Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to identify rational empirical dosing strategies for cefepime treatment in critically ill patients by utilizing population pharmacokinetics and target attainment analysis.

Patients and methods

A prospective and opportunistic pharmacokinetic (PK) study was conducted in 130 critically ill patients in two ICU sites. The plasma concentrations of cefepime were determined using a validated LC-MS/MS method. All cefepime PK data were analysed simultaneously using the non-linear mixed-effects modelling approach. Monte Carlo simulations were performed to evaluate the PTA of cefepime at different MIC values following different dose regimens in subjects with different renal functions.

Results

The PK of cefepime in critically ill patients was best characterized by a two-compartment model with zero-order input and first-order elimination. Creatinine clearance and body weight were identified to be significant covariates. Our simulation results showed that prolonged 3 h infusion does not provide significant improvement on target attainment compared with the traditional intermittent 0.5 h infusion. In contrast, for a given daily dose continuous infusion provided much higher breakpoint coverage than either 0.5 h or 3 h intermittent infusions. To balance the target attainment and potential neurotoxicity, cefepime 3 g/day continuous infusion appears to be a better dosing regimen than 6 g/day continuous infusion.

Conclusions

Continuous infusion may represent a promising strategy for cefepime treatment in critically ill patients. With the availability of institution- and/or unit-specific cefepime susceptibility patterns as well as individual patients’ renal function, our PTA results may represent useful references for physicians to make dosing decisions.

Introduction

Cefepime is a fourth-generation cephalosporin with activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms. Like other β-lactams, cefepime is a hydrophilic compound that is primarily eliminated through renal excretion, has low protein binding (∼20% or less) and a short half-life (2–3 h under normal kidney function).1,2 β-Lactams, including cefepime, are known to display time-dependent killing, which means that the percentage of the dosing interval where unbound plasma drug concentrations exceed the MIC (fT > MIC) ties closely to efficacy and correspondingly represents the most relevant pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) index predicting outcome. The traditional PK/PD index of cefepime for bacterial killing is 60%–70% fT > MIC.3,4 An exposure of 100% fT > MIC (i.e. fCtrough/MIC >1) has also been recommended for microbiological success, prevention of bacterial regrowth and improved clinical outcomes for patients with serious infections.5 In addition, a more aggressive PK/PD target such as 100% fT > 4×MIC (i.e. fCtrough/MIC >4) has been proposed for highly resistant pathogens.6

Because of its broad coverage, cefepime has been extensively used as an empirical therapy in critically ill patients with severe infections. Increasing rates of antimicrobial resistance and complex physiology in critically ill patients make defining adequate dosing regimens of cefepime in this vulnerable population challenging. Several reports indicate that traditional doses of cefepime (e.g. 1 g every 12 h, or 2 g every 12 h, 30 min infusion) may be inadequate in achieving meaningful PTA for cefepime with organisms with higher MIC (e.g. 2–8 mg/L).7–9 In the same vein, questions remain on susceptibility breakpoints. In 2014, the CLSI revised criteria for cefepime against Enterobacterales, where the susceptible dose-dependent category was introduced: the breakpoint was reduced to ≤2 mg/L for fully susceptible isolates based on a dose regimen of 1 g every 12 h; with higher dose regimens, the breakpoint is 4 mg/L (1 g every 8 h or 2 g every 12 h) or 8 mg/L (2 g every 8 h).10,11 The ‘achievability’ of the breakpoints listed by the CLSI following the dose regimens suggested remains unclear.

Despite great effort in evaluating the disposition and PTA of cefepime in critically ill patients, most studies suffer from small sample size and/or the retrospective nature of the study.7,8,12–16 Questions remain on the appropriate cefepime dosing strategy in critically ill patients. To address this clinical need, we aimed to identify rational empirical dosing strategies for cefepime by undertaking a prospective population PK study in critically ill patients.

Materials and methods

Subjects and study design

The prospective and opportunistic study, initiated in December 2017 and completed in December 2019, was carried out at the University of Iowa Hospital and Clinics as well as Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each study site. Eligible participants were adult men and non-pregnant women admitted to the ICU who were prescribed cefepime per standard of care. All subjects provided informed consent prior to any study-related procedures. Cefepime was administered as intermittent IV infusions following different dose regimens per standard of care.

Bioanalytical methods

The total concentrations of cefepime in human plasma were determined using our recently published LC-MS/MS method, which was validated according to FDA guidance.17,18 The assay was linear from 0.5 to 150 mg/L for cefepime. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) is 0.5 mg/L. The plasma samples were stored at −80°C and all samples were analysed within the validated storage stability period (i.e. 11 months).

Population PK model development

All cefepime PK data were analysed simultaneously using the non-linear mixed-effects modelling approach within NONMEM (version 7.4.3; Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA). R (version 4.1.3) and Sigmaplot 14.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA) were used for data handling and graphical analysis.

During the model building process, several different model structures, such as one- and two-compartment disposition models, were evaluated, all of which were parameterized in terms of CL, volume of distribution in each compartment (V1, V2, etc.), and intercompartmental clearance, if applicable, between the peripheral compartment and the central compartment (Q). In addition to linear elimination, models with saturable, and parallel linear and saturable elimination were also evaluated. Because cefepime was given through IV infusion, drug administration was modeled as a zero-order process with duration of infusion as reported from the medical chart. The interindividual variability (IIV) of the PK parameters for cefepime was estimated using an exponential parameter variability model. Regarding residual variability of the cefepime model, an additive error model, a proportional error model, and a combined additive and proportional error model were examined.

The covariates considered in the analysis included age, sex, TBW, lean body weight, estimated creatinine clearance (calculated by the Cockcroft–Gault equation) based on TBW and lean body weight, presence or absence of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), mortality/severity of disease scores (SOFA), sepsis, septic shock, acute kidney injury, abnormal hepatic function and mechanical ventilation. Total body weight, lean body weight, estimated creatinine clearance, and presence or absence of CRRT were biological covariates that were evaluated first. Subsequently, the potential effects of other covariates were assessed. Prior to formal covariate model evaluation, an exploratory analysis was performed. Covariates that showed a correlation with the PK parameters were evaluated further using the standard forward addition [Δobjective function value (OFV) >3.85; P < 0.05] and backward elimination (ΔOFV >6.63; P < 0.01) method.

