Abstract

Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase 1 (PRS—I) is an enzyme involved in nucleotide metabolism. Pathogenic variants in the PRPS1 are rare and PRS-I deficiency can manifest as three clinical syndromes: X-linked non-syndromic sensorineural deafness (DFN2), X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 5 (CMTX5) and Arts syndrome. We present a Slovenian patient with PRS-I enzyme deficiency due to a novel pathogenic variant – c.424G > A (p.Val142Ile) in the PRPS1 gene, who presented with gross motor impairment, severe sensorineural deafness, balance issues, ataxia, and frequent respiratory infections. In addition, we report the findings of a systemic literature review of all described male cases of Arts syndrome and CMTX5 as well as intermediate phenotypes. As already proposed by other authors, our results confirm PRS-I deficiency should be viewed as a phenotypic continuum rather than three separate syndromes because there are multiple reports of patients with an intermediary clinical presentation.

Keywords: Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase 1, PRPS1, PRS-I super-activity, PRS-I deficiency, Arts syndrome, X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 5

1. Introduction

Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase 1 (PRS—I; OMIM: #311850), an enzyme involved in nucleotide metabolism, is encoded by the PRPS1 gene and catalyzes the production of 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) [1]. PRPP is a substrate for the de novo synthesis of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides and is required in the salvage pathway of purine bases [2]. Traits in the PRPS1 gene are inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern: males are predominantly affected and exhibit a more severe phenotype while female carriers can present with milder symptoms [1,3,4]. Pathogenic variants in the PRPS1 are rare and manifest with four clinical syndromes depending on PRS-I enzyme activity: increased activity results in PRS-I super-activity syndrome (OMIM: #300661), on the contrary, loss-of-function is associated with X-linked non-syndromic sensorineural deafness (DFN2, OMIM: #304500), X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 5 (CMTX5, OMIM: #311070) and Arts syndrome (OMIM: #301835) [2]. Previous reports indicate that clinical presentations of patients overlap between these disorders, particularly in loss-of-function variants, thus, some authors suggest PRS-I loss-of-function should be considered as a phenotypic continuum and not as three distinct syndromes [5]. PRPS1-related disorders exhibit symptoms resulting from purine overproduction, neurological and hemato-immunological symptoms. It has been proposed that neurological symptoms arise due to impaired myelin synthesis and hemato-immunological symptoms (i.e. recurrent infections) are caused by impaired hematopoietic differentiation [2].

PRS-I super-activity (also over-activity) is caused by either gain-of-function variants or a disruption in one of the allosteric sites required for feedback inhibition [4]. Disease onset is dependent upon the pathogenic variant causing the syndrome. Most commonly it is characterized by adult onset uric acid crystalluria, urinary stones, and gouty arthritis, however, more severe phenotypes present as early childhood with gouty arthritis and neurodevelopmental abnormalities (sensorineural deafness, hypotonia, mental retardation) [2,6].

PRS-I deficiency can lead to three conditions. Isolated sensorineural deafness is characteristic of DFN2, the mildest form of PRS-I deficiency. CMTX5 is characterized by peripheral neuropathy, early-onset (prelingual) bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, and optic neuropathy, the onset of visual impairment being between seven and 20 years, while intellect and life span are normal. Arts syndrome is the most extreme form of enzyme deficiency, characterized by ataxia, weakness, deafness, loss of vision in early childhood, and frequent respiratory infections with a fatal outcome usually in early childhood. Optic atrophy and deafness are significant in Arts syndrome and according to the Arts description of the syndrome, no significant biochemical or immunological defects were detected [1,7]. There are also females with milder symptoms (ophthalmological symptoms, hearing loss, ataxia) associated to PRPS1 pathogenic variants [1,3].

Currently, there is no cure for these disorders, however, there are treatment options to alleviate symptoms and delay disease progression. For PRS-I super-activity, it is necessary to prescribe allopurinol to help decrease uric acid production and prevent urate crystal deposition [4]. Co-therapy with S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and nicotinamide have been reported to improve muscular strength, mitigate infections and improve overall wellbeing in Arts syndrome [2,8,9].

