Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

NicoBloc® is a viscous fluid applied to the cigarette filter designed to block tar and nicotine. This novel and understudied smoking cessation device presents a non-pharmacological means for smokers to gradually reduce nicotine and tar content while continuing to smoke their preferred brand of cigarette. This pilot study aimed to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of NicoBloc® as compared to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT; nicotine lozenge).

METHODS:

A community sample of predominately Black smokers (N = 45; 66.7% Black) were randomized to receive NicoBloc® or nicotine lozenge. Both groups engaged in four weeks of smoking cessation therapy followed by two months of independent usage with monthly check-ins to assess medication adherence. The intervention lasted 12 weeks and the study concluded with a one-month post-intervention follow-up visit (Week 16).

RESULTS:

NicoBloc® was comparable to nicotine lozenge in smoking reduction, feasibility, symptom side effects, and reported acceptability at Week 16. Participants in the lozenge group endorsed higher treatment satisfaction ratings during the intervention and lower cigarette dependence. Adherence to NicoBloc® was superior throughout the study.

CONCLUSION:

NicoBloc® was feasible and acceptable to community smokers. NicoBloc® presents a unique, non-pharmacological intervention. Future research is needed to examine whether this intervention may be most effective in subpopulations where pharmacological approaches are restricted or in combination with established pharmacological methods such as NRT.

Keywords: NicoBloc®, tobacco use, smoking cessation, nicotine replacement therapy

1. Introduction

Tobacco use is the number one preventable cause of disease, death, and disability in the United States. 1 Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) is the most widely used approach for smoking cessation as it alleviates withdrawal symptoms and allows for a gradual decrease in tobacco dependence. 2 Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of NRT as a smoking cessation tool, with some studies reporting a 50–60% increase in the rate of long-term quitting. 2,3 over no pharmacotherapy. The nicotine lozenge is an extensively used NRT product that has exhibited effectiveness for both low- and high-dependence smokers, as well as for smokers who had previously used pharmacological treatment but failed in their quit attempts. 4 Unfortunately, side effects to NRT products are frequently reported and consequently decrease medication adherence and positive quit outcomes. 5 Research also suggests that smokers’ awareness of these possible side effects decreases their motivation to initiate NRT treatment. 5 A non-pharmacological smoking cessation aid could be of utility for individuals who suffer from side effects or for smokers unwilling to use pharmacotherapies in a quit attempt.

Denicotinized cigarettes and reduced nicotine cigarettes often serve as a non-pharmacological smoking cessation approach since they have highly reduced or close-to-no nicotine content yet maintain the sensory and behavioral aspects associated with regular smoking. 6 In theory, continued use of these types of cigarettes eliminates or greatly diminishes the reinforcing effects of nicotine and subsequently breaks the conditioned reinforcement of smoking-related behaviors. 7 The utility of denicotinized or reduced nicotine cigarettes as an independent smoking cessation aid is largely inconclusive. Though several studies have demonstrated these products’ effectiveness in reducing cigarette consumption over time without compensatory smoking behavior, 8–10 others have noted maintained behavioral reinforcement and similar consumption to conventional cigarettes despite the reduced nicotine content and lower satisfaction ratings. 6,11

NicoBloc® is a novel non-pharmacological smoking cessation product made with natural, FDA-approved food-grade ingredients (e.g., corn syrup and citric acid). It has also been referred to commercially as “Accu Drop” or “Take Out.” 12 NicoBloc® acts as a filtration device in the form of a viscous fluid that is placed on the end of a conventional cigarette by making a small indentation in the filter to place the drop before use. 13 In machine testing of NicoBloc® at two separate labs, one NicoBloc® drop blocked 27.6–57% of nicotine, two drops blocked 75.6–79.8%, and three drops, 84.8–88.6%.14,15 Similarly, when examining tar, one NicoBloc® drop blocked 23.6–52.8%, two drops blocked 43.1–74.2% and three drops, 83.8%.14,15 Thus, by progressively increasing the number of drops, users can prevent much of the tar and nicotine associated with smoking. 16 Compared to other smoking cessation products, NicoBloc® has some notable potential advantages. For one, no known side effects have been reported in any previous trials, 12,16 and it does not contain any psychoactive substances. Since NicoBloc® permits continued use of a persons’ own brand cigarettes, it does not require smokers to quit with a “cold turkey” approach or to switch to brands. 17 Additionally, with NicoBloc® being available over the counter, there are fewer barriers to access than with pharmacological cessation aids such as varenicline or bupropion and cessation aids requiring prescriptions such as a nicotine inhaler or nasal spray. The use of NicoBloc® allows for gradual reduction in smoking by reducing nicotine exposure through “nicotine fading,” as opposed to NRT products which seek to replace nicotine from cigarettes and then taper nicotine exposure over 8–10 weeks. Considering these benefits, NicoBloc® could provide a feasible, acceptable, and effective non-pharmacological approach to smoking cessation.

The current study compared NicoBloc® to nicotine lozenge as both can be used sporadically, even though they have different mechanisms of action (nicotine blocking vs. nicotine replacement). Participants were randomized into one of two groups (NicoBloc® or nicotine lozenge) and engaged in four weeks of a behavioral intervention, followed by two check-in sessions at 8 and 12 weeks to assess medication adherence as well as a final one-month post-intervention follow-up session (Week 16). To evaluate feasibility, we expected that a screening rate of 10–15 participants and enrollment rate of approximately 5 participants per month would be sufficient to support a future larger clinical trial and would facilitate adherence to study procedures. Regarding acceptability, we expected retention rates to be consistent with the smoking cessation research literature (approximately 70–75%)18 and treatment group equivalence in attrition. Finally, we hypothesized that NicoBloc® participants would report similar levels of treatment satisfaction and positive expectancies for both cessation treatments.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from a community sample via study flyers that were distributed around the metropolitan areas of Birmingham, Alabama. The inclusion criteria for participation were as follows: at least 18 years of age, smoking at least five cigarettes per day (CPD) for the last year, living in an unrestricted environment that does not limit smoking, expired carbon monoxide (CO) reading of greater than 8 ppm on the Vitalograph CO monitor, and a positive cotinine test at baseline. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant or nursing, already receiving treatment to quit smoking (i.e., enrolled in a smoking cessation treatment program, using NRT products, or prescribed bupropion or varenicline), known to have a sensitivity to NRT products, experiencing untreated severe angina or heart attack within the last month, unable to provide informed consent due to cognitive impairment or psychiatric instability, using other forms of tobacco products (i.e., electronic cigarettes, little cigars, etc.) exclusively, or were non-English speakers.

