Summary

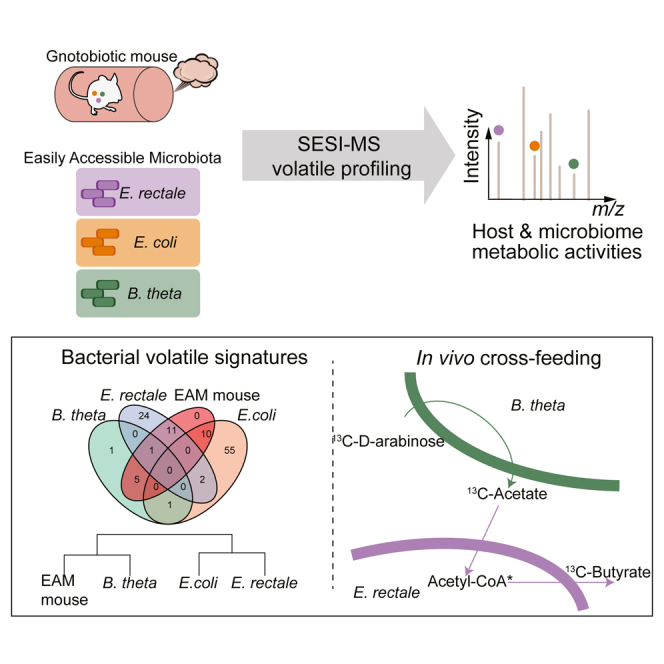

The metabolic “handshake” between the microbiota and its mammalian host is a complex, dynamic process with major influences on health. Dissecting the interaction between microbial species and metabolites found in host tissues has been a challenge due to the requirement for invasive sampling. Here, we demonstrate that secondary electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (SESI-MS) can be used to non-invasively monitor metabolic activity of the intestinal microbiome of a live, awake mouse. By comparing the headspace metabolome of individual gut bacterial culture with the “volatilome” (metabolites released to the atmosphere) of gnotobiotic mice, we demonstrate that the volatilome is characteristic of the dominant colonizing bacteria. Combining SESI-MS with feeding heavy-isotope-labeled microbiota-accessible sugars reveals the presence of microbial cross-feeding within the animal intestine. The microbiota is, therefore, a major contributor to the volatilome of a living animal, and it is possible to capture inter-species interaction within the gut microbiota using volatilome monitoring.

Keywords: secondary electrospray ionization, volatile metabolites, metabolomics, gut microbiota, isotopic labeling

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Non-invasive monitoring of the murine and gut microbiota metabolism in a living animal

-

•

Volatilome of gnotobiotic mice includes signatures of the dominant colonizing bacteria

-

•

Combining SESI-MS and isotope tracing allows tracking of in vivo microbial cross-feeding

-

•

Microbiota is a major contributor to the mouse volatilome

Motivation

Understanding the interaction between microbial species/strains and host metabolism relies heavily on discrete sampling of body fluids and organs, which is invasive, requires a large number of animals, and has a very limited time resolution. The method presented here addresses this problem via non-invasive monitoring of the volatilome of a living animal. Using gnotobiotic mice, we could validate the link between the whole-animal volatilome and the volatilome of individual gut bacteria and could demonstrate the ability to combine volatilome analysis with heavy-isotope-labeled sugars to observe cross-feeding in the gut microbiota.

Lan, Greter, et al. present proof of concept that a SESI-MS-based workflow can non-invasively monitor both host and gut microbiota metabolism in mice. This can be combined with isotope tracing to infer microbial cross-feeding in the intestine of a living animal.

Introduction

The gastrointestinal tract is colonized by a complex ecosystem of microbes, referred to as the gut microbiota, which plays a major role in modulating host metabolism and immune function.1 Exchange of metabolites between the microbes and their host is an integral mechanism in this interaction.2,3 Correspondingly, our ability to measure the production of small molecules produced by a host and its microbiota has the potential to advance our understanding of this highly complex relationship.4,5 Studies on plasma have shown microbiota-dependent effects on a variety of host metabolites, including on amino acids,3,6 fatty acids,7,8 lipids, bile acids,9 and xenobiotics.10 When conventionally colonized mice are compared with germ-free (GF) mice, 10% of identified features in common between these mice differ in signal intensity.11 Furthermore, it was previously suggested that plasma metabolites in the host are predictive of human gut microbiota diversity, and metabolites in the host can be used as predictors of microbial phyla abundance.12

To date, most metabolomics studies have focused on quantification of metabolites in body fluids, often requiring invasive sampling. Moreover, the easily accessible fecal metabolites are often used as a proxy for microbial metabolism that is most active in the upper large intestine. Acquiring meaningful, time-resolved data on microbial activity in live animals is thus challenging. However, this can be done by monitoring small-molecule metabolites released by the experimental animals to the gas phase, including volatile, semi-volatile, and low-volatility species (hereafter, for simplicity, referred to as the “volatilome”).

Time-resolved monitoring of host metabolism is possible using sensors measuring light gases released by the organism (e.g., H2, CH4, O2, and CO27,13,14,15). These data allow monitoring of some aspects of host and microbiota metabolism, such as host energy expenditure, respiratory quotient, and microbial hydrogen production. However, due to the limited available sensors, only a small number of simple gases or volatiles can currently be studied using these methods.

Ambient mass spectrometry (MS) methods are ionization methods that operate under ambient conditions and require minimal sample preparation.16 Progress in ambient MS now renders it possible to non-invasively monitor the volatilome in breath17,18,19 and exhaust gases.20,21 Notably, this includes the ability to detect short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are of known interest in host-microbe interactions. SCFAs have already been extensively studied, for example in epithelial gene expression and metabolism.22 This suggested the possibility to apply ambient MS technology to the study of microbiome function.

Secondary electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (SESI-MS), which has been developed in the past decades,23 is compatible with high-resolution MS and has a relatively fast response and broad detection range24,25 when compared with conventional MS-based detection methods for volatiles. For example, SESI-MS allows direct detection without pre-concentration and separation (compared with GC-MS,26 which requires pre-concentration and separation), it can detect volatiles ionized in both positive and negative modes (compared with proton-transfer reaction MS,27 which only allows positive ion mode), and it can be easily mounted on a high-resolution MS (compared with selected-ion flow-tube MS,28 which only provides unit mass resolution). SESI-MS allows detection of molecules in the gas phase down to sub-ppt concentrations with minimum detectable vapor pressure down to 10−7 bar.29,30 It is therefore the method of choice for efficient, real-time detection of volatile metabolites in biological systems. Previously, SESI-MS has been used for identifying biomarkers for various lung pathogens in human breath31 and to capture the metabolic responses of Staphylococcus aureus to antibiotic treatment in the headspace of microbial batch cultures.32 However, due to the high complexity of the gut microbial community, it is usually difficult to assign metabolic signals to a specific origin and to decipher causal relations between changes in bacterial and host metabolism; thus, the application of SESI-MS in gut microbiota research is yet to be explored.

Here, we present a SESI-MS-based approach to simultaneously study microbiome and host metabolism by monitoring volatilome released from live animals, in which we can manipulate the microbial composition: ranging from GF via a simplified 3-species microbiota to a complete “specific-pathogen-free” (SPF) microbiota. By first identifying volatile markers for each member of the reduced microbiota, we were able to track bacterial metabolism inside a host non-invasively while at the same time monitoring the changes in host metabolism. Feeding of microbiota-available heavy-isotope-labeled sugars allowed us to unambiguously identify the microbial origin of volatilome and to directly observe microbial cross-feeding in live animals. Applying this approach to living animals expanded our ability to understand the host-microbiota interaction and could potentially enable us to study the interaction in a continuous way.

