Abstract

Exacerbations of COPD are associated with worsening of the airflow obstruction, hospitalisation, reduced quality of life, disease progression and death. At least 70% of COPD exacerbations are infectious in origin, with respiratory viruses identified in approximately 30% of cases. Despite long-standing recommendations to vaccinate patients with COPD, vaccination rates remain suboptimal in this population.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the leading morbidity and mortality causes of lower respiratory tract infections. The Food and Drug Administration recently approved pneumococcal conjugate vaccines that showed strong immunogenicity against all 20 included serotypes. Influenza is the second most common virus linked to severe acute exacerbations of COPD. The variable vaccine efficacy across virus subtypes and the impaired immune response are significant drawbacks in the influenza vaccination strategy. High-dose and adjuvant vaccines are new approaches to tackle these problems. Respiratory syncytial virus is another virus known to cause acute exacerbations of COPD. The vaccine candidate RSVPreF3 is the first authorised for the prevention of RSV in adults ≥60 years and might help to reduce acute exacerbations of COPD. The 2023 Global Initiative for Chronic Lung Disease report recommends zoster vaccination to protect against shingles for people with COPD over 50 years.

Tweetable abstract

Infectious disease prevention through immunisation is a cornerstone prophylactic measure against exacerbations but there is much room for improvement. Awareness of vaccinations should be improved in physicians and patients with COPD. https://bit.ly/3Y6fAwM

Introduction

COPD is the third leading cause of death worldwide and its incidence is predicted to increase until at least 2030 [1]. Frequent exacerbations are among the key factors of poor prognosis of COPD and associated with morbidity and mortality and poor quality of life [2, 3]. Exacerbation prevention is a key goal of therapy in COPD. History of previous exacerbation events is the largest risk factor for predicting future exacerbations [4]. Multiple risk factors such as reduced mucociliary clearance, gastro–oesophageal reflux and immune deficiency have been shown and many patients will have several predisposing conditions or environmental factors [5]. A majority of COPD exacerbations are triggered by viral and/or bacterial infections. Influenza and pneumococcal infections are two of the most important reasons for hospitalisation and death in patients with chronic disease [2, 6] and vaccination against both is recommended in guidelines. Co-infections with two or more viruses or viruses and bacteria have been reported in up to 25% of all acute exacerbations in COPD in observational studies [7, 8]. Despite studies and national guidelines demonstrating that vaccinations are beneficial in COPD patients, vaccination coverage remains low in this patient group. As a result of infection control measures implemented during the pandemic, there was a significant decrease in all non-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pathogens [9]. However, following the pandemic, there is a strong increase, particularly in pneumococci [10].

Vaccinations against bacterial and viral infections such as pneumococcus, pertussis, influenza, SARS-CoV-2, herpes zoster (HZ) and, in the near future, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are important preventive healthcare measures in patients with COPD. Primarily due to vaccine developments during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, research in this area has increased significantly. This review discusses the most relevant immunisation strategies that are already available or expected soon. It focuses on the most important vaccination strategies for patients with COPD.

Pneumococcal vaccine

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a Gram-positive, extracellular, opportunistic pathogen colonising the mucosal surfaces of human upper airways. Up to 27–65% of children and <10% of adults are carriers of pneumococcus [11]. A wide range of infections, including otitis media, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), sepsis and meningitis are caused by S. pneumoniae. It has been reported as the leading morbidity and mortality cause in lower respiratory tract infections and responsible for more deaths than all other pathogens [12].

Known triggers of COPD exacerbations include viruses, bacteria and air pollutants. Pneumococcal pneumonia is a major cause of increased morbidity and mortality in COPD patients. CAP foreshadows a prolonged increase in risk of exacerbations of underlying COPD in adults. In a retrospective matched-cohort study from the US, patients with COPD and CAP were 42.3% more likely to experience an exacerbation (16% versus 11%; p<0.001) [13]. These data suggest a potential benefit of CAP prevention strategies. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 guidelines recommend vaccination against pneumococcus for patients with COPD to prevent severe illnesses [14].

The 23-valent polysaccharide-based vaccine (PPV23) has existed for many years and is recommended by many public health agencies for adults ≥65 years of age and other high-risk groups. PPSV23 covers the most common pneumococcal serotypes, but vaccination with pneumococcal polysaccaride-based vaccines (PPVs) produces an immunoresponse that is limited to B-cell stimulation and antibody production [15]. Furthermore, the absence of memory B-cell training leads to a waning immunity response over the years, especially in elderly people. Clinical efficacy against CAP in at-risk populations has been inconsistent [16–18]. In contrast, PCVs tend to be more consistently immunogenic than PPV and increase the duration in memory of antipneumococcal immunoresponse. PCVs contain pneumococcal polysaccharide antigens covalently linked to immunogenic carrier proteins that induce a T-cell-dependent humoral immunoresponse and stimulate T-cells to help B-cells in producing antibodies. This process enhances the vaccine's ability to create a better lasting immune memory [19]. Three types of PCVs are licensed for adults (PCV13, PCV15 and PCV20).

CAPITA, a large prospective randomised, placebo-controlled trial with >84 000 participants aged ≥65 years, was conducted to assess the clinical efficacy of PCV13 in older adults [20]. Among these age groups, PCV13 was effective in preventing vaccine-type pneumococcal, bacteraemic and nonbacteraemic CAP and vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease. Serotype 3, which was included into PCV13, seems to be unaffected by herd protection effects. It has been associated with disease severity and has become one of the leading serotypes in adult CAP [21, 22]. The decreased efficacy against serotype 3 as well as the lack of herd protection of this major serotype is not completely understood. A recently published meta-analysis showed a reduction of invasive pneumococcal disease in elderly and high-risk populations vaccinated by PPV23 and PCV13, with a lower protective effect in individuals aged >80 years and with comorbidities [23]. Most studies from this meta-analysis found a lower vaccine efficacy (VE) of PPV23 in populations with comorbidities and in immunocompromised populations compared with the VE for individuals without comorbidities [24, 25]. Djennad et al. [24] found a VE of 45% among those without any risk factors followed by a VE among the high-risk immunocompetent of 25% (95% CI 11–37%) and 13% among the immunocompromised. In a prospective multicentre study conducted in adults aged ≥65 years hospitalised with CAP, the authors evaluated the field effectiveness of PCV13, PPSV23 and sequential vaccination against pneumococcal pneumonia in older adults [26]. A case-control test-negative design was used to estimate VE. Of 1525 cases with CAP hospitalisation, 11% were identified as pneumococcal CAP. In elderly patients (>75 years), the adjusted VE was statistically insignificant with 40% for PCV13 and 11% for PPSV23 with high confidence intervals. However, in the younger subgroup (65–74 years), sequential PCV13/PPSV23 vaccination showed the highest adjusted VE of 80%, followed by single-dose PCV13 with 66% and PPSV23 with 19%. Therefore, sequential PCV13/PPSV23 vaccination was most effective for preventing pneumococcal CAP among patients aged 65–74 years. At-risk adults would benefit greatly from vaccination against a broader range of serotypes. Sequential administration of PPSV23 6 and 12 months after PCV induces a higher immune response than PCV alone [27]. Longer intervals between vaccination may improve immune response to serotypes shared between PCV and PPSV23 [28]. The potential benefit of earlier protection against PPSV23-unique serotypes with a shorter time interval should be considered in at-risk populations (e.g. condition after splenectomy). The comparative effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination with PPV23 and PCV13 in COPD patients was evaluated in a 5-year cohort study [29]. During the first year after vaccination, both types significantly reduced the rate of pneumonia. Up to the second year, the clinical effectiveness of PPV23 decreased as compared to PCV. The difference was particularly clear 5 years after vaccination. Pneumonia was registered in 47% of patients in the PPV23 group versus 3.3% of patients in the PCV13 group (p<0.001) with similar results in COPD exacerbations (81.3% versus 23.6%; p<0.001). Randomised controlled trials to evaluate the effect of sequential vaccination with PSV13 and PPSV23 in COPD are scarce.

