Abstract

The development of new anti-cancer agents is an urgent necessity nowadays, as it is one of the major causes of mortality worldwide. Many drugs currently used are derived from natural products. Halimanes are a class of bicyclic diterpenoids present in various plants and microorganisms. Many of them exhibit biological activities such as antitumor, antimicrobial, or anti-inflammatory. Among them, ent-halimic acid is an easily accessible compound, in large quantities, from the ethyl acetate extract of the plant Halimium viscosum, and it has been used as a starting material in a number of bioactive molecules. In this work, we review all the natural halimanes with antitumor and related activities until date as well as the synthesis of antitumor compounds using ent-halimic acid as a starting material.

Keywords: halimanes, ent-halimic acid, antitumor, diterpenes, cancer, natural products

1 Introduction

Natural products (NPs) constitute an abundant and diverse source of chemical structures, which are currently used in the search of bioactive molecules and drug discovery (Karageorgis et al., 2021). In this manner, the study of natural products and their derivatives remains one of the most important research areas in organic, biological, and medicinal chemistry (Kumar and Waldmann, 2009; Karageorgis et al., 2021).

Among the last decades, natural product-like drugs have a higher success rate in showing bioactivity (Newman and Cragg, 2012). In fact, approximately half of the drugs in clinical use come from living organisms (Paterson and Anderson, 2005), and in the last few years, 73% of antitumor drugs were either natural products, bioinspired compounds, or natural product derivatives (Wilson and Danishefsky, 2006; Newman and Cragg, 2007).

This elevated bioactivity of NPs can be explained by the purpose of their biosynthesis itself (Danishefsky, 2010). Living organisms synthesize compounds in order to use them in their own metabolic pathways. Thus, these compounds fit in different kinds of proteins and enzymes involved in metabolic engineering. Hence, these compounds possess well-defined tridimensional structures rich in functional groups and adequately oriented in space, which can be used in drug modeling with a higher success rate.

Because of this, organic chemists have developed a number of strategies to obtain bioactive compounds inspired in natural products. These strategies consist of diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS), biology-oriented synthesis (BIOS), diverted total synthesis (DTS), analog-oriented synthesis (AOS), two-phase synthesis, function-oriented synthesis (FOS), computed affinity/dynamically ordered retrosynthesis (CANDOR), and more recently, a pharmacophore-directed retrosynthesis (PDR) (Wilson and Danishefsky, 2006; Truax and Romo, 2020).

Bioactive compounds are often asymmetric, and their biological activity is closely related to one of the enantiomers. However, there is also the possibility that both enantiomers show different activity. For this reason, the effective synthesis of homochiral molecules that are enantiomerically pure remains one of the biggest challenges that modern organic chemistry must face. Thus, in order to reach enantiomerically pure compounds, different methodologies can be applied from the kinetic resolution of racemic mixtures to the enantioselective synthesis using chiral natural products as starting materials (chiral pool) as well as the asymmetric synthesis using chiral auxiliaries, reagents, or catalysts for that purpose.

The synthetic approach to bioactive compounds by the transformation of easily accessible and abundant natural products (chiral pool) is widespread. The use of these natural products in the enantioselective synthesis of compounds of similar carbon backbones usually represent an advantage compared with the total synthesis in terms of economy of the process and synthetic steps. Many examples can be collected from the literature where chiral pools are used, but the examples of the synthesis of paclitaxel (Taxol®) (Gennari et al., 1996; Kingston et al., 2002) and ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743, Yondelis®) (Cuevas et al., 2000) are paradigmatic of this strategy.

Ent-halimic acid 1 belongs to the bicyclic diterpene family of halimanes (Urones et al., 1987; Roncero et al., 2018). The use of 1 as a starting material allowed access to a variety of compounds with biological interest, such as antibiotic, antifeedant, antitumor, antifouling, and antiviral.. In this work, the use of ent-halimic acid 1 as a starting material in the synthesis of antitumor compounds is reviewed (Figure 1). Compound 1 is easily accessible in large quantities from the ethyl acetate extract of Halimium viscosum (Cistaceae). The vegetal source is widespread in the Iberian Peninsula, mainly in Spain (De Pascual Teresa et al., 1985; De Pascual Teresa et al., 1986; Urones et al., 1987) and Portugal (Rodilla et al., 1998; Rodilla et al., 2001).

FIGURE 1.

Halimium viscosum (chemotype Villarino de los Aires).

The functionalization appearing in ent-halimic acid, with an allylic hydroxylic group in the side-chain and a Δ1(10) double bond in the bicyclic system as well as a carboxylic acid at C-18, confer to excellent characteristics of (1) for its use as a starting material in the synthesis of antitumor compounds.

We have divided this work in two main aspects: first, we will summarize all the known natural halimanes, which exhibit antitumor as well as antitumorigenic-related bioactivities, and finally, we will review all the synthesis of bioactive compounds using ent-halimic acid as a starting material.

2 Natural bioactive halimanes

Natural halimane skeleton compounds showing antitumor activity as well as antitumorigenic-related bioactivities are reviewed herein (Figures 2–5). These antitumor compounds have been classified into four groups according to their structural frameworks (data shown in parentheses represent the IC50 value of the corresponding compound).

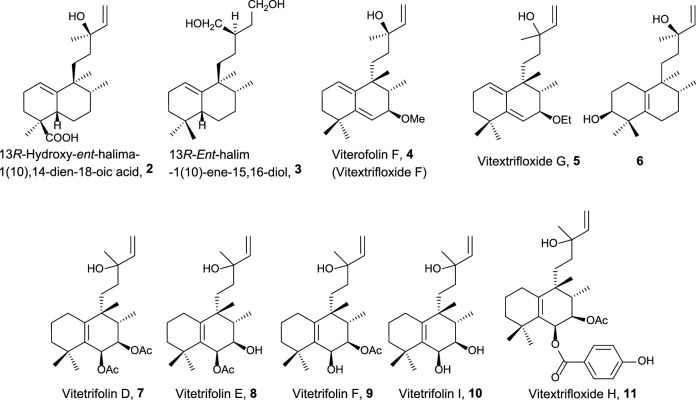

FIGURE 2.

Halimanes showing an acyclic side-chain framework with antitumor and related activities.

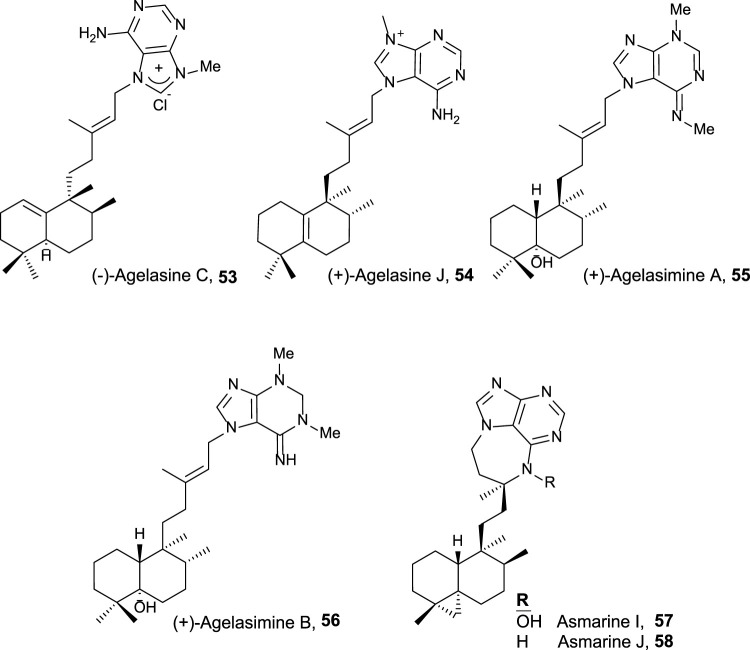

FIGURE 5.

Halimano purines with antitumor and related activities.

The first group of natural halimanes is characterized by having an acyclic side chain (Figure 2), and all of them were tested in vitro, showing the following results:

• 13R-Hydroxy-ent-halima-1(10),14-dien-18-oic acid 2 showed low activity against the A2780 human ovarian cell line (40 μg/mL) (Abdel-Kader et al., 2002).

• 13R-ent-halim-1(10)-ene-15,16-diol 3 exhibited moderate activity against MDA-MB-435 (melanoma, 23 µM), SF-295 (glioblastoma, 23 µM), and HCT-8 (colon adenocarcinoma, 13 µM) was also tested as a bactericide, achieving better results (Silva et al., 2015).

• Vitextrifloxide G 5 presented potent Top1 inhibition activity, while viterofolin F 4 was much less active. Compounds 5 (20.3 µM), 7 (22 µM), and 11 (24.6 µM) showed moderate activity against HCT-116 colorectal carcinoma cells (Luo et al., 2017).

• Compound 6 presented moderate activity against AGZY 83a (lung cancer cell lines, 21.5 µM) and SMMC-7721 (liver cancer cell lines, 28.5 µM) (Yang et al., 2010).

• Vitetrifolins 7–10 showed potent to moderate cytotoxicity against the HeLa cell line (4.9–22.5 µM) (Wu et al., 2009).

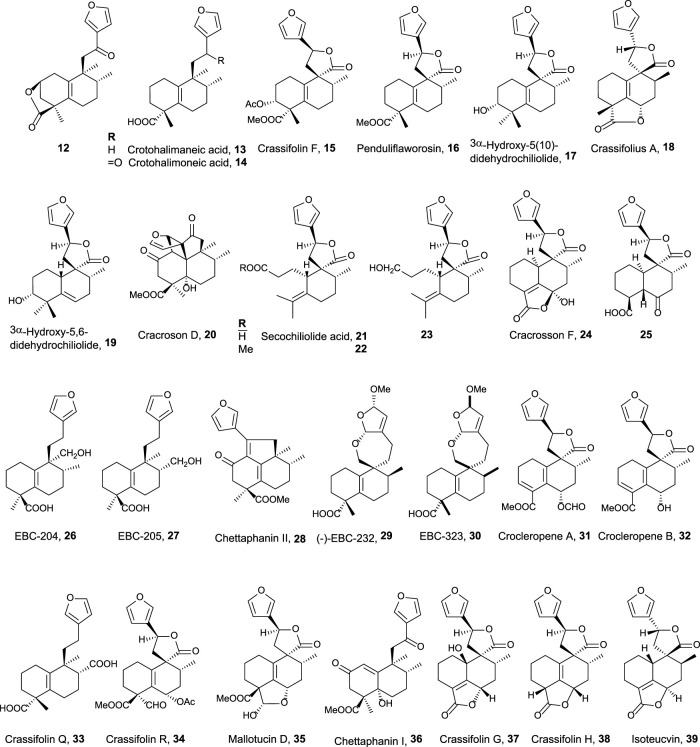

The second group of natural halimanes is characterized by showing a cyclic side chain containing a furan ring (Figure 3), and all of them were tested in vitro, showing the following results:

• 12 exhibited moderate activity against HeLa cell lines (16 µM) (Marcos et al., 2008).

