Commentary

COVID-19 represents the greatest global public health crisis since the influenza pandemic of 1918 1. Since its first report in December, 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has efficiently transmitted from person to person, and two years after the declaration of the pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), it has caused approximately 481,756,671 infections and 6,127,981 deaths worldwide 2.

All age groups are affected by COVID-19 without excluding any condition, including pregnant women and children. Older people are more predisposed to the development of the disease, and patients with comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease often have a worse prognosis 3,4. The disease presents a clinical picture in a range that can vary between an asymptomatic condition to multiorgan failure and death 5. In adults, it usually manifests as fever, cough, and fatigue, and in some cases, it is accompanied by nasal discharge, headache, and other infrequent symptoms, such as diarrhea and gastrointestinal disorders 6.

Coronaviruses are viruses that belong to the Coronavirinae subfamily in the Coronaviridae family and can cause disease in both animals and humans 7. The viral particle, which resembles a crown in electron micrographs, has a size that varies between 80 and 220 nm and carries the most extensive genome of positive-strand RNA viruses; this genome contains five essential genes, of which four encode structural proteins (N, E, M and S) and one encodes a protein for transcription/replication (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, RdRp). The organization in the genome is 5’-RdRp-S-E-M-N-3’, and this order is highly conserved among coronaviruses 7.

The SARS-CoV virus enters its host cell through the binding of the S protein to the ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) receptor; this binding determines the tropism of the virus and viral pathogenesis 8,9. Infection with SARS-CoV mainly generates pneumonia-like symptoms, and the lung is the most pathologically affected organ 10,11. Studies on the histopathology of COVID-19 have reported macroscopic findings such as pleurisy, pericarditis, consolidation, edema and pulmonary hemorrhage, cardiomegaly, and ventricular dilation 12,13.

In the first descriptions of the histopathological findings of SARS- CoV-2, diffuse alveolar damage, hyaline membrane formation and vascular congestion, hemorrhage and fibrinoid deposits in the intra-alveolar space, and inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltration, edema, interstitial fibrosis, and hypertrophy in the myocardium were observed 14. Additionally, pulmonary lesions, such as the desquamation of pneumocytes and the presence of hyaline membranes and edema, have been observed, signs of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Tracheobronchitis with mononuclear cell inflammation, epithelial denudation and submucosal congestion, alveolar infiltrate with alveolar macrophage hyperplasia and mononuclear inflammatory interstitial infiltrate have also been observed 15,16. These alterations are not exclusive to SARS-CoV-2. There are predominant histopathological patterns, such as diffuse alveolar damage, that are shared with other respiratory viruses, such as SARS and influenza; however, vascular alterations, such as thrombosis and microthrombosis, seem to be more frequent in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, which suggests that coronaviruses in general could be associated with an increase in pulmonary microthrombi 17.

Other organs that have presented histological alterations associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection are the liver, kidney and heart. For example, in the liver, cirrhosis, moderate microvesicular steatosis and mild portal and lobular activity have been observed; these alterations can be associated with viral infection or drug-induced damage. In the kidney, chronic kidney disease and acute duct lesions have been described, and in the heart, myocardial fibrosis and mild mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate have been observed 3.

In Colombia, due to biosecurity issues in the framework of the health emergency due to COVID-19, the routine execution of necropsies, viscerotomies and postmortem tissue sampling by invasive methods was restricted; therefore, there is little material from tissues of infected patients as sources of useful information to understand the pathogenesis of the disease and thus few studies on the histopathology of viral infection by SARS-CoV-2. However, among some fatal cases in the Red Nacional de Laboratorios that were initially associated with mortality due to non-COVID acute respiratory infection that underwent routine necropsy, SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by differential laboratory diagnosis, postmortem or some time before death. The tissue samples obtained in these cases are in the archives of the Laboratorio de Patología of the Instituto Nacional de Salud.

