Abstract

Background

Loneliness and social isolation are increasingly recognised as prevalent among people with mental health problems, and as potential targets for interventions to improve quality of life and outcomes, as well as for preventive strategies. Understanding the relationship between quality and quantity of social relationships and a range of mental health conditions is a helpful step towards development of such interventions.

Purpose

Our aim was to give an overview of associations between constructs related to social relationships (including loneliness and social isolation) and diagnosed mental conditions and mental health symptoms, as reported in systematic reviews of observational studies.

Methods

For this umbrella review (systematic review of systematic reviews) we searched five databases (PsycINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science) and relevant online resources (PROSPERO, Campbell Collaboration, Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Synthesis Journal). We included systematic reviews of studies of associations between constructs related to social relationships and mental health diagnoses or psychiatric symptom severity, in clinical or general population samples. We also included reviews of general population studies investigating the relationship between loneliness and risk of onset of mental health problems.

Results

We identified 53 relevant systematic reviews, including them in a narrative synthesis. We found evidence regarding associations between (i) loneliness, social isolation, social support, social network size and composition, and individual-level social capital and (ii) diagnoses of mental health conditions and severity of various mental health symptoms. Depression (including post-natal) and psychosis were most often reported on, with few systematic reviews on eating disorders or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and only four related to anxiety. Social support was the most commonly included social construct. Our findings were limited by low quality of reviews and their inclusion of mainly cross-sectional evidence.

Conclusion

Good quality evidence is needed on a wider range of social constructs, on conditions other than depression, and on longitudinal relationships between social constructs and mental health symptoms and conditions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-023-05069-0.

Keywords: Loneliness, Social isolation, Social network, Mental Health, Umbrella review

Introduction

Evidence is accumulating on the effects of social relationships, or of the lack of them, on physical and mental health. Loneliness and social isolation have been associated with increased mortality rates in two meta-analytic reviews, with comparable effect sizes to those observed for smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity as risk behaviors [1, 2]. Loneliness and social isolation are longitudinally associated with the development of cardiovascular disease [3], elevated blood pressure [4, 5], and increased fatigue and pain [6]. Among people with mental health problems, loneliness and social isolation are more prevalent than in the general population [7, 8]. Associations with loneliness and social isolation have been reported for depressive disorders [9, 10] and symptoms [11], self-harm [12], psychosis [13, 14], being diagnosed with a “personality disorder” [15], cognitive decline [16, 17], mild cognitive impairment, and dementia [18]. In a rapidly expanding research field, an up-to-date synthesis is needed of evidence on whether, and in what ways, loneliness, social isolation, and related constructs are associated with the incidence and prevalence of a range of mental health conditions, and with their outcomes.

Several other social constructs are related to loneliness and social isolation, including social support, social networks, individual social capital, confiding relationships, connectedness and alienation. Wang et al. [19] have proposed a conceptual model to incorporate these constructs related to social relationships at the individual level in mental health research. According to this model, these constructs can be grouped as: (i) perceived or subjective experiences of social relationships (such as loneliness, perceived social isolation, social support, confiding relationships or individual-level social capital); (ii) objective aspects of social isolation (such as the number of social contacts and social network size), or (iii) constructs that combine measures of both quality and quantity of social relationships (such as social support from members of an individual’s social network).

Several systematic reviews have been published regarding associations between constructs related to social relationships and aspects of mental health, e.g. [10, 20–23]. However, these reviews have typically focused on specific mental health outcomes in particular populations, so that they do not provide a holistic stock-take of the overall state of evidence in this field, its implications for research, policy and practice, and the gaps still to be addressed.

Umbrella reviews, which are systematic reviews of the systematic review evidence [24], can inform policy, practice and further research by providing a systematic overview of current evidence and its gaps. One recent umbrella review explored the associations between loneliness and outcome measures related to mental health [25]. This concluded that loneliness has a range of adverse impacts on mental and physical health outcomes, but it did not include other related constructs such as social isolation, or reviews of associations between loneliness and social isolation and mental health diagnoses. To our knowledge, there is no umbrella review that synthesises the evidence for associations between a comprehensive set of constructs related to social relationships and specific mental health problems. Such a review has potential value in allowing policy makers, clinicians and researchers to identify areas in which there is a robust and actionable body of evidence regarding connections between mental health conditions and social relationships, and those in which there is a pressing need for more evidence.

This umbrella review addresses this gap by providing an updated and comprehensive overview of the evidence on the associations between a full range of social constructs at the individual level (Table 1) and mental health diagnoses and symptoms in both clinical and population-based samples. The constructs we used to encapsulate important aspects of social relationships including loneliness and isolation are those identified by Wang et al. [19] in their conceptual review. We aimed to address the following linked research questions:

Table 1.

Definitions of constructs related to social relations

| Construct | Description | Reference (all reviewed in Wang et al., 2017 [19]) |

|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | A painful subjective emotional state occurring when there is a discrepancy between desired and achieved patterns of social interaction. | Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2009; Peplau & Perlman, 1982 |

| Social isolation | Inadequate quality and quantity of social relations with other people at the individual, group, community, and larger social environment levels where human interaction takes place. | Zavaleta, Samuel & Mills, 2014 |

| Social support |

Structural social support: the existence, quantity, and properties of an individual’s social relations; it focuses on the study of structural aspects of social contacts, such as the characteristics of the support network. Functional social support: the functions fulfilled by social relations, such as emotional support which involves caring, love and empathy; instrumental support (referred to by many as tangible support); informational support which consists of information, guidance or feedback that can provide a solution to a problem; appraisal support which involves information relevant to self-evaluation and social companionship, which involves spending time with others in leisure and recreational activities. |

Cohen & Hoberman, 1983; House 1981; Moreno, 2004; Wills, 1985 |

| Social network |

A specific set of linkages among a defined set of persons, with the additional property that the characteristics of these linkages as a whole may be used to interpret the social behaviour of the persons involved: Size: the number of people with whom the respondent has had social contact e.g. in the last month; Frequency of contact: the number of people with whom the respondent has had social contact e.g. daily; weekly; or monthly over the past month; Density: the proportion of all possible ties between network members which are present (i.e., how many of a respondent’s network know each other); Proportion of kin/non-kin in social network: How many of the total number of people within a respondent’s social network are relatives?; Intensity: whether relationships are “uniplex” (one function only) or “multiplex” (more than one function); Directionality: who is helping whom in a dyadic relationship. |

Cohen & Sokolovsky, 1978; Mitchell, 1969 |

| Individual social capital |

A series of resources that individuals earn as a result of their membership in social networks, and the features of those networks that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit; can be understood as the property of an individual. Most commonly measured by asking individuals about their participation in social relationships (such as membership of groups) and their perceptions of the quality of those relationships. |

De Silva, McKenzie, Harpham & Huttly, 2005; McKenzie, Whitley & Weich, 2002; Portes, 1998; Putnam, 2000 |

| Confiding relationships | The number of people with whom the respondent reports they can talk about worries or feelings. | Brown & Harris, 1978; Murphy, 1982 |

What is the evidence from systematic reviews regarding associations in general population samples between constructs related to social relationships, and presence of mental health conditions and symptoms?

What evidence is there from systematic reviews regarding associations between constructs related to social relationships and severity of psychiatric symptoms among people diagnosed with mental health conditions?

What evidence is there from systematic reviews of longitudinal relationships between constructs related to social relationships and risk of onset of mental health conditions in the general population?

