Abstract

Organophosphorus Pesticides (OPPs) are among the extensively used pesticides throughout the world to boost agricultural production. However, persistent residues of these toxic pesticides in various vegetables, fruits, and drinking water poses detrimental health effects. Consequently, the rapid monitoring of these harmful chemicals through simple and cost-effective methods has become crucial. In such an instance, electrochemical methods offer simple, rapid, sensitive, reproducible, and affordable detection pathways. To overcome the limitations associated with electrochemical enzymatic sensors, non-enzymatic sensors have emerged as promising and simpler alternatives. The non-enzymatic sensors have demonstrated superior activity, reaching detection limit up to femto (10−15) molar concentration in recent years, leveraging higher selectivity obtained through the molecularly imprinted polymers, synergistic effects between carbonaceous nanomaterials and metals, metal oxide alloys, and other alternative approaches. Herein, this review paper provides an overview of the recent advancements in the development of non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors for the detection of commonly used OPPs, such as Chlorpyrifos (CHL), Diazinon (DZN), Malathion (MTN), Methyl parathion (MP) and Fenthion (FEN). The design method of the electrodes, electrode functioning mechanism, and their analytical performance metrics, such as limit of detection, sensitivity, selectivity, and linearity range, were reviewed and compared. Furthermore, the existing challenges within this rapidly growing field were discussed along with their potential solutions which will facilitate the fabrication of advanced and sustainable non-enzymatic sensors in the future.

Keywords: Organophosphorus pesticide, Electrochemical methods, Detection, Non-enzymatic sensors, Limit of detection

1. Introduction

In the last 20 years, the world population number has increased by almost 1.6 billion and so did the demand for food [1]. To facilitate the efficient production of food to meet the growing demand of the world population, the utilization of pesticides in agricultural sector is witnessing a substantial rise to enhance agricultural output by effectively managing plant diseases and pests [2]. 64% of the global agricultural land were reported to possess the high risk of being polluted by more than one type of pesticide [3]. According to data revealed by United States Geological Survey's (USGS), approximately 1 billion pounds of pesticides are applied annually in the United States [4]. Globally, more than 4 million tons of pesticides are applied for crop production annually [5]. Additionally, newer formulations of pesticides are being discovered regularly based on the requirement of agricultural industry. United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) estimated that more than 865 pesticides have been registered by 2021 [6]. Considering the global risk potential and hazards from pesticides originating from anthropogenic sources, Ippolito et al. presented a map of global land area affected by pesticide pollution and will contaminate the surface water as well [5]. Fig. 1 displays the 43% global land mass that is at risk of undergoing pesticide pollution due to human activities classified into very low to very high contamination.

Fig. 1.

Spatial distribution map showing potential pesticide pollution at global scale. Reproduced from Ref. [5] with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2015.

Pesticides are categorized into distinct groups based on their chemical structure, including organophosphates, organochlorines, carbamates, neonicotinoids, pyrethroids etc. [7]. Among these pesticide types, organophosphorus pesticides (OPPs) are among widely employed globally and account for a significant proportion of pesticide usage [8]. In the United States alone, approximately 70% of the total pesticide usage annually is attributed to OPPs, with nearly 75% of the total amount used primarily applied in agricultural fields [9].

Some of the most heavily utilized OPPs include chlorpyrifos (CHL), diazinon (DZN), malathion (MTN), methyl parathion (MP) and fenthion (FEN). US EPA established the Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for these OPPs in various foods, with limits ranging from 0.01 ppm to 3 ppm depending on the specific OPP and food type [10,11]. However, in recent times, the excessive use of pesticides has led to the increased detection of OPP residues in fruits and vegetables [6].

All OPPs share a common mechanism of action in damaging the human nervous system. They inhibit the acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase enzymes, which play crucial role in the hydrolysis of acetylcholine into choline and acetate [12]. This inhibition leads to a disruption in the normal physiology of the nervous system [[13], [14], [15]]. The neurotoxicity of OPPs has a particular detrimental impact on developing nervous system such as those found in children. In immature nervous systems, the acute cholinergic effects of OPPs can result in permanent damage, while the effects in grown-ups may be temporary and sometimes reversible [16]. In the USA, pesticides poisoning had a significant impact on children, with approximately 74,000 cases reported [17]. Additionally, a scientific study found the link between exposure to OPPs and an increased risk of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases [18]. Further research conducted by Sinha et al. investigated the fatalities associated with OPP-caused diseases and found that 24.1% of the patients resulted in death [19]. Alarmingly, a report suggests that approximately 300,000 individuals die each year as a result of pesticide poisoning [20].

Due to the lack of knowledge regarding the appropriate dosage, farmers often resort to excessive usage of OPPs in their farmlands [21]. Consequently, it becomes imperative to regularly detect and monitor the toxicity levels of OPPs in crops in order to aid policy makers in establishing appropriate limits for pesticide dosage, thus promoting safe agricultural practices. Several customary chromatographic methods, including gas chromatography (GC), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), liquid chromatography, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [[22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]], and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with UV detector [[28], [29], [30]], are commonly employed for OPP detection. While these chromatographic techniques are considered more flourished and advanced, they come with certain limitations such as expensive instrumentation and complex sample preparation. Moreover, the separation step in chromatographic methods requires finite analysis time, thereby lacking real-time monitoring capabilities.

Literature reviews have highlighted alternative OPP detection methods, including fluorescent and colorimetric methods [31], spectroscopic techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), X-ray, Fourier transform infra-red (FTIR) spectroscopy [32], as well as electrochemical methods [33,34]. Among these options, optical methods like colorimetric and spectroscopic methods, which rely on the interaction between light and matter, are prone to interference from other compounds in the system and susceptible to high noise levels under unfavorable detection conditions [31]. This interference effect can lead to false-negative or false-positive results. In such cases, electrochemical methods provide more reliable and accurate results that can be performed using simple instrument like potentiostat, enabling on-site dynamic detection of OPPs [35]. Electrochemical sensors are gaining popularity nowadays due to their ease of miniaturization and low detection limit reaching nanomolar concentrations [36].

Enzymatic and non-enzymatic are two widely utilized types of electrochemical sensors [37]. Enzymatic electrochemical sensors employ enzymes to catalyze the reaction between the analyte and electrode surface, whereas non-enzymatic sensors rely on the direct electrochemistry of the analyte on noble metals [38]. Enzymatic sensors offer higher selectivity compared to non-enzymatic sensors [39]. Mishra et al. developed a wearable electrochemical sensor based on organophosphorus hydrolase enzyme for the detection of OPPs in various food samples [40]. Numerous enzymatic sensors based on acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme have been extensively developed leveraging the binding affinity between OPPs and the active sites of AChE [[41], [42], [43], [44]]. Guler et al. developed an enzymatic sensor using a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) modified with AChE and a conducting polymer for the detection of MTN, exhibiting a linear range of 9.99–99.01 nM with a detection limit 4.08 nM [42]. Itsoponpan et al. designed a sensitive reduced graphene oxide (rGO)-based enzymatic electrochemical sensor for CHL detection, with a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.023 ng mL−1 and a wide linear range of 0.5–470 ng mL−1 [43]. Herrera et al. fabricated an ultra-sensitive rGO based DZN biosensor (LOD = 0.3 ppb) [45]. Electrochemical enzymatic sensors offer high specificity, sensitivity, low detection limit, and rapid response for the detection of OPPs [44,46,47].

Enzymatic sensors, though known for their high selectivity, are physically unstable at high temperatures and in acidic or basic solutions [37,[48], [49], [50]]. They may not effectively detect less toxic OPPs, as these low toxic OPPs inhibit AChE only after metabolic action [51]. Such phenomena impede the proper functioning of AChE based enzymatic sensors. In such cases, conversion of P S bond into P O in the OPP structure is required to increase the toxicity of OPP [14]. Additionally, enzyme-based biosensors are disadvantageous in terms of their high cost, low reproducibility, and decreased enzymatic performance over time [52]. The presence of heavy metals in the sample matrix can interfere with the selectivity of enzymatic sensors, leading to false-positive results [52,53]. A comparison between the enzymatic and non-enzymatic sensors, taking into account diverse sensor parameters, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Typical comparison between enzymatic and non-enzymatic sensors.

| Parameters | Enzymatic Sensor | Non-enzymatic Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Enzymatic OPP sensors are highly specific to OPP. | Their specificity can vary from moderate to low. |

| Stability | They are unstable at high temperatures and in acidic or basic solutions. | They have a broad working temperature and pH range. |

| Cost | Enzymes are expensive which makes sensor preparation costly. | These sensors can be prepared using non-precious metals and non-metals. |

| Interference | They are susceptible to interference from heavy metals. | These sensors are less affected by interference. |

| Required Sample | Sample should be pure and clean to retain sensor performance. | Sensors are more tolerant to impurities in sample. |

Due to the notable advantages, the development of non-enzymatic sensor materials for detecting OPPs has gained considerable interest in recent years. The development seeks to overcome the limitations associated with enzymatic sensors, making non-enzymatic sensors a robust alternative for OPP detection. Fig. 2 demonstrates the temporal trend in the publication of documents focusing on electrochemical sensing of OPPs between the years 2012 and 2022. The analysis of Fig. 2A indicates a notable surge in research concerning non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors in recent years, surpassing a threshold of 100 publications annually, nearly doubling the number of published documents from 2021 to 2022 in the field. In contrast, studies related to enzyme-based OPP sensors have exhibited a relatively stable trajectory over the past five years (Fig. 2B). However, both categories of research experienced a sudden decline in 2020, which can be attributed to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly distracting research activities to other fields.

