Abstract

Telehealth has been utilized to provide behavioral services to families with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other disabilities. This systematic review provides an update on current research pertaining to the use of telehealth to provide behavior analytic-based services and train caregivers in implementing behavioral procedures. This review also describes information on reported training components and caregivers’ procedural fidelity. Empirical studies were collected from five databases. Overall, the studies provide evidence of the utility of telehealth as a service delivery model for providing behavior analytic-based services and for training caregivers to implement behavioral assessments and procedures. The authors discuss potential considerations for developing training packages and training caregivers via telehealth. Future research should use experimental methods to determine effective components for training individuals via telehealth to use behavioral procedures with good fidelity as well as to detect other factors that may influence procedural fidelity.

Keywords: Telehealth, Autism spectrum disorder, Developmental disability, Applied behavior analysis, Parent training

Introduction

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other disabilities have benefited from behavioral interventions based on the principles of applied behavior analysis (ABA) to shape appropriate behavior or teach new skills (Ferguson et al. 2019; Wong et al. 2015). Although ABA-based services are in demand among families of children with disabilities, geography often poses a substantial barrier to gaining access to such services. For example, in the United States, families who live in urban areas or near universities tend to have easier access to ABA-based services, whereas there is often less access to these services for families who live in rural areas (Bulgren 2002; Ferguson et al. 2019; Murphy and Ruble 2012). In addition, many countries outside of the United States do not have any access to ABA-based services (Ferguson et al. 2019; Salomone et al. 2014).

One emerging model for delivering ABA-based services to families who live outside urban centers is telehealth, which is defined as the use of electronic technology to provide individuals with clinical services (Puskin et al. 2006). Although the use of telehealth to deliver ABA-based services is a relatively new approach, there is evidence that parents find telehealth to be an acceptable service delivery mechanism. In a study by Lindgren et al. (2016), parents who were provided ABA-based services via telehealth reported similarly high ratings of treatment acceptability compared to parents who received services at home with a behavior analyst on site and to parents who received services in a regional clinic via telehealth. In addition, two recent literature reviews by Neely et al. (2017) and Tomlinson et al. (2018) examined studies in which caregivers of individuals with intellectual and developmental disorders were coached to implement behavioral interventions via telehealth and found that, overall, caregivers reported high ratings of acceptability of being coached by behavior therapists via telehealth. Considering the issue of limited access to ABA-based services in many areas and evidence indicating telehealth is an acceptable option for service delivery, further in-depth analysis of the use of telehealth is warranted.

A series of recent publications have demonstrated desirable ABA-based treatment effects of behavioral coaching provided via telehealth for individuals with disabilities (Barretto et al. 2006; Fisher et al. 2014; Lindgren et al. 2016; Wacker et al. 2013a). For example, Lindgren et al. (2016) compared outcomes of three groups of children who were provided with ABA-based services: (1) at home with a behavior analyst on site, (2) in a regional clinic with remote coaching via telehealth from a behavior analyst, and (3) at home via telehealth with remote coaching from a behavior analyst. Results indicated that all groups exhibited mean percentage reductions in problem behavior of 90% or greater, and there were no significant differences in problem behavior reduction among the three groups.

A number of recent empirical studies indicate that caregivers have successfully implemented behavioral procedures they learned from behavioral therapists via telehealth (Neely et al. 2017) and some scholars have considered the “effectiveness” of telehealth (Ferguson et al. 2019; Tomlinson et al. 2018). However, there is no agreed-upon index of what aspect of telehealth should be targeted for examination with regard to “effectiveness.” One literature review examined the extent to which studies using telehealth met quality indicators for evidence-based practice and concluded that much of the research on telehealth does not meet such quality indicators (Ferguson et al. 2019). Using a quality assessment rubric (Reichow et al. 2008), the authors determined that all group design studies included in the review were overall weak in quality and all single-case design studies were overall either “weak” or “adequate” in quality. Similar results were also found in the Tomlinson et al. (2018) review using the same rubric. However, two issues should be considered. First, it is important to consider the areas in which the authors found lack of quality and the extent to which those specific indicators affect the quality of the experimental design and the demonstration of a functional relation or treatment effect. Second, given that telehealth is not the independent variable in any of these studies, examining the quality indicators that support the effectiveness of telehealth is somewhat misleading. Telehealth in itself is not an independent variable or an intervention. It is a service-delivery mechanism, and the intervention component(s) and training provided via telehealth are the independent variable(s).

With regard to analysis of the quality of studies involving telehealth, Ferguson et al. (2019) assigned high ratings to very few single-case-design studies for presenting baseline data. They assigned high ratings to both group design and single-case-design studies for their descriptions of the independent and dependent variables. The indicators in both group and single-case-design studies that tended to result in lower scores pertained to descriptions of (a) the participants and (b) comparison groups (Ferguson et al. 2019). Although lack of such descriptions may preclude replication of a study, experimental control and treatment effects can still exist despite a lack of detailed participant descriptions. In the Tomlinson et al. (2018) review, the authors assigned low scores to single-case-design studies for presentation of stable baseline data and other criteria related to presenting data that portray experimental control. Additionally, they assigned low scores to single-case-design studies due to lack of Kappa statistics, blind raters, or procedural fidelity measures. They assigned low scores to group design studies for statistical analysis and sample size as well as lack of blind raters, effect size measures, and procedural fidelity measures. Again, although the presentation of stable baseline and intervention data in single-case-design studies and the use of effect sizes in group design studies are important in determining experimental rigor, experimental control, and replicability of a study, the inclusion of Kappa statistics and blind raters in single-case-design studies as well as large sample sizes in modified group design studies may not necessarily be an indication of telehealth as being “ineffective.”

Despite the authors of these reviews concluding that the evidence supporting telehealth is weak, the practice of training caregivers via telehealth should not be discounted. It is important to note that telehealth is not an evidence-based practice for addressing behavior change. Rather, it is a mechanism by which professionals can provide services and teach others to implement evidence-based practices. Although meeting all quality indicators is an important priority within research to provide strong evidence in support of particular assessments, interventions, and training practices, studying those specific practices as they are delivered via telehealth should be scrutinized when examining the utility of telehealth as a service delivery mechanism. If the goal is to use telehealth to increase access to effective services, an important question to be asked is: Under what conditions is training via telehealth effective for teaching caregivers to implement ABA-based assessment and interventions?

Therefore, one interest may be to examine training components used to teach caregivers to implement behavioral procedures. Neely et al. (2017) reviewed the various training components researchers have used most often while providing training in behavioral procedures to caregivers via telehealth. The authors found that, out of 19 studies involving the use of telehealth and training caregivers, the most common training components used were performance feedback, vocal instructions, and written instructions. Although feedback and instructions are the most common training components, these components and others have been combined to form a variety of training packages for use via telehealth. For example, in studies by Dimian et al. (2018), Martens et al. (2019), and Wacker et al. (2013a, b), researchers taught caregivers to implement functional communication training (FCT) with child participants. Although all caregiver participants across all three studies were taught similar procedures, the researchers in each study used vastly different treatment packages. In Wacker et al. (2013a, b), caregiver participants were provided with more structured and standardized training involving a variety of training components, such as a manual with extensive information about ABA-based procedures used in the study, a formal presentation on ABA-based principles and procedures, and vocal instructions during live sessions. Dimian et al. (2018) also used a structured training package but with fewer training components. Researchers used task analyses of the procedures implemented as a guide for providing vocal instructions and performance feedback to parents during live sessions. Martens et al. (2019) used minimal training components, involving only vocal instructions to caregivers during live sessions and prompting of specific steps when needed. Considering the spectrum of training components and packages used in the literature, it may be difficult to identify the necessary and sufficient methods for effectively training caregivers via telehealth. Thus, when investigating the current literature, in addition to gathering information regarding training components used, it might of interest to examine levels of fidelity reported given the specified training components. Doing so may provide preliminary information regarding promising approaches for training caregivers via telehealth, which in turn may advance telehealth as a consistently effective and generalizable service delivery mechanism.