Methods

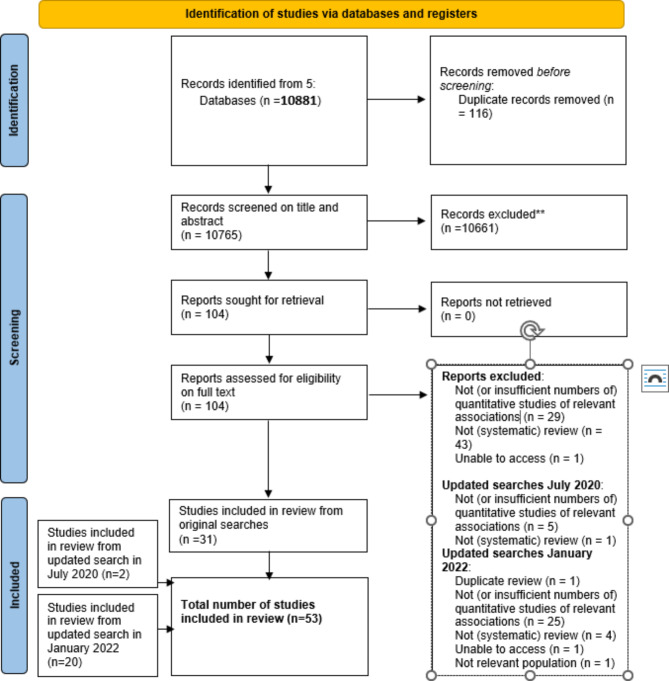

We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Fig. 1). The protocol for this review was pre-registered with the international Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews.

Fig. 1.

Prisma diagram identification of studies via databases and registers

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Boosuvt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. Doi:1136/bmj.n71For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

(PROSPERO: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020192509).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included exposures: measures related to social relationships

We included the subjective aspects of social relationships and objective measures of social network size and structure identified in the conceptual review by Wang et al. [19] to encapsulate the main dimensions of social relationships assessed in mental health research. Table 1 summarises and defines the included domains of measurement. We excluded dimensions of social relationships beyond the individual level, such as ecological social capital or social exclusion, following Wang et al. [19].

Included outcomes: mental health measures

We considered a full range of mental health diagnoses and psychiatric symptoms, but we excluded neurodegenerative diagnoses (e.g., dementia), neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., intellectual disabilities), general wellbeing outcomes and suicide-related outcomes, as well as cohorts of people selected on the basis of a primary physical health diagnosis.

Included methods

We included reviews of quantitative studies (cross-sectional and longitudinal) of associations between constructs related to social relationships (exposures; see above) and mental health diagnoses or psychiatric symptom severity (outcomes) in clinical and general population samples. We included meta-analyses, narrative systematic reviews and any other literature reviews that followed systematic methods. Included reviews varied in whether they reported adjusted and/or unadjusted associations. We excluded individual empirical studies and reviews that were not systematic. We did not apply any restrictions by publication date, language or age to our search.

Search strategy

We searched PsycINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases. We also searched online repositories of systematic reviews: PROSPERO, Campbell Collaboration, and the Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Synthesis Journal.

The following search terms related to social isolation and loneliness were used following the conceptual review by Wang et al. [19]: social isolation OR loneliness OR social network* OR social support OR confiding OR confide OR social contact* OR social relation* OR social capital.

The above terms were combined with the following search terms for mental health problems and symptoms:

(mental OR psychiatr* OR schizo* OR psychosis OR psychotic OR depress* OR mania* OR manic OR bipolar near/5 (disorder or disease or illness) OR anxiety) OR (Eating Disorder* OR Anorexia Nervosa OR Bulimia Nervosa OR Binge Eating Disorder) OR personality disorder* OR borderline personality OR emotionally unstable personality OR histrionic personality or narcissistic personality OR antisocial personality OR paranoid personality OR schizoid personality OR schizotypal personality OR avoidant personality OR dependent personality OR obsessive compulsive personality).

The search strategy for Medline appears in full in Supplementary Table S1; this was adapted to other search engines. The results of all searches were imported into EndNote. The initial search was run in August 2019 with updates in July 2020 and January 2022. Following removal of duplicate citations, a reviewer (MB or YN) screened the abstracts and titles of all articles against the inclusion criteria, and second reviewers (EP, MT) randomly screened 10% of included abstracts to check agreement. MB, EP, YN and MT screened the full texts of selected articles, with all full texts screened by a second reviewer. AP and EP discussed any disagreements and clarified criteria to achieve good consistency. Data were extracted from included reviews independently by nine reviewers (MB, EP, JY, EC, AS, LKC and MC, YN and MT): senior researchers MB and EP supervised the other reviewers to ensure consistency and checked extracted data.

For included studies, we developed and piloted a pro forma that allowed extraction of data on setting(s), objectives of the review, type of review, inclusion criteria, number of included studies, publication date range for included studies, type of analysis, and outcomes reported relating to mental health and to loneliness, social isolation and related constructs.

Quality assessment

Seven reviewers (JY, EC, AS, LKC, MC, MT and YN) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies under the supervision of MB and EP, using a modified version of AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) (Supplementary Table S2). One reviewer (MT) independently quality rated all included reviews to ensure consistency, and two further reviewers (YD, MH) then checked these again. The AMSTAR-2 tool has 16 items in total and enables appraisal of systematic reviews. Item 7, which assesses adequacy of explanations for excluding studies from reviews at the full text stage was modified (reviews were rated as a “no” but not as critically flawed if they included some explanations for exclusion but not a full list, and as critically flawed if no explanation was given) and Items 3, 10 and 16 (on interventions, funding and conflict of interest) were excluded because of limited relevance or feasibility. We included rapid systematic reviews and scoping reviews if the searches and data extraction were systematic.

Data synthesis

We conducted a narrative synthesis: we grouped reviews according to disorder or symptom type, and within these categories we separated them by different social constructs. Social constructs were grouped following Wang et al’s typology. Reviews may appear in more than one section of the narrative synthesis if they included multiple social constructs e.g. both loneliness and social support. Most reviews focused on broad groups of mental health conditions, such as depressive illnesses, conditions related to anxiety, perinatal conditions and psychosis: we were able to categorise the reviews straightforwardly by grouping together those reporting that they focused on the same, or similar mental health conditions. In our narrative, we distinguish reviews that report results from meta-analysis, and those that are longitudinal rather than reporting on cross-sectional associations. Where possible, we distinguished evidence on symptom severity versus diagnosis.

Results

In total, 53 systematic reviews were included in the final umbrella review (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 1), which together included 1,657 studies, of which 340 (21%) were longitudinal (Supplementary Table S3, showing study methodologies). Supplementary Table S4 provides details of the 147 studies that were included in more than one review: thus fewer than 10% of primary studies were included in more than one review. Of the 53 included reviews, 31 used narrative synthesis, 17 included meta-analyses, and five conducted both meta-analysis and narrative synthesis. Locations of studies included within the systematic reviews encompassed Europe, Asia, Africa, North and Central America and Australasia, although there were very few studies from lower income countries. Reviews were published between 2005 and 2021, with only three published prior to 2013. No deviations from the PROSPERO protocol were identified.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author & year | Type of review | Geographical setting of included studies | No. of relevant primary studies | Population | Year of included studies | Type of analysis | Exposure | Outcome | Quality rating/ overall confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression – loneliness | |||||||||

| Cohen-Mansfield et al., (2016) | Systematic Review | Finland, USA, Netherlands, Spain, Ireland, UK | 12 | Older Adults | 2004–2012 | Narrative Synthesis | Loneliness | ‘Depression’ including studies measuring depressive symptoms, low mood, ‘uselessness’, ‘lack of taking initiative’, and ‘expecting negative reactions from caregivers’ | Critically low |

| Erzen & Çikrikci (2018) | Systematic Review | Not reported | 70a | Adults | 1980–2018 | Meta-analysis | Loneliness | Depression (general term “depression”) | Critically low |

| Depression – loneliness, social isolation, social support and social network size | |||||||||

| Choi et al., (2015) | Systematic Review | Malaysia, USA, New Zealand, Turkey, Mexico | 8 | Older Adults | 2003–2014 | Narrative Synthesis | Subjective and objective social isolation | Depression (symptoms) | Critically low |

| Courtin & Knapp et al., (2017) | Scoping Review | 15 countries overall, including western Europe (UK and Netherlands) and USA | 29 | Older Adults | 2000–2013 | Narrative Synthesis | Loneliness and social isolation | Depression | Critically low |

| Worrall et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | Not reported | 37 | Older Adults | 2007–2018 | Narrative Synthesis | Loneliness, Social Support & Social Network | Depressive symptom (severity) | Low |