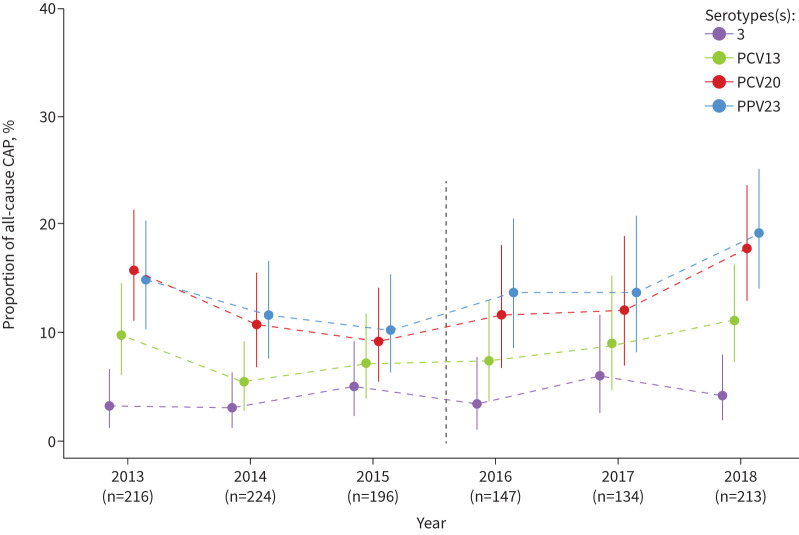

Despite the introduction of multivalent pneumococcal vaccines with major effects in reducing pneumococcal disease, serotypes not covered by PCV13 still cause significant disease [30]. Over time, serotype replacement, i.e. replacement of vaccine serotypes by nonvaccine serotypes, has decreased the serotype coverage of PCVs [31, 32]. Carriage of PCV13 serotypes 3 and 19A was low in a longitudinal analysis of pneumococcal vaccine serotypes in pneumonia patients from Germany (figure 1) [33].

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of serotypes in all-cause community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) covered by pneumococcal vaccine types from 2013 to 2018 in Germany. The graph was made by Miriam Kesselmeier, Institute of Medical Statistics, Computer and Data Sciences, Jena University Hospital/Friedrich-Schiller-University. For the data covering the years 2013–2018, refer to [34].

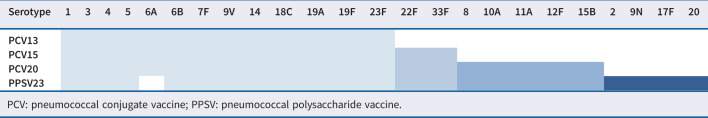

Recently, new 15- and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV15 and PCV20) were developed and licensed for use for the prevention of invasive disease and pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae in adults. The newly available PCV15 and PCV20 vaccines contain additional serotypes 22F and 33F in PCV15 and 22F, 33F, 8, 10A, 11A, 12F and 15B in PCV20, respectively (table 1). The immunogenicity of PCV20 in adults has been established in a number of double-blind [35, 36] and open-label [37] randomised, controlled clinical trials. A single dose by intramuscular injection induced a robust immune response to all S. pneumoniae serotypes covered by the vaccine [35, 37]. Data from Denmark and England showed a reduced incidence and mortality in adults through protection with PCV20 in comparison to PPV23, which could potentially reduce the financial burden related to managing pneumococcal diseases [38, 39]. This expansion of serotype coverage relative to other PCVs presents a promising new tool. The latest Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommendations included either PCV20 alone or a sequential vaccination with PCV15 and PPSV23 in selected adults (based on age and risk factors).

TABLE 1.

Licensed pneumococcal vaccine types and included serotypes

A 24-valent PCV including four more serotypes and V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine containing all 13 serotypes of PCV13 and additional serotypes 22F and 33F are under development. These new vaccine types include not only more serotypes, but also represent a new technology with a more robust immune response. Furthermore, the results of the phase 1/2 from a 21-valent PCV (V116) that contains pneumococcal polysaccharides were published in 2023 [40]. It was well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to PPSV23 and licensed PCVs. The vaccine was noninferior to PPSV23 for the 12 serotypes common to both vaccines and superior to PPSV23 for the nine unique serotypes in V116.

Despite the high morbidity and mortality of pneumococcal disease in COPD patients, vaccination coverage rates remain far below the World Health Organization's (WHO's) recommended targets. Use of and adherence to PCV13/PPSV23 vaccination was low (10%/33%) in patients with COPD in a study from Germany [41]. Sequential vaccination of PCV13 and PPSV23 was performed in 12.8% of patients with COPD [41]. Another group from Greece investigated the pneumococcal vaccination rates in younger COPD patients and found a low coverage of 32.5% in patients aged 40–65 years old [42]. Positively connected with pneumococcal vaccine coverage was age, advanced stage of COPD, years of COPD diagnosis, respiratory infection within the previous 2 years, comorbidity and smoking cessation [42]. In contrast, gender, education level and marital status did not affect influenza and pneumococcus vaccination rates [42]. In a recent study from Turkey, vaccination rates were found to be low (17%) in patients who were frequently hospitalised despite an advanced stage of COPD [43]. Half of these patients had no belief in the benefits of vaccinations. In a single-centre study from China, PPSV23 vaccination has shown effective risk-reduction rates in acute exacerbations (54%), pneumonia (53%) and related hospitalisations (46%) in patients with COPD [44]. Combinations with other vaccinations (trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine) improved overall effectiveness for preventions [44]. A cross-sectional study from Thailand evaluated factors influencing the acceptance of pneumococcal vaccination for patients with COPD. The major factors were lack of recommendation, lack of knowledge, misunderstanding and the expense [45]. Significantly higher pneumococcal vaccination coverage was reached among patients who were seeing pulmonologists [45].

The awareness of pneumococcal vaccinations should be improved in physicians and patients with COPD. Consistent recommendations from vaccination committees, medical societies and guidelines can help to overcome the problem of low vaccination rates.

Influenza vaccine

The seasonal influenza pandemic has been a global health burden since 1918, when the first epidemic of influenza caused by the H1N1 virus hit Europe. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that in the US there were up to 41 million symptomatic illnesses and up to 52 000 influenza-caused deaths per year (2017–2018) [46]. Estimates suggest a total of 3–5 million severe infections and up to 600 000 deaths worldwide caused by the seasonal epidemic [47]. However, those numbers do not include the indirectly caused deaths by the virus as influenza can cause critical illness beyond respiratory illness. The host acute phase response to infections can trigger manifestations of chronic diseases through localised and general inflammatory and prothrombotic changes [48, 49], resulting in a rising cardiovascular mortality and morbidity as well as a peaking incidence of acute cardiovascular events during winter. Nearly 12% of hospitalised influenza patients experience an acute cardiovascular event [50, 51]. A recent observational study could show the benefit of early vaccination after myocardial infarction/high-risk coronary heart disease resulting in a lower risk of all-cause and cardiovascular death [52].

