Abstract

Lower limb venous obstruction secondary to a lipoma is a rare occurrence. Patients with these benign soft tissue tumors can be asymptomatic, or may experience symptoms of pain, parasthesia, paralysis and swelling secondary to compression on adjacent neurovascular structures. Duplex ultrasound examination is the first-line investigation, but has its limitations. We report on a case of venous obstruction syndrome misdiagnosed as chronic venous insufficiency on duplex ultrasound examination, from a deep-seated giant lipoma compressing on the common femoral and distal external iliac vein in a patient with Dercum's disease.

Keywords: Lipoma, Adiposis Dolorosa, Venous Insufficiency, Femoral Vein Occlusion, Vascular Surgery

Soft tissue lipomas are common benign mesenchymal tumors, usually with diameters of ≤3 cm, with less common occurrences of giant lipomas >5 cm.1 Patients are usually in their 50s or 60s, and approximately 5% have multiple masses.2 Superficial lipomas of subcutaneous tissues are a clinical diagnoses; however, deep lipomas are commonly diagnosed on radiological imaging.2 The former are commonly found in the posterior trunk, neck, and proximal extremities, and the latter occur more in the extremities.2 Patients with deep lipomas may experience painless swelling; however, may also have symptoms of pain, parasthesia, or paralysis secondary to local pressure on adjacent nerves.3

A condition related to recurrent lipomas is Dercum's disease, alternatively known as adiposis dolorosa.4 A rare disorder, with a predominance in adult women and associated with obesity, Dercum's disease is characterized by pronounced pain in adipose tissue.4,5 However, occurrences of painless lipomas have also been described.6 The majority of these lipomas occur in the buttocks and thighs, and may be difficult to palpate.4 The disease is also associated with psychiatric manifestations of sleep disturbance, depression, emotional instability, cognitive impairment, and dementia.4

We present a unique case in a patient with Dercum’s disease, treated for a deep-seated femoral sheath lipoma, causing venous obstruction from compression of the common femoral vein (CFV). Consent was obtained from the patient for publication.

Case Report

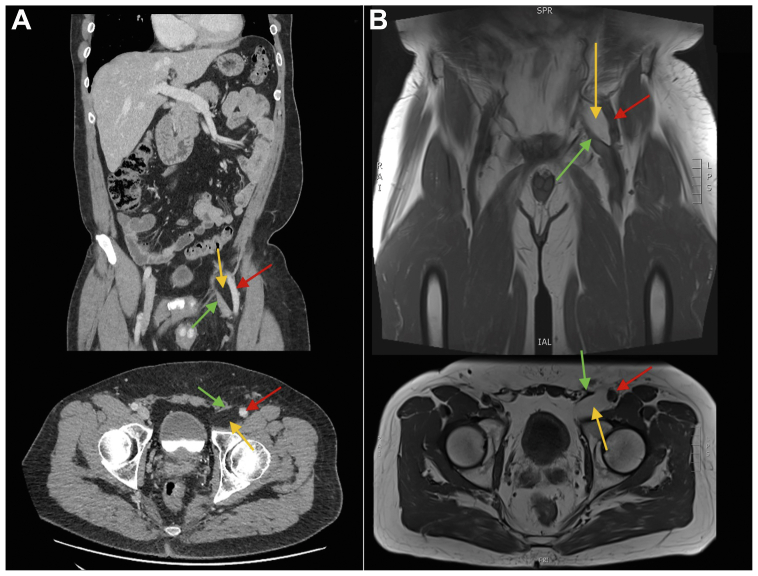

A 60-year-old man with Dercum's disease was referred by his general practitioner to a private vascular clinic for painless left lower limb edema ongoing for 2 years, involving the foot up to the lower thigh, with minimal relief from leg elevation or a trial of compression stockings. Examination was negative for varicose veins, overlying skin changes, and ulceration. His medical history was significant for hypercholesterolemia and previous lipomas, and he had an active lifestyle. A venous duplex ultrasound (DUSS) examination was organized, which demonstrated incompetent medial calf perforators, and a poorly visualized 20 cm segment of the great saphenous vein (GSV) from the level of the knee downward (Fig 1). The GSV was competent at the saphenofemoral junction and no thigh perforators or varicose veins were identified to suggest venous reflux. No other lesions were identified. The impression was chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) secondary to GSV aplasia. However, given inconsistencies in radiological findings and our patient's long clinical history of painless swelling, further investigations were undertaken with lymphoscintigraphy and computed tomography (CT) scan. The former was unremarkable, however a CT venogram found a 27 × 39 × 57 mm fat-containing lesion in the femoral canal compressing the femoral vein (Fig 2, A), resulting in an incomplete occlusion. magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) found a well-defined thin-walled homogenous lipomatous lesion, with mass effect to the distal external iliac and CFV (Fig 2, B). Owing to suspicion for potential malignancy, the case was discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting with radiologists and oncologists, with the conclusion made for surgical excision performed by a vascular surgeon.

