Abstract

Providing quality healthcare services through health promotion activities to patients, hospital-based professionals and the wider community is the goal of the health promoting hospital (HPH). There is, however, no formal structured pathway for “universally” providing health promotion services in hospitals. Accordingly, this study was conducted with the aim of presenting a model designed to promote and increase health-related satisfaction of hospital-professionals in health-promoting hospitals (HPHs) in Iran—as a potential tool to guide international HPH standards. Lifestyle, quality of life, organizational culture, and job satisfaction were measured using standardized questionnaires in specialized hospitals in Hamadan, Iran. A structural equation model (SEM) using partial least squares (PLS) software (version 2) was used to determine the validity and fit of the conceptual framework/model. The study revealed that several factors were identified as strong predictors of job satisfaction and wellbeing, including various dimensions of lifestyle such as spiritual health, physical activity, stress management, and interpersonal communication, dimensions of quality of life including physical and mental aspects, and organizational culture. The values of predictive relevance (Q2) for physical and psychological dimension of life quality, organizational culture, and job satisfaction were estimated to be 0.101, 0.250, and 0.040 and 0.251, respectively. Conclusively, the study found a goodness of fit (GOF) value of 0.415, indicating that the model had a high predictive power and fit well. Based on these results, it is suggested that implementing HPH interventions that focus on the outcomes of this model could lead to increased job satisfaction and wellbeing in hospitals. Additionally, the model could serve as a useful indicator of HPHs.

Keywords: Health promoting hospitals, lifestyle, quality of life, organizational culture, job satisfaction

Introduction

The Health Promoting Hospital (HPH) is a concept developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to promote and support the creation of health-promoting environments within hospitals. According to the WHO, an HPH is “a hospital that constantly strives to integrate health promotion and health education into all aspects of its operation and culture.” 1

The HPH program was introduced in 1988 as one of the recommendations of the WHO to more widely promote community health. 2 The main impetus was to expand a broader health-oriented approach into the daily activities of hospitals that extended beyond the known limitations of “traditional” acute biomedical models of health. 3 The WHO has developed standards for HPHs including management policy, patient assessment, patient information and intervention, promoting a healthy workplace and continuity and cooperation. 4 In essence, these standards focus on improving the patient’s health, improving the employee’s health, transforming the whole organization’s health-promoting culture and extending that as an outreach to the wider community health. 5

The results of a study by Yaghoubi and Javadi 6 showed that the scores of management policy, patient assessment, patient information and intervention, promoting a healthy workplace and continuity and cooperation were, respectively, 53.8 ± 14.2, 44.2 ± 20.1, 70.8 ± 8.1, 55.5 ± 14.1, and 44.7 ± 11.1 in cities of Iran (Tehran, Esfahan, Shiraz, and Gilan).

Also, the findings of study conducted in Esfahan (Iran) showed that the scores of management policy, patient assessment, patient information and intervention, promoting a healthy workplace and continuity and cooperation were, respectively, 39.2 ± 11.4, 52.8 ± 16.2, 79.8 ± 13.5, 56.2 ± 12.5, and 36.2 ± 10.8. 7 Another study performed in Hamadan (Iran) indicated that the scores of mentioned standards were, respectively, 35.5 ± 8.7, 53.1 ± 13.2, 62.5 ± 2.3, 31.2 ± 13.2, and 65.8 ± 3.7. 8

By prioritizing the health of personnel in the workplace, hospitals can provide high-quality services to patients and increase patient satisfaction with the organization. 9 This issue has been addressed in various studies directly related to organizational culture. 10 Job satisfaction is typically determined by a combination of factors, including the level of fulfillment and reward that employees derive from their work, as well as their level of engagement and motivation. 11

The achievement of the WHO’s objective of promoting community health through patient participation is contingent on the creation of an organization that prioritizes the health of its personnel and provides high-quality services to patients. This aligns with the WHO’s definition of HPH, which emphasizes the importance of integrating health promotion and education into all aspects of a hospital’s operation and culture. 2

The WHO has not provided specific strategies or methods for achieving the goals of HPH, nor has it defined a standardized approach for providing health-promoting services in hospitals. As a result, individual hospitals around the world have had to develop their own strategies and methods to achieve the goals of HPH, and their success in doing so has depended on the effectiveness of their particular approach. Given the significance of promoting personnel health in the context of HPHs, this study aimed to provide a model that can enhance hospital personnel’s job satisfaction. Improving job satisfaction is an important indicator of promoting personnel health, and this model potentially contribute to the overall success of HPHs.

Conceptual Framework

According to the available texts and evidence, an individual’s level of job satisfaction within an organization is positively influenced by their quality of work-life. 12 The study by Hossein Abbasi and Agha Amiri 13 showed that there is a significant relationship between some dimensions of lifestyle and nurses’ job satisfaction.

The hospital, as a dynamic organization, observes good but, if the dominant organizational culture in the hospital does not attempt to promote its personnel’s health, it cannot realize its purpose of providing job satisfaction, high-quality services to patients and the community. 3 Organizational culture refers to the shared values, beliefs, attitudes, customs, and behaviors that characterize an organization. It is a complex concept that encompasses various aspects of organizational life, such as communication patterns, decision-making processes, leadership styles, and employee behavior. 14

Job satisfaction is considered the most important variable in the field of organizational culture and is a factor for enhancing employee efficiency. Under the umbrella of job satisfaction, job security plays a vital role in ensuring employee performance, accounting for up to 95% of its impact. 15

Multiple studies have shown that adopting a lifestyle that promotes good health leads to an improvement in an individual’s overall quality of life.16-18

Quality of work life not only affects the job satisfaction of employees, but also affects the life outside work, including family, leisure time, and social needs. 19 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality of life as an individual’s subjective evaluation of their place in society, taking into account the cultural and value-based norms of their environment, as well as their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. 20

Study findings show that the implementation of the quality of life programs has increased job satisfaction. 21 On the other hand, Meeting the needs of employees also helps to improve the long-term efficiency of the organization. 22 Gupta and Sharma 23 believe that the quality of life is important for organizational performance and is an effective factor in enhancing employee motivation at work. Consequently, we must first concentrate on the health-promoting lifestyle and person’s quality of life based on a healthy organizational culture to obtain job satisfaction among the personnel of the HPH.24,25

The target group for this standard is personnel, and examining related studies (mentioned studies) identified the main weakness of the standard as a thorough assessment of the 6 dimensions of lifestyle (health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, spiritual health, interpersonal relationships, and stress management) and 2 dimensions of quality of life (physical and mental dimensions), organizational culture, and job satisfaction to reach the desired conceptual framework.

