Abstract

Although regulatory T cells (Treg) are inhibitory immune cells that are essential for maintaining immune homeostasis, Tregs that infiltrate tumor tissue promote tumor growth by suppressing antitumor immunity. Selective reduction of tumor-infiltrating Tregs is, therefore, expected to activate antitumor immunity without affecting immune homeostasis. We previously reported that selective Treg depletion targeted by a C-C motif chemokine receptor 8 (CCR8) resulted in induction of strong antitumor immunity without any obvious autoimmunity in mouse models. Thus, herein, we developed a novel humanized anti-CCR8 monoclonal antibody, S-531011, aimed as a cancer immunotherapy strategy for patients with cancer. S-531011 exclusively recognized human CCR8 among all chemokine receptors and showed potent antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity activity toward CCR8+ cells and neutralization activity against CCR8-mediated signaling. We observed that S-531011 reduced tumor-infiltrating CCR8+ Tregs and induced potent antitumor activity in a tumor-bearing human-CCR8 knock-in mouse model. Moreover, combination therapy with S-531011 and anti-mouse programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) antibody strongly suppressed tumor growth compared with anti–PD-1 antibody alone with no observable adverse effects. S-531011 also depleted human tumor-infiltrating Tregs, but not Tregs derived from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. These results suggest that S-531011 is a promising drug for inducing antitumor immunity without severe side effects in the clinical setting.

Introduction

Immunotherapy is becoming a standard treatment for various types of cancers. Although immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), such as anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibodies, have shown clinical benefits in patients with cancer, most patients are not cured (1, 2). One of the proposed mechanisms of resistance to ICIs involves immunosuppressive cells, such as tumor-associated macrophage, myeloid-derived suppresser cells, and regulatory T cells (Treg), which are present in the tumor microenvironment and inhibit the function of effector T cells (3).

Tregs are inhibitory immune cells essential for maintaining immune homeostasis. Indeed, Tregs dysfunction caused by Foxp3 mutations or Tregs depletion results in the onset of severe autoimmune diseases in both humans and mice (4, 5). On the contrary, it has been reported that tumor-infiltrating Tregs assist tumor growth by suppressing antitumor immunity (6). These findings suggest that targeting tumor-infiltrating Tregs without affecting normal tissue-resident Tregs may be safer compared with targeting systemic Tregs. Therefore, a molecule that is selectively expressed in tumor-infiltrating Tregs can be considered a suitable target molecule for Treg-targeting cancer immunotherapy. Based on this rationale, we identified a C-C motif chemokine receptor 8 (CCR8), which is expressed mainly on tumor-infiltrating Tregs, as a target molecule (7).

CCR8 is a seven-transmembrane chemokine receptor (8, 9). C-C chemokine ligand (CCL) 1 is one of the ligands of CCR8 and has been reported to play a major role in potentiating Treg-suppressive activity (10). On the other hand, the functional involvement of CCR8 signaling in tumor-infiltrating Tregs is still unclear. Although some reports show that CCR8 signaling is not necessary for suppressing tumor immunity (11, 12), CCR8 blockade prevents the induction of Tregs and inhibits their suppressive function, which likely attenuates immunosuppression, reinvigorating antitumor immunity (13).

Previously, we reported that an anti-mouse CCR8 antibody showed strong antitumor effects, without causing autoimmunity, in a tumor-bearing mouse model (7). Other studies have also reported antitumor effects of anti-mouse CCR8 antibodies in mouse models (11, 14, 15). In humans, high CCR8 expression on tumor-infiltrating Tregs has been reported to be correlated with poor prognosis in several types of cancers (16, 17). These findings suggest that selective depletion of CCR8+ Tregs using an anti-human CCR8 antibody can potentially restore antitumor immunity, thereby exerting antitumor effects in patients with cancer.

In this study, we developed a novel humanized anti-human CCR8 antibody, S-531011, which has antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity against tumor-infiltrating CCR8+ Tregs and neutralization activity against the receptor signaling. We describe the in vitro and in vivo pharmacologic profiles of S-531011, which demonstrate that S-531011 has potential as a novel cancer immunotherapy agent.

Materials and Methods

Cells

HEK293T (RRID:CVCL_4401) and Rat-1 (RRID:CVCL_0492) were obtained from Takara Bio (Kusatsu, Japan) and RIKEN BRC (Tsukuba Japan), respectively. Expi293 (RRID:CVCL_D615) and CHO/G16 were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. KHYG-1 (RRID:CVCL_2976) and Ramos (RRID:CVCL_0597) were obtained from JCRB Cell Bank. The 293c18 (RRID:CVCL_6974), CT26.WT (RRID:CVCL_7256), and EMT6 (RRID:CVCL_1923) cell lines were obtained from ATCC. Colon26 (RRID:CVCL_0240) was obtained from Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Tohoku University (Sendai, Japan). HEK293T and Rat-1 were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Ramos and KHYG-1 cells were cultured in an RPMI-1640 medium with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine containing 10% FBS and MEM. In KHYG-1 cells, 100 units/mL of recombinant human IL2 (PeproTech) were added to the culture medium. CT26.WT, Colon26, and EMT6 were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. The method for the generation of gene-transfected cells is described in the Supplementary Materials. All cell lines were used within 10 passages after thawing. Cell authentication was routinely performed by comparing cell morphology and growth properties with suppliers’ data. The cells were not tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Animals

Female A/J mice (RRID:MGI:2160468) were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. Female-humanized CCR8 knock-in (hCCR8 KI) mice were supplied by the Aburahi Research Center (Shionogi TechnoAdvance Research Co., Ltd). The method for the generation of hCCR8 KI mouse is described in the Supplementary Material. The animal study protocol was approved by the director of the institute after reviewing the protocol by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shionogi & Co., Ltd. in terms of the 3R (Replacement/Reduction/Refinement) principle.

Human samples

Fresh tumor tissues from patients with lung cancer or ovarian cancer were provided by Osaka University Hospital (Osaka, Japan) or Kansai Rosai Hospital (Amagasaki, Japan). These tissues were obtained from the first surgery. The patients received no neoadjuvant therapy. Peripheral blood samples were also obtained from healthy donors. All participants provided written informed consent before sampling. The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Osaka University Hospital (#13266-24) and the Shionogi Human Research Ethics Committee (#2021-003).

