Abstract

Justice-involved veterans are a high-risk, high-need subgroup serviced by behavioral health services within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system. Justice-involved veterans often have complex mental health and substance use difficulties, a myriad of case management needs, and a range of criminogenic needs that are difficult to treat with traditional outpatient VHA services. The current study represents an initial evaluation of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Justice-Involved Veterans (DBT-J), a novel psychotherapy program providing 16 weeks of skills-based group therapy and individualized case management services to veterans with current or recent involvement with the criminal justice system. A total of 13 veterans were successfully enrolled into this initial acceptability and feasibility trial. Results broadly suggested DBT-J to be characterized by high ease of implementation, successful recruitment efforts, strong participant attendance and retention, high treatment fidelity, and high acceptability by veteran participants, DBT-J providers, and adjunctive care providers alike. Although continued research using comparison conditions is necessary, Veterans who completed participation in DBT-J tended to show reductions in criminogenic risk across the course of treatment. Cumulatively, these findings suggest DBT-J holds potential as a VHA-based intervention to address the various needs of justice-involved veterans.

Keywords: Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Veteran, Criminal Justice, Risk-Need-Responsivity Model, Case Management

Justice-involved veterans are a high-risk, high-need population within the United States and particularly within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) behavioral health services system. Although veterans account for only 7.6% of currently incarcerated persons in the United States (commensurate with their representation in the general population; Maruschak et al., 2021), one estimate using a national sample of veterans suggest approximately 70% of veterans receiving VHA care for substance use have a history of arrest, including 58% with a history of three or more arrests and 24% with a history of arrest for violent crimes (Weaver et al., 2013). Similarly, a study of nearly 13,000 veterans in Florida suggested those receiving VA services for both mental health and substance use were 10.2 times more likely to have a history of multiple arrests compared to the general population (Pandiani et al., 2003).

The needs of justice-involved veterans are markedly complex. Estimates using national data suggest 77% and 71% justice-involved veterans serviced by VHA are diagnosed with mental health and substance use disorders, respectively, the most common of which include mood, posttraumatic, personality, and alcohol use disorders (Finlay et al., 2015). In comparison to persons without justice involvement, justice-involved veterans are also more likely to engage in suicide behaviors, to have difficulties with aggression and violence, and to experience homelessness, occupational instability, and low community integration (Edwards et al., 2020a; Edwards et al., 2022a; Edwards et al., 2022b; LePage et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2021).

Currently, VHA relies on two programs to service justice-involved veterans, Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) and the Health Care for Reentry Veterans (HCRV) program. Both programs function to connect eligible veterans with VA behavioral health services. However, they are reliant upon existing behavioral health programming within the VA and typically do not refer veterans to specialized, forensic-oriented programming. Although VJO and HCRV are generally effective in connecting veterans to VHA services (Finlay et al., 2016; Finlay et al., 2017), behavioral health services – when provided in isolation – are typically insufficient in reducing criminal behavior and addressing the range of needs experienced by justice-involved veterans (Epperson et al., 2014; Timko et al., 2014). Effectively addressing the complex needs of this population may require connection of veterans to either (a) a combination of behavioral health, case management, and forensic-oriented services or (b) integrative programming to address these needs concurrently.

To date, VHA has relied on a combination-of-services approach and, as a result, routinely offers well-established behavioral health and case management services to justice-involved veterans (Finlay et al., 2016; Finlay et al., 2017). However, a recent survey of VJO and HCRV specialists suggests numerous barriers to implementing forensic-oriented services within the VHA system (Blonigen et al., 2018). At the patient level, forensic programming traditionally developed for civilians (e.g., Moral Reconation Therapy [MRT], Thinking for a Change [T4C], etc.) are seen as lengthy (often 20+ weeks), intensive, and unappealing to the internal motivations of justiceinvolved veterans. At the organizational level, many VHA behavioral health providers are similarly resistant to forensic-oriented programming due to biases against veterans with “antisocial personalities” and perceptions of forensic-oriented programming as largely irrelevant to behavioral health (Blonigen et al., 2018). Effectively establishing programming for justice-involved veterans within VHA behavioral health settings will therefore require the program to be of brief duration (<20 weeks), appealing to the internal motivations of justice-involved veterans (e.g., by addressing interpersonal and case management concerns in addition to criminogenic risk factors), and relevant to VHA behavioral health providers (e.g., by balancing a behavioral health focus with interventions to reduce criminogenic risk).

Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Justice-Involved Veterans

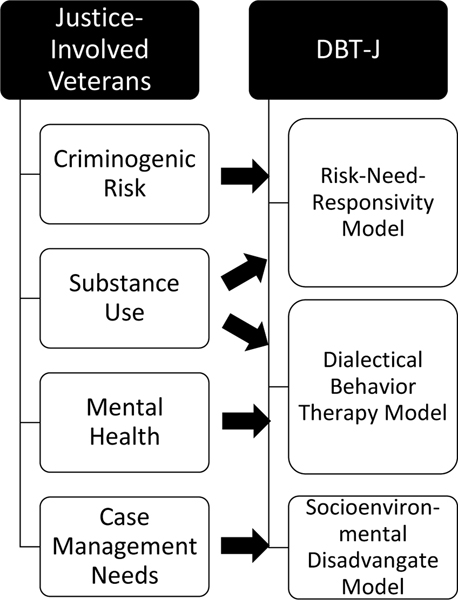

In light of these barriers to a combination-of-services approach, Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Justice-Involved Veterans (DBT-J) combines elements of three prominent theoretical models – the Risk-Need-Responsivity model of offender rehabilitation (RNR), Dialectical Behavior Therapy for behavioral health (DBT), and Socioenvironmental Disadvantage Model (SDM) – into an integrative program for addressing the behavioral health, case management, and criminogenic needs of justice-involved veterans concurrently. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Correspondence between Needs of Justice-Involved Veterans and DBT-J Theoretical Foundations

RNR is the most widely validated and empirically successful treatment paradigm for reducing criminal behavior (Andrews et al., 2011; Polaschek, 2012). It is guided by three primary principles: (1) Intensity of services should be directly proportionate to risk of recidivism and focused on persons at highest risk for criminal behavior; (2) Treatment should be tailored to address relevant, empirically-identified, criminogenic risk factors (i.e., antisocial behavior, antisocial personality, antisocial thinking, antisocial peers, disruptions in educational/vocational functioning, disruptions in family relationships, substance use, and lack of prosocial activity); and (3) Treatment should utilize a cognitive-behavioral approach and accommodate “”responsivity” factors that may impede learning and/or behavioral change, such as comorbid psychopathology, interpersonal style, and learning style. Though originally developed and validated for civilian populations, RNR is also effective in reducing criminal behavior of veterans (Timko et al., 2014). Nevertheless, traditional RNR-based programs (e.g., MRT, T4C, etc.) are not structured to address the behavioral health or case management needs of justice-involved veterans (Timko et al., 2014; Blonigen et al., 2018) and, as noted previously, encounter various implementation barriers within VHA (Blonigen et al., 2018).

DBT is a well-established, transdiagnostic psychotherapy for reducing high-risk, self-destructive, and quality-of-life interfering behaviors. Originally developed to treat suicidal behavior (Linehan, 1993), adaptations of DBT have been effectively used to treat various behavioral health concerns commonly associated with veteran justice-involvement, including complex psychological comorbidities, aggression, substance use, antisocial personality traits, and premature treatment dropout (Bornovalova & Daughters, 2007; Dimeff & Koerner, 2007; Galietta & Rosenfeld, 2012). Research also suggests DBT adaptations can be effectively used in the treatment of both forensic (Tomlinson, 2018) and veteran populations (Goodman, et al., 2016; Landes et al., 2017). DBT is commonly used in VHA behavioral health settings (Landes et al., 2017); however, to date, it has not been adapted for the treatment of justice-involved veterans.