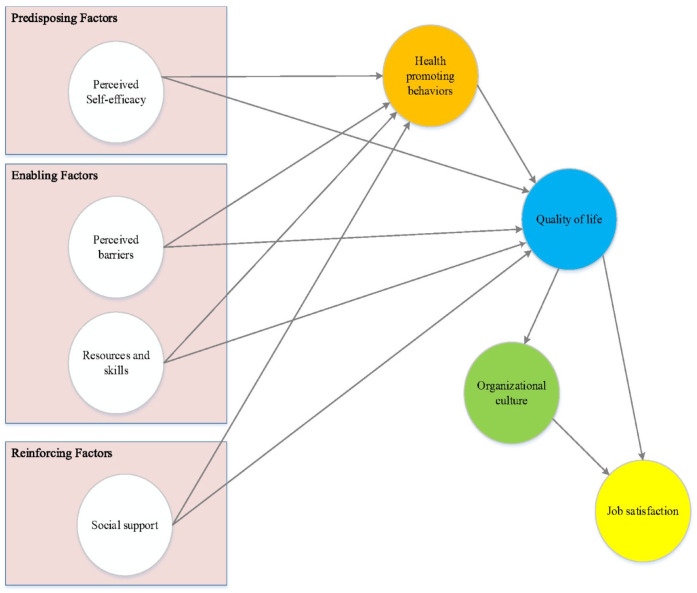

The PRECEDE-PROCEED model provides a comprehensive framework for identifying health needs and developing, implementing, and evaluating health promotion and other public health programs to address those needs. PRECEDE provides the structure for planning a targeted and focused public health program. PROCEED provides the structure for implementing and evaluating the public health program. PRECEDE stands for Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation. 26

This pattern provides a framework through which the effective factors in behavior, such as enabling factors (access to resources and skills), reinforcing factors (the influence of others, family, health personnel, and peers), and predisposing factors (awareness and attitudes), are identified for intervention in specific educational programs. 27 It is one of the models of planning in education and health promotion, and has been successfully applied in clinical trials. 27

To extract a hypothetical conceptual framework based on the mentioned studies, the following assumptions were presented for investigation.

Hypothesis 1: Do the personnel’s lifestyle dimensions and health-promoting behaviors affect their quality of life dimensions?

Hypothesis 2: Do lifestyle dimensions of personnel’s health-promoting behaviors affect their job satisfaction?

Hypothesis 3: Do the personnel’s lifestyle dimensions affect the organizational culture of the hospital?

Hypothesis 4: Do the personnel’s lifestyle dimensions affect their job satisfaction?

Hypothesis 5: Does the organizational culture of the hospital affect the personnel’s job satisfaction?

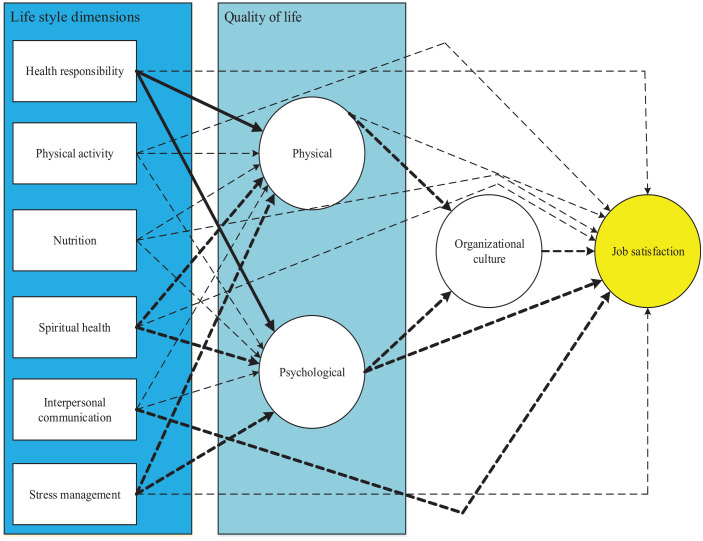

Based on the mentioned hypotheses, the conceptual model of Figure 1 was proposed in the next step, which investigated the relationship among life style, quality of life, organizational culture and job satisfaction. Effective structures were categorized into 3 categories of enabling, predisposing, and reinforcing factors based on the PRECEDE model (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Hypothetical conceptual framework of job satisfaction predictors in hospital personnel.

Figure 2.

A conceptual framework for predicting the quality of life and job satisfaction based on the structure of the PRECEDE model.

One of the most powerful and appropriate methods of analysis in behavioral science and social science research is multivariate analysis. Because the nature of such issues is multi-variable and they cannot be solved with a two-variable method. Analysis of covariance structures or causal modeling or structural equation model is one of the main methods of analyzing complex data. Since the current research involved multiple independent variables that may have impacted the dependent variable(s), it was necessary to use a structural equation model (SEM) in order to investigate these effects. 28

Methods

Target community

This descriptive-analytical (cross-sectional) study was conducted in the specialized hospitals of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan province, Iran. Hamadan has 2 specialized hospitals which have a similar situation in terms of improving health of the workplace. 3 Therefore, the present research was conducted to investigate the relationship between variables under study to predict effectiveness rate of variables using structural equation models. For performing structural equations for each visible variable, a sample size of 5 to 10 people is required. 29 Therefore, with regard to 94 visible variables in the model and 6 people as the sample size for each observable variable, the study sample size is determined as 564 according to equation (1).

| (1) |

In total, 600 qualified personnel were determined as the sample size. Inclusion criteria involved having at least 1 year of working experience and willingness to participate in the study (completing the written ethical consent to engage in the study). Proportionate stratified random sampling method was used for sampling. Each of the hospitals under study was considered as a stratum, and then the number of samples required was selected by simple random sampling according to the number of personnel working in each hospitals. Given the number of personnel in each hospital and using proportional stratified random sampling, 300 nurses were selected from the total volume of 345 staff members at Fatemieh Hospital, and 300 nurses were selected from the total volume of 419 personnel at Farshchian Hospital. The research community in this study was the nurses of all the treatment wards of the mentioned hospitals.

