Abstract

Background

The guidelines recommend laparoscopic repair for bilateral inguinal hernia. However, few studies compare the totally extraperitoneal (TEP) and transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) techniques in bilateral inguinal hernias. This study aimed to compare the outcomes of TEP and TAPP in bilateral inguinal hernia.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients operated on for bilateral inguinal hernia by TEP and TAPP repair from 2016 to 2020. Intraoperative complications, operative time, acute postoperative pain, hospital stay, postoperative complications, chronic inguinal pain, and recurrence were compared.

Results

A total of 155 patients were included in the study. TEP was performed in 71 patients (46%) and TAPP in 84 patients (54%). The mean operative time was longer in the TAPP group than in the TEP group (107 min vs. 82 min, p < 0.001). The conversion rate to open surgery was higher in the TEP group than in the TAPP group (8.5% vs. 0%, p = 0.008). The mean hospital stay was longer in the TAPP group than in the TEP group (p < 0.001). We did not observe significant differences in the proportion of postoperative complications (p = 0.672), postoperative pain at 24 h (p = 0.851), chronic groin pain (p = 0.593), and recurrence (p = 0.471). We did not observe an association between the choice of surgical technique (TEP vs. TAPP) with conversion rate, operative time, hospital stay, postoperative complications, chronic inguinal pain, or hernia recurrence when performing a multivariable analysis adjusted for the male sex, age, BMI, ASA, recurrent hernia repair, surgeon, and hernia size > 3cm.

Conclusions

Bilateral inguinal hernia repair by TEP and TAP presented similar outcomes in our study.

Keywords: Bilateral inguinal hernia, Laparoscopic, Totally extraperitoneal, Transabdominal preperitoneal

Introduction

Inguinal hernia occurs in 1 to 5% of the general population, they comprise 75% of all abdominal wall hernias [1], and their repair is one of the most performed surgical procedures [2]. Inguinal hernia surgery remains one of the greatest challenges in surgical pathology due to its high frequency and the socioeconomic consequences of even minor complications.

The development of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair techniques as an alternative to conventional open surgery has improved results such as less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery [3, 4]. Some meta-analyses have also shown a lower incidence of chronic pain [5, 6]. One of the reasons for the lower postoperative pain would be the lower rate of complications described in the laparoscopic approach [7]. Randomized trials have found no difference in the recurrence rate between the laparoscopic and open approaches [8, 9].

Studies examining the costs of laparoscopic inguinal hernia compared to a conventional open repair show a higher cost of laparoscopic repair [10, 11]. However, from a socioeconomic perspective and considering the quality-of-life analyses, a laparoscopic procedure is probably the most cost-effective approach for patients in the labor market, especially for bilateral hernias [12].

International guidelines recommend laparoscopic repair for bilateral inguinal hernia [13–16]. The advantage of the laparoscopic approach over the open technique is its ability to address both groins through the same incisions required for unilateral hernia repair. Furthermore, laparoscopy represents a cost-effective procedure compared to the open repair of bilateral inguinal hernia [17].

The most used laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair are totally extraperitoneal (TEP) and transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) [18, 19]. In recent decades, many studies have been performed comparing both laparoscopic approaches with conflicting results. Most previous randomized trials and meta-analyses did not report significant differences in outcomes such as total complications, time back to work, or recurrence rate [20–23]. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis showed less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays in TEP repair, and shorter duration of surgery in TAPP repair [24]. However, these results were based on studies of unilateral inguinal hernias. Currently, few studies compare the two procedures in bilateral inguinal hernia.

This study aims to evaluate the outcomes of TEP and TAPP in bilateral inguinal hernia repair in our hospital and to compare the intraoperative complications, operative time, acute postoperative pain, hospital stay, postoperative complications, chronic inguinal pain, and hernia recurrence.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients who underwent bilateral inguinal hernia repair at the Hospital Clinic Barcelona, Spain, a tertiary hospital. Data were obtained by reviewing computerized medical records. The transition from open inguinal hernia repair to laparoscopic repair in our hospital began in 2016.

Study population

Inclusion criteria: patients who underwent bilateral inguinal hernia repair by laparoscopic approach from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2020. Exclusion criteria: emergency surgeries, patients without a postoperative follow-up of at least one year, and patients with incomplete data.

Groups to analyze

The participants in our study were divided into two groups based on the laparoscopic technique used: the TEP group and the TAPP group. Two separate teams performed the procedures. One of the teams, made up of two surgeons, used the TEP technique during the research period, while the other team, made up of three surgeons, used the TAPP approach. At the beginning of our study, the surgeons on both teams had previous experience in laparoscopic surgery but no previous experience in laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery.

Totally extraperitoneal technique

An infra-umbilical incision was made up to the opening of the anterior rectus muscle fascia. The anterior rectus muscle was retracted laterally to access the retro muscular space. A balloon trocar was introduced to dissect the retro muscular space until accessing the preperitoneal space, and subsequently, an 11-mm trocar was introduced for a 30-degree laparoscopy camera. An 11-mm trocar and a 5-mm trocar were introduced as working ports in the sub-umbilical midline. Cooper's ligament was exposed, and the peritoneum of the direct or indirect hernia sac was reduced, identifying the spermatic duct or round ligament and gonadal vein, and total exposure of the myopectineal orifice was achieved. A 10 × 15 cm self-adhesive polypropylene mesh was placed. The same procedure was performed for the contralateral hernia.