PRS-I disorders are rare and there are only a few resources available to establish a treatment course and prognosis. To date, there are less than fifty case reports of PRS-I deficiency in the literature and there is no up-to-date summary of patients' information available. We present a patient from Slovenia with a novel mutation resulting in PRS-I deficiency and a systematic review of all similar reported cases in the literature.

2. Methods

We performed a retrospective evaluation by assessing the electronic medical records of a patient who was followed at the University Children's Hospital, University Medical Centre Ljubljana up until 10.5 years of age. We also performed a clinical investigation and genetic testing of his two siblings and mother. CARE reporting guidelines were followed [10].

Diagnosis of PRS-I deficiency was made through comparison of the patient's clinical characteristics to similar cases in the literature and confirmed with genetic and enzyme activity testing.

UK-WHO charts were used to calculate percentiles/Z scores for anthropometric measurements. The laboratory measurements were analyzed from blood and urine samples by standard methods. Abdomen ultrasonography was performed and interpreted by respective specialists. We used a standardized questionnaire to screen for sleep disordered breathing and performed overnight polygraphy to assess the patient for possible obstructive sleep apnea.

Brainstem auditory evoked potential testing with audiometry was performed by an otolaryngologist to assess the patient's hearing impairment. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) using multivoxel pattern analysis was performed to elucidate the patient's neurological symptoms. Electrophysiological investigations included motor and sensory nerve conduction studies (NCS) and needle electromyography (EMG).

Genetic analysis was performed by next-generation sequencing (NGS). The regions of interest were enriched using TruSight One library enrichment kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer's instructions and sequenced on the MiSeq desktop sequencer with MiSeq Reagent kit v3 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). A panel of 104 genes associated with deafness and mental retardation, including the PRPS1 gene, was used for selection of variants. In silico pathogenicity predictions were assessed using Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score [11], Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT) [12] and PolyPhen-2 [13,14] algorithms. Sanger sequencing was used for cascade screening of the patient's mother and two sisters.

Enzyme analysis of PRS-I activity was performed in erythrocytes by obtaining venous blood samples with lithium heparin from the patient and his mother as well as in cultured fibroblasts from our patient and an unrelated healthy control patient. The samples were sent to the Department for Clinical Biochemistry, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain, and analyzed according to previously published methods [15,16].