• 13 and 14 showed non-specific strong cytotoxicity against human breast ductal carcinoma (BT474), lung carcinoma (CHAGO), human liver hepatoblastoma (HEP-G2), human gastric carcinoma (KATO-3), and human colon adenocarcinoma (SW620) between 0.1 and 8.2 μg/mL (Roengsumran et al., 2004). Compound 14 inhibits K562 cell growth (9 μg/mL), while compounds 26, 27, and 13 are less active. These compounds were also tested against other solid tumor cell lines (>10 μg/mL) (Maslovskaya et al., 2019).

• Crassifolin F 15 showed low antiangiogenic activity (75 µM), while penduliflaworosin 16 exhibited high activity (3.4 µM) compared to the positive control (Wang et al., 2016).

• Compounds 17 and 19 were tested against PANC-1 (human ductal pancreatic carcinoma, 2.5 and 0.3 µM, respectively) and LM3 (murine lung adenocarcinoma, 3 and 40 µM, respectively) cancer cell lines, showing high cytotoxicity; while compounds 21, 22, and 23 were moderately active (14.1–31.6 µM) (Sánchez et al., 2010).

• Crassifolius A 18 showed cytotoxicity against Hep3B (17.9 µM) human liver cancer cell lines (Tian et al., 2017).

• Compounds 20, 24, 25, 36, 37, 38, and 39 exhibited low to moderate cytotoxicity toward colorectal adenocarcinoma T24 (12.3–40.3 µM) and epithelial carcinoma A549 cell lines (11.6–51.9 µM) (Qiu et al., 2018).

• Chettaphanin II 28 showed cytotoxic activity against HL-60 and A549 cell lines (Yuan et al., 2017).

• Compounds 29 and 30 were tested against several cell lines but only showed moderate activity against K562 cell lines (16 and 3 μg/mL) (Maslovskaya et al., 2020).

• Crocleropenes A and B (31 and 32) showed weak cytotoxicity against MCF7 cell lines (36 μM and 40 µM) (Zou et al., 2020).

• Crassifolins Q and R (33 and 34) were tested for anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenesis activities showing moderate activities (Li et al., 2021).

• Mallotucin D 35 was isolated in 1981, along with mallotucin C, from Mallotus repandus (Nakatsu et al., 1981). Although, its bioactivity was not tested until 2022, Dai et al. (2022) evaluated its activity against hepatocellular carcinoma. Mallotucin D shows the inhibition of cell proliferation and DNA synthesis plus the induction of autophagic mechanisms.

FIGURE 3.

15,16-Furo-halimanes with antitumor and related activities.

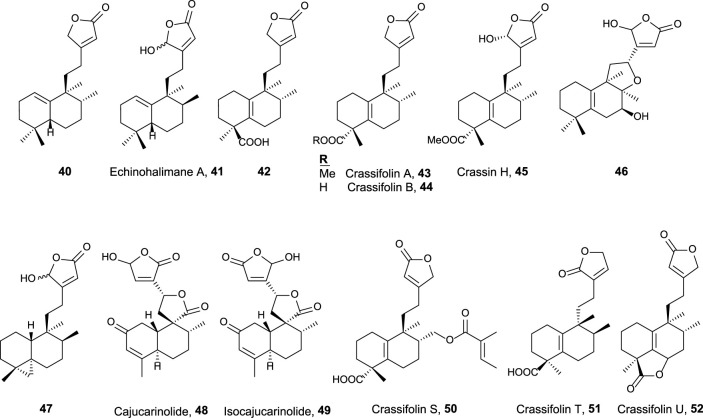

This group is characterized by a cyclic side chain consisting of a butenolide or γ-hydroxybutenolide framework (Figure 4), which shows the following result:

• Ent-halimanolide 40 showed cytotoxicity at micromolar levels against HeLa (5.0 µM) and MDCK (5.1 µM) cell lines (Marcos et al., 2003b).

• Echinohalimane A 41 exhibited cytotoxicity toward a variety of hematologic and solid tumor cell lines, showing better results for the latter ones including MOLT-4 (2.1 μg/mL), HL-60 (2.1 μg/mL), DLD-1 (0.96 μg/mL), and LoVo (0.56 μg/mL) cell lines (Chung et al., 2012).

• Compounds 42, 43, and 44 exhibited cytotoxicity toward colorectal adenocarcinoma T24 cell lines (37.3 µM, inactive, and 34.5 µM, respectively) and epithelial carcinoma A549 cell lines (18.9, 34.5, and 16.3 µM, respectively) (Qiu et al., 2018).

• Crassifolins A and B (43, 44) showed moderate antiangiogenic activity (15.4 and 16.7 µM) (Wang et al., 2016).

• Compound 46 presented moderate cytotoxicity against several cell lines (13.7–16.9 μg/mL) (Scio et al., 2003).

• Compound 47, isolated from a gorgonian coral of genus Echinomuricea, showed low cytotoxicity (13.2–37.1 µM) against several cell lines of hematological and solid tumors (Cheng et al., 2012).

• Crassin H 45 exhibited cytotoxic activity against HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia, 11.8 µM) and A549 (human lung adenocarcinoma, 5.2 µM) cell lines (Yuan et al., 2017).

• Cajucarinolide 48 and isocajucarinolide 49 are potent PLA2 inhibitors with IC50 of 5.8 and 2.3 μg/mL, respectively, (Ichihara et al., 1992). PLA2 may be a target in cancer treatment because it is involved in pro-inflammatory and pro-tumoral pathways (Peng et al., 2021; Vecchi et al., 2021).

• Crassifolins S-U (50–52) were isolated from Croton crassifolius and tested for anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenesis activities (Li et al., 2021). All of them were active, and crassifolin U 52 was the most active for both bioactivities.

FIGURE 4.

15,16-Halimanolides with antitumor and related activities.

Finally, halimane–purine hybrids constitute this last group (Figure 5), which presented the following interesting bioactivities together with their cytotoxicity:

• Agelasine C 53 showed Na,K-ATPase inhibitory effects and antimicrobial activities (Nakamura et al., 1984).

• Agelasine J 54 presented low cytotoxicity on breast cancer MCF7 cell lines (33 µM) (Appenzeller et al., 2008).

• Agelasimines A and B (55 and 56) exhibited cell growth inhibition against L1210 mouse leukemia cell lines in vitro (ED50 = 2–4 μg/mL), despite their most interesting biological activity is their action as Ca2+ channel antagonists as well as α1 adrenergic blockers (Fathi-Afshar and Allen, 1988).

• Asmarines I and J (57 and 58) showed moderate cytotoxicity against a variety of cancer cell lines (Rudi et al., 2004).

3 Synthesis of antitumor terpenoids using ent-halimic acid as a starting material

In this part of the work, the synthesis of a series of antitumor compounds using ent-halimic acid 1 as a starting material is described.

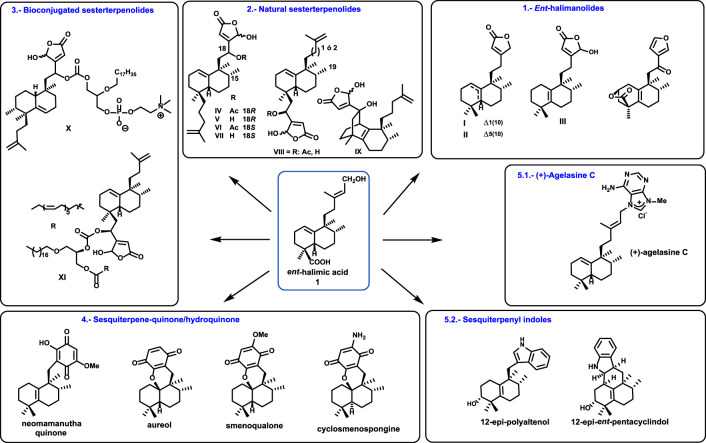

Using ent-halimic acid 1 (Figure 6) as a starting material, the following compounds have been synthesized:

1. Natural ent-halimanolides and furo ent-halimanolides.

2. Sesterterpenolides analogs of dysidiolide.

3. Sesterterpenolides hybridized with edelfosine analogs and PUFAs.

4. Quinone/hydroquinone and sesquiterpenoquinones.

-

5. Terpenoid alkaloids:

5.1. (+)-Agelasine C

5.2. Sesquiterpenyl indoles

FIGURE 6.

Overview of the use of ent-halimic acid 1.

3.1 Synthesis of ent-halimanolides

Starting from ent-halimic acid 1, a series of natural ent-halimanolides have been synthesized. These compounds are characterized by showing a lactone ring in any position of the halimane skeleton. The synthetic routes and biological evaluations are described for each case.

3.1.1 Synthesis of butenolides and γ-hydroxybutenolides

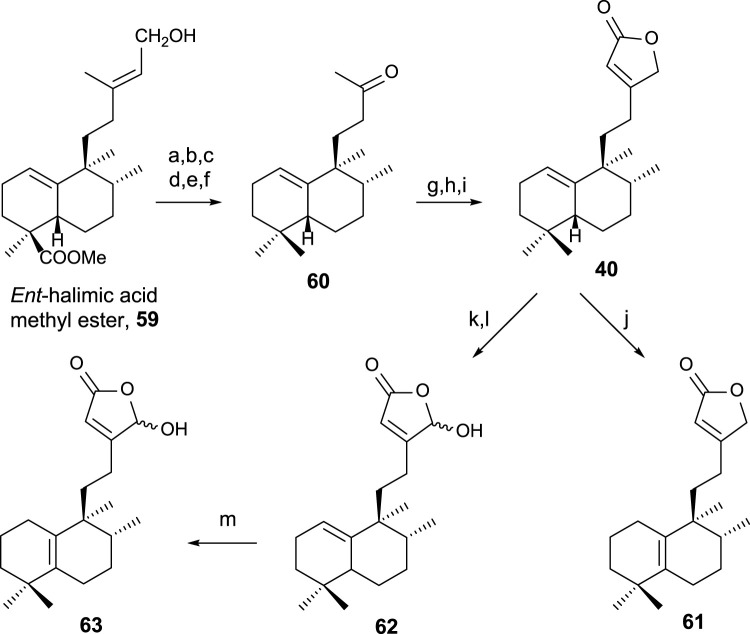

The synthesis of 40, 61, and 63 (Hara et al., 1995) using ent-halimic acid methyl ester 59 as a starting material is performed according to the route showed in Scheme 1 (Marcos et al., 2003b; Marcos et al., 2005b).

SCHEME 1.

(a) NaH, MeI, and THF (92%); (b) LAH and Et2O (96%); (c) TPAP and NMO (91%); (d) diethylene glycol, NH2NH2·H2O, KOH, 175°C–230°C, and 23 h (85%); (e) m-CPBA (92%); (f) H5IO6, THF, and H2O (91%); (g) LDA, TMSCl, THF, and −78°C (97%); (h) OsO4, NMO, and tBuOH/THF/H2O (7:2:1) (96%); (i) Ph3P = C=C=O and C6H6 (91%); (j) I2/C6H6 (10–2 M) (99%); (k) LDA, TBDMSTf, THF, and −78°C (94%); (l) m-CPBA (77%); (m) HI/C6H6 (5 × 10–2 M) (99%).