Results

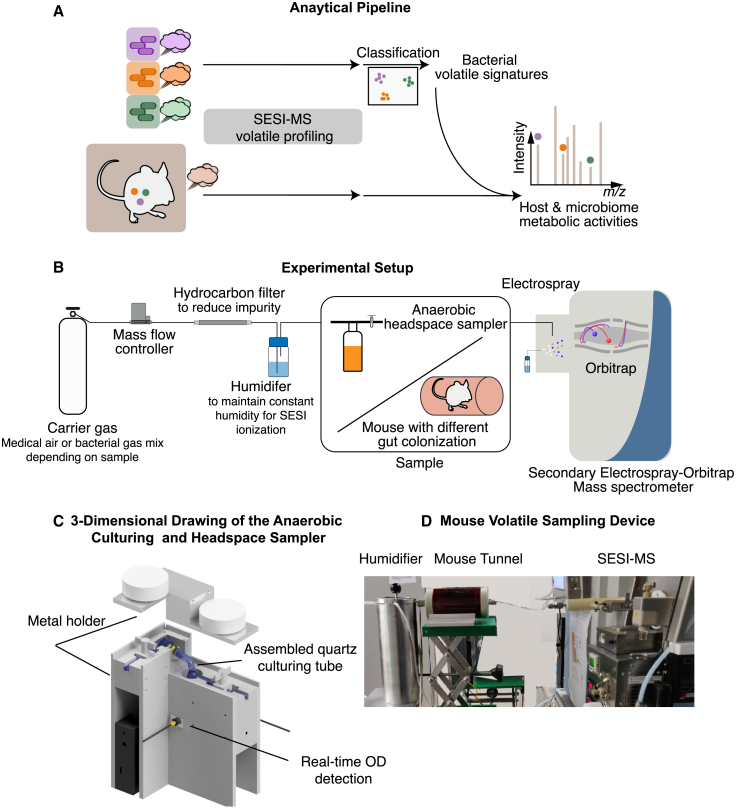

A setup to identify small-molecule metabolites in gas released by animals and their microbes

In laboratory animal science, it is established that repeated handling of experimental animals can lead to behavioral and metabolic changes in the animals.33,34 This is typically referred to as “stress,” and it becomes more problematic with increasing invasiveness of the interventions (e.g., blood sampling). We therefore developed a SESI-MS-based approach to measure the volatilome released to the local atmosphere by unperturbed animals and their microbiota (Figure 1A). To measure the volatilome of the murine host alone, GF mice were allowed to enter a red plastic tunnel (7 cm diameter, 11 cm length) fed with sterile humidified medical air, which was directly connected to the SESI-MS inlet for measurements (Figures 1B and 1D). Note that mice cannot see red light, so this tunnel is perceived as a safe, dark space while allowing visual inspection by the investigators. In order to benchmark the system for microbial metabolite analysis and to identify metabolites characteristic for particular bacterial species, we also established a custom-made headspace sampling system coupled to the SESI-MS (headspace-SESI; Figures 1B and 1C), which makes it possible to identify metabolic signatures of microbial cultures. By combining the volatilome of GF mice and the headspace volatilome of individual cultures, we identified markers for the different parts of the host-microbiota system, i.e., metabolic signatures for different microbiota members and a baseline metabolic profile of the uncolonized host. In a next step, by measuring the volatilome of colonized mice, we can infer the effect of metabolic interactions between the host and its microbiota.

Figure 1.

Workflow and experimental settings for non-invasive monitoring of microbiome and host metabolism

(A) Schematic workflow for non-invasive monitoring of host-microbiome metabolism.

(B) Experimental setups for SESI-MS measurement of either bacterial cultures or mice.

(C) Three-dimensional drawing of the anaerobic culturing and headspace sampler. The sampler consists of a set of glass containers (1.5 cm outer diameter quartz cylinder flask with gas valve on both inlet and outlet), a home-built optical density meter, and a metal holder kept at 37°C. For details, see the figure and design files in Data S1.

(D) Picture of experimental setup for measuring mouse volatiles. The mouse was kept in an air-tight red plastic tunnel in order to reduce its stress level. Humidified medical air at a flow rate of 0.3 L/min constantly flows through the tunnel and transfers the released volatiles into SESI-MS.

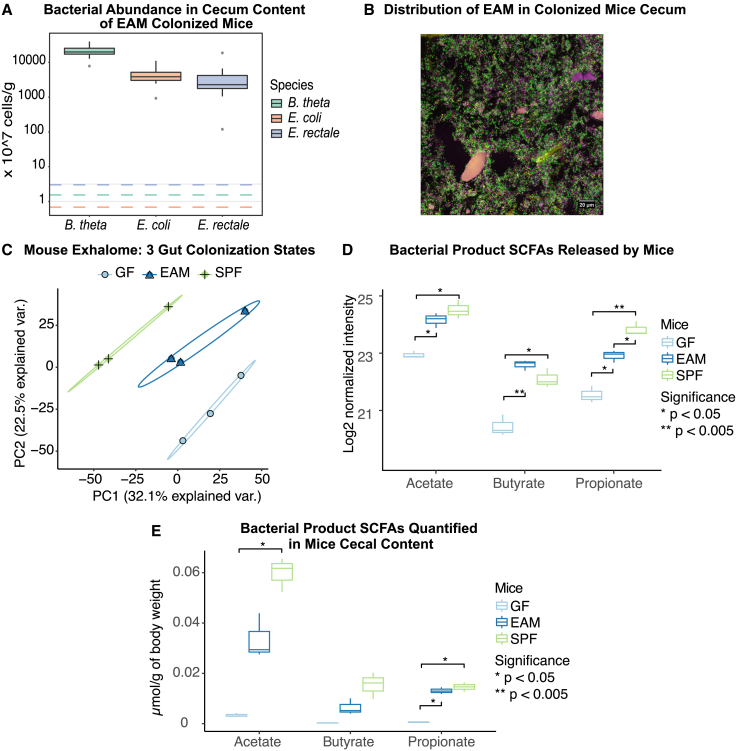

Distinction of different colonization states based on the volatilome

As a first proof of principle, we tested whether it is possible to distinguish different colonization states of mice using our SESI-MS setup. We measured the volatilome of C57BL/6 mice that were either GF or colonized with two different microbiota. The simpler microbiota (easily accessible microbiota [EAM]) consists of three bacterial strains, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Escherichia coli, and Eubacterium rectale. These are common members of the typical human gut microbiota, representing the three most abundant bacterial phyla. The three microbes colonize the mouse large intestine to a density of between 109 and 1011 bacteria per gram of gut content (Figures 2A and 2B). To represent a more complex microbiota, we used conventional SPF mice raised in the EPIC mouse facility at ETH Zurich (see Figure S2B for taxonomic composition of the SPF mice used). Using the SESI-MS setup depicted in Figure 1D, we measured the volatilome released by these three different groups of mice; each animal was measured five times for 100 s (in total around 8 min). The obtained raw mass spectra were first converted to intensity matrices (in each scan, the intensity of each feature was calculated, and a total of 33,565 features were detected). Features detected in less than 50% of mouse samples were discarded (leaving 15,365 features). Then, signal-to-noise (S/N; signal detected in empty mouse tubes served as noise) ratios were calculated, and only features with an S/N ratio >4 were kept. In total, 2,879 features passed these quality control filters and were used to make the principal-component analysis (PCA) plot (Data S2). Regarding reproducibility, a median coefficient of variation of 2.39% was calculated for all features detected in five replicate measurements (i.e., five times for 100 s measurement in SESI-MS) for each animal. It was possible to clearly distinguish the three different colonization states using PCA based on the detected metabolite pool (Figure 2A). We then looked for bacterial signatures in the data, focusing initially on the SCFAs acetate, propionate, and butyrate. We chose these three SCFAs based on prior knowledge of bacterial metabolism in the intestinal tract of mammals: SCFAs are the main end products of microbial metabolism in the gut. They are produced in large quantities by the gut microbiota35,36,37 and are known to be correlated with microbial activity.38,39 As expected, we saw increased levels of all three SCFAs in colonized mice compared with GF mice, with butyrate detected at higher levels in the 3-species microbiota-colonized mice, whereas acetate and propionate were higher in the SPF microbiota (Figure 2D). We confirmed these results using a targeted liquid chromatography (LC)-MS approach (Figure 2E). It has been reported before that simplified gut microbiota models can produce equal amounts of SCFAs as SPF mice but always higher amounts than in GFs.40 By comparing the SCFA concentrations in the volatilome of SPF and GF mice, our data suggest that 66.4% of the acetate signal, 34.5% of the butyrate signal, and 79.5% of the propionate signal are microbiota dependent. The remaining SCFA signals present in GF animals could be attributed to the SCFAs in mouse diet,41 which could be taken up into the bloodstream or contribute to the baseline SCFA levels in the mice cages.

Figure 2.

Different gut colonization can be detected in emitted metabolites of the host

(A) Bacterial abundance in cecum content of EAM-colonized mice (N = 14), quantified using qPCR. Dotted lines indicate the detection limits.

(B) Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) imaging of EAM-colonized mice gut showing the distribution of EAM in colonized mice cecum.

(C) PCA plot of the volatilome of mice in different colonization states: germ free (GF), EAM colonized (EAM), and SPF (N = 3 per group).

(D) Levels of typical bacterial fermentation products, SCFAs, released by differently colonized mice (N = 3 per group, Student’s t test with Bonferroni adjusted p).

(E) Total SCFAs generated in cecum content normalized to the mice body weight of differently colonized mice (N = 3 per group, Student’s t test with Bonferroni adjusted p). For SCFA concentrations in cecum content, see Figure S2C.

