Abstract

This study adopts a conceptual research approach to examine recent developments in Digital Holocaust Memory regarding the use of digital technology for teaching and learning about the Holocaust. In order to promote heritage education, this paper proposes a conceptual framework that links the field of Digital Holocaust Memory with the approach of learning ecologies. A key element of this framework is the idea that technological advances can enhance learning by fostering participatory cultures and empowering users. The aim of this paper is to provide a deeper understanding of how digital technology can be used to create meaningful learning experiences about the Holocaust, and to propose a theoretical lens based on an ecological approach to learning. In addition, the study aims to present a framework that can assist students in developing their own Holocaust-related learning experiences. The focus is on understanding Holocaust remembrance and learning as complex, multidirectional and multi-layered phenomena, influenced by the specific learning environment, the use of digital technology, and historical, political and cultural contexts. By taking into account the specific cultural, social and economic characteristics of the learning environment, this framework provides a comprehensive approach to designing educational interventions that meet the needs of learners, teachers and stakeholders.

Keywords: Digital holocaust memory, Holocaust education, Learning ecologies, Lifelong learning, Digital technologies, Social media

1. Introduction

The Holocaust and the Second World War are two of the most significant collective memories that continue to shape Western and European identity [1]. In the early 1990s, a European dimension of remembrance emerged and developed, within which the memory of the destruction of European Jewry became increasingly prominent [2,3]. There has been a notable shift in the field of memory and identity politics, from a focus on nation-states wielding symbolic power in their management to the emergence of local memory construction and increased civil society participation [4]. At the same time, the concept of transnational memory [5] has gained prominence, with international organisations actively involved in its design [6].

However, despite efforts to make Holocaust memory increasingly global and transnational, Holocaust remembrance remains deeply shaped by national contexts [7,8]. Indeed, in Holocaust cultural institutions, local and global Holocaust memory are intertwined in complex ways. National contexts often shape the ways in which Holocaust memories are presented and understood [9], as a country's national narrative and politics can influence the ways in which the Holocaust is remembered and communicated at the educational level [10]. Local and global memories of the Holocaust can also be intertwined, as local contexts can be used to inform global understandings of the Holocaust especially in digital environments [11]. This has profound implications for how people in different countries learn about and understand the Holocaust, in terms of their interests and motivations, as well as the resources and activities they use to acquire knowledge about the subject.

Although Holocaust remembrance has played an important role in the last decade through a proliferation of public activities related to the memory of the Second World War, spaces of historical memory have also undergone profound changes [4]. Today we face a complex situation in which the need for better education about the Holocaust is complicated by a growing awareness of ignorance and distortion of the subject, especially in digital environments and social media [10,12]. While Holocaust remembrance and education is experiencing a period of ‘Holocaust fatigue’ [13], there is also a growing number of people who limit or distort historical facts about the Second World War and the Holocaust, or who demonstrate a limited understanding of historical concepts and events [14,15]. A recent survey conducted by the Claims Conference in six countries between 2018 and 20221 examining knowledge and perceptions of the Holocaust around the world, found that while the overwhelming majority of respondents believe it is important to continue teaching about the Holocaust, there are alarming numbers of misconceptions and lack of knowledge about the topic, particularly among younger generations.2

On a more positive note, other surveys have found that Gen Z tends to be much more interested in the Nazi era than their parents, drawing parallels between today's racism and discrimination and the motivations of the perpetrators [16]. Far from being digitally literate, they also want more “snackable content” or digestible information, and more of a “fusion of digital and analogue” offerings, such as virtual tours of memorials, holograms or chats with contemporary witnesses, podcasts, videos or Twitch.tv that provide access to information.

Similar to how education has been transformed by the widespread use of technology, the rapid development of digital technologies has profoundly changed the nature of Holocaust remembrance and education [[17], [18], [19]]. Holocaust education is increasingly linked to the digital age, from live and virtual survivor testimonies [20] to "serious games" to enhance historical understanding [21], from geomedia-based educational tools [22] to the use of social media in formal and informal learning settings [23]. The digitisation of Holocaust memory and remembrance practices is closely related to this trend [24,25]. However, there is also a lack of clarity about the direction in which Holocaust pedagogy is likely to develop in the digital age [26]. As technological advances have enabled people to access a wide range of information, it can be difficult to determine which information is reliable and educationally relevant, and to develop a coherent pedagogical approach. One of the challenges is to find ways to ensure that the Holocaust is taught in a meaningful and accurate way, while recognising that digital media can be used to spread misinformation or distorted information [10]. This requires a careful balance between providing learners with access to reliable historical and moral resources and teaching them critical thinking skills to assess the accuracy of the information they find, as well as to deal with the ethical implications of the latest developments such as hologram technology and the use of AI and chatbots (e.g., ChatGPT-4).

In order to extend the theoretical elaboration of pedagogical implications related to digital Holocaust memory, this study proposes an educational intervention based on digital technologies using conceptual and empirical approaches of learning ecologies [27]. Taking a learning ecology approach to Holocaust education allows us to view the learning process as an interconnected system of dynamic and mutually influential relationships between physical, social and cultural environments, incorporating digital technologies and diverse learning settings [28]. Thus, by focusing on understanding how learners interact with digital Holocaust remembrance and educational materials, the study provides a framework for examining learning experiences at the individual and collective levels, as well as their impact on learners [29].

The study contributes to a deeper understanding of the complex field of Holocaust education and how it has been hybridised with digital technology. It also explores how digital media can be used to create a more immersive educational experience and engage learners in ways that traditional methods cannot, while at the same time presenting unprecedented challenges. The approach adopted is particularly relevant in dealing with such a complex and sensitive issue, as it takes into account the ecology of learning about the subject across multiple settings and media resources. Indeed, “relationing to the Holocaust" [10] has become one of the most common motifs for expressing political views, social identities and cultural concerns in contemporary society [30]. At the same time, the Holocaust is an ongoing discursive event that is constantly evolving, and the clear distinction between commemorative and non-commemorative memory is becoming less defined [31]. It is therefore a priority to explore how such a discourse can be developed in different settings, using different tools and resources, and influencing people's learning dispositions and processes.

The following sections present the methodological approach adopted, summarise the current state of Holocaust education, introduce the new field of study of Digital Holocaust Memory, and describe the learning ecology approach. Our final contribution includes a set of recommendations for the design of educational and pedagogical interventions based on Holocaust education that take advantage of digital technologies. The methodological approach adopted considers the context of digital technologies and how they can be used in conjunction with Holocaust education to create a meaningful and effective learning experience. This includes consideration of the physical, social and digital environments in which learning takes place, as well as the different types of media used and the potential of digital technologies to support and enhance learning.

2. Methodological approach

Our aim is to establish a link between the knowledge generated within the disciplinary field of media and cultural studies, which has dealt extensively with difficult legacies [32] and Holocaust memory, and the field of education. It is worth noting that recent research [23] has shown that these two subfields primarily rely on different conceptual frameworks. Furthermore, while Holocaust memory is a well-established field of research, there are few studies and insufficient theoretical elaboration on the use of digital technologies for Holocaust education. Given this disparity, our study seeks to bridge the gap and make connections between these fields. We aim to explore the intersection of media and cultural studies with education, focusing on the role of digital technologies in teaching and learning about the Holocaust. In doing so, we aim to contribute to a broader understanding of how digital tools can be effectively integrated into Holocaust education, drawing on the insights and theoretical foundations of both disciplines.

