Abstract

A PCR-based test was optimized for the detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum from neonatal respiratory specimens, with primers directed against the multiple-banded antigen gene (L. J. Teng, X. Zheng, J. I. Glass, H. Watson, J. Tsai, and G. H. Cassell, J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1464–1469, 1994). Endotracheal tube aspirates (225) from 103 low-birth-weight neonates (<1,250 g) were taken, when possible, at days 0, 4, and 14 after birth and examined by culture and by PCR. Of 77 specimens positive by either method, 73 were detected by PCR and 60 were detected by culture. Overall, 36% of the neonates were positive for U. urealyticum by either method. Of 16 patients with PCR-positive–culture-negative results, 13 had positive cultures at another sampling point, and one additional patient had a twin with positive cultures. Of 11 patients with day 0 specimens positive by PCR alone, 9 subsequently became culture positive, demonstrating the utility of this test in early detection. Multiple serovars were present in over 50% of positive specimens, with serovars 3 and 14 in combination being most prevalent. The amplicon size generated from the specimen by PCR correctly predicted the biovars isolated in over 85% of positive specimens. Thus, this PCR test was valuable in allowing early detection of U. urealyticum in neonatal respiratory specimens, as well as in providing biovar information.

Airway colonization with Ureaplasma urealyticum has been associated with intrauterine lung disease (11), neonatal pneumonia (10), and an increased risk for developing chronic lung disease (CLD) of prematurity (22). The prevalence of clinical disease associated with U. urealyticum is probably underestimated due to the limitations of laboratory diagnosis. U. urealyticum is a fastidious organism requiring vigorously quality-controlled medium for cultivation and several days of incubation. These procedures are costly and laborious.

The treatment of neonatal pneumonia associated with U. urealyticum is predicated upon rapid detection of infection. Further, prevention of U. urealyticum-associated CLD may require prophylactic antibiotics to be administered to high-risk infants or prompt detection of the agent and treatment. It is evident that strategies to initiate administration of prophylactic or therapeutic antibiotics must include rapid diagnosis of U. urealyticum. A more expedient test, such as PCR, would be beneficial.

Several PCR methodologies for the detection of Ureaplasma, targeting 16S rRNA (12), urease (13, 24), and multiple-banded (MB) antigen (18) gene sequences, have been described elsewhere. The assay described by Teng et al. (18) utilized primers directed against the 5′ region of the MB antigen gene. The advantages to this assay included (i) detection of all 14 serovars of Ureaplasma, (ii) lack of detection of product from 17 other mycoplasma species including phylogenetically closely related species such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and (iii) distinction of amplicons from biovar 1 strains (serovars 1, 3, 6, and 14) from amplicons from biovar 2 strains (serovars 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13) (403 versus 448 bp, respectively).

Studies assessing the utility of PCR in neonatal respiratory specimens are very limited (1, 3, 5, 13) and have shown varying degrees of concordance with culture results. This study was designed to optimize and validate a PCR assay for detection of U. urealyticum, with the previously described (18) primer set targeting the MB antigen gene. The development of a sensitive PCR assay could provide rapid results to clinicians, thus allowing the effective design of treatment trials to assess the role of this organism in the subsequent development of lung disease in this patient group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

The specimens used to validate the PCR assay were collected as part of a larger study, examining the benefit of α1-antitrypsin therapy for the prevention of CLD in premature neonates (15). Because U. urealyticum has been associated with an increased risk of developing CLD, endotracheal tube aspirates (ETTas) were taken from the enrolled patients for U. urealyticum testing. ETTas were taken by direct suction, transported undiluted in sterile containers, and set up within 24 h. The aspirated mucus was inoculated into 2 ml of 10C broth (14), and aliquots were removed and frozen at −70°C for later analysis by PCR to ensure that PCR and culture would be performed on the same sample mixture. In total, 225 ETTas from 103 low-birth-weight neonates (<1,250 g) were analyzed by culture and by PCR. The neonates were sampled (when possible) at days 0, 4, and 14 after birth, with 45 of the 103 patients being sampled at all time points.

Culture of U. urealyticum.

