Abstract

Introduction

Carbonated apatite (CO3Ap) has unique properties as an alloplastic bone substitute and has been reported the safety and efficacy for bone regeneration. However, no previous studies reported the clinical application of CO3Ap for periodontal regeneration therapy. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of periodontal regeneration with CO3Ap in treating intrabony defects, Class II and Class III furcation involvement (FI).

Methods

A single-arm and single-center prospective pilot clinical study was performed to verify the safety and efficacy of CO3Ap in patients with periodontitis. A total of four patients with seven teeth, including three deep intrabony defects, two Class II FI, and two Class III FI, were treated with CO3Ap. The clinical parameters, including probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment level (CAL), bleeding on probing (BOP), tooth mobility (Mo), Plaque index (PI), and Gingival index (GI) were evaluated at baseline, 6 months, and 9 months after the surgery. Radiographic analysis was conducted on images of dental X-ray and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) at baseline and 9 months post-surgery.

Results

The postoperative healing in all cases was uneventful, with no abnormal bleeding, pain, or swelling. The mean PPD reduction and CAL gain were 5.0 ± 1.0 mm, 4.5 ± 0.7 mm, 1.5 ± 0.7 mm, and 4.7 ± 1.2 mm, 4.5 ± 0.7 mm, 0.0 mm for intrabony defect, Class II and Class III FI, respectively. According to radiographic analysis, linear bone height in intrabony defects and vertical subclassification of FI in Class II FI were improved.

Conclusions

The clinical application of CO3Ap for the treatment of intrabony defects and Class II FI could be effective for periodontal regeneration, although its efficacy in treating Class III FI might be limited. Despite the limitations of this study, the findings in this study suggested that CO3Ap has the potential to be a promising bone graft substitute for periodontal regeneration.

Keywords: Periodontal regeneration, Carbonated apatite, Intrabony defect, Furcation involvement, Clinical study

Highlights

-

•

The present study performed the first-in-human pilot clinical trial of periodontal regenerative therapy with a single use of CO3Ap granules.

-

•

Periodontal regenerative therapy with CO3Ap granules led to clinical improvement in intrabony defects and Class II furcation involvement 9 months after the surgery.

Abbreviations

- (CO3Ap)

Carbonated apatite

- (FI)

furcation involvement

- (PPD)

probing pocket depth

- (CAL)

clinical attachment level

- (BOP)

bleeding on probing

- (Mo)

Tooth mobility

- (CBCT)

cone beam computed tomography

- (PI)

Plaque index

- (GI)

Gingival index

- (BL)

Baseline

- (CEJ)

Cementoenamel junction

- (COM)

composite outcome measure

- (DM)

Diabetes

- (MB)

mesial-buccal

- (DB)

distal-buccal

- (B)

buccal

- (M)

mesial

- (BL)

buccal-lingual

- (SPPT)

simplified papillae preservation technique

- (EPPT)

entire papillae preservation technique

- (SFA)

single flap approach

- (MPPT)

modified papillae preservation technique

1. Introduction

Periodontitis is one of the major reasons for tooth loss. Inflammation around periodontal tissue causes bone resorption and may lead to tooth loss if left untreated [1]. The bone resorption around the root can be classified by its extent and geometry. Progression of periodontitis at a different rate on neighboring tooth surfaces results in the development of intrabony defects. These defects are categorized based on the number of surrounding bone walls to one-wall, two-wall, three-wall, and circumferential defects [2]. In cases where the bone resorption reaches the entrance of the furcation in teeth with multiple roots, furcation involvement (FI) can be diagnosed. The classification of these FI is based on the extent of bone resorption, ranging from class I to class III, which signifies different levels of progression until the defect reaches through-and-through involvement [3].

Attenuating the progression of periodontal disease, non-surgical and surgical therapies have been performed. Although these techniques improve clinical parameters, the periodontal tissue lost as a result of the disease progression has remained. To overwhelm this issue, periodontal regenerative therapy has been developed in the last few decades. This concept is clinically applied to restore the lost periodontal tissue by applying biomaterials like growth factors, bone graft substitutes, membranes, and these combinations [[2], [3], [4]].