Lastly, while not directly related to criminal behavior (Andrews et al., 2011), SDM suggests socioenvironmental disadvantages – such as housing instability, poverty, and unemployment – may contribute to development of criminogenic risk factors by increasing exposure to crime and opportunities for criminal activity and/or exacerbate behavioral health concerns by increasing stress (Epperson et al., 2014). Such factors are commonly considered responsivity factors within the RNR framework (Andrews et al., 2011). As such, while not a traditional target of forensic-oriented programming, addressing such factors is generally considered necessary to ensure the success of forensic programming (Andrews et al., 2011). Case management services to mitigate socioenvironmental disadvantage are therefore key to managing both criminogenic and behavioral health needs of justice-involved veterans.

DBT-J Intervention Model

DBT-J combines elements of RNR, DBT, and SDM to address mental health, substance use, criminogenic, and case management needs through a single, integrated, manualized program.

It provides veterans 1–1.5 hours of intervention per week for 16 weeks through three core components. The first component, group therapy, forms the foundation of DBT-J and focuses on developing concrete skills for managing mental health, substance use, and criminogenic needs. Included skills were drawn from RNR- and DBT-based interventions to align with common needs of justice-involved veterans (see Table 1). For example, consistent with RNR-based approaches, there is a strong cognitive-behavioral emphasis on recognizing and challenging criminogenic thinking patterns and increasing prosocial behaviors through goal-directedness, problem-solving, and interpersonal skills (Andrews et al., 2011). Also, consistent with DBT-based interventions, there is a strong emphasis on mindfulness and emotion regulation as transdiagnostic interventions for emotional distress and behavior regulation (Linehan, 1993). Group sessions occur once per week for 60 minutes. They are structured and closed format, allowing therapeutic content to build cumulatively across the course of treatment. Like RNR- and DBT-based interventions, each session includes (a) completion of a brief mindfulness exercise, (b) review of homework from the previous week, (c) introduction and in-session practice of a new skill, and (d) assigning of between-session homework. Homework is designed to promote generalization of skills to real-life experiences and considered a necessary component of the intervention (Edwards et al., 2021). To aid in guiding session content, all veterans are provided interactive handouts and worksheets corresponding to each introduced skill. These handouts and worksheets serve to further veterans’ learning, guide homework assignment completion, and provide a resource to review missed material due to program absence.

Table 1:

Justice-Involved Veteran Needs & Corresponding Interventions

| Veteran Need | Corresponding Group Skills / Intervention | Example Referrals for Higher-Risk Offenders |

|---|---|---|

| Criminogenic Needs | ||

| Antisocial Behavior History | N/A | N/A |

| Antisocial Personality | Observing Limits Goal Directedness Skills Mindfulness of Others |

N/A |

| Antisocial Attitudes | Thinking Errors | N/A |

| Antisocial Peers | Building Prosocial Relationships | Peer Mentoring Community Veteran Organizations |

| Substance Use | Mindfulness of Goals Distress Tolerance | Local 12-step Programs Substance Use Counseling |

| Educational/Vocational Difficulties | Values Clarification Mindfulness of Goals | Job-Search Resources Tutoring Services VHA Veteran Readiness & Employment |

| Family Difficulties | Interpersonal skills | Family Therapy Family Support Services |

| Lack of Prosocial Activities | Values Clarification Mindfulness of Goals | Community Veteran Organizations |

| Behavioral Health Needs | ||

| Mood Disruption (e.g., depression, anxiety, etc.) | Mindfulness Skills Emotion Regulation Skills | Individual Psychotherapy |

| Emotion Dysregulation | Emotion Regulation Skills Goal Directedness Skills | |

| Interpersonal Difficulty | Interpersonal Skills | |

| Executive functioning Disruption | Mindfulness Skills Goal Directedness Skills | |

| Case Management Needs | ||

| Legal Difficulties | Mindfulness of Goals Problem Solving | Veteran Justice Outreach Specialist Veteran Medical-Legal Partnerships |

| Access to Benefits | Disabled American Veterans Charity VA Benefits Representative | |

| Financial Difficulty | Disabled American Veterans Charity VA Benefits Representative | |

| Housing | HUD-VA Supportive Housing Program Local Shelter System | |

| Food Insecurity | Local Food Pantry | |

Second, case management meetings, held every other week for approximately 30 minutes, provide veterans individual support in coordinating services between the treatment team, legal services, and connection with social services in the community (e.g., outside referrals, housing assistance, food stamps, etc.). Where possible, case-management sessions include coaching clients through application of skills learned in group therapy sessions (e.g., problem solving) to resolve case-management difficulties. In accordance with the RNR model (Andrews et al., 2011), degree of case management services aligns with the risk-level of the offender.

Last, consultation team is attended by DBT-J providers to provide a forum for discussing cases, troubleshooting barriers to therapeutic progress, and providing peer-support and peer-supervision. These weekly meetings last approximately 60 minutes. Similar to traditional DBT consultation team meetings, they are also designed to protect against provider burnout and promote continued adherence to the principles of DBT-J treatment (Walsh et al., 2018).

The structure of DBT-J was designed with consideration of common barriers to implementing forensic-oriented programming within VHA settings. Specifically, the brief duration (16 weeks) and balanced focus on both criminogenic and non-criminogenic needs were expected to be appealing to justice-involved veterans, whereas the similarity to traditional DBT skills groups, deemphasis of the presence or absence of a personality disorder, and partial focus on behavioral health were expected to be appealing to VHA behavioral health providers. This structure is also consistent with recent research suggesting DBT-based treatments that are abbreviated and/or comprising only group therapy, case management, and consultation team typically yield promising outcomes comparable to the 12-month, comprehensive DBT-model (McMain et al., 2018), even in the treatment of justice-involved persons (Moore et al., 2018). Further, the combination of group therapy and case management allowed the intervention to be both standardized across the course of treatment and individualized to the unique needs of each veteran. For a comparison of DBT-J, RNR, and DBT, see Table 2.

Table 2:

Comparison of DBT-J, DBT, RNR, & SDM

| Treatment Targets | Treatment Components | Treatment Duration | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | Substance Use | Criminogenic Needs | Case Management | Individual Therapy | Skills-Focused Group Therapy | Between-Session Telehealth | Case Management | Consultation Team | ||

| DBT-J | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 1–1.5 hours/week for 16 weeks | ||

| RNR | X | X | X | X* | 1 hour/week for 16–36 weeks | |||||

| DBT | X | X* | X* | X | X | X | X* | X | 2.5–3.5 hours/week for 52 weeks | |

| SDM | X | X | Varies | |||||||

occasionally included within treatment model

The therapeutic style adopted in DBT-J also integrates various strategies to counteract common difficulties with engaging veteran and justice-involved populations (Galietta & Rosenfed, 2012; Nugent et al., 2021). Consistent with a DBT-based approach (Linehan, 1993), all DBT-J providers prioritize developing a strong therapeutic alliance, building phenomenologically empathic conceptualizations of client behaviors and difficulties, and adopting a clinical style that balances nonjudgment, validation, empathy, collaboration, transparency, respect, direction, and accountability. Also consistent with DBT, the provider’s role also gradually transitions from that of “coach” to “cheerleader” across the course of treatment by emphasizing explicit direction (e.g., on matters of problem solving, skill acquisition and implementation, etc.) early in treatment and gradually shifting emphasis to support as the veteran progresses through treatment (Linehan, 1993). This aims to maximize veteran independence in problem-solving upon completion of the program, thereby maximizing chances for success after discharge.

The Current Study

Despite the overrepresentation of justice-involved veterans within VHA behavioral health services, there is a need for more established VHA services capable of addressing the complex needs of this population. The current study evaluated a novel, psychotherapeutic intervention, DBT-J, which combines elements of established treatment approaches into an integrated treatment framework. The primary aims of the intervention were to reduce veterans’ risk of future criminal behavior and improve psychological functioning. Because development of DBT-J is still in its infancy, the current study used an open label trial of 15 veterans with ongoing or recent justiceinvolvement to examine feasibility and acceptability of this intervention.

