Abstract

Objective

To investigate the prognostic value of illness perception (IP) on knee pain, quality of life (QoL) and functional level in elderly individuals reporting knee pain.

Design

A prospective cohort study of 1552 elderly with knee pain comparing two previously established clusters based on the Brief Illness Perception questionnaire. Cluster 1 (“Concerned optimists” [hypothesized unfavorable profile]; n = 642) perceived their knee pain as a greater threat to them than Cluster 2 (“Unconcerned confident” [hypothesized favorable profile]; n = 910). Primary outcome was the change from baseline to year 2 in the KOOS Pain subscale. Secondary outcomes were changes from baseline in quality of life (EuroQol-5 Domain and EQ VAS) and in the KOOS subscales Symptom, Activities of Daily Living, Knee-related QoL and Sports and recreation. Analyses were done on the original Intention-To-Survey (ITS) population, using repeated measures mixed linear models.

Results

Among the ITS population, 841 (54%) responded to the 2-year survey. There was a statistically significant but clinically irrelevant cluster difference in the 2-year change from baseline in KOOS pain (mean difference: 6.0 KOOS points [95% CI: 7.3 to −4.7]) explained by a minor improvement in Cluster 1: (6.2 points) and no changes in Cluster 2: (0.2 points). Comparable results were found across the secondary outcomes. Clinically irrelevant cluster changes in IP were seen.

Conclusion

In a cohort of people with knee pain, IP phenotype (i.e., Clusters) were of no prognostic value for the 2-year changes in pain, function, and QoL. Targeting IP may not be relevant in this patient population.

Trial registration number and date of registration

The Frederiksberg Cohort study was pre-registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03472300) on March 21, 2018.

Keywords: Illness perception, Knee pain, Cluster analyses, Prognostic factors, Quality of life, Cohort study

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent arthritic condition in the global population over 60 years of age with knee OA as one of the highest contributors of years lived with disability [1,2]. Symptoms of knee OA have been found prevalent in around 22% of people over the age of 40 [3] and people suffering from knee OA often report seriously affected functional level and quality of life [4,5]. So far, no treatments have been successful in delaying or preventing the development of OA [6]. Thus, current treatments are mostly aimed at managing symptoms such as knee pain and stiffness and improving functional level [7]. As the effects of recommended treatments are small-to-moderate and vary substantially among patients, focus within recent research has turned towards exploring risk factors of severe knee pain and OA development in subgroups of patients [8,9]. One way of doing this is by phenotyping patients based on different biological or psychological measures and following these phenotypes to see if and how OA pain develops with an underlying aim of targeted management [[10], [11], [12], [13]].

Some studies have aimed at phenotyping patients based on environmental, clinical, and biochemical markers [[14], [15], [16]], while others have explored psychological factors such as illness perception (IP) [17]. Longitudinal studies on patients with hand OA [18], knee OA [19], and low back pain [20] have found illness perceptions to be predictive of pain intensity and functional level. In a cohort of 214 patients with symptomatic OA at multiple sites, Kaptein et al. [21] found that patients sharing a similar profile of negative IP had significantly worse functioning after 6-years than patients sharing a more positive IP profile. This suggests that IP might be used to identify individuals with a greater need of support and management.

In our recent cross-sectional study among 1552 elderly with pre-OA (knee pain but not necessarily a diagnosis of knee OA) [22], we identified 2 clusters of individuals based on IP levels with one cluster having a significantly more negative IP (threatening view of their knee pain) than the other cluster. Participants in this cluster reported significantly higher pain intensities, lower functional level, worse quality of life (QoL) and use of more treatments for knee pain. Although the results support the findings of Kaptein et al. [21], a causal link between IP and knee pain could not be established due to the cross-sectional nature of the study.

Accordingly, the aim of this study was to establish whether a negative IP at baseline was of prognostic value regarding pain, quality of life and other knee symptoms over 2 years among elderly with knee pain. We hypothesized that the cluster perceiving their knee pain as a greater threat to them at baseline (i.e., a more unfavorable profile) would have larger deteriorations over 2 years in knee pain, function and QoL) than the cluster perceiving their knee pain as a minor threat to them (i.e., a more favorable profile).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

This cohort study represents the first longitudinal reporting of this observational study - The “Frederiksberg Cohort” [23]. This cohort was initiated in 2018 with planned yearly data collections until 2028. Baseline data collection for this study was completed between September 6, 2018 and October 2018 with the 1- and 2-year follow-ups were completed in October 2019 and 2020, respectively [22].

Data were collected through a thoroughly tested survey sent once per year to all citizens aged between 60 and 69 years at baseline and living in Frederiksberg Municipality, in Copenhagen, Denmark (n = 8204). The survey was sent through the public “Digital Post” system (electronic mailbox for letters from Danish authorities) linked to the individual's Personal Identification number. Responses were managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tool [24,25]. One reminder was sent in case of missing or incomplete response.

2.2. Participants

The inclusion criteria included age between 60 and 69 years, living in the Frederiksberg Municipality (in 2018), being able to read and understand Danish and having access to the Digital Post service. Participants eligible for this follow up study had to report knee pain at baseline. Knee pain was defined as a positive answer to the question: “Have you experienced any pain from your knee/knees during the last month (at work or at rest)?”. All participants reporting: “pain when sitting still”, “pain when moving” or “pain both when moving or sitting still” were included. Participants reporting no pain from their knee/knees during the last month were not included, regardless of eventual earlier episodes of knee pain.