Disentangling host and microbiota signals in a minimal microbiota

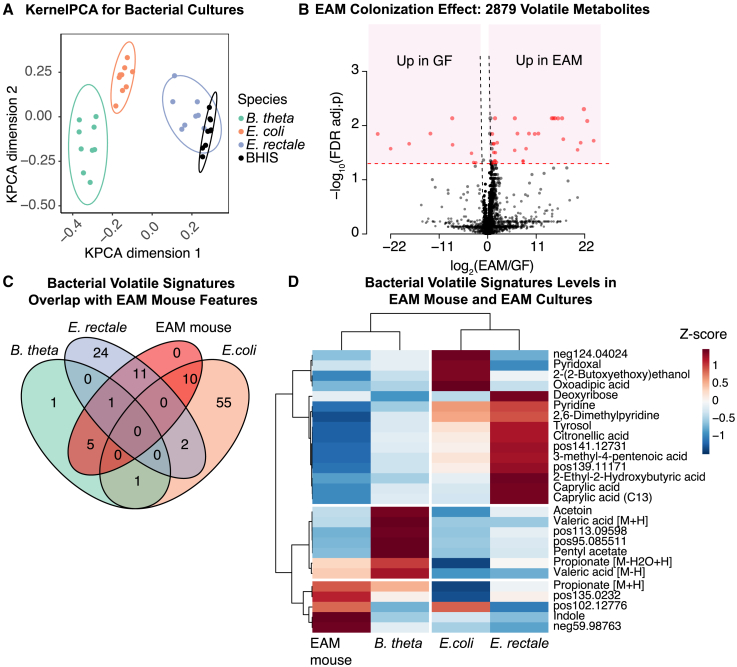

After establishing that our experimental setup can distinguish between different colonization states and can identify signature microbial metabolites in the volatilome around a live, unperturbed mouse, we next aimed to delineate the contribution of the different parts of the host-microbiota system. For this, we used the more tractable 3-member microbiota (EAM), as this allowed us to compare the pure-culture metabolome to the colonized mice. The headspace-SESI-MS system was used to profile the volatilome released by pure cultures of the different strains or sterile culture medium (nine replicates per strain/medium). The obtained raw mass spectra were first converted to intensity matrices (in each scan, the intensity of each feature was calculated, and a total of 47,089 features were detected) (Data S2). Features detected in more than 70% of samples (559 features) were kept for generating the kernel PCA plot (Figure 3A). Headspace-SESI-MS metabolome profiles of the same strains during stationary growth clearly clustered together, as did the anaerobic culture medium alone, allowing separation of the strains/media from each other (Figure 3A). As gut bacteria are typically growth limited by nutrient availability, late-log/early-stationary phase is a reasonable approximation of the majority of cells.42

Figure 3.

Tracking of bacterial volatile signatures detected in vitro in EAM-colonized mice

(A) Kernel PCA plot of the in vitro EAM species and the brain heart infusion (BHIS) culture media (N = 9 per group).

(B) Volcano plot comparing volatilome of GF mice and EAM mice (N = 3 per group) (41 FDR adjusted [adj.] p < 0.05 and fold change > 2).

(C) Overlaps between bacterial volatile signatures identified in vitro and EAM mouse volatile features.

(D) Hierarchical clustering showing normalized intensities of bacterial volatile signatures in culture and in EAM-colonized mouse (volatile signatures’ intensity in EAM mice subtracted by intensity in GF mice).

Discriminative features for each of the bacterial strains were identified using SparseSVM models (one vs. all43,44). Features detected in more than 20% of all samples (938 features) were then subject to mean imputation for missing values and were used for training SparseSVM classifiers and identifying bacterial volatile signatures (Data S2). We validated the model training on separately acquired test data, which yielded model accuracies of 1, 0.89, and 0.96 for B. theta, E. coli, and E. rectale, respectively. The discriminative mass/charge (m/z) features identified in this process were then annotated with various approaches, including online MS2 fragmentation and matching with the METLIN45 or MassBank46 database (using MSDIAL software47) and accurate mass matching with bacterial volatile metabolites described in a previous study48 and the KEGG database49 as a reference (organism codes: bth for B. theta, ecx for E. coli, ere for E. rectale). Putative annotations can be found in Table S1. Acetoin, isopentyl acetate, and valeric acid were found to be characteristic for B. theta. Hydroxy butyric acid, p-cresol, caproic acid, and indole were found to be characteristics for E. rectale. Catechol, L-aspartic acid, shikimic acid, pyridoxal, and pyridoxine were found to be characteristic for E. coli (see Table S1).

Next, we compared how the volatilome differs between GF mice and mice colonized with the 3-member microbiota by analyzing the data depicted in Figure 2C in more detail. Out of 2,879 detected features in mouse samples (Data S2), 41 were significantly altered between the GF and the colonized mice (false discovery rate [FDR]-adjusted p value < 0.05 and fold changes > 2; Figure 3B). The differences clustered in the pathways for butyrate/propionate metabolism and the pathways for metabolism of various amino acids (Table S2). These results are consistent with previous results using different measurement methods, namely nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis of mice colonocytes showing increased SCFAs in colonized animals50 and bacterial activities modulating host amino acid metabolism in LC-MS-based analysis in mice hepatic portal vein blood.3

It has been shown recently that signature metabolites for microbial strains in culture can also be detected if those strains colonize a host.4 We therefore tested whether the set of discriminative features we have identified in microbial cultures (Figure 3A) can also be identified in the volatilome of a colonized mouse. We subtracted the volatilome profiles of GF mice from those of colonized mice to correct for the host influence and compared the resulting profiles with those obtained from microbial cultures. Of all 110 selected features that discriminated between bacterial strains in pure culture, 27 were detected in the colonized mouse dataset (Figure 3C). As in Figures 3D, a hierarchical clustering of the identified features shows that the features of the EAM-colonized mice cluster most closely together with the B. theta features, which is in line with the observation that B. theta colonizes with a roughly 10-fold higher abundance than the other two bacterial strains (Figure 2A).

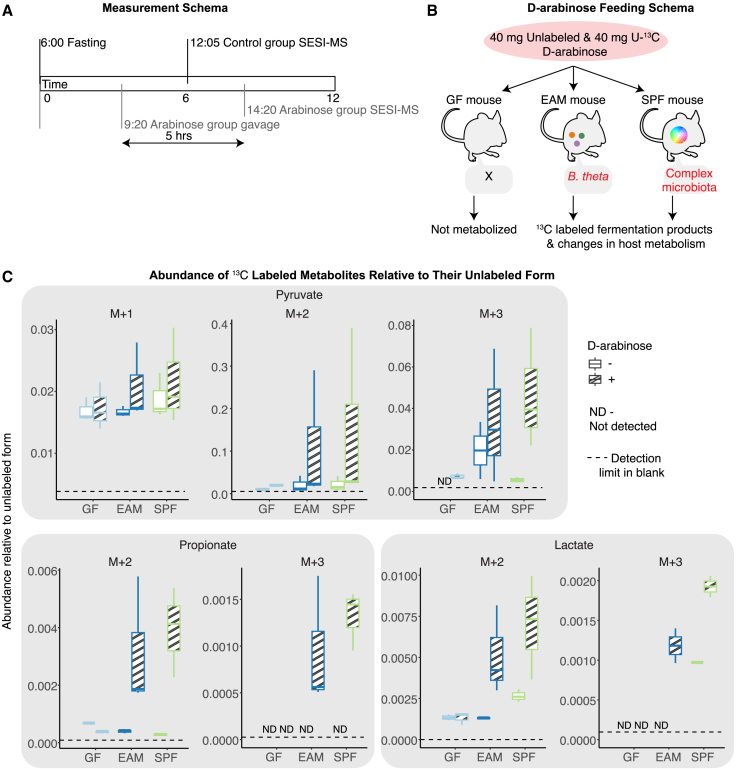

Monitoring a microbiota-targeted intervention non-invasively

Despite the identification of microbe-associated metabolites in the volatilome of colonized mice, it remains possible that some of these metabolites could be the result of microbiome-driven alterations in host metabolic activity. To categorically demonstrate that the metabolites we detect using our system are indeed directly reflective of microbial metabolism in the host, we fed fasted mice 13C-labeled D-arabinose (13C-ara; Figure 4A). This sugar is not metabolized by the mouse but can be utilized by B. theta in our EAM model as well as by other microbes in complete microbiota51,52 (Figure S2E), which metabolize it into heavy-isotope-labeled metabolites that can be detected using SESI-MS (Figure 4B). When comparing the total volatilome profiles from 13C-ara-fed mice with those of the control groups, we found an enrichment of metabolic features in various pathways, namely amino acid metabolism, butyrate metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, and central metabolism (TCA cycle) (Table S2). Focusing on the bacterial functions represented by the 27 of the unlabeled microbial features that were identified in both the headspace SESI-MS and the volatilome of mice (Figure 3C), we found that GF and EAM-colonized mice respond differently to the 13C-ara feeding (Figures S3B and S3C), i.e., clearer trends were observed in EAM colonized than in GF mice (no signature shows raw p <0.05 in GF, while four signatures show raw p <0.05 in EAM). Intriguingly, three of those signatures are E. coli specific, whereas one is B. theta specific. Our E. coli strain cannot utilize D-arabinose directly (Figure S2E), which indicates that there may be indirect effects of D-arabinose on E. coli metabolism.

Figure 4.

Bacteria-specific isotope-labeled carbon source identifies direct microbial metabolites in the volatile metabolome

(A) Measurement schema of the control group and the arabinose group.

