Abstract

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is a prevalent inflammatory disorder of the ocular surface that significantly impacts patients’ vision and quality of life. The underlying mechanism of aging and MGD remains largely uncharacterized. The aim of this work is to investigate lipid metabolic alterations in age-related MGD (ARMGD) through integrated proteomics, lipidomics and machine learning (ML) approach. For this purpose, we collected samples of female mouse meibomian glands (MGs) dissected from eyelids at age two months (n = 9) and two years (n = 9) for proteomic and lipidomic profilings using the liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method. To further identify ARMGD-related lipid biomarkers, ML model was established using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) algorithm. For proteomic profiling, 375 differentially expressed proteins were detected. Functional analyses indicated the leading role of cholesterol biosynthesis in the aging process of MGs. Several proteins were proposed as potential biomarkers, including lanosterol synthase (Lss), 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase (Dhcr24), and farnesyl diphosphate farnesyl transferase 1 (Fdft1). Concomitantly, lipidomic analysis unveiled 47 lipid species that were differentially expressed and clustered into four classes. The most notable age-related alterations involved a decline in cholesteryl esters (ChE) levels and an increase in triradylglycerols (TG) levels, accompanied by significant differences in their lipid unsaturation patterns. Through ML construction, it was confirmed that ChE(26:0), ChE(26:1), and ChE(30:1) represent the most promising diagnostic molecules. The present study identified essential proteins, lipids, and signaling pathways in age-related MGD (ARMGD), providing a reference landscape to facilitate novel strategies for the disease transformation.

Keywords: Multi-omics, Machine learning, Meibomian gland dysfunction, Aging, Lipids, Cholesteryl esters, Therapy

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Meibomian glands (MGs) are holocrine sebaceous glands situated within the eyelids that function to produce meibum, which constitutes the lipid layer of the tear film [1], [2]. Dysfunction of MGs, also known as meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), is a common ocular disorder that impairs the vision and quality of life for affected individuals [3]. Symptoms related to MGD, such as eye irritation and tear film disruption, can be attributed to obstructed or inflamed MG orifices, resulting in a gradual deterioration of the overall health of the ocular surface [4]. Current estimates suggest that the prevalence of MGD in the United States population is 39–50 %, with a significant socioeconomic burden [5], [6]. It is considered to be the primary cause of evaporative dry eye and up to 86 % of dry eye patients demonstrated signs of MGD [5], [6], [7]. To date, there is no curative treatment for MGD, and current therapeutic strategies are largely palliative, relying on topical administration of anti-microbial/anti-inflammatory drugs, warm compresses, and thermal pulsation to restore MGs secretions by removing obstructions [8]. Standing on a clinical perspective, a deeper understanding of the biological molecules and processes that initiate MGD is urgently required to develop more effective and comprehensive treatment strategies.

Extensive research has established a robust correlation between the process of aging and the onset of MGD in both human and animal models [9]. Despite numerous investigations indicating that aging can bring physiological and morphological changes within eyelid, there is no definitive understanding regarding the molecular regulators and signaling pathways implicated in the associated metabolic process [10]. Recent studies have indicated that certain age-related alterations in lipid content and enzyme activities played a vital role in the development of MGD. Using infrared spectrometry (IR) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), some researchers demonstrated certain differences in eyelid lipid contents in an age-dependent manner, such as the overall lipid length and degree of unsaturation [11], [12]. Notably, a recent lipidomic study suggested extremely high similarities of meibum lipids between young and aged participants, which may suggest the absence of specific metabolic differences [13]. However, due to its complex nature, the underlying biochemical mechanism of lipid metabolism remains to be elucidated. Investigation into the intricate lipid metabolic activities in age-related MGD (ARMGD) is of great significance in terms of disease comprehension and the development of innovative targeted therapeutics.

The field of biomarker researches has been expanding rapidly, and the omics approach is a relatively new realm of study providing an elaborate metabolic map based on high-throughput methods [14]. Lipidomic analysis in biological tissues has enabled comprehensive researches in lipids, offering specific diagnostic and therapeutic value in many diseases. Similarly, proteomic profiling is widely applied to identify disease biomarkers and investigate the potential signaling pathways and complex protein networks for disease interpretation. Recently, machine learning (ML) has been extensively applied in medical fields to aid in the detection of disease targets and facilitate computer-aided diagnosis [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. ML-based prediction models have been established to assist decision-making and uncover biomarkers of various ocular diseases, including myopia, glaucoma, and dry eye disease [20], [21], [22]. Nevertheless, the construction of ML models for MGD remains insufficient, and relevant research efforts are urgently needed.

The present study was designed to comprehensively investigate age-related lipid metabolic alterations in MGD, with a focus on identifying potential targets for therapy. For our purposes, untargeted LC-MS/MS proteomic and lipidomic analyses were conducted on meibum samples from young and aged mice. The significantly regulated proteins were determined by proteomics, followed by Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses to identify significantly enriched signaling pathways. Meanwhile, an absolute lipids quantification at both species and class level were obtained and differentially abundant lipids were identified. Through ML construction, a nine-lipid diagnostic signature was established. Combining the multi-omics and ML results, we formulated the hypothesis that certain age-related changes in lipid molecules, such as cholesterol esters (ChE) of 26:0, 26:1, and 30:1, and metabolic mediators, such as Dhcr24, Lss, and Fdft1, which are involved in cholesterol biosynthetic pathways, may contribute to the development of MGD. This study provides the theoretical foundation for the identification of potential biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of ARMGD. The established multi-omics and ML workflow was demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design and workflow. Two-month (n = 9) and two-year-old (n = 9) female mouse meibomian glands (MGs) were dissected for proteomic and lipidomic profiling, followed by systematic bioinformatics analyses. Subsequent machine learning (ML) model was constructed for lipid biomarker identification and a hypothesis was proposed for the potential proteins and lipids network underlying age-related meibomian gland dysfunction (ARMGD).

2. Methods

2.1. Reagents

MS-grade acetonitrile, MS-grade methanol, and HPLC-grade 2-propanol were purchased from Thermo Fisher. HPLC-grade ammonium, HPLC-grade formate Isopropanol, and HPLC-grade formic acid were purchased from Sigma. Additional reagents information can be found in supplementary materials (Table S1).

