Abstract

This quantitative study investigates the relationships of green human resource management (GHRM) practices (e.g., green training and involvement, green recruitment, green performance management and compensation, and green transformational leadership) on green organizational culture and pro-environmental behavior, and the moderating role of green social capital and green values. This study adopts a cross-sectional design and collects quantitative data from 232 respondents working in top-to middle-level managerial positions in medium and large enterprises using a questionnaire survey after obtaining a list of companies from the Securities and Exchange Commission of Lahore, Rawalpindi, and Multan in Pakistan, applying the snowball sampling technique. A combined approach including partial least squares structural equation modeling and necessary condition analysis is employed to unravel the underlying mechanism between GHRM practices, green organizational culture, and pro-environmental behavior using Smart PLS version 4. The findings reveal that green transformational leadership (β = 0.267, p < 0.01), green performance management and compensation (β = 0.412, p < 0.01), green training and involvement (β = 0.226, p < 0.01) have a significant positive connection with green organizational culture. Moreover, green social capital (β = 0.206, p < 0.01), green values (β = 0.460, p < 0.01), and green organizational culture (β = 0.143, p < 0.05) have a significant influence on workplace pro-environmental behavior. The study did not discover any moderating influence of green values and GS on the relationship between green organizational culture and pro-environmental behavior. Nevertheless, it did identify a mediating effect of green organizational culture in the connections between green recruitment, green training & involvement, green performance management & compensation, green transformational leadership, and pro-environmental behavior. The original contribution of this study includes offering in-depth insights into the relationship between GHRM practices and pro-environmental behavior through an integrated framework combining the GHRM framework, ability motivation opportunity (AMO) theory, and norm activation model to the extant literature. With its empirical investigation, this constitutes a pioneering study in the field of GHRM that offers numerous practical implications with the robust result obtained using sufficiency logic tests applying necessary condition analysis. Organizations should recruit employees with green values and give them training, and performance and compensation benefits to ensure green transformational leadership and enhance pro-environmental behavior in the organization.

Keywords: Green human resource management, Green organizational culture, Necessary condition analysis, Workplace behavior, Pro-environmental behavior

1. Introduction

Global warming caused by continuous environmental degradation has led to natural disasters worldwide. The calamitous floods in monsoon 2022, were the worst in the recorded history of Pakistan. It affected approximately 33 million people, killed approximately 1667 people, and caused a loss of approximately 15.2 billion USD [1]. There is a dire need to tackle these issues, and environmental management has great potential to deal with it [2]. Environmental management must not be considered only a policy rather it should be integrated with the change agent of the organization, that is, human resources. Thus, green human resource management (GHRM) practices have emerged through the integration of environmental and human resource management. GHRM inculcates pro-ecological values, beliefs, and behaviors in employees to improve the organization's green performance [3]. GHRM helps employees create a green environment by developing green abilities, creating motivation for employee engagement in tasks with constraints on green aspects, and providing green opportunities. Green abilities can be developed through eco-friendly recruitment and selection as well as ecological training and development [4]. The motivation for employees to engage in green tasks can be enhanced by eco-friendly performance management, compensation and green reward and pay systems [5]. Eco-friendly opportunities for employees can be provided through green involvement and green leadership [6]. The GHRM in organizations have great potential for prevailing environment friendly awareness of employees or achieving a green environment in their industries and institutions [7]. GHRM practices promote pro-environmental behavior in the workforce [8,9]. Moreover, an organization's workforce and its behavior help shape the organization to achieve green organizational goals [10].

Despite the eminent role of pro-environmental behavior (PEB) of the workforce in dealing with the increasing global environmental concerns and meeting the environmental management standards, little research has been conducted in this field [11]. The existing studies [12,13] have confirmed the direct relation between GHRM practices and PEB, green organizational culture (GO) [14], environmental values [15], and green innovation [16]. Further investigations are needed to understand the underlying mechanism of the role of GHRM in enhancing pro-environmental behavior [17]. Employees adopt GO in association with the HRM department of the organization as culture shapes the values, beliefs, and behaviors of employees through the process of hiring, training, and appraisal [18].

Moreover, the existing research on GHRM and pro-environmental behavior has been conducted in developed Western nations [4,9]. However, research in developing countries is still in its infancy [19]. Renwick et al. [6] highlight that there has been less research on GHRM and suggest ways that it can help sustain the environment in the most vulnerable countries in Asia. Going green is not mandatory for companies in Pakistan, but all companies adopt sustainable practices as an obligation to their stakeholders [20]. In addition, ability-motivation-opportunity (AMO) has been used to understand the mechanism underlying GHRM, GO, and employees’ pro-environmental behavior [9,21]. The value-belief-norm theory has been employed to discuss the interaction of green values (GV) and pro-environmental behavior [17]. An integrated framework to predict workplace pro-environmental behavior is not present for empirical verification.

Existing research of Al-Swidi et al. [22] evaluated the green organizational culture as a mediator variable within the environmental concern, green leadership behaviour, green human resource management, and green employee behavior relationships. Yet, the study ignored the classified GRHM concept such as green recruitment, green training, green compensation etc. and the moderation within these components and pro-environmental behavior. Likewise, although green social capital is studied as the moderating variable between the green process innovation and financial performance relationship [23], the moderating role of green social capital between the relationships between green organizational culture and workplace pro-environmental behavior is not considered so far. Also, individual green values had been found as a moderating variable between the GHRM-in role behavior and extra-role behavior [24]. However, the moderation effects of green values between green organizational culture and pro-environmental behavior are missing in the literature. Therefore, this framework must be investigated further. The gaps in the extant literature can be summarized/presented in the form of the following questions:

-

(1)

How do GHRM practices predict pro-environmental behavior?

-

(2)

Does green organizational culture mediate the relationship between GHRM practices and pro-environmental behavior?

-

(3)

Does green social capital (GS) and green values moderate between green organizational culture and pro-environmental behavior?

To address the literature gaps and answer the abovementioned questions, we first investigate the connection of GHRM practices on green organizational culture; and the link of green organizational culture, green social capital, green values on pro-environmental behavior in the workplace in Pakistan. Second, the interactive influences of green organizational culture on pro-environmental behavior. Finally, the moderating role of green social capital and green values moderates the correlations of green organizational culture on workplace pro-environmental behavior. Another purpose of the study is to apply necessity and sufficiency logics to gain a deeper understanding of the GHRM activities that organizations must or should adopt to promote workplace pro-environmental behavior. In this context, we apply the combined approach of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and necessary condition analysis to recognize GHRM activities with necessity and sufficiency logics. This study contributes to GHRM literature by extending the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory framework to green social capital. To our knowledge, green social capital has not yet been integrated into the VBN theory. Thus, this study will contribute to exploring the relationship, mediation, and interactions of GHRM, green organizational culture, workplace pro-environmental behavior, green social capital, and green values under the AMO and VBN theory frameworks.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

A three-dimensional interactive model was proposed to promote the work performance of the organization, that includes capacity (ability, knowledge, health, skills, intellectual ability, education level, stamina, energy level, and motor skills) and willingness (motivation, job satisfaction, work status, attitude, values, social rules, perceived role expectations, and feelings of fairness) [25]. It also includes opportunities that comprise the availability of required tools, materials, and equipment, workplace conditions, leader behavior, mentoring, actions of coworkers, and business policies, rules, and procedures [25]. Better results for work performance are achieved when relevant work practices are employed together in the organization [26]. In a study conducted on US manufacturing, high-performance work systems are concluded to be the result of mixed practices of employee ability level, enhanced motivation, and the provision of opportunity to contribute [27]. The interactive relationship of performance can be represented as P = f (A, M, O), where P, A, M, and O represent performance, ability, motivation, and opportunity, respectively. The combined implementation of ability, motivation, and opportunity, also known as the AMO framework, has been well accepted as HRM practices by organizations for enhanced performance. The importance of this framework is also evident from the fact that several studies on the linkage between HRM and performance employ this theoretical framework for a comprehensive understanding [28].

