Abstract

No treatment exists for mitochondrial dysfunction, a contributor to end-organ disease in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The mitochondrial antioxidant mitoquinone mesylate (MitoQ) attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction in preclinical mouse models of various diseases but has not been used in HIV. We used a humanized murine model of chronic HIV infection and polymerase chain reaction to show that HIV-1–infected mice treated with antiretroviral therapy and MitoQ for 90 days had higher ratios of human and murine mitochondrial to nuclear DNA in end organs compared with HIV-1–infected mice on antiretroviral therapy. We offer translational evidence of MitoQ as treatment for mitochondrial dysfunction in HIV.

Keywords: antioxidant, chronic treated HIV, end-organ disease, MitoQ, mitochondria

No treatment exists for mitochondrial dysfunction, a contributor to end-organ disease in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The mitochondrial antioxidant mitoquinone mesylate attenuated reduction of mitochondrial DNA as measure of mitochondrial dysfunction in end organs of an animal model of HIV.

Despite potent antiretroviral treatment (ART) for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), people living with HIV, compared with uninfected individuals, have an increased incidence of comorbid conditions, such as cardiovascular and liver disease [1]. The pathogenesis of increased morbidity in chronic treated HIV infection remains unclear. Mitochondria are key cellular organelles for metabolism and are responsible for most of the cellular reactive oxygen species (mitochondrial reactive oxygen species or mito-ROS) [2]. Emerging evidence has suggested that both HIV-1 and ART treatment lead to dysfunction of mitochondria that further drives oxidative stress, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations, and cellular apoptosis [3]. mtDNA does not have a DNA repair mechanism, making it highly susceptible to damage, which can lead to mtDNA depletion and ultimately cell and tissue dysfunction [4]. Aging leads to mtDNA damage and dysfunction [5]. Determination of the relative amount of mitochondrial versus nuclear DNA (nDNA) and the mtDNA/nDNA ratio using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) provides a robust quantitative estimation of mtDNA copy number that predicts the effect of aging on the decrease in mtDNA [4] and may be a good biomarker for progression of several diseases [6]. Thus, targeting oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment may be promising treatments for end-organ disease in HIV.

MitoQ is the only mitoquinone mesylate mitochondrial antioxidant approved for human use that can target the harmful production of mito-ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction [7]. We have previously shown in a preclinical mouse model of HIV that MitoQ may attenuate secretion of interleukin 1β and interleukin 6, which contribute to neuroinflammation and pathogenesis of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder [8]. Thus, we hypothesized that MitoQ may be effective in reducing mitochondrial dysfunction, which contributes to end-organ disease in chronic HIV infection. Owing to the confounding variables within human studies and limited tissue access to end organs, we used a preclinical humanized mouse model of chronic treated HIV infection to determine whether MitoQ attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction in the brain, heart, aorta, kidney, gut, and liver tissues. NOD scid gamma (NSG) bone marrow–liver–thymus (BLT) mice are an established model of HIV-1 immunopathogenesis that allows functional human immune cells (also present in tissues) to be infected and dysfunction of human mitochondria to be studied in vivo [8, 9]. In the current study, we demonstrate that HIV-1–infected mice treated with ART and MitoQ, compared with those treated with only ART, had higher ratios of human and murine mtDNA/nDNA in end organs.

METHODS

Mice

The study used 6–8-week-old NSG BLT mice [n = 25; similar number male (n = 13) and female (n = 12)], generated from the same human donor tissue and maintained as described elsewhere [9, 8]. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with federal, state, and institutional (University of California, Los Angeles) approved guidelines. Human fetal tissue was purchased from Advanced Biosciences Resources from anonymous donors and did not require institutional review board approval for usage. Only mice for which all target tissues were available were included in this substudy of our group’s previously published study [8]. There were 3 study groups: HIV-uninfected mice (n = 5), HIV-infected mice on potent ART (HIV+ART+; n = 5), and HIV-infected mice on ART with the addition of MitoQ (HIV+ART+MitoQ+; n = 5).

Treatments

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 500 ng p24 of dual-tropic HIV-1 89.6 virus, and viral loads were determined 4 weeks after infection by means of PCR, as described elsewhere [8, 9]. HIV-infected mice NSG were treated subcutaneously with daily ART (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [8.75 mg/kg], emtricitabine [13 mg/kg], and raltegravir [17.5 mg/kg]) [8]. MitoQ was a gift from MitoQ Ltd. Mice were administered MitoQ (500 μmol/L) for 90 days, via drinking water that contained MediDrop sucralose liquid gel [8]. Control mice did not receive MitoQ.

