Abstract

The largest subunit of RNA polymerase (Pol) II harbors an evolutionarily conserved C‐terminal domain (CTD), composed of heptapeptide repeats, central to the transcriptional process. Here, we analyze the transcriptional phenotypes of a CTD‐Δ5 mutant that carries a large CTD truncation in human cells. Our data show that this mutant can transcribe genes in living cells but displays a pervasive phenotype with impaired termination, similar to but more severe than previously characterized mutations of CTD tyrosine residues. The CTD‐Δ5 mutant does not interact with the Mediator and Integrator complexes involved in the activation of transcription and processing of RNAs. Examination of long‐distance interactions and CTCF‐binding patterns in CTD‐Δ5 mutant cells reveals no changes in TAD domains or borders. Our data demonstrate that the CTD is largely dispensable for the act of transcription in living cells. We propose a model in which CTD‐depleted Pol II has a lower entry rate onto DNA but becomes pervasive once engaged in transcription, resulting in a defect in termination.

Keywords: carboxy‐terminal domain (CTD), mammalian transcription, Pol II interactome, RNA polymerase II (Pol II), termination

Subject Categories: Chromatin, Transcription & Genomics

RNA polymerase II is essential for gene expression. This study shows that its Carboxy‐Terminal Domain plays a previously unappreciated role in the control of transcription termination and is dispensable for transcription in human cells.

Introduction

Three RNA polymerases are ubiquitously expressed in all eukaryotes (Pol I, II, and III), sharing homology and transcribing specific, nonoverlapping categories of genes (Cramer et al, 2008). RNA polymerase (Pol) II is responsible for the transcription of the broadest and most diverse group of genes and is further distinguished from the other polymerases by the presence of a C‐terminal domain (CTD) located on its largest subunit, RPB1. The CTD is a Low Complexity Domain (LCD) that consists of a heptapeptide repeat with the consensus sequence Y1‐S2‐P3‐T4‐S5‐P6‐S7 (Eick & Geyer, 2013). The CTD residues can be targeted by various dynamic post‐translational modifications (Zaborowska et al, 2016) that are not necessarily homogeneously distributed along the heptads (Schüller et al, 2016). The number of repeats of the CTD varies with species, for example from 26 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to 52 in mammals (Eick & Geyer, 2013). The CTD also carries noncanonical repeats that are found in the distal part of the mammalian structure.

The CTD has been extensively studied and dissected by us and others. It serves as a platform for the recruitment of a plethora of factors involved in transcription‐related events. It is believed that specific residues (or their modifications) and heptads within the CTD play distinct roles during individual steps of the transcription cycle (Zaborowska et al, 2016). For example, it is broadly documented that phosphorylation of Ser5 and Ser2 residues are essential for transcription initiation and elongation, respectively (Buratowski, 2009), while Ser7 phosphorylation is required for the termination/maturation of small nuclear RNA (snRNA; Egloff et al, 2007), indicating a relative gene‐specificity of action for some heptad residues. Although most residues of the consensus heptad harbor relatively well‐conserved functions, Tyr1 seems to have evolved from yeast to metazoans (Mayer et al, 2012; Descostes et al, 2014; Hsin et al, 2014). In S. cerevisiae, genome‐wide ChIP profiling revealed that Tyr1 phosphorylation (Tyr1P) accumulates along the gene bodies and is depleted from their TSS and 3′ ends, indicating a possible role in the hindrance of termination factor recruitment (Mayer et al, 2012). Our own work in human cells showed a rather opposite profile at most gene locations, with enrichment at promoters, enhancers, and post 3′ end (Descostes et al, 2014). More recently, we demonstrated the importance of the tyrosine (Tyr) residues in the termination process at both 3′ and 5′ ends of genes by analyzing a CTD mutant (YFFF) in which ¾ of the Tyr were mutated (Shah et al, 2018).

The catalytic activity of Pol II is carried by the conserved core of the enzyme, composed of RPB1 and RPB2 subunits, and does not involve the CTD (Bernecky et al, 2016). In agreement with this finding, a CTD‐less Pol II can perform transcription of a DNA template in vitro, in nonspecific or specific transcription assays (Laybourn & Dahmus, 1989; Buratowski & Sharp, 1990; Nair et al, 2005). However, in specific assays depending on the general transcription factors (GTFs), its transcriptional activity is reduced and the requirement for the TFIIH GTF seems to be the limiting factor. A human CTD‐depleted Pol II containing only five repeats (CTD‐Δ5) can also bind promoters and transcribe reporter genes of transfected plasmids, possibly in the context of low chromatinization of the template in living cells (Gerber et al, 1995; Lux et al, 2005). However, studies investigating the expression of a few target genes in total RNA or run‐on experiments could not detect genomic transcripts when CTD‐Δ5 Pol II was expressed alone in the cells (Gerber et al, 1995; Meininghaus & Eick, 1999; Meininghaus et al, 2000). Thus, open questions remain regarding the requirement of the CTD in living cells, both in the transcription cycle and in related functions such as 3′ end termination and processing. To address these questions, we investigated the transcriptome and interactome of the CTD‐Δ5. Our data reveal a strong termination phenotype and a loss of interaction with both the Mediator (Med) and Integrator (Int) complexes, similar to our previously characterized YFFF mutant (Shah et al, 2018). However, the CTD‐Δ5 showed a more pronounced pervasive nascent transcriptome phenotype, with less marked effects on the mature transcriptome as measured by polyA RNA‐seq. Furthermore, our investigation of the 3D structure of the chromatin using HiC did not reveal major changes in spatial organization due to the massive read‐through of Pol II, including at locations where Pol II crosses Topologically Associating Domain (TAD) borders. Overall, we propose a model in which CTD‐depleted Pol II has a lower rate of entry onto DNA but becomes extremely pervasive once engaged in transcription, resulting in a global loss of termination.

Results

CTD‐Δ5 truncation severely impairs the nascent transcriptome

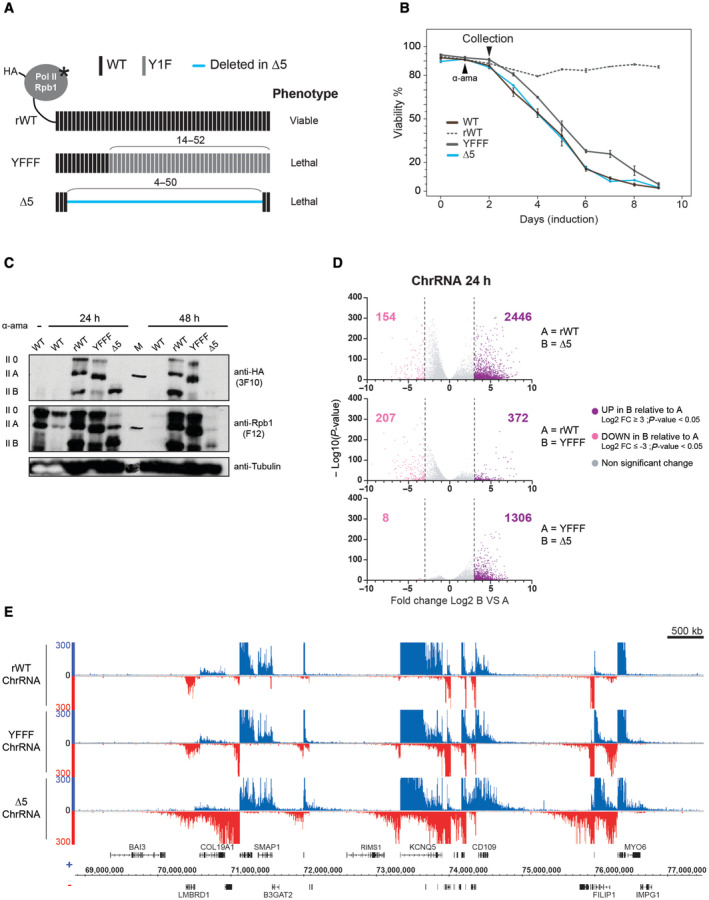

To investigate the role of the CTD in transcription in a cellular context, we undertook the analysis of the CTD‐Δ5 mutant transcriptome in RNA‐seq experiments. To avoid a Pol II stability bias, all repeats were deleted except for the essential repeats 1–3 & 51–52 (Chapman et al, 2004, 2005). As controls and for comparison, we used the recombinant wild‐type (rWT) containing the WT CTD sequence including the noncanonical repeats, and mutant YFFF, where Tyr residues in the last three‐quarters of the WT CTD are mutated to Phe (Shah et al, 2018; Fig 1A). All mutant CTD sequences as well as the control rWT were cloned in an HA‐tagged α‐amanitin resistant RPB1 expression vector under the control of a Tet‐off system. The plasmid harbors a neomycin resistance cassette to allow the selection of the transfected cells as described previously (Meininghaus et al, 2000). After 24 h induction of rWT and mutant cells, α‐amanitin was added to the medium to shut down endogenous Pol II and cell viability was monitored for 8 days. As previously reported, the viability of untransfected WT Raji cells, as well as mutant‐expressing cells, was found to steadily decrease in the presence of α‐amanitin (Meininghaus et al, 2000; Shah et al, 2018). Interestingly, the CTD‐Δ5 mutant behaves similarly to WT cells, suggesting that the truncation does not rescue the endogenous Pol II shut down (Fig 1B). As previously described, rWT and YFFF mutants are stable at the protein level, showing both the IIO and IIA forms in western blots, while the CTD‐Δ5 mutant runs as a unique and faster migrating band due to depletion of the CTD. Since CTD‐Δ5 expression is no longer detectable at 48 h, we collected the cells at 24 h after α‐amanitin treatment (Fig 1C). At this point, living cells represent at least 85% of the total population, all the recombinant polymerases are well expressed, endogenous Pol II is blocked by α‐amanitin and has essentially disappeared from all genomic locations (Fenouil et al, 2012; Fig 1B and C).

Figure 1. CTD mutations lead to a major transcriptional deregulation.

- Schematic representation of the recombinant RPB1 harboring an N‐terminal HA‐tag and a point mutation conferring α‐amanitin resistance (asterisk). Unmanipulated heptads in the CTD are depicted in black (WT), heptads where Tyrosine‐1 is mutated to phenylalanine are depicted in light gray (Y1F) and deleted heptads in the CTD‐∆5 are indicated by a blue line. Positions of the manipulated heptads in the CTD are indicated.

- Viability curve of cells following 24 h of recombinant Pol II expression induction by removal of tetracycline (Tet‐Off system) and treatment with α‐amanitin (black arrow‐head). Untransfected Raji (WT: black) is shown for reference. For all experiments presented in this article, cells are collected after 24 h of α‐amanitin treatment for CTD‐∆5 and YFFF mutants expressing cells since CTD‐∆5 is unstable after 48 h (see panel C). Error bars representing top and bottom values are based on the average of three independent experiments.

- Western blot analysis of the recombinant RPB1 expression (rWT, YFFF, and ∆5) assessed by HA‐tag expression after 24 or 48 h of α‐amanitin treatment following 24 h of induction. Untransfected Raji extracts are shown for comparison (WT). Total RPB1 levels are represented by the F12 western blot. Tubulin was used as a loading control.

- Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in chromatin‐associated RNA‐seq (ChrRNA) datasets: protein‐coding genes UP (purple) and DOWN (pink) regulated in B relative to A after 24 h α‐amanitin treatment (n = 22,810). Experiments were done in biological duplicates. Threshold: log2 fold change ≥ 3, P‐value < 0.05. See Fig EV1B for threshold at log2 fold change ≥ 1.5.

