Abstract

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake among cisgender women in the United States is low. Just4Us, a theory-based counseling and navigation intervention, was evaluated in a pilot randomized controlled trial among PrEP-eligible women (n = 83). The comparison arm was a brief information session. Women completed surveys at baseline, post-intervention, and at three months. In this sample, 79% were Black, and 26% were Latina. This report presents results on preliminary efficacy. At 3 months follow-up, 45% made an appointment to see a provider about PrEP; only 13% received a PrEP prescription. There were no differences in PrEP initiation by study arm (9% Info vs. 11% Just4Us). PrEP knowledge was significantly higher in the Just4Us group at post-intervention. Analysis revealed high PrEP interest with many personal and structural barriers along the PrEP continuum. Just4Us is a promising PrEP uptake intervention for cisgender women. Further research is needed to tailor intervention strategies to multilevel barriers.

Keywords: Women, HIV, Pre-exposure prophylaxis, Intervention, Randomized Clinical Trial

Resumen

La aceptación de la profilaxis previa a la exposición (PrEP) al VIH entre las mujeres cisgénero en los Estados Unidos es baja. Just4Us, una intervención de asesoramiento y navegación basada en la teoría, se evaluó en un ensayo piloto controlado aleatorizado con mujeres aptas para la PrEP (n = 83). El brazo de comparación fue una breve sesión de información. Las mujeres completaron encuestas al inicio, después de la intervención ya los 3 meses. En la muestra, el 79% eran negros y el 26% eran latinas. Este informe presenta resultados sobre la eficacia preliminar. A los 3 meses de seguimiento, el 45% hizo una cita para ver a un proveedor acerca de la PrEP; solo el 13% recibió una receta de PrEP. No hubo diferencias en el inicio de la PrEP por brazo de estudio (9% Info frente a 11% Just4Us). El conocimiento fue significativamente mayor en el grupo Just4Us después de la intervención. El análisis reveló un alto interés por la PrEP con muchas barreras personales y estructurales a lo largo del continuo de la PrEP. Just4Us es una prometedora intervención de adopción de PrEP para mujeres cisgénero. Se necesita más investigación para adaptar las estrategias de intervención a las barreras multinivel.

Introduction

Cisgender women in the United States (U.S.) acquire human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), most commonly from heterosexual intercourse but also from intravenous drug use. Women made up almost 1 in 5 new HIV infections in 2018 [1]. That same year, black women were nearly four times more likely to acquire HIV than white women, primarily related to poverty, stigma, and discrimination [2]. Currently, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), in the form of a daily oral pill, can prevent HIV with an efficacy of up to 84% among cisgender women [3]. However, only 7% of women who could benefit were prescribed PrEP in 2018 [1]. Furthermore, the distribution of PrEP prescriptions has been disproportionate relative to HIV prevalence and, thus, potential need among cisgender women, with 48% of prescriptions among White women, 26% among Black women, and 18% among Latinx women [4]. Continued underutilization of this life-saving intervention among PrEP-eligible women will likely exacerbate inequities in HIV with heightened morbidity and mortality among poor and minority women in the US.

Our prior research and others have identified key individual, interpersonal, and structural barriers to PrEP uptake among cisgender women at various points on a PrEP continuum (described below). Although PrEP has been approved since 2012, many women are not even aware that this HIV prevention option is available to them [5, 6]. There have been public awareness campaigns supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), local and state health departments, and advocacy organizations that distribute PrEP information using, e.g., billboards, posters, social media, and websites. Yet, few public PrEP campaigns, advertising, or infomercials feature cisgender women, contributing to this widespread lack of awareness [7]. Available information about PrEP for women within their social networks is often scarce, leading to limited knowledge and misinformation [8]. When women learn about PrEP, interest in using it is often high initially, with many wanting to better understand PrEP and its potential side effects [5, 6, 9]. Since PrEP use is associated with stigmatized practices, such as drug use and having more than one sexual partner, women often perceive or fear negative judgments from others for taking PrEP [10, 11].

Cisgender women frequently underestimate their risk of acquiring HIV, which is often the result of not knowing their male sex partner’s HIV-relevant factors. This in turn makes it challenging for women and their providers to determine if PrEP might be beneficial [12]. Medical mistrust may interfere with women’s comfort level in discussing PrEP with providers [13]. Also, primary healthcare providers are often reluctant to discuss PrEP if they have limited time or are unfamiliar with prescribing it [14–16]. To many women, being referred to another specialty provider solely for PrEP is yet another hurdle [17]. Some PrEP medications are often available at low or no cost; however, other fees associated with PrEP health care visits (such as laboratory tests or visit copayments) can present financial obstacles for many PrEP-eligible women unless they see a provider who offers subsidized PrEP services [16].

Currently, there is limited information about behavioral interventions to promote PrEP uptake among cisgender women in the U.S. PrEP uptake often involves multiple steps, and this process is described in various ways across the literature. For this study, we used the PrEP care continuum as described by Nunn and colleagues, which includes: (1) identifying individuals at the highest risk for contracting HIV, (2) increasing HIV risk awareness among those individuals, (3) enhancing PrEP awareness, (4) facilitating PrEP access, (5) linking to PrEP care, (6) prescribing PrEP, (7) initiating PrEP, (8) adhering to PrEP, and (9) retaining individuals in PrEP care [18].

Findings from a few recent reports of single-arm pilot studies among women who could benefit from PrEP highlight some important challenges [19–21]. In New York City, Blackstock and colleagues found a major gap between PrEP interest (73%) and connecting women to PrEP care (6%), even when navigators attended appointments with participants [22]. In Philadelphia, Roth and colleagues found that initial acceptance of a PrEP prescription was high (88%), but retention at 24 weeks was low (44%) [21]. Other studies using chart review to examine uptake in specific clinical sites that offered PrEP to women found that the most common indication for prescribing PrEP was for those with a male partner living with HIV, and retention in care was poor [19, 23]. In a review of factors affecting PrEP implementation for women in the U.S., the authors noted that most barriers were social or structural, including cost, stigma, and medical distrust [24].

For women in the U.S., effective approaches to support the use of daily oral PrEP are urgently needed. Therefore, we designed and conducted the multiphase Just4Us study in Philadelphia and New York City (NYC), both priority jurisdictions targeted for Ending the AIDS Epidemic initiatives [25]. Findings from our formative research consisting of 41 in-depth interviews and 160 surveys [7, 11, 17, 26, 27], along with current literature and feedback from a community consulting group, informed intervention development, and is described in detail elsewhere [26].

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) to assess the Just4Us intervention. Feasibility and acceptability results have been reported previously [28]. This paper reports on the preliminary efficacy of PrEP uptake behavior [29].

Methods

Study Procedures and Setting/Study Population

In Philadelphia and NYC, from 11/2018 to 6/2019, cisgender women were recruited using various strategies, including face-to-face outreach at substance use programs, shelters, street outreach, social media and online postings (e.g., Craigslist), and referrals from enrolled women.

The eligibility criteria were based on CDC and New York State PrEP guidelines at the time of the study. Eligibility criteria were: assigned female sex at birth and identifying as female; being 18–55 years old; having had condomless vaginal or anal sex with a male partner in the past 3 months or having injected drugs in the past 3 months; and reporting at least one of the following: having a current male sex partner who injects drugs, who is HIV seropositive, who has sex with men, or who was incarcerated in the past 6 months; or reporting their own experiences in the past 6 months as having: shared injection equipment; used cocaine/crack cocaine, or another stimulant at least 1 ×/week; been in a medication treatment program for opioid use (methadone, buprenorphine, suboxone); exchanged sex for money, drugs, or services; met the criteria for alcohol dependency (defined as a score of 2 or higher on the CAGE [30]); diagnosed with chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis or a new diagnosis of genital herpes; or had 3 or more male sex partners. Women were excluded if they were currently pregnant, currently taking PrEP, planned to relocate out of the area within the next 3 months, did not understand and read English (at least at a 5th grade level), did not have access to a mobile phone, or had a positive rapid HIV test at the first study visit. The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at University of Pennsylvania and the New York Blood Center and had a Certificate of Confidentiality from NIH (CC-MH-16-257). Study visits took place in the research offices in Philadelphia and NYC.

Study Design

In this RCT, we compared the Just4Us-Education and Activities (E&A) arm, comprised of 12 mini-modules and follow-up phone calls, to the Brief Information arm (Info), during which participants were presented with information handouts on PrEP. Both arms, described in more detail below, were delivered to participants individually and in person by a trained Counselor–Navigator (C–N). We evaluated steps on the PrEP uptake continuum and PrEP initiation. As the E&A intervention content was guided by the Integrated Behavioral Model (IBM) as previously described [31], we also explored social-cognitive factors (e.g., knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, norms, self-efficacy, and intention) relevant to PrEP initiation behavior.