(B) D-arabinose feeding and uptake schema for mice with various gut colonization.

(C) Labeling patterns of bacteria-related metabolites, including pyruvate, propionate, and lactate. N = 3 per group. M indicates the non-labeled ion of the molecule, and the following +1, +2, and +3 indicate the number of carbon labeled with 13C.

When considering the 13C-labeled components of the volatilome, we found that SPF and EAM mice, but not GF mice, incorporated D-arabinose-derived carbon into metabolites such as pyruvate, propionate, and lactate. This both confirmed the inert behavior of 13C-ara in the absence of microbial metabolism and the potential of SESI-MS to directly monitor microbial metabolism within a live, unperturbed host (Figure 4C).

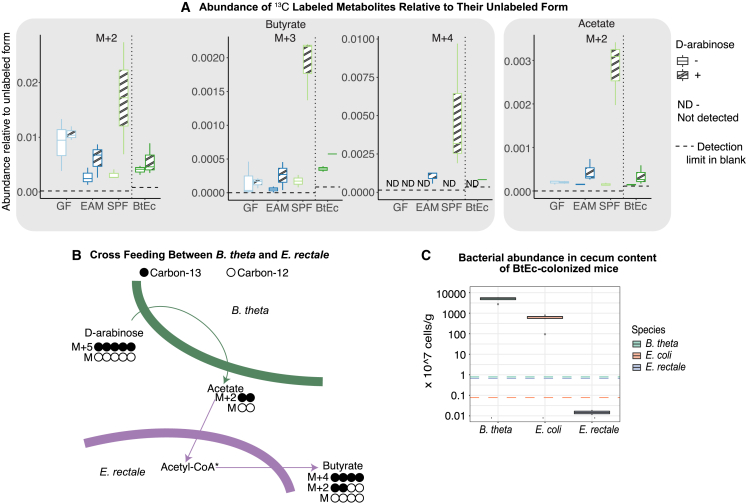

Detection of cross-feeding between microbiota members inside the host gut using SESI-MS

In the EAM host-microbiota system, the only species competent for growth on D-arabinose is B. theta (Figures 4B and S2E). After feeding the EAM mice 13C-ara, all metabolites with increased 13C labels therefore directly or indirectly result from B. theta breaking down this molecule. Intriguingly, in addition to metabolites that are well-known intermediates or products of metabolic pathways found in B. theta, such as pyruvate and propionate (Figure 4C), we found an increase in 13C-labeled versions of butyrate. Butyrate is a typical metabolite produced by E. rectale53 (Figure 5A) in large quantities, but it cannot be produced directly by B. theta. This is consistent with the observation that E. rectale can take up acetate produced by other microbes, which can then be incorporated into butyrate54,55 (Figure 5B). We observed an increase in acetate carrying two 13C labels (M+2 acetate) in the metabolite pool and increases in double (M+2) and quadruple (M+4) 13C-labeled butyrate, respectively. The simplest explanation of these data is that the M+2 acetate produced by B. theta is being cross-fed into E. rectale, where it is then incorporated into butyrate, i.e., we can use SESI-MS to quantify cross-feeding in vivo. We then performed a control experiment where mice were colonized with B. theta and E. coli only (BtEc), as E. rectale monocolonization was challenging due to oxygen sensitivity. As expected, no M+4-labeled butyrate was detected, consistent with the idea that labeled butyrate is a product of acetate cross-feeding between B. theta and E. rectale. The labeled acetate was detected at levels comparable to EAM mice.

Figure 5.

Bacteria-specific isotope-labeled carbon source reveals cross-feeding in vivo

(A) Labeling patterns of acetate and butyrate released by mice with different microbiota (N = 3 per group). The GF, EAM, and SPF mice were measured first, and the cross-feeding hypothesis was confirmed with a follow-up experiment using BtEC-colonized mice.

(B) Generation of differently labeled butyrate through cross-feeding between B. theta and E. rectale. Black circles indicate carbon-13, and white circles indicate carbon-12.

(C) Bacterial abundance in cecum content of BtEc-colonized mice (N = 3 per group), quantified using qPCR. Dotted lines indicate the detection limits.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that SESI-MS of the mouse volatilome is a powerful, non-invasive tool to analyze host-microbiota interactions. By comparing the SESI-MS signatures of the host-microbiota system in gnotobiotic animals with those of the colonizing microbes in isolation, we were able to identify the metabolite footprint of the most abundant microbes (Figure 3D). By feeding with isotope-labeled sugars that can only be used by the microbes and not by the host, we were able to conclusively show the presence of microbial metabolites in the volatilome and could use these metabolites to demonstrate within-host cross-feeding between intestinal bacteria.

It should be noted that SESI-MS analysis of air around an animal clearly does not, and is not expected to, detect all produced metabolites. Very small metabolites, such as H2 and CO2, have too low a molecular weight to be measured by our mass spectrometer, and high-molecular-weight metabolites present in the gas phase with extremely low concentration fall below the detection limit of SESI-MS. However, within the accessible molecular weight window for observing host-microbiota metabolism, we were able to recapitulate metabolic changes upon microbial colonization of a GF mouse that have previously been measured in host tissues and plasma7,56 (e.g., amino acid metabolism, xenobiotic metabolism; Table S2).

In colonized mice, bacterial numbers are always very high (around 1011cells/g; Figure 2A), and we have shown that we can measure abundant metabolic interactions non-invasively in this system. Whether it would also be possible to measure less abundant metabolic products in a host-microbiota system, e.g., metabolic interactions on a lower trophic level, remains to be tested.

Given that SESI-MS is non-invasive and does not preclude the later analysis of, e.g., host tissue and that many metabolic pathways have profound circadian rhythms, a potential application is therefore the identification of the optimal time points for endpoint analysis.20 We envisage one of the most powerful features of the SESI-MS approach to be the possibility of collecting time-resolved data on metabolic processes of a host-microbiota system in an undisturbed way. This has, up to now, only been possible by collecting fecal samples, which comes with a set of limitations. First, fecal samples are not representative of active microbial metabolism,57 which happens largely in the upper part of the large intestine.58,59,60 Second, repeated fecal sampling, even though minimally invasive, will disturb an animal’s routine if conducted over longer time periods and will therefore affect its behavior and potentially the experimental outcomes. And third, sampling of fecal material is limited in its time resolution, which can lead to gaps in information when measuring the effects of experimental interventions that work with a time delay, which is true for most experimental interventions with an effect inside the host. The SESI-MS approach presented here is not affected by any of these issues.

Given the availability of the equipment, the workflow as presented here is relatively easy to implement and allows room for customization. SESI sources are commercially available and can be interfaced with commercial high-resolution mass spectrometers.24,25,61 The data generated from SESI-MS are compatible with standard software for direct-injection MS-based metabolomics,61,62 and online MS2 fragmentation for compound identification can be performed.63,64 Development is still needed for collecting and processing time series data since most current MS-based metabolomics datasets have low time resolution or do not consider time-dependent changes at all. One example where time series of SESI-MS data at a minute-level resolution has been successfully used was for continuous monitoring of human metabolism during sleep.61

In conclusion, we describe a method for tracking metabolic changes in host-microbiota systems non-invasively. This method has the potential to generate metabolomic data for such systems at an unprecedented time resolution and with minimal to no system perturbation. Applying this system to gnotobiotic and GF mice has considerable potential to reveal relevant microbiota functions and to improve our understanding and diagnosis of microbiota-associated conditions.

Limitations of the study

Here, we have validated the SESI-MS-based method using gnotobiotic mice, for which we have extensive control over microbiota composition and extensive knowledge of the species present. For animals with an undefined microbiota, it will require considerable further research to link microbial metabolites to individual gut bacterial species. Additionally, comparing animals with widely differing microbiota may be associated with the typical confounders in direct-injection MS analysis relating to matrix effects on ionization efficiency of different compounds.65,66,67 Future developments of gas-phase standards of the most relevant molecules would allow tracking of these effects and absolute quantification of volatile-molecule concentrations. It should also be noted that the current setup does not allow the animal to be monitored continuously, first because the mice tube is a confined space and second because the accumulation of waste (e.g., feces, urine) could accentuate the ion suppression and ion competition of SESI68 and therefore interfere with data acquisition.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E. rectale | ATCC | ATCC33656 |

| E. coli HS | Lab of Mahesh Desai (University of Luxembourg) (Desai et al., 2016)69 | N/A |

| B. thetaiotaomicron | Lab of Eric Martens (University of Michigan) (Koropatkin et al., 2008)70 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| D-Arabinose, fully 13C labeled | EURISO-Top GmbH | CLM-8477-0.25 |

| D-arabinose, unlabeled | Sigma Aldrich | A3131 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw data | This paper | ETH research collection: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000554799 (mouseSESI_dataset_rev1_part1, part2 and part3) |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6 | Jackson Labs | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primer sequence for qPCR, B. theta, forward: TACTCGCCTCTTTGCAACCCTACC |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer sequence for qPCR, B. theta, reverse: GGCCCCAGATCCGAACAACAC |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer sequence for qPCR, E. coli, forward: GGTGGCTGGGTGATGTAAAACTGA | This paper | N/A |

| Primer sequence for qPCR, E. coli, reverse: ACCGCCGAGCAAAATGAAGC |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer sequence for qPCR, E. rectale, forward: GGTACAACAGGCGTTATTGTATC |