The effect of continuous variables (e.g. bodyweight) was evaluated using the following general equation:

| (1) |

where is the individual PK parameter, TVP is the population mean of the corresponding PK parameter, is the individual covariate, is the population median of the covariate, and is the covariate effect. For total and lean body weight, was fixed to 0.75 for clearance and 1 for volume of distribution.

CLCR was evaluated as a covariate on renal clearance, with non-renal clearance modelled as an additive parameter. Inclusion of the clearance by CRRT (CLCRRT) was evaluated by estimating it as a parameter in patients on CRRT:

| (2) |

where FCRRT = 1 for patients who were on CRRT; and FCRRT = 0 for patients who were not on CRRT. TVCLR, TVCLNR and CLCRRT were the typical values of renal clearance (in non-CRRT subjects), non-renal clearance and renal clearance in CRRT subjects, respectively. Generally, CLNR would be expected to be similar between patients on CRRT and those not on CRRT. Therefore, this equation assumes that CLNR was the same in patients on CRRT and those not on CRRT, and that patients on CRRT had negligible residual renal function.

To evaluate model performance, a likelihood ratio test was used to compare nested candidate models where a decrease in the NONMEM objective function (−2 log likelihood) of 3.84 points is necessary to consider the improvement in model performance statistically significant at α = 0.05. The Akaike information criterion was used for comparing non-nested candidate models. Other selection criteria included goodness-of-fit plots, plausibility of the estimated parameters, and reduced variance of IIV and residual errors. The predictive performance of candidate models, including the final model, was evaluated using prediction-corrected visual predictive checks (pcVPC). The robustness of the base model and the final model was assessed using a non-parametric bootstrap method (n = 1000) to obtain the 95% CI for the parameter estimates.

PTA analysis

Based on the final population PK model for cefepime, Monte Carlo simulations were performed using NONMEM to evaluate the PTA for different dosing regimens of cefepime, including 1 g every 12 h, 2 g every 12 h, 1 g every 8, and 2 g every 8 h following intermittent 30 min infusions, all of which are currently used clinically in our study sites. In addition, we evaluated the PTA of cefepime following prolonged intermittent infusions, including 1 g or 2 g every 12 h as 3 h infusions, and 1 g or 2 g every 8 h as 3 h infusions. Continuous infusion with 3 g, 6 g or 8 g daily were also evaluated. For each dosing regimen, 6500 virtual subjects were simulated, including 2100 subjects with CLCR <60 mL/min, 2850 subjects with CLCR 60–129 mL/min and 1550 subjects with CLCR >130 mL/min. The patient characteristics used in the simulations, including the distribution of the renal function and body weight, are provided in Figure S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). In total 11 different dosing regimens were evaluated. Concentration–time profiles were simulated at steady-state, and unbound (free) concentrations were predicted using literature-reported plasma protein binding of 20% for cefepime.2

Based on the Monte Carlo simulation results, the PTA was calculated for each cefepime dosing regimen over a wide MIC range with the following different PK/PD targets: 65% fT > MIC, 100% fT > MIC and 100% fT > 4 × MIC. Published MIC distributions were considered in choosing the range of MICs for which the PTA was evaluated, including those by CLSI and EUCAST.11,19 The PK/PD breakpoint, defined as the highest MIC at which ≥90% of the population are expected to achieve the predefined PK/PD target, was calculated for each dosing regimen.

In addition to PTA for antibacterial effect, the probability of potential toxicity of cefepime was also evaluated. Based on the simulated cefepime PK profiles, the percentages of subjects with Ctrough exceeding different thresholds, including 20 mg/L, 35 mg/L, 49 mg/L and 63.2 mg/L, that have been proposed among different studies,20–23 were calculated.

Results

Patient characteristics and cefepime treatment

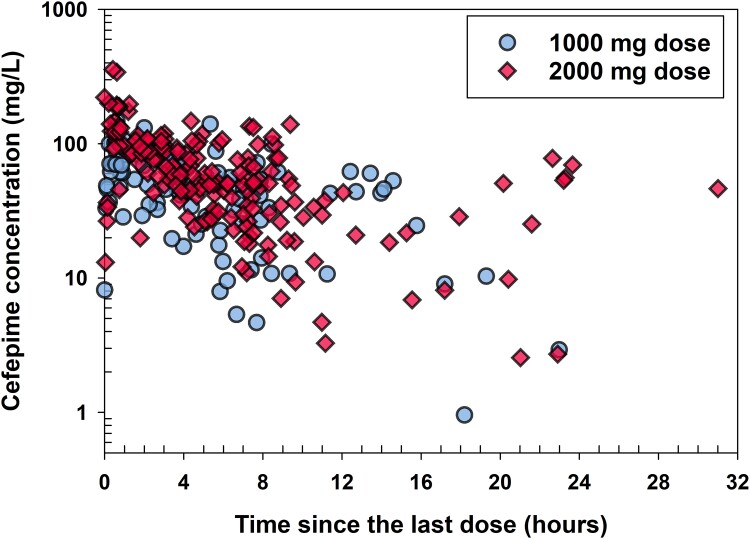

This prospective study enrolled 130 critically ill patients, including 12 subjects on CRRT (10 on continuous veno-venous haemodiafiltration and 2 on continuous veno-venous haemofiltration). A summary of patient demographic and clinical characteristics is provided in Table 1. The majority of cefepime doses were 2000 mg (n = 518) and the remaining 249 doses were 1000 mg. The durations of infusion were 0.083 h (18 doses), 0.167 h (58 doses), 0.5 h (663 doses), 1 h (6 doses) and 3 h (22 doses). A total of 278 cefepime plasma samples from 130 subjects were collected; none of the samples had cefepime concentration lower than LLOQ. The number of samples collected per subject ranged from one to eight, with most subjects having one sample (41%), two samples (41%), three samples (13.1%) or four samples (11.5%). Blood samples were collected both as part of routine clinical care, including morning laboratory blood sampling (where times are often standardized), and, more commonly, during line sampling for blood gases and other non-routine blood sampling. Therefore, there are no specific timepoints or collection times relative to cefepime dosing, and sampling varied by patient, by disease state and by day. As a result, there is minimal bias, relevant to timing, introduced using standard of care blood sampling. Figure 1 presents observed cefepime plasma concentrations over time since the last dose, which clearly displays that sample collection times were distributed through the entire cefepime dosing interval.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of study patients receiving cefepime therapy (N = 130)