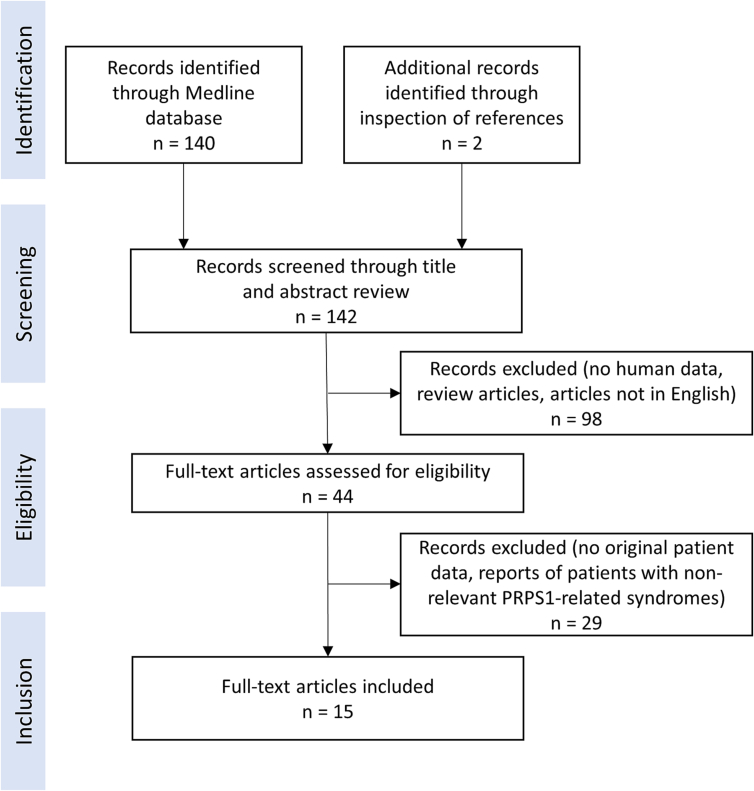

A systematic literature review was performed following PRISMA reporting guidelines on November 4th, 2022, to combine the data of all known patients with CMTX5 and Arts disease as well as intermediate phenotypes. We searched the Medline database for available case report articles on patients with pathogenic PRPS1 variants using the search term “PRPS1” and identified 140 research articles, in addition, inspection of references of these articles identified 2 more. During the screening process of article titles and abstracts, we excluded all that did not report human data, review articles, and articles not available in English. The remaining 44 articles were assessed thoroughly for eligibility. We included 15 articles that reported original patient data (Fig. 1) and that contained information on patients with CMTX5 or Arts syndrome as well as intermediate phenotypes. When reviewing the selected articles, we focused on symptoms according to organ systems, genetic testing results, enzyme activity, syndrome type, uric acid levels, brain MRI, gender, and ancestry.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for systematic literature review.

3. Results

3.1. CASE presentation

A 1.5-year-old boy was referred to our hospital due to the failure to thrive. Family history was unremarkable. He was born at 37 weeks of gestation and was small for gestational age with a birthweight of 2550 g (3rd percentile), birth length of 47 cm (3rd percentile), and head circumference of 32 cm (3rd percentile). In the neonatal period, he was hypotonic and breastfed poorly. At 6 months of age, he had signs of developmental delay, joint hypermobility, strabismus, and dysplastic signs – hypertelorism, epicanthus, a smaller chin, triangularly shaped adenoid face, and downward turned eye slits. Between 1 and 3 years of age, he developed gross motor impairment (started walking at 2 years), obstructive sleep apnea, and had frequent bacterial respiratory infections. Severe sensorineural deafness gradually developed, requiring the use of hearing devices and cochlear implants bilaterally at 6 years of age.

Initial laboratory analyses at referral (complete blood count, electrolytes, biochemistry, urine analysis; uric acid levels were not checked at this stage) as well as abdominal ultrasound were unremarkable. Plasma amino acid and urine organic acid levels were within reference ranges.

Throughout the follow-up period, the boy had marginally higher average serum uric acid levels 387 μmol/L (age adjusted reference range 120–330 μmol/L) in serum and normal average 24-h urine uric acid excretion 3.65 mmol/24 h (reference range 1.2–6.0 mmol/24 h). Multiple measurements revealed normal immunoglobulin A (IgA) concentration and normal lymphocyte subpopulations.

At 5 years of age, a head MRI showed numerous dilated Robin Virchow spaces along the atria of the lateral ventricles (and temporo-occipitally peri-ventricularly) and hypoplasia of corpus callosum splenium. These findings were deemed non-specific. Electrophysiological examinations (NCS and EMG) at 8 years confirmed the presence of peripheral motor neuropathy, predominantly of axonal type, with demyelinating changes on the tested nerves, while the sensory nervous system was intact. EMG showed chronic and, in some segments, subacute to chronic changes in motor unit action potentials. The examination was repeated at 9.5 years and his results remained unchanged.

NGS confirmed a hemizygous mutation in PRPS1 (NM_002764:c.424G > A, p.Val142Ile). This is a novel variant, assessed by predictive algorithms most likely to be pathogenic. According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria the variant is classified as likely pathogenic (PM5, PM1, PM2, PP3). There is a similar variant listed in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD), located on the same amino acid position (NM_002764:c.424G > C, p.Val142Leu, CM120487), which was found to be the cause of PRS-I super-activity with recurrent infections [17].