2.3. Prognostic variable: The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire

To assess IP, we used the Danish version of The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ). B-IPQ is a generic nine-item questionnaire developed to rapidly assess the cognitive and emotional representations in a variety of illnesses [26]. The first eight items are scored on a 1–10 numeric rating scale with descriptors at either end with 1 being no perceived threat in items 1 “Consequences”, 2 “Timeline”, 5 “Identity” (the symptoms attributed to the disease), 6 “Concern”, and 8 “Emotions” and highest perceived threat in items 3 “Personal Control”, 4 “Treatment Control”, and 7 “Coherence”. A total score is not recommended and no minimally clinically relevant difference (MCID) has been defined. As recommended, the term “illness” was replaced with “knee pain/discomfort”. Discomfort was added as we wished to (also) include participants with only minor or intermittent pain. Item 9 is a free text field where the respondent can formulate their own beliefs about their condition (cause) [26]. We only used the first eight items in our analysis. The questionnaire has been described in detail in Ginnerup-Nielsen et al. [22].

At baseline, based solely on B-IPQ scores, we identified two clusters via a hierarchical cluster analysis (Ward's method), using squared Euclidean distance to determine the optimal number of clusters that were afterwards validated in a K-means analysis. Respondents in the two clusters clearly differed in terms of their IP: Cluster 1 named “Concerned optimists” perceived their knee pain as a great threat to them (i.e. participants had a hypothesized unfavorable profile) and Cluster 2 named “Unconcerned confident” perceived their knee pain as a minor threat to them (i.e. had a hypothesized favorable profile) [22].

2.4. Outcomes

The prespecified primary outcome measure was change from baseline in the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) pain subscale [27]. Other major (secondary) outcomes included changes from baseline in the EuroQoL five dimensions (EQ-5D-3L) health related quality of life index [28] as well as in the EQ visual analogue scale (EQ VAS) [29] and the KOOS subscales “Symptoms”, “Activities of Daily Living”, “Knee-related Quality of Life (QoL)” and “Sports and Recreation”.

The KOOS assesses the patient's opinion about their knee and associated problems [27]. It is patient reported and can be used to assess groups and to monitor individuals. The KOOS consists of 42 items covering five domains: Pain (nine items), Symptoms (seven items), physical functioning in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) (17 items), Sports and Recreation (five items), and knee related QoL (four items). The KOOS uses a five-point Likert scale scoring system (ranging from 0 (least severe) to 4 (most severe). A normalized score is calculated for each domain with 100 indicating no symptoms or functional impairment and 0 indicating extreme symptoms or functional impairment [30]. Minimal important change (MIC) for the KOOS is suggested to be 8–16 points [[31], [32], [33]].

The EuroQoL five dimensions (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaire assesses QoL. The questionnaire contains 5 questions concerning the domains: Mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression. We used the version with response options based on a 3-points Likert scale. Answers are calculated as an index with −0.624 corresponding to being seriously affected in all domains and 1.000 corresponding to not being affected at all [28]. No official MCID for individuals with knee pain has been defined. A Danish validated version of the questionnaire is available [34]. We further used the EQ VAS. The scale records the respondent's self-rated health on a visual analogue scale (0–100) with endpoints labelled ”the worst health you can imagine” and ”the best health you can imagine” [35].

2.5. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed on the intention-to-survey (ITS) population, including all participants reporting knee pain at baseline [22]. Given that only participants still reporting knee pain were requested to respond to the KOOS questionnaire at follow up, we had obvious missing data for KOOS answers from those participants who were still part of the cohort but did not report pain in year 1 and 2. For these participants missing KOOS data were imputed based on age, sex and BMI matched scores in a healthy population without any knee ailments [36]. We did not impute data on non-responders.

Between-cluster comparisons of continuous variables were analyzed using repeated measures, mixed linear models including cluster and year as fixed factors, as well as the cluster × year interaction. Mixed models assume that the missingness over time is independent of unobserved measurements, but dependent on the observed measurements; this assumption corresponds to data “Missing At Random” (MAR) phenomenon. Analyzing repeated measurements using mixed models is considered comparable in validity to the Multiple Imputation approach. All tests and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were two-sided. We did not apply any explicit adjustments for multiplicity, rather we interpreted the multiple analyses in a prioritized order. The analyses of the secondary outcomes were performed and interpreted in sequence until one of the analyses failed to show the statistically significant difference (indicative level of statistical significance: 0.05). Results are reported as Least Squares Means with the corresponding Standard Errors derived from the Mixed Models, while difference between groups are reported with 95%CI's.

To assess the adequacy of the linear models describing the observed data—and checking assumptions for the systematic and the random parts of the models—we investigated the model features via the predicted values and the residuals; that is, the residuals had to be normally distributed (around 0) and be independent of the predicted values.

Predefined sensitivity analyses were performed with adjustment for the following baseline variables, age, sex, and self-reported BMI to potentially de-confound for collected characteristics known to be a strong predictor of knee OA that could also potentially cause the exposure (IP cluster).

Analyses were performed in SPSS (version 3.3) and SAS Studio (version 9.4).