2.2. Procedures

After being screened and deemed eligible, participants completed an approximately one-hour baseline appointment during which they provided an expired CO breath test, urine drug screen, pregnancy test (women only), and cotinine test. They also completed assessments through REDCap examining smoking history, previous experience with NRT, and weekly smoking behavior. Participants were randomized 1:1 in REDCap to either the NicoBloc® or the nicotine lozenge group. To ensure an equal distribution of race, sex, and cigarette dependence across groups, a block randomization scheme was utilized.

The study duration spanned four months and included four weeks of smoking cessation behavioral therapy with use of either the NicoBloc® or nicotine lozenges (Weeks 1–4; intervention), two treatment sessions to assess continued medication adherence (Week 8 and Week 12), and a follow-up visit one month after medication discontinuation (Week 16). During each intervention session, participants in both groups began by completing a 30-minute self-report assessment battery. A full description of the measures used in the present study can be found in Table 2. Following this, demonstrations of the proper use of each product were given. Participants in the NicoBloc® group practiced with their own personal cigarettes, which they were instructed to bring to each session, smoking outside of the lab space. Lozenge participants also sampled the product in-session. Throughout intervention sessions, participants were led to discuss their expectations regarding their assigned product. Study personnel then addressed the positive and negative effects of product use with participants, reframing as needed and addressing concerns. Immediately following product usage, participants completed post-session measures.

Table 2.

Session Measures and Operationalization of Smoking Behavior and Product Usage

| Measure | Sessions | Items | Likert Range | Measure Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanford Expectancies in Treatment Scale (SETS) 32 | Baseline; Week 4 – Week 16 | 7 | Strongly disagree – Strongly agree | Assesses positive and negative expectancies regarding fears, perceived efficacy, expected side effects, and treatment outcomes. |

| Treatment Satisfaction Survey | Week 12; Week 16 | 10 | Not at all helpful – Very helpful; Poor – Excellent | This author-constructed measure examines participant’s overall satisfaction regarding the quality of the intervention they received, study personnel, and treatment outcomes. |

| Symptom Side Effects33 | Week 2 – Week 12 | 37 | Not at all – Very much | Assesses common side effects related to NRT usage, nicotine withdrawal, and medication use in general (e.g., headaches, dry mouth, etc.). |

| Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) 34 | Baseline; Week 8 – Week 16 | 6 | - | Assesses various aspects of cigarette dependence and severity of smoking behaviors. |

| Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU) 35 | Week 1 – Week 4 | 10 | Strongly disagree – Strongly agree | Smoking urges were assessed at the beginning (pre-QSU) and conclusion (post-QSU) of active intervention sessions using this measure. |

| Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS) 36 | Baseline; Week 8 – Week 16 | 8 | None – Severe | Assesses withdrawal symptoms such as irritability, sleep disturbance, or restlessness. This was administered at the beginning (pre-MNWS) and end (post-MNWS) of active intervention sessions. |

| Brief Wisconsin Index of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) 27 | Baseline; Week 8 – Week 16 | 37 | Not true of me at all – Extremely true of me | Assesses several domains of smoking including dependence and motives for use. |

| Measure | Sessions | Measure Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes per Day (CPD) | Week 1 – Week 16 | Assed via self-report calendars using the Timeline Follow-back interview (TLFB). 37 These were completed daily by participants and returned to staff at each study visit, updating incomplete entries as needed. |

| Point Prevalence Abstinence | Week 4 – Week 16 | Determined by participant’s self-reported smoking behavior and verified through expired CO assessment. Participants were considered abstinent if they reported smoking no cigarettes the day of or prior to their session and if their CO level was less than 5 ppm. 38,39 |

| NicoBloc® and Nicotine Lozenge Adherence | Week 2 – Week 12 | In the NicoBloc® group, daily adherence was confirmed if participants used the product for 80% of the cigarettes they reported smoking. Daily adherence for the lozenge group was calculated based on the participant having used at least 80% of the recommended minimum dose (8 lozenges) in a day. From these values, an overall adherence rate was calculated and participants that were adherent for 80% or more days of the intervention were coded as adherent, following the conventions of other smoking cessation studies. 19,40 |

After the Week 1 session, participants in the NicoBloc® group were instructed to use 1 drop of the product while participants in the nicotine lozenge group were given 2mg and 4mg quit tubes and asked to try each. Both groups were given enough of their assigned product to last them until the following session. NicoBloc® participants were asked to use one drop of the product with each cigarette and participants using lozenges instructed to follow product recommendations as to the suggested minimum and maximum daily uses as well as suggested frequency of use. At each subsequent intervention session NicoBloc participants were asked to increase the number of drops by units of one until using three drops, which they continued using for the remainder of the study. Participants in the lozenge group were asked to try both 2mg and 4mg doses and report their preference during Week 2. They continued using this dosage of lozenges for the remainder of the study.

During the Week 4 session, all participants were asked to determine a quit date prior to their Week 8 visit. At this time, participants were provided with a list of cognitive-behavioral strategies to support their quit attempt, discussing them at length during this session. All participants were monitored for side effects from Weeks 1–12 and told to refrain from smoking as long as possible prior to each weekly study visit (Weeks 1–4) so as to receive the maximal benefit from use of lozenge or NicoBloc®.