Data collection tools

Four standard questionnaires including health-promoting lifestyle profile (HPLP), 12-item short form health survey (SF-12) as a quality-of-life questionnaire, Robbins҆ organizational culture questionnaire, and Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire (MSQ) were used to collect the information.

A 52-question HPLP questionnaire developed by Walker et al 30 was applied. This questionnaire has 6 dimensions (self-health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, spiritual growth, interpersonal relationships, and stress management). The validity and reliability of the mentioned questionnaire was reviewed by Mohammadi Zeidi et al 31 in Iran. The results were as follows: Cronbach’s alpha for self-health responsibility (.86), physical activity (.79), nutrition (.81), spiritual growth (.84), interpersonal relationships (.75), and stress management (.91).

SF-12 was employed to assess quality of life. This questionnaire includes 12 questions related to 8 dimensions, classified into 2 subscales: physical (including 6 questions) and psychological/mental (including 6 questions). This questionnaire was localized for Iran by Montazeri et al. 32 The results showed that this questionnaire has the necessary validity and reliability. The value of Cronbach’s alpha for each item was reported to be greater than .7.

The modified Robbins҆ organizational culture questionnaire was also applied to assess organizational culture. According to the researchers, 10 questions constituted the main components of organizational culture questionnaire including creativity and innovation, risk-taking, attention to details, attention to achievement, attention to members of the organization, the influence of decision results on employees, and attention to the team to cover the considered objectives of this study. Reliability of the modified questionnaire was determined to be 0.82 using Cronbach’s alpha. The validity of Robbins organizational culture questionnaire has been confirmed in local studies. 33 The reliability of this questionnaire was also 0.89 in local studies using Cronbach’s alpha. 34

The MSQ is a popular tool used to assess job satisfaction, which was first developed at the University of Minnesota. 35 The questionnaire has 20 questions. The questions are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. This questionnaire has been adapted for Iran and the construct validity of the questionnaire has been examined and confirmed using confirmatory factor analysis (P < .05). Also, its reliability has been determined using Cronbach’s alpha equal to .8. 36

Method

At the beginning of the work, a session was held with the officials of each of the clinical, diagnostic, support, and educational the target departments and the educational and clinical supervisor. In these sessions, the goals of the study were fully explained. After identifying the study subjects, ethical consent was obtained from the participants. In order to reduce errors and ambiguities in answering the questionnaire, the questionnaire was completed in a face-to-face interview format at the participants’ workplace. The duration of each interview to complete the questionnaire was between 20 and 30 minutes.

After determining the subjects under study, the mentioned questionnaires were completed for participants by researcher. After completing the questionnaires, their information was extracted and analyzed by SPSS software and using of frequencies and compare means tests.

In order to test the assumed model, the obtained data has been entered into the smart PLS software and framework of the assumed model was drawn based on the entered data (Figure 1). To determine the validity of the structure and to determine the fit of the conceptual framework the structural equation modeling (SEM) was used. The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach is a method in which the relationships between interdependent and simultaneous multiple variables are examined and tested. In this study, 2 aspects of the SEM modeling approach were used: the measurement model and the structural model. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was applied in the measurement model to determine the contribution of each item (or manifest variable) in measuring the latent structure, and in other words, the measurement model examines the relationship between manifest and latent variables while the structural model investigates the relationships between latent variables. Based on structural equation model (SEM), the PLS software (version 2) was applied to determine structural validity and fit of the assumed model. The used tests were include Homogeneity, internal consistency reliability, Convergent validity, Divergent validity, Path Coefficients, Coefficient of determination index, Predictive Relevance, and Goodness of Fit (GOF).

Results

Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics of participants were presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Demographic index | Domain | Hospital 1 | Hospital 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||

| Age (years) | 20-29 | 142 | 47.3 | 126 | 42 |

| 30-39 | 90 | 30 | 126 | 42 | |

| >40 | 68 | 22.7 | 48 | 16 | |

| Gender | Male | 4 | 1.3 | 94 | 31.3 |

| Female | 296 | 98.7 | 206 | 68.7 | |

| Marital | Single | 115 | 38.3 | 126 | 42 |

| Married | 185 | 61.6 | 174 | 58 | |

| Education | Assistant | 22 | 7.3 | 17 | 5.7 |

| Bachelor | 234 | 78 | 236 | 78.7 | |

| Master of science | 44 | 14.7 | 47 | 15.6 | |

| Work experience (years) | <5 | 140 | 46.7 | 126 | 42 |

| 5-10 | 66 | 22 | 71 | 23.7 | |

| 10-15 | 31 | 10.3 | 54 | 18 | |

| 15-20 | 13 | 4.3 | 25 | 8.3 | |

| >20 | 50 | 16.7 | 24 | 8 | |

Table 2 show the proportion of staff was related to specific wards in each hospital.

Table 2.

The proportion of staff was related to specific wards in each hospital.

| Ward | Hospital 1 | Hospital 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| Surgery | 61 | 20 | 52 | 17 |

| Inpatient | 165 | 55 | 183 | 61 |

| Para clinic | 74 | 25 | 65 | 22 |

Table 3 shows the average of the parameters studied in the target population.

Table 3.

The mean of the parameters studied.

| Min-value | Max-value | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle | 55 | 190 | 129.75 | 20.72 |

| Quality of life | 12 | 47 | 32.48 | 6.18 |

| Organizational culture | 9 | 45 | 28.04 | 6.42 |

| Job satisfaction | 20 | 100 | 59.28 | 13.92 |

Measurement model

Homogeneity test

To test the measurement model, first a test of homogeneity was performed. Homogeneity indicates complete correlation between the questions of each structure. In this test, all factor loadings should be above 0.7. 29 Based on the results of this test, some questions from the questionnaires that had values less than 0.7 were removed. After removing the questions, the revised model was plotted. The results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The revised model.