Transabdominal preperitoneal technique

Pneumoperitoneum was performed using a Veress needle inserted through a supraumbilical incision. Three trocars were introduced: an 11-mm supraumbilical trocar for the 30-degree laparoscopy camera, an 11-mm trocar on the right flank, and a 5-mm trocar on the left flank as working ports. An incision was made in the peritoneum from the level of the iliac crest to the inguinal ligament. Cooper's ligament was exposed, direct or indirect hernial sac was reduced, identifying the spermatic duct or round ligament and gonadal vein, and total exposure of the myopectineal orifice was achieved. In large direct hernias, seroma prophylaxis was performed with fixation of the redundant transversalis fascia with a 00 barbed suture. A polypropylene mesh of a minimum size of 12 × 15 cm was placed and fixed with tissue adhesive. The closure of the peritoneum was performed with 00 absorbable barbed suture. The same procedure was performed for the contralateral hernia.

Variables analyzed

We collected patient demographics such as age, gender, and body mass index (BMI). Also, previous comorbidities such as arterial hypertension, heart disease, chronic lung disease, kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes, obesity, smoking history, and lower abdominal surgery were collected. The ASA (American Society of Anaesthesiologists) classification quantified the anesthetic risk.

The hernia characteristics analyzed were the pre-surgical clinical or radiological diagnosis of recurrent hernia. The size of the hernia collected is according to the classification of the European Hernia Society, which classifies hernias into three grades: grade I (< 1.5 cm), grade II (1.5 -3 cm), and grade III (> 3 cm). In our study, we defined hernia size considering the side with the largest hernia according to the finding during surgery.

We also collected the proportion of patients who underwent day surgery, defined as surgery that did not require an overnight hospital stay.

The intraoperative results analyzed were surgical time, intraoperative complications, and conversion to open surgery.

The postoperative results analyzed were complications such as hematoma, urinary retention, urinary infection, seroma, or surgical wound infection. The postoperative complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. The length of hospital stay was defined as the time elapsed from admission to discharge. We collected the postoperative pain 24 h after surgery measured from 0–10 cm according to a visual analog scale (VAS). We also collected the readmission to the hospital within 30 days post-surgery; chronic inguinal pain, defined as persistent inguinal pain three months after surgery, measured by a visual analog scale. The hernia recurrence was diagnosed by physical examination or ultrasound in the postoperative follow-up for one year.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. When analyzing the quantitative variables, we performed a normality test; if the sample was normal, the student's t-test was used, and for non-normal samples, we used the Mann–Whitney U test.

To compare the progression of the surgical times of both groups (TEP and TAPP), we performed a logistic regression analysis of the consecutive cases in the period evaluated.

We performed a multivariable analysis using logistic regression to determine the association of the choice of surgical technique (TEP vs. TAPP) with conversion to open surgery, the presence of any postoperative complication, chronic inguinal pain, and recurrent hernia, adjusted for the male sex, age ≥ 65 years, BMI ≥ 30, ASA III-IV, recurrent hernia repair, surgeon, and grade III hernia size (> 3cm) according to the European Hernia Society classification. For the analysis of quantitative dependent variables such as surgical time or hospital stay, we performed a multiple linear regression analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 software (IBM Corp. in Armonk, NY), and we established the statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Ethics

This retrospective database and study were approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital (HCB/2022/1015).

Results

Trends in the use of the laparoscopic approach

During the period studied, 255 patients underwent bilateral inguinal hernia repair. Surgeries were performed by open approach in 95 patients (37.9%) and by laparoscopic approach in 160 patients (62.7%). We observed an increase in the choice of the laparoscopic approach from 22% in 2016 to 94% in 2020 (p < 0.001).

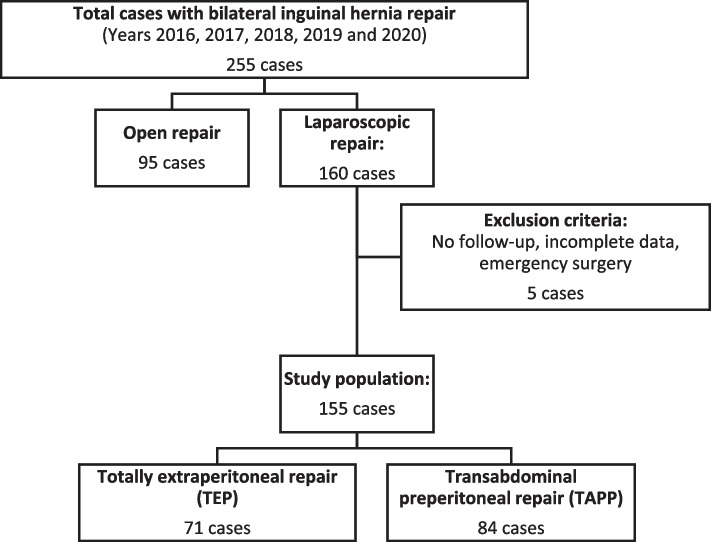

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 155 patients who underwent laparoscopic bilateral inguinal hernia repair were included. TEP was performed in 71 patients (46%) and TAPP in 84 patients (54%). The case selection flowchart is described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Case selection flow chart