| Characteristic | Median [IQR] or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65 [52–72] |

| Sex | 54 females (42%), 76 males (58%) |

| Race | 2 Asian (2%), 6 Black/African American (5%), 119 white (92%), 3 multiple (2%) |

| Ethnicity | 1 Hispanic (1%), 129 not Hispanic (99%) |

| Total body weight (kg)a | 90 [70–110] |

| Lean body weight (kg) | 58 [48–67] |

| CLCR, TBW (mL/min)b | 86 [52–126] |

| CLCR, LBW (mL/min)b | 54 [32–86] |

| Acute kidney injury | 45 (35%) |

| Sepsis | 45 (35%) |

| Septic shock | 34 (26%) |

| Hepatic function | 32 normal (25%), 27 not normal (21%), 71 missing (55%) |

| SOFA | 6 [4–9] |

| Mechanical ventilation | 65 [50%] |

Body weight was assessed at admission.

CLCR, TBW, creatinine clearance calculated according to the Cockcroft–Gault equation using total body weight; CLCR, LBW, creatinine clearance calculated according to the Cockcroft–Gault equation using lean body weight.

Figure 1.

Observed cefepime concentrations versus time since the last dose stratified by the doses. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Population PK modelling

Parameter estimation

Among several models tested, the best base structural model was found to be a two-compartment model with zero-order input and first-order elimination processes. Among various covariates evaluated, the following three significant covariates were identified: creatinine clearance calculated according to Cockcroft-gault equation using lean body weight (CLCR,LBW) on cefepime CLR, CRRT on cefepime total clearance (CLT), and total bodyweight on cefepime central volume of distribution (V1). Model development history for both base model as well as covariate models is provided in Tables S1 and S2. The estimates of the cefepime PK parameters from the final model are provided in Table 2. All model estimates were within the non-parametric 95% CI from the bootstrap analysis and were similar to the bootstrap median values.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates of the final cefepime population PK model

| Parameter | Unit | Population estimate | RSE (%) | Shrinkage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLR | L/h per 54 mL/min CLCR,LBW | 2.00 | 7.5 | — |

| CLCRRT | L/h | 1.64 | 14.8 | — |

| CLNR | L/h | 0.526 | 26.4 | — |

| CLT, nonCRRT | L/h | 2.53 | — | — |

| CLT, CRRT | L/h | 2.17 | — | — |

| V1 | L/90 kg TBW | 13.4 | 17.2 | — |

| V2 | L | 7.52 | 24.5 | — |

| Q | L/h | 12.0 | 35.2 | — |

| IIV CLT | — | 29.9% | 22.3 | 21.5 |

| IIV V1 | — | 65.4% | 37.4 | 42.2 |

| IIV V2 | — | 17.3% | 285.6 | 87.8 |

| CVCP | — | 22.4% | 20.3 | 23.0 |

| SDCP | mg/L | 6.44 | 52.6 | 23.0 |

CLR, renal clearance; CLCRRT, clearance by CRRT; CLNR, non-renal clearance; CLT, nonCRRT, total body clearance in subjects not on CRRT; CLT, CRRT, total body clearance in subjects on CRRT; V1, volume of distribution of the central compartment; V2, volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment; Q, distribution flow; CVCP, proportional residual error; SDCP, additive residual error; CLT, total clearance (i.e. CLT, nonCRRT for non-CRRT patients and CLT, CRRT for CRRT patients).

Goodness of model fitting

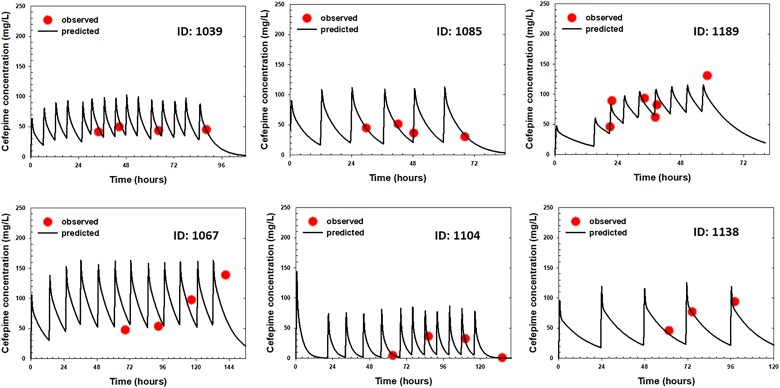

The time courses of observed versus individual predicted plasma concentrations of cefepime in six representative patients are presented in Figure 2. As shown in these plots, there is close agreement between the model-predicted cefepime concentrations and observed concentrations at various timepoints across different doses among different critically ill patients. In addition, goodness-of-fit plots (Figure S2) showed that the data were evenly distributed around the line of identity (Figure S2a and b) or the zero line (Figure S2c and d) without bias, indicating that the final model characterized cefepime PK adequately at both the individual and population levels and there was no significant bias in the model fit.

Figure 2.

