Abstract

We report a detailed study into the method of precatalyst activation during alkyne cyclotrimerization. During these studies we have prepared a homologous series of Fe(III)-μ-oxo(salen) complexes and use a range of techniques including UV–vis, reaction monitoring studies, single crystal X-ray diffraction, NMR spectroscopy, and LIFDI mass spectrometry to provide experimental evidence for the nature of the on-cycle iron catalyst. These data infer the likelihood of ligand reduction, generating an iron(salan)-boryl complex as a key on-cycle intermediate. We use DFT studies to interrogate spin states, connecting this to experimentally identified diamagnetic and paramagnetic species. The extreme conformational flexibility of the salan system appears connected to challenges associated with crystallization of likely on-cycle species.

Keywords: iron, cyclotrimerization, mechanism, salen, ligand reduction

1. Introduction

Our precious-metal supply is rapidly diminishing, and abundant alternatives are needed to replace them, particularly in catalysis. For many researchers across the world, iron is an attractive target to this end, owing to its low toxicity and natural abundance.1−5 Catalysis mediated by the platinum-group metals is well-understood, and the corresponding mechanisms are often well-elucidated. The same cannot be said for iron.6−9 If iron is to compete with and ultimately replace the precious metals in catalysis, a deeper mechanistic understanding is essential. However, the mechanisms underpinning iron-mediated catalysis can be more complex and thus more challenging to elucidate than for late 4d and 5d metals. This is not least due to the large number of accessible oxidation states and spin states: multistate reactivity is common,10 and paramagnetism can be problematic when using standard characterization techniques such as NMR spectroscopy. This report is an accurate reflection of how challenging mechanistic elucidation of an iron-catalyzed process can be.

In recent years, the scientific community has produced some remarkable progress within iron-mediated catalysis and the associated mechanistic pathways.11−17 Inspired by this, and building on our recent report on an iron-mediated regioselective alkyne trimerization,18 we set out to elucidate the pathway of this transformation in more detail. Our original work in this area was postulated to proceed via a precatalyst activation that involves (i) μ-oxo reduction to form Fe(III)-hydride, (ii) Fe(III)-hydride dimerization leading to facile release of hydrogen gas, and (iii) Fe(II)-salen complex formation and reaction with pinacolborane (HBpin) to form an on-cycle diamagnetic species, A (Scheme 1a).18

Scheme 1. (a) Previous Work and (b) Literature Examples of Fe-Boryl Species.

Not only have catalytic reactions involving HBpin been expanded upon beyond alkene hydroboration in the past two years (e.g., reductions,19−22 direct borylations,23,24 and chain-walking transformations25 to name but a few) but also metal boryl species have become increasingly prevalent in the literature, particularly as intermediates in metal-mediated hydroboration reactions.26−28 Notably, coordinatively unsaturated Fe-boryl complexes have frequently been implemented as potential intermediates in catalytic processes. More recently such species have been isolated and characterized and their insertion into alkynes unequivocally demonstrated (Scheme 1b).29−38 Despite this, the unambiguous assignment of Fe-boryl moieties in catalysis remains a challenging endeavor. Herein we present strong evidence for the implication of a transient Fe-Bpin species in the trimerization of terminal alkynes and propose the use of liquid injection field desorption ionization mass spectrometry (LIFDI-MS) as a powerful tool to characterize such open-shell intermediates.39−41

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Ligand Design

Motivated by a desire to further understand the mechanism by which 2a catalyzes the cyclotrimerization of terminal alkynes and gain insight into the proposed active species A (Scheme 1a), we sought to (i) reinvestigate the nature of the diamagnetic species computationally assigned as A (Scheme 1a) and (ii) expand our library of Fe-salen precursors to give deeper mechanistic understanding (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Precatalysts Synthesized in This Work.

A diamagnetic species, assigned as A in previous work,18 is observed during catalysis. Through extended reaction monitoring studies it was shown to persist after the standard reaction time. We initiated our study into this species by reacting complex 2a with HBpin (4 equiv) for 3 days. This generates the reassigned diamagnetic compound (herein referred to as 3a) cleanly. Isolation and implementation in catalysis show that this species is in fact not catalytically active; this is unsurprising given its persistence in catalysis. Although the exact structure of 3a has not been unequivocally assigned, it is clear the imine moieties in the salen framework are reduced over the course of the stoichiometric reaction to form a salan species (see section 7.5 in the Supporting Information for detailed studies into speciation using a range of boranes across the homologous series 2, along with likely structure of 3a).

This in turn prompted us to reevaluate our original DFT-based hypothesis. Species A was further inspected computationally. A lower energy isomer of A with a shorter Fe–O bond of 2.1 Å vs 2.5 Å and an altered η2-interaction between the salen C–N double bond with iron in the original structure was found (see section 12.3 in the Supporting Information for an overlay of the structures). The Gibbs energy stabilization of A-1(42) over A as a diamagnetic species is predicted to be 2.9 kcal/mol using PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP and 8.6 kcal/mol using a wave function method, namely DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS(T,Q).

In the original identification of A, we had evaluated different hybrid density functionals in single-point calculations to confirm that it is a low-spin species. We now wanted to reference against a higher level of theory, DLPNO–CCSD(T) (see Computational Methods in the Supporting Information). This showed that A is in fact a high-spin species, with the singlet 1A-1 and triplet 3A-1 configurations destabilized by ΔG = 21.2 and 20.9 kcal/mol, respectively, using DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS(T,Q). A more detailed comparison is provided in section 12.3 in the Supporting Information.

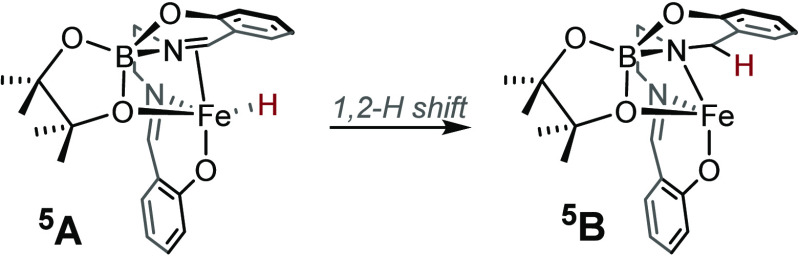

Upon re-evaluating the geometry of 5A-1 as a high-spin species, we found that it can transform via a 1,2-hydrogen shift to form 5B (Scheme 3). The reaction is exergonic with a Gibbs energy of −33.1 kcal/mol using DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS(T,Q). This computational observation made us question whether salen ligand reduction is taking place in the presence of HBpin, which might imply that A and A-1 may be high-spin species formed transiently during the induction period. Whether the catalytically competent species has a partial or fully reduced salen backbone needed to be evaluated experimentally.