Study Visits

After written informed consent, all participants watched a brief informational video about PrEP for women [32], completed a computer-based baseline questionnaire, and received HIV counseling and an fourth generation rapid HIV test from a trained HIV counselor/data collector. This was followed by randomization in a 3:1 ratio into the E&A arm or Info arm. Randomization was performed centrally by the project statistician and implemented using opaque sealed envelopes. Envelopes were numbered and shipped to each study site. Balance between arms was maintained by use of randomly permutated blocks with variable block sizes of 4 and 8 (to allow for the 3:1 randomization ratio) and with stratification by the site [2]. At each site, a sealed envelope was opened, in consecutive order, indicating the study arm. Neither the staff nor participants were blinded to the study assignment. After randomization, participants met individually with the C–N who delivered either the E&A or Info arm PrEP intervention. Immediately after the intervention session, participants met again with the data collector to complete the post-intervention computerized questionnaire focused on assessing social-cognitive covariates. At 3 months post-enrollment, participants returned for a follow-up visit and completed a follow-up questionnaire on a computer. Participants were provided $50 for each baseline and 3-month visit.

Interventions

Based on the Integrated Behavioral Model [31] and the Theory of Vulnerable Populations [33], the E&A intervention included an in-person, individually-tailored, contextually relevant, technology-enhanced, 1–1.5 h-long information, motivation-enhancement, skill-building, problem-solving, and referral session with follow-up phone calls.. In both cities, during the time of the study, women could receive free PrEP care, including laboratory visits and prescriptions as provided by state and/or local programs or by using the pharmaceutical company’s PrEP assistance program. For some, this involved going to specific clinics or providers. The E&A intervention consisted of 12 mini-modules delivered individually to participants by the C–N and utilized a variety of modalities, including video, tablet activities, and physical props, lasting 60–90 min. Details about the development, content, and pre-piloting of the Jus-t4Us-E&A arm are described in a prior publication [26] After this initial session, participants in the E&A arm received additional navigation to support linkage to community-based PrEP care and a text-messaging program to promote adherence. Participants in both arms received a packet of handouts on PrEP facts, a list of providers known to prescribe PrEP, information on how to pay for PrEP, and other general health information materials. The Info arm participants met individually with the C–N, who provided a brief description of the handouts in the packet. This session lasted approximately 5–10 min. All intervention sessions were audio-recorded to monitor fidelity.

Training C–Ns and Monitoring the Quality and Fidelity of Intervention Sessions

The six C–Ns, all experienced staff members, were provided training on the content of both intervention arms, goals for each module of the E&A arm, facilitation strategies, and provided with Just4Us E&A and Brief Info intervention manuals. Subsequently, C–Ns had to achieve mastery in session facilitation as determined by two research team members rating video recordings of mock sessions. Ongoing supervision was provided during weekly team meetings. In addition, fidelity and quality were assessed by two study team investigators (AMT & BAK) who listened to the audio recordings of a subset of intervention sessions of both arms and across all C–Ns, using a standardized fidelity rating form. The first three intervention sessions conducted by each C–N were evaluated as well as subsequent sessions intermittently. The form used 5-point Likert response categories (poor to excellent) to assess the following: presentation skills (8 items), e.g., “Conveys ability to engage the participant”; knowledge and communication skills (13 items for the E&A arm; 11 items for the Info arm), e.g., “Able to deliver the intervention in a conversational way (not reading from manual)”; and adherence to module objective(s) depending on the arm (1 item for the Info arm; 12 items pertaining to each module for the E&A arm). There was also an open-ended comments section in which more specific feedback was provided. The C–Ns were given their completed fidelity and quality rating forms as part of ongoing supervision and feedback during the study.

Measures

Baseline Measures

Demographic, health, and PrEP-relevant sexual and drug behavior data were collected at baseline, including age, race/ethnicity, educational level, income, health insurance status, employment, financial instability, recent (past 3 months) injection drug use, condom use with vaginal and anal sex partners, transactional sex and seven relevant factors related to male sexual partners (e.g., had HIV; has sex with other men). Perceived HIV risk was assessed with the question “I believe I am currently at risk of getting HIV” with a 4-point Likert response set which was recoded as a binary outcome for relevant analyses (Disagree Strongly/Disagree vs. Agree/Agree Strongly). Drug use was assessed with 9 questions about any use of specific drugs in the past 3 months, such as heroin, crack cocaine, methamphetamine or other amphetamine, and opiates (such as Oxytocin, Percocet). PrEP awareness was assessed with a question asking participants if they had heard of PrEP prior to participating in this study.

Social-cognitive items, based on the Integrated Behavioral Model [31], were used to assess beliefs about PrEP initiation. We adapted previously developed scales for behavioral, normative, and control beliefs regarding their intention to start PrEP in the next 3 months with minor word changes to enhance clarity and additional items for some scales [27]. There were five items in the behavioral belief scale, e.g., “Starting PrEP will reduce my chances of getting HIV in the future (α = 0.803), four items in the normative belief scale, e.g., “My friends would approve of my starting PrEP” (α = 0.836), and nine items in the control belief scale, e.g., “I can talk to my provider if I need PrEP” (α = 0.703). All beliefs scales used 4-point Likert agreement response options. Higher scores on these scales indicated positive beliefs about PrEP initiation.

Other relevant social cognitive constructs were included in the questionnaire, as we have in prior research [11]. We assessed PrEP initiation intention defined as the response to a single 4-point Likert item (1 = Disagree Strongly to 4 =Agree Strongly) using the statement: “I plan to start PrEP in the next 3 months”. PrEP knowledge was assessed using thirteen questions with true versus false/don’t know response options, and an index of correct responses was created for analysis. PrEP stigma was assessed with a slightly modified Women’s PrEP Stigma scale [11] (α = 0.861) consisting of six items, e.g., “If I start PrEP, people might gossip about me,” all with a 4-point Likert agree/disagree response set. After adjusting for reverse coding on relevant items, higher values indicated greater anticipated stigma.

Immediate Post‑intervention Measures

The post-intervention questionnaire, given to all participants, included social cognitive variables, including the behavioral, normative, and control beliefs about starting PrEP, PrEP knowledge, and PrEP stigma. The C–Ns completed online logs after follow-up phone calls for Just4Us E&A participants only, which documented where women were on the PrEP continuum, and any challenges or barriers women reported related to accessing PrEP and described an updated action plan based on discussion with the C–Ns.

3‑Month Follow‑Up Measures

For all participants, the 3-month questionnaire included all questions asked at baseline (except demographics) with the addition of behavioral outcomes regarding steps on the PrEP continuum, which included: “Did you find a healthcare provider for PrEP?”; “Did you go to your appointment with a healthcare provider to discuss PrEP?”; “Did you get a prescription for PrEP?”; “Did you get a PrEP prescription filled?”; “Did you start taking PrEP?” with a yes/no response option. For each yes response, a follow-up question asked, “How satisfied were you with…?” with a 4-point Likert response set of “not at all satisfied” to “very satisfied,” which was recoded as a binary outcome for relevant analyses. Women who indicated they went to an appointment with a healthcare provider to discuss PrEP but did not receive a prescription were presented with an open-ended question: “Why did you not get a prescription for PrEP?” At the conclusion of the 3-month survey, participants were asked one exit interview question: “Tell me about your experiences in the past few months as you were thinking about starting PrEP?” Participants were asked an open-ended probe about how they made their decisions about PrEP. In response, some women provided specific feedback about their intervention session and how it influenced their PrEP decision-making. Exact quotes or paraphrased responses to the open-ended exit interview were typed in by the data collector.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the participants at baseline on socio-demographic variables, perceived risk, and PrEP-relevant behaviors. Cronbach’s alphas were generated at baseline for all belief scales. The Fisher’s exact test was used to assess between group (treatment arm) differences in attrition.

At baseline, we collected data on 83 participants, with 3 surveys lost due to technical issues with the data capture process, resulting in n = 80 surveys included for analysis at baseline. At the post-intervention session, 1 participant had to end the visit before completing the survey, resulting in n = 82 post-intervention surveys. At the 3-month follow-up, 8 participants were lost to follow-up, resulting in n = 75 surveys at 3-month follow-up. We conducted a complete case analysis and assumed missing data were missing completely at random (MCAR).