Participants were compensated up to $210 for study participation. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board. We received approval from the FDA for NicoBloc® as an investigational device exemption. This pilot study is registered to ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03720899) and an a priori data analysis plan was determined prior to study completion.

2.3. Data Analytic Approach

Participant screening, baseline eligibility, baseline attendance, study eligibility, and retention rates throughout the study were calculated overall and per time point. Retention rates between groups at each time point and other dichotomized variables such as adherence were assessed using Chi-Square analyses. Participant demographics and baseline smoking characteristics were assessed, and group differences examined using measures of effect size (Cramer’s V and Cohen’s d). Group differences over time were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with all available data (i.e., Intent-To-Treat analyses). GEE results were followed-up with pairwise comparisons when applicable. Measures administered pre- and post-session (QSU and MNWS) were calculated as a change score and included as such in GEE analyses. Pre-session scores were subtracted from post session scores such that negative scores reflect decreases in withdrawal symptoms or smoking urges throughout the session. For measures administered at two or less time points, t-tests were used to examine group differences.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

Forty-five participants were enrolled in this pilot study and randomized to the NicoBloc® (n=21) or nicotine lozenge (n=24) group. Most participants were Black (66.7%; 28.9% White/Caucasian; 4.4% multi-racial) men (71.1%) with a mean age of 49.7 years (SD=10.7).

3.2. Feasibility

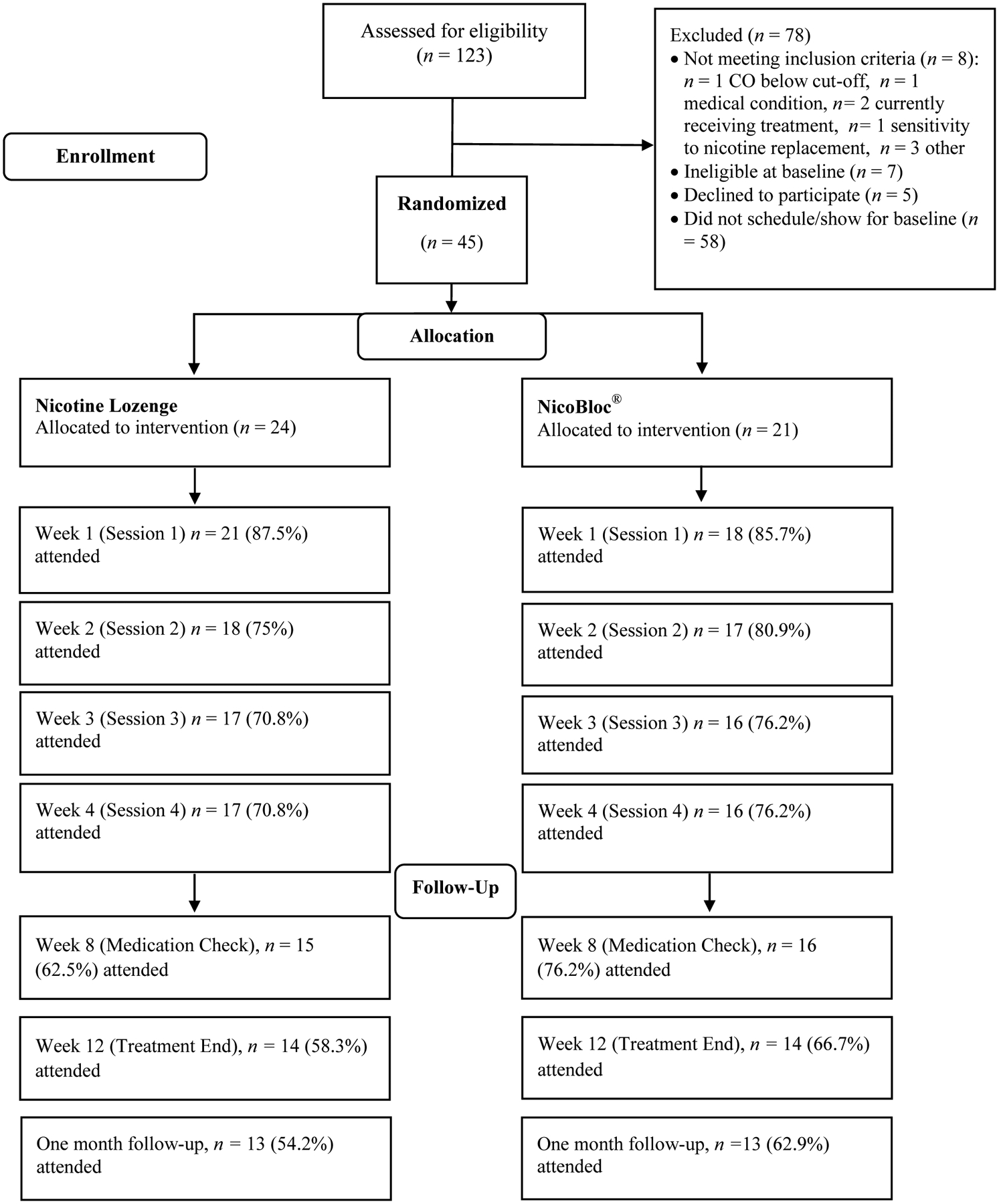

One hundred and twenty-three individuals were screened for the current study over a 9-month period (14 per month) from 03/28/2019 – 1/09/2020. Of those screened, 115 were eligible for study participation, 52 attended a baseline testing session, and 45 were eligible at baseline (enrollment rate of 5 participants per month; see Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram). The overall retention rate at Week 16 was 58%, and there were no differences between the groups in retention at any time point (ps > 0.05).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