Fig 1.

Ultrasound images of left lower limb. Spectral doppler of the common femoral vein (CFV) (A) and distal femoral vein (DFV) (B) are shown. Biphasic waveforms are demonstrated with respiratory phasic changes. Valsalva maneuvers are not routinely performed. B-mode images of the proximal (C), mid (D), and distal (E) demonstrate possible segmental aplasia of mid great saphenous vein (GSV).

Fig 2.

Computed tomography (CT) venogram (A) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (B) demonstrating radiological features of the lipomatous lesion. Red arrows point to the common femoral artery, green arrows to the common femoral vein (CFV) and yellow arrows to the lipoma.

The femoral canal was accessed through an oblique incision in the femoral region, exposing the femoral triangle and retroperitoneal space from below without dividing the inguinal ligament. The lipoma was identified between the common femoral artery and CFV (Fig 3). The lipoma was tethered to the CFV, resulting in two small longitudinal tears despite careful dissection. Profunda clamps were used for temporary hemostasis, and the tears were repaired primarily with continuous sutures. Surgicel Fibrillar Absorbable Hemostat was placed around the repaired CFV and a Blake drain was placed before wound closure, with simple dressings placed over the wound. No lymphatic complications were encountered and no lymphostasis was required. The patient was placed on TED compression stockings postoperatively, with prophylactic dosing of heparin (5000 U twice daily) given. He had an uneventful recovery and was discharged home on day 3 after the drain volume had decreased to <20 mL/day.

Fig 3.

Intraoperative images demonstrating the anatomy of the femoral triangle, before dissecting out the lipoma (A) and after dissecting out the lipoma (B). The femoral artery, femoral vein, and lipoma are labelled. Vessel loops were used to identify the femoral vein and profunda clamps to provide temporary hemostasis, owing to tearing of the vessel while dissecting out the tethered lipoma. Labeled arrows demonstrate major structures.

Histopathology revealed a 67 × 45 × 22 mm homogenous yellow fibrofatty tissue, microscopically mature fat with mildly arborising fibrous septation and unremarkable vasculature, with no concerning features of malignancy.

The patient was followed up at 2 weeks after the procedure, with no postoperative complications and clinical resolution of lower limb edema.

Discussion

There are only a few isolated reports of venous obstruction secondary to a lipoma. Day and Thomas7 presented a case of a 47-year-old man with unilateral swelling of his left leg secondary to a 6 × 3 × 1.5 cm femoral sheath lipoma compressing on the CFV.7 DUSS examination was unremarkable and diagnosis of the lipoma was made using a CT scan. Wronski and Lachowki8 reported, in a 55-year-old female patient, a 10 × 5.5 × 16 cm giant lipoma of the right thigh compressing on the femoral vein and femoral nerve, detected on both DUSS examination and MRI. This patient experienced symptoms of pain, functional impairment, and lower limb edema.8

We present an interesting case of a femoral lipoma compressing on the CFV, causing painless lower limb edema, undetected on DUSS examination. Our case is unique given a history of Dercum's disease, delays in diagnosis owing to confounding DUSS findings, and a tethered lipoma to the CFV necessitating minor repair of the vein during dissection. We, therefore, highlight the importance of CT venogram in cases where the cause of suspected CVI is uncertain, and the importance of familiarity with vascular repair techniques when managing lipomas adjacent to major vascular structures.

Despite lipomas being mostly benign, concerns for malignant transformation arise with giant lipomas, and differentiation from liposarcomas can being challenging without histopathological examination.1 Concerning clinical features include increasing size, fatty masses >5 cm, located deep to deep fascia, and pain.9 Management of simple lipomas are with local or marginal excision, whereas well-differentiated liposarcomas should receive wide local excision owing to their high rates of recurrence.10

DUSS remains the first-line investigation for suspicions of lipomas; however, with limitations of poor resolution in patients with higher BMI, edema, ulceration, and thickened skin.11 Further imaging involves, MRI which provides some ability to distinguish between lipomas and liposarcomas, the latter having thickened septa, nonadipose masses, high T2 signal foci, and areas of enhancements. Yet, apart from its usual discrete, encapsulated, homogenous appearance, simple lipomas can also be confounded by inclusions of muscle fibers, blood vessels, fibrous septa, necrosis, and inflammation.10 In an MRI with few or no thin septa, minimal to no enhancement, and no high T2 signals, 100% specificity has been reported in diagnosing simple lipomas, as demonstrated in our case.