Post-intervention audio feedback data regarding quality and fidelity ratings of C–N-delivered intervention sessions were analyzed using descriptive statistics using Excel. In addition, descriptive statistics were used to summarize 3-month follow-up data pertaining to steps on the PrEP continuum for the sample as a whole, HIV prevention behaviors and PrEP intention for those who had not started PrEP. These analyses were completed in SPSS v27 or Excel v18.

The preliminary efficacy of the E&A intervention at 3-month follow-up compared with the Info intervention was tested using unadjusted and adjusted Poisson regression, binomial, or linear regression models for the count, binary, and continuous outcomes, respectively. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were fitted to assess the effect of the E&A intervention on the PrEP continuum behavioral outcomes at 3-month follow-up relative to Info intervention. Generalized estimating equations models with repeated measures were used to test the effect of the E&A intervention on behavioral, normative, and control beliefs, stigma, and knowledge and intention regarding PrEP initiation, calculated over immediate-post and 3-month follow-up. The adjusted regression models included the baseline measure of the respective social cognitive variable, study site, and age. All the models were fit with robust standard errors. Analyses were completed using SAS V9.4.

Content analysis was completed on 72 exit interviews: 94% (51/54) of the E&A participants and 100% (21/21) of the Info arm participants. Exit interview data were not collected for 3 participants either because the participant did not have time or did not want to respond. Content analysis of the open-ended survey responses and exit interview questions, performed by two team members, was used to classify similar responses. Exit interview data were analyzed to identify: (1) barriers, grouped according to the PrEP continuum, and (2) feedback linking the interventions to PrEP knowledge, skills and uptake behaviors. Any differences between the two team members’ categorizations were resolved through discussion until agreement was reached [34].

Results

Sample Characteristics

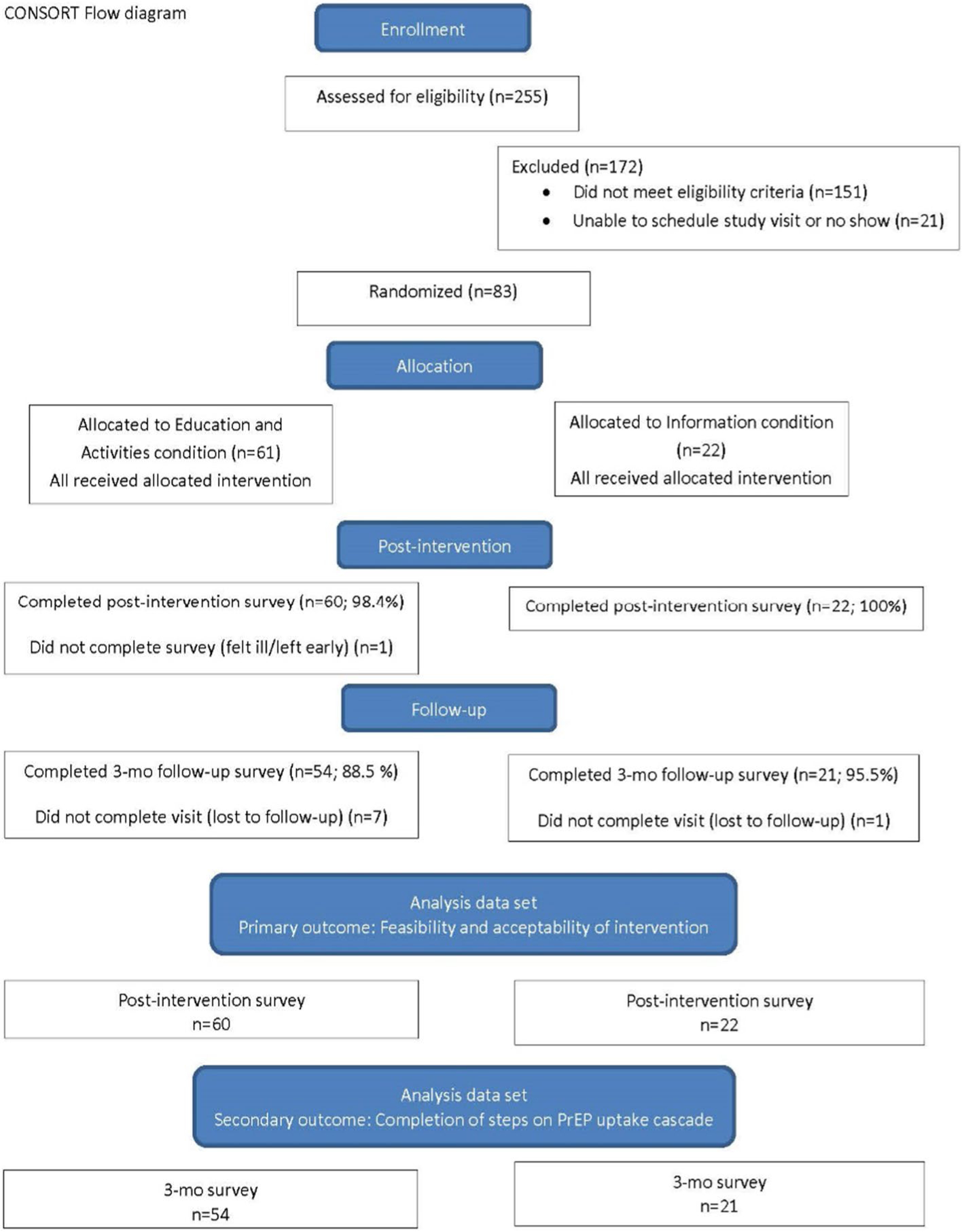

A total of 255 individuals were screened for eligibility; of those, 151 were not eligible (including one who tested positive for HIV at the initial study visit), and 21 did not attend the baseline visit. The remaining 83 were randomized, with 61 allocated to the E&A arm and 22 to the Info arm (Fig. 1 consort diagram).

Fig. 1.

Consort flow diagram for pilot randomized controlled trial

At baseline, the mean age of the randomized women was 37 (SD = 12) years, 79% identified as Black/African American, and 26% as women of Hispanic/Latina ethnicity (Table 1). Although 89% had health insurance, this group of PrEP-eligible women faced significant challenges on multiple levels. Most (83%) reported that they sometimes or very often did not have enough money for basic necessities (rent, food, utilities) in the prior 3 months. Almost half (49%) had spent at least one night in a shelter, temporary housing or a place not designed for sleeping in the prior 3 months. Alcohol and other drug use were prevalent, with 60% of the women reporting having 3 or more drinks per day and 51% using substances other than marijuana in the past 3 months. Sexual behaviors which placed women at increased likelihood of HIV exposure were also prevalent, with 74% having more than one partner in the past 3 months and 91% reporting inconsistent condom use. Over two-thirds (68%) reported using drugs or alcohol to get high or drunk before having sex in the prior 3 months, and 47% engaged in sex for money, drugs, goods, or other services. Although all the women in the study were PrEP-eligible at baseline, just over half (51%) believed they were at risk of getting HIV in the prior 3 months. More than half (53%) had not heard of PrEP prior to participating in this study. After receiving a brief explanation about PrEP necessary for study participation, more than three-quarters (79%) intended to use PrEP in the next 3 months. If starting PrEP in the next 3 months, 69% preferred to go to their own provider.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Total (n = 80)a M (SD) |

Just4Us E&A (n = 58) M (SD) |

Brief Info (n = 22) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37 (12) | 37 (12) | 39 (13) |

|

| |||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Black/African American | 63 /80 (78.8) | 46/58 (79.3) | 17/22 (77.3) |

| White/other | 17/80 (21.2) | 12/58 (20.7) | 5/22 (22.7) |

| Hispanic/Latina ethnicity | 21/80 (26.3) | 16/58 (27.6) | 5/22 (22.7) |

| Annual income | |||

| Less than $12,000 | 56/79 (70.9) | 41/57 (71.9) | 15/22 (68.2) |

| Has current health insurance (private or public) | 71/80 (88.8) | 53/58 (91.4) | 18/22 (81.8) |

| Past 3 months experienced financial insecurity | 66/80 (82.5) | 47/58 (81.0) | 19/22 (86.4) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school diploma | 22/80 (27.5) | 17/58 (29.3) | 5/22 (22.7) |

| A high school diploma or GED | 27/80 (33.8) | 18/58 (31.0) | 9/22 (40.9) |

| Some college/trade school, or more | 31/80 (38.7) | 23/58 (39.7) | 8/22 (36.4) |

| Employed | 20/80 (25.0) | 16/58 (27.6) | 4/22 (18.2) |

| Current Perceived HIV Risk | 41/80 (51.2) | 29/58 (50.0) | 12/22 (54.5) |

| PrEP Relevant Behaviors in the last 3 months: | |||

| Any Drug Use | 41/80 (51.2) | 29/58 (50.0) | 12/22 (54.5) |

| Had condomless sex (vaginal or anal) | 69/76 (90.8) | 51/54 (94.4) | 18/22 (81.8) |

| Had Multiple partners | 59/80 (73.8) | 42/58 (72.4) | 17/22 (77.3) |

Three participants in the Just4Us E&A arm were missing baseline data due to technical issues in data capture

Retention and Intervention Fidelity

The baseline data on 58/61 Just4Us E&A participants (95%) and all 22 Info session participants had an overall 96.4% completion across arms. Post-intervention questionnaires were completed by 60 (98.4%) E&A arm participants and 22 (100%) Info arm participants, with an overall 99% completion. The 3-month visit was completed by 75 participants for retention of 90.4% overall: 88.5% among Just4Us E&A arm participants and 95.5% among Info arm participants Fisher’s exact test, two-sided p-value = 0.675.