All clinical specimens were cultured by standardized methodology in 10C medium (14) for Ureaplasma and Hayflick medium (6) for Mycoplasma hominis. Serial 10-fold dilutions (10−1 to 10−3) of the inoculated 10C broth were made in urea and arginine broths, and as well, an A8 and a Hayflick agar plate (14) (prepared in-house) were inoculated. All tubes were incubated aerobically, and plates were incubated anaerobically, at 37°C. Broths showing a pH shift (yellow to red) were frozen at −70°C for further characterization. The corresponding plates were read to confirm the presence of brown colonies of Ureaplasma or conventional large colonies. Negative broths and plates were subcultured after 48 h to a new broth and plate. All broths were read twice daily, and the total incubation time for the cultures was 10 days. M. hominis was identified by the immunoperoxidase assay (20). All media were prepared and extensively quality controlled in-house.

Serotyping of U. urealyticum isolates.

Frozen positive broths were thawed and inoculated onto an A8 plate without calcium chloride and incubated anaerobically for 48 h at 37°C. Agar blocks of Ureaplasma culture were cut, placed in wells of a tissue culture plate (24 well), and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.01% thimerosal. Specific antisera to the various ureaplasma serotypes, prepared with rabbits by our laboratory (19), were added to consecutive wells, and the serotype was determined by immunoperoxidase testing (20).

PCR. (i) PCR optimization.

PCR amplification conditions were optimized in our laboratory (i) to maximize the sensitivity of the assay with product detection by ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel electrophoresis and (ii) to incorporate the dUTP–uracil N-glycosylase system for the prevention of carryover contamination. U. urealyticum serotype 3 DNA (extracted from a broth culture with a known titer by a guanidine isothiocyanate-based procedure as described below) equivalent to 10 color-changing units (CCU)/reaction was used to test various buffer compositions. With a PCR optimization kit (Opti-prime; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), a total of 12 buffers were tested with varying pHs and KCl and MgCl2 compositions. Once these parameters were optimized (with 200 μM [each] dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP [Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d’Urfé, Quebec, Canada]), dUTP (Amersham, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) was substituted for dTTP and concentrations of dUTP ranging from 200 to 1,000 μM were tested in parallel with the preoptimized deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix to determine the optimal concentration of dUTP in the assay. Finally, to determine the optimal annealing temperature, a gradient of annealing temperatures ranging from 55 to 65°C (Gradient 96 Robocycler; Stratagene) was tested.

To test the sensitivity of the optimized assay, serial 10-fold limiting dilutions of the organism were made in saline (in duplicate), 100-μl aliquots were extracted and resuspended in 100 μl of DNase-, RNase-, protease-free water (5 prime-3 prime Inc., Boulder, Colo.), and 10 μl was used as a template in the optimized PCR. To determine the potential effects of specimen and/or 10C broth on the assay sensitivity, the same procedure was repeated with pooled ETTas (negative by culture and by preliminary PCR screening) or 10C broth as the diluent in the serial dilutions.

(ii) Specimen extraction.

A guanidine isothiocyanate extraction procedure with isopropanol precipitation was used to obtain DNA from the specimens. We have previously demonstrated the utility of this procedure with respiratory specimens (8), and it is the basis for many commercialized DNA extraction kits. To 100-μl specimen aliquots, 4 volumes of extraction buffer was added (5.75 M guanidine thiocyanate, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 50 μg of glycogen per ml, and 1% β-mercaptoethanol [added immediately prior to use]), and the mixture was vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After the addition of 500 μl of isopropanol, tubes were vortexed and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm (Eppendorf microcentrifuge) for 30 min, and the supernatants were decanted carefully. DNA pellets were washed with 80% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in 25 μl of water (5 prime-3 prime). Extraction reagents were of molecular grade and were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.) or Boerhinger Mannheim (Laval, Quebec, Canada) unless otherwise stated.

(iii) Amplification.