Method

Three cohorts of Veterans were enrolled into an open label acceptability and feasibility trial of DBT-J. The intervention protocol was manualized, developed with input and feedback from experts in the fields of Dialectical Behavior Therapy, psychotherapy with veterans, and psychotherapy with justice-involved persons. All providers were specifically trained in DBT-J and underlying theories; providers co-led therapy groups and divided cases for provision of case management. DBT-J was intended to be adjunctive to services provided through VJO and other ongoing behavioral health and/or social services. Therefore, information about treatment progress was shared with veterans’ VHA treatment teams (if applicable), and all participating veterans continued with their outside providers as needed.

Study Site & Recruitment

The trial was completed from January to October, 2021 with VHA-serviced veterans at James J. Peters Veterans Affairs medical center (VAMC), a large, VAMC located in a predominantly lower-income, urban neighborhood in Bronx, New York., a large, VA medical center (VAMC) located in a predominantly lower-income, urban neighborhood in James J. Peters Veterans Affairs medical center (VAMC), a large, VAMC located in a predominantly lower-income, urban neighborhood in Bronx, New York. The VAMC had an active VJO program to connect justice-involved veterans with internal behavioral health and substance use services. The VJO and outpatient behavioral health and substance use providers were informed about the program and encouraged to refer potentially eligible veterans for participation. After referral, veterans completed a brief information session via phone or video conference to receive further information about the study and to assess eligibility. Veterans meeting eligibility requirements and expressing interest in participation were then invited to provide their informed consent for participation. To protect participant safety during the COVID19 pandemic, all participation – including participation in treatment and completion of study assessments – was completed using VAWebEx, an online, secure, telehealth delivery platform.

Participants

A total of 15 veterans were recruited for participation in the current trial. Inclusion criteria included: (1) Veteran aged 18–65; (2) Ability to provide consent; (3) Current or recent history of justice-involvement, defined as (a) one or more arrests within two years prior to participation and/or (b) current supervision by parole or probation at the time of participation. Exclusion criteria included (1) Limited English proficiency; (2) Inability to tolerate group therapy format; (3) current high risk for suicide (defined as a score of >24 on Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation; CochraneBrink et al., 2000); and/or (4) current charges for a violent felony. To maximize applicability to real-world contexts, there were no diagnostic exclusion criteria for participation.

DBT-J Training & Fidelity

All interventions were delivered by the DBT-J treatment developer and postdoctoral, doctoral, and masters level training clinicians. All training clinicians completed a 10-hour training in DBT-J (e.g., structure, approach to case conceptualization, clinical style), underlying theories (i.e., DBT, RNR, SDM), and intervention strategies (e.g., behavioral skills, case management, management of group dynamics) by the treatment developer prior to delivering the protocol. The treatment developer had comprehensive training and experience in DBT, including completion of the 10-day DBT Intensive Training™ (Navarro-Haro et al., 2018) and 7 years’ experience providing DBT in various treatment settings. The developer was also comprehensively trained and experienced in RNR- and SDM-based interventions with 8 years’ experience providing these interventions across treatment settings. Weekly supervision was also provided to providers by the treatment developer to provide additional training and feedback as needed to ensure continued adherence to the treatment protocol.

Group sessions were attended by an independent rater to assess fidelity to the DBT-J manual using an objective scale developed to assess core features of the structure, content, and treatment principles along with general clinical competence (e.g., rapport building, managing group dynamics, etc.). This scale scored fidelity according to a 5-point scale of 1 (completely nonadherent) to 5 (no violations to adherence). Raters attended sessions live instead of reviewing session recordings due to participants’ expressed anxieties related to recording sessions. The treatment developer and independent rater each coded the first five group sessions to establish inter-rater reliability; the rater then coded 20% of randomly selected group sessions thereafter. Notably, because the treatment developer was intimately involved in delivery of treatment sessions, establishing inter-rater reliability required the developer to code their own fidelity. Subsequent ratings were then completed by the independent rater, who was not involved in treatment delivery. Providers were required to maintain an average of 4 or above (some minor violations to adherence) to demonstrate adequate adherence to the intervention.

Assessment

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics were assessed during baseline assessments. Demographics were assessed via veterans’ electronic medical records and self-report. Baseline criminogenic risk and history of justice involvement were assessed using the Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI; Andrews et al., 2000), a semi-structured interview that assesses criminogenic needs, risk of criminal recidivism, and responsivity factors that may impact treatment (e.g., social, physical, and mental health). It has been widely validated across numerous samples, and previous research suggests the LS/CMI total score to be a good predictor of later criminal behavior (Giguère & Lussier, 2016). Scores are interpreted through comparison against normative data of over 150,000 North American offenders (Andrews et al., 2000). Lastly, diagnosis was assessed by a licensed psychologist using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5; First et al., 2016) and Structured interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, Cluster B section (SID-P-IV; Pfohl et al., 1997), semi-structured interviews for determining psychiatric diagnoses in accordance with DSM diagnostic criteria.

Feasibility & Acceptability

To examine feasibility, investigators tracked: (1) Ease of implementation by measuring the number of hours DBT-J providers spent in preparation, delivery of intervention, consultation team, and supervision; (2) Recruitment by measuring rates of successful referral to DBT-J (recruitment was considered adequate if at least 70% of eligible veterans referred to the study agreed to participate); (3) Attendance & Retention by tracking the number of sessions and specific sessions each veteran attended (retention was considered adequate if 70% of participants attended at least 10 of the 16 group sessions and inadequate otherwise); and (4) Treatment fidelity through use of the aforementioned fidelity scale.

To assess intervention acceptability, participants completed a brief survey after 2 months of being enrolled in the study and upon completion of the DBT-J intervention. Surveys included five Likert-format items, each scored on a 5-point scale, to assess participants’ perceptions of treatment helpfulness, degree to which they have benefited from treatment, motivation to continue in treatment, relevance of group session content, and helpfulness of case management sessions. Five open-ended response questions also provided participants opportunity to share what they liked/disliked about the treatment and features they found helpful/unhelpful.

Given previously noted barriers to implementing forensic-oriented programming in VHA settings, it was deemed necessary to also gather acceptability information from those delivering and referring to the DBT-J program. Intervention acceptability by providers was therefore also assessed using brief surveys, completed by DBT-J providers and adjunctive care providers upon completion of each treatment cycle. (Note, to limit biases associated with these surveys, the treatment developer did not complete an acceptability survey despite involvement as a DBT-J provider). Surveys included five, Likert-format items, each scored on a 5-point scale, to assess providers’ perceptions of treatment helpfulness, degree to which patient(s) benefit from treatment, relevance of treatment to veteran needs, ease or difficulty of treatment administration (DBT-J providers only), and interference of DBT-J on adjunctive care (adjunctive care providers only). Five open-ended response questions also provided DBT-J and adjunctive providers opportunity to share what they liked/disliked about the treatment and features they found helpful/unhelpful. These qualitative responses were then reviewed by the principal investigator using thematic analysis to identify common themes across participant feedback (Nowell et al., 2017).

Changes in Criminogenic Risk

Exploratory descriptive analyses were also used to preliminarily investigate changes in criminogenic risk across the course of treatment using the LS/CMI (Andrews et al., 2000). Structural and psychometric details about the LS/CMI are available above in Participant Characterization. Because the LS/CMI assesses both static and dynamic risk factors for criminal behavior, scores on this assessment can be expected to change across the course of treatment insomuch as the treatment influences dynamic risk factors.

Study Protocol

After providing informed consent, veterans were enrolled into the 16-week DBT-J program consisting of weekly skills-focused group psychotherapy and bi-weekly case management sessions. All group sessions were led by the DBT-J treatment developer and one or two training clinicians; case management sessions were divided evenly between all DBT-J providers. In total, DBT-J providers included a licensed psychologist (DBT-J treatment developer), a postdoctoral psychology fellow, and four masters-level counseling students. See Table 3 for a summary of this treatment protocol. Weekly consultation team meetings (incorporated into the structure of the DBT-J protocol) provided a forum for DBT-J providers to discuss ongoing cases, troubleshoot barriers to care, and review results of ongoing safety monitoring. In addition to this treatment, veterans completed assessments at four timepoints: baseline (prior to beginning treatment), mid-treatment (8 weeks after beginning DBT-J), post-treatment (after completing DBT-J), and follow-up (4 weeks after completing DBT-J).