Facilitator audio feedback forms were completed by research team members for 14 E&A arm sessions and 7 Info arm sessions. Evaluations on the 1–5 scale of audited E&A arm sessions received a mean of 4.8 (SD = 0.29) for quality and 4.54 (SD = 0.52) for fidelity, and audited Info arms sessions received a mean of 4.98 (SD = 0.04) for quality and 5.00 (SD = 0.00) for fidelity.

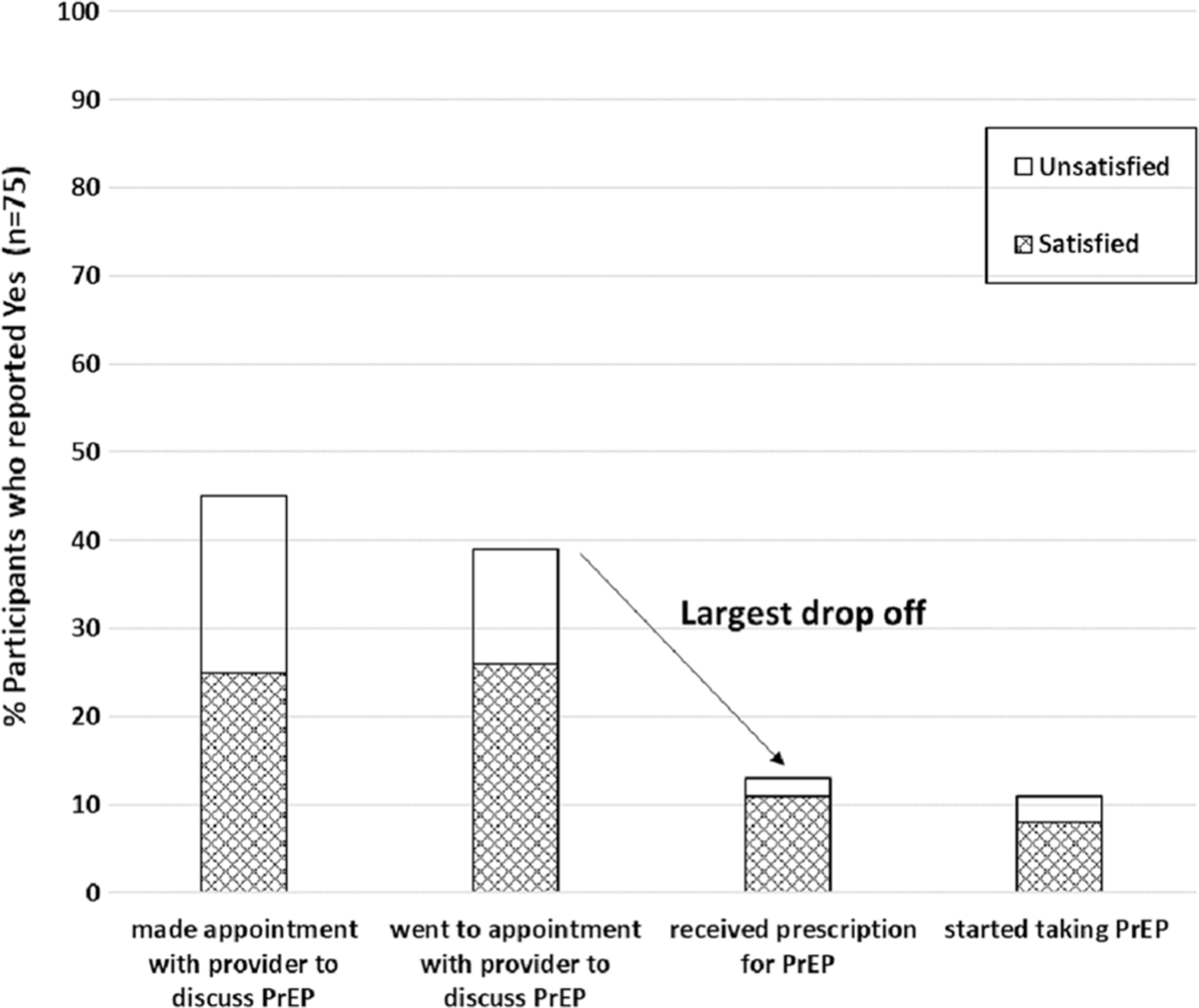

PrEP Care Engagement and Initiation

Of the 75 participants who completed a 3-month follow-up visit, almost half (45%) had made an appointment to see a provider to discuss PrEP, and 39% had attended an appointment with a healthcare provider to discuss PrEP. However, only 13% left the provider visit with a prescription for PrEP, and 11% started to use PrEP (See Fig. 2). Only 56% (19/34) who made an appointment with the provider to discuss PrEP and 66% (19/29) who saw a provider about PrEP were satisfied with the process. However, 80% (8/10) of the women who received a prescription for PrEP and 75% (6/8) who started PrEP were satisfied with the experience.

Fig. 2.

PrEP uptake continuum

In this pilot study, 11% of the participants in the E&A arm and 9% of the participants in the Info arm started PrEP during the 3-month follow-up period. However, there were no significant differences in the percent of women starting PrEP or engaging in any of the six steps of the PrEP continuum by study arm in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prep continuum outcomes by arm at 3-month follow-up, Just4us pilot trial (N = 75a)

| Outcome measured at 3-month (mo.) visit | Information (N = 21) |

Educ./activities (N = 54) |

Intervention effect |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa,b (95% CI) | |

| Outcome at 3 mos. F/U | ||||||

| Started PrEP | 2 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 1.19 (0.2, 6.4) | 1.07 (0.2, 6.1) |

| Steps in PrEP uptake continuum at 3 mos. F/U | ||||||

| Found health care provider for PrEP | 9 | 43 | 23 | 43 | 0.99 (0.4, 2.7) | 1.00 (0.36, 2.8) |

| Got information on how to pay for PrEP | 12 | 57 | 29 | 54 | 0.87 (0.3, 2.4) | 0.89 (0.3, 2.5) |

| Made appointment with health care provider | 9 | 43 | 25 | 46 | 1.15 (0.4, 3.2) | 1.12 (0.4 3.1) |

| Went to a health care provider | 11 | 52 | 18 | 33 | 0.45 (0.2, 1.3) | 0.44 (0.1, 1.2) |

| Got a prescription | 3 | 14 | 7 | 13 | 0.89 (0.2, 3.8) | 0.74 (0.2, 3.3) |

| Got prescription filled | 2 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 0.76 (0.1, 4.5) | 0.69 (0.1, 4.2) |

There was 1 individual from the Info arm and 7 from the E&A arm that were missing outcomes at 3-month follow-up

Odds ratio (OR) and asymptotic confidence intervals estimated from logistic regression, adjusted for study site and age

To illuminate the possible reasons for not starting PrEP (n = 67), we examined if women were choosing other strategies to prevent exposure to HIV over the 3 months study duration. Of the 67 women who reported that they had not started PrEP at the 3-month follow-up visit, 22 (33%) were using other ways to limit their likelihood of acquiring HIV: none had injected drugs in the past 3 months; 17 did not have vaginal or anal sex with a male partner in the past 3 months; and 5 always used condoms in the last 3 months.

Exploration of Social Cognitive Variables of PrEP Initiation by Study Arm

Table 3 reports the results of unadjusted and adjusted regressions modeling the intervention’s effect on social cognitive variables about starting PrEP using data collected at the immediate post and 3-month follow-up.

Table 3.

