Abstract

Online programs that reduce relationship distress fill a critical need; however, their scalability is limited by their reliance on coach calls. To determine the effectiveness of the online OurRelationship program with varying levels of coach support, we conducted a comparative effectiveness trial with 740 low-income couples in the United States. Couples were randomly assigned to full-coach (ncouples = 226; program as originally designed), automated-coach (ncouples = 145; as a stand-alone program with tailored automated emails only), contingent-coach (ncouples = 145; as an adaptive program where tailored automated emails are followed by more coaching if couples did not meet progress milestones), or a waitlist control condition (ncouples = 224). All analyses were conducted within a Bayesian framework. Completion rates were comparable across conditions (full-coach: 65 %, automated-coach: 59 %, contingent-coach: 54 %). All intervention couples reported reliable pre-post gains in relationship satisfaction compared to waitlist control couples (dfull = 0.46, dcontingent = 0.47, and dautomated = 0.40) with no reliable differences across intervention conditions. Over four-month follow-up, couples in full- and contingent-coach conditions maintained gains in relationship satisfaction and couples in the automated-coach condition continued to improve. Given the comparable completion rates and minimal differences in effect sizes across intervention conditions, all three coaching models appear viable; therefore, the choice of model can vary depending on available resources as well as couple or stakeholder preferences. This study was preregistered (ClinicalTrials.govNCT03568565).

Keywords: Digital health, Couple therapy, Automated coach support, Treatment effectiveness evaluation, Relationship satisfaction

Highlights

-

•

Comparable completion rates across all coaching conditions.

-

•

All coach conditions improved relationship satisfaction relative to the waitlist.

-

•

No differences in relationship satisfaction gains between coaching levels.

-

•

The OurRelationship program can be effective with automated coach support.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of relationship distress in the United States is troubling. Approximately one-third of marriage are unhappy (Lavner and Bradbury, 2010; Whisman et al., 2008) and 40 %–50 % of first marriages end in divorce (Smock and Schwartz, 2020). Furthermore, relationship difficulties disproportionately impact lower-income couples (Bramlett and Mosher, 2002; Trail and Karney, 2012). Relationship distress has substantial negative impacts on individual mental and physical health (Slatcher and Selcuk, 2017; Robles et al., 2014). Fortunately, couple therapy (Roddy et al., 2020b) improves relationship satisfaction (Cohen's d = 0.91) alongside communication (d = 0.76) and emotional intimacy (d = 0.39) compared to control. Likewise, relationship education (Hawkins et al., 2008) ameliorates relationship distress (ds = 0.30 to 0.36) and communication difficulties (ds = 0.43 to 0.45). Given the inherent limitations in the reach of in-person relationship interventions, technology-delivered interventions that have the capacity to reach many couples are needed (Doss et al., 2017).

The RE-AIM Framework defines five areas to evaluate health promotion interventions to ensure external validity and improve adoption and implementation (Glasgow et al., 1999): reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance. OurRelationship, an online adaptation of Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (Doss et al., 2013), is able to reach significantly more couples than traditional couple therapy (Georgia Salivar et al., 2020) with substantial effectiveness. OurRelationship consists of online e-learning modules and brief calls with a paraprofessional coach and is the most well-researched online program for distressed relationships with five randomized trials to date demonstrating its effectiveness (Doss et al., 2016; Roddy et al., 2018; Rothman et al., 2019; Doss et al., 2020; Hatch et al., 2022). In randomized controlled trials with a nationally representative sample (Doss et al., 2016) and two independent low-income samples (Doss et al., 2020, Hatch et al., 2022) in the United States, OurRelationship improved multiple domains of relationship functioning (Cohen's ds = 0.46–0.69) as well as individual mental and physical health (ds = 0.13–0.50) (Doss et al., 2016; Roddy et al., 2020a) with effect sizes similar to more intensive, in person interventions. Further, these effects are maintained for at least 12 months (Doss et al., 2019; Roddy et al., 2021).

While technology-delivered programs such as OurRelationship help address concerns of reach and effectiveness (Georgia Salivar et al., 2020), coaching is the primary rate-limiting factor for its adoption and implementation. Coaches – paraprofessionals with mental health experience and training – require initial training and ongoing clinical supervision. Moreover, the cost of training, salaries, and supervision do not decrease at the same rate as the digital program itself when increasing scale. While an ideal program would have both high completion and high effectiveness, moderate completion and moderate effectiveness would still have a substantial impact on the population if barriers to adoption and implementation were decreased. A greater understanding of how coaching impacts both completion and effectiveness of the program – as well as if more sophisticated automation can alter the need for coaching – can inform potential adaptations to be made during delivery to reduce implementation barriers.