| Depression – social support and/or social networks | |||||||||

| Edwards et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | Germany, Columbia, USA | 13 | Active Christian clergy-members (7.6% United Methodist; 39.2% Catholic; 12.2% Presbyterian; 1% other Protestant denominations) | 1997–2019 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Depression (no specific clarification about whether depression diagnosis or symptoms) | Critically low |

| Gariépy et al., (2016) | Systematic Review | USA, Canada and Europe, Australia and New Zealand | 100 | All ages in general population | 1988–2014 | Meta-analysis | Social Support | Depression (depression diagnosis or depressive symptoms) | Critically low |

| Guo & Stensland et al., (2018) | Systematic Review | USA | 32 | Older Chinese and Korean immigrants in USA | 1996–2016 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support & Social Networks | Depression (depressive symptoms) | Critically low |

| Guruge et al., (2015) | Scoping Review | Canada | 34 | Immigrant women youth | 1990–2013 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Depression (depressive symptoms) (n = 18 studies), or determinants of mental health in general (n = 16) | Critically low |

| Hall et al., (2018) | Systematic Review | United States | 7 | LGBQ adolescents (15–24 years of age) | 2000–2013 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support (from friends and family, sexuality specific social support) | Depression (symptom severity or threshold for clinically significant depressive symptoms) | Critically low |

| Mohd et al., (2019) | Systematic Review | China, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, Macau, Thailand | 24 | Older adults living in Asia | 2001–2016 | Narrative Synthesis | Structural and functional social support (includes social network size as an aspect of structural social support) | Depression (self-reported or diagnosed) | Critically low |

| Qiu et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | China | 4 | Chinese adults > age 55 | 2005–2019 | Meta-analysis | Social Support | Clinician diagnosis of depression | Critically Low |

| Rueger et al., (2016) | Meta-analytic Review | Finland, Israel, Romania, Turkey, Belgium, Brazil, Burundi, Hong Kong, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Kenya, Korea, Mexico, Russia (k = 2 each); Austria, Croatia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Japan, Kuwait, Poland, Portugal, Puerto Rico, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Australia, United States | 341 | Children and adolescents | 1983–2014 | Meta-analysis | Social Support | Depression (diagnosis, symptoms) | Low |

| Santini et al., (2015) | Systematic Review | USA, Asia, Europe | 50 | Adults from general population | 2004–2013 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support & Social Networks | Depression (symptoms, presence, onset or development) | Low |

| Schwarzbach et al., (2014) | Systematic Review | USA, Asia, Europe | 17 | Older adults | 1985–2012 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support & Social Networks | Depression (dimensional diagnosis, prevalence, incidence) | Critically low |

| Visentini et al., (2018) | Systematic Review | Finland, Hungary, India, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, USA | 18 | Patients with chronic depression | 1986–2015 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support & Social Networks | Chronic Depression (diagnosis) | Low |

| Perinatal/postnatal depression & anxiety - social support | |||||||||

| Bayrampour et al., (2018) | Systematic Review | USA, Canada, Hungary, Turkey, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Poland, Germany, Bangladesh, UK, South Africa, Greece | 22 | Pregnant women | 1982–2015 | Meta-analysis, Narrative Review | Social Support | Anxiety (symptoms, generalised anxiety, overall anxiety disorders in pregnancy) | Low |

| Bedaso et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | Jordan, Nigeria, Italy, UK, Indonesia, Canada, Ethiopia, Jamaica, Turkey, Singapore, USA, China, Hungary, Greece, Germany, South Africa, Hong Kong, India, Finland, Malaysia, Sweden, Iran, Malawi, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Taiwan, Tanzania | 63 | Adult pregnant mothers | 2004–2019 | Meta-analysis, Narrative Review | Social Support | Any diagnosed depressive disorders and general anxiety disorder according to ICD and DSM or depressive disorders and general anxiety disorder based on a valid screening tool | Moderate |

| Desta et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | SNNPR, Oromia, Amhara, Harar, Addiss (regions within Ethiopia) | 4 | Postpartum women with postpartum depression in Ethiopia | 2018–2020 | Meta-analysis | Social Support | Postpartum depression | Critically low |

| Nisar et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | 23 regions of Mainland China | 10 | Chinese women in perinatal period | 1996–2018 | Meta-analysis | Social Support | Perinatal depression | Moderate |

| Qi et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | China | 9 | Chinese women who have given birth to at least one child including those living in countries other than China | 2004–2020 | Meta-analysis | Social Support | Onset of post-partum depression | Critically Low |

| Razurel et al., (2013) | Systematic Review | UK, Canada, Taiwan, Israel, Australia and USA | 25 | Perinatal mothers | 2000–2009 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Postnatal depression (symptoms) | Critically low |

| Tarsuslu et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | Global | 5 | Fathers post-partum | 2010–2019 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Post-partum depression measured on differing scales but established ones. | Critically Low |

| Tolossa et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | Ethiopia | 5 | Women in postpartum period with all studies conducted in Ethiopia | 2016–2019 | Meta-analysis, Narrative Review | Social Support | Secondary outcome was to determine the main risk factors associated with PND with social support being one of the risk factors examined. | Low |

| Zeleke et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | Ethiopia | 3 | Postnatal mothers | 2010–2020 | Meta-analysis, Narrative Review | Social Support | Diagnosis of PND. Does not specify if related to either onset or severity, just ‘more likely to have it’ | Low |

| Depression, anxiety, and OCD – loneliness and social isolation or social support or social capital | |||||||||

| Gilmour et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | United States, South Korea, Portugal, Hong Kong, Belgium, Taiwan | 5 | Young adults | 2011–2018 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Mental health conditions; Depression and anxiety | Low |

| Loades et al., (2020) | Rapid Systematic Review | USA, China, Europe and Australia, India, Malaysia, Korea, Thailand, Israel, Iran, and Russia | 63 | Children/adolescents | 1983–2020 | Narrative Synthesis | Isolation | Depression & anxiety (symptom severity) | Moderate |

| Mahon et al., (2006) | Meta-analytic Review | Not reported | 30 | Adolescents (11–23 years of age) | 1980–2004 | Meta-analysis | Loneliness | Depression (general term “depression”) and ‘social anxiety’, Social support | Critically low |

| Anxiety, and ADHD - loneliness | |||||||||

| Hards et al., (2021) | Rapid Systematic Review | United States, Australia, Canada, China, Taiwan | 8 | Predominantly children or adolescents with heightened distress, mental health problems, or diagnoses based on internationally recognized (DSM or ICD) | 1993–2020 | Narrative Synthesis | Loneliness | Depression, anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) | Low |

| Anxiety – social support and/or social network | |||||||||

| Zimmermann et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | Global | 4 | Adults in general population who had a clinically diagnosed anxiety disorder. They looked at anxiety disorders across the spectrum (outcomes included OCD, Specific Phobia, SAD, GAD etc.) | 2010–2014 | Narrative Synthesis | Measure of social support not defined at top level; underlying studies either measured social support (via scales) with one study looking at quantity of social network and experience of close friendships | Social support was looked at in relation to social anxiety disorder (2 studies) and as a risk factor for any anxiety disorder (1 study) | Moderate |

| PTSD – social support | |||||||||

| Allen et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | Global but predominately USA and China | 50 | Child and adolescents | 1996–2019 | Meta-analysis | Social Support | Primary aim was to evaluate the overall relationship between social support and PTSD; secondary aim was to investigate the relationship between severity of PTSD relative to levels of social support | Moderate |

| Blais et al., (2021) | Meta-analytic Review | U.S. | 38 | Service members or veterans in the U.S. military | 1998–2019 | Meta-analysis | Types of Social support (perceived, enacted, structural, or social negativity); Sources of social support (military v. non-military); timing of social support (during deployment v. not during deployment) | Severity of PTSD symptoms | Moderate |

| Tirone et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | Primarily USA | 29 | Adult betrayal trauma survivors | 2000–2019 | Meta-analysis | Social Support | PTSD symptom severity (understanding the moderators of) | Critically Low |