Internal consistency reliability

In the next stage, the internal consistency reliability of the model was tested. Composite reliability and Communality are the main criteria that were used to measure the model’s reliability in this study. In this test, the following should be achieved 29 :

A) Cronbach’s alpha should be above .7.

B) Composite index should be above 0.79.

C) Communality index should be above 0.5.

Table 4 shows the results of internal consistency reliability of the model.

Table 4.

Reliability values of structures.

| Variables | Cronbach’s alpha | Composite reliability | Communality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health responsibility | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Physical activity | .816 | 0.876 | 0.640 |

| Nutrition | .758 | 0.852 | 0.660 |

| Spiritual health | .893 | 0.919 | 0.655 |

| Interpersonal communication | .722 | 0.843 | 0.643 |

| Stress management | .785 | 0.859 | 0.605 |

| Physical dimension of life quality | .718 | 0.809 | 0.587 |

| Psychological dimension of life quality | .829 | 0.921 | 0.853 |

| Organizational culture | .853 | 0.891 | 0.577 |

| Job satisfaction | .896 | 0.915 | 0.547 |

Convergent validity

The concept of convergent validity is that the questions of each construct should converge with each other. In PLS software, to measure convergent validity, the average extracted variance (AVE) and composite reliability are used. To have convergent validity 29 :

1- All factor loadings should be significant, the t-value of factor loadings should not between ±1.96.

2- The factor loading should be above 0.60 (close to 0.70).

3- The AVE for each variable should be above 0.50.

4- The composite reliability should be greater than the AVE.

The results show that the cross-loadings between variables explained that t-value of each variable’s questions was outside the range of ±1.96. The average variance extracted (AVE) value of each variable was greater than 0.5, and composite reliability of all the variables was greater than AVE value.

Divergent validity

The concept of divergent validity is that the measurement questions for a variable should be distinguishable or discernible from the measurement questions for other variables. Divergent validity is assessed through the use of cross loadings and the Fornell-Larcker criterion (113). In cross loadings, the loading of each question related to its own variable should be at least 0.1 greater than the loading of the same question on other (hidden) variables. In the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square root of the extracted variance of each variable must be greater than its maximum correlation with other variables. 29

Cross-loading for the items of each variable was greater than those for the remaining variables. The root of each variable’s average variance was greater than the correlation value of that variable with other variables. Therefore, validity divergence was ensured at the level of latent variables (responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, etc.).

Structural model

Path coefficients

These coefficients are compared at the confidence levels of 90%, 95%, and 99% with minimum t-statistics of 1.64, 1.96, and 2.58. 29

Table 5 shows the results of path analysis. As presented in Table 5, the relationships that were not significant received a negative sign indicating that the relevant hypothesis is rejected. In other words, these assumptions are predicted to be rejected in larger sample size.

Table 5.

Path coefficients analysis results.

| The desired path | Path coefficients | T-statistic | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health responsibility→physical dimension of life quality | 0.029040 | 0.747486 | − |

| Health responsibility→psychological dimension of life quality | 0.018201 | 0.462534 | − |

| Health responsibility→job satisfaction | 0.055153 | 1.577565 | − |

| Physical activity→physical dimension of life quality | 0.120123 | 3.158497 | + |

| Physical activity→psychological dimension of life quality | 0.137149 | 3.883767 | + |

| Physical activity→job satisfaction | −0.004526 | 0.124641 | − |

| Nutrition→physical dimension of life quality | −0.059895 | 1.459096 | − |

| Nutrition→psychological dimension of life quality | −0.047646 | 1.254830 | − |

| Nutrition→job satisfaction | −0.031147 | 0.989491 | − |

| Spiritual health→physical dimension of life quality | 0.281937 | 5.731029 | + |

| Spiritual health→psychological dimension of life quality | 0.410450 | 8.753336 | + |

| Spiritual health→job satisfaction | 0.043135 | 0.269134 | − |

| Interpersonal communication→physical dimension of life quality | 0.017045 | 0.341207 | − |

| Interpersonal communication→psychological dimension of life quality | 0.039938 | 0.865679 | − |

| Interpersonal communication→job satisfaction | 0.076795 | 2.049637 | + |

| Stress management→physical dimension of life quality | 0.141598 | 3.146063 | + |

| Stress management→psychological dimension of life quality | 0.111394 | 2.531630 | + |

| Stress management→job satisfaction | 0.043135 | 0.957697 | − |

| Physical dimension of life quality→organizational culture | 0.164161 | 3.498703 | + |

| Physical dimension of life quality→job satisfaction | 0.051640 | 1.522273 | − |

| Psychological dimension of life quality→organizational culture | 0.140935 | 3.017328 | + |

| Psychological dimension of life quality→job satisfaction | 0.102509 | 2.510521 | + |

| Organizational culture→job satisfaction | 0.580514 | 17.849299 | + |

Coefficient of determination index

This test shows how much independent variables can predict the dependent variable. The coefficient of determination is calculated based on the number of intragroup variables. Hair estimated the coefficient of determination as weak at 0.19, moderate at 0.33, and strong at 0.67. 29

Table 6 shows the results obtained regarding measuring coefficient of determination index. As shown in Table 6, the coefficients for determining physical dimension of quality of life and organizational culture were weak. The coefficient for determining psychological dimension of quality of life was moderate. Also, the coefficient for determining job satisfaction was higher than average.

Table 6.

