Abstract

Objective:

To describe the national delivery of medication therapy management (MTM) to Medicare beneficiaries in 2013 and 2014.

Methods:

Descriptive cross-sectional study using the 100% sample of 2013 and 2014 Part D MTM data files. We quantified descriptive statistics (counts and percentages, in addition to means and standard deviations) to summarize the delivery of these services and compare delivery between 2013 and 2014.

Results:

Medicare beneficiaries eligible for MTM increased from 4,281,733 in 2013 to 4,552,547 in 2014. Among eligible beneficiaries, the number and percentage who were offered a comprehensive medication review (CMR) increased from 3,473,004 (81.1%) to 4,394,822 (96.5%), and beneficiaries receiving a CMR increased from 526,203 (12.3%) to 767,286 (16.9%). In 2014, CMRs were most frequently delivered by telephone (83.2%) and provided by either a plan sponsor (29.0%) or an MTM vendor in-house pharmacist (35.0%). In 2014, pharmacists provided 93.5% of all CMRs, and other providers (e.g., nurses and physicians) provided 6.5% of CMRs. Few patients who received a CMR received more than 1 within the same year (2.2% in 2014). Medication therapy problem (MTP) resolution among patients receiving a CMR stayed roughly the same between 2013 and 2014 (19.2% vs. 18.7%, respectively; P < 0.001). Finally, most beneficiaries (96.9% in 2014) received a targeted medication review, regardless of whether a CMR was offered or provided.

Conclusion:

More than 4 million Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in Part D MTM in both 2013 and 2014. However, less than 20% of eligible beneficiaries received a CMR during those years, and rates of MTP resolution were low. Future evaluation of Part D MTM delivery should examine changes in eligibility criteria and delivery over time to inform MTM policy and changes in practice.

Background

Drug-related morbidity and mortality due to nonoptimized medications cost the United States more than $500 billion annually.1 One strategy to address this significant and costly problem is the provision of medication therapy management (MTM). In 2003, MTM was officially recognized in the Medicare Modernization Act as a covered benefit for Medicare Part D beneficiaries.2 According to the Act, MTM programs must be designed to (1) optimize therapeutic outcomes through improved medication use and (2) reduce the risk of adverse events, including adverse drug events.3 The Medicare Part D program provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires that all plan sponsors provide MTM services to eligible beneficiaries enrolled in their plans. The specifications for eligibility change from year to year with the publication of an annual guidance document. Since 2010, the minimum criteria for eligibility has comprised enrollees having at least 2–3 chronic diseases, taking at least 2–8 medications, and likely to incur annual drug costs for Part D ranging from $3000 to $4044.3,4 However, these requirements are the minimum thresholds, and plans may offer MTM to expanded populations of beneficiaries.

The annual contract guidance provided by CMS highlights the minimum requirements that plans must meet when of-fering and providing MTM services. Any beneficiary that meets eligibility is required to be auto-enrolled into the MTM program, with an opportunity to opt out of the program. At a minimum, MTM programs must provide annual comprehensive medication reviews (CMRs) and quarterly targeted medication reviews (TMRs) to each enrolled beneficiary.3 CMS defines a CMR as “a systematic process of collecting patient-specific information, assessing medication therapies to identify medication-related problems, developing a prioritized list of medication-related problems, and creating a plan to resolve them with the patient, caregiver and/or prescriber.”3 TMRs, on the other hand, focus on specific or potential medication-related problems. In addition, CMRs must be interactive and occur in real-time, whereas TMRs may occur asynchronously (e.g., through fax or mail).

Since its inception, facets of MTM have been studied, including clinical and economic outcomes, across multiple settings.5–11 However, a 2014 systematic review of outpatient MTM found that MTM interventions differed considerably across studies, and therefore the authors determined that existing evidence was insufficient to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of MTM.12 Although numerous models and methods for delivering MTM exist,13–16 it remains unclear as to which models lead to better outcomes. Previously, CMS data have not been available to evaluate the scope and delivery of MTM on a national level. In 2013, CMS began collecting standardized data from Medicare Part D prescription drug plans offering MTM programs.17 In 2017, CMS made MTM data available to researchers for all Part D beneficiaries for 2013 and 2014. Certain characteristics of MTM programs are reported through CMS.18 However, a description of the national delivery of MTM is lacking. This type of analysis is needed to evaluate baseline performance of MTM and track its variability and impact over time as future models and delivery methods emerge.