The transformation of 59 of the intermediate methyl ketone 60 in six steps (Scheme 1) consists of C18 reduction and degradation of the carbon side chain. To access the key intermediate 40, the butenolide framework is attached in three steps by a reaction with Bestmann ketene to the corresponding α-hydroxyketone of 60, yielding 40. For accessing 61, the double-bond isomerization is required, and in the case of 63, oxidation of C16 and double-bond isomerization is required (Boukouvalas and Lachance, 1998).

Compounds 40, 61, and 63 have been biologically evaluated, with butenolide 40 exhibiting the highest cytotoxic activity (HeLa) (Marcos et al., 2003b).

3.1.2 Furo-ent-halimanolide synthesis

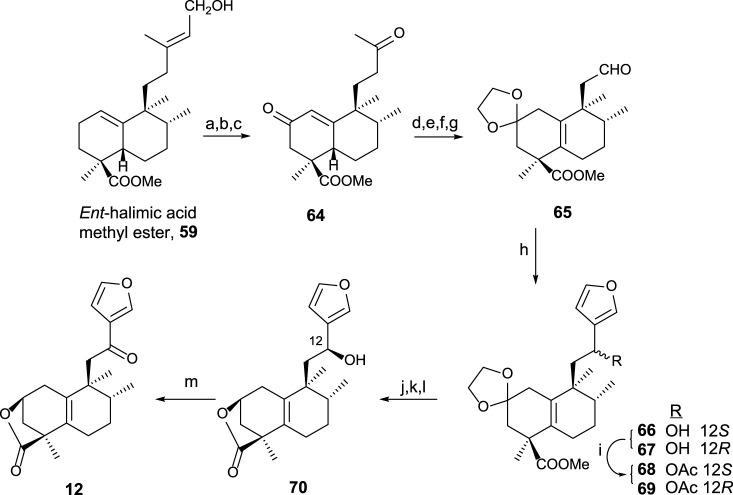

Using 59 as a starting material (Marcos et al., 2008), furo-ent-halimanolide 12 was synthesized (Scheme 2).

SCHEME 2.

(a) OsO4, NMO, t-BuOH/THF/H2O (7:2:1); (b) Pb(AcO)4, C6H6, 20 min (94%, two steps); (c) Na2CrO4, Ac2O/AcOH, NaOAc, and C6H6 (64%); (d) MePPh3Br, NaHMDS, THF, −78°C (94%); (e) p-TsOH, C6H6, 60°C (96%); (f) (CH2OH)2, p-TsOH, C6H6, Dean–Stark (97%), (g) 1) OsO4, NMO, t-BuOH, THF, and H2O; 2) Pb(AcO)4 and C6H6 (96%, two steps); (h) 3-bromofuran, n-BuLi, and THF (66: 54% and 67: 39%); (i) Ac2O and pyridine (98%); (j) HCl·2M and EtOH (96%); (k) Na2CO3, MeOH, 2 h, (96%); (l) NaBH4 and EtOH (12S: 38% and 12R: 43%); (m) TPAP, NMO, DCM, rt, 50 min (92%).

The synthesis of 12 from ent-halimic acid methyl ester 59 uses aldehyde 65 as an advanced intermediate. The transformation of 59 into 64 consists of the degradation of the side chain and C-2 functionalization, and then the tetranoraldehyde 65 is synthesized by side chain shortening and C-2 functionalization, which in parallel causes the double-bond isomerization. The furyl fragment is coupled to the aldehyde 65 in the side chain. After that, lactonization and C-12 oxidation lead to 12 in good yield.

The biological assays carried out showed antitumor activity for compound 12 against HeLa cell lines (Marcos et al., 2003b).

3.2 Sesterterpenolide synthesis

The study of marine metabolites has aroused great interest in recent years. Among these natural products, a considerable number of sesterterpenoids have been isolated (Faulkner, 2001; Blunt et al., 2003). Many of them possess a γ-hydroxybutenolide (Brohm and Waldmann, 1998; Demeke and Forsyth, 2000; Piers et al., 2000) moiety as a significant structural feature and, in many cases, are involved in their biological activities.

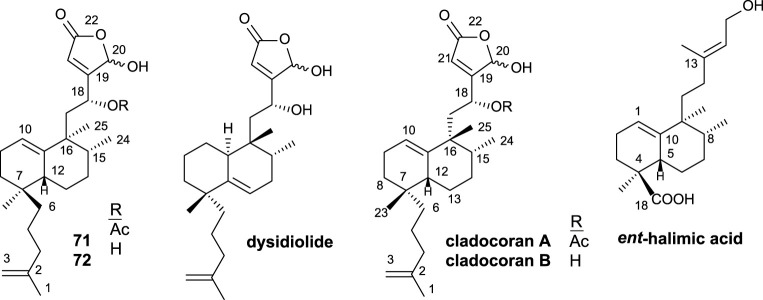

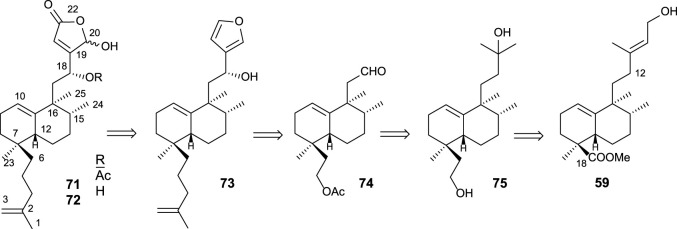

Cladocoran A and B (Figure 7) are sesterterpenolides, whose initially proposed structures were 71 and 72 (Fontana et al., 1998). The synthesis of these structures from ent-halimic acid, together with the spectroscopic data of the natural products named cladocoran A and B, led to the suggestion of a revision of their proposed structures as isoprenyl ent-halimanolides.

FIGURE 7.

Some structures of sesterterpenolides synthesized from ent-halimic acid: dysidiolide and analogs, cladocoran A, and cladocoran B.

The synthesized isoprenyl ent-halimanolides 71 and 72 are dysidiolide analoges (Gunasekera et al., 1996), sesterterpenolides, that have attracted considerable attention from chemists, biologists, and pharmacologists due to their biological evaluations as antitumor agents (Corey and Roberts, 1997; Magnuson et al., 1998; Demeke and Forsyth, 2000; Eckstein, 2000; Brohm et al., 2002a).

3.2.1 Synthesis of sesterterpenolides 71 and 72

Together with the synthesis of 71 and 72 (Marcos et al., 2002; Marcos et al., 2003a), the synthesis of the enantiomers and their C-18 epimers by Miyaoka et al. (2003) made it possible to establish the structure of the natural products cladocoran A and B as an olefinic analog of dysidiolide (cladocoran B) and its acetate (cladocoran A).

The synthesis of 71 and 72 using 59 as a starting material was accomplished according to the following retrosynthetic pathway (Scheme 3).

SCHEME 3.

Retrosynthesis for 71 and 72 from ent-halimic acid.

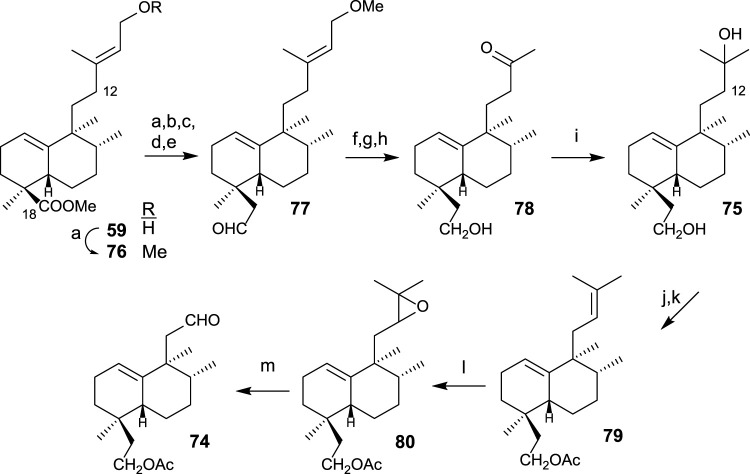

The synthesis of diol 75 (Scheme 4) is afforded by transformation in seven steps. First, the homologation and reduction of C18 position are performed, yielding intermediate 77, to which the side chain is degraded and adequately functionalized, leading to diol 75. The synthesis of aldehyde 74 from intermediate diol 75 is performed in four steps consisting of the shortening of the side chain in two carbons (C13 and C16) (Scheme 4). For that purpose, the following transformations are required: protection of the primary alcohol as an acetyl derivative and dehydration of the side chain alcohol; then, oxidation and cleavage of the resulting epoxide.

SCHEME 4.

(a) LAH, Et2O, 1 h (96%); (b) TPAP, NMO, DCM, 15 min, (90%); (c) TsCl, pyridine, 16 h (96%); (d) (MeOCH2PPh3)+Cl−, NaHMDS, THF, −78°C, 20 min (92%); (e) acetone/H2O, p-TsOH (0.3 mol/mol), 4 h (77: 98%); (f) LAH, Et2O, 30 min (96%); (g) OsO4, NMO, t-BuOH/THF/H2O (7:2:1), 24 h (99%); (h) LTA, C6H6, and 20 min (95%); (i) MeMgBr, Et2O, −78°C, and 1 h 30 min (91%); (j) Ac2O, pyridine, and 5 h (95%); (k) POCl3, pyridine, r.t., and 1 h; (l) m-CPBA, DCM, 0°C to r.t., and 2 h (90%); (m) H5IO6, THF, H2O, and 15 min (46%).

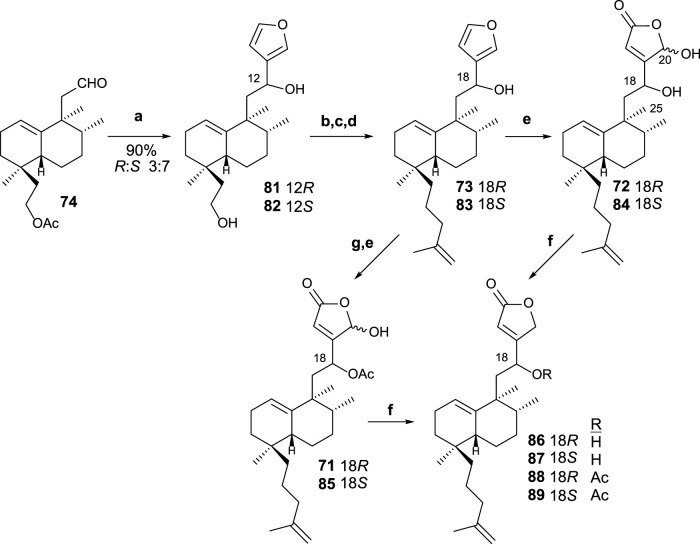

The reaction of aldehyde 74 with 3-furyllithium led to furo derivatives 81 and 82 (Scheme 5). Taking each C8 epimer separately, 81 and 82 are transformed in the corresponding isoprenyl-ent-furohalimanes 83 (18S) and 73 (18R), respectively, by elongation of the carbon chain of the southern part in three steps.

SCHEME 5.