Scheme 3. Transformation of Species 5A-1 into 5B via a 1,2-Hydrogen Shift Reaction.

We hypothesized that through ligand modification (varying steric, flexibility, and electronic properties) we might gain further insight into the active species and mechanism of cyclotrimerization. We synthesized a range of modified salen ligands (see Scheme 2). The corresponding iron complexes (2a–2d′) were obtained by reaction of the proligand with Fe(OAc)2 in a 1:1 mixture in ethanol. Complexes 2a–2f were characterized by 1H NMR, LIFDI-MS, and IR spectroscopy (see the Supporting Information for full details).43

Computational studies on the monometallic FeII salen congeners of 2a–2d and 2a′–2d′ allow us to quantify the structural flexibility of the iron coordination sphere. For 2a-mono, 2a′-mono, 2d-mono, and 2d′-mono, a distorted-square-planar iron environment is found (τ4′ = 0.24 (0.23) for 2a-mono (2a′-mono) and τ4′ = 0.18 (0.18) for 2d-mono (2d′-mono), where τ4′ = 0 for square-planar and τ4′ = 1 for tetrahedral geometries).44 In contrast, with the propyl and butyl backbones the coordination spheres are closer to a tetrahedral environment (τ4′ = 0.69 (0.67) for 2b-mono (2b′-mono) and τ4′ = 0.65 (0.64) for 2c-mono (2c′-mono)). In all cases, the iron ion is found in its high-spin state, with the intermediate- and low-spin states less stabilized by at least 7 and 41 kcal/mol using PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP single-point calculations (see section 12.4 in the Supporting Information). That this level of theory is appropriate was confirmed with DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS(T,Q) calculations (see section 12.2 in the Supporting Information).

In the case of 2b and 2b′ only a minor quantity of crystalline material suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis could be obtained, and this indicated the formation of analogous Fe(III) acetate complexes (Fe(1b)·OAc and Fe(1b′)·OAc) rather than the expected μ-oxo Fe(III) dimer.45 We cannot unambiguously speak to the bulk purity of 2b and 2b′: Fe(1b)·OAc and 2b are indistinguishable by elemental analysis, while ESI-MS invariably corresponds to the [Fe(salen)]+ molecular ion in both cases. However, only the higher-order complex [Fe2(1b)3] is identified in the LIFDI-MS and by IR spectroscopy, indicating that Fe(1b)·OAc is likely to be a minor species. In contrast, for the bulkier ligand 1b′, complex 2b′ was not detected by LIFDI-MS; rather, Fe(1b′)·OAc is detected as the major species (vide infra). Complex Fe(1b′)·OAc has been included in further studies because we envisage the mode of action to be analogous to that of other iron(III)-μ-oxo complexes in the series (see the Supporting Information for the anticipated method of catalyst activation). Despite some previously conflicting reports, the μ-oxo Fe(III) dimer was readily identified as the major species by LIFDI-MS for all other complexes 2a–2d′, and no other Fe(III)·OAc species could be identified.46,47 These data highlight a key advantage of LIFDI-MS over ESI-MS, which has been noted previously.48

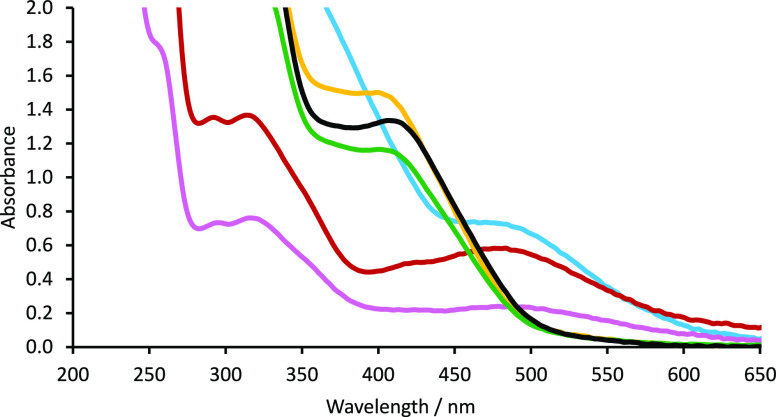

We initially measured the UV–vis spectrum of precatalysts 2 in order to compare any significant differences in Lewis acidity about the Fe(III) center (Figure 1). In particular, the LMCT band (∼400–500 nm) from the in-plane pπ orbital of the phenolate ring to the half-filled dπ* orbital of Fe(III) has been used to give an indication of Lewis acidity at the iron center.49−51 In our case, we observed only small changes in Lewis acidity upon incorporation of an additional methylene unit into the backbone (compare. 2a → 2c and 2a′ → 2c′). As expected, furnishing the ligand with electron-donating tert-butyl substituents greatly increases the Lewis acidity at Fe(III) and substituting the ethylene backbone for a phenyl moiety results in a significantly less Lewis acidic metal center (see section 4 in the Supporting Information for full details). Surprisingly, functionalization of the phenyl backbone (i.e., 2e and 2f) results in very subtle electronic changes at the Fe(III) center.

Figure 1.

UV–vis spectra of selected precatalysts of the form 2: (blue line) 2a; (red line) 2b; (pink line) 2c; (yellow line) 2d; (green line) 2e; (black line) 2f.

In addition to expanding our library of Fe precursors we also extended our catalyst activator to include catecholborane (HBcat) and 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (9-BBN) as well as HBpin to further understand the role of the coreductant.

2.2. Reaction Profile Studies

Pleasingly, early benchmarking studies showed that all our Fe precursors 2a–2d′ are catalytically competent in the cyclotrimerization of phenylacetylene. As we previously reported, the catalysis is associated with an induction period (20–120 min) in which the active catalyst is generated (vide infra). Notably, replacing HBpin with HBcat or 9-BBN completely shuts down catalytic activity and we only see inactive species of the form 3. This is in line with our previous study and ultimately leads us to the same inference—HBpin is intimately involved in generating the active catalyst.

MeCN is the most effective cyclotrimerization solvent, although THF gives a comparable catalytic turnover. The kinetic profile of phenylacetylene cyclotrimerization by each precatalyst in CD3CN is summarized in Figure 2 and clearly indicates a significant change in both the induction period and the rate of catalysis.

