Abstract

The infarcted heart undergoes irreversible pathological remodeling after reperfusion involving left ventricle dilation and excessive inflammatory reactions in the infarcted heart, frequently leading to fatal functional damage. Extensive attempts have been made to attenuate pathological remodeling in infarcted hearts using cardiac patches and anti-inflammatory drug delivery. In this study, we developed a paintable and adhesive hydrogel patch using dextran-aldehyde (dex-ald) and gelatin, incorporating the anti-inflammatory protein, ANGPTL4, into the hydrogel for sustained release directly to the infarcted heart to alleviate inflammation. We optimized the material composition, including polymer concentration and molecular weight, to achieve a paintable, adhesive hydrogel using 10% gelatin and 5% dex-ald, which displayed in-situ gel formation within 135 s, cardiac tissue-like modulus (40.5 kPa), suitable tissue adhesiveness (4.3 kPa), and excellent mechanical stability. ANGPTL4 was continuously released from the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel without substantial burst release. The gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel could be conveniently painted onto the beating heart and degraded in vivo. Moreover, in vivo studies using animal models of acute myocardial infarction revealed that our hydrogel cardiac patch containing ANGPTL4 significantly improved heart tissue repair, evaluated by echocardiography and histological evaluation. The heart tissues treated with ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel patches exhibited increased vascularization, reduced inflammatory macrophages, and structural maturation of cardiac cells. Our novel hydrogel system, which allows for facile paintability, appropriate tissue adhesiveness, and sustained release of anti-inflammatory drugs, will serve as an effective platform for the repair of various tissues, including heart, muscle, and cartilage.

Keywords: Cardiac patch, Hydrogel, Angiopoietin-like 4, Myocardial infarction

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A paintable and adhesive hydrogel patch was developed using dextran-aldehyde (dex-ald) and gelatin.

-

•

The gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel exhibits biodegradability, tissue adhesiveness, and cardiac tissue-like elasticity.

-

•

The gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel with the anti-inflammatory protein, ANGPTL4, continuously released to the infarcted heart.

-

•

The drug-loaded hydrogel cardiac patch significantly improved heart regeneration.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases cause over 17.9 million deaths per year worldwide [1,2]. Ischemic heart disease, represented by myocardial infarction (MI), is a major cause of cardiovascular disease-related deaths [1]. MI is primarily caused by blockage of blood flow and oxygen to the heart muscle as a consequence of atheromatous plaque rupture and thrombus formation in the coronary artery [3]. MI reperfusion leads to a series of events in cardiac tissues, including inflammation and irreversible remodeling [4]. Severe inflammation occurs immediately after MI and causes massive cell death and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation [5], subsequently inducing the deposition of dense fibrotic collagen fibers in the infarcted tissue and structural remodeling of the infarcted heart, such as ventricular wall thinning, chamber dilatation, and tissue stiffening [6,7]. This pathological remodeling negatively affects cardiac function, resulting in cardiac contractile dysfunction, and frequently leads to heart failure. Heart transplantation is currently the most feasible and fundamental treatment for cardiac repair after MI; however, there are several critical issues, such as the limited number of donors and the risk of infection [8], necessitating the development of novel and more efficient MI therapies.

Accordingly, various biomaterial-based approaches have been extensively explored to mitigate pathological remodeling of infarcted hearts and encourage heart repair [[9], [10], [11]]. In particular, several cardiac patches have been applied to support the mechanical functions of infarcted hearts by reducing excessive dilation [12]. The material properties essential for functional cardiac patches were suggested to include heart tissue-like elasticity, biodegradation, ease of application, and adhesiveness [12,13]. Hydrogels are structurally and mechanically similar to cardiac tissues, and can be used as biomimetic materials for heart repair. In addition, the adhesiveness of cardiac patches enables their direct fixation onto the epicardium without surgical sutures, staples, or light irradiation [14,15]. Hence, several adhesive hydrogels have been developed for cardiac applications in the form of paintable gels [13], lyophilized tapes [16,17], and sprayable gels [18] for various tissue engineering applications. However, most adhesive hydrogels are produced using chemical crosslinker and/or non-biodegradable synthetic polymers, raising concerns about their biocompatibility and practical use. Therefore, the development of a biocompatible and adhesive hydrogel cardiac patch for cardiac repair remains challenging.

Concurrently, because excessive inflammation in the left ventricle (LV) of the infarcted heart induces pathological remodeling [19], various therapeutic substances and cells have been delivered to relieve excessive inflammation in the infarcted heart and promote heart repair. Angiopoietin-like protein 4 (ANGPTL4) was recently discovered to be a potent anti-inflammatory protein that inhibits the activation of inflammatory macrophages. ANGPTL4 apparently regulates macrophage phenotypes toward anti-inflammatory and also induce angiogenesis through interaction with integrin on endothelial cells [20,21]. Cho et al. demonstrated that intraperitoneal injection of ANGPTL4 efficiently alleviated inflammation in infarcted hearts and induced heart repair [22]. In addition, ANGPTL4 can promote endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis [20,22]. However, sustained release and delivery of ANGPTL4 to the infarcted heart is necessary to efficiently and safely modulate tissue reactions post MI.

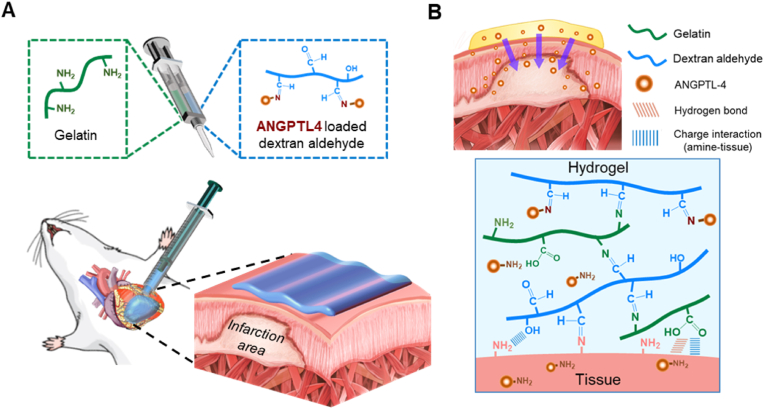

In this study, we devised a paintable and adhesive hydrogel with sustained release of ANGPTL4 as a multifunctional cardiac patch for efficient heart repair after MI. Specifically, biocompatible natural polymers (gelatin and dextran-aldehyde (dex-ald)) were formulated to spontaneously form a gel for painting and tissue adhesion. Gelatin and dex–ald react via the Schiff base reaction of the aldehyde group of the oxidized dextran and the amine group of the gelatin upon mixing. Non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interaction) and Schiff base formation between gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels and tissues further allow strong adhesion of the gel to cardiac tissue. Several previous studies demonstrated that hydrogels based on gelatin and dex-ald were useful for various biomedical applications, such as wound dressing [23], neural repair [24], and cartilage tissue engineering [25]. In particular, Zhu et al. reported that myocardial injection of gelatin/dex-ald could induce tissue repair [26]. However, in situ forming gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels as cardiac patches that can be painted onto directly heart tissue with high stability and drug releasing capability have not been demonstrated yet. We elaborated to optimize the compositions (concentrations and molecular weights) of the prepolymers to achieve an in situ forming paintable hydrogel cardiac patch. In addition, local sustained release of ANGPTL4 from the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel to the epicardium can be achieved based on the dissociation of the reversible Schiff base of ANGPTL4 in the hydrogel.