PRS-I activity was significantly decreased in hemolysate (0.63 nmol/h/mg protein; reference range: 70–126 nmol/h/mg protein). Enzyme analysis on fibroblasts also showed a marked decrease in PRS-I activity with no erroneous phosphate regulation. PRS-I activity measured at 32 mM phosphate concentration was 128 ± 50 nmol/h/mg protein (reference range 214 ± 67 nmol/h/mg protein; control 178 nmol/h/mg protein), and 31 ± 7 nmol/h/mg protein (control 21 nmol/h/mg) at 3 mM phosphate concentration. From these findings, it was estimated that the patient has a decrease in PRS-I activity of approximately 60%.

At last follow-up, our patient had severe issues with balance and ataxia, cognitive function impairment, a short attention span, and difficulties in verbal and non-verbal communication. Thorough immunological evaluation didn't reveal major dysfunction of his immune system. He had annual check-ups with a pediatric nephrologist because of a cyst with hyperechoic inclusions in his left kidney, hypercalciuria, transient microhematuria, and enuresis. He had strabismus and mild hypermetropia, however, ophthalmological investigations have not revealed any other abnormalities.

With the aim of symptom alleviation, low protein/low fructose diet and later low purine/low fructose diet were started at the age of 7 years, resulting in marginal cognitive improvement together with muscle weakness exacerbation as perceived by the patient's parents, thus all dietary restrictions were suspended. At 8 years he was prescribed SAM therapy (500 mg/day, approximately 17 mg/kg/day) along with niacin (20 mg per day, approximately 0.7 mg/kg/day) and epigallocathechin gallate (EGCG; 400 mg per day, approximately 13 mg/kg/day), which seemed to improve his balance according to the report of his parents, however, no significant effect was observed with other symptoms. At the time this report is being written he has been taking this therapy for approximately two years.

Cascade testing confirmed the carrier status for the pathogenic variant in the boy's mother as well as one of his sisters. The mother has had issues with eyesight since birth but was otherwise asymptomatic. She had mildly increased 24-hour uric acid excretion 6.6 mmol/24 h (reference range: 1.2–6.0 mmol/24 h) and no kidney abnormalities on ultrasound. Enzyme analysis in hemolysate confirmed a decreased PRS-I activity (41.8 nmol/h/mg protein; reference range 70–126 nmol/h/mg protein). His sister was 15 years old at the time of this report and has not experienced any symptoms.

3.2. Systematic review of literature

Through the literature review, we gathered information on 8 patients with clear Arts syndrome (Table 1) and found that all described patients had ataxia, hypotonia, loss of deep tendon reflexes, mental retardation, and recurrent infections. Other common signs were hearing impairment (86% of cases), optic atrophy (71%), and areflexia (63%). Furthermore, some patients had additional ophthalmological signs, such as nystagmus (3/8 cases), restricted visual field (1/8 cases), and strabismus (1/8 cases). Changes on brain MRI were unspecific and varied from case to case. Anemia was reported in one case. All patients with Arts syndrome had normal uric acid values.

Table 1.

Secondly, we summarized the data of 14 patients with CMTX5 (Table 2). All patients presented with hearing loss and 64% of patients were found to have optic atrophy. Delayed motor development and loss of deep tendon reflexes were present in 40% of patients. Recurrent infections were reported in one out of two patients, however, not reported in others. All patients had normal uric acid values and none were found to suffer from uric acid overproduction symptoms, mental retardation, ataxia, hypotonia, or areflexia. Two patients were reported to have distal sensory loss alongside peripheral motor neuropathy.

Table 2.

List of all patients with CMTX5 reported in the literature.

| Symptoms |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological |

Hematolo-immunological |

Other |

|||||||||||||||

| Patient ID* | Nucleotide change in PRPS1 | Amino acid change | Syndrome | Ancestry | Gender | Delayed motor development | Loss of DTR | Hearing impairment | Optic atrophy | Recurrent infections | Anemia | Enzyme activity (nmol/h/mg protein) |