Figure 2.

Reaction profiles showing uptake of phenylacetylene using complexes 2a (blue ◆), 2b (red ▲), 2c (pink ●), 2d (yellow ◆), 2a′ (blue ◇), 2b′ (red △), 2c′ (pink ○), 2d′ (yellow ◇), 2e (green ×), and 2f (black ×).

Generally, the length of the induction period follows a rational trend based on the steric profile of the ligands. In all cases, 2 proceeds with a shorter induction period when compared to its tert-butyl-functionalized analogue 2′ (Table 1). This is readily rationalized, as the activation of the precatalysts (and approach of HBpin) is perturbed by the additional tBu appendages. Expanding the ligand backbone to add “structural flexibility” (in the order 2c′ > 2b′ > 2a′ > 2d′) generally results in a reduction in induction period (in the order 2c′ > 2b′ > 2a′ > 2d′).

Table 1. Summary of Rate Data for the Range of Precatalystsa.

| complex | induction time (min) | rate (10–2 mol L–1 s–1) | time to completion (min)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 35 | 1.11 | 91 |

| 2b | 38 | 0.53 | 129 |

| 2c | 22 | 0.96 | 88 |

| 2d | 60 | 0.22 | 264 |

| 2e | 22 | 0.50 | 147 |

| 2f | 40 | 1.70 | 97 |

| 2a′ | 70 | 0.30 | 241 |

| 2b′ | 46 | 1.07 | 68 |

| 2c′ | 35 | 1.39 | 108 |

| 2d′ | 100–120 | 0.03 | ≫300c |

Conditions: precatalysts 2 (1 mol %), phenylacetylene (0.25 mmol), HBpin (0.10 mmol), RT, CD3CN (600 μL). Spectroscopic consumption of phenylacetylene measured by 1H NMR spectroscopy against 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene.

Time point where [SM] < 2.5%.

[SM] plateau.

Based on our initial hypothesis we expected to see a clear trend in induction period (or even catalytic competency) reflected in the flexibility of the ligand backbone. However, the rates of reaction following catalytic induction show no obvious trends. In the case of the tert-butylated series (2′) the rate increases in the order 2c′ > 2b′ > 2a′ > 2d′, which corresponds well with the addition of flexibility in the ligand backbone. However, this trend does not hold up in the absence of tert-butyl groups, where we see a rate of the order 2a > 2c > 2b > 2d. Clearly the data cannot be explained simply through ligand backbone flexibility.

It is worth noting that the final ratio of 1,2,4-triphenylbenzene to 1,3,5-triphenylbenzene products, tested across this diverse range of precatalysts, is almost identical (98% 1,2,4- to 2% 1,3,5-product). This indicates that ligand modification has little effect on the regioselectivity (vide infra).

Precatalysts 2e and 2f have been included for completeness, but 2e suffered from very poor solubility in the reaction solvent. As such the induction period and rate of reaction of 2e cannot be accurately compared to the rest of the series. The rapid rate demonstrated by 2f is noteworthy and counterintuitive, especially in comparison with 2d and 2e. We have undertaken homogeneity tests52 using both PMe3 and Hg with 2a and 2f, and the results of these support a homogeneous reaction (see section 5.3 in the Supporting Information).

2.3. Stoichiometric Studies

In order to revisit the mechanism of alkyne cyclotrimerization and gain further insight into catalyst activation, an extensive range of stoichiometric reactions and LIFDI mass spectrometry studies were undertaken. The necessity for coordinating solvents in catalysis was elucidated by reacting complexes 2a–2d′ with 10 equiv of HBpin in both CD3CN and C6D6. These reactions were monitored periodically by 1H, 11B, and, where appropriate, 19F NMR spectroscopy over 48 h (see the Supporting Information). In all cases the spectra were associated with the rapid generation of O(Bpin)2 (BOB, 11B NMR = 21 ppm), presumably forming [(FeIIIsalen)H] as per our originally hypothesized catalyst activation process (vide supra). As reported previously, the reaction of precatalyst 2a with HBpin generates a diamagnetic complex as the major species in CD3CN (3a) after 1 h at RT, i.e. after the induction period for 2a. However, we can now confirm that in most cases the reaction of precatalysts 2 and HBpin also result in broad paramagnetic signals in the 1H NMR spectra that elude meaningful characterization (see section 7 in the Supporting Information). This likely indicates that on-cycle catalysis is dominated by paramagnetic intermediates (in keeping with our DFT studies). The only other exceptions are those of 2e and 2f; upon treatment with HBpin in C6D6 well-defined diamagnetic species (3e and 3f) form with BOB as the only isolable byproduct (see section 7 in the Supporting Information).

The onward catalyst activation (via a hypothesized backbone reduction) was confirmed by the formation and crystallographic characterization of complex 4a by the intentional reaction of 3a with water under inert conditions. The ligand reduction is stepwise, as evidenced by the serendipitous crystallizations of various intermediates, across a range of pro-ligands, along this pathway (4a–d, Figure 3). We believe the oxygen in complexes 4a–c are the result of crystallographic trapping of intermediates (at various stages of reduction).53

Figure 3.

Molecular structure representation (30% ellipsoids) of compounds 4a–4d. 4a (CCDC 2260432): hydrogen atoms, except for those which are nitrogen-bound, have been omitted for clarity. 4b (CCDC 2260433): hydrogen atoms, except for those which are nitrogen-bound, have been omitted for clarity. The minor disordered component has also been omitted and tert-butyl groups are represented in wireframe mode, also for visual ease. Symmetry operations: (1) 1 – x, 1 – y, 1 – z. 4c (CCDC 2260599): solvent, hydrogen atoms (except for those which are nitrogen-bound), and the minor disordered components have been omitted for clarity. Symmetry operations: (1) 1 – x, y, 1/2 – z. 4d (CCDC 2260434): the minor disordered components and hydrogen atoms (except for H1) have been omitted for clarity. Symmetry operations: (1) 1 – x, y, 1/2 – z.

Complex 4a, which contains ligand 1a, shows complete reduction of the iminyl moieties of the salen ligand to yield a dimeric iron species, in which each of the Fe(III) centers bears a salan ligand and the two iron centers are bridged by OBpin units. Complex 4b shows a similar structure in which two Fe(III) centers are bridged by two OBpin units but the parent ligand (1d) has only undergone partial reduction. Thus, a salalen ligand system is present whereby the proligand contains one imine (at N2/N21) and one amine fragment (at N1/N11). 4c is a mixed Fe(II)/Fe(III) complex consisting of four iron centers ligated by salalen ligands (from 1e) with a central oxo ion. Finally, 4d is a mixed salen-salan-salen trimeric species derived from proligand 1e.