In the individual intervention literature, evidence suggests that any additional form of support, be it automated emails or coach phone calls, can substantially increase program adherence and treatment gains and are key to the success of web-based interventions (Oromendia et al., 2016; Kleiboer et al., 2015; Levin et al., 2021; Berger et al., 2011). However, questions remain regarding how adherence and treatment gains in online couple-based relationship interventions vary depending on the types and levels of coaching. Previous research on OurRelationship investigated the amount of coaching needed for program completion and effects on relationship satisfaction, an omnibus measure of relationship functioning. Couples completing a brief version of OurRelationship following a 6-week waitlist were randomized to do the program with or without a coach. Couples with a coach experienced improvements in relationship satisfaction (within-group d = 0.40) and 71 % completed the program (Roddy et al., 2017). In contrast, couples not assigned a coach did not experience significant improvements in relationship satisfaction and only 42 % completed the program (Roddy et al., 2017). An open trial of OurRelationship comparing couples who received four coach calls (“high” support) to a single coach call (“low” support) found similar effects on relationship satisfaction (within-group ds = 0.61 and 0.52 for high and low support, respectively) but higher program completion in the high (66 %) than low support (36 %) group (Roddy et al., 2018). Finally, a second open trial of OurRelationship without any eligibility or enrollment requirements and without any coach support saw only 6 % of couples completing the program (Rothman et al., 2019). While these studies suggest that a coach may play a potentially important role in ensuring substantial effects and completion, the absence of a control group makes it unclear what the intervention effects are with reduced coaching. Moreover, it remains unclear what the optimal role of a coach is and how technological advances, such as automated reminders, might shift that balance. To help answer this question, OurRelationship was updated to include extensive automated reminders based on progress through the program and responses to key programmatic questions. These technological advances may replace some of the accountability typically provided by coaches (Mohr et al., 2011), and in turn increase program adherence and treatment gains for couples receiving low or automated coach support.

Furthermore, it is possible that couples may vary in their need for support to complete the program. In the individual literature, one meta-analysis of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression found coaching provided substantial benefit only to individuals with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms (Karyotaki et al., 2021). Adaptive interventions mirror clinical work by adjusting the dose or intensity of an intervention based on client characteristics (Collins et al., 2004). For OurRelationship, adding a coach when a couple is experiencing difficulty completing the program in a timely manner – rather than assigning everyone the same dose of coaching at the start of the program – could be an effective middle ground. Examining the effectiveness of OurRelationship with reduced coach support and comparing the relative effectiveness with varying levels of coaching has important implications for adapting and implementing OurRelationship on a large scale.

The current study seeks to contribute to the existing knowledge of OurRelationship and online couple-based relationship intervention more generally by testing and comparing OurRelationship delivered with three levels of coaching: (1) full coach (i.e., as originally designed where couples receive one introductory coach call followed by three coach calls), (2) automated coach (i.e., as a stand-alone program where couples receive one introductory coach call followed by tailored automated emails), and (3) contingent coach (i.e., as an adaptive program where couples receive one introductory coach call followed by either tailored automated emails or additional coach calls depending on participant engagement). Specifically, we examined (1) differences in completion rates across intervention conditions, (2) effects on relationship satisfaction (as an omnibus measure of relationship functioning) for OurRelationship delivered with reduced coaching relative to a waitlist control (effects of full coach relative to a waitlist group was reported in Hatch et al., 2022), and (3) differences in intervention effects on relationship satisfaction across intervention conditions.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Data from a larger partial/limited sequential multiple assignment randomized trial design (Lei et al., 2012) involving 1246 couples (N = 2494 individuals; see Fig. 1 for the consort diagram) was used. As documented in the study registration (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03568565), participants were first randomized to one of five groups – a waitlist control, OurRelationship (with and without additional coaching), and ePREP (with and without additional coaching); those initially assigned to either program without additional coach support and who were not completing activities in a timely manner were then re-randomized to either continue with or without additional coach support. A waitlist control group was selected for two reasons: (1) this is what has been done in previous studies of OurRelationship, making comparisons of between-group effect sizes across trials possible, and (2) a waitlist control group likely reduces the chances that couples would seek other interventions to improve their relationship during the study; thus, it may yield a more accurate estimate of the effect of the program versus no intervention. The current sample is comprised of 740 couples (n = 1480 individuals) who were in the waitlist control group (ncouples = 224) or one of the three coaching conditions of OurRelationship: full-coach (ncouples = 226), contingent-coach (ncouples = 145; initially not assigned to receive additional coaching but re-randomized to receive coaching if non-responsive) and automated-coach (ncouples = 145; initially not assigned to receive additional coaching and re-randomized to continue without coaching if non-responsive). Data from the waitlist control group and the OurRelationship full-coach condition used in the current study has been reported in Hatch et al. (2022). Unequal group size is due to planned unbalanced randomization (see supplement). Eight individuals withdrew consent, resulting in a final analytic sample size of 740 couples (n = 1472 individuals). Couples (ncouples = 506) randomized to the other intervention program, ePREP, were not included because of differences in definitions of program completion and “non-responsive” (triggering additional coaching).