Determination of mtDNA/nDNA Ratio

Tissue was processed as described elsewhere [8]. Briefly, 10–20 mg of frozen tissue (brain, aorta, heart, kidney, or intestine) was transferred to a 2-mL Precellys tube using the Quick-DNATM MicroPrep DNA extraction kit (Zymo Research). Both mtDNA and nDNA were quantified in triplicate in each sample, using quantitative PCR (qPCR). The primers used are listed in the Supplementary Table 1. The qPCR protocol included a 3-minute denaturation step at 95°C and repeated 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 15 seconds at 57°C, and 10 seconds at 72°C. The following formulas were used:

ΔCt = Ct (mtDNA gene) − Ct (nDNA gene)

and

ΔΔCt = ΔCt (Sample) − ΔCt (Control Sample),

where Ct represents cycle threshold; ΔCt, ; and ΔΔCt, . The estimated fold calculus of the ΔΔCt value (2−ΔΔCt) was used as a measure of the relative mtDNA/nDNA ratios among the compared groups [4].

Statistical Analysis

Bars depict means with standard errors of the mean. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare 3 groups, and the Mann-Whitney test to compare 2 groups. Differences by either test were deemed significant at P < .05, by either test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad software (version 8.0).

RESULTS

Differential Amount of Human mtDNA in End Organs of Humanized Mice

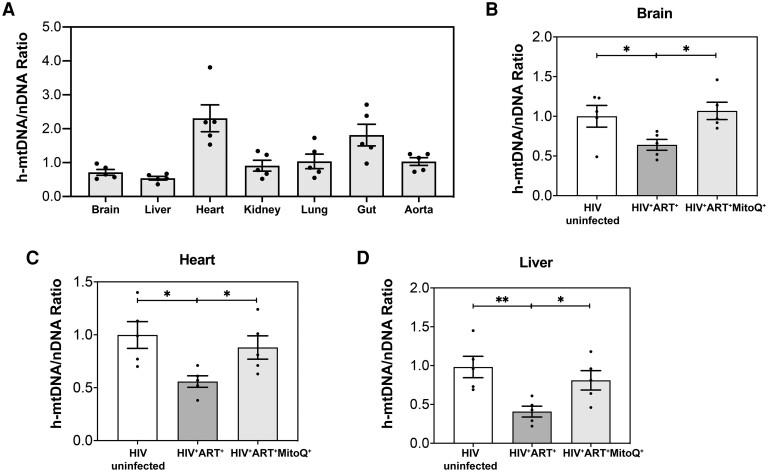

Using NSG BLT mice and a sensitive qPCR assay [4], we first determined the human mtDNA (h-mtDNA)/nDNA ratio as a measure of mitochondrial dysfunction in human immune cells that infiltrate tissues and end organs and contribute to tissue inflammation in humanized mice [8, 9]. h-mtDNA was detected in all studied tissues (brain, heart, liver, kidney, lung, aorta, and small intestine) ,and the h-mtDNA/nDNA ratio varied between 0.36 and 3.8 (Figure 1A). The heart and gut had the highest h-mtDNA/nDNA ratio, while the brain, liver, kidney, lung, and aorta had similar h ratios (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), antiretroviral therapy (ART) and mitoquinone mesylate (MitoQ) on human mitochondrial DNA (h-mtDNA) in end organs in a humanized mouse model of chronic HIV-1 infection. NOD scid gamma humanized mice were infected with HIV-1 for 90 days and treated with ART alone (HIV+ART+) or in combination with oral MitoQ (HIV+ART+MitoQ+); MitoQ was given in water (500 μmol/L) for 60 days. Brain, liver, heart, kidney, lung, gut, and aorta tissues from each mouse were harvested after euthanasia and included both murine cells and human immune cells containing h-mtDNA and nuclear DNA (nDNA). The h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios were determined in HIV-uninfected, HIV+ART+, and HIV+ART+MitoQ+ mice (each n = 5), using polymerase chain reaction, as described in Methods. A, Summary data for h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the end organs of uninfected humanized mice. B–D, Summary data for h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the brain (B), heart (C), and liver (D) of humanized mice, HIV-uninfected, HIV+ART+, and HIV+ART+MitoQ+. Data are presented as mtDNA/nDNA ratios in each tissue sample relative to the mean of the uninfected group; data represent means with standard errors of the mean, and each data point represents a mouse and the average of 3 replicates. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare 3 groups, and the Mann-Whitney test to compare 2 groups. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Decreased h-mtDNA in End Organs of HIV+ART+ Humanized Mice Compared With Uninfected Mice