(a) 3-bromofurane, n-BuLi, THF, −78°C, and 20 min; (b) TsCl, pyridine, and 4 h; (c) NaI and acetone; (d) CH2 = C(CH3)-CH2MgCl, THF, and 12 h. (e) 1O2, hν, rose bengal, DIPEA, DCM, −78°C, and 2 h 30 min; (f) NaBH4, EtOH, and 10 min; (g) Ac2O, Pyr, and 8 h.

Finally, the oxidation of furo derivatives 73 and 83 led to their corresponding γ-hydroxybutenolides 72 and 84. When C18 is first acetylated, the same procedure applied to compounds 71 and 85. The γ-hydroxybutenolides 71, 72, 84, and 85 can be decreased, respectively, to the corresponding butenolides 88, 86, 87, and 89. The interest in disposing of other synthetic analogs of dysidiolide for their antitumor activities led the obtention of these butenolide-containing sesterterpenoids, readily available from their corresponding γ-hydroxyderivatives.

The cytostatic and cytotoxic properties in tumor cell lines (HeLa, HL-60, HT-29, and A549) of compounds 72, 84, 85, and 87 were determined showing IC50 in the range of 0.9–7.9 μM. The results are comparable with dysidiolide (Takahashi et al., 2000) where the synthesized compounds improve the antitumor activity against some tumor cell lines.

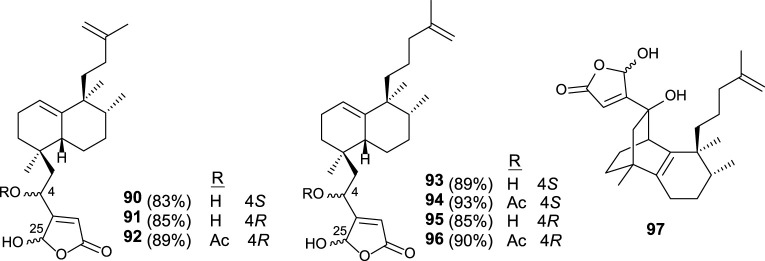

Similar synthetic procedures were applied for the synthesis of new dysidiolide analogs (90–96), where the butenolide moiety appears in the south part and the isoprenyl unit is bonded as a carbon side chain (Figure 8). Other analogs (97) have been synthesized showing a tricyclic core system in which the γ-hydroxybutenolide is attached (Marcos et al., 2007).

FIGURE 8.

Dysidiolide analogs synthesized from ent-halimic acid.

The in vitro antitumor activity for these synthetic compounds was tested in HeLa, HL-60, HT-29, and A549 cell-lines. The capability of compounds 90–97 to inhibit tumor cell growth was significant in the low micromolar range. In this manner, these dysidiolide analogs are slightly more potent than proper dysidiolides (Marcos et al., 2007).

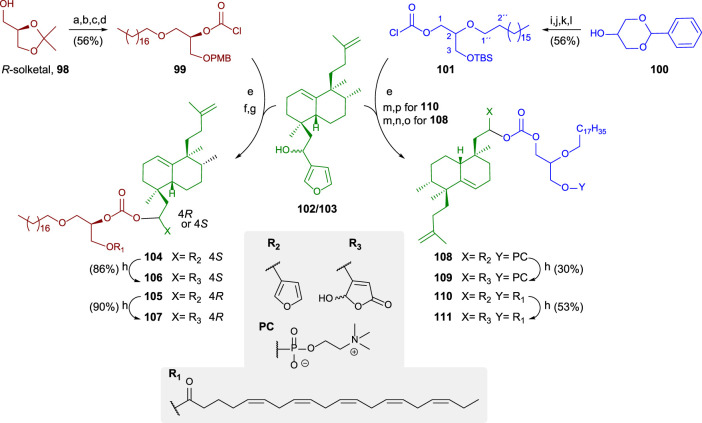

3.3 Synthesis of PUFAs and phospholipid hybrids with sesterterpenoids

Bioconjugate compounds have emerged in the last decades as a novel tool and therapeutic strategy in medicinal chemistry (Nilo et al., 2014; Lampkowski et al., 2015; Romero-Hernández et al., 2015; Shenvi et al., 2015; Zamudio-Vazquez et al., 2015). Bioconjugate molecules have been described as bioactive agents, showing a synergistic effect due to conjugation.

Bioconjugates of paclitaxel with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) gave good results in anticancer therapy, reducing the toxicity and allowing a slow release in cancer cells (Bradley et al., 2001; Kuznetsova et al., 2006). Some of the most studied bioconjugates are alkyl glycerol derivatives with different biological active molecules (Huang and Szoka, 2008; Jung et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2009; Linderoth et al., 2009; Pedersen et al., 2009; Pedersen et al., 2010a; Pedersen et al., 2010b; Christensen et al., 2010; Magnusson et al., 2011; Pedersen et al., 2012). In many cases, these hybrids are considered prodrugs (Kuznetsova et al., 2006; Pedersen et al., 2009).

On the other hand, edelfosine is a well-known alkylether lipid that belongs to the so-called antitumor lipid family and is widely studied for its antitumor, antiparasitic, and other bioactivities (Mollinedo et al., 1997; Gajate and Mollinedo, 2002; Mollinedo et al., 2004). In addition, PUFAs as DHA and EPA show antitumor activity. In this way, synthesizing hybrid compounds of these antitumor molecules makes a promising approach for antitumor therapy. The following part describes the synthesis and biological results of the antitumor sesterterpenoid hybrids that are structurally related to dysidiolide with PUFAs and edelfosine analogs (Gunasekera et al., 1996; Corey and Roberts, 1997; Brohm et al., 2002a; Brohm et al., 2002b).

Taking the furyl and γ-hydroxybutenolide bioconjugates as examples for the synthesis of these kinds of compounds, the synthetic route can be divided in three steps: synthesis of the glycerolipid, conjugation with the sesterterpenoid fragment previously synthesized via carbonate linker, and finally, adequate functionalization of the glycerolipid either via phosphocholine polar head or EPA esterification.

A general synthetic scheme for the synthesis of the bioconjugates 104–111 is shown in Scheme 6 (Gil-Mesón et al., 2016). The preparation of the bioconjugate dealt here consists of three key steps: synthesis of the lipidic chain and its adequate functionalization for the hybridization step; synthesis of the sesterterpenic fragment, and finally, coupling of both fragments and derivatization for new analogs.

SCHEME 6.

(a) Bromooctadecane, NaNH2, toluene, and 92%, (b) p-TsOH, MeOH, 40°C, and 93%, (c) 1. n-Bu2SnO and toluene, 2. CsF, PMBCl, DMF, and 80%, (d) trichloromethylchloroformate, N,N-dimethylaniline, THF, and 83%; (e) DMAP, DIPEA, toluene, and 60%; (f) DDQ and DCM/H2O; (g) EPA, EDAC, DMAP, DCM, rt, 104: 87%, and 105: 82%; (h) 1O2, rose bengal, DIPEA, DCM, 106: 86%, and 108: 90%. (i) Bromooctadecane, NaNH2, toluene, and 98%, (j) p-TsOH, MeOH, 40°C, and 90%, (k) TBDMSCl, imidazole, DMF, and rt; (l) trichloromethylchloroformate, N,N-dimethylaniline, THF, and 71%; (m) TBAF, THF, rt, and 89%; (n) POCl3, pyridine, THF, oC, and 97%; (o) choline tetraphenylborate, TPS, pyridine, and 35%; (p) EPA, EDAC, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt, and 64%.

The glycerolipidic part of the molecule is readily prepared from R-solketal 100 in four steps to access the chlorocarbonate 99 that is adequate for the coupling with the sesterterpenoid 102/103 and yielding the hybrids showing the furan moiety. In these cases, the sesterterpenolide is bonded to the glycerol in sn2 (Gil-Mesón et al., 2016).

For preparing sn1-bonded sesterterpenoid from racemic glycerol, 100 is used as a starting material in the synthesis of the glycerolipid. The protected triol 100 is transformed into 101 in four steps, attaching a chlorocarbonate in sn1. The coupling to form the bioconjugate occurs in excellent yield. The esterification between EPA and a glycerol hydroxy group is performed to obtain the furo-bioconjugates (104, 105, and 110). The following two steps are required to attach a phosphocholine polar head to the glycerolipid: phosphorylation and choline esterification, leading to the corresponding glycerophospholipid bioconjugate (108). The transformation of the furylderivatives (104, 105, 108, and 110) into the corresponding hydroxybutenolides can be performed by oxidation with 1O2 and rose bengal, yielding 106, 107, 109, and 111, respectively.

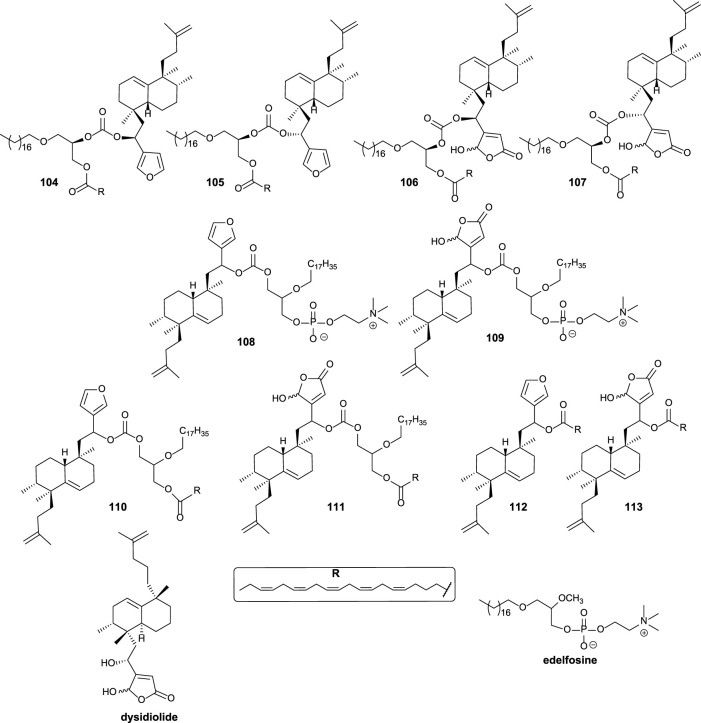

Different structural modifications have been introduced in the synthesis of the bioconjugated compounds, including synthesizing molecules showing the furyl or butenolide fragments in the north or south part, as well as bioconjugation with a PUFA directly via a carbonate group or bioconjugation with a PUFA through a glycerol unit attached to the carbonate linker (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Alkyl glycerol sesterterpenoid bioconjugate compounds 104–111 and sesterterpenoid-PUFAs 112–113, synthesized by Gil-Mesón et al. (2016).

The synthesized bioconjugates have been tested against different tumor cell lines (HeLa and MCF-7). The corresponding bioconjugates showed higher antitumor activity compared with their relative non-conjugate fragments, but simple bioconjugates 112 and 113 show higher activities compared with 108 and 109, respectively. The chirality of the glycerol unit does not seem relevant for the antitumor activity (Mollinedo et al., 1997; Samadder et al., 2004). When the γ-hydroxybutenolide moiety instead of the 3-furyl group is present in the sesterterpenoid scaffold, the antitumor activity is significantly enhanced, increasing even two orders of magnitude. For that reason, the γ-hydroxybutenolide fragments together with the bioconjugation are the highlighted structural frameworks of this family of molecules (106, 107, 109, 111, and 113). Although the attachment position of the sesterterpenoid fragment in glycerol does not seem very important in terms of bioactivity, when the sesterterpenoid is attached at the sn2 position, the activity is slightly better compared to the sn1 substitution.

