Abstract

We performed a genotypic characterization of seven strains of Mycoplasma fermentans which have been isolated from the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (n = 2), spondyloarthropathy (n = 1), and unclassified arthritis (n = 4). We compared them to three reference strains (strains PG18 and K7 and incognitus strain) and to a clinical isolate from the urethra of a patient with nongonococcal urethritis. The characterization methods included electrophoresis of native DNA, arbitrarily primed PCR, and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis following conventional and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Southern blot analysis with a probe internal to an insertion sequence was performed with the restriction products produced by the last two techniques. No extrachromosomal DNA sequences were detected. The M. fermentans strains identified by these methods did not present a unique profile, but they could be separated into two main categories: four articular isolates were genetically related to PG18 and the three other isolates, the urethral isolate, and the incognitus strain were related to K7. We also looked for the presence of the bacteriophage MAV1 (associated with the arthritogenic property of Mycoplasma arthritidis in rodents) in the M. fermentans strains. MAV1 DNA was not detected in either the clinical isolates or the reference strains of M. fermentans.

The cause of the inflammatory rheumatic disorders, in particular, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), remains unknown. The central mechanism causing these diseases appears to be a break in self-tolerance which could be triggered by environmental factors in genetically predisposed patients. Among these environmental factors, special attention has been given to bacterial infections (2). Mycoplasmas have been considered possible candidates in this regard for many years, since these organisms are known to be responsible for both acute or chronic arthritis in animal species; moreover, they can induce autoimmune phenomena in the host (28, 32). More than 20 years ago Mycoplasma fermentans was suggested as a possible etiologic agent for RA on the basis of the rare isolation of this organism from synovial fluid from patients with the disease (28, 32, 37). However, a role for M. fermentans in RA has never been substantiated, since not all workers could confirm the preliminary culture results.

Many recent studies of interactions between mycoplasmas and the immune system suggest that these organisms may play a role in rheumatic diseases in human (6). Moreover, using a PCR assay, we detected DNA from M. fermentans in synovial specimens from eight (21%) patients with RA, two (20%) patients with spondyloarthropathy, one (20%) patient with psoriatic arthritis, and four (13%) patients with undifferentiated arthritis (26, 27). In a systematic study of detection by culture, we confirmed the presence of viable mycoplasmas in the synovial fluid of patients with various rheumatic conditions, including RA (29). Although we identified different mycoplasma species in that study, the most frequently isolated species was M. fermentans. At this time, we have isolated seven strains of this species.

M. fermentans is being isolated only rarely from clinical specimens. Since its first isolation in 1952 from a subject’s genitourinary tract (24), M. fermentans has been isolated from leukemic bone marrow and from arthritic joints (20, 28, 37). More recently, M. fermentans was detected in several tissues from AIDS patients (17). The heterogeneity of M. fermentans has been demonstrated previously (7, 15, 25). The aim of the present study was to perform a genotypic characterization of articular M. fermentans isolates in order to determine whether strains isolated from the joints of patients with arthritis represent unique strains of the organism; we also compared the isolates to reference strains via genome size determination, arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR), conventional restriction enzyme analysis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and Southern blot analysis. Moreover, it has been shown that the arthritogenicities of some strains of Mycoplasma arthritidis are associated with the presence of bacteriophage MAV1 (34). Because M. arthritidis is relatively close phylogenetically to M. fermentans (18), we considered whether these Mycoplasma species might be infected with similar bacteriophages. Thus, in hybridization assays we sought MAV1 in the seven M. fermentans isolates from the joints of patients with arthritis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates, reference strains, and growth conditions.

Clinical strains have been isolated from synovial fluids collected from 1991 to 1995 in the Department of Rheumatology of the Hôpital Pellegrin, Bordeaux, France. More than 500 synovial fluid specimens were systematically cultured on specific cell-free medium for the detection of mycoplasmas as described previously (29); seven M. fermentans isolates resulted from that analysis. About two-thirds of the synovial fluids were collected from patients with various inflammatory rheumatic disorders: RA, spondyloarthropathies, connective tissue diseases (mainly systemic lupus erythematosus), or unclassified arthritis; one-third were obtained from patients with osteoarthritis, posttraumatic hydrarthrosis, gouty arthritis, or chondrocalcinosis. Interestingly, all mycoplasmas were isolated from patients with inflammatory rheumatic disorders. The clinical and biological features of the patients from whom the M. fermentans strains were isolated are summarized in Table 1. As indicated in a previous report (29), no difference was observed between the patients positive or negative for the presence of M. fermentans within each clinical category of age, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, peripheral blood leukocyte count, synovial fluid cellularity, presence of articular erosions, and overall disease activity. M. fermentans isolates were identified by a growth inhibition test with a specific antiserum (5) and by a PCR assay with primers chosen within an insertion sequence (IS)-like element specific for M. fermentans; the latter were confirmed by hybridization (36). The articular isolates were denominated isolates 1 to 7. An additional clinical isolate, designated isolate 8, was studied, and this isolate was obtained from the urethra of a man with nongonococcal urethritis. Three M. fermentans reference strains were used for comparison: PG18 (ATCC 19989; a descendant of the original isolate from Ruiter and Wentholt [24]), K7 (isolated from cell cultures [20]), and M. fermentans incognitus strain (Mi) (isolated from tissue specimens from an AIDS patient [17]). To seek MAV1, two strains of M. arthritidis were used: Jasmin (ATCC 14124; a highly arthritogenic strain known to be lysogenized by MAV1) was used as a positive control, and low-level-arthritogenic strain PG6 (ATCC 19611; known to be negative for MAV1) was used as a negative control. These strains were kindly provided by Joseph G. Tully, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Frederick, Md. Wild-type strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli were used as negative controls.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and biological features of patients from whom M. fermentans strains were isolateda