| Trickey et al., (2012) | Meta-analytic Review | UK, USA | 4 | Children and adolescents (6–18 years) | 1996–2007 | Meta-analysis | Low social support (including feeling isolated/ excluded and perceived alienation) | PTSD symptom severity and diagnosis | Critically Low |

| Zalta et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | Global | 150 | All participants had to be exposed to a DSM-5 criterion event and had to be > 18 years; treatment studies were excluded and study population chosen on basis of their PTSD were excluded | 1980–2019 | Meta-analysis | Social support defined as negative social reactions; perceived level of support’ structural support; enacted support | PTSD symptom severity | Moderate |

| PTSD and Depression – social support and/or social network | |||||||||

| Scott et al., (2020) | Systematic Review | Global | 10 | Adults 18 years plus following bereavement after sudden / violent death | 1988–2019 | Narrative Synthesis | Informal Social Support | Relevant outcome to this was a psychiatric symptoms (including depression and PTSD) either clinical diagnosis or measure of symptom severity | Moderate |

| Psychosis – loneliness | |||||||||

| Chau et al., (2019) | Meta-analytic Review | USA, UK, Netherlands, Poland, Israel, USA, Germany, Ireland, Denmark, France, Australia | 31 | Adults with and without clinical diagnosis of psychosis | 1995–2018 | Meta-analysis | Loneliness | Psychosis (positive and negative symptoms, psychotic experiences) | Low |

|

Michalska da Rocha et al., (2018) |

Systematic Review | United States, Great Britain, Australia, Germany, Israel, Poland | 13 | People with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder | 1993–2016 | Meta-analysis | Loneliness | Psychosis (symptoms) | Moderate |

| Lim et al., (2018) | Systematic Review | Ireland, Israel, Philippines, Poland, UK, USA, Serbia | 9 | People with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder | 1995–2016 | Narrative Synthesis | Loneliness | Psychosis (diagnosis) | Moderate |

| Psychosis – social support and/or social networks | |||||||||

| Degnan et al., (2018) | Systematic Review | USA, UK, Poland, Australia, Denmark, Austria | 16 | Adults with schizophrenia | 1989–2013 | Meta-analysis, Narrative Review | Social Networks | Schizophrenia (symptomatic and/or functional outcome) | Moderate |

| Gayer-Anderson and Morgan (2013) | Systematic Review | North America, Europe, Australia, Korea | 38 | People aged 16–64 years, first episode psychosis and general population samples with psychotic experiences or schizotypal traits | 1976–2011 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support & Social Networks | Early psychosis (first episode) | Critically low |

| Palumbo et al., (2015) | Systematic Review | USA, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Poland, Spain, UK, Nigeria, Brazil | 20 | Adults with a diagnosed psychotic disorder | 1976–2013 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Networks | Psychosis (a standardised diagnosis of either schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, “narrow schizophrenia” spectrum disorder, or “psychosis”) | Critically low |

| Bipolar disorder – social support | |||||||||

| Greenberg et al., (2014) | Systematic Review | Not reported | 15 | Adults with bipolar disorder | 1985–2010 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Bipolar disorder (general term “bipolar disorder”, manic or depressive episodes) | Critically low |

| Studart et al., (2015) | Systematic Review | Not reported | 13 | People with bipolar disorder | 1985–2012 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Bipolar disorder (general term “bipolar disorder”, symptoms, mania and depression) | Critically low |

| Depression, Bipolar, Psychosis & Anxiety disorders – loneliness & perceived social support | |||||||||

| Wang et al., (2018) | Systematic Review | North America, Europe, Israel | 34 | Adults with mental illnesses | 1988–2016 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Isolation, Social Support | Depression, bipolar, schizophrenia/schizoaffective, anxiety, mixed mental illness (relapse, measures of functioning or recovery, symptom severity, global outcome) | Moderate |

| Eating disorders – social support | |||||||||

| Arcelus et al., (2013) | Systematic Review | Not reported | 4 | Patients with eating disorders (anorexia and/or bulimia), along with non-clinical populations (university students) and controls | 1992–1999 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Eating disorders (symptom severity) | Low |

| Mental ill-health in general (no specified mental health condition) – social support | |||||||||

| Casale & Wild, (2013) | Systematic Review | Not reported | 17 | Adult caregivers who have HIV and adult caregivers caring for HIV/AIDS affected children | 1995–2010 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Mental Health outcomes | Critically low |

| Tajvar et al., (2013) | Systematic Review | Middle Eastern Countries | 9 | Older Adults | 1986–2010 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Mental Health outcomes | Low |

| Mental ill-health in general (no specified mental health condition) – individual-level social capital | |||||||||

| De Silva et al., (2005) | Systematic Review | UK, Scotland, USA, Russia, South Africa, Zambia | 14b | Adults with common mental disorders (depression and anxiety) | 1992–2003 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Capital | Common mental disorders (onset and symptoms) | Critically low |

| Ehsan & De Silva et al., (2015) | Systematic Review | Mexico, USA, UK, Greece, Japan, Australia | 33b | Adults with common mental disorders (depression and anxiety) | Inception-2014 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Capital | Common mental disorders (onset and symptoms) | Low |

| COVID-19 context | |||||||||

| Covid-19 Perinatal/postnatal depression - social support | |||||||||

| Fan et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | Israel, Sri Lanka, China, Turkey, Italy, Belgium, Colombia, Japan, the United States, Iran | 19 | Pregnant women | 2020 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Psychiatric symptoms of depression and anxiety | Low |

| Covid 19: PTSD – social support | |||||||||

| Hong, Kim and Park, (2021) | Systematic Review | China, Italy, Spain, Israeli, Ireland, USA, Poland | 16 | All adults | 2020 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Support | Post-traumatic stress symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSS and PTSD), depression, anxiety | Critically low |

| Covid: 19: Eating disorders – social isolation | |||||||||

| Miniati et al., (2021) | Systematic Review | Saudi Arabia, Spain, UK, Italy, Turkey, France, Lebanon, Australia, USA, Canada, Germany | 21 | Existing eating disorder diagnosis | 2020–2021 | Narrative Synthesis | Social Isolation | Eating disorders (Anorexia, Bulimia, Binge Eating) | Critically low |

a Review paper states that 88 studies were included in the review, but only 70 papers were referenced and authors did not respond to requests for the full list. The types of study included in this umbrella review is derived from the 70 studies that are referenced in the paper.

B Only individual-level social capital studies are included in this umbrella review.

Abbreviations: DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (diagnostic manual); ICD = International Classification of Diseases (diagnostic manual); OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder; SAD = seasonal affective disorder; GAD = generalised anxiety disorder; PTSS = Post-traumatic stress symptoms; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder UK = United Kingdom; USA = United States of America

Table 3.

Summary of Evidence (N = 53 studies)

| Author & year | Population | Outcome | Types of studies included | Main Relevant Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression – loneliness | |||||

| Cohen-Mansfield et al., (2016) | Older Adults | Depression | 11 cross-sectional, 1 longitudinal study | Loneliness was significantly associated with ‘depression’ both cross-sectionally (11 studies) and longitudinally (1 study, which also found a cross-sectional association) (12 relevant studies in total). The definition of depression included studies measuring low mood and uselessness (1 study), lack of taking initiative (1 study) and expecting negative reactions from caregivers (1 study), as well as studies measuring ‘depressive symptoms’ (1 study). What was meant by ‘depression’ in other studies was not specified (8 studies). | |

| Erzen & Çikrikci (2018) | Adults | Depression (unclear if refers to symptom severity or diagnosis) | 62 cross-sectional and 8 longitudinal studies | Meta-analysis found loneliness was moderately significantly associated with depression (r = 0.5). This relationship held when carers, elderly, students, patients were examined separately. | |

| Depression – loneliness, social support and social network size | |||||

| Choi et al., (2015) | Older Adults | Depression symptoms | 8 cross-sectional studies | Both subjective (e.g., loneliness, perceived social support) and objective (e.g. low social engagement, low social support) types of social isolation were associated with higher depressive symptoms. | |

| Courtin & Knapp et al., (2017) | Older Adults | Depression | 18 cross sectional, 8 longitudinal, 3 mixed methods | The authors report that the evidence reviewed ‘clearly showed’ that loneliness is an independent risk factor for depression in old age. The relationship between social isolation and depression was unclear as only three studies included in the review had looked at this, although 2/3 did find some evidence for an association. | |

| Worrall et al., (2020) | Older Adults | Depressive symptom severity | 26 cross-sectional and 11 longitudinal studies |