Coefficient of determination.

| Variables | The coefficient of determination |

|---|---|

| Physical dimension of life quality | 0.182 |

| Psychological dimension of life quality | 0.297 |

| Organizational culture | 0.071 |

| Job satisfaction | 0.466 |

Predictive relevance

This test indicates the quality of the structural model. Values above zero indicate the high ability of the structural model in predicting (114). In other words, whether the quality of predicting dependent variables by the independent variable is appropriate or not. For this purpose, the increment index is used. If the increment index is 0.02, the quality of the model prediction is weak, if it is 0.15, the quality of the model prediction is moderate, and if it is 0.35, the quality of the model prediction is strong. 29

The model’s predictive power was determined by calculating Q 2 . In which, physical dimension of quality of life, psychological dimension of quality of life, organizational culture, and job satisfaction were estimated to be 0.101, 0.250, 0.040, and 0.251, respectively.

Goodness of fit (GOF)

This index considers both structural and measurement models together and tests their quality simultaneously. The results of this calculation are interpreted in such a way that values of 0.01, 0.25, and 0.36 are considered weak, moderate, and strong, respectively. 29 the GOF value was estimated to be 0.415, indicating that the model has a good fit.

Figure 4 shows the framework of the confirmed model using SEM, where solid arrows confirm the study hypotheses.

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework of the validated model using the structural equation model.

As can be seen from Figure 4, the variables of spiritual health, physical activity and stress management had an effect on the quality of life, as well as the dimensions of the quality of life had an effect on the organizational culture. And finally, the mentioned items had an effect on the job satisfaction.

Discussion

The results of measurement model suggested that the studied structures had high validity. The questionnaires used in the present study were standard questionnaires and their validity and reliability had been confirmed in the previous studies. Hence, the results obtained in measurement model confirmed validity and reliability of the used questionnaires.

The results of structural model revealed that dimensions of lifestyle (spiritual growth, physical activity, stress management, nutrition, self-health responsibility, and interpersonal relationships), dimensions of quality of life (physical and psychological), and organizational culture were predictors of job satisfaction.

Comprehensive planning is required for achieving the standards of HPHs. Because the standards cover various levels of the hospital and individuals, the personnel’s satisfaction in the hospital is one of significant dimensions for the organization’s sustainability and quality of work. 3 Accordingly, investigating the factors influencing job satisfaction based on a particular framework can help the managers and officials to faster achieve the standards of HPHs. This distinct framework was presented in the form of a proposed model in this study. As shown in Figure 4, a healthy lifestyle significantly influences the individual’s physical and psychological health. Society and subsequently, improves quality of life and job satisfaction. 37 Lifestyle is referred to a person’s attitudes, way of life, values, or worldview and involves factors,such as personality traits, nutrition, exercise, sleep, coping with stress, social support, and taking medication and covers dimensions of self-health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, spiritual growth, interpersonal relationships, and stress management. 38 Accordingly, it was regarded as one of the factors in the model. According to the results, interpersonal relationships are the only variable among the lifestyle dimensions that can directly increase personnel’s job satisfaction. Interpersonal relationships have a particular importance in lifestyle. In the case of lack of interpersonal relationships, the individual suffers from isolation and depression in the workplace, and his or her job satisfaction is influenced by this subject. Job satisfaction is referred to emotional orientation that an individual has concerning his/her job. Employees with higher job satisfaction are in good condition in terms of physical and mental strength.39,40 An individual cannot expect to develop an emotional orientation toward his/her job and, consequently, job satisfaction without having good interpersonal relationships. In fact, it is reasonable that the other dimensions of lifestyle influence a person’s job satisfaction by influencing quality of life. Physical activity, spiritual growth, and stress management are 3 dimensions of lifestyle that influenced the dimensions of life quality in the mentioned model. Physical activity, as one of significant components of a healthy lifestyle, plays a significant role in promoting health and preventing chronic diseases, and on the other hand, as hospitals҆ personnel have low physical activity due to their working conditions, this highlights the need for providing proper conditions for physical activity that influences their quality of life and increases their job satisfaction. 41 The relationship between stress management and job satisfaction can also be considered because many studies have explained that job stress is one of the main problems among nurses influencing their professional performance and personal life significantly and bringing about conflict between work and life. This subject should be considered because the effects of stress can be transferred from one environment to another or from one field to another one. The effects of job stress may disrupt the individual’s relationships, particularly the relationships among spouses, and their suffering and sadness are transferred to children and damage the quality of life.42,43 Studies have indicated that stress is prevalent among nurses higher than the general population. However, it may be very different between different countries as well as different nursing specialties.42,44 Some researchers have investigated more aspects of stress-related jobs to reduce stress levels in high-stress jobs, such as nursing. In contrast, others have mostly studied the individual’s situation, considering comparatively high prevalence of anxiety and the lack of initial prevention. Early diagnosis and appropriate control of this disorder lead to identification of its origin and inhibition of its continuity. It is important to employ preventive methods including educational methods, in recognizing and coping with anxiety in the early stages. 45 Training programs on stress management increase the individual’s capacity to decrease stress and adapt properly to stressful situations. 46 Significance of this issue can be shown by confirming the hypothesis regarding the effect of stress on quality of life and subsequently, job satisfaction.

Spiritual growth dimension of the lifestyle dimensions indicates the level to which the people believe in a stronger force than themselves that they can always rely on in their personal and work life and demand for help. Spiritual growth dimension can help the patience in encountering with personal and work problems. This lifestyle dimension can influence an individual’s mental health, interpersonal relationships, and quality of life and consequently, job satisfaction.47,48 Given importance of this dimension in increasing mental health, the increase in personnel’s quality of life and job satisfaction score to a more desirable level has been confirmed through educational and managerial interventions. The results of different studies have indicated that quality of life and job satisfaction have a two-way relationship with each other, and reduction in each of them results in a decrease in the others҆ value.49,50 On the other hand, the personnel’s quality of life is a prominent and influential factor in organizational culture. In fact, the personnel’s proper quality of life influences all their life activities particularly job satisfaction.