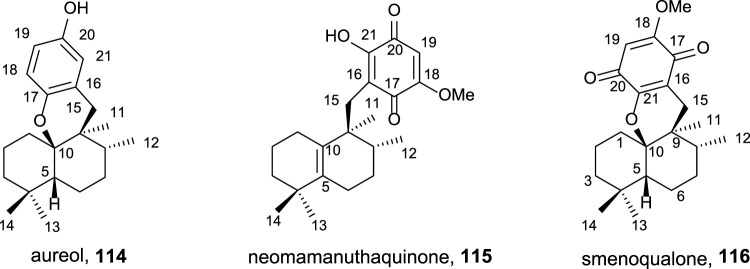

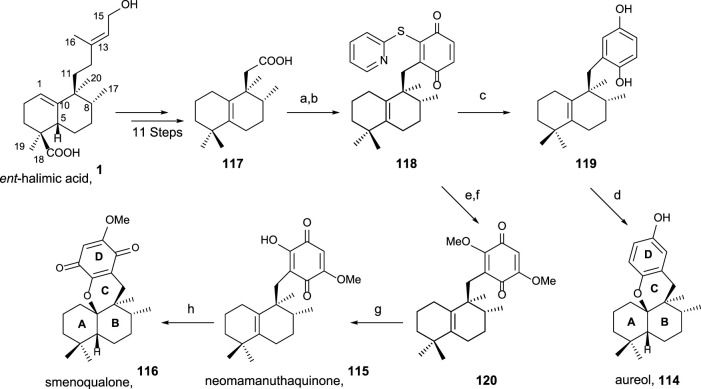

3.4 Synthesis of sesquiterpene quinone/hydroquinone

The interest of these secondary metabolites (Figure 10) showing quinone/hydroquinone frameworks with drimane or rearranged drimane skeleton lies, mainly, in their biological activities and have been widely studied for this purpose (Capon, 1995; Marcos et al., 2010).

FIGURE 10.

Natural sesquiterpene–quinone/hydroquinone.

As antitumor agents, they show cytotoxicity in cancer cell lines such as HeLa, A549, HCT, KB16, P388, and Ehrlich cells, among others; moreover, antiviral, cytotoxic, hemolitic, anti-inflamatory, antiproliferative, antifeedant, antiplasmodial, antimalarial, cardiotonic antituberculosis, and antimicrobiane properties are also described. The biological assays studying the enzymatic inhibition have demonstrated the capability of different quinone/hydroquinone natural products to inhibit DNA topoisomerase I and II, tyrosine kinase, Ca2+/K+ ATPase, PI3 kinase, and PTP1B as well as interleukin-8 dissociation of its receptors.

Using ent-halimic acid 1 as a starting material, different natural products (114–116) showing drimane or rearranged drimane skeleton have been synthesized (Talpir et al., 1994; Kurata et al., 1996; Fraga, 2003). The synthesis afforded for these compounds is shown in Scheme 7 and consists in the following key-steps: degradation of the side chain and C-18 reduction to obtain the tetranor intermediate 117; ring-D coupling and functionalization; and finally, cyclization if needed for ring C formation.

SCHEME 7.

Synthesis of 114–116 from ent-halimic acid 1. (a) 2-mercaptopyridine N-oxide, DCC, DCM, rt, 16 h, and darkness; (b) p-benzoquinone, DCM, hν 500W, 0°C, 2 h, and 65% from 117; (c) Ni-Raney, EtOH, rt, 5 min, and 99%; (d) BF3·Et2O, DCM, −50°C→−5°C, 2 h, and 60%; (e) MeONa, THF, −20°C, 10 min, and 70%; (f) NaOMe, MeOH, −20°C→2°C, and 3 h; (g) HClO4 60%, THF, rt, 4 h, and 70%; (h) p-TsOH, C6H6, reflux, and 30 min.

The transformation of ent-halimic acid 1 into tetranorhalimane 117 takes place in 11 steps with good overall yield (Scheme 7). Thiopyridine quinone 118 is prepared by the Barton decarboxylation and rearrangement. Quinone 118 is an intermediate for the synthesis of aureol 114 and the tri and tetracyclic quinones 115 and 116, respectively. For the synthesis of aureol 114 from 118, two steps are required: first, the reduction to hydroquinone 119 and then the cyclization in acidic medium, accessing aureol 114 in this way. On the other hand, the addition of two equivalents of sodium methoxide in two steps yield 120 that can be transformed into neomamanuthaquinone 115 by acidic hydrolysis with HClO4. Finally, menoqualone 116 is synthesized from 115 by reaction with p-TsOH, promoting its cyclization and ring-C formation.

3.5 Sesqui- and diterpene alkaloids

The use of ent-halimic acid 1 as a starting material for sesqui- and diterpene alkaloids has been applied for the preparation of 7,9-dialkylpurines (agelasine C) as well as di- and sesquiterpenyl indoles.

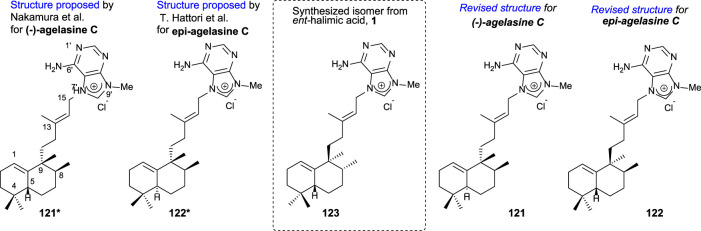

3.5.1 Synthesis of agelasine C

Agelasines are a diterpene alkaloid group isolated as 7,9-dialkylpurine salts from Agelas spp. marine sponges (Rosemeyer, 2004).

In particular, agelasine C (Figure 11) is one of the first four known agelasines isolated by Nakamura et al. (1984) from an Okinawan sea sponge of genus Agelas. The biological studies of (-)-agelasine C showed a high activity inhibiting Na+/K+ ATPase and antimicrobial activities.

FIGURE 11.

Initially proposed structures for agelasine C and epi-agelasine C as well as the revised structures corrected due to the synthesis of 123 from ent-halimic acid, whose absolute configurations were known.

Later on, Hattori et al. (1997) isolated epi-agelasine C 112 from marine sponge Agelas mauritania as an antifouling active agent against macroalgae.

The comparison of the spectral data of compounds 121* and 122* with those of 123 suggested to correct the initially proposed structures to the revised structures (121 and 122) appearing in Figure 11.

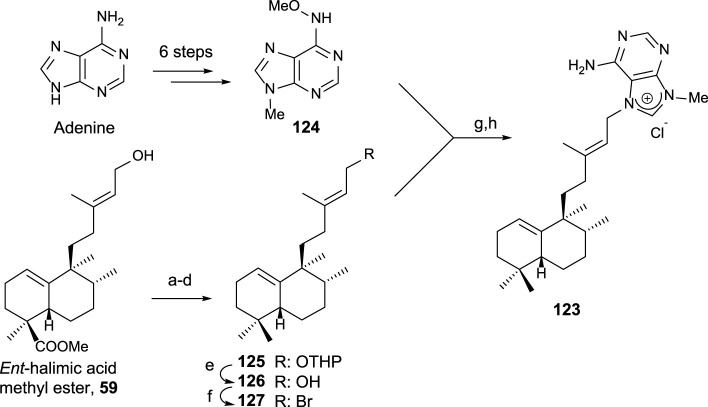

Due to the interest on the biological properties of natural agelasine C and epi-agelasine C, the synthesis of 123 analog was carried out (Marcos et al., 2005a). The synthetic strategy used for accessing this meroterpenoid consists of the preparation of the diterpene fragment functionalized with bromine and then coupling with the purine derivative (Scheme 8).

SCHEME 8.

(a) DHP, p-TsOH, and C6H6 (98%); (b) LAH, Et2O, 0°C, and then rt (99%); (c) TPAP and NMO (94%); (d) diethylene glycol, NH2NH2·H2O, KOH, and 175°C–230°C (81%); (e) p-TsOH and MeOH (81%); (f) CBr4, PPh3, and DCM (76%); (g) DMA and 50°C; (h) Zn, MeOH, H2O, and AcOH (13% two steps).

3.5.2 Synthesis of sesquiterpenyl indoles

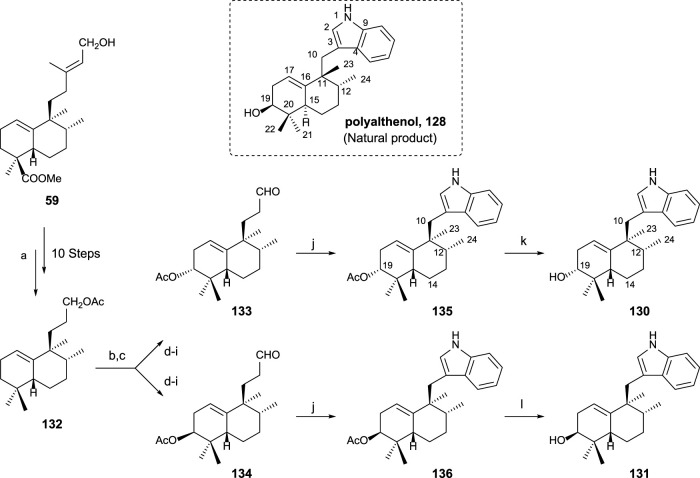

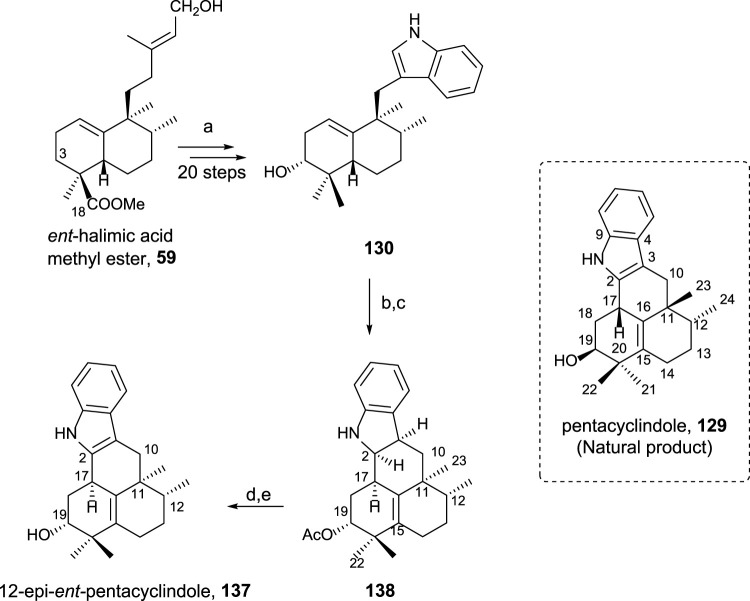

Terpenyl indoles are natural meroterpenes composed of indole alkaloids and terpenoids (Marcos et al., 2013a). Among these natural products, sesquiterpenyl indoles are a small group of natural occurring products of great interest due to their variety of biological properties, such as anticancer, antibacterial, or anti-HIV (Williams et al., 2010; Marcos et al., 2013a). The first sesquiterpenyl indole described was polyalthenol 128, isolated in 1976. After that, different natural products have been identified as sesquiterpenyl indoles, but pentacyclindole 129, isolated from G. suaveolens roots, was a new natural product showing a novel framework. Both natural product structures, 128 and 129, were corroborated as well as the absolute configuration determined by synthesis using ent-halimic acid 1 as a starting material, whose synthetic routes are described in the following section.