Table 3:

DBT-J Treatment & Assessment Schedule

| Group Skills Module | Week | Skill(s) Introduced | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction | 1 | Observing Limits: How to respect the personal limits of self and others | Baseline Assessment |

|

| |||

| Mindfulness Skills | 2 | Mindfulness Introduction: Foundational skills for mindfulness practice | Case Management |

| 3 |

Wise Mind: Using mindfulness to make wise, effective decisions Dialectical Thinking: Increasing flexibility of thinking by recognizing and resolving dialectics |

||

|

| |||

| Emotion Regulation Skills |

4 | Mindfulness of Self: Understanding own emotional experiences by recognizing emotions, thoughts, bodily sensations, situational triggers, and vulnerabilities to emotion dysregulation | Case Management |

| 5 | Emotional Schemas: Recognizing and challenging unhelpful thoughts and beliefs about emotional experience; increasing self-acceptance during emotional distress | ||

| 6 | Thinking Errors: Recognizing and challenging common cognitive distortions associated with emotional distress and criminal behavior | Case Management | |

| 7 |

Check the Facts: Checking and challenging thinking according to the facts of a situation Opposite Action: Skills for decreasing the intensity of goal-inconsistent emotions |

||

| 8 | Self-Soothe: Regulating emotional intensity by regulating bodily sensations | Mid-Treatment Assessment; Case Management Acceptability Assessments |

|

|

| |||

| Goal Directedness Skills |

9 | Values Clarification: Recognizing pro-social values; creating values-consistent goals | |

| 10 | Mindfulness of Goals: Engaging in goals-consistent behavior and avoiding value-inconsistent behavior | Case Management | |

| 11 | Problem Solving: Identifying and overcoming common distressing situations | ||

| 12 | Distress Tolerance: Tolerating emotional distress without acting in value-inconsistent behavior; strategies for accepting emotionally difficult situations | Case Management | |

|

| |||

| Interpersonal Skills | 13 | Assertiveness: Recognizing assertiveness versus aggressiveness; strategies for pro-social assertiveness | |

| 14 | Mindfulness of Others: Increasing interpersonal closeness, validation of others | Case Management | |

| 15 | Making Prosocial Relationships: Identifying and building prosocial supports, managing self-disclosure | ||

|

| |||

| Termination | 16 | Relapse Prevention: Integrating previously learned skills into a relapse prevention plan | Post-Treatment Assessment Acceptability Assessments |

|

| |||

| Follow-up | 20 | N/A | Follow-up Assessment |

During baseline assessment, participants completed measures of participant characterization and criminogenic risk. At mid- and post-treatment, participants completed measures of criminogenic risk and feedback surveys. At follow-up, participants completed measures of criminogenic risk. Following completion of each assessment period, participants were compensated $75. Participants completing all four assessment periods also received a “completion bonus” of an additional $75, resulting in total compensation of $375. All study procedures were approved by the local VAMC IRB.

Results

Participant Characteristics

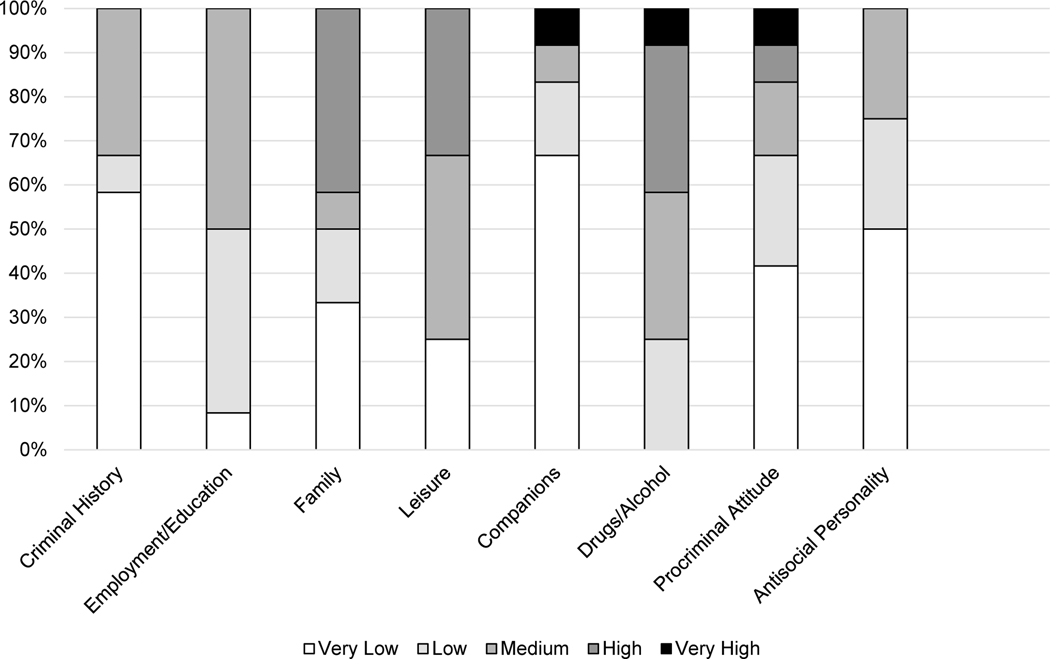

A total of 15 veterans agreed to participate in this initial clinical trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Justice-Involved Veterans (DBT-J). Of these, two Veterans dropped out prior to completing baseline assessments. The remaining 13 were included in statistical analyses. Participants were predominantly male, Black and/or Hispanic/Latino, heterosexual, relationally single, and with history of military service in the Army. Diagnostically, most common mental health conditions included posttraumatic stress, bipolar, and substance use disorders, whereas least common conditions included psychotic and cluster B personality disorders. Nearly 40% of veterans had a history of suicide attempt(s), including two veterans with ongoing suicidal ideation at the time of participation. See Table 4 for detailed participant characterization information. Most veterans were at moderate risk for future criminal behavior; in criminogenic risk assessments, difficulties with drugs and alcohol were most reported as risk factors, whereas lack of prosocial peers was least commonly reported. See Figure 2.

Table 4:

Participant Characterization

| n or M(SD) | % or range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 44.38 (11.52) | 26–65 |

| Gender Male |

13 | 100% |

| Female | 0 | 0% |

| Race White |

6 | 46.2% |

| Black | 7 | 53.8% |

| Other | 0 | 0% |

| Ethnicity Hispanic/Latino |

5 | 38.5% |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 8 | 61.5% |

| Sexual Orientation Straight/Heterosexual |

12 | 92.3% |

| Bisexual | 1 | 7.7% |

| Relationship Status Single |

6 | 46.2% |

| Committed Relationship | 4 | 30.8% |

| Married | 3 | 23.1% |

|

| ||

| Psychopathology Depressive Disorder |

3 | 23.1% |

| Bipolar Disorder | 5 | 38.5% |

| Psychotic Disorder | 1 | 7.7% |

| Anxiety Disorder | 3 | 23.1% |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 7 | 53.8% |

| Current Alcohol Use Disorder | 7 | 53.8% |

| Past Alcohol Use Disorder Only | 5 | 38.5% |

| Current Drug Use Disorder | 5 | 38.5% |

| Past Drug Use Disorder Only | 1 | 7.7% |

| Intermittent Explosive Disorder | 2 | 15.4% |

| Antisocial Personality Disorder | 1 | 7.7% |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 2 | 15.4% |

| Narcissistic Personality Disorder | 1 | 7.7% |

| Histrionic Personality Disorder | 0 | 0% |

| History of Suicide Attempt | 5 | 38.5% |

|

| ||

| Branch of Military Service | ||

| Army | 7 | 53.8% |

| Marines | 3 | 23.1% |

| Navy | 3 | 23.1% |

| Air Force | 0 | 0% |

| Coast Guard | 0 | 0% |

| Date of Military Discharge | 2001 (11.81 years) | 1979–2016 |

|

| ||

| Total Prior Arrests | 4.23 (2.74) | 2-12 |

| Nature of Most Recent Charge(s) Violent Offense(s) |

4 | 30.8% |

| Property Offense(s) | 4 | 30.8% |

| Drug Offense(s) | 4 | 30.8% |

| Technical Offense(s) | 2 | 15.4% |

| Enrolled in Veterans Treatment Court | 7 | 53.8% |

| Receiving Probation/Parole Supervision | 1 | 7.7% |

|

| ||

| Baseline Criminogenic Risk Very Low |

1 | 7.7% |

| Low | 2 | 15.4% |

| Moderate | 7 | 53.8% |

| High | 2 | 15.4% |

| Very High | 0 | 0% |

Figure 2:

Baseline Criminogenic Risk Factors

Feasibility

Overall, results suggested DBT-J to be a generally feasible intervention to deliver within VHA settings.