Time courses of individual observed (symbols) versus individual predicted (lines) plasma cefepime concentrations in six representative ICU patients receiving cefepime standard of care. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

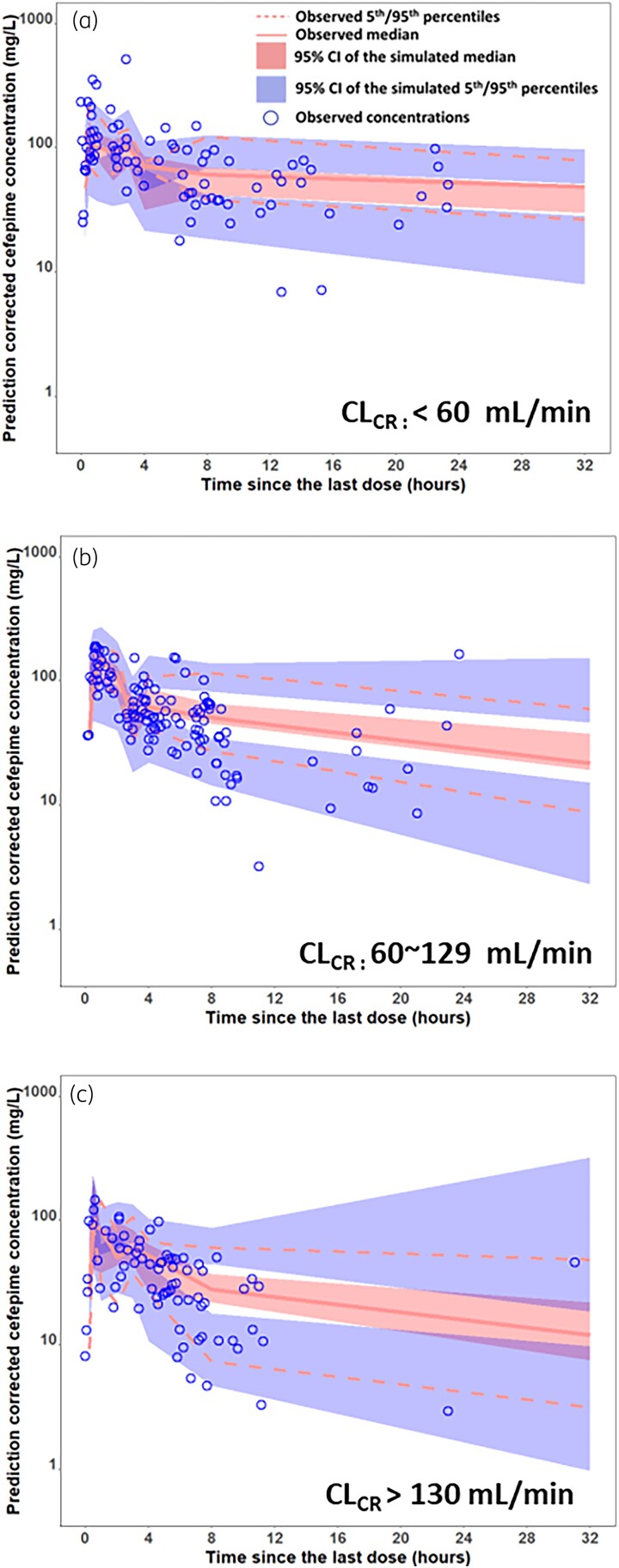

To evaluate the predictive performance of the final model, pcVPC plots, stratified by renal function, were performed. As shown in Figure 3, most of the observed concentrations were within the 90% prediction intervals from the simulation data for all pcVPC plots, indicating good predictive performance of the final model in each renal function category.

Figure 3.

Prediction-corrected visual predictive check (pc-VPC) of final cefepime final model stratified by creatinine clearance with (A) less than 60 ml/min, (B) 60-129 ml/min and (C) greater than 130 ml/min. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