2.2. Mouse eyelid dissection

Two-month (n = 9) and two-year-old (n = 9) female C57/BL6J mice were purchased from the Shanghai Animal Experimental Center and fed with normal chow diet under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Both upper and lower tarsal plates were dissected from bilateral sides after sacrifice. For our studies, twelve mice were used for lipidomics and six for proteomics, equally split between the two age groups. The rest samples were fixed with 4 % PFA and stored at 4 °C for histological evaluation. All animal experiments obtained approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and performed under the Statement of the Association of Vision and Ophthalmology Annual (ARVO) for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

2.3. Mouse clinical examinations and histological staining

A slit-lamp microscope was used to image mouse eyelid margins and corneas under a single ophthalmologist. The grade of corneal damage, which indicates the level of MGD, was evaluated on previously reported criteria. Corneal opacity tests were performed according to the Draize method by multiplying the degree and area of corneal opacity [23]. For corneal fluorescein test, 1 µL of 1 % fluorescein sodium solution was instilled into the conjunctival sac and washed with 0.9 % NaCl, and the fluorescein staining was recorded 60 s later with a cobalt blue filter under the slit-lamp microscope. The fluorescein intensity was graded as follows: 0 for no staining, 0.5 for slightly punctated staining, 1 for diffuse punctated staining, 2 for diffuse staining covering less than 1/3 of the cornea, 3 for diffuse staining covering more than 1/3 of the cornea, and 4 for staining covering more than 2/3 of the cornea [24].

Mouse eyelid tissues from different age groups were embedded in paraffin and tissue freezing medium before cutting into 6-μm-thick sagittal sections. For Oil Red O (ORO) staining, frozen sections were first fixed in 4 % PFA for 15 min and rinsed twice in PBS, and then stained in freshly prepared ORO solution for 10–15 min. Finally, the slides were incubated in hematoxylin for 2 min and coverslipped with an aqueous mounting medium.

2.4. Lipidomics sample preparation

Lipid extraction was performed using the MTBE method. In Brief, MGs tissues were spiked with internal lipid standards, followed by homogenizing with 240 µL methanol and 200 µL water. After adding 800 µL MTBE, the solution was ultrasound for 20 min at 4 °C and leave to set for 30 min at room temperature. The mixture was then centrifuged (15 min, 14,000g, 10 °C) and the upper layer was collected and dried under nitrogen.

2.5. Lipidomics LC-MS/MS analysis

Reverse phase (RP) chromatography was applied for LC separation with a CSH C18 column. The above-mentioned lipid samples were redissolved (200 µL 90 % isopropanol/ acetonitrile), centrifuged (14,000g, 15 min), and injected (3 µL). Initially, we set the mobile phase at 30 % solvent B for 2 min, then 100 % for 23 min, and finally 5 % for 10 min. Q-Exactive Plus was used for mass spectra in positive and negative mode, respectively. ESI parameters were set according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lipid Search was applied for the exploration of lipid species and subclasses based on the LC-MS/MS lipidomic analysis. In the LipidSearch database, there are over 30 lipid classes and more than 1,500,000 fragment ions. We set both the mass tolerance for fragment and precursor to 5 ppm. MetaX software was performed for the orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). Lipids with a variable importance in projection (VIP) score > 1 and p value < 0.05 were considered to be differentially expressed.

Lipid chain saturation refers to the sum of double bond numbers of fatty acid chains contained in lipid molecules and may serve as an indicator of underlying lipid metabolism. Using UPLC Orbitrap mass spectrometry system with LipidSearch software, we were able to determine the number of double bonds in lipid molecules and further analyze the ratio of saturation.

2.6. Proteomics sample preparation

Samples of mouse MGs were ground and lysed with 300 µL lysis buffer supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, followed with ultrasonication on ice (80 w, 3 min). The lysate was centrifuged (12,000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was left and stored at − 80 °C. Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kits were used for calculating the protein concentration according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

For protein digestion, 50 μg protein was taken from each sample, followed by dilution to the same volume and concentration. Dithiothreitol (DTT) was put to the protein solution and a final concentration of 5 mM DTT was obtained. After a 30 min incubation at 55 °C, iodoacetamide was added in each sample for a 10 mM concentration, and placed for 15 min at a room temperature. After that, precooled acetone was added to the above system (at −20 °C, overnight) and centrifuged (8000g, 10 min, 4 °C) to collect the precipitate. The enzymolysis diluent (protein: enzyme = 50:1 (m/m)) was used to redissolve the protein precipitate with incubation at 37 °C for 12 h. Finally, all obtained samples were lyophilized and refrigerated at − 80 °C.

For TMT labelling, each lyophilized sample was resuspended in 100 µL 200 mM TEAB and 40 µL of each sample was placed in new tubes. Eighty-eight microliter acetonitrile was added to the TMT vial and mixed. Then, for each sample, 41 µL of the above TMT solution was added, followed by incubation (room temperature, 1 h) after vortex mixing. Then, 5 % hydroxylamine (8 µL) was added to each sample for a 15 min incubation to terminate the reaction and stored at − 80 °C.

2.7. Proteomics LC-MS/MS analysis

RP separation was performed on the 1100 HPLC System (Agilent). For the RP gradient, mobile phases A and B were considered. Tryptic peptides were monitored at 210 and 280 nm and separated at a 300 µL/min fluent flow rate. We set sample collection for 8–60 min, and eluent collection for 1–15 min in centrifugal tube in turn. All analyses were performed using a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher). For peptide separation, we used a C18 column on the EASY-nLCTM 1200 system (Thermo Fisher). We acquired a full MS scans in the mass range of 300–1600 m/z with a mass resolution of 70000. The top 10 most intense peaks were fragmented and MS/MS spectra were obtained according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

All the raw data was thoroughly searched by the Proteome Discoverer software (version 2.4, Thermo Fisher). Database search was set to Trypsin digestion specificity. Carbamidomethyl(C) was considered a static modification and Oxidation(M), Acetyl(N-term) a dynamic modification. The false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 0.01 and protein groups considered for quantification required at least 2 peptides. Proteins were considered differentially expressed on criteria of fold change (FC) > 1.2 or < 0.83 and p < 0.05. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed for a visualization of differentiation results. For functional pathway analysis, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were carried out using the clusterProfiler package in R. The p value of each pathway was analyzed with correction using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

2.8. Machine learning algorithm

The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression model and t test were applied for dimensionality reduction in order to prioritize the most relevant candidates among 1089 lipid species identified from lipidomic analyses. The t test is employed to determine whether there is a significant difference in the mean of the sample and its distribution. Prior to the t test, a Levene test is conducted to assess the distribution of chi-square statistics to determine if a t test is applicable. Following t test, features with the most significant correlation to the predicted outcome were identified through the LASSO model. LASSO regression is a widely utilized method that has demonstrated success in removing insignificant variables through the penalization of their corresponding regression coefficients. Utilizing the LASSO approach facilitates the process of feature selection and predictive signature construction. The “glmnet” R package was used to perform the LASSO algorithm, with the calculation formula described as:

Where β is the weight of the features, and λ is the hyperparameter of the penalty term. In this process, non-essential variables would be excluded and only the most significant variables correlated to the predicted outcome would be retained. The established formula for the predictive lipid signature was based on the non-zero coefficients in the LASSO regression model: signature = ∑ni = ∑Coefi × Xi, where Xi stands for the expression level of lipid i and Coefi for its regression coefficient.