- Example of ChrRNA‐seq datasets showing pervasive transcription phenotypes in YFFF and CTD‐∆5 mutants compared with rWT.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We then assessed the mutants' nascent transcriptomes by performing chromatin‐associated RNA sequencing (ChrRNA‐seq) experiments. Global differential expression (DESeq) analysis reveals that a large number of genes are affected. Interestingly, a larger fraction of genes tends to be upregulated in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant in ChRNA‐seq as compared to YFFF (Figs 1D and EV1). Similar trends are observed when less stringent fold change cut‐offs are applied for the DESeq analysis (Fig EV1B). Further analysis revealed that most of the genes affected in the YFFF mutant context are similarly affected in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant (Fig EV1A–C), suggesting that the CTD‐Δ5 mutant defect is an even more extreme variant of the YFFF mutant termination and read‐through (RT) phenotype. An example of the transcriptional phenotype of both YFFF and CTD‐Δ5 mutants in human Raji B cells over a large genomic area is shown in Fig 1E. Overall, these analyses indicate a strong impairment of the nascent transcriptome in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant, with an apparent wide upregulation of gene transcription. However, we note that this conclusion should be moderated given that these data are not spike‐in normalized and that previous work has shown that the CTD‐Δ5 shows overall less transcription activity.

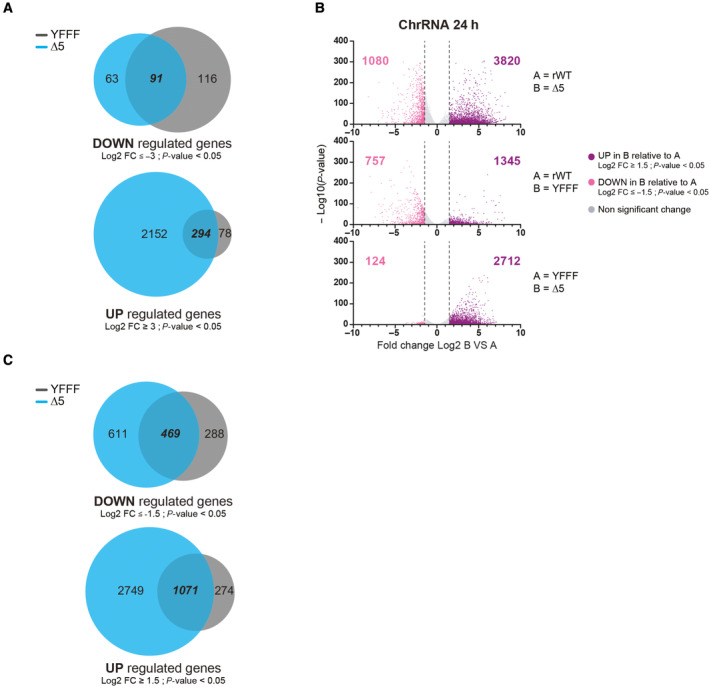

Figure EV1. CTD‐∆5 mutation impacts transcription to a higher extent than YFFF mutation.

- Venn diagram showing common genes UP and DOWN regulated between YFFF and CTD‐∆5 mutants compared with rWT at a threshold of log2 fold change ≥ 3 and P‐value < 0.05. Experiments were done in biological duplicates.

- Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in chromatin‐associated (ChrRNA) RNA‐seq datasets: protein‐coding genes UP (purple) and DOWN (pink) regulated in B relative to A after 24‐h α‐amanitin treatment. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. (Threshold: log2 fold change ≥ 1.5, P‐value < 0.05).

- Venn diagram showing common genes UP and DOWN regulated between YFFF and CTD‐∆5 mutants compared with rWT at a threshold of log2 fold change ≥ 1.5 and P‐value < 0.05. Experiments were done in biological duplicates.

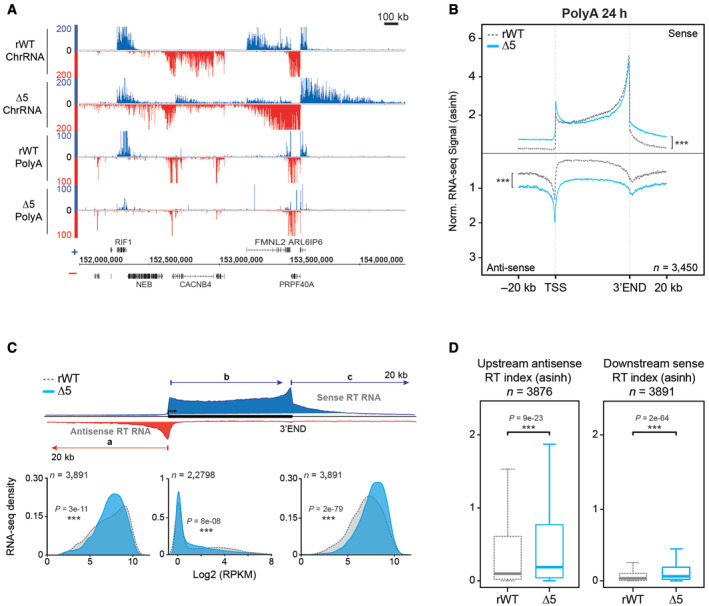

The CTD‐Δ5 deletion leads to a massive read‐through phenotype

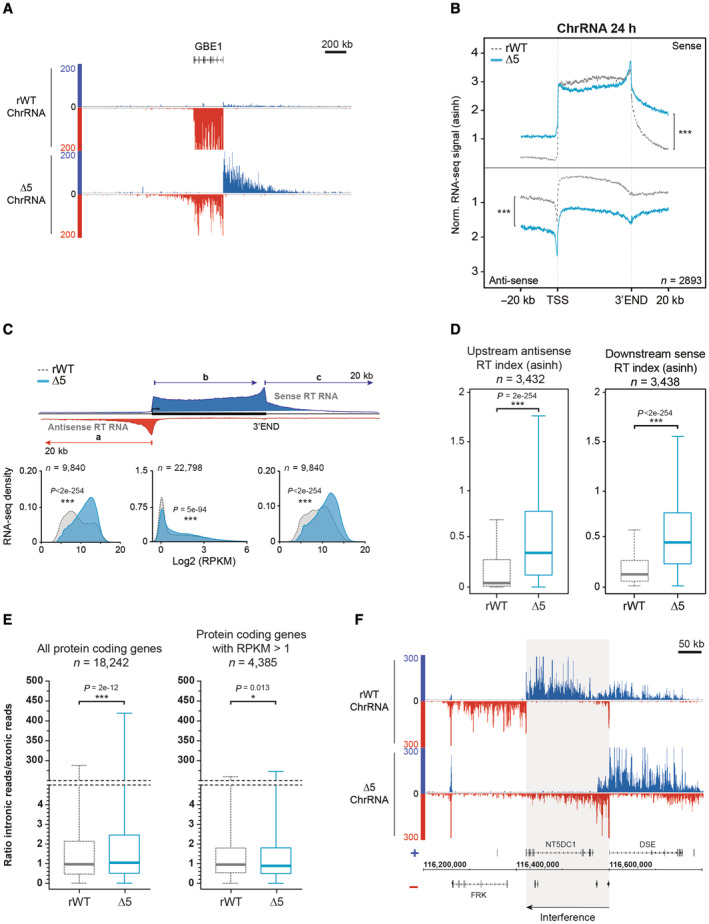

The large overlap of target genes with the YFFF mutant suggested similarity in the phenotypes. Analysis of the ChrRNA‐seq in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant revealed a massive read‐through (RT) phenotype at both 3′ and 5′ ends of genes (in sense and antisense orientation, respectively, Fig 2A). This RT phenotype is clearly more pronounced in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant than in the YFFF mutant (Figs 1E and EV2A). Average profiling on protein‐coding genes shows that the effect is global when scaling the signals on the gene bodies (Figs 2B and EV2B). This conclusion also holds when signals are scaled to read numbers (Fig EV2C). The 3′ and 5′ RT phenotype was independently confirmed by plotting the densities of the transcripts over the gene bodies and the surrounding 20 kb regions upstream of the TSS in antisense orientation (AS) and downstream of the TES in the sense direction (S) (Fig 2C). Transcript levels over gene bodies (middle panel, b in the scheme) show a bimodal distribution, representing low and moderately/highly expressed genes. Both the YFFF and CTD‐Δ5 mutants display a flattening of the distribution compared to rWT (Fig EV2D), with a global decrease in the first Gaussian and spreading of the second both right and left, consistent with a global and massive alteration of the transcriptome. The distributions of the 5'AS (a in the scheme) and 3'S (c in the scheme) signals of the 20 kb regions surrounding the gene bodies indicate an opposite trend, with higher intergenic signals on average for both mutants but more pronounced in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant (Fig EV2D). Assessment of upstream AS and downstream S RT indices confirmed the higher RT in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant as compared to the YFFF mutant and the rWT control (Figs 2D and EV2E). Although we cannot completely rule out that the apparent read‐through phenotype of the CTD‐Δ5 originates from transcript retention on the chromatin, we believe this hypothesis unlikely since it would imply that WT cells produce such transcripts to a massive level, which has never been described. We also observed that intronic reads generally tend to increase in the mutant context as compared to exonic reads, but that this difference becomes reduced when considering genes with higher expression, suggesting a mild splicing defect in the CTD‐Δ5 context (Fig 2E). Finally, at many locations, we observed an interference phenotype, where either the 5'AS (Fig 2F) or the 3′‐end RT (Fig EV2F) correlated with a reduced transcription of the adjacent gene body. Depending on the gene, we observed apparent interference in both mutants (e.g., SULF2) or only the CTD‐Δ5 mutant (e.g., RUNX3). Altogether, these observations demonstrate that the CTD‐Δ5 mutant is able to transcribe over complete gene bodies and beyond with a massive RT phenotype.

Figure 2. CTD‐∆5 mutant exhibits a massive read‐through in sense and antisense transcription.

- Example of ChrRNA read‐through phenotype at the 5′ (antisense) and 3′ (sense) ends in CTD‐∆5 at the GBE1 locus.

- Average metagene profiles of ChrRNA‐seq signals in sense and antisense directions (top and bottom, respectively) over the gene bodies of expressed protein‐coding genes and the 20 kb upstream and downstream surrounding regions in rWT (dotted gray line) and CTD‐∆5 (blue). Profiles were asinh transformed and normalized over the gene bodies of the rWT for the CTD‐∆5. P‐values associated with read‐through were calculated using a two‐sided Wilcoxon test: 8e‐146 in sense and 5e‐165 in antisense. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. See Fig EV2B for comparison with YFFF mutant and EV2C for non‐normalized profiles.

- Density plots of ChrRNA‐seq signals in rWT and CTD‐∆5 mutant on protein‐coding genes (a) The antisense 20 kb region upstream of genes (b) The sense gene body and (c) The sense 20 kb region downstream of genes in rWT (light gray) and CTD‐∆5 (blue). Upstream and downstream regions are selected to exclude those having neighboring genes in a 20 kb window. RPKM, Reads per kilobase per million mapped reads. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests. See Fig EV2D for comparison with YFFF mutant.

- Boxplots of ChrRNA read‐through (RT) indexes based on signal over 20 kb upstream (antisense) and 20 kb downstream (sense) regions of coding genes in rWT (dotted gray line) and CTD‐∆5 mutant (blue). Units are asinh transformed. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. Boxplots represent minimal and maximal values, first and third quartiles with median value as central band. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests. See Fig EV2E for comparison with YFFF mutant.