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram.

Note. 1Four individuals withdrew consent, 2two individuals withdrew consent, 3two individuals withdrew consent, 4not included in these analyses.

Participants were on average 33.25 years old (SD = 7.92) and racially identified as White (68.8 %), Black (18.4 %), multiracial (5.0 %), Asian (0.8 %), American Indian or Alaskan Native (1.7 %), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders (0.2 %), or Other (5.0 %). Ethnically, 13.3 % identified as Hispanic or Latino. Participants were predominantly in mixed-gender relationships (92.3 %), with 7.7 % in same-gender relationships; 47 % identified as male, with 53 % identified as female. Couples identified their current marital status as married (45.2 %), engaged (28.7 %), and cohabiting (26.1 %) and reported being in a committed relationship with their current partner for an average of 5.76 years (SD = 5.27). Educational achievement ranged from having no degree (7.7 %), to having a GED or equivalent (14.8 %), high school diploma (16.6 %), vocational degree (9.4 %), college experience that did not culminate in a degree (25.4 %), Associate's degree (10.7 %), Bachelor's degree (12.6 %), or advanced degree (Master's or Doctoral level; 2.8 %). Less than half of the sample were employed full-time (41.2 %), with the remainder of participants employed part time (13.0 %), temporarily or seasonally (9.2 %), or employed with variable hours (6.6 %). Thirty percent of participants were not currently employed. Most participants reported an average individual annual income of under $25,000 (71.0 %), with the remainder reporting between $25,000—$50,000 (24.9 %), $50,000—$75,000 (3.6 %), between 75,000–100,000 (0.4 %), and over $100,000 (0.1 %).

2.2. Procedure

Permission was granted from the Institutional Review Board at University of Miami prior to participant recruitment. This study was preregistered (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03568565), and all data and R scripts are made available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/yk63v/?view_only=62db2da4b4ca40b39a0928acc38d9005). Recruitment was conducted using paid advertising on Google and social media. Couples were eligible if they were married, engaged, or cohabiting with their partner for at least six months; had a household income <200 % of the federal poverty line; lived in the United States; were between the ages of 18–64; could read and write in English fluently; had high speed or 3G internet access; agreed to forego couples treatment for 6 months; had not previously participated in OurRelationship or PREP programs; and did not endorse fear of (i.e., quite, very, or extremely afraid) or severe (e.g., forced sex, choking, threated with a gun or knife) intimate partner violence.

2.2.1. Intervention

OurRelationship is an online adaptation of Integrative Behavioral Couples Therapy (Christensen et al., 2004) designed to improve relationship satisfaction for distressed couples. The program consists of three phases of online activities that take 6–8 h to complete in total. The first phase, Observe, is devoted to helping couples identify and define a relationship problem (known as the core issue) that they feel is at the center of their relationship difficulties. In the next phase, Understand, couples learn to develop a deeper understanding of what causes, maintains, and exacerbates the core issue. In the final phase, Respond, couples are taught skills to problem-solve the core issue (Doss et al., 2013).

2.2.2. Coaching

During enrollment, all couples completed a fifteen-minute introductory videoconference call with a coach to outline procedures, inform couples about what they could expect from the program, and obtain verbal consent; only after this call were couples granted access to the online materials. Couples assigned to the full-coach condition had the opportunity to schedule three additional fifteen-minute videoconference calls with the coach, as originally designed, after completing Observe, Understand, and Respond, respectively. On these calls, the coach discussed program content, practiced skills learned from the program activities, and addressed any technical problems or barriers to activity completion. To ensure reliability and quality control, coaches followed a structured, semi-scripted manual for each call.

Couples assigned to the automated-coach condition completed online materials without additional coach calls following each phase, allowing them to progress through the materials entirely on their own timeline. They also received automated emails from their coach regarding their progress and reminding them to complete their materials.

Couples assigned to the contingent-coach condition received automated emails from their coach (similar to the automated-coach condition). However, if they were deemed “non-responsive” – defined as taking >14 days to reach a particular milestone in the online activities since completing the most recent activity – they would be offered the opportunity to schedule coach calls for the remainder of the program. For example, if couples were in the Observe phase when deemed “non-responsive”, they would have the opportunity to complete the remaining three coaching calls—parallel to the full coach condition; if couples were in the Respond phase, they would only have one additional coach call.

2.3. Outcome measures

Program completion by each phase and the entire program were coded at the couple level (complete = 1, incomplete = 0). Couples were considered to have completed a certain phase if both partners finished all the online activities required before and in the corresponding phase.