The researchers have paid attention to the nature and influence of organizational culture in the world concerning the modern organization and work over the past 30 years. 51 Organizational culture is defined as a collection of common beliefs and values influencing behavior and thinking of members of the organization and can be considered a starting point for movement and dynamism or an obstruction to progress. Organizational culture is one of the most fundamental fields of change and transformation in the organization. As new transformation programs further consider the organization’s fundamental change; hence, it can be said that these programs attempt to change and transform culture of the organization as framework of transformation platform. 52 Accordingly, hospitals’ organizational culture must be changed to convert the hospital into HPH. Various fields have been defined for organizational culture. Cameron and Quinn 53 identified that organizational culture has components, such as management model, strategic programs, organizational atmosphere, reward system, leadership, and the organization’s center values, which must be investigated and changed for organizational change. Robbins and Coulter 54 recognized 9 fields of creativity and innovation, risk-taking, attention to details, attention to achievement, attention to members of the organization, the influence of decision results on employees, attention to team, ambition, and adventuring for organizational culture. Creativity and innovation are referred to the level of an individual’s responsibility, freedom of action, and independence. Since, the personnel’s jobs in the hospital environment are such that they deal with the individual’s lives and health consequently, their freedom of action and independence are normally low, and most personnel are careful. Risk-taking can be described as the degree to which the people are inspired to take the initiative, take risky actions, and be ambitious. This field of organizational culture is normally of low level due to the essence of the personnel’s job working in the hospital, and they cannot take the initiative and risky actions considering the patient’s health and life.55,56 It should be stated that regarding the areas of attention to details, attention to achievement, attention to members of the organization and the influence of decision results on personnel, management policy is more based on treatment in the country’s hospitals and treating the patients and equipping various hospital wards. In these hospitals, paying the most attention to the patients and their treatment is the most remarkable achievement in treating the patients. Normally, the influence of decisions made on treatment is highly considered. Accordingly, the hospitals҆ management policy should be changed, and improving its personnel’s health should be considered more to change the organizational culture. Domination of the traditional system is one of the disadvantages in managing the country’s hospitals, according to which significant decisions and policies are made at the highest levels of management, and most personnel only implement the made decisions. 57 Consequently, there is weak teamwork in hospitals and minimum participation in making the decisions. In these situations, people consider work as an imposed task, leading to job dissatisfaction. 58 Hospital development programs are more designed to increase medical services, and to expand beds and wards. Sometimes, increasing health services is not increasing human resources, which increases the personnel’s workload and reduces job satisfaction. The organizational culture should be such that hospital programs promote the personnel and patient’s health to changing toward HPH. 56 Job satisfaction is one of the most significant issues in an organization’s human resource management, which is raised as a multidimensional concept. There are various definitions for job satisfaction but it is commonly described as people’s feelings about their job and its different dimensions.39,40 The lack of balance between the expectations that a person has of his/her job and those of the job is one of the principal factors that can influence job satisfaction.59-61 Job satisfaction is an essential factor that can influence the personnel’s health in the hospital. Factors influencing job satisfaction can be classified into 4 categories: organizational factors, environmental factors, the nature of work, and individual factors. 62 The lack of enthusiasm in work-life can be caused by job dissatisfaction, and its negative influences on people’s lives every day can cause a person not to be satisfied with his/her work-life. They may negatively influence the environment and relationships with family and friends. The individual’s mental and physical health is also influenced by job dissatisfaction. 63 Job satisfaction involves perceptions of work, communication with co-workers and managers, job control and security, rewards, professional situations, advancement, physical work environment, clients and feelings, such as a sense of independence, and self-improvement. 64 Hospital is among the work environments with several physical and psychological/mental risks, such as disease transmission, stress of the patients and patients҆ companions, and high workload, and hospital patients often are not in good physical and mental conditions that can influence the personnel’s job satisfaction. Hospitals҆ personnel normally are not independent in terms of their job. They do not experience more improvement in their job and perform a range of conventional tasks on a regular foundation due to the nature of their job, which can decrease their job satisfaction. Accordingly, there is a need to think about alternative incentives, such as reward systems and positive feedback to increase job satisfaction in these environments. These alternative systems are actualized by generating an organizational culture. The results of the previous studies conducted in Iran have determined that job satisfaction of hospital’s personnel is at a moderate level, and job satisfaction is influenced by factors, such as allocation of welfare facilities, satisfaction with the work environment, and improving salaries and benefits. 65 The results of this study revealed a strong relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction. Organizations normally cause the employees to be dissatisfied with a job utilizing the 3 principal mechanisms of formal organizational structure, command-based leadership, and control. Tall organizational structures constantly cause power to be concentrated in control of a comparatively small number of the people and putting the personnel in the chain’s last loops, leading to disinterest in the organization and job dissatisfaction. 66 Organizational culture is recognized as an essential and fundamental component in the body of an organization. It is like a social reality created based on the unique interactions of members of the organization. 67 Organizational culture introduces the organization’s knowledge, and a beneficial organizational culture influences the employee’s performance positively. Developing an organizational culture facilitates a sense of identity and commitment and promotes the organization. 68 In a strong and cohesive organizational culture, the individuals feel more sense of responsibility and commitment to work. Consequently, while considering the organization’s goals and strategies in terms of values and norms, they are satisfied with their job. 69 A constructive organizational culture increases the employees҆ satisfaction and positively creates a positive work environment by increasing interactions between the colleagues. In this environment, tasks are organized in such a way that they assist the employees in obtaining a high level of job satisfaction and organizational purposes. 70 Organizational culture has been found to influence formulation of purposes and strategies, job satisfaction, job motivation, organizational performance, creativity and innovation, employees҆ participation level, decision-making, hard-working, and organizational effectiveness. 71 It has been shown that the way of communication with the colleagues and managers is one of significant factors influencing job satisfaction of the hospitals҆ personnel.72-74 As declared in the proposed model, the personnel’s job satisfaction can be achieved in the hospital by increasing attention to the variables of lifestyle, quality of life, and organizational culture.

Conclusions

In this study, dimensions of lifestyle (spiritual growth, physical activity, stress management, self-health responsibility, nutrition, and interpersonal relationships), dimensions of quality of life (physical and psychological), and organizational culture were identified as predictors of job satisfaction. The results of the study showed that the variables of spiritual health, physical activity, and stress management had an effect on the quality of life, as well as the dimensions of the quality of life had an effect on the organizational culture. And finally, the mentioned items had an effect on the job satisfaction. Therefore, it seems that designing an intervention with emphasis on changing these variables can lead to the increased job satisfaction in the hospitals҆ personnel as an indicator of HPH.