Uric acid (μmol/L in serum; mmol/24 h in urine) | Purine and pyrimidine levels in blood and/or urine (mmol/mol creatine); nucleotide levels in erythrocytes (pmol/mg protein) | Brain MRI | Patient ID in the cited article, reference | |

| ID 9 | c.334G > C | p.Val112Leu | CMTX5 | NR | M | - (normal until 3 y) | + | + | − | + | + | VEP, BAEP, SNAPs not evocable, MCVs slow, pes cavi, muscle weakness and atrophy | E: −5.82 ± 1.98 | NR | NR | NR | [21] |

| ID 10 | c.82G > C | p.Gly28Arg | CMTX5 | Japanese | M | + | - (reduced) | + | + | NR | − | Low visual acuity, pes cavus, hypesthesia, high CK, muscle weakness and atrophy | E: 7.4 | Normal (serum) | NR | Normal | [22] |

| ID 11 | c.362C > G | p.Ala121Gly | CMTX5 | NR | M | + | + | + | − | NR | NR | Muscle weakness and atrophy, high CK, MCV slow, SNAPs not evocable | NR | Normal (serum) | NR | NR | [23] |

| ID 12 | c.319A > G | p.Ile107Val | CMTX5 | Japanese | M | − | - (reduced) | + | − | NR | NR | Musle weakness | NR | Normal (serum) | NR | Normal | [24] |

| ID 13 | c.319A > G | p.Ile107Val | CMTX5 | Japanese | M | − | - (reduced) | + | − | NR | NR | Musle weakness | NR | Normal (serum) | NR | Normal | [24] |

| ID 14 | c.202A > T | p.Met68Leu | CMTX5 | French | M | NR | NR | + | + | − | NR | BAEP not evocable | NR | NR | NR | NR | [25] |

| ID 15 | c.344C > T | p.Met115Thr | CMTX5 | Korean | M | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | Distal sensory loss | F: estimated 30–60% decrease compared to controls | Normal (serum) | NR | NR | III-18 [26] |

| ID 16 | c.344C > T | p.Met115Thr | CMTX5 | Korean | M | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | III-21 [26] | |

| ID 17 | c.344C > T | p.Met115Thr | CMTX5 | Korean | M | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | III-24 [26] | |

| ID 18 | c.344C > T | p.Met115Thr | CMTX5 | Korean | M | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | F: estimated 30–60% decrease compared to controls | Normal (serum) | NR | NR | IV-1 [26] | |

| ID 19 | c.344C > T | p.Met115Thr | CMTX5 | Korean | M | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | F: estimated 30–60% decrease compared to controls | Normal (serum) | NR | NR | IV-11 [26] | |

| ID 20 | c.129A > C | p.Glu43Asp | CMTX5 | Unknown (European) | M | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | Distal sensory loss | NR | Normal (serum) | NR | NR | III-11 [26] |

| ID 21 | c.129A > C | p.Glu43Asp | CMTX5 | Unknown (European) | M | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | Normal (serum) | NR | NR | III-13 [26] | |

| ID 22 | c.129A > C | p.Glu43Asp | CMTX5 | Unknown (European) | M | NR | NR | + | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | IV-14 [26] | |

| Proportion of patients with symptom | 2/5 = 40% | 2/5 = 40% | 14/14 = 100% | 9/14 = 64% | 1/2 = 50% | 1/2 = 50% | |||||||||||

Lastly, we presented intermediate phenotypes between different PRPS1-related disorders (Table 3). Three of the patients were assessed to have a novel phenotype, not matching any of the PRS-I deficiency syndromes. Of these, one had an intermediate phenotype of PRS-I super-activity/Arts syndrome and two, including our patient with an intermediate phenotype of CMTX5/Arts syndrome. The patient with PS/Arts syndrome had high uric acid values but did not suffer from gout or kidney stones. The two patients with CMTX5/Arts syndrome had all the neurological symptoms typical for Arts syndrome, but with a less severe clinical course. The three patients with novel phenotypes had intrauterine growth restriction, were found to be spastic and all suffered from Leber's congenital amaurosis. Two of them (siblings) also developed diabetes insipidus. The three patients with features of Arts syndrome suffered from recurrent infections. The data showed there is a significant number of patients with intermediate phenotypes caused by PRPS1 variants, further indicating the importance of considering PRS-I disorders as a spectrum as previously suggested by authors.

