Abstract

Engineered cardiac microtissues were fabricated using pluripotent stem cells with a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated c. 2827 C>T; p.R943x truncation variant in myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3+/−). Microtissues were mounted on iron-incorporated cantilevers, allowing manipulations of cantilever stiffness using magnets, enabling examination of how in vitro afterload affects contractility. MYPBC3+/− microtissues developed augmented force, work, and power when cultured with increased in vitro afterload when compared with isogenic controls in which the MYBPC3 mutation had been corrected (MYPBC3+/+(ed)), but weaker contractility when cultured with lower in vitro afterload. After initial tissue maturation, MYPBC3+/− CMTs exhibited increased force, work and power in response to both acute and sustained increases of in vitro afterload. Together, these studies demonstrate that extrinsic biomechanical challenges potentiate genetically-driven intrinsic increases in contractility that may contribute to clinical disease progression in patients with HCM due to hypercontractile MYBPC3 variants.

Keywords: MYBPC3, Afterload, Cardiac Microtissues, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Contractility

Graphical Abstract

Using a CMT model with tunable afterload, we show biomechanical stress potentiates hypercontractility and may contribute to disease progression in HCM patients with hypercontractile MYBPC3 variants.

Introduction:

Hereditary hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common genetic cardiomyopathy, affecting about one in 500 individuals1. A variety of sarcomeric protein mutations have been found to cause HCM, but the two most commonly implicated proteins, myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3) and beta myosin heavy chain (MYH7), account for 75% of probands with an identified genotype2. Many HCM-inducing mutations are associated with increased myocardial contractility due to increased myofilament calcium sensitivity and/or disruption of cardiomyocyte relaxation3. The recognition that hereditary HCM is associated with increased cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in the absence of pathologic increases in external load fueled the concept that power generation (work per time) or the force-time integral at the sarcomere level could drive cellular hypertrophy and account for differences in cardiomyocyte and myocardial morphology between variants associated with hypertrophic versus dilated cardiomyopathy4. Conversely, small molecule inhibitors of cardiac myosin, such as MYK-461, that alter crossbridge cycling at the sarcomere level attenuate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy without altering external left ventricular loading conditions in preclinical models5.

In at least half of patients with HCM, hypercontractility, hypertrophy of the basal portion of the interventricular septum, and other geometric factors produce dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction that increases left ventricular afterload6. Though this increased load could potentially exacerbate the hypertrophic process7,8, the interaction between HCM gene mutations and increased afterload is not well-defined. However, retrospective longitudinal observational data of monozygotic twins with HCM showed significant cardiac morphologic differences not accounted for by somatic genetic variance, suggesting that epigenetics and environment can affect HCM phenotype9. While medical therapies that suppress hypercontractility and ablative therapies that mitigate anatomic obstruction are sometimes employed, current guidelines do not endorse treatment of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in asymptomatic patients.

In vitro modelling of increased afterload has formerly been accomplished through several techniques that alter the biomechanical environment of cardiomyocytes grown in three-dimensional scaffolds. For instance, afterload has been altered using three-dimensional printed braces of different lengths that are clamped around the tissue scaffold upon which myocytes grow. These braces shorten the effective height of the scaffold, in turn increasing their stiffness and the afterload which contracting cells feel10. Additionally, afterload has been increased by creating tissue scaffolds of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and altering the ratio of curing agent to polymer. Increased curing agent increased the stiffness of polymer, again altering the load against which microtissues have to contract11. Other studies have examined dynamic changes of afterload on macro engineered heart tissues by inserting metal braces into hollow silicone posts on which the tissues grow, also effectively increasing the stiffness of the material and thereby the afterload12. This method was further refined by using magnetic braces, whose stiffness could be dynamically controlled using magnets13. While techniques for dynamic alteration of afterload in in vitro tissue modeling have been developed, contractile consequences of afterload on cardiomyopathies such as HCM have not been investigated.

Accordingly, the present study examines whether a pathogenic HCM mutation alters the acute and sustained contractile responses to variations in biomechanical load. For this purpose, we employed a modified engineered cardiac microtissue model with tunable in vitro afterload via use of cantilevers composed of a magnetorheological elastomer (MRE), a mixture of polydimethylsiloxane and iron particles which stiffens in the presence of a magnetic field14-16. Using this model, we compared the responses of cardiac microtissues (CMTs) fabricated with human cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (Hu-iPSC-CMs) with and without a pathogenic HCM mutation. In this model, we defined how extrinsic mechanical dosing affects functional metrics of CMTs at different stages of tissue maturation and how a MYBPC3 variant associated with HCM and hypercontractility alters the tissue-level adaptations to extrinsic biomechanical perturbations.

Methods:

Human Cardiomyocytes and Fibroblasts:

These studies utilized two cell lines of Hu-iPSC-CMs from the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute that were employed in previous studies17. As described in Seeger et. al, the protocol for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation and cardiomyocyte differentiation was approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Stem Cell Research Oversight (SCRO) Committee, and iPSC lines were obtained from patients with informed consent17. One cell line of Hu-iPSC-CMs (SCVI204) was derived from a patient with HCM secondary to a heterozygous premature termination codon mutation (c. 2827 C>T; p.R943x) in MYBPC3 (MYBPC3+/−), and the other was an isogenic control in which the mutation was corrected via gene editing at the iPSC-stage before differentiation into Hu-iPSC-CMs (MYBPC3+/+(ed)). The Hu-iPSC-CMs were frozen at the same time point (20 days) during their differentiation from their respective iPSCs, and troponin positivity was equivalent. Throughout the experimental and data-analysis stages of this project, all investigators performing experiments with these cells were blinded to the identities of each cell line. Additional details concerning media and culture conditions are included in the online supplement. Human cardiac fibroblasts derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (Hu-iPSC-FBs) were obtained from a commercial vendor (product code Ax-B-HF02-2M, NCardia, Leiden, The Netherlands).