- Boxplots of the ratios of intronic reads over exonic reads on protein‐coding genes in rWT (light gray) and CTD‐∆5 (blue). Left: All protein‐coding genes containing introns (n = 18,242). Right: Protein‐coding genes with RPKM > 1 in the two strains (n = 4,385). Experiments were done in biological duplicates. Boxplots represent minimal and maximal values, first and third quartiles with median value as central band. P‐values were calculated using a two‐sided Wilcoxon test. RPKM, Reads per kilobase per million mapped reads.

- Example showing potential transcriptional interference of the NT5DC1 gene due to antisense transcriptional read‐through at the promoter of DSE gene in CTD‐∆5 mutant. See Fig EV2F for additional examples.

Source data are available online for this figure.

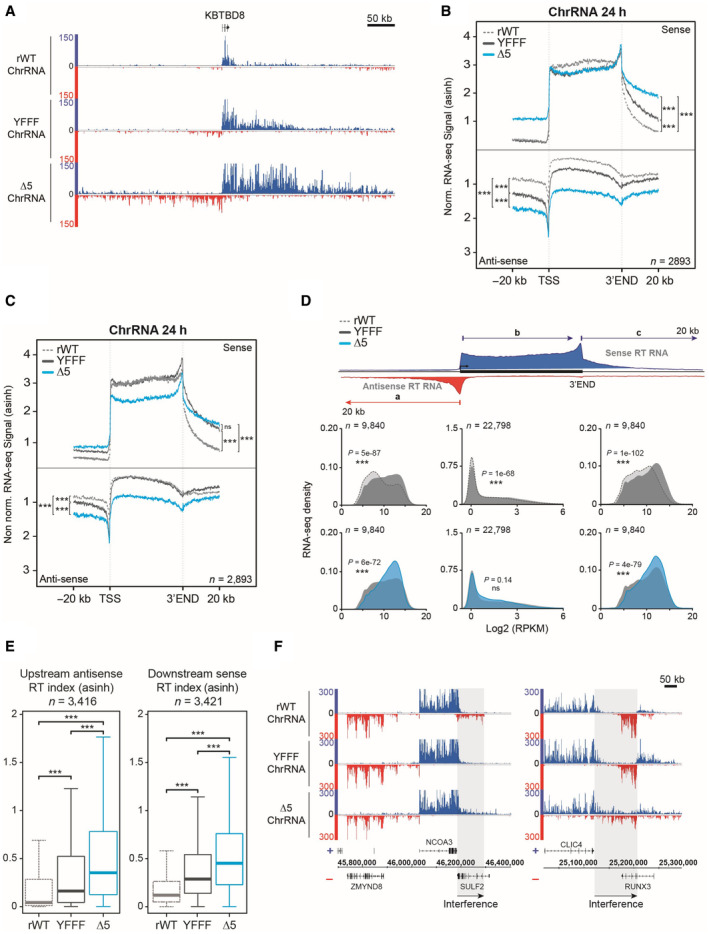

Figure EV2. ChrRNA read‐through phenotype is more pronounced in CTD‐∆5 compare with YFFF mutant.

- Example of read‐through phenotype in ChrRNA‐seq datasets YFFF and CTD‐∆5 at the 5′ (antisense) and 3′ (sense) ends of the KBTBD8 gene compared with rWT.

- Average metagene profiles of ChrRNA‐seq signals in sense and antisense directions (top and bottom, respectively) over the gene bodies of expressed protein‐coding genes and the 20 kb upstream and downstream surrounding regions in rWT (dotted gray line), YFFF (dark gray line) and CTD‐∆5 (blue). All profiles are asinh transformed and normalized over the gene bodies of the rWT for the mutants. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests. P‐values associated with read‐through in sense direction: rWT vs. YFFF = 2e‐70, rWT vs. CTD‐∆5 = 8e‐146, and CTD‐∆5 vs. YFFF = 1e‐87. For read‐though in antisense direction: rWT vs. YFFF = 9e‐121, rWT vs. CTD‐∆5 = 5e‐165, and CTD‐∆5 vs. YFFF = 2e‐146.

- Average metagene profiles of ChrRNA‐seq signals in sense and antisense directions (top and bottom, respectively) over the gene bodies of expressed protein‐coding genes and the 20 kb upstream and downstream surrounding regions in rWT (dotted gray line), YFFF (dark gray line) and CTD‐∆5 (blue). Profiles are asinh transformed and non‐normalized on gene bodies. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests. P‐values associated with read‐through in sense direction: rWT vs. YFFF = 5e‐109, rWT vs. CTD‐∆5 = 2e‐112, and CTD‐∆5 vs. YFFF = 0.41. For read‐though in antisense direction: rWT vs. YFFF = 8e‐152, rWT vs. CTD‐∆5 = 4e‐154, and CTD‐∆5 vs. YFFF = 4e‐17.

- Density plots of ChrRNA‐seq signals in rWT, YFFF, and CTD‐∆5 mutant on protein‐coding genes (a) The antisense 20 kb regions upstream of genes (b) The sense gene body and (c) The sense 20 kb regions downstream of genes in rWT (light gray), YFFF (dark gray), and CTD‐∆5 (blue). Experiments were done in biological duplicates. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests. RPKM, Reads per kilobase per million mapped reads.

- Boxplots of ChrRNA read‐through (RT) indexes based on signal over 20 kb upstream (antisense) and downstream (sense) regions of coding genes in rWT (dotted gray line), YFFF (dark gray), and CTD‐∆5 mutant (blue). Units are asinh transformed. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. Boxplots represent minimal and maximal values, first and third quartiles with median value as central band. P‐value associated with antisense RT index in rWT vs. YFFF = 2e‐90, rWT vs. CTD‐∆5 = 4e‐254, and CTD‐∆5 vs. YFFF = 8e‐71. Concerning downstream RT indexes: rWT vs. YFFF = 5e‐181, rWT vs. CTD‐∆5 < 2e‐254, and CTD‐∆5 vs. YFFF = 2e‐66.

- Examples of ChrRNA‐seq signals showing potential transcription interference of SULF2 and RUNX3 in YFFF and CTD‐∆5 mutants due to RT in sense direction from NCOA3 and CLIC4, respectively.

Source data are available online for this figure.

The CTD‐Δ5 deletion results in global transcriptional spreading and loss of Pol II accumulation at 5′ and 3′ ends of the genes

The massive pervasive transcriptional phenotype of the CTD‐Δ5 mutant led us to question how Pol II densities were affected at the genome‐wide scale. We therefore performed ChIP‐seq in the rWT and CTD‐Δ5 contexts and profiled the enrichment at various genome locations. After checking the HA ChIP enriched for Pol II on highly expressed target in both backgrounds (Fig EV3A), we prepared libraries for further high‐throughput sequencing. A representative example of the data over a large region is shown in Fig 3A. The general signal‐to‐noise ratio is impacted in the mutant, with significantly less signal at gene ends and gene bodies. This is best represented by a metaprofile over protein‐coding genes (Figs 3B and EV3B), which highlights a significant decrease in promoter recruitment and the absence of 3′‐end pause. Once again, CTD‐Δ5 recapitulated the YFFF mutant phenotype, albeit with more severity (Shah et al, 2018; please note that YFFF experiments in this article were performed after 48 h of α‐amanitin treatment). In the case of the 3′‐ends, we previously described that the YFFF mutant Pol II did pause on average 2.6 kb downstream of the natural termination sites. The CTD‐Δ5 seems to have completely lost this ability, suggesting a major impairment in termination.

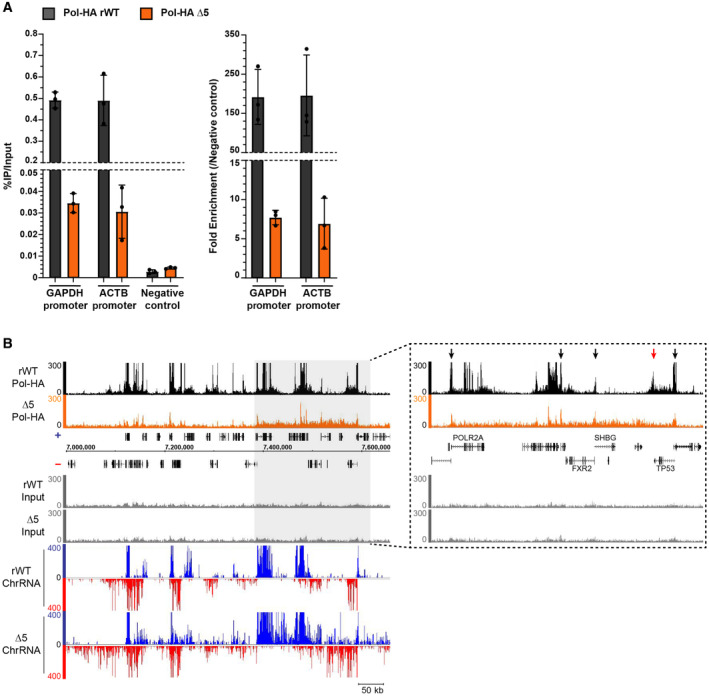

Figure EV3. Pol II accumulation is reduced at promoters in CTD‐∆5 context and lost at 3′ end of coding genes.

- qPCR showing the enrichment of Pol‐HA ChIP on positive regions compared with negative control in rWT (black) and CTD‐∆5 (orange). Left: Percentage of IP over Input for each target. Right: Fold enrichment normalized on negative control. Error bars represent the mean with SD of 3 technical replicates.

- Example of Pol‐HA ChIP‐seq signal in rWT (black) and CTD‐∆5 (orange) as well as their associated Input profiles and ChrRNA signals. Light gray rectangle highlights a region in which there is a global accumulation of Pol‐HA in CTD‐∆5 associated with read‐through at ChrRNA level. Right: Extended view of the region highlighted in light gray. Black arrows show promoter‐associated Pol‐HA accumulation in both rWT and CTD‐∆5. Red arrow shows 3′‐end Pol‐HA accumulation in rWT, which is lost in CTD‐∆5 mutant. Experiments were done in biological duplicate, however, only the sample with the best signal‐to‐noise ratio was used for subsequent analysis.

Figure 3. CTD‐∆5 displays strong accumulation defects at both ends of protein‐coding genes.

- Example of Pol‐HA ChIP‐seq showing global spreading of Pol II along the genome accompanied by a loss of Pol II accumulation on coding genes in CTD‐∆5 (orange) compared with rWT (black) and their associated ChrRNA signal.

- Average metagene profiles of Pol II signal over gene bodies of protein‐coding genes and the 10 kb surrounding region for the top 10% of expressed coding genes in rWT (black) and the corresponding in CTD‐∆5 (orange). Right panels: Zoom at TSS (top) and 3′ end (bottom). Experiments were done in biological duplicates, however, only the sample with the best signal‐to‐noise ratio was used for subsequent analysis. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests.

- Average metagene profiles comparing Pol II, H3K4me3, and H3K4me1 signals on active promoters (top) and active enhancers (bottom) in rWT and CTD‐∆5. Enhancer selection is from Shah et al (2018). Experiments were done in biological duplicates, however, only the sample with the best signal‐to‐noise ratio was used for subsequent analysis. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We also analyzed Pol II recruitment and active epigenetic marks at putative enhancer locations (Fig 3C and D). Surprisingly, we observed that, while altered, Pol II accumulation was far less reduced than at the promoters. This observation indicates that the loss of accumulation of Pol II at promoters and 3′‐ends is relatively specific in the context of the CTD‐Δ5 mutant, which retains an ability to be recruited at distal regulatory sequences. Active epigenetic marking was essentially unaffected.