Study Purpose

Previous literature reviews have provided a synthesis on literature related to caregiver training via telehealth with additional aims, such as providing information on the acceptability of telehealth (Tomlinson et al. 2018), the methodological quality of telehealth literature (Ferguson et al. 2019; Tomlinson et al. 2018), and the impact of different training packages on the procedural fidelity of caregivers implementing ABA-based procedures (Neely et al. 2017). The purpose of this literature review is to (1) provide an update on current research pertaining to the use of telehealth to provide ABA-based training to caregivers of individuals with ASD and other disabilities and (2) document and examine training components used and procedural fidelity levels reported across telehealth studies. Similar to Neely et al. (2017), we aimed to learn more about potentially promising practices for implementing effective training to caregivers via telehealth. The current review contributes to the literature by synthesizing results of the literature that describes caregiver training via telehealth and to spark future research pertaining to specific training components and procedural fidelity.

Method

Search Procedures and Search Terms

In March 2019, the authors conducted a systematic literature search. We used similar databases and search terms that Ferguson et al. (2019) and Neely et al. (2017) used. The following databases were used: Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO, Scopus, ERIC, and MEDLINE. Similar to Ferguson et al. (2019) and Neely et al. (2017), results were restricted to peer-reviewed or academic articles and were not restricted based on year of publication. The terms used for the search described individuals with ASD or a developmental disability and telehealth. The terms were used in combination to identify articles that included both descriptions. The search terms used which described individuals with disabilities were Autis*, Asperger, “ASD”, “PDD-NOS”, and “Developmental Disab*.” Terms used which described telehealth were telehealth, telepractice, telemedicine, videoconferenc*, “distance education”, “distance train*”, teleconference, telecare, “distance learn*”, and Elearn*.

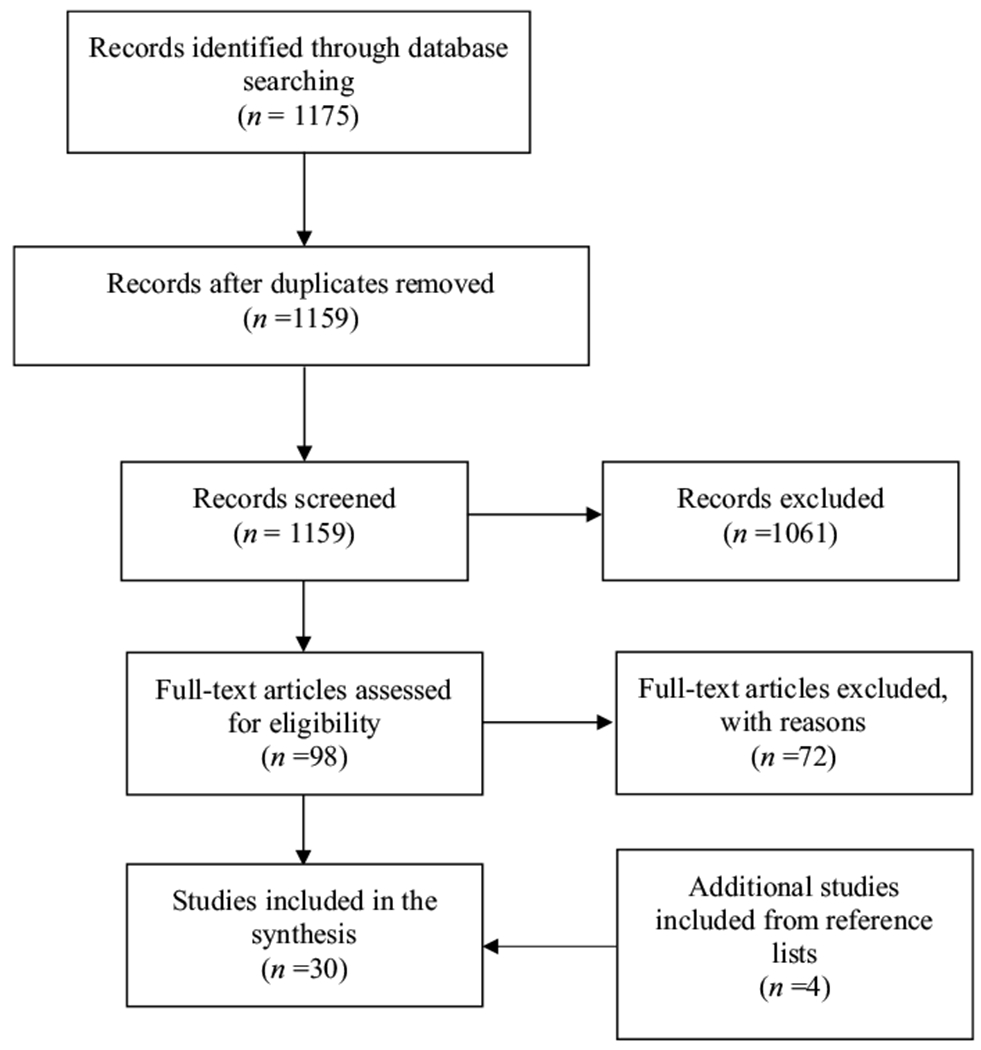

The steps of the search are depicted in the PRISMA (Moher et al. 2009) flowchart in Fig. 1. After articles were identified, the titles and abstracts were screened. A full-text screening was then conducted on articles which were identified as relevant and met inclusion criteria described below through the initial screening. To identify additional articles, we searched the reference lists of the included articles. Reference lists from previous literature reviews were also searched (Boisvert et al. 2010; Ferguson et al. 2019; Knutsen et al. 2016; Neely et al. 2017; Sutherland et al. 2018; Tomlinson et al. 2018).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart depicting the literature search process

Inclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used to identify empirical studies to be examined in this synthesis: (1) the study involved caregiver or professional training which was delivered exclusively through telehealth, (2) studies that involved child participants targeted children diagnosed with either ASD or a developmental disability, (3) the training involved teaching caregivers (e.g., parents, teachers, students, behavioral technicians) to use behavioral principles in treating problem behavior or teaching skill acquisition with individuals with ASD, a developmental disability, or confederates, (4) the study included researcher-collected direct observation data depicting assessment or intervention outcomes for child and/or caregiver participant behavior, (5) the study involved teaching behavioral procedures to caregivers who had no prior training in implementing those procedures, and (6) the study was written in English.

Across the five databases, 1159 total studies, excluding duplicates, were identified. After screening the titles and abstracts, 98 studies remained to be assessed by their full text. From the 98 studies, 26 met eligibility to be included in the review. Four additional studies were identified through search of reference lists. In total, 30 studies were included in the synthesis.

Data Extraction

For the synthesis, the 30 included studies selected were coded for the following information: (1) child participant characteristics, (2) caregiver participant characteristics, (3) research design, (4) behavioral procedures taught to caregivers to implement, (5) dependent variables involving direct observation of behavior exhibited by caregiver participants, child participants, or both, (6) participant outcomes in relation to child participant behavior, caregiver participant skills in implementing ABA-based procedures, or both, (7) whether sessions were conducted live or recorded by caregivers, (8) training components used with caregiver participants, and (9) procedural fidelity of caregiver participants. Some of the codes were similar to what was included in Ferguson et al. (2019) and Neely et al. (2017).

Inter-Rater Agreement

Search Agreement Procedures

A second reviewer used the same search terms described earlier in this paper to obtain studies from the five databases listed. The second reviewer recorded the number of studies obtained from each database. For each database, inter-rater agreement (IRA) was obtained by dividing the smaller number with the larger number and multiplying that result by 100. The average IRA across the five databases was 94.1% (range from 92.5 to 96.3%).

Inclusion Agreement Procedures

Abstracts and titles from 30% (n = 348) of the studies gathered during the initial database search were reviewed by a second reviewer. For each study, the second reviewer recorded whether the study met inclusion criteria. The final IRA was calculated by dividing the number of agreements (331) by the sum of the agreements plus disagreements (331 + 17) and multiplying that number by 100. An IRA of 95.1% was obtained. Thirty percent (n = 29) of the studies chosen for full-text review were also read by a second reviewer. For each study, the second reviewer recorded whether the study met inclusion criteria. Questions about the inclusion criteria were addressed by the first author. After clarifications were discussed, IRA was obtained by dividing the number of agreements (26) by the sum of the agreements plus disagreements (26 + 3) and multiplying that number by 100. The resulting IRA was 89.7%.