From a methodological perspective, this study applies conceptual research as a methodology that involves observing and analysing existing information without conducting practical experiments [33]. The aim of this approach is to gain a better understanding of the underlying phenomena and to develop new insights and theories that may help to explain the data. Through this approach, researchers are able to take a more holistic view of the phenomenon, analysing it from multiple angles and exploring the numerous factors that contribute to it [34,35]. In a conceptual research framework, the researcher combines previous research with other related studies, assuming that the phenomenon can be explained based on existing research [36]. It systematically explains the actions that need to be taken during the course of the study, using information from available research studies and the perspectives of other researchers on the topic.

We used the theory adaptation model to revise consolidated knowledge by introducing complementary frames of reference in order to present a new perspective on a conceptualisation [37]. The theory adaptation model allows for the analysis of multiple frames of reference and approaches, which can then be used to create a more comprehensive and insightful perspective on established concepts. By understanding the different frames of reference and approaches that exist within a given concept, the model can be used to inform fieldwork and empirical research and to support innovative pedagogical practices.

However, far from being purely speculative, this study also provides preliminary indications of the application of the learning ecology approach to an ecological learning context in relation to a specific setting, namely adult learners’ access to information about the Holocaust on social media. By examining a concrete example, we hope to demonstrate how this approach can enhance our understanding of the complex interplay between learners, technology, social media platforms and the information landscape surrounding the Holocaust.

3. Holocaust education and its complexity

Holocaust education has been defined as “a relatively autonomous social system with certain practices, rules, and institutions, which is constituted by a system of relative positions created by competitive interaction between different agents and thus prone to constant reorganization” [38].3 In this context, curriculum, teacher training, supervision and standardised testing reflect the national aspect, while the individual component comes from students and their teachers, who bring their unique perspectives and values to the classroom. In addition, professional expertise based on educational theories, research, and teachers' identities also influence how the Holocaust is taught [10]. This suggests that each teacher and student has their own understanding of the Holocaust and its meaning, which adds a crucial layer of complexity to Holocaust education. Such individual perspectives play a unique role in shaping a compelling pedagogical intervention. For example, a teacher's personal family background can provide a personal connection to the subject matter, enabling them to inspire students to consider the human stories intertwined with the Holocaust and to reflect on its continuing impact in the present [10].

Despite the lack of consensus on the definition of the field and its precise ontological boundaries, teaching and learning about the Holocaust has gradually developed and become professionalised, institutionalised, and globalised, with the subject being incorporated into formal school programmes through its inclusion in (official) curricula and, increasingly, in teacher training institutions as well as university education faculties [39,40]. Curricula, textbooks, and all non-formal and formal efforts to educate the public about the Holocaust are also part of Holocaust education [[41], [42], [43]]. However, research has also shown that people learn about the history and memory of the Holocaust from a variety of sources, including film, literature, and popular and digital media [44]. These sources provide a way for people to gain knowledge about the subject and understand how it has been remembered and commemorated over the years [45]. As a result, people are likely to develop a wide range of ideas, beliefs, understandings and preconceptions about the topic before learning about it formally in their history classes [46].

To complicate matters further, the Holocaust is subject to different processes of cultural appropriation, which vary depending on the specific geographical context. Western and Eastern European countries have different knowledge and understandings of the Holocaust due to the different events during and after the war [47,48]. At the same time, divisions also exist within and between other European regions, or even within the same country, as European integration fosters more ethnically diverse classrooms and challenges established dominant interpretations, leading to their renegotiation [3,49,50]. As school demographics evolve, it becomes necessary for educators to understand how learners’ backgrounds and experiences influence their perspectives on historical events such as the Holocaust [51]. Such an understanding can help educators develop more effective teaching methods and create more meaningful learning experiences for their students.

Furthermore, it is crucial to recognise that Holocaust education presents significant challenges [52] due to its sensitive nature, encompassing topics that touch on national and historical controversies [53], evoke feelings of shame and discomfort [54], and are rooted in the traumatic experiences, suffering, and violent oppression endured by marginalised groups [49]. Indeed, one of the central debates in Holocaust education revolves around whether the primary goal should be historical knowledge or moral lessons [55]. Some argue for prioritising an understanding of the historical context and events, while others emphasise the moral implications and encourage students to reflect on the consequences of hatred and prejudice [26]. However, it is important to recognise that these approaches are not mutually exclusive and can be combined to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the content[51].

In this regard, it is fundamental to consider the biases, preconceptions, understandings, resources, and relationship to the global context of meanings in which both educators and learners engage with the issues of Holocaust education, as well as the perspectives of individuals throughout the process [46]. As a result, the appropriation of Holocaust knowledge in different learning environments is characterised by agency and subjectivity. Agency is defined as a product of power relations and refers to a wider range of practices, institutions and artefacts, and is understood as a system of meaningful practices that create identities and objects [56]. Agency and subjectivity are central to the incorporation of Holocaust material in learning environments because they allow individuals to construct their own understanding of the subject. Agency allows individuals to make decisions about what information to use and how to use it, and subjectivity allows individuals to make meaning from their experiences with the content. As a result, the acquisition of Holocaust knowledge is characterised by the ability to shape identity and create objects.4

The purpose of the following section is to highlight the potential and opportunities for further reflection and development of the new field of study of Digital Holocaust Memory and its implications for education. This section will focus on the ways in which digital technologies can be used to facilitate the analysis and exploration of the history of the Holocaust and its legacy. It will also explore the potential and challenges of digital tools to engage students and the public in meaningful conversations about the Holocaust and its impact.

4. The educational media ecology of Digital Holocaust Memory

The rise of systemic organisation of online content and user-generated content enabled by Web 2.0 applications has opened up new possibilities for the mediatisation of the past [57] and new means of formulating, reinforcing and challenging its interpretations [[58], [59], [60]]. The concept of "‘virtual Holocaust memory" has been advocated to demonstrate the interconnectedness of digital and non-digital Holocaust memory and to highlight the collaborative nature of contemporary forms of memory, as well as a methodology that can be applied to digital and non-digital projects [61].

Digital Holocaust Memory is seen as a digital phenomenon or an intra-action between a multitude of actors. According to this field of study, it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish between memory, education and research, as they are increasingly intertwined. Furthermore, they have always been involved in the history and development of media, from audio recordings and video to the present day of digital media [62]. Finally, as computational, interface, user and broader cultural environments interact, they become integrated as digital phenomena [60]. From this perspective, digital technologies are shaping new ecologies of memory [59,63] and are contributing to the emergence of new forms of Holocaust commemoration and education [64].

Today, Digital Holocaust Memory encompasses a wide range of projects in museums, archives, corporations, and educational organisations in the USA and Europe. These initiatives include interactive video testimonies, virtual reality films, augmented reality applications, museum installations and online exhibitions, all of which seek to convey the memory of the Holocaust through novel and inventive means [65,66].