Objective

The objective of this study was to describe the national delivery of MTM to Medicare beneficiaries for 2013 and 2014.

Methods

We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional study using the 100% sample of 2013 and 2014 Part D MTM data files, which represent the most recent years of data available at the time this study was conducted.17 These data are limited to MTM delivery under the Part D program. The files contain detailed information regarding enrollment in the MTM program, the delivery of CMRs and TMRs, dates of CMR offer, dates of CMR receipt, method of CMR delivery, and the type of provider delivering CMR services. In addition, a number of summary variables describing the delivery of MTM services are provided for each patient in the MTM file, including annual counts of medication therapy problems (MTPs) recommendations made to pre-scribers, MTPs resolved, and TMRs received. More detailed description of the Part D MTM files is available online.17

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 software.19 We computed counts and percentages, as well as means and standard deviations to summarize and compare characteristics of Medicare Part D MTM delivery in 2013 and 2014. First, we investigated the number of MTM-eligible patients who were offered a CMR. Next, we examined the delivery of CMRs among those who were offered CMRs. According to Medicare Part D,20 the categories for method of delivery for CMR are face-to-face, telephonic, telehealth, or other. Although no specific definition of telehealth is provided, the requirements list video-conference as an example.

For each of the different cohorts (those not offered a CMR, those offered a CMR but not receiving a CMR, and those receiving a CMR) we further characterized the proportion of each cohort receiving any TMRs. This description of MTM service delivery allowed us to capture variation in the intensity of services provided to different beneficiaries.