Altogether, our adhesive hydrogel cardiac patch (ANGPTL4-loaded gelatin/dex-ald) should effectively alleviate pathological remodeling (e.g., LV wall thinning and chamber dilation) by providing mechanical support to the LV and induce heart repair by suppressing excessive inflammation via the sustained release of anti-inflammatory ANGPTL4 at the epicardium.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Gelatin from porcine skin (type A), dextran from Leuconostoc mesenteroides (average mol. wt. 150,000 Da and 1,500,000–2,800,000 Da), dextran from Leuconostoc spp. (average mol. wt. 450,000–650,000 Da), sodium periodate (NaIO4), ethylene glycol, hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH2OH·HCl), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), sodium azide (NaN3), glycine, sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium chloride (KCl), potassium phosphate monobasic (KH2PO4), D-(+)-glucose, sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4), and pancreatin from porcine pancreas were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Collagenase type 2 was purchased from the Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ, USA). Rat ANGPTL4 was purchased from Abbexa, Ltd. (Cambridge, UK). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) were purchased from Hyclone (Logan, UT, USA). Horse serum, medium M199, MEM-alpha, antibiotic-antimycotic (100 × ; penicillin 10000 units/mL, streptomycin 10000 μg/mL, amphotericin 25 μg/mL), trypsin/EDTA (0.05%), Live/Dead® viability/cytotoxicity kits for mammalian cells, and 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBSA) 5% w/v solution were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). The anti-sarcomeric alpha actinin mouse monoclonal antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). An anti-connexin-43 rabbit monoclonal antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Percoll was purchased from GE Healthcare (Madison, WI, USA). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) Cytotoxicity Detection Kit was purchased from Takara Shuzo Co. (Otsu, Shiga, Japan).

2.2. Preparation of paintable hydrogel

2.2.1. Synthesis of dex-ald

Dextran-aldehyde (dex-ald) was synthesized by the oxidation of dextran as previously described [24]. Briefly, dextran (5 g) was dissolved in deionized water (500 mL). NaIO4 (2.673 g) was dissolved in deionized water (20 mL), and NaIO4 solution was added dropwise to the dextran solution with vigorous stirring. The mixture was incubated with stirring at 25 °C in the dark for 2 h. To stop the reaction, ethylene glycol (0.695 mL) was added and the mixture was incubated with stirring for an additional 1 h. The solution was dialyzed in deionized water using a dialysis membrane (3500 kDa MWCO) for 3 days and lyophilized. The aldehyde group in dex-ald was determined using a hydroxylamine hydrochloride titration assay [24]. Briefly, dex-ald (0.1 g) was dissolved in 0.025 M NH2OH·HCl solution (10 mL) for 1 h with stirring. Then, the dex-ald solution was titrated against 0.1 M NaOH.

2.2.2. Quantification of amine group in gelatin

The amine group in gelatin was quantified using a TNBSA solution according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, gelatin solution (20 μg/mL) was prepared in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate (pH 8.5). Glycine solutions of various concentrations (20–0.625 μg/mL) were prepared as standard solutions. Then, 0.01% TNBSA solution was added to 0.5 mL of sample solution or standard solutions. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h, followed by addition of 10% SDS (0.25 mL) and 1 N HCl (0.125 mL). The absorbance of each solution was measured at 335 nm using a UV/vis spectrometer (Touch Duo; Biodrop, Cambridge, UK).

2.2.3. Gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel formation

First, 10% (wt) dex-ald solution and 20% (wt) gelatin solution were separately prepared in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 37 °C. The dex-ald and gelatin solutions were transferred to individual barrels in a dual syringe equipped with a static mixing needle (Nordson EFD, OH, USA). The precursor solutions were injected with in-situ mixing and further incubated at 37 °C for gelation.

2.3. Characterization of gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels

2.3.1. Mechanical properties

The mechanical properties of the hydrogels were examined using an oscillatory rheometer (Kinexus; Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK). For the time-sweep test, shear moduli were measured at a frequency of 1 Hz and a strain of 0.5% at 37 °C for 30 min. The gelation time of the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel was determined as the time point at which the shear elastic modulus (G′) was greater than the shear viscous modulus (G″). For the frequency-sweep test, shear moduli were measured in a frequency range of 0.1–10 Hz with 0.5% strain at 37 °C. Young's modulus was calculated from the shear elastic modulus obtained at a frequency of 1 Hz [27].

2.3.2. Microscopic structures

The internal microstructure of the paintable hydrogel was investigated using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM-7500F, Jeol, Tokyo, Japan). The hydrogel samples were freeze-dried and cut to examine the cross-sections. The freeze-dried hydrogels were coated with platinum using a sputter (Cressington 108 auto, Cressington Scientific Instruments Ltd., Watford, UK) prior to SEM measurements.

2.3.3. Adhesion test

The lap-shear stress of the paintable hydrogel was measured using a universal test machine (TO-100-IC, Testone, Gyeonggi, Republic of Korea) to investigate the adhesion strength of the hydrogel to the tissue. The lap shear stress was calculated by dividing the maximum stress by the contact area between the hydrogel and tissue. For adhesion tests, porcine epicardium or skin tissue was cut into rectangular pieces (4.0 cm × 1.5 cm) with 0.2 cm of thickness. A precursor solution of the hydrogel was mixed, placed between two tissue pieces, and further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The gel-tissue contact area was adjusted to be 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm. For tensile tests, the ends of the tissue samples were fixed to individual clamps and stretched with a 10 kN load cell at 2 mm/min of a tensile rate. The hydrogel-loaded tissue samples were stretched to a distance of 4 mm at a rate of 60 mm/min, which was repeated 50 times. Hydrogel-tissue adhesion was investigated under dynamic conditions. The hydrogel was loaded onto a porcine epicardium tissue by injecting precursor solutions using a dual syringe and incubating for 10 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, the adhesion of the hydrogel-loaded tissue was examined with various deformations (e.g., twisting and bending) and water flushing.

2.4. Preparation and characterization of the ANGPTL4-loaded gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel

2.4.1. Preparation of ANGPTL4-loaded gelatin/dex-ald gel (A4/gelatin/dex-ald)

ANGPTL4 was mixed with 10% (wt) dex-ald at a concentration of 60 μg/mL and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The ANGPTL4-containing dex-ald solution was further mixed with 20% gelatin solution using dual syringe, as previously described. For visualization, a trace amount (∼2 μL/mL) of purple food dye (Wilton Industries, Inc., IL, USA) was pre-mixed with a gelatin solution prior to injection.

2.4.2. ANGPTL4 release tests

The release profile of ANGPTL4 from ANGPTL4-loaded gelatin/dex-ald (A4/gelatin/dex-ald) hydrogel was investigated using fluorescence dye-conjugated ANGPTL4. Cy5-conjugated ANGPTL4 (Cy5-ANGPTL4) was synthesized using a Cy5-conjugation kit (ab188288; Cambridge, MA, USA). The Cy5-ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel was prepared to be disc-shaped (0.5 mm thickness and 8 mm in a diameter). As control, a gelatin hydrogel, not containing dex-ald, was prepared by crosslinking gelatin (10%) with glutaraldehyde (0.87%). Note that 0.87% glutaraldehyde contained the same amount of aldehyde group as the dex-ald used for the preparation of gelatin/dex-ald. ANGPLT4 was loaded into the gelatin hydrogel. Each sample was incubated in 2 mL of the release buffer (5 mM phosphate, 0.5% BSA, and 0.01% NaN3 in 1x saline) at pH 5.8 or 7.4 in a shaking incubator (37 °C, 60 rpm). The fluorescence intensity of each sample solution was measured over 14 days using a microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.5. In vitro cell studies