Fig. 2.

Trends in the number of published literatures on electrochemical (A) non-enzymatic sensors and (B) enzymatic sensors for detecting OPPs within the last 10 years based on Scopus data.

The most challenging part in developing an electrochemical non-enzymatic sensor is choosing the proper electrode material [54]. Metal alloys incorporating two or more metals as electrode components have emerged as pioneers in the advancement of efficient electrocatalysis [[55], [56], [57]]. Notably, metal oxides have shown enhanced electronic properties and exceptional stability, even at high temperatures up to 1000 °C, as well as resistance to oxidative decay and electromagnetic radiation, surpassing their metal and metal alloy counterparts [58]. In recent years, oxides of various metals such as Fe, Cu, Ni, Bi, W, and Ti have garnered significant attention for electrode modification [[59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64]]. Furthermore, the fusion of polymers and carbonaceous nanomaterials, for example carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene, with metal oxides is pushing the frontier of metal oxide research by enhancing their electronic properties [[65], [66], [67], [68], [69]]. Several review articles have been published concerning electrochemical sensors for detecting OPPs [[70], [71], [72]]. However, the current body of literature on non-enzymatic electrochemical detection of OPPs, which is experiencing rapid expansion, remains unexplored by these reviews. In this review paper, we have discussed a wide variety of suitable electrode materials, including noble metals, metal nanocomposites, metal oxides, and incorporation of carbonaceous materials followed by their high sensitivity towards different OPPs. Our objective is to explore the performance of different recently developed modified noble metal and non-metals utilized in the fabrication of non-enzymatic sensors and their analytical capabilities for the detection of five mostly used OPPs: chlorpyrifos (CHL), diazinon (DZN), malathion (MTN), fenthion (FEN), and methyl parathion (MP).

2. Function of organophosphorus pesticides and their toxicity

Pesticides are frequently used worldwide in agriculture to control growth of weeds and various microbes to ensure high production yield. The general chemical structure of OPPs is shown as Fig. 3, where R1 and R2 are alkoxy groups. Some other possible substitutes are phenyl, ethyl, amino, substituted amino, and alkylthio, X is a perfect leaving group which is sensitive to hydrolyze and is displaced when phosphorylation of AChE occurs by OPPs [73].

Fig. 3.

General chemical structure of an OPP [74].

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) plays crucial role in the regulation of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter responsible for transmitting signals from nerve cells to muscle cells. Upon receiving a nerve impulse from the nervous system, motor nerve cells release acetylcholine from vesicles. The acetylcholine the stimulates muscle contraction by binding to receptors in the muscles [[74], [75], [76]]. Once the signal transmission is complete, acetylcholine undergoes hydrolysis by AChE, leading to the formation of choline and acetic acid, as depicted in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Hydrolysis reaction of Acetylcholine catalysed by AChE [77].

The degradation of acetylcholine is a crucial process because it would get accumulated with the later signals otherwise. Herein, AChE functions as a neurotransmission terminator, playing a vital role in regulating acetylcholine levels. Inhibition of AChE disrupts this regulation of acetylcholine enabling pesticides to exert their lethal effects on various insects [78]. AChE enzyme is classified as a serine hydrolase [79], and is primarily secreted by the muscles [80]. OPPs inhibit the AChE by undergoing phosphorylation of the serine hydroxyl group present in the active site of the enzyme. This phosphorylation leads to inactivation of AChE [14]. Consequently, acetylcholine bioaccumulates due to the inactivation of AChE by OPPs, resulting in overstimulation of the nervous system and ultimately leading to death or paralysis of the insects [81,82]. The inhibition of AChE by OPPs occurs through a two-step chemical reaction as illustrated in Scheme 2. The phosphorylation of the serine hydroxyl group results in the formation of a stable phosphorylated AChE enzyme. In many cases, this reaction is irreversible. Since the active serine hydroxyl group is blocked, the inactivated AChE can no longer degrade any acetylcholine [74,77,83,84].

Scheme 2.

Phosphorylation of AChE by OPP [74,77]. X represents a leaving group, kd is the dissociation related constant between the reactants and enzyme-inhibitor complex, and kp is the phosphorylation constant.

OPPs non-specifically damage the nervous system of any animal, human or fishes [48]. Different OPPs were reported to have serious health effects on human body. CHL has endocrine disruptor property [85]. DZN is regarded as a chemical mutagen and extremely toxic for human health, fishes in water and other organisms [[86], [87], [88], [89]]. According to California Environmental Protection, even as low as 120 ppm DZN can kill fishes in water [86]. For its toxicity, it has been used as a neurotoxin warfare agent previously [90]. The resulting abnormalities in the body from OPPs severely damage the nervous system physiology and ultimately lead to death [15]. Disruption in the nervous system can also weaken the hand and feet muscle, and cause dizziness, delirium, headache, and depression. Harmful effect on blood cells, thymus, lymph, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, skin, and other parts of the body in humans and animals were also reported [23,[91], [92], [93]]. FEN is another neurotoxic OPP whose residue can persist in the environment for about 28–42 days [94]. It was found to cause harmful health effects like vomiting, diarrhoea, skin irritation, etc. [95,96]. The MRL for FEN set by World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations is 1 mg/kg body weight [8].

3. General mechanism of electrochemical OPP detection

3.1. Chlorpyrifos detection

Chlorpyrifos (CHL) is an extensively used OPP. The Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations (FAO) has set the maximum acceptable daily intake (ADI) level of chlorpyrifos at 0.01 mg/kg body weight [97]. The chemical name of CHL is O,O-diethyl O-3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyl phosphorothioat [98], and its chemical structure is depicted in Fig. S1a. Due to its inability to undergo self-oxidation reactions, most of the CHL sensors rely on an electro-oxidative signal inhibition strategy.

Zheng et al. developed a sensor based on Pralidoxime chloride (PAM-Cl) modified GCE using an inhibition method, which can simultaneously detect CHL, FEN, and MP with an LOD of 0.018 μM, 0.100 μM and 0.215 μM, respectively [14]. Notably, the sensor exhibited the highest sensitivity towards CHL. As we know in OPP poisoning, the phosphorylation of the serine hydroxyl group of the active site of AChE lead to enzyme inactivation. However, PAM can reactivate the enzyme by undergoing phosphorylation with the inactivated AChE. PAM-Cl possesses a higher tendency towards phosphorylation of CHL compared to that of AChE. For this unique property of PAM, it is used as an antidote to OPP poisoning [99]. The redox properties of PAM-Cl modified GCE were characterized using cyclic voltammetry (CV) technique. Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) was employed for further investigation of the electrode's behaviour under different pH conditions and examine the relation between OPP and PAM-Cl. In CV, the peak current of PAM-Cl decreased as the concentration of CHL increased. The electrode also demonstrated the capability to detect FEN and MP although with lower sensitivity. MP exhibits redox activity, but no peak for MP appeared within the working potential range specified in this study (0.5 V–1V).

The utilization of nano sensors has gained significant popularity due to their enhanced sensitivity, which is attributed the large surface area of the electrode materials [67]. However, a notable challenge arises when fabricating nano based sensors using a simple drop casting method, as the random arrangement of nano particles on the electrode surface leads to issues of reproducibility. To address this drawback, the development of sensors using template growth controlling and directing agents has been proposed to ensure uniform morphology of nanostructures on different electrodes. This approach not only improves the reproducibility of the electrodes but also enhances their electrochemical characteristics.

Tunesi et al. have made advancements in improving the sensitivity of the previously discussed sensor based on PAM-Cl by incorporating a template growth controlling agent [100]. Copper oxide (CuO) has exhibited remarkable electrocatalytic properties in a multitude of scientific investigations [61,62]. In this sensor, CuO nanostructures were grown in-situ on an Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) electrode. A high surface coverage of Cu nanoparticles (CuNPs) was then immobilized with PAM-Cl, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Similar to the aforementioned PAM-based sensor, this sensor operates on an electro-oxidative signal inhibition strategy. In this case, pimelic acid was employed as a growth controlling template due to its negatively charged portions, which facilitate the immobilization of positively charged nitrogen in pyridine sites of PAM-Cl structure. Pimelic acid also plays a role in controlling the spatial arrangement of CuO nanostructure. The interaction between CuO and pimelic acid, along with the high surface area of CuO, allows for a higher loading of PAM on the surface, resulting in enhanced signals. For the electrochemical evaluation of the electrode, CV method was performed in the range of 0–1.2 V at a scan rate of 50 mVs−1. DPV was utilized for the quantitative measurement of CHL, which is the target compound. The sensor is also capable of detecting other OPPs, such as FEN and MP, although CHL exhibits the lowest limit of detection (1.6 nM).