Demographic, comorbidities, and hernia characteristics

When we analyzed our study population divided by the type of laparoscopic approach used (TEP or TAPP), we found no statistically significant differences in age, comorbidities, BMI, or ASA score (Table 1). The male sex ratio was higher in the TEP group than in the TAPP group (98.6% vs. 86.9%, p = 0.007). We found no significant differences in the proportion of recurrent hernias or the size of the hernia between both groups. The proportion of ambulatory surgery was higher in the TEP group than in the TAPP group (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with laparoscopic bilateral inguinal hernia repair (2016–2020)

| Total N = 155 |

TEP N = 71 (46%) |

TAPP N = 84 (54%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean ± SD | 63.40 ± 12.07 | 64.54 ± 12.33 | 62.44 ± 11.82 | 0.283 |

| Sex, N (%) | ||||

| Male | 143 (92.3) | 70 (98.6) | 73 (86.9) | 0.007 |

| Female | 12 (7.7) | 1 (1.4) | 11 (13.1) | 0.007 |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | ||||

| Arterial hypertension | 58 (37.4) | 27 (38) | 31 (36.9) | 0.885 |

| Heart disease | 15 (9.7) | 8 (11.3) | 7 (8.3) | 0.538 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 8 (5.2) | 5 (7) | 3 (3.6) | 0.471 |

| Renal disease | 8 (8.5) | 6 (8.5) | 2 (2.4) | 0.143 |

| Liver disease | 7 (4.5) | 3 (4.2) | 4 (4.8) | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (11) | 7 (9.9) | 10 (11.9) | 0.685 |

| Obesity | 18 (11.6) | 7 (9.9) | 11 (13.1) | 0.531 |

| Smoking history | 80 (51.6) | 39 (54.9) | 41 (48.8) | 0.447 |

| Abdominal lower surgery | 33 (21.3) | 14 (19.7) | 19 (22.6) | 0.66 |

| ASA, N (%) | 0.347 | |||

| ASA I | 41 (26.5) | 18 (25.4) | 23 (27.4) | 0.775 |

| ASA II | 100 (64.5) | 44 (62) | 56 (66.7) | 0.543 |

| ASA III | 14 (9) | 9 (12.7) | 5 (6) | 0.146 |

| BMI, Mean ± SD | 25.63 ± 3.58 | 25.19 ± 3.27 | 25.99 ± 3.8 | 0.189 |

| Recurrent Repair, N (%) | 14 (9) | 5 (7) | 9 (10.7) | 0.427 |

| Hernia size (EHS), n (%) | 0.628 | |||

| Grade I (< 1.5 cm) | 15 (9.7) | 8 (11.3) | 7 (8.3) | |

| Grade II (1.5–3 cm) | 86 (55.5) | 39 (54.9) | 47 (56) | |

| Grade III (> 3 cm) | 54 (34.8) | 24 (33.8) | 30 (35.7) | |

| Outpatient surgery, N (%) | 32 (20.6) | 29 (40.8) | 3 (3.6) | < 0.001 |

SD Standard deviation, BMI Body mass index, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, EHS European Hernia Society

Intraoperative and postoperative outcomes

The mean operative time was longer in the TAPP group than in the TEP group (107 min vs. 82 min, p < 0.001). The conversion rate to open surgery was higher in the TEP group than in the TAPP group (8.5% vs. 0%, p = 0.008). The conversion of the six patients in the TEP group to open surgery was due to technical difficulty in the dissection of the preperitoneal space. Five patients underwent conversion to a Lichtenstein repair, and one patient to a Nyhus repair. Also, one patient converted from TEP to TAPP due to technical difficulty caused by peritoneal rupture. The mean hospital stay was longer in the TAPP group than in the TEP group (p < 0.001). We did not observe significant differences in the proportion of specific postoperative complications, complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, postoperative pain at 24 h, chronic inguinal pain, or proportion of hernia recurrence (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes of patients with laparoscopic bilateral inguinal hernia repair (2016–2020)

| Total N = 155 |

TEP N = 71 (46%) |

TAPP N = 84 (54%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (min), Mean ± SD | 96.11 ± 33.27 | 82.99 ± 30.84 | 107.2 ± 31.29 | < 0.001 |

| TEP to TAPP conversion, N (%) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Open conversion, N (%) | 6 (3.9) | 6 (8.5) | 0 | 0.008 |

| Intraoperative complication, N (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Postoperative complications, N (%) | ||||

| Hematoma | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 0.458 |

| Urinary retention or infection | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.2) | 1 |