Altogether our data indicate that the CTD is crucial for proper transcription termination. The CTD appears also dispensable for the correct recruitment of Pol II, most likely at promoters, and the process of transcription per se. Whenever engaged in transcription, the CTD‐Δ5 mutant does not seem able to leave DNA nor to accumulate at promoters and 3′‐ends, with the noticeable exception of the enhancers.

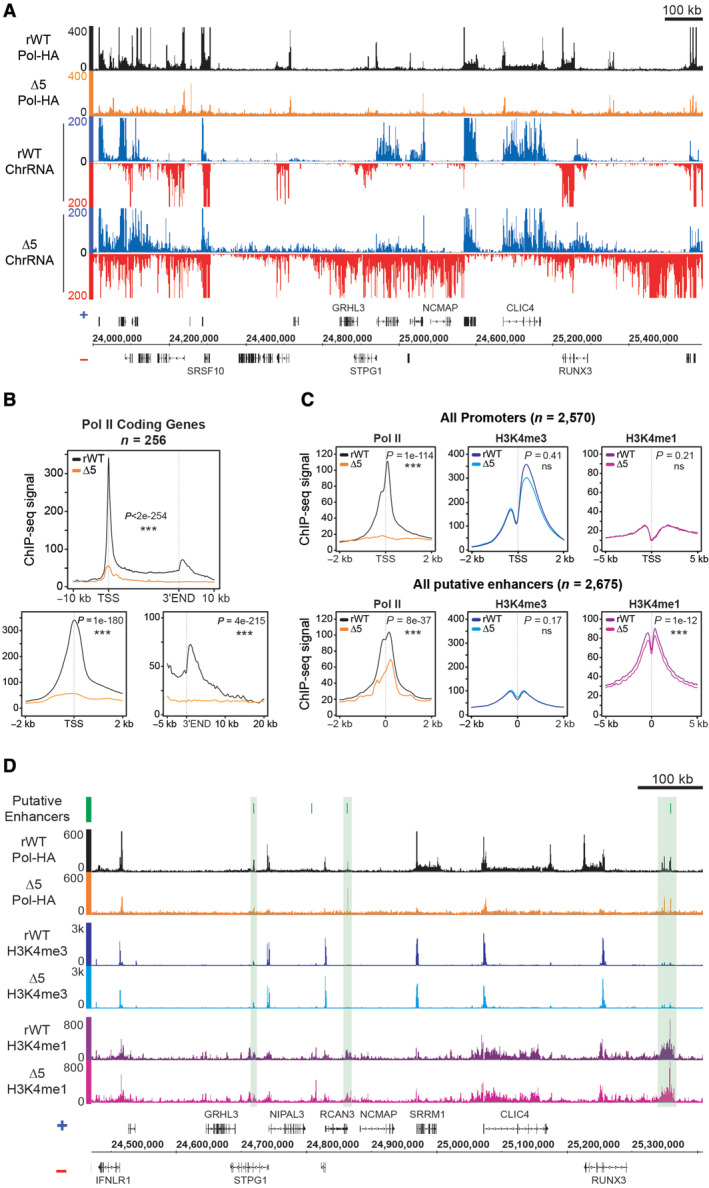

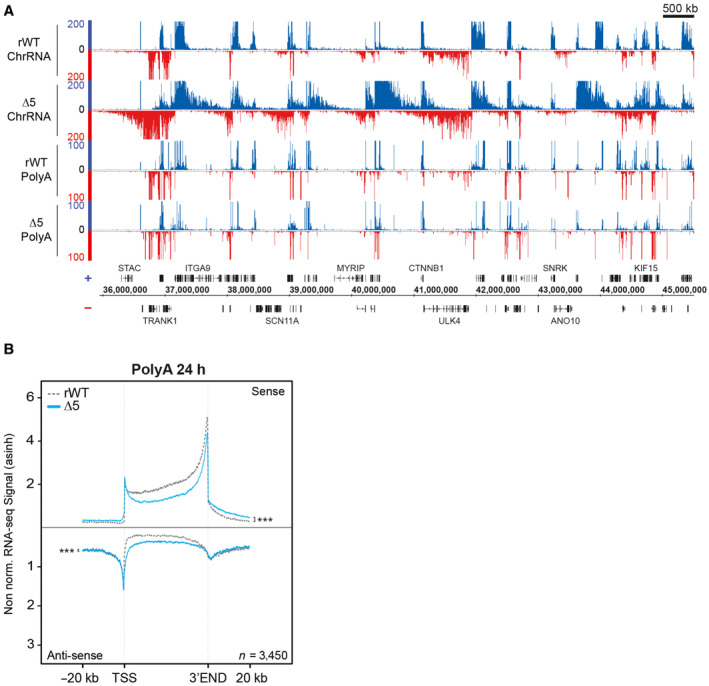

CTD‐Δ5 deletion yields a dysregulation in polyadenylated RNAs

We next interrogated the processing and polyadenylation of the CTD‐Δ5 RT transcripts by polyA RNA‐seq. We observed less signal over the gene bodies and a higher accumulation of signals upstream antisense and downstream sense as compared to the rWT control (Figs 4A and EV4A). Average profiling of polyA RNA‐seq signals on protein‐coding genes using different normalization approaches confirmed these observations genome‐wide (Figs 4B and EV4B). We independently plotted the signal densities on the gene bodies and the surrounding 20 kb regions (Fig 4C). Our analysis showed that the CTD‐Δ5 mutant signals over the gene bodies (b in the scheme) significantly shift to the left as compared to the rWT. The effect on the upstream (AS—a in the scheme) and downstream (S—c in the scheme) 20 kb regions is, however, more subtle in the polyA as compared to nascent ChrRNAs. This observation is further validated by the upstream AS and downstream S RT indices (Fig 4D). Our results suggest a slight pervasive polyA signal before and after coding gene boundaries in the context of the CTD‐Δ5 mutant. However, it is difficult to conclude whether this observation results from the polyadenylation of pervasive transcripts or from the contamination of non‐polyA RT transcripts in the frame of those experiments. Finally, we cannot exclude that these signals arise from WT endogenous Pol II transcripts that would have been stabilized by the action of α‐amanitin as previously described (Meininghaus et al, 2000). The fact that RT of CTD‐Δ5 mutant polyA RNA is less pronounced than that of the YFFF mutant could be explained by the treatment times, since CTD‐∆5 are extracted after 24 h of α‐amanitin addition while those from YFFF after 48 h. However, this could also reflect the lower likelihood of a CTD‐depleted Pol II to recruit the polyA Polymerase (PAP). Altogether, we show an impaired polyA transcriptome in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant context.

Figure 4. CTD‐∆5 read‐through transcription is less pronounced for polyadenylated transcripts.

- Example showing ChrRNA‐seq (top) and its associated polyA RNA‐seq signals (bottom) in rWT and CTD‐∆5. See Fig EV4A for additional examples on a wider view.

- Average metagene profiles of polyA RNA‐seq signals in sense and antisense directions (top and bottom, respectively) over the gene bodies of expressed protein‐coding gene and the 20 kb upstream and downstream surrounding regions in rWT (dotted gray line) and CTD‐∆5 mutant (blue). Profiles were asinh transformed and normalized over the gene bodies of the rWT for the CTD‐∆5. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. P‐values associated with read‐through were calculated using a two‐sided Wilcoxon test: 2e‐138 in sense and 3e‐129 in antisense. See Fig EV4B for non‐normalized profiles.

- Density plots of polyA RNA‐seq signals in rWT and CTD‐∆5 mutant (a) The antisense 20 kb regions upstream of genes (b) The sense gene body and (c) The sense 20 kb regions downstream of genes in rWT (light gray) and CTD‐∆5 (blue). Upstream and downstream regions are selected to exclude those having neighboring genes in a 20 kb window. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. RPKM, Reads per kilobase per million mapped reads. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests.

- Boxplots of polyA read‐through (RT) indexes based on signal over 20 kb upstream (antisense) and 20 kb downstream (sense) regions of coding genes in rWT (dotted gray line) and CTD‐∆5 mutant (blue). Units are asinh transformed. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. Boxplots represent minimal and maximal values, first and third quartiles with median value as central band. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests. See Fig EV2E for comparison with YFFF mutant.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV4. Polyadenylated transcripts are less affected by CTD‐∆5 mutation.

- Wide view example of ChrRNA‐seq and its associated polyA signal in rWT and CTD‐∆5.

- Average metagene profiles of polyA RNA‐seq signals in sense and antisense directions (top and bottom, respectively) over the gene bodies of expressed protein‐coding genes and the 20 kb upstream and downstream surrounding regions in rWT (dotted gray line) and CTD‐∆5 (blue). All profiles are asinh transformed and non‐normalized over gene bodies. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. P‐values associated with read‐through were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests: 4e‐53 in sense and 9e‐4 in antisense.

CTD deletion leads to Pol II interactome impairment

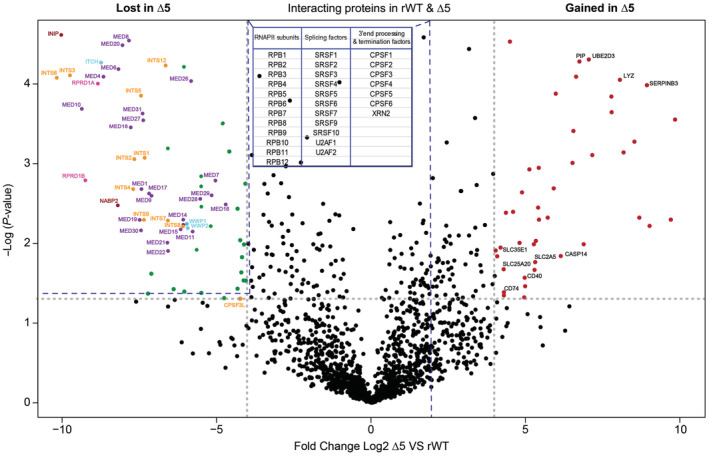

To further dissect the impact of the CTD truncation in living cells, we immunoprecipitated Pol II and analyzed its associated proteins in rWT and mutant CTD‐Δ5 expressing cells by mass spectrometry (MS; Fig 5). The pool of proteins lost in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant vs. rWT recapitulates what we observed in the YFFF mutant (Shah et al, 2018); namely a marked loss of both the Mediator (23 out of 31 subunits) and Integrator (11 of 12 subunits) complexes, both major interacting partners of the Pol II CTD (Baillat et al, 2005). The Mediator CDK module was not detected in the rWT, in agreement with previous observations (Shah et al, 2018). Interestingly, subunits of the SOSS complex (INIP and NABP2), which is involved in the maintenance of genomic stability (Huang et al, 2009), scaffold proteins for CTD phosphatases (RPRD1A, RPRD2B; Ni et al, 2014) and ubiquitin ligases (WWP1, WWP2, and ITCH) were also lost, suggesting a possible link between transcription, DNA repair, dephosphorylation, and protein degradation. The complete list of proteins lost in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant context as well as details of the MS experimental results (fold change, P‐values, peptide counts) are summarized in Dataset EV1.

Figure 5. Mass spectrometry differential analysis of rWT and CTD‐∆5 interactomes.