This study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Results

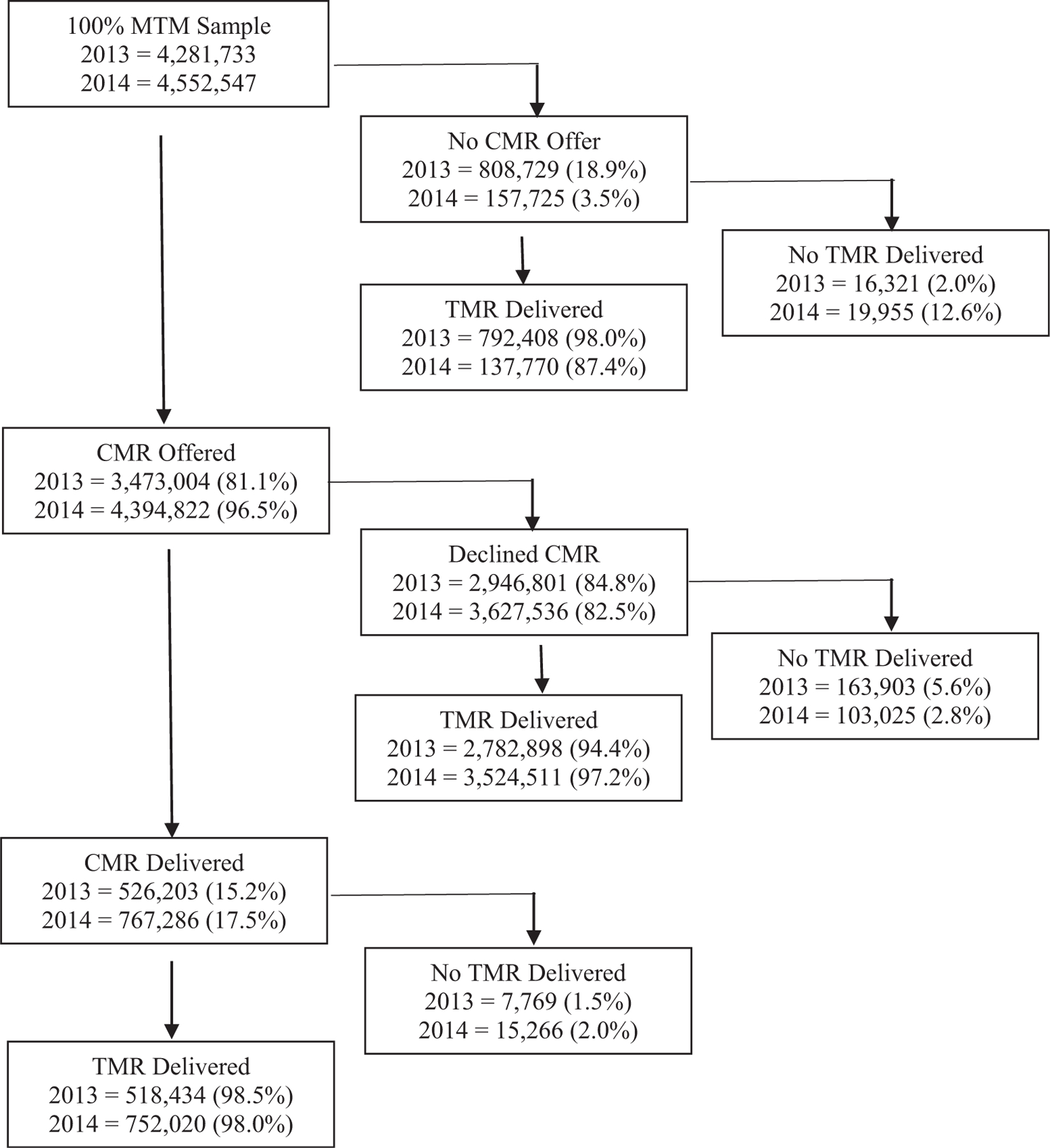

The number of Medicare beneficiaries eligible for MTM increased from 4,281,733 in 2013 to 4,552,547 in 2014 (Figure 1). Among eligible beneficiaries, the number and percentage of those who were offered a CMR increased from 3,473,004 (81.1%) to 4,394,822 (96.5%). The number and percentage of beneficiaries receiving a CMR also increased from 526,203 (12.3%) to 767,286 (16.9%) (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Of the patients who received a CMR, very few had a documented date of CMR follow-up (1.2% in 2013 vs. 2.2% in 2014; P < 0.001). The most common reasons for declining a CMR offer were plan disenrollment (45.8% in 2013 and 35.3% in 2014; P < 0.001) or death (32.9% in 2013 and 39.1% in 2014; P < 0.001). Regardless of whether a CMR was offered and whether the CMR offer led to the delivery of a CMR, the proportion of patients receiving a TMR was high across all cohorts. For example, among the 2,946,801 patients in 2013 and 3,627,536 patients in 2014 who were offered but who declined a CMR, 94.4% and 97.2% of these patients still received a TMR within that year, respectively.

Figure 1.

Medication therapy management delivery. Abbreviations used: CMR, comprehensive medication review; MTM, medication therapy management; TMR, targeted medication review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of MTM delivery

| Characteristic | Plan year |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 N (%) | 2014 N (%) | ||

| Description of MTM among MTM-eligible patients | 4,281,733 | 4,552,547 | − |

| Medication therapy problems (MTPs) | |||

| Number of patients with MTP recommendations | 1,292,753 (30.2%) | 1,478,959 (32.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Number of patients with MTP recommendation and resolution | 387,963 (30.0%) | 511,156 (34.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Total count of MTP recommendations made/ya | 4,344,480 | 5,184,155 | NA |

| Total count of MTP resolutions/y | 749,139 | 759,223 | NA |

| Description of patients opting out of MTM | 455,003 (10.6%) | 535,041 (11.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Beneficiary opt out assigned because of deathb | 149,571 (32.9%) | 209,057 (39.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Beneficiary opt out assigned because of disenrollmentb | 208,544 (45.8%) | 188,795 (35.3%) | |

| Beneficiary requested to opt outb | 93,320 (20.5%) | 134,344 (25.1%) | |

| Other reason for opting outb | 3568 (0.8%) | 2845 (0.5%) | |

| Description of MTM among CMR Recipients | 526,203 (12.3%) | 767,286 (16.9%) | < 0.001 |

| CMR recipients with only 1 + CMR encounterc | 520,138 (98.9%) | 750,528 (97.8%) | < 0.001 |