3. Results

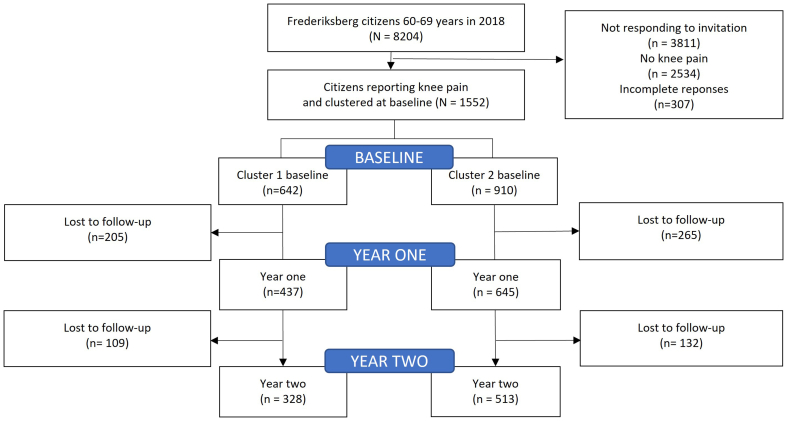

Response rates, dropouts and cluster affiliation presenting the participant flow from the full cohort of Frederiksberg citizens to the clusters used in this study are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The Frederiksberg Cohort study comparing two illness perception phenotypes over time.

Of the 1552 participants with knee pain at baseline, 1082 (69.7%) responded to the questionnaire in year 1, and 841 (54%) in year 2. At year 2, 255 (30.4%) of the respondents reported no knee pain (i.e., applied as a categorical question).

The baseline characteristics as well as the exposure variables are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of clusters (Intention to survey population).

| Cluster 1 “Concerned optimists” (unfavorable profile) (N = 642) |

Cluster 2 “Unconcerned confident” (favorable profile) (N = 910) |

Cluster Difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Demographics | |||

| Women (N, %) | 416 (64.8) | 577 (63.4) | 1.4 (−3.5 to 6.2) |

| Age (years) | 64.5 (2.8) | 64.4 (2.9) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 (5.2) | 26.0 (4.6) | −1.7 (−2.2 to −1.2) |

| KOOS, (0–100) | |||

| KOOS Pain | 65.5 (15.7) | 84.7 (10.4) | 19.3 (17.8–20.6) |

| KOOS Symptoms | 69.4 (17.6) | 85.4 (11.7) | 16.0 (14.5–17.6) |

| KOOS QoL | 47.3 (15.5) | 70.9 (13.9) | 23.6 (22.1–25.1) |

| KOOS ADL | 70.0 (18.2) | 89.4 (10.1) | 19.3 (17.8–20.9) |

| KOOS Sports and Recreation | 37.1 (24.4) | 68.1 (23.1) | 31.0 (28.6–33.4) |

| EQ-5D-3L (−0.624-1.000) | 0.736 (0.126) | 0.857 (0.111) | 0.122 (0.110–0.134) |

| EQ VAS, (0–100) | 69.2 (20.4) | 78.9 (19.9) | 9.6 (7.6–11.7) |

| B-IPQ, (1–10) | |||

| Item 1 Consequences | 5.6 (2.0) | 2.4 (1.1) | −3.2 (−3.4 to −3.0) |

| Item 2 Timeline | 8.8 (1.8) | 6.8 (3.3) | −2 (−2.3 to −1.7) |

| Item 3 Personal control | 5.0 (2.3) | 6.9 (2.6) | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) |

| Item 4 Treatment control | 7.4 (2.4) | 4.7 (2.9) | −2.8 (−3.0 to −2.5) |

| Item 5 Identity | 6.1 (1.6) | 3.1 (1.4) | −3 (−3.2 to −2.9) |

| Item 6 Concern | 6.7 (2.1) | 2.7 (1.4) | −4.1 (−4.4 to −3.9) |

| Item 7 Coherence | 6.8 (2.5) | 7.0 (2.7) | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) |

| Item 8 Emotion | 4.3 (2.5) | 1.7 (1.1) | −2.7 (−2.9 to −2.5) |

Values are means (SD) unless otherwise stated. ∗Statistical significance accepted at p < 0.05. KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, higher scores denote higher functional level. Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ), higher scores on items 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8 denote a more threatening view of the illness, while higher scores on items 3, 4, and 7 denote a less threatening view of the illness. EQ-5D and EQ VAS: EuroQol-5 Domain, higher scores denote better quality of life.