Ease of Implementation

Ease of implementation was relatively high, particularly for DBT-J providers with prior experience in DBT and/or work with forensic populations. On average, each provider devoted approximately 4.5–5.5 hours per week to tasks associated with providing DBT-J services to these veterans, including group therapy provision (1 hour per cohort weekly), case management (30 minutes per Veteran biweekly), documentation (30 minutes weekly), consultation team participation (1 hour weekly), supervision (0.5–1 hour weekly), assessment administration (2 hours per Veteran for baseline assessments; 30 minutes per Veteran for follow-up assessments), and participant recruitment and onboarding (1–1.5 hours per Veteran), with variation stemming from differences in providers’ case management caseloads. Notably, time devoted to program-related tasks decreased across the course of the trial as providers became more comfortable with the protocol and procedures (e.g., in documentation) were streamlined. Because all aspects of DBT-J were delivered online, a research assistant was required to attend all group therapy sessions to provide as needed technological support to veterans.

Recruitment

Some recruitment barriers were encountered, particularly early in the trial, such as outpatient providers being unaware of the legal status of their clients to make referrals and some providers viewing DBT-J as an unnecessary adjunctive treatment. Overcoming these barriers required DBT-J providers to build personal relationships with outpatient VA providers, provide education around the prevalence of veteran justice involvement in VHA behavioral health settings, and establish a firm partnership with the local Veterans Justice Outreach program. As the trial progressed and these efforts were implemented, referral rates progressively increased. A total of 18 eligible veterans were referred to the DBT-J clinical trial during the study period; of these, 15 (83%) provided informed consent, 2 (11%) were unresponsive to outreach attempts, and 1 (6%) stated that he was no longer interested in participating. After informed consent procedures, 2 veterans became unresponsive to outreach attempts prior to completing any study procedures. Thus, of the 18 eligible veterans referred to DBT-J, 13 (72%) successfully enrolled into the program.

Attendance & Retention

Three participants (23%) discontinued their participation in DBT-J prior to treatment completion; one discontinued due to scheduling conflicts associated with employment after attending 7 of the first 8 sessions. The other two became unresponsive to outreach attempts shortly after beginning the treatment; each completed 2 sessions. Among the 10 Veterans who completed the DBT-J trial, treatment engagement was generally strong. On average, these veterans attended approximately three-quarters of scheduled group sessions (M = 76.25%, SD = 13.76%); 5 veterans attended 9–11 sessions, 3 attended 12–14 sessions, and 2 attended 15–16 sessions. Similarly, veterans completed an average of 76% of assigned between-session homework assignments (SD = 19.41%), and 80% completed all assessment periods.

Integration of case management services and delivery of DBT-J using an online platform proved vital in maintaining participant engagement and retention. Because all DBT-J participation was completed online, participants were able to maintain engagement with the program even when admitted to residential substance use treatment programs (n=2) and shelter systems (n=2) during the study period. Upon referral to such programs, DBT-J case management services aided in veterans’ transitions into these outside programs and coordinated with outside providers to ensure continued treatment engagement.

Treatment Fidelity

The first five DBT-J group sessions were coded to establish inter-rater reliability of adherence coding between the adherence coder and the principal investigator (IRR=100%). Following establishment of inter-rater reliability, a random selection of 4–5 DBT-J group sessions were coded for each of the three cycles of DBT-J. Coding suggested generally excellent adherence to the DBT-J treatment manual (overall adherence: M = 4.78/5, SD = 0.65). Consistent with this, DBT-J providers reported minimal difficulty with delivering DBT-J adherently in feedback assessments (overall difficulty: 1.60/5).

Acceptability

Results suggested that DBT-J was also a generally acceptable intervention to veterans receiving the treatment, DBT-J providers, and adjunctive care providers.

Feedback from Participants

Overall, participants provided optimistic feedback regarding their participation in DBT-J. In their quantitative feedback, participants indicated generally positive impressions of the treatment and its helpfulness (out of 25, at mid-treatment, M = 22.14, SD = 3.67; at post-treatment, M = 22.14, SD = 3.76). Similarly, in their qualitative feedback, four general themes emerged. First, veterans expressed appreciation of the behavioral skills introduced through group therapy sessions. For example, one veteran stated, “I’ve been able to identify with what emotions I am dealing with without reacting so quickly.” Second, veterans noted the benefits of discussing their difficulties in a group setting (e.g., “Being able to talk openly about my mental health issues”). Third, veterans were appreciative of DBT-J providers, describing them as “insightful,” “understanding,” and “engaging.” Lastly, veterans reported feeling validated when connecting with others encountering similar legal difficulties.

Participants also provided recommendations on areas for improvement to DBT-J, though these recommendations were not consistent across participants. For example, whereas some veterans reported that excessive group participation detracted from session content, others expressed a desire for more group participation. Two veterans also recommended the program be extended to include more group sessions. See Supplement for a comprehensive list of these qualitative feedback responses.

Feedback from DBT-J Providers

Feedback from DBT-J providers similarly suggested high acceptability of the DBT-J intervention. In quantitative feedback, DBT-J providers rated the program as generally helpful (M = 4.80/5), beneficial to patients (M = 4.80/5), and designed to address issues relevant to clients’ needs (M = 4.60/5). In qualitative feedback, providers consistently identified the skills groups as the most helpful aspect of the DBT-J program and described these groups as “interactive,” and “[showing veterans] that they are not alone in their struggles.” They also expressed appreciation for structured time devoted to case management, noting that this aspect of the program allowed for individualized services and helped in managing burnout associated with treating a high-risk population. Some providers expressed concerns about the program being delivered via telehealth and offered various recommendations to improve coordination between providers, increase DBT-J provider competence around case management needs, and manage group dynamics. See Supplement for a comprehensive list of qualitative feedback responses.

Feedback from Adjunctive Care Providers

Similarly, feedback from adjunctive care providers also suggested high acceptability of the DBT-J program. Quantitative feedback expressed intense optimism, with all adjunctive care providers giving maximum ratings for the treatment’s helpfulness, benefit, and relevance to veteran clients. Qualitative feedback similarly reflected this optimism. For example, feedback from the local Veterans Justice Outreach specialist described the treatment as “invaluable to the VJO program” and reflected gratitude for a “treatment [that] is unique to this population.” Similarly, feedback from an outside substance use counselor noted that the program “has a personal touch” and helped her client “…live better and make better choices.” See Supplement for a comprehensive list of qualitative feedback responses.

