Abstract

In the absence of head-to-head comparison trials, we aimed to compare the effectiveness of two largely prescribed oral platform disease-modifying treatments for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis, namely, dimethyl fumarate (DMF) and teriflunomide (TRF). We searched scientific databases to identify real-world studies reporting a direct comparison of DMF versus TRF. We fitted inverse-variance weighted meta-analyses with random effects models to estimate the risk ratio (RR) of relapse, confirmed disability worsening (CDW), and treatment discontinuation. Quantitative synthesis was accomplished on 14 articles yielding 11,889 and 8133 patients treated with DMF and TRF, respectively, with a follow-up ranging from 1 to 2.8 years. DMF was slightly more effective than TRF in reducing the short-term relapse risk (RR = 0.92, p = 0.01). Meta-regression analyses showed that such between-arm difference tends to fade in studies including younger patients and a higher proportion of treatment-naïve subjects. There was no difference between DMF and TRF on the short-term risk of CDW (RR = 0.99, p = 0.69). The risk of treatment discontinuation was similar across the two oral drugs (RR = 1.02, p = 0.63), but it became slightly higher with DMF than with TRF (RR = 1.07, p = 0.007) after removing one study with a potential publication bias that altered the final pooled result, as also confirmed by a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. Discontinuation due to side effects and adverse events was reported more frequently with DMF than with TRF. Our findings suggest that DMF is associated with a lower risk of relapses than TRF, with more nuanced differences in younger naïve patients. On the other hand, TRF is associated with a lower risk of treatment discontinuation for side effects and adverse events.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13311-023-01416-x.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Disease-modifying treatments, Dimethyl fumarate, Teriflunomide, Head-to-head study

Introduction

The therapeutic landscape for multiple sclerosis (MS) is rapidly evolving. The abundance of new treatment options and the re-definition of treatment goals will pose both opportunities and challenges. Treatment of patients with MS is complex due to consideration of disease activity, phenotype, patient characteristics, and prior biologic exposure [1]. Treatment choice should be tailored to the individual, but personalized therapy in MS remains a distant goal. Specifically, how will we choose the most appropriate therapy for an individual patient?

Available disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) have a major impact on the disease course in relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS), by halting neuroinflammation in the short and medium term as well as delaying the long-term accumulation of irreversible disability. For an individual patient, it is necessary to choose the right DMT to control disease activity and improve long-term prognosis but, at the same time, to ensure an acceptable safety profile [1]. However, currently available experimental data are insufficient to inform an evidence-based choice given the paucity of head-to-head randomized clinical trials (RCTs) [2].

Self-injectable DMTs were compared in three RCTs providing evidence that glatiramer acetate (GA) is not inferior to interferon beta (IFNB) in preventing relapses and in reducing disease activity on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [3–5]. Early initiation of higher-efficacy monoclonal antibodies (namely alemtuzumab, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, rituximab) is supported by head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating their superior efficacy over IFNB [6–10], dimethyl fumarate (DMF) [11], or teriflunomide (TRF) [12].

DMF and TRF are two largely prescribed oral DMTs approved as platform therapies for RRMS. Both DMTs have demonstrated their efficacy in slowing down clinical and MRI disease activity and disability accumulation, as compared to placebo. To date, nevertheless, no head-to-head RCT comparing their efficacy and safety is available, whereas there are a number of observational studies adopting different methodologies and often yielding mixed results.

Here, we sought to unravel these conflicting research outcomes by meta-analyzing real-world observational studies to reach an overall understanding of clinical outcomes. We decided to exclude fingolimod, another oral DMT, recommended as a “second-line” treatment strategy in Europe, thus potentially weighing on heterogeneity.

Methods

Study Design and Registration

Our meta-analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [13], and the review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (Registration Number: CRD42020223358).

Search Strategy

Relevant studies were systematically searched in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar, using combinations of free text and MeSH terms for articles published until December 31, 2022, as follows: “multiple sclerosis” AND “dimethyl fumarate” AND “teriflunomide” NOT “clinical trial” NOT “review.”