2.5.1. Primary cardiomyocytes isolation and culture

Primary cardiomyocytes (CMs) were isolated from two-day-old neonatal rats as previously described [28,29]. First, the ADS buffer was prepared as follows; NaCl 6.8 g, HEPES 4.76 g, NaH2PO4 0.12 g, d-glucose 1.0 g, KCl 0.4 g, MgSO4 0.1 g in 1 L of distilled water. Heart tissues from 30 neonatal rats were isolated, washed using 1X ADS, and finely chopped with scissors. The chopped tissues were incubated in an enzyme solution (collagenase 0.0243 g and pancreatin 0.05 g in 50 mL ADS buffer) in a shaking incubator (37 °C, 60 rpm) for 2 h. A percoll solution was prepared by mixing percoll stock (45 mL) and 10X ADS (5 mL). The percoll solutions (top and bottom solutions) were separately prepared: top (21.6 mL of percoll solution and 26.4 mL of 1X ADS) and bottom 23.4 mL of percoll solution and 12.6 mL of 1X ADS). The digested heart tissues were resuspended in 1X ADS and transferred to the percoll gradient solution. After centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 30 min, the rounded strip on the percoll gradient was collected and incubated in tissue culture plates in CM growth medium (340 mL DMEM, 85 mL M199, 5 mL antibiotic-antimycotic (100 × ), 25 mL FBS, and 50 mL horse serum) for 1.5 h. Then, the floating cells (CMs) were collected and used for subsequent studies.

2.5.2. Cytocompatibility test

The cytocompatibility of the hydrogels was investigated using in vitro CM culture in direct and indirect contact modes. Disc-shaped hydrogels of 0.5 mm thickness and 8 mm diameter were prepared and sterilized by incubation in 70% ethanol and UV exposure for 30 min, followed by washing with sterile DPBS. The hydrogels were then incubated overnight in CM growth medium. For direct contact culture mode, the CMs were seeded on each hydrogel at a cell density of 2.0 × 105 cells and incubated for 2 h. Then, the medium was exchanged with fresh growth medium. For indirect culture with hydrogel, CMs were seeded at a density of 2.0 × 105 cells/well onto 24 well plates and incubated for 2 h. Fresh growth medium was carefully added and incubated for an additional 24 h. Each hydrogel was placed on the upper part of a Transwell insert, which was then placed on the well plate. CMs were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and growth medium was changed every day.

The LDH assay and live/dead cell staining were conducted for cytocompatibility tests according to the manufacturers’ instructions. For the LDH assay, CMs were cultured on each sample for one day, and the culture medium was collected. The growth medium of CMs cultured on a tissue culture plate (TCP) was used as a low control (live CMs). CMs cultured on TCP were treated with medium containing 2% Triton X-100 and the medium was collected and used as a high control (dead CMs). The culture medium was mixed with the assay reagent (1:1 ratio) and incubated for 30 min at 25 °C. The absorbance of each mixture was measured at 490 nm on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 of incubation. The cell viability was calculated using the following equation:

For live/dead cell staining, the assay solution was prepared by adding 2 μL of 2 mM EthD-1 and 0.5 μL of 5 mM calcein AM to 1 mL DPBS. The cell culture medium was removed, and the assay solution was added. After 10 min of incubation, samples were washed twice with DPBS for 5 min. Live (green)/dead (red) staining images were acquired on days 3 and 7 using a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI 3000 B). Calcein AM-positive areas per image were calculated to estimate live cells using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) using the following equation:

2.5.3. Immunofluorescence staining

To investigate the maturation of CMs on a hydrogel sample, immunofluorescence staining was performed after 7 days of incubation. The samples were washed with DPBS twice, fixed with 3.74% paraformaldehyde at 25 °C for 20 min, and washed with DPBS. The samples were permeabilized by incubation in 0.1% Triton X-100 solution (in DPBS) at 25 °C for 20 min and washed with DPBS. The samples were then blocked by incubation in a blocking solution (3% BSA and 3% goat serum in DPBS) at 25 °C for 1 h. Next, the samples were incubated in antibody solution (anti-sarcomeric alpha actinin mouse monoclonal antibody and anti-connexin-43 rabbit monoclonal antibody, 1:50 dilution in blocking solution) at 4 °C overnight and washed twice by incubation in DPBS for 30 min per wash. Then, the samples were incubated in the secondary antibody solution (Alexa fluor® 555 goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa fluor® 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:200 dilution in the blocking solution) at 25 °C for 1.5 h. Samples were carefully washed with DPBS, incubated in DAPI solution (1: 1000 dilution in blocking solution) at 25 °C for 3 min, and washed with DPBS. Fluorescence images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope.

2.6. In vivo studies

2.6.1. Establishment of MI model and treatment of a paintable hydrogel

The study was reviewed and approved by the Chonnam National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (study approval code: CNUHIACUC-22013), and all experiments were performed after approval by a local ethical committee at Chonnam National University Medical School. Eight-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (weight 200–230 g) were purchased from Orient Bio Inc. (Seoul, Korea). The rats were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg), intubated, and mechanically ventilated. The proximal left anterior descending coronary artery was ligated, and a hydrogel patch was painted on the epicardium of the infarcted zone. The heart was then repositioned in the chest and the chest was closed. The rats were kept in a supervised setting until they became fully conscious. The experimental groups were as follows: sham, MI, MI with gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel patch, and MI with A4/gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel patch.

2.6.2. Echocardiographic analysis

LV function was evaluated using echocardiography two weeks after MI and patch treatment. To exclude bias, an expert who was not aware of the experimental conditions performed echocardiographic evaluations using a 15-MHz linear array transducer system (iE33 system, Philips Medical Systems, Tampa, FL, USA). Two-dimensional imaging was performed to obtain M-mode parameters in the short-axis view to measure the LV cavity dimensions and systolic function. The percent change in LV dimension (fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF)) was calculated using the following equation:

where LVEDD is the left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, LVESD is the left ventricular end-systolic diameter, EDV is the LV volume at end-diastole, and ESV is the LV volume at end-systole.

2.6.3. Histological analysis

On the 14th day after MI, cardiac tissue was quickly removed, formalin-fixed, and embedded in paraffin blocks for histological studies. Cardiac fibrosis was assessed using Masson's trichrome staining (ab150686; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and fibrotic regions were assessed using the NIS-Elements Advanced Research tool to visualize blue-stained fibrosis deposits (Nikon, Japan). The percentage of fibrosis was assessed as the blue fibrotic area divided by the total LV area. For immunohistochemical analysis, slides were pretreated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 10 min at room temperature to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity. Then, the slides were incubated in blocking solution (5% normal goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich, NS02L) in DPBS for 1 h and treated with the primary antibody at 4 °C. The antibodies included von Willebrand factor (vWF, F3520, Sigma-Aldrich), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, A2547, Sigma-Aldrich), CD68 (T3003, MBA Biomedicals, Augst, Switzerland), or CD206 (ab64693, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The sections were then treated with Alexa Fluor 488 (A11034, Molecular Probes) or 594 (A11037, Molecular Probes) secondary antibodies. After washing, the mounting material (VECTASHIELD® Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI, H-1200-10, Vector Labs Inc., Malvern, PA, USA) was added to the slides, and fluorescent cells were visualized with an Eclipse Ti2 microscope (Nikon, Japan).

