Summary

Acinetobacter baumannii causes a wide range of infections, including wound infections. Multidrug-resistant A. baumannii is a major healthcare concern and the development of novel treatments against these infections is needed. Fosmidomycin is a repurposed antimalarial drug targeting the non-mevalonate pathway, and several derivatives show activity toward A. baumannii. We evaluated the antimicrobial activity of CC366, a fosmidomycin prodrug, against a collection of A. baumannii strains, using various in vitro and in vivo models; emphasis was placed on the evaluation of its anti-biofilm activity. We also developed a 3D-printed wound dressing containing CC366, using melt electrowriting technology. Minimal inhibitory concentrations of CC366 ranged from 1 to 64 μg/mL, and CC366 showed good biofilm inhibitory and moderate biofilm eradicating activity in vitro. CC366 successfully eluted from a 3D-printed dressing, the dressings prevented the formation of A. baumannnii wound biofilms in vitro and reduced A. baumannii infection in an in vivo mouse model.

Subject areas: Microbiology, Microbiofilms

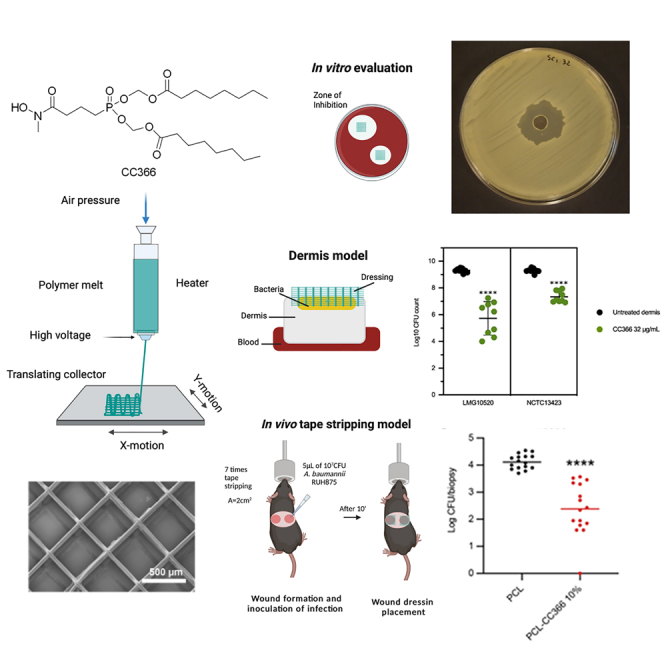

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

CC366 shows antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against Acinetobacter baumannii

-

•

Using 3D-printing, CC366-containing dressings were produced

-

•

CC366-containing dressings prevented biofilm formation in an in vitro wound model

-

•

The dressings reduced A. baumannii infection in an in vivo tape stripping mouse model

Microbiology; Microbiofilms

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii wound infections became notorious during the Iraq War as numerous cases were reported in injured soldiers, earning it the nickname “Iraqibacter”.1,2 These infections have also been reported in community settings and are especially associated with burn wounds.3 A. baumannii is an emerging pathogen that can cause various types of infection and has high levels of antibiotic resistance; for that reason it is included on the list of ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, A. baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.)4 and was listed as a “Critical Priority Pathogen” by the World Health Organization.5 In 2019 A. baumannii infections caused over 250,000 deaths worldwide, making it the fifth bacterial pathogen in terms of mortality.6 A. baumannii infections are often biofilm-related, and biofilm-associated tolerance further complicates treatment of these infections.7,8,9

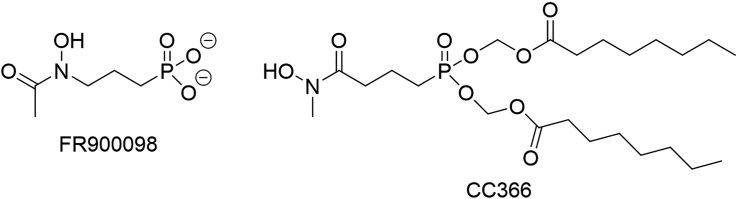

The non-mevalonate pathway is an alternative to the mevalonate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis found in eukaryotes and Dxr (1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase) is the target of the antimalarial compound fosmidomycin.10,11,12 However, fosmidomycin is highly polar (due to the presence of the negatively charged phosphonate moiety), which drastically reduces its cellular uptake by passive diffusion. To circumvent this issue, many prodrugs of fosmidomycin and fosmidomycin derivatives have been synthesized, in which the phosphonate moiety is modified to temporarily shield its charge.13,14,15,16,17,18,19 A. baumannii and several other bacterial pathogens exclusively use the non-mevalonate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis and as such this pathway is an interesting target for the development of novel antibiotics with selective activity against these pathogens.13,20 Indeed, recent work has confirmed that A. baumannii is susceptible to the acetylated fosmidomycin derivative FR90009821 and to FR900098 derivatives with a reversed hydroxamate group and a masked phosphonate moiety,22 from which CC366 was selected for further evaluation in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of FR900098 and CC366

While systemic antibiotic administration is not always effective against wound infections and may lead to an increase in antibiotic resistance,23,24 the incorporation of antimicrobial agents in creams, ointments or wound dressings used for topical treatment is more effective.25 A common antimicrobial compound loaded into these dressings is silver,26 but other classes of antibiotics can also be incorporated.27 However, despite the broad antimicrobial activity of silver, its use in wounds has disadvantages (e.g., a negative effect on wound healing)28 and resistance of wound pathogens (including A. baumannii) against silver and silver-based formulations has been reported.29,30 Because of this, alternative approaches to treat (wound) infections by A. baumannii are needed.

Wound dressings are generally used to stop the bleeding, repair the wound, and prevent infections. Ideally, wound dressings should keep moisture levels balanced, protect from bacterial infections, provide mechanical protection to the wound and allow the exchange of gases and liquid, and be easily removed after use. Different types of dressings have been developed to date, including hydrocolloids, hydrogels, films, foams, alginates, and hydrofibers.31 Unfortunately, none of these types meet all the desired properties described previously. As a result, the selection of the right wound dressings depends mainly on the type of wound, and in complex wounds, very often more than one type of dressing is used. As such, new approaches to develop new wound dressings are urgently needed. Melt electrowriting (MEW) is an additive manufacturing technology to produce fibers in the micrometer and nanometer range, allowing for the printing of a wound dressing. The printing head is equipped with a heating system to melt the material, loaded in the syringe. Air pressure is applied to the syringe to extrude the material out of the nozzle. A high voltage is applied between the nozzle and the collector, leading to charge accumulation in the fluid. When these charges overcome the surface tension, a conical shaped jet (Taylor cone) is formed.32 The most frequently used polymer in MEW is polycaprolactone (PCL). PCL is a semi-crystalline, hydrophobic, biodegradable polyester with a low melting temperature, and low degradation rate. It is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for some clinical applications and use in tissue engineering.33 Recently, MEW has been used to develop PCL-based wound dressings, including PCL wound dressings loaded with silver nanoparticles34 and a hybrid fiber-reinforced PCL scaffold.35

In the present study we developed and evaluated a novel 3D-printed wound dressing containing the fosmidomycin derivative CC366 and evaluated its activity against A. baumannii in various in vitro and in vivo models.

Results and discussion

Antimicrobial activity against planktonic A. baumannii

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ATM, CAZ, MEM, and CC366 was determined for 23 A. baumannii strains (Table 1). Resistance to CAZ (CLSI and EUCAST breakpoint: 32 μg/mL) and MEM (EUCAST breakpoint: 8 μg/mL) was observed in 18 and 16 strains, respectively (there is no EUCAST breakpoint for ATM). For CC366, the MIC was between 1 and 4 μg/mL for 19 strains, 8 μg/mL for two strains, and ≥32 μg/mL for two strains. The MIC of CC366 was >64 μg/mL for both P. aeruginosa PAO1 and S. aureus UAMS-1.

Table 1.