| Seroma | 24 (15.5) | 9 (12.7) | 15 (17.9) | 0.374 |

| Wound infection | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 0.458 |

| Any complications | 27 (17.4) | 11 (15.5) | 16 (19) | 0.672 |

| Clavien Dindo, N (%) | 0.143 | |||

| I | 25 (16.1) | 10 (14.1) | 15 (17.9) | 0.525 |

| II | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.2) | 1 |

| Length of stay (days), Mean ± SD | 1.05 ± 0.44 | 0.65 ± 0.61 | 1.05 ± 0.44 | < 0.001 |

| VAS pain 24 h, mean ± SD | 2.18 ± 1.6 | 2.18 ± 0.85 | 2.17 ± 1.77 | 0.851 |

| Readmission 30 days, N (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chronic Inguinal Pain (≥ 3m), N (%) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0.593 |

| Hernia recurrence, N (%) | 8 (5.2) | 5 (7) | 3 (3.6) | 0.471 |

SD Standard deviation, VAS Visual Analogue Scale

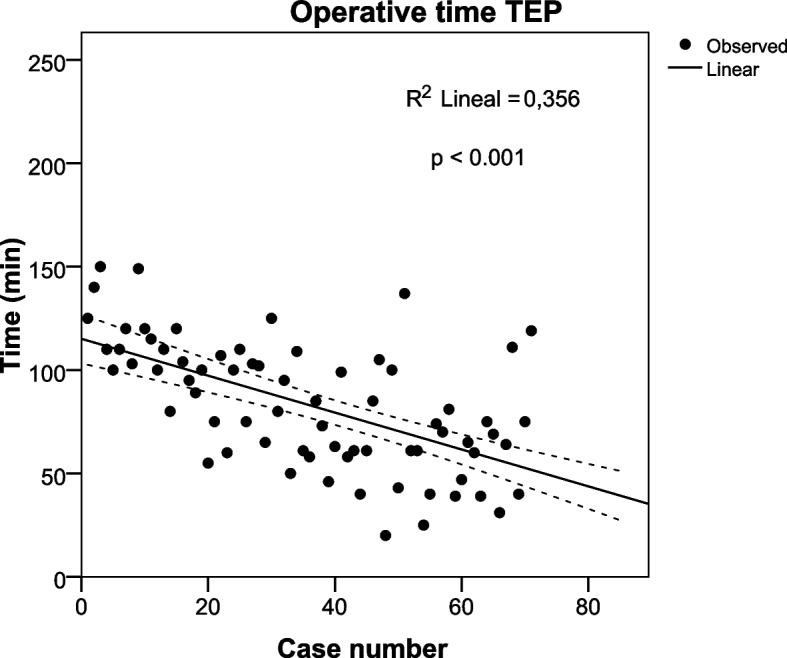

Evolution of operative time

When analyzing the progression of operative time (Figs. 2 and 3) in the study period, through a linear regression analysis, we observed that the decrease in operative time was greater in the TEP group (R2 = 0.356, p < 0.001) than in the TAPP group (R2 = 0.066 p = 0.018).

Fig. 2.

Operative time in consecutive cases of Totally extraperitoneal repair (TEP). Linear regression analysis (R2 = 0.356, p < 0.001)

Fig. 3.

Operative time in consecutive cases of Transabdominal preperitoneal repair (TAPP). Linear regression analysis (R2 = 0.066 p = 0.018)

Multivariable analysis of surgical outcomes

When performing a multivariable analysis by logistic regression adjusted for the male sex, age ≥ 65 years, BMI ≥ 30, ASA II-IV, recurrent hernia repair, and hernia size > 3cm, we did not observe an association between the choice of surgical technique (TEP vs. TAPP) with postoperative complications, chronic inguinal pain, or hernia recurrence (Table 3). The differences between both techniques in conversion rate (p = 0.999), surgical time (p = 0.942), and hospital stay (p = 0.381) were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Associations between operative method (TEP versus TAPP) and postoperative outcomes of bilateral inguinal hernia repair

| TEP versus TAPP | Adjusted Oddsa | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Any postoperative complication | 0.26 (0.33–2.04) | 0.2 |

| Chronic Inguinal Pain | 4.42 (0.04–49.93) | 0.529 |

| Hernia recurrence | 0.89 (0.09–8.3) | 0.709 |

aLogistic regression model adjusted for the male sex, age ≥ 65 years, BMI ≥ 30, ASA III-IV, recurrent repair, surgeon, and EHS hernia size III (> 3 cm)

Discussion

This study did not observe significant differences between TEP and TAPP in conversion rate, operative time, hospital stay, the proportion of postoperative complications, acute postoperative pain, chronic inguinal pain, and hernia recurrence.

The laparoscopic approach in inguinal hernia repair is a valid alternative to traditional open repair [15, 25]. However, despite the recommendations of international guidelines, the utilization rates are variable: 38% in the USA [26], 23% in England [27] and 5.7% in Spain [28]. The use rate of laparoscopy for bilateral inguinal hernia repair in Spain in 2019 was 23% [29].In our study, we observed a significant increase in the use of laparoscopic access for bilateral hernia repair, reaching 94% in 2020.