2D Magnetorheological Elastomer (MRE) Preparation:

A previously described MRE was employed in these studies to mimic changes in extracellular matrix stiffness16. The MRE is composed of a soft elastomeric substrate in which iron particles are embedded. The elastomer, Sylgard 527, was prepared per manufacturer’s directions by mixing equal weights of part A and part B and then mixed with Carbonyl Iron Powder (CIP-CC, BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany) at a 1:1 mass ratio. 5 g of the mixture was then poured into 35 mm culture dishes, degassed for 10 minutes, and baked for 24 hours at 60 °C. A magnetic field was applied to the culture dish through use of a cylindrical neodymium rare earth magnet (1-1/4” x ¼”, CMS Magnets, Garland, TX, USA). For the MRE employed in these experiments, exposure to a 95 mT magnetic field increases the Young's modulus of the MRE from 9.3 to 54.3 kPa and increases the shear modulus from 6.7 to 20.8 kPa.

2D Culture and Immunofluorescence Staining:

We used a 2D MRE culture format to assess whether MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) Hu-iPSC-CMs exhibited differential growth responses. 2D MREs were sterilized for 15 minutes with 70% ETOH then coated with Fibronectin and incubated for 3 hours at 37 °C. Hu-iPSC-CMs were then lifted from their plastic dish and replated on the MREs at 300,000 cells/MRE. For the stiff condition, an external magnet was applied soon after plating. After 48 hours of culture, Hu-iPSC-CMs were rinsed with PBS and fixed in prechilled methanol at −20 °C for 10 minutes. After washing with PBS three times, cells were placed in blocking buffer (5% BSA in PBS) for 2 hours at room temperature, then labeled with primary antibodies for minimum 12 hours at 4 °C (for Anti-α-Actinin (Sigma Aldrich #A7732)). Cells were then washed and labeled with secondary antibodies (555 Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse) at room temperature for 2 hours. Next, DAPI (1 μg/mL in sterilized de-ionized water, Sigma-Aldrich) was added for 5 to 10 minutes in a dark environment. After a final wash with PBS, cultures on the 2D MRE were maintained in PBS until imaging.

Cell Area Quantification:

Immunofluorescence images were collected on an upright microscope (Nikon eclipse 80i) with a 20x water-emergent objective. As already described16,18 each cell was individually measured for cell area using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; LOCI, Madison, WI, USA). Regions of interest containing the entire cell excluding the nuclei were used to determine fractional coverage of cytoskeletal proteins, and area coverage was determined by a thresholded mask within the region of interest.

Tunable Afterload Cardiac Microtissue (CMT) Device Fabrication:

CMT silicon master template wafers were fabricated as previously described11,19,20. Briefly, silicon master template wafers are a positive mold of the final device: a 3x3 array of paired cantilevers, with each pair surrounded by a mini-well for cell seeding. Negative molds of this wafer were cast by pouring a pre-polymer (15:1 base-to-curing agent ratio) of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Corning Sylgard 184) onto the wafer. The molds were then separated from the wafer and cut into square PDMS stamps. The stamps were then silanized with perfluorinated silane19. After silanization, PDMS pre-polymer (5:1 base-to-curing agent ratio) was mixed with Carbonyl Iron Powder (CIP-CC, BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany) at a 1:1 mass ratio, and 1 g was poured onto each stamp. Stamps were degassed for 60 seconds, and the excess PDMS-Iron mixture was removed. Next, a thin layer of PDMS pre-polymer (5:1 base-to-curing agent ratio) was poured onto the stamps and inverted onto a previously prepared 1 g layer of PDMS in a 35 mm dish (5:1 base-to-curing agent ratio, cured at 60 °C for 1 hour). This was subsequently baked at 60 °C for 24 hours, as shown in Figure S1. Stamps were carefully removed from the molds using isopropyl alcohol to avoid damaging the CMT platform.

Calibration of Cantilever Spring Constant:

Cantilever spring constants were measured using a custom microtribometer as explained in the Supplemental Information and described briefly here (Figure 1A)21. The microtribometer is mounted on a microscope (IX81 Olympus) with a motorized stage (Prior Scientific). To measure the spring constant or stiffness of each cantilever, a pulled glass pipette was used to displace each post (100-200 μm) towards the center of the well at a constant velocity. Tangential force and distance traversed were recorded simultaneously enabling the calculation of CMT cantilever spring constant using Hooke’s Law. Graded increases in spring constants with application of external magnetic fields were similarly quantified (Figure 1A and Figure 1B). For these experiments, two annular axially magnetized N42 neodymium rare earth magnets were used, with a magnetic flux density of 150 and 168.6 mT at the center of the magnet (see Supplement). As shown in Figure S2, the stiffnesses of cantilevers without MRE were not statistically different (p=0.36) between magnet and non-magnet conditions demonstrating that our microtribometer was not affected by the magnetic field. There was a stepwise increase in MRE cantilever stiffness with application of graded increases in magnetic field strength (ANOVA p<0.001). There was an increase in stiffness of 0.06 ± 0.02 N/m from without magnet to the 150 mT magnet and increase of 0.07 ± 0.02 N/m from the 150 mT magnet to the 168.6 mT magnet (Figure 1C and 1D). The 168.6 mT magnet was used for all CMT experiments.

Fig. 1.

Calibration of cantilevers in MRE-CMT platform. (A) An annular magnet is placed around platform, stiffening cantilevers filled with iron particles. Using a custom microtribometer, we measure the force required to displace the cantilever a pre-specified distance. (B) Representative force-displacement curves of MRE cantilevers subjected to different magnetic fields. The cantilever spring constant, or stiffness, is the slope of the force-displacement curve. (C) In paired analysis, MRE cantilevers (n=60) show stepwise increases in stiffness with increases in magnetic field strength using small and large magnets. (D) Paired analysis of the same 60 cantilevers in non-magnet, 150mT annular magnet, and 168.6mT annular magnet conditions, showing an increase in cantilever stiffness in the presence of a magnetic field (ANOVA was performed on the stiffness followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test, significance is indicated by ****: p<0.0001, ***: p<0.001, **: p<0.01, and *: p<0.05)

Seeding of CMTs onto 3D MRE Platforms:

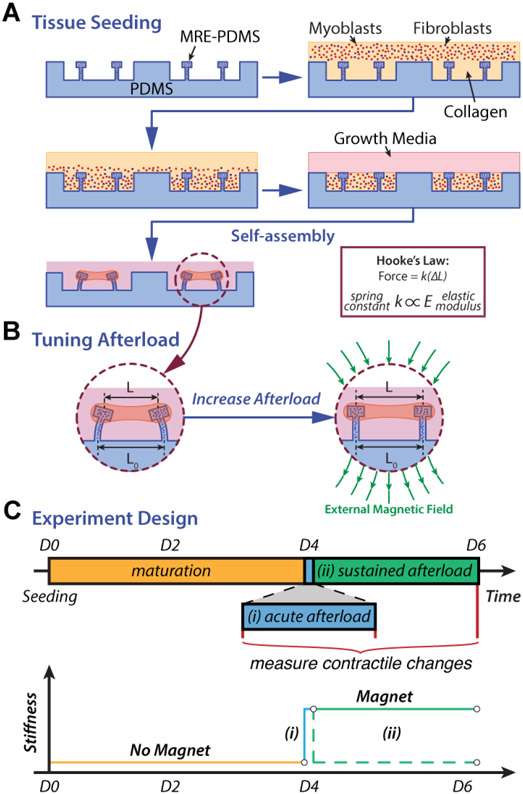

MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs were made with the respective Hu-iPSC-CMs and Hu-iPSC-FBs. CMT arrays were seeded and matured as described in the supplement and prior reports11 (Figure 2A). Each array included 9 CMTs, and approximately 500,000 cells (95% Hu-iPSC-CMs, 5% Hu-iPSC-FBs) were seeded into each array along with collagen I and media. ROCK-inhibitor (Y27632) was added during the first 48 hours after seeding to allow CMTs to fully compact before contracting (see Supplement).

Fig. 2.

Overview of the MRE-CMT model and experimental design. (A) Schematic representation of the tissue seeding process. (B) Dynamic control of the cantilever stiffness by varying the magnetic field gradient. In a magnetic field, the iron particles align causing the cantilevers to stiffen. (C) Experimental design. In all studies, cells were seeded into the MRE-CMT devices at t=0. At 96 hours, functional metrics were measured for 71 CMTs (36 MYBPC3+/− and 35 MYBPC3+/+(ed)). Afterwards an acute afterload challenge was applied to all CMTs via an external magnetic field and contractile response was measured immediately. Following the acute afterload challenge the mutant MYBPC3+/− CMTs were divided into two cohorts – Cohort B remained in culture for the next 48 hours with a magnet (solid green line; sustained afterload challenge), while Cohort A was in culture for 48 hours without a magnet (dashed green line; control group)

Functional Assessments of CMTs:

MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs were further incubated for 48 hours without ROCK-inhibitor in a spectrum of afterload conditions. Initial functional testing was performed at 96 hours after seeding (see Supplement and Figure S3) as prior studies have shown that microtissues of this scale and format compact and rhythmically contract with consistent frequency, contractile duration, and active tension by 3 days after seeding16,18. At initial testing, both MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs were subjected to an acute afterload challenge by addition of a 168.6 mT annular magnet around each array, stiffening the cantilevers (Figure 2B), and functional testing was repeated. From here, MYBPC3+/− CMTs were divided into two cohorts: Cohort A had the magnet removed and was incubated for a further 48 hours, while Cohort B was incubated for the 48 hours with the magnet to simulate a sustained afterload challenge. At 144 hours, all MYBPC3+/− CMTs had repeat functional testing. The measured spring constants for each pair of cantilevers restraining each individual CMT was averaged and used to calculate both passive and active force development using Hooke's Law. These spring constants were also employed for a prespecified analysis of the effects of different magnitudes of in vitro afterload upon contractile function. The three sequential testing protocols and the number of tissues assigned to each experimental group are summarized in Figure 2C. The metrics examined in all cases included passive force, active force, contraction velocity, relaxation velocity, work (defined as active force x displacement), and power (defined as active work x contraction velocity) (see Supplement).

Results:

Characterization of MYBPC3 cell lines in 2D culture:

As a preliminary exploration of the mechanoresponses of a pathogenic HCM-causing mutation (p.R943x, MYBPC3+/−), we cultured the Hu-iPSC-CMs from this cell line and the corrected cell line (MYBPC3+/+(ed)) on a 2D MRE that is capable of tuning substrate stiffness to mimic either the normal or pathologic stiffness of the myocardium16. As shown in Figure 3, after two days of culture on soft substrate, the MYBPC3+/− Hu-iPSC-CMs were significantly larger than the MYBPC3+/+(ed) Hu-iPSC-CMs (3932 vs. 2651 μm2, p<0.0001). After two further days of culture on a stiffened substrate (with the addition of the 95 mT cylindrical magnet), both MYBPC3+/+(ed) and MYBPC3+/− Hu-iPSC-CMs manifested significant increases in cell area (4279 vs. 2651 μm2, p<0.0001 and 4278 vs. 3932 μm2, p<0.05, respectively). These results identify differences in mechanoresponsiveness between the MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) cell lines of our HCM model.

Fig. 3.

Cell Area of iPS-cardiomyocytes cultured on soft or stiff substrates. (A) Representative images MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) cultured on soft (top, without magnet) or stiff (bottom, with magnet) MREs showing alpha-Actinin2 (green) and Dapi (blue). (B) iPS-CM cell area measured after 48 hours of culture on soft or stiff substrates, showing the MYBPC3+/− variant had significantly greater cell area under soft conditions (Two-tailed t-tests were performed, significance is indicated by ****p<0.0001. scale = 50μm)

Baseline contractility of MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) tissues:

Owing to variability in the fabrication of the cantilevers, their baseline (without magnet) stiffness varied. We exploited this variability by studying the contractility of our CMT after they had matured for 96 hours across a spectrum of cantilever stiffness / afterload conditions (without magnet). For this analysis, we divided the MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs into four cantilever stiffness groups: <0.4 N/m, 0.4-0.6 N/m, 0.6-0.8 N/m, and >0.8 N/m. As seen in Table 1, 71 CMTs were analyzed at 96 hours (36 MYBPC3+/−, 35 MYBPC3+/+(ed)). Both MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs showed similar, stepwise increases in passive force with increasing cantilever stiffness (afterload). However, MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs exhibited differences in active contractility as a function of in vitro afterload. MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs exhibited peak contractility on cantilevers with a stiffness of 0.4-0.6 N/m with significant declines in active force, work, power, contraction velocity and relaxation velocity at higher in vitro afterloads. In contrast, MYBPC3+/− CMTs demonstrated peak contractility at higher afterloads with their peak active force, work, power, contraction velocity, and relaxation velocity at 0.6-0.8 N/m, and small nonsignificant reductions at higher in vitro afterloads. As seen in Table 1 and Figure 4, in low afterload conditions (<0.4 N/m), MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs yielded greater contractility than MYBPC3+/− CMTs whereas in higher afterload conditions (>0.6 N/m), MYBPC3+/− CMTs manifested substantially greater contractility than MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs. This was evident in active force, work, power, contraction velocity, relaxation velocity. MYBPC3+/− CMTs displayed significantly greater maximum contractility in all metrics (active force, work, contraction velocity, and relaxation velocity), with no difference in passive force. We find similar conclusions when analyzing stiffness as a continuous variable, with the heterozygous MYBPC3+/− variants showing a positive correlation between cantilever stiffness and every contractility metric (active force, work, power, contraction velocity, relaxation velocity) while the MYBPC3+/+(ed) isogenic control displayed negative correlations (Figure S4).