| Strain no. | Data for the corresponding patient

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex/age (yr) | Diagnosis | Clinical features | Biological features

|

Disease duration (mo) | |||

| RF | ANA titer | HLA | |||||

| 1 | M/68 | RA | Symmetric polyarthritis | − | − | ND | 12 |

| 2 | F/69 | UA | Monoarthritis following juv. A in the past | ND | ND | ND | 1 |

| 3 | F/48 | UA | Nonerosive oligoarthritis | − | 1:160 | ND | 6 |

| 4 | F/66 | RA | Destructive polyarthritis | + | 1:250 | DR4;7 | 92 |

| 5 | F/63 | UA | Nonerosive symmetric polyarthritis and psoriasis | − | 1:1,000 | B27 + | 60 |

| 6 | F/19 | UA | Acute polyarthritis | − | − | DR1;4 | 1 |

| 7 | F/60 | SpA | Biarthritis of the knees | − | − | B27 − | 9 |

Abbreviations: RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UA, unclassified arthritis; SpA, spondyloarthropathy; juv. A, juvenile arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; +, positive; −, negative; ND, not done; M, male; F, female.

The M. fermentans strains were grown at 37°C on Hayflick modified broth medium supplemented with glucose and on Hayflick agar medium (10). The M. arthritidis strains were grown in Hayflick broth medium supplemented with arginine. The S. aureus and the E. coli strains were grown on brain heart medium.

Cloning of the isolates.

To verify the homogeneity of the clinical isolates, an aliquot of 20 μl of the first-pass culture of each strain was transferred to solid Hayflick agar medium. Three colonies of each culture were separately taken and were cultured in liquid medium. At the log phase of growth in broth culture, the medium was filtered (pore size, 0.22 μm), and 20 μl of the filtrate was then transferred to a new agar plate. This procedure was repeated three times (16). For each isolate, the different clones obtained were compared by AP-PCR assays as described below.

DNA extraction and electrophoretic analysis of undigested DNA.

Genomic DNA was extracted from log-phase broth cultures by the procedure described by Carle et al. (4). The purity and the concentration of DNA were determined spectrophotometrically by determining the 260/280 nm ratio for each preparation. The DNA was stored in 500 μl of distilled water. About 3 μg of undigested DNA of each strain was loaded onto a 0.8% agarose gel, and the gel was run at 60 V for 6 h and stained with ethidium bromide after electrophoresis to verify the integrity of the extracted DNA and to look for the presence of extrachromosomal DNA.

AP-PCR assays.

Five primers were used either alone or in combination for AP-PCR fingerprinting: primers APɛ (5′-CGTTTGCTAC-3′) (30), 1 (5′-AACGCGCAAC-3′) (11), HLWL74 (5′-ACGTATCTGC-3′) (19), 1254 (5′-CCGCAGCCAA-3′) (1), and PH1 (5′-TAGGGATGCA-3′) (9). Amplification was performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (ATGC Biotechnologie, Noisy-Le-Grand, France), 5 μl of 10× buffer (7 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 0.2 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 16 mM ammonium sulfate), dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP each at a concentration of 200 μM, 6 μM primer, and 100 ng of DNA template, as described previously (11). Amplification consisted of a 4-min thermal delay step at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles comprising a 1-min denaturation step at 94°C, a 1-min annealing step at 35°C, a 1-min elongation step at 72°C, and a final 10-min elongation step at 72°C. PCRs were performed with an automated thermocycler (9600; Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.). A negative control, which did not contain DNA template, was processed with each set of samples assayed by AP-PCR. PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. A mixture of pBR328 DNA restricted by BglI and HinfI endonucleases (Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France) was used as a molecular weight marker. Each strain was tested at least twice to ascertain the reproducibility of the method.