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the template-assisted preparation of PAM-Cl based sensor for detecting CHL using signal inhibition strategy [100].

Zahran et al. developed an inhibition-based sensor for the detection of CHL based on the inhibition of silver nanoparticle (AgNP) oxidation [78]. AgNPs possess antibacterial, catalytic and electrochemical properties, making them suitable for sensor application. In this study, three types of electrodes with different capping layers were prepared to enhance the inhibition of AgNP oxidation by CHL and prevent AgNP dissolution into Ag+ ions. The three capping layers used were dissolved organic matter (DOM), natural latex (NL), and mucilage. The electrode coated with DOM exhibited an oxidation signal that was influenced by various cationic interferences. On the other hand, the other two electrodes, coated with natural latex and mucilage, demonstrated relatively higher resistance to interference from different cations. The inhibition signal was obtained using square wave voltammetry (SWV). Another AgNPs based CHL sensor was developed by Porto et al., where they employed a pyrolytic graphite electrode (PGE) modified with AgNPs and functionalized CNTs for the sensitive detection of three OPPs, namely CHL, DZN, and MTN, at distinct potentials [101]. The analysis involved direct injection of the samples onto the electrode surface, employing a technique known as batch injection analysis (BIA), combined with multiple pulse amperometry. The proposed method exhibited a high sensitivity of 0.043 mA L μmol−1 with an LOD of 0.53 μmol L−1 for the detection of CHL within a linear range of 0.25–50 μmol L−1.

The utilization of conducting polymer-based nanostructures doped with inorganic nanomaterials for electrochemical sensing has gained significant popularity in recent years [[102], [103], [104]]. While most electrodes are developed based on the redox inhibition signal strategy, Joshi et al. fabricated a tungsten carbide (WC) doped polyindole (PIN) electrode on a stainless steel substrate, enabling direct measurement of CHL through a one-electron transfer redox behaviour of CHL on the electrode surface [105]. PIN is a highly conducting polymer, and the addition of WC to the PIN electrode enhances its conductivity. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) data revealed a synergistic increase in conductivity with the increasing concentration of WC in the PIN electrode. The PIN electrode doped with WC exhibited a higher peak current in SWV compared to the bare PIN electrode, indicating an improved electron transfer at the PIN surface after doping with WC. Analysis of the peak potential in CV data allowed the determination of reaction kinetics and suggested that the redox reactions of CHL over the electrode surfaces follows a one-electron transfer mechanism. Moreover, SWV measurements indicates that the Faradaic current increases as the concentration of CHL increases demonstrating the sensitivity of the electrode towards CHL detection.

Kumaravel et al. have developed an electrode that operates based on the redox behaviour of CHL, which contains a phosphate group. CHL, due to its low solubility in water, requires the use of dimethylformamide (DMF) as solvent, which is a methanolic solution. TiO2 has high affinity towards phosphate group, while cellulose acetate (CA) is a porous material and stable in alcoholic solution. CA is used to immobilize metallic nanoparticle, enzyme and bacteria on electrode surface. By utilizing these unique properties of TiO2 and CA, Kumaravel et al. have developed a nano-TiO2/Cellulose Modified GCE for detection of CHL [54]. During CV analysis, a reduction peak at approximately −1.55 V was observed, corresponding to the electro-reduction of the –C N bond in the pyridine ring of CHL through a two-electron transfer mechanism (shown in Scheme 3). The presence of three chlorine (Cl) atoms in the pyridine ring facilitates the reduction of the –C N bond. Importantly, the relatively high reduction potential of −1.55 V distinguishes CHL from other pesticides, as they typically exhibit peaks at lower potentials.

Scheme 3.

Electro-reduction of Chlorpyrifos [54].

Mercury-based electrodes are well recognized for their capacious cathodic potential window and high sensitivity in the determination of CHL. For instance, a stripping voltammetric method based on the accumulation of CHL on a Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) achieved an LOD as low as 4 × 10−10 M [106]. However, due to the toxic nature of mercury, its use is prohibited in certain countries. To address this toxicity concern, Fischer et al. developed a non-toxic alternative in the form of a mercury-modified Ag Solid Amalgam electrode (m-AgSAE) [85]. The electrode exhibits a signal associated with the reduction of CHL, which occurs at the –C N bonds with the exchange of 2H+ and 2e− at the mercury electrode surface [54]. One drawback of the m-AgSAE is its limited repeatability, as the working electrode becomes passivated with repeated measurements. Consequently, the peak current in DPV decreases with each measurement. To overcome this issue, a freshly prepared mercury meniscus is required for each set of measurements. Although the electrode offers simplicity and non-toxicity compared to previously reported mercury-based electrodes [[106], [107], [108]], it exhibits lower sensitivity. Table 2 summarizes some of the recently developed non-enzymatic sensors for detecting CHL in different food and environmental samples.

Table 2.

Performances of different CHL sensors in real samples.

| Electrode Materials | Technique | Linearity | LOD | Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAM-Cl/GCE | CV & DPV | – | 0.018 μM (6.3 μgL−1) | Chinese cabbage, Pakchoi, Corn | [14] |

| PAM-Cl/CuO/ITO | CV & DPV | 0.01–0.16 μM | 1.6 nM | Cabbage and Spinach | [100] |

| PIN/WC/SS | CV & SWV | – | 5.94 × 10−8 M (5% wt of WC) | – | [105] |

| DOM-AgNp, NL-AgNp/GCE, Mucilage AgNp/GCE |

SWV | 100–640 μg/L (DOM) 40–420 μg/L (NL) 40–220 ng/L (Mucilage) |

48 μg/L (DOM) 30.5 μg/L (NL) 17.2 ng/L (Mucilage) |

River Water | [78] |

| TiO2/CA/GCE | CV, DPV & Amperometry | 10–130 μM (CV) 20–110 μM (DPV) 20–340 μM (Amperometry) |

4.4 μM (CV) 3.5 μM (DPV) 11.8 μM (Amperometry) |

Water | [54] |

| m-AgSAE | DPV | – | 2.6 × 10−6 M | Drinking and River water | [85] |

| AgNPs/fCNT/PGE | Amperometry | 0.25–50 μM | 0.53 μM | Tap water, orange juice, and apple fruit | [101] |

| PPy/Au-μE | DPV | 1.0 × 10−9–1.0 μM | 0.9 fM | Fruit and vegetable | [109] |

| ICP@MWCNT/GCE | DPV | 0.2 × 10−4–1.0 μM | 4.0 × 10−6 μM | Vegetable | [110] |

| CuO NRs | CV | – | 0.20 mg/L | Drinking Water | [111] |

PAM-Cl:Pralidoxime Chloride; GCE:Glassy Carbon Electrode; ITO:Indium tin oxide; PIN:Polyindole; WC:Tungten Carbide; SS:Stainless Steel; DOM:Dissolved Organic Matter; NL:Natural Latex; CA:Cellulose Acetate; m-AgSAE:mercury modified Ag Solid Amalgam electrode;AgNPs: Silver Nanoparticles;fCNT: Functionalized Carbon Nanotube;PGE: Pyrolytic Graphite Electrode;PPy: Polypyrrole;Au-μE:Gold Microelectrodes;ICP: Molecular Imprinting with a Conducting Polythiophene copolymer;MWCNT: Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes;CuO NRs: Copper (II) Oxide Nanorods;CV: Cyclic Voltammetry.

3.2. Diazinon detection

Diazinon (DZN) has been identified as a genotoxic substance by WHO, and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI), as established by WHO and FAO for DZN, is set at 0.003 mg/kg body weight [112]. The IUPAC name for DZN is O,O-Diethyl O-[4-methyl-6-(propan-2-yl)pyrimidin-2-yl] phosphorothioate [113]. The chemical structure of DZN can be seen in Fig. S1b.