TEP and TAPP are the two most used laparoscopic procedures for inguinal hernia repair. Most previous studies have not identified advantages between the two laparoscopic techniques [25, 30]. The main difference between TEP and TAPP is the access route to the preperitoneal space. For many groups, TEP is more attractive as it reproduces the access route of the open preperitoneal repair without accessing the abdominal cavity and avoids the risk of intra-abdominal organ injury [3]. In contrast, other groups prefer TAPP as it has an access route more similar to conventional laparoscopy for other pathologies and the advantage of exploring both inguinal regions [31].

Visceral and vascular injuries are the most important intraoperative complications of inguinal hernia repair. It has been described that visceral injuries are more frequent in TAPP than in TEP, reporting an incidence of 0.21% [5, 13]. Vascular lesions, especially inferior epigastric artery lesions, are more common in TEP [32, 33], and 0–3% incidence has been reported [22, 34]. Our study reported no intraoperative complications in bilateral inguinal hernia repairs by TEP and TAPP.

Accidental tears of the peritoneum, bleeding, and adhesions have been reported as the main causes of conversion from laparoscopic repair to open surgery [35, 36]. Previous studies describe a higher incidence of conversion to open surgery in TEP [22, 37]. For anatomical orientation and identification of structures, it is necessary to create an adequate preperitoneal space that allows correct mesh placement and control of complications such as injury to the inferior epigastric artery [37]. The higher conversion rate in TEP could be explained by the greater difficulty in creating and maintaining a wide preperitoneal space, which is worsened by adhesions from previous preperitoneal surgery and tears of the peritoneum [35, 36]. We found six cases of conversion to open surgery in TEP and no conversion in TAPP; however, when performing the multivariable analysis, the technique performed was not associated with the conversion. Conversion to open surgery in the TEP group occurred in cases 1, 10, 15, 25, 31, and 35. These cases were operated on in the first half of the study, possibly related to learning the technique. Previous studies have shown that conversion is greater in the learning phase and that between 30–75 surgeries are required to complete the learning curve [38, 39]. The surgeons who performed TEP and TAPP in our study began and completed their learning curve during the time analyzed; however, this learning was not carried out only in bilateral inguinal hernias. In this same period, the transition to laparoscopic surgery to repair unilateral inguinal hernias also began.

The operative time reported in some studies was longer in TEP [20, 24], while other authors report that the operative time is longer in TAPP [20, 40]. These differences can be explained because the operative time depends on the type of hernia, the patient's condition, and the surgeon's experience [23, 41]. We must remember that these studies were conducted in unilateral hernias; a recent randomized trial in bilateral hernias reported that operative time was longer in TEP [22]. Our study found that the operative time was longer in TAPP; however, these differences were not statistically significant when performing the multivariable analysis. Self-adhering mesh and a balloon dissector to create the preperitoneal space in TEP could decrease operating time. In TAPP, using conventional mesh fixed with glue and subsequent suturing of the bilateral peritoneum increased operating time. In addition, we observed a significant decrease in operative time in both surgical techniques in the study period, which was greater in TEP. At the beginning of the study, the surgical teams had no previous experience in laparoscopic hernia repair; however, the team that performed TEP was made up of two surgeons, and the team that performed TAPP was made up of three surgeons, which could explain the differences.

Differences between TEP and TAPP in common postoperative complications such as hematoma, seroma, wound infection, and urinary retention analyzed in two systematic reviews and meta-analyses were not statistically significant [23, 42]. In a recent meta-analysis, TEP was associated with a lower risk of genital edema, and TAPP repair with a lower risk of seroma formation [43]. A likely explanation could be that TAPP has more surgical space, which facilitates inversion of the transversalis fascia and fixation, associated with a lower incidence of seroma [44]. In our study, the differences in postoperative complications were not significant. When performing multivariable analysis, we observed that the type of technique used was not associated with the presence of complications.

The reported results of the differences in hospital stay between the two techniques are very diverse, probably because it depends on various factors such as age, complication rate, postoperative pain, social factors, educational factors, and trust in the surgeon [45, 46]. A randomized trial found no significant difference in hospital stay between TAPP and TEP in bilateral inguinal hernia repair [22]. In our study, the length of hospital stay was shorter in TEP; however, these differences were not statistically significant when performing the multivariable analysis. The shorter operative time reported in the TEP group could be a favorable factor for the greater use of outpatient surgery in these patients and reduce their hospital stay. The current recommendation is to use outpatient surgery for inguinal hernia repair, regardless of the technique [15]. In recent years, there has been an increase in the percentage of inguinal hernia repairs performed as outpatient surgery [47]. The use of outpatient surgery in inguinal hernia repair is variable in each country, being reported in more than 70% of cases in countries such as Denmark, France, and Sweden [48, 49]. However, it is less than 40% for bilateral inguinal hernias in Spain [29]. The decision of the surgical teams can explain these differences. In our study, the surgeons who performed TAPP used outpatient surgery at the end of the study period. The use of laparoscopy in repairing a bilateral inguinal hernia would increase the use of outpatient surgery by reducing pain and complications compared to open surgery.