MICs (in μg/mL) of ATM, CAZ, MEM, and CC366 for the 23 A. baumannii strains investigated

| Strain | ATM | CAZ | MEM | CC366 | Strain | ATM | CAZ | MEM | CC366 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB5075 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 2 | G2425 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 4 |

| LMG989 | 32 | 16 | 0.25 | 1 | G2799 | 64 | 32 | 2 | 1 |

| LMG10520 | 16 | 8 | ≤0.125 | 2 | G3065 | 128 | >128 | 64 | 2 |

| LMG10531 | 32 | 8 | ≤0.125 | 2 | N3 | 16 | 128 | 16 | 4 |

| NCTC13423 | 128 | 128 | 4 | 4 | N36 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 8 |

| RUH134 | 32 | 8 | 1 | 1 | N39 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 1 |

| RUH875 | 32 | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | N180 | 128 | >128 | 64 | 2 |

| R67512 | 32 | >128 | >64 | 2 | N183 | 128 | >128 | 64 | 4 |

| G1456 | 128 | >128 | 64 | 8 | N193 | 128 | >128 | 64 | 64 |

| G1882 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 4 | N213 | 64 | >128 | 32 | 2 |

| G2066 | 128 | 128 | >64 | 32 | N233 | 64 | >128 | 16 | 4 |

| G2112 | >128 | >128 | >64 | 4 |

The minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) of CC366 was 4, 16, and 16 μg/mL, for strains LMG10520, NCTC13423, and RUH875, respectively; these MBC values were 2–8-fold higher than the MICs.

The potential synergistic activity of CC366, and ATM or CAZ was also investigated, using A. baumannii LMG10520. With both ATM and CAZ a fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index of 0.75 was obtained, indicating there is no synergy between CC366 and these antibiotics.

Investigation of the molecular basis of differences in susceptibility to CC366

We sequenced and assembled the genomes of two A. baumannii strains with a low CC366 MIC (LMG10520 and NCTC13423) and of two A. baumannii strains with a high CC366 MIC (G2066 and N193) (Table 1). Reduced susceptibility toward fosmidomycin and fosmidomycin derivates can be due to several mechanisms, including mutations in dxr,36 expression of a fosmidomycin resistance gene (fsr) encoding an efflux pump that transports fosmidomycin out of the cell37,38 and reduced uptake through the cAMP-dependent glpT transporter.39,40 Our analysis indicated that dxr sequences were identical in the four strains investigated. Likewise, no differences in fsr sequences could be found. This rules out mutations in dxr or fsr as the reason for the differences in susceptibility toward CC366. None of the four sequenced strains contained a glpT homolog. Additional analysis of 374 A. baumannii genome sequences present in GenBank (using GlpT from E. coli K12 [accession number P08194] as a query, criteria: >50% query coverage, >30% sequence identity) revealed that only a minority (n = 14, 3.7%) had a homolog of this transporter. This indicates that differences in glpT-mediated uptake of fosmidomycin (and its derivatives) are unlikely to be a major cause of reduced susceptibility to fosmidomycin derivatives in A. baumannii. In addition, GlpT is probably only involved in the uptake of derivatives with a free phosphonate group.41

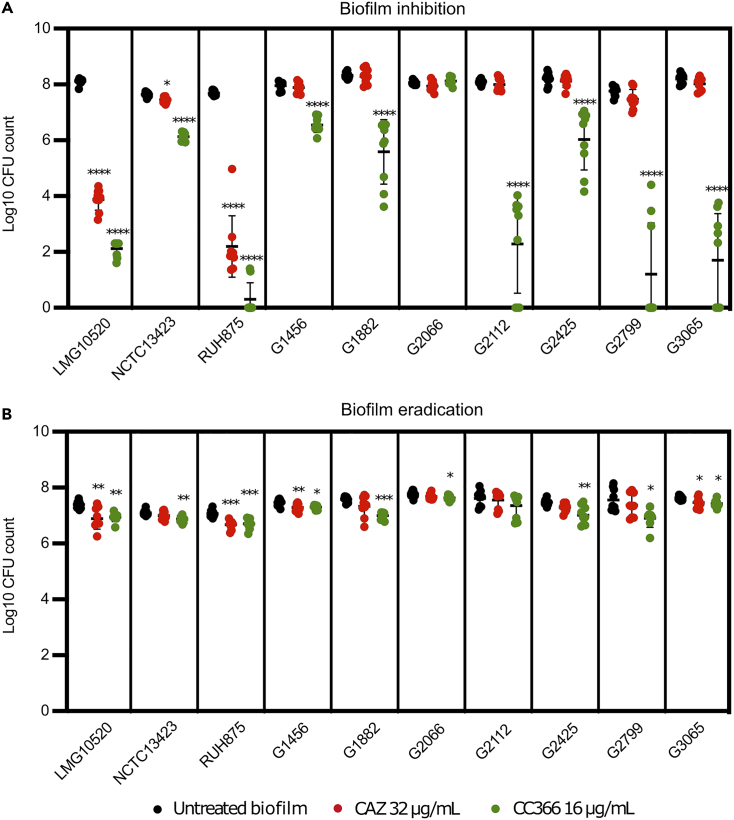

In vitro inhibition and eradication of A. baumannii biofilms by CC366

Both the biofilm inhibition and eradication potential of CC366 (at a concentration of 16 μg/mL) was evaluated on 10 A. baumannii strains (Figure 2); for comparison CAZ (32 μg/mL) was also included in these experiments. Significant biofilm inhibition by CC366 was observed for all strains tested (p < 0.05, 1.4–6.4 log reduction when compared to the untreated biofilm), except for G2066 (the latter strain also had the highest MIC among the strains included in this experiment). Significant biofilm inhibition by CAZ was only observed for strains LMG10520 and RUH875 (p < 0.05, 4.2 and 5.5 log reduction, respectively). Similarly, significant biofilm eradication by CC366 was observed for all strains (p < 0.05, 0.2–0.7 log reduction), except for G2066 and G2112, while CAZ significantly (p < 0.05) reduced the number of colony forming units (CFU) in only 3 of the 10 strains tested.

Figure 2.

Anti-biofilm activity of CC366 (16 μg/mL) and CAZ (32 μg/mL) against 10 A. baumannii strains

(A) Biofilm inhibition.

(B) Biofilm eradication. Bars indicate the mean, dots are individual data points, and error bars represent standard deviation (∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001).

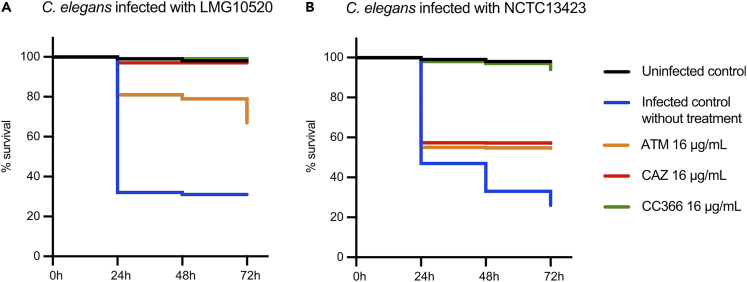

Activity in the C. elegans model

The antimicrobial activity of CC366 was subsequently evaluated in an in vitro C. elegans infection model (Figure 3). Survival of C. elegans was assessed every 24 h for 72 h. In the absence of treatment, a mortality of approximately 70% was observed for nematodes infected with either A. baumannii LMG10520 or NCTC13423. Mortality in infected nematodes (both strains) treated with CC366 (16 μg/mL) was not different from that in the uninfected control (p > 0.05), indicating CC366 can fully rescue C. elegans from A. baumannii-induced mortality. For strain LMG10520, treatment with CAZ (16 μg/mL, i.e., 2 x MIC) reduced mortality to the same level as observed for the uninfected control. In nematodes infected with A. baumannii NCTC13423 and treated with 16 μg/mL CAZ (0.125 x MIC), mortality after 72 h was still 45%, likely due to the high CAZ MIC for this strain. ATM (16 μg/mL, i.e., 1 x MIC for LMG10520 and 0.125 x MIC for NCTC13423) reduced mortality to 30% and 45%, for nematodes infected with strains LMG10520 and NCTC13423, respectively, suggesting ATM maintains activity at sub-MIC level.

Figure 3.

Average survival (n = 139–259 per treatment group) of C. elegans nematodes after infection with A. baumannii

(A) A. baumannii strain LMG10520.(B) A. baumannii strain NCTC13423. Infected nematodes were treated with CAZ (solid red line), ATM (dotted red line), or CC366 (solid green line). No significant difference in mortality (p > 0.05) was observed between uninfected controls (solid black line) and infected nematodes treated with CC366. This was also the case for nematodes infected with A. baumannii LMG10520 and treated with CAZ.