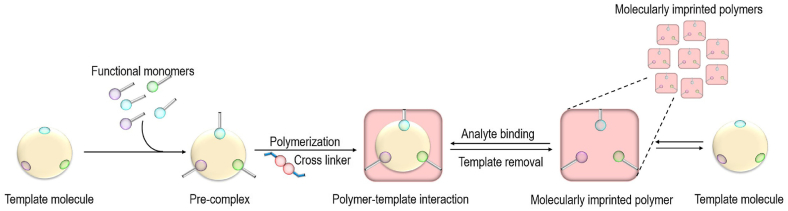

In recent years, the utilization of molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) in electrode modification has gained significant interest among sensor developers [114,115]. Enzymatic sensors have traditionally held an advantage over non-enzymatic sensors in terms of their ability to detect the target analyte with high specificity. The specificity of enzymatic sensors is attributed to the unique shape and properties of the enzyme's active sites. Meanwhile, a single non-enzymatic sensor may exhibit sensitivity to multiple OPPs. However, by integrating MIP into non-enzymatic sensors, they can mimic the function of enzymes and acquire high selectivity as well as sensitivity towards the target analyte. The development of MIP involves polymerization of cross-linkers and functional monomers in association of a template molecule [87,116,117]. The template molecule controls the formation of specific structure, size, and stereo-specific cavities within the polymer of the target analyte. Subsequently, the template is removed, leaving behind cavities that can selectively rebind with the target analyte. A schematic presentation illustrating the development of MIP is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Schematic approach of the synthesis of molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP). Reproduced from Ref. [118] with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2023.

Motaharian et al. developed an electrochemical sensor for DZN detection using a modified Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE) with a DZN imprinted polymer [115]. The use of MIP nanoparticles, instead of larger materials, offers the advantage of a high surface area which provides abundant adsorption sites for the detection of DZN molecules. The MIP was prepared using DZN as a template molecule, followed by the thorough removal of the template molecules through washing, thereby creating adsorption sites for real sample analysis (shown in Fig. 6). After modifying the CPE with the MIP, the electrode was immersed in real sample for DZN adsorption. The adsorbed DZN was detected by SWV method under optimized pH condition (pH = 3.5). Graphite powder was used for preparing the CPE, and the optimized ratio of MIP in the CPE modification is 15% nano-MIP and 58% graphite. Khadem et al. prepared even an upgraded version of this MIP based electrode [87]. They utilized an amalgamation of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNT) nanostructure and MIP using DZN as the template molecule to modify the CPE. The incorporation of MWCNT, with its large surface area, high electrical conductivity, and good chemical stability, significantly enhanced the sensitivity of the electrode. The compound of MIP and MWCNT served as an excellent modifying agent for CPE, enabling the detection of DZN with an LOD of 1.3 × 10−10 M within in a concentration range of 5 × 10−10 to 1 × 10−6 M. The sensor successfully detected DZN in real samples of tap water, human urine, and river water without requiring any special modifications of the samples.

Fig. 6.

Schematic diagram for preparation and utilization of molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) in the detection of DZN molecules [115].

Taking advantage of the vast surface area of MWCNT, another MWCNT modified GCE was developed by Ghodsi and Rafati [119]. MWCNT was covered with Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) that provided a greater sensitivity for reduction of DZN via a two-electron transfer process (see Scheme 4) as well as diffusion-controlled kinetics.

Scheme 4.

Two consecutive electroreduction of Diazinon molecule [119].

TiO2 is popular as a semiconductor that can be used for electrocatalysis of redox reaction of organic and inorganic species [120,121]. Moreover, TiO2 has high affinity towards phosphate group in OPPs that makes it a promising metal oxide for detection of various OPPs like diazinon, parathion and fenitrothion [54,[121], [122], [123], [124]]. The sensor demonstrated enhanced sensitivity when employing the Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) technique compared to other electrochemical methods. The combination of TiO2 nanoparticles with MWCNT exhibited a synergistic effect, resulting in a significantly expanded linear range (11 nm-8360 nm) for the detection of DZN in phosphate buffer solution. The sensor achieved an LOD of 3 nM, indicating high sensitivity towards DZN.

Another carbon nanotube (CNT) modified simple sensor was developed by Zahirifar et al. that can sense DZN with an impressive LOD of 0.45 nM [125]. Carbon paste electrode (CPE) modified with CNT demonstrated a decrease in charge transfer resistance as observed in EIS, compared to unmodified CPE. The incorporation of CNT into the CPE also led to an enhancement in sensitivity of the electrode. It should be noted that the reduction of DZN requires protons [119]. Therefore, it is important to maintain a solution pH below 5.25 to ensure optimal signal response for DZN detection.

The fabrication of electrochemical sensors involves extensive experimentations and optimization processes before being considered as novel and useful. The processes of experiment are time consuming and costly. Ghiasi et al. implemented the Taguchi method to reduce the cost and experimental run in the development of a Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs), Chitosan (CS), and Nickel Molybdate nanocomposite-modified GCE for the detection of DZN, achieving an LOD of 27 nM [126]. The Taguchi method is employed to determine the optimal conditions for various experimental parameters such as deposition time, pH, amplitude modulation, and potential step [127,128]. Quantum Dots have gained significant recognition as biological sensors [129]. However, GQDs possess unique characteristics compared to other quantum dots for having carbonyl, hydroxyl, carboxyl functional groups, and a high surface area of 2630 m2 per gram [126]. This large surface area combining with high electrical conductivity has made GQDs a popular substance for modifying electrodes. NiMoO4 is used to modify sensors for its enhanced electrochemical performance [130]. Chitosan, known for its biocompatibility and fast ion transfer rate, is commonly used for electrode. By activating the GCE in the potential window of -1 V–2 V, negative charges are induced on the electrode surface, allowing for facile immobilization of chitosan, which contains amine and hydroxyl group [[131], [132], [133]]. The chitosan-immobilized GCE surface served as a platform for attaching various functional groups containing GQDs. EIS data demonstrated that the sensor exhibited very low electron transfer resistance. The reduction of DZN occurred via a two electron and two proton transfer process [86,134,135] The sensor showed better sensitivity in low pH (pH = 3) due to the requirement of H+ ion for the electrochemical reduction of DZN.

Among the nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) are specially known for its capability of bio-sensing and detection of toxic substances [136,137]. Palladium nanoparticles (Pd NPs) have great use in sensing electro-oxidizable compounds and gas sensing [[138], [139], [140]]. Tadayon & Jahromi developed a GCE based DZN sensor that was reshaped with a mixture of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and MWCNT and doped with bimetallic Au–Pd NPs [141]. Combination of both noble metal NPs showed higher electrocatalytic property than their individual performances arising from their synergistic effect. The NPs caused higher electrical current signal and lower peak potential during the electro-oxidation of DZN, compared to the undoped electrode.

Additionally, rGO possesses a remarkably large surface area, while MWCNTs exhibit exceptionally high electrical conductivity ranging from 103 to 106 S/cm. As a result, Au–Pd/rGO–MWCNTs modified sensor demonstrates approximately four times greater active surface area compared to the bare GCE. EIS analysis revealed that this sensor exhibits 12 times less charge transfer resistance compared to pristine GCE. The electro-oxidation of DZN takes place on the surface of the sensor at a peak potential of 0.45 V. The oxidation reaction followed a diffusion-controlled kinetics. Some of the recently developed electrochemical DZN sensors are tabulated in Table 3 with their corresponding analytical figures.

Table 3.

Performances of different DZN sensors in real samples.

| Electrode Material | Technique | Linearity | LOD | Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nano-MIP-CPE | CV & SWV | 1.2.5 × 10−9 to 1 × 10−7 M 2.1 × 10−7 to 2 × 10−6 M |

0.79 nM | Well water and apple fruit | [115] |

| MIP-MWCNTs-CPE | SWV | 5 × 10−10 to 1 × 10−6 M | 0.13 nM | Human urine,tap, and river water | [87] |

| TiO2NPs/MWCNTs/GCE | CV &SWV | 11–8360 nM | 3 nM | City piped water and agricultural well water | [119] |

| NMO/GQDs/CS/GCEox | DPV | 0.1–330 μM | 27 nM | Cucumber, tomato | [126] |

| CNT/CPE | CV & DPV | 1 × 10−10 to 6 × 10−8 M | 0.45 nM | Fruits and Vegetables | [125] |

| Au–Pd/rGO–MWCNTs/GCE | SWASV | 0.009–11.3 μM | 2 nM | Water, apple and cucumber samples | [141] |

| AgNPs/fCNT/PGE | Amperometry | 0.1–20 μM | 0.35 μM | Tap water, orange juice, and apple fruit | [101] |

MIP:Molecularly Imprinted Electrode;CPE:Carbon Paste Electrode;MWCNTs:Multi Walled Carbon Nanotubes;NMO:Nickel Molybdate;CS:Chitosan;GQDs:Graphene Quantum Dots;GCEox:Oxidized Glassy Carbon Electrode;CNT:Carbon Nanotube;SWV:Square Wave Voltammetry;CV:Cyclic voltammetry;DPV:Differential Pulse Voltammetry;SWASV:Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry;AgNPs: Silver Nanoparticles;fCNT: Functionalized Carbon Nanotube;PGE: Pyrolytic Graphite Electrode.

3.3. Malathion detection

Prolonged exposure to malathion (MTN) has been associated with potential carcinogenic effects on humans, including the development of cause prostate cancer and nasal adenomas [112]. The pesticide can induce oxidative damage to cells when exposure is prolonged. To address this, WHO and FAO have established an acceptable daily intake (ADI) limit of 0.3 mg/kg body weight for MTN [112]. Fig. S1c shows the chemical structure of MTN, and its IUPAC name is diethyl 2-dimethoxyphosphinothioylsulfanylbutanedioate [142].