We emphasize our observation that ligated salen can be reduced in situ by a simple reductant like HBpin has important implications for the catalysis presented here and beyond because (i) formation of an active Fe-salan complex could indicate that catalyst activation and active cyclotrimerization catalysis involves some element of ligand reduction and (ii) salen ligands are commonly regarded as being synthetically robust and somewhat inert; our study herein indicates otherwise.54−57

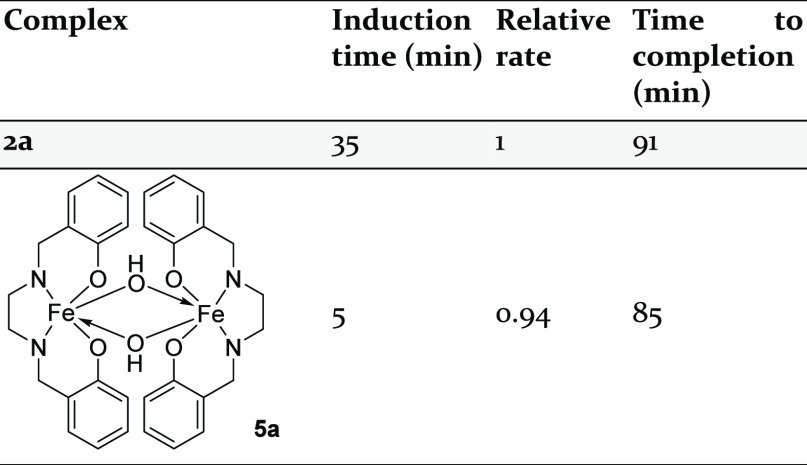

We hypothesized that this in situ ligand reduction may be responsible for the observed induction period associated with our cyclotrimerization catalysis. However, 3a is an end point of catalysis and cannot mediate cyclotrimerization. Therefore, we targeted an appropriate [FeIII(salan)] precursor, [Fe(Hsalan)(OH)]2 (5, Table 2), which has previously been reported.58

Table 2. Comparison of Induction Period and Rate of Reaction (2a versus 5a)a.

Conditions: complex 2a or 5a (1 mol %), tert-butylphenylacetylene (0.25 mmol), HBpin (0.10 mmol), RT, CD3CN (500 μL). Spectroscopic consumption of tert-butylphenylacetylene measured by 1H NMR spectroscopy against 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene.

Complex 5 shows catalytic competence in the cyclotrimerization of 4-tert-butylphenylacetylene. Catalysis with 5 proceeds with a significantly reduced induction period compared to 2a (5 min with 5 compared to 35 min with 2a, Figure 4), indicating that reduction of salen to salan is partially responsible for the induction periods observed in cyclotrimerization with precatalysts 2. The rate of catalysis with 5a is almost identical to that using 2a, adding more weight to the argument that a salan-type ligand is key during active catalysis. Mirroring precatalysts 2, the combination of 5 and HBpin is vitally important in mediating cyclotrimerization; complex 5 is not catalytically competent alone (nor is catalysis mediated by an in situ generated [FeII(salan)] species; see the Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Reaction profile of cyclotrimerization of tert-butylphenylacetylene mediated by complexes 2a (blue ◆), 5 (black ◇), and 3a (yellow □).

2.4. LIFDI-MS Studies

Identification of the exact nature of the active species still proved elusive and any signals detected by NMR spectroscopy were very broad, spanning tens of ppm range, possibly indicating a high-spin Fe(III) system, reinforcing our DFT calculations. ESI-MS is not helpful and only shows the [Fe(salen)]+ or [Fe(salan)]+ molecular ion. We therefore turned our attention to mass spectrometry to identify catalyst speciation and possible deactivation pathways.59−63 For this purpose we employed LIFDI-MS, which is the softest ionization for mass spectrometry and has been used to detect highly sensitive and otherwise elusive organometallic species.64,65