Data Extraction Agreement Procedures

Lastly, 30% (n = 9) of the studies selected for the review were read by a second reviewer to compare results coded by the primary reviewer. The second reviewer coded for the same information described earlier in this paper. In total, the 9 articles read multiplied by nine codes recorded per article resulted in 81 opportunities for agreement. An iterative process was conducted in which code definitions were reviewed in the context of several articles until an agreement on the coding definitions and scheme was reached. The second reviewer made changes to her codes on the nine articles and the primary reviewer independently recoded all included studies according to the adjusted definitions. IRA was then calculated by dividing the number of agreements (73) by the sum of the agreements plus disagreements (73 + 8) and multiplying that number by 100. An IRA of 90.1% was obtained.

Results

All information described below can be found in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Qualitative synthesis of selected studies

| Study | Participants | Research design | Behavioral procedures | Dependent variables | Outcomes | Training components and session type | Procedural fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alnemary et al. (2015) ** | Individual with a disability: one male child participated during generalization Age: 12 Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: four male teachers One confederate included Participants resided in Saudi Arabia |

Single case design: multiple baseline across teachers with an embedded multielement design | FA | Teacher behavior: percentage of correct responses | All teachers met criteria (90% or higher) on at least two conditions of the FA One teacher met mastery criteria on all conditions |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) pre-session instruction, (e) address questions, (f) training until meeting criteria, (g) additional resources, (h) booster training, (i) role-play Live sessions |

Average during FA: Teacher 1–90.5% Teacher 2–100% Teacher 3–86.75% Teacher 4–96.5% |

| Barkaia et al. (2017) | Individuals with disabilities: three male children Age: (M = 5.3) Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: three female therapists Age: (M = 27) Participants resided in the country of Georgia |

Single case design: multiple baseline across participants | Mand and echoics training | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of mands and echoics Therapist behavior: percentage of intervals of correct command sequencing and positive consequences (procedural fidelity) |

Increase in average levels of manding across two children and increase in average levels of echoics across all children following implementation of intervention Across therapists, increase in average percentage of intervals of command sequencing and positive consequences following coaching |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) pre-session instruction, (c) written instructions, (d) prompting, (e) learning checks Live sessions |

Measured percentage of intervals with correct command sequencing and positive consequences |

| Benson et al. (2018) ** | Individuals with disabilities: two male children Age: 5 and 8 Race: Caucasian Diagnosis: one with ASD; one with cerebral palsy Interventionists: parents of child participants |

Single case design: ABAB; Multielement design for the FAs |

SDA; FA; FCT | Child behavior: rates of SIB; rates of mands | Results of assessments identified attention as a reinforcer for one child and tangible as a reinforcer for the second child Across both children, rates of SIB decreased and rates of mands increased following the implementation of FCT |

Within-session instruction Live sessions |

Parent 1: Average during FA-95% Average during FCT-99% Parent 2: Average during SDA-81% Average during FA-77% Average during FCT-88% |

| Dimian et al. (2018) ** | Individuals with disabilities: two male children Age: 5.5 and 7 Race: Caucasian Diagnosis: multiple disabilities Interventionists: parents of child 1; mother of child 2 |

Single case design: multiple probe across communicative contexts with an embedded reversal; multielement design for the SDAs and FAs |

SDA; FA; paired choice preference assessment; FCT | Child behavior: Child 1- (a) percentage of intervals of reaching and pointing, (b) percentage of intervals of crying and screaming, (c) occurrences of AAC symbol activation Child 2-occurences of AAC symbol activation |

Child 1: Assessment indicated an escape function Overall increase in AAC symbol activation and decrease in tantrum and reaching/pointing behavior following implementation of FCT Child 2: Increase in AAC symbol activation following implementation of FCT |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) written instructions Live sessions |

Average during FCT: 92% and 96% |

| Fischer et al. (2017) ** | Individuals with disabilities: three children: one male; one female; one unknown Race: one Caucasian; one African American; one unknown Diagnosis: one had ADHD medication; one with ASD; one unknown Interventionists: three female teachers Race: Caucasian |

Single case design: multiple baseline across teacher-student dyads | Dyad 1: differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) and the GBG Dyad 2: DRA Dyad 3: differential reinforcement of the omission of behavior (DRO) |

Child behavior: percent occurrences of engagement; percent occurrences of problem behavior Teacher behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures |

Across teachers, increase in procedural fidelity following consultations Child 1: increase in engagement following implementation of the GBG Child 2: increase in engagement following implementation of DRA Child 3: decrease in problem behavior following implementation of DRO |

(a) Within-session instruction, (b) modeling, (c) address questions, (d) Motiv Aiders used for prompting, (e) review of data Live sessions |

Average during DRO: 90% Average during DRA: 97% across 2 participants Average during GBG: 76% |

| Fisher et al. (2014) ** | Interventionists: one male and seven female behavioral technicians Age: range from 21 to over 50 Study included confederates instead of child participants |

Group design: randomized clinical trial with waitlist control | Discrete-trial and play-based procedures | Technician behavior: procedural fidelity scores on the Behavioral Implementation of Skills for Work Activities (BISWA) and the Behavior Implementation of Skills for Play Activities (BISPA) | All technicians improved in procedural fidelity scores on the post-test Large and statistically significant mean difference between treatment and control group scores on BISPA and BISWA posttest |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) caregiver assessment, (e) online instruction, (f) training until meeting criteria, (g) learning checks, (h) practice exercises, (i) caregiver goal-setting Live sessions |

Experimental group average: BISWA-97.5% BISPA-88.5% |

| Gibson et al. (2010) ** | Individual with a disability: one male Age: 4 Diagnosis: ASD Interventionist: one female teacher and one teaching assistant |

Single case design: ABAB | FCT | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of elopement | Decrease in elopement following implementation of FCT | (a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) address questions, (e) written instructions, (f) training until meeting criteria, (g) collaborative problem solving, (h) role-play Live sessions |

Average during FCT: 100% during baseline and 90% during intervention |

| Hay-Hansson et al. (2013) | Individuals with disabilities: six children Age: (M = 9.3) Diagnosis: ASD and/or moderate developmental disability Interventionists: three male and 13 female school staff Age: (M = 42.5) |

Group design: randomized clinical trial with random assignment to an intervention | DTT | Staff behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures according to scores on the Evaluation of Therapeutic Effectiveness (ETE) | No significant differences in ETE scores at posttest between groups who received in-person or remote training Overall, both groups significantly improved in ETE scores from pre-test to posttest |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) pre-session instruction, (e) caregiver assessment, (f) prompting, (g) practice exercises Live sessions |

Measured percentage of intervals with correct implementation of procedures |

| Heitzman-Powell et al. (2014) | Interventionists: seven parents Age: (M = 37.3) | Group design: quasi-experimental with pre- and posttest and no control group | ABA-based teaching procedures | Parent behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures | Across parents, increase in implementation of procedures from pre- to posttest | (a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) pre-session instruction, (d) address questions, (e) caregiver assessment, (f) prompting, (g) online instruction, (h) written manual/handouts, (i) training until meeting criteria, (j) collaborative problem solving, (k) learning checks, (l) caregiver reflections, (m) practice exercises, (n) performance feedback on learning checks Live sessions |

Average posttest performance across participants and skills: 71.8% |

| Higgins et al. (2017) ** | Individuals with disabilities: one female and two male children Age: (M = 4.7) Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: three female behavioral technicians Age: (M = 22.7) |

Single case design: multiple baseline across participants | Multiple stimulus without replacement (MSWO) preference assessment | Technician behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures | Across technicians, increase in performance levels following implementation of training | (a) Performance feedback, (b) modeling, (c) pre-session instruction, (d) written instructions, (e) caregiver assessment, (f) prompting, (g) online instruction, (h) training until meeting criteria, (i) booster training, (j) role-play, (k) video self-modeling, Live sessions |

