Abstract

Maternal morbidity and mortality remain high among women who did not attend antenatal care (ANC). Antenatal care is one of the interventions given to pregnant women to detect existed problems or problems that can develop during pregnancy, which harm the health of pregnant women and fetuses. In Ethiopia, however, there is limited evidence that revealed the effect of antenatal depression on ANC service utilization. Hence, this study aimed to see the effect of antenatal depression on ANC visits among women in urban northwest Ethiopia. A population-based, prospective cohort study was done from June 2019 to March 2020. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale was administered to 970 women in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy to screen for antenatal depression. Additional data were collected on ANC visits, the mother’s socio-demographic, obstetric, clinical, psychosocial, and behavioral factors. A logistic regression model was used to adjust confounders and determine associations between antenatal depression and inadequate ANC visits. The cumulative incidence of inadequate ANC visits was 62.58% (95% CI: 59.43, 65.63). The cumulative incidence of inadequate ANC visits among depressed pregnant women was 75% as compared to 56% in non-depressed. The incidence of inadequate ANC visits in the exposed group due to antenatal depression was 25.33%. After multivariable analysis, antenatal depression at the second and third trimesters of pregnancy remained a potential predictor of inadequate ANC visits (AOR = 1.96: (95% CI 1.22, 3.16)). In addition, antenatal depression, long travel time for ANC visits (AOR = 1.83 (95% CI 1.166, 2.870)), and late initiation of ANC visits (AOR = 2.20 (95% CI 1.393, 3.471)) were the predictors of inadequate ANC visits as compared to their counterpart. This study suggested that antenatal depression affects ANC visits in Ethiopian urban settings. Therefore, early detecting and treating depression symptoms during the antenatal period reduced significantly the impacts of depression on the health of the mother and fetus.

Subject terms: Human behaviour, Health care, Risk factors, Psychiatric disorders

Introduction

Maternal well-being and survival are not only crucial to the health of the mother but also to the newborn’s health and development. The global maternal mortality ratio(MMR) estimate in 2020 was 152 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births from complications arising from pregnancy and childbirth1. The lifetime risk of maternal mortality due to pregnancy complications is higher in Sub-Saharan Africa than in other parts of the world; because of inaccessibility to ANC clinics, risk of poverty, and HIV infection2. In Ethiopia, despite the existence of interventions that could prevent maternal morbidity, death, and disability during pregnancy and childbirth, the levels of maternal mortality are the highest in the world. In Ethiopia, the maternal mortality ratio from preventable pregnancy-related complications remains high (255 per 100,000 live births) until 20201.

Antenatal care is the health care given to pregnant women to detect problems that existed before or that occur during pregnancy, which harm the health of pregnant women and the fetuses3. To maintain a healthy pregnancy for mother and baby, women required a positive pregnancy experience (including preventing or treating risks, illness, and death) with good quality antenatal care4. Studies showed that maternal antenatal care follow-up during pregnancy is a significant determinant of maternal morbidity and mortality5. Timely and appropriate antenatal care (ANC) visits are the cornerstone to reduce morbidity and mortality of pregnant women and newborns3,5. A cohort study revealed that, having four or more ANC visits reduced postpartum haemorrhage, early neonatal death, preterm labour, and low birth weight by 81.2%, 61.3%, 52.4%, and 46.5%, respectively6.

World Health Organization (WHO) recommended a minimum level of antenatal care visits should consist of four visits in one pregnancy to reduce the risk of pregnancy and obstetric complications7–9. Globally, 85% of pregnant women attend at least one ANC visits with a skilled health professional and 58% attend at least 4 ANC visits10; in Ethiopia, the Mini Demographic Health Survey (EMDHS) 2019 reported that the proportion of pregnant women who attended four or more ANC visits was only 43%11. The research finding indicates that antenatal care services are available to all pregnant women in low and middle-income countries with high-quality and minimal cost or no cost program to encourage adequate ANC use12, but studies in Yemen13 and Ethiopia14,15 revealed that there is only a small number of pregnant women receiving four or more antenatal care visits. These acts are alarming to examine the critical factors influencing the uptake of ANC services. Marital status, maternal age, lack of time to attend, and women’s economic status were significant predictors of utilization of maternity care16. Education status, marital status, residence, parity, and religion were potential determinants of health care utilization17. Other important factors that affected the utilization of maternity care services were: the high cost of antenatal care services, long waiting times, and poor staff attitude13. A study done in Rwanda showed, the age of participants and poor social support were predictors of underutilization of ANC services18.

