Abstract

Recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the superiority of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation to medical therapy in reducing mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction, but patients with end-stage HF were often excluded. A 64-year-old man diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy was hospitalized due to worsening HF and incident AF. An echocardiographic examination revealed the left ventricular end-diastolic diameter of 90 mm and left ventricular ejection fraction of 12 %. Cardioversion was performed to restore sinus rhythm, but intermittent transitions to AF caused the patient hemodynamic instability and mental distress. We carefully performed AF ablation, and sinus rhythm was maintained thereafter. After cardiac rehabilitation, he was successfully discharged home. However, he was re-hospitalized due to worsening HF 6 months post-AF ablation, and he eventually passed away. While AF ablation cannot prevent the progression of inherent cardiomyopathy, it can improve the quality of life even for patients with end-stage HF. However, the effect was temporary and considered a palliative treatment. This case highlights the potential benefits and limitations of AF ablation in end-stage HF patients and the need for further research to establish the optimal treatment for this population.

Learning objective

Atrial fibrillation ablation can restore sinus rhythm and improve the quality of life even in some patients with end-stage heart failure (HF). However, it cannot prevent the progression of inherent cardiomyopathy. In the era of interventional HF therapy, catheter ablation may have a palliative role in reducing patient distress caused by life-threatening arrhythmias in patients with end-stage HF.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Cardiac resynchronization therapy, Catheter ablation, End-of-life care, Heart failure

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) can be a cause and consequence of heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). AF in patients with HF is associated with a worse prognosis and requires aggressive management of both conditions. Recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of AF ablation for patients with HFrEF in terms of improving the hard endpoints such as survival, HF-related hospitalizations, functional capacity, and quality of life (QoL) [1], [2]. Thus, current guidelines have provided a Class IIa indication for AF ablation in selected patients with symptomatic AF and HF [3], [4]. However, patients with end-stage HF have been excluded from all major trials, leaving them without recommendations and evidence for optimal treatments. Among over 7800 experiences of AF ablation at our institution, a representative case of end-stage HF with significant left ventricular (LV) dilatation is described herein. Despite the successful treatment of intermittent hemodynamically unstable AF using catheter ablation, the patient ultimately died 9 months after the procedure due to worsening HF.

Case report

A 64-year-old man diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy was admitted to our hospital due to worsening HF with irregular wide QRS complex tachycardia (Fig. 1). Aside from the standard HF medications (i.e. enalapril 2.5 mg, bisoprolol 5 mg, and spironolactone 25 mg), he had received a cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) device (Medtronic VIVA™ XT CRT-D, Dublin, Ireland) for primary prevention 5 years before this hospitalization. Regardless of the treatments received, his cardiac function was severely impaired (i.e. LV ejection fraction of 11 %) with an enormously enlarged LV chamber size (LV end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters were 92 and 87 mm, respectively) and moderate degree of functional mitral regurgitation (Fig. 2A and Video 1). AF had previously been documented once, and he had experienced multiple atrial high-rate episodes; therefore, an oral anticoagulant and 100 mg of amiodarone were prescribed. His functional status had gradually deteriorated from New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III to ambulatory class IV.

Fig. 1.

The 12-lead electrocardiograms (A) during biventricular pacing at baseline (pacing rate of 80 bpm) and (B) during atrial fibrillation.

Fig. 2.

(A) The echocardiographic image during biventricular pacing after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. (a) Parasternal long-axis view. (b) Four-chamber view with color Doppler imaging. (c) Short-axis view of papillary muscle level. (d) Three-chamber view. (B) Three-dimensional images of the left atrium created by MDCT incorporated into the CARTO system. Radiofrequency energy application sites were tagged with a red sphere using an automated annotation system.

LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular; LVEDV; left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; MDCT, multi-detector computed tomography.

On admission, he experienced dyspnea, drowsiness, and hypotension (88/78 mm Hg) and tachypnea with an oxygen saturation of 90 % under a reservoir mask at 15 L/min. His jugular vein was distended, and his extremities felt cold and clammy. Chest X-ray imaging revealed substantial congestion, pleural effusions, and cardiomegaly. The 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated an irregular wide QRS complex tachycardia with a ventricular rate ranging from 120 to 160 bpm (Fig. 1). According to the telemetry check-up, the tachycardia was identified as an AF rhythm with various degrees of aberrant conduction. Given the patient's hemodynamically unstable condition, immediate cardioversion was performed in the emergency department.

Even after the successful restoration of sinus rhythm and administration of intravenous amiodarone and beta-blocker, a repetitive transition to AF caused hemodynamic instability requiring in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and electrical cardioversion. Fortunately, treatment in the intensive care unit using inotropes (i.e. 3 μg/kg/min of dobutamine) successfully stabilized the patient's hemodynamics, leading to sinus rhythm maintenance and recovery of his general condition. He underwent rehabilitation, and his functional status recovered to the original NYHA class III under sinus rhythm. However, incident AF caused a hemodynamic collapse, which required in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Under these conditions, the incident AF not only increased the risk of sudden cardiac death but also caused him suffering and distress. The physically and mentally unstable condition prevented him from adequate rehabilitation to improve his functional status.