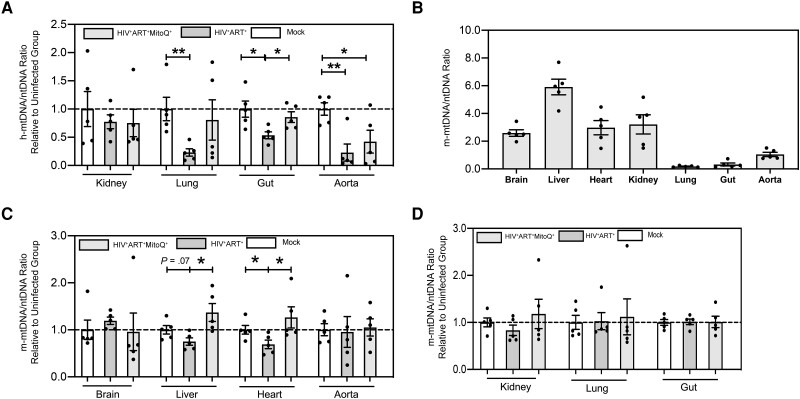

We then assessed the direct impact of the combined effect of HIV and ART on the h-mtDNA/nDNA ratio as a measure of mitochondrial dysfunction of human immune cells in HIV (Figure 1B–1D and Figure 2A). All HIV+ART+ NSG BLT mice had suppressed plasma viremia after 4 weeks of potent ART, as reported elsewhere [8]. In HIV+ART+ NSG BLT mice after 90 days of potent ART, compared with uninfected mice, we observed decreased h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the brain (Figure 1B), heart (Figure 1C), liver (Figure 1D), lung, and gut (Figure 2A) (P < .05 for all comparisons). However, we did not observe change in h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the kidney and aorta of HIV+ART+ compared with uninfected mice (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), antiretroviral therapy (ART) and mitoquinone mesylate (MitoQ) on human and murine mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in end organs in a humanized mouse model of chronic HIV-1 infection. NOD scid gamma (NSG) humanized mice were infected with HIV-1 for 90 days and treated with ART alone (HIV+ART+) or ART in combination with oral MitoQ (HIV+ART+MitoQ+); MitoQ was given in water (500 μmol/L) for 60 days, as shown in Figure 1. Brain, liver, heart, kidney, lung, gut, and aorta tissue from each mouse was harvested after euthanasia, and the human mtDNA (h-mtDNA)/nuclear DNA (nDNA) and murine mtDNA (m-mtDNA)/nDNA ratios were determined in uninfected, HIV+ART+, and HIV+ART+MitoQ+ mice, using polymerase chain reaction, as described in Methods. A, Summary data for h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the kidney, lung, gut and aorta of humanized mice; data are presented as mtDNA/nDNA ratio in each tissue sample, relative to the mean of the uninfected (mock) group. B, Summary data for m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the end organs of uninfected humanized mice. C, D, Summary data for m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the brain, liver, heart, and aorta (C) and in the kidney, lung, and gut (D) of humanized mice; data are presented as mtDNA/nDNA ratios in each tissue sample, relative to the mean of the uninfected (mock) group. Data represent means with standard errors of the means, and each data point represents a mouse and the average of 3 replicates. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare 3 groups, and the Mann-Whitney test to compare 2 groups. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Decreased Heart Murine mtDNA Levels in HIV+ART+ Humanized Mice Compared With Uninfected Mice

We determined the levels of murine mtDNA (m-mtDNA) in the end organs of humanized mice. Mouse cells cannot be infected with HIV-1, and any differences in the m-mtDNA/nDNA in tissues compared with uninfected mice may reflect direct effects of ART on murine cells or indirect effects of HIV-1 infection on the human immune cells. The mitochondria-enriched tissues, such as the brain, liver, heart, and kidney [10], had the highest m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios, compared with the lung, gut, and aorta (Figure 2B). Compared with uninfected mice, HIV+ART+ mice showed decreased m-mtDNA levels in the heart (P < .05) and a trend (P = .07) for decreased m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the liver (Figure 2C). No differences in m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios were observed in the brain, aorta (Figure 2C), kidney, lung, or gut (Figure 2D) of HIV+ART+ compared with uninfected mice. In conclusion, HIV+ART+ mice had decreased m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the mitochondria-enriched heart compared with uninfected mice, suggesting a direct impact of ART per se on cardiac mitochondria.