As a contribution to the understanding of the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and the morphological alterations caused by infection with SARS-CoV-2, this study illustrates the histopathological alterations and their frequencies among a group of 50 fatal cases of COVID-19 in Colombia (figures 1-11). The histopathological characterization of the cases was performed using histological preparations with routine hematoxylin and eosin staining.

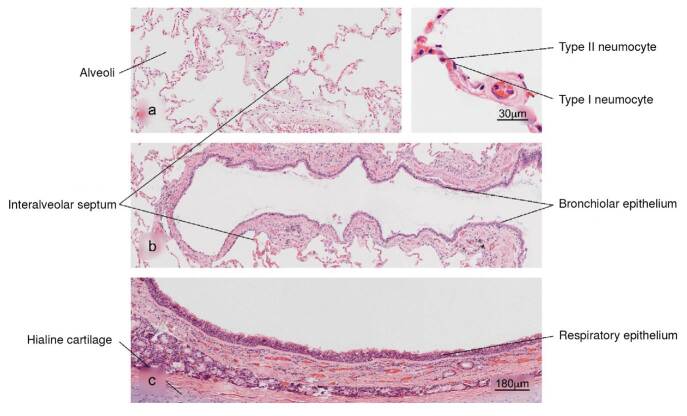

Figure 1. Normal histology of the lung. a) Alveolar region; note the completely free alveoli for oxygen supply through the capillaries located in the interalveolar septa, b) bronchiole in longitudinal section and c) trachea - upper respiratory tract. H&E stain.

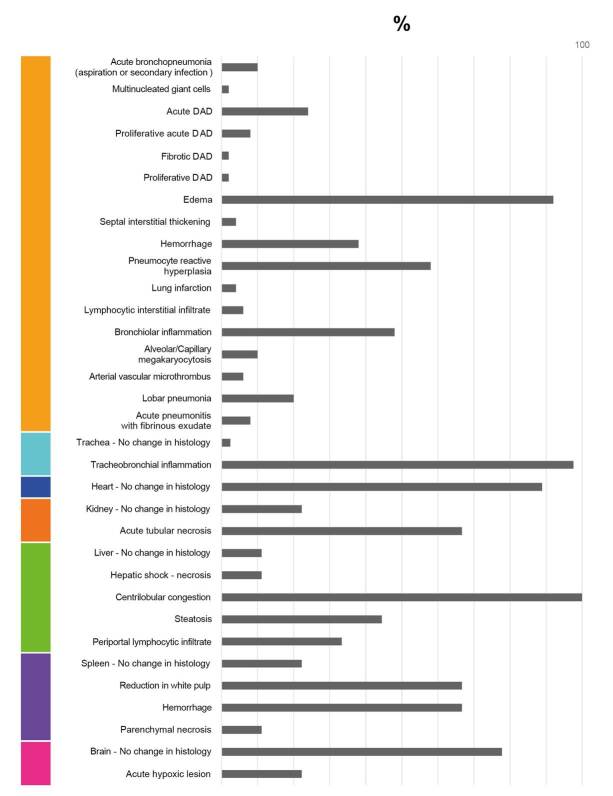

Figure 11. Frequencies of histopathological findings for 50 fatal cases associated with COVID-19.