Several studies have adopted the AMO framework to describe the association between GHRM and organizational ecological protection practices [2], green employee behavior [22], and green creativity [29]. Abilities refer to hiring and selecting employees with eco-friendly behavior as well as training and development of green skills among these employees. Motivating employees through performance and compensation management programs and providing incentives and green transformational leadership can provide opportunities through a green organizational culture. Stern et al. [30] introduced the value-belief-norm theory to provide a framework for environmental studies to investigate the normative values that promote pro-environmental behavior. The VBN theory is the integration of the value theory [31], norm-activation model [32] and new environmental paradigm [33]. This theory postulates that a chain of variables forms the pro-environmental behavior, starting from values and individuals' environmental concerns to specific beliefs about the negative outcomes of specific actions. An individual's ability and responsibility to react to these negative outcomes form the personal norms of an individual.

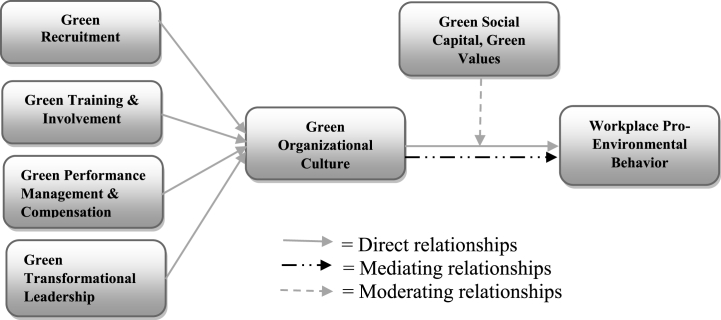

According to VBN theory, person values, beliefs, and norms influence employee work behavior [30]. This theory is supported by several empirical studies that have shown a pronounced link of personal environmental values on personal environment friendly behavior [34,35]. This implies that employees’ personal green values directly influence workplace pro-environmental behavior. Fig. 1 shows the conceptual framework of this study.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Framework of workplace pro-environmental behavior.

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. Green Human Resource Management and green organizational culture (GO)

Organizational culture is the representation of the shared values, beliefs, and behaviors of the members of an organization [36]. The values of a society stand for the principles or standards of social behavior set by its members to determine what is morally right or wrong, proper or improper, and desirable or undesirable. Beliefs are convictions about the nature of reality that an individual or a group of people in a society believe to be true [37]. Behaviors are the ways in which individuals act towards others, and they are based on the values and beliefs of the individuals in a society. Organizational culture is shaped by employees’ behaviors that are exhibited through their habits that are developed in performing their daily routine workplace tasks according to the organizational philosophy [38]. GO is the result of organizational culture extending its philosophy to green environmental objectives. Thus, GO encompasses the values, beliefs, and behaviors of employees in the organization concerning the green aspects of the environment in performing organizational tasks; this provides guidance for adopting eco-friendly behavior to conserve and protect the environment [39]. GHRM has great potential to promote green organizational culture by infusing or developing values, beliefs, and behaviors concerning the environment in their employees through recruitment, selection, training, performance management, and transformational leadership [21].

GHRM, specifically training, performance management, and compensation and reward systems help develop workplace pro-environmental behavior, which consequently promotes a green organizational culture in the company. GO and GHRM are embedded in each other as the effective integration of GHRM in the organization helps promote GO. More environmentally conscious employees will be attracted to an organization, which will further enhance pro-environmental organizational culture, resulting in a highly environmentally conscious workforce in the organization. GHRM urges organizations to restructure their culture to resolve environmental and sustainability-related issues [40]. Hadjri et al. [41] explored that green recruitment, green training and green compensation significantly influence the green organizational culture. Al-Ghazali et al. [42] identified that green transformational leadership significantly affect green organizational identity. We argue that four GHRM practices, including green recruitment (GR), green training and involvement (GT), green performance management and compensation (GP) [22,43], and green transformational leadership (GL), help develop GO in the organization. Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1

Green recruitment has a positive association with green organizational culture.

H2

Green training and involvement has a positive association with green organizational culture.

H3

Green performance management and compensation has a positive association with green organizational culture.

H4

Green transformational leadership has a positive association with green organizational culture.

2.2.2. Green organizational Culture and workplace pro-environmental behavior (PEB)

The most valuable assets of an organization are humans, and their satisfaction with their job; their relationships in the organization are shaped by organizational culture [12,44]. Culture is a code of conduct that shapes the behavior and attitudes of employees, and it is inclined to adopt new strategies to help employees manage their behavior in a vigorously changing work environment to sustain a balanced system [45]. An organization's employees assimilate themselves into the organizational culture. The standards and norms of the organization are transferred through organizational culture, and these standards help shape the workplace behavior of employees [46]. Thus, culture motivates employees to adopt behavior that is critical for the success of the organization. Green organizational culture shapes employees' behavior in environmental friendly ways, such as minimal use of printing materials, turning off electrical devices when not in use, and using recyclable materials for personal food or water consumption [12,47]. Employees learn about the green culture of their organization through the top leadership's efforts to educate and train them through seminars and workshops [22]. GO enculturates the way employees think adopting green behavior is crucial for individuals and organizational groups, and the way employees feel this philosophy is adopted in the organization [48]. The employees' conscious efforts to go green and adopt green behavior is not only beneficial for themselves but also for the prospects that GO alters the employees' behavior and attitude, and induces them to make efforts to preserve nature [49]. Thus, GO helps promote PEB by encouraging employees to preserve the internal and external environments of the organization. This leads us to the following proposition:

H5

Green organizational culture has positive association with workplace pro-environmental behavior.

2.2.3. Green social capital (GS) and PEB

A network with specific norms and values that promotes cooperation within a group or among groups can be termed social capital. Social capital results in better collective efforts within a given community to achieve environmental goals and to protect natural resources [50,51]. High levels of social trust in a country help the relevant management and industries to recycle efficiently [52]. This directly evidences that social capital plays a vital role in green environmental development. Thus, GS can be defined as the social relationships among employees in an organization or among organizations for constructive discussion, sharing of knowledge and experiences, and generation of new ideas to improve environmental performance [23]. Such social interaction among employees is not predetermined by the firm but is fostered by environmental commitment and collaboration among employees [53].

Various studies relevant to GS have been conducted, such as on employee willingness to provide suggestions for ecological improvements [54], information exchange among employees about the environmental aspects of activities performed in the organization and constructive environmental discussions [55], sharing of ecological knowledge and experiences [56], and shared assistance to improve the ecological performance of the firm [57]. The role of social capital in community-based ecotourism studies showed that economic benefits have a more direct association with residents’ pro-environmental behavior and cognitive social capital (i.e., values, attitudes, and beliefs) compared to structural social capital (i.e., norms and rules of the community) which has a partially mediating relationships [40]. It was concluded that high-level social capital, particularly cognitive capital, encourages pro-environmental behavior of the residents. Based on the positive impact of social capital on environment and sustainability, and its potential to promote green values, attitudes, and norms, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6

Green social capital has a positive association with workplace pro-environmental behavior.

H8

Green social capital moderates the association between green organizational culture and workplace pro-environmental behavior.

2.2.4. Green values (GV) and pro-environmental behavior

Values are stable individual characteristics that help distinguish individuals from their peers by assessing their behavioral differences. Green values are defined as employees' perceptions of environmental sustainability and their motivation to preserve the environment [58]. Several studies have shown that human values are reflected in environmental behavior [59], and promote pro-environmental behaviors [30]. This association is explained by the value-belief norm theory, according to which individuals' behavior is shaped by their values, beliefs, and norms [30]. Several studies have demonstrated that individuals with green values are self-motivated to engage in pro-environmental behaviors [34]. Green values affect both PEB and the interaction of individual and institutional values in a direction that supports the organization's green initiatives and relevant practices [60]. Green values have a profound positive relationship with an individual's green behavior [61]. As a result of conformity within employees' green values and the organization's green culture, employees exhibit more environment friendly behavior at the workplace. Considering the potential role of GHRM in reflecting the green values of the organization, we propose that employees' green values positively affect the relationship between GHRM and employees' PEB. GO infuses the environmental values in its employees, which are adopted and practiced by all [44]. GO in an organization accentuates the workforce to adopt eco-friendly values and behavior [62]. Based on arguments from the extant literature that suggest that individuals' values have a positive role in shaping their behavior towards environmental behavior, we propose the following hypotheses:

H7

Green values have a positive association with promoting workplace pro-environmental behaviour.