Volcano plot comparing the Pol II interactome in rWT and CTD‐∆5 mutant. Left: Proteins lost in CTD‐∆5, Right: Proteins enriched in CTD‐∆5. Highlighted are the subunits of the Mediator (purple) and Integrator complexes (orange) CTD phosphatases scaffolds (pink), ubiquitin ligases (light blue), and SOSS complex subunits (red). In black are highlighted some chosen interactors gained by the CTD‐∆5 Threshold: log2 fold change ≥ 4; P‐value < 0.05. Data based on three independent biological replicates. See also Datasets EV1 and EV2 for a detailed list of lost and gained proteins in the CTD‐∆5 mutant context, respectively. The table in the figure sums up the proteins that do not change significantly; dotted lines connected to the table represent the region where these proteins are found in the volcano plot. See Dataset EV3 for the details (P‐values, fold change, and peptide count).

Similar to the YFFF mutant, no significant loss of the cleavage and polyadenylation (CPA) complexes, XRN2, or the splicing factors was observed in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant. However, we also observed the interesting loss of SPT6 in the mutant context (Dataset EV1), whose loss has been previously linked to a termination defect (Narain et al, 2021), albeit less globally than the phenotype we describe here. Intriguingly, the CTD‐Δ5 mutant also gained specific interactions. They include proteins involved in inflammation, stress response, and protein degradation, such as Lysozyme (Lyz), SerpinB3, Prolactin‐inducible protein (PIP), ubiquitin‐conjugating enzyme E2 D3 (UBE2D3), and Caspase 14 subunits (CASP14). Among the proteins that were enriched were lymphoid surface markers (CD40 and CD73) as well as many membrane solute carriers (SLC2A5, SLC35E1, and SLC25A20). These interactions could originate from RPB1 misfolding during protein synthesis (most of the gained proteins go through the endoplasmic reticulum for their synthesis), and a significant proportion of the CTD‐Δ5 mutant could be directed to degradation. The complete list of protein interactions gained in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant context as well as details of the MS experimental results (fold change, P‐values, peptide counts) are summarized in Dataset EV2.

Overall, our MS data shed light on a major loss of both the Int and Med complexes, a phenotype that emphasizes the importance of these two complexes in Pol II CTD function and link to transcription. This loss was also observed in the YFFF mutant in which RT and altered termination were present.

CTD deletion impairs the maturation of snRNA and nonpolyadenylated histone transcripts

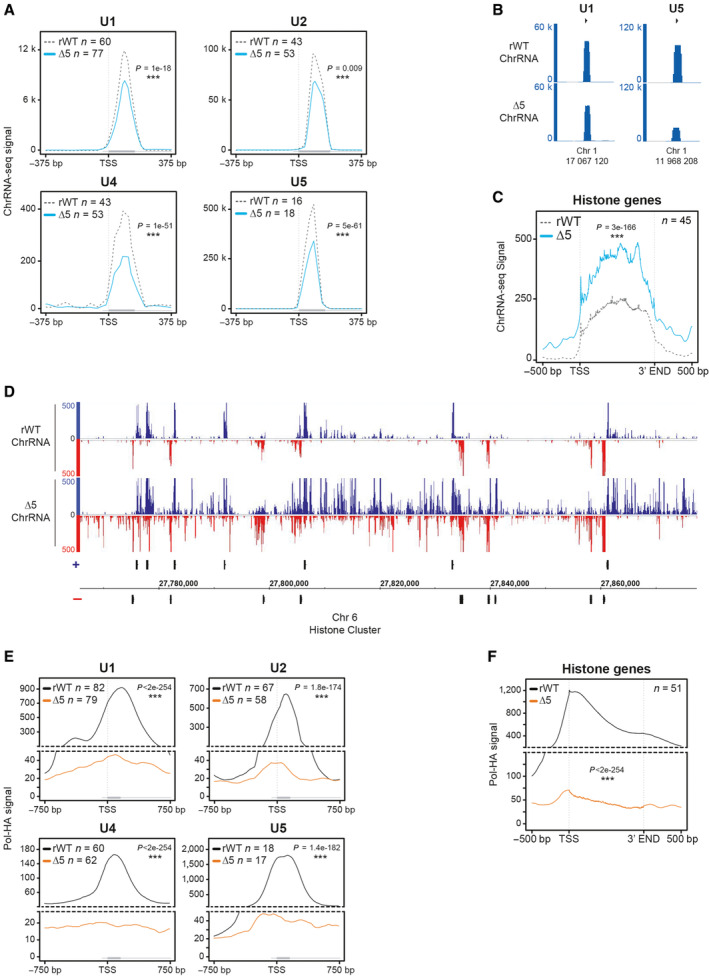

To investigate the impact of the CTD deletion on the transcription of noncoding and nonpolyadenylated protein genes, we analyzed the snRNA and histone coding genes. Profiling of ChrRNA‐seq signals on snRNA genes revealed that the CTD‐Δ5 mutant impacts more specifically U4 and U5 genes, in the form of a severe downregulation, whereas U1 and U2 were less affected when compared to the rWT control (Fig EV5A). Examples of the ChrRNA signals at individual U1 and U2 genes are shown in Fig EV5B.

Figure EV5. CTD‐∆5 mutation leads to transcriptional misregulation of snRNA and histone genes associated with defects in polymerase II recruitment.

- Average metagene of sense ChrRNA signals at the top 50% of expressed U1, U2, U4, and U5 snRNA genes in rWT (dotted gray line) and CTD‐∆5 mutant (blue line) Gray rectangles indicate the corresponding gene size. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests.

- Example of ChrRNA signal at U1 and U5 loci in showing the global downregulation of snrRNA in CTD‐∆5 mutant.

- Average metagene profiles of sense ChrRNA signal at the top 50% of expressed nonpolyadenylated histone genes in rWT (dotted gray line) and CTD‐∆5 (blue line). Experiments were done in biological duplicates. P‐values were calculated using a two‐sided Wilcoxon test.

- Example of ChrRNA signal at histone gene cluster on chromosome 6 illustrating the global upregulation in CTD‐∆5 comparison with rWT.

- Average metagene profiles of Pol II on top 50% of enriched snRNA in rWT (black) and CTD‐∆5 (orange). Experiments were done in biological duplicates. Boxplots represent minimal and maximal values, first and third quartiles with median value as central band. P‐values were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests.

- Average metagene profiles of Pol II on top 50% of most enriched histone genes in rWT (black) and CTD‐∆5 (orange). Experiments were done in biological duplicates. Boxplots represent minimal and maximal values, first and third quartiles with median value as central band. P‐values were calculated using a two‐sided Wilcoxon test.

We also found that nonpolyadenylated histone gene transcription was apparently increased in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant context as compared to the YFFF mutant and the rWT control (Fig EV5C). Examples of the ChrRNA signals on a representative non‐polyA histone cluster are shown in Fig EV5D. Finally, the processing of ChIP‐seq indicated that poor Pol II recruitment could be observed at both histone and snRNA gene locations (Fig EV5E and F). Overall, our results indicate that nonpolyadenylated gene transcription and/or processing are severely impaired in the context of a CTD depletion. In the case of snRNA genes, one could speculate that spliceosome retention in the chromatin fraction of the nucleus could cause this defect. Our data also suggest that the CTD requirement is variable, depending on the specific gene category (U snRNA and replication‐dependent histone genes).

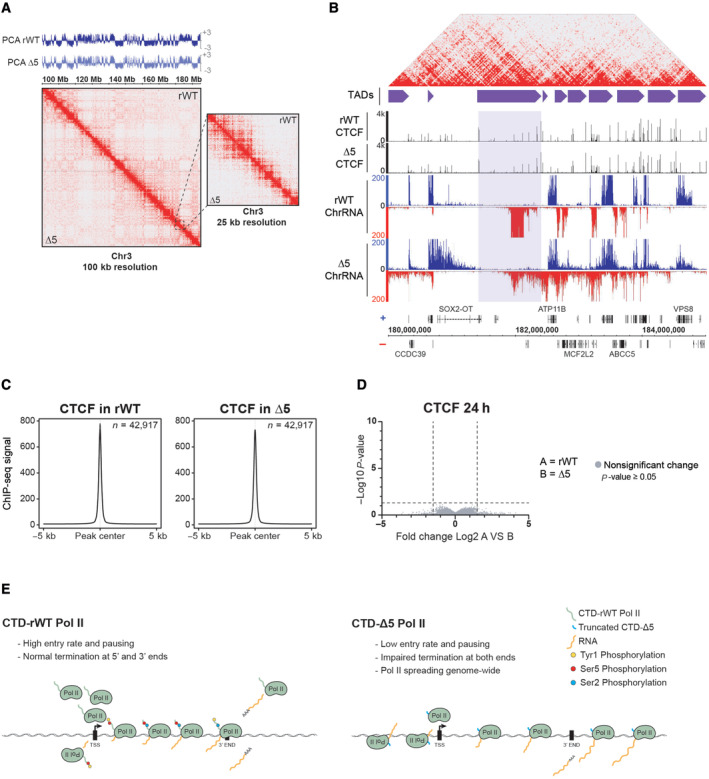

Pervasive transcription does not impair long‐distance interactions

Previous reports indicated that read‐through transcription and termination defects in the context of viral infection could alter TAD borders or TAD structure (Heinz et al, 2018). We wondered if this was also the case when the CTD was absent on the transcribing Pol II and performed HiC experiments in both the rWT and CTD‐Δ5 contexts described above. To address this question, we prepared chromatin and processed samples for HiC to further examine 3D maps, TADs, and A and B compartments. HiC maps for examples of large and more focused views, comparing rWT and CTD‐Δ5, are shown in Fig 6A over the human chromosome 13. Most domains and borders were found virtually identical in both cellular environments. Furthermore, the A and B compartments, scoring for areas of high or low levels of interactions and reflecting active and inactive domains chromatin, respectively, did not show any differences. We then investigated whether RT transcription occurring over the TAD borders could perturb CTCF binding. To this aim, we performed CTCF ChIP‐seq in rWT and mutant backgrounds. A representative profile of this experiment is shown in Fig 6B and a more global analysis in Fig 6C. No changes were observed at most CTCF sites bound by the protein, which was even confirmed by a more systematic assessment using DESeq analysis (Fig 6D). However, as shown in Fig 6B, we could spot examples of Pol II massively transcribing over TAD borders.

Figure 6. CTD‐∆5 polymerases are transcribing through TAD borders without disturbing 3D genome organization and CTCF binding patterns.

- HiC maps and PCA comparing long‐range interactions of rWT and CTD‐∆5. A portion of chromosome 3 at 100 kb resolution is shown. PCA is indicated above the HiC maps in rWT (dark blue) and CTD‐∆5 mutant (light blue). PCA, principal component analysis illustrate compartments A and B (positive and negative values, respectively). Experiments were done in biological duplicates. Right panel: zoom at 25 kb resolution of the region surrounded by the dotted black line.

- Example of CTD‐∆5 polymerases transcribing through TAD borders marked by CTCF sites (highlighted in light purple). HiC map on top represents the rWT interactions shown in the zoom in panel (A). Purple boxes represent TADs called in human B cells (GM12878 from Rao et al (2014). CTCF ChIP‐seq in rWT and CTD‐∆5 are both shown in black and their associated ChrRNA‐seq signals are also shown.

- Average metagene profiles of CTCF signal focusing on peak center and 5 kb surrounding regions in rWT and CTD‐∆5. Experiments were done in biological duplicates. See Materials and Methods for peak selection.

- Volcano plot of differentially enriched CTCF peaks in B relative to A after 24‐h α‐amanitin treatment (threshold: P‐value < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5). Experiments were done in biological duplicates. No significant changes were found in CTCF binding pattern in CTD‐∆5.