PTA analysis

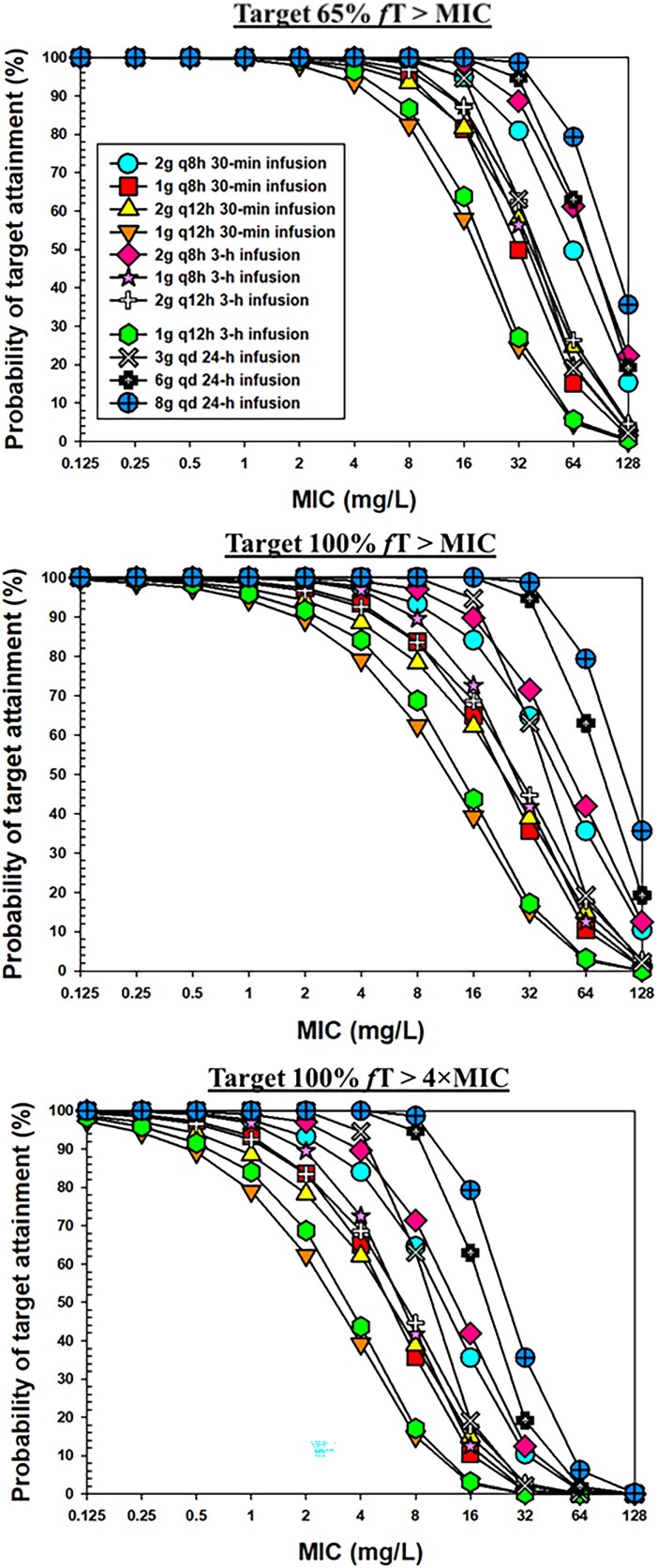

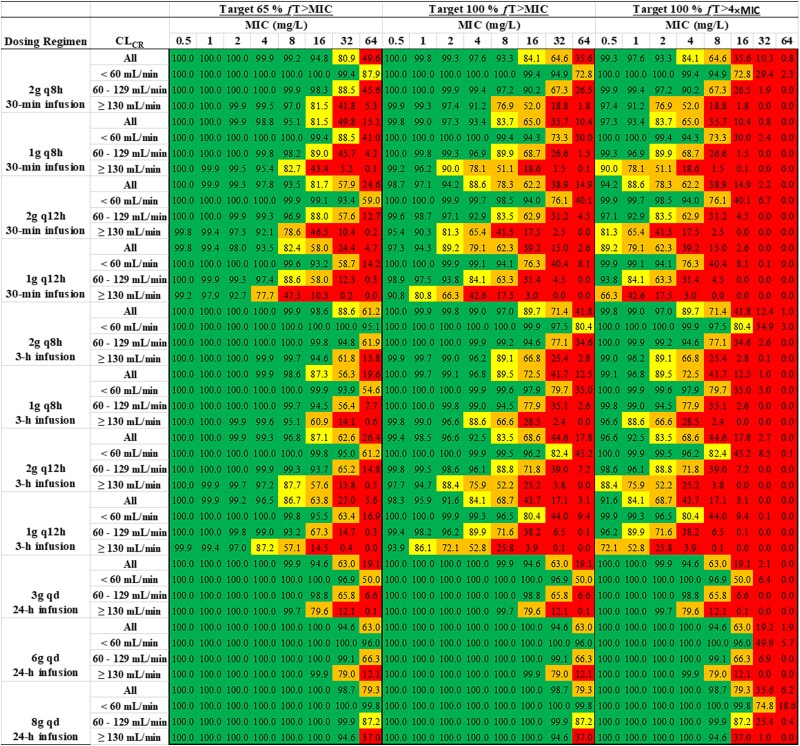

The PTA versus MIC profiles for different dosing regimens are shown in Figure 4. A heatmap of PTA of cefepime at different MIC values following different dose regimens in all subjects as well as subjects with different renal functions, with different PK/PD targets is shown in Figure 5. A PTA of ≥90% was considered satisfactory and coded with green colour. Table 3 lists the breakpoint values that can be reached following different cefepime dose regimens. For a 6 g daily dose scenario, we simulated data for three different dosing regimens: 2 g q8h as 0.5 h infusions; 2 g q8h as 3 h infusions; and 6 g per day continuous infusion. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 5, with target 100% fT > MIC, the dosing regimen of 2 g q8h as 0.5 h infusions could reach breakpoints of 32 mg/L, 16 mg/L and 4 mg/L in critically ill patients with CLCR <60 mL/min, 60–129 mL/min and ≥130 mL/min, respectively. With target 65% fT > MIC, following the same dose regimen, the breakpoint values were the same in the renally impaired group and normal renal function group but increased to 8 mg/L in patients with augmented renal function. With target 100% fT > 4×MIC, cefepime 2 g q8h as 0.5 h infusions reached the MIC breakpoint of 8 mg/L only in patients with renal impairment.

Figure 4.

PTA of cefepime versus MIC following different dosing regimens with the target of 65% fT > MIC (upper panel), 100% fT > MIC (middle panel) and 100% fT > 4×MIC (lower panel). This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of PTA of cefepime at different MIC values following different dose regimens in all subjects as well as subjects with different renal functions, with the PK/PD targets of 65% fT > MIC, 100% fT > MIC and 100% fT > 4×MIC (green, PTA ≥90%; yellow, PTA 80%–89%; orange, PTA 50%–79%; red, PTA <50%). This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Table 3.

Predicted cefepime breakpoints following different dose regimens in all subjects as well as subjects with different renal functions

| Cefepime breakpoints (mg/L) (i.e. the highest MIC at which ≥90% of the participants achieve targets) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dosing regimena | CLCR | Target 100% fT > MIC | Target 65% fT > MIC |

| 2 g q8h 30 min infusion | All | 8 | 16 |

| <60 mL/min | 32 | 32 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 16 | 16 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 4 | 8 | |

| 1 g q8h 30 min infusion | All | 4 | 8 |

| <60 mL/min | 16 | 16 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 4 | 8 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 1 | 4 | |

| 2 g q12h 30 min infusion | All | 2 | 8 |

| <60 mL/min | 16 | 32 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 4 | 8 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 1 | 4 | |

| 1 g q12h 30 min infusion | All | 1 | 4 |

| <60 mL/min | 8 | 16 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 2 | 4 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 0.5 | 2 | |

| 2 g q8h 3 h infusion | All | 8 | 16 |

| <60 mL/min | 32 | 64 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 16 | 32 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 4 | 16 | |

| 1 g q8h 3 h infusion | All | 4 | 8 |

| <60 mL/min | 16 | 32 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 8 | 16 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 2 | 8 | |

| 2 g q12h 3 h infusion | All | 4 | 8 |

| <60 mL/min | 16 | 32 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 4 | 16 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 1 | 4 | |

| 1 g q12h 3 h infusion | All | 2 | 4 |

| <60 mL/min | 8 | 16 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 2 | 8 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 0.5 | 2 | |

| 3 g q24h 24 h infusion | All | 16 | 16 |

| <60 mL/min | 32 | 32 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 16 | 16 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 8 | 8 | |

| 6 g q24h 24 h infusion | All | 32 | 32 |

| <60 mL/min | 64 | 64 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 32 | 32 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 16 | 16 | |

| 8 g q24 24 h infusion | All | 32 | 32 |

| <60 mL/min | 64 | 64 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 32 | 32 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 32 | 32 | |

For each dosing regimen, 6500 virtual subjects were simulated, including 2100 subjects with CLCR <60 mL/min, 2850 subjects with CLCR between 60 and 129 mL/min, and 1550 subjects with CLCR >130 mL/min.