Cross-sectional studies suggested that loneliness is associated with depressive symptoms (4/5 studies, remaining 1 study found no significant relationship). ‘Substantial’ evidence (29/36 studies) for social support as a protective factor from depression, with consistent findings across cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (remaining 7 studies found no significant relationship). Findings on the effect of larger social networks varied within and between cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (2/5 studies found protective effect, 3 found no significant relationship). |

|

| Depression – social support and/or social networks | |||||

| Edwards et al., (2020) | Active Christian clergy-members (7.6%United Methodist; 39.2% Catholic; 12.2% Presbyterian; 1% other Protestant denominations) | Association between rates of depression and level of social support among Christian Clergy | 3 longitudinal and 10 cross-sectional studies | (1) Increased rates of depression in Christian clergy are associated with perceived levels of social support. (2) A small-to-moderate negative associations between social support and depression, with stronger associations in the two studies using single items or their own questions to measure social support compared to those using standardised measures. | |

| Gariépy et al., (2016) | All ages | Depression (diagnosis or symptoms) | 70 cross-sectional and 30 longitudinal studies |

For children and adolescents (31 studies), adults (36 studies) and older adults (33 studies), meta-analyses found significant associations between higher social support and lower/absent depression symptoms (pooled OR = 0.2, OR = 0.74 and OR = 0.56 respectively). Sources of support most consistently seem to be protective against depression are: parents, teachers and family in children and adolescents (findings were less consistent for friends); first spousal support, then family, then friends and then children for adults; support from spouses, followed by friends for older adults (support from children showed less consistent findings). Parental and family support was particularly important for girls. Emotional support was most consistently associated with lower depression in adults. Findings were similar for adult men and women, whereas a significant protective association was more consistently found in girls and older men than boys or older women. For children/young people and older adults, estimates were stronger for cross-sectional versus cohort studies. |

|

| Guo & Stensland et al., (2018) |

Older Chinese and Korean immigrants in USA |

Depressive symptoms | 30 cross-sectional and 2 longitudinal studies |

Eight out of nine included studies reported that low or diminished social support over time was associated with more depressive symptoms. Three studies that examined different types of support found that emotional support was associated with lower depression. Mixed findings regarding whether the size and/or strength of social networks is associated with depression: about half reported a negative relationship and half found no significant association. Living arrangements, frequency of kin/non-kin contact, and positive family relations were not consistently related to depression, but negative family interactions were. |

|

| Guruge et al., (2015) | Immigrant women and youth | Depressive symptoms | 6 cross-sectional and 6 longitudinal, 22 qualitative studies | Association between lack of social support and depression among immigrant women was well supported (including by 5 longitudinal quantitative studies), although one longitudinal study failed to find a significant association. Poor social support, including from their spouse, was identified as one of the key risk factors for postpartum depression in immigrant women (2 longitudinal, 1 qualitative). | |

| Hall et al., (2018) | LGBQ adolescents (15–24 years of age) | Depression (symptom severity or clinical threshold) | 3 cross-sectional and 4 longitudinal studies | 5/6 cross-sectional studies found that participants with greater support from friends and/or family (in one case measured as family closeness and contact with friends) experienced lower depression symptoms. A further 3 papers report on the same longitudinal study and 2 of these found cross-sectional and longitudinal negative associations between social support from friends and/or family and depressive symptoms (although the review itself does not clearly delineate cross-sectional and longitudinal associations). A fourth longitudinal paper using a different sample found that depression was negatively associated with social support at T2 (although not clear from the reporting whether this is over time). | |

| Mohd et al., (2019) | Older adults in Asia | Depression (self-reported or diagnosed) | 18 cross-sectional and 6 longitudinal studies |

Eleven cross-sectional studies (8 rated as good quality) found that low social support was significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms. Higher satisfaction with social support significantly associated with lower depression symptoms in 2/3 studies (1 prospective cohort). Support from family (3 studies, of which 1 was a prospective cohort design) and friends (1 study) was found to reduce depressive symptoms. Emotional support was associated with reduced depression symptoms in six studies including 3 prospective cohort studies. 5/12 cross-sectional studies found good perceived social support was associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Significant association between having a larger size of network and fewer depressive symptoms (2 prospective cohort studies, 1 cross-sectional). A larger social network composed of mostly family members was associated with reduced rate of depression compared with having friends (1 prospective cohort study, 1 cross-sectional). |

|

| Qiu et al., (2020) | Chinese adults > age 55 | Risk factors for Depressive symptoms | 4 cross-sectional studies in meta-analysis involving social support | Fair or good social support was found to be a protective factor against onset of depression (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.84–0.97). | |

| Rueger et al., (2016) |

Childhood and Adolescence (Ages under 20) |

Depression (diagnosis, symptoms) | 293 cross-sectional and 48 longitudinal studies | Meta-analysis found social support was significantly moderately associated with depression (r = 0.26), with a particularly strong effect size for available (i.e., perceived to be there if needed) versus enacted support. This significant association held for different sources of support: family, teacher, general peer, and close friend, but associations were larger for support from family and the general peer group (then teachers, then close friends). No gender differences were found. The association between peer social support and depression was stronger for children and younger adolescents than for older adolescents. The relationship between family social support and depression was consistent across all ages. | |

| Santini et al., (2015) | Adults from general population | Depression (symptoms or diagnosis) | 28 cross-sectional and 22 longitudinal studies |

The strongest and most consistent findings were significant negative associations between depression and perceived emotional support, perceived instrumental support, and large, diverse social networks. Perceived emotional support (PES) significantly negatively associated with depressive symptoms in 32/35 studies: 17 were cross-sectional studies and 14 of were prospective studies (2 low quality, 7 moderate and 5 good) and found that higher levels of PES were protective against depression, whilst lower levels were associated with presence/onset/development of depression. Two of the 3 studies that failed to find a significant association were prospective studies of moderate quality. Similar negative associations were found for 8/12 studies for received emotional support (5 prospective) and 11/12 studies of perceived instrumental support (3 prospective). All 3 studies that looked at both perceived and received social support found the former was more strongly associated with depression (2 prospective). Findings for received instrumental support were mixed: 2/10 studies found a negative relationship, 3/10 found a positive relationship and 4/10 not finding a significant association and 1 prospective study found received emotional and instrumental support predicted symptom deterioration only in people with depression at baseline. 5/8 studies found emotional support to more strongly associated with depression than instrumental (2 prospective of high quality) whereas 3 studies concluded the opposite (1 prospective moderate). Social support from friends was equally important in terms of predicting depression as family support (5/7 studies, 1 prospective) although 2 prospective studies found that only family had an effect. Large social networks were found to be protective against depression in 9/13 studies (5 prospective, high quality) whereas 4 studies found no significant association (2 prospective). Four cross-sectional studies found a significant negative relationship between network diversity and depression outcomes 9/12 studies found an association between living alone or without a partner positively associated with depression (4 prospective). |

|

| Schwarzbach et al., (2014) | Older adults | Depression (dimensional diagnosis, prevalence, incidence) | 10 cross-sectional and 7 longitudinal studies |

Cross-sectional studies found social support (7/9 studies), emotional support (4/7 studies) and relationship quality (5/5 studies) were negatively associated with depression symptoms. These associations were supported by longitudinal studies: social support (3/4 studies), received emotional support (2/3 studies) and satisfaction with social support (2/2 studies) were associated with lower depression. 4/6 cross-sectional studies suggested larger and more diverse networks were associated with lower depression symptoms, and this was supported by 2 longitudinal studies. |

|

| Visentini et al., (2018) | Patients with chronic depression | Depression diagnosis | 5 cross-sectional, 5 case-control, 7 longitudinal, 1 qualitative studies |