Construction of anti-human CCR8 antibodies

The gene encoding full-length human CCR8 (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot: P51685) was introduced into A/J Jms Slc female mice for immunization. Immunization was repeated twice at 2-week intervals and boosted by intraperitoneally administering human CCR8-expressing Expi293 cells 1 week after final immunization. Splenocytes and mouse myeloma cells (p3×6363-Ag8., Tokyo Oncology Institute) were fused using the polyethylene glycol (PEG) method (18), and selection was made in a medium containing hypoxanthine, aminopterin, and thymidine. The anti-human CCR8 binding and human CCL1-CCR8 neutralizing assays were simultaneously performed to isolate human CCR8-specific strong-neutralizing antibodies. The culture supernatant of hybridoma cells was reacted with human CCR8-expressing Expi293 cells and human CCR4-expressing Expi293 cells, and then detected using Alexa488-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the Mirrorball antibody discovery system. Expi293 cells were transfected with human CCR8-pcDNA3.4 or human CCR4-pcDNA3.4 using FectoPRO reagent (PolyPlus) to generate transient CCR8- or CCR4-expressing cells. For anti-human CCR8-neutralizing antibodies, the culture supernatant sufficiently reacted with human CCR8 expressing 293 cells in which a Ca2+ indicator was incorporated beforehand. Ca2+ influx was then measured after the addition of 200 nmol/L human CCL1 (BioLegend) with a Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader (FLIPR, Molecular Devices). The sequence of hybridoma clones exhibiting particularly strong CCR8-binding activity and neutralizing activity was identified, and their complementarity-determining regions were grafted onto the human framework. Affinity maturation of humanized antibodies was performed by mutagenesis and S-531011 was selected as a result of binding activity for native human Tregs, ADCC activity, neutralizing activity, and productivity.

Binding affinity assay

Goat anti-human IgG solutions (RRID:AB_2337541, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) were prepared at 30 μg/mL. These solutions were added to a tube containing 200 mg polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) particles (Sapidyne Instruments) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (blocking solution) was added. After the blocking reaction for 1 hour, the supernatant was discarded and the blocking solution was added. The concentration of S-531011 was adjusted from 0.08 to 0.3 nmol/L and mixed with several concentrations of human CCR8-expressing HEK293T cells for overnight incubation. The supernatants from which the cells had been removed by centrifugation were collected. The supernatants of preincubated mixtures were passed over goat anti-human IgG-coated PMMA particles mounted in the flow cell of the KinExA 4000 (Sapidyne Instruments) to facilitate capturing of unbound S-531011 to the solid support. Furthermore, by flowing a fluorescein-labeled antibody (Goat anti-human IgG H&L [DyLight 650], RRID:AB_10679700, Abcam) through the flow cell, the amount of bound S-531011 was detected by fluorescence. The fluorescence signals were measured, and data were analyzed using n-Curve analysis in the KinExA Pro software version 4.4.26 (Sapidyne Instruments).

FLIPR calcium mobilization assays for neutralizing activity against the CCL1–CCR8 interaction

The neutralization activity of S-531011 was evaluated using FLIPR calcium mobilization assays with human CCR8-expressing HEK293T cells. The cells were plated onto a 384-well amine-coated black clear-bottomed assay plate in 10% FBS-DMEM overnight in a CO2 incubator. After aspirating the medium, Cal-520 calcium dye (AAT Bioquest) was added at a final concentration of 4 μmol/L in assay buffer (HBSS with 20 mmol/L HEPES; pH 7.4; 2 mmol/L probenecid). Then, each concentration of S-531011 was added. After incubation for 100 minutes, the plate was washed with assay buffer. The assay buffer was removed and the plate was incubated for 15 minutes. The solution of human CCL1 prepared with the assay buffer containing 0.05% pluronic acid was added to each well in the assay plate at a final concentration of 60 nmol/L using the dispensing head of FLIPR while simultaneously monitoring whole-well fluorescence (excitation, emission λ; 470–495, 515–575 nm, respectively) at 15 minutes. The delta signal (relative fluorescence units, RFU) of each well was calculated by the subtraction of the minimal signal from the maximal signal in each experiment. EC50 values were analyzed by curve fitting using the XLFit software version 5.3.1.3 (IDBS).

In vitro ADCC assay against a human CCR8-expressing cell line

To assess cell death mediated by natural killer (NK) cells in the presence of S-531011, human CCR8-expressing Rat-1 cells were labeled with Calcein-AM (Dojindo) at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL and incubated with human FcγRIIIA-expressing KHYG-1 cells at a ratio of 1:30 in the presence of S-531011 or human IgG1 isotype control antibody (Clone QA16A12, BioLegend) at 37°C for 90 minutes. For measurement of maximum or spontaneous calcein release, Triton X-100 solution or assay buffer was added without human FcγRIIIA-expressing KHYG-1 cells, respectively. After the incubation, the fluorescent signal (excitation: 485 nm, emission: 535 nm) of calcein released from the dead cells in the culture medium was measured using a SpectraMax M3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Data were expressed as RFU. EC50 values for ADCC of S-531011 against human CCR8-expressing cells were determined from the dose–response curves of corrected RFU (RFU in S-531011 − RFU in human IgG1 isotype control antibody) using the XLFit software version 5.3.1.3 (IDBS).

Complement-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (CDC) assay

In vitro CDC of S-531011, rituximab (R&D Systems), and human IgG1 isotype control antibody was determined using Ramos-hCCR8 as target cells and human serum as a source of complement. S-531011, rituximab, and the isotype control were diluted with human serum, and these diluted solutions were added to a cell suspension in a 1:1 ratio. The final serum concentration was 50% for S-531011 or rituximab and 25% for the isotype control antibody. The culture plate was incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Dead cells were labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and cytotoxic activity of each antibody was measured using an LSRFortessa X-20 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The percentage of dead cells (%) was calculated as:

In vivo tumor-infiltrating Treg depletion assay

A total of 5.9 × 105 CT26.WT cells, 6.0 × 105 Colon26 cells, or 3.0 × 105 EMT6 cells were subcutaneously implanted into the back of hCCR8 KI mice. Multiple doses of S-531011 were administered intravenously via the tail vein 8 days after tumor inoculation. Four or 7 days after antibody administration, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia, and the tumor was excised. Dissociated tumor cells were obtained from the excised tumor using the mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Red blood cells in the sample were lysed by treatment with BD Pharm Lyse (BD Biosciences) and then the dissociated cells were stained with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After staining with rat anti-human CCR8 antibody (clone: 3-3F) for 30 minutes followed by cell washing, the cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 647 anti-rat IgG (RRID:AB_2340696, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and washed with assay buffer, and then treated with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (RRID:AB_394656, BD Biosciences). The cells were stained with antibodies for cell-surface antigens and treated with Transcription Factor Buffer Set (BD Biosciences) for intracellular staining. The stained cells were detected using a MACSQuant Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec).