With target 100% fT > MIC, following the same dosing regimen (2 g q8h) but delivered as 3 h infusions, the breakpoints that could be reached in the whole population and subpopulations with different renal functions are similar to those with 2 g q8h as 0.5 h infusions. In contrast, 6 g/day continuous infusion could reach a breakpoint of at least 32 mg/L except in subjects with CLCR >130 mL/min for whom the breakpoint was 16 mg/L. The detailed results of other dose regimens can be found in Figures 4 and 5 and Table 3.

Table 4 shows the percentage of subjects with Ctrough exceeding four different thresholds.

Table 4.

Predicted percentage of subjects with cefepime Ctrough values exceeding four different thresholds

| Predicted percentage of subjects with Ctrough greater than four different thresholds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosing regimena | CLCR | 20 mg/L | 35 mg/L | 49 mg/L | 63.2 mg/L |

| 2 g q8h 30 min infusion | All | 79.1 | 61.2 | 47.0 | 36.1 |

| <60 mL/min | 98.9 | 93.6 | 84.1 | 73.4 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 85.6 | 62.9 | 42.2 | 27.3 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 40.4 | 14.2 | 5.5 | 1.8 | |

| 1 g q8h 30 min infusion | All | 56.2 | 31.5 | 18.2 | 10.6 |

| <60 mL/min | 90.9 | 68.0 | 46.6 | 30.4 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 55.4 | 21.1 | 7.1 | 1.6 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 10.6 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 2 g q12h 30 min infusion | All | 55.3 | 35.2 | 23.2 | 15.3 |

| <60 mL/min | 90.7 | 71.8 | 54.9 | 40.9 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 53.4 | 26.4 | 12.3 | 4.8 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 10.8 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| 1 g q12h 30 min infusion | All | 30.1 | 12.9 | 6.2 | 2.8 |

| <60 mL/min | 65.5 | 35.3 | 18.6 | 8.6 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 19.8 | 3.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 2 g q8h 3 h infusion | All | 85.3 | 68.0 | 54.2 | 42.5 |

| <60 mL/min | 99.6 | 96.8 | 90.4 | 80.8 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 91.4 | 72.8 | 52.9 | 35.7 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 54.7 | 20.4 | 7.7 | 3.2 | |

| 1 g q8h 3 h infusion | All | 63.4 | 37.4 | 21.4 | 12.8 |

| <60 mL/min | 95.0 | 75.4 | 53.3 | 35.8 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 66.2 | 29.0 | 9.5 | 2.9 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 15.2 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 2 g q12h 3 h infusion | All | 62.1 | 41.3 | 27.7 | 18.0 |

| <60 mL/min | 94.0 | 79.2 | 61.7 | 45.7 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 63.5 | 34.5 | 17.4 | 7.4 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 16.3 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | |

| 1 g q12h 3 h infusion | All | 34.6 | 14.3 | 6.5 | 3.2 |

| <60 mL/min | 71.6 | 38.2 | 19.0 | 9.9 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 25.5 | 4.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 3 g qd 24 h infusion | All | 87.5 | 56.9 | 33.7 | 19.6 |

| <60 mL/min | 100.0 | 94.4 | 73.2 | 51.3 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 95.1 | 56.1 | 22.6 | 6.8 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 56.5 | 7.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | |

| 6 g qd 24 h infusion | All | 99.6 | 92.5 | 78.4 | 63.8 |

| <60 mL/min | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.5 | 96.4 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 100.0 | 98.3 | 87.2 | 67.5 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 98.5 | 71.7 | 33.9 | 12.8 | |

| 8 g qd 24 h infusion | All | 100.0 | 97.9 | 90.7 | 79.9 |

| <60 mL/min | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.8 | |

| 60–129 mL/min | 100.0 | 99.9 | 96.8 | 87.9 | |

| ≥130 mL/min | 99.9 | 91.5 | 66.8 | 38.5 | |

For each dosing regimen, 6500 virtual subjects were simulated, including 2100 subjects with CLCR <60 mL/min, 2850 subjects with CLCR between 60 and 129 mL/min, and 1550 subjects with CLCR >130 mL/min.

Discussion

In our population PK analysis, the PK of cefepime was best characterized by a two-compartment model with zero-order input and first-order elimination; this model structure is generally in good agreement with literature reports, in which a two-compartmental model was reported in most cefepime population PK reports in critically ill patients,7,8,13,24 except for studies conducted by Carlier et al.12 and Roos et al.14 where the data were characterized by a one-compartment model and a three-compartment model, respectively. In our analysis, the Vss of cefepime [i.e. V1 of 13.4 L per 90 kg total body weight (TBW) + V2 of 7.52 L] was estimated to be ∼21 L; this estimated low volume of distribution is expected considering that cefepime is hydrophilic and mainly limited to the extracellular space. Our model-estimated V1 and/or Vss values are generally comparable to those literature-reported values.13,16,24 For example, the V1 of cefepime was estimated to be 13.85 L per 70 kg bodyweight in a population PK study using the largest dataset thus far (N = 680).16 The estimated V1 of cefepime was only 5.74 L in a study conducted by Roos et al.14 Because this value was estimated from a three-compartment model using data collected from IV bolus (3 min infusion instead of 30 min or longer infusion used in other studies) where a very rapid initial distribution was captured, a head to head comparison on V1 may not be appropriate. The Vss (i.e. V1 + V2 + V3) in that study was estimated to be 22.6 L,14 which is in close agreement with the Vss estimated in our study (i.e. 21 L). Regarding cefepime clearance, results from our model showed that, for patients not on CRRT, the total clearance was 2.53 L/h, with about 79% of the dose being eliminated via the renal route; this is consistent with the existing knowledge of cefepime being primarily eliminated through renal excretion. Among various covariates evaluated, creatinine clearance (CLCR, LBW) and TBW were identified to be significant covariates, which is consistent with literature reports.8,14,16

In addition to CLCR, LBW and TBW, various other covariates were evaluated, but none of these covariates was identified as significant (i.e. none of them can further reduce the unexplained IIV). Because these pathophysiological changes are often dynamic and complex, their net impact on drug PK could be difficult to evaluate. Therefore, it is not surprising that they are not identified as significant covariates. Because the complex pathophysiological changes in critically ill patients can lead to variable PK of cefepime that cannot be fully addressed by incorporating renal function and bodyweight in the model, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) coupled with a Bayesian predictive model, which has been implemented for aminoglycosides and vancomycin,25,26 may represent a valuable tool for optimizing the dosing regimen of cefepime for patients with severe infection, especially unstable critically ill patients.