Previous systematic reviews and consensus reports indicated that periodontal regenerative therapy provided predictive clinical outcomes, particularly in the case of deep intrabony defects, and class II FI [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. Class III FI in the maxilla is less likely to achieve successful clinical outcomes due to the complexity and variety of the root anatomy. However, there are a few case reports that periodontal regenerative therapy was successful in treating a case with class III FI in the mandible [[11], [12], [13], [14]].

To maintain the space for periodontal tissue regeneration, various alloplastic bone graft substitutes have been applied to periodontal regeneration [15]. Carbonate apatite (CO3Ap) is well known as one of the components of biological bone in human beings and is to be absorbed by osteoclasts under physiological conditions [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. CO3Ap recently has been clinically implemented as the alloplastic bone graft substitute chemically manufactured [20,21]. Regarding bone regeneration, previous preclinical and clinical studies revealed that CO3Ap granules significantly enhanced bone regeneration like alveolar ridge preservation and guided bone regeneration [[22], [23], [24], [25], [26]]. However, there are limited numbers of preclinical and clinical research to evaluate the efficacy of CO3Ap granules for periodontal regeneration [[27], [28], [29]]. Surprisingly, there are no clinical studies assessing the efficacy of single use of CO3Ap granules for periodontal tissue regeneration.

Therefore, this first-in-human pilot clinical trial aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of CO3Ap granules in periodontal regeneration therapy. In order to explore the possibility of periodontal regeneration with single use of CO3Ap granules, a wide range of bone defects including intrabony defects, class II and class III FI were allocated to the present study.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient population and study design

The present study was conducted as a single-center observational prospective clinical trial (non-blinded/single-arm trial). Between January 2019 and March 2020, the patients who were undergoing periodontal therapy at the Periodontal Clinic of Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital were recruited. The subjects were recruited according to the following inclusion criteria; 1) Patients aged 20 years or older with their informed consent, 2) Patients with severe periodontitis who have alveolar bone defects with probing pocket depth (PPD) of 4 mm or greater and bone defect of 3 mm or greater on dental x-ray images in intrabony defects or Class II FI or Class III FI in the mandible, 3) Patients who accepted to receive periodontal regenerative therapy using CO3Ap granules and who agreed to use their pre- and post-treatment examination and medical records for the study. After obtaining informed consent for study participation, a preoperative examination was performed. As a preoperative examination, a medical interview, periodontal tissue examinations, dental X-ray images, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) (GALILEOS Compact, Dentsply Sirona, Baden, Switzerland), and intraoral photos were performed. The present clinical trial was conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and upon obtaining informed consent from study participation via an informed consent form. The establishment of the case registry was approved by the dental research ethics committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (D2019-046).

2.2. Clinical measurements at baseline and follow-up visits

In the present study, clinical measurements of periodontal tissue included Clinical attachment level (CAL), Probing pocket depth (PPD), Bleeding on Probing (BOP), Tooth mobility (Mo), Plaque index (PI), Gingival index (GI) were performed. The CAL and PPD were measured at the deepest sites using a periodontal probe (PCP-UNC-15, Hu-Friedy, Chicago, USA) under the 25 g force of pressure. The degree of FI was evaluated using a furcation probe (PQ2N6, Hu-Friedy, Chicago, USA). Examiners were calibrated between them to standardize their performances before the trial. Clinical measurements were performed at re-evaluation 2 months after non-surgical periodontal treatment (Baseline; BL), 24 and 36 weeks after the surgery. Fig. 1 shows an overview of the treatment and follow-up sequence of the treatment.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the treatment and follow-up sequence.