In vivo antitumor assay

In a CT26.WT-bearing mouse model, 3.35 × 105 CT26.WT cells were subcutaneously implanted into the back of hCCR8 KI mice. Human IgG1 isotype control antibody or S-531011 was administered intravenously via the tail vein twice on days 4 and 11 at the indicated doses. In the EMT6-bearing mouse model, 3 × 105 EMT6 cells were subcutaneously implanted into the back of hCCR8 KI mice. These mice were administered with 100 μg S-531011 or anti-mouse PD-1 antibody (RRID:AB_10949053, clone RMP1-14, Bio X cell) twice (5 and 12 days) after implantation. Mice in the control group were administered acetate buffer. To evaluate the effect of combination therapy with S-531011 and the anti-mouse PD-1 antibody, 3.5 × 105 CT26.WT cells were subcutaneously implanted into the back of hCCR8 KI mice. S-531011 and/or the anti-mouse PD-1 antibody was administered intravenously via the tail vein twice on day 5. The body weight of the mice was determined using an electronic balance and the length and width of the tumor was measured with an electronic caliper twice or three times a week after group assignment. The tumor volume was calculated using the following formula:

Human blood and tumor sample preparation

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated from whole blood by gradient density centrifugation using a BD Vacutainer CPT or Lymphoprep (Axis Shield). Tumor samples were minced and enzymatically dissociated using a Human Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cell suspensions were purified using Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) gradient centrifugation. The obtained cells were stocked in a liquid nitrogen container until use.

Flow cytometry

In human sample analysis, single-cell suspensions were stained with Zombie NIR Fixable Viability Dye (BioLegend) and were FcR blocked (Human TruStain FcX; BioLegend). After washing, the cells were surface stained. For intracellular staining, the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. The cells were analyzed using the LSRFortessa X-20 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

In vitro binding assay against human tumor-initiating cells (TIC)

The thawed TICs were stained with Zombie NIR Fixable Viability Dye and FcR blocked and then incubated with 5 μg/mL biotinylated S-531011 or human IgG1 isotype control antibody for 1 hour at 4°C. After washing, the cells were stained with 2 μg/mL fluorescence-conjugated streptavidin and cell-surface marker antibodies. Intracellular staining was conducted using a FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set. In vitro binding of S-531011-biotinylated against human TICs was measured using the LSRFortessa X-20 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

In vitro ADCC assay against tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in human tumor tissues

NK cells were isolated from fresh healthy donor PBMCs using a Human NK Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cells were cultured overnight with or without 500 U/mL IL2 (Teceleukin, Shionogi) when used in the lung or ovarian tumor assay, respectively. The thawed tumor-infiltrating cells were cocultured at a ratio of 1:1 with activated allogenic NK cells overnight with S-531011, mogamulizumab (anti-human CCR4 antibody, Kyowa Kirin), or with human IgG1 isotype control antibody. CD3+CD4+Foxp3+ cells (Tregs) and CD3+CD4+Foxp3− cells (conventional T; Tconv cells) in CD45+ lymphocytes were analyzed using flow cytometry. The assays were performed using TICs from six patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) or five patients with ovarian cancer and NK cells from healthy donors.

In vitro Treg depletion assay against Tregs in human PBMCs

Human PBMCs from eight healthy donors were incubated overnight at 37°C with multiple concentrations of S-531011, mogamulizumab (Absolute antibody), and human IgG1 isotype control antibody. CD4+CD45RA−FoxP3+ cells (Tregs) in CD3+ T cells were analyzed using flow cytometry. The reduction in Tregs by S-531011 or mogamulizumab treatment in each donor was evaluated as a percentage against the control, corrected by the human IgG1 isotype control antibody-treated samples.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 8 (RRID:SCR_002798, GraphPad Software) and SAS version 9.4 (RRID:SCR_008567, SAS Institute, Inc.). Mann–Whitney U test was used for two-group comparisons, and Dunnett multiple comparison test using a one-way ANOVA model was used for groups of three or more groups.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Results

In vitro biological activity of anti-human CCR8 antibody, S-531011

To generate an anti-human CCR8 antibody suitable for cancer immunotherapy, we screened monoclonal anti-CCR8 IgG1 antibodies and found a novel anti-human CCR8 antibody S-531011 that showed high binding affinity to CCR8, ADCC activity, and neutralization activity against CCR8-mediated signaling.

We first examined the binding affinity of S-531011 to human CCR8 and its variant with the most frequent amino acid substitution, CCR8 (A27G) using human CCR8- or CCR8 (A27G)-expressing HEK293T cells. Kd values of S-531011 for human CCR8- and CCR8 (A27G)-expressing cells were 18.6 and 26.4 pmol/L, respectively (Table 1). We then evaluated the binding selectivity of S-531011 to various human chemokine receptors other than CCR8, and its binding activity against human immune-checkpoint molecules (PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4) as well as mouse CCR8. S-531011 did not bind to the other chemokine receptors and immune-checkpoint molecules (Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B). It also barely bound mouse CCR8; however, S-531011 exhibited binding activity for human CCR8 (Supplementary Fig. S1C and S1D).

Table 1.

In vitro biological activities of S-531011.

| Profiles | Binding affinity (Kd; pmol/L) | ADCC (EC50; ng/mL) | Neutralization (IC50; ng/mL) | CDC (EC50; μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-531011 | 18.6 | 6.54 | 20.0 | >300 |

Note: CDC was not inhibited over 50% by S-531011 at the highest concentration tested (300 μg/mL).

To investigate the binding of S-531011 to CCR8 expressed on Tregs in human tumor tissues, we evaluated the in vitro binding of S-531011 to tumor-infiltrating cells obtained from surgical specimens of lung adenocarcinoma. S-531011 bound to the Tregs detected as the CD45+CD3+CD4+FoxP3+CD25+ population, but not to non-Tregs detected as the CD45+CD3+CD4+FoxP3−CD25− population of the tumor-infiltrating cells (Fig. 1A and B). These results indicate that S-531011 has a potent binding affinity and selectivity to endogenous human CCR8 expressed on tumor-infiltrating Tregs.

Figure 1.

In vitro biological profiles of S-531011. Representative histogram of binding of S-531011 to tumor-infiltrating CD45+CD3+CD4+Foxp3−CD25− cells (A) and CD45+CD3+CD4+Foxp3+CD25+ cells (B), and representative figures of ADCC (C), neutralization (D), and CDC (E). In C, data were expressed as corrected RFU (RFU in S-531011 – RFU in human IgG1 isotype control antibody). In D, the percentage RFU of effectivity was calculated using the following formula: % RFU = [1 − {S-531011 – Control (+)} / {Control (−) – Control (+)}] × 100. Control (−) represents the average RFU value in the absence of S-531011 and Control (+) represents the average RFU value in the presence of 4.4 μg/mL (maximum concentration) S-531011. In E, dead cell (%) was calculated as DAPI-positive cells/target cells × 100.