3.3. Acceptability

Prior to running acceptability analyses, we examined equivalence across the treatment groups on demographic variables (age, race, gender, and education), CPD, CO level, desire to quit at baseline, and cigarette dependence symptoms at baseline. There were no group differences in these variables (p > 0.05; see Table 1). Further, between those participants who indicated that they were thinking of quitting within the next 30 days (n=29) and those who did not (n=16), there were no differences in product adherence or CPD (ps > 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographics and Smoking Characteristics of Treatment Sample at Baseline

| Overall (n=45) | NicoBloc (n=21) | Lozenge (n=24) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/n | SD/% | M/n | SD/% | M/n | SD/% | Cramer’s V/Cohen’s d | p | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age | 49.69 | 12.42 | 49.38 | 12.04 | 49.96 | 13 | .05 | .88 |

| Sex (female) | 13 | 28.9 | 6 | 13.3 | 7 | 15.6 | .01 | .97 |

| Race | .26 | .22 | ||||||

| Black | 30 | 66.7 | 13 | 28.9 | 17 | 37.8 | ||

| White | 13 | 28.9 | 8 | 17.8 | 5 | 11.1 | ||

| Multiracial | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4.4 | ||

| Education | .27 | .19 | ||||||

| Less than high school | 10 | 22.2 | 5 | 11.1 | 5 | 11.1 | ||

| High school graduate/GED | 23 | 51.1 | 8 | 17.8 | 15 | 33.3 | ||

| More than high school | 12 | 26.7 | 8 | 17.8 | 4 | 8.9 | ||

| Marital Status | .41 | .06 | ||||||

| Never married | 18 | 40 | 4 | 8.9 | 14 | 31.1 | ||

| Married | 5 | 11.1 | 3 | 6.7 | 2 | 4.4 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 18 | 40 | 11 | 24.4 | 7 | 15.6 | ||

| Widow | 4 | 8.9 | 3 | 6.7 | 1 | 2.2 | ||

| Number of children | 1.62 | 1.89 | 1.62 | 1.94 | 1.63 | 1.88 | .08 | .99 |

| Smoking Characteristics | ||||||||

| Cigarettes per day | 14.91 | 8.66 | 15.95 | 8.77 | 14 | 8.65 | .22 | .46 |

| Carbon monoxide level | 19.6 | 8.77 | 19.9 | 8.49 | 19.33 | 9.19 | .06 | .83 |

| Number of years smoked | 29.53 | 11.1 | 27.24 | 9.77 | 31.54 | 12 | .39 | .2 |

| Thinking of quitting | .29 | .15 | ||||||

| Not thinking of quitting | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8.3 | ||

| Yes, within next 30 days | 29 | 64.4 | 12 | 57.1 | 17 | 70.8 | ||

| Yes, within next 6 months | 14 | 31.1 | 9 | 42.9 | 5 | 20.8 | ||

| Tried NRT to quit | 15 | 33.3 | 9 | 42.9 | 6 | 25 | .19 | .21 |

| Tried NicoBloc to quit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -- | -- |

| Tried self-help materials to quit | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | .16 | .28 |

| Tried therapy to quit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -- | -- |

| Tried hypnosis to quit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -- | -- |

| Tried medication to quit | 3 | 6.7 | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 4.2 | .10 | .47 |

| Tried e-cigarettes to quit | 4 | 8.9 | 2 | 9.5 | 2 | 8.3 | .02 | .89 |

| Exacerbated medical problems | 10 | 22.2 | 6 | 28.6 | 4 | 16.7 | .15 | .59 |

| Live with people who smoke | 26 | 57.8 | 11 | 52.4 | 15 | 62.5 | .1 | .49 |

| Type of cigarette smoked | .35 | .14 | ||||||

| Regular tar | 9 | 20 | 3 | 14.3 | 6 | 25 | ||

| Light tar | 3 | 6.7 | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 4.2 | ||

| Menthol regular | 29 | 64.4 | 16 | 76.2 | 13 | 54.2 | ||

| Menthol light | 4 | 8.9 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 16.7 | ||

| FTCD score | 5.69 | 2.05 | 5.86 | 2.13 | 5.54 | 2.02 | .15 | .61 |

| QSU score | 40.64 | 15.66 | 39.52 | 15.34 | 41.63 | 16.2 | .13 | .66 |

| MNWS score | 13.64 | 7.58 | 13.8 | 7.81 | 13.5 | 7.54 | .04 | .89 |

Intervention acceptability was assessed via participant expectancies (positive and negative) as well as overall treatment satisfaction. Regarding the SETS, generalized estimating equations (GEE) revealed no differences in positive expectancies between groups over time (group × time interaction: Wald Chi-Square (4) = 5.64, p = 0.23). Similarly, the groups did not differ over time regarding negative expectancies (group × time interaction: Wald Chi-Square (4) = 2.57, p = 0.63).

Regarding the Treatment Satisfaction Scale, the NicoBloc® group exhibited less satisfaction at Week 12 (M = 62.69, SD = 8.46; t[23] = 2.84, p = 0.01) than the nicotine lozenge group (M = 69.67, SD = 0.65; Cohen’s d = 1.14). There were no group differences in treatment satisfaction at Week 16 (p = 0.20). A summary of group differences over time can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Differences by Treatment Group in Feasibility, Acceptability, Product Side Effects, Smoking Behavior, Nicotine Dependence, and Adherence.