The patient hoped to return home again. However, given the patient's economical condition and lack of familial support, the implantation of an LV assist device or heart transplantation was not a realistic option. We discussed three options with the patient: 1) AF ablation, 2) atrioventricular nodal ablation, and 3) end-of-life palliative care avoiding invasive treatment. An atrioventricular nodal ablation was not the direct therapy for AF, and the loss of atrial contraction would deteriorate the LV function; therefore, we decided to perform AF ablation first.

Radiofrequency energy was selected to create extensive encircling lesions around the pulmonary vein antrum and ablate the non-pulmonary vein AF trigger, if applicable. Under conscious sedation using dexmedetomidine as a sedative agent and pentazocine as an analgesic agent, we performed radiofrequency catheter ablation employing a 3D mapping system (CARTO 3, Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA, USA) (Fig. 2B) and an irrigated tip catheter with contact force-sensing technology (Thermocool Smarttouch SF, Biosense Webster). An automated ablation lesion annotation system with optimal settings for the contact force and catheter stability was used to achieve lesion durability [5]. Fortunately, non-pulmonary vein AF triggers were not identified and the procedure was completed without any complications. Then, no further AF attacks were observed during the hospitalization, allowing for sufficient cardiac rehabilitation. The patient's NYHA class improved from class III–IV to class II and he successfully returned home.

No atrial high-rate episodes were identified during the next 2 months by the CRT-D; however, they reappeared, and the patient's cardiac function gradually deteriorated during the follow-up period with further dilatation of LV size and without improvement of mitral regurgitation (Fig. 3). Although we discussed the potential efficacy of atrioventricular nodal ablation and mitral valve interventions, the patient did not select the treatment option. At approximately 5 months after discharge, he was re-hospitalized due to worsening HF and died during the hospitalization.

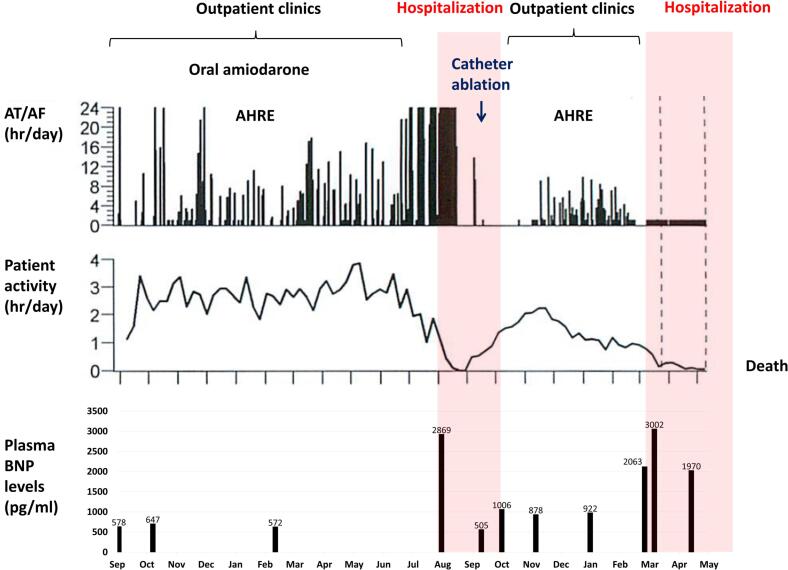

Fig. 3.

A cardiac compass (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) equipped with a cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator clearly presented the disease course of this patient. Although the patient's activity level recovered after catheter ablation of AF, it was never restored to the pre-ablation level. The patient's activity level decreased thereafter with the occurrence of AHRE.

AF, atrial fibrillation; AHRE, atrial high-rate episode; AT, atrial tachycardia; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide.

Discussion

The role of AF ablation in end-stage HF remains controversial. We encountered a case of end-stage HF wherein the occurrence of AF directly caused hemodynamic instability, and AF ablation successfully prevented his sudden deterioration of HF status. The introduction of angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors might have somewhat improved the prognosis, but they do not directly prevent the occurrence of AF. Thus, the role of catheter ablation in AF management is potentially important even in patients with end-stage HF. Although AF ablation cannot prevent the progression of inherent cardiomyopathy, it can contribute to symptom relief, decreased risk of re-hospitalizations, improved functional status, and enhanced emotional well-being even in patients with end-stage HF.

In our case, the drug-refractory AF increased the risk of HF re-worsening and promoted depression, impeding adequate rehabilitation. If sinus rhythm had been maintained, rehabilitation would have been feasible, and the recovery of the patient's general condition could have been expected. Consequently, we performed AF ablation as a “palliative” end-stage HF treatment, which successfully maintained sinus rhythm and facilitated the subsequent treatment. This alleviated the patient's suffering caused by AF and improved the prognosis, albeit for several months.