- Working model illustrating the ability of the CTD‐∆5 mutant to be recruited at promoters and perform transcription despite major termination defects.

We conclude from these experiments that the pervasive transcription yielded by the CTD‐Δ5 Pol II did not generate major changes in TAD structure or A/B compartmentation, and did not affect the binding patterns of CTCF, in contrast with previous reports of pervasive transcription following viral infection (Heinz et al, 2018; Zhao et al, 2018).

Discussion

To our surprise and challenging previous studies, the Pol II CTD‐Δ5 mutant seems to retain transcriptional activity in living cells on endogenous chromatin. This activity is not restricted to specific genes or loci but takes place genome‐wide. The apparent discrepancy with published works (Gerber et al, 1995; Meininghaus & Eick, 1999; Lux et al, 2005) can be explained, at least in part, by their different technical approaches. While some of the previous studies described a loss of transcripts in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant at individual genes using total RNA quantification by northern blot (Meininghaus & Eick, 1999), we used a dedicated fractionation protocol that allows for nascent transcript determination genome‐wide. Another study investigated a few hundred targets in run‐on experiments (Meininghaus et al, 2000), but in this framework, the transcription reaction is allowed to go on for one round only, which might not be enough to accumulate detectable levels of transcripts in the CTD‐Δ5 mutant context. Finally, FRAP experiments indicated that CTD‐Δ5 Pol II mutant displays a high take‐off rate in living cells. Combining our present work with these previous observations, we propose that a CTD‐depleted Pol II has a low entry frequency on chromatinized DNA. However, once recruited and engaged in transcription, these mutant Pol II enzymes retain transcriptional activity and the ability to elongate but have lost their ability to properly terminate transcription, as previously described for a Tyrosine mutant (Fig 6E). Future experiments and analysis should help us clarify whether these mutant Pol II can properly perform polyadenylation and splicing as well as transcribing other ncRNAs such as eRNAs.

The CTD‐Δ5 mutant mainly recapitulates the YFFF mutant phenotype, namely a global dysregulation of transcription termination concomitant with a loss of interaction with the Mediator (Med) and Integrator (Int) complexes. This further validates the role of the Tyr1 residue as a safeguard preventing pervasive transcription in mammalian cells, as mutation or deletion of these residues in the CTD yields similar phenotypes. The implication of the Med and Int complexes in the molecular process of termination control is also reinforced by these data. Our previous work, however, indicated that Ser2 mutant (S2AAA) results in partial Med loss with no effect on Int recruitment, whereas no major termination phenotype is observed (Shah et al, 2018). This observation suggests a more crucial Int contribution to the termination control process, in agreement with recent reports (Elrod et al, 2019; Dasilva et al, 2021; Lykke‐Andersen et al, 2021). Moreover, and as in the YFFF context, we also observed a loss of interaction with the Med complex. While we do not provide direct evidence for a possible involvement of this complex in termination, a recent study has described a defect in nascent transcription (Jaeger et al, 2020) for Med mutants that seem consistent with such a phenotype. We propose that the loss of these two complexes essentially explains the termination defect in the absence of CTD repeats, although we cannot formally rule out that other gene(s) with impaired expression might contribute to the transcriptional phenotype of CTD‐Δ5.

While a recent study proposed that long‐distance interactions could be altered by the localized loss of termination following viral infection (Heinz et al, 2018), we did not observe such a phenotype in our experiments with CTD‐depleted Pol II. This difference might originate from different mechanisms at play but also from technical artifacts such as the depth of sequencing or the fact that the optimal induction of the CTD‐Δ5 is analyzed after 24 h, a time frame that might not be sufficient to abolish the robustness of the existing long‐range interactions. We do not rule out, however, that a massive pervasive elongating Pol II might not be sufficient to disrupt these interactions.

Our present study thus establishes the nonessentiality of the CTD (with the exception of the 5 repeats required for RPB1 stability) for transcription in living cells. The CTD might not be necessary for the act of transcription per se but rather for the accurate recruitment of the enzyme to its target locations, regulation of transcription‐coupled processes, and the correct maturation of transcripts. Despite the nonsignificant loss of recruitment of the spliceosome and CPA complexes to the CTD‐Δ5 mutant, as revealed by our MS data (Dataset EV3), we could not conclude whether the CTD‐Δ5 transcripts are processed or not (3′ cap, splicing, polyA tail), as stabilization of the endogenous transcripts cannot be ruled out in this context. Furthermore, the experiments were performed after only 24 h of α‐amanitin treatment. While this is more than sufficient to block the endogenous polymerase, it might be too short for the turnover of cytoplasmic transcripts. The CTD remains essential for cell viability and correct gene expression, a phenotype that is in contrast with that of shorter CTD deletions that still allow sustained transcription in a set‐up similar to ours (Sawicka et al, 2021). Finally, a recent report using a CTD degradable system has described that the domain is not required for maintaining pausing nor for the postinitiation steps of transcription (Gerber & Roeder, 2020). While our results are consistent with these observations, we also demonstrate that the engaged CTD‐Δ5 do not seem to pause and have an impaired transcription termination. With this paper, we provide a missing standard for all past and future CTD manipulation studies, namely that a complete defect of the CTD results primarily, from a transcriptional point of view, in a massive pervasive phenotype. Thus, such effects observed for other mutations, such as YFFF, relate to one of the major functions of the domain.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies specific for haemagglutinin (HA)‐tag (3F10, Roche or 12CA5, Sigma), Rpb1 (F12, Santa Cruz), and α‐Tubulin (T9026, Sigma) were used for western blot analysis. For ChIP‐seq experiments, anti‐(HA)‐tag antibody (ab9110, Abcam), anti‐H3K4me1 (ab8895, Abcam), anti‐H3K4me3 (ab8580, Abcam), and anti‐CTCF antibody (C15410210, Diagenode) were used.

Construction of the CTD mutants

CTD sequences of rWT and YFFF with an optimized human codon usage were synthesized by Gene Art (Regensburg, Germany) and cloned into LS*mock vector (Meininghaus et al, 2000; Shah et al, 2018). CTD‐Δ5 was cloned as previously described (Meininghaus et al, 2000). All final constructs were sequenced before usage.

Establishing stable cell lines

Raji cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamax (Gibco, Invitrogen) at 37°C, and 5% CO2. Cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination before subsequent experiments. Full‐length Rpb1 expression vectors (rWT, YFFF, and Δ5) were transfected into Raji cells using 1 × 107 cells (10 μg plasmid, 960 μF, 250 V). Polyclonal cell lines were established after selection with G418 (1 mg/ml) for 2–3 weeks. Tetracycline was removed to induce the expression of recombinant Rpb1 by washing the cells three times with 50 ml of phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 1% FCS (Gibco, Invitrogen). Twenty‐four hours after induction, cells were cultured in the presence of 2 μg/ml of α‐amanitin (Sigma) to inhibit endogenous Pol II. Cells were harvested after 24 or 48 h of α‐amanitin treatment to perform western blot analysis. For other experiments, cells were harvested after 24 h of α‐amanitin treatment since Δ5 is unstable after 48 h (Fig 1C).

Viability curve

Viability of rWT, CTD mutants, and wild‐type Raji cells was monitored over a period of 10 days (Fig 1C). For all cell lines, 20 × 106 cells were induced at day 0 and supplemented with α‐amanitin after 24 h. The percentage of living cells was calculated every day using trypan blue staining.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed twice with PBS and directly lysed with 2× Laemmli buffer. Whole‐cell lysates were separated on SDS–PAGE (6.5% gel) and blotted on a nitrocellulose membrane (GE HealthCare). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk/TBS‐T solution for 1 h and incubated overnight with the primary antibody at 4°C. Afterward, the membranes were washed three times with TBS‐T and incubated with the corresponding HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies against rat (Sigma) or mouse (Promega) to allow detection of the target proteins by chemiluminescence.

Purification of Pol II interacting proteins for mass spectrometric analysis

For purification of recombinant Rpb1, α‐HA antibody (12CA5) was coupled to sepharose A/G beads for 4 h at 4°C. Simultaneously, cells (7.5 × 107) were washed twice with ice‐cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP‐40 (Roche), 1× PhosStop (Roche), and 1× protease cocktail (Roche)] for 30 min on ice. Samples were sonicated (Sonifier 250 BRANSON, 3 × 20 cycles, output 5, duty cycle 50) and incubated on a shaker for 1 h at 4°C. Samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min, and the supernatants were incubated with antibody‐coupled sepharose A/G beads overnight at 4°C. Next day, beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and continued with either on‐bead trypsin digest or boiled with 2× Laemmli buffer (95°C, 8 min) to load proteins on SDS–PAGE for the subsequent in‐gel trypsin digest.

On‐beads trypsin digest

Following the standard immunoprecipitation procedure, beads were first washed with lysis buffer (three times) and then with 50 mM NH4HCO3 (ammonium bicarbonate). For trypsin digest, beads were incubated with 100 μl of 10 ng/μl of trypsin solution in 1 M Urea and 50 mM NH4HCO3 for 30 min at 25°C. The supernatant was collected, beads washed twice with 50 mM NH4HCO3 and all three supernatants collected together and incubated overnight at 25°C after the addition of 1 mM DTT. Twenty‐seven millimeter of iodoacetamide (IAA) was then added to the samples and incubated at 25°C for 30 min in dark. Next, 1 μl of 1 M DTT was added to the samples and incubated for 10 min to quench the IAA. Finally, 2.5 μl of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was added to the samples and desalted using C18 stage tips (Ishihama et al, 2006). Samples were evaporated, resuspended in 30 μl of 0.1% formic acid solution, and stored at −20°C until LC–MS analysis.

In‐gel trypsin digest

A standardized protocol was used for in‐gel digestion with minor modifications (Wilm et al, 1996; Shevchenko et al, 2000). The digested peptides were evaporated to 5 μl and resuspended in 30 μl of 0.1% TFA solution prior to desalting by C18 stage tips. Samples were evaporated and resuspended in 30 μl of 0.1% formic acid solution and stored at −20°C until LC–MS analysis.

Liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry

For LC–MS/MS purposes, desalted peptides were injected in an Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano system (Thermo), separated in a 15‐cm analytical column (75 μm ID with ReproSil‐Pur C18‐AQ 2.4 μm from Dr. Maisch) with a 50‐min gradient from 5 to 60% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid. The effluent from the HPLC was directly electrosprayed into a QexactiveHF (Thermo) operated in data‐dependent mode to automatically switch between full scan MS and MS/MS acquisition. Survey full scan MS spectra (from m/z 375 to 1,600) were acquired with resolution R = 60,000 at m/z 400 (AGC target of 3 × 106). The 10 most intense peptide ions with charge states between 2 and 5 were sequentially isolated to a target value of 1 × 105, and fragmented at 27% normalized collision energy. Typical mass spectrometric conditions were: spray voltage, 1.5 kV; no sheath and auxiliary gas flow; heated capillary temperature, 250°C; ion selection threshold, 33,000 counts. MaxQuant 1.5.2.8 was used to identify proteins and quantify by iBAQ with the following parameters: Database, Uniprot_Hsapiens_3AUP000005640_151111; MS tol, 10 ppm; MS/MS tol, 0.5 Da; Peptide FDR, 0.1; Protein FDR, 0.01 Min. peptide Length, 5; Variable modifications, Oxidation (M); Fixed modifications, Carbamidomethyl (C); Peptides for protein quantitation, razor and unique; Min. peptides, 1; Min. ratio count, 2. Identified proteins were considered as interaction partners if their MaxQuant iBAQ values displayed a greater than log2 5‐fold enrichment and P‐value 0.05 (ANOVA) when compared to the rWT control.