Relationship satisfaction was measured using the abbreviated, four-item version of the Couples Satisfaction Index (Funk and Rogge, 2007). Participants rated how much they agreed with questions such as: “I have a warm and comfortable relationship with my partner.” Scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more satisfaction ( = 0.92). Satisfaction was assessed five times: baseline, mid-assessment (roughly 1 month from baseline), post-assessment (roughly 2 months from baseline), and 2- and 4-month follow-ups, which were roughly 4 and 6 months from baseline, respectively.

2.4. Data analysis

Analyses were conducted within a Bayesian framework using the brms package in R (v2.19.0; (Bürkner, 2017)). Bayesian approach has several advantages over frequentist approach including a de-emphasis on p-values, the ease of interpretation, and the ability to integrate prior information. Instead of 95 % confidence intervals, 95 % Bayesian credible intervals were reported, which indicate that there is a 95 % probability that the true estimate would lie within the interval based on the data and prior knowledge. When the 95 % Bayesian credible interval does not include 0, we conclude that the parameter is reliably different from 0, indicating that there is an effect. Model convergence was evaluated based on statistics and visual inspection of whether the trace plots depicting the sample chains showed a converging pattern. s exceeding 1.05 would be indicative of possible non-convergence (Vehtari et al., 2021).

To examine differential completion rates, three two-level logistic regression models were run (i.e., couples nested within coaches) – one for each phase. Each were fitted with 2 parallel chains, default priors, 1000 warm-up iterations and a total of 2000 iterations. The automated-coach condition was treated as the reference group. Two binary variables were used to represent assignment to the full-coach or the contingent-coach condition.

To capture differential relationship satisfaction changes, a piecewise three-level multilevel model was utilized. Multilevel models account for dependencies in the data (i.e., repeated measures nested within couples nested within coaches). Slopes modelling the effect of time during and following the program, respectively, were centered at the post assessment and allowed to vary across couples and coaches. The waitlist control was treated as the reference group. Differential changes in each of the three intervention conditions relative to the waitlist control were modeled by including the main effects of group assignments and their two-way interactions with effects of time during and following the program, respectively. There were 9.6 %, 14.4 %, 24.1 % and 33.8 % missing data at each of the four assessments following baseline, respectively. Missing data was handled using Blimp – a multilevel imputation program (Enders et al., 2020; Enders et al., 2018; Keller and Enders, 2019). Variables associated with relationship satisfaction and its missingness were identified and included in the imputation model to reduce bias. Ten imputed datasets were created and used for analysis. The model was fitted with 16 parallel chains, default priors, 5000 warm-up iterations and 45,000 post-warm-up draws per chain per imputed dataset. Cohen's d was calculated by multiplying the respective unstandardized coefficients for time during and following the program from the multilevel piecewise model by the corresponding median number of weeks elapsed (7.71 from baseline to post and 20.5 from post to 4-month follow-up), and then divided by the baseline standard deviation.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics for relationship satisfaction are presented in Table S1. The visual inspection of trace plots indicated proper mixing and convergence for all models. All R^ were smaller than 1.05, indicating good model convergence.

3.1. Program completion

Fig. 2 presents the percentage of couples completing by each of the three sequential program phases by intervention condition. Of 145 contingent-coach couples, 124 were deemed “non-responsive” and offered additional coaching. However, less than half (n = 59) subsequently completed one or more coach calls.

Fig. 2.

Program phase completion by intervention condition.

The odds of couples completing by Observe, Understand, and Respond phases were not reliably different across conditions (i.e., the 95 % credible interval [CI] for an odds ratio included 1; see online supplement for odds ratios and CIs for paired comparisons). Further, the posterior distributions indicated that the probability of full-coach couples having the higher odds (i.e., odds ratio > 1) of completing Observe, Understand, and Respond phases, relative to automated-coach couples, was 28.4 %, 43.9 %, and 77.4 %, respectively; the probability of full-coach couples having the higher odds of completing Observe, Understand, and Respond phases, relative to contingent-coach couples, was 65 %, 70 %, and 92.7 %, respectively; and the probability of contingent-coach couples having the higher odds of completing Observe, Understand, and Respond phases, relative to automated-coach couples, was 15.6 %, 22.6 %, and 21.7 %, respectively.