| CMR recipients with a recorded follow-up datec | 6065 (1.2%) | 16,758 (2.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) no of d to CMR follow-upc | 104 (74) | 115 (66) | < 0.001 |

| CMR recipients with 1þ MTP recommendationc | 267,721 (50.9%) | 390,471 (50.9%) | 0.8933 |

| CMR recipients with MTP recommendation & resolutionc | 101,100 (19.2%) | 143,230 (18.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Method of CMR delivery | |||

| Face-to-facec | 75,638 (14.4%) | 128,123 (16.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Telephonicc | 449,904 (85.5%) | 638,477 (83.2%) | |

| Telehealthc | 329 (0.1%) | 9 (0.0%) | |

| Otherc | 332 (0.1%) | 677 (0.1%) | |

| Type of CMR provider | |||

| CMR provided by a pharmacistc | 506,981 (96.3%) | 717,198 (93.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Community pharmacistc,d | 112,252 (21.3%) | 177,513 (23.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Plan pharmacistc,e | 211,326 (40.2%) | 222,291 (29.0%) | |

| MTM vendor in-house pharmacistc | 134,712 (25.6%) | 268,199 (35.0%) | |

| Other pharmacistsc,f | 48,691 (9.3%) | 49,195 (6.4%) | |

| CMR provided by “Other” provider typesc,g | 19,222 (3.7%) | 50,088 (6.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Recipient of CMR service | |||

| Beneficiaryc | 472,124 (89.7%) | 677,711 (88.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Beneficiary prescriberc | 685 (0.1%) | 1121 (0.2%) | |

| Caregiverc | 34,414 (6.5%) | 64,075 (8.4%) | |

| Other authorized individualc | 18,980 (3.6%) | 24,379 (3.2%) | |

Abbreviations used: CMR, comprehensive medication review; MTM, medication therapy management; MTP, medication therapy problems; N/A, not applicable.

Patients with an MTP could have more than one MTP per year.

Denominator represents patients opting out of MTM, which was 455,003 and 535,041 for 2013 and 2014, respectively.

Denominator represents CMR recipients, which was 526,203 and 767,286 for 2013 and 2014, respectively.

Community pharmacist = Local pharmacist and MTM vendor local pharmacist.

Plan pharmacist = Plan sponsor pharmacist and pharmacist benefit manager pharmacist.

Other pharmacist = Long term care, hospital, and other unspecified pharmacist.

Other provider types = Nurse, physician assistant, physician, or “other unspecified” providers.

Across all patients in the MTM program, 4,344,480 MTP recommendations were made to prescribers in 2013, and 5,184,155 recommendations were made in 2014. This resulted in 749,139 and 759,223 MTP resolutions in 2013 and 2014, respectively. Almost one-third of MTM-eligible beneficiaries had at least 1 MTP recommendation (1,292,753 [30.2%] in 2013 and 1,478,959 [32.5%] in 2014; P < 0.001). Out of all of the patients with an MTP recommendation, 387,963 (30.0%) and 511,156 (34.6%) (P < 0.001) also had an MTP resolution recorded in 2013 and 2014, respectively.

MTP recommendations and resolutions were more common in patients receiving CMRs. Out of the 526,203 patients receiving a CMR in 2013, 267,721 (50.9%) had at least 1 MTP recommendation, and of those, 101,100 (37.8%) had at least 1 MTP resolution. These rates remained similar in 2014. Out of CMR recipients in that year, 390,471 (50.9%) had at least 1 MTP recommendation, and 143,230 (36.7%) had an MTP resolution.

Across both years, CMRs were most frequently delivered over the phone (85.5% and 83.2% for 2013 and 2014, respectively; P < 0.001) and were provided by either a plan pharmacist, defined as either a plan sponsor or pharmacy benefit manager pharmacist, (40.2% and 29.0%; P < 0.001) or an MTM vendor in-house pharmacist (25.6% and 35.0%; P < 0.001). Community pharmacists (defined as local or MTM vendor local pharmacists) provided 21.3% and 23.1% (P < 0.001) of CMRs in 2013 and 2014, respectively. The number of nonpharmacist providers of MTM (e.g., nurses, physician assistants, and physicians) increased from 19,222 (3.7%) to 50,088 (6.5%) (P < 0.001) between 2013 and 2014.