Table 1. MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) at 96 Hours.

Both MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs showed stepwise, and similar, increases in passive force with increasing cantilever stiffness. MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs (+/+(ed)) exhibited maximum contractility at 0.4-0.6 N/m with declines in contractility in higher afterload conditions. In contrast, MYBPC3+/− CMTs (+/−) displayed maximum contractility at 0.6-0.8 N/m, with insignificant reductions at higher in vitro afterloads. MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs had greater contractility in low afterload conditions, but MYBPC3+/− CMTs had greater contractility in higher afterload conditions. Data displayed as mean ± SEM.

| <0.4 N/m | 0.4-0.6 N/m | 0.6-0.8 N/m | >0.8 N/m | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+(ed) (n=6) |

+/− (n=7) |

p-value | +/+(ed) (n=12) |

+/− (n=7) |

p-value | +/+(ed) (n=8) |

+/− (n=15) |

p-value | +/+(ed) (n=9) |

+/− (n=7) |

p-value | |

| Cantilever Stiffness (N/m) | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.76 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 0.82 |

| Passive Force (μN) | 10.27 ± 1.46 | 14.17 ± 1.79 | 0.13 | 23.23 ± 0.90 | 22.48 ± 3.18 | 0.83 | 31.02 ± 1.59 | 28.11 ± 2.16 | 0.37 | 36.19 ± 5.83 | 27.38 ± 2.78 | 0.20 |

| Active Force (μN) | 1.44 ± 0.22 | 0.84 ± 0.13 | <0.05 | 2.80 ± 0.30 | 2.04 ± 0.35 | 0.13 | 1.12 ± 0.40 | 6.82 ± 0.82 | <0.0001 | 1.76 ± 0.36 | 6.38 ± 1.39 | <0.05 |

| Work (nJ) | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 0.002 ± 0.0007 | <0.05 | 0.018 ± 0.004 | 0.010 ± 0.003 | 0.15 | 0.004 ± 0.002 | 0.078 ± 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.061 ± 0.025 | 0.07 |

| Contraction Velocity (μm/s) | 71.65 ± 14.43 | 32.16 ± 5.40 | <0.05 | 81.81 ± 7.63 | 56.04 ± 9.98 | 0.06 | 23.96 ± 8.09 | 134.63 ± 16.91 | <0.0001 | 28.07 ± 5.04 | 102.39 ± 23.85 | <0.05 |

| Relaxation Velocity (μm/s) | 32.59 ± 8.47 | 24.85 ± 12.77 | 0.64 | 27.57 ± 2.56 | 30.90 ± 8.99 | 0.73 | 11.78 ± 4.25 | 88.34 ± 10.08 | <0.0001 | 13.01 ± 2.92 | 57.89 ± 13.26 | <0.05 |

| Power (nW) | 0.116 ± 0.032 | 0.031 ± 0.010 | <0.05 | 0.252 ± 0.051 | 0.134 ± 0.044 | 0.14 | 0.049 ± 0.023 | 1.095 ± 0.224 | <0.001 | 0.064 ± 0.018 | 0.844 ± 0.369 | 0.08 |

Fig. 4.

Comparison of MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs grouped in <0.4 N/m, 0.4-0.6 N/m, 0.6-0.8 N/m, and >0.8 N/m conditions. (A) MYBPC3+/− displayed decreased active force in low afterload conditions (<0.6 N/m) but increased active force in greater afterload conditions (>0.6 N/m). (B) Both MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs showed stepwise increases in passive force with increasing afterload but did not have significant differences between them. (C) MYBPC3+/− displayed decreased work in low afterload conditions (<0.6 N/m) but increased work in greater afterload conditions (>0.6 N/m). (D) MYBPC3+/− displayed decreased contraction velocity in low afterload conditions (<0.6 N/m) but increased contraction velocity in greater afterload conditions (>0.6 N/m). (E) MYBPC3+/− displayed similar relaxation velocity in low afterload conditions (<0.6 N/m) but increased relaxation velocity in greater afterload conditions (>0.6 N/m). (F) MYBPC3+/− displayed decreased power in low afterload conditions (<0.6 N/m) but increased power in greater afterload conditions (>0.6 N/m) (Two-tailed t-tests were performed, significance is indicated by ****: p<0.0001, ***: p<0.001, **: p<0.01, and *: p<0.05)

When peak velocity is normalized per μN of active force, the MYBPC3+/− CMTs have a marginally slower contraction velocity and marginally faster relaxation velocity compared to MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs when stratified by stiffness group, but these differences are not statistically significant (Table S1). Baseline tissue length was similar between all loading conditions in the heterozygous MYBPC3 variant CMTs. In the MYBPC3+/+(ed), the 0.4-0.6 N/m group had a lower baseline length (less preload) than the <0.4 N/m group and had a similar baseline length to the other groups. The baseline tissue length was not significantly different between cell lines when stratified by loading condition (Table S2).