H9

Green values moderate the link between green organizational culture and workplace pro-environmental behaviour.

2.2.5. Green Human Resource Management, green organizational culture, and pro-environmental behavior

Roscoe et al. [21] stated that, after the recruitment and hiring of green employees, the HRM department endorses PEB among those employees through training programs, performance management, and transformational leadership. They argued that PEB is demonstrated by employees while performing their routine tasks, and with the passage of time, the exhibition of such behavior by employees when interacting within the organization to tackle issues of environmental sustainability collectively emerges as a habit and green organizational culture is developed in the organization. GHRM practices promote environment friendly behavior in employees and contribute to the green workplace where the workforce of the organization has a positive bonding with their leader, and employees are motivated to achieve the green and sustainable goals of the organization [63]. Studies have explored the mediating connections of GO between GHRM and environmental performance [64], sustainability and green innovation [65], and GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behavior [22]. The green values of the employees in an organization work as core elements in establishing GHRM. Based on this preposition of environment friendly values and behavior, the following organizational environmental culture is developed:

HM1-4

Green organizational culture mediates the link between green recruitment, green training and involvement, green performance management and compensation, and green transformational leadership on workplace pro-environmental behaviour.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Participants and procedure

Using the positivist paradigm as a guide, this quantitative study uses a deductive and explanatory research method to determine the causes of the constructs [66]. The research ethics committee of Bahauddin Zakaria University, Multan, Pakistan have approved this study (Approval Number: 155/UREC/2022). In this empirical study, we apply a cross-sectional survey technique using a questionnaire approach to gather data from managers working in medium and large enterprises in Pakistan from October–November 2022. Punjab is the most densely populated province in Punjab, with more than half the country's total population residing there [67]. The five largest cities of Punjab—Lahore, Rawalpindi, Faisalabad, Multan, and Gujranwala— are among the major cities of Pakistan. For this study, Lahore, Rawalpindi, and Multan have been selected, because the population residing in these cities is the most representative of the Pakistani population. An email was sent to the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan to provide us with a list of authorized companies in these cities. The Securities and Exchange Commission of Lahore, Rawalpindi, and Multan provided a list of 350 medium and large enterprises. In Pakistan, a Medium Enterprise (ME) is a company that has a workforce of over 50 but less than 100 employees in the case of trading establishments and employs over 50 but less than 250 employees for manufacturing and service establishments. If the workforce exceeds 100 employees, it is classified as a large enterprise [68]. Before the data were collected, a letter was sent to the human resource departments of the chosen companies to ask for permission and find people to interview. Employees working at different managerial posts were approached using convenience sampling. To reach the maximum number of respondents in the same enterprise, snowball sampling technique was adopted. Statistical power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.7 was applied to determine the minimum sample size [69]. Thus, with a power of 0.95, f2 = 0.15 and for 7 predictors, the least required appropriate sample size was 153 which confirms the validity of the sample size used in the study. In the 15 selected organizations, 350 questionnaires were sent, and 232 responses were received, with a 66% response rate. Written informed consent was obtained from respondents who participated in the survey. After the data cleaning process and removal of outliers, 226 responses were deemed valid for data analysis.

3.2. Measurement instruments

The questionnaire for this study consisted of 33 items, and the constructs were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). To measure GT and GP, the items were adapted from Mousa and Othman, [70]. For GL, a scale comprising of four items was adapted from Chen and Chang, [71]. The construct of GS was measured using a scale adapted with four items of Delgado-Verde et al. [72], and a 4-items scale was adapted to measure green values [73]. The questionnaire for GO and PEB comprised four items each, which were adapted from Yeşiltaş et al. [9], and Robertson and Barling [74], respectively.

3.3. Common method bias (CMB)

First, the result of the Harman single factor test is 31.4%, which is below the threshold of 50%, so there is no common method bias problem in the data [75]. In addition, based on Kock's [76] suggestions, we evaluate CMB to assess the full collinearity of the constructs (Table 1). All variance inflation factors (VIF) are below the standard value of 3.3 confirming the absence of common method bias within the constructs [76]. An alternative way to address this issue is to identify the latent factor correlations. According to Podsakoff et al. [75], the correlation values of the latent factor must be less than 0.90, and the greatest value we found in this study is 0.684 in this study; therefore, CMB is not an issue.

Table 1.

Full collinearity test.

| GR | GT | GP | GT | GS | GV | GO | PEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Inflation Factors | 1.914 | 2.313 | 2.356 | 2.373 | 2.490 | 2.431 | 2.480 | 2.009 |

Note: GR - Green Recruitment, GT - Green Training & Involvement, GP - Green Performance Management & Compensation, GL - Green Transformational Leadership, GO - Green Organizational Culture, GS - Green Social Capital, GV - Green Values, PEB - Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour.

3.4. Multivariate normality

Using appropriate data analysis techniques to check for multivariate normality is crucial. In this study, we estimated multivariate normality using the Web Power online tool [77]. The results of the multivariate normality test revealed that the p-values for Mardia's multivariate skewness and kurtosis were below 0.05, indicating non-normality. Thus, to accommodate non-normal data, the current study utilized PLS-SEM. The SEM approach is considered to provide better estimations than regression for mediation and moderation [78]. PLS-SEM is a satisfactory approach for evaluating complex frameworks involving moderation relationships [79]. Therefore, we employed PLS-SEM using Smart-PLS 4.0.

3.5. Data analysis tools

In this study, the analysis was performed in three stages. First, the reliability and validity of the measurement model was assessed. In the second stage, SEM was performed to elaborate on the relationship between the predictor and latent constructs, and the mediation and moderation relationship. In the last stage, necessary condition analysis (NCA) and bottleneck analysis were performed to gain an in-depth understanding of the relationships between the constructs.

To ensure robustness, this study used a combination of PLS-SEM and NCA to investigate the necessity logic from the perspective of GHRM practices for green organizational culture and pro-environmental behavior in the workplace, following Sukhov et al. [80]. Necessity logic refers to a specific activity that must be present with a critical value to acquire a specific outcome. The absence of necessary conditions causes failure of a specific outcome [81]. The NCA is a new statistical analysis approach that identifies single necessary causes (i.e., independent variables) to achieve the target outcomes (dependent variable) [81]. The combined use of PLS-SEM and NCA is suggested to advance theorizing and theory testing [82]. The study also applied the result of importance-performance map analysis (IPMA), which also looks at how well each construct works to extend PLS-SEM. Thus, managerial initiatives can be prioritized based on their importance and performance [83].

4. Results

4.1. Demographic details

For data analysis, 226 valid responses were analyzed. To measure the demographic characteristics of the respondents, data on gender, age, education, position, tenure, and type of firm were collected, and they are presented in Table 2. Of these respondents, 66.8% (151) were male. In regards to age, most respondents were in the 26–35 years category (43.8%, 99), followed by the 36–45 years old category (30.5%, 69). The least responses were obtained for the 56–65 years old category (1.8%, 4), followed by the responses obtained for 18–25 years old category (7.1%, 16). In regards to education, most respondents had a master's degree (71.2%, 161), whereas those with bachelors and MPhil (or MS) degrees constituted 11.5% and 11.1%, respectively. Only 6.2% (14) respondents had PhD qualifications. The data collected for managerial positions of the respondents showed that the majority corresponded to the middle management positions (52.2%, 118), followed by the first-level management positions (15%, 34), which was followed by the executive (or senior) management and intermediate (or experienced) staff (12.4%, 28), and the minimum number of responses were from the entry level staff (8%,18). With regards to tenure, most responses were from people with 1–5 years of experience (38.1%, 86); it was followed by the group of people with 6–10 years of experience (27.0%, 61), and then by the group with 11–15 years of experience (15.9%, 36).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics (N = 226).