The preoptimized conditions used to test the study specimens were as follows: 50-μl reaction mixtures consisting of 10 mM Tris (pH 8.3); 50 mM KCl; 4 mM MgCl2 (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada); 200 μM (each) dATP, dGTP, and dCTP; 800 μM dUTP; 0.5 U of uracil N-glycosylase (Amersham); 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Roche Diagnostic Systems); 10 μl of template; and 30 pmol each of primers UMS-125 (GTA TTT GCA ATC TTT ATA TGT TTT CG) and UMA226 (CAG CTG ATG TAA GTG CAG CAT TAA ATT C) (18) (synthesized by General Synthesis and Diagnostics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) were set up. The reaction mixtures were covered with mineral oil and subjected to the following thermal cycling parameters in the Robocycler 40 (Stratagene): 1 cycle of 50°C for 5 min (for uracil N-glycosylase activity); 1 cycle of 95°C for 4 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 60°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 3 min. Negative controls (saline, extracted with the specimens) were included with each run and comprised 10% of the total number of reaction mixtures. Also included with each run was a positive control, equivalent to approximately 10 CCU of U. urealyticum.

(iv) PCR product detection.

After thermal cycling, samples (15 μl) were immediately subjected to electrophoresis through a 1.5% agarose gel (Mandel Scientific, Guelph, Ontario, Canada) with 0.3 μg of ethidium bromide (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) per ml in Tris-borate-EDTA (Sigma) at 80 V for 1 h. A DNA product band of 403 bp (biovar 1) or 448 bp (biovar 2) in size, as visualized by UV illumination, was considered positive.

A stringent PCR protocol, to prevent contamination of reactions, including (i) physical separation of the reagent aliquoting, specimen preparation, amplification, and product detection areas; (ii) the inclusion of the uracil N-glycosylase–dUTP system for prevention of carryover contamination; and (iii) the use of filter-plugged tips and other precautions as previously described (7), was adhered to.

(v) PCR inhibition rate in spiked ETTas.

In order to assess the potential in our assay for inhibitors of the PCR to be present in DNA extracts from ETTas, a subset of samples negative by PCR (n = 115) was retested by adding U. urealyticum DNA, equivalent to a low number of organisms (approximately 10 to 20 CCU), to the reactions mixtures.

RESULTS

Limit of assay sensitivity.

Optimization of the reaction and cycling conditions permitted the detection of as few as 0.1 to 1 CCU of U. urealyticum in a PCR as assessed by serial dilutions of the organism in saline. This limit of detection was not compromised when serial dilutions of the organism were performed in pooled ETTas (negative for the organism by PCR and by culture) or in 10C broth. By extrapolation, the lower limit of sensitivity of this assay would be equivalent to approximately 101 to 102 CCU/ml of tracheal secretions. The PCR assay detected all 14 serovars of U. urealyticum as previously described (18).

Detection of U. urealyticum in neonatal ETTas.

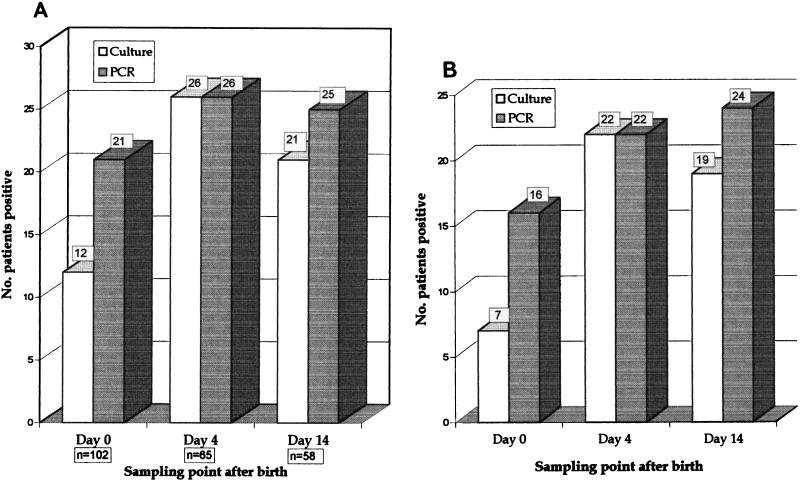

Of 103 neonates (225 ETTas) screened for U. urealyticum, 38 patients (77 specimens) yielded positive results (36%) by culture and/or PCR (Table 1). Overall, 32 patients had positive results by both methods in at least one of the specimens, and 3 patients each had results positive by PCR only or by culture only. M. hominis was cultured and serologically identified for three (3%) patients. There were 17 specimens from 16 patients that were positive for U. urealyticum by PCR alone. Of these 16 patients, 13 had cultures positive at another sampling time, and one additional patient had a twin with positive cultures. The PCR test detected approximately twice as many positive samples as culture at day 0 after birth but was similar to culture at the day 4 and 14 sampling points (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Concordance of results for detection of U. urealyticum in ETTas

| Result | No. of specimens with culture result

|

Total no. of specimens | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| PCR positive | 56 | 17 | 73 |

| PCR negative | 4 | 148 | 152 |

| Total | 60 | 165 | 225 |

FIG. 1.