2.3. Surgical procedures

Prior to the surgery, the initial phase of periodontal treatment including oral hygiene instruction and non-surgical periodontal treatment was conducted by periodontal specialists. All periodontal regenerative treatments were performed by periodontal specialists under local anesthesia (Xylocaine; GC SHOWA-YAKUHIN CORPORATION, Tokyo, Japan). The flap was elevated according to the incision design with papillae preservation techniques by the surgeon's preference. Dental plaque, calculus, and granulation tissues were removed by ultrasonic scaler and Gracey curettes under a microscope and/or dental loupes. The morphology of intrabony defects and classification of FI were confirmed. Particulate bone substitutes consisting of CO3Ap (Cytranse Granules, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) were soaked with saline solution to enhance its handling. The bone defects were administered with bone substitutes and covered by absorbable membranes (Bio-Gide; Geistlich Pharma, Switzerland, GC membrane, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) if needed to stabilize grafted materials. When the mobility of the tooth was more than degree 2 after the flap closure, the tooth was splinted with an adjacent tooth with the temporary fixed resin cement (Superbond C&B, Clear polymer powder, Sun Medical, Shiga, Japan). At the first revaluation, the cement was removed, and checked the mobility of the tooth again. Regardless of the incision design in each case, Tension-free flap closure was secured with single interrupted sutures and/or mattress sutures (5-0 Softretch, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). A dental X-ray image was taken just after the surgery. Postsurgical care included systemic administration of antibiotics (amoxicillin 750 mg/day, 3 days), analgesics (Loxoprofen sodium 180 mg/day, 3 days), and 0.2% benzethonium chloride oral rinses (Neostelin Green 0.2% mouthwash solution, Nishika, Yamaguchi, Japan) (three times/day, 2 weeks). Sutures were removed 2 weeks post-surgery.

2.4. Radiographic analysis

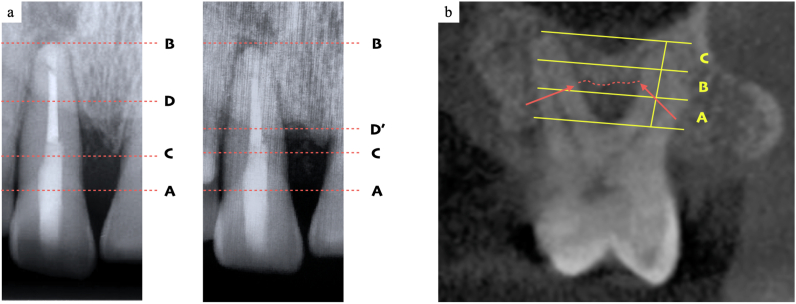

Standardized dental x-ray images using the long-cone paralleling technique were taken at BL, on the same day, 24 and 36 weeks after the operation. % bone fill of the intrabony defect was calculated according to the previous study [29] using image processing software (ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Maryland, USA). Cementoenamel junction (CEJ), apex, remaining alveolar bone crest, and bottom of the bone defect were pointed. The rate of increase in alveolar bone height was calculated as the following formula; [(A-D at BL) -(A-D’ at reevaluation)] ∗100/(C-D at BL) (Fig. 2a). Distance between CEJ and an apex of the root was used as a reference for pre- and postoperative correction.

Fig. 2.

(a). Measurement of the % bone fill using standardized dental x-ray images. Points A, B, C, D, and D′ represent the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), apex, remaining alveolar bone crest, and bottom of the bone defect at baseline and reevaluation. The rate of increase in alveolar bone height was calculated by the following formula; (A–D) - (A - D′) × 100/(C–D). The distance between CEJ and apex was used as a reference to adjust for slight errors. (b). Assessment of the vertical subclassification assessment of Furcation involvement (FI). The two-dimensional section at the tested FI was determined by dividing the two roots most close to the FI into two equal parts. In this section, the area between the apex and flute was divided into three equal parts: the coronal (subclass A), middle (subclass B), or apical (subclass C) third of the root length. The level of the worse periodontal support is classified into three subclasses.

To evaluate the new bone formation at the tested sites with intrabony defects, Linear bone height was calculated according to the previous study [30]. CBCT was captured at BL, 36 weeks after the operation. Briefly, the length between CEJ and the bottom of the intrabony defect in each two-dimensional section of the CBCT image was measured. Distance between CEJ and an apex of the root was used as a reference for pre- and postoperative correction.

