Abstract

Several human pathogens vectored by the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis Say; Acari: Ixodidae) are endemic in the state of New Jersey. Disease incidence data suggest that these conditions occur disproportionately in the northwestern portion of the state, including in the county of Hunterdon. We conducted active surveillance at three forested sites in Hunterdon County during 2020 and 2021, collecting 662 nymphal and adult I. scapularis. Ticks were tested for five pathogens by qPCR/qRT-PCR: Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti, Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia miyamotoi, and Powassan virus (POWV) lineage 2. Over 2 years, 25.4% of nymphs and 58.4% of adults were found infected with at least one pathogen, with 10.6% of all ticks infected with more than one pathogen. We report substantial spatial and temporal variability of A. phagocytophilum and B. burgdorferi, with high relative abundance of the human-infective A. phagocytophilum variant Ap-ha. Notably, POWV was detected for the first time in Hunterdon, a county where human cases have not been reported. Based on comparisons with active surveillance initiatives in nearby counties, further investigation of non-entomological factors potentially influencing rates of tick-borne illness in Hunterdon is recommended.

Keywords: Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti, Borrelia, Co-infection, Ixodes scapularis, Tick-borne disease

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Ixodes scapularis ticks from Hunterdon County, NJ, USA, screened for five pathogens.

-

•

Relatively high localized prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilum.

-

•

High relative abundance of human-infective variant of A. phagocytophilum.

-

•

First detection of Powassan virus and Borrelia miyamotoi in host-seeking ticks in Hunterdon.

1. Introduction

Blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis Say; Acari: Ixodidae) are the primary vectors of several emerging and established infectious diseases in the northeastern USA. The persistent threat of Lyme disease, caused primarily by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu stricto), accounts for nearly 70% of all reported vector-borne diseases in the USA (CDC, 2022). More recently, other blacklegged tick-borne pathogens, including Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti, Borrelia miyamotoi, and Powassan virus (POWV), have been identified and recognized as adding to the tick-borne disease burden in regions already experiencing increases in Lyme disease case reports (Eisen and Eisen, 2018).

During the period 2015–2020, the state of New Jersey (NJ) recorded the second highest number of reported Lyme disease cases of all USA states (CDC, 2022). This burden is unevenly distributed within the state, with the majority of cases concentrated in the northwestern Skylands region (NJDFW, 2017). Dominated by heavily forested mountains and ridges, the elevation of the Skylands was once considered a barrier to I. scapularis colonization. As recently as the mid-1980s this species was essentially absent from the northern portion of the state, found only in the coastal plains of southern NJ (Schulze et al., 1984). Surveys during this decade witnessed the relatively sudden northward expansion of blacklegged ticks, which by 1987 could be found throughout the state (Schulze et al., 1998), followed by a dramatic upswing in Lyme disease cases in the northwest. Of New Jersey’s 21 counties, four counties in the Skylands, Sussex, Warren, Morris, and Hunterdon, combine for over 53% of the state Lyme disease incidence per 100,000 residents in 2020 (NJSHAD, 2022).

Hunterdon has maintained one of NJ’s highest county-level case rates of Lyme disease since the late 1980s, and since 2015 has led the state in babesiosis incidence (data available to 2021) (NJSHAD, 2022). Anaplasmosis is prevalent throughout the Skylands, with Hunterdon having the second-highest average incidence during the past decade (data available 2010–2021) (NJSHAD, 2022). In 2013, Hunterdon Medical Center confirmed the nation’s first human case of Borrelia miyamotoi disease (BMD) (Gugliotta et al., 2013), a condition now known to occur across much of the northeast and upper Midwest (Burde et al., 2023). While none have yet occurred in Hunterdon County, all of NJ’s POWV cases to date have occurred in the northwest region, primarily in Sussex and Warren Counties (Vahey et al., 2022). Additionally, in 2017 Hunterdon County was the site of the first US detection of the invasive Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis), a species known to carry human pathogens in its native range (Rainey et al., 2018).

Despite a long history of high-incidence blacklegged tick-borne illness, Hunterdon has not been subject to routine tick and tick-borne pathogen surveillance. Given recent developments in the distribution and diversity of ticks and tick-borne pathogens in the northeastern USA, a detailed assessment is warranted. Herein, we assess the prevalence of blacklegged tick-borne pathogens in I. scapularis collected from Hunterdon County forests, with emphasis on the prevalence of emerging pathogens including A. phagocytophilum, B. microti, B. miyamotoi, and POWV, some of which have not previously been detected in Hunterdon County ticks. Our findings are discussed in the context of infection prevalence estimates from surrounding jurisdictions, with special emphasis on comparisons to the routine surveillance programme of Monmouth County, NJ.