Independent of their age, people can be affected by the influenza virus, but some subgroups are more at risk for death and complications than others. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [53], the CDC [46] and the WHO, COPD patients count as population at risk. Internationally, annual influenza vaccination is recommended for some at-risk populations, e.g. patients with chronic pulmonary medical conditions and/or immunosuppressive factors such steroid treatment in COPD [54].

Viral infections are known as a promotor of acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) and during winter the incidence of viral infections in severe AECOPD can be more than 40%, associated with symptoms of rhinopharyngitis, elevated C-reactive protein levels and the use of inhaled corticosteroids. After rhinovirus, the influenza virus was the second most common detected virus (22.5%) causing AECOPD [55]. Mortality in influenza-positive patients is increased by home oxygen use, cardiac comorbidity, age above 75 years and/or residency in a nursing home [56].

The reduction of infections through vaccination reduces the incidence of cardiovascular events. Influenza vaccination shortly after a myocardial infarction or in high-risk coronary heart disease resulted in a lower risk of a composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction or stent thrombosis, and a lower risk of all-cause death and cardiovascular death [52]. These results were confirmed in a meta-analysis from randomised controlled trials [57]. As patients with COPD and patients with coronary heart disease have the same risk factor of a smoking history, the prevention of cardiovascular events by influenza vaccination is important.

Although influenza vaccination is recommended internationally, vaccination rates vary widely around the world and coverage is not optimal [58]. Coverage rates varied from 2% to 72.8% in 2016–2017 with 47.1% for the mentioned season [59]. The highest vaccination coverage rate was reported by the UK with 75%. There is scarcely any proven evidence for the effectiveness of influenza vaccination in COPD. Vaccination coverage among COPD patients differs, but is estimated to be about 62%. Although the protective effect was higher the lower the forced expiratory volume in 1 s was, the prevalence of vaccination falls with the severity of the COPD [60]. Regarding the prevention of influenza-related hospitalisation of patients with COPD, influenza vaccination shows an efficacy of up to 38% and, overall, mortality in influenza-positive patients is high [56]. Lately, a Spanish study showed a moderate average effect of preventing inpatient and outpatient infections. The effect in unvaccinated patients immunised in the prior seasons was 24%. The effectiveness for current-season vaccination, regardless of prior doses, was up to 40% [61]. Unfortunately, the vaccination effectiveness in older COPD patients (>65 years) is probably lower and prevents 22–43% influenza-associated hospitalisations [62]. Vaccination of patients without COPD showed similar effectiveness in preventing hospitalisation, lower respiratory tract infection and CAP [61, 62]. For COPD patients in low- and middle-income countries, the use of an influenza vaccine is cost effective in comparison to no difference in high-income countries [63, 64].

More than 10% of influenza cases in patients with COPD could be prevented by extending vaccination coverage. Patients must be encouraged to get vaccinated to prevent influenza-related hospitalisation and death among COPD patients [56, 61].

Despite motivation and promotion of vaccination among COPD patients, there is room for improvement concerning the vaccines immunologically. VE varies across virus subtypes resulting in mismatches between the composition of the vaccine and the seasonal circulating strains [65].

As mentioned above, older adults experience declining influenza vaccine-induced immunity and are at higher risk of influenza and its complications. For this reason, high-dose and adjuvanted vaccines are preferentially recommended for people aged 65 years and older. The adjuvant MF 59, an oil-in-water emulsion, can be used. This composite has shown to reduce outbreak and hospitalisation rates in vulnerable patients [66, 67]. Secondly, a usual dose of vaccine contains 15 µg hemagglutinin per strain, but increasing the dose of hemagglutinin to 60 µg as a high-dose vaccine was associated with lower infection, pneumonia and hospitalisation rates [68–70]. A comparative analysis of influenza-associated disease burden with the different vaccination strategies (standard-dose versus high-dose versus adjuvanted) in an elderly population in South Korea showed a higher effect with the adjuvanted vaccine in comparison to the standard dose [71]. High-dose and adjuvanted vaccines were expected to be comparable. In an analysis from Germany, adjuvant and high-dose influenza vaccines achieved similar clinically results (hospitalisations, deaths, etc.), but the adjuvant vaccine was more cost saving compared to high-dose vaccine [72]. None of the mentioned studies suggested any clinically relevant changes in safety beyond what is known. Safety and immunogenicity of high-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine administered concomitantly with the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine supported co-administration recommendations [73]. A systematic review led to no recommendations on the preference of one vaccine over another due to the similar effectiveness in preventing seasonal influenza shown in the meta-analysis [74]. The current data situation remains controversial. Future studies comparing the effectiveness of the vaccines are important for future strategies.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, mRNA vaccines were a real game changer in the fight against the virus. Advantages of this technology are the high efficacy rate and the rapid manufacturing process, since a shorter production time may lead to improved strain matching and potentially improving the efficacy of current vaccines. Currently, two clinical trials with mRNA vaccine techniques in phase III from major manufacturers in the US next to several phase I trials promise to improve prophylactic efficacy. Another notion to evade the mismatch between vaccine and viral strains is a newly developed nucleoside-modified mRNA–lipid nanoparticle vaccine encoding hemagglutinin antigens from all 20 known influenza A and B virus subtypes, but further studies will be required to fully evolve this approach [75].

SARS-CoV2 vaccine

The COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic effect, not only on everyday life worldwide, but also on the global health system, prompting significant changes and improvements in the public health infrastructure. In order to limit the spread of the virus, mandatory stay-at-home orders, compulsory facemask usage and the promotion of increased hand hygiene also decreased the incidence of and hospitalisation due to respiratory viral infections other than the SARS-CoV2-virus [76–79]. Simultaneously, there was a 50% reduction in hospital admissions due to AECOPD, most probably by virtue of the overall reduction in respiratory viral infections that trigger acute exacerbations [80]. The strong reduction in hospital admission was significantly higher than for diseases not linked to acute viral respiratory infections. One may conclude an important mechanism in reducing the rate of AECOPD is reducing the threat of viral respiratory infections [76, 77, 80, 81]. This emphasises the need for future clinical management guidelines for all respiratory viral infections and not only for COVID-19.

An infection with SARS-CoV2 represents a particularly serious health threat for COPD patients. Despite the higher risk of healthcare utilisation and both hospital and intensive care unit admission, there was a higher need for mechanical ventilation and an increased mortality rate [82–85].

By the end of 2020, the first COVID-19 vaccines were available internationally. Recommendations for the number of boosters differ for immunocompetent individuals and those who are immunocompromised or at risk of severe illness [86, 87]. Vaccination coverage varies across the world and even within one continent. A total of nearly 70% of the US population has a complete primary series of three doses [88].

Unfortunately, there are no studies investigating the COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness explicitly in COPD patients. At present, there is no data describing the impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the exacerbation rate of COPD.

Two large case-control studies from the US and Israel suggest that mRNA vaccines are highly effective for a wide range of COVID-19-related outcomes in chronically ill patients [89, 90]. Effectiveness was high for preventing symptomatic infection, hospitalisation, severe illness and death in chronically ill people, but the effectiveness decreased in comparison with healthy controls. However, both studies were underpowered to conduct a valid subanalysis and evaluate the vaccination efficacy in COPD patients [89, 90]. Worthy of note is the impaired antibody response after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in chronical medical conditions, as neutralising antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection [91]. Liao et al. [92] found proof of an impaired antibody response in 21% of the study population, of which 80% suffered from a chronical lung disease in general and 3% of the study population were COPD patients, 15% of those were antibody-negative after two doses of mRNA vaccines. One approach to booster the immune status of COPD patients is to improve mucosal immunity. COVID-19 vaccination can induce not only IgG antibodies in plasma, but also IgA responses in the upper airways; however, IgA antibody levels in the upper airways decline over time. Nasally administered vaccine may induce a sustained mucosal IgA response and may offer additional protection for COPD patients [93].