The vertical subclassification of FI was diagnosed by dental CBCT images captured at BL, 36 weeks after the operation [31]. The two-dimensional section of CBCT at tested FI was determined by dividing the two roots most close to the FI into two equal parts. In this section, the area between the apex and flute was divided into three equal parts: the coronal (subclass A), middle (subclass B), or apical (subclass C) third of the root length. The level of the worse periodontal support was classified by the three subclasses (Fig. 1, Fig. 2b).

The radiographic images were analyzed using image processing software (ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Maryland, USA). All radiographic analyses were performed by the same calibrated blinded examiner who was not involved in the surgery.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The metric variables with mean and standard deviations were described (Microsoft Excel v.2011, Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

3. Results

3.1. Study population

Seven tested sites in four patients were included in the study. Four subjects (2 males and 2 females) had a mean age of 62 (35–79) years and no subjects had smoking habits or diabetes. The characteristics of each subject and test site at baseline are presented in Table .1. Regarding the type of defect morphology at the 7 test sites, 1–2 wall, 2–3 wall, Class II FI, and Class III FI were identified in 2 sites, 1 site, 2 sites, and 2 sites, respectively. The clinical and radiographic images in typical cases in each bony defect, intrabony defect, class II and III FI were shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and tested sites (n = 4 patients, 7 teeth) DM; diabetes, MB; mesial-buccal, DB; distal-buccal, B; buccal, M; mesial, BL; buccal-lingual, SPPT; simplified papillae preservation technique, EPPT; entire papillae preservation technique, SFA; single flap approach, MPPT; modified papillae preservation technique.

| Parameter | Patient |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Age/Sex | 69/Male | 35/Female | 79/Female | 65/Male | |||

| Smoking | No | No | No | No | |||

| DM | No | No | No | No | |||

| Tooth location | #11 | #16 | #24 | #16 | #36 | #46 | #47 |

| Tested site | MB | MB | DB | B | M | BL | BL |

| Defect Type | 1-2wall | 1-2wall | 2-3wall | FI Class Ⅱ | FI Class Ⅱ | FI Class Ⅲ | FI Class Ⅲ |

| Flap design | SPPT | SPPT | EPPT | SFA | MPPT | SPPT | SPPT |

| Membrane | GC membrane | Bio-Gide | – | Bio-Gide | – | Bio-Gide | Bio-Gide |

| Splinting | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Fig. 3.

Case 1; a 79-year-old female. a) Preoperative clinical view of the maxillary left first premolar; #24. b) After flap elevation with EPPT, 2–3 wall intrabony defect was observed. c) After administration of CO3Ap granules. d) 36 weeks after the surgery. e, g) Dental x-ray image and two-dimensional section of CBCT at BL. Large radiolucency was identified at the distal area of root #24. f, h) Dental x-ray image and two-dimensional section of CBCT at 36 weeks post-surgery. Bone fill of the distal region was observed.

Fig. 4.

Case 2; a 65-year-old male. a) Preoperative clinical view of the mandibular left first molar; #36. b) After flap elevation with SFA, Class II FI was observed. c) After administration of CO3Ap granules. d) 36 weeks after the surgery. e, g) Dental x-ray image and two-dimensional section of CBCT at BL. Large radiolucency was identified at the buccal area of the FI. f, h) Dental x-ray image and two-dimensional section of CBCT at 36 weeks post-surgery. FI at the buccal area was closed.

Fig. 5.

Case 3; a 65-year-old male. a) Preoperative clinical view of the mandibular right first molar; #46. b) After flap elevation with SPPT, Class III FI was observed. c) After administration of CO3Ap granules. d) 36 weeks after the surgery. e, g) Dental x-ray image and two-dimensional section of CBCT at BL. Large radiolucency was identified and connected through and through at the FI. f, h) Dental x-ray image and two-dimensional section of CBCT at 36 weeks post-surgery. Bone defect at FI has remained.