Technician 1 and 2: 100% with confederate and child during post-training assessment Technician 3: 100% with confederate and 77.8% with child during post-training assessment; 92.3% after tailored training |

| Ingersoll et al. (2016) | Individuals with disabilities: 19 male and eight female children Age: (M = 3.6) Race: 23 Caucasian; four minorities Diagnosis: ASD or PDD-NOS Interventionists: 26 mothers and one father of the child participants |

Group design: randomized clinical trial with random assignment to an intervention | Naturalistic teaching strategies | Child behavior: rates of use of language targets Parent behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures |

Children in both groups exhibited significantly higher use of language targets during posttest, with the therapist-assisted group scoring slightly higher Parents in both groups exhibited significantly higher procedural fidelity during posttest, with the therapist-assisted group scoring significantly higher |

Self-directed group: (a) modeling, (b) address questions, (c) written instructions, (d) caregiver assessment, (e) online instruction, (f) written manual/handouts, (g) learning checks, (h) caregiver reflections, (i) practice outside of sessions, (j) additional resources, (k) homework assignments Additions to therapist-assisted group: (a) performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) pre-session instruction Live sessions |

Within 80-89% for both groups |

| Knowles et al. (2017) | Individuals with disabilities: four male children Age: 8-9 years Race: two African American; one Latino; one Pacific Islander Disability: two with EBD; two with OHI Interventionist: one female teacher Age: 23 Race: Caucasian |

Single case design: multiple baseline across behaviors with four phases according to the behavioral procedures | ABA-based teaching procedures (praise, prompting, precorrection, and opportunities to respond (OTR)) | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of problem behavior Teacher behavior: percentage of intervals of using procedures |

Across children, decrease in problem behavior following implementation of training during phase one; continued to stay low across phases Average increase in teacher implementation of all procedures following implementation of training |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) address questions, (e) online instruction, (f) review of data, (g) video self-modeling Live sessions |

Measured percentage of intervals with praise, antecedent strategies, and opportunities to respond (OTR) |

| Machalicek et al. (2016) ** | Individuals with disabilities: one male and two female children Age: (M = 11) Race: Caucasian Diagnosis: Child 1 and 3- ASD Child 2- multiple disabilities Interventionists: one father and two mothers of the child participants Race: same as children |

Single case design: AB and multielement for treatment effects and comparisons; multielement design for the FAs | FA; FCT; DRA; differential negative reinforcement of alternative behavior (DNRA); antecedent-based strategies |

Child behavior: percentage of intervals of problem behavior | Function of problem behavior identified as escape for child 1, tangible for child 2, and escape and tangible for child 3 Across children and interventions, decrease in problem behavior following implementation of intervention Child 1: problem behavior occurred the least during DNRA Child 2 and 3: problem behavior was indiscriminately low across conditions |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) pre-session instruction, (e) address questions, (f) written instructions, (g) prompting, (h) written manual/handouts, (i) training until meeting criteria, (j) collaborative problem solving, (k) practice exercises, (l) review of data, (m) graphing sessions Live sessions |

Average during FA: Parent 1 and 2–85% Parent 3–95% Average across intervention procedures: Parent 1–89% Parent 2–74% Parent 3–93% |

| Machalicek et al. (2009a) | Individuals with disabilities: two female children Age: 11 and 7 Race: one Hispanic; one Caucasian Diagnosis: moderate intellectual disability Interventionists: two graduate students |

Single case design: multielement | FA | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of problem behavior | Function of problem behavior identified as attention and escape for both children | (a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) written instructions Live sessions |

Not provided |

| Machalicek et al. (2009b) ** | Individuals with disabilities: three male children Age: (M = 4.7) Race: two Caucasian; one Asian American Diagnosis: two with ASD; one with pervasive developmental disorder and speech delay Interventionists: three graduate students |

No experimental design included | Paired choice preference assessment | Child behavior: number of choices Graduate student behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures |

Across children, preferences were able to be identified All graduate students implemented the assessment with 100% fidelity |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) written instructions, (d) practice outside of sessions Live sessions |

100% across graduate students |

| Machalicek et al. (2010) ** | Individuals with disabilities: six children Age: (M = 6) Race: five Caucasian; one Asian American Diagnosis: five with ASD; one with language delays Interventionists: six female teachers Age: (M = 27) Race: five Caucasian; one Chinse and Polish |

Single case design: multiple baseline across participants with an embedded multielement design for the FAs | FA | Teacher behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures | Across teachers, increase in ability to conduct an FA following implementation of training Some improvement during baseline observed |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) written instructions, (e) training until meeting criteria, (f) additional resources, (g) booster training Live sessions |

Average across teachers: 97% |

| Martens et al. (2019) ** | Individuals with disabilities: four male children Age: (M = 6.5) Race: Caucasian Diagnosis: Child 1, 3 and 4- ASD Child 1-Lissencephaly Child 2- Rett syndrome Interventionists: parents of child participants |

Single case design: multielement design for the FAs | SDA; FA | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of problem behavior | Function of problem behavior identified as escape for child 1 and tangible for child 4 A possible tangible and escape function identified for child 2 A tangible function with a possible escape function identified for child 3 Less differentiated results were obtained from the SDA |

(a) Within-session instruction, (b) prompting Live sessions |

Average during SDA: Parent 1 and 2–100% Parent 3–80% Parent 4–92% Average during FA: Parent 1–98% Parent 2–99% Parent 3 and 4–94% |

| Meadan et al. (2016) | Individuals with disabilities: one female and two male children Age: (M = 3) Race: two Caucasian; one Middle Eastern Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: three mothers of child participants Race: same as child participants |

Single case design: multiple baseline across strategies | Naturalistic teaching strategies (modeling, mand-model, time delay, and environmental arrangement) | Child behavior: occurrences of social communication initiations; percentage of opportunities with social communication responses Parent behavior: quality and rate in implementing strategies |

Across children, increase in responses and initiations following implementation of strategies Across parents, increase in rate and quality in implementation of strategies following coaching |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) pre-session instruction, (e) address questions, (f) caregiver assessment, (g) written manual/handouts, (h) training until meeting criteria, (i) collaborative problem solving, (j) caregiver reflections, (k) video self-modeling Live sessions |

Multiplied a quality rating by the rate of strategy implementation |

| Schieltz et al. (2018) ** | Individuals with disabilities: one male and one female child Age: 2 and 6 Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: two mothers of child participants |

Single case design: multiple baseline across participants; multielement design for the FAs | FA; FCT | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of problem behavior; percentage of intervals of mands; percentage of intervals of task completion | Function of problem behavior identified as tangible for one child and tangible and escape for the second child Across children, levels of problem behavior remained variable Manding and task completion increased for one child and was variable for the second child following implementation of FCT |

(a) Within-session instruction, (b) collaborative problem solving Live sessions |

Average during FCT: Parent 1–96% Parent 2–45% |

| Simacek et al. (2017) ** | Individuals with disabilities: three female children Age: (M = 3.7) Diagnosis: two with ASD; one with Rett syndrome Interventionists: parents of child participants |

Single case design: adapted multiple probe design across contexts; ABAB design in the first tier; multielement design during the SDAs and FAs |

SDA; FA; FCT Most-to-least prompting with time delay |

Child behavior: occurrences of AAC requests occurrences of idiosyncratic behavior | Function of problem behavior identified as escape for one child and escape and tangible for another child One child exhibited idiosyncratic behavior across contexts during the SDA Across children and tiers, increased levels of AAC requests and decreased levels of idiosyncratic behavior following implementation of FCT |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) written instructions Live sessions |

Average during FCT: Parent 1–96% Parent 2–93% Parent 3–94% |

| Suess et al. (2014) ** | Individuals with disabilities: three male children Age: (M = 2.9) Diagnosis: PDD-NOS Interventionists: parents of child participants Age: (M = 37) |