To avoid the risk of missing relevant articles, we searched for additional papers through the bibliography of previously published reviews; we also performed a generic web search. One reviewing author (LP) ran the search strategy and screened the initial titles after removing duplicates. Two authors (CT and CG) independently examined each potentially relevant article, using the following criteria as defined by the PI(E)COS model [14]:

Population (P): adult persons (aged ≥ 18 years) with RRMS.

Intervention (I): oral DMF 240 mg bis in die (bid).

Exposure (E): not applicable.

Comparison (C): oral TRF 14 mg once daily.

Outcomes (O): risk of relapse, confirmed disability worsening (CDW), and treatment discontinuation (for any reason).

Setting (S): real-world setting.

Data Extraction

Two authors (LP and SR) independently performed data extraction, with disagreement resolved by a third author (SH). We focused only on a direct comparison between DMF and TRF even when a study had multiple comparisons between different DMTs. When reported data were insufficient for the analysis, we contacted the study author to request access to additional data (see acknowledgments).

The following information were extracted from each article: first author name, journal, publication year, sample size of the two groups, study follow-up, and population characteristics at treatment start, i.e., sex, age, disease duration, score on Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), pre-treatment (prior year) annualized relapse rate (ARR), and proportion of naïve patients. Regarding outcomes (risk of relapse, CDW, and treatment discontinuation), we considered adjusted estimates that were less likely to be biased by confounding factors [15]. If not available, estimates were computed using the proportions of patients reaching the outcomes and follow-up.

An Excel spreadsheet containing all data of included studies is available as a supplemental file (Appendix.xlxs).

Statistics

Quality assessment of individual studies and across studies was performed by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [16].

Included studies presented different types of effect estimates (hazard ratio and odds ratio); therefore, we converted them into a common metric (rate ratios, abbreviated as RR henceforth) [17]. For consistency, we reported comparisons of DMF versus TRF (reference) throughout the article, so that RR < 1.0 indicated a better outcome for DMF.

We estimated the pooled effect size (ES) on log-transformed RR of DMF versus TRF by random effects models weighted using a restricted maximum likelihood approach. If necessary, subgroup analysis and meta-regression were conducted to explore the possible sources of heterogeneity, by entering a between-arm difference in baseline characteristics as moderators. For case–control matched studies, we entered only post-matching variables into meta-analysis and meta-regression models. The normality assumption was checked for all variables entered in models and for their residuals; if the normality assumption was not met, the variable was log-transformed.

Between-study variance and heterogeneity were assessed by Cochran’s Q-value and I2 index, respectively; we considered an I2 ≤ 25% as marginal, 25 to 75% as moderate, and ≥ 75% as substantial heterogeneity. Risk of publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger’s test of asymmetry. Two-tailed p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Data were analyzed by using the freeware software JASP version 0.17.1.0 (JASP Team, 2023; www.jasp-stats.org).

Results

Search Findings

Our search retrieved 126 articles. After screening the title and abstract, we identified 69 articles for eligibility. Of these, 14 articles [18–31] published from 2017 to 2021 met the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Studies were conducted in the following countries: France (3 articles) [20, 26, 30], USA (3 articles) [18, 28, 31], Italy (2 articles) [21, 29], Austria [23], Denmark [22], Germany [19], Iran [27], Sweden [24], and international registry [25].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart [13] for study selection

To deal with the lack of randomization, adjusted estimates were based on propensity score matching in six studies [19, 24, 25, 27–29], multivariable regression in four studies [18, 20, 21, 30], inverse probability treatment weighting in three studies [22, 23, 26], and no correction in one studies without a relevant between-arm difference at baseline [31]. Six studies were funded by the manufacturer of DMF [18, 19, 28] and TRF [24, 30, 31].