Table 3.

List of all patients with intermediate phenotypes of PRS-I deficiency reported in the literature [27].

Abbreviations: NR – not reported, UO – symptoms of uric acid overproduction, “+” – symptom was present, “-“– symptom was not present, PS – PRS-I super-activity, CMTX5 – Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 5, E – erythrocytes, F – fibroblasts, DTR – deep tendon reflexes, IUGR – intrauterine growth restriction, CK – creatine kinase, y – years, VEP – visual evoked potentials, BAEP – brainstem auditory evoked potentials, SNAP – sensory nerve action potential, MCV – motor conduction velocities.

⁎ Patients ID 1–3 are from the same family, patients ID 4 and 5 are siblings, patients ID 12 and 13 are siblings, patients ID 15–19 are from the same family, patients ID 20–22 are from the same family, patients ID 25 and 26 are siblings.

⁎⁎ mmol/L (was not calculated per unit of creatine).

4. Discussion

We presented a Slovenian patient with PRS-I enzyme deficiency due to a novel pathogenic variant – NM_002764.4:c.424G > A (p.Val142Ile) in the PRPS1 gene. He suffered from gross motor impairment, severe sensorineural deafness, balance issues, ataxia, and frequent respiratory infections. In addition, we report the findings of a systemic literature review of all described male cases of Arts syndrome and CMTX5 as well as intermediate phenotypes.

It was difficult to ascertain our patient's specific diagnosis within the PRS-I deficiency spectrum as there are few resources on PRS-I deficiency and as some clinical features develop over time. His clinical presentation included features attributed to Arts syndrome (mental retardation, ataxia, frequent respiratory infections) as well as features found in CMTX5 (prelingual sensorineural deafness and peripheral motor neuropathy) [2,4]. We also had to consider that neurological symptoms are a common feature in early onset PRS-I super-activity as well as deficiency syndromes [17]. Although molecular modeling predicted that the site affected in our patient can lead to loss-of-function as well as gain-of-function of PRS-I [17], enzyme analyses confirmed our patient had PRS-I deficiency. In considering all aspects of his clinical presentation, we propose our patient had an intermediate phenotype of CMTX5 and Arts syndrome.

Genetic analysis confirmed a novel variant in our patient, however, in reviewing the literature we found a patient with a similar variant on the same amino acid (c.424C > G, p.Val142Ile) had already been described previously by Moran et al. and linked to an intermediate phenotype of PRS-I super-activity/Arts syndrome (see Table 3, patient ID 28) [17]. The patient presented with uric acid overproduction without gout, developmental delay, hypotonia, hearing loss, and recurrent respiratory infections, the latter ultimately led to respiratory failure and death at 27 months. His serum uric acid was higher than in our patient and required allopurinol therapy. Enzyme analysis revealed PRS-I activity was low in erythrocytes and normal in fibroblasts. Contrary to our patient, analyses of enzyme activity at different phosphate concentrations revealed erroneous phosphate regulation, which indicates the enzyme is constitutively active in fibroblasts [17]. Molecular modeling has predicted that a change in this amino acid can lead to both PRS-I super-activity and deficiency. The p.Val142Ile substitution is said to interact with allosteric sites I and II as well as with the ATP-binding site [9,17].

Oral SAM supplementation in the diet replenishes purine nucleotides independent of PRPP production [2] and along with nicotinamide alleviates some of the symptoms of Arts syndrome [8]. Reports in the literature suggest that co-therapy of SAM and nicotinamide stabilizes the progression of symptoms such as ataxia and hearing loss as well as decreases the number of hospitalizations and the need for ventilatory support [2,4,5,8,9]. Our patient has been receiving the treatment for approximately two years at the time of this report. His motor function seems to have improved (less difficulty walking, fewer falls), however, it still deteriorates after he overcomes an infection and seems to be deteriorating over time regardless of treatment. There seemed to be no change in his other symptoms.