Efforts to integrate archival research on the Holocaust, as demonstrated by initiatives such as the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure, have successfully addressed the geographical dispersion of Holocaust-related materials and the challenges faced by historical research due to the fragmented nature of Holocaust documentation [67,68]. On the other hand, mobile and mixed reality technologies offer a unique opportunity to construct individual narratives through active exploration of physical sites associated with Nazi crimes and the Holocaust [69]. These technologies support constructivist educational programmes and facilitate the development of learning activities that encourage personal exploration and understanding of sources [70].

In addition, digital media and teaching strategies related to genocide and the Holocaust are increasingly using interactive 3D digital storytelling to recreate the powerful experience of listening to survivors in person. Through the use of hologram technology, these projects allow visitors to become emotionally engaged and immersed by answering direct questions [20,71]. Other educational projects create digital spaces to facilitate the transition from physical place to virtual space and allow for the exploration of the intrinsic meaning of digital memory cultures. These projects not only enable the (re)discovery of marginalised memory sites, but also provide "glocal" digital access to their histories and structures, drawing attention to their unique characteristics [72].

However, with the growing influence of artificial intelligence and machine learning on Holocaust memory research [73], the ethical implications of using neural networks, holograms or chatbots, such as advanced language models like ChatGPT-4, in the context of memorialising mass atrocities are becoming increasingly complex and warrant thorough examination. The application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to historical narrative and collective memory has sparked an intense debate within memory and Holocaust studies. On the one hand, the development of artificial intelligence in the field of memory institutions, history and testimony is recognised as a new opportunity for historical research and teaching [74]. On the other hand, imaginary tools such as GPThistory, an adaptation of ChatGPT to become a real tool for history production and support of collective memory, pose unprecedented challenges. For example, the scarcity of training data on mass atrocities can potentially affect how AI interprets queries related to these events. The ability to distinguish between human-generated and AI-generated content related to mass atrocities becomes increasingly important. There are also concerns that AI-generated content could be used to spread false information about atrocities [75]. Understanding how search engines [76] and artificial intelligence algorithms [77,78] work for Holocaust content may be helpful in detecting or being aware of deepfakes and the creation of distorted information. Furthermore, in addition to authenticity and ownership [79], users should be aware that sensitivity and respect should guide the design and implementation of these technologies to avoid causing unnecessary distress or retraumatisation, while any use of holograms or chatbots should be accompanied by contextual information and expert guidance to provide a full understanding of the subject. Indeed, it is crucial to avoid relying solely on technology without appropriate historical context, interpretation and critical engagement, which can lead to a loss of empathy or emotionally disruptive interactions [80].

5. Commemorative and educational participatory practices in social media

In addition to the various implementations of Digital Holocaust Memory considered so far, social media platforms have emerged as important contributors, as they have become crucial arenas for shaping Holocaust memory, especially as we enter the post-witness era [81]. These platforms facilitate a global dialogue about the meaning of the Holocaust in the present, allowing for a nuanced understanding of its implications [5,7]. Social media platforms serve as important "memory ecologies", enabling diverse memory practices such as posting, linking and sharing content [82]. The specific characteristics of each platform [83] influence how they are used to negotiate, commemorate and educate about the Holocaust, providing multiple avenues of engagement beyond traditional public discourse and formal education.

The potential of social media as a space for negotiating participatory practices about the Holocaust is expressed in various ways of disseminating content and engaging with online users, such as “virtual tours”, through which Holocaust organisations offer virtual visits to their exhibits and collections, allowing users to explore them remotely [84,85]; “live streams and webinars” for remote learning, allowing participants to learn from experts and interact with peers [84]; educational resources provided by Holocaust organisations, such as lesson plans, videos and materials, through their websites and social media pages [86], as well as online communities and informal resources [87]; and social media campaigns that raise awareness of the Holocaust and promote Holocaust education [84].

While fictionalised stories based on historical documents contribute to the broader Holocaust narrative [88,89], social media have also become a place where survivors and their descendants share personal stories and testimonies, providing unique insights into the Holocaust [90]. Finally, social media is where museums and archives make their collections available online, allowing users to access primary sources such as documents and photographs [[91], [92], [93]]. Grassroots initiatives have also created unofficial social media pages and groups to archive family or local memories of the Holocaust [[94], [95], [96]].

However, social media also represent an ambiguous space for Holocaust remembrance and education, as unregulated debates often lack historical accuracy, exploit history for political purposes, and have the potential to distort historical events and spread antisemitic ideas [10,12,97,98]. Paradoxically, the presence of Holocaust references on social media and the intense emotional engagement of users highlights the impact of the globalisation of Holocaust remembrance. Contrary to traditional commemorative practices, the debates and controversies surrounding the Holocaust on social media, including distortion and denial, actually amplify its significance and distinctiveness in the present, forming a "counter-public sphere" that encompasses alternative or counter-memories alongside official ones [81,99]. This dynamic can lead to forms of "agonistic memory" characterised by contestation and conflict [100,101]. However, the immediacy and interconnectedness of the Holocaust's presence on social media makes Holocaust remembrance a highly relational topic that naturally bridges past and present events [10]. As a result, the Holocaust has become more prominent and relevant in the public consciousness and, through social media, is perceived as a shared memory that connects individuals to the past and to each other.

In addition, social media platforms have also been criticised for their participatory potential and their use in promoting user agency beyond accredited cultural institutions. Two forms of agency and engagement have come under particular scrutiny: the practice of taking selfies as a form of bearing witness to Holocaust memory [102,103], and Instagram projects that aim to engage new generations through alternative accounts and perspectives, such as @ichbinsophiescholl (https://www.instagram.com/ichbinsophiescholl/) and Eva.Stories [88]. While the latter project straddles the line between trivialisation and desacralisation, it offers new ways of translating mediated Holocaust memory into social media patterns that can engage young people. Furthermore, the growing use of TikTok by museums, organisations and survivors highlights the importance of communication styles and media formats tailored to younger audiences, especially in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and related lockdowns [90].

In summary, the field of Digital Holocaust Memory highlights the significant emergence of performative practices that aim to transform individuals from passive spectators into socially and morally responsible agents [104]. These practices are central to many Digital Holocaust Memory projects, as users are encouraged to play an active role and exercise agency through actions such as liking, sharing and producing new content. Even in seemingly "static" digital environments such as social media, where users can engage in relatively simple interactions, performative behaviours can be observed. For example, images, stories and videos captured by museum visitors are often shared and approved by administrators of Holocaust museums' Facebook and Instagram pages [105].

Several dimensions that come into play in an ecologically understood learning experience are not discussed in the conceptual elaboration and brief examples provided above. As a result, the following section introduces the learning ecologies framework in relation to Digital Holocaust Memory. The learning ecologies framework encompasses a holistic approach to learning experiences, one that considers the social, cultural, technological and ecological dimensions that together form a cohesive learning environment. In other words, the framework considers the physical and virtual elements of the learning experience and how they interact. This approach is particularly relevant to digital Holocaust memory and education, which requires a multifaceted approach to understanding the complexities of the Holocaust.

6. Learning ecologies in (digital) practices of Holocaust education

We have seen that the multiple perspectives involved in teaching and learning about the Holocaust require consideration of different resources and situations, such as: educational materials (from textbooks to digital resources); the curriculum; “classroom practises, and the ways in which teachers attempt to relate to students; the relationship of history and memory; what was believed and shared across generations; and how culture and identity shape reactions to other understandings and interpretation” [106]. In light of the growing forms of Digital Holocaust Memory, it is clear that the Internet is more than just a space that allows users greater agency. It is also a complex web of multiple actors, making it necessary to consider Holocaust education and remembrance from an ecological perspective [60].