3.2. Relationship satisfaction

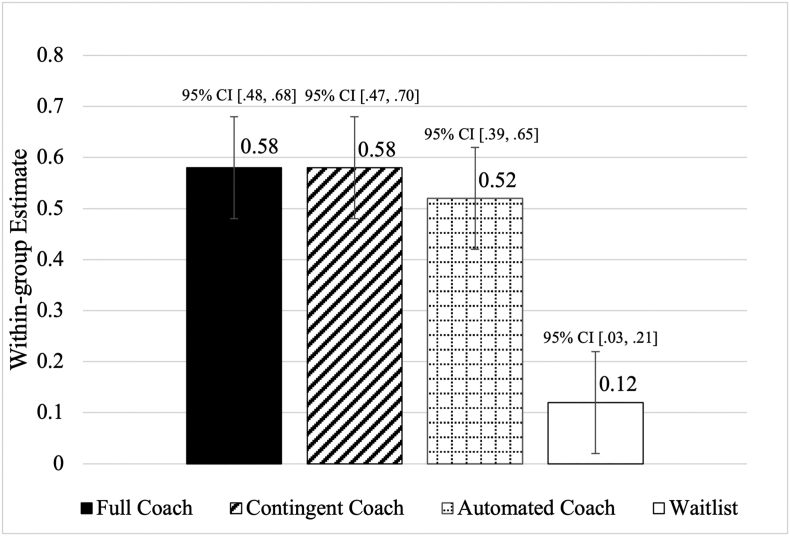

Table 1 summarizes the aggregated results from the 10 imputed datasets and Fig. 3 displays within-group effect sizes. From baseline to post-program, couples in all three intervention conditions, compared to waitlist control couples, experienced reliably greater gains in relationship satisfaction (between-group Cohens' d [d]full = 0.46, 95 % CI [0.33, 0.59]2; dcontingent = 0.47, 95 % CI [0.32, 0.61]; dautomated = 0.40, 95 % CI [0.25, 0.55]). No reliable differences were found across intervention conditions (dcontingent-full = −0.004, 95 % CI [−0.15, 0.14]; dautomated-full = 0.06, 95 % CI [−0.22, 0.10]; d contingent-automated = 0.06, 95 % CI [−0.10, 0.23]).

Table 1.

Differential program effects on relationship satisfaction during and following the program.

| B | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| Intercept (at post) | ||

| Waitlist | 10.50 | [9.90, 11.09] |

| Full Coach | 1.96 | [1.17, 2.75] |

| Contingent Coach | 1.80 | [0.91, 2.70] |

| Automated Coach | 1.90 | [0.99, 2.81] |

| Time 1 (Intervention Period) | ||

| Waitlist | 0.08 | [0.02, 0.14] |

| Full Coach | 0.30 | [0.21, 0.38] |

| Contingent Coach | 0.30 | [0.21, 0.39] |

| Automated Coach | 0.26 | [0.16, 0.36] |

| Time 2 (Follow-up Period) | ||

| Waitlist | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.05] |

| Full Coach | −0.01 | [−0.04, 0.03] |

| Contingent Coach | 0.01 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| Automated coach | 0.05 | [0.01, 0.09] |

| Random effects (couple-level) | ||

| Sd (Intercept) | 3.89 | [3.66, 4.13] |

| Sd (Time 1) | 0.24 | [0.19, 0.28] |

| Sd (Time 2) | 0.10 | [0.08, 0.12] |

| Cor (Intercept, Time 1) | 0.29 | [0.14, 0.42] |

| Cor (Intercept, Time 2) | −0.23 | [−0.35, −0.09] |

| Cor (Time 1, Time 2) | 0.05 | [−0.20, 0.36] |

| Random effects (coach-level) | ||

| Sd (Intercept) | 0.25 | [0.01, 0.69] |

| Sd (Time 1) | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| Sd (Time 2) | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.03] |

| Cor (Intercept, Time 1) | −0.08 | [−0.90, 0.85] |

| Cor (Intercept, Time 2) | −0.07 | [−0.90, 0.85] |

| Cor (Time 1, Time 2) | 0.02 | [−0.87, 0.88] |

Note. CI = credible interval. The intervention indicator variables (i.e., Full-coach, Contingent-coach, Automated-coach) were coded such that couples in the waitlist control = 0 and Full-/Contingent-/Automated-coach = 1 for those in the corresponding intervention assignment. Sd = standard deviation; Time during both the intervention (Time 1) and follow-up periods (Time 2) were centered around the date of posttest assessment.

Fig. 3.

Magnitude of within-group changes by the end of the program.

Note. CI = credible interval.

During the 4 months follow-up, compared to waitlist control couples, full-coach couples (d = −0.03, 95 % CI [−0.18, 0.12]3) and contingent-coach couples (d = 0.04, 95% CI [-0.12, 0.21]) maintained their gains, whereas automated-coach couples experienced some additional gains (d = 0.19, 95% CI [0.02, 0.36]). Changes were reliably different between full-coach and automated-coach couples (d automated-full = 0.22, 95% CI [0.05, 0.39]) but were not reliably different between full-coach and contingent-coach couples (d contingent-full = 0.07, 95% CI [-0.09, 0.24]), or between contingent-coach and automated-coach couples (d contingent-automated = −0.15, 95% CI [-0.31, 0.02]).