Changes in Criminogenic Risk

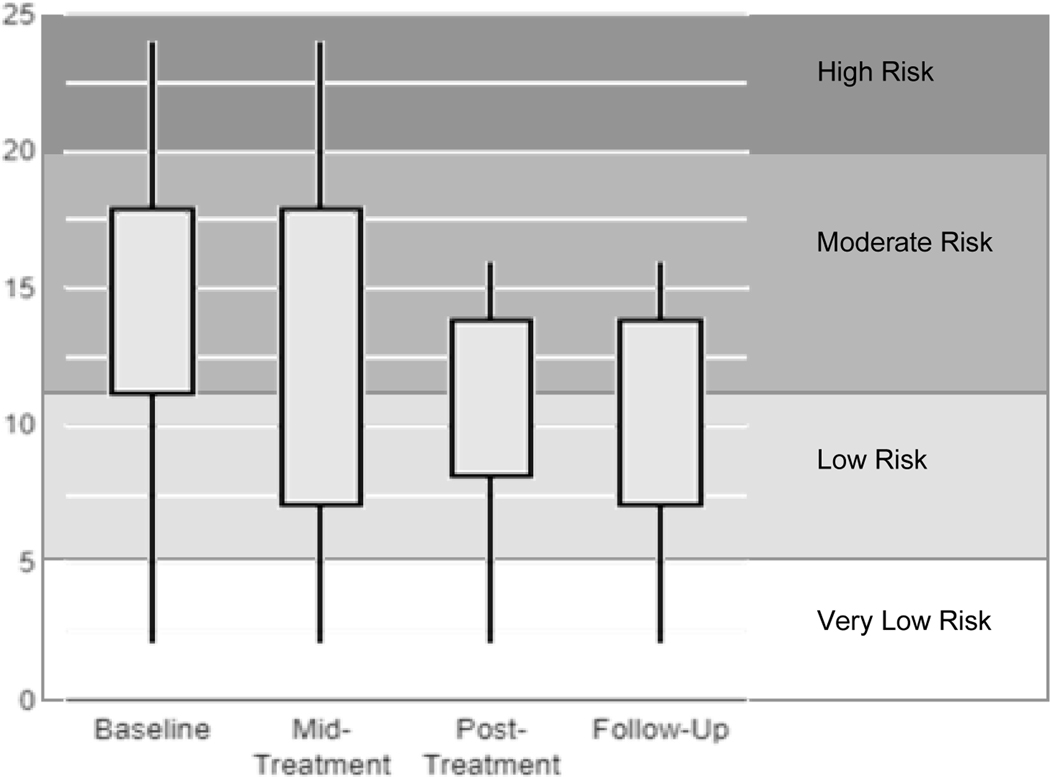

Descriptive statistics (including means, standard deviations, and range) at baseline, mid-treatment, posttreatment, and follow-up were calculated to preliminarily examine Veterans’ changes in criminogenic risk across the course participation in DBT-J. Results suggested a gradual reduction in risk scores from pre- to posttreatment, which were maintained at one-month follow-up. See Figure 3. Correspondingly, 9 out of 10 Veterans experienced a reduction in risk from pre- to posttreatment (the final Veteran received a score of “very low risk” at all timepoints, reflecting no change in risk across the study period), 5 out of 10 Veterans were classified as “low” or “very low risk” by posttreatment, and 0 Veterans were classified as “high” risk by posttreatment. Given the limited sample size, however, results are to be interpreted with great caution.

Figure 3:

Change in Criminogenic Risk Across DBT-J

Discussion

This study represents an initial evaluation of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Justice-Involved Veterans (DBT-J), a novel, psychotherapeutic intervention based in the Risk-Need-Responsivity Model of criminal behavior, Dialectical Behavior Therapy, and the Socioenvironmental Disadvantage Model. Results broadly suggest DBT-J to be both feasible and acceptable as an intervention for VHA-serviced veterans with current and/or recent criminaljustice involvement.

Sample Heterogeneity

The current sample was highly heterogeneous in terms of demographic profile, criminal history, and psychiatric presentation. Most veterans were racial and/or ethnic minorities, unmarried, and in early to middle adulthood. Approximately 30% of veterans’ most recent charges were for violent offenses, 30% for property offenses, and 30% for drug offenses, with 54% of veterans participating in Veterans Treatment Court. Pre-treatment criminogenic risk assessments suggested high heterogeneity in criminogenic risk, with a wide range in degree of prior criminal history; however, substance use was a similarly salient risk factor across most participants. Findings were broadly consistent with the limited research on veteran criminogenic risk, which generally suggests that many VA-connected veterans have a history of multiple arrests (Pandiani et al., 2003; Weaver et al., 2013) and that substance use is often a salient risk factor for veteran criminal behavior (Blonigen et al., 2016). Also consistent with previous research on psychopathology among justice-involved veterans (Finlay et al., 2015), most common psychiatric presentations included posttraumatic stress, alcohol, and mood disorders. Notably, however, veterans with psychotic, personality, and intermittent explosive disorders and histories of suicide behavior (common exclusion criteria for psychotherapies and forensic-focused services; Edwards et al., 2020b; Ronconi et al., 2014; Sander et al., 2020) were also successfully enrolled into the program. Although further research is necessary, these findings suggest DBT-J may be appropriate for a wide range of justice-involved veterans, including those diagnosed with psychiatric disorders generally considered disruptive and/or difficult to treat. These findings are particularly significant given recent research suggesting veteran personality disorder diagnoses to be associated with increased risk of justice involvement (Edwards et al., 2020a) and veterans to meet criteria for personality disorders at rates far exceeding those of the general population (Edwards et al., 2022c).

Acceptability and Feasibility

Previous efforts to implement forensic-oriented psychotherapeutic programming within VHA settings have generally faced extensive barriers to feasibility and acceptability (Blonigen et al., 2018). For example, justice-involved veterans have typically viewed forensic programming as lengthy, intensive, and unable to address their personal needs, and VHA behavioral health providers have viewed such programming as irrelevant to behavioral health (Blonigen et al., 2018). Consistent with this, behavioral health outpatient providers approached throughout recruitment efforts in the current study were generally unaware of clients’ legal status and initially hesitant to refer potentially eligible Veterans to DBT-J due to viewing the program as an unnecessary adjunctive service. Building personal relationships between DBT-J providers and outpatient behavioral health providers, providing education around veteran justice involvement, and partnering with local Veteran Justice Outreach specialists were key to navigating and ultimately overcoming these implementation barriers. Continued development of DBT-J, including expansion to other sites, will therefore likely require similar strategies to establish and maintain referral procedures. Future efforts to implement forensic-oriented programming within VHA settings may also benefit from adopting similar strategies. Relatedly, although inclusion criteria and recruitment efforts aimed to recruit veterans with current or recent involvement with the criminal justice system, most participants had active justice involvement through Veterans Treatment Court (54%) or parole/probation supervision (8%). This pattern may have resulted from outpatient providers’ general lack of knowledge about clients’ legal histories (rendering them unable to identify veterans with prior legal trouble). Future research may therefore investigate how efforts to increase providers’ knowledge of veteran legal needs influences recruitment and sample composition.

To effectively address the complex needs of this population, DBT-J proved somewhat resource intensive for providers, requiring approximately 4.5–5.5 hours a week to support 1–2 concurrent cohorts of veterans. This time commitment did, however, decrease gradually across the course of the trial as providers became more familiar with treatment protocols and procedures became more streamlined. Because some tasks support DBT-J provision across cohorts (e.g., supervision, consultation team meetings), expansion to include additional concurrent cohorts is expected to increase weekly time commitment by approximately 2.5 hours weekly per 6-veteran cohort (1 hour group weekly + 30-minute case management sessions per veteran biweekly).

Patterns of attrition suggest risk for participant dropout may be particularly high during the first few weeks of treatment, particularly for veterans who show inconsistent early engagement. In the current trial, two veterans failed to engage with the program after providing consent despite numerous outreach attempts; another two veterans dropped out and became unresponsive to outreach attempts shortly after beginning the trial. Due to an inability to contact these veterans, reasons for their attrition remain unclear. While unfortunate, these patterns are generally consistent with literature suggesting many instances of dropout occur at the beginning of treatment (Edlund et al., 2002). Judicious use of clinical engagement and commitment strategies even prior to beginning treatment (e.g., during orientation and consent procedures) may therefore be necessary to ensure adequate engagement and avoid this early attrition in future DBT-J trials.

