Abstract

Background

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) in children and adolescents after blunt traumatic aortic injury (BTAI) is being performed increasingly despite no endovascular graft being approved for TEVAR in this population. The smaller diameter of the aorta and access vessels and steeper angle of the aortic arch pose specific challenges for TEVAR in this population. Moreover, data are lacking regarding medium to long term complications. This case presents an adolescent patient who underwent TEVAR for BTAI and suffered a focal aortic dissection several months later.

Report

The patient initially presented after a motor vehicle accident and underwent an uncomplicated TEVAR procedure with a 28 mm diameter stent graft (the smallest device available at the time) for Grade III traumatic aortic dissection; the native aortic diameter was 15 mm. The diameter mismatch was accepted due to the lifesaving nature of the procedure. More than 7 months later the patient presented to the emergency department after not being able to urinate for several days and experiencing pain, tingling, and weakness in both legs. Blood samples showed a severe acute kidney injury and computed tomography angiography showed significant aortic stenosis in the distal part of the stent graft, probably caused by a focal dissection. The stenosis and dissection were successfully treated using a Palmaz stent, after which his renal function and extremity complaints recovered.

Conclusion

The focal dissection was probably caused by stress on the aortic wall due to the aorta–stent graft diameter mismatch. This case demonstrates that complications after TEVAR in adolescents can arise months after the initial procedure and underscores the need for continued vigilance, especially in cases with an aorta–stent graft mismatch. The threshold for additional imaging and consultation by a vascular surgeon should be low.

Keywords: TEVAR, Paediatric, Adolescent, Aortic stenosis, Blunt traumatic aortic injury

Highlights

-

•

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) is being used increasingly in adolescents, little is known about complications.

-

•

Focal aortic dissection is a possible complication after TEVAR in adolescents.

-

•

Focal aortic dissection can lead to renal failure and lower extremity ischaemia.

-

•

The risk of focal aortic dissection is possibly increased by aorta–stent graft mismatch.

-

•

The threshold for imaging should be low in adolescent patients after TEVAR for blunt traumatic aortic injury.

Introduction

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) in children and adolescents after blunt traumatic aortic injury (BTAI) is being performed increasingly.1,2 However, the Food and Drug Administration has not approved any endovascular graft for TEVAR in children and adolescents;2 therefore, the application of TEVAR has been limited to the off label use of various graft types.3, 4, 5

Paediatric patients have a smaller descending aorta and smaller calibre access vessels. Combined with the steeper angle of the aortic arch, there are specific challenges in endovascular interventions in this population.3,4 Furthermore, children are susceptible to anatomical changes in the long term as they grow older and current devices might not be compatible with these changes.6

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair devices are developed for the treatment of aortic aneurysms and dissections in adults. These devices often have larger diameters compared with the paediatric and adolescent native aorta. Despite this, the Society of Vascular Surgery recommends the use of TEVAR for BTAI patients with suitable anatomy for all age groups.7

Because of the increasing use of TEVAR for BTAI in paediatric patients, it is essential to gather more data on long term complications. Various case reports and series provide information on follow up in this population. Known complications are endoleak and graft collapse or kinking.4,5,8

This case report is of a 17 year old patient who underwent TEVAR for BTAI, complicated by a focal aortic dissection distal of the TEVAR graft several months after the initial implantation caused by an aorta–stent graft diameter mismatch.

Report

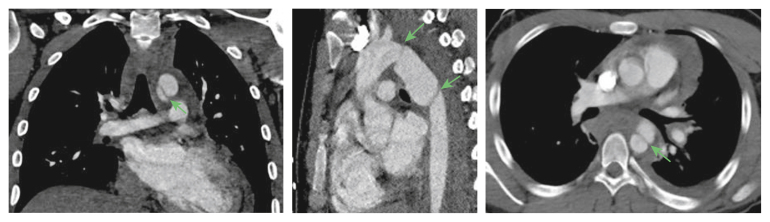

A 17 year old male, with a history of Type 1 diabetes, initially presented to the emergency department after a motor vehicle accident. At presentation the patient was haemodynamically stable. Blood results showed an elevated troponin T level of 0.024 μg/L. Computed tomography angiography of the thorax and abdomen revealed a traumatic dissection of the aortic arch and thoracic part of the descending aorta (BTAI Grade III) with a pseudoaneurysm and mediastinal haematoma, but without active bleeding (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography angiography images of traumatic thoracic aortic transection in a 17 year old male.