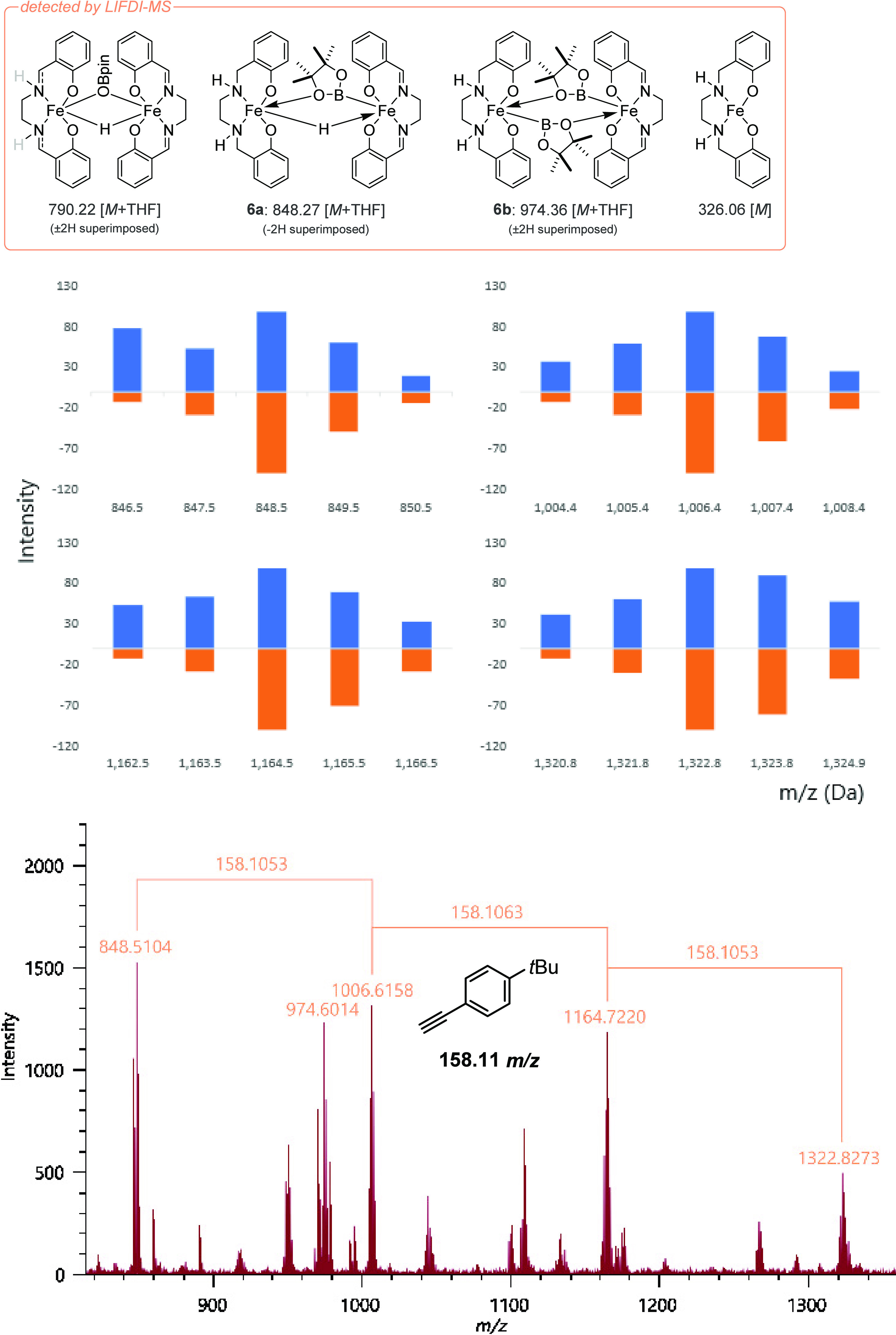

Our LIFDI-MS analysis targeted the detection of the intermediates associated with the reaction of 2a with HBpin. The reaction was initially followed stoichiometrically with periodic LIFDI-MS measurements, facilitating detection of 6a as well as the partial reduction of the salen backbone. After 45 min a signal at 848 m/z was observed which corresponds to [Fe(salen)H][Fe(salan)Bpin]·THF (6a·THF)66 and is congruent with the timeframe of catalyst induction (Figure 5). We assign this as the mixed salen/salan species rather than a [Fe(salalen)H][Fe(salalen)Bpin]·THF species (i) because of the superimposing rate data obtained using 5a and 2a and (ii) the fact that the Fe-hydride fragment can easily re-enter the catalyst activation process, eventually forming Fe(II)salen (see the Supporting Information), which can be further reduced to access the catalytic cycle. As expected, based on lack of cyclotrimerization catalysis, no analogous LIFDI-MS complexes are observed for the reaction of 2a with HBcat or 9-BBN.

Figure 5.

Selection of key species identified by LIFDI-MS and in situ LIFDI-MS of a catalytic run (top) along with predicted (blue) versus experimental (orange) isotope splitting patterns for species observed with m/z 848, 1006, 1164, 1322 Da (middle) and a full spectrum indicating trimerization observed in situ (bottom).

Following this, we studied the catalytic cyclotrimerization of 4-tert-butylphenylacetylene with a 5 mol % catalyst loading of 2a using periodic LIFDI-MS measurements. 4-tert-Butylphenylacetylene undergoes cyclotrimerization in 20 h, compared to only 1 h with phenylacetylene, providing a more protracted time frame for reaction monitoring.

After 1 h the signal at m/z 848 was identified alongside signals corresponding to the insertion of 4-tert-butylphenylacetylene (m/z +152) (see Scheme 3). Thus we can infer that an iron(III) boryl is at least one of the active species in catalysis; the insertion of terminal alkynes into Fe-boryl species has recently been established.34,37,38 Furthermore, the peak at m/z 974 can be satisfactorily modeled as [Fe(salen)Bpin][Fe(salan)Bpin]·THF (6b·THF). We postulate that dimeric species (6a,b) are observed during catalysis due to the high concentrations required when undertaking LIFDI-MS studies; due to the relatively poor sensitivity of LIFDI-MS both the catalytic and stoichiometric reactions were undertaken at more than 4 times the concentration than in the NMR spectroscopy and kinetic experiments (vide supra). This is likely the cause of the discrepancy between the measured order in precatalyst (1/2) when compared to the observation of dimeric species detected by LIFDI-MS. A more detailed summary of iron speciation identified by LIFDI-MS is provided in section 8 in the Supporting Information.