Lung

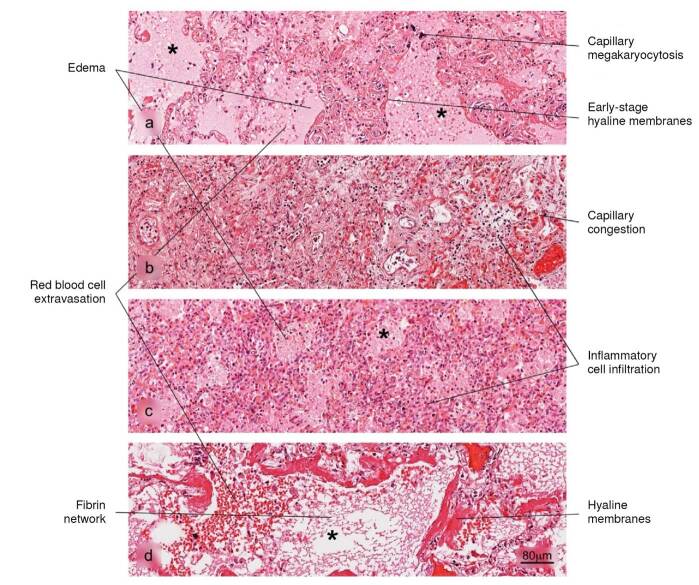

Figure 2. Histopathological alterations in lung tissue associated with COVID-19. The different phases of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) observed in fatal cases are illustrated: a) acute, b) acute proliferative, c) proliferative and d) fibrotic. Pulmonary alveolus (*). H&E stain.

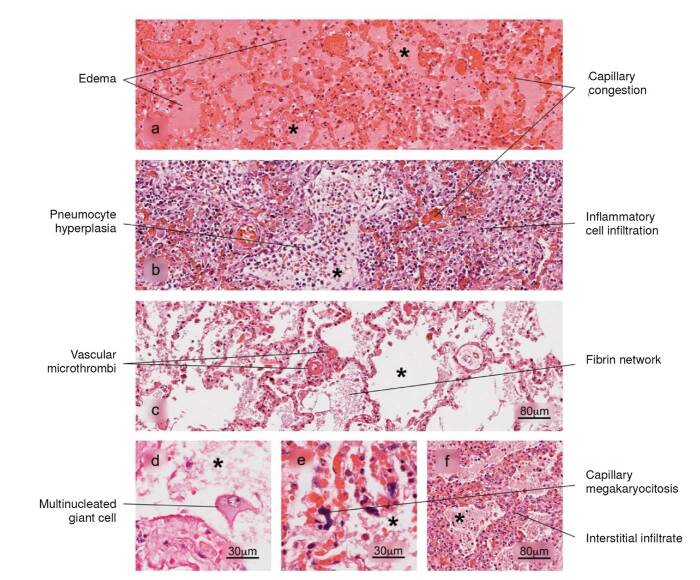

Figure 3. Histopathological alterations in lung tissue associated with COVID-19. a) edema, characterized by the presence of protein content in the alveolar regions, b) reactive pneumocyte hyperplasia, c) vascular microthrombi, d) presence of multinucleated giant cells, e) capillary megakaryocytosis and f) lymphocytic interstitial infiltrate. Pulmonary alveolus (*). H&E stain.

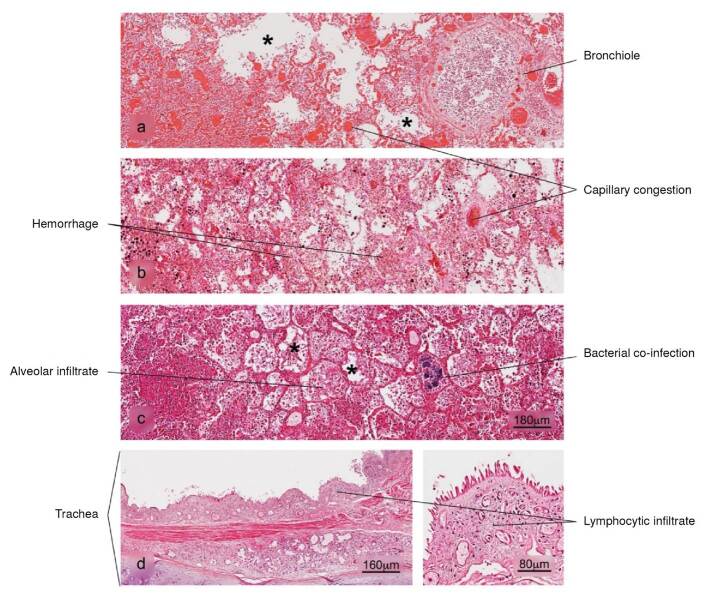

Figure 4. Histopathological alterations in lung tissue associated with COVID-19. a) bronchopneumonia, b) hemorrhage, c) superaggregated lobar pneumonia, d) inflammation of the trachea. Pulmonary alveolus (*). H&E stain.