The patient underwent an uncomplicated TEVAR procedure. A Cook ZTA P 28 155 stent graft was used, which was the smallest device available in the centre at that time. The diameter mismatch between stent graft and the aortic diameter was accepted (aortic diameter 15 mm, mismatch 13 mm, oversized by 87%). The left subclavian artery was intentionally covered to achieve adequate proximal sealing. Post-operatively, the patient recovered well without complications. Blood pressure was regulated using oral medication and clopidogrel was started. He was discharged 7 days after the TEVAR procedure. Computed tomography angiography six weeks after the procedure showed slight contrast recesses of the aortic wall in the distal part of the graft caused by plications of the graft. There were no signs of complications. The diameter of the native aorta was now 17 mm, reducing oversizing to 65%. The difference in diameter was probably caused by vascular spasms after the trauma. Follow up imaging was scheduled for six months later.

Seven and a half months after the initial procedure, the patient presented to the emergency department with complaints of lower back pain, weakness in both legs, headache, nausea, and vomiting. The complaints were first noticed during the first time exercising (running) since the TEVAR procedure. There were no signs of neurological problems. Further physical examination revealed tenderness in the upper abdomen without signs of complications of the TEVAR stent graft and aorta. Femoral, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial artery pulses were palpable bilaterally and the patient was haemodynamically stable. Blood samples showed slightly elevated creatinine levels of 98 μmol/L compared with the previous visit to the outpatient clinic (57 μmol/L). Furthermore, the patient said that he had continued clopidogrel. A CT angiogram was not performed because there were no clinical signs of TEVAR complications and the patient was discharged home by the emergency department physician.

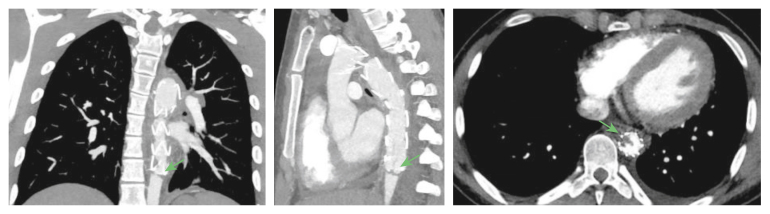

The patient presented to the emergency department again four days later. The symptoms had not improved. In addition to the previous complaints, the patient now described pain in both legs extending to the calves, as well as a tingling sensation and cold lower extremities. Most notably the patient reported not having urinated since his previous visit. On physical examination the femoral, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial arteries were impalpable. Blood samples showed an increased creatinine level of 1 111 μmol/L. Computed tomography angiography revealed increased contrast recesses in the distal part of the graft, resulting in significant stenosis (Fig. 2). It was initially believed that this was caused by intimal hyperplasia leading to thrombus accumulation distally from the graft. There were no signs of distal embolisation to the kidneys or legs.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography angiography images of aortic stenosis directly distal to the TEVAR graft.