(A) Detection of U. urealyticum by two methodologies with all results over 14 days being shown. The total numbers of patients with ETTas positive for U. urealyticum by culture and by PCR at the three sampling points after birth are shown. The number of patients sampled is shown below each sampling point. (B) Detection of U. urealyticum by two methodologies, with only results for patients sampled at all three time points being shown. There were 45 patients who had samples taken at all three time points. The comparative results for these patients are shown.

Inhibition rate in ETTas.

The number of specimens containing inhibitors to the PCR process was 8 of 115 (7%), as determined by retesting a subset of negative specimens with the addition of a low concentration of U. urealyticum DNA.

Distribution of U. urealyticum serotypes.

U. urealyticum serotypes 3 and 14 in combination were isolated most frequently (13 patients), followed by serotypes 3 (4 patients) and 6 (4 patients) alone (Table 2). Multiple serotypes were found in over 50% of positive patients. Serotypes comprising biovar 1 (parvo biovar) predominated (27 patients) over those comprising biovar 2 (T960 biovar) (10 patients). PCR product size and isolate serotype information was available for 32 of 35 patients. Of these, the PCR product size generated from the specimens correctly predicted the biovar of U. urealyticum isolated in culture for 28 of 32 patients (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of U. urealyticum serovars isolated and comparison with sizes of amplicons generated by PCR from the specimensa

| Serotypes | Biovar(s) | No. of patients | PCR product size(s) (bp) | Biovar(s) predicted by PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3, 14 | 1 | 13 | 403 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 4 | 403 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 | 4 | 403 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 448 (1), neg (1) | 2, NA |

| 1, 6, 13 | 1, 2 | 1 | 403 | 1 |

| 3, 13 | 1, 2 | 1 | 403 | 1 |

| 1, 14 | 1 | 1 | 403 | 1 |

| 4, 6 | 1, 2 | 1 | 403, 448 | 1, 2 |

| 2, 11 | 2 | 1 | neg | NA |

| 6, 14 | 1 | 1 | 403 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 403, 448 | 1, 2 |

| 9 | 2 | 1 | 448 | 2 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 448 | 2 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 403 | 1 |

| 12 | 2 | 1 | 403, 448 | 1, 2 |

| ND | ND | 1 | 403 | 1 |

ND, not done, as isolate failed to grow upon subculture. NA, not available, as PCR result was negative. neg, negative.

DISCUSSION

Although the precise role of U. urealyticum in neonatal respiratory disease has not been firmly established, there is strong support in the literature for a causal role in cases of neonatal pneumonia (10, 21). Serological studies have shown that neonates with respiratory disease and elevated antibody responses to U. urealyticum have increased mortality rates (9). A recent meta-analysis found that airway colonization with U. urealyticum was associated with an increased (1.72-fold) relative risk of developing CLD in premature neonates (22). At present, the benefits and risks of antibiotic treatment of colonized neonates are unclear. A sensitive, rapid test providing early detection of the organism would be useful in clinical trials studying the efficacy of early antibiotic intervention.

In this study, 36% of 103 premature neonates were colonized with U. urealyticum as detected by culture and/or PCR. Other studies using PCR for U. urealyticum detection in neonatal respiratory specimens have reported prevalence rates of 3 to 13% (3, 5, 13). The rate may have been higher in our study due to a number of factors including (i) the high-risk population sampled (<1,250 g in weight), (ii) the testing of multiple specimens from the majority of patients, and (iii) the method of sample collection, in that neat tracheal aspirate, as opposed to saline lavage, was inoculated into 10C broth for culture and PCR testing. Our incidence is comparable to the 33% ureaplasma colonization rate previously reported for very low birth weight neonates (16).