Although COVID vaccines are highly recommended for COPD patients and the need to protect this vulnerable collective is obvious, more definite evidence and data of vaccine effectiveness regarding COPD should be obtained in the future.

HZ Vaccine

The varicella zoster virus (VZV) causes both chickenpox and HZ, commonly known as “shingles” [94]. After an infection with the VZV, the virus remains latent in ganglia and its reactivation causes later HZ [94]. Approximately one third of people suffer from HZ at least once in their lifetime, with an increasing incidence with age. While age counts as the most significant risk factor owing to immunosenescence, reactivation of the latent varicella zoster infection resulting in HZ is more likely in persons with a family history of zoster, immunosuppression and in utero or early infancy primary varicella infection [95]. During the acute infection, patients present painful erythematous vesicles and, as a complication, 10–18% of the patients experience post-herpetic neuralgia [96, 97].

The recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix is recommended for adults 50 years and older as well as adults 18 years and over who are at increased risk of HZ [98, 99]. Zostavax (zoster vaccine live) is no longer available and not recommended because its effectiveness rapidly decreases within 3 years [100, 101]. Shingrix VE in nonimmunocompromised adults reaches 97% [102]. In severely immunocompromised patients such as haematopoietic cell transplant recipients or haematologic malignancies, the VE distributes between 68–90% [103, 104].

The risk of HZ among patients with COPD is increased up to 2.8-fold [105–107]. It is hypothesised that the immune dysregulation found in COPD exhibits a higher risk of developing HZ, amplified by the immunosuppressant effect of inhaled or systemic steroids [94, 106]. There are no data available explicitly showing the VE in COPD patients, but due to their higher risk of HZ we strongly recommend the vaccination for COPD patients, even when younger than 50 years. Patients who develop HZ are at higher risk of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events [108, 109]. Many patients with COPD have also coronary heart disease, which underlines the importance of zoster vaccination in this patient group. A recent case series suggested an association between mRNA COVID-19 vaccination and reactivation of the VZV [110, 111]. In another cohort study with 70 million patients from the US, there was no association between vaccination and an increased rate of VZV reactivation [112].

RSV vaccine

RSV is one of the most important viral pathogens, causing a wide range of illnesses varying from mild upper respiratory tract infections to severe bronchiolitis and pneumonia. Most children are infected in the first 2 years of life, but reinfection may recur throughout life [113, 114]. A 4-year prospective cohort study showed that RSV infection developed in 3–7% of healthy older adults and in 4–10% of high-risk adults [115]. A meta-analysis evaluating the disease burden of RSV–acute respiratory infections (ARIs) worldwide found a global hospital admissions rate of 336 000 hospitalisations (uncertainty range 186 000–614 000) and estimated about 14 000 in-hospital deaths related to RSV-ARI [116]. With an annual incidence between 44.2 and 58.9/100 000 shown in a prospective, population-based, surveillance study to estimate incidence of RSV hospitalisation, RSV-ARI is not a rare viral disease [117]. Reduced RSV-specific T-cell responses in older adults owing to immunosenescence might be responsible for more severe RSV disease in this group [118]. RSV also triggers exacerbations of chronic respiratory disease.

Treatment of RSV-associated illness is supportive and, until recently, there were no licensed vaccines or prophylactic interventions for patients with COPD [119, 120]. The urgent need for safe and effective preventive therapies has led to development of several vaccine candidates. Initial attempts in RSV vaccine development failed in the 1960s. Instead of prevention of RSV infection, the formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine enhanced RSV disease and led to two deaths of infants in a clinical trial [121]. Formalin inactivation might have enhanced the type 2 T-helper cell immune response. Therefore, it is essential to understand the immunological mechanisms underlying the development of enhanced disease. The RSV genome encodes 11 proteins, two of which play a key role for pathogenesis and are important antigens for generating protective immunity. Glycoprotein G is responsible for viral attachment and the fusion protein F mediates for viral penetration and syncytium formation. Two different subtypes of RSV circulate concurrently (A and B). They are distinguished mainly by variations in the G protein [122]. Most RSV vaccine candidates being tested in clinical trials target the RSV F glycoprotein, which mediates viral fusion and host-cell entry, elicits neutralising antibodies and is highly conserved across the two RSV subtypes (A and B) [120, 123].

A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial assessed clinical efficacy, safety and reactogenicity of the recombinant modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA)-RSV vaccine as a viral vector in adults ≥60 years of age (NCT 02873286 Bavarian). Recruitment stopped in December 2022 and this trial is expected to deliver data by 2023. Data from a phase 2a trial showed a lower viral load and symptom score, fewer infections and induced humoral and cellular responses in patients vaccinated with MVA-BN-RSV [124]. The vector-based vaccine Ad26.RSVpreF-RSV is currently being investigated in a randomised controlled trial in older adults (>65 years) (NCT 05035212 Janssen) following a positive phase 2 study with a high VE [125]. The mRNA-based vaccine mRNA-1345 has met primary efficacy end-points in a phase 3 trial in older adults (NCT 05127434 Moderna). VE was 83.7% (95.88% CI 66.1–92.2%; p<0.0001). The study has not yet been completed. Based on these interim results, the manufacturer intends to submit an application for approval in the second half of 2023. A fourth vaccine candidate RSVPreF3 GSK showed consistent high VE, also observed across a range of pre-specified secondary end-points, highlighting the impact the vaccine candidate could have on the populations most at risk of the severe outcomes of RSV (AReSVi-006 trial). Efficacy against severe RSV lower respiratory tract disease (RSV-LRTD), defined as LRTD with at least two lower respiratory signs or assessed as severe by the investigator and confirmed by the external adjudication committee, was 94.1%. In participants with pre-existing comorbidities, such as underlying cardiorespiratory and endocrinometabolic conditions, VE was 94.6% with 93.8% efficacy observed in adults aged 70–79 years. VE against LRTD was consistent across both RSV-A and RSV-B subtypes, consistent with the robust neutralising antibody response generated against both subtypes [126]. The last RSV candidate is a protein-based vaccine with genetically engineered pre-fusion RSV F protein of virus subgroups A and B as antigens. It showed a high efficacy in older adults in the recently published intirim analysis of the phase 3 study [127]. The approval was recommended by the European Medicines Agency in July 2023 [126]. All RSV vaccine candidates are summarised in table 2.

TABLE 2.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines in phase III clinical trials, in the approval process in older patients

| Manufacturer | Name | Vaccine type | Target group | Development status |

| Bavarian Nordic | MVA-BN RSV | Vector vaccine that produces five antigens from virus subtypes A and B, including RSV F and RSV G | Adults ≥60 years | Phase III |

| GSK | RSVPreF3 | Protein-based vaccine with genetically engineered antigen protein and adjuvant | Adults ≥60 years | FDA approval May 2023, European Commission approval June 2023 |

| Janssen | Ad26.RSV.preF-RSV | Vector vaccine resulting in production of pre-fusion RSV F protein | Adults ≥65 years | Phase III |

| Moderna | mRNA-1345 | mRNA vaccine leading to the production of pre-fusion RSV F protein | Adults ≥60 years | Phase III, intended for submission for approval in the second half of 2023 |

| Pfizer | RSV.preF | Protein-based vaccine, bivalent, with genetically engineered pre-fusion RSV F protein of virus subgroups A and B as antigens | Adults ≥60 years | Phase III, approval recommended by EMA in July 2023 |

EMA: European Medicines Agency; FDA: United States Food and Drug Administration; MVA: modified vaccinia Ankara.