Acute Increase in Afterload Reveals Differences in Contractile Reserve:

After 96 hours of maturation without a magnet, we subjected a subset of the CMTs (26 MYBPC3+/− and 16 MYBPC3+/+(ed)) to an acute afterload challenge via application of a magnet, as shown in Figure 5 and Table S3. We had an absolute increase in cantilever stiffness of approximately 0.25 N/m with the application of the magnet, which translates to a ~25-50% relative increase depending on the baseline stiffness. With an acute afterload challenge, MYBPC3+/− CMTs showed significant increases in passive force, active force, work, and power, whereas MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs only showed a significant increase in passive force, suggesting that MYBPC3+/− CMTs had greater contractile reserve, defined as the ability to increase contractility in the presence of an external biochemical or biomechanical stress. Recognizing that CMTs matured at different cantilever stiffnesses had differences in functional characteristics at 96 hours, a subgroup analysis of the acute afterload challenge (Table S4) was done based on the baseline cantilever stiffness (without magnet) upon which the CMTs had been matured (<0.6 N/m, 0.6-0.8 N/m, and >0.8 N/m). In CMTs matured on <0.6 N/m stiffness, the acute afterload challenge induced significant increases in passive and active force with a nonsignificant trend towards increased work and power. In CMTs matured on 0.6-0.8 N/m stiffness, the acute afterload challenge induced significant increases in active force and work (with a trend towards increased power). However, CMTs cultured on cantilevers with >0.8 N/m exhibited no increases in active force, work, or power with the acute afterload challenge. This suggests that the hypercontractility and/or contractile reserve in CMTs may be influenced by their baseline afterload conditions.

Fig. 5.

Response of MYBPC3+/− (n=27) and MYBPC3+/+(ed) (n=16) CMTs to an acute increase in afterload. (A) Both cell lines demonstrated increases in passive force, but only MYBPC3+/− CMTs displayed increases in active force. (B) Only MYBPC3+/− CMTs displayed increases in work. (C) There were no changes in contraction or relaxation velocity in either cell line. (D) Only MYBPC3+/− CMTs displayed increases in power (Paired t-tests were performed, significant differences are indicated by ****: p<0.0001, ***: p<0.001, **: p<0.01, and *: p<0.05)

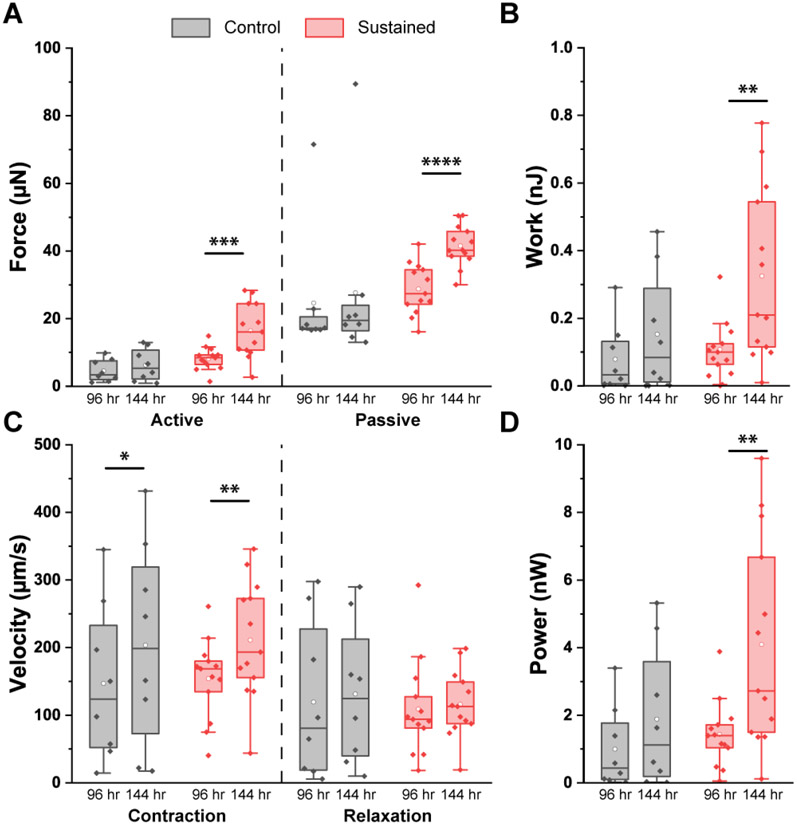

Sustained Increase in Afterload Augments Passive Force in MYBPC3+/− CMTs:

We next examined how MYBPC3+/− CMTs and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs responded to sustained increments of afterload. After the acute afterload challenge, a total of 21 MYBPC3+/− CMTs were divided into two cohorts: Cohort A was incubated without a magnet for the next 48 hours (n=8), and Cohort B was incubated with a magnet for those 48 hours (n=13). Thus, Cohort A CMTs had been matured without a magnet from 0 to 96 hours and continued to be incubated without a magnet from 96 to 144 hours. As shown in Table S5 and Figure 6, at 144 hours after initial seeding, these MYBPC3+/− CMTs incubated in stable in vitro afterload (without magnet) demonstrated a moderate but statistically significant increase in contraction velocity with nonsignificant trends towards increased active force, work, and power. Cohort B CMTs had been matured without a magnet from 0 to 96 hours, and then were incubated with a sustained increment of afterload (with magnet) from 96 to 144 hours. At 144 hours, these MYBPC3+/− CMTs exhibited marked increases in active force, work, contraction velocity, and power. However, there was also a significant increase in passive force suggesting that the sustained increment in afterload may have increased tissue stiffness. Compared with MYBPC3+/− CMTs incubated in static afterload conditions (Cohort A), MYBPC3+/− CMTs incubated with a sustained increment in afterload (Cohort B) displayed significantly greater active force at 144 hours with a trend towards increased power and nonsignificant increase in work. However, there were no differences in passive force, contraction velocity, or relaxation velocity.

Fig. 6.

Response of MYBPC3+/− CMTs to a sustained increase in afterload (n=13) vs. static conditions (n=8). (A) There were increases in active and passive force only with a sustained increase in afterload. (B) There was an increase in work only with a sustained increase in afterload. (C) There were increases in contraction velocity with and without a sustained increase in afterload. However, relaxation velocity did not significantly change in either group. (D) There was an increase in power only with a sustained increase in afterload (Paired t-tests were performed, significant is indicated by ****: p<0.0001, ***: p<0.001, **: p<0.01, and *: p<0.05)

Discussion:

Accelerating progress in the capacity to define the genetic causes of cardiomyopathies, combined with advances in cellular engineering and gene editing, provides opportunities to model and explore mechanisms contributing to cardiac disease progression. Because tethered, 3-dimensional tissues promote the organization and maturation of cardiomyocytes, they show particular promise for elucidating how pathologic genetic mutations cause myocardial dysfunction and remodeling. However, many basic and translational studies are constrained by inadequate preclinical models which do not allow for precise control over biomechanical and biochemical factors. Specifically, those models fail to extrinsically control mechanical preload and afterload, which are essential features of cardiac physiology. Here, we present an approach to mimic dynamic changes through an in vitro model with the ability to bidirectionally modulate afterload, which can create physiologic conditioning and emulate pathologic biomechanical stresses. We created tunable afterload by incorporating the MRE material into the fabrication of cantilevers which allowed for easy control of cantilever stiffness using magnets. We employed this CMT model with variable and tunable in vitro afterload to probe the interactions between a known HCM-causing MYBPC3+/− mutation and altered mechanical input at different stages of tissue development. For these experiments, we were blinded as to which cell line represented the disease state and were later unblinded following data analysis.