According to the NOS, all but two studies [30, 31] had good methodological quality (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [16] of included studies (one "⋆" means 1 point)

| First author | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total quality score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Boster et al. [18] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7* | ||

| Braune et al. [19] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 9* |

| Condé et al. [20] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | ||

| D’Amico et al. [21] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 8 | |

| Buron et al. [22] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 9 |

| Guger et al. [23] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 9 |

| Hillert et al. [24] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 9* |

| Kalincik et al. [25] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 9 |

| Laplaud et al. [26] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 9 |

| Nehzat et al. [27] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 8 | |

| Ontaneda et al. [28] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7* | ||

| Prosperini et al. [29] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 7 | ||

| Vermersch [30] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5* | ||||

| Zivadinov et al. [31] | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | ⋆ | 5* | |||||

Selection: 1—representativeness of exposed cohort, 2—selection of non-exposed cohort, 3—ascertainment of exposure, 4—demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study. Comparability: 1—adjust for the most important risk factors, 2—adjust for other risk factors. Outcome: 1—assessment of outcome, 2—follow-up length, 3—loss to follow-up rate

*This study was partly or totally funded by the manufacturer of dimethyl fumarate [18, 19, 28] or teriflunomide [24, 30, 31]

Participants

We pooled data from 11,889 and 8133 patients treated with DMF and TRF, respectively. Their follow-up ranged from 1 to 2.8 years according to different studies, yielding 16,536 and 11,635 patient-years on DMF and TRF, respectively. Propensity score–based matching procedure reduced the sample size of six studies [19, 24, 25, 27–29].

Table 2 shows the main features of included studies, including the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants at treatment start.

Table 2.

Summary of the main baseline characteristics of included studies (k = 14)

| Arm | Sample size * | Male sex (%) | Mean age (years) | Mean disease duration (years) | Mean or median EDSS score | Pre-treatment relapse rate | Proportion of naïve patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boster et al. [18] | DMF | 3352 | 23.4 | 46.7 | N/R | N/R | 0.38 | 34.0 |

| TRF | 500 | 20.0 | 49.6 | N/R | N/R | 0.36 | 31.3 | |

| Braune et al. [19] | DMF | 388 | 32.2 | 44.2 | 10.2 | 2.0 | 0.34 | 36.1 |

| TRF | 388 | 33.2 | 44.1 | 10.0 | 2.0 | 0.46 | 38.4 | |

| Condé et al. [20] | DMF | 189 | 22.7 | 43.2 | 9.3 | 1.7 | 0.76 | 31.9 |

| TRF | 157 | 17.8 | 45.2 | 10.8 | 1.9 | 0.46 | 31.2 | |

| D’Amico et al. [21] | DMF | 1039 | 28.5 | 38.8 | 10.4 | 1.5 | 0.60 | 36.5 |

| TRF | 406 | 40.1 | 43.5 | 8.8 | 2.0 | 0.50 | 32.7 | |

| Buron et al. [22] | DMF | 767 | 24.2 | 39.0 | 7.1 | 1.9 | 0.80 | 36.3 |

| TRF | 1469 | 36.0 | 41.7 | 6.4 | 2.0 | 1.00 | 66.3 | |

| Guger et al. [23] | DMF | 227 | 31.7 | 38.1 | 8.0 | 1.7 | 1.00 | 44.1 |

| TRF | 107 | 40.2 | 42.8 | 8.8 | 2.1 | 0.70 | 37.4 | |

| Hillert et al. [24] | DMF | 353 | 31.2 | 47.6 | 11.4 | 1.5 | 0.27 | 22.4 |

| TRF | 353 | 29.5 | 46.7 | 10.9 | 2.0 | 0.25 | 23.5 | |

| Kalincik et al. [25] | DMF | 470 | 25.0 | 41.0 | 9.2 | 2.0 | 0.60 | 10.0 |

| TRF | 355 | 25.0 | 42.0 | 9.7 | 2.0 | 0.40 | 10.0 | |

| Laplaud et al. [26] | DMF | 659 | 26.8 | 38.0 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 0.80 | 42.4 |

| TRF | 409 | 28.3 | 41.3 | 8.4 | 1.7 | 0.60 | 44.6 | |

| Nehzat et al. [27] | DMF | 38 | 15.8 | 33.1 | 5.0 | 1.3 | 0.65 | 36.8 |

| TRF | 38 | 13.2 | 34.9 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 0.63 | 36.8 | |