2.9. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (version 7.0) and R software (version 4.0.4) were used for all our statistical analyses. Student’s t tests were utilized to analyze the difference between the two age groups. Benjamini-Hochberg method was applied for calculation of adjusted p value. The p values < 0.05 was deemed as statistically significant (*); p < 0.01 (**); p < 0.001 (***).

3. Results

3.1. Distinctive MGD phenotype in aged mice

The weighing of C57BL/6J mice at two distinct ages, young (2 months) and aged (24 months), was performed prior to their sacrifice. Aged mice had, on average, a higher body weight than young mice, which was measured 29.67 ± 3.76 g compared to 16.73 ± 0.66 g, respectively (Fig. 2A). After careful dissection from surrounding eyelid tissue, mouse MGs were weighed. As illustrated in Fig. 2B, no significant statistical difference was found between the young (10.83 ± 2.54 mg) and aged group (10.80 ± 3.23 mg).

Fig. 2.

Phenotypes of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) in mice between the young (Y) and aged (O) group. (A) Body weight. (B) tarsal plate weight. (C, D) Slit lamp images showing white light photos (left) and fluorescein staining (right) of the mouse cornea. (E) Corneal opacity score. (F) Corneal fluorescein staining score. (G) Oil Red O (ORO) staining of frozen upper eyelid sections. The white arrow indicated white opalescent structures covering the corneal surface. The black dotted line indicated a single meibomian gland (MG). Scale bar: 500 µm.

It is apparent from slit lamp images that the corneal surface of the aged group is characterized by conspicuous white opalescent structures that contrast with the relatively homogeneous, clear corneas of the young mice (Fig. 2C,D). In addition, the eyelids of the aged mice exhibited noticeably hypertrophies (Fig. 2C,D). The corneal opacity score based on Draize test showed a significant increase in the aged group, indicating a higher level of eyelid inflammation and corneal damage (Fig. 2E). Notably, an evident augmentation was observed in corneal fluorescein uptakes and fluorescein staining score in the aged mice, suggesting MGD-related ocular surface inflammation (Fig. 2C,D,F). To further investigate age-related morphological changes in MGs, the excised upper eyelids were subjected to ORO staining, which revealed strikingly atrophic MGs with decreased lipid droplet content in the aged group (Fig. 2G). Overall, the successful establishment of a mouse model of ARMGD phenotype was confirmed.

3.2. Differentially expressed proteins in ARMGD

Proteomic analysis was conducted in MGs of 2-month (n = 3) and 2-year-old (n = 3) mice. A total of 5564 protein groups and 42,010 peptides were detected (Fig. 3A), with a similar distribution among different samples (Fig. 3B,C). The PCA algorithm (PC1 vs. PC2) of the protein data revealed a significant trend distinction between the young and aged group (Fig. 3D). Overall, 375 proteins were determined to be differentially expressed (Table S2). Of these, 170 proteins were considered to be significantly upregulated (FC > 1.2 and p < 0.05) and 205 proteins were significantly downregulated (FC < 0.83 and p < 0.05) in the aged vs. young group (Fig. 3E). Notably, the top 10 upregulated protein groups included A1bg, Ighm, Myl2, Afap1l1, S100a8, Jchain, Cma1, S100a9, Retnlg, and Mup17. The top 10 downregulated proteins were Ndrg1, Pc, Ascc3, Manbal, Pdk2, Lgals7, Dnase2, Dnajb12, Bcap31, and Cln5. Based on hierarchical clustering of the 375 differentially expressed proteins, distinct expression pattern was observed between the young and aged group, confirming the credibility of the applied analytical approach (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Differentially expressed proteins in meibum between the aged (O) vs. young (Y) group. (A) Identification of 5564 protein groups and 42,010 peptides. (B, C) Distribution of proteins among different samples. (D) Principal component analysis (PCA) revealing a significant trend distinction between the two age groups. (E) Volcano plot showing 170 significantly upregulated proteins and 205 downregulated proteins between the O vs. Y group. (F) Hierarchical clustering based on the 375 differentially expressed proteins.

3.3. Pathway enrichment and protein interaction network analysis

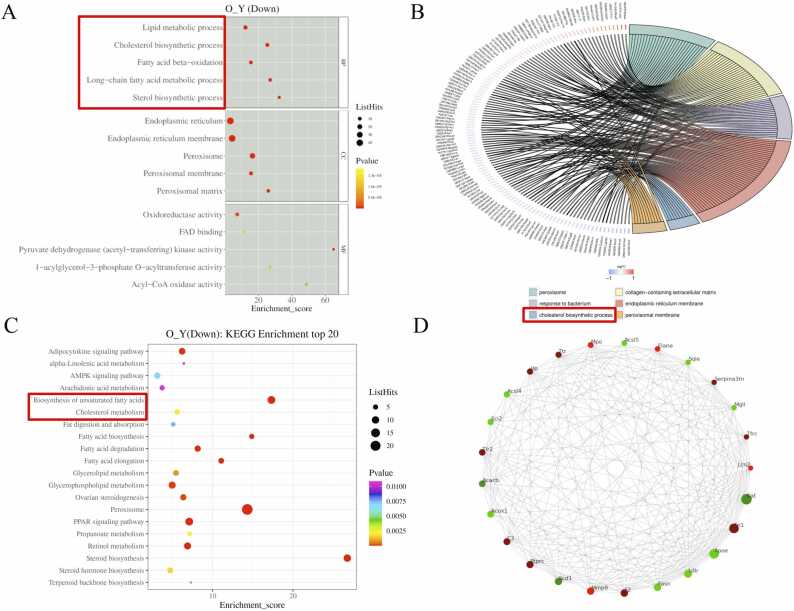

For our purposes, we focused our results on functional alterations related to lipid metabolism. The GO enrichment analysis revealed that the downregulated proteins between the aged vs. young group were mostly enriched in lipid metabolic process, cholesterol biosynthetic process, fatty acid beta-oxidation, long-chain fatty acid metabolic process, and sterol biosynthetic process (Fig. 4A, Table S3). To better illustrate our data, a chord diagram of GO enrichment analysis was applied. Among the six top GO terms (sequenced by their -log10 p-value), “cholesterol biosynthetic process” was the only enriched cluster associated with lipid metabolism (Fig. 4B). According to KEGG pathway analysis, “cholesterol metabolism” and “biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acid” were among the most abundant pathways identified (Fig. 4C, Table S4). In addition, we established the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network using the STRING database, visualizing the predicted relationships among the top 25 most co-regulated proteins (Fig. 4D). Notably, certain proteins (Sqle, Fdft1, Lss, Dhcr24, and Msmo1) involved in the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway were among the top 70 interacted protein nodes, indicating their potential role as therapeutic biomarkers (Table S5).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of protein enrichment and interaction network. (A) Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealing the downregulated pathways in the aged (O) vs. young (Y) group, including lipid metabolic process, cholesterol biosynthetic process, fatty acid beta-oxidation, long-chain fatty acid metabolic process, and sterol biosynthetic process. (B) Chord diagram of GO showing the cholesterol biosynthetic process among the most enriched clusters. (C) Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis identifying cholesterol metabolism and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acid among the most abundant pathways. (D) protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks for the top 25 most co-regulated proteins.