This paper | N/A |

| Primer sequence for qPCR, E. rectale, reverse: CGAAAGCACCGATCTTCTT |

This paper | N/A |

| Probe for in vivo FISH imaging: E. rectale: Texas Red modification at 5′, GCTTCTTAGTCAGGTACCG |

This paper | N/A |

| Probe for in vivo FISH imaging: E. coli: ATTO425 modification at 5′, GCCTTCCCACATCGTTT |

This paper | N/A |

| Probe for in vivo FISH imaging: B. theta 1: Cy5 modification at 5′, CCAATGTGGGGGACCTT |

Manz et al., 199671 | N/A |

| Probe for in vivo FISH imaging: B. theta 2: Cy5 modification at 5′, CATTTGCCTTGCGGCTA | Momose et al., 201172 | N/A |

| Probe for in vivo FISH imaging: B. theta 3: Cy5 modification at 5′, AGCTGCCTTCGCAATCGG |

Weller et al., 200073 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Code for data analysis | This paper | ETH research collection: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000554799 (mouseSESI_dataset_rev1_part1, part2 and part3) |

| Other | ||

| Keck Joint Clip, standard taper, joint size 14, yellow | Sigma Aldrich | Z150428 |

| PTFE-valve (two-ways, 4.5 mm outer diameter, 2 mm inner diameter) | Buerkle GmbH | 8610–0010 |

| Vacuum receiver, cone NS 14.5/23, socket NS 14.5/23 | Duran | 243100602 |

| Home-made quartz cylinder tube, length 7 cm, NS 14.5/23 | Glasbläserei Möller AG | N/A |

| 595 nm LED with a Flat Window, 45 mW, TO-39 | Thorlabs | LED595LW |

| Aspheric Condenser Lens, Ø1″, f = 16 mm, NA = 0.79, ARC: 350–700 nm | Thorlabs | ACL25416U-A |

| SM1-Threaded Mount for TO-18, TO-39, TO-46, or T-1 3/4 LEDs | Thorlabs | S1LEDM |

| SM1 Lens Tube, 2.00″ Thread Depth, One Retaining Ring Included | Thorlabs | SM1L20 |

| SM05-Threaded Mount for TO-18, TO-39, TO-46, or T-1 3/4 LEDs | Thorlabs | S05LEDM |

| 16 mm Cage Cube-Mounted Non-Polarizing Beamsplitter, 400–700 nm, M4 Tap | Thorlabs | CCM5-BS016/M |

| Large Area Mounted Silicon Photodiode, 350–1100 nm, Cathode Grounded | Thorlabs | SM05PD1A |

| SM1 Retaining Ring for Ø1″ Lens Tubes and Mounts | Thorlabs | SM1RR |

| Spanner Wrench for SM1-Threaded Retaining Rings, Graduated Scale with 0.02" (0.5 mm) Increments, Length = 3.88" | Thorlabs | SPW602 |

| Lens Tube, 3″ Thread Depth, One Retaining Ring Included | Thorlabs | SM05L30 |

| Adapter with External SM05 Threads and Internal SM1 Threads | Thorlabs | SM1A1 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Emma Slack (emma.slack@hest.ethz.ch).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and study participant details

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the Swiss Kantonal authorities (License ZH120/19 and ZH058/19; Kantonales Veteriïaramt Zürich) and performed according to the legal and ethical requirements.

Wild type C57BL/6 mice were maintained on a standard diet at the ETH Phenomics Center. Mice were re-derived Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) or re-derived germ-free and bred in individually ventilated cages under strict hygienic conditions. Gnotobiotic mice were colonized with EAM strains (the Easily Accessible Microbiota, see ‘Bacterial strains and media’) via oral gavage of mixed overnight cultured bacteria in hemin-supplemented (0.25 mg/μL) brain heart infusion (BHIS) medium. All experiments began between 8 and 9 weeks of age, with mixed-sex animals. For SESI-MS measurements, 2M1F were used for germ-free baseline group, 1M2F were used for germ-free arabinose group, 2M1F were used for EAM-colonized baseline group, 2M1F were used for EAM-colonized arabinose group, 2M1F were used for SPF baseline group, 1M2F were used for SPF arabinose group, 2M1F were used for BtEc-colonized baseline group, and 2M1F were used for BtE-colonized arabinose group (M, male; F, female).

Method details

Bacterial strains and media

For preparing bacterial cultures, Escherichia coli O9 HS, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 and Eubacterium rectale ATCC 33656 was overnight cultured and diluted to OD = 0.5 before measured by HS-SESI. For identifying volatile signatures of the three bacterial strains, hemin-supplemented (0.25 mg/μL) brain heart infusion broth was used as growth medium, 10% CO2 in nitrogen was used as atmospheric and carrier gas for HS-SESI measurement. For assessing anaerobic growth of the EAM strains inside of the headspace sampler, overnight cultures of EAM strains were subcultured to OD 0.05 in hemin-supplemented brain heart infusion broth and cultured with 10% CO2 and N2 as atmospheric and carrier gas for HS-SESI measurement.

For measuring bacterial growth in D-Arabinose, overnight cultures of EAM strains were diluted 1:1000 in D-arabinose-supplemented (0.02 M) epsilon minimal media (1% tryptone, 0.02 M NH4Cl, 50 mM NaCl, 50 μM MnCl2, 50 μM CoCl2, 50 μM MgCl2, 50 μM CaCl2, 4 μM FeSO4, 20 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM cysteine, 1.2 mg/L hemin, 1 mg/L menadione, 2 mg/L folinic acid, 1 mg/L B12, buffered to pH 7) and cultured for 8 h. Cultures were subcultured to OD 0.05 in 500 μL epsilon medium in a flat-bottom 24-well plate (Techno Plastic Products, Switzerland) and bacterial growth was measured using an Infinite 200 Pro plate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Switzerland).

EAM quantification

Fourteen 8–9 week old female EAM-colonized mice were kept under sterile conditions in two experimental isolators and kept on an ad libitum diet for 4 weeks. After euthanasia, cecum tip was removed and used for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Cecum content was collected and bacterial DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen, Germany). qPCR was performed using the FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche, Switzerland). Primers (see key resources table “Oligonucleotides”) were diluted to a final con-centration of 1 μM. Bacteria were quantified using a standard curve of known bacterial DNA concentration. DNA was amplified using a QuantStudio 7 Flex instrument (Applied Biosystems, MA, USA) with an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s.

16s rRNA sequencing

Two male SPF mice were euthanized at 8 weeks of age and cecum content was flash frozen. DNA extraction was performed as described. 16S rRNA gene sequencing was done using an Illumina HiSeq 4000 machine (Novogene). Tags corresponding to the V4 region were generated using the DADA2 pipeline74 (version 1.14), and individual reads were grouped into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). ASVs were then taxonomically annotated using the IDTAXA classifier75 in combination with the Silva v138 database.76

Tissue staining and imaging

Cecum tip harvested after euthanasia was immediately placed in 4% PFA solution and fixed overnight. Cecum tip was then transferred to a 20% sucrose solution for 4 h and flash frozen in OCT embedding matrix (Sysmex Digitana, Switzerland). Embedded blocks were cut into 5 μm sections and stored at −20°C for FISH.

For FISH staining, slides were rinsed with PBS, followed by dehydration with increasing concentrations of ethanol. FISH probes (see key resources table “Oligonucleotides”) were diluted to a final concentration of 1%(v/v) in hybridization buffer and added to slides. Slides were incubated at 50°C for 4 h. Slides were washed with washing buffer at 50°C for 20 min, then washed 3 more times with PBS at 50°C for 20 min. Slides were air dried and mounted with Vectashield HardSet Antifade Mounting Medium (Vectashield). For imaging the EAM in the cecum, a Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica) was used at ScopeM (ETH Zürich).

Real-time Headspace-SESI measurements of bacterial cultures

The Headspace-SESI system consists of an in-house developed custom-made headspace sampling system (Figure 1C and Data S1, adapted from Kaeslin et al.,77 a commercial SESI source (SuperSESI, Fossiliontech, Spain) and an Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Q-Exactive Plus, Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). All three EAM strains were able to grow in the Headspace-SESI system under the measurement condition (Figure S2D), including the strictly anaerobic bacteria E. rectale. A 20 μm Sharp Singularity Emitters (Fossiliontech, Spain) was used for electrospray using an aqueous solution of 0.1% formic acid. The sampling line temperature of the SESI source was set to 130°C and the ion chamber temperature was set to 90°C. To sample the bacterial culture’s headspace, 0.3 L min−1of humidified carrier gas was flushed through a quartz culture flask containing 4 mL bacterial culture, and introduced into the SESI source. Nine cultures per bacterial strains or the BHIS culture media were prepared as described in STAR Methods “Bacterial strains and media” and measured with HS-SESI. The humidifier, the headspace sampler and all gas tubing in between were kept at 37°C. Optical density at wavelength = 595 nm was recorded in parallel. Detailed installation and light paths of the OD monitoring system were explained in Data S1.

