkafafy M., Abdel Rahman A.N. Silica nanoparticles are novel aqueous additive mitigating heavy metals toxicity and improving the health of African catfish, Clarias gariepinus. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022;249 doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2022.106238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu J., Koo B.H., Kim D.H., Kim D.W., Park S.W. Aeromonas sobria infection in farmed mud loach (Misgurnus mizolepis) in Korea, a bacteriological survey, Iran. J. Vet. Res. 2015;16:194–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saeij J.P., Stet R.J., Groeneveld A., Verburg-van Kemenade L.B., Van Muiswinkel W.B., Wiegertjes G.F. Molecular and functional characterization of a fish inducible-type nitric oxide synthase. Immunogenetics. 2000;51:339–346. doi: 10.1007/s002510050628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uribe C., Folch H., Enríquez R., Moran G. Innate and adaptive immunity in teleost fish: a review. Vet. Med. 2011;56:486. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kania P.W., Buchmann K. Springer; 2022. Complement Activation in Fish with Emphasis on MBL/MASP, Principles of Fish Immunology; pp. 279–300. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Talpur A.D., Ikhwanuddin M. Azadirachta indica (neem) leaf dietary effects on the immunity response and disease resistance of Asian seabass, Lates calcarifer challenged with Vibrio harveyi. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013;34:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cha S.-H., Lee J.-S., Song C.-B., Lee K.-J., Jeon Y.-J. Effects of chitosan-coated diet on improving water quality and innate immunity in the olive flounder. Paralichthys olivaceus, Aquaculture. 2008;278:110–118. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abdel-Tawwab M., Razek N.A., Abdel-Rahman A.M. Immunostimulatory effect of dietary chitosan nanoparticles on the performance of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;88:254–258. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Victor H., Zhao B., Mu Y., Dai X., Wen Z., Gao Y., Chu Z. Effects of Se-chitosan on the growth performance and intestinal health of the loach Paramisgurnus dabryanus (Sauvage) Aquaculture. 2019;498:263–270. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.