3.2. Clinical outcomes

Postoperative healings in all tested sites were uneventful, without abnormal bleeding, pain, redness, or swelling. Primary healing and no exposure of grafted materials and membranes were achieved in all sites. The clinical outcomes at each time point of BL, 24 and 36 weeks after the surgery were shown in Table .2. The mean CAL gain at 36 weeks after the surgery were 4.7 ± 1.2 mm, 4.5 ± 0.7 mm, 0.0 mm for intrabony defect, Class II FI and Class III FI, respectively. The mean PPD reduction at 36 weeks after the surgery was 5.0 ± 1.0 mm, 4.5 ± 0.7 mm, and 1.5 ± 0.7 mm for intrabony defect, Class II FI, and Class III FI, respectively. Bleeding on probing (BOP) of all the test sites was negative at 24 and 36 weeks after the surgery except one site which revealed Class III FI before the surgery. The mobility of the tested teeth did not change during the observational period. One of the Class II FI sites improved to Class 1, the other site succeeded to close the FI.

Table 2.

Results of clinical and radiographic evaluation. CAL; clinical attachment level, PPD; probing pocket depth, Mo; teeth mobility, PI; plaque index, GI; gingival index, FI; furcation involvement, BL, baseline. A; subclass A, B; subclass B.

| Parameter | Patient |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Tooth location | #11 | #16 | #24 | #16 | #36 | #46 | #47 |

| Defect Type | 1-2wall | 1-2wall | 2-3wall | FI ClassⅡ | FI ClassⅡ | FI ClassⅢ | FI ClassⅢ |

| CAL BL (mm) | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| CAL 24w (mm) | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| CAL 36w (mm) | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 9 |

| PPD BL (mm) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| PPD 24w (mm) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| PPD 36w (mm) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| BOP BL | – | – | + | + | + | – | + |

| BOP 24w | – | – | – | – | – | – | + |

| BOP 36w | – | – | – | – | – | – | + |

| Mo BL | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mo 24w | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mo 36w | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| PI BL | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PI 24w | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PI 36w | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| GI BL | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| GI 24w | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| GI 36w | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| % bone fill 24w (%) | 33.51 | 28.14 | 52.75 | ||||

| % bone fill 36w (%) | 48.36 | 28.98 | 44.62 | ||||

| Linear bone height (mm) | 2.41 | 1.92 | 2.94 | ||||

| Subclassification of FI 36w | B→A | B→A | B→B | B→B | |||

3.3. Radiographic analysis

The radiographic analysis in each patient was shown in Table .2. The mean % bone fill at tested sites with intrabony defects amounted to 38.13 ± 12.94% at 24 weeks, and 40.65 ± 10.28% at 36 weeks, respectively. The vertical subclassification of FI at the sites with Class II FI was altered from Class B to Class A. The sites with Class III FI were not altered. The mean gain of Liner bone height at tested sites with intrabony defects between the BL and 36 weeks after the surgery amounted to 2.42 ± 0.51 mm.

4. Discussion

The present first-in-human pilot clinical trial demonstrated that periodontal regenerative therapy with CO3Ap granules improved periodontal tissue, especially in intrabony defect and class II FI. Severe adverse events were not observed thorough out the study except slight postoperative pain, rednee, and swelling at the test sites. Our findings matched the previous preclinical and clinical studies assessing the safety of CO3Ap granules in periodontal regenerative therapy [[27], [28], [29]].

Single-use of CO3Ap granules for the deep intrabony defect could be effective. Regarding intrabony defects, 4.7 ± 1.2 mm in the mean CAL gain, and 5.0 ± 1.0 mm in the mean PPD reduction were achieved at 36 weeks after the surgery. The mean % bone fill and the mean gain of Liner bone height between BL and 36 weeks after the surgery amounted to 40.65 ± 10.28%, and 2.42 ± 0.51 mm, respectively. The homogenous results were reported by the previous preclinical studies [27] and also clinical studies assessing the single use of other bone graft materials in periodontal regenerative therapy [32].