To investigate whether S-531011 has ADCC activity, CDC activity against CCR8-expressing cells, and neutralizing activity against CCL1-CCR8 signal, we evaluated its cytotoxic activity and CCL1 signal inhibition using human CCR8-expressing cells lines (Table 1; Fig. 1C–E). The ADCC EC50 value of S-531011 was 6.54 ng/mL, and the neutralizing activity IC50 value was 20.0 ng/mL. The CDC EC50 value was >300 μg/mL. These data indicate that S-531011 has potent ADCC activity and neutralizing activity against CCL1 signal, but not CDC activity.

Generation of hCCR8 KI mice and pharmacokinetics of S-531011 in hCCR8 KI mice

The pharmacologic evaluation of S-531011 in wild-type mice is inappropriate because S-531011 binds very weakly to mouse CCR8 (Supplementary Fig. S1C and S1D). Therefore, we generated hCCR8 KI mice, in which the mouse Ccr8 gene was replaced by the human CCR8 gene (Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2B). Human CCR8 protein expression in tumor-infiltrating Tregs was confirmed in the CT26.WT-bearing hCCR8 KI mice using flow cytometry. Treg-selective expression of CCR8 in the CT26.WT-bearing hCCR8 KI mice was similar to that observed in human tumor tissues (Supplementary Fig. S2C).

To clarify the pharmacokinetics of S-531011, we evaluated serum and tumor concentrations of S-531011 after a single intravenous administration of S-531011 in CT26.WT tumor-bearing hCCR8 KI mice. The concentrations of S-531011 in the serum 168 hours after S-531011 administration dosed at 0.05, 0.5, and 5 mg/kg were 11.2, 306.0, and 4,770.0 ng/mL, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3A), and that in the tumor at 0.5 and 5 mg/kg were 219 and 2640 ng/mL, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3B). The concentration in the tumor 168 hours after the administration of 0.05 mg/kg S-531011 was below the lower limit of quantification (<10 ng/mL).

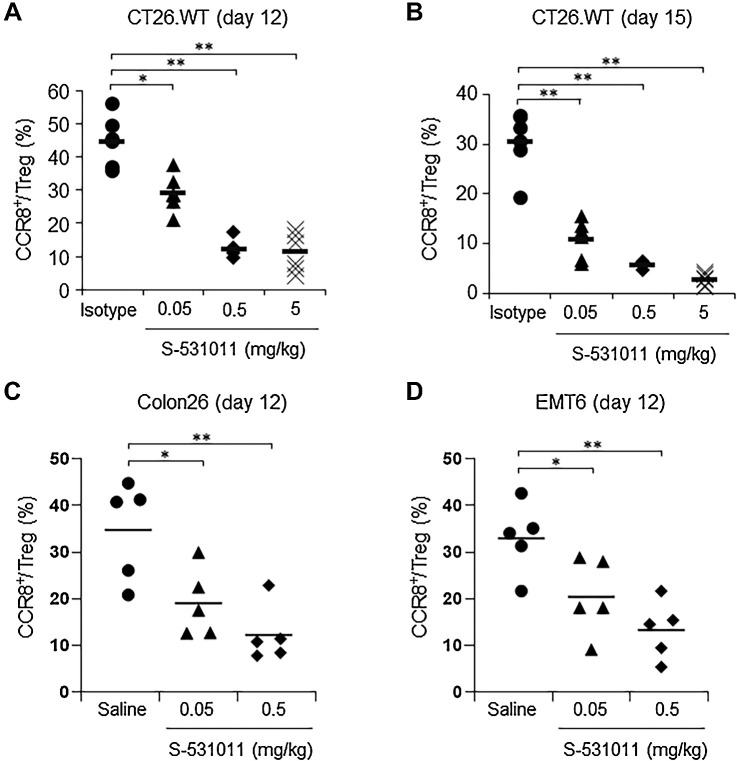

In vivo Treg depletion by S-531011 in tumor-bearing mouse models

Although CCR8+ cells were reduced by S-531011 in flow cytometry analysis, it is unclear whether the reduction was caused by the depletion of CCR8+ cells or by masking of CCR8 epitopes with S-531011. Therefore, we generated an additional anti-CCR8 antibody capable of detecting human CCR8 after S-531011 treatment in hCCR8 KI mice. We generated an anti-human CCR8 monoclonal antibody (clone: 3-3F), which did not compete with S-531011 (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Next, we evaluated whether S-531011 depletes tumor-infiltrating CCR8+ Tregs in tumor-bearing hCCR8 KI mice using the 3-3F antibody. S-531011 was administered as a single intravenous injection to the CT26.WT tumor-bearing hCCR8 KI mice at doses 0.05, 0.5, or 5 mg/kg. At 4 or 7 days after administration, tumors were excised, and the proportion of CCR8+ cells in the tumor-infiltrating Tregs was analyzed using flow cytometry. The proportion of CCR8+ Tregs to total Tregs was reduced in the S-531011–treated groups compared with that in the isotype control-treated group in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A and B). Similar to the results for the CT26.WT tumor-bearing model, S-531011 treatment resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in CCR8+ cells in Colon26 and EMT6 tumor-bearing models (Fig. 2C and D). These results suggest that S-531011 can deplete CCR8+ Tregs in tumor tissues.

Figure 2.

In vivo CCR8+ Treg depletion activity of S-531011 in various tumor models. CT26.WT cells (A and B), Colon26 cells (C), or EMT6 cells (D) were subcutaneously implanted into the back of hCCR8 KI mice. Indicated doses of S-531011, 5 mg/kg isotype IgG1 antibody, or saline were administered intravenously via the tail vein 8 days after tumor inoculation. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were obtained from the excised tumor after 4 days (A, C, and D) or 7 days (B) after drug administration. The proportion of CCR8+ Tregs in total Tregs, which were live CD45+TCRβ+CD4+CD8a−CD25+Foxp3+ cells, was analyzed using flow cytometry. Symbols show the value of each sample and the bar shows the mean for each group (n = 6). A and B: *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.0001 (vs. 5 mg/kg isotype IgG1-treated group, Dunnett multiple comparison test); C and D: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (vs. saline-treated group, Dunnett multiple comparison test).

In vivo antitumor effect of S-531011 in tumor-bearing mouse models

We then evaluated the antitumor effect of S-531011 in several murine models. In CT26.WT tumor-bearing hCCR8 KI mice, tumor volumes were significantly smaller in the 0.15, 5, and 15 mg/kg S-531011-administered groups than in the control antibody-administered group (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, respectively; Fig. 3A; Supplementary Fig. S5A). We also investigated the antitumor effect of S-531011 against the EMT6 tumor-bearing mice and observed that S-531011 showed potent antitumor activity in EMT6 tumors. With regard to anti-PD-1 antibody, the antitumor activity was moderate (Fig. 3B; Supplementary Fig. S5B).