As discussed above, the transmission of collective memory involves a series of communicative and educational interventions [107]. These measures include diverse activities such as official ceremonies and political speeches [108], visits to memorial sites [109], exploration of museums and memorials [110,111], travel experiences [112], and especially engagement with educational institutions and other spaces where individuals acquire knowledge and understanding through tangible and intangible means [39,40]. In this section, we use the theoretical framework of the learning ecology perspective to explore how individuals participate in both formal and informal learning settings. In doing so, we posit that a learning ecology framework can reflect and adapt to the complexities of teaching and learning about the Holocaust.

Learning ecologies encompass the complex and interconnected systems and environments in which learning takes place. They include a variety of settings, contexts and interactions through which individuals actively engage with different subjects [27,28]. These environments can be formal, such as classrooms and educational institutions, or informal, including online communities, social networks and personal interactions [113]. While traditional pedagogical approaches associated with educational technology often focus on learning theories specific to either formal or informal learning [114], the learning ecology perspective recognises that learning is not limited to formal educational settings, but occurs through diverse interactions, experiences, and everyday life contexts [28]. Furthermore, the learning ecology approach can be applied to different learning situations, whether or not they involve the use of digital technologies. In this regard, we believe that the comprehension demands of Digital Holocaust Memory, which encompasses both digital and non-digital projects [61], can be addressed through a theoretical lens that includes any learning situation and process.

Learning ecologies are based on the idea that each individual's learning ecology is a collection of contexts, relationships and interactions that provide opportunities and resources for learning, development and achievement [27]. Learning ecologies have temporal and spatial dimensions that allow them to connect different spaces and contexts that exist simultaneously and over time throughout an individual's life course. They have two main dimensions: 1) intrinsic "learning dispositions", which consist of individuals' ideas about learning, their motivations and expectations; 2) and "learning processes", which include relationships, resources, actions and contexts [115].

While learning dispositions are linked to an individual's innate motivation to learn, the learning process is shaped by experiential factors that guide a person's learning journey throughout their lifetime [115]. Motivation, beliefs and expectations about learning play a crucial role in an individual's decision to engage in learning activities and contexts. From a learning ecology perspective [115], motivation encompasses different aspects, in particular the influence of goals and self-efficacy expectations that drive learners to engage in different types of tasks [116]. The learning ecology framework sees motivation as a personal inclination that drives individuals to seek resources and build personal and professional relationships that facilitate formal, non-formal and informal learning [117]. It can also be understood as an intrinsic motivational orientation that guides learners' engagement in their learning processes [118] and is deeply intertwined with individuals' personal narratives and social contexts [119]. On the other hand, the learning process includes the actual activities, relationships and resources with which individuals engage to learn. Together, these two dimensions create a holistic framework for learning that incorporates temporal and spatial elements to provide a comprehensive understanding of how learning takes place.

Although the framework has been approached using different methods and techniques [120], its concepts can be applied to both formal educational contexts, where ecologies are shaped primarily by institutions and teachers, and informal learning environments, where individuals and groups shape their own ecologies independently, without the guidance of a coordinator of the educational process [27]. It is common for learning in school to extend to activities outside of school or other formal organisations, and vice versa [28]. Self-initiated learning processes can indeed include a range of activities, such as using text-based sources like books and websites, exploring the Internet through blogs and social media, participating in structured learning opportunities such as courses, self-study materials and MOOCs, and cultivating knowledge-sharing relationships through mentoring, peer learning and personal contacts. On the other hand, a classroom-based learning ecology with a formal teacher-student relationship and a predetermined curriculum or syllabus may also include opportunities for autonomous and self-directed skill development supported by a rich array of resources and relationships [27]. In addition, the learning ecology lens encourages learners to see learning as a process that involves a holistic connection with other people and their environment, and empowers them to take an active role in nurturing their learning ecology.

In addition, the learning ecology perspective encourages educators and teachers to look at learning processes from a holistic point of view. It invites them to facilitate students' learning as an ecological journey that they have planned and equipped, potentially leading to new opportunities to address different contexts, relationships and interactions. Based on the recognition that learning includes "learning to learn" [121], this approach advocates the importance of personalisation, collaboration and informal learning in the future. The underlying idea emphasises the ability of the learner to become empowered and proactive in orchestrating their learning through the use of structures, processes and resources. This means that learners not only become aware of their learning process, but can also use the resources available to them to create a more dynamic and effective learning environment. As a result, learning includes engaging with peers, using technology and participating in self-directed activities to create a learning ecosystem that works for them.

As we have seen, a learning ecology encompasses a wide range of elements, including physical spaces, social interactions, cultural norms, technological tools and resources, with which individuals actively engage to participate in collective memory and cultivate historical thinking [122]. It highlights the dynamic interplay between individuals, their immediate environment, and the broader social and cultural contexts that shape and influence their learning experiences. Within different learning ecologies, individuals discover unique directions and pathways to navigate their engagement with collective memory and consequently shape their understanding, interpretation and use of historical knowledge. In addition to formal school curricula and self-initiated study, informal conversations with family, friends and peers provide valuable opportunities for individuals to exchange perspectives, share personal experiences and collaboratively construct meaning around historical events. These interactions play an important role in shaping individuals’ understanding and interpretation of collective memory, as they are influenced by different viewpoints, global and national narratives and emotional connections.

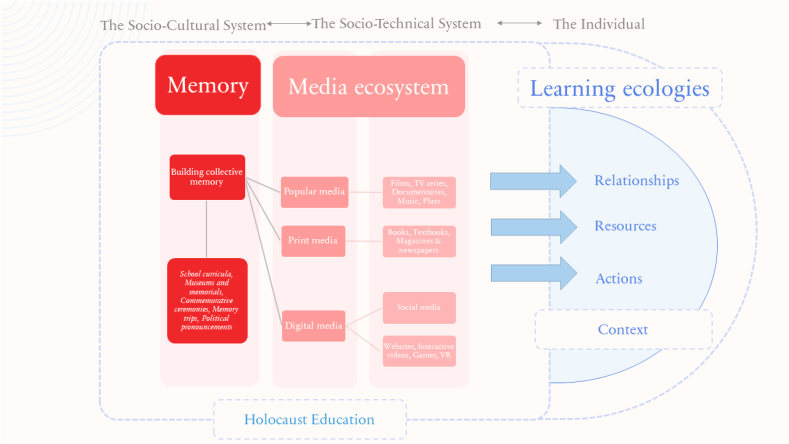

Following the explanations provided in this and previous sections, it is now possible to see how the various conceptual and thematic components are interrelated (Fig. 1). On the one hand, there is the socio-cultural context that shapes collective historical memory and the pedagogical tools developed to transmit it. In addition, the media system provides digital and non-digital tools to facilitate the transmission of memory as well as the implementation of formal and informal learning situations. Finally, there are the ways in which people develop their learning ecologies according to the two main dimensions explained above. Each of these components works together to create an environment in which memory and learning can be shared, stored and accessed. The social context provides a common language for understanding and interpreting the past, while educational devices and media systems provide the tools for passing on collective memory. Finally, learning ecologies offer directions for appropriating and transmitting collective memory today.