In the field of MTN sensing, most of the sensors are designed based on the principle of signal inhibition. Electrodes are modified to exhibit a high affinity towards MTN, resulting in the interference of the normal electrochemical signal due to MTN attachment on the electrode surface. Al'abri et al. synthesized a porous coordination polymer with benzene-1,2,4,5 tetracarboxylic acid (BTCA), piperazine (P), copper (Cu), and carbon paste (CP) to modify carbon paste electrode (CPE) [143]. The well-defined porosity of the porous coordination polymer provides the electrode with improved selectivity. The principle of MTN detection in this study relies on the high affinity of Cu-containing compounds towards the phosphate group present in MTN. In the presence of MTN, an intermediate complex is formed on the electrode surface through a coordination effect. This interaction between MTN and the modified electrode leads to a reduction in the anodic peak current during the redox reaction between Cu2+ and the electrode. As the concentration of MTN increases, the peak current decreases accordingly. Soomro et al. developed another sensor for the detection of MTN using a signal suppression approach based on the redox reaction of CuO [144]. In this study, an amino acid, specifically glycine, was employed to enhance the biocompatibility and growth control of CuO nanostructures on the electrode surface. Among various amino acids tested, glycine demonstrated superior performance in terms of forming highly crystalline electrode surfaces and providing better control over the growth of CuO nanostructures, attributed to its smaller size. The developed sensor exhibited remarkable detection capabilities for MTN, even in the presence of commonly coexisting pesticides such as lindane, carbendazim, and trichlorfon. It demonstrated a high sensitivity of 1089.45 μAnM−1, an ultralow low detection limit of 0.1 nM and a concentration range of 1–12 nM. In a review by Huo et al., a range of electrochemical sensors based on 3D graphene was explored [145]. Among these sensors, a CuO-3D graphene nanocomposite was specifically highlighted for its selective detection of MTN down to 0.01 nM through the inhibition of the redox reaction as shown in Fig. 7. Similar to the previous approach, the presence of MTN hindered the redox reaction of CuO due to the strong affinity between CuO and MTN, resulting in a decrease in the electrochemical.

Fig. 7.

Preparation of the CuO-3D Graphene/GC electrode for MTN detection. Reproduced from Ref. [52] with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2018.

Bolat & Abaci introduced a novel approach for the detection of MTN using a direct electrochemical signal instead of signal suppression, which is commonly employed by other electrochemical sensors [146]. The incorporation of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) in the sensor design was based on their well-known high electrocatalytic activity, large surface area, and biocompatibility. To enhance the electrical conductivity, an ionic liquid (IL) was combined with the AuNPs, while chitosan (CS) was utilized for its excellent film-forming ability. The sensor was constructed on a pencil graphite electrode (PGE) platform, resulting in a highly selective device capable of detecting MTN even in the company of a 1000 times greater concentration of commonly occurring ions. The sensor exhibited a low detection limit of 0.68 nM for MTN. Notably, two distinct linear ranges (0.89–5.94 nM and 5.94–44.6 nM) were observed for low and high MTN concentrations, respectively. However, due to the strong bond between AuNPs and the sulfur atom in MTN, the regeneration of the sensor surface for reuse was found to be nearly impossible. Additionally, a significant drawback of the aforementioned MTN sensing device was its lack of repeatability.

To address these limitations, Kushwaha et al. developed a chitosan-grafted polyaniline electrode (CS-g-PANI) that exhibited exceptional repeatability in sensing performance, with only a 2% decrease observed after 50 cycles of use [147]. The electrode fabrication involved grafting polyaniline with CS particles, resulting in an expanded porous hybrid matrix with free functional groups. The porous and biocompatible nature of CS enhanced the adsorption capacity of the sensor for MTN detection. The sensing principle relied on the observation of a linear potential variation within the concentration range of 2–62.5 μM, attributed to partial electron transfer from the sulfur atom of MTN to the CS-g-PANI electrode. The LOD for the sensor was determined to be 3.8 μM. Table 4 covers typical features of some of the newly developed MTN electrochemical sensors.

Table 4.

Summary of the activities of different sensors for MTN detection.

| Electrode Materials | Technique | Sensitivity | Linearity | LOD | Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuO-NPs/3DGR/GCE | CV & DPV | – | 0.03–1.5 nM | 0.01 nM | Water | [148] |

| AuNps-CS-IL/PGE | SWV | – | 0.89–5.94 nM 5.94–44.6 nM |

0.68 nM | Tomato and apple | [146] |

| BTCA-P-Cu-CP/CPE | CA | 5.7 μA.nMcm−1 | 0.6–24 nM | 0.17 nM | Spiked vegetable extracts | [143] |

| Gly-CuO/GCE | DPV | 1089.45 μAnM−1 | 1–12 nM | 0.1 nM | – | [144] |

| CHIT-g-PANI | Potentiometry | 2.26 mVμM−1cm−2 | 2.0–62.5 μM | 3.8 μM | Tomato juice | [147] |

| Nafion/CuONWs–SWCNTs/GCE | CV & DPV | 2.1 × 1011 μA cm−2M | – | 0.3 nM | Spiked liquid garlic | [149] |

| AgNPs/fCNT/PGE | Amperometry | 0.030 mA.Lμmol−1 | 1–30 μM | 0.89 μM | Tap water, orange juice, and apple fruit | [101] |

| GO/PEDOT: PSS-polypyrrole/AuNPs | IS | – | – | 0.1 nM | Tap water | [150] |

| PA6/PPy/CRGO/FTO | DPV | – | 1.7–67.1 μM | 2.7 × 10−3 μM | Tap water and river water | [151] |

| CeO2–CuO/GCE | DPV | – | 1.0 × 10−5–0.1 μM | 3.3 × 10−6 μM | – | [152] |

| CuO NWs-SWCNTs | DPV | 628.71 μA cm−2.ppb−1 | 0–0.4 ppb | 0.3 nM | Liquid garlic | [149] |

CuO-NPs:Copper Oxide Nanoparticles;3DGR:Three-Dimensional Graphene;GCE:Glassy Carbon Electrode;AuNPs-Au Nanoparticles;CS:Chitosan;IL:Ionic Liquid;PGE:Pencil Graphite Electrode;BTCA:benzene- 1,2,4,5-tetracarboxylic acid;P:Piperazine;CP:Carbon Paste;CPE:Carbon Paste Electrode;Gly:Glycine;CS-g-PANI:Chitosan grafted Polyaniline;CV:Cyclic Voltammetry;DPV:Differential Pulse Voltammetry;SWV:Square-Wave Voltammetry;CA:Chronoamperometry;GO: Graphene Oxide;PEDOT: PSS: Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)poly(styrenesulfonate);IS: Impedance Spectroscopy;PA6: Polyamide 6; PPy: Polypyrrole:CRGO: Chemically Reduced Graphene Oxide;FTO: Fluorine Tin Oxide;CuO NWs: Copper Oxide Nanowires;SWCNTs: Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes.

3.4. Methyl parathion detection

Methyl Parathion (MP) is a toxic OPP and should be handled only by professionals. Exposure of MP through any route of human body can severely affect the central nervous system. Maximum ADI limit of MP set by FAO is 0.003 mg per kg body weight [153]. The IUPAC name of methyl parathion is O,O-Dimethyl O-4-nitrophenyl phosphorothioate [154]. The chemical structure of MP is given as Fig. S1d.

Ravi et al. developed a MnO2 modified Pt electrochemical sensor which can detect 4-nitrophenyl phosphate (4-NPP) based OPPs such as methyl parathion, parathion, fenitrothion, methyl paraoxon and paraoxon in aqueous medium selectively [155]. The MnO2/Pt electrode exhibited highly rough surface morphology due to the deposition MnO2, ensuring a significantly increased surface area. This rough surface facilitated efficient electrocatalysis by the electrode. The modified Pt electrode was employed in the detection of 4-NPP using CV technique. The results showed a linear concentration range of 100 nM–900 nM along with a LOD of 10 nM. The sensor demonstrated a favorable recovery rate of above 90%. However, prolonged exposure of the electrode to 4-NPP led to the leaching of MnO2 deposit. Additionally, interference in electrode response was observed in the presence of other nitro-group containing aromatic compounds, such as nitrobenzene and 4-nitrophenyl. However, the selectivity of this sensor could be improved using MnO2 composite with other metals.

In another work, a nonenzymatic electrochemical sensor was developed based on CuO–TiO2 nanocomposite modified GCE for the selective detection of MP pesticide in groundwater utilizing both CV and DPV methods [156]. Notably, the CuO–TiO2/GC electrode exhibited remarkable selectivity in detecting MP, even in presence of interfering aromatic species containing nitro-group, such as 4-nitrobenzaldehyde and nitrobenzene, as well as other pesticides and inorganic species. The presence of CuO and TiO2 materials in the nanocomposite showed a synergistic effect, rendering the GCE highly active and sensitive to MP. The large surface area of the CuO–TiO2 nanocomposite facilitated the absorption of MP due to its high affinity, resulting in hindered electron transfer in the redox reactions of Cu. Consequently, the current density decreased with increasing concentration of MP from 0 to 100 ppb, as illustrated in Fig. 8. The sensor demonstrated excellent selectivity and sensitivity, with a LOD of 1.21 ppb and a dynamic detection range of 0 ppb–2000 ppb.