2. Methods

2.1. Site descriptions

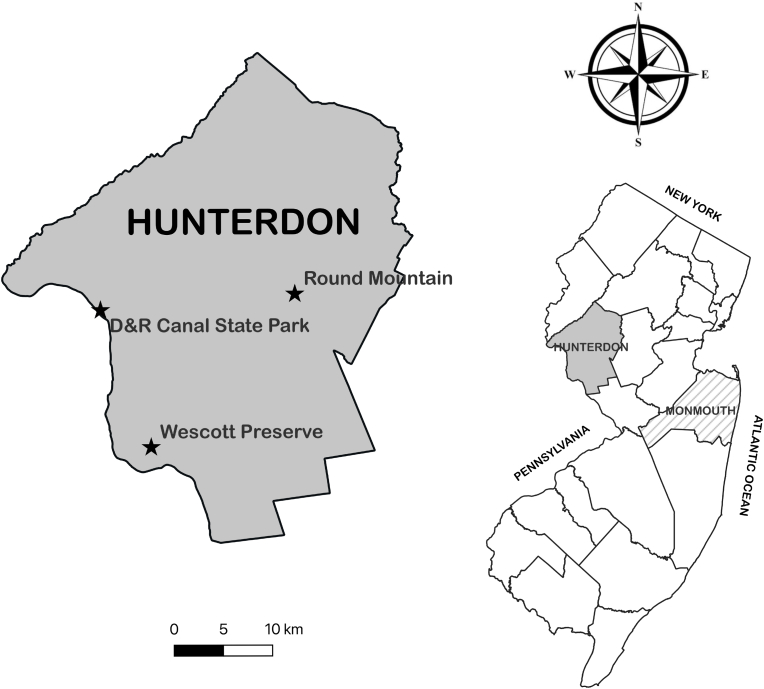

Hunterdon County is located in north-central NJ, across the Delaware River from its western neighbor Pennsylvania. Over 9000 acres of parkland facilitate outdoor recreation across the county, with much of the preserved open space covered by deciduous woodland (HCDPR, 2022). Three forested parks were selected for tick surveillance, with consideration given to broad geographical representation (Fig. 1). One site, at the Round Mountain section of Deer Path Park, had previously been demonstrated to have established populations of I. scapularis (Schulze et al., 1998). Two additional sites (the Delaware & Raritan (D&R) Canal State Park and the Wescott Preserve) were selected to represent the diverse ecological conditions present within Hunterdon forests. Round Mountain, located near the center of Hunterdon County (40.5673°N, 74.8443°W), is dominated by oak-hickory forest. Rocky terrain supports a relatively sparse understory with patches of briars, notably, multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) and wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius). In contrast, both the D&R and Wescott sites have dense layers of understory vegetation. The D&R site (40.5516°N, 75.0773°W), a hardwood forest on the far-western border of the county, is dominated by maple with a substantial tree of heaven (Alianthus altissima) presence. The understory is heavily populated with common nettle and garlic mustard, with some patches of briar (primarily R. multiflora and R. phoenicolasius). To the southeast, the Wescott Preserve (40.4265°N, 75.0158°W) is an oak-dominated forest, featuring some maple and beech. The shrub layer is comprised of multiflora rose, northern spicebush (Lindera benzoin), and Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii). The Lockatong Creek, a tributary of the Delaware River, runs through the preserve.

Fig. 1.

Locations of tick collections in Hunterdon County, NJ.

2.2. Tick collection

During 2020 and 2021, Hunterdon sites were visited approximately bi-weekly during May–July and October–November. Visits took place primarily during the mornings (7:00–10:00 h) or evenings (17:00–19:00 h), coinciding with previously reported I. scapularis questing peaks (Schulze et al., 2001). Site visits were postponed a matter of days in cases of inclement weather (precipitation or high wind). During each visit, researchers collected ticks by dragging and flagging surveys along trails and through adjacent woodland. Flannel flags (60 × 40 cm) were examined every 20 paces (∼10 m) for ticks. Adult and nymphal ticks were removed from cloth with forceps and stored in 90% ethanol. Batches of larvae were removed with tape, but only D. albipictus larvae were counted as this is the only host-seeking life stage of this species. All ticks were identified to species and life stage using published morphological keys (Keirans and Litwak, 1989; Egizi et al., 2019). All I. scapularis nymphs and adults were stored at −20 °C in 90% ethanol until DNA extraction and processing.

2.3. DNA extraction and pathogen testing

Specimen DNA was extracted by the methods of Egizi et al. (2020). Briefly, ticks were removed from ethanol vials and allowed to dry fully. Using sterilized forceps, ticks were placed singly into wells of a 96-well collection plate containing 40 μl Buffer ATL (DNeasy 96 Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA, USA) and one 5 mm stainless steel bead; adult ticks were bisected during transfer to collection tubes (Ammazzalorso et al., 2015). Samples were homogenized in a Qiagen TissueLyser (Qiagen Inc, Hilden, Germany) at 30 Hz for 4 min; collection tube racks were inverted after 2 min and the process was resumed. An additional 140 μl Buffer ATL and 20 μl Proteinase K (Qiagen Inc) were added to each well before overnight incubation at 56 °C. Manufacturer’s protocol (DNeasy 96 Blood & Tissue Kit, Qiagen Inc) was followed for the remainder of the extraction process, with the Elution Buffer volume reduced from 200 μl to 80 μl.

Extracted samples were individually tested for pathogen presence using a quadplex qPCR assay described by Piedmonte et al. (2018) and targeting the 16S rDNA genes of B. burgdorferi and B. miyamotoi (shared F and R primers with species-specific probes) along with A. phagocytophilum msp2 and B. microti 18S rDNA. All probes and primers were synthesized by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). Each reaction was prepared with 5 μl Taqman Multiplex Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and final concentrations as follows: 700 nM Borrelia primers, 125 nM B. burgdorferi probe, 150 nM B. miyamotoi probe, 225 nM A. phagocytophilum primers, 50 nM A. phagocytophilum probe, 250 nM B. microti primers, 50 nM B. microti probe. Nine μl template DNA was used in each reaction, with PCR-grade water used to bring the volume to 25 μl. Synthetic dsDNA fragments (GeneStrings, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) served as positive controls for each target. Amplification was carried out on an AB Quantstudio 5 machine (Applied Biosystems) with initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 45 amplification cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 63 °C for 1 min. Resulting data were visualized and analyzed in Quantstudio Design & Analysis Software application version 1.5.1. Samples with a Ct value ≤ 38 were considered positive.

Samples positive for A. phagocytophilum were further subjected to a real-time PCR genotyping assay (Krakowetz et al., 2014) to distinguish the two predominant A. phagocytophilum strains in North America, the human-infective A. phagocytophilum variant (Ap-ha) and non-human-associated A. phagocytophilum variant 1 (Ap-v1). Each 25 μl reaction was prepared in 12.5 μl TaqMan Environmental Master Mix 2.0 (Applied Biosystems) with final concentrations of 40 nM of each 16S primer and 200 nM of each genotype-specific probe. Amplification was carried out on the AB Quantstudio 5 machine with cycling conditions as described in Krakowetz et al. (2014): 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, and 40 amplification cycles of 95 °C for 15 s followed by 60 °C for 1 min.

Aliquots of extracted ticks were pooled (pools of 8, 2 μl/sample) and tested for the presence of both POWV lineage 1 (prototype POWV) and lineage 2 (deer tick virus; DTV) by qRT-PCR assay published by El Khoury et al. (2013). Each 25 μl reaction consisted of 6.25 μl of TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.175 μl of each 50 μM primer (2 forward, 2 reverse), 0.375 μl of 10 μM probe, 12.675 μl of RNase-free water, and 5 μl of pooled template. Cycling conditions were 50 °C for 5 min, 95 °C for 20 s, and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, followed by 60 °C for 1 min. This assay was repeated on the individual ticks that constituted a positive pool. Positive ticks were then screened with an additional qRT-PCR assay specific to DTV (lineage 2) (Dupuis et al., 2013). Each 25 μl reaction consisted of 6.25 μl of TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.35 μl of each 50 μM primer, 0.375 μl of 10 μM probe, 12.675 μl of RNase-free water, and 5 μl of template. Cycling conditions were the same as the initial Powassan detection assay.

To contextualize findings in Hunterdon, we compared our results qualitatively with published surveillance data from Monmouth County, the only county in NJ with a standardized tick surveillance programme (Jordan et al., 2022). Monmouth’s surveillance results encompass 12 sites distributed across the county, with collections conducted in May-July to target solely the nymphal life stage of I. scapularis. Nymphs were tested for A. phagocytophilum, B. microti, B. burgdorferi, and B. miyamotoi by two duplex qPCR assays (Jordan et al., 2022). Their duplex targeting B. burgdorferi and B. miyamotoi employed the same 16S primer/probe combinations as used in our study, while the duplex targeting A. phagocytophilum and B. microti relied on different published assays sourced from Chan et al. (2013) and Rollend et al. (2013), respectively. The prevalence of POWV in Monmouth is not reported in Jordan et al. (2022).