Figure 3.

In vivo antitumor activity of S-531011 in a CT26.WT or EMT6 tumor-bearing mouse model. CT26.WT cells (A, C, and D) or EMT6 cells (B) were subcutaneously implanted into the back of hCCR8 KI mice. A, S-531011 or 15 mg/kg isotype IgG1 antibody was administered intravenously on days 4 and 11. B, S-531011 or anti-mouse PD-1 antibody or vehicle was administered intravenously on days 5 and 12. C and D, S-531011 and/or anti-mouse PD-1 antibody or isotype IgG1 antibody was intravenously administered on day 5. Tumor volume (A–C) and body weight of mice (D) were measured. Tumor volume (cm3) was calculated using the following formula: [(Length × Width × Breadth) ÷ 2]. Each point and bar showed the mean and SE of tumor volume, respectively (A, n = 10; B, n = 10; C, n = 9). A: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 (vs. isotype IgG1 group on day 19; Dunnett multiple comparison test). B: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001 (vs. control group at 28 days after implantation, Dunnett multiple comparison test); #, P < 0.05 (vs. anti–PD-1 antibody-treated group at day 28, Mann–Whitney U test); C: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001 (vs. isotype IgG1-treated group at day 21, Dunnett multiple comparison test); #, P < 0.05 (vs. S-531011-treated group at day 21, Mann–Whitney U test). Tumor growth curves for each individual mouse in each group are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

Next, we investigated combination therapy with S-531011 and anti-mouse PD-1 antibody in the CT26WT-bearing hCCR8 KI mouse model. The combination therapy significantly suppressed tumor volume compared with S-531011 or anti-mouse PD-1 antibody alone (P < 0.05; Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S5C). There was no reduction in body weight or worsening of the general condition in the single or combined treatment groups (Fig. 3D). Taken together, S-531011 had potent antitumor activity in CT26WT and EMT6 mouse models, and the combined treatment of S-531011 with anti-mouse PD-1 antibody enhanced the antitumor effects without inducing observable adverse effects.

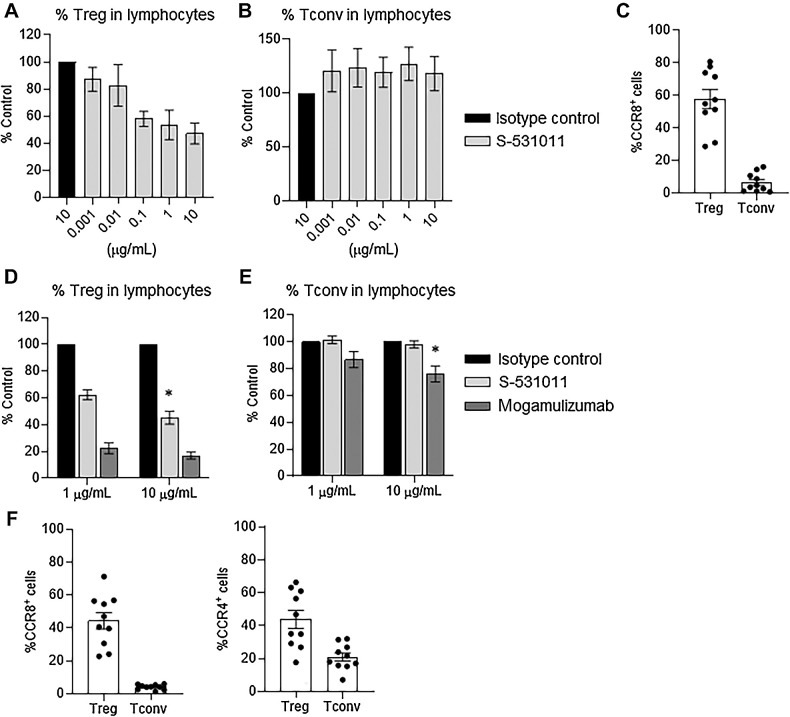

In vitro Treg depletion by S-531011 in human tumor tissues

To investigate the ADCC effect of S-531011 on Tregs derived from human tumor tissues, we first evaluated the proportion of CCR8+ cells in tumor-infiltrating Tregs as well as in Tconv cells. According to flow cytometry analysis, average CCR8+ rates were 58% and 7% in Tregs and Tconv cells, respectively, in ovarian cancers, and 44% and 4% in Tregs and Tconv cells, respectively, in NSCLC (Fig. 4C–F). Next, we investigated whether S-531011 could deplete Tregs in human tumor tissues in vitro. CD45+ cells in ovarian cancer tissues were isolated and cocultured with PBMC-derived NK cells. The proportion of Tregs was decreased by S-531011 in a dose-dependent manner, but that of Tconv cells was not affected (Fig. 4A and B). We also investigated the effect of S-531011 on immune cells in NSCLC tissues. Reduction in the proportion of Tregs, but not that of Tconv cells, in lymphocytes was observed at treatment doses of 1 and 10 μg/mL S-531011 (Fig. 4D and E). The anti-human CCR4 antibody, mogamulizumab, which was used as a positive control, depleted both Tregs and Tconv cells (Fig. 4D and E). These results suggest that S-531011 can deplete Tregs in tumor-infiltrating cells more selectively than mogamulizumab.

Figure 4.

In vitro tumor-infiltrating Treg depletion activity of S-531011 in human ovarian cancer and NSCLC tissues. A, B, D, and E: NK cells were cultured for 24 hours with 500 U/mL IL2 when used in the lung tumor assay (D and E) or without IL2 when used in the ovarian tumor assay (A and B). Dissociated tumor cells from patients with NSCLC or ovarian cancer were cocultured 1:1 with allogenic NK cells for 24 hours with S-531011. The proportion of CD3+CD4+Foxp3+ cells (Treg) and CD3+CD4+Foxp3− cells (Tconv) in CD45+ lymphocytes was measured using flow cytometry. The reduction in Treg or Tconv for each donor was evaluated by %Control = (the proportion in S-531011 or mogamulizumab-treated sample) / (the proportion in isotype control antibody-treated sample) × 100. Each proportion in the isotype control group of each sample was set to 100%. Each bar showed the mean ± SE of %Control (A, B, n = 6; D, E, n = 5). C and F, The CCR8-expressing cells in Treg and Tconv in human ovarian cancer (C) or NSCLC tissues (F) were analyzed using flow cytometry. Symbols show the value of each sample and the bar shows the mean ± SE (n = 10). D and E: *, P < 0.05 (vs. 10 μg/mL isotype control-treated group, Dunnett multiple comparison test using the values before correction to %Control).