2.6.4. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of blood samples

Two weeks after MI and patch treatment, blood samples were collected and transferred to EDTA tubes. The blood samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 25 °C, and plasma was stored at −80 °C until assay. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in plasma were quantified using ELISA kits (BMS622 and BMS625, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, unless specified otherwise. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc comparison of means using Origin Pro 2021 software at a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Design and preparation of paintable hydrogel

We used gelatin and dextran as basal hydrogel materials because of their inherent adhesiveness and biocompatibility [[30], [31], [32]]. We further modified dextran to dex-ald, which can spontaneously react with gelatin and cardiac tissue via Schiff reaction to produce a covalent hydrogel network and strong adhesive bonds with the epicardium, respectively. This spontaneous reaction upon mixing allowed the hydrogel to be paintable on the LV epicardium (Fig. 1). Appropriate reaction kinetics of in situ gelation are critical for obtaining a paintable hydrogel cardiac patch. When in-situ gelation on the epicardium occurs too slowly, the precursor solution may flow away from the heart prior to gelation, resulting in an incomplete hydrogel on the heart. On the other hand, gelation that is too fast may cause uncontrollable and non-uniform coverage of the hydrogel on the epicardium and insufficient adhesion to the tissue. Therefore, we attempted to achieve optimal gelation time by investigating various factors such as precursor concentration and molecular weight. First, we explored the effect of dex-ald and gelatin composition on gelation. The amine degree in gelatin and the aldehyde degree in dex-ald were 0.26 and 3.48 mmol/g, respectively (Fig. S1). With a constant content of gelatin (10%), concentrations of dex-ald were varied from 1% to 5%, with an excess of amine groups compared to aldehyde groups. Higher dex-ald content in the mixture resulted in a faster increase in the elastic modulus and thereby a shorter gelation time. Moreover, gel/dex-ald hydrogels containing more dex-ald had higher moduli (Fig. 2A and B). These results imply that the aldehyde groups densely present in the dex–ald chain (0.58 aldehyde groups in a glucose unit) have limited accessibility and reactivity with amine groups in gelatin to form Schiff base bonds, requiring larger aldehyde contents for network formation than the amine groups. Variation in gelatin content from 2.5% to 10% with a constant dex-ald content (5%) did not substantially affect the gelation time (Fig. 2C and D). However, the elastic modulus of gelatin/dex-ald increased as the gelatin content.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representations of an adhesive paintable hydrogel. (A) Schematic illustration of a paintable hydrogel consisting of dextran-aldehyde and gelatin for the treatment of infarcted hearts. (B) Schematic illustration of sustained release of ANGPTL4 from a paintable hydrogel on epicardium to infarcted myocardium.

Fig. 2.

Preparation and characterization of the paintable gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels. (A) Time-dependent shear moduli of various hydrogels prepared with 10% gelatin and different concentrations of dex-ald. G′ and G″ indicate a viscous component and an elastic component of the modulus, respectively. (B) Gelation times and shear moduli (G′) of the hydrogels from (A). *p < 0.05 compared to 1% of dex-ald. #p < 0.05 compared to 2.5% of dex-ald. (C) Time-dependent shear moduli of various hydrogels prepared with 5% dex-ald and different concentrations of gelatin. (D) Gelation times and shear moduli (G′) of the hydrogels from (C). *p < 0.05 compared to 2.5% of gelatin. #p < 0.05 compared to 5% of gelatin. (E) Time-dependent shear moduli of various hydrogels prepared with 10% gelatin and 5% dex-ald prepared from different MWs of dextran (150 kDa, 500 kDa, and 1.5 MDa). (F) Gelation times of the hydrogels from (E). (G) Frequency sweep of various hydrogels prepared with 10% gelatin and 5% dex-ald prepared from dextran of different MWs (150 kDa, 500 kDa, and 1.5 MDa). (H) Shear elastic moduli of the hydrogels at 1 Hz after swelling in saline for 24 h. (I) Photographs for the hydrogel prepared with 10% gelatin and 5% dex-ald (produced from 500 kDa dextran). (J) Scanning electron micrographs of the hydrogel. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). *p < 0.05.

Furthermore, dextran with different molecular weights (150 kDa, 500 kDa, and 1.5 MDa) was used to prepare different dex-ald precursors and subsequent gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels. Interestingly, the precursor solution consisting of dex-ald (oxidized from 500 kDa dextran) and 10% gelatin formed gel faster than others (Fig. 2E and F). Larger dex-ald chains may entangle more easily than shorter chains; however, they may react with gelatin (the Schiff bases) less efficiently due to low mobility. Rheological investigation indicated that the hydrogel prepared with dex-ald (from 500 kDa dextran) had a higher storage modulus (G′) of 13.5 ± 1.2 kPa at 1 Hz than the others, and the trends were inverse to those in the gelation time (Fig. 2G and H). A hydrogel with 5% dex-ald (produced from 500 kDa dextran) and 10% gelatin had a moderate gelation time (135 s) and cardiac tissue-like modulus (Young's modulus = 40.5 ± 3.6 kPa), which were determined to be appropriate as a paintable hydrogel for cardiac tissues and were used in subsequent studies. After mixing the precursor solution, the viscosity of the hydrogel rapidly increased, and it exhibited a shear-thinning behavior (Fig. S2). Furthermore, we verified the injectability and paintability of the hydrogel by applying the mixed precursor solution in a spiral or straight line on a glass tube. The painted hydrogel remained stably even when tilted at 90° (Fig. S3). Note that cardiac tissue has a modulus range of 20–500 kPa [33]. The hydrogel remained stable without flow after injection using a dual syringe (Fig. 2I). SEM images revealed highly porous structures with a pore size of 3.8 ± 1.7 μm (Fig. 2J). Furthermore, FT-IR spectroscopy indicated that dex-ald and gelatin had characteristic peaks at 1735 cm−1 (aldehyde) and 1633 cm−1 (amide bond), respectively (Fig. S4) [34,35]. In the hydrogel spectra, a new peak was observed at 1056 cm−1 (Schiff base), and the peak at 1735 cm−1 (aldehyde) disappeared [36], implying Schiff base formation in the hydrogel.

3.2. Adhesiveness of gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels

We aimed to develop an adhesive hydrogel cardiac patch that does not require surgical suturing and stably supports the mechanical properties of the epicardium. Hence, we investigated the adhesion characteristics of gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels (Fig. 3). Hydrogels consisting of 10% gelatin and 5% dex-ald were injected onto a tissue piece, followed by coverage of another tissue piece onto the hydrogels (Fig. 3A). The hydrogel had strong interfacial adhesive strengths of 4.2 ± 0.3 kPa and 19.5 ± 1.7 kPa to porcine epicardium and skin, respectively. (Fig. 3A and B). No significant difference in adhesive strength was observed among the hydrogels prepared with dex-ald from different MWs (150 kDa, 500 kDa, and 1.5 MDa) (Fig. S5). Notably, the tissue adhesiveness of our paintable hydrogel was comparable to that of other adhesive cardiac patches [15,37]. In addition, cyclic elongation of the hydrogel-bonded tissues did not cause substantial changes in adhesion strength (Fig. 3C and Movie. S1, S2), indicating excellent durable tissue adhesion. The gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels showed 96.5% and 88.4% of initial lap shear stresses to epicardium and skin tissue, respectively, even after 50 stretching cycles. The hydrogel remained firmly attached to the epicardium under various deformations such as torsion, bending, and water flushing (Fig. 3D). These dynamic conditions can mimic in vivo heart movement and the wet environment in the body. Altogether, our gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel was expected to stably adhere to the epicardium, stably maintain its shape, and function appropriately as a suture-free cardiac patch.

Fig. 3.

Adhesion properties of the paintable hydrogels. (A) Lap shear stress of hydrogels to epicardium and skin tissues. (B) Photographs (distance = 0 mm and distance = 4 mm) of gelatin/dex-ald-tissue samples during the lap shear tests. (C) Cyclic stretching of gelatin/dex-ald-bonded epicardium and skin. Sample-bonded tissues were stretched up to for 50 cycles with 0–4 mm of distance and 60 mm/min tensile rate. (D) Adhesion of (left) hydrogel-bonded porcine epicardium under dynamic conduction and (right) hydrogels-bonded rat heart with water flushing. Arrows indicates the hydrogels remaining on the tissue. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey analysis.