Fig. 1.

The relationship between collective memory, the media ecosystem and learning ecologies.

7. A case study: learning about the Holocaust informally on social media

In this section, we provide a brief overview of how the learning ecology approach was used to investigate the learning ecology of a group of adult learners who use social media platforms to acquire knowledge about the Holocaust and actively engage in remembrance practices.

In this research study [123], our primary aim was to explore the various elements that make up the learning dispositions and processes of online users. Specifically, we focused on investigating these aspects in the context of social media profiles dedicated to Holocaust remembrance. The investigation included an examination of the motivations that drive individuals to seek information on the social media pages of Holocaust memorials and museums, as well as their engagement in Holocaust-related learning experiences. We also looked at the specific activities and strategies that users used to interact with the content, including reading textual and visual information, participating in interactive discussions, exploring digital resources, and engaging in informal learning opportunities.

The decision to adopt the learning ecology approach was influenced by its unique perspective on the study of informal learning. In contrast to formal learning settings where curricula, textbooks and assessment procedures are dictated by institutions and teachers, in personal learning environments for lifelong learning [124] and social media environments [125], individuals take responsibility for shaping their own learning practices [126,127]. Despite academic research exploring the integration of social networking sites and social media platforms to enhance personal learning environments for over a decade [128], the field has yet to establish clear pedagogical theories. Indeed, there is still a prevailing tendency to rely primarily on technology acceptance models rather than pedagogical models [129]. In this light, the learning ecology approach allowed to analyse how adult learners develop their learning ecologies by using social media to learn about the Holocaust informally.

Specifically, the study investigated the interests, expectations and learning process of a group of Italian adult learners (N = 276), and an online survey tool was specifically designed to collect data on this topic. The survey aimed to gather information from online users who follow the social media profiles (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube) of four Italian Holocaust museums. In particular, we explored interests and expectations by examining the factors that influence the learning disposition dimension. At the same time, we considered the activities, resources and relationships involved in the learning process. To analyse the data and address the research questions, the researchers used a combination of descriptive and inferential statistics. This approach allowed them to summarise the characteristics of the sample group and draw conclusions from the data collected.

The results show that most respondents are female, have an average age of 50 and are highly educated. The study provides several valuable insights. First, in terms of interest and expectations, users show a strong inclination towards topics related to the intersection of transnational and national Holocaust remembrance. This suggests that they are actively seeking to understand the broader context in which Holocaust remembrance takes place and the connections between different national and international perspectives. It demonstrates a desire to engage with the complexities of collective memory and its implications across different geographical and cultural boundaries. Furthermore, users express a deep sense of civic responsibility when it comes to the legacy of the Holocaust. This indicates their recognition of the importance of remembering and honouring the victims and survivors, as well as their commitment to preventing similar atrocities in the future. Their engagement in Holocaust remembrance on social media platforms reflects a collective consciousness and commitment to promoting awareness and understanding of this historical event. In terms of the learning process, the study shows that users demonstrate proactive behaviour and a preference for individual learning. They actively seek out information, resources and opportunities for autonomous exploration. This indicates their intrinsic motivation and self-directed approach to acquiring knowledge about the Holocaust. However, the findings also suggest that peer interaction is less important to users. While they value the information and content provided by social media platforms, they may rely more on individual reflection and personal learning experiences rather than collaborative engagement with others.

Overall, these findings shed light on the specific interests, expectations and learning tendencies of users participating in Holocaust remembrance on social media. Understanding these aspects can inform the design and development of educational initiatives and resources that meet their needs and preferences, ultimately promoting a more meaningful and effective learning experience.

8. Recommendations to develop educational activities that facilitate powerful learning experiences related to Holocaust memory

The links outlined between Digital Holocaust Memory and learning ecologies can contribute to a more meaningful understanding of the Holocaust and its aftermath by providing a framework for integrating different learning perspectives and experiences. By bringing together the digital and physical components of collective memory [60], it opens up the possibility of exploring how different forms of communication, such as digital media, can be used to engage in meaningful dialogue and understanding about the difficult legacy of collective traumatic events [32]. This can also lead to a more reflective and empathetic approach to learning and understanding history [10].

We argue here that by engaging with digital technologies, users can recontextualise their understanding of the Holocaust and its place in history and learn in a more meaningful and immersive way, which can lead to a deeper understanding of the topic and its implications [42]. However, the learning ecology perspective goes a step further by suggesting specific areas for development and intervention, not to "teach" about the Holocaust, but to facilitate active and meaningful learning [27,28]. At the same time, it can provide tools to help users deal with potential challenges and disruptions that may affect their understanding and emotional engagement with such a difficult subject.

Rather than informing or designing decontextualised educational activities, educators are expected to create tools and situations that help learners to facilitate and visualise their ecological learning trajectories [130]. Regardless of whether learning ecology focuses more on formal or informal learning settings, a learning ecology trajectory about the Holocaust involves designing a comprehensive and dynamic learning experience that incorporates different elements and resources. Whether the learning experience is self-directed or guided by others, it is important to set clear learning objectives that define the specific knowledge, skills and attitudes that learners are expected to develop through the learning experience, and to identify the key concepts, historical events and issues related to the Holocaust that learners are expected to understand.

Identifying resources and materials allows to determine how they will be used to support learning. These resources may include books, documentaries, films, survivor testimonies, archival materials, digital resources, websites and educational platforms. At the same time, it is important to plan and implement a variety of learning activities that engage learners and encourage active participation, which may include individual research, group discussions, interactive presentations, (virtual) field trips and creative projects. As the focus here is on the digital component of Holocaust remembrance, it is equally important to integrate the conscious use of technology to enhance the learning experience, such as multimedia resources, online forums or discussion boards, digital archives, virtual reality experiences, social media, and educational applications or platforms that provide access to primary and secondary sources of historical content and remembrance.

At the same time, it is crucial to encourage the development of reflective and critical thinking skills. These skills enable learners to engage in a deeper level of understanding and analysis of the learning experience. When studying the Holocaust, it is essential to reflect on the historical context and significance of this tragic event, taking into account its social, political and cultural dimensions. Furthermore, as digital collective memory continues to evolve, it is necessary to critically examine the ethical implications arising from the latest advances, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning solutions. These technologies have the potential to shape the way we remember and interpret historical events, including the Holocaust. By encouraging critical thinking, learners can explore issues such as the accuracy and bias of digital representations, the role of algorithms in curating information, and the impact of technological advances on the preservation of memory.

Finally, to cultivate meaningful relationships in the context of learning, it is crucial to prioritise collaboration and dialogue between learners. By creating an environment that encourages open discussions, debates and group projects, educators can foster an atmosphere of active engagement and exchange of ideas. Facilitating discussions allows learners to share their thoughts, perspectives and insights with each other. Through respectful dialogue, they can explore different viewpoints, challenge assumptions and deepen their understanding of the Holocaust and its impact. Engaging in dialogue with peers gives learners the opportunity to learn from each other, broaden their perspectives and develop empathy by considering different interpretations and personal experiences related to the subject matter or personal background. Encouraging dialogue and collaboration also fosters a sense of community among learners. By creating a supportive learning environment where individuals feel comfortable expressing their opinions and engaging in respectful discussions, learners can develop a sense of belonging and mutual respect. This sense of community enhances the overall learning process as learners can draw on each other's knowledge and experience, creating a dynamic and enriching learning environment [96].