Patients with chronic depression rated their perceived social support significantly lower than those in the healthy population (4/6 studies; 1 study found no difference comparing women with dysthymia to those without a history of mood disorder; 1 study found fewer friends before onset of depression in the patient group compared to healthy controls but no difference in perception). 6/8 studies found chronic depression was associated with significantly lower perceived social support compared to individuals with non-chronic depression disorders or who had recovered and remitted. One study found no significant difference in social support to ‘count on’ between those with chronic depression and who had recovered. Social networks of patients with chronic depression appeared to be smaller than those of healthy individuals, patients with non-chronic major depression and other disorders. |

|

| Perinatal/postnatal depression & Anxiety - social support | |||||

| Bayrampour et al., (2018) | Pregnant women | Anxiety (symptoms or diagnosis) | 10 cross-sectional, 12 longitudinal/prospective studies | Of 14 studies that were rated as of moderate or strong quality, no studies failed to find a bivariate association, 9 studies found a multivariate negative association between social support and antenatal anxiety, but 2 studies failed to do so. | |

| Bedaso et al., (2021) | Pregnant mothers (18 years +) | Any diagnosed depressive disorders and general anxiety disorder according to ICD and DSM or depressive disorders and general anxiety disorder based on the valid screening tool | 37 cross-sectional, 26 longitudinal studies |

Low social support found to have a significant positive association with antenatal depression AOR: 1.18 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.41) based on 45 studies, 57% of which were cross sectional. 37 of 45 studies reported a significant positive correlation. In relation to antenatal anxiety, AOR: 1.97 (95% CI: 1.34, 2.92) based on 9 studies, 8 of which were cross sectional and 6 included longitudinal analysis. Narrative conclusions were consistent with this. 15 studies in depression, 12 reported a significant relationship (correlation or association) and of the 8 anxiety ones, 7 reported a significant relationship. |

|

| Desta et al., (2021) | Postpartum women with postpartum depression in Ethiopia | Prevalence of post-partum depression | 4 cross-sectional studies | Poor social support was a common predictor that significantly associated with increased risk of postpartum depression [POR = 6.27 (95%CI: 4.83, 8.13)] among postpartum women. | |

| Nisar et al., (2020) | Chinese women in perinatal period | Onset of perinatal depression | 10 cross-sectional studies | (1) The prevalence of perinatal depression in Chinese women was negatively associated with economic status and social support. (2) Social support before and after childbirth was a strong protective factor for perinatal depression. | |

| Qi et al., (2021) | Chinese women who have given birth to at least one child including those living in countries other than China | Risk factors for the onset of post-partum depression | 4 case control, 5 cohort studies | General agreement with prior studies that social support can be a protective factor against PPD (OR 2.57; 95% CI 2.32–2.85) but one of the weaker findings across wider evaluation of risk factors. | |

| Razurel et al., (2013) | Peri- and Post-natal Mothers | Periand Post-natal depression symptoms | 9 cross-sectional, 14 longitudinal/prospective, 1 randomised controlled trial RCT, 1 survey design studies | Nine longitudinal studies found lower scores for postnatal social support were related to higher scores of postnatal depressive symptoms. Negative correlation between satisfaction with family social support and postpartum depressive symptoms (3 cross-sectional studies). Three longitudinal studies found that social support from the partner seems to be a protective factor against postpartum depressive symptoms. | |

| Tarsuslu et al., (2020) | Fathers aged 30–36 on average in post-partum period (< 1 year.) | Post-partum depression measured on differing scales but established ones. No further information regarding severity or onset given | 3 cross-sectional, 2 cohort studies (studies relevant to our research question) | Social support cited as one of risk factors for PPD, with five of included studies relevant to this. This was judged to be one of stronger impacting factors (age, economic status, ethnicity alongside it) but clear comparison of importance could not be made. | |

| Tolossa et al., (2020) | Ethiopian women in post-partum period | Prevalence of postpartum depression | 5 cross-sectional studies | All five studies showed a significant association between social support and PPD. Pooled results showed PPD 6.5x higher among women who lacked social support (95% CI 2.59, 16.77). | |

| Zeleke et al., (2021) | Mothers in post-partum period (< 1 year.) | Prevalence of postpartum depression | 3 cross-sectional studies | Poor social support gave increased odds (OR = 3.57;95% CI[2.29–5.54]) of developing PPD. | |

| Depression, anxiety, and OCD – loneliness and social isolation or social support or social capital | |||||

| Gilmour et al., (2020) | 70% Young adults | Mental health conditions with specific reference to depression and anxiety. | 5 cross-sectional studies | (1) Facebook-based social support was found to predict better general mental health. (2) Social support drawn from Facebook was predictive of lower levels of depression, depressive mood, and symptomology. (3) Within the high socially anxious group, Facebook-based social support significantly predicted greater psychological well-being, whereas face-to-face social support did not. Within the low socially anxious group, face-to-face social support significantly predicted greater psychological well-being; however, Facebook-based social support had no significant relationship with psychological well-being. (No statistics available.) | |

| Loades et al., (2020) | Children & Adolescents | Depression & anxiety symptom severity | 44 cross-sectional and 19 longitudinal studies |

45 cross-sectional studies examined the relationship between depressive symptoms and loneliness and/or social isolation: ‘most’ reported moderate to large correlations (r = 0.12–0.81) and 2 studies found lonely individuals were 5.8–40 times more like to score above clinical cut-offs for depression. 12/15 longitudinal studies found loneliness explained a significant amount of the variance in severity of depression symptoms several months to several years later. In 1 study, duration of peer loneliness not intensity was associated with depression 8 years later (from age 5 to 13); in contrast, family related loneliness was not independently associated with subsequent depression. 23 cross-sectional studies examined symptoms of anxiety and found small to moderate associations with loneliness/social isolation (r = 0.18–0.54); 1 study using odds ratios found loneliness was associated with increased odds of being anxious of 1.63–5.49 times. Two studies found duration of loneliness was more strongly associated with anxiety than intensity of loneliness. Social anxiety (r = 0.33–0.72) and generalized anxiety (r = 0.37–0.4) were associated with loneliness/social isolation (2 cross-sectional studies). 3/4 studies assessing the longitudinal effect of loneliness on anxiety found loneliness was associated with later anxiety (2 related to social anxiety specifically). Cross-sectional studies also found associations between social isolation/loneliness and panic (1 study), suicidal ideation (3 studies), self-harm (1 study) and disordered eating (1 study). One longitudinal study found internalising symptoms were associated with prior loneliness in primary-school-age children whereas another study found no association between adolescent suicidal ideation and prior loneliness. |

|

| Mahon et al., (2006) |

Adolescents (11–23 years of age) |

Depression (unclear if refers to symptoms, severity or diagnosis) | 30 (no information on breakdown but mostly cross sectional) |

Meta-analysis found significant positive relationship between depression and loneliness (r ~ 0.6) was found from 33 hypotheses derived from 30 studies. Meta-analysis found social anxiety was significantly positively associated with loneliness with a moderate effect size (r ~ 0.4; r = 0.35 when outliers were removed) (investigated via 15 hypotheses derived from 12 studies). |

|

| Anxiety and ADHD - loneliness | |||||

| Hards et al., (2021) | Predominantly children or adolescents with heightened distress, mental health problems, or diagnoses based on internationally recognized (DSM or ICD) | Depression, anxiety, ASD and ADHD | 8 cross-sectional studies | Seven studies examined the cross-sectional relationship between loneliness and severity of mental health symptomstr, four of which examined loneliness and social anxiety. Three studies reported socially anxious children as significantly lonelier than those not anxious with small to moderate effect sizes (0.31). Another two studies showed positive correlations between loneliness and severity of symptoms. For autistic participants, there were moderate association between anxiety and loneliness in both younger adolescents (< 14 years) (r = -0.33) and older adolescents (r=-0.44). | |