According to the criteria of successful periodontal regenerative therapy described by the previous study [33], every tested site fulfilled this composite outcome measure (COM). These outcomes in the present study are partially explained by the degree of the initial CAL in each patient with intrabony defects. The previous studies indicated that sites with an initial deep intrabony defect before the periodontal regenerative therapy tended to reveal a great amount of CAL gain [34]. Initial CAL measured in three sites with intrabony defects amounted to 10 mm, 8 mm, and 9 mm, respectively.

The clinical outcomes between Class II and Class III FI resulted in contrast in this study. In sites with Class II FI, 4.5 ± 0.7 mm in the mean CAL gain, and 4.5 ± 0.7 mm in the mean PPD reduction were achieved at 36 weeks after the surgery. Additionally, one site improved to Class 1 FI, and the other site succeeds to be closed FI. Both sites were diagnosed as Class A in terms of the vertical subclassification of FI at 36 weeks after the surgery. According to the previous study, improvement in the vertical subclassification of FI corresponds to an improvement in the prognosis for teeth [31].

On the other hand, improvement of CAL and PPD was not observed in the sites with Class III FI. No tested sites fulfilled the COM which resulted in a treatment failure. A few clinical studies reported the successful outcome of periodontal regenerative therapy for Class III FI [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. However, these discrepancies between the present and the previous studies might be ascribed to the variety of anatomy and tooth morphology of Class III FI. The previous statements of the world workshop that periodontal regenerative therapy for Class III FI was less predictive supported the clinical outcomes of Class III FI in this study [[8], [9], [10]].

CO3Ap granules could be promising bone graft materials for periodontal regenerative therapy. One of the characteristics of CO3Ap is its resorption rate. Under physiological conditions, CO3Ap is not hydrolyzed and is absorbed by osteoclasts [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. This feature achieves to maintain the space for tissue regeneration over healing periods and finally replaces the biological tissue through remodeling. The other alloplastic bone graft substitutes like beta-tricalcium phosphate are hydrolyzed quickly and under physiological conditions and are unreliable to maintain the environment for tissue regeneration in sufficient periods [35]. In contrast, the resorption rate of xenogenic bone substitutes like deproteinized bovine bone materials is remarkably slow [[36], [37], [38]]. Remaining bone graft substitutes in the regenerated tissue could be theoretically revealed a smaller number of blood vessels and debilitation of immune cell migrations. These circumstances may attenuate the resistance of the regenerated tissue from re-infection [39].

The present study was conducted as an explorative observational prospective clinical trial with a small number of subjects. Further studies with larger sample size and longer follow-up periods with study design as randomized clinical trials are warranted to confirm the efficacy of the periodontal regeneration with single-use of CO3Ap granules.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of the study, periodontal regenerative therapy with CO3Ap granules for intrabony defects and Class II FI appeared to be clinically safe and effective.

Author contribution

S.F., T.I. conceived the study design. S.F., M.O. did the surgical therapies. S.F. performed data acquisition and analysis. S.F. drafted the manuscript. S.F., M.O., and T.I. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Takanori Iwata reports a relationship with GC Corporation that includes: funding grants.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the staff of the Department of Periodontology of TMDU, especially Yuichi Ikeda, DDS, PhD, for their assistance with data collection. This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Grant number 20K18571, 23K15993 for S.F.).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