In our case, the patient was referred for concerns of CVI given findings of possible GSV aplasia on DUSS examination. Yet in a previous study on 670 lower limb DUSS examination, there was no association found between segmental aplasia of the GSV in patients with a clinical etiologic anatomic and pathophysiologic score of ≥1.12 In addition, the author reported in the cohort that segmental aplasia was always present in the mid-portion of the GSV, usually with the vein leaving the saphenous compartment below the knee and rejoining in the thigh.12

There are no cases in literature regarding Dercum's disease and lipomatous compression of peripheral vasculature. Thus far, reported complications of the disease include mastalgia,13 steatocutaneous necrosis of a lipoma resulting in septic shock,14 and a lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum.15

In conclusion, we present a case of a deep-seated femoral sheath giant lipoma in a patient with Dercum's disease, compressing the CFV. We propose that, in patients with suspected CVI with inconclusive DUSS examination, a CT venogram is an important investigation to further delineate missed pathologies. In the workup of a giant lipoma, MRI confers high specificity for simple lipomas vs liposarcomas and can aid in decisions between local or marginal excision vs wide local excision. It is the authors' opinion that excision of lipomatous lesions adjacent to or involving major vasculature should be performed by a vascular surgeon, owing to the notable risks of vascular trauma and need for repair or reconstruction.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the Journal policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bayileyegn N.S., Tareke A.A. De-differentiated giant thigh liposarcoma disguised as recurrent lipoma; a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;95 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paunipagar B.K., Griffith J.F., Rasalkar D.D., Chow L.T.C., Kumta S.M., Ahuja A. Ultrasound features of deep-seated lipomas. Insights Imaging. 2010;1:149–153. doi: 10.1007/s13244-010-0019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbardouni A., Kharmaz M., Salah Berrada M., Mahfoud M., Elyaacoubi M. Well-circumscribed deep-seated lipomas of the upper extremity. A report of 13 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kucharz E.J., Kopeć-Mędrek M., Kramza J., Chrzanowska M., Kotyla P. Dercum's disease (adiposis dolorosa): a review of clinical presentation and management. Reumatologia. 2019;57:281–287. doi: 10.5114/reum.2019.89521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansson E., Svensson H., Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campen R., Mankin H., Louis D.N., Hirano M., MacCollin M. Familial occurrence of adiposis dolorosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:132–136. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.110872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day A., Thomas P. Femoral sheath lipoma causing venous obstruction syndrome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:e21–e22. doi: 10.1308/147870810X12699662981195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wronski K., Lachowki A. Giant femoral lipoma causing venous obstructing syndrome case report. Ann Ital Chir. 2015;86:368–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones A.P., Lewis C.J., Dildey P., Hide G., Ragbir M. Lipoma or liposarcoma? A cautionary case report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:e11–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaskin C.M., Helms C.A. Lipomas, lipoma variants, and well-differentiated liposarcomas (atypical lipomas): results of MRI evaluations of 126 consecutive fatty masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:733–739. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnoldussen C.W., de Graaf R., Wittens C.H., de Haan M.W. Value of magnetic resonance venography and computed tomographic venography in lower extremity chronic venous disease. Phlebology. 2013;28:169–175. doi: 10.1177/0268355513477785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oguzkurt L. Ultrasonography study on the segmental aplasia of the great saphenous vein. Phlebology. 2014;29:447–453. doi: 10.1177/0268355513484016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trentin C., Di Nubila B., Cassano E., Bellomi M. A rare cause of mastalgia: dercum's disease (adiposis dolorosa) Tumori. 2008;94:762–764. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haddad D., Athmani B., Costa A., Cartier S. Maladie de Dercum: une complication grave au cours d'une maladie rare. A propos d'un cas. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2005;50:247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miraglia E., Visconti B., Bianchini D., Calvieri S., Giustini S. An uncommon association between lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum (LHIS) and Dercum's disease. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:406–407. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]