3.1. Primary outcome

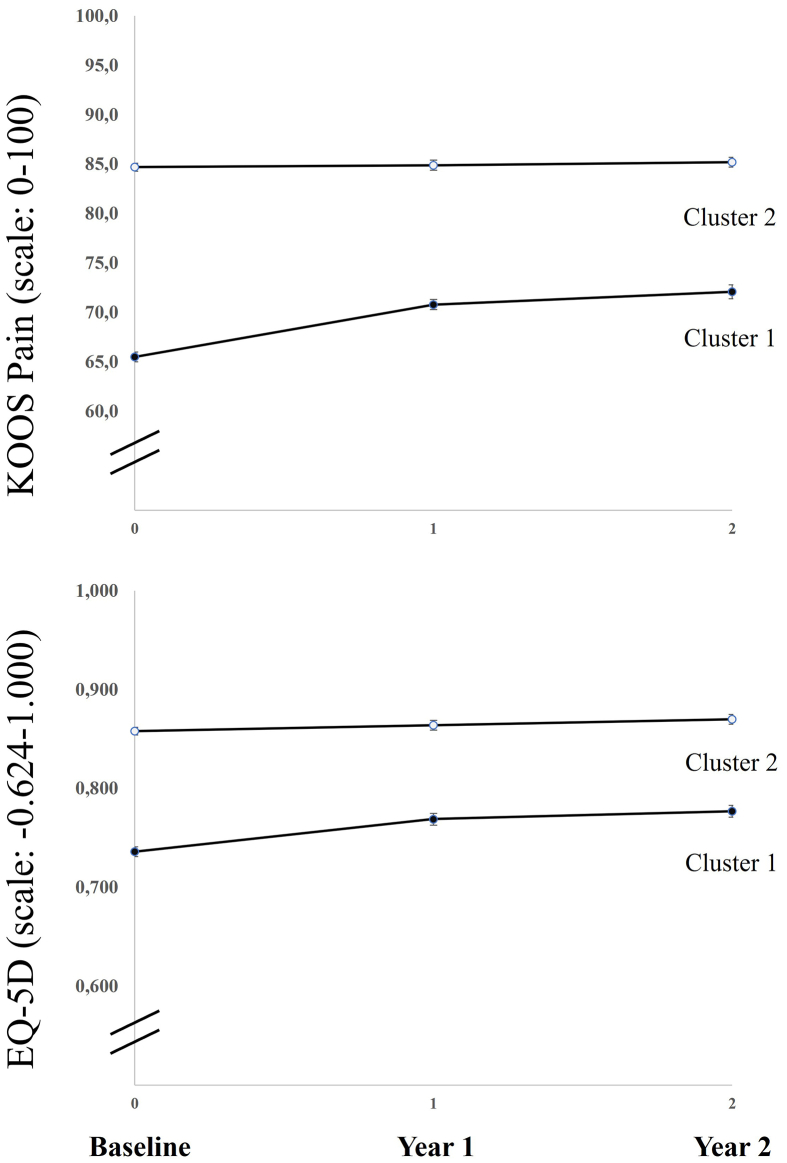

Fig. 2 illustrates the least squares means trajectory for the primary outcome (KOOS Pain) as well as the generic QoL (EQ-5D) measure recorded at baseline and two follow-up times. As presented in Table 2, Cluster 1 reported on average a mean change in KOOS pain of 6.2 (SE 0.6) points after 2 years, indicating that respondents had slightly less knee pain, while Cluster 2 had a mean change of 0.2 points (SE 0.5) points indicating no change over 2 years. There was a statistically significant difference between clusters in the change from baseline −6.0 KOOS pain points (95% CI, −7.3 to −4.7).

Fig. 2.

Trajectories of knee pain and health related quality of life. Measures based on least squares means (SE). KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, higher scores denote higher functional level. EQ-5D (EuroQol-5 Domain), higher scores denote better quality of life.

Table 2.

Cluster mean changes at two years follow-up (based on the intention to survey population).

| Cluster 1 “Concerned optimists” (unfavorable profile) (N = 642) |

Cluster 2 “Unconcerned confident” (favorable profile) (N = 910) |

Cluster Difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| KOOS pain | 6.2 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.5) | −6.0 (−7.3 to −4.7) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| EQ-5D-3L | 0.036 (0.006) | 0.010 (0.005) | −0.026 (−0.038 to −0.013) |

| KOOS Symptom | 4.1 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.6) | −3.3 (−4.7 to −1.9) |

| KOOS ADL | 5.2 (0.6) | −0.4 (0.4) | −5.6 (−6.9 to −4.4) |

| KOOS Sports and Recreation | 7.6 (1.0) | 1.0 (0.8) | −6.7 (−9.0 to −4.3) |

| KOOS QoL | 10.4 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) | −6.3 (−7.9 to −4.7) |

| EQ VAS | −0.7 (1.0) | 1.2 (0.8) | 2.0 (−0.1 to 4.1) |

Values are changes, reported as least squares means (SE) unless otherwise stated. KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, higher scores denote higher functional level. EQ-5D and EQ VAS: EuroQol-5 Domain, higher scores denote better quality of life.

3.2. Secondary outcomes

In both clusters, the mean EQ-5D increased slightly over 2 years (Table 2). There was a statistically significant cluster difference in the change from baseline in EQ-5D of −0.026 points (95% CI, −0.038 to −0.013) while no change was seen in EQ VAS. The changes in the other KOOS subscale scores at the 2-year follow-up indicated minor improvements on average in all subscales in Cluster 1 and no changes in Cluster 2 with statistically significant cluster differences in the changes from baseline (Table 2). The results were apparently robust to the further adjustment for potential confounding variables (collected at baseline: age, sex, and BMI). (Appendix A).

3.3. Changes in the exposure (B-IPQ) over 2 years

Two-year within cluster changes in the B-IPQ scores in Cluster 1 were between 0.1 (SE 0.1) in item 7 “Coherence” and −1.3 (SE 0.1) in item 4 “Treatment Control”. In Cluster 2, changes were between 0.01 (SE 0.1) in item 3 “Personal Control” and 0.5 (SE 0.1) in items 1,5 and 6 (respectively: “Consequences”, “Identity” and “Concern”). These change scores indicated that IPs were relatively stable in the two clusters in the study period. Furthermore, cluster differences were relatively stable in all eight items with respondents in Cluster 1 consequently perceiving their knee pain as a higher threat than cluster 2, except from item 7 “Coherence”, where no difference was seen (Table 3).

Table 3.