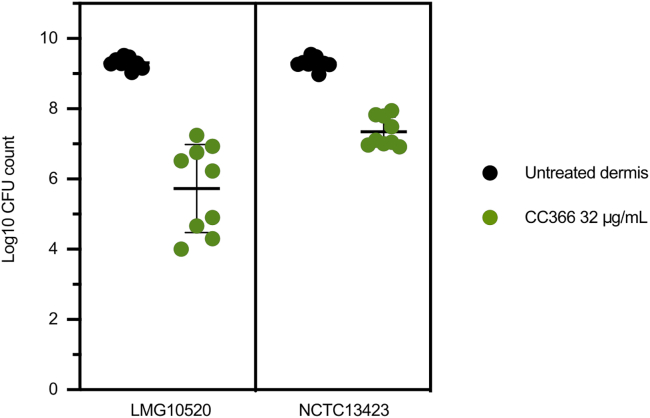

Antimicrobial activity in an in vitro wound model

Subsequently, we evaluated the biofilm inhibitory activity of CC366 in an artificial dermis model. Upon addition of 32 μg/mL of CC366, a 3.5 and 2 log reduction in number of CFU was observed for A. baumannii strains LMG10520 and NCTC13423, respectively (p < 0.0001) (Figure 4). The effect of CC366 in the artificial dermis model indicates that its antimicrobial activity is unlikely to be decreased due to plasma protein binding and is an indication that it could be effective in vivo.

Figure 4.

Activity of CC366 (32 μg/mL) against A. baumannii strains LMG10520 and NCTC13423 in the artificial dermis model

Bars indicate the mean, dots are individual data points, and error bars represent standard deviation (n = 9).

Characterization of 3DP-MEW wound dressings containing CC366

3DP-MEW wound dressings loaded with 5% and 10% CC366 were successfully manufactured and the presence of CC366 in the wound dressings was confirmed by elemental analysis (EDS). The signal of phosphorous (present in CC366, Figure 1) was observed in PCL-CC366 5% and 10% while not in PCL (Table 2).

Table 2.

Elemental analysis of PCL-CC366 5% and PCL-CC366 10%

| P (%atomic) | C (%atomic) | O (%atomic) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCL | No signal | 48.76 ± 2.05 | 51.24 ± 2.05 |

| PCL-CC366 5% | 1.76 ± 0.90 | 43.64 ± 2.16 | 54.59 ± 2.92 |

| PCL-CC366 10% | 2.51 ± 0.79 | 44.76 ± 1.98 | 52.72 ± 2.74 |

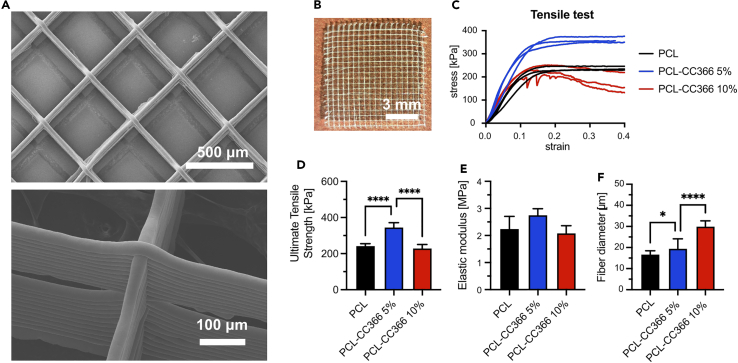

The average thickness of the dressings was 2.51 mm (standard deviation 0.24 mm, n = 6).The fiber diameter of PCL, PCL-CC366 5%, and PCL-CC366 10% wound dressings were analyzed by SEM (Figure 5A). An average fiber diameter of 16.76 μm, 19.54 μm, and 30.01 μm was measured for PCL, PCL-CC366 5%, and PCL-CC366 10%, respectively (Figure 5F). A significant higher fiber diameter was observed in the PCL dressings loaded with CC366 compared to the PCL control. The mechanical properties of the wound dressings were evaluated by a tensile test using dynamic mechanical analysis (Figure 5C). The ultimate tensile strength (Figure 5D) significantly increased for PCL-CC366 5% compared to PCL control, while no differences were observed between PCL-CC366 10% and PCL control. The elastic modulus (Figure 5E) was evaluated in the linear region (1–10% strain), showing no differences between PCL control and PCL-CC366 5% or PCL-CC366 10%.

Figure 5.

Characterization of PCL-CC366 dressings

(A and B) (A) SEM images and (B) picture of a PCL wound dressing of PCL-CC366 5% dressing.

(C) Stress-strain tensile test plot.

(D) Ultimate Tensile Strength (n = 3).

(E and F) (E) Elastic modulus (n = 3) (F) and Fiber diameter (n = 20) of PCL, PCL-CC366 5%, and PCL-CC366 10% 3DP-MEW dressings. Data shown are average, error bars indicate standard deviation.

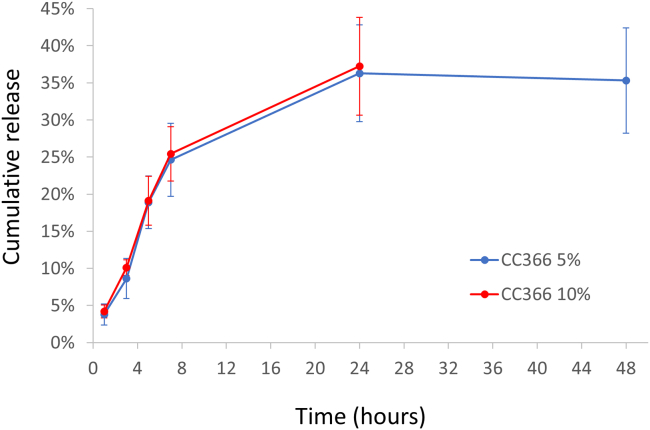

The release of CC366 from the dressings was evaluated by a bioassay. The antimicrobial activity of the eluates at different time points was analyzed. The bulk of the release took place within the first 7 h (24.6% for the PCL-CC366 5% dressing and 25.4% for the PCL-CC366 10% dressing) and an average release of 36.3% and 37.2%, respectively was observed after 24 h. No further release was observed between 24 and 48 h (only investigated for the PCL-CC366 5% dressing) (Figure 6). Not all the CC366 loaded was released, and/or some of the CC366 was degraded and/or lost during printing (e.g., exposure to the printing temperature of 75°C could have caused some degradation of CC366). Nevertheless, the release profile was as desired, as it shows an initial rapid release to facilitate clearing of a bacterial infection and no long-term release of low amounts of CC366 which could potentially increase the risk of resistance development.42,43 Moreover, dressings are normally frequently replaced. Therefore, a new fresh dressing with high drug load would be applied regularly, overcoming the fact that not all CC366 is released.

Figure 6.

Average release of CC366 from PCL-CC366 5%, and PCL-CC366 10% 3DP-MEW dressings, expressed as percentage of the initial amount used for pellet preparation

Error bars indicate standard deviation, n = 3.

In vitro antimicrobial activity of 3DP-MEW CC366 wound dressings

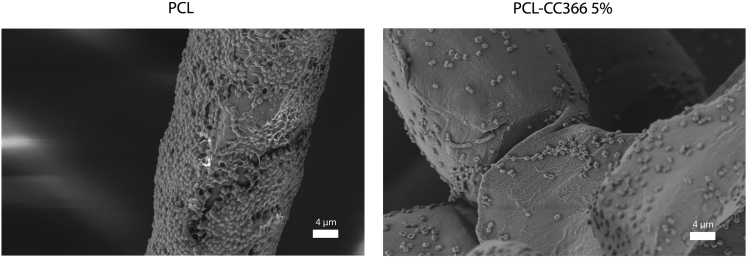

SEM was used to visually confirm the antimicrobial effect of the PCL-CC366 5% dressing in vitro. The results showed a reduction in the number of A. baumannii RUH875 cells attaching to the fibers of the PCL-CC366 5% dressing compared to the non-loaded PCL dressing where a high number of bacterial cells were adhered to the fibers (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Scanning electron microscopy of the non-loaded PCL dressing and PCL-CC366 5% dressing exposed to 1 mL of 107 CFU of A. baumannii RUH875