Single case design: multielement design with alternations between coached trials (A) and independent trials (B); multielement design for the FAs | FA; FCT | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of problem behavior; percentage of task completion; percentage of opportunities with manding Parent behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures during FCT |

Function of problem behavior identified as both escape and tangible for all children Across two children, problem behavior was more likely to occur during coaching sessions No consistent differences in levels of manding and task completion across session types For two parents, procedural fidelity was slightly higher during coaching trials versus independent trials |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) pre-session instruction, (d) prompting, (e) written manual/handouts, (f) practice outside of sessions, (g) review of data Live sessions and recorded sessions submitted by the participants |

During FCT independent trials: Parent 1–74% Parent 2–87.3% Parent 3–78.1% During FCT coached trials: Parent 1–76.8% Parent 2–94.1% Parent 3–77.6% |

| Suess et al. (2016) | Individuals with disabilities: three male and two female children Age: (M = 4.9) Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: parents of child participants |

Single case design: multiple baseline design across participants; multielement design for the FAs | FA; FCT | Child behavior: rates of problem behavior; percentage of task completion; percentage of manding | Function of problem behavior identified as escape for three children and escape and tangible for one child One child had inconclusive results Across children, problem behavior decreased and levels of manding and task completion increased following implementation of FCT |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) pre-session instruction (d) written instructions, (e) prompting, (f) caregiver reflections, (g) practice outside of sessions, (h) review of data, (i) homework assignments Live sessions |

Not provided |

| Sump et al. (2018) ** | Interventionists: two male and five female undergraduate students Age: (M = 23) Study used adult confederates instead of children |

Single case design: multiple baseline across skills; alternating treatments design used to compare training modalities | Antecedent instructional strategies; MSWO preference assessment; consequence-based strategies |

Student behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures | Across students, increase in skills following implementation of training Training was equally effective via telehealth as in person |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) modeling, (c) pre-session instruction, (d) prompting, (e) training until meeting criteria, (f) booster training, (g) role-play Live sessions |

Average across participants and skills: > 90% |

| Vismara et al. (2018) | Individuals with disabilities: 17 male and seven female children Age: (M = 2.4) Race: four Hispanic; 20 non-Hispanic Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: five fathers and 19 mothers of child participants |

Group design: randomized clinical trial with random assignment to an intervention | P-ESDM (parent model) | Child behavior: rates of imitation; rates of spontaneous communication; rates of joint attention behavior Parent behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures |

Overall, children in both groups exhibited increased rates of imitation, with higher levels in the P-ESDM group No significant differences in rates of spontaneous communication and joint attention behavior across groups Following coaching, procedural fidelity increased in both groups, with statistically significantly higher fidelity in the P-ESDM group |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) pre-session instruction, (e) caregiver assessment, (f) online instruction, (g) collaborative problem solving, (h) learning checks, (i) caregiver reflections, (j) additional resources, (k) caregiver goal-setting Live sessions |

Used a rating scale In the ESDM group, five parents scored a 4 or above during the post-test In the comparison group, two parents scored a 4 or above during the post-test |

| Vismara et al. (2013) | Individuals with disabilities: eight children Age: (M = 2.3) Race: six Caucasian; one Latino; one Hispanic Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: one father and seven mothers of child participants Race: same as child participants |

Single case design: multiple baseline across participants | P-ESDM (parent-model) | Child behavior: rates of functional vocalizations; rates of joint attention initiations Parent behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures; levels of parent engagement |

Across children, average rate of vocalizations increased while rate of joint attention initiations remained the same following implementation of ESDM Across parents, increase in procedural fidelity following coaching Across parents, increase in level of engagement following ESDM implementation |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) modeling, (c) pre-session instruction, (d) caregiver assessment, (e) online instruction, (f) written manual/handouts, (g) collaborative problem solving, (h) learning checks, (i) caregiver reflections, (j) practice outside of sessions, (k) additional resources, (l) practice exercises Live sessions |

Used a rating scale Average rating across participants during intervention: 3.68 |

| Vismara et al. (2012) | Individuals with disabilities: one female and eight male children Age: (M = 2.3) Diagnosis: six with ASD; three with PDD-NOS Interventionists: nine parents of child participants Race: eight Caucasian; one Hispanic |

Single case design: multiple baseline across participants | ESDM | Child behavior: rates of spontaneous vocalizations and imitation Parent behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures Levels of parent–child interaction |

Across children, statistically significant overall increase in spontaneous vocalizations and imitation following ESDM implementation Across parents, statistically significant higher procedural fidelity levels following implementation of coaching Across parent–child dyads, increase in level of interactions following ESDM implementation |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) address questions, (e) caregiver assessment, (f) online instruction, (g) collaborative problem solving, (h) learning checks, (i) caregiver reflections, (j) practice outside of sessions, (k) additional resources, (l) practice exercises, (m) booster training Live sessions |

Used a rating scale Average rating across participants during follow-up: 4.29 |

| Wacker et al. (2013a) ** | Individuals with disabilities: 20 children Age: (M = 4.4) Diagnosis: 13 with PDD-NOS; seven with ASD Interventionists: one father and 19 mothers of child participants Age: (M = 34) |

Single case design: multielement design | FA | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of problem behavior | Function of problem behavior identified as escape and tangible for 13 children, escape for two children, and tangible for three children For two children, function was not identified |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) pre-session instruction, (d) address questions, (e) prompting, (f) written manual/handouts, (g) review of data Live sessions |

Average across parents: 96% without corrections; 97% with corrections |

| Wacker et al. (2013b) | Individuals with disabilities: one female and 16 male children Age: (M = 4.3) Diagnosis: seven with ASD; 10 with PDD-NOS Interventionists: 16 mothers and two fathers of child participants Age: (M = 33) |

Singe case design: multiple baseline across participants | FCT | Child behavior: percentage of intervals of problem behavior | Across children, decrease in problem behavior following implementation of FCT | (a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) modeling, (d) pre-session instruction, (e) address questions, (f) written instructions, (g) written manual/handouts, (h) practice outside of sessions Live sessions |

Not provided |

| Wainer and Ingersoll (2015) | Individuals with disabilities: five children Age: (M = 3.5) Race: one Caucasian; two Asian; one Hispanic; one multi-racial Diagnosis: ASD Interventionists: five parents of child participants Race: same as child participants All participants resided in Canada |

Single case design: multiple baseline across participants | Reciprocal imitation training (RIT) (contingent imitation, linguistic mapping, modeling, prompting, reinforcement, pacing, and child spontaneous imitation) | Child behavior: rates of spontaneous imitation Parent behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures |

During self-directed condition, child 1, 2, and 3 exhibited an increase in imitation During coaching condition, child 1, 2, and 4 exhibited an increase in imitation During self-directed condition, parent 1, 3, 4, and 5 achieved moderate to high levels of fidelity During coaching condition, parent 1, 2 and 3 exhibited increased levels of fidelity |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) modeling, (c) address questions, (d) caregiver assessment, (e) online instruction, (f) written manual/handouts, (g) collaborative problem solving, (h) learning checks, (i) caregiver reflections, (j) additional resources (k) practice exercises, (l) homework assignments, (m) performance feedback on learning checks, (n) summary of content Live sessions Recorded sessions submitted by one parent |

Used a rating scale |

| Wilczynski et al. (2017) ** | Individual with a disability: one male child Age: 5 Diagnosis: ASD Interventionist: one female teacher |

No experimental design: case study | Naturalistic teaching strategies | Child behavior: percentage of compliance Teacher behavior: procedural fidelity of procedures |

Child initiation of compliance increased during teacher’s use of naturalistic teaching strategies. Completion of compliance remained the same (100%) Teacher implemented four out of seven strategies with higher fidelity during the post-training than during pretraining Fidelity on two of the strategies stayed the same (100%) and fidelity decreased for one strategy |

(a) Performance feedback, (b) within-session instruction, (c) address questions, (d) caregiver assessment, (e) online instruction, (f) learning checks, (g) video self-modeling Recorded sessions submitted by the participant followed by coaching and feedback sessions with a behavior analyst |