B-IPQ Cluster mean changes at two years follow-up up (based on the intention to survey population).

| Cluster 1 “Concerned optimists” (unfavorable profile) (N = 642) |

Cluster 2 “Unconcerned confident” (favorable profile) (N = 910) |

Cluster Difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| B-IPQ [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]] | |||

| Item 1 Consequences | −0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

| Item 2 Timeline | −0.2 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.3–0.9) |

| Item 3 Personal control | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.01 (0.1) | −0.3 (−0.6 to 0.02) |

| Item 4 Treatment control | −1.3 (0.1) | −0.2 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.8–1.5) |

| Item 5 Identity | −0.7 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| Item 6 Concern | −1.1 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 1.6 (1.4–1.9) |

| Item 7 Coherence | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.4) |

| Item 8 Emotion | −0.7 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

Values are changes, least squares means (SE) Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ), higher scores on items 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8 denote a more threatening view of the illness, while higher scores on items 3, 4, and 7 denote a less threatening view of the illness.

3.4. Differences between respondents and non-respondents

Baseline differences between study participants who were still part of the cohort at year 2 “respondents” (N = 841) and participants who dropped out of the study after baseline “Non-respondents” (N = 711) are described in Appendix B. No clinically relevant differences were seen in neither demographics nor in illness perception, functional level or QoL. Hence, respondents and non-respondents were similar at baseline.

4. Discussion

In this 2-year follow-up on 2 clusters of elderly community dwelling individuals with knee pain and different baseline perceptions of their pain, we found small and clinically irrelevant cluster differences in the changes in knee pain over 2 years. Similar small and clinically irrelevant cluster differences were found in the 2-year changes in our secondary outcomes. Finally, small and clinically irrelevant cluster changes were seen in the B-IPQ scores.

This is in contrast to our hypothesis that IP is predictive of symptomatic progression, and rather suggests that IP may be less important to patients with knee pain than to patients with other diseases, in which IP have been shown predictive of symptom progression [37].

Cluster 1 had a small and clinically irrelevant [27] improvement in knee pain and QoL while Cluster 2 neither changed in knee pain nor in QoL. This altogether suggests that the small changes over time may be attributable to the regression to the mean phenomenon (Fig. 2). Regression to the mean is described as a phenomenon that makes natural variation in repeated data look like an actual change [38].

Within the musculoskeletal field, several cross-sectional studies have explored the relationship between IP, pain, QoL and functional level and generally found positive illness perceptions to be related to a better QoL, less pain and higher functional level [39,40], but only a few prospective studies have explored IP as a predictive factor of these measures and results are conflicting.

Two studies confirm our results: A study by de Raaij et al. [41] assessing the effect of physiotherapy on 251 patients with musculoskeletal pain found limited predictive value of baseline IP on pain and functional level and another similar study by Hallegraeff et al. [42], on 204 patients with acute nonspecific low back pain found similar results.

Meanwhile, in 2018 a systematic review based on 22 cross-sectional studies and four longitudinal studies of patients with non-cancer related musculoskeletal pain [43] found that maladaptive IP implied stronger pain intensity and more limitation in physical function but the longitudinal relationship between IP and pain progression was unclear. Another systematic review by Rivera et al. [44], including eight cross-sectional studies and four longitudinal studies, using cluster analysis on different chronic conditions (including three studies on musculoskeletal pain), found that more favorable perceptions were related to better outcome and predictable of these over time.

In 241 patients with OA at multiple sites (hand, knee, hip or spine), Bijsterboch et al. [45] found that less perceived personal illness control (item 3), and more perceived consequences of OA (item 1) at baseline were predictive of high disability after 6 years Another cohort study by Van der Oest, including 219 patients with carpometacarpal OA treated with either orthosis and/or hand therapy [37], found that positive outcome expectations on the B-IPQ (treatment control item) and illness coherence (item 7) at baseline were associated with less pain and better functional level over 3 months.

These results differ from our findings where an unfavorable IP did not seem to predict negative outcome at follow-up. There are several possible explanations for this. First, it should be noted that IP was measured using different measures in the abovementioned studies with Rivera et al. using the Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire [46] while most of the other studies used the B-IPQ like we did. Also, the included populations differ as they represent both different musculoskeletal disorders and different medical disorders. Furthermore, Van der Oest [37] aimed to predict response to a treatment over 3 months, whereas we aimed to assess the natural progression of knee pain over 2 years. In contrast, Bijsterboch et al. [45] applied a 6-year follow-up and it is possible that a longer time span is necessary to show the impact of baseline illness perceptions on symptomatic progression also in our pre-OA cohort. The abovementioned studies suggest that illness perceptions likely differ between diagnoses but also within severity of conditions (e.g., established OA vs pre-OA). As an example, patients with radiographically verified OA may perceive the concept of chronicity differently than people with pain without a formal diagnosis. In line with this, cultural differences, have been shown to impact on how we understand questions concerning IP. Hence, the B-IPQ items 1 “Consequences” concerning the impact the disease has on your life and item 5 “Identity” concerning perceived symptoms attributed to the disease, have been found to be perceived as the same item in some populations but not in others [47]. Likewise, sex and type of diagnosis and may impact on the understanding of patient reported outcome measures. Hence, in a validation of the Danish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire–Revised, women were found to perceive a question concerning the ability to wash and comb their hair differently than men [48]. And patients with fibromyalgia have been found to report their symptoms in a way that may be interpreted as this population having a higher degree of depression than what is actually the case [49].