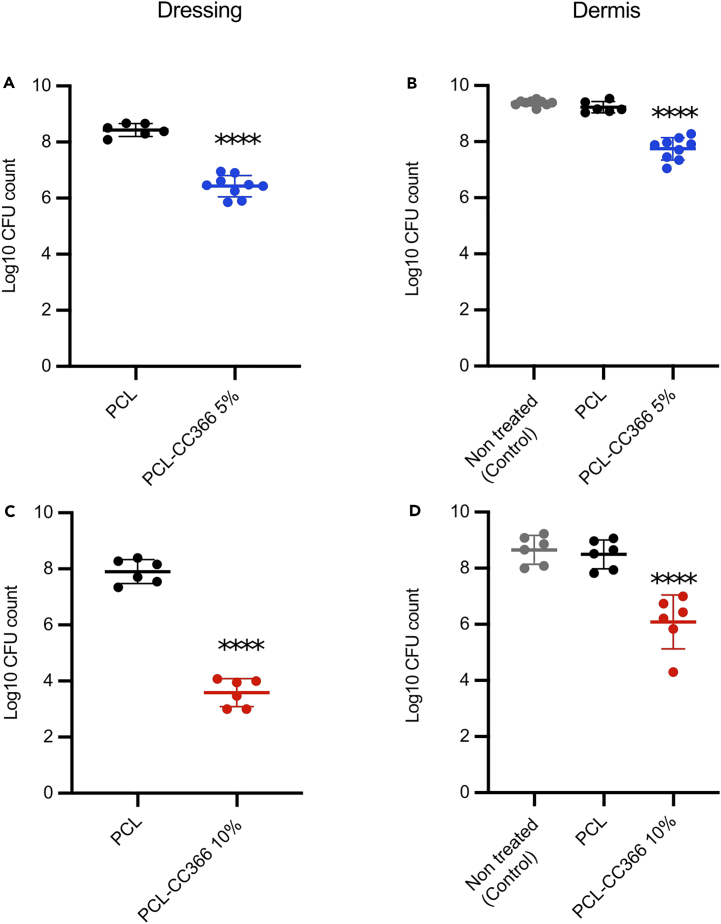

The antimicrobial activity of the 3D-printed wound dressing was subsequently evaluated in the artificial dermis model. CFU counts were obtained both for the dressing (after removing it from the dermis) and for the artificial dermis itself. In line with the SEM results (Figure 7), the PCL-CC366 dressings were less susceptible to microbial colonization than the non-loaded PCL dressing (2 log and >4 log reduction in CFU count for the PCL-CC366 5% and PCL-CC366 10% dressings, respectively) (Figure 8). The number of CFU in the artificial dermis treated with the PCL-CC366 dressings were 1.5 log and 2.5 log lower, for the PCL-CC366 5% and PCL-CC366 10% dressings, respectively, than in the untreated control dermis or the dermis covered with a non-loaded PCL dressing. There was no significant difference between the control dermis and those covered with the non-loaded PCL dressing (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

CFU counts of dressings and artificial dermis after infection with with A. baumannii RUH875

(A) CFU count of PCL-CC366 5% dressings taken of the dermis infected with A. baumannii RUH875.

(B) CFU count of dermis infected with A. baumannii RUH875 after covering with PCL-CC366 5% wound dressings.

(C) CFU count of PCL-CC366 10% dressings taken of the dermis infected with A. baumannii RUH875.

(D) CFU count of dermis infected with A. baumannii RUH875 after covering with PCL-CC366 10% wound dressings. Lines indicate the mean, dots are individual data points, and error bars represent standard deviation (∗∗∗∗ p < 0.001).

Cytotoxicity testing

There was no difference between morphology of the 3T3 fibroblasts cultured with and without the tested dressings, even in the proximity of the dressings (Figure S1). The viability of the 3T3 fibroblasts determined quantitatively by means of the MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) assay was on average 96% (standard deviation ±6%), 80% (±2%), and 90% (±6%) of the control for PCL, PCL+5%, and PCL+10%, respectively (Figure S3). As the threshold for cytotoxicity is 70% (according to the ISO 10993-5 standard), this indicates the samples are not cytotoxic. Moreover, the reduced viability observed could be a result of cell detachment caused by the presence of samples (circular areas without cells were visibly macroscopically after removal of the samples before the MTS assay), causing a slight overestimation of toxicity.

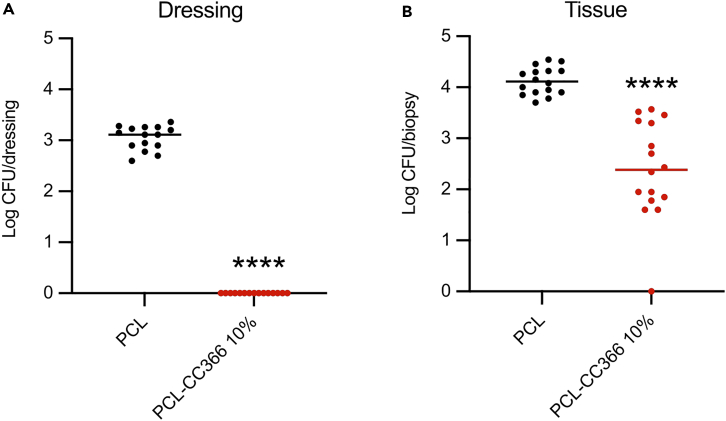

Antimicrobial efficacy of a CC366 releasing dressing against A. baumannii in a mouse infection model

The antimicrobial efficacy of the PCL-CC366 10% dressing was assessed using an in vivo tape stripping mouse model (as the effect of the 5% dressing in the in vitro experiment was markedly lower than that of the 10% dressing, we decided to only include the latter). The skin was inoculated with 107 CFU of A. baumannii RUH875 and treated for 4 h with the presoaked non-loaded PCL dressing or PCL-CC366 10%. The skin treated with the PCL-CC366 10% contained 2.39 ± 0.96 log CFU/biopsy, while skin treated with the unloaded PCL dressing contained 4.13 ± 0.26 log CFU/biopsy (Figure 9). When the number of CFU recovered from the dressings were compared after the experiment, no bacteria were recovered from the PCL-CC366 10% dressing while 3.05 ± 0.23 log CFU/dressing were recovered from the unloaded PCL dressings (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Number of CFU of A. baumannii RUH875 recovered from dressings and tissue biopsies (in vivo tape stripping mouse model)

(A) Non-loaded PCL and PCL-CC366 10% dressings. (B) Tissue biopsies. Lines indicate the mean, dots are individual data points, and error bars represent standard deviation (∗∗∗∗ p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

The fosmidomycin derivative CC366 has good activity against planktonic cells of the majority of A. baumannii biofilms investigated, can inhibit A. baumannii biofilms in both a 96-well plate and an in vitro wound model, remains (at least partially) active throughout the 3D-printing process and can successfully elute from 3D-printed wound dressing. This results in a wound dressing capable of resisting A. baumannii biofilm formation and is able to reduce the number of A. baumannii bacteria in both the artificial dermis as well as the in vivo tape stripping mouse model.

Limitations of the study

While we have shown antimicrobial activity of CC366 against a large collection of A. baumannii isolates in a range of (physiologically relevant) models, including an in vivo model, these models do not allow us to address the effect of CC366 on wound healing. Although it would seem reasonable to assume that the drastic reduction in CFU counts would translate into improved wound healing, this remains to be determined.

We studied the release of CC366 from the dressings using a bioassay, after the wound dressings were placed in 1 mL of receiver phase (PBS buffer). This approach measures drug release from all faces of the wound dressing and hence may overestimate the in vivo release. In addition, it is at present unclear whether the volume of receiver phase used is sufficient to fully mimic what happens in vivo. Future studies using more advanced approaches (e.g., based on diffusion cells) can help shed light on this. In addition, the amount of CC366 released was quantified using a bioassay. While microbiological assays are frequently used to quantify antimicrobial compounds (including colistin, gentamicin, rifampicin, and vancomycin),44 other analytical approaches (e.g., based on HPLC) may yield a more accurate picture of the release of CC366 from the dressings used in the present study.

In the present study we focused on monospecies biofilms formed by various A. baumannii strains, while many biofilm-related infections are polymicrobial.45,46,47 In addition, several studies have shown that interactions between microorganisms in these polymicrobial biofilms can affect antimicrobial tolerance,48,49,50,51 which suggests that further investigating the activity of CC366 in polymicrobial biofilms would yield additional insights into its clinical applicability. It should nevertheless be noted that there is growing awareness of the role of spatial organization in determining antimicrobial susceptibility in polymicrobial communities, and especially in chronically infected wounds there seems to be spatial segregation between different organisms.52,53,54 While the latter has to our knowledge not yet been investigated for A. baumannii biofilms, it suggests that it is important to study antimicrobial tolerance in polymicrobial communities in the relevant in vivo models, which is outside the scope of the present study.