All these factors help learners to consider the complexity of ecological systems and the impact of their actions on the learning environment. They also enable learners to develop a better appreciation of the interconnectedness of different information systems and the links between human, natural or artificial systems [60]. This approach to education focuses on creating a learning environment that encourages learners to actively engage with their environment, collaborate with their peers and interact with the materials they are working with. In this way, learners can make connections between what they are learning and what they already know from other sources, activities and relationships, thereby creating a holistic comprehension of the subject.

In formal learning settings, it is up to educators to interpret learners’ prior knowledge and potential misconceptions [46], identify appropriate dispositions in relation to key resources (digital and non-digital) and establish meaningful relationships. This is beneficial because it allows educators to identify where students are in terms of knowledge and understanding, and then tailor their teaching to best meet their needs. In addition, by identifying appropriate resources and establishing meaningful relationships, teachers can ensure that learning is more engaging and effective [42].

Overall, when applied to teaching and learning about the Holocaust, the learning ecology approach can be effective in cultivating a complex view of the problem [10]. It should also create opportunities to critically relate past events to human puzzles in contemporary society. In this regard, the consideration of subjectivity as a starting point for the learning ecology approach should overcome the orientation of younger generations to see the Holocaust as a distant event in history with little relevance to their lives [131]. As older generations may have a more personal connection, as they may have had family members or friends who were affected by it, bridging narratives and promoting interconnections could be a valuable approach [95,132]. Consequently, educators should gain a better insight into how their students interact with the topic of the Holocaust and how they process the materials offered or available to them. Potentially, educators could seek a common sense of how these perspectives and opinions evolve over time in order to create a more effective curriculum that can help students learn and engage with the topic in a meaningful way. In addition, this will help educators to create learning environments that are conducive to critical thinking and the development of empathy, essential conditions for learning about the Holocaust [133].

9. Conclusion

Building on the conceptual components of the learning ecologies approach, this study contributes to broadening our comprehension of how digital technologies can enable new experiences of teaching and learning about the Holocaust. By applying a specific theoretical lens, it provides a methodological basis upon which pedagogical scenarios can be developed and implemented. From this perspective, the study seeks to identify the various elements of learning ecologies that need to be considered when developing Holocaust education with digital technologies, such as learners' prior knowledge and understanding, their cultural backgrounds, their motivations and attitudes, and the resources available to them. An appreciation of these elements will make it possible to create learning environments that are more responsive to learners’ needs and that can provide new experiences of educating about the Holocaust that are still relevant today.

Although not specifically designed for the field of Holocaust education, the learning ecology approach can be used to support the interweaving of formal, non-formal and informal learning settings through learners’ motivations and attitudes towards the subject, as well as their practices in terms of activities, resources and relationships. The Holocaust is not an ordinary subject and requires specific pedagogical approaches. In this sense, we believe that the learning ecology approach, which can be applied to any type of learning experience, is particularly useful for exploring the dynamics potentially implicated in Holocaust education interventions. The case study we have presented serves as a tangible illustration of how the learning ecology approach can enrich our knowledge of the complex dynamics between learners, technology, social media platforms and the vast media landscape related to the Holocaust.

However, further implications can be drawn. The use of digital technologies and social media in an ecological learning experience about the Holocaust also involves the development of digital and social media literacy skills at various levels. Digital media literacy means not only developing critical thinking skills and improving cognitive and metacognitive processes, but more importantly facilitating the co-construction of knowledge through social interaction and activity, and engaged participation in civic and public spaces [134]. It also means recognising the value of different perspectives, knowing how to use digital media responsibly and being aware of the implications and consequences of their use in an educational context. It also requires learners to be able to navigate digital media platforms, to assess the accuracy and reliability of digital content, and to be aware of ethical issues that may arise. In this sense, using media literacy skills to study the Holocaust also helps to recognise the role of media in shaping narratives around representations and stereotypes. By critically examining media related to the Holocaust [135], students gain an overview of how media can both perpetuate and challenge stereotypes [136], as well as the global power of media in shaping people's perceptions of events and people [137].

As it has been emphasised throughout this study, the Holocaust remains a sensitive and multidisciplinary issue that is highly significant today. Engaging with the Holocaust involves the task of establishing connections and relevance between this historical event and the lives of individuals in contemporary contexts [10]. Whether it serves psychological functions such as drawing analogies, satisfying the human need for connection and relationship, or constructing personal meaning, the Holocaust continues to influence modern society, giving voice to political perspectives, social identities and cultural concerns [31]. By adopting a learning ecology approach, we can place the individual at the centre of these processes, where interaction and reflection not only contribute to a deeper engagement with the Holocaust, but also help young people to make sense of their exploration and creation of new forms of citizenship in contemporary society.

In conclusion, learning ecologies represent a contemporary and dynamic approach to continuous and professional learning that harnesses the transformative power of digital media. By embracing the concept of learning ecologies, individuals and institutions can adapt to the ever-changing landscape of education and tailor learning experiences to the diverse needs and contexts of learners.

Through the lens of this study, we have also gained valuable insights into the central role of websites, memorials and other digital "places" of interaction in shaping teachers' professional learning. These digital spaces offer not only a wealth of information, but also opportunities for collaboration, reflection and engagement with diverse perspectives. As educators immerse themselves in these digital learning landscapes, they become active participants in a vast network of knowledge exchange and continuous growth.

Beyond the scope of this specific research, we recognise that media consumption for learning extends far beyond the boundaries of formal education. Learning ecologies transcend the traditional classroom setting, recognising the multifaceted nature of learning, intertwined with different facets of an individual's life and identity. Whether through exploring thought-provoking cinema, delving into enriching books, immersing themselves in the interactive world of video games [138], or navigating specialised websites, individuals construct their own unique pathways of knowledge construction.

In light of these observations, a comprehensive self-analysis or facilitated examination of one's learning ecology becomes an essential endeavour. This introspective journey enables individuals to identify their preferred ways of learning, recognise their strengths and address potential gaps. Likewise, educational institutions can use these insights to curate tailored resources, design relevant activities, and cultivate meaningful relationships that resonate with learners, thereby fostering a culture of continuous improvement and professional excellence.

Embracing learning ecologies has the potential to revolutionise the way we approach education and professional development. As we navigate the ever-expanding digital landscape, it is imperative that we harness the vast array of learning opportunities and engage in purposeful exploration. By embracing the philosophy of learning ecologies, we are paving the way for a future where education is not confined to a single space or time, but rather an enriching and lifelong journey of discovery, growth and transformation.

Statement of ethics

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animals.

[item-group:IG000062].

Author contribution statement

Stefania Manca: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Juliana Elisa Raffaghelli: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Albert Sangrà: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the first author's research project “Teaching and learning about the Holocaust with social media: A learning ecologies perspective”—Doctoral programme in “Education and ICT (e-learning)”, Universat Oberta de Catalunya, Spain.

Footnotes

https://www.claimscon.org/netherlands-study/, https://www.claimscon.org/uk-study/, https://www.claimscon.org/france-study/, https://www.claimscon.org/austria-study/, https://www.claimscon.org/study-canada/, https://www.claimscon.org/study/, https://www.claimscon.org/millennial-study/.