Social cognitive variables hypothesized to be associated with PrEP initiation, comparison by arm at immediate post intervention and 3-month follow-up

| Social cognitive variables | Post-intervention 22 Info, 58 Just4Us E&A |

3-Months 21 Info, 54 Just4Us E&A (see Note) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted β (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted β (95% CI) + | p value | Unadjusted β (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted β (95% CI) + | p value | |

| PrEP initiation behavioral beliefs | 0.01 (− 0.27, 0.29) N = 82* |

0.96 | 0.05 (− 0.22, 0.33) N = 79* |

0.67 | − 0.06 (− 0.30, 0.18) N = 75* |

0.62 | − 0.02 (− 0.27. 0.22) N = 72* |

0.83 |

| PrEP initiation normative beliefs | − 0.06 (− 0.40, 0.24) N = 82* |

0.70 | − 0.05 (− 0.38, 0.22) N = 79* |

0.60 | − 0.01 (− 0.36, 0.34) N = 75* |

0.96 | 0.001 (− 0.33, 0.33) N = 72* |

0.996 |

| PrEP initiation control beliefs | 0.16 (− 0.07, 0.46) N = 82* |

0.15 | 0.16 (− 0.06, 0.45) N = 79* |

0.13 | 0.15 (− 0.08, 0.40) N = 75* |

0.19 | 0.17 (− 0.05, 0.41) N = 72* |

0.13 |

| Intention to start PrEP next 3 mos | − 0.002 (− 0.43, 0.42) N = 82* |

0.98 | − 0.05 (− 0.52, 0.33) N = 79* |

0.66 | 0.07 (− 0.35, 0.61) N = 67* |

0.58 | 0.05 (− 0.36, 0.56) N = 65* |

0.66 |

| Women’s PrEP Stigma | − 0.01 (− 0.35, 0.32) N = 82* |

0.91 | 0.01 (− 0.26, 0.29) N = 79* |

0.91 | 0.05 (− 0.30, 0.45) N = 75* |

0.70 | 0.02 (− 0.30, 0.37) N = 72* |

0.85 |

| PrEP Knowledge | 0.15 (− 0.01, 0.31) N = 82* |

0.06 |

0.17 (0.01, 0.33) N = 79* |

0.04 | 0.11 (− 0.06, 0.28) N = 75* |

0.22 | 0.11 (− 0.07, 0.28) | 0.22 N = 72* |

PrEP initiation intention outcome at 3-month follow-up only include those who had not yet started PrEP (N = 67) and 65/67 had complete data, with 2 Just4Us participants missing baseline data

Denominators for each regression model

Standardized Beta and confidence intervals estimated from linear regression for the theoretical variables and Poisson regression for knowledge, adjusted for baseline value, study site, and age

For PrEP knowledge, the E&A arm had significantly greater knowledge post-intervention compared to the Info arm in the adjusted model. In the E&A arm, the mean knowledge index increased from 6.36 (SD = 4.02) at baseline to 10.22 (SD = 1.89) at post-intervention, while in the Info arm, the mean knowledge index changed from 7.09 (SD = 2.83) at baseline to 8.77 (SD = 3.37) at post-intervention. There were no other statistically significant differences between the two groups for behavioral, normative, control beliefs and for stigma (using multi-item scales) or PrEP initiation intention. The PrEP initiation intention variable at 3-month follow-up included only those who had not started PrEP (n = 67). Although not statistically significant, among those who had not yet initiated PrEP at 3-month follow-up (n = 67), a somewhat higher percentage in the E&A arm (21/48; 44%) intended to start PrEP in the next 3 months than those in the Info arm (7/19; 37%).

C–N Phone Call Logs for E&A Participants

Among the 60 Just4Us E&A participants who completed the post-intervention session, the C–Ns documented in their logs attempts to reach all participants with a follow-up phone call; however, actual contact was made with 30 participants for 1st calls. Of those, 14 received 2nd, and 3rd calls, and 8 received a 4th call. C–Ns were able to establish where women were on the PrEP continuum, identify barriers or challenges, and offer encouragement as well as concrete suggestions and support. Some women were not interested in starting PrEP, some were still trying to decide if PrEP was right for them, and others were in the process of starting PrEP. In response to women’s requests, the C–Ns reported delivering the following concrete support: providing additional information regarding PrEP for men; assisting in finding a provider who sees patients after 5 pm; calling a clinic and making an appointment; providing information about medical transportation programs; providing information about clinician resources for patients to bring to their provider; and calling a laboratory to determine why there was a delay in receiving PrEP lab results.

Exit Interviews at 3‑Month Follow‑Up (Both Arms)