3.4. Differences in total lipid and subclass, and lipid saturation analysis

The MGs from the 2-month (n = 6) and 2-year-old (n = 6) groups were subjected to lipidomic analysis. A total number of 1089 lipid species from 25 classes were identified: 239 phosphatidylcholine (PC), 225 triglyceride (TG), 152 phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), 132 phosphatidylserine (PS), 75 sphingomyelin (SM), 64 cardiolipin (CL), 49 phosphatidylinositol (PI), 35 lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), 28 phosphatidylglycerol (PG), 19 lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), 16 diglyceride (DG), 8 ChE, 7 acyl carnitine (AcCa), 7 sphingosine (So), 5 lysophosphatidylglycerol (LPG), 5 lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI), 4 wax exters (WE), 4 lysophosphatidylserine (LPS), 4 coenzyme (Co), 3 gangliosides (GM3), 2 fatty acid (FA), 2 phosphatidylinositol (PIP), 2 phytosphingosine (phSM), 1 sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol (SQDG) and 1 digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) (Fig. 5A, Table S6).

Fig. 5.

Differences in total lipid and subclass, and lipid saturation analysis. (A) Total lipid species among 25 lipid classes identified in our study. (B-M) Differences in total lipids (B), proportion of lipid subclasses (C, D), expressions of ChE, TG, DGDG and PIP (E-H), and ratio of saturation for ChE, TG, PS, PI and LPC (I-M) between the young and aged group. ChE, cholesteryl esters; DEDG, digalactosyldiacylglycerol; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PIP, phosphatidylinositol; PS, phosphatidylserine; TG, triglyceride.

Through comprehensive analysis of total lipids from six independent MG samples in each age group, it was found that the overall level of lipids were significantly lower in the aged mice compared to their young counterparts (Fig. 5B). Moreover, a considerable disparity in lipid subclasses was observed between the young and aged mice. Within the aged group, the top five lipid subclasses were ChE (56.877 %), PC (12.644 %), TG (9.912 %), PE (9.199 %) and PS (4.178 %), whereas in the young group, ChE (78.086 %), PC (7.331 %), PE (4.861 %), TG (3.622 %) and PS (2.236 %) constituted the top five lipid subcategories (Fig. 5C,D). In order to assess the alterations in lipid subclass, a correlation evaluation of 25 lipid subclasses between the two age groups was conducted by the correct for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method. Results indicated that, in aged mice, ChE and PIP exhibited a significant decrease (Fig. 5E,F), while TG and DGDG displayed a marked increase (Fig. 5G,H). No significant difference was observed in the expression of the other 21 lipid subclasses between the two groups (p > 0.05) (Table S7). In addition, we found a strong correlation between aging and the ratio of saturation present in the subclasses of ChE, TG, PS, PT, and LPC. Specifically, in the aged group, we observed a decrease in the ratio of saturated ChE, TG, and PS (Fig. 5I, G, K), while the ratio of saturated PT and LPC was significantly increased compared to the young group (Fig. 5L, M).

3.5. Visualization of differentially expressed lipids

The OPLS-DA scores of the groups were R2X = 0.847, R2Y = 0.992, and Q2 = 0.965 in positive and negative ion modes (Fig. 6A), and the corresponding OPLS-DA validation plots showed R2 and Q2 intercept parameters of (0.0, 0.7585) and (0.0, −0.6914), respectively (Fig. 6B). These results clearly demonstrated an excellent separation of lipidome signature for the young and aged group. Based on univariate analysis, the volcano plot showed lipid species that were upregulated (FC > 1.5 and p < 0.05) and downregulated (FC < 0.67 and p < 0.05) in the aged vs. young group (Fig. 6C). Acting on a score of VIP > 1 and p < 0.05, 47 lipid species of 7 classes (PE, SM, PS, PC, DG, ChE and TG) were considered to be differentially expressed between the two groups (Fig. 6D, Table S6). Six of the 47 lipid species, comprising ChE(25:0)+NH4, ChE(26:0)+NH4, ChE(26:1)+NH4, ChE(28:1)+NH4, ChE(30:1)+NH4, and ChE(32:2)+NH4, were found to have relatively low expression levels in the aged group (VIP > 1, FC < 0.67 and p < 0.05), whereas 33 had higher levels (VIP > 1, FC > 1.5 and p < 0.05). We then narrowed our screening criteria to VIP > 5 and p < 0.001, and found the most likely lipid species with biological significance are ChE(25:0)+NH4, ChE(26:1)+NH4, PE(19:0/22:6)+H and ChE(28:1)+NH4 (Table S6).

Fig. 6.

Visualization of differentially expressed lipids. (A, B) OPLS-DA analysis illustrating an excellent separation of lipidome signature for the young (Y) and aged (O) group. (C) Volcano plot showing upregulated (FC > 1.5 and p < 0.05) and downregulated (FC < 0.67 and p < 0.05) lipid species between the O vs. Y group. (D) 47 differentially expressed lipid species in 7 classes (PE, SM, PS, PC, DG, ChE, and TG) in O vs. Y group based on VIP > 1 and p < 0.05. (E, F) Hierarchical clustering (E) and correlational analysis (F) for the 47 differentially expressed lipids based on VIP > 1 and p < 0.05. (G) Chord plot revealing the correlations among the 7 lipid subclasses. (H) Interaction network of the 47 differentially expressed lipids. OPLS-DA, orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis; VIP, variable importance in projection; ChE, cholesteryl esters; DG, diglyceride; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PS, phosphatidylserine; SM, sphingomyelin; TG, triglyceride.

