Abstract

This case report describes a case of severe dysphagia lusoria secondary to an aberrant right subclavian artery causing compression of the esophagus. Our 62-year-old female patient presented with severe dysphagia and underwent right carotid–subclavian bypass with uncovered thoracic endovascular aortic repair and coil embolization of the aberrant right subclavian artery. This case is unique in that an uncovered dissection stent graft was used to avoid occluding the anatomic left subclavian artery and, therefore, avoid a left carotid–subclavian bypass. This case highlights a unique anatomic variant, its surgical repair, and the long-term improvement in the patient's quality of life.

Keywords: Aberrant right subclavian artery, Bypass, Dysphagia lusoria, Thoracic endovascular aortic repair

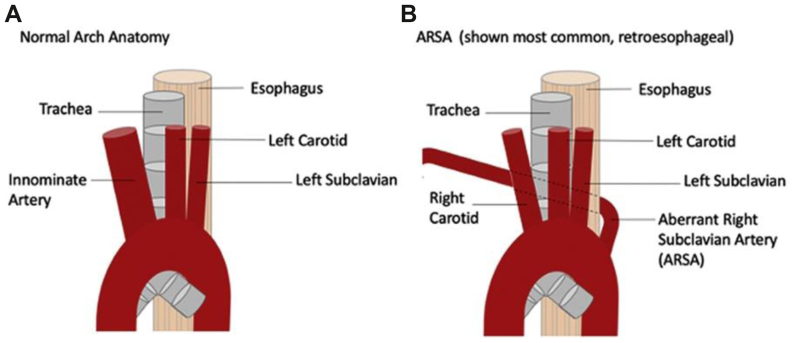

The term “dysphagia lusoria” was coined in 1761 when Bayford described a case of death from longstanding dysphagia due to emaciation.1 He described an aberrant right subclavian artery running anterior to, and causing compression of, the esophagus (Fig 1). However, dysphagia lusoria is defined as dysphagia due to compression of the esophagus from any of several congenital vascular abnormalities.3 An aberrant right subclavian artery is the most common vascular abnormality and consists of a right subclavian artery coming off the left side of the aortic arch, a double aortic arch, or a right aortic arch with a left ligamentum arteriosum (Fig 1).3 This anatomic anomaly has been reported to only cause dysphagia in 40% to 60% of patients.1 Often, symptoms will not develop until later in life when atherosclerotic changes have occurred in the aberrant vessel.3 This was the case for the patient in our case study who was 62 years old when she became symptomatic. In her case, her anatomy was a right subclavian artery coming off the descending aorta, which passed in a retropharyngeal manner, causing symptomatic compression (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Anatomic illustration showing normal arch anatomy (A) and showing aberrant right subcavian artery and its relationship to the esophagus (B).2

Fig 2.

Pre- (A) and postoperative (B) esophagrams showing compression of the esophagus from the aberrant right subclavian artery preoperatively and decreased compression (arrow) of the esophagus with the presence of the stent and Amplatzer plug postoperatively.

Case report

A 62-year-old woman was referred to the vascular surgery office for continued management of her aberrant right subclavian artery causing dysphagia. Initially, she was experiencing dysphagia due to solids only and then also liquids. Despite dietary modification, she continued to experience symptoms. She had prior imaging showing an aberrant right subclavian artery, but she had been asymptomatic for >60 years.

Computed tomography angiography was obtained because her preceding imaging study was performed years earlier and showed an aberrant origin of the right subclavian artery arising from the distal aortic arch, just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery coursing posterior to the esophagus.