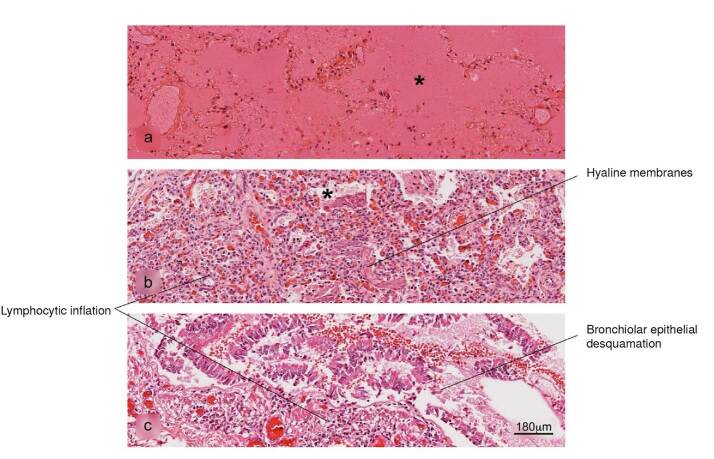

Figure 5. Histopathological alterations in lung tissue associated with COVID-19. a) pulmonary infarction, b) acute pneumonitis with fibrinoid exudate, c) bronchiolar inflammation. Pulmonary alveolus (*). H&E stain.

Spleen

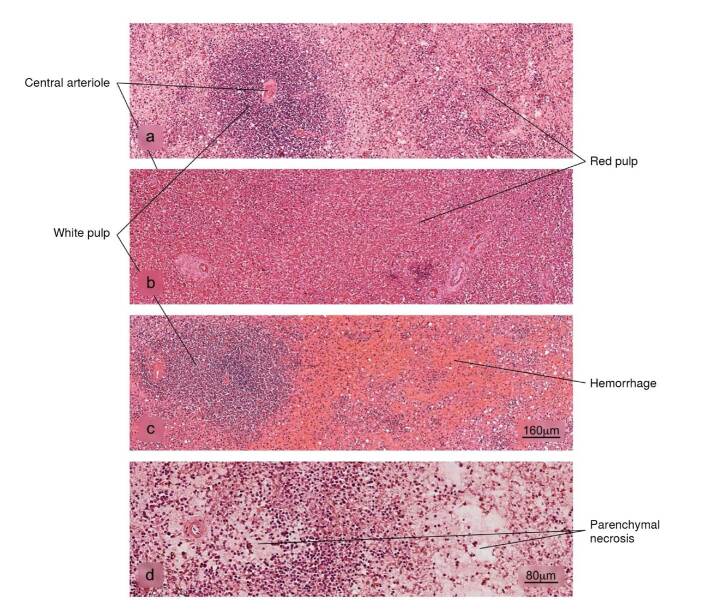

Figure 6. Histopathological alterations in splenic tissue associated with COVID-19. a) Normal histology of the spleen in which a lymphatic node - white pulp - and an extensive area of red pulp is observed, b) reduction in the white pulp, c) hemorrhage in the red pulp, d) parenchymal necrosis. H&E stain.