| Ontaneda et al. [28] | DMF | 833 | 23.9 | 49.9 | N/R | N/R | 0.23 | 0.0 |

| TRF | 279 | 25.1 | 49.9 | N/R | N/R | 0.30 | 0.0 | |

| Prosperini et al. [29] | DMF | 74 | 23.0 | 46.5 | 12.4 | 2.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| TRF | 74 | 23.0 | 47.3 | 13.7 | 2.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | |

| Vermersch 2020 [30] | DMF | 3450 | 26.8 | 40.1 | 0.7 | N/R | N/R | 100.0 |

| TRF | 3548 | 30.3 | 43.6 | 0.7 | N/R | N/R | 100.0 | |

| Zivadinov et al. [31] | DMF | 50 | 28.0 | 48.4 | 13.1 | 3.0 | 0.08 | 16.0 |

| TRF | 50 | 22.0 | 49.5 | 13.8 | 3.0 | 0.27 | 10.0 |

Risk of Relapse

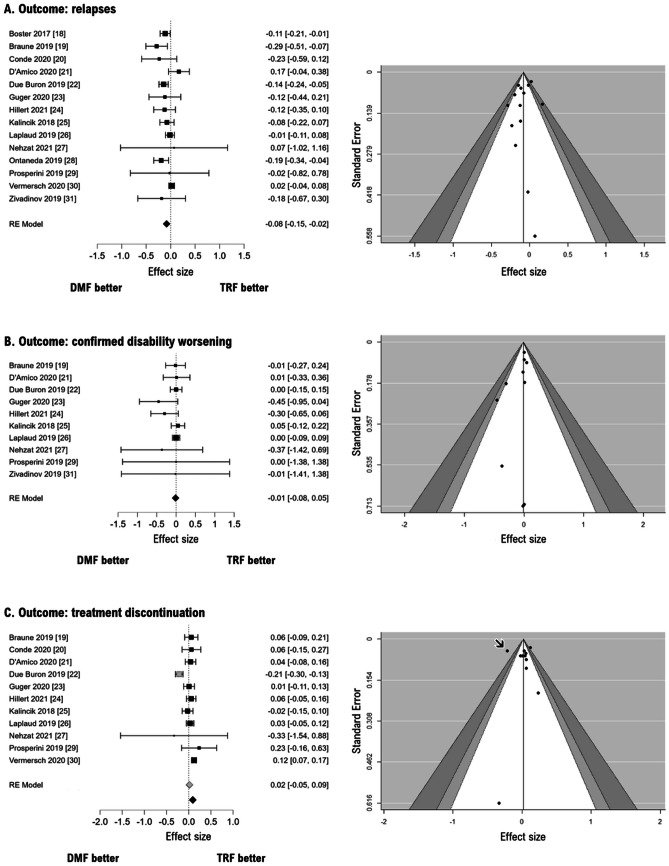

The pooled ES on all included studies [18–31] indicates a lower relapse risk for DMF versus TRF (RR = 0.92; logRR = − 0.08, 95% CIs from − 0.15 to − 0.02, p = 0.01; Fig. 2A), with substantial heterogeneity (Q13 = 25.7, p = 0.02; I2 = 52%). The visual inspection of the funnel plot and the Egger test indicates no risk of publication bias (Z = − 0.68, p = 0.50).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots (left) and funnel plots (right) for the risk of relapse (A), confirmed disability worsening (B), and treatment discontinuation (C). Effect size refers to log-transformed risk ratios (estimates < 1.0 indicate better outcome for DMF versus TRF). Gray diamond in C refers to the pooled effect size by including also one study [22] that, in the funnel plot, is located in the area of statistically significant publication bias (black arrow) and that alters the final results, as indicated by a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. Please note that some studies were partly or totally funded by the manufacturer of dimethyl fumarate [18, 19, 28] or teriflunomide [24, 30, 31]

A leave-one-out analysis confirmed that this estimate did not change substantially even after iteratively removing one study at a time.