| f |

% |

f |

% |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Position | ||||

| Male | 151 | 66.8 | Executive or Senior Management | 28 | 12.4 |

| Female | 75 | 33.2 | Middle Management | 118 | 52.2 |

| Total | 226 | 100.0 | First-level Management | 34 | 15.0 |

| Intermediate or Experienced (Senior Staff) | 28 | 12.4 | |||

| Age | Entry level | 18 | 8.0 | ||

| 18–25 Years | 16 | 7.1 | Total | 226 | 100.0 |

| 26–35 Years | 99 | 43.8 | |||

| 36–45 Years | 69 | 30.5 | Tenure | ||

| 46–55 Years | 38 | 16.8 | Less than one Year | 22 | 9.7 |

| 56–65 Years | 4 | 1.8 | 1–5 Years | 86 | 38.1 |

| Total | 226 | 100.0 | 6–10 Years | 61 | 27.0 |

| 11–15 Years | 36 | 15.9 | |||

| Education | 16–20 Years | 11 | 4.9 | ||

| Bachelors or Equivalent | 26 | 11.5 | More than 20 Years | 10 | 4.4 |

| Masters or Equivalent | 161 | 71.2 | Total | 226 | 100.0 |

| M. Phil or Equivalent | 25 | 11.1 | |||

| Doctorate or Equivalent | 14 | 6.2 | Type of Firm | ||

| Total | 226 | 100.0 | Public | 71 | 31.4 |

| Private | 85 | 35.4 | |||

| Multinational | 75 | 33.2 | |||

| Total | 226 | 100.0 |

4.2. Measurement model

4.2.1. Reliability and validity

To ensure the reliability of the constructs used in the study, internal consistency reliability was assessed by calculating Cronbach's Alpha and Composite Reliabilities (i.e., ρa and ρc) (see Table 3). The values of composite reliability, ρc, for all variables are within the recommended range (0.70–0.90) [79]. The values of composite reliability (ρa) for all variables remained within the lower bound Cronbach's alpha and the upper bound composite reliability (ρc), confirming a higher level of internal consistency within the constructs.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity.

| Variables | No. Items | Mean | Standard Deviation | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite reliability (rho_a) | Composite reliability (rho_c) | Average Variance Extracted | Variance Inflation Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR | 5 | 3.678 | 0.720 | 0.747 | 0.752 | 0.840 | 0.569 | 1.815 |

| GT | 4 | 3.930 | 0.667 | 0.775 | 0.777 | 0.855 | 0.597 | 2.033 |

| GP | 4 | 3.537 | 0.687 | 0.759 | 0.766 | 0.838 | 0.510 | 2.058 |

| GL | 5 | 3.898 | 0.699 | 0.800 | 0.813 | 0.869 | 0.624 | 1.774 |

| GS | 4 | 3.870 | 0.676 | 0.791 | 0.801 | 0.865 | 0.616 | 2.114 |

| GV | 4 | 4.004 | 0.707 | 0.789 | 0.804 | 0.863 | 0.612 | 1.782 |

| GO | 6 | 3.777 | 0.671 | 0.743 | 0.746 | 0.838 | 0.565 | 2.238 |

| PEB | 4 | 3.891 | 0.639 | 0.675 | 0.699 | 0.802 | 0.507 | – |

Note: GR - Green Recruitment, GT - Green Training & Involvement, GP - Green Performance Management & Compensation, GL - Green Transformational Leadership, GO - Green Organizational Culture, GS - Green Social Capital, GV - Green Values, PEB - Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour.

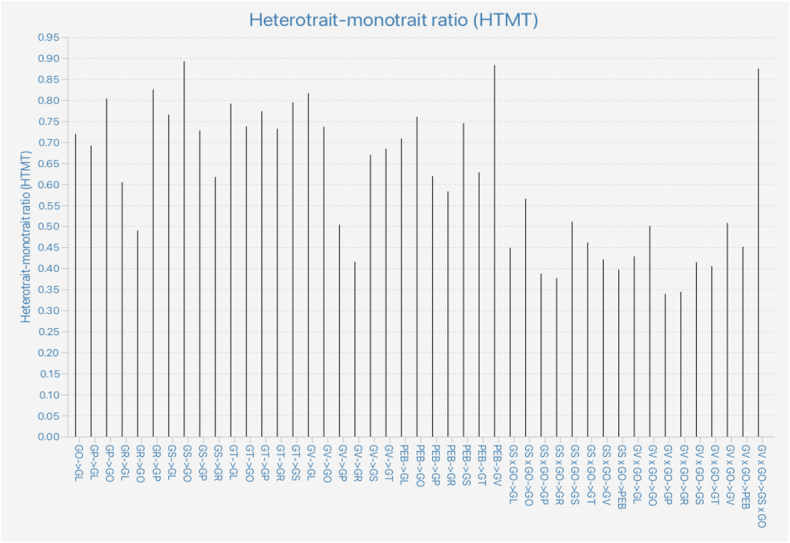

After confirming reliability and discriminant validity, we applied both the Fornell and Lacker's criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio (see Fig. 2 and Table 4). The standard value of HTMT is less than 0.90, and any value exceeding this limit indicates low levels of discriminant validity [45]. All values in the HTMT matrix were below the threshold value (i.e., 0.90) confirming a high level of discriminant validity.

Fig. 2.

Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) Matrix.

Table 4.

Fornell-Larcker criterion.

| GR | GT | GP | GL | GS | GV | GO | PEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR | 0.754 | |||||||

| GT | 0.556 | 0.773 | ||||||

| GP | 0.630 | 0.601 | 0.714 | |||||

| GL | 0.470 | 0.619 | 0.550 | 0.790 | ||||

| GS | 0.471 | 0.623 | 0.561 | 0.612 | 0.785 | |||

| GV | 0.319 | 0.540 | 0.398 | 0.645 | 0.534 | 0.782 | ||

| GO | 0.372 | 0.562 | 0.608 | 0.569 | 0.684 | 0.569 | 0.751 | |

| PEB | 0.415 | 0.467 | 0.453 | 0.530 | 0.546 | 0.672 | 0.548 | 0.712 |

Note: The bold off-diagonal values are the square root of AVE, GR - Green Recruitment, GT - Green Training & Involvement, GP - Green Performance Management & Compensation, GL - Green Transformational Leadership, GO - Green Organizational Culture, GS - Green Social Capital, GV - Green Values, PEB - Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour.

The variance inflation factors (VIF) is determined to evaluate multicollinearities for all measurement items. All calculated VIF values are less than the suggested cut-off value (i.e., 5.0), confirming the absence of multicollinearity. Thus, there is no multicollinearity problem. The discriminant validity (DV) of the model used in this study is estimated using Fornell and Larcker's criterion [45]. These results satisfy the Fornell and Lacker's criterion as all the square root of AVE (off-diagonal value) in Table 4, are higher than each of the correlations, which indicates the greater level of discriminant validity.

4.2.2. Structural modeling

Fig. 3 and Table 5 exhibit all the proposed hypotheses, and all hypotheses from H1–H8 were accepted. Green training & involvement (β = 0.226, t-value = 2.467), green performance management & compensation (β = 0.412, t-value = 6.090) and green transformational leadership (β = 0.267, t-value = 3.111) has a significant connection with green organizational culture. Likewise, green organizational culture (β = 0.143, t-value = 1.966), green social capital (β = 0.206, t-value = 2.866). and green values (β = 0.460, t-value = 7.309) has a significant association with employee's pro-environmental behaivor. Although green recruitment (β = −0.139, t-value = 1.750) has a p-value<0.05, hence H1 is not supported due to its relationship direction being opposite as hypothesized. All the values for coefficient of determination (R2) are greater than 0.40 thus showing a good fit for the model.

Fig. 3.

Measurement model.

Table 5.