Currently, there is increasing evidence that revealed antenatal depression is a significant public health problem in low- and middle-income countries (LAMICs)19. Depression is among the most prevalent mental health problems during pregnancy, affecting about one in four women during their lifetime20. The adverse effects of antenatal depression on prolonged labor, peripartum and postpartum complications, non-vaginal delivery, and newborn illness have been well documented21. Antenatal depression has a negative effect on ANC service utilization and thereby contributes to increased perinatal complications and maternal mortality. Studies conducted in the USA showed that antenatal depression was significantly associated with poor prenatal care utilization22–24. There is also evidence from high-income settings that antenatal depression is associated with inadequate antenatal care25. A study in the East Asia region revealed that antenatal depression negatively affected pregnant women's antenatal care visits26. On the contrary, a study done in Minnesota revealed that inadequate prenatal care utilization was significantly associated with a past psychiatric history, but not with a current antenatal psychiatric diagnosis27. Studies in Africa showed that no association was found between antenatal depression and antenatal care attendance21,28.

In Ethiopia, a population-based study indicated that pregnant women with depressive symptoms had an increased risk of having more non-scheduled ANC visits, but not with the adequacy of ANC visits29. However, studies examining the effect of antenatal depression on ANC visits have been scanty in number. There is a clear gap that showed the effect of antenatal depression on antenatal care use, particularly in Ethiopia where maternal mortality is high. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the effect of antenatal depression on ANC visits in northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and settings

We conducted a community-based prospective cohort study at Debre Tabor and Woreta towns from June 2019 to March 2020 in the South Gondar zone, northwest Ethiopia. According to the South Gondar zonal catchment profile, the estimated total population of Debre Tabor town was 84,382, of which 40,753 are females. While Woreta town has an estimated population of 41,668, of which 20,507 are females. The estimated number of pregnant women per year in Debre Tabor and Woreta towns were 2844 and 1404 respectively30. In these towns, the individuals obtain basic health care services from one government-operated referral hospital, five health centers, and ten private health institutions during the data collection period.

Health Extension Workers (HEWs) are responsible for performing prevention and promotion activities, identifying and monitoring pregnant mothers, and maintaining up-to-date maternal records in each Kebele (the lowest administrative unit or village in Ethiopia). The previous year's report of the district health office showed that the proportions of pregnant women who were using antenatal care services at Debre Tabor and Woreta towns were estimated to be 75% and 64%, respectively30.

Sample size

The sample size was estimated using the double population proportion formula by considering the exposed and non-exposed ratio of 1:2 (exposed are those who are depressed, and non-exposed are those who are not depressed), 95% level of confidence, 80% power, and 10% non-response rate.

Cohort recruitment and eligibility

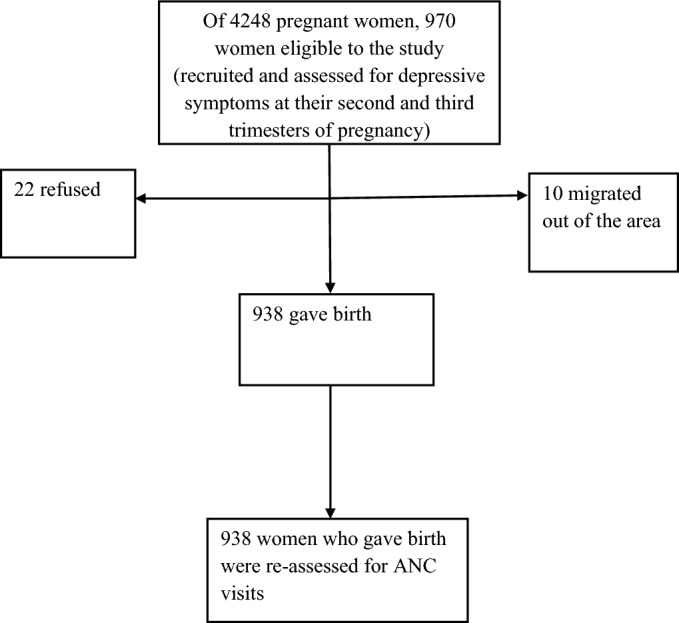

All eligible and consenting women were recruited into the cohort. Pregnant women who were in their 2nd and 3rd trimesters, living in Debre Tabor and Woreta towns for at least the preceding six months, and without any cognitive or hearing impairment during the study period were eligible for this study. The data collectors were interviewed through home-to-home visits and declared untraceable after three recruiting visits considered as unsuccessful. Totally, 970 women were identified within five months (June 2019–October 2019) and followed up to March 2020. Potentially all cohort pregnant women who gave birth were eligible (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of recruited pregnant women and the outcome of inadequate ANC visits.

Data quality management

A data collection tool was pilot tested in a similar context. The data collectors were Diploma and BSc holders in nursing who had experience in data collection in the field. Before the commencement of data collection, the data collectors and supervisors took comprehensive training with practical exercises for two days that help them to understand the contents of the questionnaire, objectives, and ethical issues relevant to the study. Similarly, Master’s degree holder supervisors were assigned during data collection. Besides, the principal investigator, field supervisors made regular on-site supervision during the data collection periods. The questionnaires were rechecked by the supervisors and the principal investigator for completeness and consistency in a weekly based face to face meetings and telephone communications. Accordingly, incomplete or incorrectly filled questionnaires were identified and managed. For the data entry, templates with proper check codes were designed and employed to minimize data entry errors. The experts who did the data entry had also ample experience on using the Epi-data software. Besides, double entry of the data, 10% of the questionnaires were done to detect and manage the mistakes likely to occur during data entry. Also, the principal investigator randomly cross-checked the correctness of the data entered to the Epi-data software and the data captured in the questionnaire.