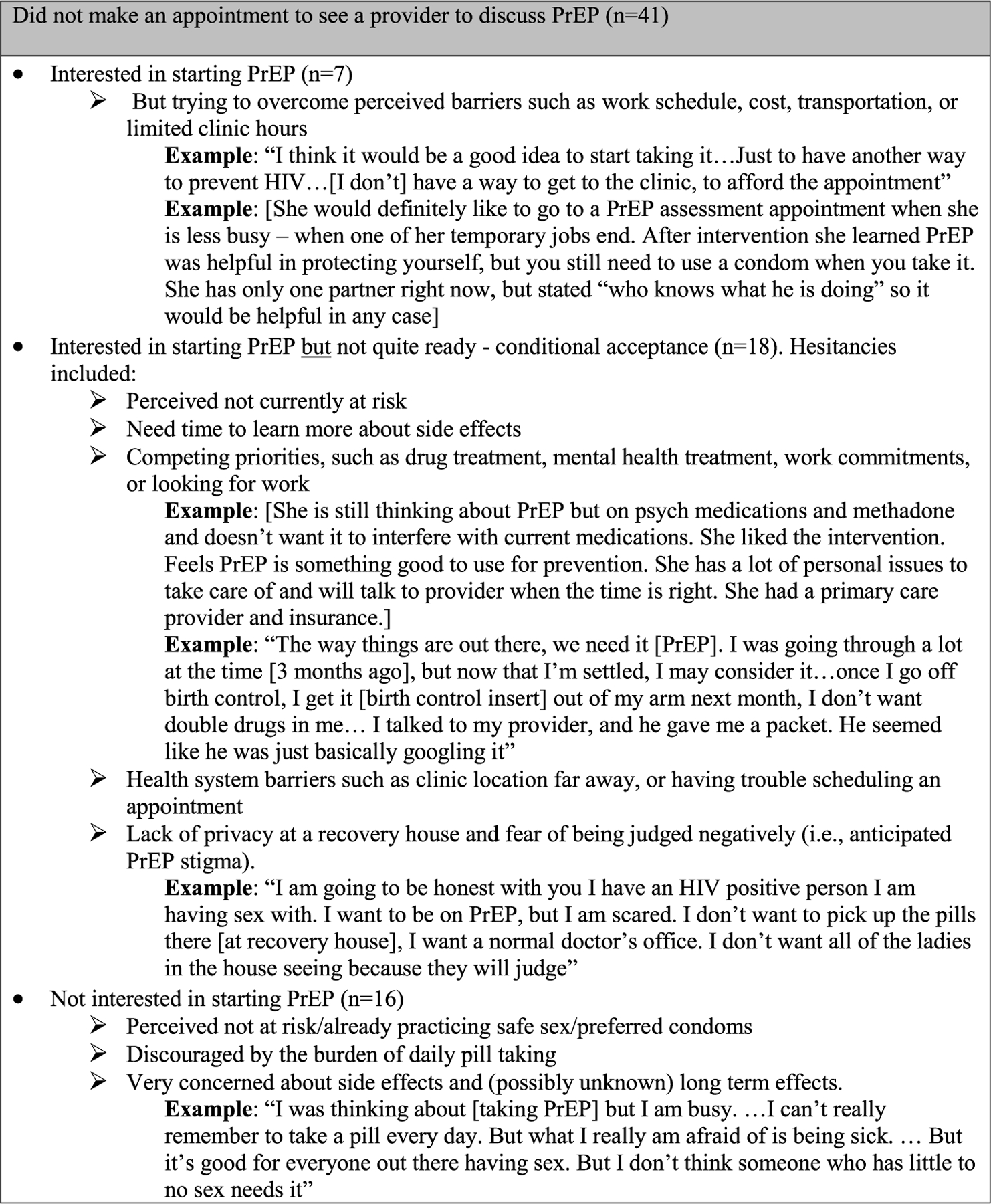

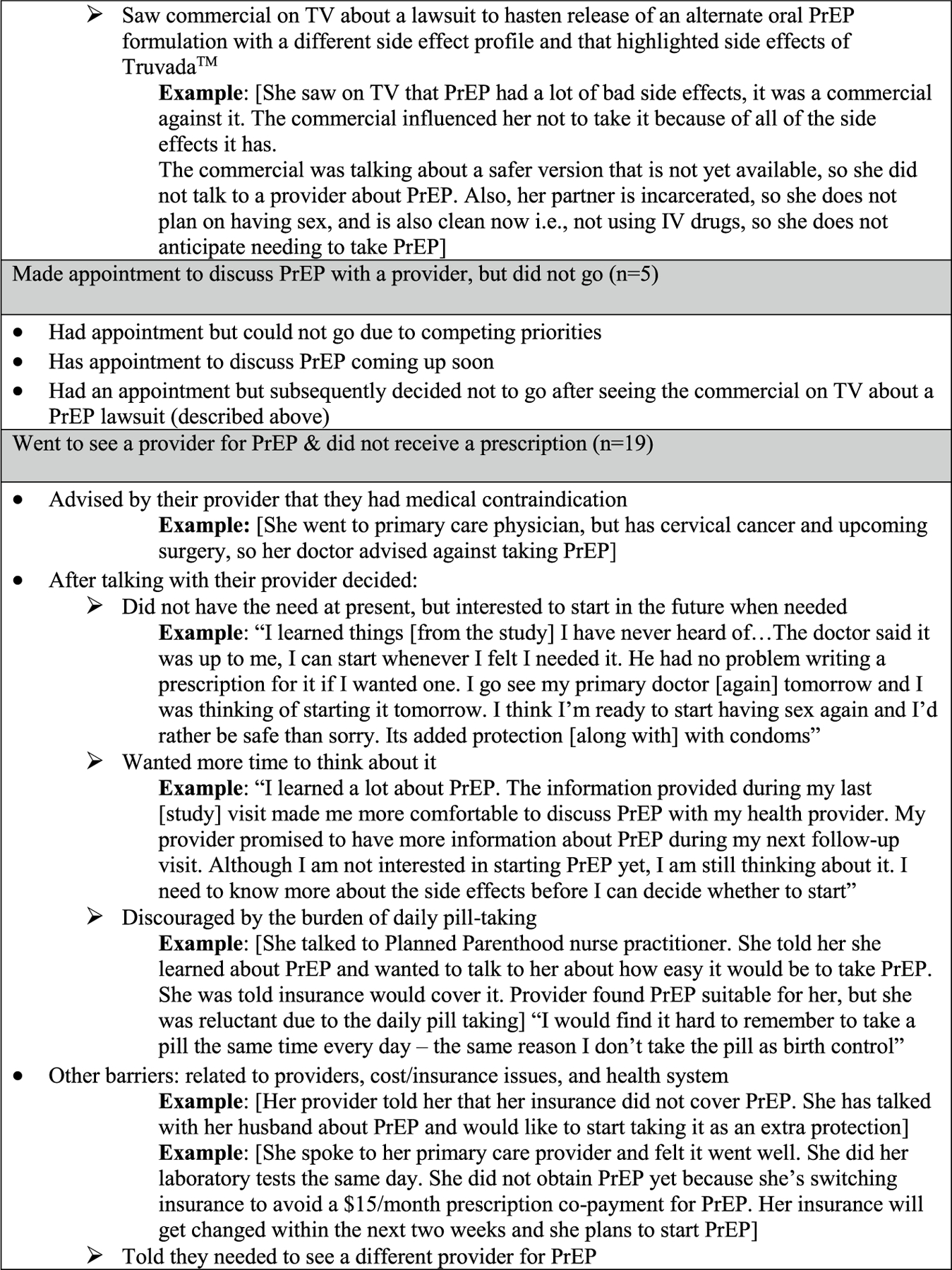

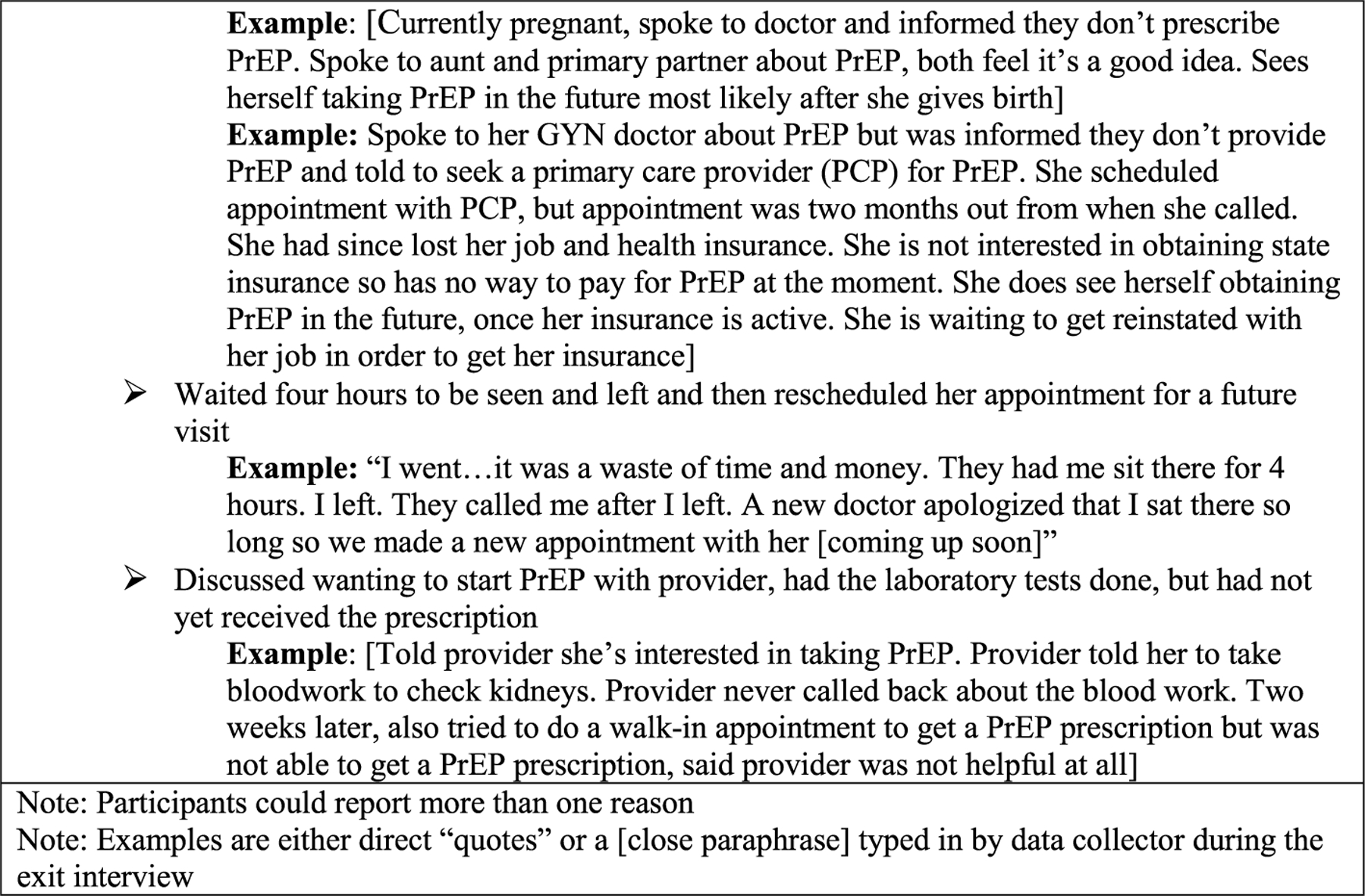

Assessment of PrEP access barriers and challenges, organized by steps on the PrEP continuum, revealed that many women were still in the process of considering PrEP at the 3-month time point. Most of those who had yet to make an appointment expressed continued interest in PrEP. While some wanted more time to determine if PrEP was right for them, others were trying to cope with competing priorities, such as drug treatment, and many encountered various healthcare system barriers. Among those who did see a provider for PrEP, a few were advised by their provider not to take PrEP due to other health issues, several more wanted to wait, and some were referred elsewhere for PrEP or faced other barriers in accessing health care (see Fig. 3 for more detail and exemplar comments from the participants).

Fig. 3.

Participants’ reasons for non-progression on the prep continuum at 3-month follow-up (with representative comments)

Approximately a third of participants reported the impact of the intervention on their knowledge, skills, and behaviors related to PrEP uptake in their open-ended responses. The most common impact reported in both arms was increased knowledge about PrEP, with several indicating they first learned about PrEP through the intervention and became aware that PrEP was for HIV prevention. For example: “I never knew of PrEP and learned about it from the study,” or “You guys helped me learn more about it. It’s something I never knew about, and I’m 50.”