Hypothesis testing.

| Hypothesis | Beta | CI Min |

CI Max |

t Value |

p Value |

r2 | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | GR → GO | −0.139 | −0.265 | −0.003 | 1.750 | 0.040 | Not Accepted* | |

| H2 | GT → GO | 0.226 | 0.072 | 0.374 | 2.467 | 0.007 | 0.478 | Accepted |

| H3 | GP → GO | 0.412 | 0.301 | 0.523 | 6.090 | 0.000 | Accepted | |

| H4 | GL → GO | 0.267 | 0.124 | 0.411 | 3.111 | 0.001 | Accepted | |

| H5 | GO → PEB | 0.143 | −0.001 | 0.282 | 1.660 | 0.048 | Accepted | |

| H7 | GS → PEB | 0.206 | 0.097 | 0.332 | 2.866 | 0.002 | 0.515 | Accepted |

| H8 | GV → PEB | 0.460 | 0.361 | 0.566 | 7.309 | 0.000 | Accepted | |

| Moderating Effect | ||||||||

| H9 | GS*GO → PEB | 0.066 | −0.058 | 0.199 | 0.846 | 0.199 | No Moderation | |

| H10 | GV*GO → PEB | −0.077 | −0.202 | 0.034 | 1.068 | 0.143 | No Moderation | |

| Mediating Effect | ||||||||

| HM1 | GR → GO → PEB | −0.020 | −0.048 | 0.003 | 1.210 | 0.113 | No Mediation | |

| HM2 | GT → GO → PEB | 0.032 | −0.001 | 0.075 | 1.333 | 0.091 | No Mediation | |

| HM3 | GP → GO → PEB | 0.059 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 1.530 | 0.063 | No Mediation | |

| HM4 | GL → GO → PEB | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.084 | 1.425 | 0.077 | No Mediation | |

Note: * Although the p-value is below 0.05, the hypothesis is insignificant for it is a negative relationship opposite to the hypothesis statement. GR - Green Recruitment, GT - Green Training & Involvement, GP - Green Performance Management & Compensation, GL - Green Transformational Leadership, GO - Green Organizational Culture, GS - Green Social Capital, GV - Green Values, PEB - Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour.

All values for the coefficient of determination (R2) are greater than 0.40, thus showing a good fit for the model. This study has no significant link with the interaction between GS and GO (GS∗GO) on employees' pro-environmental behavior (β = 0.066, t-value = 0.846), and the interaction between green values and green organizational culture (green values∗green organizational culture) on employees' pro-environmental behavior (β = −0.077, t-value = 1.068); hence, no moderation is found in the proposed model (p > 0.05). In addition, GO shows no mediation relationship between GHRM practices (GR, GT, GP, GL) and employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Thus, hypotheses H9-10 and HM1-HM4 are rejected.

4.2.3. Importance-performance map analysis (IPMA)

Instead of showing standardized factor loading or weights, the results of IMPA reveal the performance values for each latent construct. This is the case regardless of whether the variables in question are formative or reflective. Our results (Fig. 4) show that green values have the highest importance, whereas GS and GO have a relatively higher importance. However, GP, GL, and GT have lower values of importance on a specified scale. The performance of all constructs lies between 70 and 75% except for GP and GR. Green recruitment has a negative value on the importance axis.

Fig. 4.

Impa findings.

4.2.4. Necessary condition analysis (NCA)

To gain insights into the link between GHRM practices and GO, Table 6 presents the NCA size effect of different independent variables on GO. The NCA results indicate that GR (effect size = 0.161), GP (effect size = 0.212), and GL (effect size = 0.259) have a medium effect (0.1 ≤ d < 0.3) on GO, whereas GT has a large connection with GO, with a value of 0.350 (0.3≤ d < 0.5). All constructs are highly statistically significant as indicated by their p-values presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

NCA effect size.

| Variables | Green Organizational Culture (GO) |

Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour (PEB) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size |

Permutation p-Value | Effect Size |

Permutation p-Value | |

| GR | 0.161 | 0.000 | ||

| GT | 0.350 | 0.000 | ||

| GP | 0.212 | 0.000 | ||

| GL | 0.259 | 0.000 | ||

| GO | 0.218 | 0.000 | ||

| GS | 0.198 | 0.000 | ||

| GV | 0.285 | 0.000 | ||

| GS* GO | 0.008 | 0.616 | ||

| GV* GO | 0.008 | 0.621 | ||

Note: GR - Green Recruitment, GT - Green Training & Involvement, GL - Green Transformational Leadership, GP - Green Performance Management & Compensation, GS - Green Social Capital, GV - Green Values.

The NCA effect size of different parameters on pro-environmental behavior was also explored in this study (see Table 6). GO, GS, and green values have medium effect (0.1 ≤ d < 0.3) with size effect values of 0.218, 0.198, and 0.285, respectively. All these variables are highly significant with a p-value of 0.000. However, the moderating relationship of green social capital and green values with GO on employees’ pro-environmental behavior is insignificant (p > 0.05). To further interpret tithe NCA results, a bottleneck analysis was performed (see Table 7). The first column corresponds to the outcome levels ranging from 0% for the least observed value to 100% for the highest observed value. All other columns provide conditional levels (expressed as actual values) to achieve certain outcomes for GO and pro-environmental behavior. To achieve a level of GO in the range 10–40%, the minimum necessary values for all four determinants (i.e., GL = GT = 1.327 and GP = GR = 0.885) must be satisfied. To increase the level of GO to 50%, we need to attain the minimum values for GR and GT equal to 1.770, whereas the minimum values for GL and GP are 1.327 and 0.885, respectively. However, to achieve a higher GO level (i.e., ≥ 80%), the values of GL, GP, GR, and GT must be at least 3.540, 13.274, 3.540, and 29.319, respectively. In the case of pro-environmental behavior, none of the relevant determinants (see columns 6-10) require any necessary value (not necessary = NN) to achieve a level of less than 50%. To achieve a pro-environmental behavior level in the range 50–80%, three necessary conditions must be satisfied. However, to achieve a higher PEB level (i.e., 90%), the necessary values for all determinants must be attained (i.e., GO = 4.867, GS = 8.407, GV = 16.372, GS × GO = 6.195, and GV × GO = 1.770).

Table 7.

NCA bottleneck analysis (Percentage).

| Percentage | Green Organizational Culture |

Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GL | GP | GR | GT | GO | GS | GV | GS x GO | GV x GO | |

| 0% | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 10% | 1.327 | 0.885 | 0.885 | 1.327 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 20% | 1.327 | 0.885 | 0.885 | 1.327 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 30% | 1.327 | 0.885 | 0.885 | 1.327 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 40% | 1.327 | 0.885 | 0.885 | 1.327 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 50% | 1.327 | 0.885 | 1.770 | 1.770 | 2.655 | 0.885 | 2.655 | NN | NN |

| 60% | 1.327 | 3.097 | 3.540 | 1.770 | 2.655 | 0.885 | 3.540 | NN | NN |

| 70% | 1.327 | 4.425 | 3.540 | 6.195 | 2.655 | 0.885 | 3.540 | NN | NN |

| 80% | 3.540 | 13.274 | 3.540 | 28.319 | 3.097 | 0.885 | 3.982 | NN | NN |

| 90% | 3.540 | 13.274 | 3.540 | 29.204 | 4.867 | 8.407 | 16.372 | 6.195 | 1.770 |

| 100% | 3.540 | 25.664 | 3.540 | 35.398 | 51.327 | 66.814 | 57.080 | 44.248 | 47.345 |

Note: GR - Green Recruitment, GT - Green Training & Involvement, GP - Green Performance Management & Compensation, GL - Green Transformational Leadership, GO - Green Organizational Culture, GS - Green Social Capital, GV - Green Values, PEB - Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour.

5. Discussion

As expected, the study results show that GHRM through GT, GP, and GL motivates employees to adopt GO, excluding green recruitment on GO (H1-4). These outcomes are consistent with previous research [19,22] that the implementation of GHRM practices and policies stimulates green organizational culture. This signifies that enhanced green training or involvement, better performance management, and sound green transformational leadership influence employees to embrace a green organizational culture. However, green recruitment was not relevant to the adoption of organizational culture. The reasons may be that the respondents were doubtful about the availability of candidates with prior green knowledge of the existing green topics and their extent. Likewise, hypotheses (H5-8) predicted a significant relationship between GO, GS, green values and pro-environmental behavior, and the results of this study confirm the relationships significantly. This outcome is in line with those of previous studies [35,84,85]. This implies that employees with enriched green organizational culture, enhanced green social capital, and amplified green values lead to pro-environmental behavior in an organization.