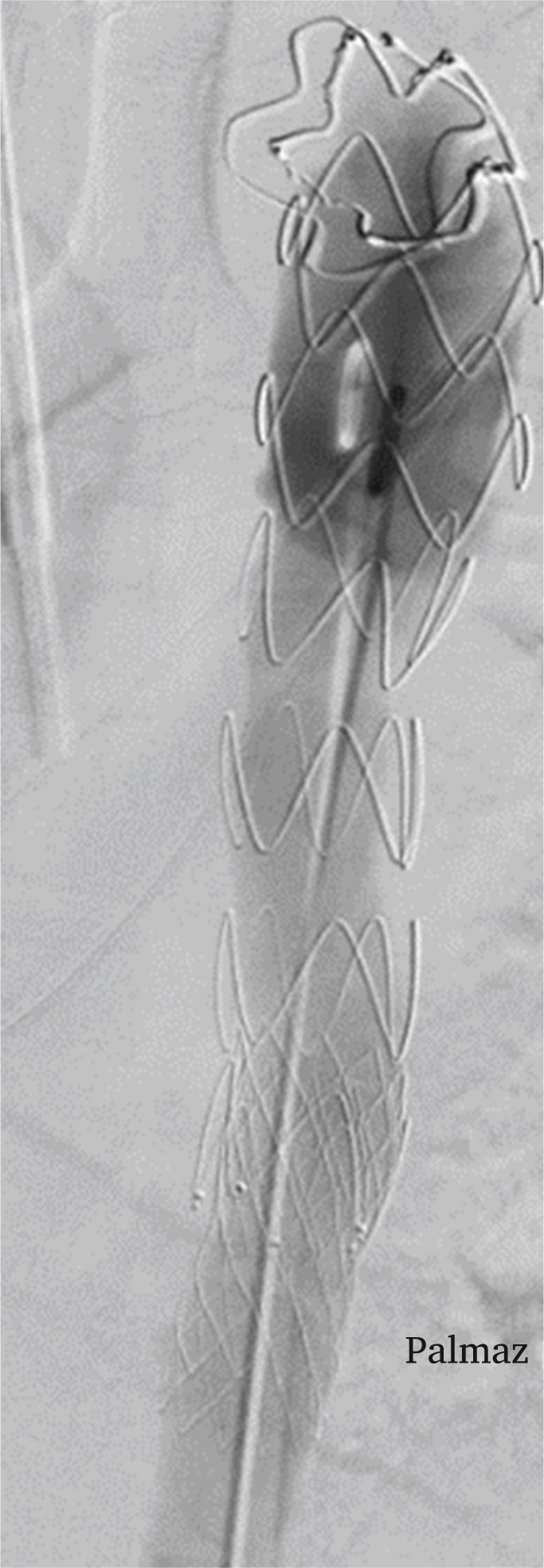

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for catheter directed thrombolysis using alteplase 1 mg/hour and intermittent haemodialysis. Digital subtraction angiography during thrombolysis revealed a ledge-like abnormality directly below the stent graft. After 36 hours of thrombolysis there was no improvement in the stenosis or renal function. Since there was a ledge like abnormality seen on initial angiography and thrombolysis did not affect the stenosis, the hypothesis was adjusted and it was believed that the stenosis was caused by a focal dissection leading to mural thrombus accumulation. Arterial pressure in the abdominal aorta measured by the thrombolysis access sheath was 35/32 mmHg compared with 120/55 mmHg in the thoracic stent graft. The stenosis was successfully treated with a Palmaz P 50 14 stent using a 20 mm balloon (Fig. 3). Peripheral arterial pressure increased to 90/50 mmHg compared with a central pressure of 104/52 mmHg. One day later the serum creatinine levels were lowered to 170 μmol/L with return of diuresis. Serum creatinine normalised to 80 μmol/L two days after placement of the Palmaz stent. The patient was discharged after three days with clopidogrel, which is to be used lifelong. At the outpatient clinic six weeks after discharge the patient had recovered completely.

Figure 3.

Situation after placement of Palmaz stent.

Discussion

This is the first case describing significant aortic stenosis caused by consequences of a focal dissection distal to the stent graft after TEVAR for BTAI in an adolescent patient. It is believed that the focal aortic dissection was caused by chronic stress on the aortic wall due to the aorta–stent graft diameter mismatch. It is well known that aortic pulsatility can be substantial in the thoracic aorta of young patients.9 Temporary increases in stress on the aortic wall caused by a higher cardiac output due to physical exercise results in greater forces between the stent graft and aortic wall.