Conventional and PFGE restriction enzyme analysis of genomic DNA.

Conventional restriction enzyme analyses were performed by standard procedures with three different enzymes: EcoRI (Gibco BRL, Cergy Pontoise, France), HindIII (Gibco BRL), and XbaI (Gibco BRL). By using the video gel documentation system Imager 2.02 (Appligen Inc., Pleasanton, Calif.), the restriction patterns obtained with EcoRI were analyzed with Gelcompar software (Windows 3.1.1, version 4.0; Applied Math, Kortrijk, Belgium). This software analyzes the percentages of common bands between the different lanes of the gel.

Mycoplasma strains were grown in 50 ml of Hayflick modified medium until the exponential phase of growth in culture. Chloramphenicol was then added to a final concentration of 180 μg/ml. Incubation was prolonged for 6 h to allow the DNA replication in progress to reach completion while inhibiting the reinitiation of DNA replication. Following incubation, the organisms were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 50 min and were washed three times with ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]). The pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and the mixture was then added to an equal volume of 1% molten low-melting-point agarose (SeaPlaque Agarose; FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine). The suspension was mixed and was then distributed in 100-μl aliquots into a Plexiglas mold with multiple wells (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.). The hardened blocks were extruded into 0.5 M EDTA and were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were lysed by adding 1% N-lauroyl sarcosine, and protein digestion was performed by treatment with proteinase K at 56°C for 24 to 48 h. The proteinase K was inactivated by washing the mixture in 10 ml of TE (Tris-EDTA) buffer with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Boehringer Mannheim) at 17.5 μg/ml for 1 h at 37°C a first time and then at room temperature a second time. The agarose blocks were finally washed three times for 1 h in 10 ml of TE buffer with thorough mixing on a rocker platform.

PFGE of full-length mycoplasmal DNA linearized by gamma irradiation was done to evaluate the sizes of the genomes of the different strains studied. For macrorestriction endonuclease analysis, DNA blocks were equilibrated in 1× appropriate restriction enzyme buffer for 1 h at 4°C. Three restriction enzymes were used: BamHI (Gibco BRL), AvaI (Gibco BRL), and BglI (Gibco BRL). These enzymes were chosen because their recognition sequences are rich in C and G and thus provide low numbers of restriction sites on mycoplasma DNA. After an overnight incubation at 4°C with 25 U of enzyme, digestion was conducted at the optimal temperature for 6 h.

PFGE was performed with a contour-clamped homogeneous field electrophoresis system (CHEF-DR III; Bio-Rad, Ivry sur Seine, France). Analysis of full-length DNA was performed in 0.8% agarose gels, with electrophoresis being conducted at 190 V for 18 h with pulse times ranging from 25 to 75 s. DNA restriction fragment analysis was done in 1% agarose gels, with electrophoresis being conducted at 190 V for 20 h with pulse times ranging from 3 to 20 s. After electrophoresis, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide. The sizes of the DNA fragments generated were determined by comparison with bacteriophage lambda ladder PFG marker (New England Biolabs, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom) and with Saccharomyces cerevisiae YNN295 chromosome marker (Bio-Rad) for chromosome size determination.

Southern blot and dot blot analyses.

For Southern blot analysis, electrophoresed restricted DNA (conventional and pulsed-field electrophoresis) was denaturated and transferred from agarose gels to a nylon membrane (GeneScreen; du Pont de Nemours, Paris, France). The membranes were prehybridized for 2 h at 56°C. For dot blot analysis, about 3 μg of total DNA of each strain was directly plotted onto the nylon membrane before prehybridization. Two probes were used: an oligonucleotide (5′-TTCTCCTGTAGTTGATTTTGAA-3′) whose sequence lies within the M. fermentans IS from nucleotides 1079 to 1100 (15) and a 900-bp DNA fragment from MAV1 (kindly provided by Leigh R. Washburn, University of South Dakota School of Medicine, Vermillion). The membranes of the conventional and pulsed-field gels of restricted DNA used for Southern transfer were hybridized with the 5′ end of the IS probe 32P labelled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Gibco BRL). Hybridization was performed overnight at 56°C.

The MAV1 fragment was labelled with 32P by random priming (NonaPrimer kit; Appligene) and was used for Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-restricted DNA patterns and dot blot analysis of total DNA of the 11 M. fermentans strains, the 2 M. arthritidis strains, and the S. aureus and E. coli strains. Hybridizations were performed at different temperatures (56, 42, and 37°C).

Autoradiography was performed in all cases by the standard method with X-ray films (Kodak).

RESULTS

AP-PCR analysis.