Some studies report less early postoperative pain in TEP [21, 24, 50]. However, a recent systematic review found no difference in postoperative pain between TEP and TAPP [51]. Using tacks to fix the mesh and close the peritoneum increases postoperative pain, so glue or self-fixing mesh is recommended [14, 52]. Some authors suggest that postoperative pain is greater in TAPP than in TEP, mainly due to the use of tacks [25, 53]. In our study, self-fixing meshes were used in TEP and glue to fix the mesh in TAPP, and we found no differences in postoperative pain between the two techniques.

Previous studies have found no differences between TEP and TAPP in chronic pain and hernia recurrence [23, 24, 51, 52, 54]. The reported incidence of recurrence of laparoscopic repair is similar to that of open repair [55, 56]. The main causes of recurrence after laparoscopic repair are incomplete dissection, mesh size that is too small, and improper mesh position or migration [57]. Using a mesh of at least 10 × 15 cm, proper surgical technique, and training can significantly reduce the recurrence rate [14, 15]. When we performed a multivariable analysis, we found no association between the type of laparoscopic technique chosen and chronic pain or hernia recurrence.

Previous studies in unilateral and bilateral inguinal hernias have not observed significant differences in the results of TEP and TAPP [22, 23]. However, some studies recommend the TAPP for scrotal hernias and incarcerated hernias [58, 59]. In patients with previous abdominal surgeries, TEP has the advantage of being a procedure completely performed in the preperitoneal space [60]. In our opinion, surgeons can use any of these techniques; however, surgeons from specialized abdominal wall units must know how to perform both techniques.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective design, the small number of cases because we only included bilateral hernias, the performance of laparoscopic techniques (TEP and TAPP) by two different teams of surgeons, the non-assessment of costs and the postoperative follow-up period that was not more than one year. The two groups of surgeons used different synthetic meshes. The choice of mesh depended on the preference of each group of surgeons. Surgeons in the TEP group prioritized reducing surgical time using self-adhesive mesh, while surgeons in the TAPP group used simple polypropylene mesh because of its lower cost. However, its strengths are being one of the few studies that specifically analyzes the results of TEP and TAPP in bilateral inguinal hernia repair, the similarity of the groups analyzed, and the similar experience of surgical teams in inguinal hernia repair by laparoscopy.

Conclusions

In this study, bilateral inguinal hernia repair by TEP and TAP presented similar conversion rates, operative time, hospital stay, the proportion of postoperative complications, acute postoperative pain, chronic inguinal pain, and hernia recurrence. However, randomized trials are needed to compare the results of both techniques, specifically in bilateral inguinal hernia repair.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ASA