2.4. Adult tick density estimation and comparison with Monmouth County

A brief inquiry into adult I. scapularis abundance in Hunterdon was performed during the fall of 2021. For a 3-week period during the adult questing season (mid-October through mid-November) (Schulze et al., 1998), each site (Round Mountain, D&R Canal, and Wescott Preserve) was visited once per week. During each visit, five fixed 100-m transects of visibly similar groundcover composition were sampled at a constant walking pace with a 100-m2 crib-flannel drag. Drags were inspected at 10-m intervals, with adult I. scapularis counted and then returned to the environment. All visits were conducted between 8:00 and 11:00 h on rain-free days. This process was also conducted during the same 3-week period at three sites in Monmouth County, NJ, where transects had been previously established as part of the county’s routine tick surveillance efforts (Jordan et al., 2022).

2.5. Data analysis

Infection prevalence of B. burgdorferi, A. phagocytophilum, B. microti, and B. miyamotoi in nymphs and adults was compared across years using pairwise chi-square (χ2) tests. Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess the significance of association between pairs of pathogens (i.e. co-infections). A robust mixed-measures analysis of variance test was applied to adult tick density data, with county (Hunterdon or Monmouth) as the between-subject factor and sampling week as the within-subjects factor. All statistical testing was performed in R statistical software version 4.2.2. The package WRS2 was used for robust analysis of variance testing.

3. Results

3.1. Tick collection

During 2020 and 2021, 232 nymphal and 430 adult I. scapularis were collected from Hunterdon study sites. Other tick species collected included Haemaphysalis longicornis (n = 1034; 843 nymphs, 191 adults), Dermacentor albipictus (n = 111; 111 larvae), Dermacentor variabilis (n = 80; 79 adults, 1 nymph), and Ambylomma americanum (n = 1 nymph); only I. scapularis nymphs and adults were tested for pathogens. Site/year combinations with a sample size of < 20 I. scapularis were excluded from statistical tests comparing infection prevalence (IP) across sites.

3.2. Pathogen prevalence in Ixodes scapularis

Across sites and years, 25.4% (59/232) of I. scapularis nymphs and 58.4% (251/430) of I. scapularis adults were infected with at least one pathogen. Among both nymphs and adults, the most prevalent pathogen was B. burgdorferi, followed by A. phagocytophilum, B. microti, and B. miyamotoi (Fig. 2, Table 1). Deer tick virus was detected in adult ticks from the D&R site in 2020, infecting 4/308 adult ticks from that year (1.3%), two of which were co-infected with other pathogens (Table 2). Within D&R, the 2020 site-specific prevalence of DTV was 4/114 adult ticks or 3.5%. Prevalence of all pathogens was lower in 2021 compared to 2020 (Fig. 2). The decline was significant for B. burgdorferi (χ2 = 11, df = 1, P < 0.001 for nymphs and χ2 = 10.031, df = 1, P = 0.002 for adults), A. phagocytophilum in nymphs (χ2 = 14.8, df = 1, P < 0.001), and B. microti in nymphs (χ2 = 4.322, df = 1, P = 0.038).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence (%) of pathogens detected in Ixodes scapularis nymphs and adults across Hunterdon sites, 2020–2021.

Table 1.

Infection prevalence (including co-infections) in Ixodes scapularis nymphs and adults collected from Hunterdon County, NJ, during 2020 and 2021.

| 2020 |

2021 |

All nymphs | All adults | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nymphs | Adults | Nymphs | Adults | |||

| Total no. tested | 126 | 308 | 106 | 122 | 232 | 430 |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | 26.2 (33) | 53.6 (165) | 8.5 (9) | 36.1 (44) | 16.8 (39) | 48.6 (209) |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | 16.7 (21) | 15.6 (48) | 0.9 (1) | 8.2 (10) | 9.5 (22) | 13.5 (58) |

| Babesia microti | 5.6 (7) | 6.5 (20) | 0 (0) | 4.1 (5) | 3.0 (7) | 6.0 (25) |

| Borrelia miyamotoi | 0.8 (1) | 3.6 (11) | 0.9 (1) | 2.5 (3) | 0.9 (2) | 3.3 (14) |

| Powassan virus | 0 (0) | 1.3 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (4) |

| Total no. infected | 38.1 (48) | 62.3 (192) | 10.4 (11) | 48.4 (59) | 25.4 (59) | 58.4 (251) |

Note: Values represent infection prevalence (IP = percent infected) followed by number of infected ticks in parentheses.

Table 2.

Co-infections detected in Ixodes scapularis in Hunterdon County during 2020 and 2021.

| 2020 |

2021 |

All nymphs | All adults | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nymphs | Adults | Nymphs | Adults | |||

| Total no. tested | 126 | 308 | 106 | 122 | 232 | 430 |

| Borrelia burgdorferi + Anaplasma phagocytophilum | 7.9 (10)* | 10.7 (33)** | 0 (0) | 2.5 (3) | 4.3 (10)** | 8.1 (36)** |

| Borrelia burgdorferi + Babesia microti | 2.4 (3) | 4.2 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.3 (3) | 3.0 (13) |

| Borrelia burgdorferi + Borrelia miyamotoi | 0 (0) | 0.6 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.5 (2) |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum + Babesia microti | 0.8 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum + Borrelia miyamotoi | 0 (0) | 0.6 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.5 (2) |

| Borrelia burgdorferi + Anaplasma phagocytophilum + Powassan virus | 0 (0) | 0.6 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.5 (2) |

| Borrelia burgdorferi + Anaplasma phagocytophilum + Borrelia miyamotoi | 0 (0) | 0.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.2 (1) |

Note: Values represent infection prevalence (IP = percent infected) followed by number of infected ticks in parentheses.

Co-infections occurring at a significantly elevated prevalence (Fisher’s exact test) are denoted by * (P < 0.05) or ** (P < 0.01).

Of 65 successfully genotyped A. phagocytophilum positives, 39 (60%) were of type Ap-ha, while 26 (40%) were of non-human infectious type Ap-v1. The proportion of Ap-ha was highest in 2020 nymphs (15/21 or 71.4%), followed by 2020 adults (22/36 or 61.1%). Although there were far fewer A. phagocytophilum positives in 2021, most genotyped samples were Ap-v1 (6/8 or 75%).

Across the 2020–2021 study period, 70 (10.6%) of ticks were infected with two or more pathogens (Table 2). The prevalence of co-infection was greater among adults (13.0%, 56/430) than among nymphs (6.0%, 14/232). The most frequent co-infection was B. burgdorferi + A. phagocytophilum (7.9% of nymphs and 11.7% of adults during 2020), with these pathogens significantly associated in both nymphal and adult ticks (Fisher’s exact test; P = 0.027 for nymphs and P = 0.004 for adults). Three ticks had triple infections, two of which included DTV (Powassan virus lineage 2) alongside bacterial pathogens A. phagocytophilum and B. burgdorferi (Table 2).