Real-time SESI measurements of mice

When measuring volatile released from mice, the headspace sampling system was replaced by an air-tight mouse tunnel (7 cm diameter, 11 cm length). The mouse tunnels were fabricated from poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) and had polypropylen (PP) caps. The mouse tunnel was wrapped in red plastic foil, in order to reduce stress of the experiment animals. Nine 8–9 week old mixed sex germ-free, EAM-colonized, or SPF mice were housed under sterile conditions and kept on an ad libitum diet for 1 week. At the start of the experiment, mice were fasted from 6 a.m. (zeitgeber 0). At zeitgeber 6, mice were restrained and urination was stimulated, and subsequently transferred individually to a mouse tunnel connected to SESI-MS. 0.3 L min−1 of humidified medical air (Pangas, Switzerland) was flushed through the mouse tunnel, and introduced into the SESI source. The humidifier, the mouse tunnel and all gas tubing in between were kept at room temperature (22°C). Mice were euthanized within 30 min of headspace measurements. Content from the cecum base was collected and immediately flash frozen, followed by storage at −80°C and the short chain fatty acids were quantified using a previously described method.7,78 The following ratio of cecum weight and body weight were used: 0.0843 for germ-free mice, 0,0891 for EAM mice and 0.0187 for SPF mice.7

Mouse D-arabinose feeding

A visual summary of the D-arabinose feeding and measurement is in Figure 4A. Nine 8-9-week-old mixed-sex germ-free, EAM-colonized, or SPF mice were housed under sterile conditions and kept on an ad libitum diet for 1 week. At the start of the experiment, mice were fasted from 6 a.m. (zeitgeber 0). At zeitgeber 3, 3 mice were given a 100 μL mixture of 40 mg U-13C labeled D-arabinose and 40 mg unlabeled D-arabinose via oral gavage, with 10 min between each gavage. Five hours post-gavage, mouse headspace was measured in the SESI-Orbitrap system for five times 100 s for each mouse. Three 8-9-week-old mixed-sex BtEc-colonized mice were later used in a follow-up experiment following the same procedure.

Taking into account the fact that the Orbitrap technology may suffer from deviating relative isotopic abundance caused by matrix,79 we measured mice without 13C-labeled arabinose as the baseline measurement to be compared with the mice at the same condition but fed with D-arabinose, so that their background metabolome are comparable. Mouse colonization, arabinose feeding and SESI-MS measurements were reproducible in a further experiment with less animals and in which a 6 h time window was used between arabinose feeding and volatilome measurements (Figure S4).

MS settings for SESI measurements

Data was acquired on the Orbitrap in profile mode. For both positive and negative mode acquisition, the following settings were used: an ion transfer tube temperature 250°C, a resolution of 140′000 at m/z = 200, RF lens set to 55%, and a maximum injection time of 100 ms. The automatic gain control (AGC) target was set to 5 · 106. For bacterial volatiles, data were acquired with full scan over a range from m/z = 50–500. For mouse volatiles, data were acquired with a window-splitting method previous described by Lan et al.68 As we expected the acquired data from mice to have strong signals that could potentially mask the bacterial signatures through ion suppression and ion competition, which can be overcome using window-splitting. So we used the window-splitting method when measuring mice volatiles. The whole mass range was covered by four narrow mass windows: for positive mode, m/z = 50–127, 127–143, 143–223, 223–500; for negative mode, m/z = 50–89, 89–197, 197–232, 232–500. Details for the MS acquisition method are shown in Figure S1.

For mice, features detected in less than 50% of mice samples were discarded, then signal-to-noise (blank--empty mice tubes) ratios were calculated, only features with S/N ratio >4 were kept. In total 2879 features were used for plotting and following statistics (Data S2). Regarding reproducibility, a median coefficient of variation of 2.67% were calculated for all features detected in five replicates data for individual animals.

For bacterial cultures and media, features detected in more than 70% of all samples (559 features) were kept for generating KernelPCA plot (Data S2). Features detected in more than 20% of all samples (938 features, with mean imputation for missing values) were used for training SparseSVM classifiers and identifying bacterial volatile signatures (Data S2).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Mass spectrometer data processing

Raw data generated from SESI-MS were first converted into.mzXML format via MSConvert (ProteoWizard80). The converted files were then imported into MATLAB (version R2019b, MathWorks, Natick, MA) and treated using a MATLAB code developed in-house. The following workflow is shown in Figure S2A. Briefly, peaks were picked from an overall averaged spectrum of acquired spectra during the experiment. The acquired data was then centroided using the peak boundaries defined from the master spectra, and a.csv file containing the intensities of the peaks per scan was generated for each of the acquired MS data file.

Statistics

All statistics were done using in-house developed R codes. For prepossessing mass spectrometer data, the raw intensities were first normalized against total ion current, then the log2 of median intensities of the acquired scans were used as quantification.

Student’s t test with FDR adjustment was used for calculating p values for the volcano plots. The pathway enrichment was done using the mummichog function of MetaboanalystR package.81,82 To find bacterial volatile signatures, missing values in data were first filled with mean of detected intensity and then SparseSVM classification was done using the function sparseSVM in R, multiple classifiers were trained in one-vs-all fashion in order to find bacterial volatile signatures for each of the EAM strains. The overlaps of the selected volatile signatures among strains and the volatile features of mice were plotted in the Venn plot (Figure 3C). The intensities of bacterial volatile signatures that were detected in mice were first imputed with minimum detected intensity, extracted from both the bacterial and the mice dataset and then visualized in the heatmap in Figure 3D. The ratio between the MS signal intensities of the labeled form and the unlabeled form is calculated and visualized in Figures 4 and 5 as the labeling pattern of D-arabinose metabolites, the MS signal intensities of the metabolites are shown in Figures S5, S6, and S7.

Additional resources

Design file of the bacterial headspace sampling system

The CAD design files of the headspace sampling system were prepared using Autodesk Inventor Professional 2023 and available as Data S1. A figure explaining the design is also included in the data (Figure_HeadspaceSamplerDesign).

Preprocessed data for preparing figures

The preprocessed MS data for preparing mouse PCA plot (Figure 2C), the bacterial kernelPCA plot (Figure 3A) and bacterial SparseSVM model (Figure 3C) are available as Data S2.

Acknowledgments

We thank ScopeM (ETH Zurich) for providing us access to the confocal microscope and RCHCI and EPIC for housing experimental animals. We also thank Anna Sintsova for help with data treatment and Christian Marro and Christoph Bärtschi for building the hardware and electronics of the headspace sampling system. This work is part of the Zurich Exhalomics flagship project under the umbrella of “Hochschulmedizin Zürich.” We gratefully acknowledge financial support from SNF (no. 1851228) to G.G. and the Heidi Ras Stiftung and Zurich Foundation to B.S. E.S. acknowledges the support of a Novartis Freenovation grant (2015), a Swiss National Science Foundation Project grant (310030 185128), Botnar Research Center for Child Health MIP 2020 “Microbiota Engineering for Child Health,” and the NCCR Microbiomes, a National Center of Competence in Research, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 180575).

Author contributions

J.L., G.G., M.A., R.Z., and E.S. designed the research. J.L. performed the MS experiments and data evaluation, with technical advice from B.S. G.G. performed the biological experiments and data evaluation. B.W. built the optical density meter for the headspace measurement device. J.L., M.A., and E.S. wrote the manuscript, to which G.G. contributed, in cooperation with all other authors. R.Z. and E.S. acquired funding support.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 26, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2023.100539.

Contributor Information

Markus Arnoldini, Email: markus.arnoldini@hest.ethz.ch.

Renato Zenobi, Email: zenobi@org.chem.ethz.ch.

Emma Slack, Email: emma.slack@hest.ethz.ch.

Supplemental information

The numbers in the ”source” column indicate the following annotation methods: 1-described in a previous study as bacterial volatile metabolites48 2-in KEGG database49, 3- MS2 matching with METLIN database45, 4-MS2 matching with MassBank46 using MSDIAL software47, 5-formula only and 0-No available annotation.

Data and code availability

-

•

All original data have been deposited at ETH Zurich research collection (https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/) under DOI https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000554799 (mouseSESI_dataset_rev1_part1, part2 and part3).