For participants who did engage with the treatment, acceptability assessments reflected optimistic feedback from participants, DBT-J providers, and adjunctive care providers alike. Feedback reflected appreciation for the peer support and validation offered by group therapy sessions and practice benefits of case management sessions. In contrast to previous research suggesting that veterans generally view forensic-oriented programming as irrelevant and lengthy (Blonigen et al., 2018), participants in the current study reported finding the treatment overall helpful and relevant to their needs. One veteran, who was initially hesitant about participating in a group-based program, even expressed desire for the program to be longer in duration. Feedback gathered through these formal acceptability assessments and through participant informal comments throughout the course of treatment informed minor adjustments to treatment delivery and content. For example, in response to comments about group participation, treatment facilitators aimed to implement more structure and reinforcement around group discussions to promote increased, relevant group participation and limit irrelevant group participation. Working examples used to introduce concepts and strategies during skills group sessions were also adjusted to better reflect veteran and military culture and lifestyle; for example, when discussing thinking errors in Session 6, military values around independence were highlighted as potentially contributing to unwillingness to accept help from others. Also, because feedback highlighted the value of case management within the broader treatment program, added efforts will be invested to further develop and refine this aspect of the treatment. For example, future efforts will include establishing partnerships with a broader range of local veteran service organizations to which veterans can be connected and expanding training for providers in procedures and policies around recurrent veteran case management needs (e.g., housing, benefits, etc.).

Telehealth Considerations

Because this initial trial of DBT-J was provided during the COVID-19 pandemic, it relied heavily on telehealth for treatment delivery. This introduced certain logistical complications that may impact feasibility of long-term implementation moving forward. For example, some veterans struggled to access and/or navigate telehealth platforms. Other veterans found it difficult to secure a private space where they could participate in group sessions (e.g., those residing in spaces with limited opportunity for privacy, such as shelters and studio apartments; those with children unable to attend childcare due to risk of COVID-19 exposure). Consistent with other telehealth-based interventions, prompt, creative problem solving was therefore often necessary to successfully navigate the unexpected challenges of adapting to this mode of treatment (Wootton et al., 2020). For example, to resolve technological issues, our team made a program assistant available to provide as-needed technological support. To address confidentiality concerns, we prioritized early, transparent communication around expectations and worked with veterans individually to problem-solve potential barriers, such as lack of childcare. Resolution of these largely logistical challenges often required additional time commitment from DBT-J providers, potentially decreasing ease of implementation.

Nevertheless, what was initially considered a temporary solution to the unexpected pandemic quickly proved vital to the observed early success of DBT-J. The online treatment delivery allowed veterans to remain engaged with DBT-J even while navigating difficult life circumstances, such as homelessness and admission to residential treatment programs. Consistent with previous research suggesting telehealth-based interventions may increase veteran attendance and engagement in mental health services (Fortier et al., 2021), observed attendance and retention rates in this initial DBT-J trial exceeded those often observed in veteran mental health treatment settings (e.g,. Edwards-Stewart et al., 2021; Harpaz-Rotem & Rosenheck, 2011). Our team therefore plans to maintain this telehealth-based approach for DBT-J moving forward, even after the COVID-19 pandemic ends. Future research may compare feasibility and acceptability of DBT-J delivered using a telehealth platform versus in-person.

Next Steps for DBT-J

Criminogenic risk assessments delivered throughout the course of the trial reflected notable improvements from pre- to post-treatment that were maintained at one-month follow-up. Although optimistic, given the limited sample size and lack of comparison condition, these results should be interpreted with great caution. Without continued research, it remains unclear whether results were due to factors specific to the DBT-J treatment or to extraneous variables, such as the passage of time or receipt of outside services (indeed, many participants were engaged in outside mental health and/or case management services in addition to their involvement with DBT-J). In combination with results of acceptability and feasibility assessments, however, these findings highlight the potential utility of DBT-J. Continued research into the efficacy and utility of DBT-J is therefore warranted. Specifically, studies using larger samples and comparison against one or more control conditions are needed to evaluate the potential efficacy of DBT-J. Future studies should also assess a broader range of potential treatment outcomes than was assessed in the current study, such as psychological distress, substance use, and case management concerns. Investigations into mechanisms of change and differential effects across veteran subgroups (e.g., age cohorts, offense types, etc.) would also help in determining how to best tailor DBT-J interventions to the needs of individual Veterans. Lastly, research into implementation considerations, such as cost-benefit analyses and ongoing monitoring of treatment fidelity, would inform the potential scalability of DBT-J to the broader VHA system.

Limitations

Results should be understood within the context of a few methodological limitations. Most notably, the current study represents an initial investigation into DBT-J using a small sample, pre-post design, and no comparison group. Given the small sample size, analyses were also limited to only veterans who completed the program and could not account for veterans who terminated the program prior to completion. Therefore, statistical findings should be interpreted with great caution, generalizability of results remains unclear, and analyses could not account for the potential influence of confounding variables, such as adjunctive care veterans received while also enrolled in DBT-J. Future research that employs larger samples and compares veterans participating in DBT-J against a control condition (e.g., treatment as usual) is therefore necessary to determine the utility of this treatment. Second, the DBT-J treatment developer was intimately involved in delivery and fidelity monitoring of the treatment and co-led all DBT-J groups throughout the trial. It is therefore unclear the extent to which therapist effects may have impacted results. Continued research in which DBT-J is delivered solely by providers not involved with the treatment’s development is therefore needed to inform future expansion and implementation efforts. Similarly, future investigations into DBT-J should employ independent evaluators to complete fidelity ratings. Third, determinations of criminogenic risk were informed primarily by the results of clinical interview. Although ongoing communication with adjunctive care providers (and, where applicable, veterans Justice Outreach specialists) tended to corroborate observed improvements in criminogenic risk, future research may benefit from integrating official record review into assessments of criminogenic risk. Fourth, it is possible that participant compensation influenced data on acceptability and feasibility. Implementation-focused research is therefore necessary to determine potential barriers to acceptability and feasibility of the DBT-J program outside of the research context. Lastly, qualitative feedback was collected and analyzed by the principal investigator, introducing potential for bias in data collection, coding, and/or interpretation. Future research should adopt more rigorous qualitative analyses, including having data reviewed and analyzed by multiple independent coders otherwise uninvested in the research protocol.

Conclusions

The current study represents a preliminary investigation into the feasibility and acceptability of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Justice-Involved Veterans (DBT-J), a novel psychotherapy providing skills-based group therapy and individualized case management services to veterans with current or recent involvement with the criminal justice system. Although preliminary, results are optimistic about the potential utility of DBT-J within a VHA setting. Overall, DBT-J was characterized by high ease of implementation, successful recruitment efforts, strong participant attendance and retention, high treatment fidelity, and high acceptability by veteran participants, DBT-J providers, and adjunctive care providers alike. Veterans who participated in DBT-J also showed notable improvements in criminogenic risk throughout the course of treatment, and these gains were maintained at one-month follow-up. Cumulatively, these findings suggest DBT-J holds potential to fill a need currently unaddressed by the broader VHA system, the treatment of criminogenic risk among justice-involved veterans.

Supplementary Material

Impact Statement.

Justice-involved veterans are a high-risk, high-need subgroup serviced by behavioral health services within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Justice-Involved Veterans was developed as a novel psychotherapy program providing 16 weeks of skills-based group therapy and individualized case management services to justice-involved Veterans. Results suggest DBT-J to be acceptable and feasible for use in a VHA outpatient setting.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to Seth Axelrod, PhD, Suzanne Decker, PhD, Lisa Dixon, MD, Levin Scwharz, LCSW, Peggilee Wupperman, PhD, Melissa Zielinski, PhD, and all of the participating Veterans and adjunctive care providers for their valuable input and feedback regarding the development of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Justice-Involved Veterans.

Funding Information:

Work for this article was funded by a VISN 2 MIRECC Pilot Grant (FY 2021) awarded to the first author.