Impact of MitoQ on m-mtDNA/nDNA Ratios in End Organs of Humanized Mice

We hypothesized that MitoQ, shown to have favorable impact on mitochondrial dysfunction in preclinical models of end-organ disease [7], could attenuate reduced mtDNA/nDNA ratios driven by HIV-1–infected human immune cells from an NSG BLT mouse brain. Compared with HIV-infected mice given ART, the addition of MitoQ (500 μmol/L) in water for 60 days in HIV+ART+ mice (HIV+ART+MitoQ+ mice) led to increased h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the brain (Figure 1B), heart (Figure 1C), liver (Figure 1D), and gut (Figure 2A) (P < .05 for all comparisons). Compared with HIV+ART+ mice, HIV+ART+MitoQ+ mice had increased m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in their liver and heart (Figure 2C) (P < .05 for all comparisons). No differences were observed in h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the kidney, lung, or aorta (Figure 2A) or m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the brain, aorta (Figure 2C), kidney, or lung tissue (Figure 2D) in HIV+ART+ compared with HIV+ART+MitoQ+ mice. Compared with HIV-1–uninfected mice, HIV+ART+MitoQ+ mice had similar h-mtDNA/nDNA and m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in all studied tissues except the aorta (Figures 1B-1D, 2A, 2C, and 2D). These results suggest that MitoQ effectively attenuated HIV-1–induced and/or ART-induced reduction in mtDNA/nDNA ratios as a measure of mitochondrial dysfunction in end organs of HIV-1–infected BLT mice on potent ART.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first preclinical demonstration of the potential therapeutic role of MitoQ for treatment of mitochondrial dysfunction, an established instigator of end-organ disease [11–13], in chronic treated HIV infection. Herein, using the BLT mouse model of chronic treated HIV infection and sensitive PCR, we showed that, compared with uninfected mice, HIV-1–infected NSG BLT mice on potent ART had reduced h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in mitochondria of immune cells present in mitochondria-enriched end organs such as the brain, heart, liver, lung, and gut and reduced m-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in the heart. Among HIV-1–infected NSG BLT mice, those on ART plus oral MitoQ for 2 months showed increased h-mtDNA/nDNA ratios in end organs like the brain, heart, liver, lung, and gut, compared with those on ART alone. Given the role of mt-DNA depletion in mitochondrial function, aging, cell, and tissue dysfunction [5, 6], administration of MitoQ had a favorable effect on HIV- and/or ART-driven mtDNA depletion that contributed to end-organ disease in chronic treated HIV infection [13].

Mitochondrial dysfunction, acquired mtDNA mutations, and oxidative stress contribute to aging and associated diseases, such as diabetes and cancer [6]. HIV-infected patients have increased levels of mito-ROS [2] and reduced mtDNA content that contribute to pathogenesis of certain end-organ diseases, such as brain aging [13]. To our knowledge, our study is among the first that mechanistically determined in vivo the effects of HIV-1 and ART on mtDNA and mitochondrial function in multiple end organs. Cross-sectional human studies cannot truly determine the differential effect of HIV-1 per se versus that of ART on mtDNA and mitochondrial function. In the mitochondria-enriched heart, we showed that ART alone, but not HIV-1, contributed to a reduction in m-mtDNA. In other end organs of humanized mice, we found that both HIV-1 and ART contributed to a reduction in h-mtDNA. Our data are consistent with data from others showing that age-associated mtDNA damage is driven by HIV per se rather than by ART toxicity and may contribute to neurocognitive impairment [13]. Our data indicating that administration of MitoQ had a favorable effect on HIV- and/or ART-driven mtDNA depletion are also consistent with prior evidence that MitoQ attenuates aberrantly elevated mito-ROS levels and oxidative and mtDNA damage in both preclinical models of disease [7] and human studies [14].