American Society of Anaesthesiologists

- BMI

Body mass index

- TEP

Totally extraperitoneal

- TAPP

Transabdominal preperitoneal

Authors’ contributions

NJH: project development, data collection and analysis, manuscript writing and editing. SG: project development, data analysis, manuscript writing and editing. IB: data collection, manuscript editing. EB: data collection, manuscript editing. JJE: manuscript editing. CG: manuscript editing. OV: manuscript editing. DM: manuscript editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective database and study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic Barcelona (Reg. HCB/2022/1015). The need for written informed consent was waived by the Research Ethics Committee with medicines of Hospital Clínic Barcelona (Comité de Ética de la Investigación con medicamentos – CEIm) due to retrospective nature of the study. This study follows the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for research on human beings.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kingsnorth A, LeBlanc K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet. 2003;362:1561–1571. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurzer M, Kark A, Hussain T. Inguinal hernia repair. J Perioper Pract. 2007;17:318–21. doi: 10.1177/175045890701700704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gould J. Laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1073–81. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claus CMP, Rocha GM, Campos ACL, Bonin EA, Dimbarre D, Loureiro MP, et al. Prospective, randomized and controlled study of mesh displacement after laparoscopic inguinal repair: fixation versus no fixation of mesh. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1134–1140. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4314-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmedt CG, Sauerland S, Bittner R. Comparison of endoscopic procedures vs Lichtenstein and other open mesh techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:188–199. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-9126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheuermann U, Niebisch S, Lyros O, Jansen-Winkeln B, Gockel I. Transabdominal Preperitoneal (TAPP) versus Lichtenstein operation for primary inguinal hernia repair - A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Surg. 2017;17:55. doi: 10.1186/s12893-017-0253-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wennergren JE, Plymale M, Davenport D, Levy S, Hazey J, Perry KA, et al. Quality-of-life scores in laparoscopic preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3467–3473. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bignell M, Partridge G, Mahon D, Rhodes M. Prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic (transabdominal preperitoneal-TAPP) versus open (mesh) repair for bilateral and recurrent inguinal hernia: incidence of chronic groin pain and impact on quality of life: results of 10 year follow-up. Hernia. 2012;16:635–640. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0940-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarli L, Iusco DR, Sansebastiano G, Costi R. Simultaneous repair of bilateral inguinal hernias: a prospective, randomized study of open, tension-free versus laparoscopic approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2001;11:262–267. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hynes DM, Stroupe KT, Luo P, Giobbie-Hurder A, Reda D, Kraft M, et al. Cost effectiveness of laparoscopic versus open mesh hernia operation: results of a Department of Veterans Affairs randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer Netto F, Quereshy F, Camilotti BG, Pitzul K, Kwong J, Jackson T, et al. Hospital costs associated with laparoscopic and open inguinal herniorrhaphy. JSLS. 2014;18(4):217. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ielpo B, Duran H, Diaz E, Fabra I, Caruso R, Malavé L, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) versus Lichtenstein repair for bilateral inguinal hernias. Am J Surg. 2018;216:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bittner R, Arregui ME, Bisgaard T, Dudai M, Ferzli GS, Fitzgibbons RJ, et al. Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia [International Endohernia Society (IEHS)] Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2773–2843. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1799-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poelman MM, Vandenheuvel B, Deelder JD, Abis GSA, Beudeker N, Bittner RR, et al. EAES Consensus Development Conference on endoscopic repair of groin hernias. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3505–19. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2009;13:343–403. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HerniaSurge Group International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018;22:1–165. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ielpo B, Nuñez-Alfonsel J, Duran H, Diaz E, Fabra I, Caruso R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of randomized study of laparoscopic versus open bilateral inguinal hernia repair. Ann Surg. 2018;268:725–730. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKernan JB, Laws HL. Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias using a totally extraperitoneal prosthetic approach. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:26–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00591232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arregui ME, Davis CJ, Yucel O, Nagan RF. Laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia using a preperitoneal approach: a preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992;2:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bracale U, Melillo P, Pignata G, di Salvo E, Rovani M, Merola G, et al. Which is the best laparoscopic approach for inguinal hernia repair: TEP or TAPP? A systematic review of the literature with a network meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3355–3366. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishna A, Misra MC, Bansal VK, Kumar S, Rajeshwari S, Chabra A. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) versus totally extraperitoneal (TEP) approach: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:639–649. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1931-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma D, Yadav K, Hazrah P, Borgharia S, Lal R, Thomas S. Prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and laparoscopic totally extra peritoneal (TEP) approach for bilateral inguinal hernias. Int J Surg. 2015;22:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei FX, Zhang YC, Han W, Zhang YL, Shao Y, Ni R. Transabdominal Preperitoneal (TAPP) Versus Totally Extraperitoneal (TEP) for Laparoscopic Hernia Repair: a meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:375–383. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L-S, Chen W-C, Kang Y-N, Wu C-C, Tsai L-W, Liu M-Z. Effects of transabdominal preperitoneal and totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: an update systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:418–428. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bittner R, Montgomery MA, Arregui E, Bansal V, Bingener J, Bisgaard T, et al. Update of guidelines on laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia (International Endohernia Society) Surg Endosc. 2015;29:289–321. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3917-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madion M, Goldblatt MI, Gould JC, Higgins RM. Ten-year trends in minimally invasive hernia repair: a NSQIP database review. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:7200–7208. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-08217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palser TR, Swift S, Williams RN, Bowrey DJ, Beckingham IJ. Variation in outcomes and use of laparoscopy in elective inguinal hernia repair. BJS Open. 2019;3:466–475. doi: 10.1002/bjs5.50158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guillaumes S, Hoyuela C, Hidalgo NJ, Juvany M, Bachero I, Ardid J, et al. Inguinal hernia repair in Spain. A population-based study of 263,283 patients: factors associated with the choice of laparoscopic approach. Hernia. 2021;25:1345–54. doi: 10.1007/s10029-021-02402-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hidalgo NJ, Guillaumes S, Bachero I, Holguín V, Momblán D. Trends and predictors of laparoscopic bilateral inguinal hernia repair in Spain: a population-based study. Surg Endosc. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00464-023-09967-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Köckerling F, Bittner R, Jacob DA, Seidelmann L, Keller T, Adolf D, et al. TEP versus TAPP: comparison of the perioperative outcome in 17,587 patients with a primary unilateral inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3750–3760. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4150-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wauschkuhn CA, Schwarz J, Boekeler U, Bittner R. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: gold standard in bilateral hernia repair? Results of more than 2800 patients in comparison to literature. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:3026–3030. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dulucq J-L, Wintringer P, Mahajna A. Laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: lessons learned from 3,100 hernia repairs over 15 years. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:482–486. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feliu X, Clavería R, Besora P, Camps J, Fernández-Sallent E, Viñas X, et al. Bilateral inguinal hernia repair: laparoscopic or open approach? Hernia. 2011;15:15–18. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0736-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg P, Rajagopal M, Varghese V, Ismail M. Laparoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair with nonfixation of the mesh for 1,692 hernias. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1241–1245. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferzli GS, Khoury GE. Treating recurrence after a totally extraperitoneal approach. Hernia. 2006;10:341–346. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muzio G, Bernard K, Polliand C, Rizk N, Champault G. Impact of peritoneal tears on the outcome and late results (4 years) of endoscopic totally extra-peritoneal inguinal hernioplasty. Hernia. 2006;10:426–429. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen R v, Alvarez G, Roll S, Garcia ME, Kawahara N, Schiavon CA, et al. Transabdominal or totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repair? Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:264–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuge H, Yokoo T, Uchida H, Yamaoka K, Yoshikawa S. Learning curve for laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal repair: A single-surgeon experience of consecutive 105 procedures. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2020;13:205–210. doi: 10.1111/ases.12724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sivakumar J, Chen Q, Hii MW, Cullinan M, Choi J, Steven M, et al. Learning curve of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:2453–2475. doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09760-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Günal O, Ozer S, Gürleyik E, Bahçebaşi T. Does the approach to the groin make a difference in hernia repair? Hernia. 2007;11:429–434. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kukleta JF. Causes of recurrence in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. J Minim Access Surg. 2006;2:187–191. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.27736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aiolfi A, Cavalli M, Micheletto G, Lombardo F, Bonitta G, Morlacchi A, et al. Primary inguinal hernia: systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis comparing open, laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal, totally extraperitoneal, and robotic preperitoneal repair. Hernia. 2019;23:473–484. doi: 10.1007/s10029-019-01964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hung T-Y, Wu C-C, Chen L-S, Kang Y-N. Safety of two common laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy approaches: an updated systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9:2007–2021. doi: 10.21037/tau-20-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reddy VM, Sutton CD, Bloxham L, Garcea G, Ubhi SS, Robertson GS. Laparoscopic repair of direct inguinal hernia: a new technique that reduces the development of postoperative seroma. Hernia. 2007;11:393–396. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timişescu L, Turcu F, Munteanu R, Gîdea C, Drăghici L, Ginghină O, et al. Treatment of bilateral inguinal hernia – minimally invasive versus open surgery procedure. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2013;108:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mouton WG, Bessell JR, Otten KT, Maddern GJ. Pain after laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:445–448. doi: 10.1007/s004649901011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guillaumes S, Hidalgo NJ, Bachero I, Juvany M. Outpatient inguinal hernia repair in Spain: a population-based study of 1,163,039 patients-clinical and socioeconomic factors associated with the choice of day surgery. Updates Surg. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13304-022-01407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kehlet H, Bay-Nielsen M, Danish Hernia Database Collaboration Nationwide quality improvement of groin hernia repair from the Danish Hernia Database of 87,840 patients from 1998 to 2005. Hernia. 2008;12:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saia M, Mantoan D, Buja A, Bertoncello C, Baldovin T, Zanardo C, et al. Increased rate of day surgery use for inguinal and femoral hernia repair in a decade of hospital admissions in the Veneto Region (north-east Italy): a record linkage study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:349. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bansal VK, Misra MC, Babu D, Victor J, Kumar S, Sagar R, et al. A prospective, randomized comparison of long-term outcomes: chronic groin pain and quality of life following totally extraperitoneal (TEP) and transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2373–2382. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aiolfi A, Cavalli M, del Ferraro S, Manfredini L, Lombardo F, Bonitta G, et al. Total extraperitoneal (TEP) versus laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) hernioplasty: systematic review and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hernia. 2021;25:1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s10029-021-02407-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antoniou SA, Köhler G, Antoniou GA, Muysoms FE, Pointner R, Granderath F-A. Meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing nonpenetrating vs mechanical mesh fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2016;211:239–249.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lal P, Philips P, Saxena KN, Kajla RK, Chander J, Ramteke VK. Laparoscopic total extraperitoneal (TEP) inguinal hernia repair under epidural anesthesia: a detailed evaluation. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:595–601. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niebuhr H, Köckerling F. Surgical risk factors for recurrence in inguinal hernia repair - a review of the literature. Innov Surg Sci. 2017;2:53–59. doi: 10.1515/iss-2017-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bittner R, Sauerland S, Schmedt C-G. Comparison of endoscopic techniques vs Shouldice and other open nonmesh techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:605–615. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-9049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Butters M, Redecke J, Köninger J. Long-term results of a randomized clinical trial of Shouldice, Lichtenstein and transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repairs. Br J Surg. 2007;94:562–565. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feliu X, Jaurrieta E, Viñas X, Macarulla E, Abad JM, Fernández-Sallent E. Recurrent inguinal hernia: a ten-year review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14:362–367. doi: 10.1089/lap.2004.14.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rebuffat C, Galli A, Scalambra MS, Balsamo F. Laparoscopic repair of strangulated hernias. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:131–134. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tran HM, MacQueen I, Chen D, Simons M. Systematic Review and Guidelines for Management of Scrotal Inguinal Hernias. J Abdominal Wall Surg. 2023;2:11195. doi: 10.3389/jaws.2023.11195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Köckerling F. TEP for elective primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair in men: what do we know? Hernia. 2019;23:439–459. doi: 10.1007/s10029-019-01936-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.