Monmouth County nymphal infection prevalence (NIP) was higher for every pathogen/year except for B. burgdorferi in 2020 (Table 3). Despite this, the incidence of Lyme disease, human babesiosis, and anaplasmosis was consistently several-fold higher in Hunterdon than in Monmouth (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nymphal infection prevalence (NIP) and disease incidence in Hunterdon and Monmouth Counties, 2020 and 2021.

| Pathogen (Disease) | Year | NIP (%) |

Incidence (cases per 100,000) b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunterdon | Monmouth a | Hunterdon | Monmouth | ||

| B. burgdorferi (Lyme disease) | 2020 | 15.87 | 8.29 | 166.9 | 43.7 |

| 2021 | 8.49 | 16.83 | 227.8 | 47.3 | |

| A. phagocytophilum (Anaplasmosis) | 2020 | 7.94 | 8.29 | 11.6 | 0.6 |

| 2021 | 0.94 | 9.90 | 22.3 | 0.9 | |

| B. microti (Babesiosis) | 2020 | 2.38 | 4.86 | 24.8 | 4.4 |

| 2021 | 0 | 15.35 | 20.8 | 5.3 | |

Notes: Borrelia miyamotoi is excluded as Borrelia miyamotoi disease is not nationally notifiable. Deer tick virus is excluded as prevalence of this pathogen was not reported in Jordan et al. (2022). Sample sizes used to calculate NIP are as follows: Hunterdon 2020 (n = 126); Hunterdon 2021 (n = 106); Monmouth 2020 (n = 555); Monmouth 2021 (n = 404).

3.3. Adult density

Across the three weeks of our 2021 dragging survey, the mean density of adult I. scapularis at Hunterdon sites was 0.9 ± 1.3 SD ticks/100 m2. The corresponding 3-site mean in Monmouth was far greater at 3.3 ± 2.3 SD ticks/100 m2. A robust mixed-measures ANOVA confirmed county (Hunterdon vs Monmouth) to have a significant effect on tick abundance (P = 0.002). There was no significant temporal effect on abundance, reflecting consistently elevated densities of questing I. scapularis at Monmouth sites throughout the 3-week survey period.

4. Discussion

4.1. Tick species collected

Of the 11 hard tick species known to occur in New Jersey (Occi et al., 2019), five were collected from Hunterdon study sites during this investigation. Although only I. scapularis nymphs and adults were screened for pathogens, the presence/abundance of other species is relevant, particularly in the context of rapidly diversifying and shifting vector distributions. Notably, H. longicornis (the Asian longhorned tick) was the most abundant species collected at all three Hunterdon sites, as was the case for a recent study to the east, focused on wooded edges in Middlesex County (González et al., 2023). Although primarily considered a livestock threat in the USA at present, H. longicornis is known to opportunistically bite humans (Wormser et al., 2020) and is commonly found infesting companion animals including dogs and cats (Ronai et al., 2020). Haemaphysalis longicornis is a known vector of human disease in its native range and has been found to harbor the A. phagocytophilum Ap-ha variant in neighboring Pennsylvania (Price et al., 2022); however, the full medical importance of this parthenogenetic tick in the USA is currently undetermined. The dominance of this species along publicly accessible trails within Hunterdon County highlights the need to educate residents about tick species other than I. scapularis.

Another tick species of potentially growing importance in Hunterdon County is Amblyomma americanum, the lone star tick. While only a single nymph was flagged during this study, at Round Mountain in 2020, Hunterdon reports 1–4 cases of ehrlichiosis (transmitted by lone star ticks) annually suggesting this species may be established in parts of the county (NJSHAD, 2022). Historically limited to the southern portion of NJ, A. americanum is currently undergoing northern range expansion (Jordan and Egizi, 2019) and is abundant to the east of our sites in Middlesex County (González et al., 2023). As warming temperatures are expected to facilitate continued expansion, residents and healthcare providers should be prepared for increasing risk of human encounters with A. americanum (Linske et al., 2019).

Dermacentor variabilis (the American dog tick) and D. albipictus (the winter tick) were also collected during the study period. To our knowledge, this is the first collection of questing D. albipictus, a one-host tick that infests deer and other cervids, in Hunterdon County. The medical importance of D. variabilis in this region requires further investigation following studies suggesting that they rarely carry pathogenic bacteria in NJ (Occi et al., 2020).

4.2. Prevalence of I. scapularis-borne pathogens

Observed infection prevalence of I. scapularis in Hunterdon County largely followed historical and regional trends. Borrelia burgdorferi is typically the most abundant pathogen in I. scapularis ticks in the northeastern USA, and adult IP (AIP) is usually higher than that of nymphs (NIP) (Barbour and Fish, 1993; Lehane et al., 2021). Previous studies in Hunterdon reported an adult B. burgdorferi IP of 43% in 1996 (Varde et al., 1998) and 50% in 2000–2001 (Schulze et al., 2003) while AIP observed here varied from 20% to 64%.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum IP is more variable in published studies with AIP ranging from 1.5% of adults in New York (Piedmonte et al., 2018) to 26.3% of adults in Rhode Island (Massung et al., 2002). A prior study in Hunterdon reported an AIP of 17% in 1996 (Varde et al., 1998). Only the Ap-ha variant has been implicated in human disease. Data from the northeast suggest that the population structure of A. phagocytophilum in I. scapularis can differ greatly by site and region (Massung et al., 2002; Courtney et al., 2003; Keesing et al., 2014). Reports of Ap-ha relative abundance range from 0% (Courtney et al., 2003) to 100% (Steiner et al., 2008), although these calculations are often based on very small samples of A. phagocytophilum-infected ticks. Our 2020 results place Hunterdon on the higher end of this spectrum, although the near-absence of Ap-ha in 2021 suggests that the relative abundance of human-infective A. phagocytophilum is temporally variable as well.

Our findings for B. microti IP are in line with a prior study in Hunterdon (5%, n = 100 adults; Varde et al., 1998) although this pathogen was not detected in ticks removed from hunter-harvested deer in 2002 (n = 107 adults from Hunterdon; Egizi et al., 2018). In the northeastern USA, B. microti is an emerging pathogen historically concentrated in coastal regions. Recent years have seen a gradual inland expansion in several states (Schulze et al., 2013; Carpi et al., 2016; Goethert et al., 2018), along with a substantial increase in human babesiosis incidence: from 2011 to 2019, NJ saw a 40.9% increase in reported cases (Swanson et al., 2023).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the prevalence of B. miyamotoi and DTV in host-seeking Hunterdon County ticks. In contrast to the previous three pathogens, B. miyamotoi can be passed transovarially from a female tick to the offspring, adding another potential mechanism of infection. Despite this, reported B. miyamotoi IP is generally low compared to other pathogens (< 5%) (Lynn et al., 2022). In both 2020 and 2021, the AIP was nearly double the NIP with B. miyamotoi suggesting that horizontal transmission helps to maintain this pathogen in enzootic cycles and that B. miyamotoi disease, which is not yet nationally notifiable, could be transmitted to humans at any time of year.