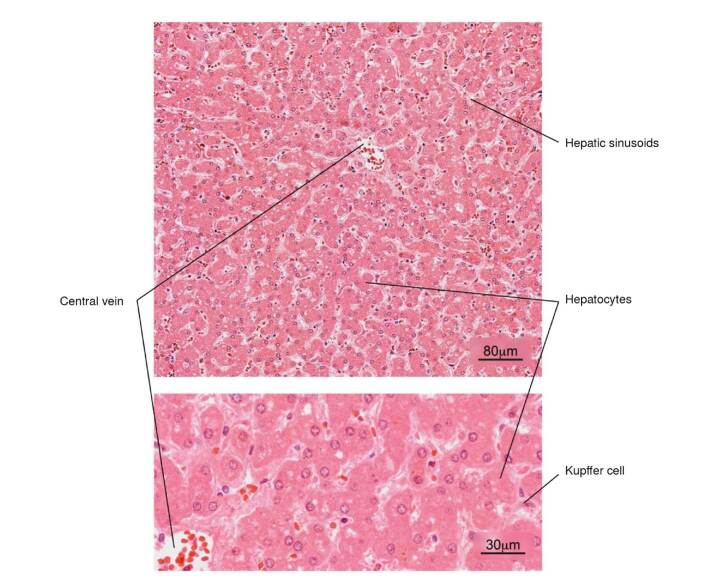

Figure 7. Normal histology of the liver. Note the radial arrangement of the hepatic plates from the central vein of a hepatic lobule. The lower image shows in more detail the hepatocytes and some Kupffer cells located in the sinusoids. H&E stain.

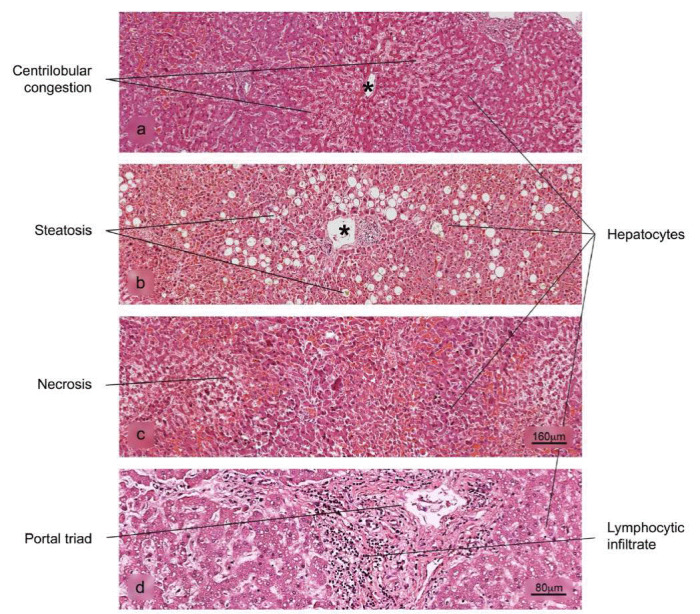

Liver

Figure 8. Histopathological alterations in liver tissue associated with COVID-19. a) sinusoidal congestion, b) fatty liver degeneration - macro- and microvesicular steatosis, c) necrosis, d) lymphocytic infiltrate of the portal triad. H&E stain.

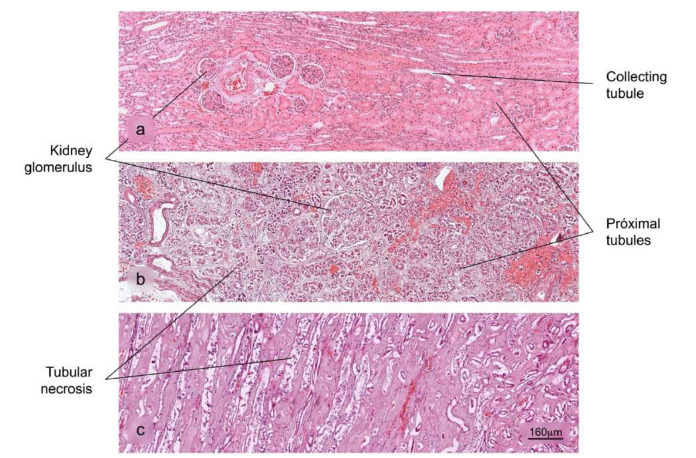

Kidney

Figure 9. Histopathological alterations in kidney tissue associated with COVID-19. a) Normal histology of the kidney. Renal corpuscles are observed in the cortex. b) and c) Acute duct necrosis. H&E stain.