Supplementary video related to this article can be found at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.08.020

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

3.3. ANGPTL4 release from the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel

We incorporated the anti-inflammatory protein, ANGPTL4, which can resolve inflammation in the infarcted heart, into the gelatin dex-ald hydrogels. Because ANGPTL4 can chemically bond with dex-ald via a reversible Schiff base, we expected a high loading capacity and sustained release of ANGPTL4. ANGPTL4 was mixed with a dex-ald solution for conjugation, which was subsequently mixed with gelatin to obtain the ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel (A4/gelatin/dex-ald). The release profile of ANGPTL4 from the hydrogel was examined using Cy5 conjugated ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel (Fig. 4A). Specifically, A4/gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels were incubated in acidic (pH 5.8) or neutral (pH 7.4) buffer solutions, which represent the microenvironments of the ischemic and normal heart tissues, respectively [38]. Gelatin hydrogel was prepared as a control by chemical crosslinking using glutaraldehyde and was used for ANGPTL4 loading by adsorption. Burst release of ANGPTL4 was observed in the control group. For example, 76.7% of the initially loaded ANGPTL4 was released in pH 7.4 within 3 h. In contrast, the A4/gelatin/dex-ald exhibited a sustained release profiles without distinct burst release at an early incubation time point (Fig. 4B). ANGPTL4 was continuously released, and its release was saturated since day 7, implying that ANGPTL4 remained stable within the hydrogel. ANGPL4 release from the A4/gelatin/dex-ald was faster in acidic buffer (pH 5.8) than that in neutral buffer (pH 7.4). Results imply that Schiff base between ANGPTL4 and the hydrogel matrix could be gradually destabilized under acidic conditions, resulting in facilitated ANGPTL4 release. As MI heart exhibits slight acidic pH, ANGPTL4 release might be induced depending on the severity of MI (Fig. 4C). In addition, the modulus of the gelatin/dex-ald gradually decreased, and the hydrogel gradually degraded in the acidic solution, confirming the instability of the Schiff base in acidic microenvironments (Fig. S6). We next evaluated in vivo degradation in subsequent experiments.

Fig. 4.

In vitro release of ANGPTL4 from A4/gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels and gelatin hydrogels. (A) Cumulative release profiles of ANGPTL4 from the gelatin/dex-ald and gelatin control (crosslinked with glutaraldehyde) during the incubation. In vitro release tests were performed using Cy5-tagged ANGPTL4 in release buffer solutions (pH 5.8 and 7.4). (B) Inset of (A). (C) Schematic illustration for sustained release of ANGPTL4 through reversible Schiff base between dex-ald and ANGPTL4.

3.4. In vitro cell culture with gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels

We investigated cytocompatibility by culturing CMs with the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel in both direct and indirect culture modes. The LDH assay revealed that CMs cultured in the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels exhibited excellent cell viability for up to 7 days (Fig. 5A). In addition, CMs cultured with hydrogel in a Transwell insert as an indirect contact mode had a high viability (>95%) up to for 7 days (Fig. 5B). Live/dead staining indicated no significant differences in cell viability between CMs cultured in a Transwell insert with hydrogels and CMs cultured on tissue culture plates (TCP) (Fig. 5C and D). The cytocompatibility of the in situ formed gelatin/dex-ald was further investigated by placing the hydrogels (5 min after mixing the precursor solution) onto the CMs cultured in TCP (Fig. S7). After 48 h of incubation, cell viability was not significantly different from that of control (CMs cultured in TCP without a hydrogel) (Fig. S7), indicating no substential cytotoxicity of the gelatin and dex-ald. Such excellent cytocompatibility of the hydrogel might be attributed to the inherent biocompatibility of the matrix materials (i.e., gelatin and dextran) used for hydrogels [23,39]. Maturation of CMs cultured on the hydrogels was examined by immunofluorescent staining for sarcomeric α-actinin and connexin 43 (CX-43), which are microfilaments and gap junction proteins, respectively [40,41]. As shown in Fig. 5E, high expression of α-actinin and distinct sarcomere structures was observed in the CMs cultured on the hydrogel on day 7 of culture. Importantly, CX-43 was densely expressed on the CM membranes, particularly between CMs, indicating well-developed intercellular junctions between CMs. Our results suggest that our gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel displayed excellent cytocompatibility and supported CM maturation.

Fig. 5.

In vitro cytotoxicity tests. LDH assay of (A) CMs directly cultured on the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel and (B) CMs cultured in the transwell insert with the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel (indirect contact). (C) Live (green)/dead (red) staining images of the CMs cultured on TCP or in the transwell insert with the hydrogel for 3 and 7 days. Scale bars = 200 μm. (D) Calcein AM positive area per image in each group. (E) Immunofluorescence staining for α-actinin (red), CX-43 proteins (green), and nuclei (blue) of the CMs cultured on the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel for 7 days. Scale bars = 50 μm.

In general, macrophages play critical roles in inflammation as they polarize either pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypes which induce or resolve inflammation, respectively, in infarcted hearts [42]. ANGPTL4 has an anti-inflammatory effect on activated macrophages to induce cardiovascular repair in MI, atherosclerosis, and peritonitis mouse models [22]. In this study, we investigated the inflammation-related mediators in RAW264.7 cells cultured with the hydrogels in medium containing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to confirm the anti-inflammatory ability of the ANTPTL4 delivered by a gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel. Gene expression of inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, iNOS, TNF-α, and CCL2, were significantly suppressed in LPS-stimulated macrophages cultured with the ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel (Fig. S8). Moreover, inflammatory cytokine levels (IL-1β and IL-6) in the ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel group were significantly lower than those in ANGPTL4-free groups (untreated and hydrogel only). Results suggest that ANGPTL4 delivered using a gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel patch can suppress inflammatory polarization of macrophages and potentially attenuate inflammation of infarcted heart.

3.5. In vivo paintability and degradability of gelatin/dex-ald

We examined the applicability of the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel as a paintable cardiac patch using a live rat. Dex-ald (5%) and gelatin (10%) solutions were loaded into the individual barrels using a dual syringe and injected for mixing. After approximately 3 min of incubation, the hydrogel (100 μL) was transferred and painted on an infarcted rat heart (Movie. S3). The painted hydrogel successfully covered the entire LV, including the infarcted zone, and remained intact on the LV of the beating heart (Fig. 6A and Movie. S4). Heart patches with an appropriate in vivo degradation profile are highly favored because heart patches should mechanically support heart functions to prevent excessive dilation and pathological remodeling during heart repair and eventually disappear without causing mechanical disturbances in the heartbeat after repair. The in vivo biodegradability of the painted gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels was examined by harvesting the heart tissues on days 7 and 14 post treatment (Fig. 6B), which revealed that the painted hydrogels gradually degraded. Approximately 46.6% and 30.0% of the initial patches on hearts remained on days 7 and 14, respectively, indicating in vivo degradability of the painted gelatin/dex-ald patch. Gelatin/dex-ald is believed to degrade via hydrolysis of the Schiff base and enzymatic/hydrolytic degradation of gelatin and dex-ald strands [[43], [44], [45]]. Partially oxidized dextran (i.e., dex-ald) has a hydrolyzable ring-opened structure in its backbone [46,47]. Gelatin is cleaved by various enzymes such as collagenases. Altogether, we demonstrated the proper paintability and in vivo degradation of gelatin/dex-ald for its cardiac patch application.