Practical implication

Based on the results of this study, the following recommendations can be made to increase job satisfaction among nurses:

1- Design and implementation of educational interventions about improvement of lifestyle for hospitals staffs and managers.

2- Design and implementation of educational interventions about improvement of quality of life for hospitals staffs and managers.

3- Design and implementation of educational interventions about improvement of Organizational culture for hospitals managers.

Statute limitations

One of the limitations of this study is not considering confounding factors such as income, job security, etc.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank of all nurses who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences [grant number 9509235545].

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: All authors confirm their responsibility in the done study. All authors contributed to approving the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent: Ethical Code, IR.UMSHA.REC.1395.388, was received from the Research Morals Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for this study and informed consent form was provided for participants.

References

- 1. Pelikan JM, Metzler B, Nowak P. Health-promoting hospitals. In: Kokko S, Baybutt M, eds. Handbook of Settings-Based Health Promotion. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022;119-149. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hamidi Y, Moghadam SMK, Hazavehei SMM, et al. Effect of TQM educational interventions on the management policy standard of health promoting hospitals. Health Promot Int. 2021;36:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamidi Y, Hazavehei SMM, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, et al. Health promoting hospitals in Iran: a review of the current status, challenges, and future prospects. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2019;33:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Delobelle P, Onya H, Langa C, Mashamba J, Depoorter AM. Advances in health promotion in Africa: promoting health through hospitals. Glob Health Promot. 2010;17:33-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Groene O; World Health Organization. Mise En Oeuvre de La Promotion de La Santé Dans Les Hôpitaux: Manuel d’Autoévaluation Et Formulaires. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yaghoubi M, Javadi M. Health promoting hospitals in Iran: how it is. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Afshari A, Mostafavi F, Keshvari M, et al. Health promoting hospitals: a study on educational hospitals of Isfahan, Iran. Health Promot Perspect. 2016;6:23-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hamidi Y, Hazavehei SMM, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, et al. Investigation of health promotion status in specialized hospitals associated with Hamadan University of Medical Sciences: health-promoting hospitals. Hosp Pract. 2017;45:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ramli AH. Patient service and satisfaction systems. Bus Entrep Rev. 2019;15:189-200. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mesfin D, Woldie M, Adamu A, Bekele F. Perceived organizational culture and its relationship with job satisfaction in primary hospitals of Jimma zone and Jimma town administration, correlational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robbins S, Judge TA, Millett B, Boyle M. Organisational Behaviour. Pearson Higher Education AU; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maf’ula D, Nursalam N, Sukartini T. Determinants of quality of nursing work life: a systematic review. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil. 2020;24:7696-7708. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hossein Abbasi N, Agha Amiri M. Survey of relationship between health promoting lifestyle and job satisfaction in male nurses in Ahwaz City: a descriptive study. Iran J Neonatol. 2022;34:74-87. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meng J, Berger BK. The impact of organizational culture and leadership performance on PR professionals’ job satisfaction: testing the joint mediating effects of engagement and trust. Public Relat Rev. 2019;45:64-75. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mainardes EW, Rodrigues LS, Teixeira A. Effects of internal marketing on job satisfaction in the banking sector. Int J Bank Mark. 2019;37:1313-1333. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Karimlou V, Charandabi SM, Malakouti J, Mirghafourvand M. Effect of counselling on health-promoting lifestyle and the quality of life in Iranian middle-aged women: a randomised controlled clinical trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burdbar FT, Esmaeili M, Shafiee FS. Investigating the relationship between health literacy and health-promoting lifestyle in Youth. Arch Pharm Pract. 2020;1:86. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shaahmadi F, Shojaeizadeh D, Sadeghi R, Arefi Z. Factors influencing health promoting behaviours in women of reproductive age in Iran: based on pender’s health promotion model. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:2360-2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emadzadeh MK, Khorasani M, Nematizadeh F. Assessing the quality of work life of primary school teachers in Isfahan city interdisciplinary. J Contemp Res Bus. 2012;3:438-448. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee KH, Xu H, Wu B. Gender differences in quality of life among community-dwelling older adults in low- and middle-income countries: results from the study on global AGEing and adult health (Sage). BMC Public Health. 2020;20:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gordon JR. A Diagnostic Approach to Organizational Behavior. Allyn & Bacon; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shareef R. QWL program facilitate change. Pers J. 1990;69:58-61. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta M, Sharma P. Factor credentials boosting quality of work life of BSNL employees in Jammu region. Sri Krishna Int Res Educ Consort. 2011;2:79-89. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hazavehei SMM, Hamidi Y, Kharghani Moghadam SM, Karimi-Shahanjarini A. Exploring the views of medical staff in transforming a hospital into a health promoting hospital in Iran: a qualitative research. Hosp Pract. 2019;47:241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Melnyk BM, Kelly SA, Stephens J, et al. Interventions to improve mental health, well-being, physical health, and lifestyle behaviors in physicians and nurses: a systematic review. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34:929-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heshmati H, Behnampour N, Homaei E, Khajavi S. Predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption among female high school students based on PRECEDE model. Ranian J Health Educ Health Promot. 2014;1:5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hosseini Z, Moeini B, Hazavehei S, Aghamollai T, Moghimbeigi A. Effect of educational stress management, based on precede model, on job stress of nurses. Bimon J Hormozgan Univ Med Sci. 2011;15:200-208. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Choi Y, Chung; J-H. Multilevel and multivariate structural equation models for activity participation and travel behavior. J Korean Soc Transp. 2003;21:145-152. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract. 2011;19:139-152. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. The health-promoting lifestyle profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs Res. 1987;36:76-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohammadi Zeidi I, Pakpour Hajiagha A, Mohammadi Zeidi B. Reliability and validity of Persian version of the health-promoting lifestyle profile. J Maz Univ Med Sci. 2012;21:102-113. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Mousavi SJ, Omidvari S. The Iranian version of 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12): factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dargahi H, Eskandari M, Shaham G. The comparison between present with desired organizational culture in Tehran University of Medical Sciences’ Hospitals. J Payavard Salamat. 