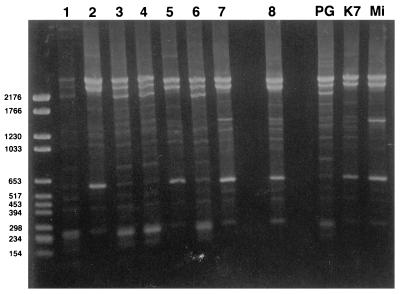

The different colonies obtained from primary cultures of samples from each patient showed a single fingerprint profile, regardless of which AP-PCR primer was used (data not shown). With primers HLWL74, APɛ, and PH1 (Fig. 1), the three reference strains (strains PG18, K7, and Mi) each gave a distinct pattern. With primer 1254, the banding profiles were similar for strains PG18 and K7 but were distinct for strain Mi; for primer 1, strains K7 and Mi exhibited the same pattern and PG18 exhibited one that was different from those of K7 and Mi. According to their banding profiles with the various primers, the eight clinical isolates were compared to the three reference strains. Strains 1, 3, 4, and 6 exhibited profiles identical to that of PG18, while strains 2, 5, and 8 had the same fingerprint as strain K7. The profile of strain 7 was intermediate between those of reference strains K7 and Mi. For example, as indicated in Fig. 1 the patterns obtained with primer PH1 showed a major band of about 600 bp for strains 2, 5, 7, 8, K7, and Mi, while this band was minor for the other strains (Fig. 1). In addition, three major bands were observed at ≥2,200 bp for isolates 1, 3, 4, and 6 and reference strain PG18, while only two bands of the same size were present for isolates 2, 5, 7, 8, K7, and Mi. Moreover, the profiles of isolates Mi and 7 were characterized by a major band at 1,500 bp for Mi plus a band at 1,300 bp for strain 7 (Fig. 1). With the combination of primers, we obtained complex patterns with numerous bands which were not discriminatory.

FIG. 1.

AP-PCR profiles of 11 strains of M. fermentans obtained with primer PH1. The unmarked lane corresponds to the size marker (in base pairs). Lanes 1 to 7, articular isolates; lane 8, urethral isolate; lanes PG (strain PG18), and K7, Mi, references strains.

Analysis of undigested DNA.

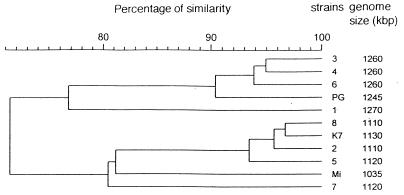

Electrophoresis of undigested DNA and PFGE analysis of full-length DNA did not show extrachromosomal DNA in any clinical isolate or reference strain. Large differences in chromosome length were apparent by the PFGE analyses, however. The genome size of each strain ranged from 1,035 to 1,270 kbp, as indicated in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram obtained with Gel Compar software from RFLP analysis of DNA from the 11 M. fermentans strains digested with EcoRI: seven articular isolates (strains 1 to 7), one urethral strain (strain 8), and three reference strains (PG18 [PG] K7, and Mi). The genome size of each strain, as determined by PFGE, is indicated on the right.

Conventional restriction enzyme analysis.

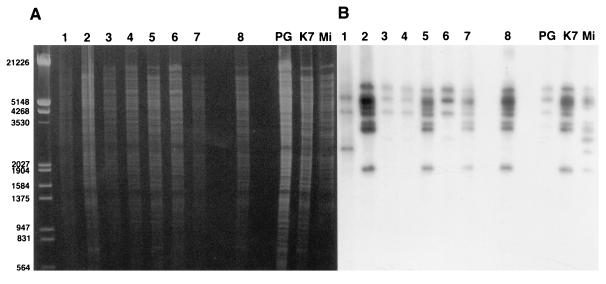

The electrophoretic patterns of the restriction fragments obtained after the digestion of DNA with each of the three restriction enzymes showed large numbers of bands (the profiles provided by EcoRI are presented in Fig. 3A). A dendrogram derived from the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis from EcoRI digestion distinguished two main clusters: one comprised strains 1, 3, 4, and 6 and reference strain PG18, and the second comprised strains 2, 5, 7, and 8 and reference strains K7 and Mi (Fig. 2). In the cluster that included strain K7, the major differences in the banding patterns were seen for strain Mi and strain 7. In the PG18 cluster, strain 1 appeared to be distinct from the other strains.

FIG. 3.

Southern blot hybridization of the IS probe to EcoRI digests of DNAs from 11 strains of M. fermentans. The unmarked lane corresponds to the size marker (in base pairs) (clone of bacteriophage lambda digested with EcoRI and HindIII). Lanes 1 to 7, articular isolates, lane 8, urethral isolate; lanes PG (strain PG18) K7, and Mi, references strains. (A) Ethidium bromide-stained 0.8% agarose gel. (B) Autoradiography of a Southern blot of the gel in panel A for the IS.