There were some varied responses by the study arm about the intervention content. A couple of women in the Info arm indicated they wanted more information about PrEP side effects, as indicated by the following quote, “I learned that PrEP was helpful in protecting yourself, but that you still need to use a condom when you take it. I would have liked to learn more about the side effects of PrEP.” A few women noted learning about PrEP was good for women who were unable to choose to use a condom or did not know the HIV status of their partner, as indicated in the following response: [She learned about PrEP and how] “it’s for people who don’t have HIV and want to protect themselves with PrEP in case they don’t use condoms or don’t know the [HIV] status of their partner.” A few other women mentioned through the E&A intervention session they learned new skills, such as how to speak to others, including providers, about PrEP. For example: [The participant says that the list of questions, FAQ about PrEP, and other information she received in her packet have helped her talk to her provider and others about PrEP]; and [The participant spoke to her provider, but the provider had limited information about PrEP. The study provided more information than her primary care provider]. In addition, several women who received the E&A intervention indicated their intervention session led them to increase their safer sex behaviors (other than PrEP), as evidenced by this quote: [since the intervention] “I have asked more questions about my partners’ sexual experiences. I have used more condoms than before, but I still have unsafe sex practices” or fostered or solidified their decision to start taking PrEP, for example: [She decided she wanted PrEP after the intervention].

Summary of Key Findings

This RCT pilot study was conducted among PrEP-eligible women not currently using PrEP who were recruited in community settings in two cities with HIV rates higher than the national average [25]. Among these women, awareness of PrEP was moderately low at baseline (47%), and none had previously used PrEP. We compared a short PrEP information session (Info arm @ 5–10 min) with an individually tailored theory-based PrEP information, motivation, and skills-based session (E&A arm @ 1 h) plus phone call and text-based follow-up. As such, both arms received PrEP content. At the 3-month follow-up, in the sample as a whole, 45% made an appointment with a provider for PrEP, 39% went to see a provider for PrEP, 13% were given a prescription, and 11% started PrEP, indicating many women interested in PrEP did not receive a prescription from their chosen provider. There were no significant differences between the two groups in PrEP initiation or other steps on the PrEP continuum. However, there was a significant difference in PrEP knowledge immediately after the intervention session favoring the E&A arm, but this difference was no longer evident at the 3-month follow-up. The 3-month retention rate was very good (90%), and the fidelity and quality evaluations were high.

Discussion

Although we did not find statistically significant differences in PrEP initiation by group, 45% of participants made an appointment to see a provider for PrEP, and based on the exit interviews, many were still in the process of accessing PrEP. In addition, our findings highlight that some of the social-cognitive mechanisms (e.g., knowledge) hypothesized to influence PrEP uptake among cisgender women were significantly improved in the Just4Us E&A arm at the post-intervention evaluation in comparison to the Info arm. Currently, to our knowledge, there are no other published reports of findings from RCTs of interventions to support cisgender women in the US in starting PrEP. Given this was a pilot RCT not powered for efficacy, our results are encouraging. A larger sample and longer follow-up period are needed to evaluate the efficacy of Just4Us E&A vs. Info arm more definitively with regard to PrEP uptake.

All participants in the study were provided with HIV testing and counseling, and the Info comparison group also received PrEP information, including how to pay for PrEP and a list of local PrEP providers. As such, our comparison arm may have provided sufficient support for some women interested in PrEP to complete the series of tasks needed to obtain PrEP or to choose an alternate strategy for HIV prevention. For some other women, the Just4Us E&A intervention was not enough to support their PrEP uptake by the 3-month follow-up. Future research is warranted as we still do not know which arm was most effective.

In addition, it would be important to explore what “dose” of PrEP support is needed. The “dose” needed may vary according to women’s perceptions (e.g., level of willingness), needs/resources (e.g., competing priorities, such as drug treatment), and provider/health system/access issues (e.g., finding a PrEP-friendly provider). Exit interviews indicated many of the women reported substantial health system barriers, including transportation, insurance, cost, and limited clinic hours. For women in the E&A arm, the C–N s were able to provide women with more information and workable solutions to overcome such barriers during the follow-up phone calls. This suggests personalized navigation support, such as this, is very important to address the multilevel factors that influence PrEP uptake for cisgender women.

Carrying out most behaviors (e.g., PrEP initiation) often involves a series of actions (e.g., the PrEP continuum). However, encountering a greater number of sequential hurdles can weaken the intention-to-behavior pathway [31]. Therefore, simplifying the process of acquiring PrEP would go a long way toward improving PrEP access for women. In California, PrEP assessments and initial prescriptions are available at pharmacies [35]. In the Project SHE demonstration study, PrEP prescriptions were initially made available to women at a syringe exchange site in Philadelphia [21]. Integrating PrEP into services women already use reduces the burden of multiple appointments, mitigating their need to choose among competing priorities with limited resources. Making PrEP available in key community locations would be beneficial for greater PrEP uptake.

Nearly half of those seen at 3 months (n = 75) had made an appointment to see a provider about PrEP, which is a positive indicator. However, we found a considerable drop off along the PrEP continuum between scheduling an appointment (45%) to receiving a prescription for PrEP (13%). According to our exit interviews, some women made an appointment, found a way to get there, and talked to their provider about PrEP, only to be told to go elsewhere for PrEP, thus having to repeat multiple steps in the continuum. Notably, almost 70% of the women had a preference for seeing their own primary care providers for PrEP, yet many of these providers had limited PrEP knowledge and/or comfort in providing PrEP, as has been reported previously [17]. Similar drop off on the PrEP continuum was reported in the PREP-UP study (n = 52), conducted in NYC with cis- and transgender women attending syringe-exchange or sex worker programs, who received a theory-based education, counseling, and navigation support program, demonstrating 25% scheduled an appointment, 6% attended and none were prescribed PrEP [22]. These findings are consistent with other studies indicating primary care and reproductive care providers often have limited knowledge and comfort in prescribing PrEP [14, 36, 37]. In addition, women may incur co-pays, lab fees, or other expenses, which could be avoided by seeking care where PrEP services are subsidized. Therefore, it would be important to emphasize to women to see a PrEP-informed and subsidized provider. Also, arming women with the needed information, skills, and resources to advocate for themselves when speaking with any provider could further strengthen PrEP uptake interventions aimed at cisgender women. Our findings also suggest the need for fostering PrEP implementation into routine primary and reproductive health care. Further implementation science and policy research is needed to identify best practices for delivering PrEP in these settings.

It is noteworthy that at the time of our 3-month follow-up study visit, 42% of those who had not yet started PrEP (n = 28/67) intended to start PrEP in the subsequent 3 months. This suggests there is a continued need for behavioral interventions such as Just4Us to offer some women PrEP uptake support beyond the 3-month time frame that we examined in this pilot study, such as offering booster sessions. Such booster sessions should be tailored to the specific barriers women encounter on the path to seeking PrEP.

Markedly, while all women (n = 83) were PrEP-eligible at baseline, 33% of those who did not start PrEP (n = 67) at 3 months were using other safe sex strategies, which may have reduced their immediate perceived need and interest in PrEP. We found women go through phases when they are able to practice other HIV prevention strategies, such as not sharing injection equipment, practicing abstinence, or when having intercourse using condoms consistently. Our exit interview data showed some women did not see a need for PrEP during the 3 months following enrollment but indicated an interest in using PrEP in the future should their situation change. These findings echo previous work that highlights how women’s safer sex practices (which relate to their perceived need for PrEP) change over time, as it did in our study [38]. Risk-based behavioral screening focused on prior behaviors may miss some women who plan to make a change in their sexual practices (e.g., from previously abstinent to sexually active). Furthermore, a perceived need for PrEP could be enhanced by wide-spread messaging (in the community and with providers) that frames PrEP as a way to take control of one’s sexual health and to reduce the worry about acquiring HIV. Allowing informed potential PrEP users to ask for and receive PrEP would decrease the stigma associated with risk-based behavioral screening and could lead to greater uptake [39]. In hindsight, perhaps a more realistic goal for a study such as this one, rather than PrEP initiation, would be informed PrEP-decision-making that is contextualized to women’s lives.

At the time the study was conducted, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) was the only oral antiretroviral medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for cisgender women and available by prescription for PrEP [40]. Long-acting PrEP agents are becoming available with the recent approval of injectable cabotegravir (CAB) [41]. Long-acting alternatives to daily oral PrEP highlight the need for future tailored interventions that provide information about available PrEP formulations and support individual choices and preferences. In our exit interviews, some women in this study were not interested in PrEP due to recognizing their inability to take a daily pill. There is clearly a need to offer women different PrEP options and, if made widely available, will likely improve uptake and adherence, as suggested by analogous experience with long-acting reversible contraceptives [42].