Estimates of DTV prevalence also tend to be low in comparison to other I. scapularis-borne pathogens (generally < 5%) (Robich et al., 2019; McMinn et al., 2023), likely reflecting a fleeting viremia in infected vertebrate hosts (Dupuis et al., 2013). Results in Hunterdon were consistent with this; in 2020, only 1.3% of adult I. scapularis tested positive for the virus. However, it should be noted that all four of these positives were male ticks collected in a single visit to the D&R site. The focal nature of tick-borne flaviviruses such as DTV is well documented (Randolph et al., 1999; Heinz et al., 2015; Vogels et al., 2023) and dispersal patterns remain poorly understood, making foci of high risk difficult to predict (Kunze et al., 2022). Interestingly, all DTV detected in Hunterdon was carried by male ticks. This life stage is generally considered medically unimportant, as it is unlikely to feed for long enough to transmit bacterial or protozoal pathogens (Egizi et al., 2018; Falco et al., 2018; Kendall et al., 2020). However, the rapid transmission time of POWV - as little as 15 minutes - may merit the reevaluation of male ticks as vectors (Kendall et al., 2020).

4.3. Prevalence variation across sites and years

The highest IPs measured in this study occurred at the D&R in 2020, including 45.6% of nymphs infected with B. burgdorferi and 30% with A. phagocytophilum (Table 4). The D&R represents the only state park included in this survey and is likely the site with the most foot traffic of the three, indicating a potential for increased risk to park visitors. The park’s Canal Trail, running along the Delaware River, is a popular destination for hiking, jogging, horseback riding, and biking (NJDEP, 2022). Interestingly, some research suggests that riparian zones, i.e. densely vegetated interfaces between waterways and land, may serve as refuges for small mammals (Anthony et al., 1987; Gregory et al., 1991; Hamilton et al., 2015). While the associations between riparian ecology and tick abundance/infection have not been thoroughly explored, at least one investigation has demonstrated an elevated incidence of Lyme disease along river corridors (Frank et al., 2002). Original research is recommended to explore the relative risk of Lyme disease exposure for visitors of this unique riparian ecosystem.

Table 4.

Number of detections and prevalence of major Ixodes scapularis-borne pathogens (Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti and Borrelia miyamotoi) at sites in Hunterdon County during 2020 and 2021.

| Site | Year | n | No. of ticks infected (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. burgdorferi | A. phagocytophilum | B. microti | B. miyamotoi | |||

| Round Mt | 2020 | 67 N | 6 (9.0) | 4 (6.0) | 4 (6.0) | 0 (0) |

| 121 A | 63 (52.1) | 9 (7.4) | 8 (6.6) | 4 (3.3) | ||

| 2021 | 54 N | 5 (9.3) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | |

| 80 A | 22 (27.5) | 4 (5.0) | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.5) | ||

| Delaware & Raritan | 2020 | 57 N | 26 (45.6) | 17 (29.8) | 3 (5.3) | 1 (1.8) |

| 114 A | 73 (64.0) | 33 (28.9) | 9 (7.9) | 4 (3.5) | ||

| 2021 | 24 N | 4 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 22 A | 12 (54.5) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Wescott | 2020 | 2 N | na | na | na | na |

| 73 A | 29 (39.7) | 6 (8.2) | 3 (4.1) | 3 (4.1) | ||

| 2021 | 28 N | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 20 A | 4 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.0) | ||

Abbreviations: N, nymphs; A, adults; n, number of ticks tested.

Infection prevalence for B. burgdorferi, A. phagocytophilum, and B. microti showed a large decline from 2020 to 2021. Preliminary data from Hunterdon in 2019 (n = 109 I. scapularis nymphs, measured IP of 26.6% for B. burgdorferi, 8.2% for A. phagocytophilum, and 8.2% for B. microti) is more in line with 2020 levels, but it is difficult to draw conclusions about interannual trends from a 2–3-year period. Periodic changes in tick IP could be related to cyclical fluctuations in rodent populations, a phenomenon driven in part by interannual patterns in acorn mast (Elias et al., 2004; Ostfeld et al., 2006; Clotfelter et al., 2007). Studies from the northeastern USA have documented rapid declines in rodent populations immediately following highly productive mast years, a scenario that might leave large cohorts of immature I. scapularis unable to feed on infected rodent hosts (Elias et al., 2004; Clotfelter et al., 2007). Researchers in Monmouth County (coastal NJ) also observed a large short-term decline in both B. burgdorferi and A. phagocytophilum NIP over two years (2017–2018) with an eventual recovery to 2017-level IP in 2021 (Jordan et al., 2022). Asynchronous declines observed in Monmouth and Hunterdon counties (separated by approximately 30 km) suggests that fluctuations in host assemblage between the two regions may be relatively independent and highlights the need for surveillance in diverse regions of NJ as discussed below.

4.4. Co-infections

Simultaneous infection by multiple pathogens was observed among both nymphal and adult ticks, although this phenomenon was far more common among adults (13% of adults co-infected versus 6% of nymphs co-infected). This discrepancy is not unexpected; while host-seeking nymphs have had only a single opportunity to feed, their adult counterparts have fed twice and may have acquired different infections from different hosts (Swanson et al., 2006). Although nymphal I. scapularis are generally considered the more medically important life stage, the risk presented by adult infection (and co-infection) should not be disregarded. In the northeastern USA, adult I. scapularis are active during the autumn and winter months, when vigilance against tick encounters may be lacking (Jordan and Egizi, 2019). Notably, a 10-year passive surveillance programme in Monmouth County, NJ, found submissions of adult female I. scapularis (n = 1575) to rival those of nymphal I. scapularis (n = 1415). A substantial proportion (38.8%) of female I. scapularis removed from human hosts were partially or fully engorged, reflecting the potential transmission of pathogens (Jordan and Egizi, 2019).

Among both nymphal and adult I. scapularis collected in Hunterdon, the frequency of co-infection between B. burgdorferi and A. phagocytophilum was greater than expected based on single infection percentages. Although the sample size for B. burgdorferi + A. phagocytophilum co-infected nymphs was smaller (n = 10) than that of adults (n = 39), co-infected ticks of both life stages were concentrated at the D&R site. Elevated prevalence of co-infection between B. burgdorferi and A. phagocytophilum (particularly Ap-ha) has been previously reported in I. scapularis (Swanson et al., 2006; Hamer et al., 2014). These pathogens share several small mammal reservoirs, including Peromyscus leucopus (Keesing et al., 2014; Barbour et al., 2015) and there is some evidence for enhanced pathogen acquisition (e.g. by tick vectors) in cases of dual infection that may be attributed to the immunosuppressive capabilities of A. phagocytophilum (Thomas et al., 2001; Holden et al., 2005).