A number of authors have argued that the terms “Holocaust education” and “Teaching and learning about the Holocaust” encompass so many different practices and content that they cannot be considered as a single entity [39]. Although they are not meant to be synonymous, in this study we use Educating about the Holocaust, Holocaust Education, or Teaching and Learning about the Holocaust depending on the specific focus of the discourse.

A prominent pedagogical approach to teaching about the Holocaust (https://echoesandreflections.org/) emphasises sensitivity and a deep understanding of the subject. Key principles include contextualising history, humanising the Holocaust, creating a supportive learning environment and making it relevant to contemporary society. These principles aim to foster empathy, critical thinking and a comprehensive understanding of the Holocaust.

References

- 1.Pakier M., Stråth B. Berghahn; New York, NY: 2010. A European Memory? Contested Histories and Politics of Remembrance. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy D., Sznaider N. Temple University Press; Philadelphia, PA: 2006. The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sierp A. Routledge; London, UK: 2014. History, Memory, and Trans-European Identity. Unifying Divisions. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sierp A. The European union as a memory region. Contemporanea. 2020;23(1):128–132. [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Cesari C., Rigney A. De Gruyter; Berlin, München, Boston: 2014. Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fracapane K. In: As the Witnesses Fall Silent: 21st Century Holocaust Education in Curriculum, Policy and Practice. Gross Z., Stevick E.D., editors. Springer; Basel: 2015. International organisations in the globalisation of holocaust education; pp. 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assmann A. In: Memory Unbound: Tracing the Dynamics of Memory Studies. Bond L., Craps S., Vermeulen P., editors. Berghahn Books; New York and Oxford: 2017. Transnational memory and the construction of history through mass media; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walden V.G. REFRAME Books; 2022. The Memorial Museum in the Digital Age.https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/the-memorial-museum-in-the-digital-age/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niven B., Williams A. The dominance of the national: on the susceptibility of holocaust memory. Jew Hist. Stud. 2020;51(1):142–164. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novis-Deutsch N.S., Lederman S., Adams T., Kochavi A.J. The Weiss-Livnat International Center for Holocaust Research and Education; Haifa: 2023. Sites of Tension: Shifts in Holocaust Memory in Relation to Antisemitism and Political Contestation in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manca S. Digital Holocaust Memory on social media: how Italian Holocaust museums and memorials use digital ecosystems for educational and remembrance practice. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022;28(10):1152–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNESCO . UNESCO; Paris: 2022. History under Attack: Holocaust Denial and Distortion on Social Media. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein A. Reluctant Witnesses: Survivors, Their Children, and the Rise of Holocaust Consciousness. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2014. Too much memory? Holocaust fatigue in the era of the victim; pp. 166–182. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson T. Britain's promise to forget: some historiographical reflections on what Do Students Know and Understand about the Holocaust? Holocaust Studies. 2017;23(3):345–363. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pew Research Center . 2020. What Americans Know about the Holocaust.https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2020/01/22/what-americans-know-about-the-holocaust/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archives Arolsen. 2022. Gen Z and Nazi History.https://enc.arolsen-archives.org/en/study/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garde-Hansen J., Hoskins A. Reading, A., Digital memories. 2009 Save as... (London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kligler-Vilenchik N., Tsfati Y., Meyers O. Setting the collective memory agenda: examining mainstream media influence on individuals' perceptions of the past. Mem. Stud. 2014;7(4):484–499. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinhauer J. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2022. History, Disrupted: How Social Media and the World Wide Web Have Changed the Past. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus A.S., Maor R., McGregor I.M., Mills G., Schweber S., Stoddard J., Hicks D. Holocaust education in transition from live to virtual survivor testimony: pedagogical and ethical dilemmas. Holocaust Studies. 2022;28(3) 279-30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walden V.G. 2021. Playing the Holocaust.https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/digitalholocaustmemory/2020/11/24/playing-the-holocaust-part-1/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jekel T., Schötz T., Wöhs K. In: Places of Memory and Legacies – in an Age of Insecurities and Globalization. O'Reilly G., editor. Springer; Basel: 2020. Remembrance, space, education. Emancipatory and activist approaches through (Geo-)media. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manca S. Bridging cultural studies and learning science: an investigation of social media use for Holocaust memory and education in the digital age. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2021;43(3):226–253. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldman J., Musih N. In: Die Zukunft der Erinnerung: Perspektiven des Gedenkens an Nationalsozialismus und Shoah. Wiese C., Vogt S., editors. De Gruyter; Berlin: 2021. Israeli memory of the shoah in a digital age: is it still “collective”; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kansteiner W. In: The Twentieth Century in European Memory: Transcultural Mediation and Reception. Andersen T.S., Törnquist-Plewa B., editors. Brill; Leiden: 2017. Transnational Holocaust memory, digital culture and the end of reception studies; pp. 305–343. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray M. Contemporary Debates in Holocaust Education. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2014. The digital era of Holocaust education; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson N.J. In: Lifewide Learning Education and Personal Development. Jackson N.J., Cooper G.B., editors. Lifewide Education; 2013. The concept of learning ecologies. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barron B. Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: a learning ecology perspective. Hum. Dev. 2006;49:193–224. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gioia D.A., Pitre E. Multiparadigm perspectives on theory building. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990;15(4):584–602. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diner D. Restitution and memory: the holocaust in European political cultures. New Ger. Critiq. 2003;90:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neiger M., Meyers O., Ben-David A. Tweeting the Holocaust: social media discourse between reverence, exploitation, and simulacra. J. Commun. 2023;73(3):222–234. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelpšienė I., Armakauskaitė D., Denisenko V., Kirtiklis K., Laužikas R., Stonytė R., Murinienė L., Dallas C. New Media & Society; 2022. Difficult Heritage on Social Network Sites: an Integrative Review. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenhardt K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989;14(4):532–550. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilson L.L., Goldberg C.B. Editors' comment: so, what is a conceptual paper? Group Organ. Manag. 2015;40(2):127–130. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mertens D.M. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2015. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaakkola E. Designing conceptual articles: four approaches. AMS Review. 2020;10:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plessow O. In: Entangled Memories: Remembering the Holocaust in a Global Age. Henderson M., Lange J., editors. Universitätsverlag Winter; Heidelberg: 2017. Agents of transnationalization in the field of “Holocaust Education”: an introduction; pp. 315–352. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eckmann M., Stevick D., Ambrosewicz-Jacobs J. International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance; Berlin: 2017. Research in Teaching and Learning about the Holocaust: A Dialogue beyond Borders. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eckmann M., Stevick D., Ambrosewicz-Jacobs J. Metropol; Berlin: 2017. Research in Teaching and Learning about the Holocaust: Bibliographies with Abstracts in Fifteen Languages. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carrier P., Fuchs E., Messinger T. UNESCO; Paris: 2015. The International Status of Education about the Holocaust. A Global Mapping of Textbooks and Curricula. [Google Scholar]

- 42.UNESCO . UNESCO; Paris: 2014. Holocaust Education in a Global Context. [Google Scholar]