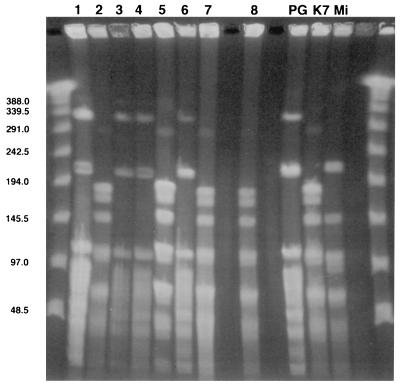

PFGE analysis.

Digestion of DNA with the restriction enzymes BglI, AvaI, and BamHI gave different band profiles for each of the three reference strains (strains PG18, K7, and Mi). The patterns obtained with BglI are presented in Fig. 4. The pattern for strain PG18 differed from that for strain K7 by 7, 11, and 13 bands when AvaI, BglI, and BamHI, respectively, were used; the band pattern of strain PG18 differed from that of strain Mi by six bands when AvaI and BglI were used to digest the DNA and by nine bands when BamHI was used to digest the DNA. The band pattern of strain Mi differed from that of strain K7 by three bands regardless of whether the AvaI or the BamHI enzyme was used and by four bands when the BglI enzyme was used. Among the clinical isolates, the patterns of strains 1, 3, 4, and 6 were identical to that of strain PG18, while strains 2, 5, 7, and 8 exhibited the same profile as reference strain K7 after digestion with each of the three enzymes.

FIG. 4.

PFGE of BglI restriction fragments from DNAs from the 11 M. fermentans strains (ethidium bromide-stained gel). Unmarked lane, molecular size marker (in kilobase pairs); lanes 1 to 7, articular isolates; lane 8, urethral isolate; lanes PG (strain PG18), K7, and Mi, reference strains.

Thus, according to the guidelines proposed for epidemiological interpretation by Tenover et al. (33), clinical strains 1, 3, 4, and 6 and reference strain PG18 were indistinguishable. Strains 2, 5, 7, and 8 and reference strain K7 were also indistinguishable. Strain Mi appeared to be possibly related to the K7 group. The two clusters defined above were clearly unrelated, because their patterns differed by 6 to 13 bands.

IS fingerprinting.

Because the oligonucleotide of the IS used as probe did not contain any restriction site for the enzymes used, each band observed on Southern blots corresponds to at least one copy of the IS. Hybridization showed that the IS is repeated several times in the genomes of M. fermentans strains, as described previously (17, 25).

After conventional electrophoresis, Southern blot analyses for IS sequences provided three different patterns for the three reference strains following digestion with the EcoRI (Fig. 3B) and HindIII restriction enzymes. However, with HindIII, only one band distinguished the patterns for strains Mi and K7. With XbaI, reference strains K7 and Mi showed similar profiles, while strain PG18 shared four bands with this profile and exhibited three additional bands (data not shown). The IS occurred 4 to 7 times in strain PG18 and 7 to 12 times in strains K7 and Mi, depending on the restriction enzyme used. Clinical isolates 2, 5, 7, and 8 exhibited hybridization profiles identical to that given by reference strain K7; strains 3, 4, and 6 had profiles similar to that of reference strain PG18, and strain 1 showed a distinct banding pattern. This latter clinical isolate differed from the cluster of strains 3, 4, 6, and PG18 by two bands at the lower level of the analytical gel when EcoRI was used (Fig. 3B) and by one band when HindIII and XbaI were used (data not shown).

After PFGE, the Southern blot analysis with the IS probe showed different patterns for the three reference strains when the BamHI and BglI restriction enzymes were used to digest the DNAs. With BamHI, only two bands distinguished the pattern of strain Mi from that of strain K7, while strain PG18 exhibited a completely different pattern. With AvaI, strains K7 and Mi provided similar hybridization profiles, while the profile of strain PG18 was completely different from the patterns for either of those strains (data not shown). Among the clinical isolates, the patterns of strains 2, 5, 7, and 8 appeared to be similar to that of strain K7 after digestion with each of the three enzymes, while strains 1, 3, 4, and 6 were identical to reference strain PG18 when DNA was digested with BamHI and AvaI. With BglI, strains 3, 4, and 6 gave hybridization profiles similar to that of reference strain PG18, but the pattern for strain 1 exhibited one additional band.

Southern blot and dot blot analyses with an MAV1 probe.

No hybridization signal was obtained for any M. fermentans strain or for M. arthritidis PG6, S. aureus, or E. coli with the MAV1 probe; however, three bright bands were seen in hybridizations with this probe to the restricted DNA of M. arthritidis Jasmin (data not shown), confirming that MAV1 was present in that strain. Similar features were observed regardless of the hybridization conditions used, indicating that MAV1 was not present in either articular isolates or other strains of M. fermentans. These results were confirmed by dot blot analysis; i.e., only DNA from the Jasmin strain gave a hybridization signal with the MAV1 probe (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The strains of M. fermentans studied here were isolated from the synovial fluid of seven patients with various inflammatory arthritides.