Unexpectedly, there was no moderating effect of GS and GO on pro-environmental behavior, as expected in hypothesis H9. This result contradicts the result of a previous study [86]. Although green values and GO have no moderating effect on pro-environmental behavior (H10), these results are corroborated by previous studies [87]. These results indicate that GS and green values dampen the association between GO and pro-environmental behavior. This insignificant moderation may be due to the decreased variance in GS (SD = 0.676) and GS (SD = 0.707) scores, showing similar green preferences among employees [87]. Employees who are aware of the environmental harms produced by industrial operations are more likely to care; they build GS and green values equally if they are aware of the rapid pace at which environmental deterioration is occurring. Since there is little variation in the sampled workers’ environmental orientation, the moderation effect might have been missed. Additionally, to understand the mechanism underlying the relationship between green recruitment, GT, GP, GL, and pro-environmental behavior, a green organizational culture is proposed to mediate this relationship (HM1-M4). However, the outcomes fail to accept the mediating role of green organizational culture on the relationship between GR, GT, GP, GL, and pro-environmental behavior. These outcomes are contradictory to those of previous studies [14,84] but in line with the studies of Aggarwal and Agarwala [88].

The necessary condition analysis (NCA) size effect reveals that GR, GP, and GL have a medium effect on GO, whereas GT has a large size effect. However, PLS-SEM results do not support the hypothesis that green recruitment has a significant effect on GO. Thus, NCA successfully captures the feature that is missing in PLS-SEM analysis because the former focuses on the necessary conditions, whereas the latter presents average results [82]. In addition, the large effect of GT on GO indicate that it has the highest constraint on the required outcome. Thus, organizations should prioritize the GT of employees in the workplace. The bottleneck analysis for GO highlights that all GHRM practices (i.e., GR, GP, GL, and GT) need necessary conditions with different threshold levels to achieve a very low-level (i.e., 10%) outcome of GO in the organization. If any of the threshold values for these constructs are not provided, the desired outcome level for the green organization level is not targeted. Bottleneck analysis provides guidance to GHRM for prioritizing different constructs to achieve a medium-level (i.e., 60%) outcome of green organizational culture. Green recruitment must be the top priority (critical value = 3.540), GP must be the second priority (critical value = 3.097), and GT must be the third priority (critical value = 1.770). GL is a significant determinant, as inferred from PLS-SEM results, and has a constant critical value for achieving low-to medium-level outcomes; this suggests that any increase in this construct will increase the outcome on an average [82]. It is worth noting that the priority order from the GHRM perspective for these constructs is changed to achieve a medium-to high-level (i.e., 80%) outcome for GO. The priority order is as follows.

The higher the critical value of the construct, the greater the constraint imposed by it to achieve a specific outcome for the target value [81]. Based on bottleneck analysis, to achieve a high-level outcome, GHRM must give top priority to GT as it offers the highest constraint among all the constructs while GP must be the second priority. The constraint on this construct is much higher than GL, which is the third priority. Interestingly, to target high-level outcomes from a low level, any effort to increase green recruitment will be ineffective, because this construct is not significant according to PLS-SEM results, and there is no need to further increase its value as the critical value is constant [82].

The NCA size effect of all the constructs used for PEB reveals that GO, GS, and green values have medium size effects for highly significant values. However, the effect size of the interaction of GS and green values separately with GO on PEB is insignificant (p > 0.05). According to PLS-SEM, the results for GO, GS, and green values on pro-environmental behavior are significant, whereas the interaction of GS and green values between GO and pro-environmental behavior fails to support the hypothesis. The bottleneck analysis for pro-environmental behavior clearly indicates that none of the conditions are necessary for achieving less than 50% outcome for pro-environmental behavior. Thus, GO, GS, and green values below 50% are not necessary but are sufficient because their relevant hypotheses are supported by PLS-SEM results. To achieve the outcome of pro-environmental behavior in the range of 50–80%, certain conditions for green organizational culture, green social capital, and green values are necessary. However, all the constructs used for pro-environmental behavior are necessary conditions with different threshold values to achieve a pro-environmental behavior of 90% or more.

According to the bottleneck analysis, the increase in critical values for green values and green organizational culture on pro-environmental behavior from medium-to high-level outcomes is small, whereas the critical value for green social capital remains constant. To achieve a high-level outcome, GHRM must prioritize green values over organizational culture. Interestingly, all constructs become necessary at 90% outcome, indicating that the interaction of GS and green values between GO and pro-environmental behavior becomes operative. This implies that green social capital (similar to green values) has a moderating effect at an outcome of 90% or more. In addition, this study also points out that below 90% outcome, these interactions are neither necessary (bottleneck values not required) nor sufficient, as the relevant hypothesis are not supported by the PLS-SEM results. This discussion, in light of the results obtained by using NCA in combination with PLS-SEM, helps diagnose when GHRM activities are sufficient and when they become necessary. This combined use of techniques provides in-depth insight compared to when just NCA is used to investigate the link between high-performance HRM activities and employee performance [89].

6. Implications of the study

The study presented the implications in terms of the theoretical and practical implications. The theoretical contributions of this study are as follows. First, this study integrates the GHRM framework, AMO theory, and norm activation model into a model that can help us decipher the underlying mechanism between GHRM practices, GO, and pro-environmental behavior. Second, it contributes to the literature by providing in-depth insight into the relationship between GHRM practices and pro-environmental behavior through the mediation of GO and the moderation of GS and GV. Third, in the last decade, GHRM has emerged as a topic of debate in the field of research; yet there are limited studies aimed at understanding the underlying mechanism between GHRM and workplace pro-environmental behavior [14]. The current study contributes to the literature by providing insights into the workplace pro-environmental behavior in a developing country context, such as Pakistan, which provides new outcomes from new perspectives. Fourth, another implication of the present study is that we explored which GHRM activities correspond to the necessity or sufficiency logic to obtain specific outcomes of green organizational culture and pro-environmental behavior. Previous studies used only the PLS-SEM technique to analyze the factors that affect green organizational culture and pro-environmental behavior on average, whereas we performed additional NCA to explore the necessary conditions for achieving the required outcomes. PLS-SEM analysis indicates that the predictors of GO and pro-environmental behavior are statistically significant. Necessary condition analysis conducted after hypotheses testing provides comprehensive answers and explanations for the research questions of this study. It is a pioneering study in the field of GHRM that employs NCA and bottleneck analysis to understand the underlying mechanism in the relationship between pro-environmental behavior, GO, GS, and green values. Thus, the findings extend the scope of the literature on GHRM by confirming the link between GHRM practices and GO. Lastly, it offers the empirical confirmation for the use of NCA in conjunction with PLS-SEM to investigate sufficiency and necessity logics in social science research.

This study has numerous managerial implications for business and human resource/government policymakers. GHRM can help achieving the sustainability goals. The study identifies several green practices, such as green recruitment, green training & involvement, green performance management & compensation, and green transformational leadership, which positively influence workplace pro-environmental behavior. In the emerging economy and labor-intensive markets of Pakistan, implementing GHRM practices is imperative to alleviating environmentally detrimental effects and to motivate employees to adopt pro-environmental behavior in performing their routine tasks. Moreover, the study finds that GO has a significant positive impact on PEB. This implies that businesses in Pakistan should focus on cultivating a green organizational culture that values and promotes environmentally friendly practices. Policies and practices that encourage sustainability, resource conservation, waste reduction, and environmental responsibility should be incorporated into the company's culture. Additionally, policymakers can support and incentivize businesses to adopt green practices by providing favorable regulations, tax benefits, and financial incentives for sustainable initiatives.

Additionally, the study indicates that GS and GV have a significant positive impact on PEB. GS refers to the environmental awareness and collaboration among employees, while GV represent the shared environmental beliefs and attitudes within an organization. Businesses can harness the power of GS by encouraging teamwork, knowledge-sharing, and collective responsibility for sustainable practices. Similarly, promoting GV through internal communication and aligning company values with environmental stewardship can further drive pro-environmental behavior. Besides, to achieve the triple bottom line–people, planets, and profits–organizations should recruit employees with green values. As it is sometimes difficult to obtain candidates with deep green knowledge, companies can arrange proper training for the existing employees to improve their pro-environmental behavior. Green issues should be included in their training manuals. They should also hire capable trainers to gain full advantage of their efforts. This would only be possible with the addition of a green aspect to their strategic human resource planning. The government or its affiliated organizations in Pakistan should seriously consider including green education in their various national curricula so that green literature is integrated into the normal education syllabus and corporates get a flow of graduates with green education as their employees.