A subgroup analysis comparing studies based on propensity score matching (leading to the selection of patients whose baseline characteristics are better balanced) versus the remaining studies did not reveal any substantial difference, confirming a lower risk of relapse with DMF than TRF (data not shown). However, limiting the analysis only to eight studies without conflict of interest (i.e., studies not funded by drug manufacturer) [20–23, 25–27, 29], we observed no difference between DMF and TRF in terms of relapse risk (RR = 0.95; logRR = − 0.06, 95% CIs from − 0.14 to 0.03, p = 0.19).

Adding either age at treatment start (for each decade: β = − 0.14, 95% CIs from − 0.27 to − 0.01, p = 0.035) or a greater proportion of naïve patients (for each point: β = 0.16, 95% CIs from 0.04 to 0.27, p = 0.008) led to a significant reduction of heterogeneity (I2 = 30% and 7%, respectively). These findings suggest that the observed difference in relapse risk for DMF versus TRF is largely attributable to the study including older patients switching from another DMT, whereas studies including younger naïve patients mitigated such between-arm difference.

Risk of Confirmed Disability Worsening

The pooled ES on ten studies reporting data on CDW outcome [19, 21–27, 29, 31] indicates no difference between DMF versus TRF (RR = 0.99; logRR = − 0.013, 95% CIs from − 0.008 to 0.053, p = 0.69; Fig. 2B), without heterogeneity (Q9 = 6.5, p = 0.68; I2 = 0%). The visual inspection of the funnel plot and the Egger test indicates no risk of publication bias (Z = − 1.33, p = 0.18). A leave-one-out analysis confirmed that this estimate did not change substantially even after iteratively removing one study at a time.

Risk of Treatment Discontinuation

The pooled ES on eleven studies reporting data on treatment discontinuation [19, 21–27, 29, 31] indicates no difference between DMF versus TRF (RR = 1.02; logRR = 0.02, 95% CIs from − 0.05 to 0.09, p = 0.63; Fig. 2C), with a substantial heterogeneity (Q1,10 = 0.3, p < 0.001; I2 = 74%). Although the Egger test indicates no risk of publication bias (Z = − 1.12, p = 0.26), the visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed one study falling in the area of statistical significance [22], thus suggesting a potential publication bias. A leave-one-out analysis confirmed indeed that the pooled ES was mainly driven by this study [22] with a large sample size (n = 2236), between-arm imbalance (767 and 1496 patients under DMF and TRF, respectively), and substantial difference in cause-specific discontinuation incidence. In more detail, discontinuation rates due to breakthrough disease were 10.7% for DMF and 22.4% for TRF, whereas discontinuation rates due to adverse events were 18.0% and 18.5% for DMF and TRF, respectively [22].

Therefore, we ran again the meta-analysis after removing such study [22]: the pooled ES indicated a higher risk of discontinuation with DMF versus TRF (RR = 1.07; logRR = 0.06, 95% CIs from 0.02 to 0.10, p = 0.007; Fig. 2C) with minimal heterogeneity (Q1,10 = 9.9, p = 0.36; I2 = 22%). This heterogeneity was not explained by any between-group difference in baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants.

A subgroup analysis comparing studies based on propensity score matching (leading to the selection of patients whose baseline characteristics are better balanced) versus the remaining studies did not reveal any substantial difference (data not shown). When limiting the analysis only to eight studies without conflict of interest (i.e., studies not funded by drug manufacturer) [20–23, 25–27, 29], we observed no difference between DMF and TRF on the risk of treatment discontinuation (RR = 1.02; logRR = 0.02, 95% CIs from − 0.03 to 0.07, p = 0.37).

Six articles provide details on reasons for interrupting oral DMTs [19, 21, 22, 24–26]: discontinuation for side effects and adverse events was more frequent in DMF-treated versus TRF-treated patients, whereas discontinuation due to disease activity was less frequent in DMF-treated versus TRF-treated patients.