Exploiting the variability in the baseline stiffness of the MRE cantilevers and our ability to measure cantilever stiffness precisely, we demonstrate that CMTs comprised of identical cellular inputs exhibit afterload-dependent differences in their contractile performance. The impact of altered afterload during the maturation of CMTs was particularly evident in the MYBPC3+/− CMTs, in which increased in vitro afterload induced striking increases in active force, work and power that was not apparent in MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs in which the pathologic MYBPC3 variant was corrected. Conversely, the MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs only exhibited superior contractility compared with MYBPC3+/− under very low in vitro afterload conditions. While we were not able to precisely control preload, we were able to measure baseline tissue lengths and static loading for all tissues and found that tissues in the loading conditions producing the greatest force production had a similar or lower level of preload. Thus increases in active force, work and power in MYBPC3+/− CMTs were not simply a consequence of increases in preload via the Frank-Starling mechanism. These results extend prior research in non-HCM iPSC lines that have shown moderate levels of afterload promote maximum contractility in engineered cardiac tissues10 by demonstrating that a sarcomeric protein variant associated with HCM can markedly potentiate the short-term hypercontractility induced by increased afterload.

Beyond the effects of afterload conditioning during initial tissue maturation, we observed that the HCM-associated variants are associated with markedly potentiated responses to secondary increments in afterload, both acute and sustained. In response to acutely increased in vitro afterload via magnet application, the MYBPC3+/− CMTs exhibited significantly enhanced contractile work and power compared with MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs along with proportionately smaller, but significant, increases in active force. Subgroup analysis indicated that the degree of afterload conditioning during maturation affected the magnitude of the acute contractile reserve, with the MYBPC3+/− CMTs cultured on cantilevers with baseline stiffness in the 0.6-0.8 N/m range exhibiting the greatest increments in contractility. Finally, the MYBPC3+/− CMTs exposed to sustained increments of in vitro afterload (via sustained magnet application) demonstrated further increments in active force, work, power, and contraction velocity compared with MYBPC3+/− CMTs maintained on cantilevers with unchanged stiffness. This extends prior work examining the effect of afterload on cardiomyocytes, as it has been shown in 2D culture that 48 hours of increased substrate stiffness is sufficient to induce changes in cardiomyocyte contractility, contraction and relaxation mechanics, calcium handling, and viscoelasticity22. Together, these findings indicate that cardiomyocytes possessing a genetic variant predisposing to increased force generation have augmented contractile responses to extrinsic biomechanical stress.

The present studies help reconcile prior conflicting reports modeling the impact of a known human MYBPC3+/− variant on contractility. Clinical evidence from patients with HCM suggest that MYBPC3+/− variants often produce a hypercontractile phenotype in vivo3,23. Likewise, Stohr et al. have reported enhanced contractility in engineered tissues fabricated with cardiomyocytes derived from mice expressing an analogue of a human MYBPC3+/− variant24. Conversely, studies employing isolated cardiomyocytes studied under conditions of extremely low afterload have indicated that MYBPC3+/− variants result in a normal or hypocontractile phenotype17,25-27. From this perspective, our finding that extrinsic biomechanical loading potentiates, while low loading attenuates, contractility of human MYBPC3+/− CMTs helps unify these seemingly conflicting reports. A notable exception is a study by Ma et al. that homozygous MYBPC3−/− mutants exhibited similar contractility relative to control in low afterload conditions but are hypocontractile in high afterload conditions28 within filamentous 3D matrices. Given reports of in vivo systolic dysfunction in homozygous MYBPC3−/− mice29, our contrasting finding that high in vitro afterload augments contractility metrics likely reflects key differences in genotype (heterozygous vs. homozygous) and/or model-related differences (culture on cantilever vs. within filamentous matrices).

Beyond the genotype of the tissue and model-related differences, prior studies in macro engineered heart tissues suggest that changes in afterload may also impact contractility depending on the direction, magnitude, and rate of afterload change. Hirt et. al used metal posts to brace hollow silicone posts upon which they grew EHTs made of wild-type cardiomyocytes12. They found that tissues cultured in increased afterload conditions exhibited a significant decrease in contractility when tested immediately after the metal brace was removed, whereas we exerted an acute increase in afterload. Another notable difference between our study and Hirt et. al was the magnitude of afterload change imparted by the metal braces (12-fold compared to our 25-50% increase). In fact, Rodriguez et. al used a magnetic version of this metal brace system to show the disparate effects of large vs. small acute increases in afterload13. They demonstrated that stepwise modest increases in afterload (largest was a relative increase of 50%) causes stepwise increases in contractility (including velocity kinetics) whereas a large absolute increases in afterload results in lower contractility. Notably, they were also able to demonstrate changes in contractility within 24 hours, suggesting that microtissues are able to respond to environmental stresses in relatively short time frames. While we do show that our heterozygous MYBPC3 variants display a contractile reserve that can be elicited with modest increases in afterload, our wild type microtissues did not. This may suggest other parameters play significant roles such as the magnitude of afterload change relative to tissue construct size.

The faster relaxation velocities in the MYBPC3+/− CMTs, especially at higher loads, is somewhat unexpected given that on an organ level, patients with HCM tend to have slower relaxation kinetics. When peak relaxation velocity was normalized per unit of active force, the differences between MYBPC3+/− and MYBPC3+/+(ed) CMTs were nonsignificant. Some studies have shown MYBPC3+/− cardiomyocytes to be hypercontractile but have slower relaxation kinetics as a 2D monolayer during traction force microscopy experiments on soft polyacrylamide gel (7.9 kPa) that was similar in stiffness to our soft substrate in 2D analysis (9.3 kPa)30. However, a key difference in the functional assessments of this variant was the use of a monolayer on a 2D substrate in the prior report vs. the 3D format employed in our studies. In both 2D and 3D CMT models, we observe significant interplay between external loading and genotype in determining the morphology and contractility of the MYBPC3+/− cardiomyocytes. With regards to the interplay of loading conditions and relaxation velocity, our results are in accordance with those shown by Rodriguez et. al who also demonstrated that small increases in afterload caused modest increases in relaxation velocity13.