| Anxiety – social support and/or social network | |||||

| Zimmermann et al., (2020) | Adults in general population who had a clinically diagnosed anxiety disorder. They looked at anxiety disorders across the spectrum (outcomes included OCD, Specific Phobia, SAD (social anxiety disorder), GAD (generalised anxiety disorder etc.) | Anxiety (prevalence) | 4 longitudinal studies | Heterogenous findings but overall, a lack of social contact was not a risk factor but loneliness did show evidence of being one. In relation to underlying studies: social support was not a risk factor for SAD when adjusted for subthreshold SAD at baseline (1 study). In another study low social support was associated with x4 the risk factor for SAD when controlling for age and gender. In a third study after adjusting for age, income and current disease limited social contact did not present itself as a risk but perceived loneliness was a risk factor for any anxiety disorder. Coping skills, including social support, were found to be protective in the development of specific phobias (1 study). | |

| PTSD – social support | |||||

| Allen et al., (2021) |

Children and Adolescents (6–18 years of age) |

Overall relationship between social support and PTSD; relationship between severity of PTSD and degree of social support | 46 cross-sectional and 4 prospective/longitudinal studies | The current review found a weak correlation between social support (support from peers, family and teachers) and PTSD (r = -0.12, 95% CI -0.16 to -0.07, k = 41) in children and young people following trauma (War, Abuse, Hurricane, Community violence, Flood, Tornado, Cancer, Tsunami, Earthquake, Terrorist attack, Typhoon) with the strongest effect size for social support that were provided by teachers (r = -0.20, 95% CI, -0.15 to -0.24, k = 5); however, the effect size is still considered small. | |

| Blais et al., (2021) | Service members or veterans in the U.S. military | Severity of PTSD symptoms | 38 cross-sectional studies | The types of social support (e.g., perceived, enacted, structural) did not moderate the association between PTSD and social support; Lower levels of social support were associated with more severe PTSD symptoms: r = − 0.33 (95% CI:[− 0.38, − 0.27], Z = − 10.19, p < 0.001). | |

| Tirone et al., (2021) | Adult betrayal trauma survivors | PTSD symptom severity | 29 cross-sectional studies | Overall weighted effect size was small to medium (r = − 0.25) suggesting higher levels of positive support and lower levels of negative support were associated with lower PTSD symptom severity. Substantial degree of heterogeneity. Studies focusing on absence of social support reported a larger effect size than those reporting on positive presence of social support. | |

| Trickey et al., (2012) |

Children and Adolescents (6–18 years of age) |

Post- traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), both diagnosis and symptom severity | 4 (no information on breakdown) | A medium-to-large effect size was observed for a significant positive relationship between PTSD symptoms and low social support |

|

| Zalta et al., (2021) | All participants had to be exposed to a DSM-5 criterion event and had to be > 18 years; treatment studies were excluded and study population chosen on basis of their PTSD were excluded | PTSD symptom severity | 150 cross-sectional and longitudinal studies | Higher levels of social support were associated with lower PTSD symptom severity. Reporting cross sectional studies, longitudinal studies respectively, type of social support was a significant predictor of effect size: negative social reactions (r=-0.40 & r=-0.41); perceived support (r=-0.27 & r=-0.22); structural support (r=-0.19 & r=-0.21)) and enacted support (r=-0.15). | |

| PTSD and Depression – social support and/or social network | |||||

| Scott et al., (2020) | Adults 18 years plus following bereavement after sudden / violent death | Clinical diagnosis of PTSD or depression and symptom severity of the same | 9 cross-sectional; 1 longitudinal studies |

For depression: limited evidence that social support associated with reduced risk of clinical diagnosis; 4 studies reported positive association depression and reduced social support and two reported a partial association, 1 with limited association and 1 (poor quality) with strong correlation. PTSD: 6 studies reported partial association (nothing to suggest reduced symptom severity or less likely to meet level for clinical diagnosis), and 4 with positive association. |

|

| Psychosis – loneliness | |||||

| Chau et al., (2019) | Adults with and without clinical diagnosis of psychosis | Psychosis (symptoms, psychotic experiences) | 26 cross-sectional, 3 longitudinal, and 2 experimental design studies | Meta-analysis found a medium association between loneliness and positive psychotic experiences (r = 0.302; 30 studies: 3 longitudinal, 1 experimental, 26 cross-sectional) and paranoia (r = 0.448).There was a medium association between loneliness and negative psychotic experiences across 15 cross-sectional studies (r = 0.347).The associations between loneliness and both positive and negative psychotic experiences were significantly smaller among clinical (positive: r = 0.149; negative: 0.127) than non-clinical samples (positive: r = 0.389; negative: r =0.479). | |

|

Michalska da Rocha et al., (2018) |

People diagnosed with a psychotic disorder | Psychosis (symptoms) | 11 cross-sectional and 2 longitudinal studies | Meta-analysis found a moderate significant positive cross-sectional association between psychosis symptom severity and loneliness (r = 0.32) from 13 studies assessed as being of moderate quality. Although 2 longitudinal studies were included, the authors used cross-sectional baseline data or averages across timepoints. | |

| Lim et al., (2018) | People diagnosed with a psychotic disorder | Psychosis (diagnosis) | 9 cross-sectional studies |

Individuals with psychosis were found to be significantly lonelier than control participants in the general population (2 studies). One study found that both negative and positive symptoms correlated significantly with loneliness (and one study found that state anxiety partially mediates the relationship between anxiety and paranoia) but two studies failed to find a significant relationship between loneliness and psychotic symptom severity; a fourth study did not find a difference in loneliness between people diagnosed with schizophrenia with or without auditory hallucinations. Within people with psychosis, loneliness seems to be significantly associated with depression symptoms (4/6 studies). |

|

| Psychosis – social networks and/or social support | |||||

| Degnan et al., (2018) | Adults with schizophrenia | Schizophrenia (symptomatic and/or functional outcome) | 13 cross-sectional and 3 longitudinal studies | Meta-analytic pooled effect sizes found that smaller social network size was significantly moderately associated with more severe overall psychiatric symptoms (4/5 cross-sectional studies found significant associations, Hedge’s g=-0.53) and negative symptoms (7/8 studies including 1 longitudinal RCT, which was not included in the meta-analysis due to insufficient data, found a significant association; Hedge’s g=-0.75), but not positive symptoms (7 studies: 3 found significant cross-sectional negative associations but 6 other studies did not, and these included 3 longitudinal studies, 2 of which were not included in the meta-analysis due to insufficient data) or social functioning (3 cross-sectional studies including 100% schizophrenia samples). Narrative synthesis (which included three RCTs identified in the review) suggested that larger network size was associated with improved global functioning, but findings for affective symptoms and quality of life were mixed. 2 longitudinal RCTs reported significant cross-sectional but not temporal associations between more social contacts and greater global functioning. 3/5 cross-sectional studies found a positive association between number of social contacts and subjective quality of life. | |

| Gayer-Anderson and Morgan (2013) | Adults, first episode psychosis & general population samples with psychotic experiences or schizotypal traits | Early episode psychosis (first episode) | 36 cross-sectional studies |