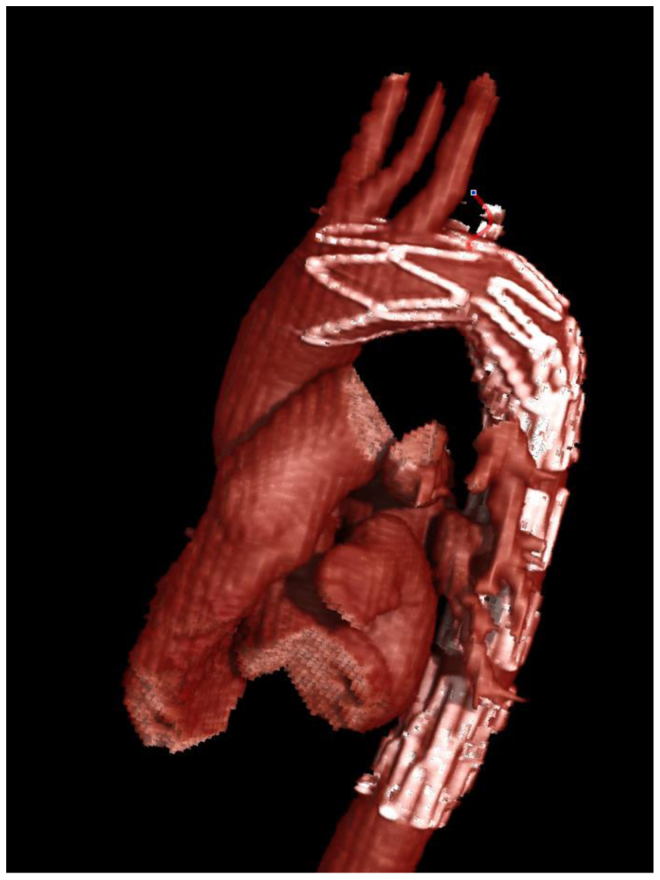

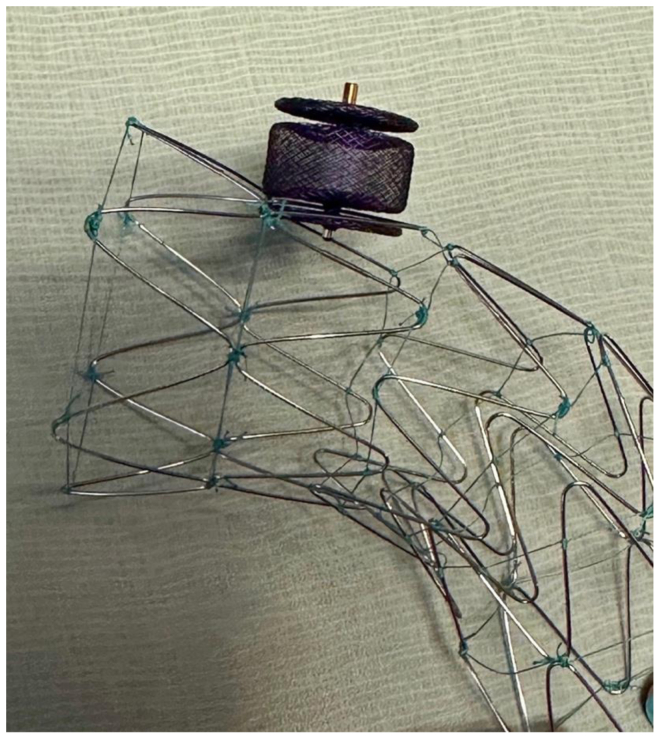

Because she remained symptomatic despite a thorough workup for her dysphagia and because her imaging study showed dysphagia lusoria, she was taken to the operating room for planned thoracic endovascular aortic repair and right carotid–subclavian bypass. The case was performed with the intention of using a bare metal aortic stent (dissection stent; Cook Medical) in the arch and subsequent plugging of the right subclavian artery at its origin and distal to the esophagus. Aortography of the aortic arch was performed, followed by supraclavicular cutdown on the right neck to control the right subclavian artery and visualize the right internal mammary artery. A 36-mm × 180-mm stent was deployed over the left and right subclavian arteries, without coverage of the carotid artery origins. According to the Ishimaru classification, the proximal landing zone was zone 2 and the distal landing zone was zone 5. No dilation of the stent was performed after deployment. The Cook dissection stent was oversized 10% from the size of the aorta to ensure a good position but not cause undo radial force or outward force on the normal aorta. The right subclavian artery was then accessed, and a 7F Brite tip sheath (Cordis) was inserted. A 16-mm Amplatzer plug was then deployed at the origin of the right subclavian artery. The Amplatzer plug consists of three disks, two thin outer disks, and a thicker middle disk. The stent graft was interlinked between the outermost disk and middle disk (Figs 3 and 4). Care was taken to ensure the plug was extremely proximal on the takeoff of the right subclavian artery, ensuring that the esophagus did not continue to experience arterial pressure and pulse action. The sheath was removed, and a large clip was placed on the right subclavian artery proximal to the right internal mammary artery and vertebral arteries. A carotid–subclavian bypass was performed with a 6-mm polytetrafluoroethylene graft.

Fig 3.

Three-dimensional rendering of thoracic aorta with stent and Amplatzer plug occluding the aberrant right subclavian artery.

Fig 4.

Photograph of the uncovered stent and 18-mm Amplatzer plug.

The patient returned 1 month postoperatively, with computed tomography angiography showing no flow in the proximal portion of the right subclavian artery. The patient's symptoms had improved significantly over the first few months. A repeat upper gastrointestinal series showed slightly less compression of the esophagus (Fig 2). Before surgery, we discussed with the patient that if she did not have a good clinical response, we would perform staged robotic ligation of the aberrant subclavian. However, she responded well, and a second procedure was not required. On further follow-up at 1 year postoperatively, she continued to remain symptom free and had no further episodes of dysphagia.