Finally, at this point our analyses do not allow to identify the molecular basis of the observed differences in susceptibility toward CC366 in different A. baumannii strains. A possible explanation is that differences in expression of fsr (as previously observed in Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria)38 are involved, but this remains to be confirmed. Further investigations of the (potential) development of resistance during experimental evolution in biofilms and whole genome sequencing as well as phenotypic characterization of the resulting resistant mutants could help shed light on the molecular basis of differences in susceptibility toward CC366.55

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Acinetobacter baumannii AB5075 | C. Van der Henst (Free University of Brussels, Belgium) | AB5075 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii LMG989 | BCCM/LMG Bacteria Collection (Belgium) | LMG989 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii LMG10520 | BCCM/LMG Bacteria Collection (Belgium) | LMG10520 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii LMG10531 | BCCM/LMG Bacteria Collection (Belgium) | LMG10531 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii NCTC13423 | National Collection of Type Cultures (UK) | NCTC13423 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii RUH134 | Y. Briers (Ghent University) | RUH134 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii RUH875 | P. Nibbering (Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands) | RUH875 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii R67512 | H. Goossens (Antwerp University Hospital, Belgium) | R67512 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii G1456 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | G1456 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii G1882 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | G1882 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii G2066 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | G2066 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii G2112 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | G2112 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii G2425 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | G2425 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii G2799 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | G2799 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii G3065 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | G3065 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii N3 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | N3 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii N39 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | N39 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii N180 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | N180 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii N183 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | N183 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii N193 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | N193 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii N213 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | N213 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii N233 | B. Verhasselt (Ghent University Hospital, Belgium) | N233 |

| Escherichia coli OP50 | Own collection | OP50 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | Own collection | PAO1 |

| Staphylococcus aureus UAMS-1 | American Type Culture Collection (US) | ATCC49230 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Mueller-Hinton Broth | Lab M | Cat# LAB114 |

| Mueller-Hinton Agar | Lab M | Cat# LAB039 |

| Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM) high glucose | Gibco | Cat# 11965092 |

| Aztreonam | TCI Europe | Cat# A2466 |

| Ceftazidime | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C3809 |

| Meropenem | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# PHR1772 |

| Polycaprolactone | Corbion | Cat# PC12 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA library prep kit | New England Biolabs | Cat# E7645S |

| CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay | Promega | Cat# G3582 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Whole genome sequencing data | This paper | Array Express: E-MTAB-12357 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Caenorhabditis elegans N2 | Own collection | N2 |

| C75Bl/6J OlaHsd specific pathogen-free mice | Envigo (The Netherlands) | |

| 3T3 fibroblast cells | ATCC | |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 9 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| SPSS 25 | SPSS Inc | https://www.ibm.com/spss |

| BioCAD | REGENHU | https://www.regenhu.com/ |

| CLC Genomics Workbench | Qiagen | http://www.qiagen.com |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Tom Coenye (tom.coenye@ugent.be).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Culturing of A. baumannii strains, P. aeruginosa PAO1, and S. aureus UAMS-1 was done in Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth (Lab M Limited, UK) or on MH agar plates (Lab M Limited) under aerobic conditions at 37°C. The A. baumannii strains used are reference isolates LMG989, LMG10520 (wound isolate),56 LMG10531 (wound isolate),57 NCTC13423 (wound isolate),58 RUH134 and RUH875 (both isolated from urine),59 AB5075 (isolated from a patient suffering from osteomyelitis),60 and a series of recent clinical isolates recovered in Belgium (R67512, G1456, G1882, G2066, G2112, G2425, G2799, G3065, N3, N36, N39, N180, N183, N193, N213, and N233).

Caenorhabditis elegans infection

Experiments with C. elegans N2 were carried out using nematode growth medium (NGM) plates containing 3 g/L NaCl (Chem-Lab, Belgium), 17 g/L agar (Neogen, Belgium), 2.5 g/L peptone (Oxoid, UK), 1 mM CaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 5 μg/ml cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM MgSO4, and 25 mM KPO4 buffer (KH2PO4, K2HPO4, pH 6.0) (Sigma-Aldrich).61 A liquid growth medium (OGM) was used consisting of 95% (v/v) M9 buffer (3 g/L KH2PO4, 6 g/L Na2HPO4, 0.5 g/L NaCl, 1 g/L NH4Cl, 1 mM MgSO4) (Sigma-Aldrich), 5% (v/v) Brain heart infusion (Lab M Limited), and 10 μg/mL cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich). C. elegans eggs were harvested from adult nematodes by first washing nematodes from NGM plates with PS followed by washing with PS 3 times and finally resuspending in 14 mL of PS. Subsequently 3.5 mL of nematode suspension was combined with 0.5 mL 4 M NaOH (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mL 5% bleach (Sigma-Aldrich), vortexed for 10 seconds, every 2 minutes, for 10 minutes and then centrifuged for 30 seconds at 1300 x g (5804 R, Eppendorf, Germany). The supernatant was then removed, and the eggs were washed 5 times with PS before resuspending them in 0.25 mL PS and spreading on fresh NGM plates containing a 6 hours old lawn of Escherichia coli OP50 as a food source. Plates with eggs were incubated for 4 days at 25°C; nematodes were subsequently washed of the plates with PS, washed 3 times with OGM, and resuspended in OGM. 25 μL of the nematode suspension (containing approximately 25 nematodes) were then combined with 25 μL (5 × 107 CFU) of an overnight A. baumannii culture (LMG10520 or NCTC13423) and 25 μL of CC366, ATM, or CAZ (final concentration 16 μg/mL) in the well of a 96-well microtiter plate. The final volume was adjusted to 100 μL using OGM. Plates were kept at 25°C for the duration of the experiment. Nematode survival was determined by counting dead (non-motile) and living (motile) nematodes under a microscope (Life Technologies EVOS FL Auto, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) after putting the plate on a plate shaker (Titramax 1000; 5 minutes at 600 rpm) to induce moving.

In vitro wound model

The artificial dermis was prepared as previously described,62 and subsequently placed in a flat-bottomed 24-well microtiter plate (Greiner Bio-One). The medium used was composed of Bolton Broth (Oxoid) with 33% bovine plasma (Sigma-Aldrich), 3% freeze−thaw laked horse blood, and 0.5 U/mL heparin (Calbiochem, USA). Five hundred microliters of medium and 10 μL of an overnight culture of A. baumannii (containing approximately 104 CFU) was pipetted on top of the artificial dermis, and 100 μL of a CC366 solution was added (final concentration: 32 μg/mL). The final volume in the well was adjusted to 1 mL by adding medium around the artificial dermis. Experiments with the wound dressings were carried out as described above, but instead of adding CC366 solution, the dressing was placed on top of the artificial dermis. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 24 hours after which the wound dressing was taken off and washed with 1 mL of PS if applicable. The artificial dermis was collected in a tube containing 10 mL of PS and biofilms were disrupted by three series of 30 seconds vortexing and 30 seconds sonication at 42 kHz (Branson 3510). The number of CFU was determined by plating on MH plates.

In vivo wound model

The mouse study was approved (20-10066-1-02; 22 December 2021) by the animal ethical committee of the Amsterdam UMC (The Netherlands) and carried out according to the guidelines of the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments. Specific pathogen-free C57Bl/6J OlaHsd immune-competent female mice (Envigo, The Netherlands), aged 8 to 10 weeks, were used. The backs of mice were shaved using an electric razor right before the experiment. Thirty minutes before the experiment, mice were subcutaneously injected with the analgesic buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg; Temgesic, RB Pharmaceutical Limited, UK). Then, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Pharmachemie, The Netherlands) in O2. Mice were kept under anesthesia and at an optimal body temperature with a temperature-controlled heat mat during the entire experiment. At the middle region of the back of the mice, an area of about 2 cm2 was tape-stripped with Tensoplast (BSN Medical, The Netherlands) seven times, with the tape being replaced after the first time, resulting in a visibly damaged skin. Five microliters of a mid-logarithmic growth-phase culture, containing 107 CFU of A. baumannii RUH875, were applied in duplo on the the damaged skin of the back of the animals.63,64,65 Fifteen minutes after inoculation, two non-loaded PCL dressings (control group) or two PCL-CC366 10% dressings presoaked with 100 μL of saline were placed on each inoculated wound site. After a treatment period of 4 hours, the skin was separated from the underlying fascia and muscle tissue, and about 2 cm2 of skin from the infected area was excised. The skin was homogenized in 0.5 mL of PBS using five 2mm zirconia beads (BioSpec Products, USA) and the MagNA Lyser System (Roche, Switzerland), with three cycles of 30 seconds at 7000 rpm, with 30 seconds of cooling on ice between cycles. The number of viable bacteria was determined. The lower limit of detection was 10 CFU.

Method details

Determination of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC)

MICs were determined in flat bottom 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Austria) using MH medium at 37°C under aerobic conditions according to the EUCAST guidelines for broth microdilution.66 Optical density at 590 nm was determined using an Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer, USA). Control antibiotics used were aztreonam (ATM), ceftazidime (CAZ) and meropenem (MEM). MBCs were determined by plating the content of wells containing the antimicrobial agent in a concentration equal to and higher than the MIC.