- 43.UNESCO . UNESCO; Paris: 2017. Education about the Holocaust and Preventing Genocide: A Policy Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popescu D.I., Schult T. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2015. Revisiting Holocaust Representation in the Post-witness Era. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenfeld A.H. Indiana University Press; 2013. The End of the Holocaust. Bloomington. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gray M., Foster S. What do thirteen and fourteen year olds know about the Holocaust before they study it? Int J Historical Teach, Learn Res. 2014;12(2):64–78. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kucia M. The europeanization of holocaust memory and eastern europe. East Eur. Polit. Soc. 2016;30(1):97–119. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subotić J. Cornell University Press; Ithaca and London, UK: 2019. Yellow Star, Red Star: Holocaust Remembrance after Communism. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proske M. “Why do we always have to say we're sorry?” A case study on navigating moral expectations in classroom communication on national socialism and the holocaust in Germany. Eur. Educ. 2012;44(3):39–66. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subotić J. Holocaust memory and political legitimacy in contemporary Europe. Holocaust Studies. 2022 doi: 10.1080/17504902.2022.2116539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pellegrino A., Parker J. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2022. Teaching and Learning through the Holocaust. Thinking about the Unthinkable. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salinas C. Teachers College Press; New York, NY: 2022. Teaching Difficult Histories in Difficult Times: Stories of Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goldberg T., Wagner W., Petrović N. From sensitive historical issues to history teachers' sensibility: a look across and within countries. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2019;27(1):7–38. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wrenn A., Lomas T. Music, blood and terror: making emotive and controversial history matter. Teach. Hist. 2007;127(4) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chapman A. In: Holocaust Education: Contemporary Challenges and Controversies. Foster S., Pearce A., Pettigrew A., editors. UCL Press; London, UK: 2020. Learning the lessons of the holocaust: a critical exploration; pp. 50–73. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Macgilchrist F., Christophe B. Translating globalization theories into educational research: thoughts on recent shifts in Holocaust education. Discourse: Stu CulPol Edu. 2011;32(1):145–158. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hjarvard S. In: The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects. Rössler P., editor. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2017. Mediatization; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 58.González-Aguilar J.M., Makhortykh M. Laughing to forget or to remember? Anne Frank memes and mediatization of Holocaust memory. Media Cult. Soc. 2022;44(7):1307–1329. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoskins A. Routledge; London, UK: 2018. Digital Memory Studies: Media Pasts in Transition. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walden V.G. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2021. Digital Holocaust Memory, Education and Research. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walden V.G. What is ‘virtual holocaust memory’? Mem. Stud. 2022;15(4):621–633. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neiger M., Meyers O., Zandberg E. Collective Memory in a New Media Age. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2011. On media memory. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoskins A. Memory ecologies. Mem. Stud. 2016;9(3):348–357. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walden V.G. Understanding holocaust memory and education in the digital age: before and after COVID-19. Holocaust Studies. 2022;28(3):257–278. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boswell M., Rowland A. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2023. Virtual Holocaust Memory. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Storeide A.H. In: Visitor Experience at Holocaust Memorials and Museums. Popescu D.I., editor. Routledge; London, UK: 2023. “…It No longer is the same place”. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alexiev V., Nikolova I., Hateva N. Semantic archive integration for holocaust research. The EHRI research infrastructure. Umanistica Digitale. 2019;3(4) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blanke T., Bryant M., Frankl M., Kristel C., Speck R., Vanden Daelen V., Van Horik R. The European holocaust research infrastructure portal. J Comp CulHeritage. 2017;10(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verschure P.F.M.J., Wierenga S. Future memory: a digital humanities approach for the preservation and presentation of the history of the Holocaust and Nazi crimes. Holocaust Studies. 2022;28(3):331–357. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blancas M., Wierenga S., Ribbens K., Rieffe C., Knoch H., Billib S., Verschure P. In: Digital Holocaust Memory, Education and Research. Walden V.G., editor. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2021. Active learning in digital heritage: introducing geo-localisation, VR and AR at holocaust historical sites; pp. 145–176. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marrison K. In: Digital Holocaust Memory, Education and Research. Walden V.G., editor. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2021. Virtually part of the family: the last goodbye and digital holocaust witnessing; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rothstein A.-B., Honke J., Widmann T. In: Digital Holocaust Memory, Education and Research. Walden V.G., editor. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2021. MEMOZE: memory places, memory spaces: ‘glocal’ holocaust education through an online research portal; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blanke T., Bryant M., Hedges M. Understanding memories of the Holocaust—a new approach to neural networks in the digital humanities. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. 2020;35(1):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kansteiner W. Digital doping for historians: can history, memory, and historical theory be rendered artificially intelligent? Hist. Theor. 2022;61(4):119–133. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Makhortykh M., Zucker E.M., Simon D.J., Bultmann D., Ulloa R. 2023. Shall Androids Dream of Genocides? How Generative AI Can Change the Future of Memorialization of Mass Atrocities. arXiv:2305.14358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Makhortykh M., Urman A., Ulloa R. Hey, Google, is it what the Holocaust looked like?: auditing algorithmic curation of visual historical content on Web search engines. Clin. Hemorheol. and Microcirc. 2021;26(10) [Google Scholar]

- 77.Makhortykh M. Memoriae ex machina: how algorithms make us remember and forget. Georgetown J. Int. Aff. 2021;22(2):180–185. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Presner T. In: Probing the Ethics of Holocaust Culture. Fogu C., Kansteiner W., Presner T., editors. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 2016. The ethics of the algorithm: close and distant listening to the shoah foundation visual history archive; pp. 167–202. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hazan S. Proceedings of EVA London 2023: EVA London 2023 Conference on Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. 2023. The Dance of the Doppelgängers: AI and the cultural heritage community; pp. 10–14. London, UK, July. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schultz C.K.N. Creating the ‘virtual’ witness: the limits of empathy. Mus. Manag. Curatorship. 2023;38(1):2–17. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Birkner T., Donk A. Collective memory and social media: fostering a new historical consciousness in the digital age? Mem. Stud. 2020;13(4):367–383. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hoskins A. In: Journalism and Memory. Zelizer B., Tenenboim-Weinblatt K., editors. Palgrave MacMillan; London, UK: 2014. A new memory of war; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Dijck J. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2013. The Culture of Connectivity. A Critical History of Social Media. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ebbrecht-Hartmann T. Commemorating from a distance: the digital transformation of holocaust memory in times of covid-19. Media Cult. Soc. 2021;43(6):1095–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marrison K. In: Visitor Experience at Holocaust Memorials and Museums. Popescu D.I., editor. Routledge; London, UK: 2022. Dachau from a distance: the liberation during the COVID-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Manca S. Digital memory in the post-witness era: how holocaust museums use social media as new memory ecologies. Information. 2021;12(1):31. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lazar A., Hirsch T.L. An online partner for Holocaust remembrance education: students approaching the Yahoo! Answers community. Educ. Rev. 2015;67(1):121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henig L., Ebbrecht-Hartmann T. Witnessing Eva Stories: media witnessing and self-inscription in social media memory. New Media Soc. 2022;24(1):202–226. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Popescu D.I. Eulogy of a different kind: letters to Henio and the unsettled memory of the Holocaust in contemporary Poland. Holocaust Studies. 2019;25(3):273–299. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ebbrecht-Hartmann T., Divon T. Serious TikTok: can you learn about the holocaust in 60 seconds? MediArXiv. 2022 doi: 10.33767/osf.io/nv6t2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]