Although the arthritogenicity of M. fermentans has been demonstrated in experimental animal models (22), detection of the bacterium in the joints of arthritic patients does not demonstrate that the organism is involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. Isolation of viable M. fermentans strains from synovial samples of arthritic patients, however, provides a unique opportunity to determine whether these articular isolates comprise a single strain of M. fermentans, a situation which might support an association with disease.

Several techniques for genome characterization have been applied to mycoplasmas. Restriction endonuclease analysis has been used to evaluate the degree of genotypic heterogeneity among strains of different mycoplasmas species (21), including M. fermentans strains (25). Various strains of M. fermentans have previously been compared by Southern blot analysis in which the IS fragment was used as a probe (7, 15, 25). PFGE has been used to determine the genome sizes of the two Ureaplasma urealyticum biovars (23). AP-PCR has been used by Grattard et al. (11) to distinguish the U. urealyticum biovars and by Ursi et al. (34) to identify the two M. pneumoniae groups (34). We applied these techniques to the characterization of our articular isolates.

The clones obtained from the first pass of the articular M. fermentans isolates showed a single profile. However, because M. fermentans is so fastidious, it is impossible to know whether the organism that we obtained from each synovial fluid sample by culture represents only one of multiple strains present in the joint or whether a single strain was originally present. In one patient (from whom strain 7 was isolated), a U. urealyticum strain was isolated from the same synovial fluid specimen from which the M. fermentans strain studied here was isolated. This indicates that different mycoplasma species and perhaps different strains of the same species may be present in the same joint.

Surprisingly, large differences in chromosome size (up to 235 kbp, or nearly 20% of the genome) were observed between the two groups of clinical isolates. However, similar differences have been observed among strains of the same bacterial species. For instance, Robertson et al. (23) showed that the genome sizes of the different biovars of U. urealyticum may vary from 760 to 1,140 kbp. For M. fermentans strains, one explanation for the difference in overall genome size may be the presence of different numbers of copies of the IS, whose size was evaluated to be 1,405 bp (15). Important variations in the number of copies of repetitive DNA elements have been shown to represent about 8% of the size of the genome of M. pneumoniae (14). Indeed, more than 10 copies of the IS were observed by Southern blotting in the group of strains in which the size of the genome was the smallest, while only 6 or 7 copies of the IS were observed in the strain group characterized by the largest genome size. Other repeated sequences or unidentified lysogenic viruses also might explain genome size differences. Interestingly, a new repeated sequence has recently been identified in M. fermentans by Calcutt and Wise (3). Four copies of this large repeated sequence (up to 25 kbp) have been found in strain PG18; thus, this element can account for more than 10% of the genome size.

Although we used many different methods to characterize the genomes of the M. fermentans clinical isolates, all of them provided comparable results. Overall, the results obtained by the various techniques allow separation of the M. fermentans strains studied into two main categories. Four articular isolates (isolates 1, 3, 4, and 6) were genetically related to reference strain PG18, while the three other articular isolates (isolates 2, 5, and 7), the urethral isolate (isolate 8), and reference strain Mi were related to reference strain K7. However, some heterogeneities were observed within each group. Among the strains related to PG18, strain 1 appeared to be the most variant. Among the group of strains related to K7, reference strain Mi and isolate 7 exhibited the largest differences. Finally, all results appeared to be well summarized by the dendrogram presented in Fig. 2. Thus, M. fermentans strains isolated from the joints of arthritic patients do not correspond to a single unique strain of M. fermentans.

No correlation between the groups of clinical isolates and the clinical spectrum for the patients at issue could be identified due to the small numbers of strains studied. However, we did note that the four strains corresponding to reference strain PG18 were isolated from patients with RA or patients with symmetrical polyarticular undifferentiated arthritis (patients 1, 3, 4, and 6), while the strains related to reference strain K7 were isolated from a patient with reactive arthritis (patient 7), one patient with unclassified monoarthritis of the lower limbs (patient 2), and one patient with unclassified polyarthritis who was HLA-B27 positive and who had significant levels of antinuclear antibodies (patient 5).

It is of interest that four of our clinical isolates (three from synovial specimens and one from the genital tract) were closely related to reference strain K7. This strain was isolated from a cell culture and thus is considered a cell culture contaminant. In addition to the unusual manner in which reference strain Mi was isolated by Lo et al. (17), similarities between the resistance of strains Mi and K7 to aminoglycosides have been considered support for the argument that Mi is also, in fact, a cell culture contaminant (13). Our study demonstrates that strains of M. fermentans which are genomically related to strain K7 are not simply cell culture contaminants.