Discussion

More than 4 million Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in Part D MTM in 2013 and 2014, resulting in a total count of more than 9 million MTP recommendations and 1.5 million MTP resolutions across both years. Although this is a critical step toward optimizing medications and improving health outcomes, several important areas of opportunity exist. For example, only 12.3% and 16.9% of MTM-eligible patients received a CMR in 2013 and 2014, respectively. The increase in CMR delivery in 2014 could be explained by the addition of CMR completion rate as a Part D plan display measure that year. Since then, CMR completion rates have continued to rise,21 which may be attributed to the adoption of CMR completion as a Star Ratings measure in 2016.22 However, in 2013 and 2014, only a small percent of beneficiaries eligible for a CMR received one.

Although most patients in each year were offered a CMR, 84.8% in 2013 and 82.5% in 2014 declined. In addition, among those patients who declined a CMR, 94.4% and 97.2% received a TMR in 2013 and 2014, respectively. TMR delivery rates were also high among those who received a CMR, with 98.5% and 98.0% receiving a TMR in 2013 and 2014, respectively. This is due likely to TMRs being easier to complete because, unlike a CMR, they do not need to occur person-to-person. In addition, TMRs should occur at least quarterly, which may also explain why more patients received a TMR. Although TMRs have demonstrated benefits in reducing health care utilization and improving adherence,23 the comprehensive nature of CMRs make them a key component of MTM services. Therefore, attention should be paid to improving strategies to increase the acceptance of CMR offers among beneficiaries. Although plan disenrollment and death were contributors to the patients’ declining CMRs, a number of studies have sought to evaluate strategies to engage more patients in CMRs, such as outreach models, pharmacy technician engagement, and others.24–26 Research should continue in this area to investigate further and implement methods to improve acceptance of CMR offers.

Of patients who received MTM, about one-third had at least 1 MTP recommendation made to a prescriber in 2013 and in 2014. Given the inclusion criteria for MTM program, it is surprising that more patients did not have an MTP recommendation. Other studies, although not necessarily specific to Medicare patients, have reported much higher rates of MTPs identified after a pharmacist’s assessment.27–29 There may be several factors contributing to this lower rate. For example, nonadherence is a frequently identified MTP,30 but it often does not require a recommendation to the prescriber to resolve. In addition, MTPs related to over-the-counter products, including vitamins and supplements, are not likely to result in a prescriber recommendation. Similarly, it is possible that patients in this dataset had MTPs that were identified and resolved in previous years of the program, or there may be a lack of documentation around MTP recommendations. It is also possible that the inclusion criteria put forth by CMS and adopted by plans are not effectively identifying patients with MTPs.

Only 30% of patients with an MTP recommendation also had an MTP resolution in 2013, and 34.6% had an MTP resolution in 2014. This may suggest that patients and health care providers are not accepting the majority of recommendations made through the MTM program. However, this may also be reflective of MTM setting and delivery model. For example, pharmacists working under a collaborative practice agreement with the authority to adjust dosing or initiate or discontinue medications may see higher rates of MTP resolution. Similarly, pharmacists with strong collaborative relationships with prescribers in their community may experience higher acceptance rates of MTP recommendations. Further research is needed to determine factors affecting MTP resolution and strategies to increase acceptance of MTP recommendations.

A large programmatic change that is currently being studied is the enhanced medication therapy management (EMTM) model, which began in 2017 as a 5-year CMS Innovations initiative.31 Previous work has called out the enrollment variation that leads to inequities in access to MTM across plans.32 The EMTM program, however, allows Part D drug plans to implement innovative methods to target eligible patients and deliver MTM services. Plans are encouraged under the program to rethink their method of targeting patients to enroll beneficiaries with high medication-related risk and tailor the specific intervention being delivered to these patients to improve health outcomes. As part of this program, plans could offer innovative prospective payment models, engage in performance-based payment initiatives, request Part A and B claims data to assist with care coordination and payment innovations, and implement innovative documentation and data collection efforts to support the delivery of services. As the most significant innovation to the MTM program since its inception, changes in the delivery of MTM services resulting from the EMTM program should be monitored in future years to better understand the influence of this program on the enrollment and uptake of MTM services.