The risk of co-infection acquisition has numerous implications for disease pathology and detection. Simultaneous infection by B. burgdorferi and A. phagocytophilum or B. microti may result in exacerbated Lyme disease symptoms (including arthritis) as well as non-specific febrile symptoms associated with HGA and babesiosis (Swanson et al., 2006). Co-infections may also complicate diagnosis and treatment, particularly when only one agent produces a visible infection. In Lyme disease-endemic areas, the presence of an erythema migrans (EM) lesion may be considered sufficient for clinical diagnosis and treatment with antibiotics (Lantos et al., 2016). Failure to investigate potential co-infections may lead to the underdiagnosis of pathogens such as A. phagocytophilum and B. microti.

4.5. Comparisons with Monmouth County

Historically, Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases emerged first in southern/coastal New Jersey, and their expansion into the northwest (including Hunterdon County) was more recent (Schulze et al., 1998; Egizi et al., 2018). A 1996 study comparing I. scapularis tick populations between Hunterdon and Monmouth County did not find evidence of higher entomological risk (of Lyme disease) in Hunterdon, despite a higher burden of human disease (Schulze et al., 1998). Similarly, our results fail to explain the substantial and consistent discrepancy in human disease incidence between Hunterdon and Monmouth Counties. In both 2020 and 2021, the incidence of Lyme disease, human babesiosis, and anaplasmosis was several-fold higher in Hunterdon than in Monmouth (Table 3). Although estimates of NIP in Hunterdon must be qualified by relatively small sample sizes, the pattern of higher pathogen prevalence among Monmouth nymphs appears to contradict human incidence data. One possible explanation is that the two counties could differ in the specific strains of pathogens circulating and their propensity to infect humans. In Hunterdon, the majority of nymphal A. phagocytophilum samples genotyped were Ap-ha (68.1%; 15/22), the human infectious strain, whereas only 9.9% (7/71) were Ap-ha during those same two years in Monmouth (Jordan et al., 2022).

The regional abundance of questing ticks is also likely to play a role in the risk of TBD infection. However, both historical and present contexts suggest that blacklegged ticks may be more abundant in coastal Monmouth County than inland Hunterdon. During the autumn of 1996, Schulze et al. (1998) estimated the density of adult I. scapularis adults at a representative Monmouth County site, Naval Weapons Station Earle (NWSE), to be roughly 4-fold that of Round Mountain in Hunterdon County. Despite the passage of a quarter century, the pattern we observed in the autumn of 2021 was nearly identical, with NWSE averaging 3.73 I. scapularis adults per 100 m2 compared to only 1.13 adults per 100 m2 at Round Mountain. The elevated density of I. scapularis adults in Monmouth remained consistent over the 3-week sampling period at all three sites. It should be noted that both investigations (1996 and 2021) focused on single adult cohorts of I. scapularis; recent work in Monmouth County has demonstrated single-site tick abundance to vary substantially from year-to-year (Schulze and Jordan, 2022).

Overall, factors other than tick infection prevalence and abundance likely play substantial roles in the varying reported human incidence between the two counties. For example, the majority of healthcare facilities in Hunterdon County are part of one entity, Hunterdon Healthcare, which has simplified the workflow for providers by adopting a tick-borne testing panel in its electronic health management system. The panel includes Lyme disease serology and PCR testing for Babesia spp., A. phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia spp., and B. miyamotoi (R. Puelle, personal communication). Of note, Hunterdon County reported the majority of NJ’s probable (1/1) and confirmed (17/24) BMD cases from 2020–2021 (K. Cervantes, personal communication). Given the voluntary status of BMD reporting in NJ, it seems likely that this figure reflects unique testing and reporting practices in Hunterdon. Additionally, human behavioral factors, including recreational location preferences, may contribute to variability in tick encounter risk (Borșan et al., 2021; Hassett et al., 2022).

5. Conclusions

We report here a benchmark study demonstrating the presence of five human pathogens in host-seeking I. scapularis in Hunterdon County, NJ. As is well-established for tick-borne pathogens, our study noted significant spatiotemporal variation in infection prevalence, highlighting the difficulty in interpreting county-wide disease risk from a limited number of sites. A finding of particular public health importance is the presence of ticks with triple co-infections (B. burgdorferi + A. phagocytophilum + DTV) at the D&R site in 2020; even as a transient phenomenon this may contribute to cases of human co-infection, making diagnosis and treatment more difficult. In regions where tick co-infections are likely, suspected and confirmed cases of Lyme disease should be screened for other blacklegged tick-borne diagnoses. The detection of DTV, a pathogen with a comparatively short transmission time, also signals a need for altered public health messaging surrounding tick-borne disease prevention and tick removal.

Funding

This work was made possible through a generous donation from the Hunterdon Healthcare Foundation to D. Price, and partially supported by a USDA-NIFA Multistate NE1943 capacity grant (NJ08540) to D. Price. We would like to acknowledge continued support from the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zoe E. Narvaez: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Tadhgh Rainey: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Rose Puelle: Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing. Arsala Khan: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Robert A. Jordan: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Andrea M. Egizi: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Dana C. Price: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the generous assistance of Kim Cervantes of the NJ Department of Health, as well as the staff of the Hunterdon County Mosquito & Vector Control Programme.

Contributor Information

Zoe E. Narvaez, Email: zoe.narvaez@rutgers.edu.

Andrea M. Egizi, Email: andrea.egizi@co.monmouth.nj.us.