Patients with COPD were not excluded in the presented studies, but there were no safety concerns in this patient population. Seasonal respiratory viral infections among hospitalised patients with COPD are associated with a 50% increase in the likelihood of intensive care unit admission and a 90% increase in the likelihood of mechanical ventilation [128]. RSV is an important pathogen in this vulnerable population and the new vaccines provide hope for a better protection. Differences between the vaccines will become apparent over time.

Pertussis vaccine

Pertussis, caused by Bordetealla pertussis, is a contagious respiratory infection characterised by prolonged cough lasting many weeks. Typical clinical factors are paroxysmal cough, inspiratory whooping, post-tussive vomiting and the absence of fever [129]. The clinical presentation of pertussis in adults is often atypical, with fewer patients demonstrating inspiratory whoop. Epidemiological data from the US have shown a trend towards an increasing proportion of pertussis cases in adults [130]. This has been attributed to waning immunity especially in vaccines from the 1990s and neither vaccination nor immunisation via previous infection provide life-long protection [131]. Furthermore, inconsistent recommendations related to booster strategies in adults and declining vaccination rates in children has led to a rising incidence of pertussis. The first generation of pertussis vaccine consisted of an inactivated and detoxified whole-cell pathogen. To reduce the rate of post-vaccination adverse events, a switch was made by the 1990s to the use of an acellular pertussis vaccine [132]. However, epidemiological data collected over the past few decades show an increase in pertussis and it has become a typical infection in adults [133].

COPD may increase the risk and severity of pertussis infection. In a retrospective cohort study from the UK, the incidence of pertussis among individuals aged ≥50 years with COPD was assessed from Clinical Practice Research Datalink and Hospital Episode Statistics databases during 2009–2018 [134]. COPD patients had a 2.32-fold higher risk of contracting pertussis resulted in significant increases in healthcare resource utilisation and direct medical costs around the pertussis event [134, 135]. New and immunologically improved vaccines will be expected in the next few years.

Haemophilus influenzae

Chronic infections with nontypeable H. influenzae correlate with a loss of airway microbial diversity and with a higher disease severity and exacerbation rate in patients with COPD [136]. In contrast to H. influenzae type B infections in childhood, nontypeable H. influenzae plays a role in older and in COPD patients. No attempts to develop reliable vaccines have been successful so far. In 2022, a study to assess the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of a candidate vaccine containing surface proteins from nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi) and Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat) in patients with COPD were published [137]. In this multicentre, randomised phase 2b trial, the NTHi-Mcat vaccine did not show efficacy in reducing the yearly rate of moderate or severe exacerbations. The primary end-point was negative but a number of secondary end-points including immune response were positive. Since H. influenzae is one of the most important bacterial triggers of an exacerbation in this patient group, it is an important area of research for the future. In addition, data suggests a shift in the pathogen spectrum of CAP towards (nontypeable) H. influenza [138, 139]. Therefore, a vaccine is urgently needed.

Vaccination strategies

Vaccines are regarded as one of the most effective preventative measures in modern medicine. All patients with COPD should be vaccinated against influenza, pneumococcus, COVID-19, pertussis and HZ, if they have not already received these vaccinations. Table 3 summarises the currently licensed vaccines, as well as their indication, efficacy and side-effects. Vaccination rates in COPD patients are mostly far behind the recommended strategies. Patients and resident doctors often complain about lack of recommendation, knowledge, misunderstandings and high expense. Official recommendations vary from country to country and sometimes from region to region. A periodic assessment of practice performance could help to evaluate adherence rates to recommended vaccines. It would have the advantage of measuring adherence to standards of care, identifying barriers to vaccination, developing strategies for improving vaccination adherence and optimising vaccine delivery to targeted patients. In order to improve vaccination coverage, we need easier tools and better education to inform and motivate treating physicians.

TABLE 3.

Licensed vaccines for pneumococcal, influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and herpes zoster with different indications, efficacy, prevention of exacerbations and side-effects

| Vaccine | Vaccine type | Indication | Vaccine efficacy | Prevention of COPD exacerbations | Side-effects |

| PPSV23 | Polysaccharide-based vaccine | Pneumococcus | 45% PPSV23-type IPD [140] | By year 5: 47% PPSV23 versus 82% placebo [29] | Injection-site redness and pain Tiredness Fever Muscle aches |

| PCV13 | Conjugate vaccine | Pneumococcus | 47–68% PCV13-type IPD (≥65 years) [140] | By year 5: 3.3% PCV13 versus 82% placebo [29] | Injection-site redness, swelling, pain and |

| PCV15 | Conjugate vaccine | Pneumococcus | Not available | Not available | tenderness |

| PCV20 | Conjugate vaccine | Pneumococcus | Not available | Not available | Loss of appetite Irritability Headache Muscle aches or joint pain Chills |

| HD QIV | High-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine | Influenza | 24.2% (≥65 years) compared to standard dose [141] | Meta-analysis for different influenza vaccine types: significant reduction in exacerbations (p<0.001) [142] | Injection-site pain Muscle pain Malaises Headache Rare: fainting, dizziness, vision changes, ear ringing |

| aQIV | MF59-adjuvanted quadrivalent vaccine | Influenza | 24–63% (≥65 years), 3.2% compared to HD QIV [143] | Mild pain Tenderness Fatigue Myalgia |

|

| BNT162b2 | mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 | 96% (no chronic medical conditions), 83% (≥3 conditions) [89] | Not available | Injection-site pain Fatigue Headache New or worsened muscle pain Fever |

| mRNA-1273 | mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 | 86.4% (≥65 years) [144] | Not available | Injection-site pain, axillary swelling, redness Irritability/crying Fatigue Fever |

| RZV | Adjuvanted recombinant subunit vaccine | Herpes zoster | 97% [102] | Not available | Injection-site pain, redness, swelling Fatigue Headache Muscle pain Chills Fever Rare: allergic reactions, Guillain-Barré syndrome, meningitis, encephalitis |

aQIV: adjuvanted quadrivalent influenza vaccine; HD QIV: high-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine; IPD: invasive pneumococcal disease; PCV: pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PPSV: pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; RZV: recombinant zoster vaccine.

Conclusion

Chronic diseases in general and COPD in particular challenge health systems worldwide. Vaccination can effectively reduce the risk of exacerbations, pneumonia and related hospitalisation. Respiratory pathogens can also occur as a mixed infection with a higher mortality [10, 145]. Therefore, vaccination can help to prevent mixed infections even against pathogens not included in the vaccine [146]. Despite the high morbidity and mortality of pneumococcal disease in COPD patients, vaccination coverage rates remain far below the WHO's recommended targets. Patients with COPD at all ages should receive the presented vaccinations. Primarily due to vaccine developments during the COVID-19 pandemic, research in this area has increased significantly. New vaccine technologies will lead to even better effects in the future.