The MTM program has seen numerous changes since it began in 2006. Over the years, eligibility criteria have evolved, the reach of the program has expanded as quality measures have focused on CMRs, and innovative care models and delivery methods continue to be explored. This work provides a national description of the MTM program for 2013 and 2014. As highlighted above, there are still many research questions that warrant investigation. Therefore, these results may serve as a useful baseline to assess performance, as research continues in this area and as policy and payment structures affecting medication use and MTM are adopted.

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study and is unable to infer causality between any relationships. Given that we limited the analysis to the 100% MTM delivery files, we do not describe the delivery of the service across different populations. Future research tying these data to patient enrollment and health service utilization information is underway to better understand the delivery of this service among different patient groups. A limitation of the data is that it only includes MTP recommendations and not the number of MTPs identified. It also does not include the type of MTP (e.g., unnecessary medication therapy, dosage too low).33 It should also be mentioned that the lack of information on continuous enrollment in the health plans means that beneficiaries enrolled for a part of the year are included. Had these data been standardized to require continuous enrollment in each year, the rates of MTP identification, CMR offer, and CMR receipt might differ. Our results are not likely to be generalizable to more recent years of MTM. Changes to the MTM program and related annual guidance documents will result in changes to the delivery of MTM services and should be monitored over time as future years of MTM data become available.

Conclusion

Under the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit, more than 4 million beneficiaries were enrolled into MTM on an annual basis. As a result, more than 1.5 million MTPs were identified and resolved between 2013 and 2014, which is critical to optimizing medications and improving health outcomes. Our results indicate that there are low rates of delivery of CMRs across eligible beneficiaries. In addition, the majority of patients with an MTP recommendation do not have record of an MTP resolution. These results suggest opportunities to improve the delivery of MTM services under Medicare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Eric Berger, MS, for programming the tables and data to support this project.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Antoinette B. Coe is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number KL2TR002241. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Karen B. Farris reports consulting with QuiO, outside the submitted work. Omolola A. Adeoye is supported by the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute funded, in part by Award Number TL1TR001107 (A. Shekhar, PI) from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. Margie E. Snyder reports grants and personal fees from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and personal fees from Westat, Inc., outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no other relevant conflicts of interest or financial relationships.

Previous presentation: American Pharmacists Association (APhA) 2019 Annual Meeting.

Contributor Information

Deborah L. Pestka, College of Pharmacy, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Alan J. Zillich, Purdue College of Pharmacy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN.

Antoinette B. Coe, College of Pharmacy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Karen B. Farris, College of Pharmacy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Omolola A. Adeoye, Purdue College of Pharmacy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN.

Margie E. Snyder, Purdue College of Pharmacy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN.

Joel F. Farley, College of Pharmacy, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

References

- 1.Watanabe JH, McInnis T, Hirsch JD. Cost of prescription drug-related morbidity and mortality. Ann Pharmacother 2018;52(9):829e837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 Available at: https://www.congress.gov/108/plaws/publ173/PLAW108publ173.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2019.

- 3.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CY 2019 medication therapy management program guidance and submission instructions Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Memo-Contract-Year-2019-Medication-Therapy-Management-MTM-Program-Submission-v-04 0618.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2019.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2011 Medicare Part D medication therapy management (MTM) programs Available at: https://wwwcms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/downloads/MTMFactSheet2011063011Final.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2019.

- 5.Stockl KM, Tjioe D, Gong S, Stroup J, Harada AS, Lew HC. Effect of an intervention to increase statin use in Medicare members who qualified for a medication therapy management program. J Manag Care Pharm 2008;14(6):532e540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox D, Ried LD, Klein GE, Myers W, Foli K. A medication therapy management program’s impact on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in Medicare Part D patients with diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2009;49(2):192e199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welch EK, Delate T, Chester EA, Stubbings T. Assessment of the impact of medication therapy management delivered to home-based Medicare beneficiaries. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43(4):603e610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward MA, Xu Y. Pharmacist-provided telephonic medication therapy management in an MAPD plan. Am J Manag Care 2011;17(10): e399ee409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Touchette DR, Masica AL, Dolor RJ, et al. Safety-focused medication therapy management: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2012;52(5):603e612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branham AR, Katz AJ, Moose JS, Ferreri SP, Farley JF, Marciniak MW. Retrospective analysis of estimated cost avoidance following pharmacist-provided medication therapy management services. J Pharm Pract 2013;26(4):420e427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moczygemba LR, Barner JC, Gabrillo ER. Outcomes of a Medicare Part D telephone medication therapy management program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2012;52(6):e144ee152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viswanathan M, Kahwati LC, Golin CE, et al. Medication therapy management interventions in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(1):76e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. The patient-centered medical home: integrating comprehensive medication management to optimize patient outcomes Available at: https://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/media/medmanagement.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2019.