Fig. 8.

Detection of MP using a CuO–TiO2/GC electrode employing cyclic voltammetric current signal inhibition method [156].

In recent years, graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and other carbon derivatives have gained popularity in the development of electrochemical sensors due to their fast electron transfer capability and wide surface area [67]. Graphene Oxide (GO) stands out due to its enormous surface area, enabling excellent redox current signals and maximum adsorption [157]. Its reduced form, containing numerous functional groups, facilitates the deposition of various electrode materials. Porous graphene oxide, incorporating Cu2+ and Ni2+ ions, has also been developed to detect OPPs in gaseous samples [158]. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), another promising carbon-based one-dimensional nanomaterial, have been extensively studied for their excellent electrical conductivity, chemical stability, and high surface area, making them ideal candidates for electrochemical sensors [67]. A highly selective (sensitivity = 1846.9 μA μM−1) electrochemical sensor using Zn(II) phthalocyanines (ZnPc), boron dipyromethene (BODIPY) and Single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) was established by Köksoy et al. for the detection of MP, spinosad, chlorpyrifos and deltamethrin [159]. In DPV technique, the ZnPc-BODIPY-SWCNT/GC electrode exhibited enhanced selectivity towards MP. Another electrochemical sensor, developed by Manavalan et al., employed a 3D ZnO nanostars (ZnONSt) and graphene oxide (GO) nanocomposite to modify a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) for the detection of MP [160]. ZnONSt-GO/SPCE displayed a superior current response (−17.696 μA) than that of bare SPCE (−0.78 μA), ZnONSt/SPCE (−4.766 μA) and GO/SPCE (−8.269 μA) at a scan rate of 50 mVs-1 owing to the synergistic effect between ZnONSt and GO. GO offered a high specific surface area and conductivity, while ZnO demonstrated excellent catalytic ability as well as biocompatibility. Consequently, the ZnONSt-GO/SPCE exhibited outstanding electrocatalytic performance in the detection of MP with an LOD and sensitivity of 1.24 nM and 16.5 μA μM−1, respectively.

Nickel disulfide (NiS2) is a great earth-abundant compound which is known to have excellent electrical conductivity. A non-enzymatic detection method was developed using curcumin nanoparticles which was deposited on NiS2 modified reduced graphene oxide [161]. This nanohybrid was further immobilized on a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE), enabling simultaneous detection of MP and 4-nitrophenol with two distinct reduction peaks at −0.9 V and −0.7 V vs. pseudo Ag/AgCl, respectively. The sensor was able to detect MP in the concentration range of 0.25–80 μM with an LOD of 8.7 nM. However, the sensitivity of the proposed sensor was observed to decrease from 7.165 to 2.796 μA μM−1 when the concentration of MP was above 5 μM. To address the selective detection of MP even in the presence of 4-nitrophenol, Xiaoqian Hou et al. proposed an electrochemical sensor that can detect MP with high selectivity in the concentration range of 0.005–30 μM with a detection limit of 0.001 μM [162]. In this technique, they used host-guest technology to selectively detect MP. Hydroxylatopillar [5]arene (HCP5) was employed as a host molecule, which was attached to Au NPs possessing high catalytic activity and biocompatibility (see Fig. 9). This combination was then integrated onto electrochemically reduced graphene oxide (ERGO), resulting in the formation of a sensor with high adsorption performance and high conductivity.

Fig. 9.

Graphical representation of the preparation process of HCP5@AuNPs-ERGO electrode implementing host-guest technology to selectively detect MP using DPV method. Used with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry, from reference [162], copyright 2019; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Redox behaviour of MP was investigated using the HCP5@AuNPs-ERGO/GCE sensor by DPV method. The study revealed that nitro-group (NO2−) present in MP undergoes irreversible reaction with four electron transfer, resulting in the formation of a hydroxylamine-group (NHOH−), which subsequently undergoes reversible redox reaction through two electron transfer with nitroso-group (NO−), as shown in Scheme 5 [162]. By performing DPV measurement of the reduction peak corresponding to reduction of hydroxylamine-group to nitroso-group, the sensor could detect MP quantitatively.

Scheme 5.

Chemical reaction of MP occurring on HCP5@AuNPs-ERGO/GC electrode [162].

Ulloa et al. developed an MP sensor using a fully roll-to-roll manufacturing process in which materials were processed in a continuous roll, rather than in individual sheets, as shown in Fig. 10 [163]. A flexible, screen-printed silver electrode (Ag SPE) was utilized as the basis for the sensor, which was further modified by incorporating a graphene nanoplatelet (GNP) coating and a zirconia (ZrO2) coating. This unique combination of a metal oxide and a two-dimensional material conferred advantageous electrocatalytic activity specifically tailored for the detection of nitroaromatic OPPs (NOPPs). The non-enzymatic sensor allowed for swift response times of just 10 min and simplified detection of NOPPs using SWV method. The proposed platform exhibited a detection limit of as low as 1 μM (0.2 ppm). Table 5 summarizes several non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors developed for the detection of MP.

Fig. 10.

Schematic diagram showing roll-to-roll manufacturing process of an MP sensor. Adapted with permission from reference [163]. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

Table 5.

Activity summary of non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors for detecting MP.

| Electrode Materials | Technique Used | Sensitivity | Linearity | LOD | Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnO2/Pt | CV | 11.68 μA μM−1 | 100 nM–900 nM | 10 nM | Vegetables, tomato, beans and drinking water | [155] |

| CuO–TiO2/GCE | CV & DPV | – | 0 ppb–2000 ppb | 1.21 ppb | Groundwater | [156] |

| SWCNT-BODIPY-ZnPc/GCE | DPV & CV | 1846.9 μA μM−1 | 2.45 nM- 4 × 10−8 nM | 1.49 nM | Peach and orange Juice | [160] |

| ZnONSt-GO/SPCE | DPV & Amperometry | 16.5 μA μM−1 | 0.03 μM–670 μM | 1.24 nM | Apple, broccoli flower, and collard greens | [158] |

| NiS2-rGO/CMNPs//GCE | CV & DPV | 7.165 μA μM−1 (0.25–5 μM) 2.796 μA μM−1 (5–80 μM) |

0.25 μM–80 μM | 8.7 nM | Tomato, apple juices and spiked river water | [161] |

| HCP5@AuNPs-ERGO/GCE | DPV | – | 0.005 μM–30 μM | 0.001 μM | Actual water samples | [162] |

| PAM-Cl/GCE | CV | – | 0.215 μM | Corn | [14] | |

| PAM-Cl/CuO/ITO | CV & DPV | 0.01–0.16 μM | 6.7 nM | Cabbage and spinach | [100] | |

| CuO–ZrO2-MFs/FTO | SWV | 0.002–200 ppb | 0.16 ppb | Tap water | [164] | |

| Hal-MWCNTs/GCE | DPV | – | 0.5–11 μM | 0.034 μM | Kiwifruit and Romaine | [165] |

| GNPs/ZrO2/Ag SPE | SWV | – | 1–20 μM | 1 μM | – | [163] |

GCE:Glassy Carbon Electrode;SWCNT:Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube;BODIPY:Boron Dipyromethene;ZnPc:Zn (II) phthalocyanines;ZnONSt:ZnO Nanostars;GO:Graphene Oxide;SPCE:Screen Printed Carbon Electrode;rGO:Reduced Graphene Oxide;CMNPs:Curcumin Nano Particles;HCP5:Hydroxylatopillar[5]arene;AuNPs:Au Nanoparticles;ERGO:Electrochemically Reduced Graphene Oxide;CV:Cyclic Voltammetry;DPV:Differential Pulse Voltammetry;Cuo:Copper Oxide;ZrO2:Zirconium Oxide;MFs:Microfibers;SWV:Square Wave Voltammetry;FTO:Fluorine Tin Oxide Electrode;Hal: Halloysite;MWCNTs: Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes;GNPs: Graphene Nanoplatelet;Ag SPE: Silver Screen Printed Electrode.

3.5. Fenthion detection

Fenthion (FEN) can persist in environment for 4–6 weeks [94]. However, it undergoes degradation through aerobic microbial metabolism, exhibiting a half-life of less than one day in aerobic soil [166]. FEN finds utility in managing insect pests across various agricultural, commercial, and domestic settings, as well as for tackling external parasites in cattle. Furthermore, it is employed to regulate pest bird populations in and around structures [167]. It is also important to note that FEN exhibits significant toxicity towards freshwater, estuarine, and marine invertebrates, while also displaying moderate to high toxicity levels for fish species [168]. FAO and WHO set the maximum ADI limit of FEN as 0.007 mg/kg body weight [169]. The IUPAC chemical name of FEN is dimethoxy-(3-methyl-4-methylsulfanylphenoxy)-sulfanylidene-λ5-phosphane [166]. Fig. S1e displays the chemical structure of FEN.