Our literature review showed that all patients with Arts syndrome present with ataxia, hypotonia, loss of deep tendon reflexes, recurrent infections, and mental retardation. Hearing impairment and optic atrophy are present in over half the cases reported in the literature. Patients with CMTX5 all had hearing loss and over half presented with optic atrophy as well as delayed motor development and loss of deep tendon reflexes. Intermediate phenotypes may lead to a clinical presentation combining symptoms of each disorder; however, it may also lead to symptoms previously not associated with PRS-I deficiency at all (e.g. Leber's congenital amaurosis, diabetes insipidus).

In conclusion, we propose the patients with PRS-I deficiency could be viewed as a phenotypic continuum rather than three separate syndromes, as suggested by previous reports [2,4,9,20,24,28,29] and ours. To date, there are 8 reports of Arts syndrome and 14 reports of CMTX5, not including affected females. With genetic testing becoming more accessible it is easier to recognize patients with intermediate phenotypes, whose clinical presentations may not match one of the syndromes clearly enough to make a diagnosis based on clinical features alone. More research and data are needed to improve the therapeutic approaches and outcomes of these patients.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study and this paper were approved by the Scientific Committee of the Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolic Diseases, University Children's Hospital, University Medical Centre Ljubljana. Informed consent has been obtained from patient's parents/caregivers to perform this study, and to publish the results from genetic studies in an anonymized form.

Acknowledgements and funding information

This work and the article processing charge were supported by the Slovenian National Research Agency (grant number P3–0343). The funding organization had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Katarina Štajer: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Neja Kovač: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Jaka Šikonja: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Matej Mlinarič: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Sara Bertok: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Jernej Brecelj: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Maruša Debeljak: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Jernej Kovač: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Gašper Markelj: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. David Neubauer: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Rina Rus: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Mojca Žerjav Tanšek: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Ana Drole Torkar: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Aleksandra Zver: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Tadej Battelino: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Rosa Jiménez Torres: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Urh Grošelj: Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Katarina Štajer, Email: katarina.stajer@kclj.si.

Neja Kovač, Email: neja.kovac@mf.uni-lj.si.

Jaka Šikonja, Email: jaka.sikonja@mf.uni-lj.si.

Matej Mlinarič, Email: matej.mlinaric@kclj.si.

Sara Bertok, Email: sara.bertok@kclj.si.

Jernej Brecelj, Email: jernej.brecelj@kclj.si.

Maruša Debeljak, Email: marusa.debeljak@kclj.si.

Jernej Kovač, Email: jernej.kovac@kclj.si.

Gašper Markelj, Email: gasper.markelj@kclj.si.

David Neubauer, Email: david.neubauer@mf.uni-lj.si.

Rina Rus, Email: rina.rus@kclj.si.

Mojca Žerjav Tanšek, Email: mojca.tansek@kclj.si.

Ana Drole Torkar, Email: ana.droletorkar@kclj.si.

Aleksandra Zver, Email: aleksandra.zver@kclj.si.

Tadej Battelino, Email: tadej.battelino@mf.uni-lj.si.

Rosa Jiménez Torres, Email: rosa.torres@salud.madrid.org.