Fig. 6.

In vivo studies for paintability and degradability of gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels on heart. (A) Photographs of the procedures for painting the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel as an epicardial patch; (i) mixing of gel precursor solutions using dual syringe, (ii) transfer of the mixed hydrogel onto a rat epicardium, (iii) painting of the hydrogel on the rat epicardium, (iv) the painted hydrogel cardiac patch on heart. (B) Photographs of the hearts painted with gelatin/dex-ald hydrogels on day 0, day 7, and day 14. Arrows indicates the hydrogels remaining on the hearts.

Supplementary video related to this article can be found at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.08.020

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

3.6. Cardiac repair using ANGPTL4-loaded paintable hydrogel

To determine whether the A4/gelatin/dex-ald patch improves cardiac function after MI, we measured ventricular contractility using echocardiography on day 14 post-MI. Experimental groups including sham, MI, MI with gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel patch, and MI with A4/gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel patch are illustrated in Fig. 7A. The representative echocardiograms showed an increased LV dimension and a decrease in intraventricular septum and posterior wall movement in the MI group, which were attenuated in the gelatin/dex-ald and A4/gelatin/dex-ald groups (Fig. 7B). Systolic dysfunction, characterized by EF and FS, was attenuated in both the gelatin/dex-ald and A4/gelatin/dex-ald groups compared to the MI group. For example, EF(%) values for the sham and MI groups were 61.4 ± 2.5 and 22.7 ± 1.8, respectively, whereas the gelatin/dex-ald and A4/gelatin/dex-ald groups showed EF(%) values of 31.6 ± 2.9 and 36.7 ± 2.8, respectively (Fig. 7C). FS(%) values displayed trends similar to EF(%) (Fig. 7D). A4/gelatin/dex-ald group was superior to the gelatin/dex-ald group in terms of EF(%) and FS(%) recovery. These results indicated that hydrogel patches (gelatin/dex-ald and A4/gelatin/dex-ald) had positive effects on cardiac functional recovery, and A4 incorporation further improved functional recovery. MI-induced fibrotic scar formation was analyzed using Masson's trichrome staining (Fig. 7E). Fibrosis area was significantly reduced by A4/gelatin/dex-ald treatment, which was smaller than those in the MI and gelatin/dex-ald groups (Fig. 7F). In addition, the decrease in LV wall thickness was attenuated in the patch-treated groups, in which the A4-loaded cardiac patch was more effective (Fig. 7G). For example, LV wall thicknesses were 1.13 ± 0.22, 1.49 ± 0.23, and 2.69 ± 0.20 for the MI, gelatin/dex-ald, and A4/gelatin/dex-ald groups, respectively. These results indicate that hydrogel patch treatment and ANGPTL4 local delivery ameliorated cardiac remodeling and dysfunction post-MI by providing mechanical support and inflammation-resolving therapeutics to the infarcted heart.

Fig. 7.

Effects of gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel cardiac patches on heart functions and remodeling after MI. (A) Photographs of experimental groups (sham, MI, gelatin/dex-ald, and A4/gelatin/dex-ald). (B) Representative echocardiographic images after 2 weeks MI and treatment. (C, D) The LV function parameters (EF and FS) in various groups after 2 weeks MI. (E) Representative heart photographs and Masson's trichrome staining images of the isolated hearts after 2 weeks MI and treatment. Arrows indicate the hydrogels remaining on heart. (F) Fibrosis area and (F) LV wall thickness in each group. n = 4 (sham), n = 5 (MI), n = 5 (gelatin/dex-ald), and n = 5 (A4/gelatin/dex-ald). Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey analysis. *p < 0.05.

Next, we determined the role of the hydrogel patches in angiogenesis using α-SMA and vWF immunofluorescence staining. A4/gelatin/dex-ald patch treatment markedly increased neovessel formation, especially in the border zones, compared to the MI and gelatin/dex-ald groups (Fig. 8A and Fig. S9A). Enhanced angiognesis in the A4/gelatin/dex-ald patch group may be attributed to a pro-angiogenic ability of ANGPTL4 and reduced inflammation. ANGPTL4 possesses an ability to induce neovasculization. Furthermore, the type and distribution of macrophages were assessed by staining for CD68 (a pan-macrophage marker) and CD206 (an anti-inflammatory macrophage marker) (Fig. 8B, Fig. S9B, Fig. S9C, and Fig. S10). Hence, CD68+/CD206-cells and CD68+/CD206+ cells indicate M1 and M2 macrophages, respectively. A higher frequency of anti-inflammatory macrophages in the infarct area was found in the patch-treated groups than in the MI group, and infarcted heart tissues treated with A4/gelatin/dex-ald displayed more anti-inflammatory macrophages than those treated with gelatin/dex-ald, suggesting the anti-inflammatory role of ANGPTL4 delivered from the hydrogel patch. ICAM-1 staining, indicating inflammatory macrophages, demonstrated the reduction of inflammatory tissue reactions by patch treatment (Fig. S11). The innate immune system is rapidly activated by MI and induces inflammation. In particular, reparative inflammation in the later phase is essential for cardiac repair following MI [48]. We previously showed that ANGPTL4 exerts cardioprotective effects via anti-inflammatory activity in an MI mouse model [22]. In addition, anti-inflammatory macrophages secrete several pro-angiogenic molecules, including VEGF, TGFβ, IL-10, aEMC10 (endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein complex subunit 10), and MYDGF (myeloid-derived growth factor), and induce vascularization [[49], [50], [51]]. We found that inflammatory macrophages, which increased remarkably post-MI, were suppressed by ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel patch treatment. Results imply that local and sustained release of the ANGPTL4 from the hydrogel patch induced macrophage polarization to anti-inflammatory phenotype and promote angiogenesis [49]. Altogether, the ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel patch significantly improved cardiac function, inhibited myocardial fibrosis, promoted angiogenesis, and polarized macrophages toward anti-inflammatory activity compared with the gelatin/dex-ald group.

Fig. 8.

Representative immunofluorescence images of rat heart tissues 2 weeks after MI. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of vWF (an endothelial marker, green) and α-SMA (a vascular protein marker, red) in the border zone. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of CD68 (a macrophage marker, green) and CD206 (an anti-inflammatory macrophage marker, red) in the border zone. Yellow color in the fluorescence images indicate co-localization of CD68 and CD206. Upper images are the corresponding images of Masson's Trichrome staining in each group (A and B).

Additionally, the inflammatory cytokine levels in the blood were measured on day 14 using ELISA kits (Fig. S12). TNF-α and IL-6 levels were highly upregulated in the MI group. In contrast, TNF-α and IL-6 levels were reduced in both patch-treated groups, in which IL-6 levels were lower in the A4/gelatin/dex-ald group than in the gelatin/dex-ald group (Fig. S12). These results confirmed that local delivery of ANGPTL4 using a hydrogel cardiac patch is effective in inducing the cardiac repair pathway by promoting anti-inflammation and angiogenesis.

4. Conclusion

We successfully developed biocompatible and adhesive hydrogels that enable in situ gel formation via Schiff base using 10% gelatin and 5% dex-ald. This hydrogel was suitable for cardiac patches that can be attached to the epicardium via stable tissue adhesion without sutures, providing tissue-like softness and mechanical support for efficient cardiac repair post MI. In addition, the tissue regenerative factor ANGPTL4 was loaded onto the gelatin/dex-ald hydrogel for local and sustained delivery. The ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel patch improved functional recovery of infarcted hearts and prevented pathological tissue remodeling. Immunohistological analyses indicated that the ANGPTL4-loaded hydrogel patch enhanced angiogenesis and increased the number of anti-inflammatory macrophages in infarcted myocardium. Our ANGPTL4-loaded adhesive hydrogel patch is beneficial for infarcted heart repair. Our study may also provide useful information for future technologies, which may lead to the better development of regenerative therapeutics for cardiovascular diseases.