Discussion

Real-World Evidence to Support the Decision-Making Process

The choice of initial DMT represents a crucial step for approaching to a personalized treatment algorithm, although we are still far from precision medicine in the MS field [1]. The development of accurate, patient-centered, and evidence-based algorithms would require RCT data for direct comparison between different therapeutic strategies.

In our opinion, pharmaceutical companies have shown little interest in conducting studies aimed at comparing DMTs in the same therapeutic line or different therapeutic strategies, other than head-to-head RCTs in which a low-efficacy comparator, often IFNB or TRF, is adopted (essentially, all the modern RCTs compared a high-efficacy versus a low-efficacy DMT). Indirect comparisons of data from RCTs may only partially help to inform clinical decision-making in the interim, albeit with methodological limitations (i.e., different study design, targeted population, baseline patients’ characteristics, and behavior of placebo groups) [32]. Given the lack of experimental data, we have come to rely more and more on real-world studies, which –although only hypothesis-generating and less robust– nevertheless can provide relevant insights into the complex therapeutic management of MS [2]. In this article, we directly compared the effectiveness of two platform oral DMTs, namely, DMF and TRF, that have never been directly compared in an experimental setting.

Which Oral Treatment in Early MS?

Oral DMF and TRF are two widely prescribed DMTs in both naïve patients and in those switching from another DMT (especially self-injectable ones) for treatment failure or side effects. We are aware of 14 real-world studies comparing the effectiveness of DMF versus TRF in the short term, with conflicting results [18–31]. We have therefore fitted meta-analyses of these data, by adopting an established methodological approach to deal with the heterogeneity in effect estimates across included studies [16, 17]. Apart from methodological heterogeneity, clinical heterogeneity is also expected to be much higher than in meta-analyses of RCTs, as observational studies are based on less stringent inclusion criteria [15].

Our meta-analyses suggest that (i) DMF is slightly more effective than TRF in reducing the short-term relapse risk, (ii) there is no difference between DMF and TRF on the short-term risk of CDW, and (iii) the risk of treatment discontinuation is substantially similar for both oral DMTs, although additional analyses indicated a higher risk of treatment discontinuation with DMF than with TRF after removing one study representing a source of heterogeneity and publication bias [22].

As regards the relapse risk, however, the age factor should be taken into consideration. According to our results, the superiority of DMF on relapse risk would be hypothetically altered by studies including younger naïve patients. Notably, we observed a between-arm imbalance in age at treatment start, such that DMF-treated patients were younger than TRF-treated patients, with a median difference of 2 years that raises to 3 years after excluding studies based on propensity score matching [19, 24, 25, 27–29]. This latter finding can be explained, at least partially, by the inclination to prescribe TRF to older patients switching from another DMT [33]. Moreover, younger age is generally associated with a higher proportion of naïve patients who, in turn, have a better chance of treatment response, especially if treated with platform DMTs [34].

Limiting the analyses only to studies not funded by pharmaceutical companies [20–23, 25–27, 29] yielded no between-arm difference. Although this latter finding could possibly be explained by the reduced sample size, we should also take into account the possibility of an underlying sponsorship bias, since the relapse risk was significantly lower with DMF than with TRF in all three studies funded by Biogen [18, 19, 28]. Likewise, the only study showing the obvious inferiority of DMF versus TRF on treatment persistence was funded by Sanofi [30].

The lower risk of discontinuation with TRF, especially when considering treatment withdrawal due to adverse events, confirms literature data supporting its good tolerability profile [29, 33]. On the other hand, DMF discontinuation is mainly due to gastrointestinal side effects, which are underestimated in RCTs than reported in the daily clinical setting [35]. Diroximel fumarate, a recently developed second-generation oral fumaric acid ester, showed improved gastrointestinal tolerability owing to a lower synthesis of gut-irritating methanol, limiting the risk of early treatment discontinuation [36].