In our two-dimensional culture studies, the increased cell spreading of MYBPC3+/− Hu-iPSC-CMs compared with isogenic control further attests to the interplay between this HCM genotype and responses to biomechanical stress. While both cell lines exhibited increased spreading in response to an increase in culture surface stiffness to 50 kPa, the MYBPC3+/− cardiomyocytes displayed significantly greater spreading on the soft 10 kPa surface. These findings suggest that the intrinsic features of the HCM variant predispose to hypertrophy even in the absence of extrinsic biomechanical conditions that would promote hypertrophy. While differences in cell spreading do not necessary imply hypertrophy, it is tempting to speculate that these in vitro findings are analogous to the in vivo hypertrophy associated with HCM in the absence of hypertension or other increases in afterload.

Our findings have several implications for future modeling of genetic cardiomyopathies caused by sarcomeric protein variants using iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. First, the interplay between extrinsic biomechanical load and the functional impact of the human MYBPC3+/− variant suggest that it is desirable to employ biomechanically loaded 3D models that can reflect the in vitro biomechanical context experienced by these cells and relevant controls. The ability to study engineered heart tissues across a range of in vitro afterloads and characterize their responses to acute and sustained biomechanical stress is also likely to provide further insight into the functional impact of known mutations and the many variants of uncertain significance which emerge during genetic testing of patients with cardiomyopathies. Finally, the finding that increased biomechanical load could favor further hypercontractility could provide clues to mechanisms of disease progression in patients with HCM. For example, emergence of mild left ventricular outflow tract obstruction or hypertension could predispose to greater hypercontractility, worsening of the outflow tract gradient, and/or worsening of diastolic dysfunction and lead to worse symptoms and increased risk of demand ischemia/scarring. Furthermore, a retrospective analysis of HCM patients has shown that presence of hypertension conferred an increased risk of apical hypertrophy and mid-ventricular obstruction, with a trend towards decreased 5-year survival31.

Limitations:

Despite our success in revealing interactions between extrinsic biomechanical inputs and a sarcomeric protein variant associated with HCM, there are several limitations that merit consideration. We only examined a single variant and thus cannot generalize our findings to other sarcomeric protein mutations. Our inability to precisely control baseline and magnetically-actuated cantilever stiffness made us dependent on measuring the stiffness of every cantilever. Though our posthoc subdivisions of in vitro afterload - selected to produce relatively balanced numbers of tissues in each range - are admittedly arbitrary, the overall afterload-dependence of functional responses would likely have emerged if alternative cutoffs were selected. In addition, the secondary analysis when using afterload as a continuous variable corroborates our findings, increasing the validity. We did not control the baseline tissue length (in vitro preload) and assessments across a range of preloads and afterloads would represent an advance over the current approach. While we were unable to measure sarcomere length in these multicellular, 3D preparations, we found no correlation between contractility and baseline tissue length or static tension. Thus, the changes in contractility were likely due to differences in genotype (MYBPC3+/− vs. MYBPC3+/+(ed)) and afterload, not simply due to differences in preload. We did not control for pacing frequency during incubation, and it has been previously shown that cyclical beating can impact contractility32. Nevertheless, contractile characterization was performed at a standardized stimulation frequency of 1 Hz. In addition, geometric differences between our CMT platform and in vivo myocardium make it difficult to relate our experimental in vitro afterload to the afterload experienced by the intact heart in vivo. Assessment of intracellular [Ca2+], measurement of tissue cross-sectional thickness, or characterizations of proteomic profiles associated with alternative contractile responses to different degrees of biomechanical stress were not technically feasible in this iteration of our model system. In the absence of cross-sectional areas, we cannot exclude the possibility that tissue hypertrophy contributed to increased active force metrics. Of potential relevance in this context are prior studies comparing a different hypercontractile MYBPC3 variant (R403Q+/−) to an isogenic control in which the two cell lines yielded similar cross-sectional area when studied in a 3D cardiac microtissue model33. However, these studies do not preclude the possibility of differential cross-sectional growth under conditions of increased in vitro afterload. Certainly, the observed differences in contractility and contractile reserve in the present studies suggest the potential value of further mechanistic explorations.

In summary, our application of a novel CMT platform capable of producing varied and tunable levels of in vitro afterload reveals that extrinsic biomechanical challenges potentiate genetically-driven intrinsic increases in contractility. These findings demonstrate the value of advanced engineered tissue models with tunable afterload for demonstrating the functional impact of known pathogenic and potentially pathogenic sarcomeric mutations. Because adaptations to acute and sustained changes in hemodynamics are a central feature of myocardial biology, engineered heart tissue models capable of manipulating in vitro loading conditions have broad utility for disease modeling beyond genetic cardiomyopathies.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This research was supported by a grant from the State of Pennsylvania Department of Health, with additional support from NIH/NCATS award number TL1TR001880 to A.R. and C.E.L.; the Sidney Pestka M’61 Term Fellowship to A.R.; support from NIH T32-HL007843 to B.W.L.; American Heart Association 19CDA34770040 to C.K.L.; NIH/NHLBI grant R01 HL126527 and R01 HL130020 to J.C.W.; the Center for Engineering Mechanobiology (CEMB) under grant agreement CMMI: 15-48571 and a Provost Postdoctoral Fellowship to A.I.B.; and NIH/NHLBI grant R01-HL149891, the Leducq Foundation TNE ID#673168 and the Gordon and Llura Gund Family Fund to K.B.M.

Abbreviations:

- CMT

Cardiac microtissues

- HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Hu-iPSC-FBs

Human-induced pluripotent stem cell fibroblasts

- Hu-iPSC-CMs

Human-induced pluripotent stem cell cardiomyocytes

- iPSC

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- MRE

Magnetorheological elastomer

- MYPBC3

Myosin binding protein C

- PDMS

Polydimethylsiloxane

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Kenneth Margulies receives consulting fees for serving on the advisory boards for Bristol-Myers-Squibb (myosin inhibitors) and Pfizer, Inc. (heart failure).