The fact that multiple specimens were available from most patients was helpful in analyzing results that were positive by PCR but not by culture. For 13 of 16 patients (14 specimens), cultures were positive at another sampling point, suggesting that the PCR results for these patients were likely true positive results. One of the most promising observations in this study was that PCR appeared to be more sensitive than culture in the early (day 0) specimens. Of 45 patients who had specimens taken at all of the sampling points, PCR detected the organism in over twice the number of patients (16 versus 7) in the day 0 specimens, and all but one of the 9 patients with discrepant day 0 results subsequently became positive by culture. If neonates acquire ureaplasmas during birth, the organism would be at a low concentration on day 0 and increase over time. Thus, a rapid PCR assay could be of benefit in the design of antibiotic treatment trials in which early diagnosis is important.

The PCR inhibition rate, as assessed by the lack of amplification of a low copy number of U. urealyticum DNA targets added to negative specimens, was reasonably low in this study, at less than 7% of specimens. We have previously reported the utility of the guanidine isothiocyanate-based DNA extraction procedure for use with respiratory specimens (8). In specimen extracts that contain inhibitors, inhibition may be overcome by a 1-in-5 or a 1-in-10 dilution of the DNA in water in the majority of cases. The odd specimen, including two of the four culture-positive–PCR-negative samples from this study, is extremely mucoid, and inhibitory components cannot be overcome by such a dilution.

U. urealyticum serovar 3 was the serovar most commonly isolated in this study, being present in 18 of 34 patients (53%). This serovar was predominant in other studies, both in female genital specimens and in neonates (2, 4). Multiple serovars were detected in over 50% of patients positive for U. urealyticum, a finding that also has been described previously (2, 4). The PCR primers used in this study, originally described by Teng et al. (18), are able to differentiate between strains of the parvo biovar and strains of the T960 biovar based on slight differences in the amplicon size generated. We found that the primers detected all 14 serovars of U. urealyticum, as has been previously described (18). Of great interest was the excellent correlation between the biovar of the strain(s) isolated in culture and the predicted biovar(s) of U. urealyticum present in the specimen by PCR as demonstrated in Table 2. There were four exceptions, two in which culture detected the presence of two biovars and PCR predicted one, and two in which the opposite was true. Reasons for these disparities may include the fact that the isolates from only one culture from each patient were serotyped, whereas PCR results were available for all specimens. On the other hand, where PCR failed to detect two amplicons, it may have been due to target competition in the reaction. Nonetheless, in over 85% of the specimens, the culture and PCR biovar results from the specimens were concordant, adding further potential utility to this PCR assay as a diagnostic tool.

The use of PCR methodology is increasing in clinical microbiology laboratories, being useful for agents that are costly, slow, and/or difficult to cultivate. U. urealyticum is a good candidate for this technology for all of the above reasons. This study, like others (1, 3, 5, 17), has demonstrated that PCR is at least as sensitive as culture. Based on cost and resources alone, a case may be made for replacing culture with a PCR-based test. One must be cautious, however, with any test which increases sensitivity of detection, as the relevance of the enhanced sensitivity to clinical disease must be considered. Results from our study are encouraging in that many patients, who eventually became positive by culture, could be identified earlier with PCR. PCR diagnosis may be a useful tool to incorporate into the design of antibiotic trials in order to fully assess the benefits and risks of therapy in colonized high-risk neonates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Bayer/Canadian Red Cross Society Research and Development Fund.

We express our thanks to J. Stiskal, K. O’Brien, A. Shennan, E. Kelly, and M. Rabinovitch, for their support of the project and for providing the clinical material used for analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abele-Horn M, Wolff C, Dressel P, Zimmermann A, Vahlensieck W, Pfaff F, Ruckdeschel G. Polymerase chain reaction versus culture for detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in the urogenital tract of adults and the respiratory tract of newborns. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:595–598. doi: 10.1007/BF01709369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arshoff L U, Quinn P A. Proceedings of the 4th International Congress of International Organization for Mycoplasmology, Tokyo, Japan, 1 to 7 September 1982. 1982. Characterization of Ureaplasma urealyticum serotypes in reproductive failure. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanchard, A., J. Hentschel, L. Duffy, K. Baldus, and G. H. Cassell. 1993. Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum by polymerase chain reaction in the urogenital tract of adults, in amniotic fluid, and in the respiratory tract of newborns. Clin. Infect. Dis. 17(Suppl. 1):S148–S153. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Cassell G H, Waites K B, Watson H L, Crouse D T, Harasawa R. Ureaplasma urealyticum intrauterine infection: role in prematurity and disease in newborns. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:69–87. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunliffe N A, Fergusson S, Davidson F, Lyon A, Ross P W. Comparison of culture with the polymerase chain reaction for detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in endotracheal aspirates of preterm infants. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:27–30. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayflick, L. 1965. Tissue cultures and mycoplasmas. Tex. Rep. Biol. Med. 23(Suppl. 1):285–303. [PubMed]