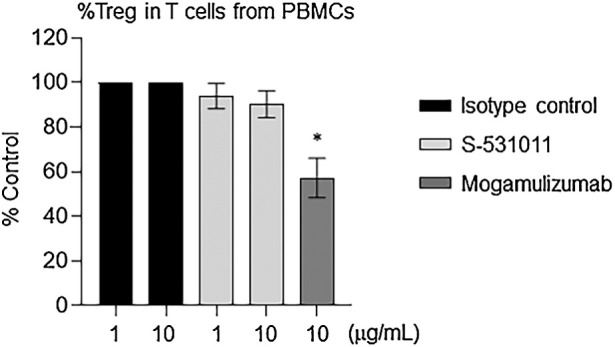

In vitro Treg depletion by S-531011 in human PBMCs

To ensure the safety of S-531011, we evaluated the effect of S-531011 on normal Tregs derived from PBMCs, as systemic elimination of Tregs causes autoimmune-like side effects (4, 5). We cultured PBMCs in the presence of S-531011 and determined the proportion of Tregs in PBMCs. S-531011, up to a dose of 10 μg/mL, did not change the proportion of Tregs, whereas mogamulizumab significantly decreased the proportion of Tregs (P < 0.001; Fig. 5). These results suggest that S-531011 does not deplete normal Tregs in human PBMCs.

Figure 5.

Proportion of Tregs in T cells after treatment with S-531011. Human PBMCs were incubated overnight at 37°C with the indicated concentration of S-531011, mogamulizumab, and isotype control antibody. Peripheral blood Tregs were detected as CD45+CD3+CD4+CD45RA−FoxP3+ (Treg) population using flow cytometry. %Control = (the proportion in S-531011 or mogamulizumab-treated sample)/(the proportion in isotype control antibody-treated sample) × 100. Each proportion in the isotype control group of each sample was set to 100%. Each bar showed the mean ± SE of %Control (n = 8). *, P < 0.001 (vs. 10 μg/mL isotype control-treated group, Dunnett multiple comparison test using the values before correction to %Control).

Discussion

In the present study, we developed a novel humanized anti-human CCR8 IgG1 antibody, S-531011, which exhibits potent ADCC activity against CCR8-expressing cells and neutralization activity against the CCL1–CCR8 signal. S-531011 depleted tumor-infiltrating CCR8+ Tregs and showed potent antitumor activity in a tumor-bearing hCCR8 KI mouse model. Furthermore, S-531011 selectively depleted Tregs in human tumor tissues without affecting normal Tregs in human PBMCs.

S-531011 exhibits strong ADCC activity that can deplete CCR8+ Tregs and induce antitumor effects. Anticancer agents, such as rituximab, trastuzumab, and avelumab, have ADCC activity and are thought to exert antitumor effects by depleting cells expressing target molecules. These antibodies have been reported to have ADCC activity values (EC50) of 1.1–19 ng/mL against target-expressing cells (19, 20), indicating that ADCC activity of S-531011 was comparable to that of clinically effective ADCC-mediated antibody drugs. It has been reported that the immunosuppressive activity of CCR8+ Tregs is higher than that of CCR8− Tregs (11, 15). We recently reported that CCR8+, but not CCR8−, Tregs suppress the cytotoxic activity of CD8 T cells and that eliminating CCR8+ cells enhances the activity of CD8 T cells (21). This finding suggests that depleting CCR8+ Tregs alone is sufficient to release intratumoral immunosuppression. In the present study, S-531011 depleted ∼50% of Tregs, wherein the percentage of CCR8+ cells in tumor-infiltrating Tregs was as high as 50% (Fig. 4), suggesting that S-531011 may have potentially depleted the entire CCR8+ Treg population. Consequently, our results suggest that S-531011 induces a potent intratumoral immune response by selectively depleting CCR8+ Tregs. Moreover, we found that reduction of CCR8+ Tregs in tumor by a single treatment of S-531011 lasted for at least 1 week after antibody administration (Fig. 2) and exerted a potent antitumor effect in tumor-bearing hCCR8 KI mouse models (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S5). Taken together, these findings suggest that S-531011 depletes tumor-infiltrating CCR8+ Tregs and that it can exert potent antitumor effects in patients with cancer.

S-531011 selectively depleted CCR8+ Tregs, but not CD4 Tconv cells in tumor tissues. CCR4 is a chemokine receptor highly expressed in Tregs (22). Clinical trials that examined the Treg depletion effect of the anti-CCR4 antibody mogamulizumab in solid tumors have been conducted (23, 24). Mogamulizumab depleted not only circulating CCR4+ Tregs but also CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells in patients with recurrent solid tumors, resulting in a reduced antitumor immune response (23, 24). Because the depletion of effector T cells can lead to a decrease in the antitumor effect of the CCR8 antibody (7), we evaluated whether S-531011 could deplete effector T cells. S-531011 did not deplete CD4 Tconv cells (Fig. 4B–E), suggesting that S-531011 would not decrease the antitumor immune response.

On the other hand, the contribution of the neutralizing activity of S-531011 to its antitumor effect cannot be adequately evaluated in an hCCR8 KI mouse model as mouse CCL1 did not induce downstream signals of human CCR8 in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S2D), suggesting that human CCR8 signals do not work properly in vivo in hCCR8 KI mice. It has been reported that no antitumor effect was observed in nanobodies with CCL1 signal inhibitory activity (12). On the other hand, CCL1–CCR8 signals have been reported to enhance the immunosuppressive function of Tregs (10). We previously reported that an anti-mouse CCR8 antibody, which exhibits neutralization activity against CCL1–CCR8 signal without ADCC activity, still exerted antitumor activity in a tumor-bearing mouse model, although the activity was apparently weaker than that of anti-mouse CCR8 antibody retaining ADCC activity (7). Therefore, these findings suggest that the anti-CCR8 antibody exhibits its antitumor effect mainly by depleting Treg, although neutralizing activity may also be partially involved. The contribution of neutralizing activity in the antitumor effect of S-531011 in humans needs to be explored in the future.

S-531011 plus anti–PD-1 antibody is a promising combination therapy for patients with cancer. We observed an additional effect with the combined treatment of S-531011 and an anti-mouse PD-1 antibody in the hCCR8 KI mouse model (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S5C). In CT26WT tumor-bearing mice, tumor-infiltrating CD8 T and CD4 T cells expressed PD-1 and were confirmed to express PD-1 even after the administration of CCR8 antibodies (7). We previously reported that the CCR8 antibody exerts an antitumor effect through a mechanism of action different from that of the anti–PD-1 antibody (7). Potent and less exhausted CD4 and CD8 effector T cells are induced by depleting CCR8+ Tregs, whereas anti–PD-1 antibody inhibits T-cell immunosuppression by PD-L1 expressed in cancer cells and myeloid cells, inducing an antitumor effect. It has also been reported that anti–PD-1 antibody could proliferate Tregs and enhance immunosuppressive activity (25, 26). In addition, it is also known that PD-1+ Tregs are involved in hyper-progressive disease observed after administration of anti–PD-1 antibody in several patients with cancer (27). These findings suggest that the combination strategy of PD-1 and CCR8 antibodies is a reasonable and promising treatment for patients with cancer.