From the authors’ point of view, the vaccination status of COPD patients should be checked once a year. Vaccinations against influenza, pneumococci, SARS-CoV-2 and HZ are among the recommended vaccinations. With the tetanus/diphtheria vaccine recommended every 10 years for other reasons, a triple vaccine (including pertussis booster) or even a quadruple vaccine (plus polio) should be preferred.

Points for clinical practice

Infectious disease prevention through immunisation is a cornerstone prophylactic measure against exacerbations but there is much room for improvement.

- Expert opinion: in addition to standard vaccinations, all COPD patients should be vaccinated by:

- - a yearly high-dose or adjuvanted quadrivalent influenza vaccine

- - a single-dose PCV20

- - two doses of recombinant zoster vaccine

- - basic immunisation and booster against SARS-CoV2 by mRNA vaccines.

Awareness of vaccinations should be improved in physicians and patients with COPD.

Footnotes

Provenance: Commissioned article, peer reviewed.

Previous articles in this series: No. 1: Montes de Oca M, Laucho-Contreras ME. Smoking cessation and vaccination. Eur Respir Rev 2023; 32: 220187. No. 2: Volpato E, Farver-Vestergaard I, Brighton LJ, et al. Nonpharmacological management of psychological distress in people with COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2023; 32: 220170. No. 3: Owens RL, Derom E, Ambrosino N. Supplemental oxygen and noninvasive ventilation. Eur Respir Rev 2023; 32: 220159. No. 4: Verleden GM, Gottlieb J. Lung transplantation for COPD/pulmonary emphysema. Eur Respir Rev 2023; 32: 220116. No. 5: Troosters T, Janssens W, Demeyer H, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation and physical interventions. Eur Respir Rev 2023; 32: 220222. No. 5: Troosters T, Janssens W, Demeyer H, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation and physical interventions. Eur Respir Rev 2023; 32: 220222. No. 6: Beijers RJHCG, Steiner MC, Schols AMWJ. The role of diet and nutrition in the management of COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2023; 32: 220003.

Number 7 in the Series “Non-pharmacological interventions in COPD: state of the art and future directions” Edited by Geert M. Verleden and Wim Janssens

Conflict of interest: T. Welte reports support for the present manuscript from German Ministry of Research and Education; grants or contracts from Bavaria Nordisk, outside the submitted work; payment or honoraria from Janssen, GSK, MSD and Pfizer, outside the submitted work; and is a current editorial board member for European Respiratory Review. J. Rademacher reports receiving payment or honoraria from GSK and MSD, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Support statement: Supported by the German Center of Lung Research. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.McLean S, Hoogendoorn M, Hoogenveen RT, et al. Projecting the COPD population and costs in England and Scotland: 2011 to 2030. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 31893. doi: 10.1038/srep31893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aka Aktürk Ü, Dilektasli AG, Sengul A, et al. Influenza and pneumonia vaccination rates and factors affecting vaccination among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Balk Med J 2017; 34: 206–211. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.2016.1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wedzicha JA, Singh R, Mackay AJ. Acute COPD exacerbations. Clin Chest Med 2014; 35: 157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A,et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan M, McDonnell MJ, Harrison MJ,et al. Antimicrobial therapies for prevention of recurrent acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD): beyond the guidelines. Respir Res 2022; 23: 58. doi: 10.1186/s12931-022-01947-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shea KM, Edelsberg J, Weycker D, et al. Rates of pneumococcal disease in adults with chronic medical conditions. Open Forum Infect Dis 2014; 1: ofu024. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perotin J-M, Dury S, Renois F, et al. Detection of multiple viral and bacterial infections in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot prospective study. J Med Virol 2013; 85: 866–873. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkinson TMA, Aris E, Bourne S, et al. A prospective, observational cohort study of the seasonal dynamics of airway pathogens in the aetiology of exacerbations in COPD. Thorax 2017; 72: 919–927. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dähne T, Bauer W, Essig A, et al. The impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the prevalence of respiratory tract pathogens in patients with community-acquired pneumonia in Germany. Emerg Microbes Infect 2021; 10: 1515–1518. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1957402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ankert J, Hagel S, Schwarz C, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae re-emerges as a cause of community-acquired pneumonia, including frequent co-infection with SARS-CoV-2, in Germany, 2021. ERJ Open Res 2023; 9: 00703-02022. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00703-2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yahiaoui RY, den Heijer CDj, van Bijnen EM, et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of commensal Streptococcus pneumoniae in nine European countries. Future Microbiol 2016; 11: 737–744. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2015-0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392: 1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bornheimer R, Shea KM, Sato R, et al. Risk of exacerbation following pneumonia in adults with heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0184877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venkatesan P. GOLD COPD report: 2023 update. Lancet Respir Med 2023; 11: 18. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00494-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clutterbuck EA, Lazarus R, Yu LM, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate and plain polysaccharide vaccines have divergent effects on antigen-specific B cells. J Infect Dis 2012; 205: 1408–1416. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews NJ, Waight PA, George RC, et al. Impact and effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly in England and Wales. Vaccine 2012; 30: 6802–6808. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Artz AS, Ershler WB, Longo DL. Pneumococcal vaccination and revaccination of older adults. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003; 16: 308–318. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.308-318.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walters JA, Smith S, Poole P, et al. Injectable vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 2010: CD001390. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001390.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard AJ, Perrett KP, Beverley PC. Maintaining protection against invasive bacteria with protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9: 213–220. doi: 10.1038/nri2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonten MJM, Huijts SM, Bolkenbaas M, et al. Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1114–1125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forstner C, Kolditz M, Kesselmeier M, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate serotype distribution and predominating role of serotype 3 in German adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Vaccine 2020; 38: 1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeBlanc JJ, ElSherif M, Ye L, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 3 is masking PCV13-mediated herd immunity in Canadian adults hospitalized with community acquired pneumonia: a study from the Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network of the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN). Vaccine 2019; 37: 5466–5473. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sikjær MG, Pedersen AA, Wik MS, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of the pneumococcal polysaccharide and conjugated vaccines in elderly and high-risk populations in preventing invasive pneumococcal disease: a systematic search and meta-analysis. Eur Clin Respir J 2023; 10: 2168354. doi: 10.1080/20018525.2023.2168354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Djennad A, Ramsay ME, Pebody R, et al. Effectiveness of 23-valent polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine and changes in invasive pneumococcal disease incidence from 2000 to 2017 in those aged 65 and over in England and Wales. EClinicalMedicine 2018; 6: 42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leventer-Roberts M, Feldman BS, Brufman I, et al. Effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against invasive disease and hospital-treated pneumonia among people aged ≥65 years: a retrospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60: 1472–1480. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heo JY, Seo YB, Choi WS, et al. Effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination against pneumococcal pneumonia hospitalization in older adults: a prospective, test-negative study. J Infect Dis 2022; 225: 836–845. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunne EM, Cilloniz C, von Mollendorf C, et al. Pneumococcal vaccination in adults: what can we learn from observational studies that evaluated PCV13 and PPV23 effectiveness in the same population? Arch Bronconeumol 2023; 59: 157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2022.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azuma M, Oishi K, Akeda Y, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of sequential administration of PCV13 followed by PPSV23 in pneumococcal vaccine-naïve adults aged ≥65 years: comparison of booster effects based on intervals of 0.5 and 1.0 year. Vaccine 2023; 41: 1042–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.12.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ignatova GL, Avdeev SN, Antonov VN. Comparative effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination with PPV23 and PCV13 in COPD patients over a 5-year follow-up cohort study. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 15948. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95129-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang L, Wasserman M, Grant L, et al. Burden of pneumococcal disease due to serotypes covered by the 13-valent and new higher-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in the United States. Vaccine 2022; 40: 4700–4708. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ladhani SN, Collins S, Djennad A, et al. Rapid increase in non-vaccine serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales, 2000–17: a prospective national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 441–451. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30052-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouldali N, Varon E, Levy C, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease incidence in children and adults in France during the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era: an interrupted time-series analysis of data from a 17-year national prospective surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21: 137–147. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30165-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiley KS, Ratcliffe H, Voysey M, et al. Nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococcus in children in England up to ten years after PCV13 introduction: persistence of serotypes 3 and 19A and emergence of 7C. J Infect Dis 2022; 227: jiac376. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahrs C, Kesselmeier M, Kolditz M, et al. A longitudinal analysis of pneumococcal vaccine serotypes in pneumonia patients in Germany. Eur Respir J 2022; 59: 2102432. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02432-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Essink B, Sabharwal C, Cannon K, et al. Pivotal phase 3 randomized clinical trial of the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults aged ≥18 years. Clin Infect 2022; 75: 390–398. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klein NP, Peyrani P, Yacisin K, et al. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of 3 lots of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults 18 through 49 years of age. Vaccine 2021; 39: 5428–5435. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cannon K, Elder C, Young M, et al. A trial to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in populations of adults ≥65 years of age with different prior pneumococcal vaccination. Vaccine 2021; 39: 7494–7502. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen J, Schnack H, Skovdal M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Denmark compared with PPV23. J Med Econ 2022; 25: 1240–1254. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2022.2152235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mendes D, Averin A, Atwood M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of using a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to directly protect adults in England at elevated risk of pneumococcal disease. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2022; 22: 1285–1295. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2022.2134120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Platt H, Omole T, Cardona J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a 21-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, V116, in healthy adults: phase 1/2, randomised, double-blind, active comparator-controlled, multicentre, US-based trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2023; 23: 233–246. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00526-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohr A, Kloos M, Schulz C, et al. Low adherence to pneumococcal vaccination in lung cancer patients in a tertiary care university hospital in southern Germany. Vaccines 2022; 10: 311. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gogou E, Hatzoglou C, Zarogiannis SG, et al. Are younger COPD patients adequately vaccinated for influenza and pneumococcus? Respir Med 2022; 203: 106988. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Candemir I, Turk S, Ergun P, et al. Influenza and pneumonia vaccination rates in patients hospitalized with acute respiratory failure. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2019; 15: 2606–2611. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1613128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y, Zhang P, An Z, et al. Effectiveness of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Respirol Carlton Vic 2022; 27: 844–853. doi: 10.1111/resp.14309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saiphoklang N, Phadungwatthanachai J. Factors influencing acceptance of influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2022; 18: 2102840. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2102840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . People at higher risk of flu complications. Date last accessed: 9 August 2023. Date last updated: 6 September 2022. www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/index.htm