It has been demonstrated for other microorganisms implicated in joint diseases that different strains of the same species do not necessarily show similar arthritogenic properties. Molecules implicated in pathogenesis processes are frequently encoded by genes carried on plasmids or by infecting bacteriophages. For example, it has been demonstrated that strains of Shigella implicated in reactive arthritis carry a 2-MDa plasmid (31). The arthritogenicities of some strains of Yersinia have been attributed to the presence of a plasmid encoding different proteins implicated in pathogenicity (12). However, plasmids have been described in only a few mycoplasma species, and extrachromosomal viruses are rare (8). In our study, no extrachromosomal DNA was observed in any strain of M. fermentans examined.

Elements integrated into the bacterial chromosome, such as ISs and viruses, might confer special properties on the organism and may explain the pathogenic capabilities of specific strains of a given microorganism. Such an IS has been discovered in M. fermentans (15). Interestingly, the deduced amino acid sequence of an open reading frame encoded within this IS shows homology to the amino acid sequence of an extracellular V4 domain of the CD4 molecule of the human T lymphocyte. However, this IS was found in all M. fermentans strains studied and thus cannot explain the special pathogenicities of some strains; the presence of an IS in the genome might determine or alter expression of a particular gene. The lysogenic bacteriophage MAV1 was identified by Voelker et al. (35) because some strains of M. arthritidis occasionally included an extrachromosomal form of the virus. By comparing the arthritogenicities of 20 strains of M. arthritidis in rats, the investigators showed that these strains could be separated into two groups, a highly arthritogenic group and a group with a low level of virulence. Using a Southern blot assay similar to the one used by Voelker et al. (35), we did not detect MAV1 in any of the M. fermentans strains isolated from synovial fluid of arthritis patients or in reference strains. With the lowest hybridization temperatures that we used, we might have detected lysogenic viruses whose sequences were homologous with the MAV1 sequence. However, this study does not eliminate the possibility that a different, unrelated lysogenic virus infects some strains of M. fermentans.

In conclusion, the genotypic characterization of the seven M. fermentans strains isolated from the synovial fluid of patients with inflammatory rheumatic disorders showed that these are not a single unique strain of M. fermentans species. They are distributed into two main categories, one related to reference strain PG18 and the other related to reference strain K7. This study did not reveal among the strains identified a special characteristic(s) that could be associated with any given arthritogenic property. Other approaches are being developed to determine whether M. fermentans behaves as an opportunistic or a pathogenic agent in patients with rheumatic disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Conseil Régional d’Aquitaine and a grant from the Association de Recherche sur la Polyarthrite.