This study had several limitations. Participants self-completed survey responses, so social desirability may be a potential source of bias. To help offset that possibility, surveys were completed online, and data collectors did not provide intervention content as C–Ns. Since we assumed data were missing completely at random, there may be potential bias from excluding participants with missing data. Also, there was only partial attention control: while participants in both arms received an in-person session with a C–N more time was spent with the E&A arm participants, so any differences between arms may at least in part be attributed to this difference.

Although PrEP is often referred to as a woman-controlled safer sex option, our findings suggest PrEP services, as currently structured, are most often “health system-controlled” such that before women can take control of this potentially life-saving HIV prevention modality, they first need to overcome many health system-controlled aspects of distribution and access.

Conclusion

Just4Us shows promise as a woman-focused PrEP-uptake intervention. The next steps are intervention refinement based on these results with the goal of promoting women’s informed decision-making about PrEP and addressing barriers to PrEP access. To more fully assess the efficacy of the Just4Us E&A intervention, a study with a larger sample and longer follow-up is needed. Incorporating content on new PrEP formulations, enhanced tailoring, and booster sessions should also be considered. Combining an intervention such as Just4Us-E&A with favorable implementation strategies would provide the most optimal approach to promoting PrEP uptake for cisgender women.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the participants who agreed to take part in this research. Thank you to the outstanding staff who make this work possible.

Funding

This study was funded by 1R34MH108437-01A1 (PI: Teitelman) and P30 AI 045008 (PI: Coleman).

Footnotes

Clinicaltrials.gov registration NCT03699722: A Women-Focused PrEP Intervention (Just4Us).

Declarations

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV in Women2021, https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV and African American People https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html; 2021.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 Update: a clinical practice guideline. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf 2018.

- 4.Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity-United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(41):1147–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill LM, Lightfoot AF, Riggins L, Golin CE. Awareness of and attitudes toward pre-exposure prophylaxis among African American women living in low-income neighborhoods in a Southeastern city. AIDS Care 2020;37:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson AK, Fletcher FE, Ott E, Wishart M, Friedman EE, Terlikowski J, et al. Awareness and intent to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among African American women in a family planning clinic. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2020;7(3):550–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teitelman AM, Tieu H-V, Flores D, Bannon J, Brawner BM, Davis A, et al. Individual, social and structural factors influencing PrEP uptake among cisgender women: a theory-informed elicitation study. AIDS Care 2021;34:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walters SM, Reilly KH, Neaigus A, Braunstein S. Awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women who inject drugs in NYC: the importance of networks and syringe exchange programs for HIV prevention. Harm Reduct J 2017;14:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C, McMahon J, Simmons J, Brown LL, Nash R, Liu Y. Suboptimal HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness and willingness to use among women who use drugs in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav 2019;23(10):2641–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabrese SK, Dovidio JF, Tekeste M, Taggart T, Galvao RW, Safon CB, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis stigma as a multidimensional barrier to uptake among women who attend planned parenthood. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;79(1):46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chittamuru D, Frye V, Koblin BA, Brawner B, Tieu H-V, Davis A, et al. PrEP stigma, HIV stigma, and intention to use PrEP among women in New York City and Philadelphia. Stigma Health. 2020;5(2):240–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Calabrese SK, Willie TC, Galvao RW, Tekeste M, Dovidio JF, Safon CB, et al. Current US guidelines for prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) disqualify many women who are at risk and motivated to use PrEP. JAIDS 2019;81(4):395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tekeste M, Hull S, Dovidio JF, Safon CB, Blackstock O, Taggart T, et al. Differences in medical mistrust between black and white women: implications for patient-provider communication about PrEP. AIDS Behav 2019;23(7):1737–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner L, Roepke A, Wardell E, Teitelman AM. Do you PrEP? A review of primary care provider knowledge of PrEP and attitudes on prescribing PrEP. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2018;29(1):83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson K, Bleasdale J, Przybyla SM. Provider–patient communication on pre-exposure prophylaxis (Prep) for HIV prevention: an exploration of healthcare provider challenges. Health Commun 2020;36:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang C, McMahon J, Fiscella K, Przybyla S, Braksmajer A, LeBlanc N, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation cascade among health care professionals in the United States: implications from a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2019;33(12):507–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson GY, Darlington CK, Van Tieu H, Brawner BM, Flores DD, Bannon JA, et al. Women’s views on communication with health care providers about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention. Cult Health Sex 2021;24:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, Mayer KH, Mimiaga M, Patel R, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS (London, England) 2017;31(5):731–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blackstock OJ, Patel VV, Felsen U, Park C, Jain S. Pre-exposure prophylaxis prescribing and retention in care among heterosexual women at a community-based comprehensive sexual health clinic. AIDS Care 2017;29(7):866–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dale SK. Using motivational interviewing to increase PrEP uptake among black women at risk for HIV: an open pilot trial of MI-PrEP. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2020;7(5):913–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth AM, Tran NK, Felsher MA, Gadegbeku AB, Piecara B, Fox R, et al. Integrating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis with community-based syringe services for women who inject drugs: Results from the Project SHE demonstration study. JAIDS 2020;86:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackstock OJ, Platt J, Golub SA, Anakaraonye AR, Norton BL, Walters SM, et al. A pilot study to evaluate a novel pre-exposure prophylaxis peer outreach and navigation intervention for women at high risk for HIV infection. AIDS Behav 2020;25:1411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theodore DA, Zucker J, Carnevale C, Grant W, Adan M, Borsa A, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis use among predominantly African American and Hispanic women at risk for HIV acquisition in New York City. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2020;31(1):110–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley ELP, Hoover KW. Improving HIV preexposure prophylaxis implementation for women: summary of key findings from a discussion series with women’s HIV prevention experts. Women Health Iss 2019;29(1):3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control. Ending the AIDS Epidemic-Juris-dictions, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/endhiv/jurisdictions.html.

- 26.Teitelman AM, Koblin BA, Brawner BM, Davis A, Darlington C, Lipsky RK, et al. Just4Us: development of a counselor-navigator and text message intervention to promote PrEP uptake among cisgender women at elevated risk for HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2021;32(2):188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teitelman AM, Chittamuru D, Koblin BA, Davis A, Brawner BM, Fiore D, et al. Beliefs associated with intention to use PrEP among cisgender US women at elevated HIV risk. Arch Sex Behav 2020;49:2213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tieu H, Nandi V, Ortiz G, Lucy D, Stewart K, Englert N, Brawner B., Iwu E, Davis A, Koblin B, Teitelman A, editor Feasibility and acceptability of Just4US, a woman-focused intervention to increase PrEP uptake and adherence among PrEP-eligible women in NYC and Philadelphia. 23rd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2020: Virtual), July 6–10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, Bond CM, Hopewell S, Thabane L, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016;355:i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach New York: Psychology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.HIVE. PrEP for Women with Dr. Nelly Mugo: HIVE Online | Feb 28, 2014 | PrEP Implementation; 2014. [<iframe title=“vimeo-player” src=“https://player.vimeo.com/video/186448201“ width=“640” height=“360” frameborder=“0” allowfullscreen></iframe>]. Available from: http://www.hiveonline.org/?s=mugo.

- 33.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res 2000;34(6):1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charmaz K Constructing grounded theory 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.California Legislative Information. Senate Bill No. 159. 2019. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB159.

- 36.Seidman D, Carlson K, Weber S, Witt J, Kelly PJ. United States family planning providers’ knowledge of and attitudes towards preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a national survey. Contraception 2016;93(5):463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sales JM, Cwiak C, Haddad LB, Phillips A, Powell L, Tamler I, et al. Brief report: Impact of prep training for family planning providers on HIV prevention counseling and patient interest in PrEP in Atlanta, Georgia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019;81(4):414–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Namey E, Agot K, Ahmed K, Odhiambo J, Skhosana J, Guest G, et al. When and why women might suspend PrEP use according to perceived seasons of risk: implications for PrEP-specific risk-reduction counselling. Cult Health Sex 2016;18(9):1081–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golub SA. PrEP stigma: implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(2):190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hodges-Mameletzis I, Fonner VA, Dalal S, Mugo N, Msimanga-Radebe B, Baggaley R. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in women: current status and future directions. Drugs 2019;79(12):1263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Injectable Treatment for HIV Pre-Exposure Prevention. : FDA Newsroom; 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announceme nts/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-preve ntion.

- 42.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374(9):843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]