- 47.Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet 2018; 391: 1285–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Macias AE, McElhaney JE, Chaves SS, et al. The disease burden of influenza beyond respiratory illness. Vaccine 2021; 39: Suppl. 1, A6–A14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fischer WA, Gong M, Bhagwanjee S, et al. Global burden of influenza as a cause of cardiopulmonary morbidity and mortality. Glob Heart. 2014; 9: 325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen JL, Yang W, Ito K, et al. Seasonal influenza infections and cardiovascular disease mortality. JAMA Cardiol 2016; 1: 274–281. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chow EJ, Rolfes MA, O'Halloran A, et al. Acute cardiovascular events associated with influenza in hospitalized adults: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173: 605–613. doi: 10.7326/M20-1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fröbert O, Götberg M, Erlinge D, et al. Influenza vaccination after myocardial infarction: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Circulation 2021; 144: 1476–1484. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Risk groups for severe influenza. Date last accessed: 9 August 2023. Date last updated: 9 March 2023. www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/prevention-and-control/vaccines/risk-groups

- 54.World Health Organization . Influenza (seasonal). Date last updated: 12 January 2023. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal)

- 55.Jang JG, Ahn JH, Jin HJ. Incidence and prognostic factors of respiratory viral infections in severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2021; 16: 1265–1273. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S306916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mulpuru S, Li L, Ye L, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination on hospitalizations and risk factors for severe outcomes in hospitalized patients with COPD. Chest 2019; 155: 69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jaiswal V, Ang SP, Yaqoob S, et al. Cardioprotective effects of influenza vaccination among patients with established cardiovascular disease or at high cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022; 29: 1881–1892. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwac152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . Influenza vaccination rates. Date last accessed: 9 August 2023. Date last updated: 2022. https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/influenza-vaccination-rates.htm

- 59.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Seasonal influenza. Date last accessed: 9 August 2023. Date last updated: 7 July 2023. www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza

- 60.Garrastazu R, García-Rivero JL, Ruiz M, et al. Prevalence of influenza vaccination in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and impact on the risk of severe exacerbations. Arch Bronconeumol 2016; 52: 88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martínez-Baz I, Casado I, Navascués A, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and influenza vaccination effect in preventing outpatient and inpatient influenza cases. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 4862. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08952-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gershon AS, Chung H, Porter J, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalizations in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis 2020; 221: 42–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lall D, Cason E, Pasquel FJ, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination for individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in low- and middle-income countries. COPD 2016; 13: 93–99. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2015.1043518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ott JJ, Breteler JK, Tam JS, et al. Influenza vaccines in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2013; 9: 1500–1511. doi: 10.4161/hv.24704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP, et al. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16: 942–951. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00129-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gravenstein S, McConeghy KW, Saade E, et al. Adjuvanted influenza vaccine and influenza outbreaks in US nursing homes: results from a pragmatic cluster-randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: e4229–e4236. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McConeghy KW, Davidson HE, Canaday DH, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of adjuvanted versus nonadjuvanted trivalent influenza vaccine in 823 US nursing homes. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: e4237–e4243. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paudel M, Mahmud S, Buikema A, et al. Relative vaccine efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines in preventing probable influenza in a Medicare Fee-for-Service population. Vaccine 2020; 38: 4548–4556. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balasubramani GK, Choi WS, Nowalk MP, et al. Relative effectiveness of high dose versus standard dose influenza vaccines in older adult outpatients over four seasons, 2015–16 to 2018–19. Vaccine 2020; 38: 6562–6569. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee JKH, Lam GKL, Shin T, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccination for older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Vaccines 2018; 17: 435–443. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1471989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Choi MJ, Yun JW, Song JY, et al. A comparative analysis of influenza-associated disease burden with different influenza vaccination strategies for the elderly population in South Korea. Vaccines 2022; 10: 1387. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10091387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kohli MA, Maschio M, Cartier S, et al. The cost-effectiveness of vaccination of older adults with an mf59-adjuvanted quadrivalent influenza vaccine compared to other available quadrivalent vaccines in Germany. Vaccines 2022; 10: 1386. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10091386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Izikson R, Brune D, Bolduc JS, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a high-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine administered concomitantly with a third dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in adults aged ≥65 years: a phase 2, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10: 392–402. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00557-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Domnich A, de Waure C. Comparative effectiveness of adjuvanted versus high-dose seasonal influenza vaccines for older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2022; 122: 855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arevalo CP, Bolton MJ, Le Sage V, et al. A multivalent nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine against all known influenza virus subtypes. Science 2022; 378: 899–904. doi: 10.1126/science.abm0271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.So JY, O'Hara NN, Kenaa B, et al. Population decline in COPD admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic associated with lower burden of community respiratory viral infections. Am J Med 2021; 134: 1252–1259.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huh K, Kim YE, Ji W, et al. Decrease in hospital admissions for respiratory diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide claims study. Thorax 2021; 76: 939–941. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tan JY, Conceicao EP, Sim XYJ, et al. Public health measures during COVID-19 pandemic reduced hospital admissions for community respiratory viral infections. J Hosp Infect 2020; 106: 387–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Joean O, Welte T. Vaccination and modern management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a narrative review. Expert Rev Respir Med 2022; 16: 605–614. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2022.2092099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alqahtani JS, Oyelade T, Aldhahir AM, et al. Reduction in hospitalised COPD exacerbations during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0255659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.González J, Moncusí-Moix A, Benitez ID, et al. Clinical consequences of COVID-19 lockdown in patients with COPD: results of a pre-post study in Spain. Chest 2021; 160: 135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.12.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guan W, Liang WH, Zhao Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 2000547. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Attaway AA, Zein J, Hatipoğlu US. SARS-CoV-2 infection in the COPD population is associated with increased healthcare utilization: an analysis of Cleveland clinic's COVID-19 registry. eClinicalMedicine 2020; 26: 100515. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meza D, Khuder B, Bailey JI, et al. Mortality from COVID-19 in patients with COPD: a US study in the N3C data enclave. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2021; 16: 2323–2326. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S318000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beltramo G, Cottenet J, Mariet AS, et al. Chronic respiratory diseases are predictors of severe outcome in COVID-19 hospitalised patients: a nationwide study. Eur Respir J 2021; 58: 2004474. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04474-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Date last accessed: 9 August 2023. Date last updated: 12 May 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/interim-considerations-us.html