3.5.2.1 Synthesis of 12-epi-polyalthenol

In order to confirm the structure of polyalthenol 128, the synthesis of 130 and 131 was carried out (Marcos et al., 2012).

The synthesis of sesquiterpenyl indoles 130 and 131, analogs of polyalthenol (Scheme 9), required the following transformations: preparation of trinorderivative 132; C-3 functionalized intermediates 133 and 134; and finally, indole formation (135 and 136) plus alkaline hydrolysis (130 and 131). Those transformations are presented in Scheme 9.

SCHEME 9.

Synthesis of (-)-12-epi-polyalthenol 130 and analogs: (a) Ref Marcos et al. (2003b) and Marcos et al. (2012). (b) Na2CrO4, NaOAc, Ac2O, AcOH, C6H6, 55°C, and overnight; (c) Mn(OAc)3·2H2O, C6H6, and Dean–Stark 130°C; (d) 1,2-ethanedithiol, BF3·Et2O, 0°C, and overnight; (e) 10% KOH/MeOH, and 24 h; (f) Ni-Raney, EtOH, 50°C, and 1 h; (g) Ac2O, Py, and overnight; (h) Na2CO3 0.7%, MeOH, 2 h, and rt; (i) TPAP, NMO, molecular sieves 4 Å, rt, and 10 min (eight steps from 132: 10% 133 and 12% 134); (j) phenylhydrazine, AcOH, rt, 2 h, then 130°C, 2 h, 135: 91%, and 136: 82%; (k) K2CO3 3%, MeOH, rt, 24 h, and 85%; (l) 10% NaOH/MeOH, rt, 24 h, and 92%.

By the synthesis of both epimers at C19, that stereocenter was easily determined compared with polyalthenol. 130 is the one that showed a similar NMR pattern for the signal corresponding to C19. The comparison of the spectroscopic data allowed to conclude that 130 is a C12 epimer of polyalthenol. That fact, together with the opposite rotatory power shown by these molecules led to define 130 as (-)-12-epi-ent-polyalthenol, confirming the structure of the natural product 128 as a halimane-skeleton derivative of the normal series, and, in consequence, 130 is 12-epi-ent-polyalthenol.

The biological studies of 130, 131, 135, and 136 were performed, where these compounds showed significant antitumor and antiproliferative activities against three cancer cell lines (A549, HL-60, and MCF-7).

3.5.2.2 Synthesis of 12-epi-ent-pentacyclindole 137

Pentacyclindole is a unique natural product due to its structure, being the only natural product known with its pentacyclic framework. The synthesis of its 12-epi diastereoisomer using ent-halimic acid uses the previously synthesized indolederivative 130 as an intermediate (Scheme 10). The cyclization bonding C-2 and C-17 in this biomimetic synthetic route can be considered the key step in the preparation of pentacyclindole analogs. Pentacyclindoles 129 and 137 are epimers at C-12, and by synthesizing 137 from ent-halimic acid 1, which is carried out with excellent yields, the absolute configuration of 129 was possible to be established (Marcos et al., 2013b).

SCHEME 10.

(a) Ref Marcos et al. (2012); (b) Ac2O, Pyr, rt, and 20 h (99%); (c) HI 57%, C6H6, 85°C, and 75 min (93%); (d) TPAP, NMO, and 4 Å molecular sieves, DCM, rt, and 15 min (66%); (e) 10% KOH/MeOH, rt, and 3 h (93%).

3.5.2.3 Polyalthenol and pentacyclindole analogs as antitumor compounds

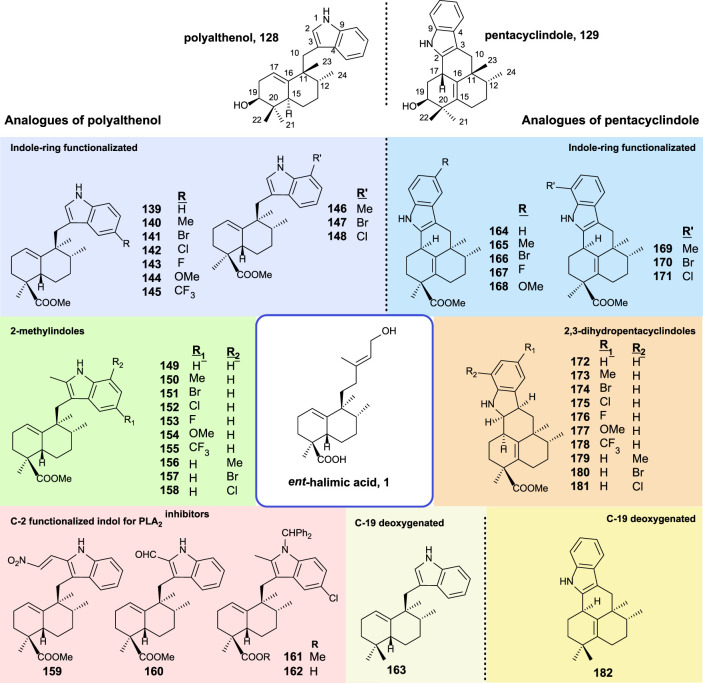

The synthesis and biological activity of polyalthenol and pentacyclindole analogs using similar synthetic routes, as shown for the synthesis of the epimer natural products, have been carried out (Marcos et al., 2014). A summary of all the compounds synthesized from ent-halimic acid 1 is displayed in Figure 12.

FIGURE 12.

Synthesized analogs of polyalthenol 128 and pentacyclindole 129 using ent-halimic acid 1 as a starting material.

The structural modifications introduced in the analogs of polyalthenol can be divided into indole-ring functionalized, 2-methylindoles, C-2 functionalized, and C-19 deoxygenated (Figure 12).

In the case of the synthesis of PLA2 inhibitors, the most remarkable considerations are that the indole C-2 must be functionalized, and other requirements are the carboxylic acid as well as the nitrogen protected with a bulky group.

The antibacterial activity for these compounds is reported. The antiproliferative activities of these analogs have been tested in several tumor cell-lines (A549, HBL-100, HeLa, SW1573, T-47D, and WiDr). All compounds exerted inhibition of cell growth in the range of 1–70 μM. In terms of structural activity, it can be concluded from this study that the presence of substitutions in C-2 decreases the activity slightly (139–148 vs. 149–158). When substitution appears in the benzene ring of the indole either at C-6 or C-8, only the methoxy group enhances the activity (144 and 154). When a methyl group esterifies carboxylic acid in 161 resulting in a total loss of bioactivity, however, the free carboxylic acid in 162 recover the antitumor properties.

In the synthesis of pentacyclindole analogs, the appearing structural mosaics in the synthesized analogs of pentacyclindoles can be divided in the function of the position: indole-ring functionalized, 2,3-dihydrofuran, and C-19 deoxygenated derivatives.

For the pentacyclindole analogs, C-3 unsaturated compounds (164–171) always show better results in the antiproliferative experiments than the corresponding 2,3-dihydropentacyclindole derivatives (172–181). The presence of a methoxy group (168) in the benzene ring results in a little improvement of the antitumor activity in some cell lines. Compounds 168 and 164 showed the best antiproliferative activity of the pentacyclindole analogs with a GI50 in the micromolar range.

4 Conclusion

In this article, we have put together a series of natural halimanes with antitumor activity evaluated against different pharmacological targets and in different cell lines. Structurally, the halimanes that exhibit antitumor activity can be classified into four groups: halimanes with acyclic side chain, 14,15-furohalimanes, 14,15-halimanolides, and halimane–purine hybrids.

Moreover, we have reviewed the role of ent-halimic acid 1 as a starting material in numerous syntheses of bioactive compounds. This is a key aspect of this compound that confers it great importance, as it can be obtained easily from the extracts of Halimium viscosum, reducing time and effort for the obtention of more complex structures. Some of them, like the terpene–purine hybrids or the bioconjugates with antitumor lipids (edelfosine) or PUFAs, show promising results as cytotoxic and antitumor compounds, and more studies should be made to improve the bioactivities and understand the antitumor mechanism.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledged the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain, Junta de Castilla y León, and Universidad de Salamanca for their support. IT thanks FSE (European Social Fund) and Junta de Castilla y León for his grant and AR thanks the Ministerio de Educación and Ministerio de Universidades (Margarita Salas) of Spain for their grants.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain (PID2020-118303GB-I00/MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033), Junta de Castilla y León (UIC 21, SA076P20), and the Universidad de Salamanca (Programa Propio I, 2022).