As previously described, systemic Treg depletion leads to severe autoimmune diseases in mice (4). Mogamulizumab has also been reported to produce autoantibodies by depleting Tregs in the blood, resulting in skin-related adverse events (28). Our data that mogamulizumab decreased the proportion of Tregs in PBMCs (Fig. 5) are consistent with the results of clinical trials (20, 21). In contrast, we found no depletion effect of S-531011 on Tregs in PBMCs (Fig. 5). In a previous report, no autoimmune symptoms were observed in mice when CCR8+ Tregs were depleted by anti-mouse CCR8 antibody administration (7). These results suggest that S-531011 may have a lower risk of inducing autoimmune diseases when administered to humans. It has been reported that the combination immunotherapy increases the risk of developing immune-related adverse events (29). In the hCCR8 KI mouse model, S-531011 alone or combined with PD-1 showed potent drug efficacy (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S5C), no adverse effects, such as body weight reduction over 10%, lethality, and general condition abnormalities, were observed (Fig. 3D). Our in vivo data suggest that S-531011 is safe combined with other immunotherapies.

In conclusion, this study suggests that S-531011 exerts a potent therapeutic effect without severe side effects. Phase Ib/II clinical trials of S-531011 as monotherapy and combined with anti–PD-1 antibody in advanced or metastatic solid tumors are ongoing and S-531011 is highly expected to be safe and therapeutic in humans.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

The binding activity of S-531011 against various chemokine receptors, PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA4, or mouse CCR8

Generation of humanized CCR8 KI mice

Concentration of S-531011 in serum and tumor after a single intravenous administration of S-531011 in CT26.WT tumor-bearing hCCR8 KI mice.

Binding profile of the newly created CCR8 antibody

In vivo anti-tumor activity of S-531011 in CT26.WT or EMT6 tumor-bearing mice model.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Shionogi & Co., Ltd. The authors would like to thank Keiji Dohi, Fumiyo Takahashi, and Reimi Matsumoto for performing in vitro analysis; Shinpei Yoshida for conducting the pharmacokinetics studies; Tetsuyoshi Soh for conducting safety studies; Yasuyuki Fusamae for generating the hCCR8 KI mouse model; Tatsuya Takahashi for the expert comments on this study; and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of publication fees. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Molecular Cancer Therapeutics Online (http://mct.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Disclosures

Y. Nagira reports personal fees and other support from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. outside the submitted work. M. Nagira reports personal fees from Shionogi Co. Ltd. and other support from Shionogi Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work; in addition, M. Nagira has a patent for WO2020138489 issued. R. Nagai reports personal fees and other support from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. outside the submitted work. W. Nogami reports personal fees from Shionogi outside the submitted work. M. Hirata reports personal fees from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work. A. Ueyama reports personal fees from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. outside the submitted work. T. Yoshida reports personal fees from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work; in addition, T. Yoshida has a patent for WO2018181425 issued and a patent for WO2020138489 issued. M. Yoshikawa reports personal fees from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. outside the submitted work; in addition, M. Yoshikawa has a patent for WO2020138489 issued. S. Shinonome reports personal fees and other support from Shionogi outside the submitted work; in addition, S. Shinonome has a patent for WO2018181425 issued. H. Yoshida reports personal fees and other support from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work. M. Haruna reports personal fees and other support from Shionogi Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work. H. Miwa reports personal fees and other support from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work. N. Chatani reports personal fees and other support from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work. N. Ohkura reports grants from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. during the conduct of the study; in addition, N. Ohkura has a patent for WO2018181425, WO2020138489 issued. H. Wada reports other support from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. during the conduct of the study; other support from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work; in addition, H. Wada has a patent for WO2018181425, WO2020138489 issued. H. Tanaka reports personal fees and other support from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work.