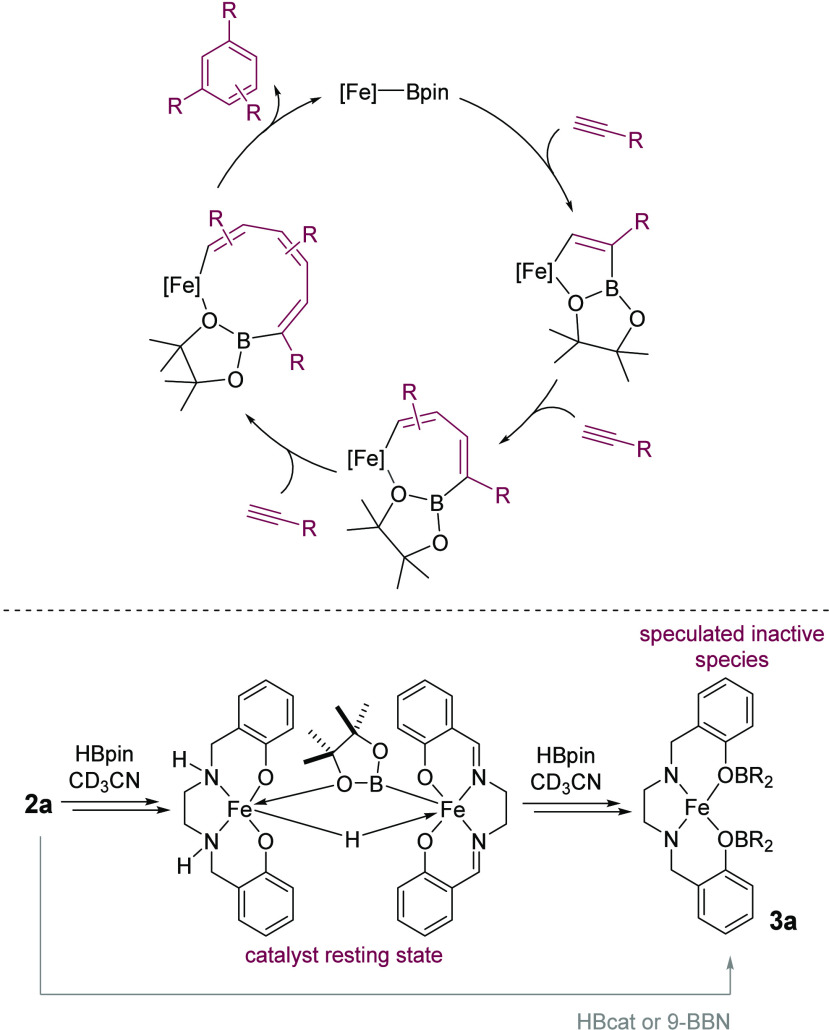

3. Summary and Catalytic Cycle

In this comprehensive synthetic and computational study, we can summarize the findings as follows: (i) paramagnetism dominates catalysis and an iron(III) species is likely responsible for on-cycle catalysis; (ii) DFT studies show that even within our range of salen complexes there is a huge range of conformational flexibility based on the iminyl linker, where the geometry around the iron ranges from distorted square planar to tetrahedral; (iii) reduction of salen to salan further increases the number of accessible conformers, impeding crystallization of likely intermediates or catalyst resting states; (iv) crystallization of catalyst decomposition products invariably shows partial or complete reduction of the ligand from salen to salalen or salan; (v) LIFDI-MS studies give strong evidence, during catalysis, for an iron-boryl species that also contains a salan ligand system; (vi) LIFDI-MS studies show sequential insertion of tert-butylphenylacetylene into a mixed iron(III) dimer that likely contains both salen and salan ligands with iron-hydride and iron-boryl units.

We have attempted a huge range of reactions in our attempts to isolate an iron-boryl complex. That we cannot isolate such a species from stoichiometric reactions from salen, salalen, or salan complexes, even at low temperature, is not surprising given that much of the catalysis, irrespective of ligand design (2a–f, 2a′–d′), is complete within 2–3 h at room temperature. The ease of catalytic cyclotrimerization is further indicated by the fact that we do not see alkene or alkenyl-borane side products being formed.

We therefore postulate a catalytic cycle (Scheme 4) that involves formation of an on-cycle FeIII(salan)Bpin species, insertion of alkyne into the Fe–B bond, which is likely stabilized by the presence of the pinacol oxygen, followed by subsequent insertion of alkyne before cyclization and elimination of the aromatic product. We link the ease of the catalysis to the conformational flexibility of the ligand system and the Bpin ligand: catalysis is not observed with 9-BBN, likely due to the lack of stabilizing oxygen atoms, while the rigidity of HBcat precludes stabilizing coordination. Thus 9-BBN and HBcat lead to the formation of the catalytically inactive species 3, which we tentatively structurally assign as that depicted in Scheme 4.

Scheme 4. Proposed Catalytic Cycle and Overview of the Reactivity of Precatalyst 2a.

4. Conclusion

We have prepared a homologous series of [(salen)Fe]2(μ-O) precursors in which the salen ligand has been modified. The catalytic cyclotrimerization of terminal alkynes mediated by this library of complexes prompted us to reinvestigate the associated mechanistic pathway with additional scrutiny. We have demonstrated that the activation of such precatalysts with HBpin is more complicated than one might expect. Reduction of the iminyl backbone of the assumed-unreactive salen ligand under these mild reductive conditions is of particular note.

Furthermore, we have used LIFDI-MS and interrogated decomposition pathways using NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography to provide strong evidence for a transient iron(III)-boryl active species. Complete untangling of the complex kinetic data presented herein is beyond the scope of this study. We link the lack of crystallographic evidence to the extreme number of conformers available to such a flexible salan system, coupled with the facile nature of the cyclotrimerization catalysis. The extreme flexibility across the series of salan ligands tested may also result in a flexible reaction pocket that is unable to force reactivity away from the formation of the more energetically favored 1,2,4-triphenylbenzene product.

It is clear from this study that the role of the ligand and its potential reactivity, or activation, in order to effect catalysis is an important consideration, the implications of which may be important in the wider field of homogeneous catalysis.

Acknowledgments

The EPSRC (R.L.W., S.L.) and Leverhulme Trust (TMH, MD) are thanked for funding. L.F. thanks the Royal Society of Chemistry for provision of an undergraduate summer studentship. We gratefully acknowledge Professor Ian Fairlamb and Karl Heaton (University of York) for instrument time and assistance with LIFDI-MS measurements. Calculations for this research were conducted on the Lichtenberg high performance computer of the TU Darmstadt.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.3c02898.