Methods

Under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, a single case report is an activity to develop information to be shared for medical and/or educational purposes. Therefore, the use of protected health information to report a single case does not require institutional review board review for Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 purposes. The patient provided written informed consent for the report of her case details and imaging studies, with the understanding that no photographs or images would contain any personal information or defining features.

Discussion

Dysphagia lusoria is a congenital abnormality caused by compression of an aberrant origin of the right subclavian artery on the esophagus. It is an uncommon abnormality that usually leads to difficulty swallowing. Most patients present with this condition later in life. This is thought to result from the compliance of vessels in younger adults and children and that vessels become more rigid and aneurysmal later in life, causing compression on the esophagus.4 In most cases, the aberrant right subclavian artery courses posteriorly to the esophagus and can be associated with a Kommerell diverticulum (not present in our patient).2,5 Again, the incidence of an anomalous right subclavian artery is quite rare and has been reported to be ∼0.4% to 1.8% in the general population. Therefore, the surgical indications have not been well defined.

Most patients can be managed with dietary modification and instructions to chew well and eat slower. This is an effective management strategy, provided that patients are able to maintain their weight and good nutritional status. Surgical intervention becomes necessary for patients who show no improvement with these dietary and eating modifications and those who are not amenable to these conservative management techniques.1

Surgical management of this condition was first reported in the mid-1900s as a left posterolateral thoracotomy, followed by division of the ligamentum arteriosum and, subsequently, either ligation or reimplantation of the aberrant vessel.1 However, ligation results in extremity ischemia and, sometimes, steal syndrome. Historically, surgical repair evolved into transecting the aberrant subclavian artery at its origin with transposition to the ascending aorta through a median sternotomy or lateral thoracotomy.4

With the evolution of endovascular surgery, surgeons are now able to manage most patients with a minimally invasive approach. This includes the use of covered or uncovered stents and ligation of the aberrant subclavian artery with reimplantation via a right supraclavicular incision. This surgical intervention is less morbid and allows for faster recovery. In our patient, we were able to place an uncovered stent, which allowed us to not cover the left subclavian artery, given its very close takeoff to the right subclavian artery. This was followed by coil embolization of the right subclavian artery, proximally and then the use of polytetrafluoroethylene via a small supraclavicular incision to create a right carotid–subclavian bypass. The decision was made to deploy a Cook Medical aortic dissection stent to avoid migration of the Amplatzer plug because without the aid of the aortic stent, it would have been very difficult to land the plug right at the origin of the aberrant right subclavian artery. In addition, we were able to link the plug to the aortic stent, ensuring no further migration. The Amplatzer plug itself was also oversized 2 mm past the origin of the aberrant right subclavian artery to avoid any migration.

This novel method has not been previously described. The advance is that it allowed us to avoid a two-staged procedure with a more traditional and well-described technique of using a covered stent graft. Also, the very close proximity of the right and left subclavian arteries would have mandated a proximal position of the stent graft at the level of the left common carotid artery and bilateral carotid–subclavian bypasses. We used an uncovered Cook Medical aortic dissection stent to secure the 16-mm Amplatzer plug exactly at the origin of aberrant right subclavian artery (Figs 3 and 4). The uncovered stent allowed us to aggressively move the plug all the way to the vessel origin at the takeoff of the aorta without fear of misdeploying the plug too far into the aorta. Accurately deploying the plug exactly at the origin was important because if the plug had been placed 1 or 2 cm more distally, it would have occluded the vessel but likely would have continued to propagate aortic pulsation on the esophagus and not alleviated her symptoms. Another interesting and somewhat unanticipated benefit of this technique was that the first disk of the Amplatzer plug linked into the uncovered aortic stent.

Conclusions

The present case is unique in that the patient underwent right carotid–subclavian bypass with uncovered thoracic endovascular aortic repair owing to proximity of the anatomic left subclavian artery. This case highlights a unique anatomic variant, its successful surgical repair, and the long-term improvement in the patient's quality of life.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the Journal policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bennett A.L., Cock C., Heddle R., Morcom R.K. Dysphagia lusoria: a late onset presentation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2433–2436. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i15.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bath J., D’Oria M., Rogers R.T., et al. Contemporary outcomes after treatment of aberrant subclavian artery and Kommerell’s diverticulum. J Vasc Surg. 2023;77:1339–1348.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2023.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch K.L. 2022. Dysphasia lusoria. In Merck manal professional version. Merck & Co., Inc.https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/esophageal-and-swallowing-disorders/dysphagia-lusoria Retrieved July. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feezor R.J., Lee W.A. Dysphagia lusoria. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:581. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed Z., Udongwo N., Albustani S., et al. Dysphagia lusoria: a little known cause of chest pain. Cureus. 2021;13 doi: 10.7759/cureus.20085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]