Disclosure:

Work for this article was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations, VA Special MIRECC Fellowship Program in Advanced Psychiatry and Psychology and by the VISN-2 MIRECC. The views expressed here are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, & Wormith SJ (2000). Level of service/case management inventory: LS/CMI. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, & Wormith JS (2011). The risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model: Does adding the good lives model contribute to effective crime prevention?. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(7), 735–755. [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Bui L, Elbogen EB, Blodgett JC, Maisel NC, Midboe AM, ... & Timko C. (2016). Risk of recidivism among justice-involved veterans: A systematic review of the literature. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 27(8), 812–837. [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Rodriguez AL, Manfredi L, Nevedal A, Rosenthal J, McGuire JF, ... & Timko C. (2018). Cognitive–behavioral treatments for criminogenic thinking: Barriers and facilitators to implementation within the Veterans Health Administration. Psychological Services, 15(1), 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, & Daughters SB (2007). How does dialectical behavior therapy facilitate treatment retention among individuals with comorbid borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders?. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(8), 923–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane-Brink KA, Lofchy JS, & Sakinofsky I (2000). Clinical rating scales in suicide risk assessment. General Hospital Psychiatry, 22(6), 445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Stipelman BA, Sargeant MN, Schuster R, Bornovalova MA, & Lejuez CW (2008). The interactive effects of antisocial personality disorder and court-mandated status on substance abuse treatment dropout. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34(2), 157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, & Koerner K. (Eds.). (2007). Dialectical behavior therapy in clinical practice: Applications across disorders and settings. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Wang PS, Berglund PA, Katz SJ, Lin E, & Kessler RC (2002). Dropping out of mental health treatment: Patterns and predictors among epidemiological survey respondents in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(5), 845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ER, Barnes S, Govindarajulu U, Geraci J, & Tsai J (2020). Mental health and substance use patterns associated with lifetime suicide attempt, incarceration, and homelessness: A latent class analysis of a nationally representative sample of U.S. Veterans. Psychological Services, 18(4), 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ER, Dichiara A, Gromatsky M, Tsai J, Goodman M, & Pietrzak R (2022): Understanding risk in younger Veterans: Risk and protective factors associated with suicide attempt, homelessness, and arrest in a nationally representative Veteran sample. Military Psychology, 34(2), 175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ER, Gromatsky M, Sissoko DRG, Hazlett EA, Sullivan S, Geraci J, & Goodman M (2022). Arrest history and psychopathology among Veterans at risk for suicide. Psychological Services, 19(1), 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ER, Kober H, Rinne GR, Griffin SA, Axelrod S, & Cooney EB (2021). Skills-homework completion and phone coaching as predictors of therapeutic change and outcomes in completers of a DBT intensive outpatient programme. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94(3), 504–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ER, Sissoko DR, Abrams D, Samost D, La Gamma S, & Geraci J (2020). Connecting mental health court participants with services: Process, challenges, and recommendations. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 26(4), 463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ER, Tran H, Wrobleski J, Rabhan Y, Yin J, Chiodi C, Goodman M, & Geraci J (2022). Prevalence of personality disorders across Veteran samples: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality Disorders, 36(3), 339–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards-Stewart A, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, Cyr BA, Beech EH, Skopp NA, & Belsher BE (2021). Posttraumatic stress disorder treatment dropout among military and veteran populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(4), 808–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperson MW, Wolff N, Morgan RD, Fisher WH, Frueh BC, & Huening J (2014). Envisioning the next generation of behavioral health and criminal justice interventions. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37(5), 427–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, Binswanger IA, Smelson D, Sawh L, McGuire J, Rosenthal J, … Frayne S (2015). Sex differences in mental health and substance use disorders and treatment entry among justice-involved Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Medical Care, 53(4), S105–S111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, Smelson D, Sawh L, McGuire J, Rosenthal J, Blue-Howells J, … Harris AHS (2016). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Justice Outreach Program: Connecting justice-involved Veterans with mental health and substance use disorder treatment. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 27(2), 203–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, Stimmel M, Blue-Howells J, Rosenthal J, McGuire J, Binswanger I, … Timko C (2017). Use of Veterans Health Administration mental health and substance use disorder treatment after exiting prison: The Health Care for Reentry Veterans Program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JB, Karg RS, & Spitzer RL (2016). User’s guide for the SCID-5-CV Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® disorders: Clinical version. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fortier CB, Currao A, Kenna A, Kim S, Beck BM, Katz D, ... & Fonda JR. (2021). Online telehealth delivery of group mental health treatment is safe, feasible and increases enrollment and attendance in post-9/11 US Veterans. Behavior Therapy. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galietta M, & Rosenfeld B (2012). Adapting Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for the treatment of psychopathy. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 11(4), 325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Giguere G, & Lussier P (2016). Debunking the psychometric properties of the LS\CMI: An application of item response theory with a risk assessment instrument. Journal of Criminal Justice, 46, 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M, Banthin D, Blair NJ, Mascitelli KA, Wilsnack J, Chen J, ... & New AS. (2016). A randomized trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in high-risk suicidal veterans. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(12), e1591–e1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS (2022). Treating trauma in dialectical behavior therapy: The DBT Prolonged Exposure protocol (DBT PE). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz-Rotem I, & Rosenheck RA (2011). Serving those who served: Retention of newly returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan in mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services, 62(1), 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS & Truax P (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SJ, Rodriguez AL, Smith BN, Matthieu MM, Trent LR, Kemp J, & Thompson C (2017). Barriers, facilitators, and benefits of implementation of dialectical behavior therapy in routine care: Results from a national program evaluation survey in the Veterans Health Administration. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 7(4), 832–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LePage JP, Lewis AA, Crawford AM, Washington EL, Parish-Johnson JA, Cipher DJ, & Bradshaw LD (2018). Vocational rehabilitation for veterans with felony histories and mental illness: 12-month outcomes. Psychological Services, 15(1), 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM, Bronson J, & Alper M (2021). Survey of prison inmates, 2016: Veterans in prison. NCJ 252646. Available at: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/vpspi16st.pdf

- McMain SF, Chapman AL, Kuo JR, Guimond T, Streiner DL, Dixon-Gordon KL, ... & Hoch JS. (2018). The effectiveness of 6 versus 12-months of dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder: The feasibility of a shorter treatment and evaluating responses (FASTER) trial protocol. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KE, Folk JB, Boren EA, Tangney JP, Fischer S, & Schrader SW (2018). Pilot study of a brief dialectical behavior therapy skills group for jail inmates. Psychological Services, 15(1), 98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Haro MV, Harned MS, Korslund KE, DuBose A, Chen T, Ivanoff A, & Linehan MM (2019). Predictors of adoption and reach following dialectical behavior therapy intensive training™. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(1), 100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, & Moules NJ (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent KL, Macdonald JB, Clarke-Walper KM, Penix EA, Curley JM, Rangel TA, ... & Wilk JE. (2021). Effectiveness of the DROP training for military behavioral health providers targeting therapeutic alliance and premature dropout. Psychotherapy Research, Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandiani JA, Rosenheck R, & Banks SM (2003). Elevated risk of arrest for Veteran’s Administration behavioral health service recipients in four Florida counties. Law and Human Behavior, 27(3), 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, & Zimmerman M (1997). Structured interview for DSM–IV personality (SID-P). American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polaschek DL (2012). An appraisal of the risk–need–responsivity (RNR) model of offender rehabilitation and its application in correctional treatment. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 17(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ronconi JM, Shiner B, & Watts BV (2014). Inclusion and exclusion criteria in randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy for PTSD. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 20(1), 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander L, Gerhardinger K, Bailey E, Robinson J, Lin J, Cuijpers P, & Mühlmann C (2020). Suicide risk management in research on internet-based interventions for depression: A synthesis of the current state and recommendations for future research. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Midboe AM, Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Asch SM, Rosenthal J, & Blonigen DM (2014). Treatments for recidivism risk among justice-involved Veterans. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, Vol. 53, pp. 620–640. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson MF (2018). A theoretical and empirical review of dialectical behavior therapy within forensic psychiatric and correctional settings worldwide. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 17(1), 72–95. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Edwards E, Cao X, & Finlay AK (2021). Disentangling associations between military service, race, and incarceration in the US population. Psychological Services. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C, Ryan P, & Flynn D (2018). Exploring dialectical behaviour therapy clinicians’ experiences of team consultation meetings. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 5(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CM, Trafton JA, Kimerling R, Timko C, & Moos R (2013). Prevalence and nature of criminal offending in a national sample of veterans in VA substance use treatment prior to the Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom conflicts. Psychological Services, 10(1), 54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton AR, McCuistian C, Legnitto Packard DA, Gruber VA, & Saberi P (2020). Overcoming technological challenges: Lessons learned from a telehealth counseling study. Telemedicine and e-Health, 26(10), 1278–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.