Similarly, GP was found to be a significant predictor of GO, which leads to pro-environmental behavior. Organizations should evaluate and praise the green performance of employees to encourage them to act in a green manner. To obtain even more benefits, employees should be able to join and take part in the organization's eco-friendly initiatives. This will inspire them to help the organization reach its green goals by coming up with new ways to solve problems. By pointing out the limits of the association between GHRM and green employee behaviors, this study shows how the environmental values of a potential employee should be considered during the hiring and selection process. To engage and align employees with the company's green goals, their initiative, involvement, and voluntary work should be acknowledged.

7. Conclusion, limitations and future research

This study investigated the relationship of GHRM practices on green organizational culture and pro-environmental behavior, and the moderating role of GS and pro-environmental behavior. The findings reveal that green training & involvement, green performance management & compensation, and green transformational leadership have significant positive connections with green organizational culture. Moreover, GS, green values, and green organizational culture have significant positive links with pro-environmental behavior. However, the study did not find any moderating role of green values and GS on the green organizational culture-pro-environmental behavior relationship. In addition, this study found a mediating role of green organizational culture in the relationships between green recruitment, green training & involvement, green performance management & compensation, green transformational leadership, and pro-environmental behavior. From the perspective of managerial decision-making, this study successfully demonstrates the priority order of GHRM activities that managers in the organization must adopt. The priority order can be determined from the results obtained from both the hypotheses testing and bottleneck analysis. To achieve a high-level outcome for green organizational culture, managers must give top priority to green training and involvement, followed by green performance management & compensation, and green transformational leadership. However, green recruitment holds the lowest priority.

This study has certain limitations like any other study. A quantitative technique was used for the data collection. We shall use a mixed technique for data collection in future research to obtain better insights. This research cannot be generalized, as it was conducted in a specific developing country, that is Pakistan. To generalize the results, we need to conduct research in other countries as well. A small sample size (managed from 15 organizations only) is another limitation for the generalizability of this study and future studies can apply the same research framework with a large sample size and from greater organizational coverage. This is a cross-sectional study that provides a snippet of the situation at a given point of time, therefore, common method bias issues may be aroused. Although we have taken statistical measures, further longitudinal studies should be conducted in the field of GHRM. Besides, one limitation of this research may be a social desirability bias is that it may not accurately reflect participants' true attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors, as they may provide responses that they perceive as socially desirable instead of their genuine opinions. Future research could focus on developing new methods to reduce the impact of social desirability bias on research results. For example, using anonymous surveys or employing indirect questioning techniques may encourage participants to provide more honest responses. To understand the mechanism underlying GHRM and pro-environmental behavior, the interactions between green innovation, green creativity, and green work climate perceptions can be investigated.

Authors contribution

Jawaria Ahmad, Zafir Khan Mohamed Makhbul and Khairul Anuar Mohd Ali: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper. Abdullah Al Mamun and Mohammad Masukujjaman: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and give their consent for submission and publication.

8. Availability of data and materials

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19134.

Appendix A. Loading, Cross-Loading

| GR | GT | GP | GL | GS | GV | GO | PEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR1 | 0.761 | 0.444 | 0.381 | 0.343 | 0.363 | 0.228 | 0.228 | 0.341 |