In order to evaluate lipids with similar properties and the differences of lipid expression patterns among samples, we performed the hierarchical clustering for the 47 differentially expressed lipids (Fig. 6E). Subsequently, correlation analysis was applied to unravel their mutual metabolic and regulatory relationship. As seen from Fig. 6F, ChE showed a negative correlation with the other six lipid subclasses, indicating their possible synthesis and transformation relationship. The positive correlation between the remaining six lipid subclasses was indicative of their participation in the same synthetic pathway. Furthermore, the lipid-lipid correlation matrix was converted to the chord and network plot (correlation coefficient |r| > 0.8 and p < 0.05) for the visualization of lipid interactions. The chord plot illustrated the correlation between and within lipid subclasses (Fig. 6G). The predicted lipid interaction network contained 6 downregulated and 41 upregulated lipid species (Fig. 6H), and revealed that certain lipid species play pivotal roles, such as ChE(26:1)+NH4, PE(38:4p)+H and TG(18:1/18:1/20:4)+NH4.

3.6. Machine learning of lipid signature predictive of ARMGD

After applying t test and LASSO algorithm, we established a signature predictive of ARMGD consisting of 9 lipid molecules: PE(36:1p)-H, PC(16:0/22:5)+HCOO, ChE(26:1)+NH4, ChE(26:0)+NH4, ChE(30:1)+NH4, TG(27:0/16:0/18:1)+NH4, TG(26:0/18:1/18:1)+NH4, PI(16:1/14:1)-H, and PC(36:4e)+HCOO. As illustrated in Fig. 7A, the LASSO algorithm determined the correlation coefficient of each signature, constrained by mean squared error (MSE). In addition, the relationship between the feature coefficients and the total feature weight Lambda was demonstrated in Fig. 7B. After selecting coefficients out of the non-zero features, a total of nine lipid species were obtained (at this time the MSE is the lowest), which are strongly predictive of ARMGD (Fig. 7C). A matrix diagram was established to elucidate the correlations among the 9 lipid molecules (Fig. 7D). Consequently, as a result of ML verification, a reliable 9-lipid signature was constructed, providing a robust diagnostic tool with significant clinical implications for ARMGD.

Fig. 7.

Machine learning (ML) of lipid signature predictive of age-related meibomian gland dysfunction (ARMGD) using the LASSO model. (A) The mean-square error (MSE) (y-axis) was plotted against the hyperparameter of the penalty term (λ) (bottom x-axis) in the LASSO model. (B) The relationship between the coefficients of signature and the total signature weight Lamda. (C) LASSO coefficient profiles of each candidate lipid species. (D) The correlation matrix for the 9 candidate lipid molecules. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

3.7. Potential proteins and lipids network involved in ARMGD

Based on proteomic analyses, our results revealed the essential role of lipid metabolic pathways in the development of ARMGD, particularly cholesterol biosynthetic processes. Combining GO and PPI results, several proteins from cholesterol biosynthetic pathways were proposed as potential biomarkers, including Lss, Dhcr24, and Fdft1 (Fig. 3F). The lipidomic studies further confirmed the vital role of ChE in the pathogenesis of ARMGD. Through ML construction, ChE(26:0)+NH4, ChE(26:1)+NH4, and ChE(30:1)+NH4 were validated as the most promising lipid diagnostic molecules. To summarize the findings of our omics research, we propose a hypothetical pathogenic mechanism involving both proteins and lipids that may underlie ARMGD (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Hypothesis of proteins and lipids networks involved in age-related meibomian gland dysfunction (ARMGD).

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the role of lipid metabolism in ARMGD through integrated proteomic and lipidomic analyses. Subsequent ML model established a nine-lipid signature of diagnostic value. Taken together, we proposed a hypothesis that several age-related lipid molecules (ChE(26:0), ChE(26:1), and ChE(30:1)) and protein biomarkers (Dhcr24, Lss, and Fdft1) from cholesterol biosynthetic pathways may contribute to the pathogenesis of MGD. Our findings represent a significant step towards developing novel diagnostic, preventive, and personalized therapeutic strategies for ARMGD.

Aging has long been associated with lipid metabolic processes that contribute to the development of many chronic and inflammatory disorders [25]. Understanding the intricate lipid metabolism and signaling is therefore critical for the healthcare intervention of the older populations. Systemic alterations in lipid metabolic processes, such as lipase activity and lipolysis, have been extensively researched [26]. Recent research is now focused on identifying specific alterations in lipid metabolism within individual organs, which are generally in consistent with systemic results [27]. Nevertheless, certain organ-specific variations may occur in different areas of the body, such as the kidney, brain, or muscles [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. For instance, a recent study used lipidomics to identify a specific lipid signature that associates with aging in skeletal muscle, inducing both inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress [33]. Although aging is identified as the primary risk factor for MGD, research attention has mainly focused on cellular and morphological studies and related functional investigations such as therapeutic hydrogel for the treatment of eyelid inflammations [34]. The exploration of quantitative and qualitative changes in eyelid meibum lipids during the aging process is rare. Through lipidomic approaches, some studies have investigated the influence of gender on eyelid meibum content, with female and male mice exhibiting indistinguishable lipid profiles and functioning in a similar pattern [35], [36]. Recently, Suzuki et al. demonstrated a significant decrease in non-polar lipids such as ChE and a significant increase in polar lipids among elderly patients [37]. Besides, through comparative analyses of eyelid lipid composition, researchers have found striking similarities between mouse and human samples [38]. Considering that two-year-old mice showed both clinical and histological manifestations of MGD, we eventually selected C57BL/6 J female mice that were two months and two years old for our comprehensive omics investigation.

The major components of meibum have been reported to be nonpolar lipids, including free cholesterol, WE, ChE, TG, and diesters [39]. There are also smaller amounts of more polar compounds, such as SM, free fatty acids (FFA), and phospholipids (PL) [40], [41]. Alterations in the lipid and protein profiles of meibum have been suggested to contribute to the increase in tear film instability experienced by MGD patients. However, the exact causality of these metabolic changes has not been established to date. In the present work, we found that total lipids from mouse meibum were significantly reduced with aging. The proteomics revealed that the differentially expressed proteins were primarily enriched in lipid metabolic processes, including cholesterol biosynthetic process, fatty acid beta-oxidation, and long-chain fatty acid metabolic process. We further applied lipidomics to identify variations in lipid classes and found statistical differences in ChE, TG, DGDG, and PIP. Given that DGDG and PIP account for a minute proportion of the overall lipid content, it is hypothesized that ChE and TG are the most pivotal lipid classes responsible for the modulation of lipid metabolism during the process of aging. Using ML models, we were able to construct a diagnostic signature consisting of nine lipid species. The three ChE molecules that appeared to be the most promising diagnostic biomarkers were ChE(26:1)+NH4, ChE(26:0)+NH4, and ChE(30:1)+NH4. A network diagram was ultimately drawn to depict the potential interactions between proteins and lipids involved in ARMGD.