Measurement

Primary exposure

Antenatal depression was the primary exposure variable; which was assessed using the EPDS. The EPDS has a sensitivity, specificity, and internal reliability Cronbach's alpha of 78.9%, 75.3%, and 0.71 respectively; from a validation study in Ethiopia31. It includes ten items with a Likert scale of responses scored from 0 to 3 to a maximum score of 30; which was then coded as Yes1 if there is depression (scores ≥ 12) and No (0) if otherwise (< 12 scores) to indicate scores that are likely to suggest depressive disorder.

EPDS is a preferable scale over other depression scales to screen for depression during pregnancy; because it removes the physical symptoms of depression associated with pregnancy32. In these local kebeles, a woman with suicidal ideation was referred to a psychiatric unit in Debre Tabor Hospital for further assessment and appropriate treatment.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome variable was inadequate ANC visits. ANC visits were categorized as inadequate (< four visits) and adequate (≥ four visits) visits. ANC visits were obtained by interviewing women after delivery33.

Potential confounding variables

The most common potential confounding factors were long travel time for ANC visits (categorized as ‘Yes’ if the time takes greater than or equal to 30 min, or ‘No’ if otherwise), threatening life events, lack of time for ANC visit, social support, intimate partner violence, waiting a long time for ANC service (categorized as ‘Yes’ if the time takes greater than or equal to 120 min or ‘No’ if otherwise, initiation of ANC visit (If a mother starts ANC visit within 3 months of pregnancy period = early initiation). In addition, any chronic medical condition, integration of ANC influence ANC service, history of complications current pregnancy, history of alcohol misuse, socio-demographic and economic variables, including marital status, wealth index, and level of education also assessed.

Experiences of stressful life events during the six months before the assessment was assessed using the List of Threatening Experiences (LTE). The scale contains twelve items and includes questions about death, illness, conflicts, and loss of property34. The presence of LTE ascertained by the presence of at least one or more LTE. The test–retest reliability of the LTE was good, with a Kappa of 0.61–0.8735.

The Oslo Social Support Scale (OSSS-3)36 was used to measure maternal social support during pregnancy. The level of social support classified as “poor support”3–8, “moderate support”9–11, and “strong support”12,14 scores. The OSSS-3 consists of three items assessing the number of close intimates, perceived level of concern from others, and perceived ease of getting help from neighbors. The OSSS-3 has good convergent and predictive validity37. Both the LTE-12 and the OSSS-3 have been used in a population-level study in Ethiopia38.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) during pregnancy was assessed by asking three questions related to emotional, physical, and sexual violence. The presence of IPV was ascertained by the presence of at least one type of IPV39. The history of physician-diagnosed chronic medical conditions, including cardiac disease, hypertension counted for each woman, recorded as “No” for those without any chronic medical conditions, and “Yes” otherwise History of current pregnancy complications: anemia, hypertension, edema, Antepartum haemorrhage (APH) were counted for each woman and recorded as “yes/no.” Alcohol use was assessed using the four-item scale; the Fast Alcohol Screening Test (FAST)40, which ranges from 0 to 16. Hazardous drinking refers to a score of three or more on a FAST scale40.

Analysis strategy

We used Stata software (version 14) for analysis. We run descriptive statistics for all study variables. Percentage values, with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals were used to summarize categorical variables. We used the odds ratio to measure the effect of antenatal depression on ANC visits. We carried out univariate logistic regression analyses for each risk factor to identify possible predictors associated with inadequate ANC visits. During univariate analysis, variables were selected for multivariable analysis if the p-value was < 0.2. The difference was deemed to be significant if p < 0.05. The total number of losses to follow up was 32 (3.2%). We also used a complete case analysis as it was suggested less than 5% lost to follow-up was with little concern41,42. We used a principal component analysis for the wealth index and checked its assumption of whether it fulfills or not. There were 50 or more valid cases, a case-to-variable ratio of at least 5–1, two or more correlations of 0.30 or higher, a sampling adequacy measure of at least 0.50 for each variable, an overall sampling adequacy measure of at least 0.50, and a probability of the Bartlett test of sphericity less than the level of significance for each variable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained ethical approval from the Amhara region public health institute and Institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Gondar. We received permission from Debre Tabor and Woreta towns’ health department administrat office. All methods were carried out in accordance with the Helsinki declaration guidelines and regulations. Before we want to collect the data, participation information sheet read for all participants and we obtained written informed consent from all participants. The participants were told that participation is fully voluntary and they had the right to refuse, withdraw at any time and refrain from answering any question that they don’t want to without any reprisal. Information gathered from the participants was stored in a secured cabinet by the principal investigator. Besides these, the data obtained from participants kept confidential. Those women who were expressing sever suicidal ideation referred to Debre Tabor referral Hospital psychiatry unit for further diagnosis and appropriate management. The decision for referral was made by the principal investigator based on the review of all women who were expressing suicidal ideation.