We thank Joseph Marie Bové, Monique Garnier, and Colette Saillard for useful advice and Patricia Carle for technical assistance in chromosome size determination. We are very grateful to Alan P. Hudson (Wayne State University School of Medicine) for assistance with English-language editing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopyanz N, Bukanov N O, Westblom T U, Kresovitch S, Berg D E. DNA diversity among clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori detected by PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5137–5142. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behar S M, Porcelli S A. Mechanisms of auto immune disease induction. The role of the immune response to microbial pathogens. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:458–476. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calcutt M J, Wise K S. Program and abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1997. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. The Mycoplasma fermentans genome contains multiple copies of a novel 25 kb element, abstr. G-21; p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carle P, Saillard C, Bové J M. DNA extraction and purification. In: Razin S, Tully J G, editors. Methods in mycoplasmology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1983. pp. 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clyde W A. Mycoplasma species identification based upon growth antisera. J Immunol. 1964;92:958–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole B C. Mycoplasma interactions with the immune system: implications for disease pathology. ASM News. 1996;62:471–475. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson M S, Hayes M M, Wang R Y, Armstrong D, Kundsin R B, Lo S C. Detection and isolation of Mycoplasma fermentans from urine of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:511–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dybvig K. Characterization of virus genomes and extrachromosomal elements. In: Razin S, Tully J G, editors. Molecular and diagnostic procedures in mycoplasmology. 1. Molecular characterization. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1995. pp. 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fremy G, de Barbeyrac B, Charron A, Renaudin H, Bébéar C. Program and abstracts of the 95th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, 1995. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. DNA analysis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae by pulsed field gel electrophoresis, abstr. G-48; p. 305. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freundt E A. Culture media for classic mycoplasmas. In: Razin S, Tully J G, editors. Methods in mycoplasmology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1983. pp. 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grattard F, Pozzetto B, de Barbeyrac B, Renaudin H, Clerc M, Gaudin O, Bébéar C. Arbitrarily-primed PCR confirms the differentiation of strains of Ureaplasma urealyticum into two biovars. Mol Cell Probes. 1995;9:383–389. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1995.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gripenberg-Lerche C, Skurnick M, Toivanen P. Role of YadA-mediated collagen binding in arthritogenicity of Yersinia enterolitica serotype O:8: experimental studies with rats. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3222–3226. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3222-3226.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannan P C T. Observations on the possible origin of Mycoplasma fermentans incognitus strain based on antibiotic sensitivity tests. J Antimicrob Chem. 1997;39:25–30. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li B C, Hermann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu W S, Wang R Y U, Liou R S, Shih J W K, Lo S C. Identification of an insertion-sequence-like genetic element in the newly recognized human pathogen Mycoplasma incognitus. Gene. 1990;93:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90137-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology Subcommittee on the Taxonomy of Mollicutes (Division Tenericutes) Revised minimum standards for description of new species of the class Mollicutes. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:605–612. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo S C, Shih J W K, Newton III P B, Wong D M, Hayes M M, Benish J R, Wear D J, Wang R Y H. Virus-like infectious agent (VLIA) is a novel pathogenic mycoplasma. Mycoplasma incognitus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41:586–600. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.41.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maniloff J. Phylogeny of mycoplasmas. In: Maniloff J, McElhaney R N, Finch L R, Baseman J B, editors. Mycoplasmas. Molecular biology and pathogenesis. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazurier S I, Wernars K. Typing of listeria strains by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:499–505. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy W H, Ertel I J, Zarafonetis C J D. Virus studies of human leukemia. Cancer. 1965;18:1329–1344. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196510)18:10<1329::aid-cncr2820181020>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Razin S, Tully J G, Rose D L, Barile M F. DNA cleavage patterns as indicators of genotypic heterogeneity among strains of Acholeplasma and Mycoplasma species. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:1935–1944. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-6-1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivera J A, Yáñez A, Cedillo L. Program and abstracts of the 95th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1995. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. Experimental arthritis produced by Mycoplasma fermentans in rabbits, abstr. G-36; p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson J A, Pyle L, Stemke G W, Finch L R. Human ureaplasmas show diverse genome size by pulsed-field electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1451–1455. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.6.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruiter M, Wentholt H M M. The occurrence of a pleuropneumonia-like organism in fuso-spirillary infections of the human genital mucosa. J Invest Dermatol. 1952;18:313–325. doi: 10.1038/jid.1952.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saillard C, Carle P, Bové J M, Bébéar C, Lo S C, Shih J W K, Wang R Y H, Rose D L, Tully J G. Genetic and serologic relatedness between Mycoplasma fermentans strains and a mycoplasma recently identified in tissues of AIDS and non AIDS patients. Res Virol. 1990;141:385–395. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(90)90010-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaeverbeke T, Gilroy C B, Bébéar C, Dehais J, Taylor-Robinson D. Mycoplasma fermentans in joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other joint disorders. Lancet. 1996;347:1418. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaeverbeke T, Gilroy C B, Bébéar C, Dehais J, Taylor-Robinson D. Detection of Mycoplasma fermentans, but not M. penetrans, by PCR assays in synovial samples from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic disorders. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:824–828. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.10.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaeverbeke T, Vernhes J P, Lequen L, Bannwarth B, Bébéar C, Dehais J. Mycoplasmas and arthritis. Rev Rhum (Eng Ed) 1997;64:120–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaeverbeke T, Renaudin H, Clerc M, Lequen L, Vernhes J P, de Barbeyrac B, Bannwarth B, Bébéar C, Dehais J. Systematic detection of mycoplasmas by culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedures in 209 synovial fluid samples. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:310–314. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scieux C, Grimont F, Regnault B, Bianchi A, Kowalski S, Grimont P A D. Molecular typing of Chlamydia trachomatis by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90197-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stieglitz H, Lipsky P. Association between reactive arthritis and antecedent infection with Shigella flexneri carrying a 2-Md plasmid and encoding an HLA-B27 mimetic epitope. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1387–1391. doi: 10.1002/art.1780361010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor-Robinson D, Schaeverbeke T. Mycoplasmas in rheumatoid arthritis and other human arthritides. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:781–782. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.10.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ursi D, Ieven M, Van Bever H, Quint W, Niesters H G M, Goossens H. Typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae by PCR-mediated DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2873–2875. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2873-2875.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voelker L L, Weaver K E, Ehle L J, Washburn L R. Association of lysogenic bacteriophage MAV1 with virulence of Mycoplasma arthritidis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4016–4023. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4016-4023.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang R Y H, Hu W S, Dawson M S, Shih J W K, Lo S C. Selective detection of Mycoplasma fermentans by polymerase chain reaction and by using a nucleotide sequence within the insertion sequence-like element. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:245–248. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.1.245-248.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams M H, Brostoff J, Roitt I M. Possible role of Mycoplasma fermentans in pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1970;ii:277–280. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]