| Variable | NicoBloc® | Lozenge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | n total | M (SD) | n total | M (SD) | Cohen’s d | p | |

| Treatment Expectanciesa | |||||||

| Positive | BL | 21 | 5.32 (1.22) | 23 | 4.59 (1.16) | 0.61 | 0.05* |

| Week 4 | 16 | 4.96 (1.50) | 17 | 5.29 (2.06) | 0.18 | 0.52 | |

| Week 8 | 16 | 4.98 (1.54) | 15 | 5.78 (1.35) | 0.55 | 0.14 | |

| Week 12 | 14 | 4.69 (1.58) | 14 | 5.52 (1.78) | 0.49 | 0.20 | |

| M1FU | 13 | 4.49 (1.16) | 13 | 5.62 (1.68) | 0.78 | 0.06 | |

| Negative | BL | 21 | 2.38 (1.47) | 24 | 2.13 (1.5) | 0.17 | 0.58 |

| Week 4 | 16 | 2.46 (1.56) | 17 | 1.92 (1.19) | 1.12 | 0.27 | |

| Week 8 | 16 | 1.77 (1.18) | 15 | 1.84 (1.28) | 0.06 | 0.16 | |

| Week 12 | 14 | 1.86 (1.07) | 14 | 1.69 (1.1) | 0.41 | 0.68 | |

| M1FU | 13 | 2.28 (1.45) | 13 | 1.69 (1.38) | 1.06 | 0.30 | |

| Treatment Satisfactionb | Week 12 | 13 | 62.69 (8.46) | 12 | 69.67 (0.65) | 1.14 | 0.01** |

| M1FU | 13 | 63.62 (7.04) | 12 | 64.67 (17.25) | 0.08 | 0.20 | |

| Symptom Side Effectsc | Week 2 | 17 | 63.59 (23.99) | 18 | 69.61 (48.70) | 0.46 | 0.65 |

| Week 3 | 16 | 67.88 (34.50) | 17 | 68.47 (53.87) | 1.93 | 0.06 | |

| Week 4 | 16 | 57.62 (15.73) | 17 | 56.29 (21.78) | 0.07 | 0.84 | |

| Week 8 | 16 | 59.31 (27.06) | 15 | 57.20 (27.98) | 0.08 | 0.21 | |

| Week 12 | 14 | 60.86 (25.68) | 14 | 58.78 (28.07) | 0.20 | 0.84 | |

| Cigarettes Per Day | Week 1 | 17 | 12.1 (6.96) | 20 | 12.9 (6.86) | 0.12 | 0.73 |

| Week 2 | 15 | 9.8 (5.09) | 18 | 8.9 (4.55) | 0.19 | 0.60 | |

| Week 3 | 16 | 8.7 (5.45) | 17 | 7.1 (3.11) | 0.36 | 0.30 | |

| Week 4 | 16 | 8.0 (5.31) | 17 | 5.7 (4.02) | 0.49 | 0.17 | |

| Week 8 | 13 | 6.7 (5.31) | 14 | 4.6 (2.46) | 0.51 | 0.19 | |

| Week 12 | 12 | 5.9 (5.14) | 12 | 3.0 (1.69) | 0.76 | 0.08 | |

| M1FU | 13 | 7.0 (5.15) | 9 | 3.2 (2.04) | 0.91 | 0.05* | |

| Cigarette Dependence | BL | 21 | 5.86 (2.13) | 24 | 5.54 (2.02) | 0.15 | 0.61 |

| (FTCD)d | Week 8 | 16 | 3.69 (1.99) | 15 | 2.73 (1.71) | 0.52 | 0.16 |

| Week 12 | 14 | 3.79 (1.81) | 14 | 2.29 (1.94) | 0.80 | 0.04* | |

| M1FU | 13 | 3.61 (2.40) | 13 | 2.23 (1.92) | 0.63 | 0.12 | |

| Smoking Urges (QSU; | Week 1 | 18 | −10.17 (11.46) | 20 | −14.50 (19.00) | 0.27 | 0.41 |

| Post QSU-Pre QSU)e | Week 2 | 17 | −11.47 (12.41) | 18 | −7.50 (7.37) | 0.39 | 0.25 |

| Week 3 | 16 | −9.25 (14.07) | 17 | −4.71 (13.05) | 0.33 | 0.34 | |

| Week 4 | 16 | −1.75 (5.60) | 17 | −0.65 (5.06) | 0.21 | 0.56 | |

| Nicotine Withdrawal | Week 1 | 18 | −3.67 (5.02) | 20 | −6.20 (6.29) | 0.44 | 0.18 |

| (MWS; Post MWS-Pre | Week 2 | 17 | −3.18 (5.08) | 18 | −4.11 (4.34) | 0.20 | 0.56 |

| MWS)f | Week 3 | 16 | −5.06 (7.59) | 17 | −2.29 (3.77) | 0.47 | 0.19 |

| Week 4 | 16 | −0.63 (2.92) | 17 | −0.82 (3.09) | 0.06 | 0.86 | |

| Brief Wisconsin | BL | 21 | 49.31 (14.64) | 24 | 45.74 (16.03) | 0.23 | 0.44 |

| Inventory of Smoking | Week 8 | 16 | 34.26 (13.20) | 15 | 29.45 (13.20) | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| Dependence Motives | Week 12 | 14 | 39.38 (15.31) | 14 | 25.15 (10.80) | 1.07 | 0.01** |

| (WISDM) g | M1FU | 13 | 36.61 (15.14) | 13 | 21.65 (12.35) | 1.08 | 0.01* |

| Variable | Week | n at BL | n dropped (%) | n at BL | n dropped (%) | Cramer’s V | RR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly attrition | Week 1 | 21 | 3 (14.3%) | 24 | 3 (12.5%) | 0.03 | 1.14 | 0.86 |

| (Cumulative) | Week 2 | 21 | 4 (19.0%) | 24 | 6 (25.0%) | 0.07 | 0.76 | 0.63 |

| Week 3 | 21 | 5 (23.8%) | 24 | 7 (29.2%) | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.69 | |

| Week 4 | 21 | 5 (23.8%) | 24 | 7 (29.2%) | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.69 | |

| Week 8 | 21 | 5 (23.8%) | 24 | 9 (37.5%) | 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.32 | |