Our study has several limitations. BLT mice cannot fully recapitulate HIV infection. Although human myeloid and T cells have been described in the tissues of NSG BLT mice [15], these mice cannot be used to study human parenchymal tissue cells that are the main source of mitochondria in tissues. The lack of a viremic HIV+ mouse group that was not on ART did not allow us to fully dissect the differential impact of HIV-1 per se versus ART on mitochondrial dysfunction. Despite the limitations, the NSG BLT model can support HIV infection and can be used to monitor the systemic responses of a variety of human immune cells—including T cells and myeloid cells—to HIV-1 infection and potent ART treatment. Although the focus of this study was to evaluate mtDNA that is mechanistically linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, we did not study other mediators of mitochondrial function. Further work is necessary to assess the impact of MitoQ in all known measures of mitochondrial function in HIV.

In conclusion, MitoQ is safe and has been used as an oral diet supplement in humans for decades. It has also been used safely in clinical trials with no toxic effects [7]. Herein, we provide robust preclinical evidence supporting further clinical trials to test whether MitoQ can be a useful treatment for mitochondrial dysfunction as instigator of tissue damage in chronic treated HIV infection.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Sihyeong Song, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Sandro Satta, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Madhav B Sharma, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Cristelle Hugo, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Athanassios Kossyvakis, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Shubhendu Sen Roy, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Theodoros Kelesidis, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Notes

Acknowledgments . The following reagent was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health: HIV-1 89.6 virus from Dr Ronald Collman. Antiviral compounds were generously supplied by Gilead Sciences, and MitoQ compound was generously supplied by MitoQ. We thank the UCLA Humanized Mouse Core (Scott Kitchen, PhD and Valerie Rezek) for their assistance with humanized mouse studies.

Author contributions . T. K. conceived the project, designed and analyzed experiments, and wrote the manuscript, with contributions from S. Song, and provided financial support. A. K. and S. S. R. helped conduct the animal studies. S. Song, S. Satta, M. B. S., and C. H. performed the molecular experiments.

Financial support . This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01AG059501, R21AI36708, R21HL134444, R03AG059462, R03AG059462, and K08AI108272 to T. K. and grant P30AI28697 to the UCLA Center for AIDS Research [for purchase of flow cytometry machine]); the California HIV/AIDS Research Program (grant OS17-LA-002 to T. K.); and the Campbell Foundation (T. K.).

Data availability

All data needed to understand and assess the conclusions of this research are available in the main text and supplementary materials. Raw data sets supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Kelesidis T, Currier JS. Dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2014; 43:665–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ivanov AV, Valuev-Elliston VT, Ivanova ON, et al. Oxidative stress during HIV infection: mechanisms and consequences. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016; 2016:8910396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schank M, Zhao J, Moorman JP, Yao ZQ. The impact of HIV- and ART-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in cellular senescence and aging. Cells 2021; 10:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Quiros PM, Goyal A, Jha P, Auwerx J. Analysis of mtDNA/nDNA ratio in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 2017; 7:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bratic A, Larsson NG. The role of mitochondria in aging. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:951–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Nat Rev Genet 2005; 6:389–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith RA, Murphy MP. Animal and human studies with the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1201:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Satta S, Hugo C, Sharma M, et al. Mitoquinone mesylate attenuates brain inflammation in humanized mouse model of chronic HIV infection. AIDS 2022; 36:1609–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daskou M, Mu W, Sharma M, et al. ApoA-I mimetics reduce systemic and gut inflammation in chronic treated HIV. PLoS Pathog 2022; 18:e1010160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Filograna R, Mennuni M, Alsina D, Larsson NG. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in human disease: the more the better? FEBS Lett 2021; 595:976–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang J, Guo Q, Feng X, Liu Y, Zhou Y. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: potential targets for treatment. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022; 10:841523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Middleton P, Vergis N. Mitochondrial dysfunction and liver disease: role, relevance, and potential for therapeutic modulation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2021; 14:17562848211031394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roca-Bayerri C, Robertson F, Pyle A, Hudson G, Payne BAI. Mitochondrial DNA damage and brain aging in human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e466–e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williamson J, Hughes CM, Cobley JN, Davison GW. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ, attenuates exercise-induced mitochondrial DNA damage. Redox Biol 2020; 36:101673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Honeycutt JB, Liao B, Nixon CC, et al. T cells establish and maintain CNS viral infection in HIV-infected humanized mice. J Clin Invest 2018; 128:2862–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to understand and assess the conclusions of this research are available in the main text and supplementary materials. Raw data sets supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.