4. Discussion

The current study examined differential completion rates and effects of the online OurRelationship program delivered with three different levels of coaching. Overall, completion rates were comparable across conditions. Further, compared to waitlist couples, couples in all active intervention conditions demonstrated reliable improvements in relationship satisfaction that were maintained through the short follow-up period. This comparative effectiveness trial demonstrated that all intervention conditions were effective with subtle differences between conditions with regard to program completion and global relationship satisfaction improvements, providing meaningful implications for implementation.

4.1. Program completion

Completion rates were comparable across conditions. This is consistent with Levin et al. (2021)'s work on online acceptance and commitment therapy where no differences were found in program engagement between email prompts only condition and email plus phone coaching condition. These findings also complement other findings in the individual intervention literature, which suggest that minimal contact that is built into the program may play a critical role in engaging participant. Specifically, Berger et al. (2011) found a higher completion rate (56 %) for an internet-based treatment of depression that included scheduled e-mail contact with a therapist, compared to without any support (36 %). Similarly, Oromendia et al. (2016) found a lower drop-out rate and better treatment adherence for an internet-based treatment for panic disorder that included mandatory psychological support from a therapist, compared to with support only upon patients' request. Moreover, completion rates for the automated- and contingent-coach conditions in the current study were meaningfully higher than the no or low support condition in previous open trials (Roddy et al., 2018), suggesting that the automated reminders may have aided in program completion. Taken together, these findings suggest that minimal engagement such as tailored automated emails may be a promising approach to balancing affordability and scalability. Despite comparable completion rates, the posterior distributions suggested that the probabilities of full-coach couples having higher odds of completing the program than those in the other two conditions were >77 %. This indicates something unique about consistent coach contact that may not be fully replaced with the extensive automated reminders. The posterior distributions also suggested a 78 % probability that automated-coach couples had higher odds of completing the program than contingent-coach couples. Since less than half of the couples completed additional coach calls when given the opportunity, the contingent-coach condition may need to be more sensitive, trigger coaching earlier, or trigger alternative sources of support.

4.2. Improvements in relationship satisfaction

Despite slightly lower completion rates in conditions with reduced coaching, all three conditions created important and impactful improvements for couples that were maintained over the 4-month follow-up, with minimal differences between conditions. The overall lack of differences aligns with findings from studies in the individual intervention literature that have compared conditions involving therapeutic support from a professional or paraprofessional with conditions involving only automated and technical support (Levin et al., 2021; Karyotaki et al., 2021).

Effect sizes at post-program for the full-coach condition were slightly lower than those observed in previous trials (Doss et al., 2016; Doss et al., 2020; Hatch et al., 2022). Below, we compare within-group effect sizes, as not all trials have included a control condition. The within-group effect size for the full-coach condition in the current study (d = 0.58) was lower than in prior trials with low-income couples (d = 0.72; Doss et al., 2020) as well as nationally representative samples (ds = 0.61 and 0.96; Roddy et al., 2018, Doss et al., 2016). The smaller effect sizes observed may be due to the increasing number of couples served in each trial, from 151 in the first trial to 516 in the current study, which could have diluted the effects. More couples served has implications for project staffing, expansion of advertising to additional groups, and the training of additional coaches. Furthermore, each subsequent trial has enrolled a broader set of couples, and it is common for effect sizes to slightly decrease as interventions are scaled up (Parry et al., 2013). In contract, the effect sizes at post-program for the contingent- (d = 0.58) and automated-coach (d = 0.52) conditions in the current trial were similar in magnitude to the previously tested “low support” model (d = 0.52; Roddy et al., 2018), which speaks to the scalability of programs requiring less coach contact. Despite the slightly lower completion rates of these two conditions, they have the potential to produce a significant population-level impact when paired with moderate-sized effects.

4.3. Limitations

There are several limitations to note. First, we assessed a relatively short follow-up period; differences between conditions could become evident with time. Although previous trials of OurRelationship have demonstrated maintenance of gains through one year (Doss et al., 2019; Roddy et al., 2021) for the full-coach condition, it is unclear if this will be replicated with automated- and contingent-coach couples; however, it is notable that couples in the automated-coach condition continued to report gains after the program ended. Second, we used a waitlist control group. It is important to consider design differences when comparing effect sizes in the current study with other studies that employed a different design as the anticipation of receiving intervention may lead to under- or over-estimated effect sizes. Finally, it is possible that the repeated research assessments may have aided engagement in all intervention conditions.