Urh Grošelj, Email: urh.groselj@kclj.si.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Almoguera B., et al. Expanding the phenotype of PRPS1 syndromes in females: neuropathy, hearing loss and retinopathy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014;9(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0190-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Brouwer A.P.M., van Bokhoven H., Nabuurs S.B., Arts W.F., Christodoulou J., Duley J. PRPS1 mutations: four distinct syndromes and potential treatment. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86(4):506–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiorentino A., et al. Missense variants in the X-linked gene PRPS1 cause retinal degeneration in females. Hum. Mutat. 2018;39(1):80–91. doi: 10.1002/humu.23349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittal R., et al. Association of PRPS1 mutations with disease phenotypes. Dis. Markers. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/127013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercati O., et al. PRPS1 loss-of-function variants, from isolated hearing loss to severe congenital encephalopathy: New cases and literature review. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2020;63(11) doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2020.104033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang B.-Y., Yu H.-X., Min J., Song X.-X. A novel mutation in gene of PRPS1 in a young Chinese woman with X-linked gout: a case report and review of the literature. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020;39(3):949–956. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04801-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arts W.F.M., Loonen M.C.B., Sengers R.C.A., Slooff J.L. X-linked ataxia, weakness, deafness, and loss of vision in early childhood with a fatal course. Ann. Neurol. 1993;33(5):535–539. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenherr N., et al. Co-therapy with S-adenosylmethionine and nicotinamide riboside improves t-cell survival and function in Arts Syndrome (PRPS1 deficiency) Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021;26 doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2021.100709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X.Z., Xie D., Yuan H.J., de Brouwer A.P.M., Christodoulou J., Yan D. Hearing loss and PRPS1 mutations: Wide spectrum of phenotypes and potential therapy. Int. J. Audiol. 2013;52(1):23–28. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.736032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riley D.S., et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017;89:218–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kircher M., Witten D.M., Jain P., O’Roak B.J., Cooper G.M., Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014;46(3):310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng P.C. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong C., et al. Comparison and integration of deleteriousness prediction methods for nonsynonymous SNVs in whole exome sequencing studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24(8):2125–2137. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adzhubei I.A., et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres R.J., Mateos F.A., Puig J.G., Becker M.A. Determination of phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase activity in human cells by a non-isotopic, one step method. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1996;245(1):105–112. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(95)06178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres R.J., BeckerC M.A. A simplified method for the determination of phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase activity in hemolysates. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1994;224:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran R., et al. Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase superactivity and recurrent infections is caused by a p.Val142Leu mutation in PRS-I. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2012;158A(2):455–460. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Brouwer A.P.M., et al. Arts Syndrome Is Caused by Loss-of-Function Mutations in PRPS1. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81(3):507–518. doi: 10.1086/520706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maruyama K., et al. Arts syndrome with a novel missense mutation in the PRPS1 gene: A case report. Brain Dev. 2016;38(10):954–958. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puusepp S., et al. Atypical presentation of Arts syndrome due to a novel hemizygous loss-of-function variant in the PRPS1 gene. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2020;25 doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2020.100677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng L., Wang K., Lv H., Wang Z., Zhang W., Yuan Y. A novel mutation in PRPS1 causes X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease-5. Neuropathology. 2019;39(5):342–347. doi: 10.1111/neup.12589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirakawa S., et al. A Novel PRPS1 Mutation in a Japanese Patient with CMTX5. Intern. Med. 2022;61(11):1749–1751. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.8029-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J., et al. Exome Sequencing Reveals a Novel PRPS1 Mutation in a Family with CMTX5 without Optic Atrophy. J. Clin. Neurol. 2013;9(4):283. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2013.9.4.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishikura N., et al. X-linked Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 5 with recurrent weakness after febrile illness. Brain Dev. 2019;41(2):201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lerat J., et al. New PRPS1 variant p.(Met68Leu) located in the dimerization area identified in a French CMTX5 patient. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2019;7(9) doi: 10.1002/mgg3.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim H.-J., et al. Mutations in PRPS1, Which Encodes the Phosphoribosyl Pyrophosphate Synthetase Enzyme Critical for Nucleotide Biosynthesis, Cause Hereditary Peripheral Neuropathy with Hearing Loss and Optic Neuropathy (CMTX5) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81(3):552–558. doi: 10.1086/519529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Maawali A., et al. Prenatal growth restriction, retinal dystrophy, diabetes insipidus and white matter disease: expanding the spectrum of PRPS1-related disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;23(3):310–316. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Synofzik M., et al. X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Arts syndrome, and prelingual non-syndromic deafness form a disease continuum: evidence from a family with a novel PRPS1 mutation. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014;9(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robusto M., et al. The expanding spectrum of PRPS1-associated phenotypes: three novel mutations segregating with X-linked hearing loss and mild peripheral neuropathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;23(6):766–773. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.