- 7.Kwok S, Higuchi R. Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature. 1989;339:237–238. doi: 10.1038/339237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson S, Matlow A, McDowell C, Roscoe M, Karmali M, Penn L, Dyster L. Detection of Bordetella pertussis in clinical specimens by PCR and a microtiter plate-based DNA hybridization assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:117–120. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.117-120.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn P A. Evidence of an immune response to Ureaplasma urealyticum in perinatal morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986;5:S282–S287. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198611010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn P A. Mycoplasma infection of the fetus and newborn. In: Scarpelli D G, Migaki G, editors. Transplacental effects on fetal health. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss, Inc.; 1988. pp. 107–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinn P A, Butany J, Chipman M, Taylor J, Hannah W. A prospective study of microbial infection in stillbirths and early neonatal death. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:238–249. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson J A, Vekris A, Bebear C, Stemke G W. Polymerase chain reaction using 16S rRNA gene sequences distinguishes the two biovars of Ureaplasma urealyticum. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:824–830. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.824-830.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheurlen W, Frauendienst G, Schrod L, von Stockhausen H-B. Polymerase chain reaction-amplification of urease genes: rapid screening for Ureaplasma urealyticum infection in endotracheal tube aspirates of ventilated newborns. Eur J Pediatr. 1992;151:740–742. doi: 10.1007/BF01959080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepard M C. Culture media for ureaplasmas. Methods Mycoplasmol. 1983;I:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stiskal J, Dunn M, O’Brien K, Shennan A, Kelly E, Longley T, Chappel L, Koppel R, Rabinovitch M. Alpha1-proteinase inhibitor (A1PI) therapy for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in premature infants. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:247A. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor-Robinson D, Furr P M, Liberman M M. The occurrence of genital mycoplasmas in babies with and without respiratory distress. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1984;73:383–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb17752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teng K, Li M, Yu W, Li H, Shen D, Liu D. Comparison of PCR with culture for detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in clinical samples from patients with urogenital infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2232–2234. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2232-2234.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng L J, Zheng X, Glass J I, Watson H, Tsai J, Cassell G H. Ureaplasma urealyticum biovar specificity and diversity are encoded in a multiple-banded antigen gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1464–1469. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.6.1464-1469.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Th’ng C, Quinn P A. Preparation of antisera to the serovars of Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Int J Med Microbiol. 1990;20:795–797. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Th’ng C, Quinn P A. Modified immunoperoxidase assay for direct identification and serotyping of mycoplasma and ureaplasma colonies. Recent advances in mycoplasmology. Int J Med Microbiol. 1990;20:793–795. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waites K B, Bebear C, Robertson J A, Cassell G H. Laboratory diagnosis of mycoplasmal and ureaplasmal infections. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1996;18:105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang E E L, Ohlsson A, Kellner J D. Association of Ureaplasma urealyticum colonization with chronic lung disease of prematurity: results of a meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 1995;127:640–644. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson H, Blalock D K, Cassell G H. Variable antigens of Ureaplasma urealyticum containing both serovar-specific and serovar-cross-reactive epitopes. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3679–3688. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3679-3688.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willoughby J J, Russell W C, Thirkell D, Burdon M G. Isolation and detection of urease genes in Ureaplasma urealyticum. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2463–2469. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2463-2469.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng X, Teng L J, Watson H L, Glass J I, Blanchard A, Cassell G H. Small repeating units within the Ureaplasma urealyticum MB antigen gene encode serovar specificity and are associated with antigen size variation. Infect Immun. 1995;63:891–898. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.891-898.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]