Although ChE represents a small proportion of total lipids in most tissues, it plays a critical role in various age-related inflammatory disorders [42]. In atherosclerosis and chronic kidney disease, the involvement of ChE in macrophage inflammatory processes contributes significantly to the disease progression [43]. Studies have also reported that elevated serum cholesterol levels are seen in moderate-to-severe cases of MGD [44], [45]. In eyelid meibum, however, ChE is reported to be one of the main lipid components [46]. Clinically, a notable disparity in ChE expression has been observed in subsets of normal meibum donors with stable tear films, suggesting that substantial variations can be tolerated without compromising tear film dynamics [47], [48]. Reduction in ChE can inversely influence the melting point of meibum, leading to an increase in meibum viscosity characteristic of MGD [49]. In addition, there is increasing evidence that ChE may serve multiple immunological roles and impart antimicrobial protection to the ocular surface [50], [51]. Through UPLC Orbitrap mass spectrometry system, our lipidomic results revealed a decline in the proportion of saturated ChE and TG during the aging process. It is plausible that the decrease in the quantity and saturation pattern of ChE resulted in tear film lipid instability and elevated viscosity, which is critical for the pathogenesis of MGD [52]. Notably, one of our proposed disgnostic biomarkers, ChE(26:1), was identified as being the most responsive to peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-γ (PPARγ) agonist rosiglitazone in human meibomian gland epithelial cells (HMGECs) [53]. Similarly, ChE(26:0) and ChE(30:1) were found to be suppress by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in HMGECs, leading to interference of cell differentiation and nonspecific TG remodeling [54]. The intricate crosstalk underlying these lipid-modifying drugs and ChE represents an important therapeutic strategy for MGD and warrants further investigation.

TG is closely related to a variety of metabolic disorders, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and nonalcoholic liver disease [55]. The level of total blood TG tends to increase with age, acting as an important risk indicator for these metabolic disturbances. Studies have indicated that aging can adversely affect mitochondrial function and autophagy activities involved in TG breakdown, leading to TG accumulation in both plasma and cells [55], [56]. Recent investigations have revealed a significant correlation between the elevation of TG in plasma and the occurrence of MGD [57], [58]. In meibum, however, their intricate relationship remains unclear [13]. TG has been reported to range from 0.05 % and 6 % in meibum of healthy individuals [39]. Although considered a minor constituent in meibum, TG is suggested to be upregulated in a preclinical disease model of MGD, suggesting its potential significance as an indicator of disease pathology [59]. It is possible that the structure of TG can disrupt the ordered packing of other major lipid species, such as WE and ChE, leading to a decreased viscosity of the tear film lipid layer. In our study, despite a substantial reduction in total lipid content within mouse meibum, the level of TG has been shown to increase significantly (p < 0.01), indicating that TG accumulation may be a characteristic feature of the aging process. Further in-depth researches are necessary to elucidate the potential impact of TG on the physiopathogenesis of ARMGD.

Recent investigations have revealed that several critical genes involved in cholesterol biosynthetic pathways are essential for meibogenesis, including Acat1/Acat2, Dhcr7, Dhcr24, Fdft1, Lss, Msmo1, and Sqle [36], [38], [41]. These findings are consistent with our multi-omics results that cholesterol biosynthetic pathways play a crucial role in the development of ARMGD, in which key protein markers are involved, such as Lss, Dhcr24, and Fdft1. Lanosterol synthase, also known as Lss, is responsible for the conversion of (S)−2,3-epoxysqualene into lanosterol in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. By regulating cholesterol metabolism, it has been observed that Lss disruption is associated with various cholesterol-related disorders [60], [61]. Notably, mutations in Lss have been linked to multiple ocular diseases, including cataracts and age-related macular degeneration [62], [63]. Farnesyl diphosphate farnesyl transferase 1 (Fdft1), an enzyme at a key juncture in cholesterol biosynthetic pathways, catalyzes squalene formation from two farnesyl diphosphate molecules. Fdft1 has been implicated in cancer pathogenesis and the development of various malignancies [64], [65]. Notably, the discovery of hypomorphic Lss and Fdft1 mutations in a rat model of hereditary cataracts implies their synergistic effect in facilitating cataract onset [65]. Moreover, Fdft1 was involved in different chronic inflammatory diseases, such as atherosclerosis and diabetes [66], [67]. Dhcr24, or 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase, is a pivotal enzyme in the terminal step of cholesterol biosynthesis. It has been discovered that Dhcr24 exhibits neuroprotective properties by inhibiting apoptosis in degenerative Alzheimer’s disease [68]. Additionally, Dhcr24 has been found to provide anti-inflammatory protection against oxidative stress in various tissues, including the cornea [69], [70]. To date, our identified protein markers has been extensively investigated in various disease models. Further experimental investigations are warranted to clarify their functions in ARMGD development.

It is important to note that our study is subject to certain limitations. Specifically, our analyses of omics data were conducted on murine samples. Further comprehensive analysis of human meibum is necessary to validate our results. In addition, complementary investigations involving gene knockout animal model and targeted drug research will be conducted to substantiate our findings on both biological and functional levels. Although open questions remain, the omics results showcased a plausible hypothesis as to how age-related lipid metabolic alterations may contribute to the development of MGD.

5. Conclusions

To summarize, this is the first integrated multi-omics and ML study that deeply analyzed age-related lipid metabolic and signaling alterations in MGD. The proteomic analysis unveiled the major role of cholesterol biosynthesis pathway and associated metabolic mediators, including Dhcr24, Lss, and Fdft1. The lipidomic profiling further confirmed the vital role of ChE in ARMGD. Through ML construction, ChE(26:0), ChE(26:1), and ChE(30:1) were identified as the most promising diagnostic molecules. This research provides valuable insights into the diagnosis and personalized pharmaceutical design of ARMGD, offering a pathway to improved clinical outcomes. Further investigations are warranted to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms and develop more effective treatments.

Funding

This work was supported by the funding grants including the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82271041 and 82201136), Shanghai Key Clinical Specialty, Shanghai Eye Disease Research Center (2022ZZ01003), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission: Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (No. 20161421), Disciplinary Crossing Cultivation Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2022QN055), and Basic Research Programs of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (JYZZ152).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuchen Cai: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Siyi Zhang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources. Liangbo Chen: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Yao Fu: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Shanghai Key Laboratory of Orbital Diseases and Ocular Oncology for providing the research platform. We also thank Shanghai OE Biotech for the proteomics analysis and Shanghai Applied Protein Technology for the lipidomics profiling.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2023.08.026.

Contributor Information

Liangbo Chen, Email: chenliangbo@sjtu.edu.cn.