Authors' Contributions

Y. Nagira: Conceptualization, data curation, supervision, visualization, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing. M. Nagira: Conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing–review and editing. R. Nagai: Data curation, visualization, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. W. Nogami: Data curation, visualization, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. M. Hirata: Data curation, visualization, writing–review and editing. A. Ueyama: Data curation, visualization, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. T. Yoshida: Resources, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. M. Yoshikawa: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. S. Shinonome: Validation, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. H. Yoshida: Validation, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. M. Haruna: Validation, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. H. Miwa: Validation, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. N. Chatani: Validation, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. N. Ohkura: Resources, supervision, writing–review and editing. H. Wada: Resources, supervision, writing–review and editing. H. Tanaka: Conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Kefford R, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumour response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA 2016;315:1600–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, Creelan B, Horn L, Steins M, et al. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;376:2415–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jenkins RW, Barbie DA, Flaherty KT. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br J Cancer 2018;118:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim J, Lahl K, Hori S, Loddenkemper C, Chaudhry A, deRoos P, et al. Cutting edge: depletion of Foxp3+ cells leads to induction of autoimmunity by specific ablation of regulatory T cells in genetically targeted mice. J Immunol 2009;183:7631–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bennet CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet 2001;27:20–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wing JB, Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Human FOXP3 + regulatory T cell heterogeneity and function in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunity 2019;50:302–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kidani Y, Nogami W, Yasumizu Y, Kawashima A, Tanaka A, Sonoda Y, et al. CCR8-targeted specific depletion of clonally expanded Treg cells in tumor tissues evokes potent tumor immunity with long-lasting memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119:e2114282119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tiffany HL, Lautens LL, Gao JL, Pease J, Locati M, Combadiere C, et al. Identification of CCR8: a human monocyte and thymus receptor for the CC chemokine I-309. J Exp Med 1997;186:165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mikhak Z, Fukui M, Farsidjani A, Medoff BD, Tager AM, Luster AD. Contribution of CCR4 and CCR8 to antigen-specific T(H)2 cell trafficking in allergic pulmonary inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;123:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barsheshet Y, Wildbaum G, Levy E, Vitenshtein A, Akinseye C, Griggs J, et al. CCR8 + FOXp3 + T reg cells as master drivers of immune regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:6086–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Damme HV, Dombrecht B, Kiss M, Roose H, Allen E, Overmeire EV, et al. Therapeutic depletion of CCR8 + tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells elicits antitumor immunity and synergizes with anti-PD-1 therapy. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e001749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whiteside SK, Grant FM, Gyori DS, Conti AG, Imianowski CJ, Kuo P, et al. CCR8 marks highly suppressive Treg cells within tumours but is dispensable for their accumulation and suppressive function. Immunology 2021;163:512–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang T, Zhou Q, Zeng H, Zhang H, Liu Z, Shao J, et al. CCR8 blockade primes anti-tumor immunity through intratumoral regulatory T cells destabilization in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2020;69:1855–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Villarreal DO, LHuillier A, Armington S, Mottershead C, Filippova EV, Coder BD, et al. Targeting CCR8 induces protective antitumor immunity and enhances vaccine-induced responses in colon cancer. Cancer Res 2018;78:5340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Campbell JR, McDonald BR, Mesko PB, Siemers NO, Singh PB, Mark S, et al. Fc-optimized anti-CCR8 antibody depletes regulatory T cells in human tumor models. Cancer Res 2021;81:2983–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Plitas G, Konopacki C, Wu K, Bos PD, Morrow M, Putintseva EV, et al. Regulatory T cells exhibit distinct features in human breast cancer. Immunity 2016;45:1122–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yi G, Guo S, Liu W, Wange H, Liu R, Tsun A, et al. Identification and functional analysis of heterogeneous FOXP3+ Treg cell subpopulations in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci Bull 2018;63:972–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Galfre G, Howe SC, Milstein C, Butcher G, Howard JC. Antibodies to major histocompatibility antigens produced by hybrid cell lines. Nature 1977;266:550–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gillissen MA, Yasuda E, de Jong G, Levie SE, Go D, Spits H, et al. The modified FACS calcein AM retention assay: a high throughput flow cytometer-based method to measure cytotoxicity. J Immunol Methods 2016;434:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boyerinas B, Jochems C, Fantini M, Levie SE, Go D, Spits H, et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity activity of a novel anti-PD-L1 antibody avelumab (MSB0010718C) on human tumor cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2015;3:1148–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haruna M, Ueyama A, Yamamoto Y, Hirata M, Goto K, Yoshida H, et al. The impact of CCR8+ regulatory T cells on cytotoxic T cell function in human lung cancer. Sci Rep 2022;12:5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iellem A, Mariani M, Lang R, Recalde H, Panina-Bordignon P, Sinigaglia F, et al. Unique chemotactic response profile and specific expression of chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2001;194:847–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kurose K, Ohue Y, Wada H, Iida S, Ishida T, Kojima T, et al. Phase Ia study of FoxP3+ CD4 Treg depletion by infusion of a humanized anti-CCR4 antibody, KW-0761, in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:4327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maeda Y, Wada H, Sugiyama D, Saito T, Irie T, Itahashi K, et al. Depletion of central memory CD8 + T cells might impede the antitumor therapeutic effect of Mogamulizumab. Nat Commun 2021;12:7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kamada T, Togashi Y, Tay C, Ha D, Sasaki A, Nakamura Y, et al. PD-1 + regulatory T cells amplified by PD-1 blockade promote hyperprogression of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:9999–10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumagai S, Togashi Y, Kamada T, Sugiyama E, Nishinakamura H, Takeuchi Y, et al. The PD-1 expression balance between effector and regulatory T cells predicts the clinical efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapies. Nat Immunol 2020;21:1346–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tay C, Qian Y, Sakaguchi S. Hyper-progressive disease: the potential role and consequences of T-regulatory cells foiling anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020;13:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Suzuki Y, Saito M, Ishii T, Urakawa I, Matsumoto A, Masaki A, et al. Mogamulizumab treatment elicits autoantibodies attacking the skin in patients with adult T-Cell leukemia-lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:4388–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang B, Wu Q, Zhou YL, Guo X, Ge J, Fu J. Immune-related adverse events from combination immunotherapy in cancer patients: a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Immunopharmacol 2018;63:292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

The binding activity of S-531011 against various chemokine receptors, PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA4, or mouse CCR8

Generation of humanized CCR8 KI mice

Concentration of S-531011 in serum and tumor after a single intravenous administration of S-531011 in CT26.WT tumor-bearing hCCR8 KI mice.

Binding profile of the newly created CCR8 antibody

In vivo anti-tumor activity of S-531011 in CT26.WT or EMT6 tumor-bearing mice model.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

![Figure 1. In vitro biological profiles of S-531011. Representative histogram of binding of S-531011 to tumor-infiltrating CD45+CD3+CD4+Foxp3−CD25− cells (A) and CD45+CD3+CD4+Foxp3+CD25+ cells (B), and representative figures of ADCC (C), neutralization (D), and CDC (E). In C, data were expressed as corrected RFU (RFU in S-531011 – RFU in human IgG1 isotype control antibody). In D, the percentage RFU of effectivity was calculated using the following formula: % RFU = [1 − {S-531011 – Control (+)} / {Control (−) – Control (+)}] × 100. Control (−) represents the average RFU value in the absence of S-531011 and Control (+) represents the average RFU value in the presence of 4.4 μg/mL (maximum concentration) S-531011. In E, dead cell (%) was calculated as DAPI-positive cells/target cells × 100.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/64a6/10477828/382e77c141fe/1063fig1.jpg)

![Figure 3. In vivo antitumor activity of S-531011 in a CT26.WT or EMT6 tumor-bearing mouse model. CT26.WT cells (A, C, and D) or EMT6 cells (B) were subcutaneously implanted into the back of hCCR8 KI mice. A, S-531011 or 15 mg/kg isotype IgG1 antibody was administered intravenously on days 4 and 11. B, S-531011 or anti-mouse PD-1 antibody or vehicle was administered intravenously on days 5 and 12. C and D, S-531011 and/or anti-mouse PD-1 antibody or isotype IgG1 antibody was intravenously administered on day 5. Tumor volume (A–C) and body weight of mice (D) were measured. Tumor volume (cm3) was calculated using the following formula: [(Length × Width × Breadth) ÷ 2]. Each point and bar showed the mean and SE of tumor volume, respectively (A, n = 10; B, n = 10; C, n = 9). A: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 (vs. isotype IgG1 group on day 19; Dunnett multiple comparison test). B: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001 (vs. control group at 28 days after implantation, Dunnett multiple comparison test); #, P < 0.05 (vs. anti–PD-1 antibody-treated group at day 28, Mann–Whitney U test); C: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001 (vs. isotype IgG1-treated group at day 21, Dunnett multiple comparison test); #, P < 0.05 (vs. S-531011-treated group at day 21, Mann–Whitney U test). Tumor growth curves for each individual mouse in each group are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/64a6/10477828/4f8ea2a6f1a9/1063fig3.jpg)