Result

The detailed recruitment profile of women showed in the flow chart in Fig. 1. Between June 2019 and October 2019, 970 pregnant women were eligible to participate. Of this thirty-two (3.3%), declined to participate because of refusal to participate, and moving from the area. Finally, 938 women were included in the analysis, with a response rate of 96.7%. Our study revealed that the cumulative incidence of inadequate ANC visits was 62.58%. Of 938 participants, 858 (91.47%) women attended at least one antenatal care (ANC). However, from those who attended antenatal care services, one-fourth of 173 (20.16%) participants made their first visit during their first trimester. Of these, only 351(37%) of women had four or more ANC visits during their last antenatal period. The mean (± SD) of ANC visits was 3.1 ± 1.3, ranging from 0 to 6.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

Out of the 938 mothers, 403 (43%) of them were found between the ages of 25–29 years. The mean (± SD) age was 27.1 ± 4.8 years. In this study, women who were married was 860 (92%). Regarding the level of education, 797 (85%) of the participants had formal education (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of Socio-demographic factors among pregnant women at Debre Tabor and Woreta towns, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 938) | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| ≤ 19 | 34 | 3.63 |

| 20–24 | 238 | 25.37 |

| 25–29 | 403 | 42.96 |

| 30–34 | 179 | 19.08 |

| > 35 | 84 | 8.96 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 869 | 92.64 |

| Muslim | 56 | 5.97 |

| Protestant | 13 | 1.39 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Amhara | 926 | 98.72 |

| Tigre | 12 | 1.28 |

| Education | ||

| Unable to read and write | 121 | 12.91 |

| Able to read and write | 20 | 2.13 |

| Primary | 241 | 25.69 |

| High school | 262 | 27.93 |

| Diploma and above | 294 | 31.34 |

| Occupation | ||

| Housewife | 483 | 51.49 |

| Employee | 236 | 25.16 |

| Merchant | 148 | 15.78 |

| Student | 22 | 2.35 |

| Daily laborer | 49 | 5.22 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 78 | 8.32 |

| Married | 860 | 91.68 |

| Lack of food or hunger | ||

| Yes | 78 | 8.32 |

| No | 860 | 91.68 |

| Debit | ||

| Yes | 95 | 10.13 |

| No | 843 | 89.87 |

| Wealth index | ||

| Low | 314 | 33.47 |

| Middle | 313 | 33.37 |

| High | 311 | 33.16 |

Obstetric and clinical characteristics of the study participants

The majority of the participants, 858 (91.47%) had one or more ANC visits during their last pregnancy. The result of this study revealed that 109 (12%) of the study population experienced current pregnancy complications. Among the participants, 160 (19%) did not have enough time to visit the ANC service. Around one-fifth of women 182 (19.40%) spent less than thirty minutes to arrive at the health facility (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of obstetric and clinical factors among pregnant women at Debre Tabor and Woreta towns, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 938) | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Depression | ||