References

- 1.Papapanou P.N., Wennström J.L., Gröndahl K. A 10-year retrospective study of periodontal disease progression. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16(7):403–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynolds M.A., Kao R.T., Nares S., et al. Periodontal regeneration – intrabony defects: practical applications from the AAP regeneration workshop. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2015;5:21–29. doi: 10.1902/cap.2015.140062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aichelmann-Reidy M.E., Avila-Ortiz G., Klokkevold P.R., et al. Periodontal regeneration - furcation defects: practical applications from the AAP regeneration workshop. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2015;5(1):30–39. doi: 10.1902/cap.2015.140068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sculean A., Nikolidakis D., Nikou G., Ivanovic A., Chapple I.L., Stavropoulos A. Biomaterials for promoting periodontal regeneration in human intrabony defects: a systematic review. Periodontol 2000. 2015;68(1):182–216. doi: 10.1111/prd.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kao R.T., Nares S., Reynolds M.A. Periodontal regeneration - intrabony defects: a systematic review from the AAP Regeneration Workshop. J Periodontol. 2015;86(2 Suppl):S77–S104. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.130685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds M.A., Kao R.T., Camargo P.M., et al. Periodontal regeneration - intrabony defects: a consensus report from the AAP Regeneration Workshop. J Periodontol. 2015;86(2 Suppl):S105–S107. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nibali L., Koidou V.P., Nieri M., Barbato L., Pagliaro U., Cairo F. Regenerative surgery versus access flap for the treatment of intra-bony periodontal defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(Suppl 22):320–351. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy M.S., Aichelmann-Reidy M.E., Avila-Ortiz G., et al. Periodontal regeneration - furcation defects: a consensus report from the AAP Regeneration Workshop. J Periodontol. 2015;86(2 Suppl):S131–S133. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jepsen S., Gennai S., Hirschfeld J., Kalemaj Z., Buti J., Graziani F. Regenerative surgical treatment of furcation defects: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(Suppl 22):352–374. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanz M., Herrera D., Kebschull M., et al. Treatment of stage I-III periodontitis-The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(Suppl 22):4–60. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gantes B.G., Synowski B.N., Garrett S., Egelberg J.H. Treatment of periodontal furcation defects. Mandibular class III defects. J Periodontol. 1991;62:361–365. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.6.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Setya A.B., Bissada N.F. Clinical evaluation of the use of calcium sulfate in regenerative periodontal surgery for the treatment of Class III furcation involvement. Periodontal Clin Invest. 1999;21(2):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komiya-Ito A., Tomita S., Kinumatsu T., Fujimoto Y., Tsunoda M., Saito A. Longitudinal supportive periodontal therapy for severe chronic periodontitis with furcation involvement: a 12-year follow-up report. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2013;54(4):243–250. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.54.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemoto Y., Kubota T., Nohno K., Nezu A., Morozumi T., Yoshie H. Clinical and CBCT evaluation of combined periodontal regenerative therapies using enamel matrix derivative and deproteinized bovine bone mineral with or without collagen membrane. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2018;38(3):373–381. doi: 10.11607/prd.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuba S., Okada M., Nohara K., Iwata T. Alloplastic bone substitutes for periodontal and bone regeneration in dentistry: current status and prospects. Materials. 2021;14(5):1096. doi: 10.3390/ma14051096. 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa K. Bone substitute fabrication based on dissolution-precipitation reactions. Materials. 2010;3(2):1138–1155. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa Kunio, Hayashi Koichiro. Carbonate apatite artificial bone. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2021;22(1):683–694. doi: 10.1080/14686996.2021.1947120. 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa Kunio, Miyamoto Youji, Tsuchiya Akira, Hayashi Koichiro, Tsuru Kanji, Go Ohe. Physical and histological comparison of hydroxyapatite, carbonate apatite, and β-tricalcium phosphate bone substitutes. Materials. 1993;11(10) doi: 10.3390/ma11101993. 2018;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muguruza L.B., Mäkelä K., Yrjälä T., Jukka Salonen J., Yamashita K., Nakamura M. Surface electric fields increase human osteoclast resorption through improved wettability on carbonate-incorporated apatite. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(49):58270–58278. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c14358. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagai H., Kobayashi-Fujioka M., Fujisawa K., et al. Effects of low crystalline carbonate apatite on proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation of human bone marrow cells. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2015;26(2):99. doi: 10.1007/s10856-015-5431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi M., Tsuru K., Nagai H., et al. Fabrication and evaluation of carbonate apatite-coated calcium carbonate bone substitutes for bone tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12(10):2077–2087. doi: 10.1002/term.