Antimicrobial synergy testing

Synergy between CC366 (concentration range tested: 0.03125–2 μg/mL) and ATM (0.5–32 μg/mL) or CAZ (0.5–32 μg/mL) was determined using checkerboard assays in flat bottom 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One), using A. baumannii LMG10520 (final inoculum 5 x 105 colony forming units [CFU] in 100 μL MH). The plate was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C under aerobic conditions. Optical density at 590 nm was determined using an Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer) and the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index was calculated as described before.67

Evaluation of biofilm inhibitory and eradicating activity

Biofilm experiments were performed in round bottom 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One). For biofilm inhibition, an overnight A. baumannii culture (final inoculum 105 CFU) was combined with CC366 (final concentration: 16 μg/mL) or CAZ (final concentration: 32 μg/mL) in a total volume of 100 μL MH medium and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. For biofilm eradication, 100 μL of an overnight A. baumannii culture (final inoculum 105 CFU, in MH) was added to the well of a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. After incubation the medium was removed, the biofilm was rinsed with 100 μL 0.9% (w/v) NaCl (physiological saline, PS), and 100 μL of CC366 (final concentration: 16 μg/mL) or CAZ (final concentration: 32 μg/mL) (dissolved in PS) was added. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for an additional 24 hours. For biofilm quantification, the supernatant was removed, 100 μL PS was added and biofilms were dislodged by shaking at 900 rpm for 5 minutes (Titramax 1000, Heidolph, Germany) followed by sonication at 42 kHz for 5 minutes (Branson 3510, Marshall Scientific, USA). The supernatant was collected, another 100 μL of PS were added, and the procedure described above was repeated. Finally, the number of CFU in the resulting 200 μL PS was determined by plating on MH plates.

Whole genome sequencing and analysis of A. baumannii genome sequences

We determined the whole genome sequence of A. baumannii strains LMG10520, NCTC13423, G2066 and N193. DNA was extracted as described before.68 DNA concentration was measured with PicoGreen dsDNA quantitation reagent (Thermofisher Scientific, USA), DNA was then fragmented to 400 bp using a S2 ultrasonicator (Covaris, USA). Libraries were prepared with the NEBNext Ultra II kit with size selection using ampure XP beads after adapter ligation. Quality of libraries was checked on a Bioanalyzer with a DNA High Sensitivity Chip (Agilent, USA). Libraries were normalized manually and sequenced on a Hiseq3000 Illumina platform, yielding > 1.6 Gb per sample. The resulting 150 bp paired reads were analyzed with the CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen, Denmark). Reads were assembled into contigs using the following parameters: word size = 40, mismatch cost = 2, insertion and deletion costs = 3, average coverage > 50, consensus length > 1000. Raw data are available from ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-12357. Contigs were automatically annotated using RAST69 and the RASTtk annotation scheme.70 Sequences corresponding to dxr and fsr were extracted from each genome and aligned using the CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen).

CC366-PCL ink preparation

CC366-PCL pellets were obtained by a solvent casting process. First, PCL PC12 (Corbion, The Netherlands) and CC366 were dissolved in chloroform (Stanlab, Poland), at 10% (w/v) and 5% or 10% (w/w) respectively. The solution was poured on a petri dish and left overnight for solvent evaporation. The obtained film was then transferred into a low-pressure dryer (50 mbar) for 5 days. The film was then cut in small pellets and stored at −20°C for further use.

Fabrication of 3DP-MEW wound dressings containing CC366

CAD (Computer-aided Design) models were designed using a Biomedical Research software BioCAD (REGENHU, Switzerland). The design model was a square shape 20 × 20 mm, distance between fibers of 0.5 mm, angle between layers of 0–90 degrees, and 100 layers. 3DP-MEW wound dressings were manufactured using a 3D Discovery bioprinter (REGENHU) with a MEW printing head. A glass slide (8 × 5 × 1 cm) was used on top of the ceramic collector as a substrate to collect the fibers. The printing parameters were printing-head temperature 70°C (PCL-CC366 5%–10%) and 75°C (PCL), pressure 0.12 MPa, speed of collector 6 mm/s (PCL) and 11 mm/s (PCL-CC366 5%–10%), and offset height “z” 3 (PCL-CC366 5%–10%) and 5 mm (PCL). A gradient applied voltage of 5 to 6.5 kV was applied to maintain a constant electric field.71

Characterization of 3DP-MEW wound dressings containing CC366

The mechanical properties of PCL, PCL-CC366 5%, and PCL-CC366 10% wound dressings were evaluated using dynamic mechanical analysis (Dynamic Mechanical Analysis Q800, TA Instruments, USA). Samples were cut at 20 mm length and 10 mm width using a scalpel. The elastic modulus was determined in the linear region of stress-strain of tensile tests (5–20% strain region). The fiber diameter of PCL, PCL-CC366 5%, and PCL-CC366 10% wound dressings was analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (SU8000, Hitachi, Japan). A semi-quantitative elemental analysis (EDS, Phenom ProX Desktop SEM, Thermofisher Scientific, USA) was used to confirm the presence of CC366 in the PCL-CC366 5% and PCL-CC366 10% wound dressings.

Quantification of CC366 release from the dressings

CC366 release from dressings was quantified using a bioassay. The wound dressings (1 × 1 cm) were placed in 1 mL PBS in an Eppendorf tube at 37°C. The 10% dressings had a mass of 3.2–3.6 mg and the the 5% dressings had a mass of 1.9–5.0 mg. After 1, 3, 5, 7, and 24 hours, 100 μL was collected and replaced with 100 μL fresh PBS. The collected eluate was added to a hole (7.5 mm diameter) in the center of a 25 mL MH agar plate containing a lawn of A. baumannii LMG10520. The plate was incubated for 24 hours and the diameter of the zone of inhibition was measured. The diameter of inhibition zones were used to determine the concentration of CC366 present in the eluates, based on a standard curve set up with solutions with varying concentrations of CC366 (Figure S3).

Visualization of bacterial adhesion to the dressings using SEM

The attachment to and biofilm formation on the dressings was studied using A. baumannii RUH875. Non-loaded PCL dressings or PCL-CC366 5% dressings were used in this assay. A mid-logarithmic culture of A. baumannii RUH875 was used to prepare an inoculum of 107 CFU/mL. The dressings were placed in a 1 mL bacterial suspension for 24 hours at 37°C and 120 rpm. Subsequently, the dressings were washed twice with demineralized water and fixed in a solution of 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde (Merck, USA) with 1% (v/v) glutaraldehyde (Merck) overnight at room temperature. The dressings were rinsed twice with demineralized water for 10 minutes and dehydrated in a graded ethanol concentration series (50%–100% of ethanol). The dressings were immersed in hexamethyldisilane (Polysciences Inc., USA) overnight. Before imaging, samples were mounted on aluminum SEM stubs and sputter-coated with a 4 nm platinum–palladium layer using a Leica EM ACE600 sputter coater (Microsystems, Germany). Images were acquired at 3 kV using a Zeiss Sigma 300 SEM (Zeiss, Germany) at the Electron Microscopy Center Amsterdam (ECMA; Amsterdam UMC, The Netherlands). For each dressing, 4 fields were inspected and photographed at magnifications of 50× and 2000×.

Cytotoxicity testing

The pristine PCL, PCL-CC366 5%, and PCL-CC366 10% dressings were evaluated for the release of cytotoxic compounds by means of the direct-contact test (ISO 10993-5). 3T3 fibroblast (ATCC) were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 105 per well in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM high glucose; Gibco, UK) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; EuroClone, Italy), 100 U/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma, USA). On the next day, the dressings (diameter of 10 mm, which corresponded to 9% of the growth surface area of a well in a 6-well plate) were sterilized with UV light (30 min for each side), placed in tubes containing 3 ml of cell culture medium; the PCL mats had to be centrifuged 3 min in order to remove air bubbles. Immediately after centrifugation, the mats were gently placed on subconfluent cell layer, and titanium rings were placed on top of the specimens to prevent them from floating. Cells cultured without dressings were used as controls. Cytotoxicity of the materials was evaluated after 24 h of incubation both qualitatively (cell morphology, light microscope) and quantitatively (cell viability, MTS assay). Following the microscopic observations, the specimens and rings were removed from the wells, and the cell layer was washed with DMEM. Subsequently, 2 ml of DMEM and 400 μl of MTS reagent (CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega, USA) were added to each well and incubated in the cell culture incubator for 60 min. After that time the reactions was stopped and 100 μl of supernatant was transferred in quadruplicate into 96-well plate. The absorbance was measured at λ = 490 nm using microplate reader (Fluostar Omega, BMGLabtech, Germany).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Verification of the normal distribution of the data was done using the Shapiro−Wilk test. The log 10 transformed values for CFU counts between two groups were compared by an independent sample t-test. For comparison of multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. The C. elegans survival data were analyzed using the log rank test for Kaplan-Meier curves. For the mouse study, two-sample comparisons were made using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney rank sum test. All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., USA) or GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, USA).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the EU within the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020—Marie Skłodowska-Curie Innovative Training Networks (grant agreements No. 722467 and 860816; research projects PRINT-AID and MepAnti, respectively) and EU H2020-WIDESPREAD-05-2020—Twinning grant CEMBO (number 952398). Additional funding was obtained from the Special Research Fund of Ghent University (grants BOF20-GOA002 and BOFITN-2020). C.C. thanks the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO) for a PhD-scholarship (1121315N).