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The raw data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Ammazzalorso A.D., Zolnik C.P., Daniels T.J., Kolokotronis S.O. To beat or not to beat a tick: Comparison of DNA extraction methods for ticks (Ixodes scapularis) PeerJ. 2015;3 doi: 10.7717/peerj.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony R.G., Forsman E.D., Green G.G.R., Witmer G., Nelson S. Small mammal populations in riparian zones of different-aged coniferous forests. Murrelet. 1987;68:94–102. doi: 10.2307/3534114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour A.G., Bunikis J., Fish D., Hanincová K. Association between body size and reservoir competence of mammals bearing Borrelia burgdorferi at an endemic site in the northeastern United States. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:299. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0903-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour A.G., Fish D. The biological and social phenomenon of Lyme disease. Science. 1993;260:1610–1616. doi: 10.1126/science.8503006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borșan S.D., Trif S.R., Mihalca A.D. Recreational behaviour, risk perceptions, and protective practices against ticks: A cross-sectional comparative study before and during the lockdown enforced by the COVID-19 pandemic in Romania. Parasites Vectors. 2021;14:423. doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-04944-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burde J., Bloch E.M., Kelly J.R., Krause P.J. Human Borrelia miyamotoi infection in North America. Pathogens. 2023;12:553. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12040553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpi G., Walter K.S., Mamoun C.B., Krause P.J., Kitchen A., Lepore T.J., et al. Babesia microti from humans and ticks hold a genomic signature of strong population structure in the United States. BMC Genom. 2016;17:888. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3225-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2022. Lyme disease data and surveillance.https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Chan K., Marras S.A., Parveen N. Sensitive multiplex PCR assay to differentiate Lyme spirochetes and emerging pathogens Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia microti. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:295. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotfelter E.D., Pedersen A.B., Cranford J.A., Ram N., Snajdr E.A., Nolan V., Ketterson E.D. Acorn mast drives long-term dynamics of rodent and songbird populations. Oecologia. 2007;154:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s00442-007-0859-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney J.W., Dryden R.L., Montgomery J., Schneider B.S., Smith G., Massung R.F. Molecular characterization of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes scapularis ticks from Pennsylvania. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:1569–1573. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1569-1573.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis A.P., Peters R.J., Prusinski M.A., Falco R.C., Ostfeld R.S., Kramer L.D. Isolation of deer tick virus (Powassan virus, lineage II) from Ixodes scapularis and detection of antibody in vertebrate hosts sampled in the Hudson Valley, New York State. Parasites Vectors. 2013;6:185. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egizi A., Bulaga-Seraphin L., Alt E., Bajwa W.I., Bernick J., Bickerton M., et al. First glimpse into the origin and spread of the Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, in the United States. Zoonoses Public Health. 2020;67:637–650. doi: 10.1111/zph.12743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egizi A., Roegner V., Faraji A., Healy S.P., Schulze T.L., Jordan R.A. A historical snapshot of Ixodes scapularis-borne pathogens in New Jersey ticks reflects a changing disease landscape. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egizi A.M., Robbins R.G., Beati L., Nava S., Vans C.R., Occi J.L., Fonseca D.M. A pictorial key to differentiate the recently detected exotic Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann, 1901 (Acari, Ixodidae) from native congeners in North America. ZooKeys. 2019;818:117–128. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.818.30448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen R.J., Eisen L. The blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis: An increasing public health concern. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury M.Y., Hull R.C., Bryant P.W., Escuyer K.L., St George K., Wong S.J., et al. Diagnosis of acute deer tick virus encephalitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;56:e40–e47. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias S., Witham J.W., Hunter M.L. Peromyscus leucopus abundance and acorn mast: Population fluctuation patterns over 20 years. J. Mammal. 2004;85:743–747. doi: 10.1644/ber-025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falco R.C., Daniels T.J., Vinci V., McKenna D., Scavarda C., Wormser G.P. Assessment of duration of tick feeding by the scutal index reduces need for antibiotic prophylaxis after Ixodes scapularis tick bites. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;67:614–616. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C., Fix A.D., Peña C.A., Strickland G.T. Mapping Lyme disease incidence for diagnostic and preventive decisions, Maryland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:427–429. doi: 10.3201/eid0804.000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goethert H.K., Molloy P., Berardi V., Weeks K., Telford S.R. Zoonotic Babesia microti in the northeastern U.S.: Evidence for the expansion of a specific parasite lineage. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González J., Fonseca D.M., Toledo A. Seasonal dynamics of tick species in the ecotone of parks and recreational areas in Middlesex County (New Jersey, USA) Insects. 2023;14:258. doi: 10.3390/insects14030258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory S.V., Swanson F.J., McKee W.A., Cummins K.W. An ecosystem perspective of riparian zones. Bioscience. 1991;41:540–551. doi: 10.2307/1311607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gugliotta J.L., Goethert H.K., Berardi V.P., Telford S.R. Meningoencephalitis from Borrelia miyamotoi in an immunocompromised patient. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:240–245. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer S.A., Hickling G.J., Walker E.D., Tsao J.I. Increased diversity of zoonotic pathogens and Borrelia burgdorferi strains in established versus incipient Ixodes scapularis populations across the Midwestern United States. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;27:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton B.T., Roeder B.L., Hatch K.A., Eggett D.L., Tingey D. Why is small mammal diversity higher in riparian areas than in uplands? J. Arid Environ. 2015;119:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2015.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett E., Diuk-Wasser M., Harrington L., Fernandez P. Integrating tick density and park visitor behaviors to assess the risk of tick exposure in urban parks on Staten Island, New York. BMC Publ. Health. 2022;22:1602. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13989-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HCDPR . About Us; 2022. Hunterdon County Division of Parks and Recreation.https://co.hunterdon.nj.us/489/About-Us [Google Scholar]

- Heinz F.X., Stiasny K., Holzmann H., Kundi M., Sixl W., Wenk M., et al. Emergence of tick-borne encephalitis in new endemic areas in Austria: 42 years of surveillance. Euro Surveill. 2015;20:9–16. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.13.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden K., Hodzic E., Feng S., Freet K.J., Lefebvre R.B., Barthold S.W. Coinfection with Anaplasma phagocytophilum alters Borrelia burgdorferi population distribution in C3H/HeN mice. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:3440–3444. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3440-3444.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan R.A., Egizi A. The growing importance of lone star ticks in a Lyme disease endemic county: Passive tick surveillance in Monmouth County, NJ, 2006–2016. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan R.A., Gable S., Egizi A. Relevance of spatial and temporal trends in nymphal tick density and infection prevalence for public health and surveillance practice in long-term endemic areas: A case study in Monmouth County, NJ. J. Med. Entomol. 2022;59:1451–1466. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjac073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesing F., McHenry D.J., Hersh M., Tibbetts M., Brunner J.L., Killilea M., et al. Prevalence of human-active and variant 1 strains of the tick-borne pathogen Anaplasma phagocytophilum in hosts and forests of eastern North America. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014;91:302–309. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keirans J.E., Litwak T.R. Pictorial key to the adults of hard ticks, family Ixodidae (Ixodida: Ixodoidea), east of the Mississippi River. J. Med. Entomol. 1989;26:435–448. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/26.5.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall B.L., Grabowski J.M., Rosenke R., Pulliam M., Long D.R., Scott D.P., et al. Characterization of flavivirus infection in salivary gland cultures from male Ixodes scapularis ticks. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowetz C.N., Dibernardo A., Lindsay L.R., Chilton N.B. Two Anaplasma phagocytophilum strains in Ixodes scapularis ticks, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:2064–2067. doi: 10.3201/eid2012.140172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze M., Banović P., Bogovič P., Briciu V., Čivljak R., Dobler G., et al. Recommendations to improve tick-borne encephalitis surveillance and vaccine uptake in Europe. Microorganisms. 2022;10:1283. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10071283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantos P.M., Auwaerter P.G., Nelson C.A. Lyme disease serology. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016;315:1780–1781. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehane A., Maes S.E., Graham C.B., Jones E., Delorey M., Eisen R.J. Prevalence of single and coinfections of human pathogens in Ixodes ticks from five geographical regions in the United States, 2013–2019. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2021;12 doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linske M.A., Williams S.C., Stafford K.C., Lubelczyk C.B., Henderson E.F., Welch M., Teel P.D. Determining effects of winter weather conditions on adult Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) survival in Connecticut and Maine, USA. Insects. 2019;11:13. doi: 10.3390/insects11010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn G.E., Breuner N.E., Hojgaard A., Oliver J., Eisen L., Eisen R.J. A comparison of horizontal and transovarial transmission efficiency of Borrelia miyamotoi by Ixodes scapularis. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.102003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massung R.F., Mauel M.J., Owens J.H., Allan N., Courtney J.W., Stafford K.C., Mather T.N. Genetic variants of Ehrlichia phagocytophila, Rhode Island and Connecticut. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:467–472. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.010251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMinn R.J., Langsjoen R.M., Bombin A., Robich R.M., Ojeda E., Normandin E., et al. Phylodynamics of deer tick virus in North America. Virus Evol. 2023;9 doi: 10.1093/ve/vead008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NJDEP, 2022. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. D&R Canal State Park. https://nj.gov/dep/parksandforests/parks/drcanalstatepark.html. (Accessed 12 November 2022).