| Week 12 | 21 | 7 (33.3%) | 24 | 10 (41.7%) | 0.09 | 0.80 | 0.57 | |

| M1FU | 21 | 8 (38.1%) | 24 | 11 (45.8%) | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.60 | |

| Variable | Week | n Total | % | n Total | % | Cramer’s V | RR | p |

| Percent of Days 80% Product Adherent | Week 2 | 15 | 53.3% | 17 | 60.8% | 0.55 | 0.88 | 0.29 |

| Week 3 | 14 | 83.7% | 16 | 64.8% | 0.33 | 1.29 | 0.53 | |

| Week 4 | 16 | 82.5% | 12 | 70.5% | 0.36 | 1.17 | 0.44 | |

| Week 8 | 13 | 75.3% | 14 | 58.8% | 0.77 | 1.28 | 0.31 | |

| Week 12 | 12 | 93.5% | 12 | 50.1% | 0.77 | 1.87 | 0.16 | |

| Percent of Participants 80% Product Adherence for Study Duration | Week 2– Week 12 | 17 | 70.6% | 19 | 36.8% | 0.34 | 1.92 | 0.04* |

| Point-Prevalence Abstinent | Week 4 | 16 | 0% | 17 | 0% | - | - | - |

| Week 8 | 16 | 0% | 15 | 13.3% | 0.27 | 0 | 0.13 | |

| Week 12 | 13 | 0% | 14 | 21.4% | 0.34 | 0 | 0.08 | |

| M1FU | 13 | 0% | 13 | 15.4% | 0.29 | 0 | 0.14 |

Note: ns vary due to missing data. RR = Relative Risk (Lozenge is reference).

p values < 0.05,

p values < 0.01,

7-item Likert scale where 1 = “Strongly Disagree” and 7 = “Strongly Agree.”

10-item scale where higher scores indicate more satisfaction with the study treatment.

37-item survey with items rated on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = “Not at all” to 7 = “Very much.”

6-item measure with higher scores indicating more cigarette dependence.

10-item measure with items rated on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = “Strongly Disagree” and 7 = “Strongly Agree.”

8-item measure with items rated on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = “None” and 5 = “Severe.”

37-item survey with items rated on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = “Not true of me at all” and 7 = “Extremely true of me.”

3.4. Side Effects

GEE models revealed no differences in side effects between treatment groups over time (group × time interaction: Wald Chi-Square (4) = 1.18, p = 0.88). In the NicoBloc® group, change in taste, increase in appetite, and having nicotine cravings were the three most strongly endorsed side effects reported across time points. In the lozenge group, change in taste, change in smell, and increase in appetite were the most reported side effects.

3.5. Smoking Behavior and Cigarette Dependence

Regarding smoking behavior, GEEs revealed no differences between the treatment groups in number of cigarettes smoked per day throughout the intervention (group × time interaction: Wald Chi-Square (6) = 5.20, p = 0.51). Analyses revealed a significant effect of time (Wald Chi-Square (6) = 55.15, p < 0.001) indicating an overall decrease in daily cigarette smoking from Week 1 – Week 12 in both groups (ps< 0.05). There was no main effect of group (Wald Chi-Square (1) = 2.02, p = 0.15). Chi-Square analysis revealed no group differences in point prevalence abstinence at Week 8 (X2 [1, 1] = 2.30, p = 0.13), Week 12 (X2 [1, 1] = 3.10, p = 0.08), or at Week 16 (X2 [1, 1] = 2.20, p = 0.48). No participants in either group reported abstinence at Week 4. Group rates of CPD and point prevalence abstinence per time point are exhibited in Table 3. GEE results assessing Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) results revealed an effect of group (Wald Chi-Square (1) = 3.98, p = 0.05) and time (Wald Chi-Square (3) = 47.33, p < 0.001) whereby the nicotine lozenge group reported less overall dependence and dependence decreased over time in both groups. Post hoc comparisons revealed that, in both groups, FTCD scores reported at Weeks 8, 12, and 16 each significantly differed from scores at baseline (ps < 0.01), decreasing over time in each instance. There was no effect of group over time for the FTCD (Wald Chi-Square (3) = 2.35, p = 0.50).

GEEs assessing the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS) indicated a significant effect of time (Wald Chi-Square (3) = 17.07, p < 0.001). At Week 4, MNWS scores decreased significantly less from pre- to post-session than during Weeks 1–3 in both groups (ps< 0.01). There was no main effect of group (Wald Chi-Square (1) = 0.60, p = 0.81) or group by time interaction of MNWS change scores (group × time interaction: Wald Chi-Square (3) = 5.08, p = 0.17). Independent samples t-test analyses revealed no significant differences in MNWS scores between the NicoBloc® and lozenge groups at any time point. GEE analyses examining scores from the Brief Wisconsin Index of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) across time indicated a significant group by time interaction (group × time interaction: Wald Chi-Square (3) = 10.27, p = 0.02) in which the lozenge group reported significantly lower smoking dependence motives than the NicoBloc® group over time.

Analyses of pre- to post-session Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU) results followed a similar pattern revealing a main effect of time (Wald Chi-Square (3) = 33.46, p < 0.001). There was no main effect of group (Wald Chi-Square (1) = 0.30, p = 0.60) or group by time interaction of QSU change scores (group × time interaction: Wald Chi-Square (3) = 2.77, p = 0.43). However, independent samples t-test analyses revealed marginally significant differences in QSU scores between the NicoBloc® (M = 24.00, SD = 15.34) and lozenge (M = 13.16, SD = 9.21) groups only at Week 16, t(19.66) = 2.092, p = 0.05.

3.6. Adherence

In examining daily self-reported adherence overall, the NicoBloc® group met 80% product adherence on significantly more days throughout the study than the nicotine lozenge group (19% mean difference; t[33] = 1.79, p = 0.02). Additionally, a greater percentage of participants in the NicoBloc® group met our overall adherence criteria (product adherent 80% of days for the study duration; 33.8% mean difference; X2 [1, 36] = 4.10, p = 0.04). These analyses examined overall adherence throughout the duration of the study rather than examining individual time points (See Table 3).