PolyA RNA‐seq

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Any contaminating DNA was digested with rigorous TurboDNase (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) treatment according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, this treatment was performed as follows: after incubation with TurboDNase for 37°C for 30‐min samples are not directly subjected to the Stop reagent but instead re‐extracted with Trizol, precipitated, and after resuspension digested again with Turbo DNAse, stopped with Stop reagent, extracted, and finally resuspended in 20 μl water. This was followed by a second extraction with TRIzol reagent to eliminate traces of contaminants. Purified RNA was quantified with Nanodrop 1000 instrument and quality was assessed using RNA Nano or Pico Assay kit with Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA). Only the RNA samples with RIN above 8 were used for subsequent treatments. Polyadenylated RNA was isolated from 5 μg DNase‐treated total RNA sample by two sequential purifications using Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Purified polyA RNA was analyzed on Bioanalyzer using an RNA Pico Assay chip. Libraries were prepared with Small RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, USA) using a modified protocol as follows: 50 ng of polyA enriched RNA was fragmented to ~150 bp by digesting with 1 U of RNaseIII (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) for 10 min at 37°C. Fragmentation reaction was stopped by adding 90 μl nuclease‐free water and quickly adding 350 μl RLT buffer from RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) followed by purification of fragmented RNA using RNA Cleanup Protocol from this kit. However, to enhance the recovery of smaller fragments, we added 500 μl ethanol instead of recommended 250 μl. Twenty‐nanogram RNaseIII fragmented RNA was used as input for ligation of 3′ and 5′ adapters according to Small RNA Library Prep Protocol followed by cDNA synthesis from adapter‐ligated RNA and 10 cycles of PCR amplification. Ampure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter, USA) were used to clean up the amplified library and remove adapter dimers according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified libraries were then analyzed with HS DNA Assay Kit on Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA) and sequenced on Illumina HiSeq2000 platform.

ChrRNA‐seq

Chromatin‐associated RNA was isolated from 20 × 106 cells as described previously (Nojima et al, 2018) followed by rigorous treatment with TurboDNase. After incubation with Turbo DNase for 37°C for 30‐min samples are not directly subjected to the Stop reagent but instead re‐extracted with Trizol, precipitated, and after resuspension digested again with Turbo DNAse, stopped with Stop reagent, extracted, and finally resuspended in 20 μl water. To confirm the absence of remaining contaminant DNA, a qPCR on a coding region of the GAPDH gene was performed prior and after reverse transcription for each sample (Forward primer: 5′‐ATTTGGTCGTATTGGGCGC‐3′ and reverse primer: 5′‐TGAAGGGGTCATTGATGGC‐3′). Before library preparation, any contaminating rRNA was removed with Ribo‐Zero rRNA Removal Kit (EpiCenter or Illumina USA) and libraries were prepared using Small RNA Library Prep Kit as described above for polyA RNA‐seq.

ChIP‐seq

Fifty million cells were crosslinked for 10 min at 20°C with the crosslinking solution (10 mM NaCl, 100 μM EDTA pH 8, 50 μM EGTA pH 8, 5 mM HEPES pH 7.8, and 1% formaldehyde). The reaction was stopped by adding glycine to reach a final concentration of 250 mM. After 5 min of formaldehyde quenching, cells were washed twice with cold PBS and resuspended in cold 2.5 ml LB1 (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8, 10% glycerol, 0.75% NP‐40, 0.25% Triton X‐100) at 4°C for 20 min on a rotating wheel. Nuclei were pelleted down and washed in 2.5 ml LB2 (200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8, 0.5 mM EGTA pH 8, 10 mM Tris–pH 8) for 10 min at 4°C on a rotating wheel. Nuclei were then collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml LB3 (1 mM EDTA pH 8, 0.5 mM EGTA pH 8, 1 mM Tris–pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Na‐Deoxycholate, 0.5% N‐lauroylsarcosine) and sonicated using Bioruptor Pico (Diagenode) in 15 ml tubes for 20 cycles of 30 s ON and 30 s OFF pulses in 4°C bath. All buffers (LB1, LB2, and LB3) were complemented with EDTA free Protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 0.2 mM PMSF just before use. After sonication, Triton X‐100 was added to a final concentration of 1% followed by centrifugation at 20,000 g at 4°C for 10 min to remove particulate matter. After taking aside a 50 μl aliquot to analyze fragmentation, chromatin was aliquoted, snap‐frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use. Chromatin aliquots for fragmentation checks were mixed with an equal volume of 2× elution buffer (100 mM Tris–pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA, 2% SDS) and incubated at 65°C for 12 h for reverse‐crosslinking. An equal volume of TE buffer (10 mM Tris–pH 8 and 1 mM EDTA pH 8) was added to dilute the SDS to 0.5% followed by treatment with RNase A (0.2 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h and Proteinase K (0.2 μg/l) for 2 h at 55°C. DNA was isolated by phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol (25:24:1 pH 8) extraction followed by Qiaquick PCR Purification (QIAGEN, Germany). Purified DNA was then analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel and on Bioanalyzer (Agilent, USA) using a High Sensitivity DNA Assay.

Fifty million (Pol II‐HA) and 10 million cells (CTCF, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3) were used for each replicate of ChIP‐seq. Protein‐G coated Dynabeads (10 μl per million of cells) were incubated at 4°C in blocking solution (0.5% BSA in PBS) with (HA)‐tag (ab9110, Abcam), H3K4me3 (ab8580, Abcam), H3K4me1 (ab8895, Abcam), or CTCF (C15410210, Diagenode) specific antibodies. Chromatin was precleared by the addition of 10 μl protein‐G coated dynabeads per million cells and incubated at 4°C on a rotating wheel. A 50 μl aliquot of precleared chromatin was taken as input, mixed with an equal volume of 2× elution buffer, and treated as described above for chromatin fragmentation check. Precleared chromatin was then added to precoated beads coupled with the antibody of interest, and the mix was incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotating wheel. After incubation with chromatin, beads were washed four times with Wash buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 500 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8, 1% NP‐40, 0.7% Na‐Deoxycholate, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail) followed by one wash with TE‐NaCl buffer (10 mM Tris–pH 8, 1 mM EDTA pH 8, 50 mM NaCl) and a final wash with TE buffer (10 mM Tris–pH 8 and 1 mM EDTA pH 8). Immunoprecipitated chromatin was eluted by two sequential incubations with 50 μl Elution buffer (50 mM Tris–pH 8, 10 mM EDTA pH 8, 1% SDS) at 65°C for 15 min. The two eluates were pooled and incubated at 65°C for 12 h to reverse‐crosslink the chromatin followed by treatment with RNase A, Proteinase K and purification of DNA. Both input and ChIP samples were quantified using dsDNA Qubit assay (Thermofisher, USA). For Pol‐HA ChIP, a qPCR was performed to confirm the relative enrichment of GAPDH and ACTB target promoters as compared to a negative control sequence (GAPDH promoter forward primer: 5′‐CTAGCCTCCCGGGTTTCTCT‐3′, GAPDH promoter reverse primer: 5′‐ACAGTCAGCCGCATCTTCTT‐3′, ACTB promoter forward primer: 5′‐CAAAGGCGAGGCTCTGTG‐3′, ACTB reverse primer: 5′‐CCGTTCCGAAAGTTGCCTT‐3′, Negative control forward primer: 5′‐TAAACCAGGGCTGCTGTTCT‐3′ and Negative control reverse primer: 5′‐TGACCGCAAAGCTGTTACAC‐3′).

Then, 10 ng of DNA was used to prepare sequencing libraries with Illumina ChIP Sample Library Prep Kit (Illumina, USA). Barcoded libraries were then sequenced on Illumina HiSeq2000 or Illumina HiSeq4000 in paired‐end runs.

HiC

HiC experiments were performed as in Belton et al (2012) with little changes. Briefly, 10 million cells were fixed at 2% formaldehyde. The reaction was stopped by adding glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM and cells were lysed with 0.2% IGEPAL‐CA630. Either flash‐frozen or processed nuclei were solubilized with 0.8% SDS for 1 h at 37°C. SDS was neutralized with Triton X‐100, and chromatin was digested overnight at 37°C, 800 rpm with 2,000 U of HindIII enzyme. The following day, nuclei were washed twice with NEBuffer 2 (New England Biolabs, USA) and incubated in biotin fill‐in mixture containing biotin‐14‐dCTP and DNA Polymerase I Klenow fragments for 90 min at 37°C. Biotin‐removal step with the T4 DNA polymerase was omitted and nuclei were washed again twice with T4 ligase buffer (New England Biolabs, USA) and incubated for 24 h at 16°C with 2,000 U of high‐concentrated T4 DNA ligase. DNA was then recovered in low TE buffer after an overnight Proteinase K treatment and phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol (25:24:1 pH 8) extraction. The quantity of material was assessed using Qubit dsDNA BR kit (Thermofisher, USA), and digestion‐religation events were checked on 1% agarose gel. If religation has occurred, 10 μg of DNA for each condition was sonicated by batches of 5 using Covaris E220 with the intensifier. The size distribution was then assessed on BioAnalyzer (Agilent, USA) using DNA 1000 assay. Biotinylated ligation junctions were pulled down using 150 μl Streptavidin MyOne T1 beads per 2.5 μg of DNA in 1X B&W buffer (5 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 500 μM EDTA, 1 M NaCl) and 1‐h incubation on a rotating wheel at RT. HiC libraries were finally prepared after wash‐offs, end‐repair, A‐tailing, and classical Illumina adapter ligation and amplification. The sequencing was performed on a HiSeq2000 in paired‐end runs.

Bioinformatic procedures

RNA‐seq data processing

Raw sequencing reads were aligned to human genome (hg19) using TopHat2 (Kim et al, 2013).Thanks to strand‐specific library prep of RNA samples, the strand from which the RNA was originally transcribed can be inferred. Hence, the reads that align to Watson and Crick strands were separated and processed separately using PASHA pipeline (Fenouil et al, 2016) to generate strand‐specific wig files representing an average enrichment score every 50 bp. All wig files were then rescaled to normalize the enrichment scores to the depth of sequencing. Rescaled wig files from biological replicate experiments were then used to generate a wig file that represents the average strand‐specific RNA signal from several biological replicates.

Gene expression analysis

Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis was performed by using the DESeq package (Anders & Huber, 2010) from Bioconductor. First, HTseq‐count program from the HTSeq framework (Anders et al, 2015) was used to count the sequenced reads mapping to hg19 Refseq gene annotations and then these counts were processed using the DESeq package to identify genes that are significantly differentially expressed relative to the reference sample.

Ratios of introns over exons

The HTSeq framework was used to count the reads that map on introns of protein‐coding genes in one hand and exons in the other. Then, a normalized merged table was created containing only genes that have both intron and exon sequences using the DESeq package. To filter out genes with a certain threshold of expression, Cufflinks package (Trapnell et al, 2012) was used to count the RPKM (Reads per kilobases per million mapped reads) on protein‐coding genes from hg19 RefSeq annotations.