- NJDFW . 2017. New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife. New Jersey Landscape Project, Version 3.3.https://dep.nj.gov/njfw/conservation/new-jerseys-landscape-project/ [Google Scholar]

- NJSHAD . 2022. New Jersey State Health Assessment Data. New Jersey Communicable Disease Reporting and Surveillance System (CDRSS)http://nj.gov/health/shad [Google Scholar]

- Occi J.L., Egizi A.M., Goncalves A., Fonseca D.M. New Jersey-Wide survey of spotted fever group Rickettsia (Proteobacteria: Rickettsiaceae) in Dermacentor variabilis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae) Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;103:1016. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjz010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occi J.L., Egizi A.M., Robbins R.G., Fonseca D.M. Annotated list of the hard ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae) of New Jersey. J. Med. Entomol. 2019;56:589–598. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjz010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostfeld R.S., Canham C.D., Oggenfuss K., Winchcombe R.J., Keesing F. Climate, deer, rodents, and acorns as determinants of variation in Lyme-disease risk. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedmonte N.P., Shaw S.B., Prusinski M.A., Fierke M.K. Landscape features associated with blacklegged tick (Acari: Ixodidae) density and tick-borne pathogen prevalence at multiple spatial scales in central New York state. J. Med. Entomol. 2018;55:1496–1508. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjy111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price K.J., Ayres B.N., Maes S.E., Witmier B.J., Chapman H.A., Coder B.L., et al. First detection of human pathogenic variant of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in field-collected Haemaphysalis longicornis, Pennsylvania, USA. Zoonoses Public Health. 2022;69:143–148. doi: 10.1111/zph.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey T., Occi J.L., Robbins R.G., Egizi A. Discovery of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Ixodida: Ixodidae) parasitizing a sheep in New Jersey, United States. J. Med. Entomol. 2018;55:757–759. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjy006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph S.E., Miklisová D., Lysy J., Rogers D.J., Labuda M. Incidence from coincidence: Patterns of tick infestations on rodents facilitate transmission of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Parasitology. 1999;118:177–186. doi: 10.1017/s0031182098003643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robich R.M., Cosenza D.S., Elias S.P., Henderson E.F., Lubelczyk C.B., Welch M., Smith R.P. Prevalence and genetic characterization of deer tick virus (Powassan virus, Lineage II) in Ixodes scapularis ticks collected in Maine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019;101:467–471. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollend L., Bent S.J., Krause P.J., Usmani-Brown S., Steeves T.K., States S.L., et al. Quantitative PCR for detection of Babesia microti in Ixodes scapularis ticks and in human blood. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:784–790. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronai I., Tufts D.M., Diuk-Wasser M.A. Aversion of the invasive Asian longhorned tick to the white-footed mouse, the dominant reservoir of tick-borne pathogens in the USA. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2020;34:369–373. doi: 10.1111/mve.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze T.L., Bowen G.S., Lakat M.F., Parkin W.E., Shisler J.K. Geographical distribution and density of Ixodes dammini (Acari: Ixodidae) and relationship to Lyme disease transmission in New Jersey. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1984;57:669–675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze T.L., Jordan R.A. Daily variation in sampled densities of Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs at a single site-implications for assessing acarological risk. J. Med. Entomol. 2022;59:741–751. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjab213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze T.L., Jordan R.A., Healy S.P., Roegner V.E. Detection of Babesia microti and Borrelia burgdorferi in host-seeking Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in Monmouth county, New Jersey. J. Med. Entomol. 2013;50:379–383. doi: 10.1603/me12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze T.L., Jordan R.A., Hung R.W. Comparison of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) populations and their habitats in established and emerging Lyme disease areas in New Jersey. J. Med. Entomol. 1998;35:64–70. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze T.L., Jordan R.A., Hung R.W. Effects of selected meteorological factors on diurnal questing of Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidade) J. Med. Entomol. 2001;38:318–324. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze T.L., Jordan R.A., Hung R.W., Puelle R.S., Markowski D., Chomsky M.S. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae) in Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) adults in New Jersey, 2000–2001. J. Med. Entomol. 2003;40:555–558. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner F.E., Pinger R.R., Vann C.N., Grindle N., Civitello D., Clay K., Fuqua C. Infection and co-infection rates of Anaplasma phagocytophilum variants, Babesia spp., Borrelia burgdorferi, and the rickettsial endosymbiont in Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) from sites in Indiana, Maine, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. J. Med. Entomol. 2008;45:289–297. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[289:iacroa]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson M., Pickrel A., Williamson J., Montgomery S. Trends in reported babesiosis cases - United States, 2011–2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023;72:273–277. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7211a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson S.J., Neitzel D., Reed K.D., Belongia E.A. Coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006;19:708–727. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00011-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas V., Anguita J., Barthold S.W., Fikrig E. Coinfection with Borrelia burgdorferi and the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis alters murine immune responses, pathogen burden, and severity of Lyme arthritis. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:3359–3371. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3359-3371.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahey G.M., Wilson N., McDonald E., Fitzpatrick K., Lehman J., Clark S., et al. Seroprevalence of Powassan virus infection in an area experiencing a cluster of disease cases: Sussex County, New Jersey, 2019. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022;9:ofac023. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varde S., Beckley J., Schwartz I. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes scapularis in a rural New Jersey county. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1998;4:97–99. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels C.B.F., Brackney D.E., Dupuis A.P., Robich R.M., Fauver J.R., Brito A.F., et al. Phylogeographic reconstruction of the emergence and spread of Powassan virus in the northeastern United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2218012120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormser G.P., McKenna D., Piedmonte N., Vinci V., Egizi A.M., Backenson B., Falco R.C. First recognized human bite in the United States by the Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;70:314–316. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The raw data are available from the corresponding author upon request.