Author contributions

IM, DD, and RM contributed to the conception and design of the review. AR, IT, RM, DD, and IM consulted the literature. IM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AR and IT wrote sections of the manuscript, made corrections to the first draft, and wrote the final draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abdel-Kader M., Berger J. M., Slebodnick C., Hoch J., Malone S., Wisse J. H., et al. (2002). Isolation and absolute configuration of ent-halimane diterpenoids from hymenaea courbaril from the Suriname rain forest. J. Nat. Prod. 65, 11–15. 10.1021/np0103261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller J., Mihci G., Martin M.-T., Gallard J.-F., Menou J.-L., Boury-Esnault N., et al. (2008). Agelasines J, K, and L from the Solomon islands marine sponge Agelas cf. mauritiana. J. Nat. Prod. 71, 1451–1454. 10.1021/np800212g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blunt J. W., Copp B. R., Munro M. H., Northcote P. T., Prinsep M. R. (2003). Marine natural products. Nat. Product. Rep. 20, 1–48. 10.1039/b207130b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukouvalas J., Lachance N. (1998). A mild, efficient and general method for the synthesis of trialkylsilyl (Z)-4-Oxo-2-alkenoates and γ-hydroxybutenolides. Synlett 1998, 31–32. 10.1055/s-1998-1574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M. O., Webb N. L., Anthony F. H., Devanesan P., Witman P. A., Hemamalini S., et al. (2001). Tumor targeting by covalent conjugation of a natural fatty acid to paclitaxel. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 3229–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohm D., Metzger S., Bhargava A., Müller O., Lieb F., Waldmann H. (2002a). Natural products are biologically validated starting points in structural space for compound library development: Solid-phase synthesis of dysidiolide-derived phosphatase inhibitors this research was supported by the fonds der Chemischen industrie and the bayer AG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohm D., Philippe N., Metzger S., Bhargava A., Müller O., Lieb F., et al. (2002b). Solid-phase synthesis of dysidiolide-derived protein phosphatase inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13171–13178. 10.1021/ja027609f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohm D., Waldmann H. (1998). Stereoselective synthesis of the core structure of the protein phosphatase inhibitor dysidiolide. Tetrahedron Lett. 39, 3995–3998. 10.1016/s0040-4039(98)00702-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capon R. J. (1995). “Marine sesquiterpene/quinones,” in Studies in natural products chemistry. Editor Atta Ur R. (Netherlands: Elsevier; ), 289–326. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C.-H., Chung H.-M., Hwang T.-L., Lu M.-C., Wen Z.-H., Kuo Y.-H., et al. (2012). Echinoclerodane A: A new bioactive clerodane-type diterpenoid from a gorgonian coral Echinomuricea sp. Molecules 17, 9443–9450. 10.3390/molecules17089443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M. S., Pedersen P. J., Andresen T. L., Madsen R., Clausen M. H. (2010). Isomerization of all-(E)-Retinoic acid mediated by carbodiimide activation – synthesis of ATRA ether lipid conjugates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 719–724. 10.1002/ejoc.200901128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H.-M., Hu L.-C., Yen W.-H., Su J.-H., Lu M.-C., Hwang T.-L., et al. (2012). Echinohalimane A, a bioactive halimane-type diterpenoid from a formosan gorgonian Echinomuricea sp. (plexauridae). Mar. Drugs 10, 2246–2253. 10.3390/md10102246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J., Roberts B. E. (1997). Total synthesis of dysidiolide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 12425–12431. 10.1021/ja973023v [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas C., Pérez M., Martín M. J., Chicharro J. L., Fernández-Rivas C., Flores M., et al. (2000). Synthesis of ecteinascidin ET-743 and phthalascidin Pt-650 from cyanosafracin B. Org. Lett. 2, 2545–2548. 10.1021/ol0062502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X., Sun F., Deng K., Lin G., Yin W., Chen H., et al. (2022). Mallotucin D, a clerodane diterpenoid from Croton crassifolius, suppresses HepG2 cell growth via inducing autophagic cell death and pyroptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 14217. 10.3390/ijms232214217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danishefsky S. (2010). On the potential of natural products in the discovery of pharma leads: A case for reassessment. Nat. Product. Rep. 27, 1114–1116. 10.1039/c003211p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pascual Teresa J., Urones J. G., Basabe P., Carrillo H., Muñoz M. a. G., Marcos I. S. (1985). Diterpenoids of halimium viscosum. Phytochemistry 24, 791–794. 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)84896-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Pascual Teresa J., Urones J. G., Marcos I. S., Martín D. D., Alvarez V. M. (1986). Labdane diterpenoids from Halimium viscosum. Phytochemistry 25, 711–713. 10.1016/0031-9422(86)88029-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demeke D., Forsyth C. J. (2000). Novel total synthesis of the anticancer natural product dysidiolide. Org. Lett. 2, 3177–3179. 10.1021/ol006376z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein J. W. (2000). Cdc25 as a potential target of anticancer agents. Investig. New Drugs 18, 149–156. 10.1023/a:1006377913494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathi-Afshar R., Allen T. M. (1988). Biologically active metabolites from Agelas mauritiana. Can. J. Chem. 66, 45–50. 10.1139/v88-006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner D. J. (2001). Marine natural products. Nat. Product. Rep. 18, 1R–49R. 10.1039/b006897g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A., Ciavatta M. L., Cimino G. (1998). Cladocoran A and B: Two novel γ-hydroxybutenolide sesterterpenes from the Mediterranean coral Cladocora cespitosa. J. Org. Chem. 63, 2845–2849. 10.1021/jo971586j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraga B. M. (2003). Natural sesquiterpenoids. Nat. Product. Rep. 20, 392–413. 10.1039/b208084m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajate C., Mollinedo F. (2002). Biological activities, mechanisms of action and biomedical prospect of the antitumor ether phospholipid ET-18-OCH3 (edelfosine), A proapoptotic agent in tumor cells. Curr. Drug Metab. 3, 491–525. 10.2174/1389200023337225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennari C., Vulpetti A., Donghi M., Mongelli N., Vanotti E. (1996). Semisynthesis of taxol: A highly enantio- and diastereoselective synthesis of the side chain and a new method for ester formation at C13 using thioesters. Angewandte Chemie Int. Ed. Engl. 35, 1723–1725. 10.1002/anie.199617231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Mesón A., Roncero A. M., Tobal I. E., Basabe P., Díez D., Mollinedo F., et al. (2016). Synthesis of bioconjugate sesterterpenoids with phospholipids and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Molecules 21, 47. 10.3390/molecules21010047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekera S. P., Mccarthy P. J., Kelly-Borges M., Lobkovsky E., Clardy J. (1996). Dysidiolide: A novel protein phosphatase inhibitor from the caribbean sponge Dysidea etheria de Laubenfels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 8759–8760. 10.1021/ja961961+ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hara N., Asaki H., Fujimoto Y., Gupta Y. K., Singh A. K., Sahai M. (1995). Clerodane and ent-halimane diterpenes from polyalthia longifolia. Phytochemistry 38, 189–194. 10.1016/0031-9422(94)00583-f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori T., Adachi K., Shizuri Y. (1997). New agelasine compound from the marine sponge Agelas mauritiana as an antifouling substance against macroalgae. J. Nat. Prod. 60, 411–413. 10.1021/np960745b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Jaafari M. R., Szoka F. C. (2009). Disterolphospholipids: Nonexchangeable lipids and their application to liposomal drug delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 4146–4149. 10.1002/anie.200900111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Szoka F. C. (2008). Sterol-modified phospholipids: Cholesterol and phospholipid chimeras with improved biomembrane properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15702–15712. 10.1021/ja8065557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara Y., Takeya K., Hitotsuyanagi Y., Morita H., Okuyama S., Suganuma M., et al. (1992). Cajucarinolide and isocajucarinolide: Anti-inflammatory diterpenes from Croton cajucara. Planta Med. 58, 549–551. 10.1055/s-2006-961547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung M. E., Berliner J. A., Koroniak L., Gugiu B. G., Watson A. D. (2008). Improved synthesis of the epoxy isoprostane phospholipid PEIPC and its reactivity with amines. Org. Lett. 10, 4207–4209. 10.1021/ol8014804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgis G., Foley D. J., Laraia L., Brakmann S., Waldmann H. (2021). Pseudo natural products—chemical evolution of natural product structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 15837–15855. 10.1002/ange.202016575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston D. G. I., Jagtap P. G., Yuan H., Samala L. (2002). “The chemistry of taxol and related taxoids,” in Progress in the chemistry of organic natural products/fortschritte der Chemie organischer naturstoffe. Editors Herz W., Falk H., Kirby G. W. (Vienna: Springer; ), 53–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K., Waldmann H. (2009). Synthesis of natural product inspired compound collections. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3224–3242. 10.1002/anie.200803437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata K., Taniguchi K., Suzuki M. (1996). Cyclozonarone, a sesquiterpene-substituted benzoquinone derivative from the Brown alga Dictyopteris undulata. Phytochemistry 41, 749–752. 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00651-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova L., Chen J., Sun L., Wu X., Pepe A., Veith J. M., et al. (2006). Syntheses and evaluation of novel fatty acid-second-generation taxoid conjugates as promising anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 974–977. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.10.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampkowski J. S., Villa J. K., Young T. S., Young D. D. (2015). Development and optimization of glaser–hay bioconjugations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9475–9478. 10.1002/ange.201502676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Sun X., Yin W., Zhan Z., Tang Q., Wang W., et al. (2021). Crassifolins Q−W: Clerodane diterpenoids from Croton crassifolius with anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenesis activities. Front. Chem. 9, 733350. 10.3389/fchem.2021.733350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linderoth L., Peters G. H., Madsen R., Andresen T. L. (2009). Drug delivery by an enzyme-mediated cyclization of a lipid prodrug with unique bilayer-formation properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 1855–1858. 10.1002/ange.200805241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo P., Yu Q., Liu S.-N., Xia W.-J., Fang Y.-Y., An L.-K., et al. (2017). Diterpenoids with diverse scaffolds from Vitex trifolia as potential topoisomerase I inhibitor. Fitoterapia 120, 108–116. 10.1016/j.fitote.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslovskaya L. A., Savchenko A. I., Gordon V. A., Reddell P. W., Pierce C. J., Boyle G. M., et al. (2019). New halimanes from the Australian rainforest plant Croton insularis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 1058–1060. 10.1002/ejoc.201801548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson S. R., Sepp-Lorenzino L., Rosen N., Danishefsky S. J. (1998). A concise total synthesis of dysidiolide through application of a dioxolenium-mediated Diels-Alder reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 1615–1616. 10.1021/ja9740428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson C. D., Gudmundsdottir A. V., Haraldsson G. G. (2011). Chemoenzymatic synthesis of a focused library of enantiopure structured 1-O-alkyl-2,3-diacyl-sn-glycerol type ether lipids. Tetrahedron 67, 1821–1836. 10.1016/j.tet.2011.01.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I., Conde A., Moro R., Basabe P., Diez D., Urones J. (2010). Quinone/hydroquinone sesquiterpenes. Mini-Reviews Org. Chem. 7, 230–254. 10.2174/157019310791384128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Conde A., Moro F. R., Basabe P., Díez D., Mollinedo F., et al. (2008). Synthesis of an ent-Halimanolide from ent-Halimic Acid. Molecules 13, 1120–1134. 10.3390/molecules13051120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Escola M. A., Moro R. F., Basabe P., Diez D., Sanz F., et al. (2007). Synthesis of novel antitumoural analogues of dysidiolide from ent-halimic acid. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 15, 5719–5737. 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., García N., Sexmero M. J., Basabe P., Díez D., Urones J. G. (2005a). Synthesis of (+)-agelasine C. A structural revision. Tetrahedron 61, 11672–11678. 