ChIP‐seq data processing

Raw sequencing reads were aligned to human genome (hg19) using Bowtie2 (Langmead & Salzberg, 2012). Aligned reads were elongated in silico using the DNA fragment size inferred from paired reads or an estimated optimal fragment size for orphan reads using PASHA R pipeline (Fenouil et al, 2016). Wig files representing the average enrichment score every 50 bp were generated. All wig files were then rescaled to normalize the enrichment scores to the depth of sequencing. All Figures showing Pol‐HA ChIP‐seq were displayed for one representative replicate.

Peak calling

Wig files were used to detect the genomic regions with enrichment signals beyond the background signal. For this purpose, Thresholding function of the Integrated Genome Browser (IGB) was used to determine the enrichment score above which a genomic region was considered as enriched. This function allows the level definition of background noise as well as the minimum number of consecutive bins to be considered as enriched region and finally the minimum gap beyond which two enriched regions were considered to be distinct. These parameters were then fed to an in‐house script that performs peak calling by using an algorithm employed by Thresholding function of IGB.

Average metagene profiles

To generate Pol II, H3K4me3, H3K4me1, and RNA‐seq average signal profiles, hg19 Refseq genes annotations were used to extract values from wig files. Bin scores inside these annotations and in a defined region before the TSS and after the annotated termination site. Removal of the annotations too close to each other is necessary to avoid mixing signals from close‐by annotations, which can cause misinterpretation of the results. Strand‐specific RNA‐seq values from wig files were retrieved with in‐house R and Perl scripts for selected genes. An algorithm described previously (Koch et al, 2011) was used to rescale the genes to the same length by interpolating the values on 1,000 points and build a matrix on which each column is averaged, and resulting values are used to plot average metagene profiles. All P‐values comparing read‐through signal in sense (after TES) and antisense (before TSS) in rWT and CTD mutants were calculated using two‐sided Wilcoxon tests from R software. For CTCF average signal profiles, peaks were called in rWT ChIP‐seq datasets as described above in Peak Calling section. Identified peaks were used to generate annotations files. Values from wig files were then extracted based on selected regions. Bin scores inside these annotations and in a region of 5 kb around were determined.

RNA read‐through index

Upstream and downstream read‐through transcription indexes were calculated by dividing the average sense (for downstream RT) and antisense (for upstream RT) signal in 20 kb region upstream or downstream of the gene by the average signal in the first half of the corresponding gene body. Asinh transformation was applied to the values for graphical representation. P‐values were then calculated with a two‐sided Wilcoxon test from R software.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests performed in the study are Wilcoxon tests due to the absence of normal data distribution.

HiC data processing

Raw sequencing reads were cleaned using by default parameters of HiCUP pipeline (Wingett et al, 2015). Briefly, human genome (hg19) was digested in situ with HindIII enzyme to create a digested reference genome. Sequencing reads were cut at putative HiC ligation junctions and aligned independently on the digested reference genome. All artifacts, such as religation events or PCR duplicates, were removed during the process. Then, HOMER software (http://homer.ucsd.edu) was used to generate PCA analysis reflecting chromatin compartmentation and juicer tools to create hic files viewable with Juicebox software. TADs annotations were extracted from human B cells (GM12878 from (Rao et al, 2014), GSE63525).

Author contributions

Yousra Yahia: Data curation; formal analysis; validation; investigation; visualization; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Alexia Pigeot: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; visualization; methodology; project administration; writing – review and editing. Amal Zine El Aabidine: Data curation; software; formal analysis; visualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Nilay Shah: Data curation; investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Nezih Karasu: Data curation; formal analysis; methodology; writing – review and editing. Ignasi Forné: Data curation; formal analysis; writing – review and editing. Stefan Krebs: Data curation; formal analysis; writing – review and editing. Helmut Blum: Resources; data curation; formal analysis; writing – review and editing. Cyril Esnault: Data curation; formal analysis; writing – review and editing. Tom Sexton: Data curation; formal analysis. Axel Imhof: Data curation; formal analysis; writing – review and editing. Dirk Eick: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; supervision; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Jean‐Christophe Andrau: Conceptualization; resources; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; visualization; methodology; writing – original draft; project administration; writing – review and editing.

Disclosure and competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Dataset EV1

Dataset EV2

Dataset EV3

Dataset EV4

Source Data for Expanded View

PDF+

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Acknowledgements

In the J‐CA lab, this work was supported by institutional grants from the CNRS and by specific grants from the “Agence Nationale de la Recherche”(ANR). In both the J‐CA and DE labs, the work was also supported by a German‐French BMBF‐ANR grant “EpiGlyco.” NK was supported by an INCA grant “G4access” and AP by an ANR “MECEPI.”

EMBO reports (2023) 24: e56150

Contributor Information

Dirk Eick, Email: eick@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Jean‐Christophe Andrau, Email: jean-christophe.andrau@igmm.cnrs.fr.

Data availability

The sequencing data presented in this manuscript are available on GEO database under GSE210601. For all data processed in this article, the number of reads aligned to the human hg19 genome is displayed in Dataset EV4.

References

- Anders S, Huber W (2010) Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11: R106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W (2015) HTSeq—a python framework to work with high‐throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31: 166–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillat D, Hakimi MA, Naar AM, Shilatifard A, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R (2005) Integrator, a multiprotein mediator of small nuclear RNA processing, associates with the C‐terminal repeat of RNA polymerase II. Cell 123: 265–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belton JM, McCord RP, Gibcus JH, Naumova N, Zhan Y, Dekker J (2012) Hi‐C: a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods 58: 268–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernecky C, Herzog F, Baumeister W, Plitzko JM, Cramer P (2016) Structure of transcribing mammalian RNA polymerase II. Nature 529: 551–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratowski S (2009) Progression through the RNA polymerase II CTD cycle. Mol Cell 36: 541–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratowski S, Sharp PA (1990) Transcription initiation complexes and upstream activation with RNA polymerase II lacking the C‐terminal domain of the largest subunit. Mol Cell Biol 10: 5562–5564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RD, Palancade B, Lang A, Bensaude O, Eick D (2004) The last CTD repeat of the mammalian RNA polymerase II large subunit is important for its stability. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 35–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RD, Conrad M, Eick D (2005) Role of the mammalian RNA polymerase II C‐terminal domain (CTD) nonconsensus repeats in CTD stability and cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol 25: 7665–7674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P, Armache KJ, Baumli S, Benkert S, Brueckner F, Buchen C, Damsma GE, Dengl S, Geiger SR, Jasiak AJ et al (2008) Structure of eukaryotic RNA polymerases. Annu Rev Biophys 37: 337–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasilva LF, Blumenthal E, Beckedorff F, Cingaram PR, Gomes Dos Santos H, Edupuganti RR, Zhang A, Dokaneheifard S, Aoi Y, Yue J et al (2021) Integrator enforces the fidelity of transcriptional termination at protein‐coding genes. Sci Adv 7: eabe3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descostes N, Heidemann M, Spinelli L, Schuller R, Maqbool MA, Fenouil R, Koch F, Innocenti C, Gut M, Gut I et al (2014) Tyrosine phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II CTD is associated with antisense promoter transcription and active enhancers in mammalian cells. Elife 3: e02105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egloff S, O'Reilly D, Chapman RD, Taylor A, Tanzhaus K, Pitts L, Eick D, Murphy S (2007) Serine‐7 of the RNA polymerase II CTD is specifically required for snRNA gene expression. Science 318: 1777–1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eick D, Geyer M (2013) The RNA polymerase II carboxy‐terminal domain (CTD) code. Chem Rev 113: 8456–8490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod ND, Henriques T, Huang KL, Tatomer DC, Wilusz JE, Wagner EJ, Adelman K (2019) The integrator complex attenuates promoter‐proximal transcription at protein‐coding genes. Mol Cell 76: e737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenouil R, Cauchy P, Koch F, Descostes N, Cabeza JZ, Innocenti C, Ferrier P, Spicuglia S, Gut M, Gut I et al (2012) CpG islands and GC content dictate nucleosome depletion in a transcription‐independent manner at mammalian promoters. Genome Res 22: 2399–2408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenouil R, Descostes N, Spinelli L, Koch F, Maqbool MA, Benoukraf T, Cauchy P, Innocenti C, Ferrier P, Andrau JC (2016) Pasha: a versatile R package for piling chromatin HTS data. Bioinformatics 32: 2528–2530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A, Roeder RG (2020) The CTD is not essential for the post‐initiation control of RNA polymerase II activity. J Mol Biol 432: 5489–5498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber HP, Hagmann M, Seipel K, Georgiev O, West MA, Litingtung Y, Schaffner W, Corden JL (1995) RNA polymerase II C‐terminal domain required for enhancer‐driven transcription. Nature 374: 660–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Texari L, Hayes MGB, Urbanowski M, Chang MW, Givarkes N, Rialdi A, White KM, Albrecht RA, Pache L et al (2018) Transcription elongation can affect genome 3D structure. Cell 174: e1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsin JP, Li W, Hoque M, Tian B, Manley JL (2014) RNAP II CTD tyrosine 1 performs diverse functions in vertebrate cells. Elife 3: e02112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Gong Z, Ghosal G, Chen J (2009) SOSS complexes participate in the maintenance of genomic stability. Mol Cell 35: 384–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama Y, Rappsilber J, Mann M (2006) Modular stop and go extraction tips with stacked disks for parallel and multidimensional peptide fractionation in proteomics. J Proteome Res 5: 988–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger MG, Schwalb B, Mackowiak SD, Velychko T, Hanzl A, Imrichova H, Brand M, Agerer B, Chorn S, Nabet B et al (2020) Selective mediator dependence of cell‐type‐specifying transcription. Nat Genet 52: 719–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL (2013) TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14: R36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch F, Fenouil R, Gut M, Cauchy P, Albert TK, Zacarias‐Cabeza J, Spicuglia S, de la Chapelle AL, Heidemann M, Hintermair C et al (2011) Transcription initiation platforms and GTF recruitment at tissue‐specific enhancers and promoters. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 956–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2012) Fast gapped‐read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9: 357–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laybourn PJ, Dahmus ME (1989) Transcription‐dependent structural changes in the C‐terminal domain of mammalian RNA polymerase subunit IIa/o. J Biol Chem 264: 6693–6698 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lux C, Albiez H, Chapman RD, Heidinger M, Meininghaus M, Brack‐Werner R, Lang A, Ziegler M, Cremer T, Eick D (2005) Transition from initiation to promoter proximal pausing requires the CTD of RNA polymerase II. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 5139–5144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykke‐Andersen S, Žumer K, Molska E, Rouvière JO, Wu G, Demel C, Schwalb B, Schmid M, Cramer P, Jensen TH (2021) Integrator is a genome‐wide attenuator of non‐productive transcription. Mol Cell 81: 514–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A, Heidemann M, Lidschreiber M, Schreieck A, Sun M, Hintermair C, Kremmer E, Eick D, Cramer P (2012) CTD tyrosine phosphorylation impairs termination factor recruitment to RNA polymerase II. Science 336: 1723–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meininghaus M, Eick D (1999) Requirement of the carboxy‐terminal domain of RNA polymerase II for the transcriptional activation of chromosomal c‐fos and hsp70A genes. FEBS Lett 446: 173–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meininghaus M, Chapman RD, Horndasch M, Eick D (2000) Conditional expression of RNA polymerase II in mammalian cells. Deletion of the carboxyl‐terminal domain of the large subunit affects early steps in transcription. J Biol Chem 275: 24375–24382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair D, Kim Y, Myers LC (2005) Mediator and TFIIH govern carboxyl‐terminal domain‐dependent transcription in yeast extracts. J Biol Chem 280: 33739–33748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]