4.4. Future directions

Given the minimum differences between coach conditions and significant improvements relative to the control group in all three conditions, OurRelationship can be offered with various levels of coaching. Therefore, the specific level of coaching that is most appropriate may vary by setting, resources, and the unique needs of the populations. From a cost-effectiveness perspective, omitting coaching would significantly decrease the cost of delivery; however, that option may be less appealing to some users – which could limit adoption of the intervention. The advent of artificial intelligence chatbots is an exciting future direction that could be incorporated into the OurRelationship program to further personalize the automated responses (Carlbring et al., 2023). Additionally, the contingent-coach condition may need adaptations to be more sensitive to couples falling behind so that more coach contact can be added more immediately when couples begin experiencing difficulties.

Furthermore, there may be characteristics of couples that would moderate these effects. For example, more satisfied couples may benefit more from the self-paced, automated-coach condition than would severely-distressed couples who might need a coach to help mediate challenging conversations. Alternately, comfort with technology could moderate effects such that those with higher technological comfort could derive less benefit from the inclusion of a coach. It is also possible that there would be differences across conditions in more narrow aspects of relationship functioning (e.g., communication, intimacy) or in the mechanisms that drove changes in relationship satisfaction. These and other potential moderators should be explored to inform future adaptations.

4.5. Conclusions

To optimize an intervention for implementation, considerations of affordability and scalability must be balanced with effectiveness (Collins, 2018). The amount of coaching offered has significant implications for both affordability and scalability of the OurRelationship program. While an intervention optimized for the lowest cost would select the automated-coach model for maximum scalability and affordability, contextual factors such as client and provider preferences should also be considered in future implementation efforts.

Funding sources

Funding for this project was approved by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Grant 90FM0063. MKR is supported by the Vanderbilt Faculty Research Scholars. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Publication fee was supported by Open Access Publication Equity Fund from University of Denver awarded to YL.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Brian Doss, PhD, senior author, is a coinventor of the intellectual property used in this study and an equity owner in OurRelationship LLC.

Acknowledgements

We thank John J. Dziak for his input regarding data analysis in the initial conceptualization of the paper. BDD is a coinventor of the intellectual property used in this study and an equity owner in OurRelationship LLC. We thank the project coordinators (Adriana Bracho and Samantha Joseph), coaches who provided services during this project, and couples who entrusted us with their relationships.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2023.100661.

This is consistent with the effect size of OurRelationship full-coach relative to waitlist reported in Hatch et al. (2022) (d = 0.46, 95 % CI [0.32, 0.60]).

This is consistent with the effect size of OurRelationship full-coach relative to waitlist reported in Hatch et al. (2022) (d = 0.02, 95 % CI [−0.14, 0.11]).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Berger T., Hämmerli K., Gubser N., Andersson G., Caspar F. Internet-based treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing guided with unguided self-help. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011;40:251–266. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.616531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett M.D., Mosher W.D. 2002. Cohabitation, Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage in the United States. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürkner P.-C. Brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2017;80:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P., Hadjistavropoulos H., Kleiboer A., Andersson G. A new era in internet interventions: the advent of chat-GPT and AI-assisted therapist guidance. Internet Interv. 2023;32 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2023.100621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A., Atkins D.C., Berns S., Wheeler J., Baucom D.H., Simpson L.E. Traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy for significantly and chronically distressed married couples. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:176. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L.M. Springer; New York: 2018. Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: The Multiphase Optimization Stragety (MOST) [Google Scholar]