Statement on ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. All participants reviewed the methodological, ethical, legal and societal issues involved in the research and in the uses of animal study. All animal study was performed with approval from the Chonnam National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (study approval code: CNUHIACUC-22013), and all experiments were performed after approval by a local ethical committee at Chonnam National University Medical School.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Jae Young Lee reports financial support was provided by National Research Foundation of Korea.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mingyu Lee: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Yong Sook Kim: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Junggeon Park: Investigation, Methodology. Goeun Choe: Investigation, Methodology. Sanghun Lee: Investigation, Methodology. Bo Gyeong Kang: Investigation, Methodology. Ju Hee Jun: Investigation, Methodology. Yoonmin Shin: Methodology. Minchul Kim: Investigation. Youngkeun Ahn: Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Jae Young Lee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (NRF-2021M3H4A1A04092882 and NRF-2021R1A4A3025206).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.08.020.

Contributor Information

Youngkeun Ahn, Email: cecilyk@hanmail.net.

Jae Young Lee, Email: jaeyounglee@gist.ac.kr.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Tsao C.W., Aday A.W., Almarzooq Z.I., Alonso A., Beaton A.Z., Bittencourt M.S., Boehme A.K., Buxton A.E., Carson A.P., Commodore-Mensah Y., Elkind M.S.V., Evenson K.R., Eze-Nliam C., Ferguson J.F., Generoso G., Ho J.E., Kalani R., Khan S.S., Kissela B.M., Knutson K.L., Levine D.A., Lewis T.T., Liu J., Loop M.S., Ma J., Mussolino M.E., Navaneethan S.D., Perak A.M., Poudel R., Rezk-Hanna M., Roth G.A., Schroeder E.B., Shah S.H., Thacker E.L., VanWagner L.B., Virani S.S., Voecks J.H., Wang N.-Y., Yaffe K., Martin S.S. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2022;145:e153–e639. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Z., Tan Y., Li Y., Liu Y., Yi G., Yu C.-Y., Wei H. Biotherapeutic-loaded injectable hydrogels as a synergistic strategy to support myocardial repair after myocardial infarction. J. Contr. Release. 2021;335:216–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu L., Liu M., Sun R., Zheng Y., Zhang P. Myocardial infarction: symptoms and treatments. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015;72:865–867. doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weil B.R., Neelamegham S. Selectins and immune cells in aucte mycardial infarction and post-infarction ventricular remodelings: pathophysiology and novel treatments. Front. Immunol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adapala R.K., Kanugula A.K., Paruchuri S., Chilian W.M., Thodeti C.K. TRPV4 deletion protects heart from myocardial infarction-induced adverse remodeling via modulation of cardiac fibroblast differentiation. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2020:115. doi: 10.1007/s00395-020-0775-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y., Zhu D., Wei Y., Wu Y., Cui W., Liuqin L., Fan G., Yang Q., Wang Z., Xu Z., Kong D., Zeng L., Zhao Q. A collagen hydrogel loaded with HDAC7-derived peptide promotes the regeneration of infarcted myocardium with functional improvement in a rodent model. Acta Biomater. 2019;86:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu T., Cui C., Huang Y., Liu Y., Fan C., Han X., Yang Y., Xu Z., Liu B., Fan G., Liu W. Coadministration of an adhesive conductive hydrogel patch and an injectable hydrogel to treat myocardial infarction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:2039–2048. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b17907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pecha S., Eschenhagen T., Reichenspurner H. Myocardial tissue engineering for cardiac repair. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Contessotto P., Pandit A. Therapies to prevent post-infarction remodelling: from repair to regeneration. Biomaterials. 2021;275 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y., Wei L., Lan L., Gao Y., Zhang Q., Dawit H., Mao J., Guo L., Shen L., Wang L. Conductive biomaterials for cardiac repair: a review. Acta Biomater. 2022;139:157–178. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee M., Kim M.C., Lee J.Y. Nanomaterial-based electrically conductive hydrogels for cardiac tissue repair. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022;17:6181–6200. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S386763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu T., Liu W. Functional hydrogels for the treatment of myocardial infarction. NPG Asia Mater. 2022;14:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41427-021-00330-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang S., Zhang Y., Wang H., Xu Z., Chen J., Bao R., Tan B., Cui Y., Fan G., Wang W., Wang W., Liu W. Paintable and rapidly bondable conductive hydrogels as therapeutic cardiac patches. Adv. Mater. 2018;30 doi: 10.1002/adma.201704235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L., Jiang J., Hua W., Darabi A., Song X., Song C., Zhong W., Xing M.M.Q., Qiu X. Mussel-inspired conductive cryogel as cardiac tissue patch to repair myocardial infarction by migration of conductive nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:4293–4305. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201505372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker B.W., Lara R.P., Yu C.H., Sani E.S., Kimball W., Joyce S., Annabi N. Engineering a naturally-derived adhesive and conductive cardiopatch. Biomaterials. 2019;207:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin J., Choi S., Kim J.H., Cho J.H., Jin Y., Kim S., Min S., Kim S.K., Choi D., Cho S.-W. Tissue Tapes—phenolic hyaluronic acid hydrogel patches for off-the-shelf therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29 doi: 10.1002/adfm.201903863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuk H., Varela C.E., Nabzdyk C.S., Mao X., Padera R.F., Roche E.T., Zhao X. Dry double-sided tape for adhesion of wet tissues and devices. Nature. 2019;575:169–174. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1710-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang J., Vandergriff A., Wang Z., Hensley M.T., Cores J., Allen T.A., Dinh P.-U., Zhang J., Caranasos T.G., Cheng K. A regenerative cardiac patch formed by spray painting of biomaterials onto the heart. Tissue Eng. C Methods. 2017;23:146–155. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2016.0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westman P.C., Lipinski M.J., Luger D., Waksman R., Bonow R.O., Wu E., Epstein S.E. Inflammation as a driver of adverse left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;67:2050–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez Perdiguero E., Liabotis-Fontugne A., Durand M., Faye C., Ricard-Blum S., Simonutti M., Augustin S., Robb B.M., Paques M., Valenzuela D.M., Murphy A.J., Yancopoulos G.D., Thurston G., Galaup A., Monnot C., Germain S. ANGPTL4–αvβ3 interaction counteracts hypoxia-induced vascular permeability by modulating Src signalling downstream of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. J. Pathol. 2016;240:461–471. doi: 10.1002/path.4805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh Y.Y., Pal M., Chong H.C., Zhu P., Tan M.J., Punugu L., Lam C.R.I., Yau Y.H., Tan C.K., Huang R.-L., Tan S.M., Tang M.B.Y., Ding J.L., Kersten S., Tan N.S. Angiopoietin-like 4 interacts with integrins β1 and β5 to modulate keratinocyte migration. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177:2791–2803. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho D.I., Kang H.-J., Jeon J.H., Eom G.H., Cho H.H., Kim M.R., Cho M., Jeong H.-Y., Cho H.C., Hong M.H., Kim Y.S., Ahn Y. Antiinflammatory activity of ANGPTL4 facilitates macrophage polarization to induce cardiac repair. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guan S., Zhang K., Cui L., Liang J., Li J., Guan F. Injectable gelatin/oxidized dextran hydrogel loaded with apocynin for skin tissue regeneration. Biomater. Adv. 2022;133 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang D., Chang R., Ren Y., He Y., Guo S., Guan F., Yao M. Injectable and reactive oxygen species-scavenging gelatin hydrogel promotes neural repair in experimental traumatic brain injury. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;219:844–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan J., Yuan L., Guo C., Geng X., Fei T., Fan W., Li S., Yuan H., Yan Z., Mo X. Fabrication of modified dextran–gelatin in situ forming hydrogel and application in cartilage tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2014;2:8346–8360. doi: 10.1039/C4TB01221F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu S., Yu C., Liu N., Zhao M., Chen Z., Liu J., Li G., Huang H., Guo H., Sun T., Chen J., Zhuang J., Zhu P. Injectable conductive gelatin methacrylate/oxidized dextran hydrogel encapsulating umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for myocardial infarction treatment. Bioact. Mater. 2022;13:119–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park J., Jeon J., Kim B., Lee M.S., Park S., Lim J., Yi J., Lee H., Yang H.S., Lee J.Y. Electrically conductive hydrogel nerve guidance conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020;30 doi: 10.1002/adfm.202003759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choe G., Park J., Jo H., Kim Y.S., Ahn Y., Lee J.Y. Studies on the effects of microencapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells in RGD-modified alginate on cardiomyocytes under oxidative stress conditions using in vitro biomimetic co-culture system. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;123:512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choe G., Kim S.-W., Park J., Park J., Kim S., Kim Y.S., Ahn Y., Jung D.-W., Williams D.R., Lee J.Y. Anti-oxidant activity reinforced reduced graphene oxide/alginate microgels: mesenchymal stem cell encapsulation and regeneration of infarcted hearts. Biomaterials. 2019;225 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han K., Bai Q., Wu W., Sun N., Cui N., Lu T. Gelatin-based adhesive hydrogel with self-healing, hemostasis, and electrical conductivity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;183:2142–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X., Jiang Y., Han L., Lu X. Biodegradable polymer hydrogel-based tissue adhesives: a review. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2021;7:163–179. doi: 10.1049/bsb2.12016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nam S., Mooney D. Polymeric tissue adhesives. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:11336–11384. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qazi T.H., Rai R., Dippold D., Roether J.E., Schubert D.W., Rosellini E., Barbani N., Boccaccini A.R. Development and characterization of novel electrically conductive PANI–PGS composites for cardiac tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:2434–2445. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu Y., Zhang J., Wang Y., Li J., Bao J., Xu X., Zhang C., Li Y., Wu H., Gu Z. Reduced polydopamine nanoparticles incorporated oxidized dextran/chitosan hybrid hydrogels with enhanced antioxidative and antibacterial properties for accelerated wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;257 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L., Ge J., Ma P.X., Guo B. Injectable conducting interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels from gelatin- graft -polyaniline and oxidized dextran with enhanced mechanical properties. RSC Adv. 2015;5:92490–92498. doi: 10.1039/C5RA19467A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen D., Hu Q., Sun J., Pang X., Li X., Lu Y. Effect of oxidized dextran on the stability of gallic acid-modified chitosan–sodium caseinate nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;192:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin X., Liu Y., Bai A., Cai H., Bai Y., Jiang W., Yang H., Wang X., Yang L., Sun N., Gao H. A viscoelastic adhesive epicardial patch for treating myocardial infarction. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3:632–643. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu D., Hou J., Qian M., Jin D., Hao T., Pan Y., Wang H., Wu S., Liu S., Wang F., Wu L., Zhong Y., Yang Z., Che Y., Shen J., Kong D., Yin M., Zhao Q. Nitrate-functionalized patch confers cardioprotection and improves heart repair after myocardial infarction via local nitric oxide delivery. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4501. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24804-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidenko N., Schuster C.F., Bax D.V., Farndale R.W., Hamaia S., Best S.M., Cameron R.E. Evaluation of cell binding to collagen and gelatin: a study of the effect of 2D and 3D architecture and surface chemistry. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2016;27:148. doi: 10.1007/s10856-016-5763-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shadrin I.Y., Allen B.W., Qian Y., Jackman C.P., Carlson A.L., Juhas M.E., Bursac N. Cardiopatch platform enables maturation and scale-up of human pluripotent stem cell-derived engineered heart tissues. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1825. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01946-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y., Shi X., Tian L., Sun H., Wu Y., Li X., Li J., Wei Y., Han X., Zhang J., Jia X., Bai R., Jing L., Ding P., Liu H., Han D. AuNP–Collagen matrix with localized stiffness for cardiac-tissue engineering: enhancing the assembly of intercalated discs by β1-integrin-mediated signaling. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:10230–10235. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L., Cao J., Li S., Cui T., Ni J., Zhang H., Zhu Y., Mao J., Gao X., Midgley A.C., Zhu M., Fan G. M2 macrophage-derived sEV regulate pro-inflammatory CCR2+ macrophage subpopulations to favor post-AMI cardiac repair. Adv. Sci. 2023;10 doi: 10.1002/advs.202202964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tondera C., Hauser S., Krüger-Genge A., Jung F., Neffe A.T., Lendlein A., Klopfleisch R., Steinbach J., Neuber C., Pietzsch J. Gelatin-based hydrogel degradation and tissue interaction in vivo: insights from multimodal preclinical imaging in immunocompetent nude mice. Theranostics. 2016;6:2114–2128. doi: 10.7150/thno.16614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ullm S., Krüger A., Tondera C., Gebauer T.P., Neffe A.T., Lendlein A., Jung F., Pietzsch J. Biocompatibility and inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo to gelatin-based biomaterials with tailorable elastic properties. Biomaterials. 2014;35:9755–9766. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nonsuwan P., Matsugami A., Hayashi F., Hyon S.-H., Matsumura K. Controlling the degradation of an oxidized dextran-based hydrogel independent of the mechanical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;204:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hozumi T., Kageyama T., Ohta S., Fukuda J., Ito T. Injectable hydrogel with slow degradability composed of gelatin and hyaluronic acid cross-linked by schiff's base formation. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:288–297. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chimpibul W., Nagashima T., Hayashi F., Nakajima N., Hyon S.-H., Matsumura K. Dextran oxidized by a malaprade reaction shows main chain scission through a maillard reaction triggered by schiff base formation between aldehydes and amines. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. 2016;54:2254–2260. doi: 10.1002/pola.28099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nahrendorf M., Pittet M.J., Swirski F.K. Monocytes: protagonists of infarct inflammation and repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:2437–2445. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.916346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jetten N., Verbruggen S., Gijbels M.J., Post M.J., De Winther M.P.J., Donners M.M.P.C. Anti-inflammatory M2, but not pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages promote angiogenesis in vivo. Angiogenesis. 2014;17:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reboll M.R., Korf-Klingebiel M., Klede S., Polten F., Brinkmann E., Reimann I., Schönfeld H.-J., Bobadilla M., Faix J., Kensah G., Gruh I., Klintschar M., Gaestel M., Niessen H.W., Pich A., Bauersachs J., Gogos J.A., Wang Y., Wollert K.C. EMC10 (endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein complex subunit 10) is a bone marrow–derived angiogenic growth factor promoting tissue repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2017;136:1809–1823. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korf-Klingebiel M., Reboll M.R., Klede S., Brod T., Pich A., Polten F., Napp L.C., Bauersachs J., Ganser A., Brinkmann E., Reimann I., Kempf T., Niessen H.W., Mizrahi J., Schönfeld H.-J., Iglesias A., Bobadilla M., Wang Y., Wollert K.C. Myeloid-derived growth factor (C19orf10) mediates cardiac repair following myocardial infarction. Nat. Med. 2015;21:140–149. doi: 10.1038/nm.3778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.