We thank H. Goossens, Y. Briers, B. Verhasselt, and C. Van der Henst for providing strains. We would like to thank the animal caretakers of the Animal Research Institute (ARIA, Amsterdam UMC, The Netherlands) for their excellent support during the animal experiments and Nicole van der Wel (Electron Microscopy Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, The Netherlands) for her technical assistance with SEM. We thank the Oxford Genomics Center at the Wellcome Center for Human Genetics (funded by Wellcome Trust grant ref. 203141/Z/16/Z) for the generation and initial processing of the whole genome sequencing data.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, T.C., S.A.J.Z., M.R., and W.S.; Methodology, F.v.C., D.M.P., and C.G.P.; Formal Analysis, T.C., F.v.C., D.M.P., C.G.P., and M.R.; Investigation, F.v.C., D.M.P., C.G.P., C.C., J.S., A.S., E.C., and M.R.; Writing – Original Draft, F.v.C, D.M.P, C.G.P, and T.C.; Writing – Review and Editing, all authors; Supervision: T.C., S.V.C., M.R., S.A.Z.J., and W.S.; Project Administration, T.C., M.R., S.A.Z.J., and W.S.; Funding Acquisition, T.C., S.A.Z.J., and W.S.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: August 7, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.107557.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

Raw whole genome sequencing data are available from ArrayExpress. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Sebeny P.J., Riddle M.S., Petersen K. Acinetobacter baumannii skin and soft-tissue infection associated with war trauma. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;47:444–449. doi: 10.1086/590568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard A., O'Donoghue M., Feeney A., Sleator R.D. Acinetobacter baumannii: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Virulence. 2012;3:243–250. doi: 10.4161/viru.19700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerrero D.M., Perez F., Conger N.G., Solomkin J.S., Adams M.D., Rather P.N., Bonomo R.A. Acinetobacter baumannii-associated skin and soft tissue infections: recognizing a broadening spectrum of disease. Surg. Infect. 2010;11:49–57. doi: 10.1089/sur.2009.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee C.R., Lee J.H., Park M., Park K.S., Bae I.K., Kim Y.B., Cha C.J., Jeong B.C., Lee S.H. Biology of Acinetobacter baumannii: Pathogenesis, Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms, and Prospective Treatment Options. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017;7:55. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tacconelli E., Carrara E., Savoldi A., Harbarth S., Mendelson M., Monnet D.L., Pulcini C., Kahlmeter G., Kluytmans J., Carmeli Y., et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet (London, England) 2022;399:629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dallo S.F., Weitao T. Insights into acinetobacter war-wound infections, biofilms, and control. Adv. Skin Wound Care. 2010;23:169–174. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000363527.08501.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Acker H., Van Dijck P., Coenye T. Molecular mechanisms of antimicrobial tolerance and resistance in bacterial and fungal biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciofu O., Moser C., Jensen P.Ø., Høiby N. Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022;20:621–635. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00682-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lichtenthaler H.K. Non-mevalonate isoprenoid biosynthesis: enzymes, genes and inhibitors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2000;28:785–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiesner J., Borrmann S., Jomaa H. Fosmidomycin for the treatment of malaria. Parasitol. Res. 2003;90(Suppl 2):S71–S76. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jomaa H., Wiesner J., Sanderbrand S., Altincicek B., Weidemeyer C., Hintz M., Türbachova I., Eberl M., Zeidler J., Lichtenthaler H.K., et al. Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1999;285:1573–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uh E., Jackson E.R., San Jose G., Maddox M., Lee R.E., Lee R.E., Boshoff H.I., Dowd C.S. Antibacterial and antitubercular activity of fosmidomycin, FR900098, and their lipophilic analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:6973–6976. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brücher K., Gräwert T., Konzuch S., Held J., Lienau C., Behrendt C., Illarionov B., Maes L., Bacher A., Wittlin S., et al. Prodrugs of reverse fosmidomycin analogues. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:2025–2035. doi: 10.1021/jm5019719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ponaire S., Zinglé C., Tritsch D., Grosdemange-Billiard C., Rohmer M. Growth inhibition of Mycobacterium smegmatis by prodrugs of deoxyxylulose phosphate reducto-isomerase inhibitors, promising anti-mycobacterial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;51:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiesner J., Ortmann R., Jomaa H., Schlitzer M. Double ester prodrugs of FR900098 display enhanced in-vitro antimalarial activity. Arch. Pharm. 2007;340:667–669. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200700069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courtens C., Risseeuw M., Caljon G., Cos P., Van Calenbergh S. Acyloxybenzyl and Alkoxyalkyl Prodrugs of a Fosmidomycin Surrogate as Antimalarial and Antitubercular Agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;9:986–989. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courtens C., Risseeuw M., Caljon G., Maes L., Martin A., Van Calenbergh S. Amino acid based prodrugs of a fosmidomycin surrogate as antimalarial and antitubercular agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019;27:729–747. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards R.L., Heueck I., Lee S.G., Shah I.T., Miller J.J., Jezewski A.J., Mikati M.O., Wang X., Brothers R.C., Heidel K.M., et al. Potent, specific MEPicides for treatment of zoonotic staphylococci. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sass A., Everaert A., Van Acker H., Van den Driessche F., Coenye T. Targeting the Nonmevalonate Pathway in Burkholderia cenocepacia Increases Susceptibility to Certain beta-Lactam Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018;62 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02607-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ball H.S., Girma M.B., Zainab M., Soojhawon I., Couch R.D., Noble S.M. Characterization and Inhibition of 1-Deoxy-d-Xylulose 5-Phosphate Reductoisomerase: A Promising Drug Target in Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021;7:2987–2998. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courtens C., van Charante F., Quennesson T., Risseeuw M., Cos P., Caljon G., Coenye T., Van Calenbergh S. Acyloxymethyl and alkoxycarbonyloxymethyl prodrugs of a fosmidomycin surrogate as antimalarial and antibacterial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023;245 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeitlinger M.A., Sauermann R., Traunmüller F., Georgopoulos A., Müller M., Joukhadar C. Impact of plasma protein binding on antimicrobial activity using time-killing curves. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;54:876–880. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falcone M., De Angelis B., Pea F., Scalise A., Stefani S., Tasinato R., Zanetti O., Dalla Paola L. Challenges in the management of chronic wound infections. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021;26:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Percival S.L., Bowler P., Woods E.J. Assessing the effect of an antimicrobial wound dressing on biofilms. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leaper D.J. Silver dressings: their role in wound management. Int. Wound J. 2006;3:282–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2006.00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simões D., Miguel S.P., Ribeiro M.P., Coutinho P., Mendonça A.G., Correia I.J. Recent advances on antimicrobial wound dressing: A review. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018;127:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khansa I., Schoenbrunner A.R., Kraft C.T., Janis J.E. Silver in Wound Care-Friend or Foe?: A Comprehensive Review. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2019;7 doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosny A.E.D.M., Rasmy S.A., Aboul-Magd D.S., Kashef M.T., El-Bazza Z.E. The increasing threat of silver-resistance in clinical isolates from wounds and burns. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019;12:1985–2001. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S209881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeilly O., Mann R., Hamidian M., Gunawan C. Emerging Concern for Silver Nanoparticle Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii and Other Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.652863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabriela F.V., Leon-Mancilla B., Esquivel-Solis H. Advances in the Management of Skin Wounds with Synthetic Dressings. Clin. Med. Rev. Case Rep. 2016;3 doi: 10.23937/2378-3656/1410131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalton P.D. Melt electrowriting with additive manufacturing principles. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2017;2:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cobme.2017.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hewitt E., Mros S., McConnell M., Cabral J.D., Ali A. Melt-electrowriting with novel milk protein/PCL biomaterials for skin regeneration. Biomed. Mater. 2019;14 doi: 10.1088/1748-605X/ab3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du L., Yang L., Xu B., Nie L., Lu H., Wu J., Xu H., Lou Y. Melt electrowritten poly(caprolactone) lattices incorporated with silver nanoparticles for directional water transport antibacterial wound dressings. New J. Chem. 2022;46:13565–13574. doi: 10.1039/d2nj01612e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afghah F., Iyison N.B., Nadernezhad A., Midi A., Sen O., Saner Okan B., Culha M., Koc B. 3D Fiber Reinforced Hydrogel Scaffolds by Melt Electrowriting and Gel Casting as a Hybrid Design for Wound Healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022;11 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202102068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armstrong C.M., Meyers D.J., Imlay L.S., Freel Meyers C., Odom A.R. Resistance to the antimicrobial agent fosmidomycin and an FR900098 prodrug through mutations in the deoxyxylulose phosphate reductoisomerase gene (dxr) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:5511–5519. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00602-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujisaki S., Ohnuma S., Horiuchi T., Takahashi I., Tsukui S., Nishimura Y., Nishino T., Kitabatake M., Inokuchi H. Cloning of a gene from Escherichia coli that confers resistance to fosmidomycin as a consequence of amplification. Gene. 1996;175:83–87. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messiaen A.S., Verbrugghen T., Declerck C., Ortmann R., Schlitzer M., Nelis H., Van Calenbergh S., Coenye T. Resistance of the Burkholderia cepacia complex to fosmidomycin and fosmidomycin derivatives. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2011;38:261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hemmerlin A., Tritsch D., Hammann P., Rohmer M., Bach T.J. Profiling of defense responses in Escherichia coli treated with fosmidomycin. Biochimie. 2014;99:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castañeda-García A., Rodríguez-Rojas A., Guelfo J.R., Blázquez J. The glycerol-3-phosphate permease GlpT is the only fosfomycin transporter in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:6968–6974. doi: 10.1128/JB.00748-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenney E.S., Sargent M., Khan H., Uh E., Jackson E.R., San Jose G., Couch R.D., Dowd C.S., van Hoek M.L. Lipophilic prodrugs of FR900098 are antimicrobial against Francisella novicida in vivo and in vitro and show GlpT independent efficacy. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu H., Leonas K.K., Zhao Y. Antimicrobial Properties and Release Profile of Ampicillin from Electrospun Poly(εepsilon;-caprolactone) Nanofiber Yarns. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2010;5 doi: 10.1177/155892501000500402. 155892501000500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tambe S.M., Sampath L., Modak S.M. In vitro evaluation of the risk of developing bacterial resistance to antiseptics and antibiotics used in medical devices. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;47:589–598. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.EDQM . Microbiological assay of antibiotics. 11th edition. Council of Europe; 2023. European Pharmacopoeia. 2.7.2. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buch P.J., Chai Y., Goluch E.D. Treating Polymicrobial Infections in Chronic Diabetic Wounds. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019;32 doi: 10.1128/CMR.00091-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Percival S.L., Malone M., Mayer D., Salisbury A.M., Schultz G. Role of anaerobes in polymicrobial communities and biofilms complicating diabetic foot ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2018;15:776–782. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolcott R., Costerton J.W., Raoult D., Cutler S.J. The polymicrobial nature of biofilm infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013;19:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.04001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kart D., Tavernier S., Van Acker H., Nelis H.J., Coenye T. Activity of disinfectants against multispecies biofilms formed by Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biofouling. 2014;30:377–383. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2013.878333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandeplassche E., Sass A., Ostyn L., Burmølle M., Kragh K.N., Bjarnsholt T., Coenye T., Crabbé A. Antibiotic susceptibility of cystic fibrosis lung microbiome members in a multispecies biofilm. Biofilm. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2020.100031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hou J., Wang L., Alm M., Thomsen P., Monsen T., Ramstedt M., Burmølle M. Enhanced Antibiotic Tolerance of an In Vitro Multispecies Uropathogen Biofilm Model, Useful for Studies of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections. Microorganisms. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10061207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burmølle M., Webb J.S., Rao D., Hansen L.H., Sørensen S.J., Kjelleberg S. Enhanced biofilm formation and increased resistance to antimicrobial agents and bacterial invasion are caused by synergistic interactions in multispecies biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:3916–3923. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03022-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burmølle M., Ren D., Bjarnsholt T., Sørensen S.J. Interactions in multispecies biofilms: do they actually matter? Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burmølle M., Thomsen T.R., Fazli M., Dige I., Christensen L., Homøe P., Tvede M., Nyvad B., Tolker-Nielsen T., Givskov M., et al. Biofilms in chronic infections - a matter of opportunity - monospecies biofilms in multispecies infections. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2010;59:324–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ibberson C.B., Barraza J.P., Holmes A.L., Cao P., Whiteley M. Precise spatial structure impacts antimicrobial susceptibility of S. aureus in polymicrobial wound infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2212340119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coenye T., Bové M., Bjarnsholt T. Biofilm antimicrobial susceptibility through an experimental evolutionary lens. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2022;8:82. doi: 10.1038/s41522-022-00346-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dijkshoorn L., Tjernberg I., Pot B., Michel M.F., Ursing J., Kersters K. Numerical Analysis of Cell Envelope Protein Profiles of Acinetobacter Strains Classified by DNA-DNA Hybridization. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1990;13:338–344. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(11)80230-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tjernberg I., Ursing J. Clinical strains of Acinetobacter classified by DNA-DNA hybridization. APMIS. 1989;97:595–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turton J.F., Kaufmann M.E., Gill M.J., Pike R., Scott P.T., Fishbain J., Craft D., Deye G., Riddell S., Lindler L.E., Pitt T.L. Comparison of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from the United Kingdom and the United States that were associated with repatriated casualties of the Iraq conflict. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:2630–2634. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00547-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dijkshoorn L., Aucken H., Gerner-Smidt P., Janssen P., Kaufmann M.E., Garaizar J., Ursing J., Pitt T.L. Comparison of outbreak and nonoutbreak Acinetobacter baumannii strains by genotypic and phenotypic methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996;34:1519–1525. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1519-1525.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zurawski D.V., Thompson M.G., McQueary C.N., Matalka M.N., Sahl J.W., Craft D.W., Rasko D.A. Genome sequences of four divergent multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from patients with sepsis or osteomyelitis. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:1619–1620. doi: 10.1128/JB.06749-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stiernagle T. 2006. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook : The Online Review of C. elegans Biology; pp. 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brackman G., Garcia-Fernandez M.J., Lenoir J., De Meyer L., Remon J.P., De Beer T., Concheiro A., Alvarez-Lorenzo C., Coenye T. Dressings Loaded with Cyclodextrin-Hamamelitannin Complexes Increase Staphylococcus aureus Susceptibility Toward Antibiotics Both in Single as well as in Mixed Biofilm Communities. Macromol. Biosci. 2016;16:859–869. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201500437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kugelberg E., Norström T., Petersen T.K., Duvold T., Andersson D.I., Hughes D. Establishment of a superficial skin infection model in mice by using Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3435–3441. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3435-3441.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Breij A., Riool M., Cordfunke R.A., Malanovic N., de Boer L., Koning R.I., Ravensbergen E., Franken M., van der Heijde T., Boekema B.K., et al. The antimicrobial peptide SAAP-148 combats drug-resistant bacteria and biofilms. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan4044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riool M., de Breij A., Kwakman P.H.S., Schonkeren-Ravensbergen E., de Boer L., Cordfunke R.A., Malanovic N., Drijfhout J.W., Nibbering P.H., Zaat S.A.J. Thrombocidin-1-derived antimicrobial peptide TC19 combats superficial multi-drug resistant bacterial wound infections. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Biomembr. 2020;1862 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.EUCAST Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibacterial agents by broth dilution. Clin. Microbiol. Infection. 2003;9 doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00790.x. ix–xv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pillai S.K., Moellering R.C., Eliopoulos G.M. In: Antibiotics in Laboratory Medicine. Lorian V., editor. Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 2005. Antimicrobial combinations; pp. 365–440. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bové M., Bao X., Sass A., Crabbé A., Coenye T. The Quorum-Sensing Inhibitor Furanone C-30 Rapidly Loses Its Tobramycin-Potentiating Activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms during Experimental Evolution. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00413-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aziz R.K., Bartels D., Best A.A., DeJongh M., Disz T., Edwards R.A., Formsma K., Gerdes S., Glass E.M., Kubal M., et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brettin T., Davis J.J., Disz T., Edwards R.A., Gerdes S., Olsen G.J., Olson R., Overbeek R., Parrello B., Pusch G.D., et al. RASTtk: a modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8365. doi: 10.1038/srep08365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.He J., Hao G., Meng Z., Cao Y., Li D. Expanding Melt-Based Electrohydrodynamic Printing of Highly-Ordered Microfibrous Architectures to Cm-Height Via In Situ Charge Neutralization. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021;7:2101197. doi: 10.1002/admt.202101197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Raw whole genome sequencing data are available from ArrayExpress. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.