Yao Fu, Email: fuyao@sjtu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Data Availability

The omics data of this study will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Knop E., Knop N., Millar T., Obata H., Sullivan D.A. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the meibomian gland. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1938. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bron A.J., Tiffany J.M., Gouveia S.M., Yokoi N., Voon L.W. Functional aspects of the tear film lipid layer. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:347–360. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki T., Teramukai S., Kinoshita S. Meibomian glands and ocular surface inflammation. Ocul Surf. 2015;13:133–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butovich I.A. The Meibomian Puzzle: combining pieces together. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:483–498. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemp M.A., Nichols K.K. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: a survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf. 2009;7:S1–S14. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viso E., Gude F., Rodríguez-Ares M.T. The association of meibomian gland dysfunction and other common ocular diseases with dry eye: a population-based study in Spain. Cornea. 2011;30:1–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181da5778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson J.D., Shimazaki J., Benitez-del-Castillo J.M., Craig J.P., McCulley J.P., Den S., et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1930–1937. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S., Yang K., Wang J., Li S., Zhu L., Feng J., et al. Effect of a novel thermostatic device on meibomian gland dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial in chinese patients. Ophthalmol Ther. 2022;11:261–270. doi: 10.1007/s40123-021-00431-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang H.S., Parfitt G.J., Brown D.J., Jester J.V. Meibocyte differentiation and renewal: insights into novel mechanisms of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) Exp Eye Res. 2017;163:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding J., Sullivan D.A. Aging and dry eye disease. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borchman D., Foulks G.N., Yappert M.C. Confirmation of changes in human meibum lipid infrared spectra with age using principal component analysis. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:778–786. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.490895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borchman D., Foulks G.N., Yappert M.C., Milliner S.E. Differences in human meibum lipid composition with meibomian gland dysfunction using NMR and principal component analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:337–347. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butovich I.A., Suzuki T. Effects of aging on human meibum. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:23. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.12.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujio K. Significance of the multiomics approach to elucidate disease mechanisms in humans. Inflamm Regen. 2022;42 doi: 10.1186/s41232-022-00227-5. 41, s41232-022-00227–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goecks J., Jalili V., Heiser L.M., Gray J.W. How machine learning will transform biomedicine. Cell. 2020;181:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths W.J., Wang Y. Mass spectrometry: from proteomics to metabolomics and lipidomics. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:1882. doi: 10.1039/b618553n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu J., Bankov G., Kim M., Wretlind A., Lord J., Green R., et al. Integrated lipidomics and proteomics network analysis highlights lipid and immunity pathways associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2020;9:36. doi: 10.1186/s40035-020-00215-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Passaro A.P., Marzuillo P., Guarino S., Scaglione F., Miraglia del Giudice E., Di Sessa A. Omics era in type 2 diabetes: from childhood to adulthood. World J Diabetes. 2021;12:2027–2035. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v12.i12.2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ota M., Fujio K. Multi-omics approach to precision medicine for immune-mediated diseases. Inflamm Regen. 2021;41:23. doi: 10.1186/s41232-021-00173-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye B., Liu K., Cao S., Sankaridurg P., Li W., Luan M., et al. Discrimination of indoor versus outdoor environmental state with machine learning algorithms in myopia observational studies. J Transl Med. 2019;17:314. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugimoto K., Murata H., Hirasawa H., Aihara M., Mayama C., Asaoka R. Cross-sectional study: does combining optical coherence tomography measurements using the ‘Random Forest’ decision tree classifier improve the prediction of the presence of perimetric deterioration in glaucoma suspects? BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan H., Shan X., Wei S., Liu F., Li W., Lei Y., et al. Abnormal spontaneous brain activities of limbic-cortical circuits in patients with dry eye disease. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.574758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Draize J.H., Woodard G., Calvery H.O. Methods for the study of irritation and toxicity of substances applied topically to the skin and mucous membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1944;82:377–390. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauly A., Brignole-Baudouin F., Labbe´ A., Liang H., Warnet J.-M., Baudouin C. New tools for the evaluation of toxic ocular surface changes in the rat. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5473. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mutlu A.S., Duffy J., Wang M.C. Lipid metabolism and lipid signals in aging and longevity. Dev Cell. 2021;56:1394–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mennes E., Dungan C.M., Frendo-Cumbo S., Williamson D.L., Wright D.C. Aging-associated reductions in lipolytic and mitochondrial proteins in mouse adipose tissue are not rescued by metformin treatment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1060–1068. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung K.W. Advances in understanding of the role of lipid metabolism in aging. Cells. 2021;10:880. doi: 10.3390/cells10040880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guebre-Egziabher F., Alix P.M., Koppe L., Pelletier C.C., Kalbacher E., Fouque D., et al. Ectopic lipid accumulation: a potential cause for metabolic disturbances and a contributor to the alteration of kidney function. Biochimie. 2013;95:1971–1979. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egawa J., Pearn M.L., Lemkuil B.P., Patel P.M., Head B.P. Membrane lipid rafts and neurobiology: age-related changes in membrane lipids and loss of neuronal function: membrane lipid rafts, Cav-1 and neuroplasticity. J Physiol. 2016;594:4565–4579. doi: 10.1113/JP270590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou J., Zhang Y., Wu J., Qiao M., Xu Z., Peng X., et al. Proteomic and lipidomic analyses reveal saturated fatty acids, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, and associated proteins contributing to intramuscular fat deposition. J Proteom. 2021;241 doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Søgaard D., Baranowski M., Larsen S., Taulo Lund M., Munk Scheuer C., Vestergaard Abildskov C., et al. Muscle-saturated bioactive lipids are increased with aging and influenced by high-intensity interval training. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1240. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu L., Xie X., Liang T., Ma J., Yang L., Yang J., et al. Integrated multi-omics for novel aging biomarkers and antiaging targets. Biomolecules. 2021;12:39. doi: 10.3390/biom12010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S.-M., Lee S.H., Jung Y., Lee Y., Yoon J.H., Choi J.Y., et al. FABP3-mediated membrane lipid saturation alters fluidity and induces ER stress in skeletal muscle with aging. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5661. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19501-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L., Yan D., Wu N., Yao Q., Sun H., Pang Y., et al. Injectable bio-responsive hydrogel for therapy of inflammation related eyelid diseases. Bioact Mater. 2021;6:3062–3073. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butovich I.A., McMahon A., Wojtowicz J.C., Bhat N., Wilkerson A. Effects of sex (or lack thereof) on meibogenesis in mice (Mus musculus): comparative evaluation of lipidomes and transcriptomes of male and female tarsal plates. Ocul Surf. 2019;17:793–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butovich I.A., Bhat N., Wojtowicz J.C. Comparative transcriptomic and lipidomic analyses of human male and female meibomian glands reveal common signature genes of meibogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4539. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki T., Kitazawa K., Cho Y., Yoshida M., Okumura T., Sato A., et al. Alteration in meibum lipid composition and subjective symptoms due to aging and meibomian gland dysfunction. Ocul Surf. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2021.10.003. S1542012421001208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butovich I.A., McMahon A., Wojtowicz J.C., Lin F., Mancini R., Itani K. Dissecting lipid metabolism in meibomian glands of humans and mice: an integrative study reveals a network of metabolic reactions not duplicated in other tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2016;1861:538–553. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J., Green-Church K.B., Nichols K.K. Shotgun lipidomic analysis of human meibomian gland secretions with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2010;51:6220. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pucker A.D., Nichols J.J. Analysis of meibum and tear lipids. Ocul Surf. 2012;10:230–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butovich I.A. Meibomian glands, meibum, and meibogenesis. Exp Eye Res. 2017;163:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Souza S.L., Hallock K.J., Funari S.S., Vaz W.L.C., Hamilton J.A., Melo E. Study of the miscibility of cholesteryl oleate in a matrix of ceramide, cholesterol and fatty acid. Chem Phys Lipids. 2011;164:664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghosh S. Macrophage cholesterol homeostasis and metabolic diseases: critical role of cholesteryl ester mobilization. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;9:329–340. doi: 10.1586/erc.11.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bukhari A.A. Associations between the grade of meibomian gland dysfunction and dyslipidemia. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29:101–103. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31827a007d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dao A.H., Spindle J.D., Harp B.A., Jacob A., Chuang A.Z., Yee R.W. Association of dyslipidemia in moderate to severe meibomian gland dysfunction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.04.016. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mudgil P., Borchman D., Gerlach D., Yappert M.C. Sebum/meibum surface film interactions and phase transitional differences. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:2401. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eftimov P., Yokoi N., Tonchev V., Nencheva Y., Georgiev GAs. Surface properties and exponential stress relaxations of mammalian meibum films. Eur Biophys J. 2017;46:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s00249-016-1146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borchman D., Ramasubramanian A., Foulks G.N. Human meibum cholesteryl and wax ester variability with age, sex, and meibomian gland dysfunction. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:2286. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-26812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Green-Church K.B., Butovich I., Willcox M., Borchman D., Paulsen F., Barabino S., et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on tear film lipids and lipid–protein interactions in health and disease. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1979. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mudgil P. Antimicrobial role of human meibomian lipids at the ocular surface. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:7272. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mudgil P. Antimicrobial tear lipids in the ocular surface defense. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.866900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Georgiev G.As, Borchman D., Eftimov P., Yokoi N. Lipid saturation and the rheology of human tear lipids. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3431. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziemanski J.F., Wilson L., Barnes S., Nichols K.K. Saturation of cholesteryl esters produced by human meibomian gland epithelial cells after treatment with rosiglitazone. Ocul Surf. 2021;20:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ziemanski J.F., Wilson L., Barnes S., Nichols K.K. Prostaglandin E2 and F2a alter expression of select cholesteryl esters and triacylglycerols produced by human meibomian gland epithelial. Cells. 2021:41. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanders F., McNally B., Griffin J.L. Blood triacylglycerols: a lipidomic window on diet and disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:638–644. doi: 10.1042/BST20150235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang L., Yang C., Thomes P.G., Kharbanda K.K., Casey C.A., McNiven M.A., et al. Lipophagy and Alcohol-Induced Fatty Liver. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:495. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osae E.A., Steven P., Redfern R., Hanlon S., Smith C.W., Rumbaut R.E., et al. Dyslipidemia and meibomian gland dysfunction: utility of lipidomics and experimental prospects with a diet-induced obesity mouse model. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3505. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guliani B., Bhalla A., Naik M. Association of the severity of meibomian gland dysfunction with dyslipidemia in Indian population. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:1411. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1256_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ziemanski J.F., Wilson L., Barnes S., Nichols K.K. Triacylglycerol lipidome from human meibomian gland epithelial cells: Description, response to culture conditions, and perspective on function. Exp Eye Res. 2021;207 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Besnard T., Sloboda N., Goldenberg A., Küry S., Cogné B., Breheret F., et al. Biallelic pathogenic variants in the lanosterol synthase gene LSS involved in the cholesterol biosynthesis cause alopecia with intellectual disability, a rare recessive neuroectodermal syndrome. Genet Med. 2019;21:2025–2035. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iatrino R., Lanzani C., Bignami E., Casamassima N., Citterio L., Meroni R., et al. Lanosterol synthase genetic variants, endogenous ouabain, and both acute and chronic kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:504–512. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wada Y., Kikuchi A., Kaga A., Shimizu N., Ito J., Onuma R., et al. In: Engelking L., editor. Vol. 16. 2020. Metabolic and pathologic profiles of human LSS deficiency recapitulated in mice. (PLoS Genet). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grassmann F., Harsch S., Brandl C., Kiel C., Nürnberg P., Toliat M.R., et al. Assessment of novel genome-wide significant gene loci and lesion growth in geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:867. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanmalar M., Abdul Sani S.F., Kamri N.I.N.B., Said N.A.B.M., Jamil A.H.B.A., Kuppusamy S., et al. Raman spectroscopy biochemical characterisation of bladder cancer cisplatin resistance regulated by FDFT1: a review. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2022;27:9. doi: 10.1186/s11658-022-00307-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ha N.T., Lee C.H. Roles of farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1 in tumour and tumour microenvironments. Cells. 2020;9:2352. doi: 10.3390/cells9112352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ding J., Reynolds L.M., Zeller T., Müller C., Lohman K., Nicklas B.J., et al. Alterations of a cellular cholesterol metabolism network are a molecular feature of obesity-related type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes. 2015;64:3464–3474. doi: 10.2337/db14-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van den Hoek A.M., Özsezen S., Caspers M.P.M., van Koppen A., Hanemaaijer R., Verschuren L. Unraveling the transcriptional dynamics of NASH pathogenesis affecting atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:8229. doi: 10.3390/ijms23158229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peri A. Neuroprotective effects of estrogens: the role of cholesterol. J Endocrinol Invest. 2016;39:11–18. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tian K., Chang H.-M., Wang J., Qi M., Wang W., Qiu Y., et al. Inhibition of DHCR24 increases the cisplatin-induced damage to cochlear hair cells in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 2019;706:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu F., Lee S., Schumacher M., Jun A., Chakravarti S. Differential gene expression patterns of the developing and adult mouse cornea compared to the lens and tendon. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Data Availability Statement

The omics data of this study will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding authors.