| Yes | 326 | 34.75 |

| No | 612 | 65.25 |

| Unplanned pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 354 | 37.74 |

| No | 584 | 62.26 |

| Number of live children(529) | ||

| One | 252 | 47.64 |

| Two-four | 263 | 49.72 |

| Five and above | 14 | 2.64 |

| Previous pregnancy complication | ||

| Yes | 116 | 20.60 |

| No | 447 | 79.40 |

| History of current pregnancy complication | ||

| Yes | 109 | 11.62 |

| No | 829 | 88.38 |

| Type of current pregnancy complication (n = 109) | ||

| Anemia | 35 | 32.11 |

| APH | 21 | 19.27 |

| Edema | 21 | 19.27 |

| Hypertension | 14 | 12.84 |

| UTI | 18 | 16.51 |

| History of abortion(n = 563) | ||

| Yes | 94 | 16.70 |

| No | 469 | 83.30 |

| Modes of previous abortion (n = 94) | ||

| Spontaneous | 84 | 89.36 |

| Assisted | 10 | 10.64 |

| Stillbirth | ||

| Yes | 5 | 0.53 |

| No | 933 | 99.47 |

| Gravidity | ||

| One | 375 | 39.98 |

| Two-four | 497 | 52.98 |

| Five and above | 66 | 7.04 |

| Previous history of depression | ||

| Yes | 258 | 27.51 |

| No | 680 | 72.49 |

| Family history of depression | ||

| Yes | 129 | 13.75 |

| No | 809 | 86.25 |

| Parity (548) | ||

| One | 253 | 46.17 |

| Two-four | 277 | 50.55 |

| Five and above | 18 | 3.28 |

| History of stillbirth (n = 563) | ||

| Yes | 36 | 6.39 |

| No | 527 | 93.61 |

| Fear of pregnancy complication | ||

| Yes | 491 | 52.35 |

| No | 447 | 47.65 |

| Chronic illness | ||

| Yes | 67 | 7.14 |

| No | 871 | 92.86 |

| Types of chronic illness (67) | ||

| Anemia | 12 | 17.91 |

| CHF | 19 | 28.36 |

| Hypertension | 22 | 32.84 |

| UTI | 14 | 20.89 |

| Lack of time for ANC visit | ||

| Yes | 160 | 18.65 |

| No | 698 | 81.35 |

| Waiting a long time for ANC service | ||

| Yes | 576 | 67.13 |

| No | 282 | 32.87 |

| Staff attitude influence ANC service | ||

| Yes | 752 | 80.17 |

| No | 186 | 19.83 |

| Privacy influence ANC service | ||

| Yes | 652 | 75.99 |

| No | 206 | 24.01 |

| Integration of ANC influence ANC service | ||

| Yes | 652 | 75.99 |

| No | 206 | 24.01 |

| Long travel time influences ANC visit | ||

| Yes | 756 | 80.60 |

| No | 182 | 19.40 |

| Initiation of ANC visit | ||

| Early initiation | 173 | 20.16 |

| Late initiation | 685 | 79.84 |

Psychosocial and behavioral characteristics of the study participants

Out of 938 study populations, around one-fifth experienced hazardous level use of alcohol, only 203(22%) had strong social support, and 366 (39%) had life-threatening events (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency distribution of psychosocial and behavioral factors among pregnant women at Debre Tabor and Woreta towns, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 938) | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Life-threatening events | ||

| Yes | 366 | 39.02 |

| No | 572 | 60.98 |

| Social support | ||

| Poor | 417 | 44.46 |

| Moderate | 318 | 33.90 |

| Strong | 203 | 21.64 |

| Inter partner violence(IVP) | ||

| Yes | 493 | 52.56 |

| No | 445 | 47.44 |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Yes | 206 | 21.96 |

| No | 732 | 78.04 |

Factors associated with inadequate ANC visits

Antenatal depression, previous pregnancy complication, marital status, life-threatening events, history of depression, intimate partner violence, family history of depression, unplanned pregnancy, Social support, alcohol use, hunger, debt, long travel time for ANC visit, and late initiation of ANC visit all had a bivariate relationship with inadequate visits with the P-value < 0.20. All these variables were a candidate for multivariable analysis.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses showed that, after adjustment for covariates, women with antenatal depression symptoms (AOR = 1.96 (95% CI 1.220, 3.162)) were twice more likely to be inadequate ANC visits than women without antenatal depression symptoms. In addition, women with a history of late initiation of ANC visits (AOR = 2.20 (95% CI 1.393, 3.471)) and long travel time for ANC visits (AOR = 1.83 (95% CI 1.166, 2.870)) were increased odds of inadequate ANC visits as compared with their counterpart (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bivariate and multivariable analysis for factors associated with inadequate ANC visits among women at Debre Tabor and Woreta towns, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

| Characteristics | Inadequate ANC visit | COR at 95%CI | AOR at 95%C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Depression | ||||

| Yes | 244 | 82 | 2.33 (1.734, 3.140) | 1.96 (1.220,3.162) * |

| No | 343 | 269 | 1 | 1 |

| A complication of previous pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 82 | 34 | 1.64 (1.055, 2.554) | 1.23 (0.752,2.021) |

| No | 266 | 181 | 1 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 62 | 16 | 2.47 (1.403, 4.357) | 2.48 (0.976,6.292) |

| Married | 525 | 335 | 1 | |

| Life-threatening events | ||||

| Yes | 258 | 108 | 1.76 (1.334, 2.332) | 0.93 (0.569,1.524) |

| No | 329 | 243 | 1 | |

| History of depression | ||||

| Yes | 188 | 70 | 1.89 (1.382, 2.589) | 1.44 (0.821,2.530) |

| No | 399 | 281 | 1 | |

| Intimate partner violence (IPV) | ||||

| Yes | 332 | 161 | 1.54 (1.178, 2.005) | 0.89 (0.578,1.370) |

| No | 255 | 190 | 1 | |

| Family history of depression | ||||

| Yes | 97 | 32 | 1.97 (1.292, 3.015) | 1.01(0.508,2.001) |

| No | 490 | 319 | 1 | |

| Unplanned pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 238 | 116 | 1.38 (1.048, 1.822) | 1.18 (0.784,1.786) |

| No | 349 | 235 | 1 | |

| Social support | ||||

| Poor | 278 | 139 | 1.17 (0.826, 1.663) | 0.81(0. 464,1.422) |

| Moderate | 181 | 137 | 0.77 (0.539, 1.111) | 0.81 (0.482,1.369) |

| Strong | 128 | 75 | 1 | |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| Yes | 147 | 59 | 1.65 (1.181, 2.315) | 1.63 (0.997,2.661) |