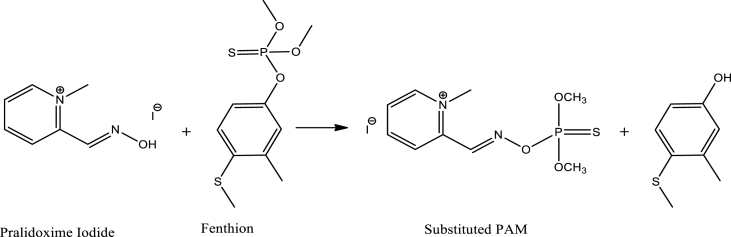

FEN is classified as a redox-inactive OPP [14,94], posing challenges in its electrochemical detection. Oximes, such as pralidoxime (PAM), are known for their strong nucleophilic properties. PAM, an antidote for OPP poisoning, forms bond with OPP reversibly. It exhibits a stronger binding affinity to OPP than AChE [14]. Consequently, when individuals affected by OPP poisoning consume PAM, it displaces the OPP molecules, thereby freeing and reactivating AChE. To address the detection of FEN, Dong et al. developed a sensor utilizing Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) to modify a GCE, which was subsequently coated with PAM [50]. The sensor employed a current signal inhibition strategy. GQDs were immobilized on the GCE surface using chitosan as a binder. GQDs, characterized as zero-dimensional materials with diameters less than 10 nm and fewer than 10 graphene layers, possess exceptional sensing properties [170]. Furthermore, GQDs contain negatively charged carboxyl group that facilitate adsorption of positively charged nitrogen-containing PAM molecules onto their surface [171]. The extensive surface area possessed by GQDs enhances the active surface area of the GCE, allowing for the accommodation of numerous PAM molecules. Additionally, GQDs improve the conductivity of the GCE surface. The oxidation current signal from PAM occurs through a two-electron transfer mechanism. However, the current from PAM oxidation decreased after it underwent nucleophilic substitution reaction with FEN, as shown in Scheme 6 [171]. The sensor exhibited an incredibly low detection limit of 6.8 × 10−12 M and a wide linear concentration range of 1 × 10−11 to 5 × 10−7 M.

Scheme 6.

Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction of PAM-I with FEN [50].

Zheng et al. developed another PAM-based FEN sensor utilizing the current signal inhibition method, achieving an LOD of 0.100 μM [14]. A more sensitive PAM-based sensor was designed by Tunesi et al. which could detect FEN with an LOD of 2.5 nM [100]. This sensor employed a template-guided growth of CuO on an Indium–Tin Oxide (ITO) electrode, enabling uniform deposition of CuO NPs and subsequent immobilization of PAM on the extensive surface area of the CuO NPs. The sensor employed the current signal inhibition method for FEN detection. In the pursuit of enhanced selectivity, a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) based electrode approach has been explored. MIPs can mimic biological receptors, offering confirmed selectivity. Youssra et al. developed an MIP-based FEN sensor with an LOD of 0.05 mg/kg [172]. The fabrication of the electrode involved mixing AuNPs with 2-aminothiophenol (ATP), followed by immobilization of this mixture on a screen-printed gold electrode (Au-SPE) through Au–S bond formation. FEN was then imprinted on the prepared AuNPs-ATP/Au-SPE electrode as a template. Subsequently, ATP was electropolymerized on the electrode surface using CV by scanning in the potential range of −0.2 to 0.6 V for 10 cycles at a scan rate of 0.1 Vs-1. The MIP-based electrode was employed for the detection of FEN in olive oil samples using CV and differential DPV methods, where the current signal increased with increasing FEN concentration in the samples.

Smarzewska et al. developed two highly sensitive FEN sensors [173]. One sensor utilized a GCE modified with reduced graphene oxide (rGO), a cost-efficient and easily synthesized material that exhibits similar properties to graphene [[174], [175], [176]]. This sensor achieved an LOD of 7.6 nM. In another sensor, Smarzewska et al. used a renewable silver amalgam film electrode (Hg[Ag]) to detect FEN. Though mercury is toxic to environment, the preparation of Hg [Ag] film electrode requires less than 10 μL of the amalgam, yet showing similar high sensitivity to that of hanging mercury drop electrode [[177], [178], [179]]. It is important to note that the hanging mercury drop electrode produces more toxic waste, posing environmental concerns.

Asif et al. prepared a sensor using C4N, which could detect several toxic pesticides including FEN. C4N is a two-dimensional graphene like material with numerous porosities. Pyrazine is the repeating unit of C4N thin sheet. Nitrogen in pyrazine unit gives C4N polymer high intramolecular charge transfer rate which facilitates attachment of foreign molecules such as OPPs to the layer [7,180]. Table 6 provides an overview of recently developed electrochemical FEN sensors.

Table 6.

Activity summary of non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors for detecting FEN.

| Electrode Materials | Technique Used | Linearity | LOD | Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAM/GQDs/GCE | DPV | 1 × 10−11 to 5 × 10−7 M | 6.8 × 10−12 M | Water and soil | [50] |

| PAM-Cl/GCE | CV & DPV | - | 0.100 μM | Vegetables | [14] |

| AuNPs-ATP/Au-SPE | DPV | 0.01–17.3 μg/mL. | 0.05 mg/kg | Olive Oils | [172] |

| PAM-Cl/CuO/ITO | CV & DPV | 0.01–0.16 μM | 2.5 × 10−9 M | Cabbage and spinach | [100] |

| rGO/GCE | SWSV | 1 × 10−7 to 2.5 × 10−5 M | 7.6 × 10−9 M | Spiked tap and river water, and apple juice samples | [173] |

| Hg(Ag)Film Electrode | SWSV | 1 × 10−6 to 2 × 10−5 M | 1.3 × 10−7 M | Spiked tap and river water, and apple juice samples | [173] |

| C4N | DFT | - | - | - | [7] |

GQDs:Graphene Quantum Dots; AuNPs:Gold Nanoparticles; ATP:2-Aminothiophenol; AuSPE:Screen Printed Gold Electrode; ITO:Indium tin oxide; rGO:Reduced Graphene Oxide; Hg(Ag):Silver Amalgam; SWSV:Squarewave Stripping Voltammetry; DFT:Density Functional Theory.

4. Challenges and future perspectives

The selection of electrode materials remains the most challenging aspect when designing experiments for the development of electrochemical sensors. Although we have discussed several electrode materials that exhibit synergistic behaviour and provide improved electrical signals at lower potentials, the process of depositing various nanocomposites and nanoparticles onto the electrode surface is currently random, unpredictable, and difficult to control. This lack of control hinders the reproducibility of electrochemical sensors. However, the template-assisted growth method of nanoparticles, as described in this paper, offers a potential solution by allowing the application of different electrode materials to prepare confirmed and reproducible sensors. Future experiments can explore the combination of these electrode materials, focusing on those with high electrical conductivity and sensitivity. While most electrochemical sensing is based on redox reactions occurring at the electrode surface, there are cases where the analyte of interest is a redox-inactive substance. In such instances, sensing can be achieved through the inhibition of current signal strategy stemming from the adsorption of the analyte on the surface of the electrode. To enable selective adsorption of specific analytes, the design of electrodes using MIP can be employed. This approach involves the fabrication of a film on the electrode surface, prepared using the analyte as a template. However, it is important to note that adsorption-based sensing methods require the electrode to be prepared before each measurement, posing a limitation. Future research should focus on developing easier and simpler methods to address this limitation and enhance the functionality of adsorption-based sensors. Designing electrochemical sensors for OPP detection or other toxic substances using their respective antidotes represents an efficient approach. Antidotes are chemically active compounds specifically designed to interact with and neutralize toxic substances. However, there have been limited reports on antidote-based electrochemical sensors, highlighting the potential for further exploration in this area. To increase the current signal, highly conductive electrocatalysts with large surface areas, such as CNTs, GO, or graphene, can be utilized. The integration of nanoarrays enables selective detection of specific OPP even in the presence of other OPP compounds within a mixture. Incorporation of carbonaceous nanofluid into the sensing components can functionalize electrode as signal amplifiers to quantify analytes at lower concentration [181,182].

Despite the significant advancements in electrochemical sensors, nanostructured sensors face a significant challenge in terms of limited lifetime due to surface fouling caused by chemical interactions with interferences present in the reaction system or wastewater. To confront this challenge, various anti-fouling strategies have been proposed, including the spontaneous in-situ immobilization of nanoparticles, as reported by Hossain et al. [183]. Further research pertaining to anti-fouling techniques can help overcome the limitations associated with surface fouling in nanostructured electrochemical sensors.