- 14.Joint Commision of Pharmacy Practitioners. The pharmacists’ patient care process Available at: https://jcpp.net/patient-care-process/. Accessed March 18, 2019.

- 15.Roth MT, Ivey JL, Esserman DA, Crisp G, Kurz J, Weinberger M. Individualized medication assessment and planning: optimizing medication use in older adults in the primary care setting. Pharmacotherapy 2013;33(8): 787e797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snyder ME, Jaynes HA, Gernant SA, Lantaff WM, Hudmon KS, Doucette WR. Variation in medication therapy management delivery: implications for health care policy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2018;24(9): 896e902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Research Data Assistance Center. Part D medication therapy management data file Availabe at: https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/part-d-mtm-data-file/datadocumentation. Accessed March 18, 2019.

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medication therapy management Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/prescription-drug-coverage/prescriptiondrugcovcontra/mtm.html. Accessed March 19, 2019.

- 19.SAS [computer program]. Version 9.4 Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Center for Medicare, Medicare Drug Benefit and C&D Data Group. Medicare Part D plan reporting requirements: technical specifications document contract year 2014 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/CY2014-Technical-Specifications_102014-v2.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2019.

- 21.Pharmacy Quality Solutions. Medicare 2019 star rating threshold update Available at: https://www.pharmacyquality.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2019StarRatingThreshold4.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2019.

- 22.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare 2016 Part C & D star rating technical notes: first plan review Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/Downloads/2016-Technical-Notes-Preview-1-v2015_08_05.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2019.

- 23.Ferries E, Dye JT, Hall B, Ndehi L, Schwab P, Vaccaro J. Comparison of medication therapy management services and their effects on health care utilization and medication adherence. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2019;25(6):688e695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adeoye OA, Lake LM, Lourens SG, Morris RE, Snyder ME. What predicts medication therapy management completion rates? The role of community pharmacy staff characteristics and beliefs about medication therapy management. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2018;58(4S):S7eS15.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller DE, Roane TE, Salo JA, Hardin HC. Evaluation of comprehensive medication review completion rates using 3 patient outreach models. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2016;22(7):796e800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stafford R, Thomas J, Payakachat N, et al. Using an array of implementation strategies to improve success rates of pharmacist-initiated medication therapy management services in community pharmacies. Res Social Adm Pharm 2017;13(5):938e946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akers JL, Meer G, Kintner J, Shields A, Dillon-Sumner L, Bacci JL. Implementing a pharmacist-led in-home medication coaching service via community-based partnerships. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2019;59(2): 243e251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Lint JA, Sorge LA, Sorensen TD. Access to patients’ health records for drug therapy problem determination by pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2015;55(3):278e281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan WWT, Dahri K, Partovi N, Egan G, Yousefi V. Evaluation of collaborative medication reviews for high-risk older adults. Can J Hosp Pharm 2018;71(6):356e363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorensen TD, Pestka DL, Brummel AR, Rehrauer DJ, Ekstrand MJ. Seeing the forest through the trees: improving adherence alone will not optimize medication use. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2016;22(5):598e604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Part D enhanced medication therapy management model Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/enhancedmtm/. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 32.Stuart B, Hendrick FB, Shen X, et al. Eligibility for and enrollment in Medicare Part D medication therapy management programs varies by plan sponsor. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(9):1572e1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. PQA medication therapy problem categories framework Available at: https://www.pqaalliance.org/assets/Measures/PQAMTP Categories Framework.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2019.