Average across skills: 95% |

Double asterisks next to author names indicate studies that reported procedural fidelity in the form of a percentage of steps completed accurately and of at least 90% for at least one caregiver participant

Participant Characteristics

In total, across the 30 reviewed studies, 27 included children with disabilities as participants with a total of 157 child participants across the studies. Out of the 27 studies, 22 (81.5%) reported the gender of the child participants. There were 94 males and 30 females. Twenty-six (96.3%) studies reported ages of the child participants, which ranged from 1 to 16 years. Twenty-five (92.6%) studies provided either the exact age or the mean age of child participants, with the mean age across those studies being 5.4 years. One study reported the age range of four children as being within eight to nine years. Fourteen studies (51.9%) reported race/ethnicity of the child participants. Across these studies, 52 children were Caucasian, 20 non-Hispanic, seven Hispanic, four Asian American, three African American, two Latino, one Pacific Islander, one Middle Eastern, and one multi-racial. Four participants were described as being minorities. Of the 157 child participants, 87 (55.4%) were diagnosed with ASD. Twenty-seven participants (17.2%) were described as having ASD or a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD-NOS), six (3.8%) with either ASD and/or a moderate developmental disability, and one with ASD and Lissencephaly. Twenty-three percent (n = 36) were identified as having other disabilities, such as PPD-NOS, Rett syndrome, and emotional behavioral disorder (EBD). One participant was described as being prescribed with ADHD medication.

In total, at least 191 caregiver participants, who served as interventionists, were included across the 30 reviewed studies. The term “at least” is used because some studies did not include a specified number of caregivers who participated in the studies. Of the 30 studies, 20 (66.7%) reported the gender of the caregivers. There were 20 males and 125 female caregivers. Of the 191 caregiver participants, at least 132 (69.1%) were parents, 16 (8.4%) were school staff, 16 were teachers, 11 (5.8%) were behavioral technicians, seven (3.7%) were undergraduate students, five (2.6%) were graduate students, three (1.6%) were therapists, and one was a teacher assistant. Ten (33.3%) of the 30 studies reported ages of the caregivers. The average age of caregiver participants was 30 years, excluding one study that reported the age range of seven caregivers as being from 21 to over 50 years. Eight studies (26.7%) reported the race/ethnicity of caregiver participants. Twenty-nine caregivers were Caucasian, three Hispanic, two Asian American, two multi-racial, one Middle Eastern, and one Latino. One study indicated that all participants were from Saudi Arabia (Alnemary et al. 2015) and another indicated that all participants were from the country of Georgia (Barkaia et al. 2017).

Study Design

Across the 30 studies, 23 (76.7%) used a single-case experimental design, five (16.7%) used a group experimental design, and two did not use an experimental design. Of the studies using single case design, 12 used a multiple baseline or multiple probe design, four used a multielement design, two used an ABAB design, two used a multiple baseline with an embedded multielement design, one used a multiple baseline with an alternating treatments design, one used a multiple probe design with an embedded reversal, and one used an AB with a multielement design. Seven studies used an additional multielement design to present structured descriptive assessment (SDA) and/or functional analysis (FA) data. Of the studies using a group experimental design, three conducted a randomized clinical trial involving random assignment to one of two intervention groups, one conducted a randomized clinical trial with a waitlist control, and one conducted a quasi-experiment with a pre- and posttest and no control group.

ABA-Based Procedures

For each reviewed study, information was gathered on the types of behavioral procedures taught to caregiver participants. The procedures taught to caregiver participants most frequently in the studies were FA (n = 12), FCT (n = 9), and a combination of ABA-based teaching strategies (n = 6). Other procedures included preference assessments (n = 4), SDAs (n = 4), the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) (n = 3), differential reinforcement procedures (n = 2), antecedent-based procedures (n = 2), discrete-trial training (DTT) (n = 1), consequence-based strategies (n = 1), mand and echoics training (n = 1), the good behavior game (GBG) (n = 1), most-to-least prompting (n = 1), and reciprocal imitation training (n = 1).

Dependent Measures

Information was also gathered on the dependent measures targeted across the reviewed studies. The focus of dependent measures for all studies was either behavior exhibited by the child participants (n = 11), behavior exhibited by the caregiver participants (n = 7), or both (n = 12). A variety of child responses were measured, with the most common being problem behavior (n = 13). Additional child responses measured that were less common included mands and/or echoics (n = 5), task completion (n = 3), imitation (n = 3), augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) requests (n = 2), idiosyncratic behavior (n = 2), joint attention (n = 2), use of language targets (n = 1), social communication initiations and responses (n = 1), functional vocalizations (n = 1), spontaneous communication (n = 1), spontaneous vocalizations (n = 1), choice making (n = 1), engagement (n = 1), and compliance (n = 1). Caregiver responses measured included the procedural fidelity with which behavioral procedures were implemented (n = 16), occurrences of the use of procedures (n = 2), and quality and rate of implementing procedures (n = 1). One study additionally measured levels of parent engagement with their child (Vismara et al. 2013) and another study additionally measured levels of parent–child interaction (Vismara et al. 2012).

Outcomes

Outcomes of the participants’ performance were recorded for all studies. In 14 studies, all child participants exhibited positive outcomes following implementation of ABA-based interventions, with the positive outcomes being a decrease in problem behavior and/or an increase in skill acquisition. Four studies had mixed results in that not all participants exhibited improved performance during intervention compared to baseline. There were no studies that involved negative outcomes for any child participants.

In 15 studies, all caregiver participants exhibited improved performance in implementing ABA-based procedures while being coached by therapists. One study had mixed results in which not all participants exhibited improved performance during intervention compared to baseline. One study reported that one caregiver exhibited a decrease in performance in one out of seven ABA-based teaching procedures during post-training. All 11 studies that involved the use of FAs to assess child participants indicated successful implementation from caregivers and identified functions for all or most child participants. One study indicated the ability of teachers to conduct a preference assessment with 100% fidelity and to identify preferences of the child participants (Machalicek et al. 2009b).