| No | 440 | 292 | 1 | |

| Hunger | ||||

| Yes | 55 | 23 | 1.47 (.889, 2.445) | 0.88 (0.318,2.411) |

| No | 532 | 328 | 1 | |

| Debit | ||||

| Yes | 70 | 25 | 1.77 (1.096, 2.845) | 1.30 (0.479,3.528) |

| No | 517 | 326 | 1 | |

| Long travel time for ANC visit | ||||

| Yes | 499 | 257 | 2.07 (1.495, 2.877) | 1.83 (1.166,2.870) * |

| No | 88 | 94 | 1 | |

| Time of initiation of ANC visit | ||||

| Late initiation | 430 | 255 | 2.10(1.500,2.946) | 2.20 (1.393,3.471) ** |

| Early initiation | 77 | 96 | 1 | |

NB Abbreviations, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio, COR crude odds ratio; AOR adjusted odds ratio, ANC antenatal care; ** (P ≤ 0.01); *(P < 0.05); Hosmer–lemeshow: 0.5411.

In a fully adjusted model; unplanned pregnancies (AOR = 1.18 (95% CI 0.784, 1.786)), the experience of threatening life events (AOR = 0.93 (95% CI 0.569, 1.524)), complication of previous pregnancy (AOR = 1.23 (95% CI 0.752, 2.021)), and intimate partner violence (AOR = 0.89 (95% CI 0.578, 1.370)), marital status (AOR = 2.48(95%CI 0.976, 6.292)), debit(AOR = 1.30 (95%CI 0.479, 3.528)), hunger (AOR = 0.88 (95%CI 0.318, 2.411)), family history of depression (AOR = 1.01 (95%CI 0.508, 2.001)), and history of depression (AOR = 1.44 (95% CI 0.821, 2.530)) during pregnancy were no longer associated with inadequate ANC visits, even if there were strongly associated in bivariate analyses. A Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicated that the model fit the data well (p = 0.5411).

Discussion

The main finding was antenatal depression has effect on ANC visits in the Ethiopian urban settings. This is the first to our knowledge population-based, prospective cohort study examining specifically the effect of antenatal depression on ANC visits in our country. After controlling for known risk factors for inadequate ANC visits, antenatal depression (AOR = 1.96 (95% CI 1.220, 3.162)) remained significantly associated with inadequate ANC visits. The incidence of inadequate ANC visits in the exposed group due to antenatal depression was 25.33%.

Similarly, the positive effect of antenatal depression on inadequate ANC visits was reported in the United States of America, England, and East Asia region22,23,25,26. The possible explanation might be depression symptoms have loss of interest, and fatigue that disturb normal mother-infant bonding43,44. However, the association that we have reported about the increased odds of inadequate ANC visits among women with antenatal depressive symptoms did not replicate the findings of the recent cohort study from Ghana and the US of America21,27. These conflicting results might arise due to differences in socio-cultural, demographic factors, and sample size.

Furthermore, results from multivariable logistic regression analyses indicated that long travel time to health facility found to be highly influential over the use of ANC visits. In this study, women who travel more than 30 min to health facilities were 1.83 times more likely to have inadequate ANC visits as compared to their counterparts. This finding is supported by several other studies including in Ethiopia45–54. It is a fact that the accessibility of a health facility is the main barrier to maternal health service. However, our finding is in contrast to the study finding in Zambia55. The possible explanation might be due to Geographic, socio-cultural, and level of awareness differences.

Study findings from Cameroon and South Africa revealed that timely initiation of ANC visits is a key method to decrease pregnant women’s morbidity and mortality3,56. Also, pregnant women who received an early ANC check-up were much more likely to receive four or more WHO-recommended ANC visits57. Despite this importance, the results of this study revealed that only 173 (20.16%) of pregnant women were found to early initiate ANC visits. This estimate reflects under-utilization of ANC, and this could contribute to high maternal mortality. Those pregnant women who were late initiated ANC visits were 2.2 times more likely to have inadequate ANC visits as compared to their counterparts. The result was consistent with the research finding from Belgium58.

Limitations

This study has limitations that prevent the full understanding of adequate antenatal care for ANC attendance in the study area; specifically, we did not address the content adequacy of antenatal care. Besides, we had no information on antidepressant medication for those referred to a psychiatric unit, thus it could not be assessed its roles as a confounder in multivariable analysis.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study have important implications. As this study confirmed that antenatal, depression has an adverse effect on ANC visits.

The health care providers and policymakers should think about the efforts to reduce the effect of antenatal depression such as routine screening of all pregnant women for depressive symptoms and treating them at the primary health care level by integrating the service; since screening is an effective approach for reducing morbidity in depressed people59, as a result, adequacy of ANC visits could be improved or maintained.