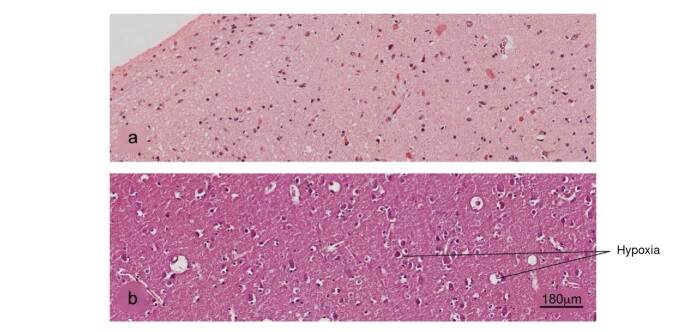

Brain

Figure 10. Histopathological alterations in brain tissue associated with COVID-19. a) Normal histology of the cerebral cortex, b) acute hypoxic lesion and c) encephalitis. H&E stain.

Citation: Rivera J, Corchuelo S, Naizque J, Parra E, Meek EA, Álvarez-Díaz D, et al. Histopathology of COVID-19: An illustration of the findings from fatal cases. Biomédica. 2023;43:8-21. https://doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.6737

Author's contributions:

Jorge Rivera: Design of the proposal; review of histological preparations with hematoxylin and eosin stain; digitization of images, analysis of results, and writing of the manuscript.

Sheryll Corchuelo: Search and selection of cases, confirmation of viral infection by molecular tests, histological characterization, analysis of results, and manuscript review.

Julián Naizaque: Search and selection of fatal cases, review of the manuscript.

Edgar Parra and Eugenio Meek: Review of hematoxylin and eosin stain histological slides and histopathological characterization, revision of the manuscript.

Diego Álvarez-Díaz: Support in the confirmation of COVID-19 viral infection through molecular assays.

Orlando Torres-Fernández and Marcela Mercado: Review and editing.

Funding:

This work was funded by the Colombian Instituto Nacional de Salud through Project CEMIN 23-2020.

References

- 1.Esposito S, Noviello S, Pagliano P. Update on treatment of COVID-19: Ongoing studies between promising and disappointing results. Infez Med. 2020;28:198–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Weekly Epidemiological Update and Weekly Operational Update 2020. [March 30, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports .

- 3.Caramaschi S, Kapp ME, Miller SE, Eisenberg R, Johnson J, Epperly G, et al. Histopathological findings and clinicopathologic correlation in COVID-19: A systematic review. Mod Pathol. 2021;34:1614–1633. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00814-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang X, Wei F, Hu L, Wen L, Chen K. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of COVID-19. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23:268–271. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulut C, Kato Y. Epidemiology of COVID-19. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50:563–570. doi: 10.3906/sag-2004-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu XW, Wu XX, Jiang XG, Xu KJ, Ying LJ, Ma CL, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: Retrospective case series. m606BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SE. Epidemiology, virology, and clinical features of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2; Coronavirus Disease-19) Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020;63:119–124. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.00493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belouzard S, Millet JK, Licitra BN, Whittaker GR. Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses. 2012;4:1011–1033. doi: 10.3390/v4061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:586–590. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding Y, He L, Zhang Q, Huang Z, Che X, Hou J, et al. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: Implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J Pathol. 2004;203:622–630. doi: 10.1002/path.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farcas GA, Poutanen SM, Mazzulli T, Willey BM, Butany J, Asa SL, et al. Fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome is associated with multiorgan involvement by coronavirus. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:193–197. doi: 10.1086/426870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanley B, Lucas SB, Youd E, Swift B, Osborn M. Autopsy in suspected COVID-19 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:239–242. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox S, Akmatbekov A, Harbert J, Li G, Brown J, Vander Heide R. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: An autopsy series from New Orleans. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:681–686. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martines R, Ritter J, Matkovic E, Gary J, Bollweg B, Bullock H, et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 associated with fatal coronavirus disease, United States. 2005Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26 doi: 10.3201/eid2609.202095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hariri LP, North CM, Shih AR, Israel RA, Maley JH, Villalba JA, et al. Lung histopathology in coronavirus disease 2019 as compared with severe acute respiratory syndrome and H1N1 influenza: A systematic review. Chest. 2021;159:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.09.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]