Some strengths and limitations to our study should be noted; First and foremost, the longitudinal design and the relatively large sample size allows for stronger conclusions concerning causality. Furthermore, we focused on perceptions related to only the knee joint whereas many other studies have used populations with OA in different sites. Limitations include the limited knowledge on other comorbidities in this cohort, although these may have influenced on both illness perception, pain and QoL, thus confounding our results. We also only asked about knee pain within last month, thus, people with intermittent pain episodes may have been misclassified as not having knee pain. Furthermore, there was a relatively large dropout (46%) from baseline to follow-up and we were not able to offer any compensation to augment the response rate. Also, some respondents (16%) reported knee pain at baseline but not at 2-year follow-up and had their KOOS data imputed. We realize that the imputed scores may be imprecise but, given that the scores have been validated on a relatively large patient population similar to ours [36], we believe that they are representative for our cohort as well, and that posing questions concerning knee pain related functional limitations to participants not reporting knee pain would likely also result in imprecise and invalid data. We chose not to impute data from participants who had dropped out of the cohort. This may have biased the presented data, but an imputation assigning arbitrary values to 46% of the data would likely result in overcorrection. As there were no clinically relevant baseline differences between respondents and non-respondents (Appendix B), the results based on the responders are considered representative for the whole cohort. Finally, we acknowledge that perceptions may change and that a cluster analysis at year one or two could have identified different IP traits.

5. Conclusion

In a cohort of pre-OA elderly Danes with knee pain we found minimal changes in knee pain and QoL over 2 years. IP was not prognostic of these changes which implies that targeting IP may not be relevant in this patient population.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Elisabeth Ginnerup-Nielsen, Marius Henriksen and Henning Bliddal. Analyses were performed by Elisabeth Ginnerup-Nielsen, Marius Henriksen and Robin Christensen. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Elisabeth Ginnerup-Nielsen and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and material

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to Danish legislations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

The Frederiksberg Cohort study was reviewed by the health research ethics committee who deemed the study exempt from approval (j.no. 17024697) as it is only based on questionnaires. Such studies can be implemented without permission from the Health Research Ethics Committee according to Danish legislation (Committee Act § 1, paragraph 1). All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

All participants consented to participate by responding to the survey.

Funding

This specific study received no funding, but the Frederiksberg Cohort is supported by grants from Ellen Mørch (grant number: 324962019) and Minister Erna Hamiltons Legat for Videnskab og Kunst (grant number: 013-2021). The Parker Institute is supported by a core grant from the OAK Foundation (OCAY-18-774-OFIL).

Conflict of interest

All authors have completed the Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Open authors’ disclosure form and declare that they have no competing interests to report.

Handling Editor: Professor H Madry

Appendix A. Cluster mean values for the change from baseline at two years follow-up adjusted for sex, age and BMI

| Cluster 1 “Concerned optimists” (unfavorable profile) (N = 642) |

Cluster 2 “Unconcerned confident” (favorable profile) (N = 910) |

Difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| KOOS pain (0–100) | 6.3 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.5) | −6.0 (−7.4 to −4.7) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| EQ-5D-3L (−0.624-1.000) | 0.036 (0.006) | 0.010 (0.005) | −0.026 (−0.038 to −0.014) |

| KOOS Symptom | 4.0 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.5) | −3.1 (−4.5 to −1.7) |

| KOOS ADL | 5.2 (0.6) | −0.4 (0.5) | −5.6 (−6.9 to −4.4) |

| KOOS Sports and Recreation | 7.7 (1.0) | 0.9 (0.8) | −6.7 (−9.0 to −4.3) |

| KOOS QoL | 10.4 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) | −6.4 (−8.1 to −4.8) |

| EQ VAS (0–100) | −1.0 (1.0) | 1.3 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.1–4.4) |

Values are changes, least squares means (SE) unless otherwise stated. KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, higher scores denote higher functional level. EQ-5D and EQ VAS: EuroQol-5 Domain, higher scores denote better quality of life.

Appendix B. . Baseline differences between respondents and non-respondents in year 2

| Respondents |

Non-respondents |

Difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 841) |

(N = 711) |

||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | (mean, 95% CI) | |

| Cluster 1, n (%) | 328 (39.0%) | 314 (44.2%) | 5.3 (0.2–10.3) |

| Cluster 2, n (%) | 513 (60.9%) | 397 (55.8%) | −5.3 (−10.3 to −0.2) |

| Demographics | |||

| Women (N, %) | 532 (63.3%) | 461 (64.8%) | 1.6 (−3.2 to 6.4) |

| Age | 64.5 (2.8) | 64.4 (2.8) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2), | 26.5 (4.9) | 26.7 (4.9) | 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.7) |

| KOOS (0–100) | |||

| KOOS Pain | 77.9 (15.1) | 75.5 (16.8) | −2.4 (−4.0 to −0.8) |

| KOOS Symptoms | 79.5 (15.8) | 78.0 (17.1) | −1.5 (−3.2 to 0.1) |

| KOOS ADL | 83.1 (15.4) | 79.4 (18.5) | −3.7 (−5.4 to −2.0) |

| KOOS Sports and Recreation | 56.6 (28.0) | 53.8 (28.1) | −2.8 (−5.6 to 0.0) |

| KOOS QoL | 63.4 (17.2) | 61.1 (17.4) | −2.3 (−4.0 to −0.6) |

| EQ-5D | |||

| EQ-5D-3L, (−0.624-1.000) | 0.818 (0.117) | 0.795 (0.146) | −0.024 (−0.037 to −0.010) |