After the final population PK model was established for cefepime, we performed comprehensive simulations to predict the probability of target attainment of cefepime in critically ill patients with different renal functions who receive different dosing regimens. Overall, our simulation data showed that, following the same dosing regimen, prolonged (3 h) infusions did not provide significant improvement on target attainment compared with the traditional intermittent 0.5 h infusions, although 3 h infusions did result in two-fold higher breakpoints in certain subpopulations and/or for some PK/PD targets. Most breakpoints remained the same between these two infusion strategies; this trend was observed for all four dosing regimens involving intermittent infusions (i.e. 1 g q12 h, 1 g q8h, 2 g q12h and 2 g q8h). Based on our simulation results, it seems that there may be only a marginal advantage gained by switching from an infusion duration of 0.5 to 3 h when cefepime is administered in an intermittent dosing regimen.

In contrast, for a given daily dose continuous infusion provided much higher breakpoint coverage than either 0.5 h or 3 h intermittent infusions. For example, with a 3 g daily dose continuous infusion reached a breakpoint of 16 mg/L for a target of 100% fT > MIC, which was four-fold higher than the breakpoint of 4 mg/L reached following 1 g q8h administered as either 0.5 h or 3 h intermittent infusions. The same trend was observed when 6 g/day continuous infusion was compared with 2 g q8h administered as either short or prolonged intermittent infusions. Following continuous infusion, when the daily dose was increased from 3 to 6 g, the breakpoints doubled (e.g. 16 mg/L versus 32 mg/L in all subjects with target 100% fT > MIC). However, a further daily dose increase did not bring additional benefit on breakpoint coverage; 8 g/day continuous infusion resulted in essentially the same breakpoints as 6 g/day continuous infusion, except for subjects with augmented renal function. In addition, following continuous infusion, a daily dose of 3 g resulted in higher probabilities of target attainment and achievement of higher breakpoints than those from a 6 g daily dose administered as short-term infusions. These simulation results are encouraging. They deliver the following important messages: i) continuous infusion may represent a promising strategy for cefepime treatment in critically ill patients based on its potential to greatly increase probabilities of target attainment compared with short and prolonged intermittent infusions; ii) following continuous infusion, daily doses higher than 6 g may not be necessary because they bring little additional benefit; and iii) following continuous infusion, a daily dose of 3 g can achieve higher breakpoint coverage than the higher daily dose regimen (2 g q8h, 0.5 h) commonly used in our study sites.

Our simulation data clearly indicate that continuous infusion is a better strategy than short and prolonged intermittent infusions for critically ill patients. A natural follow-up question is ‘What is the ideal daily dose following continuous infusion?’ With a target of 100% fT > MIC, 3 g/day continuous infusion could reach breakpoints of 32 mg/L, 16 mg/L and 8 mg/L in critically ill patients with CLCR <60 mL/min, 60–129 mL/min and ≥130 mL/min, respectively. The breakpoint values are doubled when the daily dose increased from 3 to 6 g. However, we should keep in mind that the probability of achieving potentially toxic levels is also increased. Cefepime is known to have a relatively narrow therapeutic window compared with other β-lactams—a recently advocated threshold for cefepime toxicity was 35 mg/L,20 which is ≤ 2× the resistant breakpoint of several less sensitive organisms. When both target attainment and potential for toxicity are considered, it seems that 3 g/day continuous infusion in general is a better dosing regimen than 6 g/day continuous infusion. Please note that our recommendations are for a critically ill patient population only; continuous infusion may not be easily adopted in other non-critically ill patient populations.

Prior to 2020, the published cefepime population PK reports all have small sample size (N ranges from 13 to 41).7,8,12–14,24 Recently, Peloquin’s group published two elegant cefepime population PK reports15,16 with much larger sample size (N = 266 in one study and N = 680 in the other study) using retrospective data in which a considerable portion of the data were peak and trough concentrations obtained from TDM. Compared with the existing reports, the strength of our study is that it is a prospective and opportunistic study conducted in a relatively large population (N = 130). Due to the opportunistic nature of the study, all samples were collected randomly (Figure 2). Accordingly, the data obtained spread out the whole time since last dose time window (Figure 1), allowing for robust population PK analysis. Also because of the relatively large sample size, we got the opportunity to thoroughly evaluate the impact of various covariates on cefepime disposition. Although we failed to identify any additional significant covariate (other than renal function and bodyweight) to explain the remaining high intersubject variability, this negative result itself is valuable because it highlights the importance of performing TDM for individualized therapy. Even though we proposed a number of empirical dosing strategies based on our PTA simulated work, it is worth pointing out that those empirical dosing regimens only represent a strategy for initial dose selection, and dose regimen optimization may still be needed once the TDM data are available later on.

Our study has a few limitations. First, clinical outcome was not evaluated in our study. Second, adverse effect data were not collected in our study. It has been reported that cefepime has a relatively narrow therapeutic window compared with other β-lactams. Different cefepime Ctrough thresholds, including 20 mg/L, 35 mg/L, 49 mg/L and 63.2 mg/L, have been proposed among different studies.20–23 Because we did not collect adverse effect data in the current study, we could not validate or confirm the Ctrough thresholds reported in the literature. Because most studies evaluating cefepime toxicity were retrospective in nature without well-defined diagnosis criteria, it is unclear which of these reported Ctrough thresholds is reliable and should be implemented. Nevertheless, we performed simulation and estimated the percentage of subjects with Ctrough exceeding these four literature-reported thresholds. Although information in Table 4 cannot be used in decision making at this point, it may serve as a useful reference in the future for rational dose regimen selection once an appropriate Ctrough threshold is identified.