Training Components and Session Type

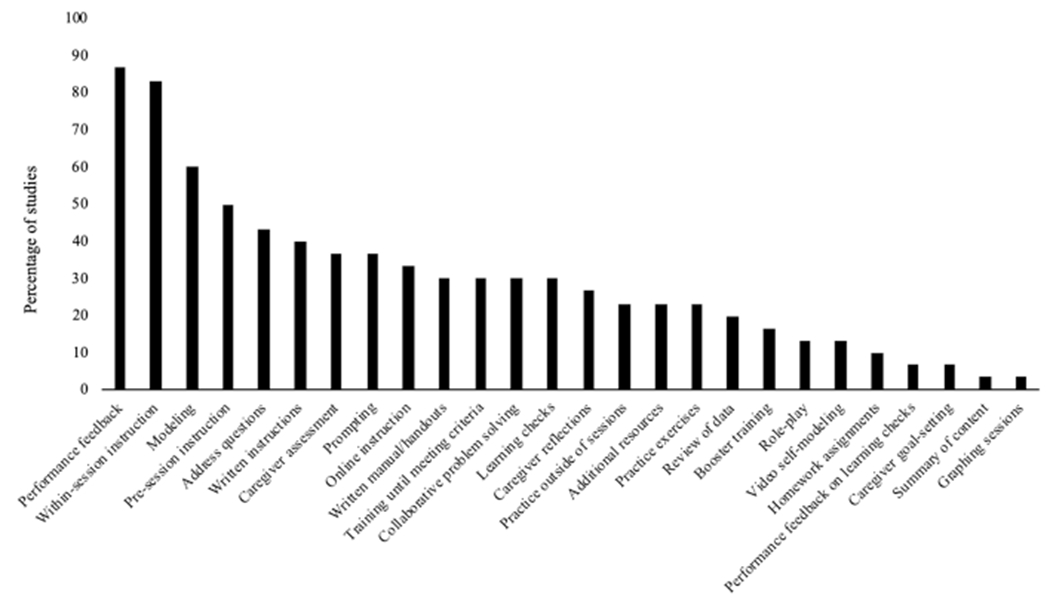

Table 2 provides a list of training components described among the included studies with each component defined. Figure 2 displays a bar graph depicting the training components reported on the x-axis and the percentage of studies that used each of the components on the y-axis. All included studies provided a description of training components used to teach caregiver participants behavioral procedures. A variety of training components were used across the studies. All studies used at least one component to teach one type of procedure, with some studies including more than one set of components for the various assessments and interventions implemented, such as FAs and FCT. For example, in a study by Simacek et al. (2017), researchers conducted within-session instruction to teach parents how to implement an SDA and FA. They also provided written instructions prior to starting FA sessions. To teach parents to conduct FCT and most-to-least prompting, researchers provided written instructions and conducted within-session instruction with modeling and performance feedback. Across studies, the most common procedures used during training were: providing performance feedback to caregivers on their implementation of procedures (n = 26), within-session instruction (n = 25), and modeling (demonstration of procedures provided by at least two therapists live or via a video model) (n = 18). Other less common components included pre-session instruction (n = 15), written instructions (n = 12), prompting (n = 11), online instruction (n = 10), collaborative problem solving (n = 9), and practice outside of sessions (n = 7). Some components found least often in the reviewed studies included a review of assessment and/or intervention data (n = 6), video self-modeling (n = 4), homework assignments (n = 3), caregiver goal-setting (n = 1), and a summary of content covered during live sessions (n = 1).

Table 2.

List of training components and definitions

| Training components | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Performance feedback | Comments provided vocally or electronically to caregiver participants on their performance in implementing behavioral procedures |

| Within-session instruction | Response-guided and individualized directions provided vocally to caregiver participants during live sessions on implementing a behavioral procedure |

| Modeling | A demonstration provided by researchers either live or via a video model to caregiver participants on how to implement behavioral procedures |

| Pre-session instruction | Vocal instruction provided to caregiver participants prior to the start of the first assessment or intervention session involving a presentation or review of content related to the study, behavioral principles, behavioral procedures, the rationale for implementing specific behavioral procedures, and/or how behavioral procedures should be used in the natural environment |

| Address questions | A researcher designates time to answer questions caregiver participants have on behavioral principles or procedures |

| Prompting | a researcher prompts caregiver participants to implement specific steps of a behavioral procedure as caregivers are implementing it with a child participant or confederate |

| Written instructions | Response-guided and individualized directions provided to caregiver participants on how to implement behavioral procedures; typically provided via an electronic document or email |

| Online instruction | Slideshows, lectures, and/or modules provided to caregiver participants in an electronic format and involves content related to behavioral principles and procedures; may include a rationale for implementing specific behavioral procedures and recommendations for how to implement procedures in the natural environment |

| Training until meeting criteria | Training or intervention continues until caregiver participants meet a certain performance criterion in implementing behavioral procedures |

| Collaborative problem solving | Discussion between a researcher and caregiver participant in which they address potential or current issues related to implementing behavioral procedures with child participants, discuss how the procedures should be used outside of live sessions, and/or develop target skills for caregiver or child participants |

| Written manual/handout | A written or typed guide provided to caregiver participants with content related to behavioral principles and/or procedures |

| Learning checks | Exercises or quizzes assessing a caregiver participant’s comprehension of behavioral principles and/or procedures; does not involve an assessment of a caregiver’s skill level in implementing behavioral procedures |

| Caregiver reflections | Report from caregiver participants describing their previous use of behavioral procedures with child participants |

| Practice outside of sessions | Caregiver participants practice implementing behavioral procedures with child participants outside of live sessions |

| Additional resources | Websites or readings researchers provided to caregiver participants on topics such as autism, behavioral principles, implementing behavioral procedures, or other related topics |

| Review of data | A researcher presents a caregiver participant with assessment or intervention data and explains the results |

| Practice exercises | A caregiver participant practices implementing behavioral procedures with a child participant or confederate during live sessions with a researcher |

| Booster training | Any repeated training provided to caregiver participants due to them not meeting a performance criterion in implementing behavioral procedures |

| Role-play | Caregiver participants either play the role of a child or interventionist to practice implementing behavioral procedures together without the presence of a child or confederate |

| Video self-modeling | Caregiver participants can observe their past performance in implementing a behavioral procedure for the purpose of learning correct/incorrect implementation of the procedures; video may include embedded performance feedback |

| Caregiver assessment | A test conducted by researchers on caregiver participant progress/current skill level in implementing a behavioral procedure |

| Homework assignments | Assignments related to behavioral principles or procedures given to caregiver participants to complete outside of live sessions |

| Performance feedback on learning checks | Comments given to caregiver participants on written exercises/quizzes they have completed assessing their understanding of ABA principles or procedures |

| Summary of content | A review provided to caregiver participants on behavioral principles or procedures used during live sessions; provided after live sessions |

| Caregiver goal-setting | Any instance in which caregiver participants set goals for themselves in learning behavioral concepts or procedures |

| Graphing sessions | Instruction provided to caregiver participants on how to graph and interpret assessment or intervention data |

Fig. 2.

Data depicting the percentage of studies (n = 30) that used the training components listed on the x-axis

Across studies, sessions in which caregiver participants implemented behavioral procedures with child participants or confederates were either recorded by the caregiver participants and sent to researchers or were directly observed live by researchers as they communicated with the caregiver participants via telehealth. In both of these circumstances, researchers recorded data on caregiver and/or child participant performance. Across the 30 studies, 27 involved live sessions, one involved live or recorded sessions for each participant, one involved both live and recorded sessions, and one involved only recorded sessions.

Procedural Fidelity of Caregiver Participants

Interventionists’ procedural fidelity was recorded for each study that provided pertinent information. Twenty-four of the 30 studies (80%) reported interventionists’ procedural fidelity in implementing behavioral procedures that researchers or therapists taught them via telehealth. Seventy-nine percent (n = 19) of studies reported procedural fidelity in the form of a percentage of steps completed accurately, 16.7% (n = 4) reported fidelity in the form of rating scale scores, and one study reported fidelity using a measure of percentage of intervals. Of the 19 studies reporting procedural fidelity in the form of a percentage of steps completed accurately, 89.5% (n = 17) reported procedural fidelity levels of 90% or higher for at least one caregiver participant (see Table 1) and 5.3% (n = 1) of the studies reported procedural fidelity levels of less than 70% for one caregiver participant.

Discussion

The purpose of the current literature review was to provide an update on the current published empirical research on the use of telehealth for providing ABA-based services to individuals with disabilities and their caregivers. The current review also sought to gather information regarding training components used by researchers via telehealth and caregivers’ procedural fidelity in implementing procedures. Overall, the current research provides support for telehealth as a service delivery mechanism for providing ABA-based services. All single-case-design studies involving intervention for child participants (53.3% of all included studies) resulted in behavior change in the desired direction for 73 child participants. All single-case-design studies involving training caregiver participants to implement intervention (40% of all included studies) resulted in behavior change in the desired direction for 55 caregiver participants. Additionally, all group-design studies resulted in behavior change in a desired direction for both child and caregiver participant groups receiving intervention. Such outcomes provide support for the use of telehealth for delivering ABA-based services.

In examining training components used across studies and reported procedural fidelity levels of caregiver participants implementing ABA-based procedures, some possible considerations are worth noting. The authors gathered data from 19 studies that included both descriptions of training components and procedural fidelity levels in the form of a percentage of correct caregiver responses. Across the 19 studies, 89.5% reported procedural fidelity levels of 90% or higher for at least one caregiver participant and only one study reported procedural fidelity levels of less than 70% for one caregiver participant. However, within and across training components, both relatively high and relatively low procedural fidelity levels were reported. No specific training component was associated with exclusively high or low procedural fidelity, suggesting that procedural fidelity is not exclusively influenced by the training component(s). To illustrate, there are examples of individual studies in which caregiver participants received the same training and yet exhibited different levels of procedural fidelity. For example, in a study by Suess et al. (2014), researchers used a package of training components, including performance feedback, pre-session instruction, within-session instruction, and practice outside of sessions. The same training components were used for all three participating caregivers and average procedural fidelity scores across caregivers were quite variable (ranging from 74 to 94.1%). Thus, it appears there are other factors that influence procedural fidelity aside from the training components.