Recently, the concept of interventional HF therapy, which considers heart recovery and prevention of worsening HF via a multidisciplinary treatment using surgery, catheter intervention, and mechanical circulatory support devices, has been proposed worldwide [6]. In the field of arrhythmias, the advancements in catheter technologies and increased operator experience have drastically improved the safety profile of AF ablation. Although radiofrequency energy was used in this case, cryoballoon ablation is an important alternative with its low complication rate and proven efficacy. Furthermore, the use of mechanical circulatory support helps to stabilize a temporal deterioration in the hemodynamics during the procedures. Even when AF recurs, a significant reduction in the AF burden could lead to an improvement in the cardiac output, exercise tolerance, and QoL.

Notably, we do not recommend AF ablation in all HFrEF patients. In a nationally representative US cohort, congestive HF predicted early mortality after AF ablation [7]. Additionally, the CASTLE-AF trial found no prognostic superiority of AF ablation to medical therapy in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and/or NYHA class III or IV status [1]. Thus, we should discuss alternative treatment options with the patient and their families before performing AF ablation. Although mitral valve repair is a promising alternative, performing it for moderate functional mitral regurgitation remains controversial. A meta-regression identifies AF as an independent negative predictor of long-term mortality after MitraClip (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) implantation [8]. Thus, performing catheter ablation first may be reasonable, especially in paroxysmal AF cases. The implantation of an LV assist device or heart transplantation is another important option. However, these treatments are expensive and require familial support, thereby limiting the number of candidates. An atrioventricular nodal ablation is also an option in patients with HF and permanent AF [9]. However, physiological harmony between the atria and ventricle during sinus rhythm is important to stabilize the hemodynamics in end-stage HF patients. There may be differing opinions, but we believe that when malignant arrhythmias cause suffering and distress in end-stage HF patients, catheter ablation can serve as a palliative therapy to improve their QoL.

Conclusions

AF often develops with the progression of HF. AF occurrence can deteriorate the systemic hemodynamics and can be lethal in end-stage HF patients. Catheter ablation of AF cannot prevent an inherent disease progression and may only be a palliative therapy for end-stage HF, but it can significantly contribute to symptom relief, improved functional status, and enhanced emotional well-being even in such patients.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

The echocardiographic image during biventricular pacing.

Patient permission/consent statement

Consent for the anonymous use of the data was obtained from the patient prior to his death, and again from his relatives prior to submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. John Martin for his linguistic assistance with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Marrouche N.F., Brachmann J., Andresen D., Siebels J., Boersma L., Jordaens L., Merkely B., Pokushalov E., Sanders P., Proff J., Schunkert H., Christ H., Vogt J., Bänsch D., CASTLE-AF Investigators Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:417–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simader F.A., Howard J.P., Ahmad Y., Saleh K., Naraen A., Samways J.W., Mohal J., Reddy R.K., Kaza N., Keene D., Shun-Shin M.J., Francis D.P., Whinnett Z.I., Arnold A.D. Catheter ablation improves cardiovascular outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Europace. 2023;25:341–350. doi: 10.1093/europace/euac173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hindricks G., Potpara T., Dagres N., Arbelo E., Bax J.J., Blomström-Lundqvist C., Boriani G., Castella M., Dan G.A., Dilaveris P.E., Fauchier L., Filippatos G., Kalman J.M., La Meir M., Lane D.A., et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heidenreich P.A., Bozkurt B., Aguilar D., Allen L.A., Byun J.J., Colvin M.M., Deswal A., Drazner M.H., Dunlay S.M., Evers L.R., Fang J.C., Fedson S.E., Fonarow G.C., Hayek S.S., Hernandez A.F., et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e895–e1032. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka N., Inoue K., Tanaka K., Toyoshima Y., Oka T., Okada M., Inoue H., Nakamaru R., Koyama Y., Okamura A., Iwakura K., Sakata Y., Fujii K. Automated ablation annotation algorithm reduces re-conduction of isolated pulmonary vein and improves outcome after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Circ J. 2017;81:1596–1602. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saku K., Yokota S., Nishikawa T., Kinugawa K. Interventional heart failure therapy: a new concept fighting against heart failure. J Cardiol. 2022;80:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2021.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng E.P., Liu C.F., Yeo I., Markowitz S.M., Thomas G., Ip J.E., Kim L.K., Lerman B.B., Cheung J.W. Risk of mortality following catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2254–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur S., Sadana D., Patel J., Gad M., Sankaramangalam K., Krishnaswamy A., Miyasaka R., Harb S.C., Kapadia S.R. Atrial fibrillation and transcatheter repair of functional mitral regurgitation: evidence from a meta-regression. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2374–2384. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brignole M., Pentimalli F., Palmisano P., Landolina M., Quartieri F., Occhetta E., Calò L., Mascia G., Mont L., Vernooy K., van Dijk V., Allaart C., Fauchier L., Gasparini M., Parati G., et al. AV junction ablation and cardiac resynchronization for patients with permanent atrial fibrillation and narrow QRS: the APAF-CRT mortality trial. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4731–4739. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The echocardiographic image during biventricular pacing.