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suehiro F., Komabashiri N., Masuzaki T., Ishii M., Yanagisawa T., Nishimura M. Efficacy of bone grafting materials in preserving the alveolar ridge in a canine model. Dent Mater J. 2022;41(2):302–308. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2021-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mano T., Akita K., Fukuda N., et al. Histological comparison of three apatitic bone substitutes with different carbonate contents in alveolar bone defects in a beagle mandible with simultaneous implant installation. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2020;108(4):1450–1459. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.34492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato N., Handa K., Venkataiah V.S., et al. Comparison of the vertical bone defect healing abilities of carbonate apatite, β-tricalcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite, and bovine-derived heterogeneous bone. Dent Mater J. 2020;39(2):309–318. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2019-084. 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kudoh K., Fukuda N., Kasugai S., et al. Maxillary sinus floor augmentation using low-crystalline carbonate apatite granules with simultaneous implant installation: first-in-human clinical trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77(5):985.e1–985.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2018.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa T., Kudoh K., Fukuda N., et al. Application of low-crystalline carbonate apatite granules in 2-stage sinus floor augmentation: a prospective clinical trial and histomorphometric evaluation. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2019;49(6):382–396. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2019.49.6.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeuchi S., Fukuba S., Okada M., et al. Preclinical evaluation of the effect of periodontal regeneration by carbonate apatite in a canine one-wall intrabony defect model. Regen Ther. 2023;24(22):128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2023.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shirakata Y., Setoguchi F., Sena K., et al. Comparison of periodontal wound healing/regeneration by recombinant human fibroblast growth factor-2 combined with β-tricalcium phosphate, carbonate apatite, or deproteinized bovine bone mineral in a canine one-wall intra-bony defect model. J Clin Periodontol. 2022;49(6):599–608. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitamura M., Yamashita M., Miki K., et al. An exploratory clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combination therapy of REGROTH® and Cytrans® granules for severe periodontitis with intrabony defects. Regen Ther. 2022;21:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2022.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwata T., Yamato M., Washio K., et al. Periodontal regeneration with autologous periodontal ligament-derived cell sheets - a safety and efficacy study in ten patients. Regen Ther. 2018;24(9):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tonetti M.S., Christiansen A.L., Cortellini P. Vertical subclassification predicts survival of molars with class II furcation involvement during supportive periodontal care. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(11):1140–1144. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camelo M., Nevins M.L., Schenk R.K., et al. Clinical, radiographic, and histologic evaluation of human periodontal defects treated with Bio-Oss and Bio-Gide. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 1998;18(4):321–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trombelli L., Farina R., Vecchiatini R., Maietti E., Simonelli A. A simplified composite outcome measure to assess the effect of periodontal regenerative treatment in intraosseous defects. J Periodontol. 2020;91(6):723–731. doi: 10.1002/JPER.19-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mikami R., Mizutani K., Shioyama H., et al. Influence of aging on periodontal regenerative therapy using enamel matrix derivative: a 3-year prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2022;49(2):123–133. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwon S.H., Jun Y.K., Hong S.H., Lee I.S., Kim H.E., Won Y.Y. Calcium phosphate bioceramics with various porosities and dissolution rates. J Am Ceram Soc. 2002;85:3129e31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujisawa K., Akita K., Fukuda N., et al. Compositional and histological comparison of carbonate apatite fabricated by dissolution–precipitation reaction and Bio-Oss®. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2018;29(8):21. doi: 10.1007/s10856-018-6129-2. 121. 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Handschel J., Simonowska M., Naujoks C., et al. A histomorphometric meta-analysis of sinus elevation with various grafting materials. Head Face Med. 2009;11(5):12. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orsini G., Traini T., Scarano A., et al. Maxillary sinus augmentation with Bio-Oss particles: a light, scanning, and transmission electron microscopy study in man. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;74(1):448–457. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato R., Matsuura T., Akizuki T., et al. Influence of the bone graft materials used for guided bone regeneration on subsequent peri-implant inflammation: an experimental ligature-induced peri-implantitis model in Beagle dogs. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2022;8(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s40729-022-00403-9. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]