2010;4:72-87. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamidi Y, Mohammadi A, Soltanian AR, Mohammad Fam I. Organizational culture and its relation with quality of work life in university staff. J Ergon. 2016;3:30-38. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martins H, Proença T. Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire–Psychometric properties and validation in a population of Portuguese hospital workers. J. Econ. Manag. 2012; 471:1-23. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rad AM, Yarmohammadian MH. A study of relationship between managers’ leadership style and employees’ job satisfaction. Leadersh Health Serv. 2006;19:xi-xxviii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tran D, Hanh T. Stressful Life Events, Modifiable Lifestyle Factors, Depressive Symptoms, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Chronic Disease Among Older Women in Vietnam and Australia: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Queensland University of Technology; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cockerham WC. Health lifestyle theory and the convergence of agency and structure. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46:51-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Price JL. Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. Int J Manpow. 2001;22:600-624. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moghimi SM. Organization and Management Research Approach. Terme Publisher; 2001:315-320. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mohammadi M, Mehri A. Application of the transtheoretical model to predict exercise activities in the students of Islamic Azad University of Sabzevar. Alborz Univ Med J. 2012;1:85-92. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hazavehei SMM, Moghadam K, Melika S, Bagheri Kholenjani F, Ebrahimi H. The influence of educational interventions to reduce occupational stress: a systematic review. Health Saf Work. 2017;7:363-374. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grzywacz JG, Frone MR, Brewer CS, Kovner CT. Quantifying work-family conflict among registered nurses. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:414-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Issakidis C, Andrews G. Service utilisation for anxiety in an Australian community sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:153-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2009;373:2041-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kawano Y. Association of job-related stress factors with psychological and somatic symptoms among Japanese hospital nurses: effect of departmental environment in acute care hospitals. J Occup Health. 2008;50:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dehbashi F, Sabzevari S, Tirgari B. The relationship between spiritual well-being and hope in hemodialysis patients referring to the Khatam Anbiya hospital in Zahedan 2013-2014. Med Ethics J. 2015;9:77-97. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ghasemi-Pirbaloti M, Ahmadi R, Alavi-Eshkafteki SM, Alavi-Eshkaftaki SS. The association of spiritual intelligence and job satisfaction with mental health among personnel in Shahrekord University of Medical sciences. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2014;16:123-131. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cimete G, Gencalp NS, Keskin G. Quality of life and job satisfaction of nurses. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18:151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Michalos AC. Job Satisfaction, Marital Satisfaction and the Quality of Life: A Review and a Preview, Essays on the Quality of Life. Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arasteh H, Salimi M. Developing a model for leadership effectiveness in nursing colleges at Islamic Azad University. Q J Nurs Manag. 2013;2:19-29. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Heller R. Managing Change. Dorling Kindersley Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cameron KS, Quinn RE. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Robbins S, Coulter M. Management. Eight Edition. Person Education. England. Terjemahan PT Indeks. 2007. Management. PT Macanan Jaya Cemerlang. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Davidsson P. The Domain of Entrepreneurship Research: Some Suggestions, Cognitive Approaches to Entrepreneurship Research. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nafri N. The study of role organizational structure on staff empowerment in Economic & Financial Ministry. J Dev Manag. 2010;3:17-29. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Aghababaei R, Rahimi H. The study of structural aspects of knowledge-based organizations in Kashan University of Medical Sciences. Res Med Educ. 2016;8:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Akhtary Shojaei E, Nazari A, Vahidi R. Leadership styles of managers and job satisfaction among nurses in Tabriz hospitals. Hakim Res J. 2005;7:20-24. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hamidi Y, Barati M. Communication skills of heads of departments: verbal, listening, and feedback skills. Res J Health Sci. 2011;11:91-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Trivellas P, Reklitis P, Platis C. The effect of job related stress on employees’ satisfaction: a survey in health care. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013;73:718-726. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rogelberg SG. Encyclopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim K, Jogaratnam G. Effects of individual and organizational factors on job satisfaction and intent to stay in the hotel and restaurant industry. J Hum Resour Hospit Tour. 2010;9:318-339. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Altuntaş S. Factors affecting the job satisfaction levels and quit intentions of academic nurses. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34:513-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Adwan JZ. Pediatric nurses’ grief experience, burnout and job satisfaction. J Pediatr Nurs. 2014;29:329-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Abbaschian R, Avazeh A, Rabi SiahkaliS S. Job satisfaction and its related factors among nurses in the Public Hospitals of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, 2010. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J. 2011;1:17-24. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Salari S, Pelivarzadeh M, Rafati F, Ghaderi M. The relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction among hospital staff of Imam Khomeini (RA) in Jiroft per year 2013. Q J Nurs Manag. 2013;2:43-51. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Alvesson M. Understanding Organizational Culture. Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cheung SO, Wong PSP, Wu AWY. Towards an organizational culture framework in construction. Int J Proj Manag. 2011;29:33-44. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Belias D, Koustelios A. Organizational culture and job satisfaction: a review. Int Rev Manag Mark. 2014;4:132. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Meterko M, Mohr DC, Young GJ. Teamwork culture and patient satisfaction in hospitals. Med Care. 2004;42:492-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Saremi H, Nejad BM. Impact of organizational culture on employees empowerment. Human Resour Manag. 2013;65:19821-19829. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wyatt J, Harrison M. Certified pediatric nurses’ perceptions of job satisfaction. Pediatr Nurs. 2010;36:205-208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Jelastopulu E, Tsouvaltzidou T, Vangeli E, Messolora F, Detorakis J, C Alexopoulos E. Self-reported sources of stress, job satisfaction and quality of care in professional hospital nurses in west-Greece. Nurs Health. 2013;1:1-9. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mahmoudi H, Boulhasani M, Sepahvand MJ. The relationship between use of communication skills and job satisfaction of nurses. Daneshvar. 2012;20:77-82. [Google Scholar]