Human Subjects / Informed Consent / Animal Subjects Statement:

While no human studies were carried out by the authors for this article, we utilized two cell lines of Hu-iPSC-CMs from the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute that were employed in previous studies17. As described in Seeger et. al, the protocol for induced pluripotent stem cell generation and cardiomyocyte differentiation were in accordance with the ethical standards of and approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Stem Cell Research Oversight (SCRO) Committee, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. iPSC lines were obtained from patients with informed consent17. All procedures followed of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national). Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study. No animal studies were carried out.

References:

- 1.Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT, Bild DE. Prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in a General Population of Young Adults: Echocardiographic Analysis of 4111 Subjects in the CARDIA Study. Circulation. 1995;92(4):785–789. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.92.4.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke MA, Cook SA, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Clinical and Mechanistic Insights Into the Genetics of Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(25):2871–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toepfer CN, Wakimoto H, Garfinkel AC, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in MYBPC3 dysregulate myosin. 2020;11(476). doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat1199.Hypertrophic [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis J, Davis LC, Correll RN, et al. A Tension-Based Model Distinguishes Hypertrophic versus Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Cell. 2016;165(5):1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green EM, Wakimoto H, Anderson RL, et al. Heart disease: A small-molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility suppresses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Science. 2016;351(6273):617–621. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maron MS, Rowin EJ, Olivotto I, et al. Contemporary Natural History and Management of Nonobstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(12):1399–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maron BJ. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. The Lancet. 1997;350:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marian AJ, Braunwald E. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Genetics, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and therapy. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):749–770. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Repetti GG, Kim Y, Pereira AC, et al. Discordant clinical features of identical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(10):3–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021717118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonard A, Bertero A, Powers JD, et al. Afterload promotes maturation of human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes in engineered heart tissues. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;118(March):147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Truitt R, Mu A, Corbin EA, et al. Increased Afterload Augments Sunitinib-Induced Cardiotoxicity in an Engineered Cardiac Microtissue Model. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;3(2):265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirt MN, Sörensen NA, Bartholdt LM, et al. Increased afterload induces pathological cardiac hypertrophy: a new in vitro model. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107(6):307. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0307-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez ML, Werner TR, Becker B, Eschenhagen T, Hirt MN. A magnetics-based approach for fine-tuning afterload in engineered heart tissues. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2019;5(7):3663–3675. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b01568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang SY, Zhang X, Sun S, et al. Versatile Microfluidic Platforms Enabled by Novel Magnetorheological Elastomer Microactuators. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28(8):1705484. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201705484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Li J, Li W, Du H. A state-of-the-art review on magnetorheological elastomer devices. Smart Mater Struct. 2014;23(12):123001. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/23/12/123001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbin E, Vite A, Peyster EG, et al. Tunable and Reversible Substrate Stiffness Reveals Dynamic Mechanosensitivity of Cardiomyocytes. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(23):20603–20614. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b02446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seeger T, Shrestha R, Lam CK, et al. A premature termination codon mutation in MYBPC3 causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy via chronic activation of nonsense-mediated decay. Circulation. 2019;139(6):799–811. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen CY, Caporizzo MA, Bedi K, et al. Suppression of detyrosinated microtubules improves cardiomyocyte function in human heart failure. Nat Med. 2018;24(8):1225–1233. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0046-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legant WR, Pathak A, Yang MT, Deshpande VS, McMeeking RM, Chen CS. Microfabricated tissue gauges to measure and manipulate forces from 3D microtissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(25):10097–10102. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(83)90280-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boudou T, Legant WR, Mu A, et al. A Microfabricated Platform to Measure and Manipulate the Mechanics of Engineered Cardiac Microtissues. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18(9-10):910–919. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krick BA, Vail JR, Persson BNJ, Sawyer WG. Optical in situ micro tribometer for analysis of real contact area for contact mechanics, adhesion, and sliding experiments. Tribol Lett. 2012;45(1):185–194. doi: 10.1007/s11249-011-9870-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vite A, Caporizzo MA, Corbin EA, et al. Extracellular stiffness induces contractile dysfunction in adult cardiomyocytes via cell-autonomous and microtubule-dependent mechanisms. Basic Res Cardiol. 2022;117(1):41. doi: 10.1007/s00395-022-00952-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viswanathan SK, Sanders HK, McNamara JW, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy clinical phenotype is independent of gene mutation and mutation dosage. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stöhr A, Friedrich FW, Flenner F, et al. Contractile abnormalities and altered drug response in engineered heart tissue from Mybpc3-targeted knock-in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;63:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris SP, Bartley CR, Hacker TA, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cardiac myosin binding protein-C knockout mice. Circ Res. 2002;90(5):594–601. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000012222.70819.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Dijk SJ, Boontje NM, Heymans MW, et al. Preserved cross-bridge kinetics in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with MYBPC3 mutations. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466(8):1619–1633. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1391-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birket MJ, Ribeiro MC, Kosmidis G, et al. Contractile Defect Caused by Mutation in MYBPC3 Revealed under Conditions Optimized for Human PSC-Cardiomyocyte Function. Cell Rep. 2015;13(4):733–745. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Z, Huebsch N, Koo S, et al. Contractile deficits in engineered cardiac microtissues as a result of MYBPC3 deficiency and mechanical overload. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2(12):955–967. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0280-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Judge D, Neamatalla H, Norris R, et al. Targeted Mybpc3 Knock-Out Mice with Cardiac Hypertrophy Exhibit Structural Mitral Valve Abnormalities. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2015;2(2):48–65. doi: 10.3390/jcdd2020048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toepfer CN, Sharma A, Cicconet M, et al. SarcTrack. Circ Res. 2019;124(8):1172–1183. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo Q, Chen J, Zhang T, Tang X, Yu B. Retrospective analysis of clinical phenotype and prognosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy complicated with hypertension. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57230-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang N, Stauffer F, Simona BR, et al. Multifunctional 3D electrode platform for real-time in situ monitoring and stimulation of cardiac tissues. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;112(April):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2018.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohn R, Thakar K, Lowe A, et al. A Contraction Stress Model of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy due to Sarcomere Mutations. Stem Cell Rep. 2019;12(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.