- 87.Robert Koch Institut . COVID-19-Impfempfehlung. Date last updated: 20 June 2023. www.rki.de/SharedDocs/FAQ/COVID-Impfen/FAQ_Liste_STIKO_Empfehlungen.html

- 88.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID data tracker. Date last accessed: 9 August 2023. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- 89.Lewis NM, Naioti EA, Self WH, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 hospitalization by age and chronic medical conditions burden among immunocompetent US adults, March–August 2021. J Infect Dis 2021; 225: 1694–1700. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1412–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 2021; 27: 1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liao S-Y, Gerber AN, Zelarney P, et al. Impaired SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine antibody response in chronic medical conditions. Chest 2022; 161: 1490–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.12.654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Southworth T, Jackson N, Singh D. Airway immune responses to COVID-19 vaccination in COPD patients and healthy subjects. Eur Respir J 2022; 60: 2200497. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00497-2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hambleton S, Gershon AA. Preventing varicella-zoster disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005; 18: 70–80. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.70-80.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cohen JI. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 255–263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1302674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Shingles burden and trends. Date last accessed: 9 August 2023. Date last updated: 10 May 2023. www.cdc.gov/shingles/surveillance.html

- 97.Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, et al. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82: 1341–1349. doi: 10.4065/82.11.1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.European Medicines Agency . Shingrix. Date last updated: 19 December 2022. www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/shingrix.

- 99.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Vaccination. Date last updated: 24 January 2022. www.cdc.gov/shingles/vaccination.html

- 100.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . What everyone should know about Zostavax. Date last accessed: 9 August 2023. Date last updated: 5 October 2020. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/public/zostavax/index.html

- 101.Dooling K, Guo A, Leung J, et al. Performance of zoster vaccine live (Zostavax): a systematic review of 12 years of experimental and observational evidence. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4: S412–S413. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx163.1033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lal H, Cunningham AL, Godeaux O, et al. Efficacy of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2087–2096. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bastidas A, de la Serna J, El Idrissi M, et al. Effect of recombinant zoster vaccine on incidence of herpes zoster after autologous stem cell transplantation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019; 322: 123–133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dagnew AF, Ilhan O, Lee WS, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine in adults with haematological malignancies: a phase 3, randomised, clinical trial and post-hoc efficacy analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19: 988–1000. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thompson-Leduc P, Ghaswalla P, Cheng WY, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster: a retrospective United States claims database analysis. Clin Respir J 2022; 16: 826–834. doi: 10.1111/crj.13554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yang Y-W, Chen Y-H, Wang K-H, et al. Risk of herpes zoster among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based study. CMAJ 2011; 183: E275–E280. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Muñoz-Quiles C, López-Lacort M, Díez-Domingo J. Risk and impact of herpes zoster among COPD patients: a population-based study, 2009–2014. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18: 203. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3121-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Erskine N, Tran H, Levin L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on herpes zoster and the risk of cardiac and cerebrovascular events. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0181565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Parameswaran GI, Drye AF, Wattengel BA, et al. Increased myocardial infarction risk following herpes zoster infection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023; 10: ofad137. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofad137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Furer V, Zisman D, Kibari A, et al. Herpes zoster following BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases: a case series. Rheumatol 2021; 60: SI90–SI95. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Chicharro P, Cabrera L-M, et al. Varicella-zoster virus reactivation after SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination: report of 5 cases. JAAD Case Rep 2021; 12: 58–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Birabaharan M, Kaelber DC, Karris MY. Risk of herpes zoster reactivation after messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccination: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022; 87: 649–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Borchers AT, Chang C, Gershwin ME, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus–a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2013; 45: 331–379. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8368-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nam HH, Ison MG. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. BMJ 2019; 366: l5021. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1749–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shi T, Denouel A, Tietjen AK, et al. Global disease burden estimates of respiratory syncytial virus-associated acute respiratory infection in older adults in 2015: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis 2020; 222: S577–S583. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Branche AR, Saiman L, Walsh EE, et al. Incidence of respiratory syncytial virus infection among hospitalized adults, 2017–2020. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 74: 1004–1011. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cherukuri A, Patton K, Gasser RA Jr, et al. Adults 65 years old and older have reduced numbers of functional memory T cells to respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2013; 20: 239–247. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00580-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Domachowske JB, Anderson EJ, Goldstein M. The future of respiratory syncytial virus disease prevention and treatment. Infect Dis Ther 2021; 10: 47–60. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00383-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stephens LM, Varga SM. Considerations for a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine targeting an elderly population. Vaccines 2021; 9: 624. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kim HW, Canchola JG, Brandt CD, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol 1969; 89: 422–434. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hall CB. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1917–1928. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106213442507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mazur NI, Higgins D, Nunes MC, et al. The respiratory syncytial virus vaccine landscape: lessons from the graveyard and promising candidates. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: e295–e311. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30292-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Jordan E, Kabir G, Schultz S, et al. Reduced respiratory syncytial virus load, symptoms, and infections: a human challenge trial of MVA-BN-RSV vaccine. J Infect Dis 2023; in press [ 10.1093/infdis/jiad108] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Falsey AR, Williams K, Gymnopoulou E, et al. Efficacy and safety of an Ad26.RSV.preF–RSV preF protein vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2023; 388: 609–620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Papi A, Ison MG, Langley JM, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 595–608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2209604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Schmoele-Thoma B, Zareba AM, Jiang Q, et al. Vaccine efficacy in adults in a respiratory syncytial virus challenge study. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 2377–2386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mulpuru S, Andrew MK, Ye L, et al. Impact of respiratory viral infections on mortality and critical illness among hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2022; 16: 1172–1182. doi: 10.1111/irv.13050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]