4. Discussion

This pilot study assessed the feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of NicoBloc®, a novel smoking cessation product, as compared to standard NRT (nicotine lozenge) in a community sample. To our knowledge, this is the first study to incorporate NicoBloc® into a smoking cessation intervention for comparison to established pharmacological treatments and only the second to examine outcomes relevant to cessation efficacy. 12

NicoBloc® treatment was feasible to deliver as retention rates at Week 16 did not significantly differ between intervention groups. However, retention rates were lower than initially hypothesized and below rates reported in comparable prior studies. 19,20 While this is not an uncommon issue among small pilot randomized trials, 12,21 the start of the global COVID-19 pandemic was likely the primary factor contributing to elevated attrition. Overall, participant recruitment and retention for numerous studies and clinical trials have been severely impacted by COVID-19 due to the limited ability to engage participants lost to follow-up because of social distancing precautions and lack of on-site research staff. 22,23

Ratings of positive and negative treatment expectancies and symptom side effects were also comparable. The NicoBloc® group endorsed lower treatment satisfaction at Week 12 but was equivalent to the nicotine lozenge group at Week 16. In examining smoking behavior, reductions in CPD and abstinence at Week 16 were equivalent across groups, but the nicotine lozenge group reported lower cigarette dependence. After using their products in-session, both groups reported similar patterns of reduction in withdrawal symptoms and smoking urges.

Given the forced titration that use of NicoBloc® induces, it may be particularly beneficial to examine the use of NicoBloc® combined with other NRT products. 24–26 This would allow participants to continue smoking their preferred brand while gradually reducing nicotine and allowing it to be replaced with NRT to diminish withdrawal and craving symptoms. As our results indicate, despite overall feasibility and acceptability, participants in the NicoBloc® group reported lower treatment satisfaction at the conclusion of the intervention (Week 12) which is likely due to experiencing increased withdrawal symptoms relative to smokers in the NRT lozenge condition. Although there were no group differences in reported withdrawal symptoms using the MNWS from Weeks 1–4, it may be that participants in the NicoBloc® group experienced greater withdrawal symptoms after beginning to use three drops of the product or making quit attempts in later weeks. Partial support for this is seen in the change in the reduction of dependence motives among lozenge but not NicoBloc® groups. The WISDM contains subscales of dependence motives that maintain smoking behavior such as craving, tolerance, positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, and craving as well as other nonphysiological dependence motives such as affiliative attachment, cognitive enhancement and weight control. 27 Not surprisingly, lozenges decreased these physiological symptoms while NicoBloc participants did not get the same physiological relief. Thus, the two methods potentially worked through different mechanisms with lozenges reducing withdrawal and dependence characteristics and NicoBloc targeting more of the behavioral and psychological aspects of dependence. As such, future studies should evaluate whether a combination of NRT and NicoBloc® could potentially increase participant expectancies of product effectiveness while retaining the unique benefits of each and minimizing withdrawal symptoms.

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

While the results of the present study provide compelling and novel contributions to the field, several limitations should be considered when interpreting findings. For one, the scope of the present study was narrow, utilizing a small community sample and focusing primarily on acceptability and feasibility. More than 50% of eligible participants did not attend the baseline session after being screened. While this rate is equivalent to other smoking cessation studies, 28,29 we did not follow-up with participants to determine the factors accounting for dropout between screening and enrollment. In addition, like numerous other studies and clinical trials, 22,23 participant recruitment and retention were severely and negatively impacted by the global COVID-19 pandemic. The unexpected low retention was likely attributable to a myriad of COVID-related factors (e.g., reduced childcare, work from home policies, lack of public transportation, etc.). Although other pre-COVID smoking cessation pilot studies report similar sample size, 21,30,31 future studies are encouraged to examine these constructs using larger samples to increase the power and generalizability of results. Furthermore, this study utilized self-report data to estimate both adherence and smoking rates. Although participants were asked to record their product use and smoking behavior in a calendar daily throughout the intervention, future studies may benefit from utilizing more immediate data capture methodologies, such as ecological momentary assessments. Additionally, the current study did not measure toxicant exposure from NicoBloc®. Future studies may shed light on the tobacco-related carcinogens and additives consumed with varying levels of NicoBloc® use by including this measure.

5. Conclusions

The current study is the first to date to incorporate NicoBloc® in a smoking cessation intervention and compare it to an established smoking cessation product. The results indicate that NicoBloc® is similarly feasible to deliver in an intervention with potentially improved adherence in comparison to an acute nicotine delivery product (lozenges). NicoBloc’s® unique composition and usage set it apart from established cessation aids and may be preferable to smokers seeking a non-pharmacological intervention or as a harm reduction strategy.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by NicoBloc® USA (Bloc Enterprises, LLC, 11 Grumman Hill Road, CT 06897), the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23 DA045766).

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

References

- 1.CDC. Tobacco Use. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/tobacco.htm