Conclusions

This study suggests that antenatal depression affects ANC visits in Ethiopian urban settings. The incidence of inadequate ANC visits in the exposed group that is due to antenatal depression was 25.33%. Therefore, early detecting and treating depression during the antenatal period reduced significantly the impacts of depression on the health of the mother and fetus. Discussing antenatal depression and its effects on ANC visits for the community as a whole is warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the University of Gondar for providing financial support. We are grateful to the women who participated in the study. Our special thanks go to data collectors and supervisors.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Ante natal care

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- OR

Odds ratio

- CMD

Common mental disorder

- EPDS

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale

- FAST

Fast alcohol screening test

- IPV

Intimate partner violence

- LTE

List of threatening experiences

- OSSS-3

Oslo-3 social support scale

Author contributions

All authors designed and developed the research protocol and tool. Also we were responsible for training and data collection. They analyzed the data, interpreted the findings, and wrote the manuscript. Finally, all authors read and approved the revised manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of Ph.D. degree fulfillment funded by the University of Gondar.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Goalkeepers Report. Data from IHME (2021). https://www.gatesfoundation.org/goalkeepers/report/2021-report/progress-indicators/maternal-mortality/.

- 2.Nikiéma B, Beninguisse G, Haggerty JL. Providing information on pregnancy complications during antenatal visits: Unmet educational needs in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(5):367–376. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pattinson R. Basic Antenatal Care Handbook. University of Pretoria; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downe S, Finlayson K, Tunçalp Ӧ, Metin Gülmezoglu A. What matters to women: A systematic scoping review to identify the processes and outcomes of antenatal care provision that are important to healthy pregnant women. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016;123(4):529–539. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cumber SN, Diale DC, Stanlly E, Monju N. Importance of antenatal care services to pregnant women at the Buea Regional Hospital Cameroon. J. Fam. Med. Health Care. 2016;2(4):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haftu A, Hagos H, Mehari M-A. Pregnant women adherence level to antenatal care visit and its effect on perinatal outcome among mothers in Tigray Public Health institutions, 2017: Cohort study. BMC. Res. Notes. 2018;11(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3987-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Organization WH. WHO antenatal care randomized trial: manual for the implementation of the new model. World Health Organization. Report No.: 9241546298 (2002).

- 8.AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T. Antenatal Care in Developing Countries: Promises, Achievements and Missed Opportunities-An Analysis of Trends, Levels and Differentials, 1990–2001. World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Who U. World Bank: Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990–2010. WHO, UNICEF. UNFPA and The World Bank Estimates; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basha GW. Factors affecting the utilization of a minimum of four antenatal care services in Ethiopia. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2019;2019:5036783. doi: 10.1155/2019/5036783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.EPHI. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey 2019. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR363/FR363.pdf.

- 12.Finlayson K, Downe S. Why do women not use antenatal services in low-and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Othman S, Almahbashi T, Alabed AAA. Factors affecting utilization of antenatal care services in Sana’a City, Yemen. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2017;17(3):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutamo Z, Assefa N, Egata G. Maternal health care use among married women in Hossaina, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015;15(1):365. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarekegn SM, Lieberman LS, Giedraitis V. Determinants of maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia: Analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesfin, M. & Farrow, J. Determinants of antenatal care utilization in Arsi Zone, Central Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev.10(3). Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhd/article/view/215585 (1996).

- 17.Mekonnen Y, Mekonnen A. Factors influencing the use of maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2003;21(4):374–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rurangirwa AA, Mogren I, Nyirazinyoye L, Ntaganira J, Krantz G. Determinants of poor utilization of antenatal care services among recently delivered women in Rwanda; A population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1328-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanlon C. Maternal depression in low-and middle-income countries. Int. Health. 2012;5(1):4–5. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihs003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jafri SAM, et al. Prevalence of depression among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Pakistan. Acta Psychopathol. 2017;3:54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weobong B, Ten Asbroek AH, Soremekun S, Manu AA, Owusu-Agyei S, Prince M, et al. Association of antenatal depression with adverse consequences for the mother and newborn in rural Ghana: Findings from the DON population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e116333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus, S. M. Depression during pregnancy: Rates, risks and consequences. J. Popul. Therapeutics Clin. Pharmacol.16(1). https://jptcp.com/index.php/jptcp/article/view/295 (2009). [PubMed]

- 23.Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ. 2001;323(7307):257–260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health, U. D. O, Services, H. Healthy people 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives; Full report with commentary. Healthy people 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives; Full report with commentary. p. 692 (1991).