Limitations

We are aware that our meta-analyses are not exempted from limitations, mainly due to the synthesis of observation studies at high risk for within-study and across-study biases and clinical and statistic heterogeneity [15]. Multicentre, randomized, controlled RCTs are undoubtedly the gold standard to obtain evidence-based data to assess the relative efficacy and safety profile of MS treatments, whereas observational data are prone to bias that can be overcome only partially [2]. Nevertheless, the synthesis of observational data has the advantage of generalizability, as more directly applicable to the clinical setting than data from RCTs, which usually involve very restricted populations treated under highly standardized care. Moreover, there is little evidence, on average, for significant differences in effect estimates between observational studies and RCTs [37].

Another potential source of bias and heterogeneity comes from pooling mixed types of effect estimates calculated with different adjustment methods used in every single study; we thereby converted them into the same metrics to improve data interpretation [17].

Lastly, when interpreting our meta-regressions, we should take into account the ecological fallacy of such an approach, considering that the association found in pooled data does not necessarily reflect the association found in individual patient data [38].

Conclusion

The absence of head-to-head RCTs and the difficulty in implementing pragmatic studies make the synthesis of observational data an important source of evidence to compare the effectiveness of DMF versus TRF. We found only minimal differences between these two oral DMTs, with DMF slightly superior to TRF on relapse reduction and TRF slightly superior to DMF on treatment persistence, owing to a better tolerability profile. Future efforts are warranted to collect long-term data on these two widely prescribed oral DMTs.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xavier Moisset and Daniel Ontaneda for data sharing.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available as an Excel spreadsheet (Appendix.xlsx).

Declarations

Ethical Statement

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

LP: consulting fees and/or speaker honoraria from Biogen, Celgene, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva; travel grants from Biogen, Genzyme, Novartis, and Teva; research grants from the Italian MS Society (Associazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla) and Genzyme. CT: honoraria for speaking and travel grants from Biogen, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck Serono, Bayer-Schering, Teva, Genzyme, Almirall, and Novartis. SH: travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Biogen, Roche, Genzyme, Novartis, CSL Behring. SR: personal fees and non-financial support from Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva. CG: fees as invited speaker or travel expenses for attending meeting from Biogen, Merck-Serono, Teva, Sanofi, Novartis, Genzyme.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Luca Prosperini, Email: luca.prosperini@gmail.com.

Shalom Haggiag, Email: neuroshalom@hotmail.com.

Serena Ruggieri, Email: serena.ruggieri@gmail.com.

Carla Tortorella, Email: carla.tortorella@gmail.com.

Claudio Gasperini, Email: c.gasperini@libero.it.