Although initially life saving, this case illustrates that complications after TEVAR for BTAI in adolescents can arise months after the initial procedure. It is well known that aorta–stent graft diameter mismatch can result in complications. In adolescents, especially, there are two major differences compared with adults. First, the aortic diameter is much smaller, and second, the aortic strain is much higher.9 Patients can initially present with symptoms that might seem unrelated to the TEVAR procedure. In addition to the well known complications mentioned above, healthcare professionals should be aware of the complications that diameter mismatch can give, such as a focal dissection, which can result in a patent false lumen. The threshold for imaging should be low, as the consequences of missing the complications are severe.

In retrospect, the focal dissection was probably already present during the first emergency department visit after TEVAR, despite no other specific signs of TEVAR related complications being present. If CT angiography had been performed during this visit, this complication would have been diagnosed sooner and acute renal failure could possibly have been avoided.

In summary, this case shows that adolescent patients, in whom there is an aorta–stent graft diameter mismatch, are at risk of developing a focal aortic dissection at the transition from stent graft to the native aorta. This complication is similar to distal stent graft induced new entry tears (dSINE) often seen in TEVAR procedures in adults. Studies have shown that excessive oversizing is a risk factor for dSINE in TEVAR procedures.10 The difference being that the focal dissection in this case did not communicate with the false lumen and was therefore not a dSINE.

The choice to treat the stenosis with a Palmaz stent can be point of discussion. A Palmaz stent was chosen because there was no concern about distal embolisation and complications from further coverage of the descending aorta needed to be prevented. It is believed that regular imaging follow up (e.g., annual CT angiography) in the outpatient clinic is not beneficial to screen for possible focal dissections. Imaging merely provides a snapshot of the aorta and stent graft at a specific point in time. If a dissection occurs, patients will present to the emergency department and be diagnosed by a proper diagnostic work up, including imaging. However, it is believed that it is of the utmost importance to educate patients on possible long term complications of an aorta–stent graft diameter mismatch. Accessible consultation with a vascular surgeon and CT angiography is of the greatest importance.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Raulli S.J., Schneider A.B., Gallaher J., Motta F., Parodi E., Farber M.A., et al. Trends and outcomes in management of thoracic aortic injury in children, adolescent, and mature pediatric patients using data from the National Trauma Data Bank. Ann Vasc Surg. 2023;89:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2022.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasjim B.J., Grigorian A., Barrios C., Schubl S., Nahmias J., Gabriel V., et al. National trends of thoracic endovascular aortic repair versus open thoracic aortic repair in pediatric blunt thoracic aortic injury. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;59:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2018.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azizzadeh A., Keyhani K., Miller C.C., Coogan S.M., Safi H.J., Estrera A.L. Blunt traumatic aortic injury: initial experience with endovascular repair. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1403–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunabushanam V., Mishra N., Calderin J., Glick R., Rosca M., Krishnasastry K. Endovascular stenting of blunt thoracic aortic injury in an 11-year-old. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45 doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiremath G., Morgan G., Kenny D., Batlivala S.P., Bartakian S. Balloon expandable covered stents as primary therapy for hemodynamically stable traumatic aortic injuries in children. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;95:477–483. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Min S.-K., Cho S., Kim H.-Y., Kim S.J. Pediatric vascular surgery review with a 30-year-experience in a tertiary referral center. Vasc Specialist Int. 2017;33:47–54. doi: 10.5758/vsi.2017.33.2.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee W.A., Matsumura J.S., Mitchell R.S., Farber M.A., Greenberg R.K., Azizzadeh A., et al. Endovascular repair of traumatic thoracic aortic injury: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonker F.H., Schlosser F.J., Geirsson A., Sumpio B.E., Moll F.L., Muhs B.E. Endograft collapse after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Endovasc Ther. 2010;17:725–734. doi: 10.1583/10-3130.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Csobay-Novák C., Fontanini D.M., Szilágyi B.R., Szeberin Z., Szilveszter B.A., Maurovich-Horvat P., et al. Thoracic aortic strain can affect endograft sizing in young patients. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:1479–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.06.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’cruz R.T., Syn N., Wee I., Choong A.M.T.L. Risk factors for distal stent graft-induced new entry in type B aortic dissections: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2019:70. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]