- 25.Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in women: Implications for health care research. Science. 1995;269(5225):799–801. doi: 10.1126/science.7638596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niemi M, Falkenberg T, Petzold M, Chuc NTK, Patel V. Symptoms of antenatal common mental disorders, preterm birth and low birthweight: A prospective cohort study in a semi-rural district of V ietnam. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 2013;18(6):687–695. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim H, Mandell M, Crandall C, Kuskowski M, Dieperink B, Buchberger R. Antenatal psychiatric illness and adequacy of prenatal care in an ethnically diverse inner-city obstetric population. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2006;9(2):103–107. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, Cabral H. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: Relationship to poor health behaviors. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989;160(5):1107–1111. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bitew T, Hanlon C, Kebede E, Medhin G, Fekadu A. Antenatal depressive symptoms and maternal health care utilisation: A population-based study of pregnant women in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Debre Tabor District Health Office . District Health Office annual report on maternal and child health service performance. Debre Tabor: Amhara regional Health Bureau; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tesfaye M, Hanlon C, Wondimagegn D, Alem A. Detecting postnatal common mental disorders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale and Kessler scales. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;122(1–2):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psych. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agha S, Tappis H. The timing of antenatal care initiation and the content of care in Sindh, Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0979-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brugha TS, Cragg D. The list of threatening experiences: The reliability and validity of a brief life events questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1990;82(1):77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montón-Franco C, Josefa G, Gómez-Barragán M, Sánchez-Celaya M, Ángel Díaz-Barreiros M. Psychometric properties of the List of Threatening Experiences—LTE and its association with psycho social factors and mental disorders according to differents coring methods. Affect Disord. 2013;150:931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalgard OS, Dowrick C, Lehtinen V, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Casey P. Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression: A multinational community survey with data from the ODIN study. Soc Psych Psych Epidemiol. 2006;41:444–451. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boen H, Dalgard OS, Bjertness E. The importance of social support in the a ssociations between psychological distress and somatic health problems and socio-economic factors among older adults living at home: A crosssectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fekadu A, Medhin G, Selamu M, Hailemariam M, Alem A. Population level mental distress in rural Ethiopia. BMC Psych. 2014;14:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasch V, Van TN, Nguyen HTT, Manongi R, Mushi D, Meyrowitsch DW, et al. Intimate partner violence (IPV): The validity of an IPV screening instrument utilized among pregnant women in Tanzania and Vietnam. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0190856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hodgson R, Alwyn T, John B, Thom B, Smith A. The FAST alcohol screening test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(1):61–66. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fewtrell MS, Kennedy K, Singhal A, Martin RM, Ness A, Hadders-Algra M, et al. How much loss to follow-up is acceptable in long-term randomised trials and prospective studies? Arch. Dis. Child. 2008;93(6):458–461. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.127316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kristman V, Manno M, Côté P. Loss to follow-up in cohort studies: How much is too much? Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2004;19(8):751–760. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000036568.02655.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray L, Cooper PJ. Postpartum depression and child development. Psychol. Med. 1997;27(2):253–260. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cruz EBDS, Simões GL, Faisal-Cury A. Rastreamento da depressão pós-parto em mulheres atendidas pelo Programa de Saúde da Família. Revis. Bras. de Ginecol. e Obstet. 2005;27(4):181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Worku EB, Woldesenbet SA. Factors that influence teenage antenatal care utilization in John Taolo Gaetsewe (JTG) district of northern Cape Province, South Africa: Underscoring the need for tackling social determinants of health. Int. J. MCH AIDS. 2016;5(2):134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banda, C. Barriers to utilization of focused antenatal care among pregnant women in Ntchisi district in Malawi. Available from: https://trepo.tuni.fi/handle/10024/84640 (2013).

- 47.Jacobs C, Moshabela M, Maswenyeho S, Lambo N, Michelo C. Predictors of antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and postnatal care utilization among the remote and poorest rural communities of Zambia: A multilevel analysis. Front. Public Health. 2017;5:11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ali SA, Ali SA, Feroz A, Saleem S, Fatmai Z, Kadir MM. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care among married women of reproductive age in the rural Thatta, Pakistan: Findings from a community-based case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nsibu CN, et al. Determinants of antenatal care attendance among pregnant women living in endemic malaria settings: experience from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;2016:5423413. doi: 10.1155/2016/5423413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tewodros B, Dibaba Y. Factors affecting antenatal care utilization in Yem special woreda, Southwestern Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2009;19(1):45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aliy J, Mariam DH. Determinants of equity in utilization of maternal health services in Butajira, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2012;26(1):265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agho KE, Ezeh OK, Ogbo FA, Enoma AI, Raynes-Greenow C. Factors associated with inadequate receipt of components and use of antenatal care services in Nigeria: A population-based study. Int. Health. 2018;10(3):172–181. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihy011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Magadi MA, Madise NJ, Rodrigues RN. Frequency and timing of antenatal care in Kenya: Explaining the variations between women of different communities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000;51(4):551–561. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00495-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.King-Schultz L, Jones-Webb R. Multi-method approach to evaluate inequities in prenatal care access in Haiti. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(1):248–257. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2008.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kyei NN, Campbell OM, Gabrysch S. The influence of distance and level of service provision on antenatal care use in rural Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cumber SN, Diale DC, Stanly EM, Monju N. Importance of antenatal care services to pregnant women at the Buea Regional Hospital Cameroon. J. Fam. Med. Health Care. 2016;2(4):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agha S, Tappis H. The timing of antenatal care initiation and the content of care in Sindh, Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0979-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beeckman K, Louckx F, Putman K. Determinants of the number of antenatal visits in a metropolitan region. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calonge N, Petitti DB, DeWitt TG, Dietrich AJ, Gordis L, Gregory KD, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151(11):784–792. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.