| EQ VAS, (0–100) | 75.2 (21.4) | 74.5 (19.7) | −0.8 (−2.8 to 1.3) |

| B-IPQ, (1–10) | |||

| Item 1 Consequences | 3.5 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.3) | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) |

| Item 2 Timeline | 7.7 (3.0) | 7.5 (3.0) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) |

| Item 3 Personal control | 6.3 (2.6) | 5.9 (2.6) | −0.5 (−0.7 to −0.2) |

| Item 4 Treatment control | 5.7 (3.0) | 5.9 (3.0) | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) |

| Item 5 Identity | 4.2 (2.1) | 4.4 (2.1) | 0.2 (−0.0 to 0.4) |

| Item 6 Concern | 4.2 (2.6) | 4.7 (2.8) | 0.5 (0.2–0.7) |

| Item 7 Coherence | 7.0 (2.6) | 6.8 (2.7) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) |

| Item 8 Emotion | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.9 (2.4) | 0.3 (0.0–0.5) |

Values are least squares means (SE) unless otherwise stated. KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, higher scores denote higher functional level. Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ), higher scores on items 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8 denote a more threatening view of the illness, while higher scores on items 3, 4, and 7 denote a less threatening view of the illness. EQ-5D and EQ VAS: EuroQol-5 Domain, higher scores denote better quality of life.