Author Contributions

T.M.H., S.L., and M.D. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Plietker B.Iron Catalysis in Organic Chemistry: Reactions and Applications; Wiley-VCH Verlag: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chirik P. J. In Catalysis without Precious Metals; Wiley: 2010; pp 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson V. C.; Solan G. A. In Catalysis without Precious Metals; Wiley: 2010; pp 111–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung J.; Norton J. R. In Catalysis without Precious Metals; Wiley: 2010; pp 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer E. B. In Iron Catalysis II; Bauer E., Ed.; Springer International: 2015; pp 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Junge K.; Schröder K.; Beller M. Homogeneous catalysis using iron complexes: recent developments in selective reductions. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 4849–4859. 10.1039/c0cc05733a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X.; Huang Z. Advances in Base-Metal-Catalyzed Alkene Hydrosilylation. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1227–1243. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obligacion J. V.; Chirik P. J. Earth-abundant transition metal catalysts for alkene hydrosilylation and hydroboration. Nature Reviews Chemistry 2018, 2, 15–34. 10.1038/s41570-018-0001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger O. S. Is Iron the New Ruthenium?. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 6043–6052. 10.1002/chem.201806148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Zhang J.-X.; Sheong F. K.; Lin Z. 1,4-Selective Hydrovinylation of Diene Catalyzed by an Iron Diimine Catalyst: A Computational Case Study on Two-State Reactivity. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 12454–12465. 10.1021/acscatal.0c03535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mako T. L.; Byers J. A. Recent advances in iron-catalysed cross coupling reactions and their mechanistic underpinning. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 766–790. 10.1039/C5QI00295H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo J. C.; Kim D.; Pan C.-M.; Edwards J. T.; Yabe Y.; Gui J.; Qin T.; Gutiérrez S.; Giacoboni J.; Smith M. W.; Holland P. L.; Baran P. S. Fe-Catalyzed C–C Bond Construction from Olefins via Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2484–2503. 10.1021/jacs.6b13155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears J. D.; Neate P. G. N.; Neidig M. L. Intermediates and Mechanism in Iron-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11872–11883. 10.1021/jacs.8b06893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidig M. L.; Carpenter S. H.; Curran D. J.; DeMuth J. C.; Fleischauer V. E.; Iannuzzi T. E.; Neate P. G. N.; Sears J. D.; Wolford N. J. Development and Evolution of Mechanistic Understanding in Iron-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 140–150. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S.; Harden I.; Bistoni G.; Castillo R. G.; Chabbra S.; van Gastel M.; Schnegg A.; Bill E.; Birrell J. A.; Morandi B.; Neese F.; DeBeer S. A Combined Spectroscopic and Computational Study on the Mechanism of Iron-Catalyzed Aminofunctionalization of Olefins Using Hydroxylamine Derived N–O Reagent as the “Amino” Source and “Oxidant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 2637–2656. 10.1021/jacs.1c11083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego D.; Baquero E. A. In Handbook of CH-Functionalization; Wiley: 2022; pp 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi S.; Iron M. A.; Feller M.; Rivada-Wheelaghan O.; Leitus G.; Diskin-Posner Y.; Shimon L. J. W.; Avram L.; Carmieli R.; Wolf S. G.; Cohen-Ofri I.; Sanguramath R. A.; Shenhar R.; Eisen M.; Milstein D. Iron-catalysed ring-opening metathesis polymerization of olefins and mechanistic studies. Nature Catal. 2022, 5, 494–502. 10.1038/s41929-022-00793-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Provis-Evans C. B.; Lau S.; Krewald V.; Webster R. L. Regioselective Alkyne Cyclotrimerization with an In Situ-Generated [Fe(II)H(salen)]·Bpin Catalyst. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 10157–10168. 10.1021/acscatal.0c03068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Wang H.; Du S.; Driess M.; Mo Z. Deoxygenation of Nitrous Oxide and Nitro Compounds Using Bis(N-Heterocyclic Silylene)Amido Iron Complexes as Catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202114598. 10.1002/anie.202114598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam N.; Logdi R.; Sreejyothi P.; Rajendran N. M.; Tiwari A. K.; Mandal S. K. Bicyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene (BICAAC) as a metal-free catalyst for reduction of nitriles to amines. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 3047–3050. 10.1039/D1CC06962D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobylarski M.; Berthet J.-C.; Cantat T. Reductive depolymerization of polyesters and polycarbonates with hydroboranes by using a lanthanum(III) tris(amide) catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 2830–2833. 10.1039/D2CC00184E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostera S.; Weber S.; Blaha I.; Peruzzini M.; Kirchner K.; Gonsalvi L. Base- and Additive-Free Carbon Dioxide Hydroboration to Methoxyboranes Catalyzed by Non-Pincer-Type Mn(I) Complexes. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 5236–5244. 10.1021/acscatal.3c00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.; Jiang S.; Xu X. Yttrium-Catalyzed ortho-Selective C–H Borylation of Pyridines with Pinacolborane. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202117750. 10.1002/anie.202117750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Ye Z.; Zhao W. Cobalt-Catalyzed Asymmetric Remote Borylation of Alkyl Halides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306248. 10.1002/anie.202306248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H.; Zhang W.; Zhou H.; Wei J.; Cai X.; Yang F.; Li W.; Xu C. Remote Site-Selective C(sp3)–H Monodeuteration of Unactivated Alkenes via Chain-Walking Strategy. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 3644–3654. 10.1021/acscatal.3c00559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braunschweig H. Transition Metal Complexes of Boron. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1786–1801. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rami F.; Bächtle F.; Plietker B. Hydroboration of internal alkynes catalyzed by FeH(CO)(NO)(PPh3)2: a case of boron-source controlled regioselectivity. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 1492–1497. 10.1039/C9CY02461A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Yang T.; Sheong F. K.; Lin Z. Beyond the Nucleophilic Role of Metal–Boryl Complexes in Borylation Reactions. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 5061–5068. 10.1021/acscatal.1c00752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. Y.; Moreau B.; Ritter T. Iron-Catalyzed 1,4-Hydroboration of 1,3-Dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12915–12917. 10.1021/ja9048493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Peng D.; Leng X.; Huang Z. Iron-Catalyzed, Atom-Economical, Chemo- and Regioselective Alkene Hydroboration with Pinacolborane. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 125, 3764–3768. 10.1002/ange.201210347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford R. B.; Brenner P. B.; Carter E.; Gallagher T.; Murphy D. M.; Pye D. R. Iron-Catalyzed Borylation of Alkyl, Allyl, and Aryl Halides: Isolation of an Iron(I) Boryl Complex. Organometallics 2014, 33, 5940–5943. 10.1021/om500847j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzacano T. J.; Mankad N. P. Thermal C–H borylation using a CO-free iron boryl complex. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 5379–5382. 10.1039/C4CC09180A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Wu C.; Ge S. Iron-Catalyzed E-Selective Dehydrogenative Borylation of Vinylarenes with Pinacolborane. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7585–7589. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K.; Kato T.; Nishibayashi Y. Hydroboration of Alkynes Catalyzed by Pyrrolide-Based PNP Pincer–Iron Complexes. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4323–4326. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani M.; Kusaka H.; Yuge H. Iron-catalyzed Versatile and Efficient C(sp2)-H Borylation. Chem. Lett. 2019, 48, 898–901. 10.1246/cl.190345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Britton L.; Docherty J. H.; Dominey A. P.; Thomas S. P. Iron-Catalysed C(sp2)-H Borylation Enabled by Carboxylate Activation. Molecules 2020, 25, 905. 10.3390/molecules25040905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narro A. L.; Arman H. D.; Tonzetich Z. J. Insertion chemistry of iron(II) boryl complexes. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 15475–15483. 10.1039/D2DT02879D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narro A. L.; Arman H. D.; Tonzetich Z. J. Mechanistic Studies of Alkyne Hydroboration by a Well-Defined Iron Pincer Complex: Direct Comparison of Metal-Hydride and Metal-Boryl Reactivity. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 10477–10485. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c01325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden H. B. Liquid Injection Field Desorption Ionization: A New Tool for Soft Ionization of Samples Including Air-Sensitive Catalysts and Non-Polar Hydrocarbons. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 10, 459–468. 10.1255/ejms.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Rauchfuss T. B.; Moore C. E.; Rheingold A. L.; De Gioia L.; Zampella G. Crystallographic Characterization of a Fully Rotated, Basic Diiron Dithiolate: Model for the Hred State?. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 15476–15479. 10.1002/chem.201303351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr M.; Heiß P.; Schütz M.; Bühler R.; Gemel C.; Linden M. H.; Linden H. B.; Fischer R. A. Enabling LIFDI-MS measurements of highly air sensitive organometallic compounds: a combined MS/glovebox technique. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 9031–9036. 10.1039/D1DT00978H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We have now termed this new species A-1, and the respective spin states are indicated with a superscript to the left of the capital letter

- Ligand 1f and complexes 2c,c′,e,f have not been previously reported.