10.1016/j.tet.2005.09.049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Moro R. F., Costales I., Basabe P., Díez D., Gil A., et al. (2014). Synthesis and biological activity of polyalthenol and pentacyclindole analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 73, 265–279. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Moro R. F., Costales I., Basabe P., Díez D., Mollinedo F., et al. (2013b). Biomimetic synthesis of an antitumour indole sesquiterpene alkaloid, 12-epi-ent-pentacyclindole. Tetrahedron 69, 7285–7289. 10.1016/j.tet.2013.06.075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Moro R. F., Costales I., Basabe P., Díez D., Mollinedo F., et al. (2012). Synthesis of 12-epi-ent-polyalthenol an antitumour indole sesquiterpene alkaloid. Tetrahedron 68, 7932–7940. 10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Moro R. F., Costales I., Basabe P., Díez D. (2013a). Sesquiterpenyl indoles. Nat. Product. Rep. 30, 1509–1526. 10.1039/c3np70067d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Pedrero A. B., Sexmero M. J., Diez D., Basabe P., García N., et al. (2003a). Synthesis of bioactive sesterterpenolides from ent-halimic acid 15-Epi-ent-cladocoran A and B. J. Org. Chem. 68, 7496–7504. 10.1021/jo034663l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Pedrero A. B., Sexmero M. J., Diez D., Basabe P., Hernández F. A., et al. (2002). Synthesis and absolute configuration of the supposed structure of cladocoran A and B. Synlett 2002, 0105–0109. 10.1055/s-2002-19318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Pedrero A. B., Sexmero M. J., Diez D., Basabe P., Hernández F. A., et al. (2003b). Synthesis and absolute configuration of three natural ent-halimanolides with biological activity. Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 369–372. 10.1002/chin.200315182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos I. S., Pedrero A. B., Sexmero M. J., Diez D., García N., Escola M. A., et al. (2005b). Synthesis of ent-Halimanolides from ent-Halimic Acid. Synthesis 2005, 3301–3310. 10.1055/s-2005-918475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslovskaya L. A., Savchenko A. I., Krenske E. H., Chow S., Holt T., Gordon V. A., et al. (2020). EBC-232 and 323: A structural conundrum necessitating unification of five in silico prediction and elucidation methods. Chem. – A Eur. J. 26, 11862–11867. 10.1002/chem.202001884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaoka H., Yamanishi M., Kajiwara Y., Yamada Y. (2003). Total synthesis of cladocorans A and B: A structural revision. J. Org. Chem. 68, 3476–3479. 10.1021/jo020743y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollinedo F., Fernández-Luna J. L., Gajate C., Martín-Martín B., Benito A., Martínez-Dalmau R., et al. (1997). Selective induction of apoptosis in cancer cells by the ether lipid ET-18-OCH3 (edelfosine): Molecular structure requirements, cellular uptake, and protection by bcl-2 and bcl-XL. Cancer Res. 57, 1320–1328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollinedo F., Gajate C., Martin-Santamaria S., Gago F. (2004). ET-18-OCH3 (edelfosine): A selective antitumour lipid targeting apoptosis through intracellular activation of fas/CD95 death receptor. Curr. Med. Chem. 11, 3163–3184. 10.2174/0929867043363703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H., Wu H., Ohizumi Y., Hirata Y. (1984). Agelasine-A, -B, -C and -D, novel bicyclic diterpenoids with a 9-methyladeninium unit possessing inhibitory effects on na,K-atpase from the okinawa sea sponge sp.1). Tetrahedron Lett. 25, 2989–2992. 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)81345-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu T., Ito S., Kawashima T. (1981). Mallotucin-C and mallotucin-D, 2 diterpenic lactones from Mallotus repandus. Heterocycles 15, 241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. (2012). Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 Years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 311–335. 10.1021/np200906s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. (2007). Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J. Nat. Prod. 70, 461–477. 10.1021/np068054v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilo A., Allan M., Brogioni B., Proietti D., Cattaneo V., Crotti S., et al. (2014). Tyrosine-directed conjugation of large glycans to proteins via copper-free click chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 25, 2105–2111. 10.1021/bc500438h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson I., Anderson E. A. (2005). The renaissance of natural products as drug candidates. Science 310, 451–453. 10.1126/science.1116364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen P. J., Adolph S. K., Andresen T. L., Madsen M. W., Madsen R., Clausen M. H. (2010a). Prostaglandin phospholipid conjugates with unusual biophysical and cytotoxic properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 4456–4458. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.06.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen P. J., Adolph S. K., Subramanian A. K., Arouri A., Andresen T. L., Mouritsen O. G., et al. (2010b). Liposomal formulation of retinoids designed for enzyme triggered release. J. Med. Chem. 53, 3782–3792. 10.1021/jm100190c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen P. J., Christensen M. S., Ruysschaert T., Linderoth L., Andresen T. L., Melander F., et al. (2009). Synthesis and biophysical characterization of chlorambucil anticancer ether lipid prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 52, 3408–3415. 10.1021/jm900091h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen P. J., Viart H. M. F., Melander F., Andresen T. L., Madsen R., Clausen M. H. (2012). Synthesis of tocopheryl succinate phospholipid conjugates and monitoring of phospholipase A2 activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 3972–3978. 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z., Chang Y., Fan J., Ji W., Su C. (2021). Phospholipase A2 superfamily in cancer. Cancer Lett. 497, 165–177. 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piers E., Caillé S., Chen G. (2000). A formal total synthesis of the sesterterpenoid (±)-Dysidiolide and approaches to the syntheses of (±)-6-Epi-(±)-15-Epi-and (±)-6, 15-bisepidysidiolide. Org. Lett. 2, 2483–2486. 10.1021/ol0061541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu M., Jin J., Zhou L., Zhou W., Liu Y., Tan Q., et al. (2018). Diterpenoids from Croton crassifolius include a novel skeleton possibly generated via an intramolecular [2+2]-photocycloaddition reaction. Phytochemistry 145, 103–110. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodilla J. M. L., De Mendonça D. I. M., Urones J. G., Moro R. F. (1998). Hydroxylated diterpenoids from Halimium viscosum. Phytochemistry 49, 817–822. 10.1016/s0031-9422(98)00168-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodilla J. M. L., Mendonça D. I. D., Ismael M. I. G., Figueiredo J. A., Silva M. L. A., Lopes E. (2001). BI- and tricyclic diterpenoids from halimium viscosum. Nat. Product. Lett. 15, 401–409. 10.1080/10575630108041310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roengsumran S., Pornpakakul S., Muangsin N., Sangvanich P., Nhujak T., Singtothong P., et al. (2004). New halimane diterpenoids from Croton oblongifolius. Planta Med. 70, 87–89. 10.1055/s-2004-815466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Hernández L. L., Merino-Montiel P., Montiel-Smith S., Meza-Reyes S., Vega-Báez J. L., Abasolo I., et al. (2015). Diosgenin-based thio(seleno)ureas and triazolyl glycoconjugates as hybrid drugs. Antioxidant and antiproliferative profile. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 99, 67–81. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncero A. M., Tobal I. E., Moro R. F., Díez D., Marcos I. S. (2018). Halimane diterpenoids: Sources, structures, nomenclature and biological activities. Nat. Product. Rep. 35, 955–991. 10.1039/c8np00016f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosemeyer H. (2004). The chemodiversity of purine as a constituent of natural products. Chem. Biodivers. 1, 361–401. 10.1002/cbdv.200490033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudi A., Aknin M., Gaydou E., Kashman Y. (2004). Asmarines I, J, and K and nosyberkol: Four new compounds from the marine sponge raspailia sp. J. Nat. Prod. 67, 1932–1935. 10.1021/np049834b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samadder P., Bittman R., Byun H.-S., Arthur G. (2004). Synthesis and use of novel ether phospholipid enantiomers to probe the molecular basis of the antitumor effects of alkyllysophospholipids: Correlation of differential activation of c-jun NH2-terminal protein kinase with antiproliferative effects in neuronal tumor cells. J. Med. Chem. 47, 2710–2713. 10.1021/jm0302748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez M., Mazzuca M., Veloso M. J., Fernández L. R., Siless G., Puricelli L., et al. (2010). Cytotoxic terpenoids from Nardophyllum bryoides. Phytochemistry 71, 1395–1399. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scio E., Ribeiro A., Alves T. M. A., Romanha A. J., De Souza Filho J. D., Cordell G. A., et al. (2003). Diterpenes from Alomia myriadenia (Asteraceae) with cytotoxic and trypanocidal activity. Phytochemistry 64, 1125–1131. 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00529-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenvi S., Kiran K. R., Kumar K., Diwakar L., Reddy G. C. (2015). Synthesis and biological evaluation of boswellic acid-NSAID hybrid molecules as anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 98, 170–178. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva C. G., Santos Júnior H. M., Barbosa J. P., Costa G. L., Rodrigues F. a. R., Oliveira D. F., et al. (2015). Structure elucidation, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of a halimane isolated from vellozia kolbekii alves (velloziaceae). Chem. Biodivers. 12, 1891–1901. 10.1002/cbdv.201500071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M., Dodo K., Sugimoto Y., Aoyagi Y., Yamada Y., Hashimoto Y., et al. (2000). Synthesis of the novel analogues of dysidiolide and their structure–activity relationship. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 2571–2574. 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00527-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talpir R., Rudi A., Kashman Y., Loya Y., Hizi A. (1994). Three new sesquiterpene hydroquinones from marine origin. Tetrahedron 50, 4179–4184. 10.1016/s0040-4020(01)86712-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J.-L., Yao G.-D., Wang Y.-X., Gao P.-Y., Wang D., Li L.-Z., et al. (2017). Cytotoxic clerodane diterpenoids from Croton crassifolius. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 27, 1237–1242. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truax N. J., Romo D. (2020). Bridging the gap between natural product synthesis and drug discovery. Nat. Product. Rep. 37, 1436–1453. 10.1039/d0np00048e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urones J. G., De Pascual Teresa J., Marcos I. S., Díez Martín D., Martín Garrido N., Guerra R. A. (1987). Diterpenoids from halimium viscosum. Phytochemistry 26, 1077–1079. 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)82353-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchi L., Araújo T. G., Azevedo F. V. P. D. V., Mota S. T. S., Ávila V. D. M. R., Ribeiro M. A., et al. (2021). Phospholipase A2 drives tumorigenesis and cancer aggressiveness through its interaction with annexin A1. Cells 10, 1472. 10.3390/cells10061472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-J., Chung H. Y., Zhang Y.-B., Li G.-Q., Li Y.-L., Huang W.-H., et al. (2016). Diterpenoids from the roots of Croton crassifolius and their anti-angiogenic activity. Phytochemistry 122, 270–275. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. B., Hu J.-F., Olson K. M., Norman V. L., Goering M. G., O’neil-Johnson M., et al. (2010). Antibiotic indole sesquiterpene alkaloid from Greenwayodendron suaveolens with a new natural product framework. J. Nat. Prod. 73, 1008–1011. 10.1021/np1001225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. M., Danishefsky S. J. (2006). Small molecule natural products in the discovery of therapeutic agents: The synthesis connection. J. Org. Chem. 71, 8329–8351. 10.1021/jo0610053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Zhou T., Zhang S.-W., Zhang X.-H., Xuan L.-J. (2009). Cytotoxic terpenoids from the fruits of vitex trifolia L. Planta Med. 75, 367–370. 10.1055/s-0028-1112211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.-M., Wu D.-G., Liu X.-K. (2010). Anticancer activity of diterpenoids from amoora ouangliensis and amoora stellato-squamosa. Z. für Naturforsch. C 65, 39–42. 10.1515/znc-2010-1-207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q.-Q., Tang S., Song W.-B., Wang W.-Q., Huang M., Xuan L.-J. (2017). Crassins A–H, diterpenoids from the roots of Croton crassifolius. J. Nat. Prod. 80, 254–260. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio-Vazquez R., Ivanova S., Moreno M., Hernandez-Alvarez M. I., Giralt E., Bidon-Chanal A., et al. (2015). A new quinoxaline-containing peptide induces apoptosis in cancer cells by autophagy modulation. Chem. Sci. 6, 4537–4549. 10.1039/c5sc00125k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou M.-F., Hu R., Liu Y.-X., Fan R.-Z., Xie X.-L., Yin S. (2020). Two highly oxygenated nor-clerodane diterpenoids from Croton caudatus. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 22, 927–934. 10.1080/10286020.2020.1751618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]