References

- 1.Liu S., Wang B., Fan S., Wang Y., Zhan Y., Ye D. Global burden of musculoskeletal disorders and attributable factors in 204 countries and territories: a secondary analysis of the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos T., Abajobir A.A., Abate K.H., Abbafati C., Abbas K.M., Abd-Allah F., et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui A., Li H., Wang D., Zhong J., Chen Y., Lu H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pisters M., Veenhof C., Van Dijk G., Heymans M., Twisk J., Dekker J. The course of limitations in activities over 5 years in patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis with moderate functional limitations: risk factors for future functional decline. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(6):503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitaloni M., Botto-van Bemden A., Sciortino Contreras R.M., Scotton D., Bibas M., Quintero M., et al. Global management of patients with knee osteoarthritis begins with quality of life assessment: a systematic review. BMC Muscoskel. Disord. 2019;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2895-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.OARSI . 2016. Osteoarthritis, A Serious Disease; pp. 1–102.https://oarsi.org/sites/default/files/docs/2016/oarsi_white_paper_oa_serious_disease_121416_1.pdf [cited 2021 July 02]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bannuru R.R., Osani M., Vaysbrot E., Arden N., Bennell K., Bierma-Zeinstra S., et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1578–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berenbaum F., Walker C. Osteoarthritis and inflammation: a serious disease with overlapping phenotypic patterns. PGM (Postgrad. Med.) 2020;132(4):377–384. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1730669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins J.E., Katz J.N., Dervan E.E., Losina E. Trajectories and risk profiles of pain in persons with radiographic, symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(5):622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deveza L.A., Nelson A.E., Loeser R.F. Phenotypes of osteoarthritis-current state and future implications. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019;37(Suppl 120):64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kittelson A.J., Stevens-Lapsley J.E., Schmiege S.J. Determination of pain phenotypes in knee osteoarthritis: a latent class analysis using data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(5):612–620. doi: 10.1002/acr.22734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knoop J., van der Leeden M., Thorstensson C.A., Roorda L.D., Lems W.F., Knol D.L., et al. Identification of phenotypes with different clinical outcomes in knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(11):1535–1542. doi: 10.1002/acr.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Esch M., Knoop J., Van der Leeden M., Roorda L., Lems W., Knol D., et al. Clinical phenotypes in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a study in the Amsterdam osteoarthritis cohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(4):544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bijlsma J.W., Berenbaum F., Lafeber F.P. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2115–2126. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah K., Arden N., Silman A., Furniss D., Collins G. Development and validation of a prediction model for incident radiographic finger interphalangeal joint osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021;29:S73. [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Helvoort E.M., van Spil W.E., Jansen M.P., Welsing P.M., Kloppenburg M., Loef M., et al. Cohort profile: the Applied Public-Private Research enabling OsteoArthritis Clinical Headway (IMI-APPROACH) study: a 2-year, European, cohort study to describe, validate and predict phenotypes of osteoarthritis using clinical, imaging and biochemical markers. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinman J., Petrie K.J., Moss-Morris R., Horne R. The illness perception questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol. Health. 1996;11(3):431–445. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damman W., Liu R., Kaptein A.A., Evers A.W., van Middendorp H., Rosendaal F.R., et al. Illness perceptions and their association with 2 year functional status and change in patients with hand osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2018;57(12):2190–2199. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindberg M.F., Miaskowski C., RustøEn T., Rosseland L.A., Cooper B.A., Lerdal A. Factors that can predict pain with walking, 12 months after total knee arthroplasty: a trajectory analysis of 202 patients. Acta Orthop. 2016;87(6):600–606. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2016.1237440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster N.E., Bishop A., Thomas E., Main C., Horne R., Weinman J., et al. vol. 136. 2008. Illness Perceptions of Low Back Pain Patients in Primary Care: What Are They, Do They Change and Are They Associated with Outcome? Pain; pp. 177–187. 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaptein A.A., Bijsterbosch J., Scharloo M., Hampson S.E., Kroon H.M., Kloppenburg M. Using the common sense model of illness perceptions to examine osteoarthritis change: a 6-year longitudinal study. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):56. doi: 10.1037/a0017787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginnerup-Nielsen E., Christensen R., Heitmann B.L., Altman R.D., March L., Woolf A., et al. Estimating the prevalence of knee pain and the association between illness perception profiles and self-management strategies in the Frederiksberg cohort of elderly individuals with knee pain: a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10(4):668. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ginnerup-Nielsen E.M., Henriksen M., Christensen R., Heitmann B.L., Altman R., March L., et al. Prevalence of self-reported knee symptoms and management strategies among elderly individuals from Frederiksberg municipality: protocol for a prospective and pragmatic Danish cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., Elliott V., Fernandez M., O'Neal L., et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inf. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broadbent E., Petrie K.J., Main J., Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006;60(6):631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roos E.M., Toksvig-Larsen S. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual. Life Outcome. 2003;1(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wittrup-Jensen K.U., Lauridsen J., Gudex C., Pedersen K.M. Generation of a Danish TTO value set for EQ-5D health states. Scand. J. Publ. Health. 2009;37(5):459–466. doi: 10.1177/1403494809105287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Group T.E. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Pol. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins N., Prinsen C., Christensen R., Bartels E., Terwee C., Roos E. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): systematic review and meta-analysis of measurement properties. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(8):1317–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monticone M., Ferrante S., Salvaderi S., Motta L., Cerri C. Responsiveness and minimal important changes for the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score in subjects undergoing rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013;92(10):864–870. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31829f19d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roos E.M., Lohmander L.S. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual. Life Outcome. 2003;1(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva M.D.C., Perriman D.M., Fearon A.M., Couldrick J.M., Scarvell J.M. Minimal important change and difference for knee osteoarthritis outcome measurement tools after non-surgical interventions: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2023;13(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauritsen J. 2007. Danske normtal for Euroqol-5d; pp. 1–2.http://uag.dk/simpelfunktion/pdf/eq5dknorm.pdf [cited 2020 09-21]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 35.EuroQol-Group EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Pol. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marot V., Murgier J., Carrozzo A., Reina N., Monaco E., Chiron P., et al. Determination of normal KOOS and WOMAC values in a healthy population. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2019;27(2):541–548. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Oest M.J., Hoogendam L., Wouters R.M., Vermeulen G.M., Slijper H.P., Selles R.W., et al. Associations between positive treatment outcome expectations, illness understanding, and outcomes: a cohort study on non-operative treatment of first carpometacarpal osteoarthritis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1936661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnett A.G., Van Der Pols J.C., Dobson A.J. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005;34(1):215–220. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hyphantis T., Kotsis K., Tsifetaki N., Creed F., Drosos A.A., Carvalho A.F., et al. The relationship between depressive symptoms, illness perceptions and quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis in comparison to rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013;32(5):635–644. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ünal Ö., Akyol Y., Tander B., Ulus Y., Terzi Y., Kuru Ö. The relationship of illness perceptions with demographic features, pain severity, functional capacity, disability, depression, and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain. Turkish J. Phys. Med. Rehab. 2019;65(4):301. doi: 10.5606/tftrd.2019.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Raaij E., Wittink H., Maissan J., Westers P., Ostelo R. Limited predictive value of illness perceptions for short-term poor recovery in musculoskeletal pain. A multi-center longitudinal study. BMC Muscoskel. Disord. 2021;22(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04366-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hallegraeff J.M., van Trijffel E., Kan R.W., Stenneberg M.S., Reneman M.F. Illness perceptions as an independent predictor of chronic low back pain and pain-related disability: a prospective cohort study. Physiotherapy. 2021;112:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Raaij E.J., Ostelo R.W., Maissan F., Mollema J., Wittink H. The association of illness perception and prognosis for pain and physical function in patients with noncancer musculoskeletal pain: a systematic literature review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018;48(10):789–800. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.8072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivera E., Corte C., DeVon H.A., Collins E.G., Steffen A. A systematic review of illness representation clusters in chronic conditions. Res. Nurs. Health. 2020;43(3):241–254. doi: 10.1002/nur.22013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bijsterbosch J., Scharloo M., Visser A., Watt I., Meulenbelt I., Huizinga T., et al. Illness perceptions in patients with osteoarthritis: change over time and association with disability. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61(8):1054–1061. doi: 10.1002/art.24674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moss-Morris R., Weinman J., Petrie K., Horne R., Cameron L., Buick D. The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychol. Health. 2002;17(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rüdell K., Bhui K., Priebe S. Concept, development and application of a new mixed method assessment of cultural variations in illness perceptions: barts Explanatory Model Inventory. J. Health Psychol. 2009;14(2):336–347. doi: 10.1177/1359105308100218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duhn P., Amris K., Bliddal H., Wæhrens E. The validity of the Danish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire–Revised applied in a clinical setting: a Rasch analysis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1080/03009742.2022.2098631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amris K., Omerovic E., Danneskiold-Samsøe B., Bliddal H., Waehrens E. The validity of self-rating depression scales in patients with chronic widespread pain: a Rasch analysis of the Major Depression Inventory. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2016;45(3):236–246. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2015.1067712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to Danish legislations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.