- Collins L.M., Murphy S.A., Bierman K.L. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prev. Sci. 2004;5:185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss B.D., Benson L.A., Georgia E.J., Christensen A. Translation of integrative behavioral couple therapy to a web-based intervention. Fam. Process. 2013;52:139–153. doi: 10.1111/famp.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss B.D., Cicila L.N., Georgia E.J., Roddy M.K., Nowlan K.M., Benson L.A., Christensen A. A randomized controlled trial of the web-based OurRelationship program: effects on relationship and individual functioning. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016;84:285. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss B.D., Feinberg L.K., Rothman K., Roddy M.K., Comer J.S. Using technology to enhance and expand interventions for couples and families: conceptual and methodological considerations. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017;31:983. doi: 10.1037/fam0000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss B.D., Roddy M.K., Nowlan K.M., Rothman K., Christensen A. Maintenance of gains in relationship and individual functioning following the online OurRelationship program. Behav. Ther. 2019;50:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss B.D., Knopp K., Roddy M.K., Rothman K., Hatch S.G., Rhoades G.K. Online programs improve relationship functioning for distressed low-income couples: results from a nationwide randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020;88:283. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C.K., Keller B.T., Levy R. A fully conditional specification approach to multilevel imputation of categorical and continuous variables. Psychol. Methods. 2018;23:298. doi: 10.1037/met0000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C.K., Du H., Keller B.T. A model-based Imputation procedure for multilevel regression models with random coefficients, interaction effects, and nonlinear terms. Psychol. Methods. 2020;25:88. doi: 10.1037/met0000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk J.L., Rogge R.D. Testing the ruler with item response theory: increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the couples satisfaction index. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007;21:572. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgia Salivar E.J., Rothman K., Roddy M.K., Doss B.D. Relative cost effectiveness of in-person and internet interventions for relationship distress. Fam. Process. 2020;59:66–80. doi: 10.1111/famp.12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R.E., Vogt T.M., Boles S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health. 1999;89:1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch S.G., Knopp K., Le Y., Allen M.O., Rothman K., Rhoades G.K., Doss B.D. Online relationship education for help-seeking low-income couples: A Bayesian replication and extension of the OurRelationship and ePREP programs. Fam. Process. 2022;61:1045–1061. doi: 10.1111/famp.12710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins A.J., Blanchard V.L., Baldwin S.A., Fawcett E.B. Does marriage and relationship education work? A meta-analytic study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008;76:723. doi: 10.1037/a0012584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyotaki E., Efthimiou O., Miguel C., Genannt Bermpohl F.M., Furukawa T.A., Cuijpers P., Riper H., Patel V., Mira A., Gemmil A.W. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: a systematic review and individual patient data network meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry. 2021;78:361–371. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller B., Enders C. 2019. Blimp User’s Manual. Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiboer A., Donker T., Seekles W., Van Straten A., Riper H., Cuijpers P. A randomized controlled trial on the role of support in internet-based problem solving therapy for depression and anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015;72:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner J.A., Bradbury T.N. Patterns of change in marital satisfaction over the newlywed years. J. Marriage Fam. 2010;72:1171–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00757.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H., Nahum-Shani I., Lynch K., Oslin D., Murphy S.A. A“ SMART” design for building individualized treatment sequences. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012;8:21–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M.E., Krafft J., Davis C.H., Twohig M.P. Evaluating the effects of guided coaching calls on engagement and outcomes for online acceptance and commitment therapy. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2021;50:395–408. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2020.1846609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D., Cuijpers P., Lehman K. Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oromendia P., Orrego J., Bonillo A., Molinuevo B. Internet-based self-help treatment for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing mandatory versus optional complementary psychological support. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2016;45:270–286. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2016.1163615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry G.J., Carson-Stevens A., Luff D.F., Mcpherson M.E., Goldmann D.A. Recommendations for evaluation of health care improvement initiatives. Acad. Pediatr. 2013;13:S23–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles T.F., Slatcher R.B., Trombello J.M., Mcginn M.M. Marital quality and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014;140:140. doi: 10.1037/a0031859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddy M.K., Nowlan K.M., Doss B.D. A randomized controlled trial of coach contact during a brief online intervention for distressed couples. Fam. Process. 2017;56:835–851. doi: 10.1111/famp.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddy M.K., Rothman K., Doss B.D. A randomized controlled trial of different levels of coach support in an online intervention for relationship distress. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018;110:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddy M.K., Rhoades G.K., Doss B.D. Effects of ePREP and OurRelationship on low-income couples’ mental health and health behaviors: A randomized controlled trial. Prev. Sci. 2020;21:861–871. doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01100-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddy M.K., Walsh L.M., Rothman K., Hatch S.G., Doss B.D. Meta-analysis of couple therapy: effects across outcomes, designs, timeframes, and other moderators. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020;88:583. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddy M.K., Knopp K., Georgia Salivar E., Doss B.D. Maintenance of relationship and individual functioning gains following online relationship programs for low-income couples. Fam. Process. 2021;60:102–118. doi: 10.1111/famp.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman K., Roddy M.K., Doss B.D. Completion of a stand-alone versus coach-supported trial of a web-based program for distressed relationships. Fam. Relat. 2019;68:375–389. [Google Scholar]

- Slatcher R.B., Selcuk E. A social psychological perspective on the links between close relationships and health. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2017;26:16–21. doi: 10.1177/0963721416667444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock P.J., Schwartz C.R. The demography of families: A review of patterns and change. J. Marriage Fam. 2020;82:9–34. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trail T.E., Karney B.R. What’s (not) wrong with low-income marriages. J. Marriage Fam. 2012;74:413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Vehtari A., Gelman A., Simpson D., Carpenter B., Bürkner P.-C. Rank-normalization, folding, and localization: an improved R for assessing convergence of MCMC (with discussion) Bayesian Anal. 2021;16:667–718. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman M.A., Beach S.R., Snyder D.K. Is marital discord taxonic and can taxonic status be assessed reliably? Results from a national, representative sample of married couples. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008;76:745. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material