| GR2 | 0.815 | 0.424 | 0.485 | 0.377 | 0.354 | 0.259 | 0.307 | 0.316 |

| GR3 | 0.748 | 0.385 | 0.517 | 0.239 | 0.381 | 0.145 | 0.303 | 0.296 |

| GR4 | 0.689 | 0.432 | 0.496 | 0.469 | 0.321 | 0.337 | 0.270 | 0.309 |

| GT1 | 0.468 | 0.783 | 0.425 | 0.550 | 0.522 | 0.521 | 0.408 | 0.415 |

| GT2 | 0.360 | 0.748 | 0.416 | 0.484 | 0.446 | 0.399 | 0.401 | 0.333 |

| GT4 | 0.423 | 0.767 | 0.511 | 0.490 | 0.478 | 0.385 | 0.461 | 0.348 |

| GT5 | 0.462 | 0.791 | 0.496 | 0.399 | 0.481 | 0.375 | 0.461 | 0.350 |

| GP1 | 0.517 | 0.509 | 0.784 | 0.510 | 0.436 | 0.400 | 0.501 | 0.418 |

| GP2 | 0.459 | 0.354 | 0.710 | 0.253 | 0.450 | 0.257 | 0.397 | 0.293 |

| GP3 | 0.447 | 0.442 | 0.695 | 0.423 | 0.429 | 0.252 | 0.458 | 0.304 |

| GP4 | 0.409 | 0.434 | 0.736 | 0.331 | 0.338 | 0.245 | 0.422 | 0.302 |

| GP5 | 0.408 | 0.391 | 0.638 | 0.424 | 0.347 | 0.247 | 0.376 | 0.282 |

| GL1 | 0.405 | 0.470 | 0.465 | 0.791 | 0.497 | 0.459 | 0.509 | 0.378 |

| GL2 | 0.417 | 0.517 | 0.445 | 0.813 | 0.510 | 0.518 | 0.466 | 0.433 |

| GL3 | 0.353 | 0.508 | 0.453 | 0.839 | 0.496 | 0.537 | 0.459 | 0.431 |

| GL4 | 0.291 | 0.466 | 0.361 | 0.710 | 0.424 | 0.549 | 0.335 | 0.455 |

| GS1 | 0.415 | 0.550 | 0.427 | 0.544 | 0.748 | 0.468 | 0.531 | 0.387 |

| GS2 | 0.342 | 0.549 | 0.424 | 0.547 | 0.842 | 0.507 | 0.572 | 0.485 |

| GS3 | 0.361 | 0.476 | 0.434 | 0.443 | 0.815 | 0.378 | 0.493 | 0.439 |

| GS4 | 0.374 | 0.379 | 0.488 | 0.387 | 0.731 | 0.315 | 0.558 | 0.396 |

| GV1 | 0.268 | 0.495 | 0.354 | 0.555 | 0.457 | 0.843 | 0.481 | 0.629 |

| GV2 | 0.204 | 0.345 | 0.324 | 0.456 | 0.435 | 0.745 | 0.439 | 0.487 |

| GV3 | 0.225 | 0.358 | 0.272 | 0.475 | 0.381 | 0.765 | 0.401 | 0.437 |

| GV4 | 0.293 | 0.469 | 0.287 | 0.522 | 0.391 | 0.772 | 0.452 | 0.520 |

| GO3 | 0.301 | 0.409 | 0.476 | 0.361 | 0.519 | 0.440 | 0.738 | 0.427 |

| GO4 | 0.318 | 0.416 | 0.459 | 0.512 | 0.548 | 0.458 | 0.773 | 0.488 |

| GO5 | 0.249 | 0.402 | 0.461 | 0.354 | 0.483 | 0.413 | 0.752 | 0.363 |

| GO6 | 0.243 | 0.464 | 0.431 | 0.470 | 0.503 | 0.395 | 0.743 | 0.358 |

| PEB1 | 0.320 | 0.419 | 0.364 | 0.461 | 0.429 | 0.586 | 0.481 | 0.808 |

| PEB2 | 0.232 | 0.353 | 0.245 | 0.415 | 0.344 | 0.519 | 0.312 | 0.756 |

| PEB3 | 0.239 | 0.199 | 0.249 | 0.212 | 0.348 | 0.287 | 0.331 | 0.581 |

| PEB6 | 0.385 | 0.320 | 0.416 | 0.375 | 0.436 | 0.469 | 0.422 | 0.683 |

Note: GR - Green Recruitment, GT - Green Training & Involvement, GP - Green Performance Management & Compensation, GL - Green Transformational Leadership, GO - Green Organizational Culture, GS - Green Social Capital, GV - Green Values, PEB - Workplace Pro-Environmental Behaviour.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) Pakistan Floods. 2022 https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disasters/2022-pakistan-floods/ available on 9/1/2022 at: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vázquez-Brust D., Jabbour C.J.C., Plaza-Úbeda J.A., Perez-Valls M., de Sousa Jabbour A.B.L., Renwick D.W.S. Business Strategy and the Environment; 2022. The Role of Green Human Resource Management in the Translation of Greening Pressures into Environmental Protection Practices; pp. 1–21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang G., Chen Y., Jiang Y., Paillé P., Jia J. Green human resource management practices: scale development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018;56(1):31–55. doi: 10.1111/1744-7941.12147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabbour C.J.C., Sarkis J., Jabbour, A. B. L. de S. Renwick D.W.S., Singh S.K., Grebinevych O., Kruglianskas I., Filho M.G. Who is in charge? A review and a research agenda on the ‘human side’ of the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;222:793–801. https://www.academia.edu/47912253/Who_is_in_charge_A_review_and_a_research_agenda_on_the_human_side_of_the_circular_economy [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pellegrini C., Rizzi F., Frey M. The role of sustainable human resource practices in influencing employee behavior for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018;27(8):1221–1232. doi: 10.1002/bse.2064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renwick D.W.S., Redman T., Maguire S. Green human resource management: a review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00328.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang L., Guo Z., Deng B., Wang B. Unlocking the relationship between environmentally specific transformational leadership and employees' green behaviour: a cultural self-representation perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022 doi: 10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2022.134857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoaib M., Nawal A., Zámečník R., Korsakienė R., Rehman A.U. Go green! Measuring the factors that influence sustainable performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;366 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeşiltaş M., Gürlek M., Kenar G. Organizational green culture and green employee behavior: differences between green and non-green hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;343 doi: 10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2022.131051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francoeur V., Paillé P., Yuriev A., Boiral O. The measurement of green workplace behaviors: a systematic review. Organ. Environ. 2021;34(1):18–42. doi: 10.1177/1086026619837125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad N., Ullah Z., Arshad M.Z., Kamran H., waqas, Scholz M., Han H. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: the mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021;27:1138–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2021.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fawehinmi O., Yusliza M.-Y., Farooq K. Green human resource management and employee green behavior. Trends, Issues, Challenges and the Way Forward. 2022:167–201. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-06558-3_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan C., Abbas J., Álvarez-Otero S., Khan H., Cai C. Interplay between corporate social responsibility and organizational green culture and their role in employees' responsible behavior towards the environment and society. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;366 doi: 10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2022.132878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saeed B. Bin, Afsar B., Hafeez S., Khan I., Tahir M., Afridi M.A. Promoting employee's proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019;26(2):424–438. doi: 10.1002/csr.1694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Ghazali B.M., Afsar B. Retracted: green human resource management and employees' green creativity: the roles of green behavioral intention and individual green values. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021;28(1) doi: 10.1002/CSR.1987. 536–536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Úbeda-García M., Marco-Lajara B., Zaragoza-Sáez P.C., Manresa-Marhuenda E., Poveda-Pareja E. Green ambidexterity and environmental performance: the role of green human resources. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022;29(1):32–45. doi: 10.1002/csr.2171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumont J., Shen J., Deng X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: the role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017;56(4):613–627. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amini M., Bienstock C.C., Narcum J.A. Status of corporate sustainability: a content analysis of Fortune 500 companies. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018;27(8):1450–1461. doi: 10.1002/bse.2195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrukh M., Ansari N., Raza A., Wu Y., Wang H. Fostering employee's pro-environmental behavior through green transformational leadership, green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2022;179 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirza M. 2016. The Evolving Landscape in about ACCA; pp. 1–38.https://www.accaglobal.com/gb/en/technical-activities/technical-resources-search.c-topic--Sustainability.r-geographicLocation--Asia_Pacific__Pakistan.html [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roscoe S., Subramanian N., Jabbour C.J.C., Chong T. Green human resource management and the enablers of green organisational culture: enhancing a firm's environmental performance for sustainable development. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019;28(5):737–749. doi: 10.1002/bse.2277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Swidi A.K., Gelaidan H., Saleh R.M. The joint impact of green human resource management, leadership and organizational culture on employees' green behaviour and organisational environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;316(May) doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie X., Hoang T.T., Zhu Q. Green process innovation and financial performance: the role of green social capital and customers' tacit green needs. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2022;7(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2022.100165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Islam T., Khan M.M., Ahmed I., Mahmood K. Promoting in-role and extra-role green behavior through ethical leadership: mediating role of green HRM and moderating role of individual green values. Int. J. Manpow. 2021;42(6):1102–1123. doi: 10.1108/IJM-01-2020-0036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooke F.L., Schuler R., Varma A. Human resource management research and practice in Asia: past, present and future. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020;30(4) doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2020.100778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichniowski C., Kochan T.A., Levine D., Olson C., Strauss G. What works at work: overview and assessment. Ind. Relat.: A Journal of Economy and Society. 1996;35(3):299–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-232X.1996.tb00409.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrell-Cook G., Appelbaum E., Bailey T., Berg P., Kalleberg A.L. Manufacturing advantage: why high-performance work systems pay off. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001;26(3):459. doi: 10.2307/259189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marin-Garcia J.A., Tomas J.M. Deconstructing AMO framework: a systematic review. Intang. Cap. 2016;12(4):1040–1087. doi: 10.3926/ic.838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abualigah A., Koburtay T., Bourini I., Badar K., Gerged A.M. 2022. Towards Sustainable Development in the Hospitality Sector: Does Green Human Resource Management Stimulate Green Creativity? A Moderated Mediation Model. Business Strategy And the Environment; pp. 1–16. June. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stern P.C., Dietz T., Abel T., Guagnano G.A., Kalof L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: the case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999;6(2):81–97. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=hcop_facpubs [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977;10(C):221–279. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60358-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992;25(C):1–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunlap R.E., Van Liere K.D., Mertig A.G., Jones R.E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: a revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues. 2000;56(3):425–442. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersson L., Shivarajan S., Blau G. Enacting ecological sustainability in the MNC: a test of an adapted value-belief-norm framework. J. Bus. Ethics. 2005;59(3):295–305. doi: 10.1007/s10551-005-3440-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou C.J. Hotels' environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: interactions and outcomes. Tourism Manag. 2014;40:436–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naveed R.T., Alhaidan H., Al Halbusi H., Al-Swidi A.K. Do organizations really evolve? The critical link between organizational culture and organizational innovation toward organizational effectiveness: pivotal role of organizational resistance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2022;7(2) doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2022.100178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holt D., Anthony S. Exploring ?Green? culture in nortel and middlesex university. Eco-Management Auditing. 2000;7(3):143–154. doi: 10.1002/1099-0925(200009)7:3%3C143::AID-EMA132%3E3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassani A., Mosconi E. Social media analytics, competitive intelligence, and dynamic capabilities in manufacturing SMEs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2022;175 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galpin T., Whittington J.L., Bell G. Is your sustainability strategy sustainable? Creating a culture of sustainability. Corp. Govern. 2015;15(1):1–17. doi: 10.1108/CG-01-2013-0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu D., Ainsworth S.E., Baumeister R.F. A meta-analysis of social networking online and social capital. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2016;20(4):369–391. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hadjri M.I., Perizade B., Farla W. Green human resource management, green organizational culture, and environmental performance. An empirical study. In 2019 International Conference on Organizational Innovation (ICOI 2019) 2019, October:138–143. https://www.atlantis-press.com/article/125919303.pdf Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Ghazali B.M., Gelaidan H.M., Shah S.H.A., Amjad R. Green transformational leadership and green creativity? The mediating role of green thinking and green organizational identity in SMEs. Front. Psychol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.977998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paillé P., Valéau P., Renwick D.W. Leveraging GHRM to achieve environmental sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;260 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abbas J., Khan S.M. Green knowledge management and organizational green culture: an interaction for organizational green innovation and green performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022 doi: 10.1108/JKM-03-2022-0156/FULL/XML. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2015;43(1):115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imran M., Jingzu G. Green organizational culture, organizational performance, green innovation, environmental performance: a mediation-moderation model. J. Asia Pac. Bus. 2022:161–182. doi: 10.1080/10599231.2022.2072493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ababneh O.M.A. How do green HRM practices affect employees' green behaviors? The role of employee engagement and personality attributes. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2021;64(7):1204–1226. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2020.1814708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang S., Abbas J., Sial M.S., Álvarez-Otero S., Cioca L.I. Achieving green innovation and sustainable development goals through green knowledge management: moderating role of organizational green culture. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2022;7(4) doi: 10.1016/J.JIK.2022.100272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]