-

•

All original code has been deposited at ETH Zurich research collection (https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/) under DOI https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000554799 (mouseSESI_dataset_rev1_part1, part2 and part3), and is publicly available as of the date of publication.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Litvak Y., Byndloss M.X., Bäumler A.J. Colonocyte metabolism shapes the gut microbiota. Science. 2018;362 doi: 10.1126/science.aat9076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dodd D., Spitzer M.H., Van Treuren W., Merrill B.D., Hryckowian A.J., Higginbottom S.K., Le A., Cowan T.M., Nolan G.P., Fischbach M.A., et al. A gut bacterial pathway metabolizes aromatic amino acids into nine circulating metabolites. Nature. 2017;551:648–652. doi: 10.1038/nature24661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mardinoglu A., Shoaie S., Bergentall M., Ghaffari P., Zhang C., Larsson E., Bäckhed F., Nielsen J. The gut microbiota modulates host amino acid and glutathione metabolism in mice. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015;11:834. doi: 10.15252/msb.20156487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han S., Van Treuren W., Fischer C.R., Merrill B.D., DeFelice B.C., Sanchez J.M., Higginbottom S.K., Guthrie L., Fall L.A., Dodd D., et al. A metabolomics pipeline for the mechanistic interrogation of the gut microbiome. Nature. 2021;595:415–420. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03707-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wastyk H.C., Fragiadakis G.K., Perelman D., Dahan D., Merrill B.D., Yu F.B., Topf M., Gonzalez C.G., Van Treuren W., Han S., et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell. 2021;184:4137–4153.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin R., Liu W., Piao M., Zhu H. A review of the relationship between the gut microbiota and amino acid metabolism. Amino Acids. 2017;49:2083–2090. doi: 10.1007/s00726-017-2493-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoces D., Lan J., Sun W., Geiser T., Stäubli M.L., Cappio Barazzone E., Arnoldini M., Challa T.D., Klug M., Kellenberger A., et al. Metabolic reconstitution of germ-free mice by a gnotobiotic microbiota varies over the circadian cycle. PLoS Biol. 2022;20 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kindt A., Liebisch G., Clavel T., Haller D., Hörmannsperger G., Yoon H., Kolmeder D., Sigruener A., Krautbauer S., Seeliger C., et al. The gut microbiota promotes hepatic fatty acid desaturation and elongation in mice. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3760. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05767-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Just S., Mondot S., Ecker J., Wegner K., Rath E., Gau L., Streidl T., Hery-Arnaud G., Schmidt S., Lesker T.R., et al. The gut microbiota drives the impact of bile acids and fat source in diet on mouse metabolism. Microbiome. 2018;6:134. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0510-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koppel N., Maini Rekdal V., Balskus E.P. Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science. 2017;356 doi: 10.1126/science.aag2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wikoff W.R., Anfora A.T., Liu J., Schultz P.G., Lesley S.A., Peters E.C., Siuzdak G. Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3698–3703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812874106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilmanski T., Rappaport N., Earls J.C., Magis A.T., Manor O., Lovejoy J., Omenn G.S., Hood L., Gibbons S.M., Price N.D. Blood metabolome predicts gut microbiome α-diversity in humans. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:1217–1228. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández-Calleja J.M., Konstanti P., Swarts H.J., Bouwman L.M., Garcia-Campayo V., Billecke N., Oosting A., Smidt H., Keijer J., van Schothorst E.M. Non-invasive continuous real-time in vivo analysis of microbial hydrogen production shows adaptation to fermentable carbohydrates in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33619-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halatchev I.G., O’Donnell D., Hibberd M.C., Gordon J.I. Applying indirect open-circuit calorimetry to study energy expenditure in gnotobiotic mice harboring different human gut microbial communities. Microbiome. 2019;7:158. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0769-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bäckhed F., Ding H., Wang T., Hooper L.V., Koh G.Y., Nagy A., Semenkovich C.F., Gordon J.I. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang M.-Z., Yuan C.-H., Cheng S.-C., Cho Y.-T., Shiea J. Ambient ionization mass spectrometry. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2010;3:43–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.111808.073702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Gómez D., Gaisl T., Bregy L., Cremonesi A., Sinues P.M.-L., Kohler M., Zenobi R. Real-time quantification of amino acids in the Exhalome by secondary electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry: a proof-of-principle study. Clin. Chem. 2016;62:1230–1237. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.256909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tejero Rioseras A., Singh K.D., Nowak N., Gaugg M.T., Bruderer T., Zenobi R., Sinues P.M.-L. Real-time monitoring of tricarboxylic acid metabolites in exhaled breath. Anal. Chem. 2018;90:6453–6460. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berna A.Z., Odom John A.R. Breath Metabolites to Diagnose Infection. Clin. Chem. 2021;68:43–51. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvab218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X., Martinez-Lozano Sinues P., Dallmann R., Bregy L., Hollmén M., Proulx S., Brown S.A., Detmar M., Kohler M., Zenobi R. Drug pharmacokinetics determined by real-time analysis of mouse breath. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015;54:7815–7818. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Lozano Sinues P., Kohler M., Brown S.A., Zenobi R., Dallmann R. Gauging circadian variation in ketamine metabolism by real-time breath analysis. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:2264–2267. doi: 10.1039/c6cc09061c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Hee B., Wells J.M. Microbial regulation of host physiology by short-chain fatty acids. Trends Microbiol. 2021;29:700–712. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu C., Siems W.F., Hill H.H. Secondary electrospray ionization ion mobility spectrometry/mass spectrometry of illicit drugs. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:396–403. doi: 10.1021/ac9907235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lan J., Blanco Parte F., Vidal-de-Miguel G., Zenobi R. Breathborne Biomarkers and the Human Volatilome. Elsevier; 2020. Secondary electrospray ionization; pp. 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh K.D., Tancev G., Decrue F., Usemann J., Appenzeller R., Barreiro P., Jaumà G., Macia Santiago M., Vidal de Miguel G., Frey U., et al. Standardization procedures for real-time breath analysis by secondary electrospray ionization high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019;411:4883–4898. doi: 10.1007/s00216-019-01764-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Timm C.M., Lloyd E.P., Egan A., Mariner R., Karig D. Direct growth of bacteria in headspace vials allows for screening of volatiles by gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:491. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbig J., Müller M., Schallhart S., Titzmann T., Graus M., Hansel A. On-line breath analysis with PTR-TOF. J. Breath Res. 2009;3 doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/3/2/027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sovová K., Čepl J., Markoš A., Španěl P. Real time monitoring of population dynamics in concurrent bacterial growth using SIFT-MS quantification of volatile metabolites. Analyst. 2013;138:4795–4801. doi: 10.1039/c3an00472d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zamora D., Amo-Gonzalez M., Lanza M., Fernández de la Mora G., Fernández de la Mora J. Reaching a vapor sensitivity of 0.01 parts per quadrillion in the screening of large volume freight. Anal. Chem. 2018;90:2468–2474. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.García-Gómez D., Martínez-Lozano Sinues P., Barrios-Collado C., Vidal-de-Miguel G., Gaugg M., Zenobi R. Identification of 2-alkenals, 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals, and 4-hydroxy-2, 6-alkadienals in exhaled breath condensate by UHPLC-HRMS and in breath by real-time HRMS. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:3087–3093. doi: 10.1021/ac504796p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu J., Bean H.D., Jiménez-Díaz J., Hill J.E. Secondary electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (SESI-MS) breathprinting of multiple bacterial lung pathogens, a mouse model study. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013;114:1544–1549. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00099.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H., Zhu J. Differentiating antibiotic-resistant staphylococcus aureus using secondary electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2018;90:12108–12115. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teilmann A.C., Kalliokoski O., Sørensen D.B., Hau J., Abelson K.S.P. Manual versus automated blood sampling: impact of repeated blood sampling on stress parameters and behavior in male NMRI mice. Lab. Anim. 2014;48:278–291. doi: 10.1177/0023677214541438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadler A.M., Bailey S.J. Repeated daily restraint stress induces adaptive behavioural changes in both adult and juvenile mice. Physiol. Behav. 2016;167:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Den Besten G., Van Eunen K., Groen A.K., Venema K., Reijngoud D.-J., Bakker B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macfarlane G.T., Macfarlane S. Fermentation in the human large intestine: its physiologic consequences and the potential contribution of prebiotics. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011;45:S120–S127. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31822fecfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dalile B., Van Oudenhove L., Vervliet B., Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota–gut–brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;16:461–478. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saresella M., Marventano I., Barone M., La Rosa F., Piancone F., Mendozzi L., d’Arma A., Rossi V., Pugnetti L., Roda G., et al. Alterations in circulating fatty acid are associated with gut microbiota dysbiosis and inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1390. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanna S., van Zuydam N.R., Mahajan A., Kurilshikov A., Vich Vila A., Võsa U., Mujagic Z., Masclee A.A.M., Jonkers D.M.A.E., Oosting M., et al. Causal relationships among the gut microbiome, short-chain fatty acids and metabolic diseases. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:600–605. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0350-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahowald M.A., Rey F.E., Seedorf H., Turnbaugh P.J., Fulton R.S., Wollam A., Shah N., Wang C., Magrini V., Wilson R.K., et al. Characterizing a model human gut microbiota composed of members of its two dominant bacterial phyla. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5859–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901529106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Høverstad T., Midtvedt T. Short-chain fatty acids in germfree mice and rats. J. Nutr. 1986;116:1772–1776. doi: 10.1093/jn/116.9.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korem T., Zeevi D., Suez J., Weinberger A., Avnit-Sagi T., Pompan-Lotan M., Matot E., Jona G., Harmelin A., Cohen N., et al. Growth dynamics of gut microbiota in health and disease inferred from single metagenomic samples. Science. 2015;349:1101–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan M., Wang L., Tsang I.W. ICML. 2010. Learning sparse svm for feature selection on very high dimensional datasets. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yi C., Huang J. Semismooth newton coordinate descent algorithm for elastic-net penalized huber loss regression and quantile regression. J. Comput. Graph Stat. 2017;26:547–557. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guijas C., Montenegro-Burke J.R., Domingo-Almenara X., Palermo A., Warth B., Hermann G., Koellensperger G., Huan T., Uritboonthai W., Aisporna A.E., et al. METLIN: a technology platform for identifying knowns and unknowns. Anal. Chem. 2018;90:3156–3164. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horai H., Arita M., Kanaya S., Nihei Y., Ikeda T., Suwa K., Ojima Y., Tanaka K., Tanaka S., Aoshima K., et al. MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010;45:703–714. doi: 10.1002/jms.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsugawa H., Cajka T., Kind T., Ma Y., Higgins B., Ikeda K., Kanazawa M., VanderGheynst J., Fiehn O., Arita M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:523–526. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bos L.D.J., Sterk P.J., Schultz M.J. Volatile metabolites of pathogens: a systematic review. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanehisa M., Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donohoe D.R., Garge N., Zhang X., Sun W., O’Connell T.M., Bunger M.K., Bultman S.J. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 2011;13:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium. Waterston R.H., Lindblad-Toh K., Birney E., Rogers J., Abril J.F., Agarwal P., Agarwala R., Ainscough R., Alexandersson M., et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Degnan B.A., Macfarlane G.T. Carbohydrate utilization patterns and substrate preferences in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Anaerobe. 1995;1:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s1075-9964(95)80392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Louis P., Flint H.J. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;19:29–41. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shoaie S., Karlsson F., Mardinoglu A., Nookaew I., Bordel S., Nielsen J. Understanding the interactions between bacteria in the human gut through metabolic modeling. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2532. doi: 10.1038/srep02532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barcenilla A., Pryde S.E., Martin J.C., Duncan S.H., Stewart C.S., Henderson C., Flint H.J. Phylogenetic relationships of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1654–1661. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1654-1661.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moriya T., Saito K., Tajima Y., Harada T.L., Araki Y., Sugimoto K., Tokuuye K. Effect of gut microbiota on host whole metabolome. Metabolomics. 2017;17:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zmora N., Zilberman-Schapira G., Suez J., Mor U., Dori-Bachash M., Bashiardes S., Kotler E., Zur M., Regev-Lehavi D., Brik R.B.-Z., et al. Personalized gut mucosal colonization resistance to empiric probiotics is associated with unique host and microbiome features. Cell. 2018;174:1388–1405.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cremer J., Arnoldini M., Hwa T. Effect of water flow and chemical environment on microbiota growth and composition in the human colon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:6438–6443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619598114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matysik S., Le Roy C.I., Liebisch G., Claus S.P. Metabolomics of fecal samples: a practical consideration. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016;57:244–255. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heinzmann S.S., Schmitt-Kopplin P. Deep metabotyping of the murine gastrointestinal tract for the visualization of digestion and microbial metabolism. J. Proteome Res. 2015;14:2267–2277. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nowak N., Gaisl T., Miladinovic D., Marcinkevics R., Osswald M., Bauer S., Buhmann J., Zenobi R., Sinues P., Brown S.A., et al. Rapid and reversible control of human metabolism by individual sleep states. Cell Rep. 2021;37 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lan J., Gisler A., Bruderer T., Sinues P., Zenobi R. Monitoring peppermint washout in the breath metabolome by secondary electrospray ionization-high resolution mass spectrometry. J. Breath Res. 2021;15:026003. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/ab9f8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gisler A., Lan J., Singh K.D., Usemann J., Frey U., Zenobi R., Sinues P. Real-time breath analysis of exhaled compounds upon peppermint oil ingestion by secondary electrospray ionization-high resolution mass spectrometry: technical aspects. J. Breath Res. 2020;14 doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/ab9f8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaeslin J., Zenobi R. Resolving isobaric interferences in direct infusion tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2022;36 doi: 10.1002/rcm.9266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Urban M., Enot D.P., Dallmann G., Körner L., Forcher V., Enoh P., Koal T., Keller M., Deigner H.-P. Complexity and pitfalls of mass spectrometry-based targeted metabolomics in brain research. Anal. Biochem. 2010;406:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sarvin B., Lagziel S., Sarvin N., Mukha D., Kumar P., Aizenshtein E., Shlomi T. Fast and sensitive flow-injection mass spectrometry metabolomics by analyzing sample-specific ion distributions. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3186. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17026-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rioseras A.T., Gaugg M.T., Martinez-Lozano Sinues P. Secondary electrospray ionization proceeds via gas-phase chemical ionization. Anal. Methods. 2017;9:5052–5057. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lan J., Kaeslin J., Greter G., Zenobi R. Minimizing ion competition boosts volatile metabolome coverage by secondary electrospray ionization orbitrap mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2021;1150 doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Desai M.S., Seekatz A.M., Koropatkin N.M., Kamada N., Hickey C.A., Wolter M., Pudlo N.A., Kitamoto S., Terrapon N., Muller A., et al. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell. 2016;167:1339–1353.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koropatkin N.M., Martens E.C., Gordon J.I., Smith T.J. Starch catabolism by a prominent human gut symbiont is directed by the recognition of amylose helices. Structure. 2008;16:1105–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manz W., Amann R., Ludwig W., Vancanneyt M., Schleifer K.-H. Application of a suite of 16S rRNA-specific oligonucleotide probes designed to investigate bacteria of the phylum cytophaga-flavobacter-bacteroides in the natural environment. Microbiology. 1996:1097–1106. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Momose Y., Park S.H., Miyamoto Y., Itoh K. Design of species-specific oligonucleotide probes for the detection of Bacteroides and Parabacteroides by fluorescence in situ hybridization and their application to the analysis of mouse caecal Bacteroides–Parabacteroides microbiota. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;111:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weller R., Glöckner F.O., Amann R. 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for the in situ detection of members of the phylum Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2000;23:107–114. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(00)80051-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Callahan B.J., McMurdie P.J., Rosen M.J., Han A.W., Johnson A.J.A., Holmes S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murali A., Bhargava A., Wright E.S. IDTAXA: a novel approach for accurate taxonomic classification of microbiome sequences. Microbiome. 2018;6:140. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0521-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Quast C., Pruesse E., Yilmaz P., Gerken J., Schweer T., Yarza P., Peplies J., Glöckner F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaeslin J., Micic S., Weber R., Müller S., Perkins N., Berger C., Zenobi R., Bruderer T., Moeller A. Differentiation of Cystic Fibrosis-Related Pathogens by Volatile Organic Compound Analysis with Secondary Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Metabolites. 2021;11:773. doi: 10.3390/metabo11110773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liebisch G., Ecker J., Roth S., Schweizer S., Öttl V., Schött H.F., Yoon H., Haller D., Holler E., Burkhardt R., Matysik S. Quantification of fecal short chain fatty acids by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry—investigation of pre-analytic stability. Biomolecules. 2019;9:121. doi: 10.3390/biom9040121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaufmann A., Walker S. Accuracy of relative isotopic abundance and mass measurements in a single-stage orbitrap mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2012;26:1081–1090. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Adusumilli R., Mallick P. Proteomics. Springer; 2017. Data conversion with ProteoWizard msConvert; pp. 339–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li S., Park Y., Duraisingham S., Strobel F.H., Khan N., Soltow Q.A., Jones D.P., Pulendran B. Predicting network activity from high throughput metabolomics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chong J., Yamamoto M., Xia J. MetaboAnalystR 2.0: from raw spectra to biological insights. Metabolites. 2019;9:57. doi: 10.3390/metabo9030057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The numbers in the ”source” column indicate the following annotation methods: 1-described in a previous study as bacterial volatile metabolites48 2-in KEGG database49, 3- MS2 matching with METLIN database45, 4-MS2 matching with MassBank46 using MSDIAL software47, 5-formula only and 0-No available annotation.

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All original data have been deposited at ETH Zurich research collection (https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/) under DOI https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000554799 (mouseSESI_dataset_rev1_part1, part2 and part3).

-

•

All original code has been deposited at ETH Zurich research collection (https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/) under DOI https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000554799 (mouseSESI_dataset_rev1_part1, part2 and part3), and is publicly available as of the date of publication.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.