The search for suitable electrode materials for electrochemical sensors is currently conducted somewhat randomly. While the mechanisms of various electrochemical reactions taking place at the surface of the electrode have been explored in the review, our understanding of atomic-level interactions between the surface and analytes is still inadequate. Therefore, scientific studies providing insights into atomic-level interactions and reaction mechanisms in OPP sensors are crucial for systematic investigations of suitable electrode materials. The utilization of novel liquid single-atom catalysts, where catalysts are dispersed atomically, can provide a better understanding of atomic-level catalysis of metals and matrices [184]. The area of single atom catalysis is still in its early stages but holds great potential as futuristic materials.

The successful growth of metal oxide single crystals with precise oxygen stoichiometry, metal cation charge, and crystallite size has been regarded as a significant challenge in the field. The oxygen stoichiometry plays a critical role in influencing the concentration of oxygen vacancies and the structural arrangement of metal crystals. Higher concentrations of oxygen vacancies provide more catalytic sites, thereby enhancing sensitivity and selectivity [185]. Furthermore, a higher charge state of metal cations allows for the accommodation of more oxygen vacancies, leading to an increased sensor response. Consequently, precise control over oxygen stoichiometry and metal cation charge state in metal oxides holds paramount importance for efficient electrocatalysis. Trukhanov et al. have demonstrated how enhancement of ferromagnetic properties of metal oxides by modifying hydrostatic pressure leads to redistribution of the oxygen vacancies [186]. In a different study, Lee et al. showcased the controlled generation of oxygen vacancies through appropriate beam laser spot size during pulse laser epitaxy in a high-vacuum environment [187]. Additionally, it has been reported that an increased presence of oxygen vacancies can lead to a reduction in the average crystallite size [188]. This reduction results in a higher density of grain boundaries per unit volume of the crystal, thereby providing more catalytic sites for chemical reactions and reducing the diffusion path length for charge carriers. Furthermore, irradiating metal crystals with heavy ions, such as Fe7+, has been demonstrated to decrease the crystallite size in a separate study [189].

While most studies in this field have been conducted on a laboratory scale, there is a compelling necessity to develop flexible, wearable, and portable OPP sensors for point-of-care regular and real-time monitoring to address contemporary challenges. Additionally, most inhibition-based sensors have been fabricated using the OPP adsorption principle, which results in toxic OPPs remaining attached to the sensors after use. Few studies have focused on preparing reusable sensors or have reported proper disposal procedures. Therefore, the next generation of OPP sensors should prioritize the utilization of environmentally friendly factors, such as lower toxicity, biodegradability, disposability, reusability, recyclability, waste-free operation, and overall environmental sustainability. These considerations are essential for achieving a better human life by solving health problems while minimizing the environmental impact.

5. Conclusion

In this comprehensive review, we have summarized a wide range of electrode materials and their unique analytical performances, elucidating their underlying mechanisms of action for the detection of OPPs. The focus of the review has been on the recent developments of sensitive electrochemical sensors for the detection of five commonly used OPPs: Chlorpyrifos, Diazinon, Malathion, Methyl Parathion, and Fenthion. It has been observed that most of these OPPs are redox inactive, posing a challenge for electrochemical sensing. However, recent advancements in inhibition strategies and MIP-based sensors have provided viable solutions for the detection of even electrochemically inactive substances. Furthermore, the integration of carbonaceous nanomaterials and nanoarrays has pioneered new possibilities for the development of advanced electrochemical sensors. These materials offer enhanced electrical conductivity and provide a platform for selective sensing, enabling the fabrication of next-generation sensors with improved performance. Lastly, the review has identified several potential futuristic solutions to address the existing drawbacks in sensor development. It is anticipated that these suggested solutions will contribute to the development of electrode materials that align with the principles of sustainable development goals.

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve the language and readability of the paper. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank Ministry of Education (Bangladesh) for the research grant (No PS20211727) to carry out this project.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19299.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Imran Hossain, Email: imran.che.sust@gmail.com.

Mohammad A. Hasnat, Email: mah-che@sust.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Fyles H., Madramootoo C. Key drivers of food insecurity, Emerging Technologies for Promoting Food Security. 2016:1–19. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-78242-335-5.00001-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenfeld P.E., Feng L.G.H. Pesticides, Risks of Hazardous Wastes. 2011:127–154. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4377-7842-7.00011-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang F.H.M., Lenzen M., McBratney A., Maggi F. Risk of pesticide pollution at the global scale. Nat. Geosci. 2021;14:206–210. doi: 10.1038/s41561-021-00712-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pesticides | US Geological Survey, https://www.usgs.gov/centers/ohio-kentucky-indiana-water-science-center/science/pesticides (accessed June 27, 2023).

- 5.Ippolito A., Kattwinkel M., Rasmussen J.J., Schäfer R.B., Fornaroli R., Liess M. Modeling global distribution of agricultural insecticides in surface waters. Environ. Pollut. 2015;198:54–60. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wanwimolruk S., Kanchanamayoon O., Phopin K., Prachayasittikul V. Food safety in Thailand 2: pesticide residues found in Chinese kale (Brassica oleracea), a commonly consumed vegetable in Asian countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;532:447–455. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2015.04.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asif M., Sajid H., Ayub K., Ans M., Mahmood T. A first principles study on electrochemical sensing of highly toxic pesticides by using porous C4N nanoflake. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2022;160 doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakas I., Ben Oujji N., Istamboulié G., Piletsky S., Piletska E., Ait-Addi E., Ait-Ichou I., Noguer T., Rouillon R. Molecularly imprinted polymer cartridges coupled to high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC-UV) for simple and rapid analysis of fenthion in olive oil. Talanta. 2014;125:313–318. doi: 10.1016/J.TALANTA.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miodovnik A. Prenatal exposure to industrial chemicals and pesticides and effects on neurodevelopment. Encycl., Environ. Heal. 2019:342–352. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.11008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regulation of pesticide residues on food | US EPA, https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-tolerances (accessed June 16, 2023).

- 11.Maximum residue limits (MRL) database | USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, https://www.fas.usda.gov/maximum-residue-limits-mrl-database (accessed June 16, 2023).

- 12.Čadež T., Kolić D., Šinko G., Kovarik Z. Assessment of four organophosphorus pesticides as inhibitors of human acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase. Sci. Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00953-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saghir S.A., Husain K., Ansari R.A. Patty's Toxicol. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2023. Organophosphorus pesticides; pp. 1–162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Q., Chen Y., Fan K., Wu J., Ying Y. Exploring pralidoxime chloride as a universal electrochemical probe for organophosphorus pesticides detection. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017;982:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X., Song M., Hou T., Li F. Label, Label-Free homogeneous electroanalytical platform for pesticide detection based on acetylcholinesterase-mediated DNA conformational switch integrated with rolling circle amplification. ACS Sens. 2017;2:562–568. doi: 10.1021/ACSSENSORS.7B00081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim L., Bolstad H.M. Organophosphate insecticides: neurodevelopmental effects, encycl. Environ. Health (Nagpur) 2019:785–791. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10930-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu G., Lin Y. Electrochemical sensor for organophosphate pesticides and nerve agents using zirconia nanoparticles as selective sorbents. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:5894–5901. doi: 10.1021/AC050791T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolopoulou-Stamati P., Maipas S., Kotampasi C., Stamatis P., Hens L. Chemical pesticides and human health: the urgent need for a new concept in agriculture. Front. Public Health. 2016;4:148. doi: 10.3389/FPUBH.2016.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha S.N., Kumpati R.K., Ramavath P.N., Sangaraju R., Gouda B., Chougule P. Investigation of acute organophosphate poisoning in humans based on sociodemographic and role of neurotransmitters with survival study in South India. Sci. Rep. 2022;12 doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-21054-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabarwal A., Kumar K., Singh R.P. Hazardous effects of chemical pesticides on human health-Cancer and other associated disorders. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018;63:103–114. doi: 10.1016/J.ETAP.2018.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afshari M., Poorolajal J., Assari M.J., Rezapur-Shahkolai F., Karimi-Shahanjarini A. Acute pesticide poisoning and related factors among farmers in rural Western Iran. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2018;34:764–777. doi: 10.1177/0748233718795732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bavcon M., Trebše P., Zupančič-Kralj L. Investigations of the determination and transformations of diazinon and Malathion under environmental conditions using gas chromatography coupled with a flame ionisation detector. Chemosphere. 2003;50:595–601. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akhlaghi H. Determination of diazinon in fruits from northeast of Iran using the QuEChERS sample preparation method and GC/MS, artic. Asian J. Chem. 2013;25:1727–1729. doi: 10.14233/ajchem.2013.14244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blasco C., Vazquez-Roig P., Onghena M., Masia A., Picó Y. Analysis of insecticides in honey by liquid chromatography-ion trap-mass spectrometry: comparison of different extraction procedures. J. Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218:4892–4901. doi: 10.1016/J.CHROMA.2011.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]