References

- 1.Rotstein D, Montalban X. Reaching an evidence-based prognosis for personalized treatment of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:287–300. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tur C, Kalincik T, Oh J, et al. Head-to-head drug comparisons in multiple sclerosis: urgent action needed. Neurology. 2019;93:793–809. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mikol DD, Barkhof F, Chang P, et al. Comparison of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a with glatiramer acetate in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (the REbif vs glatiramer acetate in relapsing MS disease [REGARD] study): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:903–914. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70200-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadavid D, Wolansky LJ, Skurnick J, et al. Efficacy of treatment of MS with IFN -1b or glatiramer acetate by monthly brain MRI in the BECOME study. Neurology. 2009;72:1976–1983. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345970.73354.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor P, Filippi M, Arnason B, et al. 250 μg or 500 μg interferon beta-1b versus 20 mg glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:889–897. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudick RA, Confavreux C, Lublin FD, et al. Natalizumab plus interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:402–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen JA, Coles AJ, Arnold DL, et al. Alemtuzumab versus interferon beta 1a as first-line treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380:10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coles AJ, Twyman CL, Arnold DL, et al. Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380:11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61768-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, et al. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Svenningsson A, Frisell T, Burman J, et al. (2022) Safety and efficacy of rituximab versus dimethyl fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis or clinically isolated syndrome in Sweden: a rater-blinded, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(8):693–703. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Cohen JA, et al. Ofatumumab versus teriflunomide in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:546–557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.O’Sullivan D, Wilk S, Michalowski W, Farion K. Using PICO to align medical evidence with MDs decision making models. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metelli S, Chaimani A. Challenges in meta-analyses with observational studies. Evid Based Ment Health. 2020;23:83–87. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VanderWeele TJ. Optimal approximate conversions of odds ratios and hazard ratios to risk ratios. Biometrics. 2020;76:746–752. doi: 10.1111/biom.13197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boster A, Nicholas J, Wu N, et al. Comparative effectiveness research of disease-modifying therapies for the management of multiple sclerosis: analysis of a large health insurance claims database. Neurol Ther. 2017;6:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s40120-017-0064-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braune S, Grimm S, van Hövell P, NTD Study Group et al. Comparative effectiveness of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate versus interferon, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, or fingolimod: results from the German NeuroTransData registry. J Neurol. 2018;265:2980–2992. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Condé S, Moisset X, Pereira B, et al. Dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide for multiple sclerosis in a real-life setting: a French retrospective cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:460–467. doi: 10.1111/ene.13839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Amico E, Zanghì A, Sciandra M, et al. Dimethyl fumarate vs teriflunomide: an Italian time-to-event data analysis. J Neurol. 2020;267:3008–3020. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09959-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buron MD, Chalmer TA, Sellebjerg F, et al. Comparative effectiveness of teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate: a nationwide cohort study. Neurology. 2019;92:e1811–e1820. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guger M, Enzinger C, the Austrian MS Treatment Registry (AMSTR) et al. Oral therapies for treatment of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis in Austria: a 2-year comparison using an inverse probability weighting method. J Neurol. 2020;267:2090–2100. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09811-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hillert J, Tsai JA, Nouhi M, et al. A comparative study of teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate within the Swedish MS Registry. Mult Scler. 2022;28:237–246. doi: 10.1177/13524585211019649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalincik T, Kubala Havrdova E, Horakova D, et al. Comparison of fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide for multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90:458–468. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laplaud D-A, Casey R, Barbin L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of teriflunomide vs dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2019;93:e635–e646. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nehzat N, Mirmosayyeb O, Barzegar M, et al. Comparable efficacy and safety of teriflunomide versus dimethyl fumarate for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurol Res Int. 2021;2021:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2021/6679197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ontaneda D, Nicholas J, Carraro M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dimethyl fumarate versus fingolimod and teriflunomide among MS patients switching from first-generation platform therapies in the US. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;27:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prosperini L, Cortese A, Lucchini M, et al. Exit strategies for “needle fatigue” in multiple sclerosis: a propensity score-matched comparison study. J Neurol. 2020;267:694–702. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermersch P, Suchet L, Colamarino R, et al. An analysis of first-line disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis using the French nationwide health claims database from 2014–2017. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46:10251. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zivadinov R, Kresa-Reahl K, Weinstock-Guttman B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate in patients with relapsing forms of MS in the retrospective real-world Teri-RADAR study. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8:305–316. doi: 10.2217/cer-2018-0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montalban X. Review of methodological issues of clinical trials in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2011;311(Suppl 1):S35–42. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(11)70007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bucello S, Annovazzi P, Ragonese P, et al. Real world experience with teriflunomide in multiple sclerosis: the TER-Italy study. J Neurol. 2021;268:2922–2932. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalincik T, Manouchehrinia A, Sobisek L, et al. Towards personalized therapy for multiple sclerosis: prediction of individual treatment response. Brain. 2017;140:2426–2443. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox EJ, Vasquez A, Grainger W, et al. Gastrointestinal tolerability of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in a multicenter, open-label study of patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MANAGE) Int J MS Care. 2016;18:9–18. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2014-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naismith RT, Wundes A, Ziemssen T, et al. Diroximel fumarate demonstrates an improved gastrointestinal tolerability profile compared with dimethyl fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results from the randomized, double-blind, phase III EVOLVE-MS-2 study. CNS Drugs. 2020;34:185–196. doi: 10.1007/s40263-020-00700-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anglemyer A, Horvath HT, Bero L. Healthcare outcomes assessed with observational study designs compared with those assessed in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000034.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sedgwick P. The ecological fallacy. BMJ. 2011;343. 10.1136/bmj.d4670.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available as an Excel spreadsheet (Appendix.xlsx).