In conclusion, population PK modelling was successfully performed to quantitatively characterize the PK of cefepime in critically ill patients with various disease conditions and various renal functions. Creatinine clearance and body weight were identified to be significant covariates. Comprehensive Monte Carlo simulation data showed that prolonged 3 h infusion does not provide significant improvement on target attainment compared with the traditional intermittent 0.5 h infusion. Continuous infusion may represent a promising strategy for cefepime treatment in critically ill patients based on its potential for greatly increasing PTAs as well as higher breakpoint coverage than short-term infusions. To balance the target attainment and potential neurotoxicity, 3 g/day continuous infusion appears to be a better dosing regimen than 6 g/day continuous infusion. Our modelling and simulation work provide a solid foundation for dose regimen selection of cefepime in critically ill patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank EMMES, the University of Iowa VTEU study team and Vanderbilt University VTEU study team for their efficient and conscientious management of this study.

Contributor Information

Guohua An, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Experimental Therapeutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

C Buddy Creech, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Nan Wu, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Experimental Therapeutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Roger L Nation, Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

Kenan Gu, Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Rockville, MD, USA.

Demet Nalbant, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Experimental Therapeutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Natalia Jimenez-Truque, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

William Fissell, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Pratish C Patel, Department of Pharmaceutical Services, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Nicholas Fishbane, The Emmes Company, LLC, Rockville, MD, USA.

Amy Watanabe, The Emmes Company, LLC, Rockville, MD, USA.

Stephanie Rolsma, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Carl M J Kirkpatrick, Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

Cornelia B Landersdorfer, Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

Patricia Winokur, Division of Infectious Diseases, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health through the Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit contract HHSN272200800008C.

Transparency declarations

None to declare

Supplementary data

Figures S1 and S2 and Tables S1and S2 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Kessler RE, Bies M, Buck RE et al. Comparison of a new cephalosporin, BMY 28142, with other broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1985; 27: 207–16. 10.1128/AAC.27.2.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okamoto MP, Nakahiro RK, Chin A et al. Cefepime clinical pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet 1993; 25: 88–102. 10.2165/00003088-199325020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pais GM, Chang J, Barreto EF et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cefepime. Clin Pharmacokinet 2022; 61: 929–53. 10.1007/s40262-022-01137-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Craig WA. Interrelationship between pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in determining dosage regimens for broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 1995; 22: 89–96. 10.1016/0732-8893(95)00053-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roberts JA, Paul SK, Akova M et al. DALI: defining antibiotic levels in intensive care unit patients: are current beta-lactam antibiotic doses sufficient for critically ill patients? Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58: 1072–83. 10.1093/cid/ciu027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abdul-Aziz MH, Lipman J, Roberts JA. Identifying “at-risk” patients for sub-optimal beta-lactam exposure in critically ill patients with severe infections. Crit Care 2017; 21: 283. 10.1186/s13054-017-1871-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tam VH, McKinnon PS, Akins RL et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cefepime in patients with various degrees of renal function. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003; 47: 1853–61. 10.1128/AAC.47.6.1853-1861.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nicasio AM, Ariano RE, Zelenitsky SA et al. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose, prolonged-infusion cefepime in adult critically ill patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 1476–81. 10.1128/AAC.01141-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lodise TP, Lomaestro BM, Drusano GL et al. Application of antimicrobial pharmacodynamic concepts into clinical practice: focus on beta-lactam antibiotics: insights from the Society of Infectious Diseases pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy 2006; 26: 1320–32. 10.1592/phco.26.9.1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing—Twenty-Fourth Edition: M100. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing—Thirty-Second Edition: M100. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carlier M, Taccone FS, Beumier M et al. Population pharmacokinetics and dosing simulations of cefepime in septic shock patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015; 46: 413–19. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jonckheere S, De Neve N, Verbeke J et al. Target-controlled infusion of cefepime in critically ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 64: e01552-19. 10.1128/AAC.01552-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roos JF, Bulitta J, Lipman J et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic rationale for cefepime dosing regimens in intensive care units. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 58: 987–93. 10.1093/jac/dkl349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Al-Shaer MH, Neely MN, Liu J et al. Population pharmacokinetics and target attainment of cefepime in critically ill patients and guidance for initial dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64: e00745-20. 10.1128/AAC.00745-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alshaer MH, Goutelle S, Santevecchi BA et al. Cefepime precision dosing tool: from standard to precise dose using nonparametric population pharmacokinetics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022; 66: e0204621. 10.1128/aac.02046-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. D’Cunha R, Bach T, Young BA et al. Quantification of cefepime, meropenem, piperacillin, and tazobactam in human plasma using a sensitive and robust liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method, part 1: assay development and validation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e00859-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. D’Cunha R, Bach T, Young BA et al. Quantification of cefepime, meropenem, piperacillin, and tazobactam in human plasma using a sensitive and robust liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method, part 2: stability evaluation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e00861-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. EUCAST . Clinical breakpoints—breakpoints and guidance. 2023. https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/

- 20. Payne LE, Gagnon DJ, Riker RR et al. Cefepime-induced neurotoxicity: a systematic review. Crit Care 2017; 21: 276. 10.1186/s13054-017-1856-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huwyler T, Lenggenhager L, Abbas M et al. Cefepime plasma concentrations and clinical toxicity: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017; 23: 454–9. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lau C, Marriott D, Schultz HB et al. Assessment of cefepime toxicodynamics: comprehensive examination of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic targets for cefepime-induced neurotoxicity and evaluation of current dosing guidelines. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2021; 58: 106443. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vercheval C, Sadzot B, Maes N et al. Continuous infusion of cefepime and neurotoxicity: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jonckheere S, De Neve N, De Beenhouwer H et al. A model-based analysis of the predictive performance of different renal function markers for cefepime clearance in the ICU. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71: 2538–46. 10.1093/jac/dkw171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pea F, Furlanut M, Negri C et al. Prospectively validated dosing nomograms for maximizing the pharmacodynamics of vancomycin administered by continuous infusion in critically ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 1863–7. 10.1128/AAC.01149-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matthews I, Kirkpatrick C, Holford N. Quantitative justification for target concentration intervention–parameter variability and predictive performance using population pharmacokinetic models for aminoglycosides. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 58: 8–19. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02114.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.