Several possible factors may influence the level of procedural fidelity in which caregivers implement assessment or intervention procedures. For one, the procedures themselves could influence procedural fidelity, whether it be the number of steps that need to be completed or the difficulty level of the procedures. Fidelity may also be influenced by idiosyncratic caregiver factors including but not limited to educational background, experience, and competing responsibilities. Therefore, it may be beneficial for behavior analysts to consider using systematic methods to develop individualized training packages for caregivers and to make adjustments to training procedures when needed, just as they do when developing intervention packages for individuals receiving ABA-based intervention.

One interesting finding is the prevalence of children with ASD compared to children with other disabilities who participated in studies involving telehealth. Of the 157 child participants across 30 studies, just over half (55.4%) were diagnosed with ASD, whereas nearly half of child participants had other diagnoses. Such data provide some support for the use of telehealth to provide behavioral services to individuals with a variety of disabilities. It also emphasizes the importance of the current literature review in expanding the inclusion criteria in order to include individuals with disabilities other than ASD, because such studies also contribute information supporting the use of telehealth. Additionally, participants who were implementing behavioral assessments or interventions represented a diverse population, with a variety of professions and different education backgrounds, the majority of which were parents of child participants. Some studies also included participants who resided in nations outside of the USA, such as Canada, Saudi Arabia, and the country of Georgia (Alnemary et al. 2015; Barkaia et al. 2017; Wainer and Ingersoll 2015). Thus, the current telehealth literature provides emerging evidence towards the use of telehealth in providing ABA-based services to people with different backgrounds and who reside in various countries.

Limitations to the Review

The current review should be considered in light of some limitations. First, five studies that included participants who had experience using the specific behavioral procedures being taught to them were not included in the current review. Including such studies may have provided useful information about the status of telehealth as a service tool that is excluded in this review. However, such studies were not included in order to gather information on training components used for novice users of ABA-based procedures. Second, specific relations between procedural fidelity levels and training components are unknown.

Implications for Future Research

Future research on telehealth should continue to test the effectiveness of using various training components remotely for teaching caregivers to implement behavioral procedures in order to provide further evidence of the utility of telehealth as an established format for delivering ABA-based services. Additionally, researchers should use statistical methods, such as a meta-analysis, or experimental methods to determine effective and essential components in training individuals to use behavioral procedures accurately (Neely et al. 2017) or to determine other factors that may influence procedural fidelity. Future research should also test whether various training components are more effective in teaching caregivers to implement behavioral procedures designed to address problem behavior versus those focused on skill acquisition. For example, one may test the effectiveness of teaching caregivers to implement an FA compared to discrete-trial teaching using response-guided or individualized components, such as within-session instruction to coach, versus non-individualized components, such as a written manual. Overall, seeking to identify currently effective components in telehealth is an important endeavor. Taking steps to perfect the use of telehealth may allow children with disabilities and their families to receive services they would otherwise not obtain and may lead to long-term positive outcomes for those families.

Funding

This study was funded by grant number 1R21DC015021.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

*Indicates studies included in the review

- *Alnemary FM, Wallace M, Symon JBG, & Barry LM (2015). Using international videoconferencing to provide staff training on functional behavioral assessment. Behavioral Interventions, 30, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- *Barkaia A, Stokes TF, & Mikiashvili T (2017). Intercontinental telehealth coaching of therapists to improve verbalizations by children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50, 582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barretto A, Wacker DP, Harding J, Lee J, & Berg WK (2006). Using telemedicine to conduct behavioral assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39, 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Benson SS, Dimian AF, Elmquist M, Simacek J, McComas JJ, & Symons FJ (2018). Coaching parents to assess and treat self-injurious behaviour via telehealth. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62, 1114–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert M, Lang R, Andrianopoulos M, & Boscardin M-L (2010). Telepractice in the assessment and treatment of individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13, 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgren JA (2002). The educational context and outcomes for high school students with disabilities: The perceptions of parents of students with disabilities. Research Report. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED469288.pdf.

- *Dimian AF, Elmquist M, Reichle J, & Simacek J (2018). Teaching communicative responses with a speech-generating device via telehealth coaching. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2, 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson J, Craig EA, & Dounavi K (2019). Telehealth as a model for providing behaviour analytic interventions to individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 582–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Fischer AJ, Dart EH, Radley KC, Richardson D, Clark R, & Wimberly J (2017). An evaluation of the effectiveness and acceptability of teleconsultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 27, 437–458. [Google Scholar]

- *Fisher WW, Luczynski KC, Hood SA, Lesser AD, Machado MA, & Piazza CC (2014). Preliminary findings of a randomized clinical trial of a virtual training program for applied behavior analysis technicians. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar]

- *Gibson JL, Pennington RC, Stenhoff DM, & Hopper JS (2010). Using desktop videoconferencing to deliver interventions to a preschool student with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 29, 214–225. [Google Scholar]

- *Hay-Hansson AW, & Eldevik S (2013). Training discrete trials teaching skills using videoconference. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar]

- *Heitzman-Powell LS, Buzhardt J, Rusinko LC, & Miller TM (2014). Formative evaluation of an ABA outreach training program for parents of children with autism in remote areas. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- *Higgins WJ, Luczynski KC, Carroll RA, Fisher WW, & Mudford OC (2017). Evaluation of a telehealth training package to remotely train staff to conduct a preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50, 238–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ingersoll B, Wainer AL, Berger NI, Pickard KE, & Bonter N (2016). Comparison of a self-directed and therapist-assisted telehealth parent mediated intervention for children with ASD: A pilot RCT. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 2275–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Knowles C, Massar M, Raulston T-J, & Machalicek W (2017). Telehealth consultation in a self-contained classroom for behavior: A pilot study. Preventing School Failure, 61, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen J, Wolfe A, Burke BL, Hepburn S, Lindgren S, & Coury D (2016). A systematic review of telemedicine in autism spectrum disorders. Review Journal of Autism And Developmental Disorders, 3, 330–344. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren S, Wacker DP, Suess A, Schieltz K, Pelzel K, Kopelman T, et al. (2016). Telehealth and autism: Treating challenging behavior at a lower cost. Pediatrics, 137(2), 167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Machalicek W, Lequia J, Pinkelman S, Knowles C, Raulston T, Davis T, et al. (2016). Behavioral telehealth consultation with families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Behavioral Interventions, 31, 223–250. [Google Scholar]

- *Machalicek W, O’Reilly M, Chan JM, Lang R, Mandy R, Tonya D, et al. (2009a). Using videoconferencing to conduct functional analysis of challenging behavior and develop classroom behavioral support plans for students with autism. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44(207), 217. [Google Scholar]

- *Machalicek W, O’Reilly M, Chan JM, Rispoli M, Lang R, Davis T, et al. (2009b). Using videoconferencing to support teachers to conduct preference assessments with students with autism and developmental disabilities. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- *Machalicek W, O’Reilly MF, Rispoli M, Davis T, Lang R, Franco JH, et al. (2010). Training teachers to assess the challenging behaviors of students with autism using video teleconferencing. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45, 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- *Martens BK, Baxter EL, McComas JJ, Sallade SJ, Kester JS, Caamano M, Dimian A, Simacek J, & Pennington B (2019). Agreement between structured descriptive assessments and functional analyses conducted over a telehealth system. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 19, 343–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Meadan H, Snodgrass MR, Meyer LE, Fisher KW, Chung MY, & Halle JW (2016). Internet-based parent-implemented intervention for young children with autism: A pilot study. Journal of Early Intervention, 38, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6, e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MA, & Ruble LA (2012). A comparative study of rurality and urbanicity on access to and satisfaction with services for children with autism spectrum disorders. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 31(3), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Neely L, Rispoli M, Gerow S, Hong ER, & Hagan-Burke S (2017). Fidelity outcomes for autism-focused interventionists coached via telepractice: A systematic literature review. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities, 29, 849–874. 10.1007/s10882-017-9550-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]