- 2.Mills EJ, Wu P, Lockhart I, Wilson K, Ebbert JO. Adverse events associated with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for smoking cessation. A systematic review and meta-analysis of one hundred and twenty studies involving 177,390 individuals. Tob Induc Dis. Jul 13 2010;8(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. May 31 2018;5(5):Cd000146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rankin KV, Jones DL. Chapter 17 - Prevention Strategies for Oral Cancer. In: Cappelli DP, Mobley CC, eds. Prevention in Clinical Oral Health Care. Mosby; 2008:230–243. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogt F, Hall S, Marteau TM. Understanding why smokers do not want to use nicotine dependence medications to stop smoking: qualitative and quantitative studies. Nicotine Tob Res. Aug 2008;10(8):1405–13. doi: 10.1080/14622200802239280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donny EC, Jones M. Prolonged exposure to denicotinized cigarettes with or without transdermal nicotine. Drug Alcohol Depend. Sep 1 2009;104(1–2):23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker KM, Rose JE, Albino AP. A randomized trial of nicotine replacement therapy in combination with reduced-nicotine cigarettes for smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(7):1139–1148. doi: 10.1080/14622200802123294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benowitz NL, Hall SM, Stewart S, Wilson M, Dempsey D, Jacob P 3rd. Nicotine and carcinogen exposure with smoking of progressively reduced nicotine content cigarette. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. Nov 2007;16(11):2479–85. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-07-0393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dermody SS, Donny EC, Hertsgaard LA, Hatsukami DK. Greater reductions in nicotine exposure while smoking very low nicotine content cigarettes predict smoking cessation. Tob Control. Nov 2015;24(6):536–9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatsukami DK, Kotlyar M, Hertsgaard LA, et al. Reduced nicotine content cigarettes: effects on toxicant exposure, dependence and cessation. Addiction (Abingdon, England). Feb 2010;105(2):343–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02780.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shahan TA, Bickel WK, Badger GJ, Giordano LA. Sensitivity of nicotine-containing and de-nicotinized cigarette consumption to alternative non-drug reinforcement: A behavioral economic analysis. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2001;12(4):277–284. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200107000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gariti P, Alterman AI, Lynch KG, Kampman K, Whittingham T. Adding a nicotine blocking agent to cigarette tapering. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NicoBloc USA. FAQS - NicoBloc USA. https://www.nicoblocusa.com/faqs/

- 14.Arista Laboratories. Interpretation of Nicotine and Tar Blocking Tests Carried out by Arista Labs, July 2009. Vol. Report No. 29076. 2009.

- 15.Essentra. Note Regarding NicoBloc Testing Carried Out by Essentra October 2013. 2013.

- 16.Pickworth WB, Fant RV, Nelson RA, Henningfield JE. Effects of cigarette smoking through a partially occluded filter. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1998;60(4):817–821. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(98)00042-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross J, Lee J, Stitzer ML. Nicotine-containing versus de-nicotinized cigarettes: effects on craving and withdrawal. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. May-Jun 1997;57(1–2):159–65. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00309-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lappan SN, Brown AW, Hendricks PS. Dropout rates of in-person psychosocial substance use disorder treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England). Feb 2020;115(2):201–217. doi: 10.1111/add.14793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cropsey KL, Hendricks PS, Schiavon S, et al. A pilot trial of in vivo NRT sampling to increase medication adherence in community corrections smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;67:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiffman S, Sweeney CT, Ferguson SG, Sembower MA, Gitchell JG. Relationship between adherence to daily nicotine patch use and treatment efficacy: secondary analysis of a 10-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial simulating over-the-counter use in adult smokers. Clinical therapeutics. Oct 2008;30(10):1852–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahler CW, Spillane NS, Day AM, et al. Positive psychotherapy for smoking cessation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17(11):1385–1392. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell EJ, Ahmed K, Breeman S, et al. It is unprecedented: trial management during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Trials. 2020/September/11 2020;21(1):784. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04711-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sathian B, Asim M, Banerjee I, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on clinical trials and clinical research: A systematic review. Nepal J Epidemiol. Sep 2020;10(3):878–887. doi: 10.3126/nje.v10i3.31622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebbert JO, Croghan IT, Sood A, Schroeder DR, Hays JT, Hurt RD. Varenicline and bupropion sustained-release combination therapy for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. Mar 2009;11(3):234–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Mar 24 2016;3:Cd008286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sweeney CT, Fant RV, Fagerstrom KO, McGovern JF, Henningfield JE. Combination nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: rationale, efficacy and tolerability. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(6):453–67. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piper ME, Piasecki TM, Federman EB, et al. A Multiple Motives Approach to Tobacco Dependence: The Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):139–154. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vilardaga R, Rizo J, Palenski PE, Mannelli P, Oliver JA, McClernon FJ. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a Novel Smoking Cessation App Designed for Individuals With Co-Occurring Tobacco Use Disorder and Serious Mental Illness. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2020;22(9):1533–1542. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vidrine DJ, Frank-Pearce SG, Vidrine JI, et al. Efficacy of Mobile Phone–Delivered Smoking Cessation Interventions for Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Individuals: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019;179(2):167–174. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dedert EA, Resick PA, Dennis PA, Wilson SM, Moore SD, Beckham JC. Pilot Trial of a Combined Cognitive Processing Therapy and Smoking Cessation Treatment. J Addict Med. Jul/Aug 2019;13(4):322–330. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunzel B, Cabalza J, Faurot M, et al. Prospective Pilot Study of Smoking Cessation in Patients Undergoing Urologic Surgery. Urology. 2012/July/01/ 2012;80(1):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Younger J, Gandhi V, Hubbard E, Mackey S. Development of the Stanford Expectations of Treatment Scale (SETS): a tool for measuring patient outcome expectancy in clinical trials. Clin Trials. Dec 2012;9(6):767–76. doi: 10.1177/1740774512465064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Payne TJ, Crews KM. Brief Treatment of the Tobacco Dependent Patient: A Training Program for Healthcare Providers. University of Mississippi Medical Center Printing Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fagerström K Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. Jan 2012;14(1):75–8. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. Br J Addict. Nov 1991;86(11):1467–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Mar 1986;43(3):289–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Humana Press; 1992:41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Jao NC. Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. May 2013;15(5):978–82. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benowitz NL, Bernert JT, Foulds J, et al. Biochemical Verification of Tobacco Use and Abstinence: 2019 Update. Nicotine Tob Res. Jun 12 2020;22(7):1086–1097. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shelley D, Tseng TY, Gonzalez M, et al. Correlates of Adherence to Varenicline Among HIV+ Smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. Aug 2015;17(8):968–74. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]