- Okuniewski A.; Rosiak D.; Chojnacki J.; Becker B. Coordination polymers and molecular structures among complexes of mercury(II) halides with selected 1-benzoylthioureas. Polyhedron 2015, 90, 47–57. 10.1016/j.poly.2015.01.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Some historical literature has reported a range of products when utilizing these more flexible salen ligands, e.g. Fe2(salen)3; see the Supporting Information.

- Gallagher K. J.; Webster R. L. Room temperature hydrophosphination using a simple iron salen pre-catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 12109–12111. 10.1039/C4CC06526C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll O. J.; Hafford-Tear C. H.; McKeown P.; Stewart J. A.; Kociok-Köhn G.; Mahon M. F.; Jones M. D. The synthesis, characterisation and application of iron(III)–acetate complexes for cyclic carbonate formation and the polymerisation of lactide. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 15049–15058. 10.1039/C9DT03327K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott N.; Ford M.; Husbands D.; Whitwood A.; Fairlamb I. Reactivity of a Dinuclear PdI Complex [Pd2(μ-PPh2)(μ2-OAc)(PPh3)2] with PPh3: Implications for Cross-Coupling Catalysis Using the Ubiquitous Pd(OAc)2/nPPh3 Catalyst System. Organometallics 2021, 40, 2995–3002. 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhashmialameer D.; Collins J.; Hattenhauer K.; Kerton F. M. Iron amino-bis(phenolate) complexes for the formation of organic carbonates from CO2 and oxiranes. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 5364–5373. 10.1039/C6CY00477F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrea K. A.; Brown T. R.; Murphy J. N.; Jagota D.; McKearney D.; Kozak C. M.; Kerton F. M. Characterization of Oxo-Bridged Iron Amino-bis(phenolate) Complexes Formed Intentionally or in Situ: Mechanistic Insight into Epoxide Deoxygenation during the Coupling of CO2 and Epoxides. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 13494–13504. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino M.; Leo V.; Tedesco C.; Mazzeo M.; Lamberti M. Salen, salan and salalen iron(III) complexes as catalysts for CO2/epoxide reactions and ROP of cyclic esters. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 13229–13238. 10.1039/C8DT03169J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widegren J. A.; Finke R. G. A review of the problem of distinguishing true homogeneous catalysis from soluble or other metal-particle heterogeneous catalysis under reducing conditions. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2003, 198, 317–341. 10.1016/S1381-1169(02)00728-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Complexes 4c and 4d were characterized crystallographically from reaction mixtures during attempted trapping experiments. Precatalyst 2e was treated with HBpin or 9-BBN, and the resulting reaction mixture was treated with L-type ligands in an attempt to trap intermediates along the reduction pathway.

- Cozzi P. G. Metal–Salen Schiff base complexes in catalysis: practical aspects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, 410–421. 10.1039/B307853C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataramanan N. S.; Kuppuraj G.; Rajagopal S. Metal–salen complexes as efficient catalysts for the oxygenation of heteroatom containing organic compounds—synthetic and mechanistic aspects. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 1249–1268. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erxleben A. Transition metal salen complexes in bioinorganic and medicinal chemistry. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2018, 472, 40–57. 10.1016/j.ica.2017.06.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boulechfar C.; Ferkous H.; Delimi A.; Djedouani A.; Kahlouche A.; Boublia A.; Darwish A. S.; Lemaoui T.; Verma R.; Benguerba Y. Schiff bases and their metal Complexes: A review on the history, synthesis, and applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 150, 110451. 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.110451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borer L.; Thalken L.; Ceccarelli C.; Glick M.; Zhang J. H.; Reiff W. M. Synthesis and characterization of a hydroxyl-bridged iron(III) dimer of N,N’-ethylenebis(salicylamine). Inorg. Chem. 1983, 22, 1719–1724. 10.1021/ic00154a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eelman M. D.; Blacquiere J. M.; Moriarty M. M.; Fogg D. E. Shining New Light on an Old Problem: Retooling MALDI Mass Spectrometry for Organotransition-Metal Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 303–306. 10.1002/anie.200704489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey G. A.; Fogg D. E. Confronting Neutrality: Maximizing Success in the Analysis of Transition-Metal Catalysts by MALDI Mass Spectrometry. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4962–4971. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A.; Zijlstra H. S.; Collins S.; McIndoe J. S. Catalyst Deactivation Processes during 1-Hexene Polymerization. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 7195–7206. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A.; Killeen C.; Thiessen T.; Zijlstra H.; McIndoe S.; Joshi A.; Killeen C.; Thiessen T.; Zijlstra H. S.; McIndoe J. S. Handling considerations for the mass spectrometry of reactive organometallic compounds. J. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 57, e4740. 10.1002/jms.4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen C.; Liu J.; Zijlstra H. S.; Maass F.; Piers J.; Adams R.; Oliver A.; McIndoe J. S. Competitive isomerization and catalyst decomposition during ring-closing metathesis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 4000–4008. 10.1039/D3CY00065F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monillas W. H.; Yap G. P. A.; Theopold K. H. A Tale of Two Isomers: A Stable Phenyl Hydride and a High-Spin (S = 3) Benzene Complex of Chromium. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 6692–6694. 10.1002/anie.200701933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott N. W. J.; Ford M. J.; Schotes C.; Parker R. R.; Whitwood A. C.; Fairlamb I. J. S. The ubiquitous cross-coupling catalyst system ‘Pd(OAc)2’/2PPh3 forms a unique dinuclear PdI complex: an important entry point into catalytically competent cyclic Pd3 clusters. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 7898–7906. 10.1039/C9SC01847F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The simulated isotopic pattern and exact masses associated with these m/z values show significant deviations; we attribute this to the presence of significant ±2H species pertaining to various stages of reduction of the iminyl backbone. As such, the observed m/z pertains to an average of these species. However, it may also be possible that such deviation is a result of H-atom loss, thereby intensifying the [M – H] peak.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.