11 studies (3 longitudinal) compared network size (various measures including total size and number of particular relationships, e.g., family, friends, confidants), frequency of contact or perceived level or adequacy of social support between samples of individuals with first episode psychosis and various comparison groups. All but one study, which compared number of friends in adolescence and frequency of contact 1-year pre-contact between Finnish versus Spanish cases, found at least one significant difference between social network size/structure/contact or social support: people with first episode psychosis were generally found to have smaller networks and less perceived and less satisfactory social support. There is some evidence that differences in network size are specifically in number of and contact with friends, with individuals with a first episode having significantly fewer friends than controls (3 studies, 2 longitudinal). There was also evidence from 3 studies (1 longitudinal) that people with first episode psychosis have fewer confidents than comparison groups. There were inconsistent findings in relation to whether duration of untreated psychosis and various social network measures (8 studies, 5 longitudinal). There was some support of associations between measures relating to social support and psychosis symptoms in general population samples (9/11 studies, 1 longitudinal). |

|

| Palumbo et al., (2015) | Adults (≥ 18 years of age) with psychotic disorder | Psychosis (diagnosis) | 16 cross-sectional and 4 longitudinal studies | Across included studies, patients with psychosis had on average 11.7 individuals in their social networks (range 4.6–44.9; 20 studies), while the average number of friends was 3.4 (range 1–5; 7 studies). Social networks were family-dominated with on average 43.1% of network members being relatives and 26.5% of members being ‘friends’ (14 studies). Higher levels of negative symptoms may be associated with smaller networks in individuals with psychosis (2 studies). No significant associations were found between social network size and age of onset/ length of prodromal period (1 study), or illness duration (2 studies). | |

| Bipolar Disorder – social support | |||||

| Greenberg et al., (2014) | Adults with bipolar disorder | Bipolar disorder (general term “bipolar disorder”, manic or depressive episodes) | 4 cross-sectional and 11 longitudinal studies | Individuals with bipolar disorder experience a lower level of social support than controls but the level of social support is similar to that of patients with other psychiatric diagnoses (5 cross-sectional studies). Negative cross-sectional associations were found between depressive symptoms (2 studies) or manic episodes (1 study). Findings from 10 longitudinal studies were mixed: social support has been found to influence manic or depressive episode relapse (4 studies) or only depressive relapse (4 studies) or manic relapse (1 study) or has not been found to affect relapse (1 study). | |

| Studart et al., (2015) | People with bipolar disorder | Bipolar disorder (general term “bipolar disorder”, symptoms, mania and depression) | 5 cross-sectional and 8 longitudinal studies | 12/13 studies (8 cohort) found associations between social support and bipolar symptoms, recovery or recurrence. Patients with bipolar disorder had low social support (1 cross-sectional) including when compared to controls or a community sample (3 cross-sectional studies). Low social support was associated with higher risk of relapse (2 cohort study), recurrence of manic and depressive episodes (1 cohort study, 1 cross-sectional) or just depressive episodes (2 cohort studies). Higher social support was found to be associated with quicker recovery from depressive episodes (1 cohort study). One 6-month cohort study found stronger treatment alliances were associated with higher patient social support. 1 cohort study with a 2-year follow up did not find a significant association between social support and onset or recovery. | |

| Depression, Bi-Polar, Psychosis & Anxiety Disorders – loneliness & perceived social support | |||||

| Wang et al., (2018) | Adults with mental illness | Depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders (relapse, measures of functioning or recovery, symptom severity, global outcome) | 34 longitudinal studies |

Prospective studies provide substantial evidence that people with depression who have poorer perceived social support have worse symptoms (11/13 studies, r = 0.10–0.61), recovery (6/7 studies) and functioning outcomes (2/5 studies). Some preliminary evidence was found for associations between perceived social support and outcomes in schizophrenia (2/2 studies but did not adjust for baseline scores), bipolar disorder (4/4 studies: lower perceived social support was consistently found to significantly predict greater depression, more impaired functioning and longer time to recovery; however, findings were inconsistent regarding severity of manic symptoms: 1/3 studies found perceived social support predicted more severe manic symptoms at follow-up). Significant associations between social support at baseline and outcomes at follow up for people with anxiety disorders (3/3 studies). One study found that lower perceived social support was predictive of more severe anxiety and depressive symptoms later on. Another found that higher perceived social support predicted greater remission rates at 6-month follow-up. A third study in older adults with Generalised Anxiety Disorder found an association between greater perceived social support at baseline and greater average quality of life over time (although without adjustment for baseline scores). Two studies looked at mixed samples with various mental health problems: one found that greater loneliness at baseline predicted more severe depression 1 year later controlling for baseline depression severity; the other study found greater perceived social support significantly predicted higher subjective quality of life 18 months later in people with severe mental illness but did not control for baseline levels of quality of life. |

|

| Eating disorder – social support | |||||

| Arcelus et al., (2013) | Patients with eating disorders & non-clinical populations (university students) and controls | Eating disorder diagnosis | 4 cross-sectional studies | 3/3 studies found significant associations between social support and eating disorder diagnosis. Individuals (3/4 studies were female only) with bulimia nervosa were found to have lower perceived social support from family and friends and more negative interactions (1 study), to have fewer strategies for seeking social support in response to stressful situations, controlling for anxiety and depression (1 study), and to both have fewer people to provide emotional support and be less satisfied with the quality of emotional support from relatives (1 study), compared to healthy controls. Individuals with eating disorders were found to have less structural social support and those with anorexia or bulimia were found to have less emotional or practical support compared to controls; those with anorexia were less like to identify a spouse/partner as a support figure compared to those with bulimia (1 study). | |

| Mental ill-health in general (no specified mental health condition) – social support | |||||

| Casale & Wild, (2013) | Adult caregivers who have HIV and adult caregivers caring for HIV/AIDS affected children | Psychological distress, depression, anxiety, psychiatric disorder symptoms | 16 cross-sectional and 1 longitudinal studies | Significant positive association between social support and mental health outcomes such as lower psychological distress or depressive symptoms (7 studies) but 2 studies found a negative relationship between social support and mental health outcomes: 1 study found receiving more social support was significantly related to higher depressive symptoms in low-income mothers with late stage HIV/AIDS and another study found that although support from neighbours/friends was associated with lower psychological distress, greater emotional support from children was associated with greater psychological distress. 1 study found that greater emotional closeness or attachment in relationships was associated with lower anxiety among HIV-positive mothers of young children. | |

| Tajvar et al., (2013) | Older people in Middle Eastern countries | Mental health | 9 cross-sectional studies | 8/9 studies found an inverse association between social support and poor mental health, although 3 studies did not control for potential confounders. There were consistent associations between perceived social support and mental health but not for received/available support (2 studies). | |

| Mental ill-health in general (no specified mental health condition) – individual-level social capital | |||||

| De Silva et al., (2005) | Adults with mental illness (common mental disorder, anxiety or depression) | Mental illness (diagnosis, symptoms, onset, recovery, time to recovery, incidence rates, death rate from suicide) | 14 cross-sectional studies | 14 studies measured individual-level social capital. Evidence for an inverse relation between cognitive social capital and common mental disorders was found (7/11 effect estimates). There was some evidence for an inverse relation between cognitive social capital and child mental illness (2/7 effect estimates), and between combined measures of social capital and common mental disorders (2/2 studies). Findings on associations between structural social capital and common mental disorder were mixed: 3/11 found an inverse association, 7/11 did not find a significant association, and 1/11 found a positive association. | |

| Ehsan & De Silva et al., (2015) | Adults with common mental disorders | Common mental disorders (risk of the disorder) | 27 cross-sectional and 6 longitudinal studies | High individual level cognitive social capital was associated with reduced risk of developing common mental health disorders (5/5 cohort studies), and this was supported by 27/33 cross-sectional effect estimates. Findings from 5 cohort studies were mixed for structural social capital (3/5 found a significant effect); cross-sectional findings were also mixed (11/25 effect sizes indicated an inverse relationship, 3/25 indicated a positive relationship). | |

| COVID-19 context | |||||

| PTSD – loneliness and social support | |||||

| Hong, Kim and Park, (2021) | All adults | Onset and severity of symptoms of PTSD | 16 cross-sectional studies |

Two studies found loneliness was the strongest predictor of PTSD. Three studies found that social support was associated with a decreased risk of impaired mental health such as anxiety, depression and PTSD. One study showed that social support from family was associated with decreased risk of depression and PTSS, whereas support from friends or partners was not associated with mental health. |

|

| Perinatal/postnatal depression - social support | |||||

| Fan et al., (2021) | Pregnant adult women | Likelihood of onset of depression or anxiety | 19 cross-sectional studies | Pregnant women were more concerned about others than themselves during Covid-19, and younger pregnant women seem to be more prone to anxiety, while social support can reduce the likelihood of anxiety and depression developing. | |

| Eating disorders – social isolation | |||||

| Miniati et al., (2021) | Adults with Eating disorders (Anorexia, Bulimia, Binge Eating) | Eating disorder severity (all eating disorders) | 17 cross-sectional, 2 qualitative, and 2 longitudinal cohort studies | Social isolation was related to the exacerbation of symptoms in patients with EDs who were home-confined with family members (No statistics available). | |